ABSTRACT

The author retrospectively reviews the aesthetic and political preoccupations of his 1986 book Between on the occasion of its 2020 republication.

KEYWORDS:

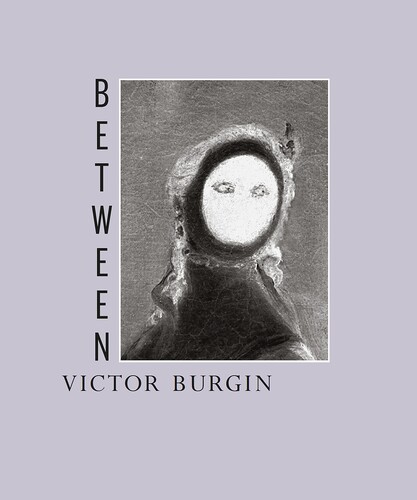

The book Between was originally produced to accompany an exhibition of my work at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London. At that time, as now, exhibition catalogues usually provided reproductions of an artist’s work together with a critical essay and an introduction by the director. I was fortunate in that the director of the ICA in 1986, Declan McGonagall, was happy to agree to my departing from this norm. I wanted Between to represent a process of making and thinking about art as it had evolved across a decade. To this end the book intersperses illustrations of my artworks from the period 1976–1986 with fragments of commentary, excerpts from interviews, talks, letters, and so on. I was doubly fortunate to collaborate with a graphic designer, Robert Carter, who understood my idea and was able to give a coherent flow to these disparate elements across the pages.

I think of Between as one of my ‘interstitial’ books in that it stands ‘between’ two types of publication. On the one hand, Between is not a collection of theoretical essays, like my book The Camera, which was published by MACK in 2018. On the other hand, nor is Between an independent artwork, like my text/image book Afterlife, which was published by Thomas Zander/Walther Köenig in 2019.

In addition to standing between two forms of practice Between now stands between two times: I’m today looking back from 2020 to a book published in the mid-1980s, which in turn looks back to the mid-1970s – three very different historical contexts. The core of my preoccupations remains constant throughout this period, but around this core my practices evolve in response to changing times.

In terms of camera use Between moves from the zero degree of non-use, with appropriated images, through straight documentary, and the aesthetics of street photography, to studio photography.

The first of my artworks reproduced in Between is from 1976. What I thought about photography in the mid-1970s was that there was already an overabundance of photographs in the world, and it would be redundant to add even more images to this surfeit. Consequently, as I say early in Between: ‘My work from 1973 to 1976 had all been what today is called “appropriated image” work. I was recycling advertising imagery and reproducing the rhetoric of advertising copy.’ I became increasingly frustrated however with having to toil through mountains of printed matter in search of the appropriate image to appropriate. Without the possibility we have today of recourse to the Internet, I turned to the camera. Having crossed the line from ‘using’ photographs to making photographs my relation to the camera inevitably changed. As my interest in photography increased I moved from teaching in an art school to teaching in a photography school.

In Dante Alighieri’s long narrative poem The Divine Comedy (1320) the Roman poet Virgil leads Dante to the gates of Hell. Inscribed over the entrance are the words: ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.’ If this had been the gate to the art school I first entered in the late 1950s then the inscription would have read: ‘Abandon all language, ye who enter here.’ At that time it was believed that artists expressed themselves by means that were ‘purely visual’. The doctrine of the ‘purely visual’ subsequently lost its grip on the art school, but I encountered it again when I first went to teach in a photography school.

In its most extreme form the idea of the ‘purely visual’ implies that one may invent one’s own private language. But the expression ‘private language’ is an oxymoron – by definition, a language is something that is shared.

The situation in this office is somewhat different from that in the classroom. Unlike the little girl’s classmates, the man behind the desk has not made a personal interpretation of his subordinate’s gesture. He recognises that the gesture is meaningful, but accepts that he himself has no access to the code that will allow him to understand it. The cartoonist is able to assume we are all familiar with the expression ‘the language of dance’. We are no less familiar with the expression ‘the language of photography’.

