ABSTRACT

This article examines the development and performance of formal organisational learning processes in the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) during the Donbas War (2014-present). Through original empirical research conducted with UAF personnel and documentary analysis, the article develops understanding about the detail of UAF lessons-learned processes and their effectiveness in helping to recalibrate UAF activities to operational demands. The article finds that the performance of UAF lessons-learned processes during the Donbas War has, on the whole, been poor. Since the escalation of Russian aggression in 2014, some positive steps which have been taken to implement best-practices in UAF lessons-learned processes. However, the article uncovers a number of organisational activities, structures and processes which could be improved to weaken the negative impact of bureaucratic politics and organisational culture on learning. It concludes with recommendations for the further development of UAF lessons-learned processes. The article highlights the particular importance of improving the capacity of the civilian leadership to exert effective oversight of military learning and of US and NATO support for these efforts.

Introduction: the importance of UAF lessons-learned processes

Since the early 2000s permanent formal lessons-learned processes have proliferated within militaries, especially NATO member-states. Their goal is to improve the ability of armed forces to translate operational and training experiences, and lessons from alliance partners, into wider organisational learning. However, scholarship on lessons-learned processes is in its infancy. Management studies and military innovation studies have only recently begun to reflect upon what constitutes lessons-learned best-practice (Dyson Citation2019). Furthermore, case studies focus on a limited number of armed forces and predominantly upon lessons-learned process performance during expeditionary stabilisation operations or counterinsurgency operations (Dyson Citation2019; Marcus Citation2015).

This article develops understanding of lessons-learned processes within the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) during the post-Cold War era and the Donbas War (2014-present). Through original empirical survey and interview research conducted with UAF personnel, as well as analysis of UAF lessons-learned documents, it examines four important issues which have been neglected by the academic literature on Ukrainian military reform. First, how well the UAF measures up to fundamental features of best-practice in lessons-learned processes. Second, the effectiveness of UAF lessons-learned processes in recalibrating “institutional military” activities to the demands of operations against Russian separatist forces. Third, the factors which have impacted the effectiveness of UAF lessons-learned processes. Finally, the key reforms which need to be implemented to improve the organisational activities, structures and processes supporting organisational learning within the UAF.

In doing so, the study contributes to two broader areas of scholarship. First, to the study of lessons-learned processes by examining, for the first time, the development of lessons-learned processes in the context of a military undertaking multiple years of hybrid warfare. Second, the article’s findings about areas for improvement within UAF lessons-learned processes are of substantial policy relevance for Ukraine at a time when the country is subject to Russian military aggression, which poses a threat to its territorial integrity and survival. The study’s conclusions about how the UAF can more effectively harness bottom-up adaptation and innovation in its defence reform are especially important. Many aspects of the United States’ (US) military transformation paradigm are of limited relevance for Ukraine, particularly given its sparse financial resources (Sanders Citation2017). Thus, the UAF’s ability to learn from its own experiences is imperative. However, the academic literature on Ukrainian defence reform during the post-Cold War era has focused predominantly upon “top-down” defence reform (Bukkvoll and Solovian Citation2020). Hence, the study also makes an important contribution to the study of Ukrainian military reform.

The article begins by briefly examining the key variables internal to militaries which can block effective learning and the fundamental features of best-practice in military lessons-learned. It then undertakes an overview of the post-Cold War development of UAF organisational learning processes. The article proceeds by outlining the research methods used to conduct the field research and by examining the findings of the questionnaires and interviews about the strengths and weaknesses of UAF lessons-learned processes during the first five years of the Donbas War (2014–2019). It finds that during this period the UAF lacked important activities, structures and processes which facilitate the acquisition, management and dissemination of knowledge, as well as the effective combination of new and existing knowledge, with negative consequences for UAF learning.

The article then analyses the implications of these findings for the contemporary development of UAF lessons-learned processes. It focuses in particular upon the study’s ramifications for the most recent and ongoing reform of lessons-learned processes, which began in late-2018 and continues to lack some fundamental features of best-practice. The article concludes by reflecting upon the consequences of its findings for Ukrainian civil-military relations and highlights the importance of strengthening the capacity of Ukraine’s civilian leadership to exert effective oversight of military learning. It also suggests actions that NATO and friendly states can undertake to support this endeavour, as well as key areas for future academic research.

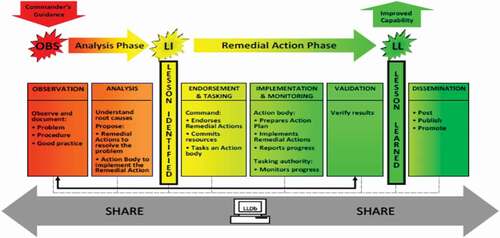

Lessons-learned best practice: enabling absorptive capacity

The NATO Lesson Learned Handbook (Citation2016, 10–13) provides an overview of the basic features of a standard lessons-learned process () and points to four key stages. First, the creation of an observation highlighting an area of military activity that may be improved: “a comment based on something someone has heard, seen or noticed that has been identified and documented as an issue for improvement or a potential best-practice” (NATO Lesson Learned Handbook Citation2016, 11). An observation then enters the analysis stage where the seriousness of a problem is determined and, if required, solutions for improvement are identified (a “remedial action”). This stage of lessons-learned also proposes the relevant bodies of the armed forces which should take responsibility for resolving the problem.

Figure 1. The NATO lessons-learned process.Footnote26

Following completion of these tasks, a “lesson-identified” has been achieved: “a mature observation with a determined root cause of the observed issue and a recommended remedial action and action body, which has been developed and proposed to the appropriate authority” (NATO Lesson Learned Handbook Citation2016, 12). Endorsement and tasking then commences, where a lesson-identified is formally endorsed by the lessons-learned organisation and one or more units/organisations with the armed forces (“action bodies”) are tasked with implementing a remedial action. The action body is then responsible for developing a plan to resolve the lesson-identified and update the lessons-learned organisation on progress. Once the action body’s work is complete a validation process occurs where it is ascertained whether the remedial action has led to measurable improvement (NATO Lesson Learned Handbook Citation2016, 12–13). Following validation, the lesson-identified becomes a lesson-learned: “an improved capability or increased performance” (NATO Lesson Learned Handbook Citation2016, 13). The last stage of the process then begins: dissemination of a lesson-learned to relevant stakeholders within, and also sometimes outside, the armed forces.

The variables which block the effectiveness of lessons-learned processes

Neo-realism posits that the competitive international security environment, and particularly the threat of defeat on the battlefield, should act as a powerful incentive for lessons-learned processes to promote effective inter- and intra-organisational learning about best-practice in military affairs (Dyson Citation2019, 60). However, the academic literature on lessons-learned processes finds that two main variables internal to militaries can adversely impact their ability to foster effective learning at the tactical and operational levels of conflict (Dyson Citation2019, 51–73).

First, bureaucratic politicsFootnote1 draws our attention to the impact of perceptions among officers of the potential for lessons to undermine the budget share or autonomy of their service, branch or unit and also how the military can be a player or a pawn in power struggles between different parts of the state, such as ministries (Dyson Citation2019, 53–55; Käihkö Citation2018, 160).Footnote2 Second, organisational culture can form a potent obstacle to military learning. It can affect the creation, dissemination and use of knowledge within an organisation in two main ways (De Long and Fahey Citation2000, 117–18; Van der Vorm Citation2021, 42–43). The existence of an organisational “culture of blame” can lead personnel to fear the perceived personal reputational damage that can occur as a consequence of sharing knowledge. This culture of blame influences the rules and practices of vertical interaction (the ability to approach senior management) and horizontal interaction (the level of interaction between individuals and units) (De Long and Fahey Citation2000, 120–23). Furthermore, organisational culture can affect learning due to the impact of competing professional role conceptions: competing understandings of the role of the military professionals and the key competencies that they should be capable of delivering. The cultural lenses through which contemporary and historical lessons are viewed can take the form of a dominant cultural narrative, or a more complex, “layered” organisational culture, which shapes the development and adoption of new knowledge, including what issues are problematized and raised as “lessons-identified” (De Long and Fahey Citation2000, 123; Sangar Citation2016, 230–33).

