ABSTRACT

In an era of cyber threats, drones and artificial intelligence, will the future of inter-state warfare at sea inevitably be high tech? This paper challenges assumptions about the ubiquity and importance of high technology in any future naval clash between China and America. While taken as a given that the most advanced weapons and platforms will be vital to such a conflict, both navies also employ legacy weapons and older technologies. A case study is offered here of medium calibre naval guns, seen on the very latest naval surface combatants of both China, the USA, and other major navies. Why do modern navies persist with such seemingly old weapons? To what extent are they likely to be important in any future conflict? It is argued that overly focusing on the latest high-tech weapons risks a type of naïve technological determinism and obscures how high- and low-tech weapons are often complementary. It is this synergy that requires greater understanding and attention. Moreover, relatively low-tech weapons like guns could be surprisingly relevant in the context of hybrid and amphibious warfare scenarios involving China and the USA, especially for the diplomacy of the “shot across the bows”.

Introduction- An impending high-tech Sino-American war?

Speculation on any future conflict between the USA and China has usually included claims about the importance of advanced weaponry. This focus on high technology can be found across academic research (Tangredi Citation2019; Johnson Citation2017), in the doctrinal statements of western navies (MoD, 2018, 142–145; ADF, 2019, 8; Bekkers et al. Citation2019, 79), defence think-tanks (Wilhelm, 2019), or within “futurist” literature (Brose Citation2020, xii–xv; Dunlap, 2010).

These sources typically lavish attention on the latest Chinese or American missiles, cyber warfare, artificial intelligence, drones, and stealth technologies. Space sensors are also sometimes highlighted, as are disruptive technologies; hypersonic missiles,Footnote1 lasers and electromagnetic rail guns.Footnote2 Accordingly, we are led to believe a future clash between China and America at sea will be a dazzling high-tech contest.

Chinese strategic views are also dominated by “systems thinking” which privileges technological modernisation, or as Engstrom puts it: “as new technologies such as rail guns and hypersonic glide vehicles, to name only two – become commonplace, they will be added into the PLA’sFootnote3 operational system” (Citation2018, 121). Blasko (Citation2011) claims that high technology actually drives Chinese military doctrine so that China’s navy (PLAN) have embraced high technology, with foreign-derived designs increasingly complemented by domestic innovations (DIA, 2019, 2, 24).

High-tech weapons are also a staple of “techno thrillers” that can shape popular and even elite perceptions (Elhefnawy Citation2019; Young and Carpenter Citation2018). Singer and Cole’s (2015) Ghostfleet is perhaps the best known of the genre, featuring numerous high technology “plot devices”: destruction of US satellites; intelligent underwater drones; and Chinese cyber-hacking “militias” taking down the entire US GPS navigation system. In one vignette, a U.S. Navy Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) is doomed because of its allegedly puny gun, followed later with a high-tech denouement when a US warship with an electric rail gun destroys the Chinese fleet (Singer and Cole, Citation2015, 367–370). Chinese action movies such as Wolf Warrior II (2015) or Operation Red Sea (2018) mirror this genre by giving a starring role for China’s ultra-modern destroyers (Raleigh Citation2019).

Even some of the growing literature on hybrid “grey-zone” conflict between the USA and China stresses cyber and other high-tech forms of aggression. Cronin and Neuhard (Citation2020, 18–20) highlight how Chinese strategy is pitched towards “information dominance” involving high-tech mapping, exploration and ultimately subversion of the “internet of sea things”. Hicks (et al. 2019, 9, 30) notes how China might use high-tech lasers or jamming technologies to degrade US satellites or possibly use “deep fake”Footnote4 technologies. Yet to date, Chinese hybrid operations at sea have mostly featured relatively low-tech clashes, often involving ship ramming, bumping, water cannons, and occasionally dazzling lasers (Martinson and Erikson, 2019, 295–297).

More generally, few scholars have usefully broadened the discussion away from high-tech weaponry. Heginbotham (et al., Citation2015) and Kaplan (Citation2010) stress the importance of geography shaping any future conflict. Gagliano (Citation2019) has drawn attention to the importance of allies for both China and America in any future war. Biddle and Oerlich (2016, 12, 16) argue claims of an impending Chinese high-tech hegemony are over stated when one considers targeting complexity, limitations of radar and physical distances. Kirchberger (Citation2015, 223–231) in her assessment of rising Chinese naval power is also careful to stress a more limited capability that is not yet at technological parity with the US, but closing the gap. These sources of qualification notwithstanding, within the evolving debate on any future Sino-American war, the role of high technology weapons and systems has become central.

Challenging narratives of technology “war winners”

Unfortunately, an emphasis on high technology risks technological determination: the idea that war-winning high technologies are essential to victory (Walton Citation2019). Although the claim of technological determinism can be lazily thrown around (Roland Citation2016, 32; Defoe Citation2015), it is alive and well in what Thomas Mahnken has described as “simplistic” views which exaggerate the importance of technology on warfare (Mahnken Citation2008, 220, 226).

Questioning the accepted wisdom that high-tech weaponry will be central to any future Sino-American clash is therefore entirely valid to balance the focus on high technology weapons with a more rounded view. Indeed, much of the commentary on high-tech weaponry deployed in the Pacific has mostly ignored the literatures on war and technology (Roland Citation2016; Black Citation2013; Hacker Citation2005).

Assumptions that high technologies are the essential variable for war success are not borne out historically, even for larger scale inter-state wars (Raudzens Citation1990; van Creveld, 1989, 232: Gray Citation1993). As Richard Bitzinger has observed “in reality, military power is synergistic, a collection of a number of disparate, mutually supporting systems … More critically, however, the idea of ‘game-changer’ weapons trivialises the whole operational art of war. It reduces warfighting to just hardware. War and conflict are more than just equipment – they are tactics and training, leadership and morale, geography, logistics, and sometimes just plain luck. Technology alone does not win wars.” (Bitzinger Citation2018)

Relatedly, there is a debate on the over-reliance upon high technology warfare within the “western way of war”, and in particular American doctrine where “technology offsets” have been aggressively pursued as part of the “American way of war” (Mahnken Citation2008, 226–227). This paper is also of relevance for the debate on the excessive costs of military modernisation, or the procuring of ever smaller numbers of ever more sophisticated high-tech weapons (Lake Citation2019, 38–74 and 72–83). Such concerns have also been addressed as the trade-offs inherent between “quality versus quantity” in war mobilisation, production and deployment of forces (Handel Citation1981). According to Lake, there has been a 30% reduction in US warship numbers between 1950 and 2016 and yet the US naval budget has increased threefold in constant dollar terms by 2017 (Lake Citation2019, 144).

Attempts to argue for a more balanced “high-low” mix of technology, ships and weapons have been articulated within the US Navy as far back as Admiral Zumwalt’s tenure as CNO in the early 1970sFootnote5 (Lake Citation2019, 151; Zumwalt Citation1976, 72). Such debates continue to some extent today with attempts to procure “off the shelf” frigate designs (FFGX) of limited capability (Lake Citation2019, 169).

Yet the US Navy’s obsession with high technology is most obviously revealed in the troubled DDG-1000 Zumwalt class, which were designed in the 1990s to replace modernised World War Two era Iowa class battleships, that had been repeatedly employed on naval bombardment missions in Vietnam, Lebanon (1984) and the first Gulf War (1992).

The futuristic DDG-1000 was supposed to be fitted with a completely new Advanced Gun System (AGS) capable of long-range precision shelling. Yet only three of these ships were ordered because of uncontrolled cost overrun: an increase of 578% in 2018 dollars or over 8 billion dollars per ship. The advanced munitions rose to 800,000 USD per shell (Lake Citation2019, 159; Fredenburg Citation2016), whereas existing US naval rounds are estimated to cost between 1,200 and 2,200 USD and the US Army’s most advanced guided artillery projectile costs about 68,000 USD (Mizokami, Citation2016). As of 2020, the AGS is completely inoperable because no munitions were funded (O’Rourke, Ronald/CRS Citation2020a 4, 13). These ships may in future be modified to fire other munitions but only at considerable expense. For now, their only workable weapons are missiles and small cannon. As an exercise in replacing “old” guns with high technology ordnance, they have been a singular failure (Fredenburg Citation2016).

