ABSTRACT

This article provides a critical introduction to a double issue of Journal of Visual Art Practice. The issue, titled ‘Situations of Writing’, explores the intersections of art practice, hybrid forms of writing, and knowledge production. It draws together a variety of contributions that variously delve into the complexities of writing with and around images, emphasising experimental approaches, and reimagining traditional scholarly publishing. This introduction situates the key problematics, drawing upon historical examples, but within the present-day context of academic, digital publishing. The editors urge practitioners to challenge conventional modes of academic writing, inviting makers, authors and readers to have a stake in an evolving landscape of art practice and visual culture studies. Setting out a combined exploration (and making) of form, content, and the structures of address, this special issue paves the way for new possibilities in scholarly research and knowledge dissemination.

This article provides a critical introduction to a special double issue of Journal of Visual Art Practice, under the title of ‘Situations of Writing’, and brings together 12 contributions, representing a variety of topics and modalities. Indeed, each of the contributions offer something different, giving rise to a complexity of dialogues, reflections and production processes. This was entirely as hoped for, as built into the proposition for the issue in the first place. In bold, at the top of our ‘call for papers’ was the following line: ‘This is an invitation to make an article … The emphasis on “making” an article is deliberate. It is to imply an approach based upon a form of art practice and/or a hybrid form of article writing’.

While the specific process of making this issue spans three years, the themes and issues have been a shared interest for us both over a period of a decade. In 2014, for example, we convened an AHRC-funded project, Looking at Images: A Researcher’s Guide, concerned with the development of skills in image-related research. The project culminated in an event at the British Library to launch a collaboratively produced ‘Researcher’s Guide’ e-book.Footnote1 It was at this event we first publicly spoke of ‘situations of writing’. While there has been an explosion of interest in visual culture and imaging techniques over recent decades (both within and beyond the arts and humanities), what is often missing is a positive and challenging ‘picture’ of the image in and as research (Elkins Citation2003; Citation2007; Elkins and Mcguire Citation2013; Manghani Citation2008; Citation2013).

The text does not “gloss” the images, which do not “illustrate” the text.

From Roland Barthes’ Empire of Signs (Citation1982), no page.

Since the event at the British Library, albeit in the manner of Bouvard and Pécuchet (Flaubert’s comical copy-clerks, who shift from one domain of knowledge to another in the vain hope that one set of underlying questions will be resolved by another), we have tried to realise our ambitions for situations of writing using numerous methods. Early on we looked at the prospect of a book series, but quickly found publishers (while certainly interested) struggled to think outside of their usual production templates and remained reserved about writings that were heavily dependent on image or alternative layouts. Later, we devised an elaborate (and generally very well received) funding bid, which would have involved artists making new work alongside the development of print-based publications. Aspects of the bid were trialled as part a series of workshops under the umbrella ‘The Three Dimensional Page’ at Flat Time House, Peckham – the studio home of John Latham (1921–2006). In the end funding was not secured for the larger project, but the underlying premise was for ‘live’ critical enquiry into the process of making and its outcomes. Inevitably, perhaps, the dilemma was a societal one: whose problem is this; why the need for government funding? Why, indeed, were we concerned with the methods and materials of making publications, when we have ever greater means of production through sophisticated digital techniques? However, the problem, is precisely not a technological one. Rather, at stake is more a political aesthetic. A deep-rooted question about the modes and modalities of enquiry.

