ABSTRACT

This article offers an introduction to ‘After Su Shi’, a special issue of Journal of Visual Art Practice, which focuses on the art practice of China’s revered poet, calligrapher and stateman, Su Shi (1037–1101). The article situates the work of Su Shi specifically within the context of Hainan, the southern island of China where Su Shi was exiled near the end of his life. Some of his most famous poetry was written during this period and subsequently his identification with Hainan has long endured. Key heritage sites are referenced in this article, and, combined with an overview of the collected papers of the special issue as well as Hainan’s recent new status as free port, this introduction sets out both a historical and contemporary view of Su Shi. It elucidates his far-reaching influence but also contemporary ‘currency’, suggesting of what might come after Su Shi, both in this image, but also akin to his free-spirited belief in the arts.

This article offers an introduction to ‘After Su Shi’, a special issue of Journal of Visual Art Practice. It brings together six contributions from academics and artists to offer contemporary explorations and reflections of the art practice of China’s revered poet, calligrapher and stateman, Su Shi (1037–1101).

When considering the vast expanse of art and culture, the term ‘after’ carries layered connotations, a nuanced bridge linking epochs, traditions and evolving ideologies. Historically, in the realm of visual art, ‘after’ serves to denote works created in the likeness or influence of a preceding master, pointing towards a lineage of craftsmanship and a dialogue between originality and homage. This special issue delves into this continuum, exploring not only Su Shi's indelible mark on Chinese calligraphy and poetry but also discerning his echoes in the cadences of contemporary art practice. In a synchronicity of temporal and urban development, Hainan’s recent metamorphosis into a bustling free trade port offers a fresh canvas, juxtaposing the island’s rich heritage with burgeoning tourism and economic prospects. Thus, ‘after’ becomes more than a mere chronological indicator; it becomes a compass pointing to both legacy and foresight, and to the interplay of tradition and modernity.

Introducing Su Shi

Su Shi was born in 1037 and died in 1101. He was known by his courtesy name Zizhan and art name Dongpo, as well as collectively termed San Su alongside his father, Su Xun and his younger brother, Su Zhe. In 1057, during the reign of Emperor Shenzong, Su Shi achieved the prestigious Jinshi degree, a stepping stone to high governmental roles. However, after criticising Wang Anshi's reforms, Su Shi was appointed magistrate of Hangzhou, and later held positions in Mi, Xu and Hu prefectures.

By 1079, his poetry had led to imprisonment, after which he was demoted to the deputy envoy of Tuanlian in Huangzhou. Yet, he later ascended to roles in the Hanlin Academy and even became the Minister of Rituals and the Master of Duanming Hall. In 1097, he faced exile once more (but later pardoned) after he was found guilty of charges related to criticisms of the government. He was sent to Danzhou on the island of Hainan, where he remained until shortly before his death. He spent only three years at Hainan, yet it proved a significant influence. As Lin (Citation2009, 462) remarks: ‘This was real exile, imposing bodily hardships on the old man’, and quoting Su Shi: ‘I cannot enumerate all the things that we have to do without. In short, we lack almost everything. There is only one consolation, and that is, we also lack malaria here’. Yet, despite the hardships, some of Su Shi’s most famous poetry was written during this period and subsequently his identification with Hainan has long endured.

Golden statue of Su Shi at Dongpo Academy, Hainan.

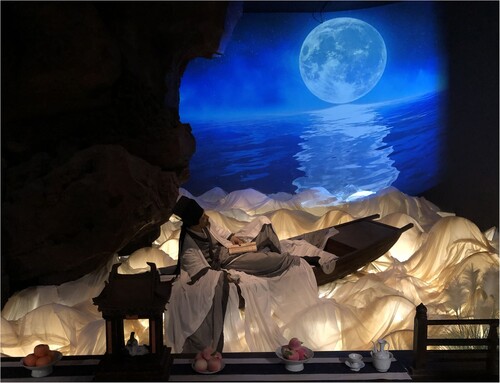

Exhibit at Dongpo Historical Culture and Art Museum, depicting Su Shi, who would regularly sit in a boat under the moonlight in the middle of the ‘dreaming lake’ filled with lotus flowers at his Academy.