The UAF is composed of three main layers of organisational culture.Footnote3 First, the “Cold War Warriors,” who include the majority of personnel over 50 years old and dominate the senior leadership. Their training took place during the Soviet era and their understanding of the role of the military professional involves the application of high-intensity force against near-peer competitors. This tactical thinking is valuable and relevant for the Donbas War, which has involved substantial attrition and mass (Sanders Citation2017, 38–40). But their focus on high-intensity warfare creates resistance to developing competencies necessary to deliver important activities when facing separatist fighters and Russian forces in eastern Ukraine, such as information operations and humanitarian relief. Furthermore, many of these officers remain wedded to a Soviet model of command, which is highly centralised and deeply-resistant to any form of criticism (Puglisi Citation2015, 12–21). Hence, this generation of soldiers has a high degree of resistance to lessons which emerge from the Donbas War.

The second main layer, the “Peacekeeping Generation,” is composed mainly of personnel between 30 and 50 years old who completed the majority, or all, of their military education in independent Ukraine, but at the beginning of their careers were trained in Soviet military standards. Yet, many of these officers have considerable experience of the Donbas War, and of interaction with foreign officers participating in peace-support operations and international military exercises. Thus, their understanding of the role of the military professional is more nuanced than the “Cold War Warriors.” Consequently, while this middle generation of officers has adopted Soviet military culture, they are much more open to new ideas and radical reform to emulate international military best-practice.

The final layer is the “Donbas War Generation,” whose main operational experiences took place during the Donbas War and are far less influenced by Soviet military culture. Their recent experience of hybrid warfare has left them especially open to new ideas and reform to existing practices (Puglisi Citation2015, 15). This generation is also composed of a substantial proportion of volunteers who originally enlisted with the UAF or with militia battalions at the beginning of the Donbas War (Bukkvoll Citation2019; Sanders Citation2017, 41–44). The militia battalion volunteers were highly patriotic, but also critical of the government and UAF leadership, though their “them and us” mentality was tempered slightly following their absorption into the UAF (Käihkö Citation2018, 159). It has however, fostered an openness to new ideas and as Käihkö (Citation2018) argues, volunteer battalions have evolved “ … from revolutionaries with construction helmets and ice hockey armor to disciplined military formations closely paying attention to NATO standards.”

It is important to note, however, that while the summaries of each generation generally hold true, not all officers exhibit the values and behaviours outlined. Exceptions are especially prevalent among older officers who have experience of the Donbas War, peace-support operations or interaction with NATO, and who therefore tend to be more open to new ideas. Furthermore, it should also be recognised a number of volunteers who were absorbed into the UAF from the militia battalions are older officers. Most of these older volunteer officers welcome “bottom-up” learning and provide constructive criticism of superiors, not least as many are reasonably financially secure and less reliant on commanding officers for housing, or promotion.Footnote4

Overcoming obstacles to learning: the key enablers of military absorptive capacity

Lessons-learned processes cannot fully overcome the negative impact of bureaucratic politics and organisational culture, but the emerging academic literature on lessons-learned suggests that they have the potential to play an important role in ameliorating the corrupting effects of these variables on military learning (Dyson Citation2019; Marcus Citation2015). Management studies scholarship points to four key organisational capabilities which should be actively fostered by military practitioners for a lessons-learned process to play a positive role in overcoming barriers to learning: knowledge acquisition, knowledge management, knowledge dissemination, and knowledge transformation (Dyson Citation2019). Knowledge acquisition refers to a military’s ability to acquire new knowledge from its operational/training experiences, or from alliance partners. An effective knowledge acquisition capability necessitates several best-practices. These include the appointment of Lessons-Learned Staff Officers (LLSO) in the field to seek out successful adaptation or problems, running well-organised after action reviews following a contingent’s return from operations, and post-operational interviews with key commanders and officers from specialist fields. It also necessitates the appointment of Lessons-Learned Points of Contact (LLPOCs) at units and HQs, and posting allied liaison officers within alliance partner warfare development centres (NATO Lesson Learned Handbook Citation2016, 17, 43; NRU Citation2020).

Knowledge management involves the development of the hardware and software necessary to manage data across the lessons-learned process, from the observation stage to the dissemination stage. It is especially important that knowledge is organised in a manner that makes sense to different specialist fields within the military and that they are consulted in the development of software (Dyson Citation2019, 26–28). Knowledge dissemination refers to the capability to disseminate the knowledge and individual lessons which emerge from a lessons-learned process to key stakeholders within and outside the military. It is enabled by ensuring that knowledge is actively cast to relevant stakeholders, but also broadcast widely within the armed forces through lessons-learned publications (Dyson Citation2019, 29–30). Collectively knowledge acquisition, management and dissemination deliver “potential absorptive capacity”: the ability of a military to acquire and assimilate knowledge.

However, if a lessons-learned process is to achieve “realised absorptive capacity,” it is essential that it is capable of a final and most important capability: knowledge transformation, which refers to the effective combination of new and existing organisational knowledge. Its key enabler is a culture of experimentation and creativity, which allows a military to bridge the gap between knowing that change is needed and “doing” change (Pedler et al. Citation1989, 7). The academic literature on lessons-learned processes highlights a number of best-practices which are essential to knowledge transformation. They relate (i) to the internal organisational processes of a lessons-learned process and (ii) to the wider organisational activities within which a lessons-learned process is embedded and which influence cultural acceptance of lessons-learned.

The crucial activity with respect to internal lessons-learned organisational processes is the establishment of a cross-functional team to oversee the remedial action stage of lessons-learned. An effective cross-functional team brings together leaders from different functional areas of the institutional military to take responsibility for appointing action bodies to deal with problems, follows up remedial actions, validates that a remedial action has been completed, and ensures effective dissemination (Dyson Citation2019, 38). The experiences of NATO militaries highlights that cross-functional teams play a vital role in ameliorating the negative impact that bureaucratic politics and organisational culture can exert on lessons-learned processes (Dyson Citation2020).

Five further activities external to a lessons-learned process stand out as especially important in enabling knowledge transformation. First, promotion processes should be developed which reward experimentation and creativity. They should evaluate an individual’s commitment to self-education and reward activities which contribute to the armed forces’ intellectual dynamism (Dyson Citation2019, 36). Second, safe spaces should be created for experimentation and failure in training exercises (e.g. through war-gaming) (Dyson Citation2019, 154; Perla and McGrady Citation2011). Third, it is important that publications exist where officers are able to engage in critical and open discussion of contemporary approaches to doctrine, training and officer education, and which also invite critical contributions from outsiders, such as academics and allied liaison officers (Foley et al. Citation2011, 267–68). Fourth, the military should permit the organisations and units which form its intellectual firepower (e.g. military history research institutes and doctrinal think-tanks/working groups) a high-level of autonomy in their work to avoid interference from the military and civilian hierarchy and ensure their ability to critique. Ideally, these organisations should also be closely involved with the editorial work of military publications (Dyson Citation2019, 36).

Fifth, it is important that service personnel are trained and encouraged to apply the principle of “mission command,” which permits a measure of freedom for tactical-level adaptation. Mission command necessitates that tactical-level personnel are endowed with qualities usually seen as more appropriate to the operational-level: intellect, creativity and the ability to think independently and critically (Kiszely Citation2013, 129). Hence, the final fundamental feature of best-practice in knowledge transformation is that officer education and foundational training strikes a careful balance between these qualities and the need for attributes which are more traditionally associated with military professionals, such as discipline, obedience and conformity (Kiszely Citation2013, 129). In short, service personnel need to be equipped with the ability to demonstrate creativity, critical thought and initiative, and to understand when it is appropriate to do so (Ploumis Citation2020, 213).