Such expressions had long been in common use, but it was only in the 1960s that they were examined from the standpoint of linguistic science. By the second half of the twentieth-century the understanding of the mechanisms of language had advanced considerably. Some thinkers began to ask whether these same mechanisms might be found at work in signifying systems other than speech and writing.

In Elements of Semiology – first published in French in 1964 and in English in 1967 – Roland Barthes tests the extent to which the basic analytical concepts of structural linguistics may be applied to such meaningful systems as food and clothing.

I first encountered this book somewhere around 1971. I was in my first teaching job, at Nottingham School of Art, and became friendly with someone with a background in anthropology.

I believe we’d bonded over Georges Charbonnier’s Conversations with Claude Lévi-Strauss, which I had read in English translation in this small Jonathan Cape edition. I would guess it was this that led my colleague to recommend that I read Elements of Semiology, which had also been translated for Cape. It was a ‘Saul on the road to Damascus’ moment for me. After that first reading – and it’s a book I continued to reread – I went looking for other books by Barthes.

I found only Writing Degree Zero, in the same Cape series. There were no other English translations of Barthes available at that time. So I went to Paris and came back with a bag full of assorted texts, not only by Barthes but also by the writers he draws on in Elements. I bought myself a large French–English dictionary and sat down to work my way through them.

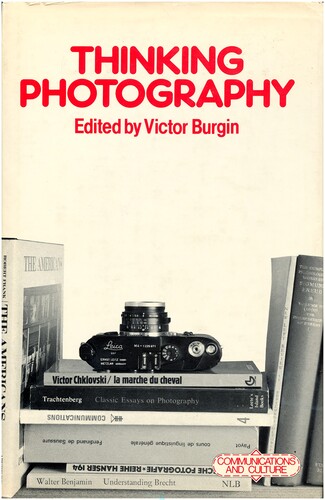

I summarised what I’d learned and applied it to photography in my long essay ‘Photographic practice and art theory’, which was first published in the journal Studio International in 1975, and then republished in my edited collection Thinking Photography in 1982.

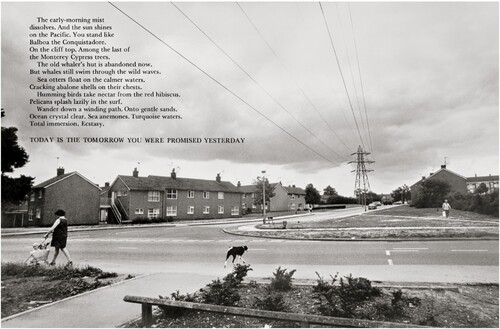

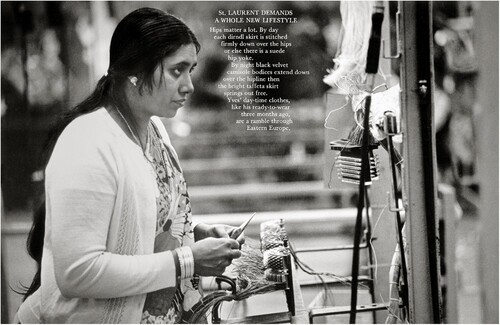

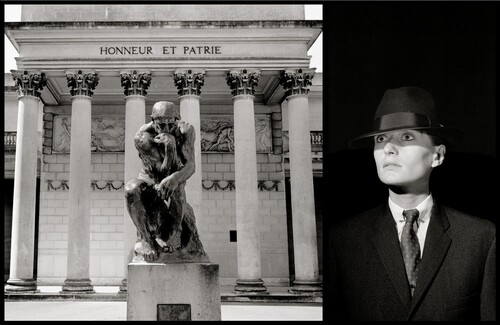

This is one of eleven panels that make up my work UK76. I set out to combine three commonly encountered uses of photography: in a book or news journal, in the street, and in a fashion magazine. I made a ‘documentary’ style photograph, enlarged it to the size of a poster, then placed type over it in a way familiar from such publications as Vogue. In the manner of posters, the works were pasted to the walls and scraped off at the end of the exhibition.