During his crossing to reach the island of Hainan, the tumultuous waves of the South China Sea might have mirrored Su Shi’s own upheavals. Yet, he found solace, inspiration and profound introspection on the island. Despite facing hardships during his exile, Su Shi aided the locals by curing illnesses, promoting farming, establishing schools and imparting knowledge about the Tao, exemplifying the spirit of Chinese literati and bureaucrats. Indeed, many people travelled hundreds of miles to meet with Su Shi. Subsequently, he has come to be considered a notable scholar and a pioneer of Danzhou culture.

While Su Shi is known for his many roles as a poet, statesman, painter and calligrapher, he was also a man who appreciated life’s everyday pleasures. As a gastronome, Su Shi loved to experiment with recipes and is famously associated with Dongpo Pork, a braised pork belly dish, with the meat's layers of fat giving it a melt-in-the-mouth texture. The dish is said to reflect his love for hearty, comforting food that brings joy to the senses. He was also known to enjoy wine and was often described as a happy drunk. He wrote: ‘I never pass a day without visitors, and never have visitors without wine’ (Lin Citation2009, 432). This fondness for wine sometimes made its way into his poetry, adding a lively, human touch to his scholarly work. Su Shi’s appreciation for earthly delights shows a man who embraced life in all its dimensions, finding beauty and joy not only in intellectual and artistic pursuits but also in the simple, sensory pleasures of daily life.

Su Shi is credited with the formation of literati painting or wenrenhua (文人畫), which emphasised personal erudition and expression over literal representation or codified motifs and beauty.Footnote1 Contemporary artist Zhang Qiang demonstrates, with a contribution to this special issue, the importance of literati painting to ‘visual history’, which remains an important influence on art practices to this day.

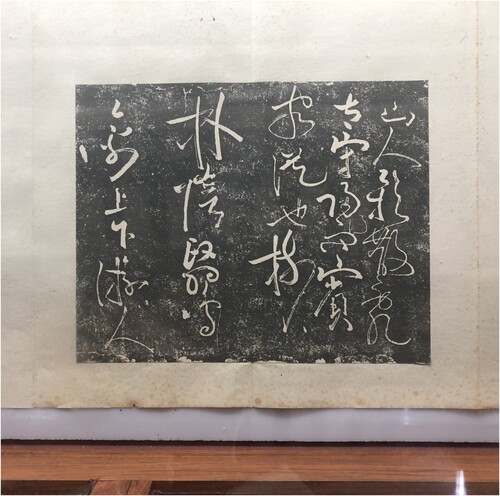

Su Shi’s own, much-revered calligraphy embodies the Chinese cultural ideal of ‘sublimity’, rooted in yi (intention/will). The challenge in Su Shi’s art is not depicting form but capturing and conveying yi, revealing universal truths. Yi is said to arise from the dynamics of qi (vital energy) and is intertwined with the Tao, cherished by Chinese literati. The notion of yi is associated with Su Shi’s calligraphy, which demonstrates a combined sense of form and spontaneity and artistic expression. He believed understanding calligraphy’s ‘essence’ eliminated the need for intensive training, as calligraphy mirrors the universe’s inherent patterns (Lin Citation2009, 342–354).