UAF lessons-learned processes from the Cold War to the Donbas War

The UAF employed a permanent semiformal lessons-learned process between the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and 2018. Known as the “System of Lessons Analysis and Dissemination” (SLAD), it experienced two phases of development (Pashchuk and Pashkovskyi Citation2019, 36). The first period (December 1991-May 2013), was one of lessons-learned stagnation. The second stage (May 2013-November 2018) involved intensification of Russian aggression and partial reform, with a focus on NATO best-practices. Since November 2018 the UAF has begun more far-reaching reform to replace the SLAD with a new Lessons Learned System (LLS) (LL Citation2018, 1–2).

Until 2013 the SLAD embodied few features of best-practice in potential and realised absorptive capacity. Underfunding and gapped posts constituted major problems (White Paper Citation2010, 21). But most importantly, the SLAD suffered from serious deficits in its organisational structure (Pashchuk and Pashkovskyi Citation2019, 36–39; Isakov Citation2009, 153–155). It did not have a single body responsible for overseeing the acquisition, management, dissemination, and transformation of knowledge. Rather, these activities were split between the Operations Branch, responsible for knowledge acquisition, management, and dissemination and the Training Branch, responsible for the “remedial action” phase of lessons-learned (Pashchuk Citation2021, 48). In addition, the processes of remedial actions were undeveloped, with little thought given to how to ensure that, once identified, problems were adequately addressed, or best-practices properly disseminated.

Between 1991 and 2014, the SLAD focused on two main areas of activity. First, national/multinational training exercises. National training exercises were few in number. Between 1991 and 2014 only one exercise of the size of regiment or above took place (Wilk Citation2017, 22). But there was a steady increase in Ukrainian participation in international military exercises. For example, between 2006 and 2011 more than 23,000 Ukrainian service personnel took part in 95 multinational exercises, of which 43 were held in Ukraine (MOD Citation2021, 5). However, Training Branch took the lead in organising and running these exercises and developed lessons without the input of the Operations Branch (Pashchuk Citation2021, 50). Hence, the SLAD had little opportunity to develop and refine its absorptive capacity.

The second main area of activity was peace-support operations. Ukraine became a very active participant in post-Cold War peace-support operations. Since the first Ukrainian troops were deployed in UNPROFOR in 1992 almost 30,000 Ukrainian service personnel have taken part in more than 23 peace-support operations (MOD Citation2021, 6). This experience fostered some improvement in training for peace-support operations and provided the UAF with valuable operational experiences (Chumak and Razumtsev Citation2004). But these improvements were largely the result of informal learning processes and without an effective SLAD, significant shortcomings persisted in training, which threatened reputational damage for Ukraine at the UN (Kotelyanets Citation2012, 189). Hence, in 2011 a standard operating procedure (SOP) was adopted which sought to clarify a lessons-learned process dedicated to peace-support operations (MOD Citation2011). However, the SOP suffered from a lack of clear procedures about how to gather, analyse, store, and disseminate observations/best-practices, and there were no cross-functional teams, leading to poor follow-up of remedial actions. Few UAF personnel displayed initiative in submitting observations and the quality of knowledge obtained was generally very poor (Isakov Citation2009, 154–155; Pashchuk and Pashkovskyi Citation2019, 37; Pashchuk Citation2021, 51).

Where the SLAD identified and disseminated best-practices from peace-support operations they did not flow into the wider institutional military for the development of doctrine, military equipment, officer education, or operational planning and were only passed to military units in the field (Kotelyanets Citation2012, 187–189; Pashchuk Citation2021, 51). Few printed publications sharing operational experience were released, which only had a small circulation. In addition, due to insufficient funding the UAF did not have a lessons-learned database until 2017, thus knowledge management was non-existent (Pashchuk and Pashkovskyi Citation2019, 37). Furthermore, lessons-learned did not feature in officer education and training (Pashchuk and Pashkovskyi Citation2019, 37). In sum, between the end of the Cold War and 2013, the SLAD existed only in name and its knowledge acquisition, management, dissemination, and transformation capabilities were very poorly developed. Hence, the UAF’s capacity to integrate relevant lessons from its operational experiences and international partners into key institutional military activities was limited.

Reform of the SLAD 2013-2018

The Ukraine-NATO Military Committee of 13–15 May 2013 formed a turning point for SLAD reform (LL Citation2014, 1). It alerted the then Chief of the General Staff, General Volodymyr Zamana (2012–14), to NATO lessons-learned practices and led to the establishment of a joint analytical group to develop recommendations for SLAD modernisation. By January 2014 the UAF leadership had approved three initiatives of the analytical group. First, responsibility for the development of lessons-learned processes was given institutional anchoring within the General Staff’s Military-Scientific Department, where a lessons-learned group of two officers would take responsibility for coordinating the development of formal learning processes. Second, additional personnel to support remedial actions were located within the Centre for Operational Standards and Training (COST). Finally, the development of a lessons-learned database was initiated (LL Citation2014, 2–4).

The annexation of Crimea in February/March 2014 and outbreak of conflict in the Donbas region in April 2014 acted as a further spur to improvement in formal learning processes. The SLAD was redirected to focus on learning from experiences of troops participating in the Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) from 13 April 2014 until 30 April 2018 when ATO was reformatted into a Joint Forces Operation (JFO). The Ukrainian military leadership identified two priorities in improving the organisational learning: forming the SLAD organisational structure in the ATO zone and developing lessons-learned SOP (SOP Citation2014). Thus, in August 2014, a lessons-learned section was established at the ATO HQ, including two to three officers appointed on a four to eight months rotation (MSR Citation2018, 40). Later, in June 2015, lessons-learned sections were created in the ATO operational-tactical formations (ATO sectors) (MSR Citation2018, 40). In addition, special mobile lessons-learned groups were established to study the combat experiences of troops in the ATO and upon their return from deployment. These groups consisted of General Staff representatives and relevant experts from the Ukrainian military research and education institutions.

Furthermore, a temporary lessons-learned SOP was adopted in August 2014. It described procedures for learning from ATO experiences, defined bodies responsible for organising the SLAD and contained several other improvements (SOP Citation2014; MSR Citation2018, 40). First, each military unit had to send daily reports about all combat action and keep a register of combat experience in which any soldier could freely write observations about important issues, their causes, and ways to solve them. Officers were required to analyse the register records and report directly to their commanders weekly. Second, designated personnel in military units and ATO HQ, usually its lessons-learned section, had to develop weekly and monthly analytic bulletins with analysis of the most important information on combat experience (SOP Citation2014).

In addition, at the request of the Military Scientific Department, an Interactive Electronic Lessons Learned Database (IELLD) was launched on 31 October 2017 within the secure military network. Between 31 October 2017 and 28 October 2018 more than 300 combat experience bulletins were uploaded and over 180,000 visits to the database were recorded (LL Citation2018, 2). A timetable and template for periodic lessons-learned reports were formally adopted in a General Staff Directive of 9 December 2015 (GS Citation2015). Finally, unit commanders were authorised to transmit high-priority information on combat experience directly to the COST and could make inquiries to this body to obtain information (GS Citation2016). At face value, these reforms appear to strengthen the UAF’s absorptive capacity, especially its potential absorptive capacity. However, there is no academic or military research which has examined the effectiveness of these reforms, hence the analysis in the following sections explores the performance of the SLAD between 2014 and 2019.