The text and the image here juxtapose two everyday realities usually encountered separately: an industrial worker, and the fashion column of a daily newspaper. In rhetorical terms, the relation of text to image is one of ‘contradiction’. Together with irony and paradox these are the main forms that structure text-image relations throughout the eleven panels.

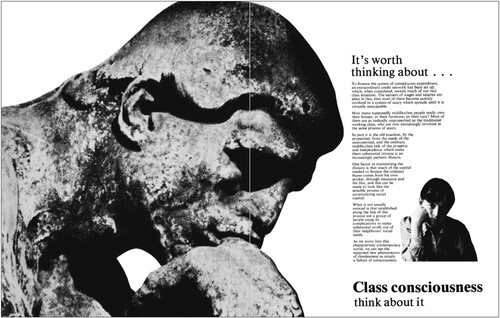

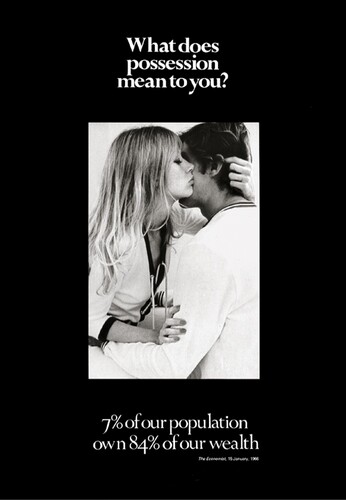

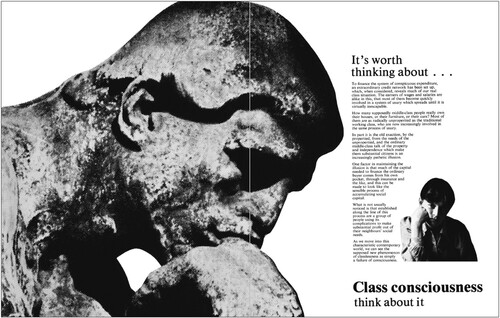

I was also making posters for the street at that time. This one is reproduced in Between accompanied by a transcript of vox-pop responses to the work broadcast on Radio Newcastle. In this work economic class and sexual politics are beginning to be thought together.

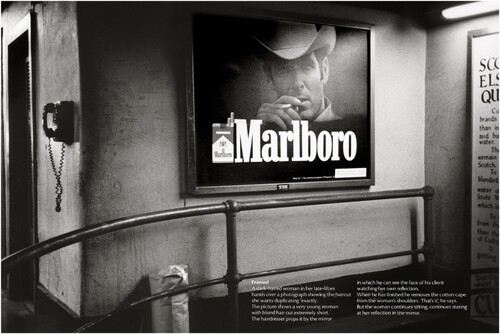

This is one of twelve panels from a work I made the following year, US77. The images are the same size as those of UK76 and again combine documentary photograph, poster and reversed out text. The text-image relations however are totally different, as is the form and content of the text. The text is in the form of a short narrative account of a visit a woman makes to the hairdresser. The text is related to the image through a repetition of written and photographed frames: the frame of the panel on the gallery wall, the frame around the advertisement in the photograph, the frame of the photograph of the model in the narrative, the frame of the mirror in which the woman looks at her own image. In the space of a year, between two works that at first sight might appear closely similar, the focus of the work has shifted from the question of class difference to that of sexual difference, and the structure of the work had moved away from a rhetoric of ‘consciousness raising’ to the logic of unconscious processes. The paramount question remains that of ideology.

The British Marxist cultural theorist Stuart Hall said that the many years he spent studying the phenomenon of Thatcherism had definitively pushed him away from the last vestige of any rationalist conception of ideology. If we are to understand the logic of Thatcherism, he said, then it is better to ask ‘what is the logic of a dream’ rather than ‘what is the logic of a philosophical investigation’.