The Shock of the old and the ubiquity of technological hybridity

A focus on exclusively high technology weaponry also obscures how prevalent older and lower-technology weapons are in service and how their use in actual combat operations is ubiquitous. Many existing naval weapons, such as mines,Footnote6 medium calibreFootnote7 guns, and even torpedoes, are surprisingly old in their origins, although they have been often updated.

This phenomenon has been described by David Edgerton (Citation2006) as “the shock of the old”. His claim is not only that relatively old war technologies are commonplace but they are frequently responsible for much of the killing (2006, 143–146). However, his thesis is about more than observing a simple longevity of certain weapons, but also that we should be alert to the ‘complex interaction of the old and the new in warfare and of the dangers of naïve futurism” (Edgerton Citation2006, 153).

We can see the ubiquity of older naval weapons in recent post-Cold War conflicts described in which shows that guns are the most frequently employed weapon type, although we can note that these conflicts have not been interstate wars among great powers with large navies. Nonetheless, the ubiquity of old and new weapon types coexisting is striking.

Figure 1 Employment of Naval Weapons by Type in Post Cold War Maritime Engagements 1991-2020. Sources: various

Moreover, while many “old” naval weapons persist in modern fleets, they are often upgraded in service. Navies then combine low or intermediate technology weapons together with some novel high technologies. In this context, precise definitions of low, intermediate and high technology are elusive, but concrete examples help. Bayonets are emphatically low technology weapons. Yet they are still employed even by modern western armies (Stone Citation2012). An example of an intermediate level of weapon technology can be found in the widespread production of small arms and munitions (Bourne Citation2012, 30).

High technology weapons are associated with the emergence of nuclear weapons, electronics and the “information revolution”, although the first two of which have their origins in the Second World War (Hacker Citation2005, 256, 266). Relatedly, there have been claims of a revolution in military affairs (RMA) from the fusion of new digital technologies, a discourse which has achieved a notable reception in America but also in China (Black Citation2013, 240). Claims for a contemporaneous RMA are widely regarded as oversold, not least because some revolutions in military art appear without new technologies (Sullivan Citation1998), and it downplays the typically low-tech nature of contemporary wars in the non-western world (Black Citation2013, 229, 241–242).

Moreover, in many cases “high technologies” are added to older weapon and thus their overall impact is more evolutionary and incremental (Black Citation2013, xi). This means they are effectively “hybrid” weapons which combine low, intermediate and high technologies. One recent example is the American GPS guided smart bomb (JDAM), which is actually a kit that modifies “old” dumb unguided bombs (Black Citation2013, 204).

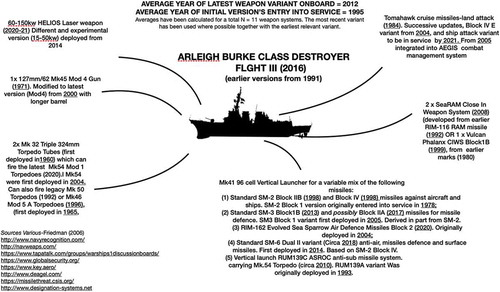

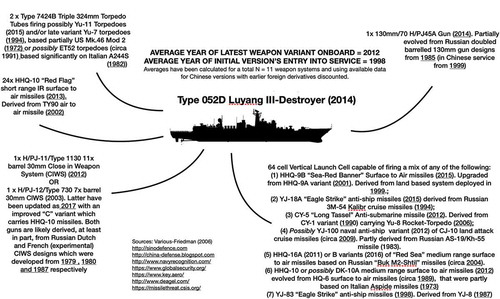

We can see such “hybridity” more clearly if we take an example of recent classes of US and Chinese destroyers (see and ). A mix of very new weapons (such as lasers being fitted on some US ships) and very old systems (current US naval guns can be dated back to 1971) is apparent. The “average” age of the most modern weapon variants aboard these two vessels is in fact the same: 2012. However, the average age for the initial or historic variant of their weapon systems was 1995 for the US ship and 1998 for the Chinese vessel, meaning they embody technologies first deployed over 20 years before entry into service of the American vessels (2016), or 16 years for the Chinese vessel (2014).

Figure 2 Old Made New? Weapons* on a recent US Navy Destroyer by Age/Update.(estimated date of entry into service is in brackets; *only the main or larger weapon systems are detailed.)

Figure 3 Old Made New? Weapons* on a recent Chinese Destroyer by Age/Update.(estimated date of entry into service is in brackets; *only the main or larger weapon systems are detailed.)

In many cases, this even understates the importance of technological legacies. Some American weapons go back to 50 years or more, at least as regards key features of their design, notably torpedo launchers (1960), medium calibre guns (1971) and the Standard family of missiles (1970s). For China, there is a pronounced legacy from Russian, French and Italian naval weapons and systems of the 1980s and 1990s.

The anachronism of Naval Guns?

What is examined here is just one case of “technology hybridity”: the ongoing existence of medium calibre guns, which are usually classed at between 76 mm (3 inch) and 127–130 mm (5–5.1 inch), although 57 mm (2.2 inch) and 155 mm (6.1 inch) calibres might be considered the lower and upper ranges for this category (Williams Citation2011). For the US Navy, a total of 89 surface warfare ships are equipped with 111 127 mm (5 inch) guns (Bradley et al. Citation2020, 10). As of 2020, the PLAN has 130 mm guns on probably 18 destroyers; 100 mm guns on circa 31 others; and smaller 76 mm guns on perhaps 75 frigates or corvettes.Footnote8

The continued existence, role and updating of such “old weapons” require some explanation: are they simply legacy weapons that navies are too conservative to cast off? Are they kept for just lower intensity missions? Or does the process of hybridisation through modernising mean they remain useful?

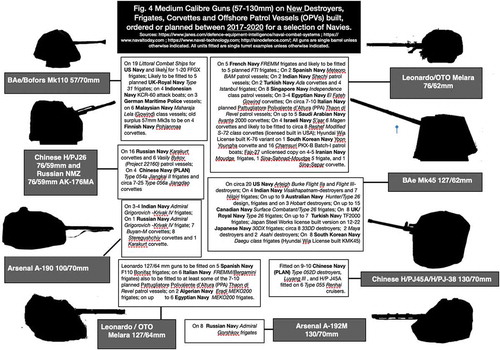

below details the new (for the period 2017–2020+) warship orders for classes of destroyers, frigates and patrol vessels for a selection of navies. All of these are being fitted with medium calibre guns. Indeed, not a single modern naval surface warship in the frigate/destroyer/cruiser category exists in service which does not feature a medium calibre gun.

Figure 4 Medium Calibre Guns (57-130mm) on New Destroyers, Frigates, Corvettes and Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs) built, ordered or planned between 2017-2020 for a selection of navies.Sources: https://www.janes.com/defence-equipment-intelligence/naval-combat-systems ; https://www.navaltoday.com ; https://www.naval-technology.com; http://sinodefence.com/; All guns are single barrel unless otherwise indicated. All units fitted are single turret examples unless otherwise indicated

During the early Cold War, guns were seen as legacy systems destined to be phased out (Friedman Citation1979, 147). In the Soviet Union, Khrushchev favoured missiles over guns and discouraged their further development (Gao Citation2018). The Royal Navy experimented in the 1960s–1970s with ditching medium guns entirelyFootnote9 but reversed this policy after combat experience in the Falklands (1982), where naval gunfire support of land forces proved invaluable (Paget Citation2017). In the end, naval guns were modernised by reducing the weight of turrets and the number of gun barrels, ensuring a higher rate of fire and fewer crew. Digital electronic systems replaced analogue circuits in the 1970s or even later (Friedman Citation2006, 451).

Dual purpose medium calibres were preferred that could be used against aircraft, ships and land targets, although a small number of ships with heavier calibres lasted surprisingly long in service until the end of the 1970s.Footnote10 Exceptionably, the US Navy kept the Second World War era Iowa class battleships in commission, albeit modernised but still with their 16 inch guns.

