ABSTRACT

Interest in art school histories and the archives that support them has grown over the past decade, yet institutional recordkeeping practices and collecting, where they exist, do not tend to capture the kind of records that are most useful for research into art school pedagogies or their relationship with contemporary art discourse. This article gives an archive studies perspective on the Fine Art Critical Practice (FACP) Archive, a collaborative project to collect archival sources documenting the history of the FACP degree programme at the University of Brighton, UK, to be held at the University of Brighton Design Archives and activated through involvement of the FACP community of staff and students. It considers the records of interest to that community may lie in the context of an art school archive within an institution. It goes on to consider the example of a body of papers received from a former member of FACP staff, Mick Hartney, reflecting on some of the questions raised by this mode of collecting in terms of archival arrangement and knowledge production for the project’s future phases.

Introduction

There has been a spike in research interest in the art school and its archival records and historical narratives over the last two decades, covering regions across the country, with their different contexts and characteristics (Bruchet and Tiampo Citation2021; Butt Citation2022; Coyne et al. Citation2010; Knifton Citation2015; Llewellyn Citation2015 Mulholland Citation2019; Tickner Citation2008).Footnote1 Such work has often found that there are gaps in the primary source material for histories of art school education; some have investigated these gaps (Llewellyn Citation2015, 11). This article presents research from a multi-strand collaborative project investigating the history of, and existing archive material relating to, the University of Brighton’s distinctive Fine Art Critical Practice (FACP) course, and its potential to develop as a community archive. One of a small number of such courses at the time across the country, FACP emerged, in its earliest form, as an area of practice, in 1971, continuing in various forms until the final cohort of students graduated in 2022 (Salaman Citation2024).

The research brought together artist and FACP lecturer Naomi Salaman and archivist/researcher Sue Breakell, of the University of Brighton Design Archives, as well as various former and current students and staff. A key reference for the present article is one by Salaman, which addresses in more detail the history of Fine Art Critical Practice at Brighton (Salaman Citation2024) and its contemporary art context; the present article focuses on questions of the archive and its role as both a source and a method for this research. The project situates the course within histories of contemporary art and of art education, with my research bringing a critical archival studies perspective alongside existing studies of the art school archive, as explored in this article. Our research is linked by an interest in archive-making as itself a reflective practice. While work on art school histories through archives has often focussed on art education and contemporary art; our research suggests that a critical archive studies perspective can deepen and enrich understandings of the institutional practices and imperatives that characterise the records on which these histories rely. Such collaborative projects have borne fruit in work on other kinds of art institution or work bringing together contemporary art and institutional memory (Waters Citation2015).Footnote2

From its origins, the FACP archive project was a collaborative endeavour. As Salaman outlines, in addition to her research, the project was given additional archival energy by an interest from FACP students in their course’s history and in the creation of a course archive; for their second-year exhibition in 2014, students Lizzie How and Tilly Sleven, established a FACP Archive by creating an archive ‘counter’ for the deposit of documentation or memories, with associated deposit forms and other archival procedures, informed by conversations with the Design Archives. Although a finite piece of work, this was the origin of the FACP archive; indeed, How subsequently volunteered in the archives working on the FACP archive, establishing what became a chain of ongoing input from successive current students for several years, even beyond the closure of FACP to new students from 2020. My involvement with the course formed a further strand of exchange, leading a session on art and archives, drawing on my work with visual arts archives in art and design history. Finally, the project was shaped by its context of changes in higher education, which threatened the ecology and infrastructure of FACP, and so potentially the health of the community it sought to represent; indeed, the merger of the course with Sculpture into a new Fine Art programme in 2021, bore out these very precarities (Salaman Citation2024).

Outside archive studies, the discussion of decisions about what goes into the archive often refers back to Michel Foucault’s assertion that ‘the archive is first the law of what can be said’ (Foucault Citation1969 (Citation2002), 145). We wanted through our collecting decisions to enable the widest possible range of polyvocal conversations, present and future. Through the framework of the project, the archive’s collecting seeks to function as a live engagement between the past and present FACP community and its recorded history, where ‘the records of individuals become part of an entire community of records’ (Bastian Citation2003, 3). It addresses the following questions:

What forms and materials might constitute an archive of the Fine Art Critical Practice course, broadly conceived? Where might those materials be found?

Whose archive is it? Whose voices are, or should be represented? Who is authorised to constitute it, so that it permits not only the retracing of journeys and experiences, but the building of a community, and the possibility of new creative and historically-inflected outputs?

