ABSTRACT

This article presents a sequence of drawings belonging to the wider project Letters to Anni (2022-). At the centre of the project is an event of writing: the habitual gesture of handwriting – in this instance, in the context of a longhand letter to Anni Albers – recorded using motion sensors. A sequence of translation processes applied to the captured digital data allows the usually ephemeral movement of points on the hand to be registered as linear compositions. The interspersed text ruminates on inscribed line as expression of thought, and mediator between language and movement. It draws together a constellation of reference points, including the personal experience of learning to write, Vilém Flusser’s ‘Gesture of Writing’, and Albers’s interest in visual forms of writing that influenced her figurative weavings, and which inspired the project. A context for the work unfolds; the drawings, characterised by a writing aesthetic that is read as image rather than text, are positioned as a kind of ‘para-writing’, made in the moment of inscribing meaning, they are drawings located beside the lines of writing.

Of the many systems of graphical notation, writing is the most widely taught and understood. Written English relies on an alphabetic system, and its use of signs representing consonants and vowels directly relates the graphical representation of thought to sound: the writer’s silent thoughts, translated into words on the page, can be read or performed aloud by anyone who understands the orthographic system. There are systems of ancient writing that remain undeciphered; if our own is surpassed by other forms of communication, it is possible that the key to its understanding may in turn be lost.

I recall the thrill of receiving my first fountain pen. It was in Form 5’s Portakabin classroom; I was nine years old. Pre-selected red, green, black, or blue Osmiroid pens with right or left-handed italic nibs were distributed amongst us once we had achieved the requisite level of fluency in handwriting. I had chosen the dark blue barrel; my best friend had chosen green. This rite of passage signified accomplishment in the mechanics of writing; the automaticity that would free us to focus on content. Yet instead of the words I wrote, the dynamics of the ribbon-like ink lines filling the page, and the gesture of writing itself are what remain inscribed on my memory.

Ruth A Fagg’s ‘Everyday Handwriting’ books provided the model for our learning and an embodied understanding of the alphabet developed as we delineated letters at scale in the air. Before acquiring our ink pens, we repeated these gestures on the page in pencil lines of rhythmic patterns: row upon row of individual or paired letterforms, sometimes rotating the paper so that upside-down letters abutted the right-way-up ones. From these exercises new shapes formed – a non-verbal writing that couldn’t be read. According to Rosemary Sassoon, Fagg ‘always looked at writing in the same category as dancing, as movement’ (Citation2007, 129). The identification of the everyday gesture of writing with the ephemeral, unregistered movement of dance points to the conditions underpinning the drawings on the following pages.

The rule-based system of writing mediates between the conceptual and the physical, the immaterial and the material. The reader engages with a text intended to communicate ideas, however, words on a page belie the gestures that attest to writing’s temporal and spatial dimensions: the back and forth between phases of thinking and the motion of inscription as language takes possession of thought.

Vilém Flusser states that due to its habitual nature ‘[w]e do not think about the act of writing while writing’ (Citation1991, 1). The Gesture of Writing (Flusser Citation1991) forensically describes the process, and from ‘external observations’ he cites the components – conventions, knowledge and tools – required to write. However, allied to the physical fact of writing and the application of skilled movement in relation to tools of inscription or a keyboard, Flusser uses ‘inner observation’ to reveal further insights, identifying thinking and hesitation, and the ‘listening, motionless, concentrated phase’ as ‘just as characteristic of writing as is the phase of motions’ (Citation1991, 5). Much earlier, Stéphane Mallarmé’s prose similarly suggests a bilateral aspect to writing, acknowledging the unregistered phases, immaterial yet indicative of context, that are necessary to the process. Unless applied to paper, the trace of thought is ‘evanescent’, and the ‘violent fisticuffs with the idea’ (Mallarmé Citation2007, 215) – a more colourful evocation of Flusser’s phases of thinking and concentration – are gestures at risk of being lost.

Writing is recognised as the trace of thought in its transformation from the conceptual to the physical, but in this equation the reader only ever experiences a partial representation of writing’s gesture in their encounter with an edited text on the page. Words communicate linguistic meaning, where the experiential and sensory aspects of its making are not revealed; there is no trace of writing’s context.