Distinctive British- and French-designed naval guns (4.5 inch/114 mm and 3.9 inch/100 mm, respectively) also emerged during the early Cold War, however, today their national calibres appear to be coming to an end.Footnote11 The Royal Navy will in future adopt BAe supplied American-style 127-mm guns (Mk45 Mod 4s) and for their new Type 31 frigates, the much lighter 57 mm gun (Mk110), as currently fitted to US Navy Littoral Combat Ships.Footnote12 The French Navy will probably fit Leonardo 76 mm guns on their future frigates and destroyers although as recently as 2016 there was some debate about the need for a heavier 127 mm class weapon.Footnote13

The same controversy erupted when the US Navy chose the BAe 57 mm gun for the Littoral Combat Ship programme (the gun having previously been selected for some US Coastguard vessels), which according to detractors ensured the vessels are badly under-gunned (Hill Citation2012: DePinto, Citation2017; Axe Citation2019). However, smaller 57 mm guns continue to be attractive: Canada has chosen it for some of its most recent vessels as have Indonesia (Rahmat Citation2019).

The global marketplace for naval guns

The retirement of distinctive national calibres reflects the forces of globalisation in the defence sector (Østerud and Haaland Matláry, 2016) with the dominance of a few western gun design firms (BAe and Leonardo). However, these firms are developing old gun models rather than completely new guns. BAe, now a global Anglo-American defence contractor, but originally a British national defence champion, consolidated its position as a naval gun maker in 2005 when they acquired the large American contractor, United Defence,Footnote14 who previously in 2000, had purchased the Swedish Bofors gun company.

BAe guns today date from the 1960 to 70s, but have been continuously updated and enjoy “economies of scale” through being selected by the US Navy and Coastguard. Whatever guns navies select for their ships reflect their wider alliance and geopolitical orientation. The Indian Navy in 2019 selected American made (BAe) 127 mm guns on their newer frigates and destroyers in a deal valued at US$1.021bn (Bedi, 2019). Traditionally, the Indian Navy has used Russian or British weapons, so this choice of American guns appears to signal a shift towards closer co-operation with the USA.

The other globally dominant supplier of naval guns is the Italian naval armaments firm OTO Melara, owned by the Italian defence conglomerate, Leonardo. This company’s 76 mm and 127 mm weapons remain popular, the former more as a constabulary weapon, and the latter as an alternative to the American 127 mm. These designs originate in an Italian 1950s domestic re-armament programme, which standardised on American calibres.

In 2020 alone, both the Spanish Navy confirmed their latest Bonifaz frigate class will use Leonardo 127 mm guns (Manaranche Citation2020), and the Dutch Navy also selected them for four vessels to replace surplus guns that were taken from retired Canadian vessels and sold to the Dutch, revealing an intriguing trade in second hand naval ordnance. Costs matter here, although in the overall scheme of things, considering a price-tag of USD 1–2bn for a US destroyer, the circa 22 million USD cost of their Mk45 gun is rather small (Rogers Citation2016). Nonetheless, purchasing or re-use of surplus guns helps keep the cost of any warship down (Scott Citation2020). Denmark has repurposed old guns on brand new vessels as a cost control strategy and is unique in deploying its Iver Huitfeldt class air defence frigates vessel with two 76 mm turrets.

Russian and Chinese naval gun manufacturers are also active exporters of 76 and 100 mm caliber weapons to countries such as Algeria, Argentina, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Nigeria and Pakistan (Mizokami Citation2015). For the most part, Chinese and Russian gun design have followed the western pattern; single barrel designs, faster firing rates, and greater exploration of precision and guided munitions. However, some Russian destroyers have a notable double barrel 130 mm turret that emerged in mid 1980s and which is regarded as superior to western designs (Gao Citation2018). This weapon is also the ancestor of modern Chinese 130 mm guns.

Naval Gunfire Support-a still relevant mission?

As shows, using ship-guns to support forces ashore remains common, yet at various times for different navies, it has been labelled as obsolete or too risky (Duplessis, Citation2018, 54). Threats of coastal defence or aircraft fired anti-ship missiles are real and will become more challenging with faster, longer range and precise missiles (Biddle and Oelrich Citation2016, fn.30). In the Falklands war (1982) one British vessel was successfully targeted by an improvised shore missile battery and in 2006 an Israeli ship was hit by a Hezbollah anti-ship missile. Missiles have more recently been fired at US and Saudi ships off the coast Yemen by Iranian backed Houthi forces (Cooper, 2016).

However, it is important not to exaggerate this threat as coastal defence missiles systems will usually be suppressed either by preliminary air strikes and electronic warfare. In the past, threats were just as evident from coastal batteries of guns, mines and torpedoes (O’Gorman, Citation2018, 14).

In fact, naval gunfire support has refuted predictions of its demise. For amphibious operations, direct fire support is immediately available and is a relatively simple robust method of suppression. It is partially immune to electronic warfare and jammingFootnote15 and is less impacted by adverse weather that will ground drones or aircraft. As Padget describes: “NGS can be used to replace other forms of fire support and in some instances, may prove to be the only available asset. Land-based artillery, air support, and precision guided munitions have all proved to be unobtainable on occasion during operations, which can lead to a vast increase in the significance of the availability of NGS” (Padget, 2014, 74).

In evidence before the House of Commons in 2004, The Royal Navy’s Admiral West argued that a single 4.5 inch (114 mm) was equivalent to a battery of light artillery guns ashore: “Naval fire support, even of the small stuff we have, 4.5 inch, is very, very useful. It worked really well. We were told in the 70s that we will never use this again, and I think something like 18,000 salvos were fired in the Falklands.”Footnote16 In a briefing on the Libyan intervention, the Royal Navy’s Admiral Sir Mark Stanhope reinforced the importance of naval guns: “Naval fires simply using the 4.5 gun, which some people have suggested was not appropriate in this modern era, was proven again in terms of the ability to put fire on the ground where necessary with some considerable precision.”Footnote17

The American concept of Naval Surface Fire Support (NSFS) envisages the possibility of using missiles and electronic warfare systems as well as guns (Blosser Citation1996), yet in reality what is tried and tested is the volume and duration of gun fire that can be produced by the standard 5 inch/127 mm gun, equivalent to a battery of six field guns (Duplessis, Citation2018, 54).

Nonetheless, there is a growing debate within the US defence community about the efficacy of NSFS given the failure of the Zumwalt class, the retirement of cruiser and destroyer classes that have two gun turrets and a longstanding requirement to considerably increase the range of fire support in the face of what are now formidable Chinese (and Russian) Anti-Access and Area Denial complexes (O’Gorman, Citation2018. 15; DePinto, Citation2017: Paschal, Citation2014). In truth, US naval fire support is down to rather austere destroyers with usually just a single 5 inch/127 mm gun firing standard ammunition to ranges of not more than 24 km. In a historical context, a report assessing US naval gun support noted: “The Navy could generate nothing like the NSFS capability and capacity that it used to support landings of the size or type carried out during World War II, which included the ability to attack hardened bunkers and provide sustained suppressive fires” (Bradley et al. Citation2020, 49).

Guns as naval fire support platforms are also facing some competition from missiles and rockets. The Israel Navy complements their 76 mm guns with smaller guided missiles to support land forces ashore.Footnote18 The German Navy have modified Swedish manufactured RBS15 anti-ship missile on their corvettes so that they can be fired against land targets up to 200 km (Naval Today Citation2016). The US Navy has had Tomahawk cruise missiles since the mid-1980s, and is modifying existing ship-based missiles for land strike missions or fielding new missiles that will have land attack capabilities (Canican Citation2019).

The Russian, Indian and Chinese navies also have rocket artillery systems on their amphibious ships (Friedman Citation2006, 491–499), whereas the US has only conducted some experiments with firing MLRS/HIMARSFootnote19 rockets from the deck of an amphibious landing ship. Considering that HIMARS rockets can range as far as 160 km, this could be a promising future fire support option, but a naval version of that weapon is not being procured (O’Gorman, Citation2018: DePinto, Citation2017). In any event, missiles and rockets cannot provide a continuous volume of fire or they typically do not have the capability to deliver sustained bombardment, that is, over hours.

Instead, US amphibious forces, and those of China will rely on a range of weapons and platforms to provide them with fire support, and in many cases this will be from aircraft and missiles. However, in the mix will be escorting destroyers and frigates with their old-fashioned medium calibre guns. They will feature simply because of their ubiquity.