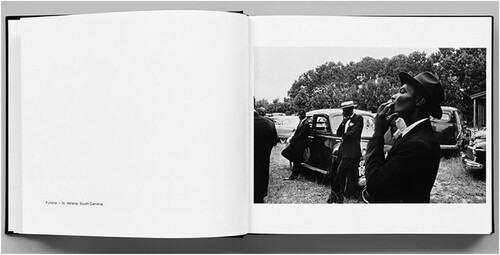

Take, for example, Robert Frank’s The Americans, a seminal photo-essay published in Citation1959. It has long been revered for its subtle (and dark) portrait of 1950s America. The book has a very rigid, clean-design template. Each section of the book is ‘quietly’ introduced with a photograph showing the American flag in one form or another (and embedded throughout are numerous images featuring crosses). Following which, each double-spread adopts the same layout, with one photograph per page, one after another (with minimal captions). Frank worked with the French publisher Robert Delpire, who explains their method as follows:

He came back to me with a selection, and we very quickly did a layout of the book. People always imagine you need two or three weeks to do that. We did it in one day. We spread the whole book out on the floor, as you always did at that time, on all fours. As there were no double-page spreads, just one picture after the other, we quickly agreed how the photos should be displayed. And that’s how we did it. (cited in The Genius of Photography, BBC Citation2007)

The intuitive and swift approach to making The Americans is easy to look past. Not least as the genius of the design is the lack of distraction. The consistent layout, one picture at a time, means that there is no need to look at more than one picture at a time. Frank deliberately prevents us from letting our eye jump from one picture to another. Yet, equally, as you turn each page the retinal retention of the preceding image lingers upon the next. In this way the book is a form of ‘movie’; we are encouraged to move through it at a constant speed like a reel of film. The richness of each picture – with their unusual elements, poignant moments and striking ambiguities – accumulate as the pages turn, as if we are on the road trip ourselves. The design of the book, the situating of the images as a technique, is as critical as the photographs themselves. And importantly, through this design we are drawn into the situation of the pictures themselves without being distracted by the ‘mechanism’ of the book.

While the collaborative editorial process (over a single day) seems almost too simple to warrant explanation, it captures a level of engagement and trust between artist and editor (as individuals but also as ‘mediators’ at different points within a cultural ‘field’ (Bourdieu Citation1993)) that sadly is often lacking today in publishing. Writers must submit their Word documents to a publisher without adornments, and typically without showing any sense of the flow of image and text. A production process (frequently outsourced) will then ensue, ideally with as little interruption and interlocution with the author as possible. Always ‘time is money’ – placing evident pressure on any changes and amendments. It is not uncommon for a publisher to return proofs with stern remarks that any further changes must be minimal, otherwise authors may be liable for additional costs.

The ‘work’ that goes into writing, not least materialising writing, is often not seen, yet is critical to the way we produce, develop and disseminate knowledge. The Americans is beguiling. The apparent ease with which Frank and Delpire ‘did it’ – i.e. undertook the subtle process of selection, ordering and design – makes it all too easy to turn our attention away from the situatedness of writing. Yet, what were the conditions that enabled Frank to work, to then bring his work to Delpire, and for the two of them to publish the book? The book appeared first in France in 1958 and a year later in America (with an introduction by Jack Kerouac). It was immediately met with harsh criticism, despite ending up a modern classic of photography and social commentary. As Delpire remembers it:

It was very badly received … it didn’t go down well in America where the critics said: who is this insignificant Swiss descending on the Americans? Coming to explain to them that the American Way of life isn't as extraordinary as people say. It was like that. We lost money, but it wasn't that big a deal. The kind of book that I do loses money all the time so I wasn't surprised. (cited in The Genius of Photography, BBC Citation2007)

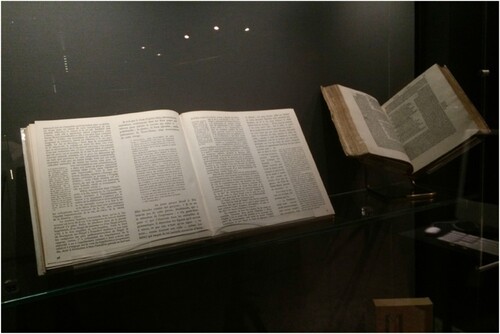

Derrida’s Glas (Citation1974), with Dante’s Divine Comedy (Citation1520) on the right. From the exhibition ‘The Book The Object’ (2016) Special Collections Gallery, University of Southampton

In her ‘notes on method’ in the preface to Dreamworld and Catastrope, Buck-Morss suggests the book can be ‘read on several levels’, whereby:

It is a theoretical argument that stresses commonalities of the Cold War enemies … . On another level, the book is a compendium of historical data that with the end of the Cold War are threatened with oblivion. […] The book is also an experiment in the methods of visual culture. It attempts to use images as philosophy, presenting, literally, a way of seeing the past that challenges common conceptions as to what this century was all about. The purpose of the book is to provide understandings, and subvert them. (xv).