In the image on the cover of Thinking Photography a camera is accompanied by publications representing currents of thought running through the essays gathered in the book: Barthes’ ‘Elements of Semiology’ is present in the form of its original publication in the French journal Communications, and to the right is Volume IV of the English language Standard Edition of the works of Sigmund Freud, one of the two volumes devoted to his foundational work of 1900 The Interpretation of Dreams.

The cultural world at the turn of the 1970s was far more cloistered and partitioned than it is today. At the time of Thinking Photography I was still unaware of Juliet Mitchell’s book Psychoanalysis and Feminism, which had been published in 1974. This book, however, greatly influenced the thinking that informs Between. Rather than beginning with the category ‘woman’ – as so many of her contemporaries were doing – Mitchell rather follows Freud in his attempt to understand how men and women alike come into being from their common origin in an inherent infantile psychical bisexuality.

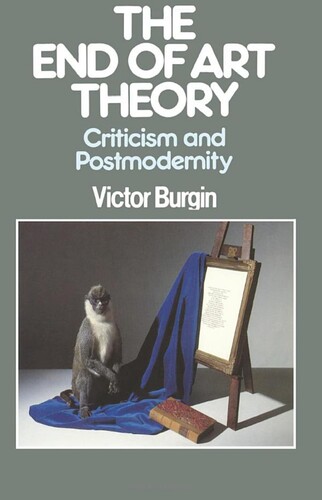

Between was published in the same month as my book The End of Art Theory, a compilation of essays written across the same decade covered by Between. The first essay is a critique of Greenbergian modernism, the last essay in the book is a critique of postmodernism.

My theoretical writings and my works for exhibition have always proceeded alongside each other, but with varying distances between them. These two strands of activities became most intimately entwined in 1984, when I produced The Bridge for the John Weber Gallery in New York and gave my talk ‘Diderot, Barthes, Vertigo’ for the symposium ‘Film and Photography’ at the University of California, Santa Barbara – which was subsequently published in The End of Art Theory.

The convergence of my artwork and my writing in 1984 represents the conjunction of two intellectual and artistic preoccupations most prominent in that period of visual cultural history: the relation of the still to the moving image, and the representation of sexual difference.

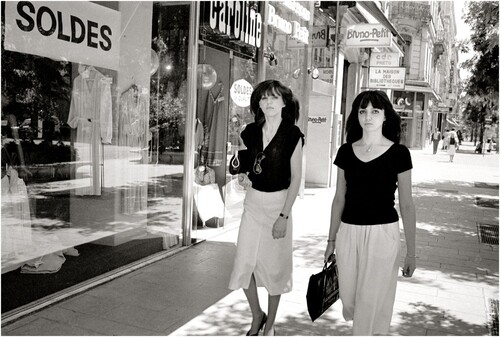

In the most schematic and reductive of terms, Between begins with thinking about the subject of class division …

… and ends in thinking about the subject of sexual division.

The debates around sexual difference that took place in the 1980s have today moved to a more emphatic focus on the critique of ‘binarism’ and the contestation of ‘heteronormativity’ under patriarchy – with the difference that today psychoanalysis seems largely to have dropped out of the picture. In my own long reading experience however I have encountered nothing more ‘queer’ than psychoanalytic theory.

In the final work represented in Between – as an incomplete work in progress – I bring the perspectives of class and sexuality into convergence through a reflection on Edward Hoppers’ 1940 painting Office at Night.

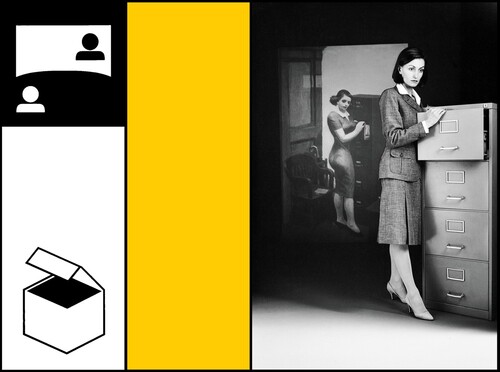

This is the completed panel as it appeared in the 1986 exhibition at the London ICA that was accompanied by Between.