Of course, much turns on how important amphibious operations could be in a Sino-American war. For any invasion of Taiwan, Chinese amphibious means and their denial would be central. The Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands form another flashpoint that could draw in the USA given treaty obligations. A clash in the South China Sea could well pivot around physical occupation of very small islands, atolls and rocks. For these last two scenarios what might be required would be more analogous to amphibious raiding by either side, something which is actually part of US doctrineFootnote20 (JCOS, 2019, II-1-II-4).

Evolving US amphibious operational concepts are emphasising smaller formations (DePinto, Citation2017), such as Marine Littoral Regiments, which also may be deployed in units as small as reinforced platoons (McLeary Citation2020: Snow Citation2020). For such smaller units the general purpose destroyer armed with medium calibre guns will be the most likely available support asset, especially if aircraft carriers and aerial assets are forced to disperse because of higher level threats.

Naval guns for hybrid warfare at sea

For commonplace, but essentially limited use-of-force incidents at sea, naval guns offer a scalable level of force, including warning shots. They are also an alternative to using air power where such would be escalatory or risk valuable air crew. This appears to be one rationale why the World War 2 era battleship USS New Jersey, was used in 1984 to bombard armed factions around Beirut (Atkinson, Citation1984).

China augments its regular navy and coastguard with an “auxiliary fleet” of trawlers, merchantmen and scientific research ships, sometimes described as a “maritime militia” (Kraska Citation2020). Such forces are ideal for hybrid war at sea, or “asymmetric warfare” (Schaub et al. Citation2017; Patalano Citation2018; Thornton Citation2007, 102–125). China may prefer such tactics to the risks and costs of full-spectrum inter-state warfare.

There have been numerous examples of maritime hybrid armed clashes in the wider Indo-Pacific theatre. In 1999, 2002 again in 2009 South Korea’s Navy faced a number of naval incidents with North Korean vessels where guns featured extensively (Van Dyke et al. Citation2003, 143). China’s naval forces have used ramming and occasionally, cannon and heavier guns against Vietnamese and Philippine fishing vessels (Gomez Citation2020). In 1996, a 90 minute gun battle between PLAN and Philippine Navy ships broke out near Mischief reef in the Spratly islands (CFR, Citation2020). There is a long history of clashes with Vietnam over the Spratly Islands (Yoshihara Citation2016; CFR, Citation2020), and in 2020, clashes between Chinese vessels and Indonesian forces occurred around the Natuna Islands.

These cases should be instructive as regards the nature of naval warfare in the wider Pacific. Given the USA’s commitment to Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) (Kraska and Pedrozo Citation2018) it seems that one of the most plausible ways that US and Chinese naval forces will employ force against each other is via a limited engagement at sea, rather than all-out war. The old naval practice of using a gun firing a warning “shot across the bows” is not anachronistic here as such a visual spectacle works just a well in the era of near instantaneous livestreaming via social media.

However, winning or losing such hybrid contests at sea may well not merely be a question of perception. Physical domination will be central through aggressive tactics that include ramming of vessels, or less lethal weapons such as water cannon, as might be using naval guns, to warn, intimidate and even reply to force in a proportionate manner with disabling shots. High-tech weaponry is not of much use in these type of situations, and missiles are not readily usable in this way.Footnote21

Unlike the smaller calibre cannon or machine guns, medium naval guns have stopping power when faced with larger vessels, as smaller cannons have sometimes proven insufficient to stop larger vesselsFootnote22 (Allen, Citation2006, 104–105). It seems to stop larger vessels (over 3,000 tonnes displacement) guns of about 5 inch (127 mm) are required whereas the smaller calibre 76 mm and 57 mm designs are less likely to be effective (Hill Citation2011).

Medium calibre guns can also be used to fire disabling shots at rudders and other essential infrastructure and this type of employment is governed by special provisions for the US Coastguard, which allow disabling fire to be used without warning shots if required (Kim Citation2020, 168–169; Allen, Citation2006, Op. Cit.). The US Coastguard has recently joined the US Navy in freedom of navigation operations, notably in the Taiwan strait in 2019 (Ali Citation2019).

Moreover, guns can be readily resupplied at sea and most ships carry a significant store of ammunition anyway.Footnote23 This is important in situations where maritime stand-offs are long-lasting and what is required is presence through endurance. The 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff between the Philippines and China lasted roughly two months, and in 2019 Chinese naval and coastguard vessels spent four months inside the Vietnamese Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), testing Vietnamese sovereignty over economic resources by attrition. In May 2020, there was another six-month standoff between Vietnam, Malaysia and China in the South China Sea (CFR, Citation2020).

What future for medium calibre guns?

Medium calibre guns remain a staple of surface warfare because they have been modernised and are in effect hybrid weapon systems, combining old and new technologies. For example in the 1990s, most manufacturers offered variants with new turrets with stealth features (Friedman Citation2006, 456, 472, 480).

Downsizing calibres

One trend evident today is the adoption of smaller calibres, notably the 57 mm type, which are not suited for naval gunfire support as their munitions have too little effect on land targets and require the ships to be really close to shore. Navies that adopt smaller calibre guns may in future give up on using guns to bombard ashore but they are unlikely to give up on guns for other roles.

The 57 mm and the 76 mm guns have capabilities against fast boats, drones and missiles especially if combined with advanced ammunition and fire control.Footnote24 These guns may overlap with the lighter Close in Weapon Systems (CIWS) which emerged in the 1970–80s to provide a last ditch stop-gap against fast missiles, but today probably lack sufficient range or destructive abilities against future missiles. The Italian OTO Melara 76 mm has been marketed as a long-range CIWS system (Freidman, 2006, 458) and Russian designs show 57 mm guns replacing existing 30 mm CIWS designs (Novichkov Citation2020).

Upscaling calibres

An alternative trajectory would involve scaling upwards to heavier 155 mm guns, sharing common ammunition with land armies, giving longer range and the possibility of using already developed precision and guided munitions.

BAe developed such a design for the Royal Navy, but it was axed around 2010 as part of wider cost savings.Footnote25 The Germany Navy trialled a modified 155 mm army gun in 2005; however, this was declared unsuccessful because of issues with recoil and corrosion resistance (Friedman Citation2006, 453). French firm GIAT had also a design study for a 155 mm naval weapon and at least one Russian design bureau has proposed a double-barrelled 152 mm naval weapon (Williams Citation2011). Yet it appears no navy is seriously considering deploying 155 mm naval guns. The hubristic experience of the US Navy’s Zumwalt class ships is a salutary example. With competing demands for funding, bigger and more expensive naval guns are unlikely to be a priority.

Drone Monitors

One futuristic solution to the naval gunfire support role could be “drone vessels” (Rowlands Citation2019) and indeed a recent study by RAND mentions a role for “unmanned fire support platforms” (Bradley et al. Citation2020, xi). These might follow the old idea of a “monitor” (Wasielewski, Citation2000) or employ landing-craft carrying rocket artillery systems, deploying from amphibious “mother-ships”. Ensuring their reliability if truly unmanned would raise issues of cost and complexity and current US naval plans for unmanned vessels focus only on mine-warfare, anti-submarine and other missions (Dunn Citation2020).

Smarter shells

Since the 1980s, there has been ongoing development of guided naval shells. How effective and commonplace such precision munitions are in service remains unclear, and in most recent naval engagements older “dumb” munitions have been used, but with much greater precision using advanced fire control.

Moreover, the US Navy has struggled to field precision and longer range munitions. Bloomer (1996) detailed how a 63 nautical mile extended range guided munition (ERGM) was supposed to enter into US Navy service in 2000, using GPS and inertial navigation technologies. Friedman (Citation2006, 485) also described details of another project (BTERM) which offered a cheaper guided shell with ranges of 50 km. Neither ever materialised. The ERGM programme was cut in 2008 after inconclusive testing as regards its reliability. The US Army by way of comparison have fielded laser guided 155 mm shells (M712 Copperhead) since the mid 1980s and GPS guided 155 mm shells (M982 Excalibur) from 2005. Both have seen combat use.