It is difficult to place exactly the position Elkins is ‘voicing’ at this stage. As will be noted below, there can be an ambiguity of the ‘structure of address’ (Butler Citation2004, 130), i.e. how language, discourse and perspectives become voiced and reanimated in a form of passive or reported speech. In short, we can say Elkins appears more to vocalise an account of a dominant discourse, without necessarily accepting the position. Indeed, around 2011, he publicly declared a move away from writing about art and the image, towards writing with the imageFootnote2, which ultimately led to publishing a novel, Weak in Comparison to Dreams (Elkins Citation2023). As such, Elkins’ work has been a vital force and influence in the development of our project, Situations of Writing. His contribution to this issue is critical in this sense, and includes both an account of what has been at stake in re-situating his approach to the image, and provides an extract from his complex, image-text multi-volume novel. Nonetheless, the argument Elkins’ sets out in Visual Studies: A Skeptical Introduction, is an important reminder of an enduring critique within academia, whereby the image is denied credibility. In this respect, returning to the case of Buck-Morss, what scholars seem unable to accept is the fact that she actually wants to incorporate the unreliable nature of images into critique. Buck-Morss wishes to allow for the fascination of the image (rooted for example in a reading of Walter Benjamin, on the dialectic of the image, of the Denkbild) to enable and complicate the kind of cognitive, critical experience of which Benjamin was an advocate (Buck-Morss Citation1989). In this way, Buck-Morss undoubtedly ‘entertains’ the possible nostalgic meaning of the images she uses as a means to comment upon the comparative role of modernist utopian narratives. What is interesting about Buck-Morss’s work is that she allows her critique to run in different directions, before coming to ‘completion’ as fashioned by her particular scholarly engagement. It is worth noting, the instability of the image is deployed to much acclaim in the works of W.G. Sebald. It is perhaps significant that these works are positioned as fiction, despite operating in a sophisticated ‘space’ of critical enquiry, regarding topics such as memory and storytelling.

Some situations …

Situations of Writing can be understood as a project about writing with and around images; the ‘interlacing’ of image and text; and, importantly, about placing experimental forms of writing in formal circuits of knowledge production. The project is attuned to writing being ‘situated’ in terms of new visual literacies, the convergence of print and electronic-based publishing, and the political condition and forms of address within the arts and humanities. It is an attempt to place creative practices into the somewhat restricted ecosystem of scholarly writing and publishing; to extend the research process into print. We are compelled to ask the question of how we are to understand such practices when framed as research; and how, in a broader context, what it is we want such research and accrued knowledge to look like, now and in future publications. In the context of contemporary post-digital publishing, a tension exists between greater means to manipulate text, image and layout as set against the increasing propensity for strict design templates (which, in part, has been prompted by the demands of open access online publishing).

The argument made (and visualised) in Sunil Manghani’s Image Critique (Citation2008) is that despite the interdisciplinary make-up of visual culture studies and its challenge to the orthodoxy of textual analysis, the field has prompted very little innovation in terms of forms of writing, production and dissemination. This echoes James Elkins’ Visual Studies: A Skeptical Introduction (Citation2003), in which he urges the field to be ‘more ambitious about its purview, more demanding in its analyses, and above all more difficult’. An underlying suggestion is that we need to write more ‘ambitiously’. An example of the problem can be made with the work of art critic and writer John Berger, who emerges as one of the most widely cited inspirations to the field. Yet, as Elkins (Citation2003, 121) argues, ‘no art historian or specialist in visual culture writes anything like Berger.’ Indeed, no one seems willing to experiment in the same way with the form and style of writing and production. Yet, ‘why not’, Elkins asks, ‘when those signs of the engaged writer are part and parcel of the philosophy of the engaged viewer that Berger himself helped bring into art history?’ (122). Elkins has since publicly renounced his role in art history. He gives several reasons, the most important being that:

