ABSTRACT

In the 1920s and 30s, a criminal investigation followed by a trial against a group of allegedly homosexual men was launched in Gothenburg, Sweden. Almost a century later, Swedish artist Conny Karlsson Lundgren engages with these events in a multifaceted two-part installation and performative work that borrows the title from the investigation, The Gothenburg Affair (Göteborgsaffären). In this article, we describe how the investigation was conducted during a time in which the science of criminology expanded to envelop new technologies and methods of identification and categorization. Tools such as new uses of photography, the portrait parlé, and Kretschmerian body types were implemented to identify criminal individuals and behaviors and place them within a particular category of criminality or pathology. In his works, Karlsson Lundgren conspicuously brings out sensual and sexual details of the archival material and inverts the denigrating and stigmatizing ways in which these details were used in the source material. In the article, we describe the strategies though which Karlsson Lundgren’s work transforms aspects of the archival material and in this way intervenes in history to continue a resistance found between the lines of the archival material itself.

Introduction

In 1937, a criminal investigation against a group of allegedly homosexual men was launched in Gothenburg, Sweden. With minute detail, the police used methods of criminology, forensic psychiatry, physiognomy and phrenology to map the typologies, actions and relationships of the loosely connected group that was considered to form the ‘network’.Footnote1 As homosexuality was criminalized and subject to judicial punishment, they were eventually prosecuted in a high-profile trial, where some were sentenced to prison while others were admitted to psychiatric treatment. The prosecution and punishment of the men can be connected to the exposure of a private party by an under-cover journalist a decade earlier.

A century later, in 2021, Swedish artist Conny Karlsson Lundgren presents the events around the exposure and the investigation of the group in a multifaceted two-part installation and performative work that borrows the title from the investigation, The Gothenburg Affair (Göteborgsaffären). The work explores visibilities and representations of sex and sexuality by delving into this event and its social, scientific and activist aspects as recorded (but hitherto hidden) in local and national archives – and as mediated and experienced by the contemporary performers and audience. In this article, we discuss the artistic strategies through which Karlsson Lundgren’s The Gothenburg Affair approaches the criminalization of the gay men by also referring to other of the artist’s scenographic works that perform a queering of various archives. Furthermore, we contextualize the historical investigation by looking at the methodologies of criminology and related sciences at the time, with specific attention to the roles of photography and other means of visualization. Finally, we argue that Karlsson Lundgren’s works inverts the villainizing representations in the exposing article and the criminal investigation by unfolding a counter-visual resistance of erotics concealed in the material itself.

Sensual evidentiality

The first part of Karlsson Lundgren’s work, Prologue (The Gothenburg Affair), evolves around a magazine article by Barthold Lundén from 1924, in which some of the same people figure as in the criminal investigation some years later.Footnote2 In the article, Lundén describes how he crashes a private party outside Gothenburg. The party was arranged by two brothers, Karlsson, and their group of friends, who Lundén labels as a ‘homosexual plague hearth’ and which eventually came to be known as the ‘network’ to be investigated.Footnote3 In an affective and detailed wording Lundén relays glimpses of what he sees as he enters the home. Scenes of the party are described in a language that is saturated with both disgust and fascination, for instance:

There two were seated cheek to cheek with their arms tenderly wrapped around the little waist … There another leaned his head caressingly against his neighbor’s chest … There was another pair that sat so tight, close to each other.Footnote4

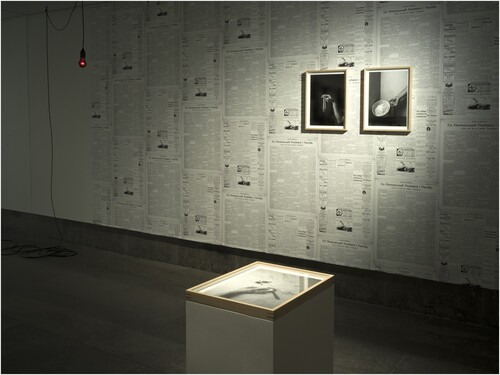

Figure 1. ‘Prologue (The Gothenburg Affair)’, Conny Karlsson Lundgren, 2021. Photo: Cecilia Sandblom/Hasselblad Foundation.

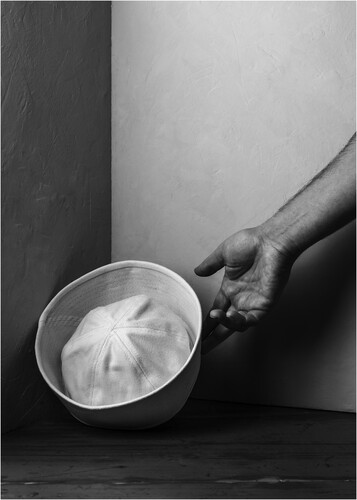

Figure 2. ‘Prologue (The Gothenburg Affair): There was another pair that sat so tight, close to each other’, Conny Karlsson Lundgren, 2021.