Presenting the snail trail as a metaphor for the archive, this article contextualises the present research in wider considerations of art school archives, situating the FACP Archive as a resource for community identity rather than as supporting institutional recordkeeping imperatives. Drawing on critical archive studies, it discusses methods of archive and information gathering which investigate not only the material, but its accumulations and accretions, as sources of evidence and identity, discussing some of these methods in practice through archive material from former FACP course leader Mick Hartney.

Snail trails

The historian Vivian Galbraith described archives as the ‘secretions of an organism’ (Galbraith Citation1948, 3). While Galbraith’s ideas about public records and history are largely outdated, this remains a productive analogy, particularly for the purposes of this essay: we might conceive of a snail moving purposefully, slowly, instinctively, within its biological system and capacities, in patterns that can be read over time, and which carry evidence and accounts (or data) of the way the organism lives: patterns and trajectories of behaviour and activities. Compared with the International Council of Archives’ standard definition of archives as ‘by-products of human activity’ (ICA Citation2019), secretion is a more organic and potentially richer analogy, less predictable, controlled or controllable – and so more reflective of the unstructured or disordered activities and processes under consideration here – the ‘messy, contingent historical dynamics at the very centre of archives’ (Ilerbaig Citation2016, 38).Footnote3

Researchers in snail biology use such secretions as a source of evidence and information, seeking to ‘detect terrestrial snail mucus trails in their native state on a solid substrate’:

The mucus trail performs a number of other functions, including the provision of mechanisms for re-tracing a path (i.e. ‘homing’) and for finding a mate of the same species by following a trail. … . It has been reported that the presence of a marine snail's pedal mucus on a surface influences the settlement of other adhering marine organisms (such as barnacles) to that surface. (Lincoln, Simpson, and Keddie Citation2004, 2)

Decisions – deliberate or incidental – about what goes into the archive are critical to this process of meaning-making. We can only account for, or indeed hold to account, the people who are recorded in archives that survive. The work of creating archives, and of collecting them, is predicated on subjectivities; the multiple voices of a community archive project engender multiple accounts of the same process of the origin of the archive, as experienced by How and Sleven as students and artists whose practice here involved engaging with ideas of archives and curating; by Salaman as a teacher, artist and researcher; and by me, as an archivist and researcher in both archive studies and art and design history. The convergence of interests allowed for the evolution of a model that felt collective – held in a formal archive, but belonging to the community, and bringing he voices of that community into the archive.

Art school archives

The University of Brighton Design Archives was formally established in 1996, following the Deposit of the archive of the Design Council at the University’s Faculty of Arts and Architecture in 1994. The Design Archives’ remit comes not from the university’s official record keeping functions, but from its pre-eminent research and teaching in design history (Woodham Citation1995). Alongside 21 other archives, deposited by designers and design organisations, the Brighton School of Art (BSA) Archive is something of an anomaly: a collection of various small sets of surviving material about the School of Art and its history since 1859 (Woodham and Lyon Citation2009). The BSA Archive is a place of refuge for marooned or orphaned material, no longer in current use, which has survived by chance or design, now significant as a historical source because of its survival and subsequent accession into the archive; these are mere fragments of the snail trail. For example, there are two press cuttings albums covering the period 1914–1962, whose origin, creators and purpose are unknown: it is unclear if they are part of a larger series, or whether they reflect a short-lived function which produced only these two items. A second example is a run of calendars and prospectuses, which came from different internal sources, and which can be reconstructed into a sequence, to form the closest we have to a series of official records. These might be described as fragments of a skeleton structure of the institution through its records, a paleontological analogy for the way that archives can ‘reconstruct past entities on the basis of remaining fragments’ (Ilerbaig Citation2016, 22).Footnote4 While material gathered in such a haphazard way can be important and has value, particularly in the absence of systematic recordkeeping survivals, it is patchy and incomplete, and therefore is limited in what it can bear witness to. From an archival point of view, this collection of fragments taken from their context makes skeletal patterns hard to trace, because the wider infrastructure is lost, and the lived experience remains out of reach.