Virtual Tour, Dongpo Academy (http://view.vrhainan720.com/#/panoview/50616)

Location: Hainan

When we speak of places, they are rarely ever just geographical locations. They are tapestries woven from threads of history, culture, memory and ambition. Hainan Island is no exception. And, just as Su Shi blended the profound with the mundane, Hainan today is a site of complex ‘visioning’. In 2018, the Chinese government announced an initiative to designate the island province of Hainan a Free Trade Port, allowing for visa-free access and tax incentives for foreign trade. As it strides forward on this path of economic ambition and global recognition, the island is as much being reinvested with tales from the past – not least those of Su Shi. Notable heritage sites include a creative, immersive museum, the Dongpo Historical Culture and Art Museum and the Dongpo Academy, originally built in 1098 by Su Shi himself, where he taught and wrote. It has been rebuilt many times since and now serves as a museum and gardens dedicated to his life and work. Inevitably, alongside the preservation of ancient sites and artefacts, there is also a growing digital infrastructure, with a high regard, for example, in new methods of preserving and observing intangible cultural heritage.

In addition to Zhang Qiang’s call for an ‘international experimental calligraphy’, other contributors to this issue equally draw upon new methods and technologies to explore, rework and reimagine the past. This includes, for example, Rebeca Font’s use of motion caption imaging as a calligraphic practice; Su Wenke’s renewal and ‘expansion’ of liubai painting, and Jin and Manghani’s proposal to use generative AI techniques to reimagine the ‘lost’ poems of Su Shi. After Su Shi is not merely a chronological placement but a space of reflection, a vista that looks at how past imprints can guide, influence and mould the future.

Re-imaging Su Shi

In the broader context of global art and culture, ‘After Su Shi’ can be viewed as an exploration of how historical figures and their legacies serve as compasses in today’s globalised world. As artists, scholars and thinkers, how do we draw from the past to shape, influence and navigate our present and future? How do places like Hainan retain their unique cultural identity while adapting to a globalised framework? How does the memory of a poet from the Song Dynasty inspire, challenge and interact with contemporary thought processes?

The contributions to this special issue delve deep into these intersections and taken together craft a narrative that traverses complex aspects of Su Shi, Chinese art history and Hainan’s evolving identity. As contemporary skyscrapers rise and modern trade routes establish themselves, Hainan's undulating hills and quiet shores still whisper tales of Su Shi's sojourn; extending from its days echoing with Su Shi's verses to its current stature as an emerging global hub. Su Shi’s exile to the island, a consequence of his audacious spirit, turned into a fertile period of poetic creation. Today, the heritage sites such as the Dongpo Academy and the Dongpo Historical Culture and Art Museum are not mere architectural relics but living testimonies of Hainan's profound cultural and historical connections. Indeed, art museums the world over are not mere architectural relics but active, public spaces of profound cultural and historical lives and connections.

This special issue cannot possibly do justice to the vast influence Su Shi had on a range of artistic and scholarly domains. But, rather, the careful selection of papers seek to elucidate – in productive terms, through the lens of contemporary art practices – discrete aspects of an intricate tapestry where past intersects with present, and tradition with modernity. The articles present a diverse approach, allowing readers to see Su Shi from different perspectives.

In ‘Dialectics of Blandness: The Contemporaneity of Su Shi’s Aesthetics’, Ji Xihou and Xia Kejun astutely juxtapose Western accelerationism against the subtlety of Eastern aesthetics. By centring on the notion of ‘blandness’, rooted in Su Shi’s aesthetics, their article establishes how this former Song Dynasty concept finds contemporary relevance, especially in the works of artists like Xu Bing and Qiu Shihua. Beyond this, the authors prompt us to consider how future research might further unravel the role of such aesthetic subtleties in shaping global art perspectives amidst today’s tumultuous socio-political realities. Their account is expanded further through Yang Qing’s account, ‘Contemporary Chinese Landscape Paintings: Genealogies of Form’. Yang Qing examines the dynamic interplay between Western Formalism and Chinese traditions. Here, the recognition that Su Shi’s literati painting approach continues to inspire modern artists, suggests art’s cyclical nature, where past methodologies continuously shape current practices. This paper underscores the necessity of re-examining Su Shi’s contributions within evolving art paradigms.