Research methods

The analysis draws upon data collected from questionnaires distributed to a sample group of 54 UAF officers and four civilian personnel in three batches: on 16 December 2019 (Group 1: 41 officers undertaking an English language course at the National Army AcademyFootnote5), 10 February 2020 (Group 2: four officers and four civilian personnel from National Army Academy) and 6 March 2020 (Group 3: nine officers from Land Forces Command).

Due to the operational pressures, COVID-19 restrictions, limited UAF recordkeeping, and issues related to confidentiality/military security the sample size is unavoidably limited in number. However personnel on the National Army Academy’s English Language Course and at the Land Forces Command were diverse in rank, length of service, roles (having served in a diverse range of functional areas of the institutional military), and operational experience, ensuring that the sample was as representative as possible within these constraints. 51 of the officers surveyed had operational experience. One (1.9%) had experience of NATO operations and six (11.8%) had experience of UN peacekeeping operations. However, all 51 officers with operational experience had been deployed in the JFO/ATO between 2014 and 2019. Length of deployment in the JFO/ATO ranged from one to 42 months, with the mean length of deployment 5.1 months.

Respondents were diverse in rank, from the level of lieutenant to colonel, and in age, spanning a range of 23 to 64 years old (mean 39.8 years). They were also diverse in years of service, ranging from two to 34 years (mean 18.3 years). This diversity helped ensure that the survey included a range of different professional role conceptions and reduced the impact of differentiation in organisational culture on the survey results. Finally, the questionnaires were completed anonymously and freely as respondents were not obliged to complete the questionnaire. Hence, the conditions were established for respondents to respond in a truthful manner, maximizing the accuracy of data, while minimising the potential for harm. The questionnaire involved closed questions, but also opportunities for respondents to elaborate in greater detail and care was taken to phrase questions in a neutral manner (Burnham et al. Citation2004, 95–98).

The questionnaires were complemented by 17 semi-structured interviews conducted with UAF officers in August and September 2021.Footnote6 Interviewees were selected on the basis of their work with the SLAD, or within key areas of institutional military activity. These interviews allowed the authors to investigate details of UAF absorptive capacity and SLAD effectiveness which could not be analysed via the questionnaires. They were drawn from the General Staff (3), Land Forces Command (1), Air Force Command (1), National Defence University (1), and National Army Academy (11). Their mean age was 46, with a mean length of service of 26 years.

SLAD performance during the Donbas War

(i) Preparing for combat: means of gathering knowledge about the operational environment

The 51 officers who had served in the JFO/ATO were asked to provide information about the means by which they received information about the combat experiences of the previous contingent. The research (see ) highlights that informal knowledge sharing dominates, via personal communication with other personnel (62.7%). Lessons-learned outputs were not widely consulted, while just 17.6% of officers obtained information about the experiences from the outgoing contingent in their pre-deployment training. Only one respondent (1.9%) had used IELLD resources before deployment to the JFO/ATO area. Furthermore, a substantial percentage (21.6%) of respondents received information about combat experience from open sources on the internet.

Table 1. Means of obtaining knowledge about combat experiences of the previous contingent

(ii) Sharing knowledge about combat experiences

The 51 officers with JFO/ATO operational experience were asked how they shared their combat experiences. The vast majority of officers (92.2%) confirmed sharing combat experience. But personal communication dominated, mostly during rotation (86.2%). Formal means of sharing knowledge were thin on the ground, with little engagement with trainers and no engagement whatsoever with the IELLD (see ).

Table 2. Means of sharing combat experiencesFootnote27

(iii) Learning from others: knowledge acquisition from outside the UAF

Respondents (58) were asked to provide information about their use of different means of gathering knowledge about experiences of international partners, or relevant partners from the private sector, with respect to their areas of activity. Again, open source materials (internet) were most popular, with UAF-organised means for generating and disseminating inter-organisational learning playing a secondary role (see ).

Table 3. Inter-organisational knowledge acquisition

(iv) Knowledge dissemination

Respondents (58) were asked to rate on a scale of 0 to 5Footnote7 the utility of different forms of knowledge dissemination in allowing their unit or organisation to gather information about operational experiences in the JFO/ATO. No areas of the SLAD rated as above standard utility, with the majority of areas performing below standard (see ). It is especially striking that open source materials from the internet are more commonly used than all formal means of UAF knowledge dissemination, bar its electronic publications. This focus on open source materials derived in large part from the timing of the launch of the IELLD, on 31 October 2017. Only from October 2017 did UAF military units and other military organisations receive monthly electronic newsletters via the IELLD with information about lessons-identified and lessons-learned.

Table 4. The effectiveness of different forms of knowledge dissemination

(v) The SLAD’s impact on “institutional military” activities

Respondents (58Footnote8) were asked to rate, on a scale of 0 to 5,Footnote9 the impact of the SLAD on the recalibration of institutional military activities to the demands of JFO/ATO operations. The survey suggested that the SLAD exerted a minor-to-standard impact on only two areas of institutional military activity: pre-deployment training and officer education. The SLAD certainly played a role in fostering some relevant changes to lower-level tactics, techniques and procedures in the context of the irregular warfare conducted by pro-Russian forces in Ukrainian territory (Pashchuk and Pashkovskyi Citation2019, 36–37).Footnote10 However, in other key areas, including the modernisation of armaments, doctrine, and organisational structures of the Ukrainian military, SLAD performance was rated as poor (see ).

Table 5. The impact of the SLAD on institutional military activities

(vi) Awareness and effectiveness of remedial actions

Respondents (58) were asked whether they were aware of remedial actions pursued by the SLAD within their section of the military. 84.4% of respondents (49) knew of remedial actions to implement best-practices, or address problems, while 12.1% (7 respondents) were unaware of such actions. However, the effectiveness of these remedial actions was unsatisfactory. Of the respondents aware about remedial actions 44.9% (22) viewed the remedial actions undertaken by the SLAD as effective, 49.0% (24) found them to be moderately effective, while 5.1% (3) stated that they were ineffective.

(vii) The impact of barriers to learning

The survey asked respondents (58) to score the impact of key variables internal to the UAF which can undermine the effectiveness of the SLAD. These variables included: bureaucratic politics, the impact of the command culture within the military hierarchy on the willingness to share knowledge, the impact of professional role conceptions, and finally, socio-psychological factors (i.e. perceptions of personal reputation damage which could be incurred through the improvement of learning processes). Participants were asked to rate on a scale of 0 to 5Footnote11 the negative impact of each variable. The survey suggests that bureaucratic politics exerts a standard-to-serious negative impact on the effectiveness of the SLAD (3.33). A culture of blame (2.9), competing professional role conceptions (2.73) and socio-psychological variables (2.3) are all viewed by respondents as exerting a minor-to-standard negative impact on learning (see ).

Table 6. The impact of barriers to learning

Respondents were also provided with opportunities to highlight further variables which exerted a drag on SLAD effectiveness. Three respondents (5.2%) pointed to an irresponsible approach among some officers when collecting and analysing combat experiences. A further four (6.9%) highlighted a lack of proper training for lessons-learned personnel and commanders, who are thus unable to adequately determine the main causes of problems, identify how to resolve them, or (especially older commanders) lack the ability to use IT systems. Other issues which arose (each one respondent, 1.7%) included cronyism in the appointment of lessons-learned personnel and the disrespect of subordinates by commanders.