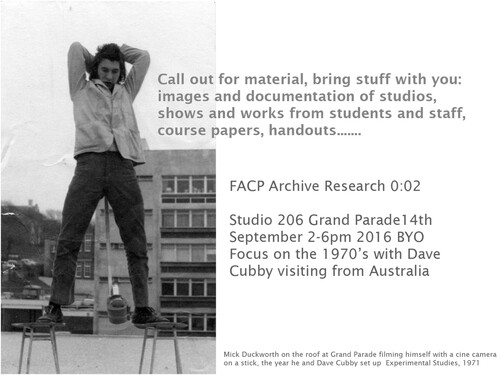

There are a number of challenges in tracing art school histories through their archives. Published items such as prospectuses do not necessarily reflect what was happening on the ground. Former Alternative Practice Original students Mick Duckworth and Dave Cubby, at a gathering organised as part of our research, described a student-led studio area in 1970, creating space for a shared interest in investigating current art and new media (). Eventually this was given its own space, subsequently gaining the name Experimental Studies, long before the first reference in prospectuses in 1974 to a fourth area of practice distinct from painting, sculpture and printmaking, or in 1987 to Alternative Practice, later Critical Fine Art Practice, and finally Fine Art Critical Practice (BSA; see also Salaman Citation2024). As in the London art schools, ‘the published curriculum took the form of a programme of pedagogic activity … made up of the courses and topics listed on the syllabus – not always actually delivered, it seems’ (Llewellyn Citation2015, 11). This lag between activity and its documentation in an ‘official’ record is indicative of a freedom that was possible, though not assumed, in the art school curriculum at that time, and the importance of the intellectual and conceptual input not only of those delivering the course content but also of more senior staff whose oversight created the culture where such freedom was possible.

Some art school histories (Tickner Citation2008; Llewellyn Citation2015; Coyne et al. Citation2010) rely on sources which only survived in private papers outside the institution; many art schools had – or have – limited or no arrangements for documenting the teaching content of their courses, beyond the bureaucratic regimen.Footnote5 The work that goes on in the studio can be lost in the space between the institution and the personal. The influential ‘A’ Course set up at St Martins during Frank Martin’s time as head of the Sculpture department is documented primarily through his personal papers at Tate Archive and later material at the Mayday Rooms in London, rather than in records kept by the School.Footnote6 If Martin had been less of a record keeper by inclination, we would know much less about this work, which is seen in his archive from his particular perspective as head of department, as distinct from that of lecturer or student. Much of what researchers want to know may not have been documented at all: evidently not all activities generate formal or informal records to answer such questions as ‘what was taught and how?’, ‘how did the course evolve over time?’ or even ‘what was it like?’.

Community archives and collaborative practices

In institutional archives at least, the voices represented tend to be those of the powerful, such as senior managers and administrators, who carry out functions that need to be recorded for formal or regulatory purposes, which inevitably exclude certain voices. The community archives movement emerged as a reaction to the impenetrability and exclusivity of such monolithic archives, establishing the notion of community archives as ‘counter hegemonic tools’ (Flinn and Stevens Citation2009). Often such archives bring together geographical, demographic or special interest groups whose voices are under-represented in formal institutional archives; they recognise that ‘the ability of a community to conceptualise itself, now and into the future, depends to a great extent on its capacity for remembrance, and its ability to express that remembrance communally’ and the power of ‘highlighting the documentation of multiplicity and dissent … we can foreground the intimacy between knowledge and power by being as transparent as possible about our own archival choices and their consequences’ (Caswell Citation2014, 41).

Having no formal collecting function for University records gives the Design Archives a freedom here to collect for the University community rather than by regulation – most of these records would not otherwise be preserved. Combined with the Design Archives’ principle of research-informed stewardship this allows creative and dynamic work across a breadth of concerns and practices. The FACP archive-making project was conceived as a community of archivists, teachers, artists, researchers and historians, starting with the question: what constituted a record of FACP? Of Tate’s project ‘Art School Educated’, Llewellyn asks ‘How can historians use written language, spoken accounts and documentary evidence to describe the inculcating of skills in the education of artists, something that many hold to be – self-evidently – a visual and manual process?’ (Llewellyn Citation2015, 153). Arguably, Fine Art Critical Practice has a slightly different orientation from such a framing of the fine art degree, given its emphasis on criticality as a practice – online course details for 2018 admission declared that students would be helped to ‘acquire physical, critical and cognitive skills together with professional practice and historical understanding’Footnote7 – a nuance which offers the potential of a closer matching of understandings across the archival project’s participants. Salaman and I converged our interests into a project of the broadest possible future value and representation, a case study of art education not just as a process, as seen in How and Sleven’s work, but as a historical investigation (Salaman) and a subject for archival collecting (Breakell). To bring together this community, Salaman’s initial activities gradually built up momentum: a Facebook group, an outdoor reunion, direct contact with former staff and students, a web page as a focus.