The work begins with my fancy that Hopper’s secretary has freed herself from the position in which she was painted and now investigates and occupies the space of the office.

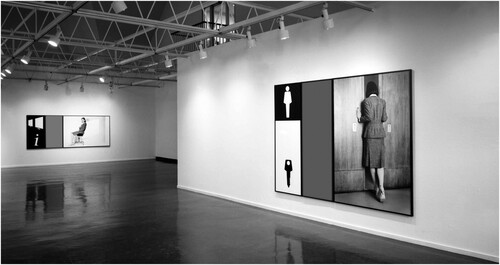

The entire work comprises seven panels. Here is a corner of their installation at the Renaissance Society, in Chicago, the same year.

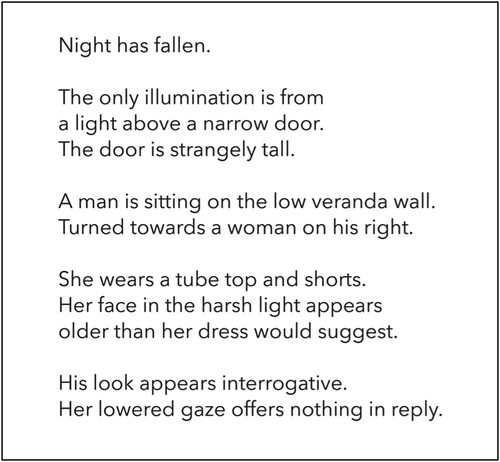

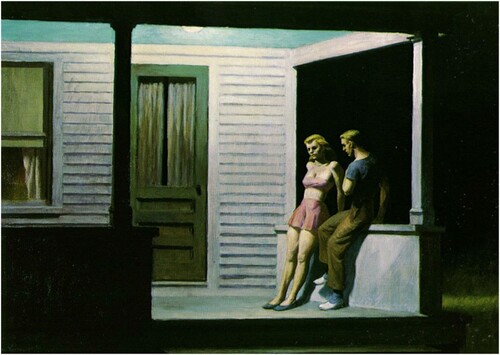

Thirty-three years later – years during which I worked mainly in video – I again reference a painting by Edward Hopper, but very differently. This passage is from the 2019 text-image work Afterlife I mentioned at the beginning. The text is an exercise in ekphrasis – the written description of a visual work of art.

This is the image that is described. But Edward Hopper’s 1947 painting Summer Evening is not reproduced in the pages of Afterlife.

I rather invoke my memory of the painting in the form of a fantasy of the stage upon which Hopper’s figures are about to appear … or from which they have departed.

My bookwork Afterlife – which also exists in web-based form – consists of passages of images and texts orbiting the core premise of a parallel world in which technology provides perfect digital copies of individual minds, As I write in the book: ‘Once the duplicate is made, there are effectively two beings: one organic, the other numeric. Each evolves separately but only one will die’. The science fiction scenario serves as an allegory of everyday life understood as a continual work of transaction between material reality and the virtual realities of memory, fantasy and computer simulations. The narrative anchor-point of the work is in the classical myth of Orpheus and Eurydice which in 1984 was at the centre of my work The Bridge.

The Hopper ekphrasis is one two texts in Afterlife that describe paintings, others draw upon personal memories, scenes from novels, films, or purely imaginary scenes. Such various fragmentary passages of writing are interspersed with images which also draw upon my memories and imaginings.

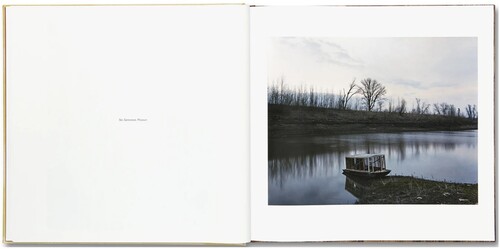

For example, while I was browsing through books on the MACK website I was particularly struck by this image from Alex Soth’s photo book Sleeping by the Mississippi. The image remained with me and it was only while I was working on Afterlife that it occurred to me that this was probably because I had associated it with the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The dark waters here had become those of the river Styx that separates the land of the living from the realm of the dead.