(viii) Key practical problems affecting the SLAD

Respondents (58) were also provided with an opportunity to identify the key practical problems facing the SLAD. Missing assessment and implementation processes (72.4%), missing or inadequate technology (74.1%), and poor governance and leadership on behalf of lessons-learned processes (65.5%) emerged as the dominant problems. The lack of sufficiently trained personnel (46.6%) and misunderstanding of the role of the IELLD were also identified as problems by a substantial proportion of respondents (44.8%) (see ). Furthermore, one respondent (1.7%) highlighted the poor processing and dissemination of lessons and a further respondent (1.7%) raised the lack of trained personnel to take responsibility for further developing SLAD activities and processes. Two respondents (3.4%) pointed to an irresponsible attitude of officers and civil servants towards executing lessons-learned procedures. Another respondent (1.7%) raised the problem of senior officer disinterest in the collection and analysis of information about command and control for unsuccessful operations, and the tendency of the military leadership to conceal all mistakes. A further respondent (1.7%) noted that commanders and superiors struggle to accept the ideas and suggestions of subordinates to improve the SLAD.

Table 7. Key practical problems affecting the SLAD

Analysis: the SLAD’s limited absorptive capacity

The survey highlights a number of major weaknesses in the reformed SLAD. The role of the SLAD in knowledge acquisition appears to be limited. The survey () points to a tendency for informal knowledge sharing by troops in the field, which runs the risk of generating “adaptation traps” where knowledge becomes stovepiped (Serena Citation2011, 163). This poor performance in knowledge acquisition highlights the negative consequences of failing to implement key features of lessons-learned best-practice. In particular, it is a result of not filling key posts such as LLPOCs and LLSOs, and of the lack of proper training for the few officers appointed.Footnote12 Professional military education did not provide for adequate basic knowledge for cadets about the lessons-learned process, nor did it educate junior officers in fundamental principles of organisational learning in a military context.Footnote13 The survey showed that only 18.9% of respondents were aware of ongoing reforms to lessons-learned processes.

The survey’s findings also point to the negative impact of the failure to implement best-practices in knowledge management. As highlight, the IELLD performed very poorly in supporting knowledge acquisition from troops in the field, knowledge acquisition from international partners, and in facilitating knowledge dissemination. IELLD software was developed without proper funding and adequate study of other militaries’ database experiences. Hence, the capacity for personnel to access its information was limited due to poor archiving. Furthermore, access to the database was only possible through a small number of terminals in each military organisation, and while 180,000 visits to the IELLD have been recorded, this figure is almost certainly an exaggeration.Footnote14 Moreover, the database was only used by a limited number of UAF personnel to upload lessons-learned bulletins with open source information, as Ukrainian law on the protection of state secrets is especially strict, leading to over-classification of information.Footnote15 Thus, many important observations from troops in the field were not disseminated effectively.Footnote16 In addition, the lack of lessons-learned training for officers, and above all LLSO, fostered poor quality of analysis and information assurance.Footnote17 For example, observations were gathered without a unified template, which frequently failed to identify root causes, or possible remedial actions. Where experiences were entered into the IELLD they were not properly archived. In addition, it is evident from the survey () that the SLAD’s knowledge dissemination capabilities, both broadcasting and active casting, required development, as all key means of knowledge dissemination rated as standard, or poor.

The survey also suggests that the SLAD was unable to achieve knowledge transformation. The SLAD exerted only a moderately positive impact in two areas of institutional military activity: pre-deployment training and officer education, with performance rated as below-par in the improvement of armaments, refinement of doctrine, and development of UAF organisational structures () (Pashchuk and Pashkovskyi Citation2019, 37). The failure of the 2014 SOP to develop the key enabler of knowledge transformation internal to lessons-learned processes – a cross-functional team – was also a major problem, leading to a poor remedial action process. Furthermore, the Lessons-Learned Group within the Military Scientific Department did not have sufficient authority to influence the development of lessons-learned processes. The consequent continuing division of responsibility between the Operations Branch and Training Branch remained a stumbling block to lessons-learned coordination.

In the absence of an effective lessons-learned process that could expose senior commanders to “ground truth,” they generally resisted honest and candid observations. The survey highlights that bureaucratic politics and organisational culture (both a culture of blame and competing professional role conceptions) continue to undermine the effective operation of the SLAD (). The potential implications for budget share and autonomy, fears of personal reputational damage, or the challenge posed to professional role conceptions, fostered an unwillingness and inability to receive and digest constructive criticism. These variables had an especially negative impact on “vertical” knowledge-sharing, as it meant that soldiers hesitated to submit honest observations due to fear of reprisal from their superiors.Footnote18

The 2018 lessons-learned system: delays and continued deficits in absorptive capacity

The SLAD’s poor performance in the face of a persistent threat to Ukraine’s territorial integrity and the urgent need to demonstrate interoperability with NATO, led the military hierarchy to initiate an overhaul of UAF organisational learning capability. In November 2018 a fundamentally new lessons-learned process (the Lessons-Learned System, or LLS) began to be developed with NATO assistance (LL Citation2018; Pashchuk and Pashkovskyi Citation2019, 38). The key developments were outlined in an LLS “Road Map,” which consists of four key initiatives (Pashchuk and Pashkovskyi Citation2019, 41). First, forming a new lessons-learned organisational structure by 30 December 2019 including a Joint Lessons-Learned Section at the J7 Division of the General Staff and Joint Forces Command, as well as subordinate lessons-learned branches within the individual services (Land Forces, Air Force, Navy, Special Operations Forces, and Airborne Assault Troops). Second, adopting NATO lessons-learned guidance as UAF practice, by 30 December 2019. Third, organising effective lessons-learned training for all UAF personnel, including courses designed specifically for LLSOs, by 30 December 2019. Finally, creating a new modern lessons-learned database (Lessons-Learned Portal), by 30 June 2021.

The focus of these reforms on improving the organisational activities and structures of lessons-learned processes is an important step towards redressing problems identified by the survey. However, they have suffered from substantial delays. To date, only the creation of the lessons-learned organisational structure has been completed, including modernising JFO area lessons-learned bodies (MSR Citation2020, 38–40). Best-practices from the NATO lessons-learned process have also not been fully emulated (MSR Citation2020, 110–113; NRU Citation2020, 1–2). The principal lessons-learned doctrinal documents have either been delayed, or not processed (MSR Citation2020, 110). In particular, lessons-learned doctrine (LL Citation2020) and the temporary lessons-learned SOP (SOP Citation2020) were only introduced in July 2020, instead of June 2019 (LL Citation2018, 5).

Furthermore, crucial detail of the lessons-learned process are undeveloped, including documents outlining approaches to key lessons-learned procedures such as gathering and drafting observations, analysing information about problems and positive experiences, validating the results of analysis, and sharing and tracking lessons-learned information. Lessons-learned SOP for different military services and branches are also undeveloped. In addition, the lessons-learned training course at the National Military Academy planned for December 2019 was delayed. Training for course instructors and lessons-learned personnel, were due to be delivered by the NATO Joint Analysis and Lessons Learned Centre’s Advisory and Mobile Training Teams in 2020, but were cancelled due to Covid-19 and were finally conducted in May 2021. The first pilot national lessons-learned course was completed at National Army Academy on 14–18 June 2021.

The Lessons-Learned Portal has also been subject to significant delays. The July 2020 lessons-learned doctrine (LL Citation2020, 19–21) presented three stages for the development of Lessons-Learned Portal infrastructure. The first stage is building the lessons-learned databases in different commands, especially the main databases in the Joint Forces Command and COST. The second stage involves the creation of the Lessons-Learned Portal software and combining the resources of lessons-learned databases with the internet (for open information) and secure networks (for classified information), as well as granting access to authorized users. During the third stage the UAF Lessons-Learned Portal and the NATO Lessons-Learned Portal databases will be integrated for sharing open information and some classified information. These changes are time-consuming, not least because the UAF has multiple databases at different organisations, with different structures and standards for data exchange. This complicates the combination of their resources, their management, and integration with NATO lessons-learned databases. Creating terminology that is understandable across the services and compatible with terms in NATO lessons-learned documents is also an arduous process. These challenges have slowed agreement about the responsibilities of LLSOs, LLPOCs and tasking authorities/action bodies in the remedial action stage of lessons-learned. In addition, there is an urgent need to simplify lessons-learned reporting documents and adjust them to NATO best-practices (NRU Citation2020, 10). Furthermore, the reforms have not addressed the problem of the over-classification of information.

