ABSTRACT

This article examines the extent to which external actors influence the efficiency of the G5 Sahel Joint Force’s (G5S-JF) chain of command and what this means for the relationship between the G5S-JF and external actors. I argue that external actors have taken leading roles within the G5S-JF’s chain of command and that this external influence has increased the efficiency of the joint force’s command. This suggests that the relationship between the G5S-JF and external actors follows the logic of hegemonic theory, with external actors providing efficiency and stability through a strong leading voice, as other scholars have previously assumed. However, I demonstrate that there are limitations to a hegemonic understanding of this relationship, as it does not take into account the agency of the joint force. In fact, as things have developed, the hegemonic stability logic rather appears to have been proven wrong as the strong leading role of external actors was a contributing factor to Mali’s withdrawal in May 2022 and the subsequent instability of the joint force.

Introduction

The G5 Sahel Joint Force (G5S-JF) was established in 2017 as the military branch of the G5 Sahel (G5S) organisation consisting of Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Burkina Faso and Chad. It was then mandated to combat terrorism, illicit trafficking and transnational crime (AU Peace and Security Council Citation2017, 3). Since its establishment, the G5S-JF has been criticised for being inefficient and for lacking the capacity to fulfil its mandate (International Crisis Group Citation2017; Cold-Ravnkilde Citation2018). Subsequently, the G5S-JF has relied on significant support from external actors, where observers have argued that external actors have taken leading roles in the G5S-JF (Dieng, Onguny, and Mfondi Citation2020; Welz Citation2022a). This article examines external actors’ influence on the G5S-JF’s chain of command at the strategic, operational and tactical levels. The external actors examined in this article are: the European Union (EU) Training Mission in Mali (EUTM), which has advised and assisted at the G5S-JF’s headquarters and since 2020 also trained the joint force’s battalions; and the French counter-terrorism operation Barkhane, which has mentored G5S-JF troops on the ground and conducted joint operations with the joint force since 2017. Barkhane expanded this cooperation in 2020 when Barkhane and the G5S-JF entered into shared command.

The involvement of external actors in the G5S-JF raises questions concerning the impact of external support on the joint force’s efficiency and what kind of power dynamics play out in the joint force’s chain of command. Therefore, this article asks: To what extent do external actors influence the efficiency of the G5S-JF’s chain of command, and what does this tell us about the power dynamics between the joint force and external actors?

I examine the chain of command in the G5S-JF through the three levels of war: the strategic level, the operational level, and the tactical level. The analysis is thus structured according to these three levels. The EUTM and EU, and/or Barkhane and France, are present at each level. This article demonstrates that the G5S-JF lacks a strong, united voice within its own chain of command and that external actors have assumed leading roles within the command structure of the G5S-JF. I argue that whilst the external leadership has increased the joint force’s efficiency, this efficiency is not sustainable as it remains dependent on external capacities. I also argue that whilst it might appear that external actors hold a hegemonic role within the G5S-JF, the logic of hegemonic theory is too simplistic an approach for understanding the relationship between external actors and the G5S-JF as it does not take into consideration the agency of the joint force, nor does hegemonic logic explain Mali’s recent withdrawal from the G5S-JF.Footnote1

In the following, I first present the framework of this research, which introduces the three levels of war framework, literature on military efficiency, theory on the relationship between hegemonic power and military efficiency in a coalition, and the methods I use for gathering and analysing data: fieldwork interviews, reports and thematic analysis. I go on to investigate military efficiency at the strategic, operational and tactical levels of the G5S-JF, where I analyse both the internal dynamics of the G5S-JF and the role of external actors. I specifically discuss the suitability of the logic found in hegemonic theory for understanding the impact of external actors on the G5S-JF’s efficiency.

Framing the research

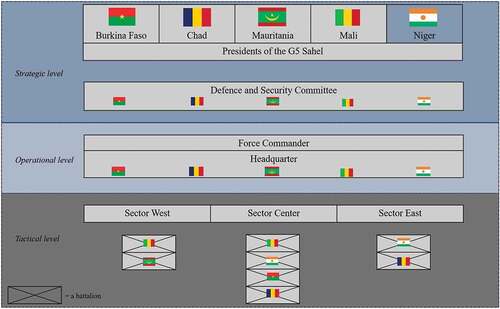

The path from planning to executing military operations is defined in a military’s doctrine and it exists chiefly at three levels: the strategic level, the operational level and the tactical level. This division of warfare mirrors the majority of militaries today and is useful in this article because the G5S-JF was structured in this manner from the very beginning, as shows.

The G5 Sahel member states’ presidents constitute the political strategic level of the G5S-JF, and the defence and security committee constitutes the military strategic level. In this article, these are presented collectively as the strategic level. The political side of the strategic level deals with grand national strategies, where “the political object is the goal, war is the means of reaching it, and means can never be considered in isolation from their purpose” (von Clausewitz Citation1989, 99). Military strategy is about systematising the employment of power through combining different operational campaigns, meaning a series of interrelated military operations or battles (Ikpe Citation2014; Yarger Citation2010). The strategic level thus seeks to answer the question of how to win a war.

The operational level of the G5S-JF is based at its headquarters in Bamako, Mali. The operational level’s main purpose is to translate the strategic level’s objectives and aims into different building blocks, or campaigns, and deals with coordinating, planning and controlling the various campaigns. The operational level therefore “involves the formation and use of a conceptual and contextual framework as the foundation for campaign planning, joint operations order development, and subsequent execution of the campaign” (Allen and Cunningham Citation2010, 258).

The tactical level is carried out by the battalions in the battlefield as well as at the sector headquarters in Sector West on the Mali-Mauritania border, Sector Centre at the tri-border area between Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, and Sector East on the Niger-Chad border. The tactical level deals with the planning and conduct of specific military operations, which means preparing for battle and leading a unit in battle. The first is an analytical activity which aims to choose “the optimal action for success in an uncertain environment,” whereas the second “involves managing and directing the action of one’s unit, with the goal of enforcing one’s demands and objective on the enemy” (Männiste, Pedaste, and Schimanski Citation2019, 398).

Although this framework separates the strategic, operational and tactical commands, these levels are highly connected meaning that the efficiency of the chain matters for the efficiency of the military. The three levels of war framework assumes that the chain of command belongs to one state and its military, and the G5S-JF is a coalition of five states, it constitutes a useful framework of analysis for thoroughly examining external involvement in the G5S-JF chain of command. The three levels therefore form the structure of the analysis in this article.

Efficiency in military coalitions

Working in a military coalition or acting jointly with other military actors have become dominant forms of military action (Finlan, Danielsson, and Lundqvist Citation2021). The academic debate on military coalitions has to a large extent focused on the reasons for their establishment (Henke Citation2017; Walt Citation1990) and their durability (Bennett Citation1997; Auerswald and Saideman Citation2014). Recently, scholars have also started to research how these coalitions actually operate and what this means for their efficiency (see for instance: Auerswald and Saideman Citation2014; Dijkstra Citation2010; Saideman Citation2016). Coalition efficiency is in this article understood as achieving maximum productivity in a well-organised and competent manner, which most often comes down to the coalition’s chain of command (Hope Citation2008; Rice Citation1997). This article draws on and examines three elements in particular from the literature that can impact a coalition’s efficiency: the coherency of its objectives; the clarity of its communication flows; and the dual chain of command for personnel.

First, a key challenge for the efficiency of a coalition’s chain of command is that the sovereign states involved most often have varying objectives and goals, often rooted in diverging geopolitical interests. These vary not only from region to region, but also within a specific region, such as the Sahel (McInnis Citation2013). Various interests can make it difficult to agree on a coalition objective and to exhibit cohesion as a unit, and can ultimately pose challenges for the internal management of the coalition (Snyder Citation1997; Weitsman Citation2003). In the words of Van Dijk and Sloan: “an alliance that lacks a common political purpose will also differ on the threats faced by member states, and as a result fail to organise an effective defense” (van Dijk and Sloan Citation2020, 1016). A variety of objectives is therefore likely to complicate the process of agreeing on joint political and military objectives at the strategic level of a military coalition. This lack of coherence from above further trickles down to impact the efficiency at the operational and tactical levels.

Second, the efficiency of a military coalition also boils down to the efficiency and authority of information flow, such as through orderly communication channels, clear distribution of responsibility, and responsive authorities. In order to obtain or maintain effective command, Nilsson (Citation2020) argues that there needs to be trust in command both horizontally and vertically and a shared understanding of the threat and the cooperation, both of which require strong information and communication flows. King (Citation2021) shows how, increasingly, military command needs to rely on collaborative decisions within a chain of command, which he calls a “command collective,” which contributes to a more dynamic and responsive chain of command. By this logic, distribution of responsibilities and assumed responsibility at various levels, rather than solely at the top, help avoid “bottle-necking” in decision making. This combination of top-down and bottom-up communication enables a more efficient chain of command. Avoiding “bottle-necking” in decision making and having an efficient chain of command further allows the troops on ground to react to security situations rapidly and effectively, allowing the troops to be more efficient. Coalition efficiency therefore also impacts military effectiveness on ground.

Third, military personnel in a coalition have to relate to a dual chain of command: the chain of command of the coalition and their respective state’s Ministry of Defence. McInnis calls this a “hybrid principal-agent relationship” (McInnis Citation2013, 85). It is the state that promotes and selects its military leaders for a coalition, and it is the state that sets the limitations and confers the authority of these personnel (Mello Citation2019). A coalition’s command might thus contradict a command given to military personnel from their own state, making the coalition chain of command less predictable and less effective as it may leave the personnel in an indecisive position, reducing responsiveness on ground. Understanding a partner’s authority within the command, but also the legitimacy of this command, thus becomes of great importance (Cragin Citation2020).

Balancing various objectives, communication channels, distributions of responsibility, and the hybrid principal-agent relationship are not new challenges to a coalition, nor are they unique. However, there are various efforts that reportedly reduce these elements’ impact on a coalition’s efficiency. Some theorists argue that having multiple voices in a coalition poses less of a challenge to efficiency in coalitions where you have one particularly strong member state, such as with the US in NATO (Marston Citation2021). This means that although there are divergences between “what the alliance purports to stand for and what certain member states practice” (van Dijk and Sloan Citation2020, 1015), the one strong member state can assume a determining role in the coalition’s decision-making. This argument aligns with hegemonic reasonings, which are discussed in the next section.

Power dynamics and military efficiency

Hegemonic theory takes a realist perspective on the world and assumes that the international system is anarchic in nature, that states are driven by self-interest and that they are competing for power (Mearsheimer Citation2001). Further, and of particular relevance to this analysis, hegemonic theory argues that a hegemonic system creates stability: when one actor dominates the capacity, resources and capability in a system, it also holds power over other actors, which creates stability (Webb and Krasner Citation1989). Hegemonic theory therefore speaks to dynamics in a relationship, and specifically advocate an asymmetry of power in a relationship. This asymmetry creates dependency between the actors in the relationship, and this dependency ultimately creates stability. This theory is therefore often used to explain the efficiency of NATO through the hegemonic role of the US, which dominates resources and capacity in the coalition, and therefore takes a leading role also within decision-making (Layne Citation2000; M. Nilsson Citation2008; Kreps Citation2011).

This would mean that the challenges of divergent objectives and unclear command may be even more prominent in coalitions where the states are similar in contributions and strengths than in coalitions where there is one leading state. Within the G5S-JF, there is no clear hegemonic or leading member state of the coalition. However, the role external actors play for the G5S-JF is often characterised as pivotal, leading or hegemonic in nature (Welz Citation2022a; Dieng, Onguny, and Mfondi Citation2020). The analysis in this article therefore examines external actors’ impact on the efficiency of the G5S-JF’s chain of command through a hegemonic/leadership perspective, and further discusses what this means for the power dynamics between the joint force and external actors. Through this, the article addresses the impact external actors have on the G5S-JF’s military efficiency, the implications of having leading actors from outside the G5S-JF structure, and the limitations of understanding the relationship between the G5S-JF and external actors as hegemonic in nature.

The analysis builds on data from 45 semi-structured interviews conducted in Nigeria, Mali and France in 2019, 2020 and 2021, respectively.Footnote2 In addition to the interviews, I rely on mandates and official reports from the G5S-JF, the EUTM and Barkhane to understand the dynamics at the various levels. To provide a structured, rich and detailed account of my data, I analyse my data thematically. This is particularly useful for comparing and contrasting perspectives from various interviewees (Braun and Clarke Citation2006; King Citation2004). I look for themes of internal dynamics, external influence and military efficiency. Following the analysis, I discuss the limitations of a hegemonic perspective on the relationship between external actors and the G5S-JF and encourage a more nuanced understanding of their relationship.

The strategic level of the G5 Sahel Joint Force

The headquarters of the G5 Sahel organisation, which constitutes the political strategic level of the G5S-JF, is based in Nouakchott, Mauritania. It includes a permanent secretariat, a council of ministers and the heads of state, and it is the heads of state that “set the main directions and strategic options.”Footnote3 The permanent secretariat manages the strategic interfaces and administers logistics and finances. However, it is the defence and security committee, also based at these headquarters, that has direct contact with the G5S-JF, and thus represents the military strategic level. The defence and security committee brings together the chiefs of staff and other officials from the G5 member states and this is where decisions on military cooperation and dialogues take place.Footnote4

Internal dynamics

Within a coalition, a key challenge is merging the interests of member states and establishing a common ground, which at the strategic level involves defining objectives and strategic concepts. Several interviewees point out that the decision to establish the G5 Sahel organisation, and not least the G5S-JF, is significant in itself, as it has created a space for dialogue between neighbouring states which previously had not engaged in significant cooperation.Footnote5 However, several interviewees also point out that although there are regional interests at stake, and regional threats to respond to, it is difficult for the G5 member states to come to agreement on priorities, as most member states want to prioritise responding to threats in their own country.Footnote6 An interviewee claimed that the “political will isn’t there, because state interests are their individual national interests.”Footnote7 This indicates that the national interests of the G5 member states present obstacles to agreeing on regional strategic interests, as a European security officer claimed:

I think that’s the key problem of the military structure as a whole. Since, yes it exists, and on paper it looks like the military structure and therefore command is autonomous […] but in the end, they are not allowing the structure at all, because they tend to keep all they are holding on to the national with regards to military operations […]. It doesn’t enable community of effort in order to achieve effect.Footnote8

The challenge of uniting a coalition is nothing new, as the literature attests, but through the eyes of my interviewee, it is evident that this has an impact on the efficiency of the G5S-JF’s chain of command, starting at the strategic level.Footnote9 The presence of various national interests at this level and the seeming lack of a clear leader of the coalition thus has implications for the coalition’s efficiency. Furthermore, the lack of a strong leader’s voice or a solid coherence amongst the G5 member states at the strategic level may leave it prone to other strong voices, such as through the influence from external actors.

The role of external actors

Agreeing on mandates, objectives and concepts at the G5S-JF’s strategic level is further complicated by the strong involvement of external partners. Stating that “international actors came with their own plan and ideas,” an interviewee alluded to the fact that the strategy of the military response in the Sahel is characterised by pressure from external actors.Footnote10 Another interviewee specifically claimed that the enemy is defined by France and the EU,Footnote11 which is brought out in other reports too (Dieng, Onguny, and Mfondi Citation2020; Welz Citation2022a). Once the enemy is defined, this impacts most other strategic tasks such as planning the area of operation, defining objectives, and distributing resources. This would suggest a strong level of external influence on the strategic level of the G5S-JF’s chain of command.

France’s role at the G5S-JF’s strategic level appears to be more fundamentally embedded than that of the EU. This is likely due to France’s colonial legacy in the Sahel region (Charbonneau and Chafer Citation2014). With statements such as “this [Sahel] is the backyard of the French, still today”Footnote12 and “the G5 Sahel consists of five states, five Francophone states that France can still control,”Footnote13 several interviewees argued that the relations between France and Sahelian states, while perhaps disputed, nevertheless remain strong. In fact, when a French official was asked why the G5S-JF was established in the first place, she said: “It is considered a useful tool for political long-term engagement, both for France and the EU. The G5 Sahel is now on the map as one of the main actors in the Sahel region. External actors need a recipient, and the G5 is useful for this.”Footnote14 Amongst external actors in the Sahel, there appears to be a concern about the strong French involvement in the G5S-JF.Footnote15 One observer simply stated that “the problem is that it is too French,”Footnote16 suggesting that France’s involvement is rather hegemonic in nature. A European interviewee who participated in meetings of the defence and security committee during the establishment of the G5S-JF claimed that, at the end of every meeting, everyone would be sent out of the room except for the G5 and French officials, who would then finalise decisions behind closed doors.Footnote17 Thus, France appears to have influence on the decision-making in the G5S-JF through providing a strong, leading voice. If so, the literature on hegemonic theory would argue that this could improve the efficiency of the G5S-JF.

The strategic level in a military’s chain of command is also in charge of distributing resources, including weapons and finances. This responsibility is, however, highly influenced by external actors due to the G5S-JF’s dependency on financial and material support. The majority of the G5S-JF’s resources come from external actors, such as France and the EU. However, the resources donated to the G5S-JF are provided bilaterally. This means that it is the donors and the individual G5 member states, and not the G5S-JF’s strategic level, who distribute these resources (UN Security Council Citation2021b, Citation2022). Whilst the decision-making responsibility for resource distribution typically belongs to the strategic level of military actors, we see here that the resource system for the G5S-JF is found outside the coalition structure. When the decision-making responsibility for resource distribution is removed from the strategic level of the G5S-JF, so is some of the joint force’s ownership over its decision-making. One could also assume that the bilateral dealings with donors for resources to the G5S-JF could foster some sort of competition between the G5 member states, and therefore also might make it harder to reach common objectives and priorities at the strategic level.

Thus far, the internal dynamics at the strategic level of the G5S-JF demonstrate that divergences in the perceived security threats and national interests of the member states present challenges for a united approach and a strong voice taking the lead. The external influence on the strategic level of the G5S-JF would likely be there either way due to the objectives and interests of France and the EU, but the lack of a clear leading voice within the strategic level of the G5S-JF appears to leave the joint force even more open to external influence than a coalition would otherwise be. It appears that external actors have a leading voice at the G5S-JF’s strategic level, which could suggest that the role external actors play in the relationship between the joint force and external actors is hegemonic in nature.

The operational level of the G5 Sahel Joint Force

The G5S-JF’s headquarters are based in Bamako, Mali, and constitute the main arena for the operational level. The G5S-JF also holds three sector headquarters – one in Sector West, one in Sector Central, and one in Sector East – which engage partly with operational planning, but mainly with tactical planning.

Internal dynamics

One of the main tasks at the operational level is to coordinate and plan operations. This appears to have been one of the key challenges for the G5S-JF since its establishment due to the internal structure of force (UN Security Council Citation2021a).Footnote18 At the operational level, the force commander of the G5S-JF plays a critical role as all decisions must be approved by him.Footnote19 The reason why the centralised power of the chief commander impacts the efficiency of the force is because it goes against the idea of delegation of responsibility, and thus leaves the rest of the joint force without much leverage to make decisions. Sector headquarters thereby need to await the force commander’s orders to be able to do anything, which appears to have made the communication and chain of command slow (Gasinska and Bohman Citation2017).Footnote20 With an operational and tactical theatre constantly in flux with newly emerging threats and needs to respond to, the battalions of the G5S-JF require the force commander to be present and available at all times for them to operate smoothly. This appears to have constituted an obstacle to efficiency under the second mandate of the force,Footnote21 though it seems to have improved under the third mandate, which has been largely accredited to the force commander.Footnote22 This could suggest that the force commander of the G5S-JF has the potential of assuming a leading voice in the coalition, which could improve the coalition’s efficiency. However, this appears to depend on the personal characteristic of the commander, rather than the system of the chain of command itself (UN Security Council Citation2020).

An external military interviewee claimed that some of the inefficiency seen in the first two mandates of the force can be explained through the notion that “the G5 states want to keep their best officers in their own country.”Footnote23 This state of affairs has allegedly improved during the current, third mandate of the G5S-JF, where the force commander delegates more responsibility and other staff officers appear better equipped to deal with such responsibility.Footnote24 Another military interviewee stated that “I almost want to believe that, as we were moving towards the third mandate, somebody said ‘hey, you don’t send us duds, send us your A-team.’ I have no proof or evidence of that, but it’s hard to explain how we went from having a completely ineffective staff to a pretty good working staff.”Footnote25 This could stem from an initial hesitation by the G5 member states to send their best personnel abroad, due to the risk of not having such resources available for use in internal affairs (Welz Citation2022a). The internal dynamics of the G5S-JF’s operational level thus demonstrate the importance of the chief commander and the related risks of inefficiency due to the centralised power of command, but also how the larger division of responsibility appears to be improving overall, though this appears to remain commander-dependent.

The role of external actors

There is also a strong presence of external actors at the operational level of the G5S-JF. At the G5S-JF’s headquarters, the EUTM advises with a permanent delegation, and experts are brought in for various courses and tasks.Footnote26 In addition, Barkhane have three to four permanent personnel at the joint force’s headquarters, alongside a representative from the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM).

Since the G5S-JF was established, the EUTM has advised and assisted at the G5S-JF’s headquarters in Bamako and has also provided pre-deployment training for those working at the headquarters (European Council Citation2020).Footnote27 Although EUTM personnel do not participate in operational planning themselves, they provide the personnel at headquarters with theoretical training on how to plan operations,Footnote28 which indicates that one of the key tasks of the operational level – planning campaigns and operations – is shaped by the EUTM. The EUTM also administers various tasks for the G5S-JF’s headquarters in Bamako, such as submitting support requests from the G5S-JF to the EU, and paying per diem for G5S-JF personnel (Sahel Citation2019).Footnote29 The EUTM’s presence and influence appears to enhance the efficiency and operationalisation of the joint force’s operational level. The EUTM’s role in the G5S-JF thus far matches their intention of advising and assisting, but does not seem to facilitate the handover of administrative responsibility to the G5S-JF. An interviewee expressed that the EUTM is “creating that environment in which the system is able to stay operational even though it hasn’t got the ability to stay operational by itself,”Footnote30 which suggests that the EUTM’s presence at the G5S-JF’s operational level has become indispensable for the joint force’s headquarters to be efficient, which raises questions concerning the sustainability of such efficiency.

The G5S-JF entered into a shared command structure with Barkhane in 2020 (Kelly Citation2020), which reportedly consists of 12 senior officers from Barkhane and 12 senior officers from the G5S-JF.Footnote31 These are placed at separate headquarters in Niamey, Niger, where all joint operations between the G5S-JF and Barkhane are planned. These headquarters are mainly concerned with the operational level, though they are sometimes also involved with strategic planning. Several interviewees expressed that there has been a noticeable change in the G5S-JF’s effectiveness as a response to the shared command, pointing in particular to more efficiency in the chain of command and greater results in their combat against violent extremist groups in the central sector.Footnote32 This would suggest that French military assistance has a positive effect on the joint force’s military efficiency.

The French objective of this shared command has been to make the G5S-JF more autonomous.Footnote33 However, many interviewees and published reports explain that the joint force has become more dependent on the French than autonomous (Welz Citation2022a; Dieng, Onguny, and Mfondi Citation2020; Sandnes Citation2022). An interviewee expressed that “they [France] might have sold it as a basic idea to give more responsibility to the joint force, however, I explain it more or less as an opportunity to take control, although it sounds very negative, and it might be negative, but to take control over another military element in the broader region.”Footnote34 The same interviewee further expressed that other European actors seem less critical to the G5S-JF under the shared command because France “assure[s] a certain operational tempo and therefore operational effectiveness of the force.”Footnote35

One of the key features of the shared command between Barkhane and the G5S-JF is a joint intelligence cell. This joint intelligence cell has allegedly improved the sharing of intelligence within the G5S-JF, which previously had reportedly been relatively limited.Footnote36 Amongst the interviewees, there was a consensus that the G5S-JF gathers intelligence to some extent, but that it is Barkhane who provides the majority of electronic intelligence, such as listening to phones and use of drones.Footnote37 As a result, it is Barkhane who “decide[s] what kind of information Barkhane will share before they have an operation, with for example the G5 Sahel partners,”Footnote38 suggesting that Barkhane dominates the gathering of intelligence (UN Security Council Citation2021a). Intelligence sharing is ultimately another element that illustrates how the G5S-JF has operated more efficiently with Barkhane than alone, thereby also demonstrating how Barkhane has a significant degree of leadership over the joint force at the operational level.

We see that the operational level of the G5S-JF is characterised by a high presence of external actors. Further, the level of efficiency at this level, which was reported to be low during the first two mandates, appears to be increasing. The leading role external actors have taken within the chain would suggest that improved efficiency at the operational level does not necessarily come from within the G5S-JF structure, but from the external involvement in this structure. Furthermore, there are no significant findings to suggest that external actors are transferring their current responsibilities and decision-making powers over to the G5S-JF. The shared command between the G5S-JF and Barkhane therefore poses a dilemma: the joint force appears to have improved in its efficiency under the French leadership of the shared command, but it relies extensively on the French Barkhane to be this efficient, which raises questions regarding the sustainability of this efficiency, particularly given the French announcement to withdraw its troops from the Sahel in November 2022 (Vincent Citation2022).

The tactical level of the G5 Sahel Joint Force

The tactical level of the G5S-JF is found at its three sectors’ headquarters and initially consisted of seven battalions: on the Mali-Mauritania border, there is one battalion from Mauritania and one from Mali; on the tri-border area of Mali-Niger-Burkina Faso, there is one battalion from Mali, one from Niger and one from Burkina Faso; and, on the Niger-Chad border, there is one battalion from Niger and one from Chad. In 2021, Chad also deployed an eighth battalion to the joint force to operate in the tri-border area, which brought the joint force’s number up from 5,000 to 5,600.

Internal dynamics

The internal dynamics of the G5S-JF’s tactical level are complex and somewhat confusing. Although on paper, each of the battalions consists of approximately 650–700 personnel, “on the ground we don’t really know how many soldiers there are in each battalion.”Footnote39 This might have to do with the fact that the soldiers each country has pledged to the G5 are not fixed, which means that they are shifting, further making it difficult to get a full overview of the G5 soldiers (Gasinska and Bohman Citation2017; Relief Citation2017; Welz Citation2022b).Footnote40 In addition to this lack of an overview over the joint force’s soldiers, there also appears to be a lack of standardisation of training among the soldiers, meaning that the battalions vary in their skill sets. The G5S-JF’s battalions come from different states, which also have different military traditions and trainings. Referring to G5S-JF troops, an interviewee claimed that there is a “huge gap between the brilliant one and the worst one.”Footnote41 This makes delegation of responsibility and decision-making on the ground rather unpredictable, where you have some who are trained and equipped to take initiative, and others who keep a “low profile.”Footnote42

This is further linked to the “hybrid principal-agent relationship” occurring for troops between the G5 chain of command and their national chain of command, which appears to be an obstacle to unity also at the tactical level. Interviewees suggest that troops probably hold more allegiance to the national chain of command than the G5 chain of command due to the set-up of national battalions also being stationed at their home-state.Footnote43 This may be a little different for the Chadian battalion in Sector Central, because this is the only battalion stationed outside its own state. Thus, the varying degrees of training, capacity and, not least, command allegiance of the G5 troops illustrate the challenges for consistency and efficiency on the ground.

The decision-making at the tactical level revolves around planning specific actions and responding to situations in battle. Interviewees suggested that there is “lack of commanding” and “lack of reporting” within and from the tactical level of the G5S-JF.Footnote44 This suggests either a lack of apparent communications channels, or a lack of appreciation of these channels (Gasinska and Bohman Citation2017). An interviewee stated that one of the issues is that there are not enough people with higher ranks deployed, which leaves troops without much disciplinary guidance once in the field.Footnote45 In fact, an interviewee stated that the military culture of the joint force resembles the principle of “all men for themselves,” which does not bode well for either unity or efficiency. This lack of unity and clear commanding at the tactical level leaves limited room for enhancing the military prowess of the force. However, when external actors collaborate with the troops, they appear to operate more coherently and more efficiently, largely due to the clarity of leadership external actors provide.Footnote46

The role of external actors

In 2020, the EUTM was mandated to “provide military assistance to the G5 Sahel Joint Force and to national armed forces in the G5 Sahel countries through military advice, training and mentoring” (European Council Citation2020). As of March 2021, the EUTM had allegedly not trained any particular G5S-JF unit, but had brought in G5S-JF personnel from the three sectors to Bamako for specific training sessions, such as countering improvised explosive devices, which is a tactical-level skill set.Footnote47 According to a European military interviewee, the courses that the EUTM offers are decided based on consultations with Barkhane, as Barkhane operates with the joint force in the field and therefore may identify needs better than the EUTM.Footnote48 The training that the EUTM offers to the tactical level of the G5S-JF appears therefore to be formed by Barkhane’s perspective, which raises questions about how much the G5S-JF’s own perceived needs are taken into consideration. An interviewee expressed that the EUTM has its own ideology of how to do things, which might not match the culture of the G5S-JF.Footnote49 Another specified that the EUTM only trains through their system and with their weapons, which again does not stem from or directly respond to what the G5S-JF needs, or indeed correspond with what weapons the troops of the joint force actually has access to, on the tactical level.Footnote50 The analysis of the tactical level thus suggests that the EUTM decides what type of assistance the joint force receives, and thereby influences the capacity and capability of the forces, yet without perhaps being certain of the needs from the perspective of the joint force itself.

Barkhane is the main collaboration partner to the G5S-JF in the field, and most of the G5S-JF’s operations carried out in the central sector are conducted jointly with Barkhane. Several interviewees argued that the G5S-JF’s troops operate more efficiently and effectively when conducting joint operations with Barkhane, whereas when they plan and operate on their own, they conduct only minor operations.Footnote51 An interviewee expressed that one of the reasons for this is because the G5S-JF’s troops then have more assertive and senior officers to relate to than when operating alone.Footnote52 Another interviewee also stated that this is because there is a general perception within the G5S-JF that “Westerners know best.”Footnote53 France has thus assumed a leading role also at the tactical level of the G5S-JF when conducting joint operations, and this subsequently improves the joint force’s efficiency. Furthermore, it facilitates the joint force’s involvement in larger military operations, thus also suggesting it improves the military aptitude of the joint force.

The tactical level of the G5S-JF shows that there is a lack of unity, coherence and perhaps clear leadership within the joint force when operating in the field. It is therefore not surprising that the joint force improves in efficiency and success in operations when operating with Barkhane, which indeed has very clear leadership, expectations and discipline. However, this also means that for the tactical level of the G5S-JF to be efficient, a high level of cooperation with – or leadership from – Barkhane is needed.

External leadership and military efficiency

The literature presented previously argues that coalitions face challenges for their efficiency due to multiple and diverging objectives and perspectives amongst its member states, which causes disunity and subsequently inefficiency. This can be clearly seen in the case of the G5S-JF: although Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso have shared concerns regarding the spread of al Qaeda and Islamic State groups in their border regions, Chad is concerned with rebel activities in the north and east of the country, Chad and Niger are involved in the fight against Boko Haram, and Mauritania claims its current internal threats are more associated with socio-political tension and corruption than the terror threat the G5S-JF is mandated to combat. Security threats are therefore understood and defined differently amongst member states.

The literature also brings out the challenge of the hybrid principal-agent relationship of the military personnel’s dual chain of command, which seems a particular challenge for the G5S-JF due to its troops primarily being deployed in their home states. The G5S-JF thus appears to face many of the challenges brought out in the literature on military coalitions. However, the literature on military efficiency and coalitions also argues that a coalition with a clear hegemonic leader limits the aforementioned challenges for a coalition and indeed increases a coalition’s efficiency (Dijk and Sloan Citation2020). And although the G5S-JF does not have a clear hegemonic leader within, the analysis demonstrates how external actors have assumed such a leading role for the coalition.

The analysis suggests that the form of security assistance that the EUTM and Barkhane provide enhances the G5S-JF’s operational and tactical efficiency in particular. The involvement of external actors within the G5S-JF’s chain of command comes in many forms: political influence and pressure; administrative control; distribution of resources; training; mentoring; joint operations; and intelligence gathering and sharing, all of which largely reflect hand-holding activities from external actors. In other words, external actors not only have more resources and military capacity, they also partake in important decision-making within the G5S-JF, thereby assuming a somewhat hegemonic position towards the G5 member states. The EUTM’s administrative tasks within the G5S-JF’s headquarters have improved the joint force’s administrative efficiency, and its pre-deployment training of headquarter personnel appears to contribute to a sense of unity and standardisation of skills, which makes the cooperation at the headquarters more efficient. Barkhane’s leadership through the shared command with the joint force and during operations has clearly had a positive impact on both the sophistication and the intensity of the joint force’s operations, which has been recognised both in reports and in the interviews conducted for this research. This speaks to a strain of literature on security force assistance, which predominantly is rather critical of the impact such assistance can have (see for instance: Biddle, Macdonald, and Baker Citation2018; Livingston Citation2011; Shurkin et al. Citation2017; Bartels et al. Citation2019; Jahara and Fowler Citation2020; Nicholas and Rolandsen Citation2021). The case of the G5S-JF demonstrates that the hand-holding type of external assistance can improve the efficiency of a force’s chain of command and intensify its military operations.

However, a significant part of the external support consists of external actors assuming responsibility and conducting various tasks themselves. By taking matters into their own hands in this manner, they are contributing to an increase in efficiency. But, it ought to be expressed here that it is not necessarily the G5S-JF’s own efficiency that increases, as the capacity for the increased efficiency still seems to depend on the external actors’ presence. This raises serious questions about the sustainability – and, ultimately, the stability – of operational efficiency when the actors assuring this are not officially part of the coalition.

The leading role of external actors for the operational efficiency of the G5S-JF suggests that this increased efficiency is unsustainable. When the assistance consists of explaining things in theory and doing tasks for the G5S-JF, such as on the operational level, but not jointly exercising these responsibilities with the G5S-JF, and without active efforts from both sides to transfer this responsibility, the result will rarely be self-sufficient or sustainable. Interviewees agree that although the G5S-JF is demonstrating increased efficiency, it is not becoming more responsible for, nor autonomous in, its own tasks.Footnote54 In fact, an interviewee stated that France and the EUTM’s assistance to the G5S-JF is formed in a way where “you ‘deresponsibilise’ more and more.”Footnote55 For the G5S-JF’s chain of command to be independent and sustainable, there needs to be an end goal of transfer of responsibility. If there is no such transfer of responsibility, the G5S-JF will end up in an endless dependency position.

Concluding remarks: Military efficiency at what cost and for how long?

The leading role of external actors, and particularly France, would suggest a hegemonic relationship between these external actors and the joint force, and accredit the improved military efficiency to this power structure. However, there are limitations to a hegemonic understanding of this relationship. This is first because such a logic does not take into account the agency of the joint force, and second because the external actors have not created stability for the G5S-JF, which is the logic of hegemonic leadership.

At the strategic level, it is not unreasonable to expect that the G5S-JF benefits significantly from aligning its objectives with those of external actors. According to Bayart and Ellis, African states often align their interests to those of external actors in order to make themselves relevant and important to external actors (Bayart Citation2000). By attracting external support, African states somewhat manage whatever dependency they have on external actors, and benefit – as this article has demonstrated – through significant financial support and provided resources. At the operational and tactical levels, the G5S-JF expresses agency through for instance choosing what support and training to accept from the EUTM, and not least it benefits significantly from shared accountability and shared burden when conducting joint operations. Although the relationship between external actors and the G5S-JF is distinctly asymmetric in nature, the manner in which the joint force expresses its agency towards external actors should not be neglected.Footnote56

In an international system, hegemonic theory argues that a hegemonic power relationship provides stability for said system. However, in the case of the G5S-JF, such a hegemonic relationship speaks more to a contingent efficiency – as it remains dependent on external actors – rather than a sustainable efficiency or stable system for the G5S-JF. This is linked to the agency of the G5S-JF and its member states. In May 2022, Mali announced that it would withdraw from the G5S-JF with immediate effect. This came after months of political disputes and quarrelling between Malian and French officials. In the official statement from the Government of Mali, the reason for withdrawing was twofold: first, because Chad refused to transfer the seat of the presidency within the G5 Sahel to Mali due to the Malian military interim government, and second, due to the external interference in and control over the G5S-JF, where Mali alluded particularly to the role of France (France Citation2022). This would suggest that Mali partly withdrew because external actors, particularly France, had assumed such a leading role within the G5S-JF. Mali’s withdrawal from the G5S-JF has caused instability for the coalition and ultimately also inefficiency, which would disprove the logic of a hegemon creating stability, at least when the hegemon has an external identity. This instability and inefficiency stems from the fact, through its withdrawal, Mali removes itself as the geographical epicenter of the Sahelian security threats from the coalition’s area of operation; removes resources, including two battalions to the joint force; and enforces a relocation of the joint force’s headquarters, amongst other challenges.

To conclude, while the logic of hegemony may be useful for understanding the increased efficiency that the G5S-JF has experienced through the assistance from external actors, it speaks more to an efficiency that remains dependent on external support rather than a sustainable efficiency for the G5S-JF. This logic also falls short in explaining the developing power relationship between the external actors and the G5S-JF over time, because it does not address the agency of the G5S-JF. In fact, as things have developed, the hegemonic stability logic appears to have been proven wrong in the case of the G5S-JF, as the strong leading role of external actors was in fact part of the cause for Mali’s departure and the resultant instability in the joint force. This may be due to the leading role being assumed by external actors and not by an internal state to the G5S-JF, which provides an important lesson for future and other military cooperation, particularly regarding contexts where states provide security assistance to other states. Indeed, this article suggests that if the external actors had a hegemonic grip on the G5S-JF, the joint force’s efficiency might have continued. However, the continued efficiency would have required an endless assistance from these external actors, which is both unrealistic and unsustainable for them.

Finally, the article further suggests that for such external assistance to have a long-term impact, there needs to be an active effort from both sides to gradually transfer responsibility and accountability to the receiving side. If this is not possible, external assistance may only improve situations in the short-term and, on top of that, create challenging dependencies with long-term implications for the receiving end. More research should be encouraged in other complex conflict situations where militaries are required to work together through both coordination and direct cooperation, to understand the workings of the chain of command. Moreover, further research should also look at various dynamics of such military cooperation, both in situations where there is a colonial history with collaboration partners and where there is not. Such studies also outside the Sahel would be useful in order to understand what happens to a military’s chain of command and military efficiency when external actors become involved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marie Sandnes

Marie Sandnes is a doctoral researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and at the University of Oslo. Her research addresses military cooperation, security assistance, and counter-terrorism with a particular focus on the Sahel region and the G5 Sahel Joint Force.

Notes

1. The research for this article was conducted between 2019 and 2021. This article’s findings therefore represent external actors’ influence on the G5S-JF’s chain of command, and the relationship between the G5S-JF and external actors, prior to Mali’s withdrawal.

2. Ethics approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, case number 877,186. The interviews were done anonymously, but I have classified the interviews in five categories: 1) external security personnel (in the Sahel, but outside the G5 structure), 2) external political personnel (in the Sahel, but outside the G5 structure), 3) internal security personnel (within the G5 structure), 4) internal political personnel (within the G5 structure), and 5) observer (organizational, academic or others operating in the Sahel).

3. Author’s translation from: (Sahel Citation2021).

4. Interview 6 with external political personnel, January 10, 2020, France; Interview 13 with internal security personnel, February 6, 2020, Mali.

5. Interview 6; Interview 7 with external political personnel, January 14, 2020, France; Interview 40 with internal political personnel, March 19, 2021, Mali; Interview 44 with internal security personnel, 25 March, Mali. See also: (Lacher Citation2013).

6. Interview 34 with external security personnel, March 6, 2021, Mali; Interview 35 with observer, March 9, 2021; Interview 37 with external security personnel, March 16, 2021, Mali; Interview 40; Interview 41 with observer, March 20, 2021, Mali.