The US Navy as of 2020 were trialing a 127 mm calibre version of the “Excalibur” projectile which blends GPS and laser guidance (Allison Citation2020). The Italian firm Leonardo has also been exploring for some time, in co-operation with other companies,Footnote26 extended range and guided projectiles for their 76 mm and 127 mm guns and this includes giving the projectiles precision guided capabilities using infrared or laser technologies (Friedman Citation2006, 457). In this guise, the projectile is a hybrid between an artillery shell and a guided missile (Friedman Citation2006, 458, 485). The German Navy has conducted trial shots of Leonardo’s Vulcano 127 mm ammunition which promises ranges in excess of 80 km combined with a high rate of fire (Naval Today, 2017).

Such munitions seem today reliable enough to emerge in the near future, although this has been promised before (Friedman Citation2006, 485), and it is unclear in what numbers they will be procured. In theory, they help surface warships make better use of existing medium calibre guns by conferring precision, greater range and therefore the ability to stay further offshore from coastal threats.

Disruptive futures- laser and rail-guns

Finally, there remains ongoing speculation that futuristic laser weapons and especially electro-magnetic rail guns will replace naval guns. Laser weapons are being deployed on some US destroyers but not to replace medium calibre guns. Instead, they are optimised for near defence against small boats, drones and missiles, and may replace existing CIWS systems or just augment them. The Royal Navy is also deploying a 50 kw laser weapon system called DragonFire, but has no plans to replace naval guns with such a system (RN, 2019; Allison Citation2019).

Laser weapons are ideal for quickly targeting and destroying many small targets but they cannot deliver large volumes of explosive on a target for long periods of time. For these reasons, they are unlikely to replace the naval gunfire support mission, although they have utility for constabulary roles as dazzlers and precision disabling fire of vessel sensors. In fact the main and ubiquitous use of lasers has been for guidance and fire control (Friedman Citation2006, xxvi-xxxii) and attempts to develop laser weapons have been tortuous (Hecht Citation2019, 221).

The promise of electro-magnetic rail guns has been touted for some time with one authority suggesting they could be in service by 2015 (Friedman Citation2006, 484) or that they would be a “true game-changing technology” (O’Gorman, Citation2018, 15). However, rail gun technology appears to be fundamentally immature and requires substantial further investment and time (O’Rourke/CRS, 2020b, 19–22). Prototypes have been deployed by the US Navy which have demonstrated long ranges but only a few shots per hour, compared with 20 rounds per minute for their existing 5 inch/127 mm gun (RAND/Martin, 2020, 53). China appears to have deployed some type of rail gun prototype but this may also be a propaganda stunt (Tangredi Citation2019, 11).

In fact there is increasing attention on so-called hyper velocity projectiles (HVPs), which unlike rail guns can be fired from existing barrels. This type of projectile is not new given that in 2000 there was a proposed “Barrage” shell that would have been hypersonic (Friedman Citation2006, 485). The advantage of staying with existing proven guns should be obvious. The latest hypervelocity projectile, known as the GLGP (Gun Launched Guided Projectile), travels at Mach 3 to achieve ranges of 40+ nautical miles (Bradley et al. Citation2020, 53). This could be enough to give existing guns in service an increased capability that keeps them useful.

Conclusions

While navies are less interested in their legacy gun systems than they are in fashionable high-tech weapons, medium calibre guns remain in service and continue to be fitted to the vast majority of surface warfare vessels. Moreover, most navies continue to be interested in modernising their guns to get longer range and precision. Admittedly, the naval gunfire support mission may be quietly undergoing a slow death if we consider stalled progress on electro-magnetic rail guns, and above all a shift to much lighter and smaller calibre (57 mm) guns. Yet it is surely a salutary observation that the business of selling naval guns is booming. No significant surface warships of any navy are being ordered without them, and new ships with medium calibre guns in the 127–130 mm calibre are commonplace.

The concept of technological hybridity discussed here is also of wider significance for our understanding of contemporary warfare, and more generally as a corrective against the still excessive importance assigned to high technology in war. Modernising existing weapons can provide alternatives to an over dependency on very high technology weapon systems, for example by allowing existing ship guns to fire high velocity projectiles at much greater ranges and speeds.

As regards technology then, contemporary naval warfare is better understood as neither a high-tech computer wargame played out at sea, nor the opposite, tradition bound admirals clinging to out of date vessels and weapons. The point here is not to deny that high technology will surely matter in any future naval clash between the China and America. Rather, the argument here is that its role may not be as central nor as clear-cut as regards what technologies turn out to be effective or those that have to be relied upon. We can expect combinations of old and new weapons, varied tactics and operational concepts, together with some spectacular high-tech wizardry leavened by more mundane low-tech systems, whose combined overall effectiveness can only be guessed at. Much will depend on how complex technologies are employed by either side.

It is also important to qualify the claims made here. The examples in are obviously limited to just two ship classes (although they are among the most numerous modern types for each country’s surface fleet). Given that navies employ submarines, aircraft and land-based weapons, there are certainly some entirely novel weapons being deployed. China’s land-based ballistic anti-ship missiles are one example and the US Navy is acquiring some entirely new weapons as well.Footnote27 Moreover, considering the pace of change in computing power and digital technologies, rapid evolution has been much more pronounced as regards sensors and electronics compared with weapons.

However, the argument here is that medium calibre naval guns have persisted because they have evolved through “hybrid” technology pathways to remain surprisingly viable. In the first instance they provide niche tactical level capabilities by giving naval gunfire support in amphibious operations, or to provide close range fires for asymmetric operations at sea (against pirates or irregular forces). However, naval guns have also operational and strategic effects. They provide logistical redundancy because missiles are more expensive and may be depleted, or they are available when “smart” weapons are degraded by electronic warfare. At the strategic level, guns allow navies to use proportionate force: from warning shots, to crippling fires, all the way up to sustained bombardments. The diplomatic effect of the shot across the bows is not to be easily discounted. Carrier aircraft in general lack such nuance, other than to fire warning shots with cannon, and missiles can rarely if ever be used to “warn, scare, and stop” another vessel at sea.

As long as medium calibre naval guns can continue to integrate ongoing developments in fire control and precision guidance, they are likely to have some future as armament for naval vessels. It is possible some navies may decide to merge the existing CIWS category of weapon with a smaller calibre medium gun, such as the 57 mm and 76 mm types. Yet because almost no surface warfare vessels being built today are without a gun of some sort, and indeed many continue to be built with heavier calibre guns, navies will continue to employ naval guns for the near future and quite possibly well beyond.

Moreover, given the likely importance of amphibious and/or hybrid-type operations in any future Sino-American clash, it is almost certain such guns will feature by virtue of their ubiquity and endurance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Brendan Flynn

Dr. Brendan Flynn is a lecturer at the School of Political Science and Sociology, NUI, Galway. His research interests include maritime security and defence and security studies more broadly.

Notes

1. The simplest definition of these is “maneuvering weapons that fly at speeds of at least Mach 5” (SaylerRS, 2020, 2)

2. These can be defined as a launcher “that uses electricity rather than chemical propellants (i.e., gunpowder charges) to fire a projectile” (O’Rourke/CRS, 2020, 21, fn.42).

3. People’s Liberation Army

4. This terms relates to “realistic photo, audio, video, and other forgeries generated with artificial intelligence (AI) technologies” (Sayler and Harris/CRS, 2019, 1).

5. Chief of Naval Operations. Zummwalt was CNO from 1970 to 1974.

6. Naval mine warfare, for example, is characterized by ongoing high-tech improvements in fuzes and electronics alongside the fact that many very old mine types and warheads remain in global service and some of these continue to employ older forms of triggering whose origins are in the World Wars, because they are cheaper and easier to maintain (Friedman Citation2006, 773–774).

7. Calibre means the width of the inner-barrel and therefore also the projectile. It is measured in inches or millimetres. Calibre is often further described more precisely by reference to the overall length of the projectile, including the shell casing. For example, the Russian and Chinese 76 mm/60 is a different gun and shell from the Italian/western 76 mm/62. The Italian shell is longer here, the 62 indicating it is 62 times as long as it’s width in mm. For further information see: http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/Gun_Data.php

8. These are my estimates from various open sources.

9. Some Royal Navy’s Leander class frigates (designed 1950s) had their 4.5 inch gun turret removed and replaced by missiles, although a few were kept with their guns. The Broadsword class (designed 1970s) were originally conceived without any gun turret. However, the Batch 3 of this class were redesigned in the 1980s to take a 114 mm gun turret.