Poor knowledge transformation: few enablers of realised absorptive capacity

While the 2018 LLS Roadmap should lead to some improvement in potential absorptive capacity, it still fails to address vital areas of lessons-learned best-practice, especially the fundamental enablers of knowledge transformation. First, no cross-functional teams exist within the J7 Division or lessons-learned branches of the services. There is recognition among LLSOs of the importance of cross-functional teams and efforts have been made to initiate them by junior and mid-ranking officers involved in developing lessons-learned SOP. However, these efforts have not been supported by the senior leadership that is mostly composed of “Cold War Warriors” who are unenthusiastic about creating organisational structures which may expose their areas of activity to critical scrutiny.Footnote19

Furthermore, UAF promotion processes do not incentivise activities which enable lessons-learned processes to flourish.Footnote20 Promotion is based upon loyalty to the military and political leadership (Puglisi Citation2015, 6). Personnel who speak up and challenge existing orthodoxies are likely to find that their career stalls (Grant Citation2021). In addition, the UAF has struggled to establish safe spaces for experimentation, risk and failure. Since 2014 greater experimentation and risk-taking has been encouraged in some isolated areas of military activity, especially the employment of anti-sniper teams and use of unmanned aerial systems and anti-drone systems. However, in general, military exercises, including with NATO, focus on putting on a “good face” to the senior political and military leadership and to alliance partners, and were described by one interview partner as “sugar coating.”Footnote21 Moreover, there are no possibilities for UAF officers to engage in debates about tactical and operational trends through military publications.Footnote22 The strong dependence of UAF officers on support from their “Cold War Warrior” commanders for promotion and housing leads to fear of reprisal for any perceived criticism of the UAF leadership, however reasonable officers’ ideas may be. As Grant (Citation2021) notes: “Lessons can never be learned formally in the Ukraine military, because it is not acceptable to report failure.”

UAF research institutes have a measure of autonomy and freedom to advocate new ideas in tactical and operational thought. But their capacity to make use of this freedom is constrained by their dominance by the “Cold War Warrior” generation. The majority of the leadership of research institutes consists of personnel who have greater affinity to Russia than to NATO. Furthermore, appointment to these institutes is not based upon ability, but upon support from ministerial officials who expect the research outputs to support their bureaucratic interests (Grant Citation2021). Hence, these institutes fail to provide effective conduits for developments from alliance partners and do not promote learning “from below” which challenges existing orthodoxies.Footnote23

Application of “mission command” in the UAF and the development and encouragement of critical thinking during officer education is also unsatisfactory. Ukrainian military education and the training of troops are moving very slowly from the “old Soviet art of war” to teach officers to conduct decentralised operations across wide areas in rapidly changing environments (Puglisi Citation2015, 12–21). Since 2014 tactical-level infantry training based on NATO standards has been carried out with intensive allied assistance, especially from the US (Grant Citation2021). The training was received enthusiastically by majority of personnel. However, due to manpower shortages, senior commanders as a rule do not participate in the training. Furthermore, operational-level training and officer education focuses on Soviet operational art (Grant Citation2021; Pashchuk Citation2021, 51). Hence, after completing training and developing the skill sets required to apply mission command, officers continue to operate within Soviet-era operational planning and under commanders who see little value in Western military training and education.Footnote24

Conclusions: improving civilian oversight of UAF organisational learning

The case study highlights that neorealism’s insights about military learning have only limited explanatory power. While the threat of defeat during the Donbas War has spurred improvement in UAF lessons-learned processes, they are largely confined to knowledge acquisition, management, and dissemination. The key activities internal and external to the lessons-learned process enabling knowledge transformation have undergone little improvement. Some of the senior military leadership, especially the “Peacekeeping Generation,” have recognised the importance of enhancing learning processes, evidenced by the 2018 LLS Roadmap. But their capacity to effect meaningful reforms to support organisational learning, especially knowledge transformation, is restricted due to ideological and bureaucratic resistance among many “Cold War Warriors,” who dominate the UAF’s upper echelons. Hence, the case study points to the relevance of neoclassical realism, which posits that while the threat of defeat drives improvements in military learning, unit-level factors such as organisational culture and bureaucratic politics can exert a substantial drag on the pace of reform to the activities and processes which enable effective learning. In the case of Ukraine, the negative impact of domestic variables on adherence to military best-practice is so strong that they run the risk of inducing substantial “system punishment,” where the survival of the state itself is threatened due to its weakened ability to respond to Russian aggression (Rathburn Citation2008, 311).

Ameliorating the negative impact of bureaucratic politics and organisational culture on learning will require strong political leadership to empower and promote pro-reform officers. Not least the “Donbas War Generation,” many of whom are very supportive of reforms to enhance the enablers of absorptive capacity, especially knowledge transformation. It will also necessitate improved civilian oversight of the organisational activities, structures and processes which foster UAF absorptive capacity. However, the Ukrainian system of civil-military relations is not fit for purpose, as the UAF’s senior leadership is easily able to bypass parliament, cabinet and the defence ministry, leading to a lack of unity in command and incoherence in management and budget (Grant Citation2021; Puglisi Citation2017). Hence, reform of Ukrainian civil-military relations is urgently required to ensure greater parliamentary and ministerial control and scrutiny of the UAF. Such reform is, though, unlikely to take place without substantial external US pressure, which needs to better utilise the leverage endowed by Ukraine’s reliance on its military assistance.

A variety of changes to US military aid will be necessary to foster meaningful reform. These changes include improved cultural training and briefing for US personnel, longer tours to develop better mutual understanding and trust, and a focus on fostering change to UAF officer education to complement advances in tactical training since 2014 (Grant Citation2021). But it is most important that tougher conditionality is applied to military aid and potential NATO membership to convince Ukraine’s political leadership about the imperative of civilian intervention to support reform-minded officers and stronger parliamentary/ministerial scrutiny of the UAF. It is also important that officer education is reformed to ensure that officers understand the importance of organisational learning and fundamental features of good practice in lessons-learned processes. This reform should be accompanied by a wider training and information campaign to ensure that existing officers are fully-informed about the importance of lessons-learned processes and understand best-practices.

Academic scholarship could help to provide a strong evidence base for such reforms. First, further research is necessary on best-practice in civilian oversight of military learning. Organisational learning has risen up the agenda of NATO member-state armed forces in recent years. Yet, there is little knowledge and understanding of the different models of parliamentary and ministerial oversight of military learning which have emerged, and the effectiveness of incentives and mechanisms they employ (Feaver Citation2003, 286). This is especially true of post-Communist states where scholarship has neglected civilian oversight of organisational learning (Croissant and Kuehn Citation2017). Second, research straddling education policy, military innovation studies and management studies is required. There has been little focus in scholarship on professional military education on how to best develop the skills and knowledge that officers require to promote organisational learning capability, especially in newly-democratic states (Kelly and Johnson-Freese Citation2013).

Three practical challenges beset the above research agendas, which will require changes in practice by academics and practitioners. First, greater cooperation between different academic disciplines will be necessary. Military innovation studies has been dominated by inter-disciplinary research involving history and political science and is yet to take full advantage of opportunities offered by the integration of other disciplines (Griffin Citation2017, 219). For example, there is an urgent need for research at the nexus of human resource management, psychology and military studies to better understand how military promotion processes can enable effective organisational learning.