Art historians, theorists and critics continue to write along well-defined, disciplinary paths. We cite poststructuralist philosophers on the idea of writing, but our own writing continues to be restricted by disciplinary expectations. The few authors who permit their writing to become more experimental (such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, John Berger or Hélène Cixous) tend to have their texts viewed as sources for art history, rather than examples of art history. One result of this is a deep disparity between the ways writing is taught and interpreted inside and outside art history, art criticism, art theory, visual studies and related fields. (Elkins Citation2014a, 15)

With much more competition for texts to be read, the tendency is for smaller units of reading and far less sophistication in reading formats, including the relationship between text and image. Further critical perspective can be drawn from Judith Butler’s Precarious Life (Citation2004), which prompts consideration for how we situate and ‘address’ the arts and humanities more broadly. She recounts a university committee meeting in which it is suggested ‘no one is reading humanities books anymore’ and that the ‘humanities have nothing more to offer’. It is not clear if this is a view held by the speaker, or simply a ‘myth’ the speaker is reporting upon. As Butler notes: ‘what I would like to see and hear return is a consideration of the structure of address itself. Because although I do not know in whose voice this person was speaking … I did feel that I was being addressed.’ Situations of Writing is concerned specifically with the structures of address that Butler (and others) refer to, which in the case of arts practice requires further rigour in how we understand and articulate its significance as a distinct mode of address and means of research. Consequently, this special issue seeks to investigate different forms and modalities of writing and composition in order to understand and give affordances to different architectures of knowledge and dissemination research for wider and more sustained circulation in an academic framework.

Situating the journal

There is of course a rich history of experimental and creative approaches to critical writing, art making and publishing. Photo-essays and other key publications from the early to mid-twentieth century emerged as important statements within the broader intellectual and political discourse. These publications were often distinctive for their complex interplay of word and image, alternative layouts, and new forms of writing and differing signification systems. As noted, John Berger remains one of the most widely cited inspirations to the field of visual studies, yet contemporary art historians or specialists in visual culture appear unwilling (or unable) to experiment similarly with the form and style of writing and production. Again, such work is typically only taken as a source for scholarly consideration, not as scholarship itself. As Elkins notes, a wide array of practice PhDs produce art that ‘is considered as propositional: it embodies, or suggests propositional knowledge’, yet it is still largely the case, ‘all such programs [of study] also require dissertations’ (in Elkins and Mcguire Citation2013, 50). He goes onto mention an interesting quirk of history in this context: ‘[a] fascinating and under-studied example of the claim of images alone can argue comes from Roland Barthes, who in 1979 approved a PhD that consisted only of images’ (ibid; see also Rowe Citation1995).

A further consideration is that the maturing of practice-based PhD programmes internationally has given rise to a new generation of researchers (Elkins Citation2014b), yet there is a paucity of appropriate outlets to showcase the work that is being produced within and beyond these programmes (Manghani Citation2021). This special issue – through its layered investigations into making, writing/designing and reading – seeks to assert a new degree of authority for practice research; to provide a more confident ‘frame’ and critical editorial scrutiny that is currently lacking. In the contemporary context, this can be understood to be working toward an expanded notion of writing, equally concerned with form and content, as befits the aims and scope of the Journal of Visual Art Practice (Birkin, D’Souza, and Manghani Citation2021).

