ABSTRACT

This article presents a concept for an imagined exhibition relating to the work of Su Shi (1037–1101), also known as Su Dongpo. A renowned poet and calligrapher from China's Song Dynasty, Su Shi stands out as one of the pivotal figures in traditional Chinese literature; credited with penning many of China's iconic poems that remain part of the educational curriculum in China today. The proposed project is situated within the historical sites of Hainan, an island where Su Shi was exiled near the end of his life. Taking a contemporary approach to heritage, the exhibition concept draws upon recent developments in artificial intelligence large language models, with the aim of enabling visitors to generate and explore ‘lost’ poems of Su Shi.

Su Shi, also known as Su Dongpo, was a famous Chinese writer, poet, painter, calligrapher, gastronome and statesman of the Song Dynasty. He is regarded as one of the most accomplished figures in classical Chinese literature, having produced some of the most well-known Chinese poems, which to this day are studied in schools in China.

The following notes gesture towards an exhibition: Dongpo Dream Machine. The initial inspiration came from preliminary discussions with colleagues at Hainan University engaged in heritage projects relating to Su Shi. The poet was famously exiled to Hainan in the latter years of his life. His time on the island was highly productive, which to this day is marked by several key heritage sites. The island presents numerous opportunities for site-specific installations, whereby visitors can soak up the historical atmosphere of Si Shi’s time, yet equally engage in contemporary techniques to artificially recover the 'lost' art of Su Shi’s writing and painting.

In the Dongpo Historical Culture and Art Museum in Hainan, an exhibit uses the metaphor of the strategy game Go to dramatise the conspiracy leading to Su Shi’s exile to Hainan.

As Edgar Allan Poe (Citation2003, 141–142) writes, at the start of ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue': ‘to calculate is not in itself to analyze. A chess-player, for example, does the one without effort at the other […] in nine cases out of ten it is the more concentrative rather than the more acute player who conquers’. Whereas, in draughts (which is still less complex than Go), ‘the moves are unique and have but little variation, the probabilities of inadvertence are diminished … what advantages are obtained by either party are obtained by superior acumen’. Poe alerts us to ideas of complexity, idiosyncrasies and probabilities. The calculation of the latter is key to recent developments in AI generative language and image models, which – capable now in making unique new ‘moves’ – demonstrate impressive results in generating new images and texts, including original poems. Assuming Su Shi’s writings are deeply buried somewhere in the billions of parameters of training data of Large Language Models, how might we begin to imagine new poems after Su Shi?

Exhibit at Dongpo Historical Culture and Art Museum, Hainan (Courtesy of the museum. Photo: Sunil Manghani).

The Dongpo Academy, located in Danzhou, Hainan, retains its ancient and classical charm, preserving inscriptions and artifacts from ancient times, exuding an atmosphere of scholarship. Su Shi opened a school on the site to teach poetry and spread Central Plains culture. Today, visitors can view many of his manuscripts in the main hall and adjoining rooms. To reach the Zaijiutang (载酒堂 Zài jiŭ táng), the main building where Su Shi lived and gave lectures, it is necessary to cross a long bridge over a lake covered in lotus flowers.

A plaque gives the name ‘Dreaming Lake’ (originally ‘Dongpo Lake’), and explains:

In his spare time, [Su Shi] often walked to the pond to watch wild flowers, water and birds, recite poems and appreciate the moon, and communicate with farmers in the fields. As time passed, he planted his favorite lotus in the pond by himself. When the lotus was in full bloom, Su Dongpo would go to the pond to enjoy the flowers and chant poems. He wrote down the beautiful poem of ‘Small lotus in an elegant posture, with unchanged distinctive fragrance and colour’ to express his mood.

‘Dreaming Lake’, Dongpo Academy, Hainan (photo: Wang Jingyin).

小荷才露尖尖角, 早有蜻蜓立上头。

[The little lotus has just revealed its sharp corners, and a dragonfly has already stood on it].

![‘Dreaming Lake’, Dongpo Academy, Hainan (photo: Wang Jingyin).小荷才露尖尖角, 早有蜻蜓立上头。[The little lotus has just revealed its sharp corners, and a dragonfly has already stood on it].](/cms/asset/8e8f4c47-5331-4e62-a488-109e6bfb856b/rjvp_a_2273060_f0002_oc.jpg)

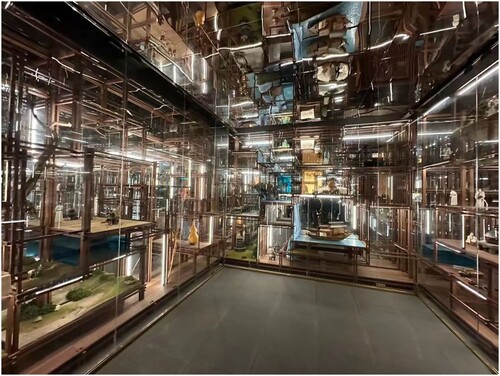

Back at the Dongpo Historical Culture and Art Museum, you can walk along a corridor with scenes of a ‘day in the life’ of Su Shi, ending with him asleep in his chair. The visitor then steps into the next room, a mirrored room, full of vignettes from Su Shi’s life, as if stepping into Su Shi’s own mind or dreamscape.