Second, military innovation studies scholars can do more to enhance practitioner acceptance of academic advice. When compared with other dynamic professional fields, there has been little reflection on best-practice in the dissemination of academic research findings within armed forces (Jans Citation2014, 25–26). Research on military learning is also yet to properly examine the potential of practice theories, which provide the potential to develop very relevant insights for practitioners. This case study of UAF learning has highlighted that a variety of structural variables, both material and cultural play a key role in enabling and blocking learning, but it also points to the importance of agency in overcoming obstacles to learning. With its focus on exploring the lived practices of different communities of military practitioners, practice theoryFootnote25 offers an opportunity to move beyond these dualisms and provide a richer and more dynamic understanding of learning in a military context.

Finally, a positive contribution of academia to the development of lessons-learned will depend upon the willingness of militaries to be open to critical scrutiny. Greater mutual understanding can be enabled by activities which embed/involve academics in military organisations (and vice-versa) and which establish a “revolving door” between academia and the military (Jans Citation2014, 25–26; Mosser Citation2010, 1078–80). In addition, it is vital that militaries follow impartial and transparent approval processes for academic projects which restrict the capacity of gatekeepers to block projects due to the fear of “airing dirty laundry” (Soeters et al. Citation2014, 3–9).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tom Dyson

Dr Tom Dyson is a Reader in International Relations at the Department of Politics and International Relations, Royal Holloway College. He is the author of four books: The Politics of German Defence and Security; Neoclassical Realism and Defence Reform in post-Cold War Europe, European Defence Cooperation in EU Law and IR Theory (co-authored with Theodore Konstadinides), and Organisational Learning and the Modern Army. Dr Dyson has published articles in the British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Contemporary British History, Contemporary Security Policy, Defence Studies, European Law Review, European Security, German Politics and Security Studies. He is presently the PI for an ESRC-funded project on military lessons-learned processes.

Yuriy Pashchuk

Colonel (ret.) Dr Yuriy Pashchuk is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Foreign Languages and Military Translation, Hetman Petro Sahaidachnyi National Army Academy. Dr Pashchuk has published 31 articles in Ukrainian and international journals, on topics which include the development of Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) lessons-learned capability, the implementation of Intelligence, Surveillance, Target Acquisition and Reconnaissance (ISTAR) in the UAF, UAV tactics, and English-language training of Ukrainian service personnel. He is the co-author of three books: Intensive Peacekeeping English Training, Military English Writing, and You Can Speak English.

Notes

1. In the UAF vested interests motivated by corruption may also be publicly manifested as the professional disagreements of organisational culture or bureaucratic politics. But, as Bukkvoll and Solovian (Citation2020, 35) note it is “close to impossible” to disentangle these variables.

2. In particular, the rivalry between the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MoIA) (which controls the national guard reserve battalions and police battalions), whose minister is appointed by the prime minister, and the Ministry of Defence, whose minister is appointed by the president (Käihkö Citation2018, 160).

3. Interviews 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17.

4. Interview 9.

5. Participants on the English language course included personnel from the Army, Airforce, Navy, Special Operations Forces, and from different brigades and operational commands (north, east, south, and west).

6. Participants were provided with an overview of the project’s objectives and information about the purposes to which the data would be put. Potential risks associated with participation were also discussed.

7. 0–1 = No utility-minimal utility; 1–2 = minimal utility-minor utility; 2–3 = minor utility-standard utility; 3–4 = standard utility-positive utility; 4–5 = positive utility-very positive utility.

8. Four respondents (6.9%) declined to respond to this question.

9. 0–1 = No impact-minimal impact; 1–2 = minimal impact-minor impact; 2–3 = minor impact-standard impact; 3–4 = standard impact-positive impact; 4–5 = positive impact-very positive impact.

10. Interviews 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17.

11. 0–1 = No negative impact-minimal negative impact; 1–2 = minimal negative impact-minor negative impact; 2–3 = minor negative impact-standard negative impact; 3–4 = standard negative impact-serious negative impact; 4–5 = serious negative impact-very serious negative impact.

12. Interviews 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17.

13. Ibid.

14. Interview 5.

15. Interview 2.

16. Interviews 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17.

17. Interviews 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9.

18. Ibid.

19. Interviews 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17.

20. Interviews 5, 9.

21. Ibid.

22. Interviews 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17.

23. Interviews 5, 9.

24. Ibid.

25. The problem-solving stream of the practice-turn in IR, seeks to “ … get closer to the actions and lifeworlds of the practitioners who do international relations, to produce knowledge which is of relevance beyond the immediate group of peers and might even address societal concerns or contribute to crafting better policies” (Bueger and Gadinger Citation2014, 5).

26. NATO Lessons-Learned Handbook 2016, 11.

27. Post-operational reports are not mentioned as the information contained is usually highly-classified and cannot be readily shared within incoming soldiers to the JFO/ATO. The information they contain is instead fed into training and/or printed/electronic publications, where appropriate.

References

- Bueger, C., and F. Gadinger. 2014. International Practice Theory: New Perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bukkvoll, T. 2019. “Fighting on Behalf of the State: The Issue of Pro-Government Militia Autonomy in the Donbas War.” Post-Soviet Affairs 35 (4): 293–307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2019.1615810.

- Bukkvoll, T., and V. Solovian. 2020. “The Threat of War and Domestic Restraints to Defence Reform: How Fear of Major Military Conflict Changed and Did Not Change the Ukrainian Military 2014-2019.” Defence Studies 20 (1): 21–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2019.1704176.

- Burnham, P.,Lutz KG, Grant W, Layton-Henry Z . 2004. Research Methods in Politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chumak, V., and A Razumtsev. 2004. “Ukrainian Participation in Peacekeeping: The Yugoslavian Experience.” In Warriors in Peacekeeping: Points of Tension in Complex Cultural Encounters. A Comparative Study Based on Experiences in Bosnia, edited by Callaghan, J., and M. Schönborn, 379–401. Münster: LIT Verlag.

- Croissant, A., and D. Kuehn, eds. 2017. Reforming Civil-Military Relations in New Democracies. Berlin: Springer.

- De Long, D., and L. Fahey. 2000. “Diagnosing Cultural Barriers to Knowledge Management.” Academy of Management Executive 14 (4): 113–127.

- Dyson, T. 2019. Organisational Learning and the Modern Army: A New Model for Lessons-Learned Processes. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Dyson, T. (2020).“'A revolution in military learning? Cross-functional teams and knowledge transformation by lessons-learned processes'.“ European Security 29 (4): 483–505.

- Feaver, P.D. 2003. Armed Servants: Agency, Oversight and Civil-military Relations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Foley, R., S. Griffin, and H. McCartney. 2011. “Transformation in Contact: Learning the Lessons of Modern War.” International Affairs 82 (2): 253–270. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2011.00972.x.

- Grant, G. 2021. “Seven Years of Deadlock: Why Ukraine’s Military Reforms are Going Nowhere and How the US Should Respond”. The Jamestown Foundation. Accessed 3 August 2021. https://jamestown.org/program/why-the-ukrainian-defense-system-fails-to-reform-why-us-support-is-less-than-optimal-and-what-can-we-do-better/

- Griffin, S. 2017. “Military Innovation Studies: Multidisciplinary or Lacking Discipline?” Journal of Strategic Studies 40 (1–2): 196–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2016.1196358.

- GS 2015. “On Approval and Entry into Force of Urgent Reports of the UAF General Staff”. Directive of the UAF General Staff, D-23, 9 December 2015.

- GS 2016. “Procedures for Collection, Analysis and Remedial Actions on Combat Experience”. Order of the Chief of the General Staff, UAF Commander-in-Chief, № 3167, 30 October 2016.

- “Interview 1, Colonel, UAF General Staff”. 13 September 2021.

- “Interview 2, Lieutenant-Colonel, UAF General Staff.” 15 September 2021.

- “Interview 3, Colonel, UAF General Staff.” 7 September 2021.