Unlike the seminal publications of the twentieth century, composed through careful consideration of the special relationship between form and content, contemporary publishing is framed through Internet dissemination, which deliberately separates form from content to allow information to be aggregated across multiple platforms. Yet, if we look back to Berger’s ground-breaking book Ways of Seeing (Citation1972), a paradigm of experimental publishing on visual culture and art history, we are reminded it was adapted from a television series (Guins, Kristensen, and Pui San Lok Citation2012). The series was a bold excursion through an everyday contemporary medium that shaped the form and content of the subsequent book. Ways of Seeing is essentially a modified script, a ‘voice-over’ with a ‘streaming’ of images. At one and the same time it chronicles and performs the specificity of the original medium through non-standard layout and language, such as the use of extremely short paragraphs, lists and lengthy passages of quotation. There are chapters made up entirely of images that offer an important space for thinking around, and with, images. In keeping with the underlying argument of the book, which drew upon Walter Benjamin’s key essay on the artwork in the age reproducibility, it takes the television series as a ‘situation’ for writing, which parallels our post-digital situation whereby artists and writers are afforded a whole new set of freedoms based upon digital media, but which equally can become the constraints upon those same freedoms. From this perspective a key consideration is how old and new technologies co-exist, transition and interact.

In turning to the context of this journal, concerned as it is with visual art practice, freedoms of layout and typesetting are critical, in order to allow for scholarly writing in its full material sense. Working closely with the journal’s Production Editor and typesetters, we have sought to close the gap between the constraints of academic publishing and the varying research ambitions of the contributors, in order to formulate such research for wider and more sustained circulation in an academic framework. The editorial role inevitably needed to take on an extra dimension, as we were compelled to inhabit a new space between author and production team, to facilitate a publishing outcome that would signal the status of the creative act. Inside this space, negotiations took place that have, by default, remained hidden. As editors, we feel that it is important to share some of what was learnt through this process, in order to provide a framework (and a certain positivity) for future publications of this kind, while at the same time being open and transparent about the problems we encountered and the strategies we used to overcome them.

Two articles in the collection are interviews (Lynch and Williamson dialogue on disability and arts; and D’Souza and Manghani’s conversation with the Mumbai-based artist Jitish Kallat), and a further two are ‘metatexts’, focusing on existing texts, the first being Baas’ situating of Marcel Duchamp’s notable essay, ‘The Creative Act’ (1957), and Özmen’s exploration of the image as preparation in Hanya Yanagihara’s novel A Little Life (2015). In each of these cases, the situating of writing is more aligned with the critical considerations of ‘structures of address’, and in terms of production could be handled through the usual journal procedures. Yet, the majority of contributions needed some degree of operational control in respect of layout. There are articles, such as those by Matthew Allen and J.R. Carpenter, which break the conventions of punctuation and paragraph use, and these would normally have been ‘corrected’ by automatic systems used by the publishers. We therefore requested that these systems should not be used in a wholesale way for this issue. Although some publisher conventions, such as the placement of affiliation, abstract and keywords at the front of the articles could not be changed, we were able to include a page break before the final metadata so that the work could stand alone. This was an important consideration in the case of the conceptual pieces of Jane Birkin and Christion Bök, Victor Burgin’s quiet, expansive layout, and Sally Morfill’s visually poetic and gestural text/image fusion.

Screenshots from ‘Victor Burgin: image and text in changing times’, available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GnKMwnYA4K0

Some authors had strict requirements in terms of image placement (this was to be expected) and these inevitably brought with them a range of problems. Victor Burgin’s piece is a translation from a filmed slideshow with voice over, so ‘white space’ became important in recreating the pace and the pauses of the original presentation in order to make time for contemplation of the 40 images. In contrast, James Elkin’s article needed to flow and fill the page, while at the same time the exact placement of images at points in the text was critical to the sensibility of the piece. Since we had no control of the basic page size and font used by the journal, this could only be achieved by making minute changes to the image sizes and the gaps around them. Matthew Allen had one significant request: that the references to the images should be on the same page as the images they point to. This may sound simple enough, but the sheer bulk of images and the irregular scattering of references through the text required thoughtful grouping and sizing of images to make this work, and good lines of communication with the Production Editor.