Flusser recognises a distant historical relationship between the gesture of writing and sculpture through its beginnings as scratched lines in soft clay (Citation1991, 1); elsewhere he refers to it as a ‘craft’ (online: Citationno date). However, linguistic meaning remains the goal in the crafted writing he refers to.

The etymology shared by the words text and textile allows the language of craft, specifically textile crafts, to reach beyond its disciplinary context, providing rich metaphoric associations for the writer where ‘word becomes surrogate for the substance’ (Mitchell Citation1997, 8). Whilst recognising that textiles and words are different things, Victoria Mitchell notes that ‘the differences between them benefit the conceptual apparatus of thought at the expense of its sensory equivalent’ (Citation1997, 8). For Mitchell Anni Albers, in writings from early in her career, working primarily as a weaver, justifies making through materials ‘as almost a superior kind of thought’ (Citation1997, 8), thus resisting the privileging of language in favour of a form of articulation and understanding that is alternate to words.

Albers clearly had a fascination for language in its graphic form. Miscellaneous newspaper cuttings from her collection held at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation reveal a sustained interest in language that she would not have been able to decipher. Examples of Sumerian and Persian Cuneiform, Mayan, Aztec, Hebrew, Japanese, Arabic and Chinese calligraphy, along with images of petroglyphs and ancient ground drawings are cut out and kept. Apart from the largescale earthworks these all adhere to a linear structure that is equally common to our contemporary writing system and to weaving.

The titles of a number of Albers’s figurative weavings make associations between language and textiles.Footnote1 Where writers use textile metaphors when a material context is absent, she reverses this position, inviting the viewer to make a connection between her weavings and text, where linguistic expression is absent from the work itself.

In her ninth decade, Albers made a group of modest felt pen drawings that could be categorised as asemic writing.Footnote2 These drawings conform to the horizontal linear structure of Western writing, placed on the page like poems or letters, indeed one is made on the reverse of a letterheaded sheet of paper. However, with no basis in our alphabet and with the rules of language overturned, the viewer/reader is forced to search for meaning elsewhere. As with her figurative weavings the drawings are material metaphors for text, that speak to the gestures of making.

Made in response to the experience of seeing Albers’s drawings and collected newspaper cuttings at first hand, Letters to Anni (2022) is an ongoing body of work exploring the gaps and overlaps between the visual and the verbal. At the outset, the continuous movement of writing a longhand letter to Albers is recorded using motion capture sensors on each finger.

The trace of writing on a page is one of discontinuity: the reader sees a sequence of deliberately formed words, however, incorporated into this gesture are physical and temporal spaces where movement occurs yet no contact with the paper’s surface is made. Motion capture locates the gesture of writing in three-dimensional space – a stage, rather than a page – and in this case, the resulting lines of movement, are displaced from the pen’s nib that inscribes on the paper’s surface. They surround the text as a kind of para-writing rather than asemic writing: made unconsciously and simultaneously with a text that conveys meaning. The continuous motion of writing is recorded through a sequence of lines in which signification shifts towards the primacy of movement, as legible words slip in and out of view. Thus, in this collaboration with technology, gesture generates lines at the seam between writing and drawing.

These records of an event of writing, reveal non-writing as well as writing – the rhythmic patterns of motion as the hand forms words. In Fagg’s model for teaching handwriting to children pattern and repetition are a means to develop fluency and ease of movement. The order and regularity of words produced through handwriting exercises evolves over time into more individual expression, and the connection of writing to dance through movement manifests in the whirling, looping bends and arabesques that appear in the space of writing.

Both the unregistered movement of the dancer and the space of the page feature as preoccupations in the fragmentary writings of Mallarmé. Observing the dancer on the stage in the theatre, invites a further equation between movement and writing, explaining dance as ‘a kind of corporal writing’ and ‘a poem independent of any scribal apparatus’ (2009, 130). Motion capture provides the means to make visible such unregistered expressions as line is used to make a translational shift from movement into drawing.