Despite the reverence afforded Su Shi’s life and works, and despite being considered one of the foremost important literary figures for Chinese culture, it is surprising that the surviving corpus of works is relatively small. He spent his days imbued in scholarly and educational pursuits, yet might we expect to find more evidence of his writings?

We can easily begin to imagine Su Shi out alone on Dreaming Lake, under the moonlight, extemporising many more poems than have ever been written down. Today, through the many hints and suggestions of huge data archives, might we rescue the odd soundings and phrases of these ephemeral delights?

‘Dream Room’ at Dongpo Historical Culture and Art Museum, Hainan (Courtesy of the museum. Photo: Wang Jingyin). Details of cabinet vignettes are shown on the next two pages (Courtesy of the museum. Photos: Ed D’Souza).

In Chinese calligraphy and painting, each stroke is filled with meaning, not just in the literal sense but also in the way it captures the artist’s intent and emotion at the very moment of a mark’s creation. This ephemeral yet lasting quality mirrors the transient yet cyclic nature of life itself. When Su Shi writes a poem, every character is not just a semantic unit but a world of its own – a moment in time, an emotion, a landscape or a philosophical musing.

It is apt to draw a parallel between this act of making and looking into a mirror. Just as our reflection seems the same, it equally changes with each passing moment. So, Su Shi’s poems can be read multiple times, with each reading offering a slightly different insight or emotion. Every word, character, or brushstroke offers both the constancy of form and the variability of interpretation.

Cabinet vignette from ‘Dream Room’ at Dongpo Historical Culture and Art Museum, Hainan (Courtesy of the museum. Photo: Sunil Manghani).

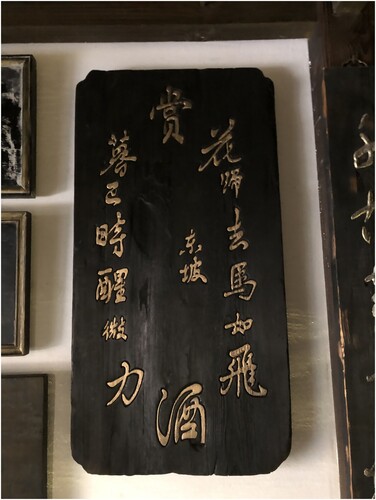

At the entrance of the Dongpo Historical Culture and Art Museum is a poetic note in admiration of Su Shi, composed by his brother. Written in ancient Chinese, it is typical of the period, presenting a circular series of six lines, with the meaning of characters each overlapping from the previous line. It takes a curious mind to unpick and admire the message, as if a word puzzle.

In contemporary Chinese art, the idea of cyclical thinking may have diminished somewhat. Nevertheless, the timeline in Su Shi’s poems often resembles a circle. Each word stands on its own, but it is also a character, a line, a brush of ink, a moment just beginning. Again, reminiscent of looking into a mirror: the reflection is real, but with each glance, with each moment, there is a subtle difference; another reading.

Poetic note, carved on wood. Entrance of Dongpo Historical Culture and Art Museum (Courtesy of the museum. Photo: Sunil Manghani).

We might consider the clever embedding and nesting of ancient ‘codes’ emblematic of the massively complex machine patterns and deep learning that today enables vector embeddings and the mathematical representation of words and phrases in a high-dimensional space. In this light, AI large language models might be thought of a massive collection of poetic puzzles, spanning across a complex array of virtual ‘space’, which only a machine can read – but which can formulate (and predicate) perfectly legible texts for the human reader.

We hear of the problem of AI hallucinations. A term used negatively to describe how language models can generate highly plausible and fluent texts, but which are factually and even logically incorrect. But is that not to say AI can dream too? Like Su Shi, rocking in a boat on the Dreaming Lake, parsing through all manner of visual and verbal possibilities from his day, might AI too offer glimpses of all kinds in its massive collection of texts and pictures? Only, in this case, given that a day’s worth of information for AI would seem equivalent only to a second’s worth of human time, the artificial dream machine can happily muse upon a century’s worth of comings and goings.

AI imaginings of a digital, immersive exhibition upon Dreaming Lake, based on DALL-E 2 prompt: ‘ … presenting poetry on Su Dongpo dream lake, filled with lotus flowers’.