10. The US Navy kept a number of Baltimore and Des Moines class cruisers armed with nine 8 inch (203 mm) guns in service until the mid 1970s. The Royal Navy kept modernized helicopter cruisers HMS Tiger and HMS Blake in service until 1978–79, each carrying World War 2 era 6 inch (152 mm) guns, while the Dutch Navy kept De Zeven Provinciën, with 6 inch guns, in operation till the mid 1970s. The Soviet Navy’s Sverdlov cruisers with a dozen 6 inch guns remained in service probably into the 1980s. The Argentine Navy’s Belgrano cruiser which was sunk by a Royal Navy submarine in 1982 was equipped with 6 inch guns.

11. British 4.5 inch naval ammunition used to be produced at the Royal Ordnance Factory, Birtley/Gateshead, as far back as the First World War. BAE systems in 2012 built a new factory at Washington nearby, which can produce a range of munitions.

12. More details of the Royal Navy’s Type 31 frigate emerge”, September 15th, 2019https://www.savetheroyalnavy.org/more-details-of-the-royal-navys-type-31-frigate-emerge/

13. “French Navy FTI Frigate: From 57 mm to 127 mm, Naval Gun System Choice Still Open”, 28 October 2016,https://www.navyrecognition.com/index.php/news/naval-exhibitions/2016/euronaval-2016/4535-french-navy-fti-frigate-from-57mm-to-127mm-naval-gun-system-choice-still-open.html

14. United Defence emerged from the FMC corporation in the mid 1990s, which itself had acquired Northern Ordnance in 1964. Northern Ordnance were originally founded in 1940 as a division of the Northern Pump Company, producing 5 inch guns at a site on the upper Mississippi river (Frindley, Minnesota). BAe continues to conduct research and development at this site but naval gun manufacturing has mostly shifted to Louisville (Kentucky).

15. The various fire control technologies used to support modern naval guns are not immune to electronic warfare, but the basic guns and munitions themselves are impossible to jam or spoof unlike radar or infra-red guided missiles.

16. House of Commons, Minutes Of Evidence, Taken Before Defence Committee, “Future Capabilities”, Wednesday 24 November 2004, Admiral Sir Alan West GCB DSC ADC,https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200405/cmselect/cmdfence/uc45-i/uc4502.htm

17. Testimony by Admiral Sir Mark Stanthorpe, at 118, House of Commons, Defence Committee, Ninth Report-Operations in Libya, 25 January 2012, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/950/95007.html

18. These are probably Non-Line of Site “Tamuz” Spike missiles which could have a range of 25 km, but the Israeli’s also have much bigger and longer-range missiles, in calibres of 160 mn and 300 mm with ranges between 50–150 km. It is unclear whether these are deployed on Israeli vessels. The US Navy have added Hellfire missiles to their Littoral Combat Ships.

19. MLRS is an American Multiple Launch Rocket System, 227 mm calibre, developed at the end of the Cold War. The High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) is a 1990s development of MLRS using a wheeled vehicle and capable of firing fewer, but longer range, rockets.

20. Interestingly, this doctrine statement details that “on-call fire support should also be planned to support the amphibious raid force if it is detected en route and requires assistance to break contact, conduct an emergency withdrawal, or continue to the objective” (JSOC, 2019, Ibid).

21. Missile control radars can be used to warn and threaten another warship or aircraft by illuminating them with fire control radars or lasers. However, it is not as tangible as “shots across the bow”.

22. Allen (Citation2006) provides the example of the failed US Coastguard interception of Panamanian registered MV Hermann in 1990, which refused to stop despite machine gun and light cannon fire. The ship escaped.

23. A typical US Navy Arleigh Burke destroyer carries circa 600 × 127 mm munitions (Bradley et al. Citation2020, 11).

24. Smart munitions in 57 mm calibre include the ALaMO round optimised to destroy small fast boat threats and the so-called MAD-FIRES 57 mm guided munition to intercept missiles. See: https://chuckhillscgblog.net/2019/11/14/guided-rounds-for-the-57mm-mk110-alamo-and-mad-fires-an-update/. BAe have also developed a 57 mm smart round called the ORKA. See: http://www.navyrecognition.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3465)

25. See: NavWeapons, 155 mm (6.1”) Future Naval Gun and Alternativeshttp://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_61-52_future.php

26. Leonardo have been working on advanced munitions for at least two decades. Collaboration is with the German firm Diehl and BAe (Naval Technology Citation2017).

27. Naval Strike Missiles (of Norwegian origin) will be fitted to Littoral Combat Ships giving them an ability to hit ships and fixed land targets at ranges of 100 km. There are several unmanned surface and sub-surface vessels programmes for the US Navy, see: Hoehn and Ryder/CRS (2020) and O’Rourke (2020).

References

- ADF/Australian Defence Force. 2019. Future Maritime Operating Concept - 2025 Maritime Force Projection and Control. Unclassified Version ed. Canberra: DoD. https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/FMOC_2025_Unclassified.pdf

- Ali, I. 2019. “U.S. Navy, Coast Guard Ships Pass through Strategic Taiwan Strait” Reuters, March 24th. Accessed 16th December 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-taiwan-military/u-s-navy-coast-guard-ships-pass-through-strategic-taiwan-strait-idUSKCN1R50ZB

- Allen, C. 2006. “Limits on the Use of Force in Maritime Operations in Support of WMD Counter Proliferation Initiatives.” International Law Challenges: Homeland Security and Combating Terrorism. International Law Studies. Vol. 81. edited by. Sulmasy, G. M. 77–139. Newport, RI: Naval War College.. https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=35194

- Allison, G. 2019. “UK Tests Warship Power Systems for Dragonfire Laser Weapon.” UK Defence Journal. https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/uk-tests-warship-power-systems-for-dragonfire-laser-weapon

- Allison, G. 2020. “Laser-guided Excalibur S Munition Passes US Navy Test.” UK Defence Journal. https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/laser-guided-excalibur-s-munition-passes-us-navy-test

- Atkinson, R. 1984. “Pentagon Keeps Details on Shelling Secret.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1984/02/18/pentagon-keeps-details-on-shelling-secret/e1e5d080-cfeb-4bfd-8d1a-8e1cf9dc422f/

- Axe, D. (2019) “Why the Navy’s Littoral Combat Ships are so Terrible.” The National Interest, October 21st. Accessed 16th December 2020. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/why-navys-littoral-combat-ships-are-so-terrible-90066

- Bekkers, F., P. Bolder, E. Chavannes, W. Oosterveld, D. W. Rob, and J. F. Braun. 2019. Geopolitics and Maritime Security: A Broad Perspective on the Future Capability Portfolio of the Royal Netherlands Navy. The Hague: Centre for Strategic Studies.

- Biddle, S., and I. Oelrich. 2016. “Future Warfare in the Western Pacific: Chinese Antiaccess/Area Denial, U.S. AirSea Battle, and Command of the Commons in East Asia.” International Security 41 (1): 7–48. doi:10.1162/ISEC_a_00249.

- Bitzinger, R. A. 2018. “The Myth of the ‘Game-changer’ Weapon.” RSIS Commentary No.91, 31st May. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/CO18091.pdf

- Black, J. 2013. War and Technology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Blasko, D. J. 2011. ““Technology Determines Tactics: The Relationship between Technology and Doctrine in Chinese Military Thinking.”.” Journal of Strategic Studies 34 (3): 355–381. doi:10.1080/01402390.2011.574979.

- Blosser, K. O. 1996. “Naval Surface Fires and the Land Battle.” Field Artillery Journal 41–45. https://fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/ship/weaps/docs/tart3prnt.html

- Bourne, M. 2012. “Small Arms and Light Weapons Spread and Conflict.” In Small Arms, Crime and Conflict: Global Governance and the Threat of Armed Violence, edited by Greene, O. and N. Marsh, 29–41. London: Routledge.