I paraphrased Soth’s image – or, rather my memory of the image – for Afterlife.

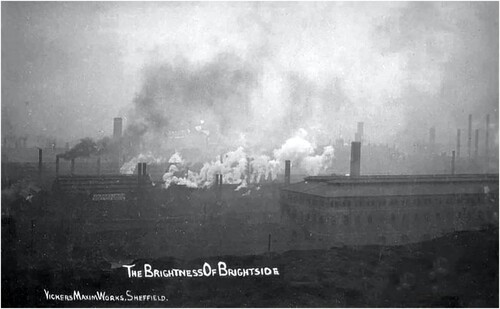

This ironically captioned postcard from the 1950s shows the place where I grew up, in Sheffield in the North of England, which was then a centre of the steel industry.

In this case I came across the postcard only after I had made this image for Afterlife – again, not so much an image from memory as an image that stands in the place of my memory. In psychoanalytic terms, perhaps even a ‘screen image’.

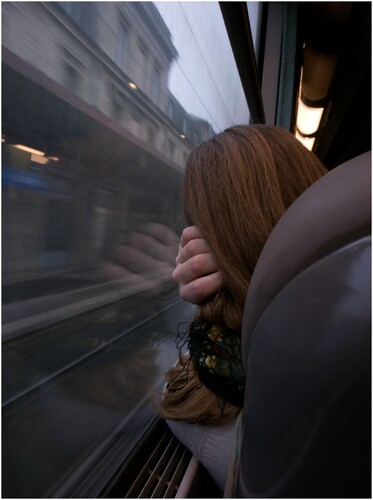

This image is both literally and figuratively at the centre of Afterlife. The woman in the photograph here stands in for the pivotal object – the Eurydice figure – around which my ‘narrative’ turns. Physical corporeality is literally at the centre of the image, in these knuckles flushed with the blood that courses beneath the skin.

The train might be seen as figuring ‘passage’ in the Orphic myth: first into the underworld, then out. But where, in the myth, Eurydice follows Orpheus, here she is ahead. In the myth Eurydice is dead, but here the photograph of the woman is the only live thing in a dead world of digital images.

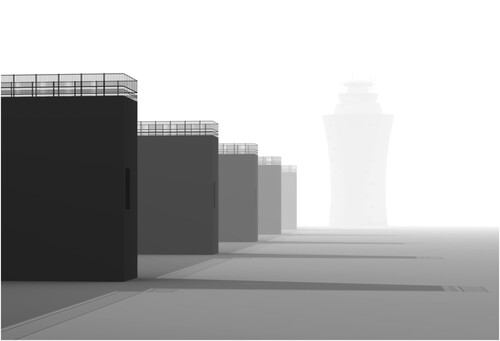

At the time of Between photography had become a heavily material affair for me. Today I build my sets in virtual reality, light them with virtual lights and photograph them with virtual cameras. With the single exception of the woman on the train, all the images in Afterlife are made using a ‘game engine’ – software originally designed for the production of video games, but which may be turned to other uses.

Working digitally has allowed me to think of Afterlife as a potentially limitless and proteiform work. In a currently fashionable expression it is ‘transmedial’ – with manifestations on the web, in book form, moving images and gallery installations.

A bus map of a city does not replace a metro map, it lies over it to show different paths through the same territory. This is true of the schematic ‘three times’ of Between. In the first of these, semiotics provides my principal framework for understanding the everyday image environment, and for ‘thinking photography’ in particular. In the second, psychoanalysis offers an additional layer of interpretation to fill some of the lacunae of linguistics through fine-grained descriptions of the poetics of association and affect. In a third time, phenomenology merges with semiotics and psychoanalysis to form the composite lens through which I view the world.