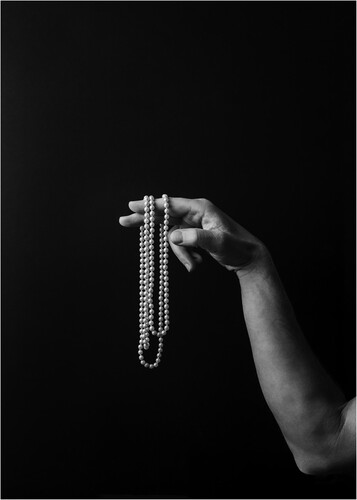

Figure 3. ‘Prologue (The Gothenburg Affair): There another leaned his head so tenderly against his neighbor’s chest’, Conny Karlsson Lundgren, 2021.

Figure 4. ‘Prologue (The Gothenburg Affair): There were two sitting, cheek to cheek, with arms tenderly entwined around the tiny waist’, Conny Karlsson Lundgren, 2021.

By the 1920s, photography had become one of the most important and indispensable tools for criminology, which advanced as an interdisciplinary science in the interwar period. By then, photography was applied on most levels in police field work, lab investigations, forensics and surveillance. New technologies not only enhanced the medium’s already asserted scientific objectivity as evidence in matters of identification. Photography also facilitated the mobility of both the crime scene detective and the analytical criminologist as well as the sharing of visual information among police units. Albeit its alleged objectivity, crime scene photography was both performative and coded, exemplified in the kind of images that include a representative of the police who points to a specific detail and by that gesture of the index finger and thus directs the gaze of the viewer.Footnote5 In addition to referencing both mid-war modernist aesthetics and the increasing use of photography within criminology, Karlsson Lundgren’s still-lifes also evoke a charged sensuousness around the three objects. This sensuousness can be detected in the party as read between the lines of Lundén’s article, but also in the words of the journalist himself – as evidenced by the quotes from his descriptions of the party above. Even as Lundén describes his aim to impose fear and stop the group from wanting ‘to carry on in such a cheeky manner, or demonstrate their despicable urges too ostentatiously and openly’, it seems that he cannot help but to reveal a certain fascination with the intimacy and enjoyment that he observes.Footnote6

In one of the still-life photographs, the forearm and hand of the artist is seen as one finger gently reaches out to touch a cream puff on a spoon, as the prunes and their sauce form an abstract pattern nearby. In another, two fingers hold up a pearl necklace with the ‘feminizing’ gesture of a tilted wrist (). A gesture with a long history in stereotypical representations of gay men considered ‘effeminate’, which Karlsson Lundgren has addressed in an older work called Limp Wrist (2012) – a series of 40 photographs where the artist portrays people from a larger queer and feminist context who have had an influence on him. These artists, writers, activists, friends etc. are manifested only by the artist mimicking their hand gestures. This earlier work already hints at the strategy of exploring, reclaiming, and opening up for the sensuous potential of characteristics that has otherwise been used in stigmatizing typologizations of sexual minorities.Footnote7

The three still-lifes in Prologue (The Gothenburg Affair) make full use of photography’s particular ability to produce a finer grain rendition of details and texture; in this case the moistness of the prunes, the softness of the cream and the smoothness of the pearls. The increasing emphasis on photographic technologies’ evidentiary abilities in the early twentieth century placed photographs at the side of optics in what Elsbeth H. Brown and Thy Pru refer to as the ‘opposition between a feeling haptic and a detached optics’ (2014, 16). This perception of photography as a purely optic phenomena – and therefore more trustworthy in terms of evidence – only increased throughout the rest of the twentieth century. Lately however, several photography theorists have been questioning the perception of the medium as a purely visual practice and instead turn their attention toward ways in which photographs engage all our senses, and the inseparability of touch and vision in particular (Olin Citation2012; Brown and Pru Citation2014). From this perspective, describing a photographic experience in terms of texture (the softness of the cream and the smoothness of the pearls) is not a matter of translating a visual experience into a tactile one, but rather an expression of the inevitable synestheticity of photographic experience. As such, the visual perception of the smoothness of the pearls is also a sensation at one’s fingertips, and the abstract patterns of the prunes and their sauce become the conduit of an olfactory sensation. By referencing the detached optics of crime photography, at the same time as emphasizing the haptic allure of photography, Karlsson Lundgren unsettles the divide between the haptic and the optic – on which the evidentiary promise of the photographic technology to a large extent relies.