- Bradley,, B. Clayton, J. Welch, S. J. Bae, Y. Kim, I. Khan, and N. Edenfield, RAND/Martin. 2020. Naval Surface Fire Support an Assessment of Requirements. Santa Monica, CA: RAND. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4351.html

- Brose, C. 2020. The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare. New York: Hachette.

- Canican, M. F. 2019. “Report-U.S. Military Forces in FY 2020.” October 3rd. Washington, D.C.: CSIS/Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/191119_Cancian_FY2020_Navy_FINAL.pdf

- CFR/Council on Foreign Relations. 2020. “China’s Maritime Disputes 1895-2020.” Accessed 16th December 2020. https://www.cfr.org/timeline/chinas-maritime-disputes

- Cronin, P.M., and R.Neuhard. 2020. Total Competition China’s Challenge in the South China Sea. Washington, D.C.: Center for a New American Security. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/total-competition

- Defoe, A. 2015. “On Technological Determinism: A Typology, Scope Conditions, and A Mechanism.” Science, Technology & Human Values 40 (6): 1047–1076. doi:10.1177/0162243915579283.

- DePinto, V. J. (Captain, USMC). 2017. “Capability Analysis-For Want Of A Broadside: Why The Marines Need More Naval Fire Support.” Blog post March 20th, Center for International Maritime Security. Accessed 16th December 2020. http://cimsec.org/want-broadside-marines-need-naval-fire-support/31347

- DIA/Defence Intelligence Agency. 2019. China Military Power: Modernizing a Force to Fight to Win. Washington, D.C.: DIA. https://www.dia.mil/Portals/27/Documents/News/Military%20Power%20Publications/China_Military_Power_FINAL_5MB_20190103.pdf

- Dunn, B. 2020. “The Future for Unmanned Surface Vessels in the US Navy,” Georgetown Security Studies Review, October 28th. https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/2020/10/28/the-future-for-unmanned-surface-vessels-in-the-us-navy/

- Duplessis, B., (Col., U.S.M.C.). 2018. “Thunder from the Sea: Naval Surface Fire Support.” Fires. A Joint Publication for US Artillery Professionals. May-June. No. PB-644-18-3: 49–55, https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/1072637.pdf

- Edgerton, D. 2006. The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History since 1900. London: Profile Books.

- Elhefnawy, N. 2019. “The Military Techno-Thriller: A History.” Kindle Direct.

- Engstrom, J. 2018. Systems Confrontation and System Destruction Warfare: How the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Seeks to Wage Modern Warfare. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1708.html

- Fredenburg, M. 2016. “How the Navy’s Zumwalt-Class Destroyers Ran Aground,” National Review, December 19th. https://www.nationalreview.com/2016/12/zumwalt-class-navy-stealth-destroyer-program-failure/

- Friedman, N. 1979. Modern Warship Design and Development. London: Conway.

- Friedman, N. 2006. The Naval Institute Guide to World Naval Weapon Systems. 5th ed. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

- Gagliano, J. A. 2019. Alliance Decision-Making in the South China Sea: Between Allied and Alone. London: Routledge.

- Gao, C. 2018. “Russia’s Massive Naval ‘Cannon’ Could Crush a Navy Destroyer in Battle.” The National Interest, April 11th. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/russias-massive-naval-cannon-could-crush-navy-destroyer-25329

- Gomez, J. 2020. “Philippines Backs Vietnam after China Sinks Fishing Boat.” ABC News, 8th April. Accessed 16th December 2020. https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/philippines-backs-vietnam-china-sinks-fishing-boat-70037606

- Gray, C. S. 1993. Weapons Don’t Make War: Policy, Strategy, and Military Technology. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

- Hacker, B. C. 2005. “The Machines of War: Western Military Technology 1850–2000.” History and Technology 21 (3): 255–300. doi:10.1080/07341510500198669.

- Handel, M. 1981. “Numbers Do Count: The Question of Quality versus Quantity.” Journal of Strategic Studies 4 (3): 225–260. doi:10.1080/01402398108437082.

- Hecht, J. 2019. Lasers, Death Rays and the Long, Strange Quest for the Ultimate Weapon. NY: Prometheus.

- Heginbotham, E., F. E. Michael Nixon, J. L. Morgan, J. H. Heim, S. T. Li, M. C. L. Jeffrey Engstrom, P. DeLuca, et al. 2015. “The U.S.-China Military Scorecard, Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power, 1996-2017.” RAND report RR-392. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR392.html

- Hicks, K. H., J. Federici, L. R. S. Aysa Akca, F. Alice Hunt, and S. Hijab. 2019. By Other Means, Part 1: Campaigning in the Gray Zone. International Security Program Report. New York: CSIS/Rowman and Littlefield. https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/Hicks_GrayZone_interior_v4_FULL_WEB_0.pdf

- Hill, C. 2011. “What Does It Take to Sink a Ship?” Chuck Hill’s Blog, March 14th. Accessed 16th December 2020. https://chuckhillscgblog.net/2011/03/14/what-does-it-take-to-sink-a-ship/

- Hill, C. 2012. “Case for the Five Inch Gun.” Chuck Hill’s Blog, November 19th. Accessed 16th December 2020. https://chuckhillscgblog.net/2012/11/19/case-for-the-five-inch-gun/

- Hoehn, J. R., and D.S. Ryder/CRS. 2020. Precision-Guided Munitions: Background and Issues for Congress Updated 26 June 2020. R45996… . . Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov

- JCOS/Joint Chiefs of Staff. 2019. “Joint Publication 3-02.” Amphibious Operations. 4th January. Washington, D.C.: DoD. https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_02.pdf

- Johnson, J. S. 2017. “China’s “Guam Express” and “Carrier Killers”: The Anti-ship Asymmetric Challenge to the U.S. In the Western Pacific.” Comparative Strategy 36 (4): 319–332. doi:10.1080/01495933.2017.1361204.

- Dunlap, C.J.. 2010. How We Lost the High-Tech War of 2020: A Warning from the Future. Stafford VA: Small Wars Foundation.

- Kaplan, R. D. 2010. “The Geography of Chinese Power: How Far Can Beijing Reach on Land and at Sea?” Foreign Affairs 89 (3): 22–41. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25680913

- Kim, S. K. 2020. Coast Guards and International Maritime Law Enforcement. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Kirchberger, S. 2015. Assessing China’s Naval Power—Technological Innovation, Economic Constraints, and Strategic Implications. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Kraska, J. 2020. “China’s Maritime Militia Vessels May Be Military Objectives During Armed Conflict.” The Diplomat, July 7th. https://thediplomat.com/2020/07/chinas-maritime-militia-vessels-may-be-military-objectives-during-armed-conflict/

- Kraska, J., and R. Pedrozo. 2018. The Free Sea: The American Fight for Freedom of Navigation. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

- Lake, D. R. 2019. The Pursuit of Technological Superiority and the Shrinking American Military. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Mahnken, T. G. 2008. Technology and the American Way of War since 1945. New York: Columbia Press.

- Manaranche, M. 2020. “Leonardo Confirms Selection of Its 127mm Naval Gun for Spain’s F-110 Bonifaz-Class Frigates.” NavalNews, May 27th. https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2020/05/leonardo-confirms-selection-of-its-127mm-naval-gun-for-spains-f-110-bonifaz-class-frigates/

- Martinson, R. D., and A. S. Erickson. 2019. “Conclusion. Options for the Definitive Use of US Sea Power in the Grey Zone.” In China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations, edited by Erickson, A. S. and R. D. Martinson, 291–301. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

- McLeary, P. 2020. “Marine Corps Builds New Littoral Regiment, Eye on Fake Chinese Islands.” BreakingDefense, September 22nd. https://breakingdefense.com/2020/09/marine-corps-builds-new-littoral-regiment-eye-on-fake-chinese-islands/?utm_campaign=Breaking%20News&utm_medium=email&_hsmi=95848453&utm_content=95848453&utm_source=hs_email

- Mizokami, K. 2015. “A Look at China’s Growing International Arms Trade.” USNI News, May 7th. https://news.usni.org/2015/05/07/a-look-at-chinas-growing-international-arms-trade

- Mizokami, K. 2016. “The USS Zumwalt Can’t Fire Its Guns because the Ammo Is Too Expensive.” Popular Mechanics, November 7th. Accessed 16th December 2020. https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/navy-ships/a23738/uss-zumwalt-ammo-too-expensive/

- MoD/Ministry of Defence (UK). 2018. Global Strategic Trends: The Future Starts Today. 6th ed. London: MoD. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/771309/Global_Strategic_Trends_-_The_Future_Starts_Today.pdf

- Novichkov, N. 2020. “Russian Ship Designers Show Latest Advanced Naval Platforms.” Jane’s Navy International, January 20th. https://www.janes.com/article/93806/russian-ship-designers-show-latest-advanced-naval-platforms

- O’Gorman, J. M. (Lt. Col.) 2018. “NSFS in a Contested Environment.” Marine Corps Gazette, December: 14–16. https://mca-marines.org/wp-content/uploads/NSFS-in-a-Contested-Environment.pdf

- Østerud, Ø., and J. HaalandMatláry. 2016. Denationalisation of Defence: Convergence and Diversity. London: Routledge.