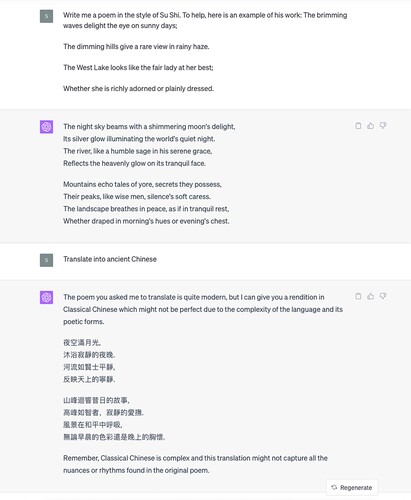

If you were to ask Su Shi, perhaps he would have responded … Such a figure of speech is not wholly uncommon, as interlocutors muse upon what might have been, or how an ancient mind might respond to a contemporary circumstance. Inevitably, it is a figure of speech that marks an impossibility. However, when we suggest asking what AI might say, then it is not rhetorical at all. Like in a dream, even the impossible becomes plausible. In dreams, the boundaries of reality, time, and possibility are often blurred or non-existent. In a dream, you can converse with Su Shi, fly through otherworldly landscapes. So what if, today, we suggest interactions with AI give us a tangible tool to recover or at least hint of our otherwise impossible ponderings?

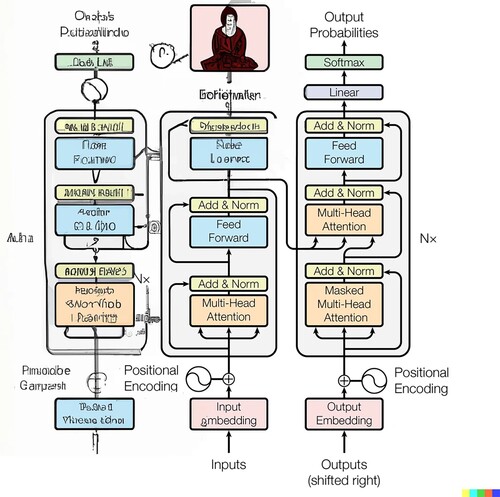

In 2017, a group of researchers at Google presented the new ‘transformer’ model for AI language models (Vaswani et al. Citation2017). It proved a breakthrough, leading to a great deal of media attention and widespread public use of models such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Meta’s LLAMA, Google’s BARD, and Anthropic’s CLAUDE. The Transformer model is described as an ‘attention-based’ model, which beyond encoder–decoder models, introduced a new layer of ‘self-attention’. The Transformer model effectively looks back at its own generation of text prior to presenting anything to the user. It can work more quickly and in more complex ways across an array of data.

When considering the duration and sound of Su Shi’s poems, it is noteworthy that Chinese poetry from the Song Dynasty is often succinct. Yet, when read aloud, Su Shi’s poems feel expansive. We might say, they encode within themselves a form of ‘self-attention’. It would be intriguing to ask various individuals to recite poems collectively. The ‘voicing’ of Su Shi’s poems is not something we can necessarily emulate. Yet, with new advances, perhaps we are closer to finding out what it might have been like to hear Su Shi read his own poems aloud; not least, perhaps, when inebriated, out alone on the lapping waters of Dreaming Lake. Such readings would likely alter the meanings of the characters, since Chinese characters often carry multiple meanings, yet seamlessly fit into different contexts, preserving the integrity of a sentence.

Dongpo Dream Machine, as envisaged by DALL-E 2 as an extension to ‘The Transformer – model Architecture’ (Vaswani et al. Citation2017).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Qiuyu Jin

Qiuyu Jin is an assistant professor at Nihon University College of Art. She holds a BA from Nihon University College of Art and an MA from the Department of Arts Studies and Curatorial Practices at the Graduate School of Global Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts, where she is currently pursuing her doctoral research. In 2016, she was an exchange student at JGU Kunsthochschule Mainz and she was also part of the team of Echigo Tsumari Triennale, Tokyo Biennial and Oku-noto Triennale. She curated the exhibition Not in this Image (Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts Taipei, 2020), Sense Island 2022 (Sawushima, Yokosuka). She is also the director of the experimental image forum non-syntax.

Sunil Manghani

Sunil Manghani is Professor of Theory, Practice & Critique at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton (UK). He is Co-Editor of Journal of Visual Art Practice, and Managing Editor of Theory, Culture & Society. His books include Image Studies (2013), Zero Degree Seeing (2019), India’s Biennale Effect (2016) and Farewell to Visual Studies (2015). He curated Barthes/Burgin at the John Hansard Gallery (2016), along with Building an Art Biennale (2018) and Itinerant Objects (2019) at Tate Exchange, Tate Modern.

References

- Poe, Edgar Allan. 2003. The Fall of the House of Usher and Other Writings. London: Penguin.

- Vaswani, Ashish, et al. 2017. “Attention Is All You Need.” 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017). Available: arXiv:1706.03762v7 (v.7, 2023): https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762.

![‘Dreaming Lake’ [Detail], Dongpo Academy, Hainan (Photo: Sunil Manghani).](/cms/asset/9a694add-d2f9-4444-9a05-b2748a2ec4e8/rjvp_a_2273060_f0011_oc.jpg)