Zhang Qiang and Han Jiarui’s contribution, ‘International Experimental Calligraphy’, which contextualises Zhang Qiang's established calligraphic/painting within the longer durée of Chinese art history, offers further development of Yang Qing’s argument for a richer account of ‘visual history’; finding means to extend beyond a dominate Western frame. Zhang Qiang and Han Jiarui, for example, seek to align Su Shi’s calligraphic principles with Western abstract expressionism, as a means to emphasise an universal language of art. This blurring of boundaries between traditions stimulates thought on how future artistic endeavours can be more inclusive, building bridges between diverse cultural histories.

In ‘Drawing Facing Calligraphy: Surface, Subject and Su Shi’, artist Rebeca Font begins by recalling her collaboration with Zhang Qiang at Tate Modern, in 2018. She deconstructs this encounter in thoughtful ways, helping to open up a compelling argument about how meaning attribution in drawing can sometimes stifle creativity. The paper resonates particularly with those aiming to push the boundaries of graphic arts. A key reference point is Su Shi's multi-faceted approach, which Font adopts to encourage contemporary artists to explore beyond the conventional. As such, Font’s dialogue with Su Shi’s work, alongside her innovative use of motion capture technology for drawing, helps pave the way for more such comparative studies. In a similar vein, Sun Wenke’s ‘Liubai, Su Shi, and Contemporary Art’ makes a productive reading of Su Shi’s art theory, presented as a panacea for some of contemporary art’s challenges. The emphasis on a cross-cultural discourse again looks ahead to future research, which could potentially redefine how we approach traditional artistic methodologies in a global context.

Finally, in ‘Dongpo Dream-Machine: Notes Towards an Exhibition’, Qiuyu Jin and Sunil Manghani consider the potential to seamlessly meld past and future. In this case utilising the latest developments in generative artificial intelligence (AI) to resurrect Su Shi’s artistry – or, even, as the authors playfully suggest, to ‘recover’ the lost poems of Su Shi. Set out suggestively as ‘notes towards an exhibition’, and focusing on an ambitious site-specific installation in Hainan, their paper introduces a fascinating prospect via AI, whereby the realms of history, technology and art converge, allowing us to interact with the past in ways previously unimaginable. It sets a promising precedent for how we might engage with historical figures and their works in the future, leveraging the potential of technological advancements.

Looking across all of the articles, a recurring motif is the interplay between tradition and innovation, and the innate ability of Su Shi’s ethos to traverse temporal boundaries. Whether it’s through the subtlety of ‘blandness’, the spirit of literati paintings, or the rhythmic cadence of his calligraphy, Su Shi’s legacy and enduring wisdom remains. In connecting these diverse contributions, a pattern emerges of a ‘visual history’ deeply influenced by Su Shi but also one which continually reshapes his legacy, tailoring it to contemporary sensibilities. Collectively, the articles not only elucidate Su Shi’s far-reaching influence but also beckon to uncharted territories, to questions unasked and to dialogues not yet begun. Such dynamism – after Su Shi – is not just an ode to the past but a clarion call for the future: inviting researchers, artists and scholars to continue the exploration, to delve deeper and to keep conversations and collaborations alive.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Feng Jie

Feng Jie is Professor at Hainan University, China. Her book Fashion in Altermodern China (Bloomsbury, 2022), is based on her doctoral research on ‘uniformities’ of fashion completed at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton, UK. She is a member of council for the Contemporary Urban Aesthetics Research Institute of China as well as the founder of the company Zero Degree, and as part of which, Director of the Neutral Institute.

Zhao Ying

Zhao Ying is a Research Fellow with University of Southampton (supported by the China Scholarship Council). She holds degrees from Zhongnan University of Economics and Law and Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, and has specific research interests in consumer psychology, international trade, luxury brands, international communication and cultural heritage.

Notes

1 For more on Su Shi and literati painting see: China Online Museum https://www.comuseum.com/painting/schools/literati-painting/

Reference

- Lin, Yutang. 2009. The Gay Genius: The Life and Times of Su Tungpo. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.