The painter Pierre Bonnard said that he wanted the viewer’s experience of his paintings to be like the experience of first entering an unfamiliar room: one sees everything at once, yet nothing in particular. What I would add to Bonnard’s purely optical picture are the impromptu thoughts one may have at that moment, from purely personal associations to what I call the ‘granular-perceptual’ manifestation of the political – an aspect of our everyday reality on an equal perceptual basis to the changing light, an aching knee, a distant sound or a regret. This is the phenomenological real of my experience.

This ‘real’ has nothing to do with the ‘reality’ of documentary ‘realism’. Roland Barthes observes that the real is not representable, but that writers have nevertheless ceaselessly tried to put it into words. The succession of their failures has given us the history of literature. I might say much the same of the ‘visual’ artworks that interest me most. They may vary in historical period and in appearance, but I sense in them a common relation to the phenomenological real, a common way of being in the world.

What most fundamentally changes across the three times of Between is my understanding of the relation of art to politics. As a consequence of my encounter with feminism the centre of my attention first shifts from the representation of politics to the politics of representation, which for me in 1986 meant the representation of sexual difference. Subsequently however I came to judge that the political import of a work of art is to be measured not by its manifest content, but by the degree and nature of its relation to the pre-formatted versions of reality that mark the boundaries of what may be thought and said – a pre-formatting found as much in works of art as in popular sit-coms and soap operas.

Narrative remains a constant focus of attention across the three times of Between. Early in my interest in photography I began an essay with the observation: ‘It is almost as unusual to pass a day without seeing a photograph as it is to miss seeing writing.’ We may say much the same of narrative. Indeed photography (still or moving) and writing (spoken or graphic) are the primary vehicles of narrative. Narrative is encountered everywhere, and such forms of narration as novels and films are only the more apparent features of a total and totalising environment of tales. Nor is storytelling simply entertainment. What we call ‘ideology’ is the sum of the stories by which we live, and the course of human history is determined through more or less violent struggles to ‘own the narrative’.

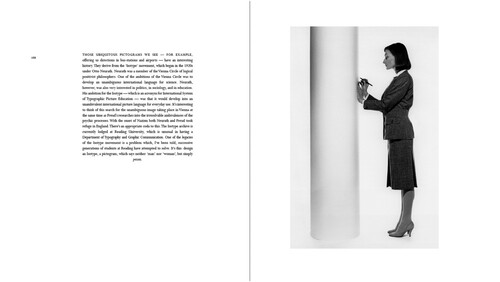

Between concludes with the dream of a purely visual language. The short text that accompanies the last photograph – from the then incomplete Office at Night – tells the story of the ‘Isotype’ movement, which began in the 1920s under the positivist philosopher Otto Neurath. The movement led to those ubiquitous pictograms that guide our way through public space.

Neurath’s ambition for the Isotype – an acronym for International System of Typographic Picture Education – was that it would develop into an unambivalent international picture language for everyday use. This it did, but it left a fundamental challenge which successive generations of design students have attempted to solve: design a pictogram, which says neither ‘man’ nor ‘woman’, but simply person.

This iconogramme stands alone on the last page of Between. It calls across ten years to the first image in Between.

And there, with a shrug, Between ends.

Permission statement

Edward Hopper: Summer Evening, 1947 © Heirs of Josephine Hopper/ Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY/DACS, London 2022.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Victor Burgin

Victor Burgin is an artist and writer. He first came to prominence in the late 1960s through his contributions to the first museum shows of Conceptual Art. His still and moving image work is represented in public collections that include the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Victoria and Albert Museum and Tate Modern, London; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, and the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. The next major exhibition of his work will take place at the Jeu de Paume, Paris, in 2023. His books include Thinking Photography (1982), The End of Art Theory (1986), In/Different Spaces (1996), The Remembered Film (2004) and The Camera: Essence and Apparatus (2018). Burgin is Professor Emeritus of History of Consciousness, University of California, Santa Cruz; Emeritus Millard Chair of Fine Art, Goldsmiths College, University of London; and Professor of Visual Culture, Department of Art & Media Technology, Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton.