ABSTRACT

This paper examines four of Europe’s more marginal military institutions that receive less attention: the Franco-British Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF); the French led European Intervention Initiative (EI2); the British led Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF); and the Polish, Lithuanian and Ukrainian joint brigade (LITPOLUKRBRIG). These are described here as “interstitial” because they exist in the niches between both the main multilateral security forums (NATO, EU, UN, OSCE) and the national level. They are intermediaries, working like bridges to cover political obstacles, while often borrowing resources from established actors (notably NATO). It is argued here that such institutions are a form of national hedging against institutional blockages within NATO/EU while providing a platform for national defence policy entrepreneurship. In the context of Cold War 2.0 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, such institutional practices should not be dismissed as marginal. They offer a means to deploy European military forces outside formal NATO or EU decision-making structures, a feature which confers a useful flexibility. (161)

Introduction- what lies between?

While the ongoing Ukraine war underscores the centrality of NATO and the EU as the predominant security institutions for Europe, they are not the only ones if we consider a residual role for the OSCE or even the UN. More importantly, national decision-making remains vital for all military matters (Meijer and Wyss Citation2019), an observation reinforced by how different European states have responded to the Ukraine invasion with varying levels of military aid (Antezza et al. Citation2022).

However, this paper argues another level for European security should also be recognised: small, military co-operative institutions which exist at the interstices between the national level and the multilateral institutions, foremost NATO and the EU. The argument advanced here is that these interstitial structures exist not as rivals to national level decision-making, nor as an alternative to the obvious importance of the EU and NATO. Instead they provide contingency in the guise of institutional “work-arounds” to deal with both the limits of national defence provision and the complexities of getting agreement within what are now a very large NATO and EU. For the latter organisations, de facto vetoes, delays, blockages, and caveats are all commonplace. Witness Turkey’s initial attempts to block or at least delay Sweden and Finland’s 2022 NATO membership bidFootnote1 (Michaels and Malsin Citation2022). While the EU has made steady progress in advancing its role in defence policy, divisions remain over the extent of this ambition, as surely as Brexit has removed from the EU one of the most capable of Europe’s militaries.

Military co-operation with a smaller pool of like-minded nations at the interstices of national and multilateral security institutions provides contingencies for scenarios where the EU or NATO may be unwilling, unable or unsuitable to provide a response and where national action alone is either untenable or undesirable. Interstitial military co-operation is therefore an alternative to “ad hocery,” improvisation or the “coalition of the willing” phenomenon (Arnold Citation2022; Karlsrud and Reykers Citation2020, 1519). Such expedients often emerge because alliances do not automatically generate deployable military forces in every case where pivotal states seek to use force (Henke Citation2019, 5–6).

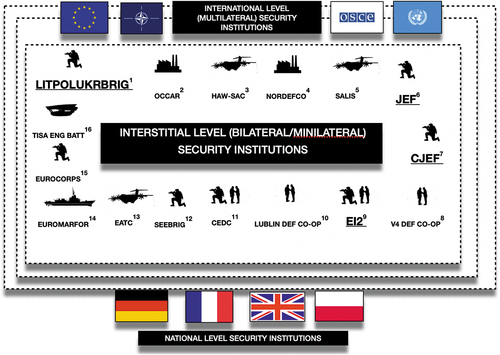

As sets out, over the last decade, a plethora of interstitial military organisations have continued to emerge in Europe. The phenomenon today cannot be explained as a transitional one related to NATO and EU enlargement (Cottey Citation2000, 43–44), nor is it simply driven by “economic” logics that could rationalise joint pooling, sharing and deployment of military assets (Overhage Citation2013).

Figure 1. Three Levels of European Security Institutions with examples of interstitial defence projects.

1. Research questions: why do European states dabble in interstitial military cooperation?

While these forms of European military cooperation have often been ignored or treated as marginal projects (Nemeth Citation2022, 4–11), they have sometimes been analysed as a type of “subregional” defence cooperation (Nemeth Citation2022; Cottey Citation2000) within the wider European region, or else they are just treated as forms of bilateralism and minilateralism whereby European states chose multiple fora to advance their interests (Faure Citation2019).

Both accounts seem partial given that these forms of military cooperation have potential impacts well beyond their members, or the subregional area, while the concept of subregionalism is anyhow quite imprecise (Hamanaka Citation2015, 392–394). Moreover, while the Franco-British CJEF would appear to be the epitome of simple bilateralism, in reality it depends heavily on NATO. French and British troops assigned for duty with any CJEF mission are also in readiness for NATO or other contingencies, and are thus “double hatted” or even “triple hatted” (Müller Citation2020). Describing the JEF or the EI2 as examples of minilateralism also misses the glaring asymmetry of their membership. The JEF is led by Britain, and the UK effectively dominates it through a British military command structure (Heier Citation2019, 189). Neither does the JEF make for a coherent subregional group; the Netherlands and the UK are not Nordic states, and the absence of Germany and Poland as members, means it cannot claim to address subregional Baltic security concerns comprehensively. Describing the EI2 project as minilateral, or possibly subregional, ignores the fact that one state predominates: France. The EI2 originated as an initiative of President Macron and clearly France is the primary state actor that shapes that entity. Neither are the countries that participate in the EI2 regionally coherent: Estonia is the only Baltic and East-European state that is a member, with the remaining dozen being a very diverse set of west European, Mediterranean and Nordic countries.Footnote2

The argument here offers an alternative approach by employing the concept of “interstitial institutionalism” to emphasise the wider, relational, logic of such patterns of military co-operation. While the projects listed in , are residual to centrality of the EU and NATO, and they are secondary to national military institutions, they are not trivial. They offer a means for contingency military planning. They provide some insurance against the uncertainties of “coalition of the willing” dynamics by pre-pooling militaries from states who share a “strategic culture.” And they offer opportunities for relatively cheap, low-cost defence policy entrepreneurship for national elites. Yet at least three questions are left implicit.

Firstly, what European states participate in such projects and why? This “who participates” question can also be rephrased as “who is dominant or most powerful” in each of these projects, or is power, influence and “ownership” fundamentally diffuse within them? A second puzzle relates to the function of these security organizations or the “what question” (i.e. what are they for?). While they all appear to be concerned with military operational capabilities, a plausible alternative is that they are effectively “talking shops” for diplomatic signaling. It is worth noting that none of the cases explored here have ever been deployed operationally.

A final puzzle concerns the timing of their emergence: the “when” question which also relates to “why” these initiatives gather momentum. Why have the four cases examined here all appeared in the last decade (2010–2020) and why not before? The prime facie answer would appear to be renewed Russian aggression. However, in many cases the genesis for some of these projects has been much longer, often well before 2014. Moreover, others like the EI2 initiative, have appeared only recently in 2017. Is it possible then that some of these initiatives (notably the EI2) are following domestic-national, or intra-EU political dynamics, rather than being a response to external stimuli?

Case study selection

The four European interstitial security institutions studied here (CJEF; JEF: EI2: LITHPOLUKRBRIG) have been selected because they are distinctive for promising deployable military forces. Although many forms of defence cooperation are not concerned with operational capabilities, the ability to deploy credible military force is one important threshold in judging whether any form of military co-operation is significant. Indeed, the military credibility of EU military deployments has been an issue (Nováky Citation2018, 211), especially considering that the EU’s Battlegroups have never been deployed (Reykers Citation2017). Even the credibility of NATO forces has been queried, specifically whether NATO “trip-wire” forces in the Baltics are simply too small to have any deterrent effect against a revanchist Russia (Veebel and Ploom Citation2018, 183–4).

These four examples are also chosen because of their increased salience after the invasion of Ukraine (2022), most notably the LITHPOLUKRBRIG, which involves Ukraine, but also the British led JEF, which includes the Baltic states, Finland and Sweden. These are all states who are now in the “frontline” against an increasingly unpredictable Russia. In that context, we must ask what role do security institutions like JEF play? Moreover, why would either the pivotal states, such as France or the UK, or even the smaller ones, invest in such military co-operation, instead of maximising their role at NATO or the EU level?

Other examples of military cooperation either lack this saliency as regards Cold War 2.0, or they do not promise military deployments, while some are more marginal because don’t involve the bigger “pivotal” European states. For example, the Central European Defence Cooperation (CEDC) is a very interesting example but it includes only the former Habsburg statesFootnote3 (Austria, Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia and Croatia) and so far has limited military co-operation to coping with the migrant crisis (Nemeth Citation2022). Collaborations such as NORDEFCO or OCCAR are mainly focused on defence procurement and have already been well studied (Nemeth Citation2022; Wilson and Kárason Citation2020; Møller and Peterson Citation2019, 224; Mawdsley Citation2003). There is also a multi-national South Eastern Europe “peacekeeping” Brigade (SEEBRIG) since 1998,Footnote4 but again this includes mostly small states: Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, North Macedonia, Romania, with the important exception of Turkey. Because all are now in NATO, SEEBRIG does not capture the important dynamic of including militaries who are either non-NATO or EU, whereas this remains a featureFootnote5 of the four cases studied here (the JEF, CJEF, LITHPOLUKRBRIG and EI2).

The four cases examined here are also distinct from the few entirely bespoke military pooling structures, notably the European Air Transport Command which makes its assets available to NATO and the EU, but is distinct from both. Rather than offer functional and narrow defence co-operation over the sharing of technical capabilities, the four institutions studied here, promise the deployment, or at least the orchestration of, actual military forces.

The structure of this paper proceeds by first explaining the concept of interstitial institutions and this is followed by a section which details these four examples. A penultimate section discusses these cases through the lens of a broadly realist theoretical tradition and offers a typology of interstitial security institutions. A final discussion offers observations about their significance, especially in the context of the Ukraine invasion of 2022.

3. The concept of interstitial institutions

The idea of interstitial institutions has been used to explain how institutional change can occur at the EU level through the creation of informal “interstitial” spaces between the formal institutions and the restrictive rules that limit EU constitutional change (Héritier Citation2019). Flynn (Citation2020) has already offered a basic application of the concept to European security although this paper deepens that discussion adding more cases and linking the phenomenon to wider IR theories. Jozef Bátora (Citation2013) used the concept to describe the European External Action Service as interstitial because it is an intermediary between national and international diplomacy.

According to Bátora: “interstices are generated when problems and issues spill over from one problem area to another. In such situations, alternative practice frames addressing these problems arise in the interstices between sets of practices belonging to established organizational fields … .Interstitial emergence may in some cases lead to creation of what may be termed ‘interstitial organizations’ … defined as an organization emerging in interstices between various organizational fields and contingent upon physical, informational, financial, legal and legitimacy resources stemming from organizations belonging to these different organizational fields” (Bátora Citation2013, 601).

This reveals that interstitial organisations often borrow heavily from well-established ones, and they are usually created by reference to these same bodies. They emerge to fulfil some function that the dominant established institutional actors cannot or will not do. They are intermediary institutions offering political “work-arounds” for problems in the bigger institutions.

This does not mean the relationship between interstitial practices and the dominant institutions is merely a simple division of labour. As Bátora notes a great deal of ambiguity is usually inherent with interstitial projects (2013, 601–602). Some interstitial bodies may be eventually incorporated into established institutional structures (as for example the WEU was absorbed by the EU). Others may simply wither in the face of institutional competition. Conversely, some could become institutional rivals to established actors, especially if they prove successful while the latter suffer crises.

The four security organisations examined here can be described as interstitial for a number of reasons. Firstly, they exist in the interstices between the dominant international multilateral security organisations (the EU and NATO) and the national level of defence and security policy. Secondly, they are interstitial because they ambiguously inhabit this political space between both national and international structures, leadership and organisations. Indeed, they seem to thrive on the margins of these classic multilateral institutions, being separate, but not entirely separable, from the bigger entities such as NATO and the EU. In some ways they may be considered as residual or “back-up” appendages to the latter. A more useful metaphor could be to imagine them as bridges covering a political gap or obstacle.

However, they do so by often borrowing resources and their practices from the well-established actors (notably NATO). Any military units they have access to, are also prioritized for national, UN, NATO and/or EU missions, so they are shallow organizations, typically having few dedicated assets, units or cadres.Footnote6 They are also often ambiguous as to whether they are complementary, or an alternative, to the dominant institutional structures. For some states, they may be perceived as both.

4. Alphabet soup? the rise of the CJEF, JEF, LITPOLUKRBRIG and EI2

4.1 The Combined Joint Expeditionary Force

The Franco-British CJEF has been routinely described as a product of high-level bilateral security politics which emerged from th Lancaster House Treaties (2010) (Citation2020 (Pannier Citation2018, 425–429, Citation2013, 549). However, CJEF’s apparent bilateralism is designed to fit within a much wider set of relationships. It is available for NATO, EU or UN missions with other militaries.Footnote7 Therefore, rather than being a simple exercise in bilateralism, CJEF is perhaps better thought of as an interstitial military formation which can operate by design bilaterally, but in practice will more likely be dependent upon and complementary to NATO or EU forces. In the words of the two British and French senior officers with responsibility for CJEF force generation: “it is not about building a new expeditionary force per se, but rather about developing the ability to deploy effectively together from what we already have” (Veitch and Gravêthe Citation2020, 115).

Since 2010 the CJEF has matured through several military exercises to demonstrate a credible military capability that could initiate an amphibious/airborne operation of brigade scale, but it only achieved full operational capability in 2020. Up to 10,000 British and French troops could be deployed, although in reality the actual numbers available is likely to be much smaller (Gagnon Citation2011, 112; Müller Citation2020). Exercise Griffin Strike Citation2019), which took place off the coast of Scotland, practiced a scenario with a significant deployment of vessels (15 ships, 3 submarines) and amphibious infantry. Also of interest is that the CJEF employs a joint operational headquarters, although at the strategic level “significant differences remain in the architecture of the decision-making processes, in intelligence sharing and in targeting” (Gagnon Citation2020, 112–113).

The CJEF capability is probably envisaged for many scenarios well outside Europe, for example the mass extraction of French and UK nationals in Africa or Asia. As one British general described it: “the CJEF has a set of roles which range from conducting crisis management through to non-combatant evacuations and at the most demanding end limited intervention operations and peace enforcement … .we’ve been testing ourselves at that more demanding end because its providing the best training opportunity … [however] … I think the most likely use of the CJEF will be around non-combatant evacuations … and humanitarian assistance.”Footnote8

4.2 The joint expeditionary force

Announced at the NATO Cardiff summit in 2014,Footnote9 this is a British initiative officially described as “a partnership of like-minded nations that provides a high-readiness force of over 10,000 personnel … committed to supporting global and regional peace, stability and security either on its own or through multinational institutions such as NATO.”Footnote10 Founding Members include the UK, Netherlands, Norway, Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, who all signed a detailed MoU in 2015,Footnote11 with Sweden and Finland joining in 2017.

The JEF builds on long standing relationships between the UK, Nordic and Baltic states, notably via an earlier British led “Northern Group” initiativeFootnote12 which was limited to security dialogue (Saxi Citation2017, 187–188; Møller and Peterson Citation2019, 225). However, the JEF is very much a British military framework. Partner countries agree to subordinate any military forces they assign under the command of a senior British officer.Footnote13 Moreover, the decision to launch a mission remains a responsibility for the UK to decide, although in consultation with the partner nations.Footnote14

When the JEF was initiated, the immediate context was Russia’s Crimean annexation and fears that Baltic states could be next. There was then and perhaps even now an uncertainty of NATO acting swiftly enough in such cases (Heier Citation2019, 200). Its political and military attraction is that it can quickly deploy a substantial British-Nordic expeditionary force, free from dithering within NATO. However, this deployment can be later folded up within a NATO framework.

Given its membership, the obvious deployments would be in the Baltic, Nordic, and Arctic regions, however, the JEF could be deployed globally as well.Footnote15 Beginning in 2016,Footnote16 military exercises have demonstrated the ability of the JEF to deploy to “the Northern Flank.” Exercise Baltic Protector, staged in 2019, involved 3,000 personnel and 20 naval vessels (MoD/Ministry of Defence/UK Citation2019).

The JEF was especially reassuring for Sweden and Finland before they decided to join NATO as full members in 2022. Until this recent decision, both countries were somewhat exposed by being in a type of “limbo land.” They did not have NATO’s Article 5 guarantee, notwithstanding a very close relationship with NATO (Wieslander Citation2019). As British Royal Marine Brigadier Matt Jackson deftly explained: “the JEF may be able to act before NATO can and can be viewed as a more immediate reassurance policy … It’s a really useful way of producing a framework for a coalition of the willing without that being the equivalent of an Article 5 … the JEF can act while NATO is thinking” (Eckstein Citation2019).

Given that from 2023 all Nordic and Baltic states will likely be full NATO members this raises the question of whether the JEF has now become redundant? In fact, there are no signs that it lacks political support. Indeed, the Swedish government have highlighted the importance of JEF exercises for 2022. These are rationalised as supporting Sweden and Finland during their transition to full NATO membership and the unpredictable security environment as a result of the Ukraine war (MoD/Ministry of Defence, Sweden. Citation2022.). The JEF for now remains very much alive and well, even as a fully NATO integrated Nordic region emerges.

4.3 The Lithuanian, Polish and Ukrainian joint brigade (LITPOLUKRBRIG)

Formed in 2007, the LITPOLUKRBRIG reflected longstanding co-operation between Poland, Lithuania and the Ukraine since the 1990s on peacekeeping. There was a joint Polish-Lithuanian peacekeeping battalion (1997–2007) and a Polish-Ukrainian peacekeeping battalion (2000–2010) (LITPOLUKRBRIG Citation2018, 17; Żyła Citation2018, 141). Initially the Brigade was simply intended to enhance this peacekeeping capability (Šlekys Citation2017, 52–53). However, it was deprioritised by the pro-Russian Yanukovych presidency during 2010–14 (Żyła Citation2018, 138).

The LITPOLUKRBRIG received much renewed impetus after the 2014 Russo-Ukraine conflict, with initial operational capability announced in December 2016 (Šlekys Citation2017, 52–53). It was given a permanent headquarters in Lublin from January 2016, and a military name which recalled a famous 16th century warlord, notable for inflicting defeats on Russia.Footnote17

LITPOLUKRBRIG has no standing military units, apart from the HQ cadre and a national co-ordination committee which meets regularly. It therefore relies on standby national units for a total force of up to 4,500 soldiers. These include an infantry battalion from each country, but also national military police detachments, all augmented by significant Polish ISTAR,Footnote18 artillery and other combat support elements. There is then a greater Polish military contribution, nonetheless, senior command positions rotate between national contingents (LITPOLUKRBRIG Citation2018, 11).

Today the brigade has become associated with NATO’s role in modernising the Ukrainian armed forces, which however, has notably fallen short of offering Ukraine full membership. This has become very relevant with Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and Russian demands that the country be excluded from NATO. Ironically, before the invasion there was only limited enthusiasm within NATO for full membership, with lukewarm support from Germany and France, and open hostility from spoiler states like Hungary (Sukhankin Citation2019).

As a result, the Ukraine has been offered merely an “enhanced partner” status with NATO (Pifer Citation2019), and it remains very unclear whether full NATO membership will result as the war unfolds.Footnote19 Indeed, it is possible that a negotiated outcome could include provisions that require Ukraine remain outside NATO. This has been considered by Ukraine’s charismatic President Zelensky who suggested such may be acceptable, but only if there were security guarantees that were a functional equivalent to Article 5, and as long as Ukraine would be allowed retain credible means of national defence (Kuldkepp Citation2022). In such a context it is possible that while formal NATO membership for Ukraine is ruled out, informal or minilateral linkages which feature military defence cooperation could be permissible. It is exactly in such a future possible geopolitical reality that the LITHPOLUKRGBRIG could continue to function as a valuable conduit for training and reassurance, without directly involving NATO.

The LITPOLUKRBRIG has already considerable experience of skirting this “grey-zone” as it is formally outside NATO, but yet participates in NATO exercises (i.e. Billon-Galland and Quencez Citation2018) and employs NATO doctrine and procedures. It was certified by NATO during exercise Common Challenge 2016. US National Guard units have played a significant role in training. The brigade was deployed in Polish national exercises Anakonda 2016 and 2018, which featured extensive NATO participation (LITPOLUKRBRIG Citation2018, 13–18). Before the invasion, it was also integrated into the NATO led training and mentoring effort for the Ukrainian armed forces via the Joint Multi-national Training Group Ukraine (JMTU).Footnote20

If its political rationale today has perhaps received a new lease of life, it’s military role has been somewhat less clear-cut. Officially it’s mission is described as: “The Brigade or its elements shall be available for international operations, in compliance with the provisions and principles of the international law … (and it’s task are) … co-operating in the international peacekeeping; tightening regional military co-operation.” (LITPOLUKRBRIG Citation2018, 12). Prior to the invasion of 2022, most commentators agreed that the main role for the LITPOLUKRBRIG would be peacekeeping following a UN mandate (Šlekys Citation2017, 53; Żyła Citation2018, 140) and indeed Fryc contextualises the Brigade as part of wider decision to return to UN peacekeeping on the part of Poland (2020; 9). However, because Russia can exercise its veto within the UN Security Council, the scope for the Brigade to be deployed on such missions is probably quite limited, especially given the souring of Russian relations at the UN following its war on Ukraine.

As Fryc (Citation2020, 5–6) attests, the Brigade therefore stands at a crossroads. As currently established it is unsuited to helping the Ukraine defeat the scale of Russian aggression. Yet in October 2020 the Ukrainian Minister of Defence argued that: “The creation of a joint Lithuanian-Polish-Ukrainian brigade five years ago was a clear signal to the Kremlin that any manifestation of aggression will have a consolidated response,” a formula which appeared to leave open the possibility of the Brigade being used to reinforce Ukraine’s territorial defence, perhaps as a raining platform (MoD/Ministry of Defence (Ukraine). Citation2020).

Yet as of 2022 it remains in something of a hiatus. Nonetheless its political and diplomatic role seems to be steadily shifting towards being an “integration platform,” preparing Ukrainian forces for deeper NATO co-operation, while improving their interoperability and professionalism. It also operates in reverse: as an indirect training laboratory for NATO, where the lessons learned from the Ukraine war can be disseminated (Fryc Citation2020, 8).

4.4 The European intervention initiative (EI2)

In 2017 French President Macron announced:

“I propose … a European intervention initiative aimed at developing a shared strategic culture … I thus propose to our partners that we host in our national armed forces – and I am opening this initiative in the French forces – service members from all European countries desiring to participate, as far upstream as possible, in our operational anticipation, intelligence, planning and support. At the beginning of the next decade, Europe needs to establish a common intervention force, a common defence budget and a common doctrine for action.”Footnote21

As such the EI2 is a creature of the Elyseé Palace and its tiny secretariat is run from the French Defence Ministry (Brzozowski Citation2019). Moreover, it seems motivated by French criticisms with the pace and direction of EU defence and security initiatives, for example, that PESCO involves too many states with too little capacity (Pannier and Schmitt Citation2021, 136–137).

The EI2 was formally launched in July 2018 with a Letter of Intent signed by nine countries.Footnote22 However, the proposal was initially met coolly by Germany, wary of diluting EU efforts such as PESCO (Billon-Galland and Quencez Citation2018). Italy was also slow to join, reflecting tension connected to the Conte-Salvini government, and a new Italian government only signed up in September 2019. Nonetheless, rotating defence ministerial meetings have been hosted, for example by Portugal in September 2020.Footnote23 A work programme was agreed that focused on four areas: strategic foresight, scenarios, doctrine/lessons learned and support to operations.Footnote24 The result is a loose framework to manage French led “European” coalitions of the willing. In the language of a Joint Statement released after the 2nd Inter-ministerial meeting, September 2019, the EI2 is: “ … a flexible, resource-neutral and non-binding forum … ”Footnote25

In military terms what the EI2 promises is rather vague. It does not offer new standing intervention forces, but instead should be thought of as a “strategic workshop” among select European defence staffs to share insights, intelligence and engage in scenario based contingency planning (Billon-Galland and Quencez Citation2018). Indeed, a core EI2 activity relates to a series of revolving Military European Strategic Talks (MEST). While in theory EI2 relates to a full spectrum of capabilities (everything from war-fighting to humanitarian assistance), its limited membership reflects French defence thinking that only a sub-set of the more capable or willing European states can credibly deploy force (Billon-Galland and Quencez Citation2018).

Membership by the UK is therefore very significant post-Brexit. Indeed, Pannier claims it was consciously crafted as a means of shoring up British engagement on security (Pannier Citation2020, 131). EI2 also includes countries like Denmark, who until 2022 had a policy of non-participation in EU security and defence, and were therefore keen to co-operate outside an EU context. However, against the backdrop of the Ukraine war, on June 1st 2022, Danish voters passed by a two thirds majority a referendumFootnote26 that removed Denmark’s opt out from the EU CSDP, which means Denmark can now fully participate in all EU security and defence initiative as their governments choose. For Denmark then the importance of a platform like EI2 has somewhat waned. Nonetheless it is still a useful that the EI2 provides for possible “European” but not EU missions, especially if British military participation is seen as vital and a NATO operation is not politically feasible.

In summary, EI2 remains an unproven entity, or as Lebrun (Citation2018) describes it: “a paper tiger.” It has to date conducted no major exercises. The so-called 2020 Takuba Force in Mali, a grouping of Estonian, Czech, Swedish, Belgian (and other) special forces troops, is not an EI2 deployment as is sometimes assumed and in practice anyhow required significant support from US or NATO assets in the region (Maulny Citation2022:).Footnote27 Instead the EI2ʹs most tangible role to date was to provide planning staff work for the co-ordination in 2019 of Dutch, German and French humanitarian operations in the aftermath of hurricane Dorian in the Caribbean (Bel, Citation2019).

5. Theoretical (realist) perspectives on Europe’s interstitial military projects

In this section, we return to the “puzzles” raised before as regards what is the purpose of such projects, who participates or is powerful within them, and the question of timing. It is here useful to frame the discussion by applying a broadly “realist” perspective, to generate deeper analytical insights. Central to that view is a world where the use of military force is ubiquitous, and wielded most dramatically by the great powers with lesser states engaged in external balancing (alliances) or hedging (Ringsmose and Webber Citation2020, 301). The chief puzzle for a realist is why would such small interstitial projects exist at all in preference to full military alliance participation?

One initial answer is because military alliances are often costly and sometimes restrain the freedom of the most powerful states, which means they can prefer unilateralism or ad hoc coalitions (Tertrais Citation2004, 141). However, unilateral military action is not straightforward for larger states within NATO, such as France, the UK or even the USA. France’s 2013 intervention in Mali was only initiated after a failure to generate sufficient multilateral contributors (Charbonneau and Sears Citation2014, 9) and France has struggled to attract sufficient partners for operations in the Sahel.

Smaller states often fear the exit of great powers from military alliances, and so they will sometimes hedge for such contingencies by internal balancing, which can take the form of reconfiguring their existing forces towards an informal alliance within what they fear may be a waning formal alliance (Castillo and Downes Citation2020, 3–10). This is very relevant in the context of Macron’s comments about a “brain dead NATO” and the way the Trump presidency threatened NATO’s credibility (Momtaz and Gray Citation2019). The same dynamic applies to the EU whose growing military credibility was badly dented by the exit of the UK’s contribution.

As illustrates, the juxtaposition of interstitial military projects emerging at the same time as multiple NATO and EU crises is striking. NATO was left reeling from its ending of combat operations in Afghanistan together with the swift escalation in 2014 of Russia’s violence in the Ukraine, which itself followed the Georgia conflict in 2008. By 2016 NATO faced an adversarial and mercurial Trump administration. The EU was overloaded with Brexit, which weakened EU ambitions to deploy force precisely at the very time the EU embarked on an ambitious expansion of defence policy, with PESCO and a dedicated budget.

Most of the interstitial projects described here actually predate these events by several years, but their maturation occurred alongside these geopolitical trends. Of the four projects, the CJEF and EI2 stand out for probably being the least driven by Russian revanchism. The former reflects a long-standing Franco-British understanding for collaborative contingency planning which goes back to the St. Malo accords (1998). The EI2 conversely, is more recent and shaped more by short-term concerns about Brexit and EU ambitions on defence. Nonetheless, if Brexit, Trump and Crimea have all been catalysts for these projects, that still leaves unanswered what are they for?

When alliances are fractured, realists are unsurprised to see hedging at the margins (Ringsmose and Webber Citation2020, 296–301). Our understanding of interstitial military initiatives needs to be alert to their status as “side” projects on the margins of NATO and the EU. All these interstitial projects combine NATO and EU members who are protected by Article 5, or to a lesser extent Article 42, but also countries who are outside either NATO or the EU, or both in the case of the Ukraine. Realists would also be unsurprised how the two foremost European military powers, France and the UK, play the leading role in three of the initiatives here. The JEF is plainly a British led project. The EI2 was initiated and remains dominated by France. The CJEF ostensibly brings them both together, free to act by themselves. These two most powerful European military states want options to avoid becoming a prisoner of NATO or EU dysfunction, and that requires a military capability to use force outside formal alliance structures, although this is likely to be only a last resort.

The EI2 has the merit of allowing for British participation in future European security contingencies but without the torturous politics of brokering a formal UK role in EU missions, which is for now politically taboo in domestic British politics. For the same reason, the EI2 is attractive to non-EU Norway. Moreover, the EI2 platform remains fundamentally attractive to France in cases where leadership in Paris would fear that any EU mission would become bogged down in excessive caveats from the very large number of EU members and their relatively puny militaries. Finally, the CJEF provides the ultimate hedging option for the two big European military powers to initiate their own operations by themselves should they need to.

In this guise interstitial projects are contingency frameworks in the event of NATO or EU paralysis. Such a condition is not hypothetical. We should recall that at the early stage of the Libya intervention (2011) there were calls for a non-NATO, Franco-British led mission to get around American, Turkish and German reluctance within NATO (Pannier Citation2018, 435; Richards Citation2014, 336–337). Today, either the ready-made CJEF or JEF interstitial structures could be employed to make such a contingency more credible, especially for lower intensity threats.

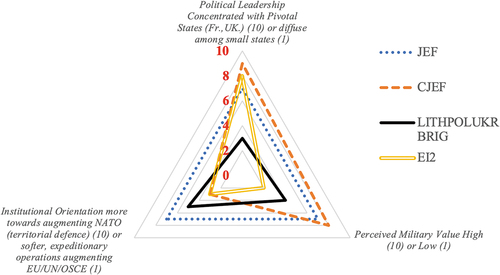

In summary, we can conceive of these interstitial military forms of cooperation as existing within a typology which positions them along a spectrum of critical institutional variables. and (below) provide such a typology placing the four cases discussed here within a tripartite series of variables. The first of these is political leadership: whether the interstitial project is led by pivotal states such as the UK, France or is leadership and “ownership” more diffuse? A second important variable concerns the perceived military value of the interstitial project. This can be approximated by participation of the larger more capable military powers, but also to what extent the interstitial project in question has run military exercises or has dedicated military planning cadres associated with it? Conversely, where any interstitial project offers no military exercises or has no obvious military units associated with it, we can judge it to be of low military value. A third and final spectrum of possibilities is whether the interstitial project is more addressed to resolving problems with NATO, and therefore hard security/territorial defence concerns, or if it is more focused on the EU, or possibly the UN/OSCE, as a means of providing softer security and expeditionary forces for contingencies outside Europe?

Table 1. Ranking Interstitial Military Projects across three variables.

The four cases in this paper have been ranked across these three categories, using a subjective scoring system from 1–10, to produce an indicative typology which reveals how they can be distinguished from one another. Notably, the JEF would appear to be more balanced across the three domains, which might suggest it is a more robust institutional project, more likely to be sustained or perceived as useful. In contrast, the EI2 appears to be, literally, more truncated in its appeal, with a smaller and narrower profile reflecting its lack of relevance to NATO territorial defence concerns, and its limited military utility, not having sustained or participated in any large military exercises, unlike the other three cases. This suggest the EI2 is fundamentally a weaker and more marginal interstitial project, at least so far.

6. Conclusions on Europe’s Interstitial Military Cooperation-just a side show?

Considering that none of these interstitial projects have ever been deployed operationally and that they are clearly secondary to both the EU/NATO or national levels, is it not tempting to conclude that they can be dismissed as of marginal significance-“side shows to the main events,” especially in the context of the Russo-Ukraine war?

Such dismissiveness is not warranted if we remember that interstitial practices are not typically fully formed alternatives to existing dominant institutional patterns, but they augment and work within, between, across and around existing structures, to provide flexibility. That room for manoeuvre is of considerable utility should a NATO or EU deployment of military forces not prove feasible, typically for political reasons.

For both France and the UK in particular, the CJEF, JEF and possibly the EI2, give them a lot of wriggle room within EU and NATO strictures. They can initiate European, but not EU or NATO, military deployments quite quickly, using either the CJEF or JEF as a “spine” around which to build a coalition of the willing (Gagnon Citation2020, 111).Footnote28 In part, interstitial military cooperations can then be considered as “pre-formed” coalitions of the willing, which reduces some of the friction that would otherwise be inevitable. It also gives both countries a means to suggest/threaten rival or alternative deployments of force during EU or NATO deliberations, which may confer some leverage on them during the complex negotiations that typically feature with both organisations, thus reducing the cost of alliance entrapment for the larger European states.

One obvious limitation is that such flexibility is entirely contingent on London and Paris being in agreement, or that other states will agree to follow them. The bilateral CJEF cannot deploy if these two pivotal states are in profound disagreement. France and the U.K. have had fundamental differences on the use of force in Iraq (2003), SyriaFootnote29 and more lately over Brexit and the AUKUS affair (Faure Citation2019aa, 116; Maulny Citation2020, 125). Should Paris simply prefer an EU mission, this would underscore British diplomatic and military isolation.

For the British led JEF will not be politically usable unless the bulk of its Nordic and other participants, notably the Dutch, are willing to support a British led military deployment. The EI2 is also dependent on securing agreement from quite diverse countries. Italy was slow to join the EI2 which reflected a very serious diplomatic spat between Rome and Paris over the handling of the migrant crisis, and more recently Italy and France have had differences over the ongoing Libyan civil war (Ilardo Citation2018). This augurs poorly for the EI2 to have sufficient consensus for anything more than general staff deliberations.

What is the relevance of such interstitial projects in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine 2022? One can see immediately how the JEF is being used as an “informal alliance” within the NATO alliance to reassure Sweden and Finland as they transition to become full NATO members under the protection of Article 5 A somewhat more radical trajectory of development for the JEF might be to have Ukraine join should hostilities cease. This could have some deterrent signalling effectbutwithout involving NATO, and it would more pragmatically allow for Ukrainian participation in valuable military exercises with the high quality British, Dutch and Nordic militaries.

The LITHPOLUKRBRIG has arguably even more potential here to act as a conduit for informal NATO Ukrainian cooperation: a “backdoor.” For now this is not a problem. Ukrainian military aid appears to be relatively unproblematic, at least as regards its institutional patterning: they are receiving significant military aid on a bilateral basis (most vitally from the USA), yet NATO and the EU are both engaged in structured programmes of military assistance.

However, a future ceasefire and negotiated pause or termination of hostilities may impose restrictions on formal Ukrainian NATO or EU links. In particular Russia will likely seek to stop, delay or dilute full membership by Ukraine of either body. A different US president may seek a more arms-length engagement with Kyiv or EU political consensus to agree co-ordinated military aid may wane. Of course “associate” status with the EU and NATO might continue: Ukraine is a NATO “enhanced partner” and has an association agreement with the EU. Yet, equally a future peace agreement with Russia may place limits upon association, especially as regards military aspects.

While for now the small interstitial LITHPOLUKR brigade might seem rather redundant, in the future such projects could prove a useful way to provide structured links between Ukraine’s armed forces and NATO forces in a way which does not immediately involve either NATO or the EU. A future membership by Ukraine of the British led JEF would also represent one tangible way of reassuring a post-war Ukraine, if it were blocked from full NATO membership.

Here such interstitial projects could reduce the scope for Russian diplomatic objections and de-escalate the issue into “technical military cooperation” while still providing “backdoor” links to NATO standards, training and doctrine. For both Poland and Lithuania, or the UK in the case of the JEF, such expedients offer them a “leadership role,” and thus some leverage over the institutional politics of ongoing and future Ukrainian military aid. To be clear, the LITHPOLUKRBRIG as it is currently structured is optimised to provide a platform for all three countries to share the costs and benefits of international peacekeeping missions. If the LITHPOLUKR brigade is to survive at all, it will probably have to adapt to find a greater relevance for the new realities as the Russo-Ukrainian war unfolds, a process that can only be very uncertain.

For now this analysis has to be tempered by the fact that none of the cases examined here have been deployed. However, this downplays the indirect effects they have. Both the JEF and CJEF have a demonstration effect through staging significant military exercises, often as part of larger NATO training. By merely existing, both the CJEF and JEF exert diplomatic leverage for France and the UK in particular, given them a flexible structure to initiate non-EU or NATO missions if such an expediency is politically required. By way of contrast the influence of the LITPOLUKR brigade and for now, the EI2, is much more marginal at least as regards their military significance.

Nonetheless, all the cases examined here should be accepted as substantive military contingency planning forums which offer ready-made templates for force generation in the event future European, but not EU or NATO, interventions need to be extemporized. For all of these reasons they are not marginal even if they are ambiguous.

Such ambiguity is exactly what interstitial security practices typically exhibit but they cannot for that reason be easily dismissed. The point of this paper has been to illustrate there is lot more happening at the interstices between the national and multilateral levels of European security. To understand Europe’s evolving security ecosystem even at the Ukraine war unfolds, we need to know our CJEF from our JEF. And we need to be alert to the subtle and complex roles that interstitial military co-operation provides, or how it could evolve in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Brendan Flynn

Dr. Brendan Flynn is a lecturer at the School of Political Science and Sociology, University of Galway and currently is Head of Discipline of Political Science. His research interests include maritime security and defence and security studies more broadly, but he also retains an interest in environmental and security issues at the intersection of climate and energy trends. He teaches European politics, International Relations, Ocean and Marine politics.

Notes

1. This veto was only lifted before the Madrid summit 2022 after Turkey received written guarantees from both countries concerning Kurdish activists in their countries.

2. Finland joined in November 2018, and Sweden and Norway in September 2019.

3. Poland has observer status in this organisation.

5. Finland and Sweden are not full NATO members as this was being written, however, full membership is impending. It is generally understood that US guarantees as regards their sovereignty are in place during this transitional period. Obviously, the UK and Norway remain outside of the EU. Ukraine is outside of both NATO and the EU, although it enjoys enhanced partner status with NATO and association agreements with the EU.

6. For example, in the CJEF Exercise Wessex Storm, held in November 2020, the Regiment Etranger de Parachutistes (2e REP), part of the famous Foreign Legion, was attached to the British Army’s 2 PARA (MOD, UK, 2020). Both units have in the past been heavily tasked as part of national missions but also NATO operations. Elements of 2 PARA battalion were deployed in Operations Veritas and Fingal in 2002 to stabilise Kabul and in 2001 to Macedonia (Operation Bessemer) as part of NATO disarmament initiative of local Albanian insurgents. It is currently assigned under the 16th Air Assault Brigade. Troops from the latter formation have been air dropped into Estonia (Operation Cabrit) and Ukraine (Operation Solidarity). The 2 REP is part of an analogous French Army 11e Brigade Parachutiste, with the difference that this brigade (as of 2021) sits within a French 3e Divisional structure, whereas the 16th Air Assault is effectively an independent brigade.

7. In the language of the French National Assembly’s Commission de la Défense Nationale et des Forces Armées, the CJEF is “disponible pour des opérations bilatérales, de l’Otan, de l’UE, des Nations Unies ou autres” (available for bilateral, NATO, EU, United Nations operations or others). See: CDNFA (2020).

8. See these comments by Major General Patrick Sanders, British Army, during Exercise Griffin Strike 2016, at Janes/IHS Video April 26th, 2016, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tyeKkDaDspU.

9. Gov.uk (2014) “International partners sign Joint Expeditionary Force agreement”, September 5th, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/international-partners-sign-joint-expeditionary-force-agreement.

10. See MoD/UK (2020) “Comments by UK Defence Secretary Ben Wallace on NATO and European Security signalled through Joint Expeditionary Force Readiness Declaration and Baltic Air Policing deployment”, 13 February 2020, at https://www.raf.mod.uk/news/articles/nato-and-european-security-signalled-through-joint-expeditionary-force-readiness-declaration-and-baltic-air-policing-deployment/.

11. A copy of this can be found at: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/blg-671355.pdf.

12. The membership of the Northern Group is wider than the JEF and includes Germany, Poland and Iceland. See: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-leads-northern-group-response-to-disinformation.

13. See Section 5 and 6.3 Foundation MoU document, 2015.

14. See 8.1 of the Foundation MoU document, 2015.

15. General Sir Richard Davies, explaining the JEF in 2012, argued: “In the Libyan campaign, Jordan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates were able to play a vital role … I look forward to the alliance, perhaps in part through the vehicle of the JEF, working more with non-member states” (Richards Citation2012).

16. Exercise Joint Venture took place in Cornwall during 2016 and appears to have tested British command and control procedures.

17. The name of the brigade is officially “Grand Hetman Kostiantyn Ostrogski”, a general who served the Polish Lithuania Commonwealth in the early 1500s. Amid notable victories were also some spectacular defeats.

18. Intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition, and reconnaissance.

19. On 30 September 2022 Ukraine lodged a formal application to join NATO under conditions of “accelerated accession”, which however, in the words of Khurshudyan and Rauhala (Citation2022) can be viewed as “more symbolic than practical … In practice, the chances of Ukraine joining NATO have only grown slimmer in the course of the Russian invasion. Member countries, including the United States, have drawn clear lines: They arm Ukraine, but they don’t have their own troops on the ground out of concern for triggering a World War.”

21. Full text, in English, of his speech can be found at: https://eaccny.com/news/chapternews/initiative-for-europe-speech-by-m-emmanuel-macron-president-of-the-french-republic/.

22. These were France, Germany, the UK, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Estonia, Portugal and Spain. The text of the letter of intent can be found at: https://www.defense.gouv.fr/english/dgris/international-action/l-iei/l-initiative-europeenne-d-intervention.

27. Czechia is not a member of the EI2. Takuba is a French led, national initiative deployed under the command structure of their national forces in Mali as part of Operation Barkhane See: https://www.defense.gouv.fr/actualites/articles/task-force-takuba-declaration-politique-des-gouvernements-allemand-belge-britannique-danois-estonien-francais-malien-neerlandais-nigerien-norvegien-portugais-suedois-et-tcheque.

28. See also the comments, on the occasion of Exercise Catamaran 2018, by First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Philip Jones, 13 July 2018, who described the CJEF as “a credible mix of French and British units capable of rapidly deploying to a broad range of potential tasks be that on a bilateral basis or as part of a European, NATO or United Nations mission”. At https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JG-V2ug8nY8.

29. In 2013 the British Parliament refused to authorise force against the Syrian government for their use of chemical weapons. However, in August 2014 the British Parliament approved that the UK join the anti-ISIS coalition in Syria and since then British forces have been very active in Syria under Operation Shader using airpower and special forces.

References

- Antezza, A., et al.) 2022. “The Ukraine Support Tracker: Which Countries Help Ukraine and How?”, Kiel Working Paper, No. 2218. Kiel: Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel) https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/262746/1/KWP2218v5.pdf

- Arnold, E. 2022. “Ad-Hoc European Military Cooperation Outside Europe.” Occasional Paper, Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies. London: RUSI, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/occasional-papers/ad-hoc-european-military-cooperation-outside-europe

- Bátora, J. 2013. “The ‘Mitrailleuse Effect’: The EEAS as an Interstitial Organization and the Dynamics of Innovation in Diplomacy.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 51 (4): 598–613. doi:10.1111/jcms.12026.

- Bel, O.R. 2019. “Can Macron’s European Intervention Initiative Make The Europeans Battle-Ready?” War on the Rocks Blog, October.2nd. https://warontherocks.com/2019/10/can-macrons-european-intervention-initiative-make-the-europeans-battle-ready/

- Billon-Galland, A., and M. Quencez. 2018. “European Intervention Initiative: The Big Easy.” Berlin Policy Journal, October 15th. https://berlinpolicyjournal.com/european-intervention-initiative-the-big-easy/

- Brzozowski, A. 2019. “Macron’s Coalition of European Militaries Grows in Force.” Euractiv, September 24th, https://www.euractiv.com/section/defence-and-security/news/macrons-coalition-of-european-militaries-grows-in-force/

- Castillo, J.J., and A.B Downes. 2020. “Loyalty, Hedging, or Exit: How Weaker Alliance Partners Respond to the Rise of New Threats.” Journal of Strategic Studies 1-42. doi:10.1080/01402390.2020.1797690.

- CDNFA/La Commission de la Défense Nationale et des Forces Armées. 2020. Rapport D’information Déposé En Application de L’article 145 du Règlement Par la Commission de la Défense Nationale Et Des Forces Armées En Conclusion Des Travaux D’une Mission D’information Sur le Bilan Des Accords de Lancaster House du 2 Novembre 2010, No. 3490, Octobre 29. (Paris: Assembleé Nationale), https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/15/rapports/cion_def/l15b3490_rapport-information ( Accessed June 23rd 2021).

- Charbonneau, B., and J.M. Sears. 2014. “Fighting for Liberal Peace in Mali? the Limits of International Military Intervention.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 8 (2–3): 192–213. doi:10.1080/17502977.2014.930221.

- Cottey, A. 2000. “Europe’s New Subregionalism.” Journal of Strategic Studies 23 (2): 23–47. doi:10.1080/01402390008437789.

- Eckstein, M. 2019. “New U.K.-Led Maritime First Responder Force Takes to Sea at BALTOPS.” USNI News, June 21. https://news.usni.org/2019/06/21/new-u-k-led-maritime-first-responder-force-takes-to-sea-at-baltops.

- Faure, Samuel B. H. 2019. “Varieties of International co-operation: France’s “Flexilateral” Policy in the Context of Brexit.” French Politics 17 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1057/s41253-019-00079-5.

- Faure, S.B.H. 2019a. “Franco-British Defence Co-operation in the Context of Brexit.” In The United Kingdom’s Defence after Brexit: Britain’s Alliances, Coalitions, and Partnerships, edited by Johnson, R. and J. Haaland Matlarry, 103–125. Cham, CH: Palgrave MacMillan/Springer.

- Flynn, B. 2020. “Europe’s Interstitial Security Institutions: What Relevance for Ireland’s Defence Forces.” Defence Forces Review 2020. edited by Hegarty, P. and C. Dowd, 100–111. Dublin: DFP. https://www.military.ie/en/public-information/publications/defence-forces-review/

- Fryc, M. 2020. “The Lithuanian-Polish-Ukrainian Brigade’s Development Potential in the Context of Regional Security.” Scientific Journal of the Military University of Land Forces 52 (1): 5–11. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0014.0247.

- Gagnon, F-Y. 2020. “The Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF): Operational Force and Vector for Franco-British Common Ambitions.” Revue Défense Nationale 9 (834): 111–114. doi:10.3917/rdna.834.0111.

- Gagnon, F-Y. 2020. “The Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF): Operational Force and Vector for Franco-British Common Ambitions.” Revue Défense Nationale N° 834 (9): 111–114. doi:10.3917/rdna.834.0111.

- Hamanaka, S. 2015. “What Is Subregionalism? Analytical Framework and Two Case Studies from Asia.” Pacific Focus 30 (3): 389–414. doi:10.1111/pafo.12062.

- Heier, T. 2019. “Britain’s Joint Expeditionary Force: A Force of Friends?” In The United Kingdom’s Defence after Brexit: Britain’s Alliances, Coalitions, and Partnerships, edited by Johnson, R. and J. Haaland Matlarry, 189–214. Cham, CH: Palgrave MacMillan/Springer.

- Henke, M.E. 2019. Constructing Allied Cooperation: Diplomacy, Payments, and Power in Multilateral Military Coalitions. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Héritier, A. 2019. “Hidden Power Shifts: Multilevel Governance and Interstitial Institutional Change in Europe.” In Configurations, Dynamics and Mechanisms of Multilevel Governance, edited by Behnke, N., J. Broschek, and J. Sonnicksen, 351–367. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ilardo, M. 2018. “The Rivalry between France and Italy over Libya and Its Southwest Theatre.” Fokus 5, https://www.aies.at/download/2018/AIES-Fokus_2018-05.pdf

- Karlsrud, J., and Y. Reykers. 2020. “Ad Hoc Coalitions and Institutional Exploitation in International Security: Towards a Typology.” Third World Quarterly 41 (9): 1518–1536. doi:10.1080/01436597.2020.1763171.

- Khurshudyan, I., and E. Rauhala. 2022.“Zelensky Pushes ‘Accelerated’ Application for Ukraine NATO Membership”, The Washington Post, September 30th, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/09/30/ukraine-application-nato-russia-war/

- Kuldkepp, M. 2022. ‘Permanent Neutrality for Ukraine Is a Chimera,’ 15th June, RUSI Commentary, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/permanent-neutrality-ukraine-chimera

- Lebrun, M. 2018. Commentary: Behind the European Intervention Initiative: An Expeditionary Coalition of the Willing? 5th July ed. Estonia, Tallin: International Centre for Defence and Security. https://icds.ee/en/behind-the-european-intervention-initiative-an-expeditionary-coalition-of-the-willing/.

- LITPOLUKRBRIG. 2018. LITPOLUKRBRIG Handbook. Lublin: LITPOLUKRBRIG. https://litpolukrbrig.wp.mil.pl/u/INFORMATION_BOOKLET.pdf.

- Maulny, J-P. 2020. “The Franco-British Industrial Relationship At Brexit. “ Revue Défense Nationale.” 9834: 120–126. https://www.cairn.info/revue-defense-nationale-2020-9-page-120.htm.

- Maulny, J-P. 2022. “Takuba Task Force: A New Approach to European Military Cooperation?”, pp.3–9 in Arnold, E. “ Ad-Hoc European Military Cooperation Outside Europe” Occasional Paper, Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies. London: RUSI, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/occasional-papers/ad-hoc-european-military-cooperation-outside-europe

- Mawdsley, J. 2003. “Arms, Agencies, and Accountability: The Case of OCCAR.” European Security 12 (3–4): 95–111. doi:10.1080/09662830390436542.

- Meijer, H., and M. Wyss. 2019. “Upside Down: Reframing European Defence Studies.” Cooperation and Conflict 54 (3): 378–406. doi:10.1177/0010836718790606.

- Michaels, D., and J. Malsin. 2022. “Turkey Backs NATO Membership for Sweden, Finland: Madrid Summit of Alliance Members to Affirm Plan to Rebuild Forces in Europe”, Wall Street Journal, June 28th, https://www.wsj.com/articles/nato-allies-to-focus-on-threats-from-russia-and-beyond-at-summit-11656408633

- MoD/Ministry of Defence, Sweden. 2022. ‘Joint Expeditionary Force Increases Its Presence in Sweden and Finland.’ July 5th, https://www.government.se/articles/2022/07/joint-expeditionary-force-increases-its-presence-in-sweden-and-finland/

- MoD/Ministry of Defence/UK. 2019. “Press Release- UK-led high-readiness Force to Deploy to the Baltic Sea.” April 3rd, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-led-high-readiness-force-to-deploy-to-the-baltic-sea

- MoD/Ministry of Defence/UK and Rt. Hon Ben Wallace. 2020. “Press Release-UK and France Able to Deploy a 10,000 Strong Joint Military Force in Response to Shared Threats,” Nov 2nd, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-and-france-able-to-deploy-a-10000-strong-joint-military-force-in-response-to-shared-threats. (Accessed June 23rd 2021).

- MoD/Ministry of Defence (Ukraine). 2020. “LITPOLUKRBRIG Is a Clear Signal to the Kremlin that Any Manifestation of Aggression Will Have a Consolidated Response – Andrii Taran.” Press Release, October 2nd, https://www.mil.gov.ua/en/news/2020/10/02/litpolukrbrig-is-a-clear-signal-to-the-kremlin-that-any-manifestation-of-aggression-will-have-a-consolidated-response-%E2%80%93-andrii-taran/

- Møller, J., and M. Peterson. 2019. “Sweden, Finland, and the Defence of the Nordic-Baltic Region-Ways of British Leadership.” In The United Kingdom’s Defence after Brexit: Britain’s Alliances, Coalitions, and Partnerships, edited by Johnson, R. and J. Haaland Matlarry, 215–243. Cham, CH: Palgrave MacMillan/Springer.

- Momtaz, R., and A. Gray. 2019. Macron Stands by NATO ‘Brain Death’ Remarks but Tries to Reassure Allies. Politico, Nov.28th. https://www.politico.eu/article/emmanuel-macron-my-brain-death-diagnosis-gave-nato-a-wake-up-call/.

- Müller, B. 2020. “Franco-British Combined Joint Expeditionary Force: Structure, Aims and Pitfalls.” PivotArea Blog, 23 November, https://www.pivotarea.eu/2020/11/23/franco-british-combined-joint-expeditionary-force-structure-aims-and-pitfalls/

- Nemeth, B. 2022. How to Achieve Defence Cooperation in Europe? the Subregional Approach. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Nováky, N.I.M. 2018. “The Credibility of European Union Military Operations’ Deterrence Postures.” International Peacekeeping 25 (2): 191–216. doi:10.1080/13533312.2017.1370581.

- Overhage, T. 2013. “Pool It, Share It, or Lose It: An Economical View on Pooling and Sharing of European Military Capabilities.” Defence and Security Analysis 29 (4): 323–341. doi:10.1080/14751798.2013.842712.

- Pannier, A. 2013. “Understanding the Workings of Interstate Cooperation in Defence: An Exploration into Franco-British Cooperation after the Signing of the Lancaster House Treaty.” European Security 22 (4): 540–558. doi:10.1080/09662839.2013.833908.

- Pannier, A. 2018. “UK-French Defence and Security Cooperation.” In The Handbook of European Defence Policies and Armed Forces, edited by Meijer, H. and M. Wyss, 424–439. Oxford: OUP.

- Pannier, A. 2020. “Beyond Brexit: A Necessary re-launch of Cooperation.” Revue Défense Nationale 9 (834): 127–132. doi:10.3917/rdna.834.005.

- Pannier, A., and O. Schmitt. 2021. French Defence Policy since the End of the Cold War. Cass Military Studies. London: Routledge.

- Pifer, S. 2019. “NATO’s Ukraine Challenge: Ukrainians Want Membership but Obstacles Abound.” Order from Chaos Blog, Brookings Institute, June 6th, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/06/06/natos-ukraine-challenge/

- Reykers, Yf. 2017. “EU Battlegroups: High Costs, No Benefits.” Contemporary Security Policy 38 (3): 457–470. doi:10.1080/13523260.2017.1348568.

- Richards, D. ( Gen.). 2012. RUSI Speech by General Sir David Richards, Chief of the Defence Staff. delivered 17th December. Transcript at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/chief-of-the-defence-staff-general-sir-david-richards-speech-to-the-royal-united-services-institute-rusi-17-december-2012

- Richards, D.2014.General David Richard-The Autobiography: Taking Command.London: Headline. Gen.

- Ringsmose, J., and M. Webber. 2020. “Hedging Their Bets? the Case for a European Pillar in NATO.” Defence Studies 20 (4): 295–317. doi:10.1080/14702436.2020.1823835.

- Saxi, H.L. 2017. “British and German Initiatives for Defence Cooperation: The Joint Expeditionary Force and the Framework Nations Concept.” Defence Studies 17 (2): 171–197. doi:10.1080/14702436.2017.1307690.

- Šlekys, D. 2017. “Lithuania’s Balancing Act.” Journal on Baltic Security 3 (2): 43–54. doi:10.1515/jobs-2017-0008.

- Sukhankin, S. 2019. Ukraine’s Thorny Path to NATO Membership: Mission (im)possible? April 22nd. Estonia: ICDS/International Centre for Defence and Security. https://icds.ee/en/ukraines-stony-path-to-nato-membership-mission-impossible/

- Tertrais, B. 2004. “The Changing Nature of Military Alliances.” Washington Quarterly 27 (2): 133–150. doi:10.1162/016366004773097759.

- Veebel, V., and I. Ploom. 2018. “The Deterrence Credibility of NATO and the Readiness of the Baltic States to Employ the Deterrence Instruments.” Lithuanian Annual Strategic Review 16 (1): 171–200. doi:10.2478/lasr-2018-0007.

- Veitch, A., and Y. Gravêthe. 2020. “CJEF: Construction Of The Land Component Of A Franco- British Expeditionary Force.” Revue Défense Nationale 9 (834): 115–119. https://www.cairn.info/revue-defense-nationale-2020-9-page-115.htm.

- Wieslander, A. 2019. “What Makes an Ally? Sweden and Finland as NATO’s Closest Partners.” Journal of Transatlantic Studies 17 (2): 194–222. doi:10.1057/s42738-019-00019-9.

- Wilson, P., and Í.K. Kárason. 2020. “Vision Accomplished? A Decade of NORDEFCO.” Global Affairs 1–21. doi:10.1080/23340460.2020.1797520.

- Żyła, M. 2018. “Polish-Ukrainian Military Units in the Years 1991-2018.” Security and Defence Quarterly 22 (5): 132–154. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0012.6501.