Dutch artist Andrea Stultiens, who has extensive experience in the design and publishing of artists’ books, with the relative freedom that process brings, here appears to exploit the academic publication process by making extensive use of notes as a writing device. It was difficult to predict how this plan would work out in production, with the placement of images remaining an important consideration alongside the possibility of large blocks of notes jumping over pages. We were able to give realistic advice to the author about what might happen and how to mitigate problems, suggesting adding an extra spread and so giving more space to the text in order to cushion any unexpected text overflow. While there was an element of ‘flying blind’ with this piece, the outcome was good. Again, good levels of trust and understanding between the editors and Production Editor was key.

It was clear from the beginning that if we were to circumvent some of the publisher’s usual systems and procedures, we would need to provide clear, visual instructions to show what the authors wanted to achieve in terms of their wide-ranging, experimental approaches. An important ‘tool’ in the process was the ‘mock-up’: in most cases a layout was provided in draft form using desktop publishing software, and sent as an annotated PDF to serve as a guide for the typesetters (along with the usual word document and image files). These layouts were sometimes made by the author, with advice from us on page size, margins, font, line spacing and so on. However, in most cases the editorial team undertook this task, in direct and frequent communication with the authors. This, alongside the flagging of any unusual layout features to the Production Editor (who was extremely sympathetic to the aims of this Special Issue) proved to be a successful strategy, even if some tweaking was required after the first proof.

Coda

Situations of Writing has taken us on a journey, during which we have traversed the convergence of visual literacies, the changing landscape of publishing with the rise of digital media, and the strained political conditions of the arts and humanities. Throughout, the aim has been to explore (and keep open) the complexities of writing with and around images; the interlacing text and image; and placing experimental forms of writing within formal circuits of knowledge production. Ultimately, the ability to bring this double issue of Journal of Visual Art Practice to fruition is testament to the commitment and collaboration of contributors, editors and producers, all with the view to push the boundaries of scholarly writing in ways that truly embrace the potential of creative practices.

We are deeply grateful to our contributors, who have each provided wonderful and varied ‘texts’. In bringing these together as a collection, so demonstrating the differing situations of writing, we hope to have highlighted the need for and gains from more ambitious and demanding approaches. The pioneering work of John Berger and other recent scholars (such as Susan Buck-Morss and James Elkins) have inspired us to dare to experiment with the form and style of writing and production. However, there remains a resistance within academia to fully embrace and engage with the potential of images, alternative layouts, and interdisciplinary approaches. This resistance is felt despite the fact that the means of production have seemingly never been more agile (at least on a technical, if not an economic level). We hope this special issue provides further inspiration for innovative research, inviting scholars to be bold in their work, to explore writing in its full material sense, incorporating formatting, illustration, design, and typography as integral parts of the scholarly discourse.

Finally, then, when reflecting on the challenges and achievements encountered in making this special issue, it is evident that the relationship between form and content, the structures of address, and the ability to embrace technological advancements while respecting traditional modes of publication are perennial critical considerations. Looking to the future, we encourage scholars as creative practitioners to continue to challenge the forms of writing and research. If nothing else, Situations of Writing can be read as a catalyst for reimagining scholarly writing, inviting us to embrace the complexity, richness, and possibilities that lie at the intersection of art practice, hybrid forms of writing, and the pursuit of knowledge. It is through these critical practices that we can maintain a more expansive, inclusive, and transformative academic landscape.

For me, each has been no more than the onset of a kind of visual uncertainty …

From Roland Barthes’ Empire of Signs (Citation1982), no page.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jane Birkin

Jane Birkin is an artist, designer and scholar. She is a Research Fellow at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton (UK) and has worked in archives for many years. Birkin’s art practice and writing functions at the intersection of text and image, combining media culture and techniques of the archive, as well as contemporary discourse on art, photography and conceptual writing. She is specifically concerned with institutional description techniques that define and manage the photographic image, and her academic monograph Archive, Photography and the Language of Administration, was published by Amsterdam University Press in 2021.