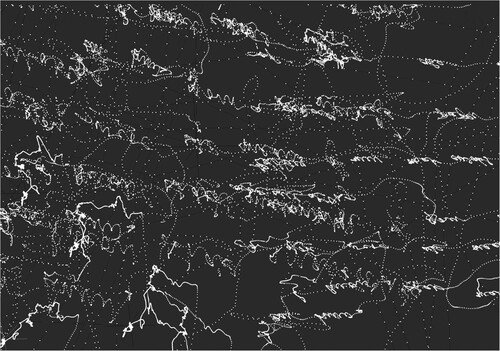

To become line, a sequence of actions is performed on the x, y and z data captured by the motion sensors. First, each marker becomes a motion path; next a mesh, in the form of a collection of vertices is attached to the path. At this point, replaying the movement across the timeline produces a trail of white dots. This trace is the antithesis of Mallarmé’s conception of writing as ‘black upon white’ and ‘always applied to paper’ (Citation2007, 216). He says that ‘one doesn’t write, luminously, on a dark field; the alphabet of stars alone does that’. The software provides this dark three-dimensional space in contrast to the two-dimensional white page, and the vertices appear like Mallarmé’s stars in the infinity of the sky.Footnote3

The sequence proceeds as particles are emitted from the vertices, and finally the addition of a coded script connects the particles into a continuous path. Unlike the physical handwritten letter to Anni Albers, these contextual traces exist as a series of virtual lines in three-dimensional space. Thus, they are framed by software that allows them to be objectively examined from different viewpoints.

The letters are not intended for publication, but the drawings they have generated, in concert with Albers, acknowledge the importance of making and materials to articulate knowledge in a way that is central to makers who may not choose to work with words. Like all forms of writing and drawing that commit a trace to the page or any equivalent, these lines are affirmation of a once present tense, and an experience of being in the world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sally Morfill

Sally Morfill is an artist and Senior Lecturer in the Department of Design at Manchester School of Art, Manchester Metropolitan University where she coordinates the postgraduate programmes. Her work uses drawing as a tool for translation and investigates the relationship between drawing and different aspects of language, as found in and between speech, movement, and writing. Working with drawing across multiple media, performance, and installation, and often collaboratively, she employs movement and language to reflect on the dynamics and spaces created in our attempts to communicate. Since 2007 Morfill has been a member of the artists’ collective, Five Years. She has exhibited nationally and internationally including in Slovenia, Germany, Austria, China and the USA. Recent published writing includes ‘Romance and Contagion: notes on a conversation between drawing and dance’, in Artistic Research in Performance through Collaboration (Eds. M. Blain, H. Minors), Palgrave, 2021. ‘I am not listening: poem object as hybrid publication in the post-digital era’ co-authored with Ana Čavić and Tychonas Michailidis, will be published in 2023 by Smithsonian Scholarly Press in Story Work for a Just Future – Co-creating diverse knowledges and methods within an international community of practice (Eds. A. Liguori, P. Rappoport, D. Gachago).

Notes

1 Ancient Writing (1936), Open Letter (1958), Haiku (1961), Code (1962) and Epitaph (1968) are examples of the text-related titles Albers gave her weavings.

2 Asemic writing eliminates any linguistic meaning, dispensing with familiar alphabetic signs at the same time as visually alluding to writing. For a thorough discussion of Asemic writing, see Peter Schwenger’s 2016 publication: Asemic: the art of writing, published by University of Minnesota Press.

3 See opening double-spread (dark image): Screenshot showing vertices punctuating the motion paths (Morfill, 2023).

References

- Flusser, V. 1991. The gesture of writing. Flusser Studies. Accessed January 9, 2014. http://www.flusserstudies.net/sites/www.flusserstudies.net/files/media/attachments/thegesture-of-writing.pdf.

- Flusser, V. n.d. Writing. Accessed November 11, 2022. http://flusserbrasil.com/arte179.pdf.

- Mallarmé, S. 2007. Divagations. Translated by B. Johnson, 2007. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mitchell, V. 1997. “Textiles, Text and Techne.” In The Textiles Reader, 2012, edited by J. Hemmings, 5–13. London: Berg.

- Sassoon, R. 2007. Handwriting of the Twentieth Century. Bristol: Intellect.