At the same time as criminology (and other sciences, such as the pseudo-sciences of racial biology, as we explore below) increasingly found new uses for photographic technology to document and reveal evidence of crime, photographers experimented with its potential for exploration of new subject matters and artistic expression. Even though the medium had existed for nearly a century, it wasn’t until this time that photographers and artists fully began to embrace its particular aesthetic (as well as social and political) potential. They experimented with light, perspective, new subjects matters and abstraction, such as cropping and framing a single body part. This ‘new vision’ had close parallels to the scientific visual practices, which became evident in the now iconic Film und Foto (FiFo) exhibition 1929 and particular in László Moholy-Nagy’s radically modernist curation of the photographic display. In Karlsson Lundgren’s still-lifes, the modernist aesthetics is put to use with a result that is ostentatiously and openly sensual, at the same time as it mocks the idea of criminological evidence in this setting to be recorded. In a ‘cheeky manner’ (in the words of Lundén himself), they bring out both the covert and overt sensuality of the article and the party that it describes, as well as the ‘evidence’ of the investigation to be, such as the erotic literature in the photographic still-life included in the second and main part of The Gothenburg Affair.

Framed by science

A complex scenography built in light, unpainted wood forms the setting of the second part of the work, which has the title We Feel a Desire for Caresses by Men (The Gothenburg Affair) ().Footnote8 The scenography is regularly activated by a live performance. Some of the main elements include a chair with measuring device used by the police for id-photography, a speaker podium with written fragments from the forensic psychiatric protocols, and four small tables displaying an IQ test, a spread of the book Physique and Character by Ernst Kretschmer, a selection of erotic photographs from a collection found in the home of one of the men and which was used to identify several of the suspects, and a vinyl record player.Footnote9 On the wall is mounted a still life photograph of a pile of books – literature mentioned by the accused men and given the role of ‘evidence’ in the investigation. Finally, a red, pulsating light bulb hangs from the ceiling. This is the only element that appears in both the Prologue and the main part of Karlsson Lundgren’s piece. It references the private party and the pulse – 120 bpm – beating in an excited and aroused body.Footnote10 But it can also be associated with the photographic darkroom and thus it points to the multiple – both direct and indirect – roles of photography in The Gothenburg Affair; from the pleasure of looking at erotic imagery in private to the forced portraiture taken by the police for identification.

Figure 5. ‘We Feel a Desire for Caresses by Men (The Gothenburg Affair)’, Conny Karlsson Lundgren, 2021. Photo: Hendrik Zeitler.

In a playful and often enticing, even flirtatious, choreography, a performer links together the ‘clues’ or ‘proofs’ related to the investigation into a new narrative. He connects the various physical elements in the scenography as well as the various voices and discourses – from accused to persecutor, from personal accounts to scientific reports. The performer, who moves around in and activates the scenography, is dressed in a combination of military boxer style underwear, a silky, sleeveless top, silk socks covered by men’s socks, white sneakers and a pearl necklace ().Footnote11 He takes over the space through slow movements and gestures that take the form of poses and occasional dance moves inspired by the erotic photographs and the interrogation accounts. The monologue weaves together fragments of the various interrogations, stating names, occupations, accounts of what happened at the private party and of sexual encounters with other men. In this way, the performer embodies the collective of the men known by their female nicknames like Rosa, Josefin and Olivia – all of who ‘feel a desire for caresses by men’ (as stated in one of the protocols from the investigation). But toward the end of the performance, the performer also reads from the forensic psychiatric protocols and quotes the sentences imposed by the court decision. The performance ends by the performer starting the record player and dancing to a newly produced remix by the duo [inaudible] of a couplet, Jazzgossen (The Jazzboy) from 1922 by the musician and director Karl Gerhard.

Figure 6. ‘We Feel a Desire for Caresses by Men (The Gothenburg Affair)’, Conny Karlsson Lundgren, 2021. Photo: Hendrik Zeitler.

The majority of the historical documentation from the Gothenburg affair that have been saved in public archives are from the authorities – the police and the courts.Footnote12 The National Archives hold the forensic psychiatric reports, including photographs of the men under investigation. In the archive, according to the praxis of the time, the photographs are presented together with descriptions of the ‘suspects’ physical state at the time of being interrogated. Karlsson Lundgren’s works do not include the identificatory photographs, but from the speaker’s podium, the performer cites descriptions of the ‘suspects’ in sentences such as:

He is of standard height, lean and asthenic. He is quite narrow over the shoulders with a marked waist and is strikingly wide over the hips. The position of the legs is male. The distribution of subcutaneous fat shows no female features. The skin is very sweaty. The hair is unusually abundant and of a distinctly masculine type, with compact, cohesive hair from the chest down over the abdomen and genitals. The testicles are smaller than average and of soft, loose texture.

As mentioned, German psychiatrist Ernst Kretschmer’s physiognomic classification system of body types is also represented in The Gothenburg Affair’s scenography. It was highly influential in the young science of criminology as it developed in the interwar years. The comprehensive, influential Handbook of Criminal Technology (Handbok i Kriminalteknik) from 1930, by leading criminologists in Sweden Harry Söderman and Ernst Fontell, includes a methodological survey of criminal types based on Kretschmer’s classification system. The Kretschmerian body types (the asthenic, the athletic, the pyknic and the dysplastic type) were associated with specific personality traits, of which some were prone to psychiatric disturbances and potentially criminal behavior.Footnote14 Asthenic was used to describe a frail, rather weak body type; pycnic a short, rotund type; athletic a muscular physique, frequently characteristic of schizophrenic patients; and the dysplastic types included the so-called ‘eunuchoid’ character, which was characterized by a lack of fully developed reproductive organs and the manifestation of certain female sex characteristics. In general, the physiognomic descriptions of the male subjects’ bodies characterized them as feminine or effeminate. In Karlsson Lundgren’s Gothenburg Affair, from the speaker’s chair, the performer goes on to describe that the suspect’s ‘testicles are smaller than average and of soft, loose texture’. In Södermann and Fontell’s Handbook of Criminal Technology it is explained how the underdeveloped sexual organ ‘results in the body shifting towards the opposite sex, thereby resulting in men of female type and women of male type’ (108). As historian Jens Rydström describes:

non-normative sexual behavior in the 1920s and 1930s was subject to forensic psychiatric diagnosis clearly influenced by phrenology and Kretschmar ideas about the close connection between the shape of the body and the personality. These ideas had a direct impact on the legal measurements and concrete punishment. (Rydström Citation2003, 301ff)

The non-white and the non-heterosexual body

From a larger perspective, Bertillon’s inventions and the criminological methods that they engendered were in turn influenced by what can be described as an archiving paradigm that reached its culmination the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. In the often-quoted article by Allan Sekula, ‘The Body and the Archive’, the cataloguing and categorization of the physical features of criminals and the ideal social citizen is presented as highly significant and indicative aspects of the archival tendencies of this time.Footnote15 These tendencies found particular and extreme expression in the racial sciences, and 1921 Sweden became the first country in the world to open a State Institute for Racial Biology. The physician Herman Lundborg was appointed head of the Institute, which under his leadership collected anthropometric statistics and photographs to map the racial makeup of the Swedish population. The above-mentioned Kretchmer was invited by the Swedish Institute of Race Biology to give public lectures in Sweden, and, judging from the media coverage, they drew a considerable audience. Lundborg had already – notably through photography and with the help of photographers all over the country – begun the systematic, visual mapping of the population’s typologies, a method and a project that was successfully popularized through the 1919 exhibition and the accompanying, almost 300-page widely distributed publication Swedish Folk Types: An Image Gallery Arranged According to Race Biological Principles (Svenska folktyper: bildgalleri, ordnat efter rasbiologiska principer). The photographs originated from numerous sources: professional and amateur photographers contributed images from their archives as well as new portraits roughly following the formats known from anthropology and criminology. Other photographs in the publication came from institutions such as schools, hospitals and the police. One of the last sections in Swedish Folk Types entitled ‘Vagabonds, Gypsies/Travellers, Criminals, and Similar’ (‘Vagabonder, Tattare, kriminella, och dylika’), include a handful of portraits (en face and profile) with uncommon captions inscribing them as mixed genders in various ways, for instance ‘Racially Mixed Woman of Manly Type’ or ‘Male Gypsy of Female Type’ (Lundborg Citation1919, 200–202), which can be traced to the Kretschmerian terminology and body typology. Kretschmer’s ideas were thus disseminated among the wider public and they formed a scientific base for not only race biology and hygiene but also the development of modern criminology in Sweden. In this way, the archived and typological body would be a tool for normative psychosocial categorization, which in turn could justify and intensify the pathologicalisation of both the non-white body and the non-heterosexual body (Rydström Citation2003). Sexual perversions became associated to non-Nordic types, and similar suggestions were regularly repeated at the Swedish Institute for Race Biology, whose perceived threat to the Nordic race by miscegenation and a depraved urban lifestyle also can be linked to sexual deviance. This points to the links between racial biology and criminology, which during the 1920s was influenced by ideas about the biologically abnormal criminal. Kretschmer was also a close supporter and collaborator with the Nazis and thus one of many links between them and Lundborg.

The performer in the second part of Karlsson Lundgren’s Gothenburg Affair brings life to the supposedly factual methods used and ‘evidence’ found in the investigation by physically and affectively engaging with it. Rather than detached technical or scientific tools, he reveals them to be the product of a particular historical and ideological context, which resonate on a different affective register depending on how they are engaged with. In the same way that the photographs in the Prologue dismantle the constructed divide between the haptic and the optic, the performance brings an embodied understanding to the categorizations, the ideology, and the misconceptions that underpin the criminology of the time and the ‘science’ to which it relates.

Querying and queering archives

Critically engaging with archives has been a significant trend in contemporary art practices over the last couple of decades.Footnote16 Karlsson Lundgren’s work can be placed with this wider trend, but also within narrower contexts, such as that of artists engaging with practices of ‘queering the archive’ through different strategies – or of artists re-working difficult shared histories involving oppressive and/or violent components. In terms of the latter context, The Gothenburg Affair was created to be a part of a research project that looks back to the history of the mid-war period in Sweden and Europe through works of contemporary artists. To mention a few examples, artists that share this focus include Katarina Pirak-Sikku’s long engagement with the archive of racial biology in Sweden from a Sami perspective, the work of Hanni Kamaly on changing attitudes and laws around migration during the mid-war period and its relation to the general history of racism, and Kristina Müntzing’s engagement with the history of the textile industry and women’s labour.Footnote17 In a recent article, Erika Larsson describes Pirak Sikku’s profound emotional and physical working through of the artist’s own experience of the archive of racial biology. Larsson suggests how Pirak Sikku’s engagement opens perspectives from which care and inquisitiveness can triumph over historical injustices (Larsson Citation2020). In all of the examples mentioned, archives provide the source of the artist’s engagements and in many of them, the works bring previously ignored stories to light and rework oppressive dynamics through different strategies.

Another strategy, which is at the core of the artistic methodology of not only The Gothenburg Affair but also several of Karlsson Lundgren’s earlier works, is the restaging and reperformance of historical still photographs as a means to queer the archive. An early example is the video piece I Am Other (Candy & Me) (2007–2008) made in collaboration with writer and activist Andy Candy and based on the 1974 iconic photograph of Candy Darling by Peter Hujar entitled Candy on her Deathbed (). Hujar’s portrait can be said to fix the figure of the transwoman as a lonely, victimized and sad figure, but in Karlsson Lundgren and Andy Candy’s video, Andy Candy not only creates an affective link with Candy Darling across time, but also transforms her into an empowered position in the present. As art historian Mathias Danbolt describes the work:

Claiming that the only way of dismantling an image is to first ‘recognize that it exists’, the video shows how confronting the archive can be a strategy of resistance: after Andy Candy has pointed out that there is nothing liberating in being an object, she leaves the prescribed death bed and walks out of the image – out of the archive. (Danbolt Citation2009, 40)

Intimacy and erotics as strategies of resistance

In We Feel a Desire for Caresses by Men (The Gothenburg Affair), the live performer challenges how bodies and sexualities were seen, shaped, and constructed – and how this related to concrete criminological and ‘scientific’ practices – through interacting with archival text and image through an affective and ephemeral performance in the present. The performer unites and embodies both the elements of homophobic violence and surveillance – as well as the friendship, pleasure, and affection of the queer community of the time. By moving and posing in between the authoritarian architecture of the police and the court in his queer outfit, and by quoting the forensic reports and sentencing in his own soft voice, the performer reclaims the narrative of the Gothenburg Affair in what can be interpretated as a gender-queer voice – but also eroticizes it. He moves around slowly and regularly poses, thus creating a series of tableaux, and the audience can image him staging and reperforming both the erotic photographs confiscated by the police as well at the creation of a police id-photo. At one point, for instance, he is reciting a witness statement about possessing indecent photographs while sitting in the police photo studio chair, which appears uncomfortable, of pure wood and with dimensions a little too small (). This prompts the audience to consider what photographic practices are indecent here, as the police id-photos can be seen as an involuntary and even violent genre. Significantly, the scenography includes anonymized versions of the supposedly indecent photographs confiscated by the police, but not the police id-photos. In this way, it is the latter that are treated as potential violations in relation to which care should be taken in order for this violence not to be repeated in the exhibition space, while the former become rather a source of empowerment. The illegalized photographs manifest something pleasurable and exclusive for the group of friends. It is also while sitting in the chair of the police photo studio that the performer recites one of the strongest statements in the piece: ‘I am a Roofer. I am a Pastry Chef. I am a Waiter. I am a Student. I am a Bundle Maker. I am a Corpse Bearer. I am a Kitchen Boy. I am a Journalist. I am a Mess Boy. (…) I am a young man – and I feel desire for caresses by men’. This performative proclamation, in which the individual prosecuted become one, becomes an act of empowerment for the group as a whole.

Figure 8. ‘We Feel a Desire for Caresses by Men (The Gothenburg Affair)’, Conny Karlsson Lundgren, 2021. Photo: Hendrik Zeitler.

This artistic strategy opens up for a nuanced understanding of exposure and surveillance as not only a top-down, involuntary abuse of power, but as something potentially pleasurable in a counter- or inter-surveillance act. John McGrath discusses this potential in relation to unintentional outings in artistic and activist work and popular culture by John Greyson and George Michael, where surveillance footage of men engaging in illegalized gay sex is turned into aesthetic and erotic pleasure by the surveilled and accused. McGrath notes how counter-surveillance ‘becomes not only about reversing the gaze but about opening a space for all sorts of reversals in relation to how the gaze and its imagery may be experienced’ (Citation2004, 201). A similar multifaceted space of gazes and their potentialities in both past and present is evoked in Karlsson Lundgren’s The Gothenburg Affair.

Another work by Karlsson Lundgren, a public monument not yet actualized but which is planned to be erected in 2023, references spaces in the local city of Gothenburg where gatherings of queer communities were held at different times in history. The monument Gläntan (The Glade) consists of three layers, which allude to both public and private spaces in the local area of Gothenburg, connected to this history (). The bottom layer is ‘The Dance Floor’ and references the floor plan of a night club, ‘Touch’, which was one of the first public spaces for gathering of gay communities in the 1980s. The second level, ‘The Kitchen’, references the space of a lesbian and queer feminist collective active from the 1970s until 2017, in which political meetings, social gatherings and other events would be held. The top space, ‘The Bedroom’, is the most private of the three spaces and refers to the home of one of the group of men targeted during the Gothenburg Affair. In the documentation he is referred to as ‘Josefin’. As public gathering for gay communities was criminalized until 1944, the private home of ‘Josefin’ was one of the spaces in which the group of friends would gather to meet, listen to music, dance, and share experiences and desires. The home of ‘Josefin’ no longer exists, but the top level of the monument is taken from the bedroom of the floor plan of the now demolished apartment. On top of the uppermost level, there are three pillows made of marble. The pillows have dents in them as if they were recently slept on and connected to coils that keep them heated to body temperature. This figurative aspect of the monument can be seen as a memorial for everyone who has been affected by this history – such as the people that once populated the spaces referenced in the three levels of the monument. In relation to the media exposure and criminological investigation of the Gothenburg Affair, they become a reminder of the private lives and intimate desires that are put to public display and turned into politics throughout different times in history.

Figure 9. ‘Gläntan/The Glade’, Conny Karlsson Lundgren, 2022–2023. Visualization: Jonas Carlsson/New Order Arkitektur.

In The Gothenburg Affair, the performer embodies the pain and shame of being interrogated, measured and documented, such as when the performer places himself in the chair with measuring device (). At the same time, as touched upon above, the performance brings to life a parallel historical situation, which includes the joy, pride, and strength of an early resistance in the shape of the collective and in how the group of friends would defend the private sphere that is intruded upon. Through the details offered with the purpose to penalize, we understand how intricate the relationships of the group of friends were, and how thought-out the gatherings were. In the archival material it is described how the group would refer to the community in terms of a ‘spiritual kinship’.Footnote18 While the language and the methods of the investigation present these details as evidence of criminality and pathology, in the performance they come across rather as expressions of a growing sense of self-assurance. The song that the performer puts on and dances to at the end of the performance – Jazzgossen (The Jazzboy) – is an early expression of a subculture of fluid gender roles. Originally written 1922, when the word ‘jazz’ was a modern addition to the Swedish vocabulary, the text partly made fun of effeminate young flaneurs. The Gothenburg Affair lets us imagine the song often being played during the gatherings of the group of gay friends and thus reappropriated.

Furthermore, the sensuality and erotic aspects of the archival material and the narratives that it contains are conspicuously brought into focus through the (archival and newly taken) photographs and through different aspects of the performance. In the archival material, sensual and erotic details are included as evidence of criminality and perversion (although in Lundén’s article this is coupled with fascination). Through the strategies discussed above (using the photographic technology to enhance the sensual aspects of the materials and the manuscript, gestures, movements, voice, dancing and music of the performance) the villainizing documentation of the investigation is inverted in ways that bring to mind the feminist writer Audre Lorde’s reflections on the power of eroticism. Lorde, identifying as a ‘Black lesbian feminist’, directs her writing to empowering female eroticism of all forms. Nevertheless, the power that she describes resonates in many ways with the dynamics at work in Karlsson Lundgren’s works. Lorde describes how ‘we’ (in her text meaning women, but used here to refer to repressed sexuality in a wider sense) ‘have been raised to fear the yes within ourselves, our deepest cravings’ (Lorde Citation1978, 90). She describes how it is the fear of our desires that keeps them ‘suspect and indiscriminately powerful’ as it is the process of suppressing one’s truth that gives it strength (Ibid.). Once recognized however, the desires lose any destructive power, and the possibility opens up for transformation. When the energies of the erotic are released from the constrains that society has placed them within, they become rather a source of empowering energy, which both affects the experience of being alive in a basic existential (and spiritual) sense – and becomes a potential source for political transformation. As Lorde shows, the dichotomy of the spiritual and the political (as well as the creative, and everyday activities) is itself false, and a consequence of ‘incomplete attention to our erotic knowledge’ (Lorde Citation1978, 90). She explains how a bridge between them can be formed by the erotic and the sensual, or by those ‘physical, emotional, and psychic expressions of what is deepest and strongest and richest within each of us, being shared: the passions of love, in its deepest meanings’ (Ibid.). In the archival material that Karlsson Lundgren works with, erotic and sensual details are treated with either a combination of disgust and fascination, or as dry evidence of criminal behavior. By not only including these details in the different aspects of the work, but also and in different ways intensifying, exaggerating or elevating them, he pokes fun at the judgmental attitude of the original material. At the same time, he inverts the villainizing ways in which they are presented in the archive, and which in the words of Lorde keeps them suspect and indiscriminately powerful, and instead releases them as a power for transformation.

Conclusion

The investigation of the Gothenburg Affair was conducted during a time in which the science of criminology expanded to envelop new technologies and methods of identification and categorization. As we have described, new uses of photography, the portrait parlé, and the Kretschmerian body types were implemented to identify criminal individuals and behaviors and place them within a particular category of criminality or pathology. At the same time, these methods and new uses of technology were in turn influenced by a wider archival paradigm, which included the pseudo-science of racial biology. In the overlap of mid-war criminology and racial biology, homosexual behavior and ‘lower races’ were both considered as dangers to society at large – and needing to be controlled through different measures.

Karlsson Lundgren’s The Gothenburg Affair includes several references to the methods and belief systems of mid-war criminology, including the aesthetics and form of the artist’s own ‘evidentiary’ photographs in the Prologue, and the forensic psychiatric protocols, IQ test, and spread of the book Physique and Character by Kretchmer in the scenography of the second part. At the same time, the work also unfolds a counter history of resistance in the shape of the collective, which can be found between the lines of the article by Lundén and in certain details in the records of the investigation. What’s more, by conspicuously bringing out the sensual and sexual details of the archival material – through the photographs included in both parts of the piece and in the body language and manuscript of the performance – Karlsson Lundgren inverts the denigrating and stigmatizing ways in which they are used in the different materials. He flips it into a source of transformative energy and, in this way, intervenes in history to continue the resistance found between the lines of the archival material itself.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Erika Larsson

Erika Larsson is a lecturer and researcher in Visual Culture at Lund University with an interest in affective, embodied and non-representational perspectives on photography. She has previously had a postdoc position at HDK-Valand Academy, Gothenburg University, together with the Hasselblad Foundation, researching contemporary artists' engagements during the interwar period.

Louise Wolthers

Louise Wolthers, PhD in art history, is the Head of Research and Curator at The Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg. She leads and participates in collaborative research projects resulting in publications, symposia and exhibitions, and publishes widely on photography, contemporary art and visual culture in books and journals.

Notes

1 Physiognomy involves the notion that it is possible to determine personality (and moral) from outer appearance alone, while phrenology focused specifically on the relationship between a person’s character and the morphology of their skull. These methodologies were core in various colonialist and eugenic ‘sciences’ of the late eighteenth and nineteenth century.

2 Lundén was a musician and journalist and was the chief editor of the culture magazine VIDI in the 1920s and 30s. While he was in charge, the magazine had a strong conservative, anti-Semitic and homophobic focus. During this period, he also founded the Swedish Anti-Semitic Association.

3 Barthold Lundén ‘En homosexuell pesthärd i Partille’, VIDI, Gothenburg, 1924.

4 ‘Där satt två kind vid kind och med armarna ömt slingrade kring lilla midjan och Där lutade en annan sitt huvud så smeksamt mot sin grannes bröst och Där satt ännu ett par så tätt, tätt intill varandra’ (authors' translation).

5 For photo historical discussions of the general practices of crime photography, see Regener, Sekula and Tagg. For analysis of crime scene photography in the interwar period, see Lebart and Wolthers.

6 ‘inte vågar husera hur fräckt som helst, eller demonstrera sina vidriga drifter allts för ostentativt och öppet’ (authors' translation).

7 See Halperin for further discussions on limp wrists and other effeminizing gestures in the history and practices of homosexuality.

8 The form of the wood structures is taken from the artist Josef Alber’s Nesting Table, Bahaus 1926, and can be seen as a comment to the time of transformation that the archive belongs to.

9 The spread from Kretschmer’s book is included in two versions, one from the first edition in 1926 and the other from 1932. In the second version, the naked person in the image is made anonymous. The performer moves a lens between the two version, also (as with the forms of the table) as a reflection on the changing attitudes of the time.

10 Significantly, in the article by Lundén, the light emanating from the party as they approach is also described as ‘a pink-colored warm light, the intoxicating Light of Love’.

11 The double layer of the socks can be seen as a reference to the habit of covering clothing that was considered feminine would be hidden underneath masculine clothing.

12 This reflects how historians of queer pasts are generally challenged with the lack of conventional evidence of queer lives, which José Esteban Muñoz notably wrote about. ‘Queerness has an especially vexed relationship to evidence. Historically, evidence of queerness has been used to penalise and discipline queer desires, connections, and acts’ (Muñoz Citation2009, 65). For a historical context of other uses of court records as queer history writing, see Houlbrook (Citation2005).

13 Allan Sekula describes the Portrait Parlé as ‘a strict denotative signalectic vocabulary (…) aimed for the precise and unambiguous translation of appearance into words’ (Sekula Citation1984, 360).

14 While contemporary textbooks within criminology distance themselves from the kind of biological determinism evident at this time, the idea that criminal behavior is rooted in biology still remains in a different form. In Vold’s Theoretical Criminology, which was first published in 1958, but now on its sixth edition and still considered the standard text in criminological theory, it is described how modern biological theories in criminology argues that ‘certain biological characteristics increase the probability that individuals will engage in behaviors, such as violent or antisocial behaviors, that are legally defined as criminal or delinquent’. Rather than body type and visual characteristics, as was the focus of the early twentieth century, contemporary criminology tends to focus on factors such as genetics, neurotransmitters, hormones and differences in the nervous system (Bernard, Jeffrey, and Gerould Citation2010).

15 Sekula talks of a very explicit deterrent or repressive logic behind the photographs used for criminal identification, as they are ‘designed quite literally to facilitate the arrest of their referent’. In other words, the individual criminal body is captured by the camera and placed not only within a physical archive, or filing cabinet, but also within a growing generalised socially and morally hierarchical shadow archive ‘that encompasses an entire social terrain while positioning individuals within that terrain’ (Sekula Citation1986).

16 In terms of institutional critique, perhaps the most influential work is found in the practices of Marcel Broodthaers and Fred Wilson.

17 Works by Katarina Pirak Sikku, Conny Karlsson Lundgren, Hanni Kamaly, and Kristina Müntzing were shown together in the exhibition With New Eyes – The Interwar Period seen though a Lens at Göteborgs Konsthall in 2021–2022. The images of the Gothenburg Affair seen in this article were taken during this exhibition.

18 This is how the community of friends is described by Backfischen in a police interrogation. Förhör med [XXXX] ‘Backfischen’. In Göteborgs rådhusrätts arkiv. Rådhusrättens avdelning, Serie 5AII, vol. 113, § 91.

References

- Bernard, Thomas J., B. Snipes Jeffrey, and Alexander L. Gerould. 2010. Vold’s Theoretical Criminology. 6th ed. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.

- Brown, Elspeth H., and Thy Pru. 2014. “Introduction.” In Feeling Photography, edited by Elspeth H. Brown, and Thy Pru. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Danbolt, Mathias. 2009. “Touching History: Archival Relations in Queer Art and Theory.” In Lost and Found: Queerying the Archive, edited by Jane Rowley and Louise Wolthers. Nikolaj, Copenhagen Contemporary Art Center and Bildmuseet Umeå University.

- Halperin, David. 2012. How to be Gay. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

- Houlbrook, Matt. 2005. Queer London. Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1019–1957. The University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, Amelia. 2021. In Between Subjects: A Critical Genealogy of Queer Performance. London & New York: Routledge.

- Larsson, Erika. 2020. “Feeling the Past: An Emotional Reflection on an Archive.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 12 (1).

- Lebart, Luce. 2015. “Rodolphe R., Reiss: Traces, Marks, Prints: Revealing Details Invisible to the Naked Eye.” In Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence, edited by D. Dufour, and Xavier Barral. Paris: Le Bal.

- Lorde. 1978. Audre Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power. Brooklyn, NY: Out & Out Books.

- Lundborg, Herman. 1919. Svenska Folktyper: Bildgalleri Ordnat Efter Rasbiologiska Principer och Försett med en Orienterande översikt. Stockholm: A.-B. Hasse W. Tullbergs Förlag.

- McGrath, John. 2004. Loving Big Brother. Performance, Privacy and Surveillance Space. Routledge.

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 1996. “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts.” Women &. Performance, Queer Acts 8 (2/16).

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 2009. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York University Press.

- Olin, Margaret Rose. 2012. Touching Photographs. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

- Regener, Susanne. 1999. Fotografische Erfassung. Zur Geschichte Medialer Konstruktionen des Kriminellen. München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

- Rydström, Jens. 2003. Sinners and Citizens: Bestiality and Homosexuality in Sweden 1880–1950. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Schneider, Rebecca. 2011. Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment. London, New York: Routledge.

- Seitler, Dana. 2014. “Making Sexuality Sensible, Tammy Rae Carland’s and Catherine Opie’s Queer Aesthetic Forms.” In Feeling Photography, edited by Elspeth H. Brown, and Thy Pru. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Sekula. 1984. Allan Photography Against the Grain; Essays and Photo Works. Halifax: Press of the Novia Scotia College of Art and Design.

- Sekula, Allan. 1986. “The Body and the Archive.” October 39.

- Söderman, Harry, and Ernst Fontell. 1930. Handbok i Kriminalteknik. Stockholm: Wahlstörm & Widstrand.

- Tagg, John. 2009. The Disciplinary Frame. Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Wolthers, Louise. 2021. “Connecting the Dots: Photography, Criminology and Interwar Sweden.” In Thresholds – Interwar Lens Media Cultures 1919–1939, edited by Mats Jönsson, Louise Wolthers, and Niclas Östlind, 249–269. Berlin: Walther König.