Sunil Manghani

Sunil Manghani is Professor of Theory, Practice & Critique at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton (UK). He is Editor of Journal of Visual Art Practice, and Managing Editor of Theory, Culture & Society. His books include Image Studies (2013), Zero Degree Seeing (2019); India’s Biennale Effect (2016) and Farewell to Visual Studies (2015). He curated Barthes/Burgin at the John Hansard Gallery (2016), along with Building an Art Biennale (2018) and Itinerant Objects (2019) at Tate Exchange, Tate Modern.

Notes

1 Looking at Images: A Researcher’s Guide (edited by Jane Birkin, Rima Chahrour and Sunil Manghani, 2014), available online: http://blog.soton.ac.uk/wsapgr/looking-at-images/.

2 See two book projects, Writing with Images and What is Interesting Writing in Art History?, available online: https://jameselkins.com/writing-with-images/.

References

- Barthes, Roland. 1982. Empire of Signs. Translated by Richard Howard. London: Jonathan Cape.

- BBC. 2007. The Genius of Photography, Episode 4, ‘Paper Movies’. BBC Productions. https://archive.org/details/tGoPhoto/BBC+The+Genius+of+Photography+-+01(04+-+Paper+Movies.mp4.

- Berger, John. 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books.

- Birkin, Jane, Ed D’Souza, and Sunil Manghani. 2021. “A Visual, Journal Practice: Journal of Visual Art Practice, Twenty Years on.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 20 (4): 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702029.2021.1995928.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Buck-Morss, Susan. 1989. Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Buck-Morss, Susan. 2000. Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of the Mass Utopia in East and West. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Butler, Judith. 2004. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. New York: Verso.

- Dante, Alighieri. 1520. Opere del divino poeta Danthe … [Divine Comedy]. Venice: Per Miser Bernardino Stagnino da Trino de Monferra.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1974. Glas. Paris: Éditions Galilée.

- Elkins, James. 2003. Visual Studies: A Skeptical Introduction. New York: Routledge.

- Elkins, James, ed. 2007. Visual Practices Across the University. München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

- Elkins, James. 2014a. What is Interesting Writing in Art History? [Carnegie Lecture Series]. University of Edinburgh. https://www.carnegie-lectures.eca.ed.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/James-Elkins-Carnegie-Book.pdf.

- Elkins, James, ed. 2014b. Artists with PhDs: On the New Doctoral Degree in Studio Art. 2nd ed. Washington: New Academia Publishing.

- Elkins, James. 2023. Weak in Comparison to Dreams. Los Angeles: Unnamed Press.

- Elkins, James, and Kristi Mcguire. 2013. Theorizing Visual Studies: Writing Through the Discipline. New York: Routledge.

- Frank, Robert. 1959. The Americans. Paris: Robert Delpire.

- Guins, Raiford, Juliette Kristensen, and Susan Pui San Lok. 2012. “Ways of Seeing 40th Anniversary.” special issue of Journal of Visual Culture 11 (2), https://journals.sagepub.com/toc/vcua/11/2.

- Manghani, Sunil. 2008. Image Critique and the Fall of the Berlin Wall. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Manghani, Sunil. 2013. Image Studies: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Manghani, Sunil. 2021. “Practice PhD Toolkit.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 20 (4): 373–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702029.2021.1988276.

- Rowe, W. 1995. “The Wordless Doctoral Dissertation: Photography as Scholarship.” The Cal Poly Pomona Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 8 (Fall): 21–30.

- Stone, Nick. 2001. “Susan Buck-Morss, Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West” Radical Philosophy 107 (May/June): 48–50.

- Sturrock, John. 1987. “The Book is Dead, Long Live the Book!” New York Times, September 13. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/13/books/the-book-is-dead-long-live-the-book.html.