The work which How + Sleven showed in their exhibition articulated a critical stage in the birth of the archive – Flinn and Stevens write that ‘the moment when an archive is created and named as such is a moment of reflection and often a response to other societal conditions’ (Flinn and Stevens Citation2009, 8). Creating a place of deposit that was both actual and conceptual, their associated statements about the work firmly establish it as a community archive, and indeed acknowledge the consequent accountability of its custodians:

The content of the archive belongs to the course

It is not our archive

Our role is spokespeople of the archive

The creation of the archive will itself be archived (How + Sleven, BSA)

A characteristic of community archives that may be particularly valued by those they represent is that by remaining outside the formal archive or collecting agency, they retain ‘the authority to tell those stories from within’ (Flinn Citation2007, 156). That said, we must be aware of Anna Sexton’s question: ‘Does bringing in counter-narratives into the walls of the institutional archive release that knowledge from subjugation by clothing it with legitimacy? Or does it in fact further subjugate that knowledge under the weight of the dominant narrative?’(Sexton Citation2020, 5)Although the FACP archive is held within a formal archive in an institution, being constituted as a research project enshrined the retention of some of the course’s experimental capacity. Given the rich and longstanding relationship between fine art and the archive (Callahan Citation2022) with artists appropriating, testing and reworking ideas of what the archive is, this project aspired to a certain creative freedom in its constitution, thinking about the possibilities of the archive as a subject of inquiry itself, in its formulation and its practices. Recent scholarship and practice in archive studies, history and socially engaged art has framed meaning-making as an ongoing generative act which involves not only creators but also archivists and users (Breakell Citation2024). Against the traditional linear process (creator – > archivist as preserver - > historian as anointed interpreter) was posited a continuum on which multiple agents carry out interpretive acts, bringing records in and out of currency and into new forms of engagement. Collaborative engagement depends on archival practices that facilitate their re-configuring and re-authoring by each user, without changing the start point of the documents: a thousand and one nights of stories are possible, with storytelling a shared, community-affirming activity, and as long as the archives keep talking, and telling new stories, whether shared or individual narratives, they have ongoing agency. The co-curating of the FACP Archive endeavours to retain a principle of shared authority and co-production of knowledge as a methodology.

Collecting the FACP archive

For the Design Archives, the FACP Archive project also operates as a case study for the documentation of other courses. Its findings indicate the kinds of course-related records that are generated by the processes of the university, and the means by which those records may or may not be preserved, deliberately or accidentally. Bastian’s notion of a community of records imagines ‘multiple layers of actions and interactions between and among the people … within a community’ (Bastian Citation2003, 5), and the project is an opportunity to consider these layers and the perspectives they represent, the strands of multiple narratives that we might wish to capture; and the factors that prevent the survival of other kinds of records. There are many reasons for a lack of course documentation, including lack of space, time or money, or even of an awareness of the value of these records; relocation of offices through the inevitable changes and restructuring of the institution from polytechnic to university, as well as the associated conceptual changes in institutional culture. Such fragmented layers of processes of record creation and accumulation/retention are further complicated by the many voices and community perspectives at play: in the case of FACP, these include ‘core’ voices of course staff, students, alumni, as well as visiting lecturers and external examiners, who may enter the community only for moments of close engagement, scrutiny or reflection; there are further perspectives from the wider and changing university context within which the course sits: the Department of Fine Art, the various iterations of the School of Art and its container Faculty/College (now disbanded). Beyond that, the processes that generate records are influenced by the wider art world and art discourses, and art education within the national political and government framework. While these form concentric circles of potential communities, we should not assume a uniform sense of belonging across these circles. Llewellyn identifies in the history of art education ‘a culture of individualism … artists’ resistance to being placed, yet alone contained, within any named set, party, team or faction … .’ (Llewellyn Citation2015, 19). Indeed, for both staff and students, their creative and intellectual content is personal, and for teaching staff, in the intensely contested political context of the university, this can be seen as their commodity, their capital.

My research proposes a model of categories of material for the university archive based broadly on the functional requirements of these distinct entities:

Official records, generated by the requirements of the university’s core activities such as regulation, review, moderation and examination.Footnote8 These are the most likely to be actively retained for at least a period of time, and largely do not represent community activities, but rather processes which exercise control over the community of staff and students for specific bureaucratic ends within national regulatory frameworks.

Local records kept in schools and departments, core for their record keeping and community memory. This includes, for example, the documentation of student shows as part of the community’s creative capital, rather than as a product of course matriculation and modulation; and teaching content at a more general level. These are easily lost if there is no designated responsibility for them, though they are increasingly brought within current contractual frameworks.

Personal records kept by staff and students, which may contain detailed teaching content. These are core to the individuals because they document the intellectual/personal content of their teaching, or their response to teaching: how they taught or were taught. These form two subsets – two sides of a transaction – of teaching and of being taught – although, as we have seen, in the art school those distinctions are less clear cut, a factor which has been identified as part of what makes the art school different, particularly in the more experimental art schools.Footnote9 Furthermore, teaching may be done by staff fully employed by the university, whether on full or part time contracts, who may have certain obligations for record keeping of type (1) or (2), or by casual or temporary staff, who may not have these accountabilities in their terms of engagement. Given such precarities, the survival of personal records depends much more on individual’s inclination to retain things, and the associated risk of loss. Broadly speaking, these paper records might include records of teaching content and planning, student work, literature and sources, group activities and outings, but also personal accounts.

Our project, dating back to the work of How and Sleven, naturally focussed on 2 and 3 as the likely location of records in which the FACP community has both an interest and an investment, and which support a sense of belonging; the project seeks to collect in a way that reflects the agencies of these categories. Further, the multiple streams through which this material – particularly the personal records – is generated illustrate the potentially complex provenances of a community archive.

A further category of material is the retrospective and reflective accounts and oral testimonies created as part of the project – a different kind of evidence, produced by the act of remembering, rather than as a ‘secretion of an organism’ going about its business. As such they are an artificial contextual envelope, subject to the particular conditions of oral history work (Thompson Citation2000). Finally, while the present project does not address digital records, their place in the landscape should be acknowledged. Research reveals the absence of digital records of FACP student work for the last 10 years or so. Such records were informally understood to be in existence but could not be located, neatly illustrating how the problems of benign neglect in the analogue environment can easily become irreversible loss in the digital world. This challenge is widely discussed in archive literature beyond higher education; more specifically, Laura Uglean Jackson warns that this threat of technical obsolescence, heightened by the under-resourced and diverse sphere of university archives, ‘will bring an end to the serendipitous acquisition of records useful to patrons that was possible with non-digital material’ (Jackson Citation2015, 91–92).

A course leader’s archive

Given these multiple provenances, context becomes vitally important for the understanding, the assimilation, the explanation of the records. Our work with former course leader Mick Hartney can be used to illustrate and reflect on some of these questions in practice. Hartney was informally involved with the course from the early 1970s, was formally part of its teaching from around 1984, later becoming Course Leader until his retirement in 2009, had amassed the largest body of archive documentation identified so far, and it seems likely to remain so. His involvement with the course over 30 years means there is a unique continuity in that strand of engagement, which mitigates for it being only a single perspective at present for much of that period. The documents support a view that Hartney’s working method as a tutor involved careful curation of the course content, particularly those documents which articulate his aspirations for the course, such as his ambitious document ‘100 Artists Approximately: A survey and bibliography of contemporary art compiled and introduced by Mick Hartney’. He conceived this as ‘a continuous and open-ended learning resource for the Critical Fine Art Practice Programme’ or ‘an attempt to provide an illustrative, rather than a descriptive, response to the question so often asked: “What is Alternative Practice?”’ (BSA). Such documents do not function to show how the students were taught, but they show the content and some of the terms of engagement.

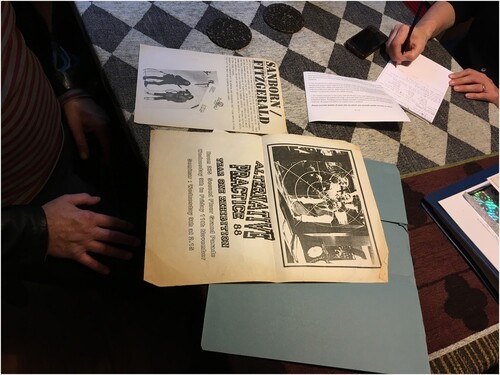

In fact, the situation of Hartney’s archive shaped the methods we evolved, its transfer a significant event where an archival perspective offered particular insights. Because his archive was in storage, he suggested the best way for us to have access was for him to bring tranches of papers to his home, where we could meet to discuss them, before taking them to the Design Archives. Excavated in this way, the papers were not chronologically or otherwise organised: they were a sedimented chunk whose unearthing is better described as geological, or archaeological. We met for a number of sessions at intervals from August 2017 onwards, during which our method evolved (). At the first session, Hartney asked what Salaman and I wanted to know, perhaps expecting us to direct the conversation with our questions. But, bearing in mind that both our questions and Hartney’s memories could further direct and limit the knowledge available from the material, we wanted to see what the archive knew, letting it emerge as a parallel source alongside his recollections. The material gives its account of a past time, now seen by Hartney within a retrospective contextual envelope. We did not want to direct the conversation, but to allow these two voices to emerge, so we simply asked Hartney to tell us about the material in front of us all. And so the sessions proceeded with the material revealed by Hartney, piece by piece, with him explaining and contextualising it, in a kind of performative animation, or ‘performance as documentary … positioning the relic as score’ (Clarke et al. Citation2018, 12). Salaman and I asked qualifying or associated questions, but we did not direct the conversation. The archive was the start point, taking centre stage, the content of the record stimulating comment and discussion while enabling ‘counter-hegemonic practices of self-archiving’ (ibid., 12). These collaborative practices take place against the grain of the institution’s functions and transactions and indeed of conventional archive practice.

Figure 2. FACP archive material under discussion with Mick Hartney, October 2018. Photograph by Naomi Salaman.

In this performative process, we three participants fell into habits of where we sat, and assumed particular roles and functions in this performance event: I took notes, Salaman took photographs, the conversation was usually recorded, in sound or in both sound and film. We documented and responded to Hartney’s performance of the archive. Meanwhile, with the positionality of an archive practitioner, I looked for patterns in the material I saw passing in front of me, visually appraising the records here in an active responser to the performance. Nevertheless, at this stage the spotlight, and therefore the performative meaning of the material, belonged largely to Hartney and his narrative. Thus the arrangement in which the documents were presented to us carried its significance, not least their agency in the unexpected ways they sparked off each other in this apparently random sequence. Any detectable original order in the papers was an archaeological logic of accumulation, rather than a paleontological one. The recurrence of similar materials offering evidence of regular activities and functions which both ‘secrete’ records and create structures: for example, the documentation of the student shows evidenced these events as landmarks within the linear sequence of a student journey through the course, with shows in first, second and third years marking stages in the student trajectory of development and experience. These records did not emerge from Hartney’s papers sequentially; the excavated archaeological structure dictated the sequence of his narrative. This raised an archival question about the future arrangement of the papers: a meaningful understanding of the order they were deposited in would be dependent on access to the narration. Using the archive in this form does not allow for a conventional chronological review, and for a researcher interested in seeing the shape of records from the 1970s, for example, the material resists any overall sense of the course made possible by viewing a sequence or group of documents relating to a particular time period. For the interim, as research continues, they have been retained as acquired, pending further investigation of the knowledge production first that this material makes possible and second that is desired by the stakeholders in this community of records.

Conclusion

The FACP project incorporates a reflection on how archival principles and practices inform process, as we collate material into a resource for future research that has meaning archivally, historically and experientially, giving account to its ‘native state’ as far as possible. Both remembering and recording the radical history of FACP acquire a new significance at a time when educational freedoms, especially those of the art school, are under increasing challenge: John Beck, who works with former FACP course leader Matthew Cornford on histories of art schools, writes of a ‘sense that we are standing among the ruins of publicly supported and publicly situated art schooling, and all that might mean in terms of critical and cultural enrichment and diversity’ (Beck and Cornford Citation2014, 8). Under these conditions, the formal institution of the Design Archives is physically both a home and a focus for the FACP archive, and thus for the surrounding community and its identity, available for activation and engagement.

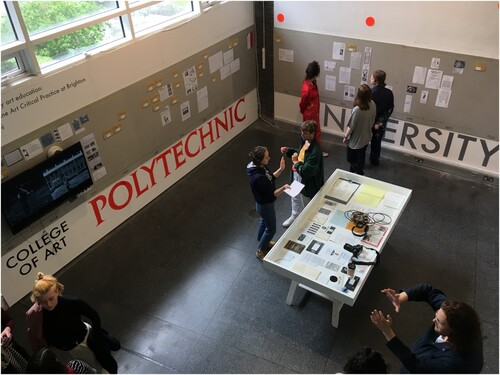

In 2019, an exhibition in the Foyer Gallery at the University of Brighton School of Art & Media presented work to date on the FACP archive project, its history and milestones mapped against the wider context of changes in art education (). The inclusion of a work by John Hilliard To and From (16 mm, 3.35 min, Brighton Museums), filmed in the same quad that was visible to visitors through the windows of the exhibition space, literally brought this period in FACP’s history back to its place of origin, emphasising the experimental practice which Hilliard engendered there. Marking a milestone in the project, the exhibition was followed by a pause in research, made more definitive by the arrival of the Covid pandemic in 2020. The merger of FACP with Sculpture into a new Fine Art course, with the final FACP cohort graduating in 2022, has clearly changed the status of a project which aimed to highlight the course’s experimental pedigree (Salaman Citation2024).

Figure 3. ‘Excavating Contemporary Art Education; Tracing the History of Fine Art Critical Practice at Brighton’, Foyer Gallery, Grand Parade, University of Brighton, April 2019. Curated by Naomi Salaman and Sue Breakell. Photograph by Naomi Salaman.

The work presented here is the early stages of what has potential for considerable further work: more material to be excavated and collated – constructing the archive – and further stages of research and for participatory animation of the archive with its now finite community. Already, our project has both expanded understanding of the complexities of the art school archive and the boundaries of the community of records generated through art school teaching; already it has generated new knowledge of the history of experimental practice at Brighton and in the wider context of the small number of courses of this kind at the time. The conceptual framing of this project as a community of records offers models and theories to enrich our understandings of its formation and its meanings, supporting the evolution of new forms of relations between the archive as institution and the community whose records it cares for. Participants work collaboratively in all areas – collecting and stewardship have been integral parts of the research and creative practice engagements with the archive since the inception of the project, with the aim to ‘creatively and collectively re-envision the future through archival interventions in representations of the shared past’ (Caswell Citation2014, 49). While incorporating a formal archival context, with its attendant theories and practices, the FACP Archive is not defined by those frameworks: in its performative potential it is ‘a making-place where the document and its boundaries are sufficiently uncertain to generate unexpected questions and offer conversations for future practices’ (Clarke et al. Citation2018, 29). Stretching conventions and expanding understandings of the institutional archive, it permits a more multi-channel and poly-vocal constitution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sue Breakell

Sue Breakell is Archive Director and Principal Research Fellow at the University of Brighton Design Archives, UK. She was formerly Head of Tate Archive, London and War Artists Archivist/Museum Archivist at IWM London. Her research bridges critical archive studies, twentieth century art and design history and material culture.

Notes

1 A session at the Association for Art History Conference, University of Brighton 2019 entitled ‘Art Education: the making of alternatives?’ sought to bring together current research on the subject, with Salaman and Breakell among its organisers – see https://forarthistory.org.uk/conference/2019-annual-conference/art-education/; see also Ignorant Art Schools project https://www.dundee.ac.uk/events/ignorant-art-school-five-sit-ins-towards-creative-emancipation.

2 For example, the event Why Look Back? Contemporary Art & Institutional Memory, Nottingham Contemporary, November 2024. https://www.nottinghamcontemporary.org/whats-on/why-look-back-contemporary-art-institutional-memory/

3 The ICA’s longer definition is as follows: Archives are the documentary by-products of human activity retained for their long-term value. They are contemporary records created by individuals and organisations as they go about their business and therefore provide a direct window on past events.

4 Ilerbaig situates this paleontological metaphor in the context of nineteenth century developing epistemologies including that of archives.

5 For example, Tickner drew on material in private hands including that held by David Page, now at Tate Archive (TGA 200811).

6 Tate Archive, Frank Martin Archive, TGA 201014; A Course Archive, Mayday Rooms http://maydayrooms.org/archives/a-course/accessed 10 December 2018.

7 Course details accessed 10 December 2018.

8 Centralised record keeping culture is not consistently embedded in departmental practice and retention focus on corporate records for current business purposes, rather than long-term historical questions taking into account future research needs.

9 Unpublished interview with John Hilliard by curator Jenny Lund.

References

- Bastian, Jeannette A. 2003. Owning Memory: How a Caribbean Community Lost Its Archives and Found Its History Westport. CN: Libraries Unlimited.

- Beck, John, and Matthew. Cornford. 2014. The Art School and the Culture Shed. London: Kingston University.

- Breakell, Sue. 2023. “‘The True Object of Study’: The Material Body of the Archive.” In The Materiality of the Archive: Creative Practice in Context, edited by Sue Breakell and Wendy Russell, 33–47. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Breakell, Sue. 2024. “Generative, Iterative Acts: Working with Archives.” In Tania El Khoury's Live Art: Collaborative Knowledge Production, edited by Laurel McLaughlin and Carrie Robbins, 53–64. Amherst, MA: Amherst College Press.

- Bruchet, Liz, and Ming Tiampo. 2021. Slade, London, Asia: Contrapuntal Histories Between Imperialism and Decolonization 1945–1989 (Part 1).” British Art Studies 20. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-20/tiampobruchet.

- Butt, Gavin. 2022. No Machos or Pop Stars: When the Leeds Experiment Went Punk. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Callahan, Sara. 2022. Art + Archive: Understanding the Archival Turn in Contemporary Art. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Caswell, Michelle. 2014. “Inventing New Archival Imaginaries: Theoretical Foundations for Identity-Based Community Archives.” In Identity Palimpsests: Archiving Ethnicity in the U.S. and Canada, edited by Dominique Daniel and Amalia Levi, 35–55. Sacramento, CA: Litwin Books.

- Clarke, P., S. Jones, N. Kaye, and J. Linsley. 2018. Artists in the Archive: Creative and Curatorial Engagements with Documents of Performance art. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Coyne, R., H. Westley, P. Kardia, and M. Le Grice. 2010. From Floor to Sky: The Experience of the Art School Studio. London: A &C Black.

- Flinn, Andrew. 2007. “Community Histories, Community Archives: Some Opportunities and Challenges1.” Journal of the Society of Archivists 28 (2): 151–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/00379810701611936.

- Flinn, Andrew, and Mary. Stevens. 2009. “‘It is noh mistri: we mekin histri'. Telling Our Own Story: Independent and Community Archives in the UK, Challenging and Subverting the Mainstream.” In Community Archives: The Shaping of Memory, edited by Jeanette A Bastian and Ben Alexander, 3–28. London: Facet (Principles and Practice in Records Management and Archives).

- Foucault, Michel. 1969 (2002). The Archaeology of Knowledge. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Galbraith, V. H. 1948. Studies in the Public Records. London: Thomas Nelson.

- ICA (International Council on Archives). 2019. ‘All You Have Ever Wanted to Know About Archives and ICA’ (Accessed January 2019). https://www.ica.org/en/all-you-have-ever-wanted-knowabout-archives-and-ica.

- Ilerbaig, Juan. 2016. “Organisms, Skeletons and the Archivist as Palaeontologist: Metaphors of Archival Order and Reconstruction in Context.” In Engaging with Records and Archives: Histories and Theories, edited by F. Foscarini, H. MacNeil, B. Mak, and G. Oliver, 21–40. London: Facet.

- Jackson, Laura Uglean. 2015. “So Much To Do, So Little Time: Prioritizing to Acquire Significant University Records.” In Appraisal and Acquisition: Innovative Practices for Archives and Special Collections, edited by Kate Theimer, 91–104. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Knifton, R. 2015. “ArchiveKSA.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies 21 (1): 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856514560297.

- Lincoln, B. J., T. R. E. Simpson, and J. L. Keddie. 2004. “Water Vapour Sorption by the Pedal Mucus Trail of a Land Snail.” Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 33 (3-4): 251–258. Accessed 15 September 2018. http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/161500/1/Lincoln-Water-Vapor-Sorption-FINAL-SRI.pdf.

- Llewellyn, Nigel. 2015. The London Art Schools: Reforming the Art World, 1960 to Now. London: Tate Publishing.

- Mulholland, Neil. 2019. Re-Imagining the Art School London. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Salaman, Naomi. 2024. “The Non-Art Project: Notes on the Emergence of Experimental Studies at the College of Art, Brighton Polytechnic.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 23 (2).

- Sexton, Anna. 2020. “Mainstream Institutional Collecting of Anti-Institutional Archives: Opportunities and Challenges.” In Communities, Archives and New Collaborative Practices, edited by Simon Popple, Andrew Prescott, and H. Mutibwa Daniel. Bristol: Bristol University Press/Policy Press. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10071336/1/ASWellcomeChapter.pdf.

- Thompson, Paul. 2000. The Voice of the Past. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tickner, Lisa. 2008. Hornsey 1968: The Art School Revolution. London: Francis Lincoln.

- Waters, Susannah. 2015. “The Glasgow Miracle Project: Working with an Arts Organisation’s Archives’.” Archives and Records 36: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23257962.2015.1018151.

- Williams, Caroline. 2006. Managing Archives: Foundations, Principles, and Practice. Witney: Chandos Publishing.

- Woodham, Jonathan M. 1995. “Redesigning a Chapter in the History of British Design: The Design Council Archive at the University of Brighton.” Journal of Design History 8 (3): 225–229. JSTOR, Accessed 25 January. 2024, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1316034.

- Woodham, Jonathan, and Philippa. Lyon. 2009. Art and Design at Brighton 1859-2009: From Arts and Manufactures to the Creative and Cultural Industries. Brighton: Faculty of Arts & Architecture, University of Brighton.

Unpublished sources

- Brighton School of Art Archive (BSA), University of Brighton Design Archives www.brighton.ac.uk/designarchives

- Lizzie How + Tilly Sleven, ‘The Fine Art Critical Practice Archive’, leaflet for degree show, 20 January 2014. FACP Archive

- Mick Hartney ‘100 Artists Approximately: a survey and bibliography of contemporary art’. FACP Archive.

- Brighton School of Art calendars and prospectuses