- “Interview 4, Lieutenant-Colonel, UAF Land Forces Command.” 7 September 2021.

- “Interview 5, Lieutenant-Colonel, UAF Air Force Command.” 30 August 2021.

- “Interview 6, Colonel, UAF National Defence University.” 20 August 2021.

- “Interview 7, Lieutenant-Colonel, National Army Academy.” 17 August 2021.

- “Interview 8, Lieutenant-Colonel, National Army Academy.” 25 August 2021.

- “Interview 9, Colonel (Retired), National Army Academy.” 19 August 2021.

- “Interview 10, Colonel (Retired), National Army Academy.” 19 August 2021.

- “Interview 11, Colonel (Retired), National Army Academy.” 21 August 2021.

- “Interview 12, Colonel (Retired), National Army Academy.” 12 September 2021.

- “Interview 13, Lieutenant-Colonel, National Army Academy.” 17 August 2021.

- “Interview 14, Lieutenant-Colonel, National Army Academy.” 21 August 2021.

- “Interview 15, Lieutenant-Colonel, National Army Academy.” 2 September 2021.

- “Interview 16, Major, National Army Academy.” 27 August 2021.

- “Interview, 17, Captain, National Army Academy.” 27 August 2021.

- Isakov, M., M.Yakovlev, O.Khlopetsky, Y.Vasyliv, et al. 2009. “Analysis of the Existing System of Analysis and Generalization of the Experience of Training in the Land Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.” Collection of Scientific Works 4 22: 150–156.

- Jans, N. 2014. “Getting on the Same Net: How the Theory-Driven Academic Can Better Communicate with the Pragmatic Military Client.” In Routledge Handbook of Research Methods in Military Studies, edited by Soeters, J.,Shields PM, and Rietjens SJ, eds. Abingdon: Routledge. 19–29.

- Käihkö, I. 2018. “A Nation-in-the-Making, in Arms: Control of Force, Strategy and the Ukrainian Volunteer Battalions.” Defence Studies 18 (2): 147–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2018.1461013.

- Kelly, K.P., and J. Johnson-Freese. 2013. “Getting to the Goal in Professional Military Education.” Orbis 58 (1): 119–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2013.11.009.

- Kiszely, J. 2013. “The British Army and Thinking about the Operational Level.” In British Generals in Blair’s Wars, edited by Bailey, J., R. Iron, and H. Strachan, 119–131. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Kotelyanets, О. 2012. “Current Issues of International Peacekeeping Activity in Ukraine: Strategic Priorities.” National Institute for Strategic Studies 2 (23): 185–190.

- LL 2014. “Protocol of the Meeting of the UAF on Creation of Lessons Learned System in the UAF.” 27 January 2014. Kyiv: Military-Scientific Department of the UAF General Staff, 5 [In Ukrainian].

- LL 2018. “Plan to Create a Prospective UAF Lessons Learned System”. UAF General Staff. 27 November 2018. 7.

- LL 2020. “Doctrine for Lessons Learned Process in the Armed Forces of Ukraine”. VKP 7-00(01). 01 July 2020. 30.

- Marcus, R. 2015. “Military Innovation and Tactical Adaptation in the Israel–Hizballah Conflict: The Institutionalization of Lesson-Learning in the IDF.” Journal of Strategic Studies 38 (4): 500–528. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2014.923767.

- MOD 2011. “Approval of the Instruction on Organizing the Participation of National Contingents (Personnel) of the UAF in International Peace Support Operations.” Order of the Minister of Defence of Ukraine, 28 December 2011, No. 840. 21.

- MOD 2021. “Official Site of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine.” Accessed 5 April 2021. https://www.mil.gov.ua/ministry/istoriya.html.

- Mosser, M. 2010. “Puzzles Vs. Problems: The Alleged Disconnect between Academics and Military Practitioners.” Perspectives on Politics 8 (4): 1078–1080. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592710003191.

- MSR 2018. “Military Scientific Research, Final Report, Code “DOSVID-A,” 2018.” State registration № 0118u000090d. Lviv, National Army Academy. 92.

- MSR 2020. “Military Scientific Research, Final Report, Code “DOSVID-ZSV,” 2020.” State registration № 0120u102708. Lviv, National Army Academy. 126.

- NATO Lesson Learned Handbook. 2016. Lisbon: Joint Analysis and Lessons Learned Centre. Third ed. 81.

- NRU. 2020. NATO Representation to Ukraine. Letter NRU 2020/082 Kyiv,Ukraine. 10. 21 August 2020.

- Pashchuk, Y. 2021. “Historical Aspects of Organisational Learning in the UAF in Peacetime 1991-2014.” Military Scientific Journal 35: 44–57.

- Pashchuk, Y., and V. Pashkovskyi. 2019. “Methodological Approach to Forming a Prospective Lessons Learned System in the UAF.” Science and Technology of the Lessons-learned of Ukraine Ukrainian Air Force 4 (37): 36–43.

- Pedler, M., T. Boydell, and J. Burgoyne. 1989. “Towards the Learning Company.” Management Education and Development 20 (1): 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/135050768902000101.

- Perla, P., and E.D. McGrady. 2011. “Why Wargaming Works.” Naval War College Review 64 (3): 111–130.

- Ploumis, M. 2020. “Mission Command and Philosophy for the 21st Century.” Comparative Strategy 39 (2): 209–218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01495933.2020.1718995.

- Puglisi, R. 2015. “General Zhukov and the Cyborgs: A Clash of Civilisation within the UAF.” Istituto Affair Internazionali Working Paper 15 (14): 1–22.

- Puglisi, R. 2017. “Institutional Failure and Civic Activism: The Potential for Democratic Control in post-Maidan Ukraine.” In Reforming Civil-Military Relations in New Democracies, edited by Criossant, A. and J. Kuehn, 41–61. Berlin: Springer.

- Rathburn, B. 2008. “A Rose by Any Other Name? Neoclassical Realism as the Logical and Necessary Extension of Structural Realism.” Security Studies 71 (2): 294–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09636410802098917.

- Sanders, D. 2017. “The War We Want; the War that We Get: Ukraine’s Military Reform and the Conflict in the East.” The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 30 (1): 30–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13518046.2017.1271652.

- Sangar, E. 2016. “The Pitfalls of Learning from Historical Experience: The British Army’s Debate on Useful Lessons for the War in Afghanistan.” Contemporary Security Policy 32 (2): 223–245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2016.1187431.

- Serena, C. 2011. A Revolution in Military Adaptation: The US Army in the Iraq War. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

- Soeters, J., P.M. Shields, S. Rietjens. 2014. “Introduction.” In Handbook of Research Methods in Military Studies, edited by J. Soeters, P. M. Shields, and S. J. Rietjens, 3–9. Abingdon: Routledge.

- SOP 2014. “Temporary Standard Operating Procedures to Chiefs of Command-and-Control Bodies and Commanders of Military Units on the Analysis of Experiences of UAF Troops in Anti-Terrorist Operation and of Remedial Actions.” August 2014. 7 [In Ukrainian].

- SOP 2020. “Temporary Standard Operating Procedures for Lessons-Learned Process in the Armed Forces of Ukraine”. VKP 7-00(01).01.07.July 2020. 72. [In Ukrainian].

- Van der Vorm, M. 2021. “War’s Didactics: A Theoretical Explanation on How Militaries Learn from Conflict.” Research Paper 177. Breda: Netherlands Defence Academy.

- White Paper 2010. “The Armed Forces of Ukraine.” Kyiv: Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, 79 [In Ukrainian].

- Wilk, А. 2017. “The Best Army Ukraine Has Ever Had: Changes in Ukraine’s Armed Forces since the Russian Aggression, 1–44. Vol. 66. Warsaw: Centre for East Studies.