- O’Rourke, R./CRS. 2020. “Navy Large Unmanned Surface and Undersea Vehicles: Background and Issues for Congress,” Updated 10 November 2020. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.govR45757

- O’Rourke, R./CRS. 2020b. Navy Lasers, Railgun, and Gun-Launched Guided Projectile: Background and Issues for Congress. updated. April 2nd. R44175. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/6827049/Navy-Lasers-Railgun-and-Gun-Launched-Guided.pdf

- O’Rourke, R./CRS. 2020a. Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress, RL32109. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. 8 June 2020 Updated https://fas.org/sgp/crs/weapons/RL32109.pdf

- Paget, S. 2014. “Old but Gold: The Continued Relevance of Naval Gunfire Support for the Royal Australian Navy.” Security Challenges 10 (3): 73–94. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26465446

- Paget, S. 2017. “Under Fire: The Falklands War and the Revival of Naval Gunfire Support.” War in History 24 (2): 217–235. doi:10.1177/0968344515603744.

- Paschal, S. 2014. “Return of the Gun Line.” Proceedings, 140( 8),August. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2014/august/return-gun-line

- Patalano, A. 2018. “When Strategy Is ‘Hybrid’ and Not ‘Grey’: Reviewing Chinese Military and Constabulary Coercion at Sea.” The Pacific Review 31 (6): 811–839. doi:10.1080/09512748.2018.1513546.

- Rahmat, R. 2019. “Indonesia Selects BAE Systems 57 Mm Naval Gun for Four KCR-60M-class Vessels”, Jane’s Navy International, August 23rd. https://www.janes.com/article/90626/indonesia-selects-bae-systems-57-mm-naval-gun-for-four-kcr-60m-class-vessels

- Rahul, B. 2019. “US Approves Sale of 13 Mk 45 Naval Guns to Indian Navy.” Janes Defence Weekly. https://www.janes.com/article/92754/us-approves-sale-of-13-mk-45-naval-guns-to-indian-navy

- Raleigh, H. 2019. “Wolf Warrior II Tells Us a Lot about China”. The National Interest, July 20th. https://www.nationalreview.com/2019/07/wolf-warrior-ii-tells-us-a-lot-about-china/

- Raudzens, G. 1990. “War-Winning Weapons: The Measurement of Technological Determinism in Military.” The Journal of Military History 54 (4): 403–434. doi:10.2307/1986064.

- RN/Royal Navy. 2019. “Mod £130m Investment into Lasers,” July 10th. Accessed 16th December 2020. https://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/news-and-latest-activity/news/2019/july/10/190710-mod-130m-lasers

- Rogers, D. L. 2016. “Keeping Naval Guns Ready.” Defence AT&L, March-April: 21–24. https://www.dau.edu/library/defense-atl/DATLFiles/Mar-Apr2016/Rogers.pdf

- Roland, A. 2016. War and Technology: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: OUP.

- Rowlands, G. 2019. “Battleship Redux: An Ironclads Inflection & ‘Dronenaught’ Class Warships.” Groundedcuriosity.comblog Accessed 16th December 2020. https://groundedcuriosity.com/battleship-redux-an-ironclads-inflection-dronenaught-class-warships/#.X6KPuS-l2fU

- Sayler, K. M./CRS. 2020. “Hypersonic Weapons: Background and Issues for Congress.” Report 45811, March 17th. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/weapons/R45811.pdf

- Sayler, K. M., and A. L. Harris/CRS. 2019. Deep Fakes and National Security, Congressional Research Service in Focus Series. October 14th. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11333

- Schaub, G., M. Murphy, and F. G. Hoffman. 2017. “Hybrid Maritime Warfare.” The RUSI Journal 162 (1): 32–40. doi:10.1080/03071847.2017.1301631.

- Scott, R. 2020. “RNLN Air-defence and Command Frigates to Receive New 127/64 LW Guns.” Jane’s Navy International, 26th April. https://www.janes.com/article/95771/rnln-air-defence-and-command-frigates-to-receive-new-127-64-lw-guns

- Singer, P. W., and A. Cole. 2015. Ghostfleet: A Novel of the Next World War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Snow, S. 2020. “New Marine Littoral Regiment, Designed to Fight in Contested Maritime Environment, Coming to Hawaii.” MarineTimes, May 14th, https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/2020/05/14/new-marine-littoral-regiment-designed-to-fight-in-contested-maritime-environment-coming-to-hawaii/

- Stone, J. 2012. “The Point of the Bayonet.” Technology and Culture 53 (4): 885–908. doi:10.1353/tech.2012.0149.

- Sullivan, B. R. 1998. “The Future Nature of Conflict: A Critique of “The American Revolution in Military Affairs” in the Era of Jointery.” Defense Analysis 14 (2): 91–100. doi:10.1080/07430179808405754.

- Tangredi, S. J. 2019. “Anti-Access Strategies in the Pacific: The United States and China.” Parameters 49 (1/2): 5–20. https://publications.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/3701.pdf

- Technology, N. 2017. “BAE Systems and Leonardo to Partner for New Vulcano Precision-guided Munitions.” NavalTechnology.com. Accessed 16th December 2020. https://www.naval-technology.com/news/newsbae-systems-leonardo-collaborate-to-offer-new-vulcano-precision-guided-munitions-5857322/

- Thornton, R. 2007. Asymmetric Warfare. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Today, N. 2016. “German Corvettes Now Authorized to Use RBS-15 Missiles against Land Targets.” NavalTechnology.com, Accessed 16th December 2020. https://www.navaltoday.com/2016/06/07/german-corvettes-now-authorized-to-use-rbs-15-missiles-against-land-targets/

- van Creveld, M. 1989. Technology and War: From 2000 B. C. To the Present. New York: Macmillan.

- Van Dyke, J. M., M. J. Valencia, and J. M. Garmendia. 2003. “”The North/South Korea Boundary Dispute in the Yellow (West) Sea.”.” Marine Policy 27 (2): 143–158. doi:10.1016/S0308-597X(02)00088-X.

- Walton, S. A. 2019. “Technological Determinism(s) and the Study of War.” Vulcan 7 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1163/22134603-00701003.

- Wasielewski, P. (Lt. Col. USMC). 2000. “Bring Back the Monitors.” Naval War College Review 53(1) 369. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2516&context=nwc-review

- ,Wilhelm, J. 2019. ‘Autopsy of a Future War’, New York: Modern War Institute at West Point, https://mwi.usma.edu/autopsy-future-war/

- Williams, A. G. 2011. “Naval Armament: The MCG Problem”, Blog Military Guns & Ammunition Articles and resources on military technology by Anthony G Williams, 23rd October. Accessed 16th December 2020. http://quarryhs.co.uk/MCG.html

- Yoshihara, T. 2016. “The 1974 Paracels Sea Battle: A Campaign Appraisal.” Naval War College Review 69 (2): 41–65. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol69/iss2/6

- Young, K. L., and C. Carpenter. 2018. “Does Science Fiction Affect Political Fact? Yes and No: A Survey Experiment on “Killer Robots.” International Studies Quarterly 62 (1): 562–576. doi:10.1093/isq/sqy028.

- Zumwalt, E. R. 1976. On Watch: A Memoir. New York: Quadrangle.