7. Interview 36 with observer, March 11, 2021, Mali.

8. Interview 37.

9. See also: (Welz Citation2022b; UN Security Council Citation2021a; Gasinska and Bohman Citation2017).

10. Interview 36.

11. Interview 34.

12. Interview 2 with external political personnel, October 2, 2019, Nigeria.

13. Interview 4 with observer, October 2, 2019, Nigeria.

14. Interview 7.

15. Interview 33 with observer, March 4, 2021, Mali; Interview 36; Interview 37.

16. Interview 33.

17. Interview 39 with external security personnel, March 18, 2021, Mali.

18. Interview 6; Interview 7; Interview 13; Interview 37.

19. Interview 29 with internal security personnel, February 23, 2020, Mali; Interview 37; Interview 44.

20. Interview 6; Interview 13.

21. Interview 10 with external security personnel, January 15, 2020, France; Interview 13; Interview 37.

22. Interview 13; Interview 37; Interview 42 with internal security personnel, March 24, 2021, Mali; Interview 44.

23. Interview 10.

24. Interview 13.

25. Ibid.

26. Interview 29.

27. Interview 29; Interview 42.

28. Interview 42.

29. Interview 29.

30. Interview 37.

31. Interview 40.

32. Interview 34; Interview 37; Interview 40.

33. Interview 27 with external security personnel, February 22, 2020, Mali; Interview 37; Interview 44.

34. Interview 37.

35. Ibid.

36. Interview 26 with observer, February 19, 2020, Mali; Interview 40.

37. Interview 26; Interview 31 with external security personnel, February 24, 2021, Mali; Interview 34; Interview 37; Interview 40.

38. Interview 37.

39. Interview 28 with internal security personnel, February 22, 2020, Mali.

40. Interview 10.

41. Interview 29.

42. Interview 29.

43. Interview 6; Interview 37; Interview 40.

44. Interview 29.

45. Interview 32 with external security personnel, February 25, 2021, Mali.

46. Interview 11; Interview 13; Interview 27.

47. Interview 42.

48. Ibid.

49. Interview 36.

50. Interview 34.

51. Interview 32; Interview 37; Interview 39; Interview 40; Interview 42. See also: (UN Security Council Citation2020).

52. Interview 32.

53. Interview 40.

54. Interview 11; Interview 37; Interview 42.

55. Interview 11.

56. For research on how Sahelian states expresses agency towards external actors, see for instance: (Frowd Citation2021; Cold-Ravnkilde Citation2021; Sandnes Citation2022).

References

- Allen, Charles D., and Grenn K. Cunningham. 2010. “System Thinking in Campaign Design.” In The U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Issues, edited by Bartholomees, J. Boone, 253–262. 4th ed. Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College.

- Auerswald, David P., and Stephen M. Saideman. 2014. “NATO in Afghanistan: Fighting Together, Fighting Alone.” In NATO in Afghanistan. Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400848676.

- AU Peace and Security Council. 2017. “‘Communiqué’. African Union.” PSC/PR/COMM(DCLXXIX). 679th meeting. https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/679th-com-g5sahel-13-04-2017.pdf.

- Bartels, Elizabeth M., Christopher S. Chivvis, Adam R. Grissom, and Stacie L. Pettyjohn. 2019. ”Conceptual Design for a Multiplayer Security Force Assistance Strategy Game.” RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2850.html.

- Bayart, Jean-François. 2000. “Africa in the World: A History of Extraversion.” African Affairs 99 (395): 217–267. doi:10.1093/afraf/99.395.217.

- Bennett, D. Scott. 1997. “Testing Alternative Models of Alliance Duration, 1816-1984.” American Journal of Political Science 41 (3): 846–878. doi:10.2307/2111677.

- Biddle, Stephen, Julia Macdonald, and Ryan Baker. 2018. “Small Footprint, Small Payoff: The Military Effectiveness of Security Force Assistance.” Journal of Strategic Studies 41 (1–2): 89–142. doi:10.1080/01402390.2017.1307745.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Charbonneau, Bruno, and Tony Chafer, eds. 2014. Peace Operations in the Francophone World. 1st ed. Oxon: Routledge.

- Clausewitz, Carl von. 1989. On War. Edited by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691018546/on-war.

- Cold-Ravnkilde, Signe Marie. 2018. A Fragile Military Response: International Support of the G5 Sahel Joint Force. Danish Institute for International Studies. https://www.diis.dk/en/research/a-fragile-military-response.

- Cold-Ravnkilde, Signe Marie. 2021. “Borderwork in the Grey Zone: Everyday Resistance Within European Border Control Initiatives in Mali.” Geopolitics 27 (5): 1–20. doi:10.1080/14650045.2021.1919627.

- Cragin, R. Kim. 2020. “Tactical Partnerships for Strategic Effects: Recent Experiences of US Forces Working By, With, and Through Surrogates in Syria and Libya.” Defence Studies 20 (4): 318–335. doi:10.1080/14702436.2020.1807338.

- Dieng, Moda, Philip Onguny, and Ghouenzen Mfondi. 2020. “Leadership Without Membership: France and the G5 Sahel Joint Force.” African Journal of Terrorism and Insurgency Research 1 (2): 21–41. doi:10.31920/2732-5008/2020/v1n2a2.

- Dijk, Ruud van, and Stanley R. Sloan. 2020. “Nato’s Inherent Dilemma: Strategic Imperatives Vs. Value Foundations.” Journal of Strategic Studies 43 (6–7): 1014–1038. doi:10.1080/01402390.2020.1824869.

- Dijkstra, Hylke. 2010. “The Military Operation of the EU in Chad and the Central African Republic: Good Policy, Bad Politics.” International Peacekeeping 17 (3): 395–407. doi:10.1080/13533312.2010.500150.

- European Council. 2020. “EUTM Mali: Council Extends Training Mission with Broadened Mandate and Increased Budget.” European Council. 23 March 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/03/23/eutm-mali-council-extends-training-mission-with-broadened-mandate-and-increased-budget/.

- Finlan, Alastair, Anna Danielsson, and Stefan Lundqvist. 2021. “Critically Engaging the Concept of Joint Operations: Origins, Reflexivity and the Case of Sweden.” Defence Studies 21 (3): 356–374. doi:10.1080/14702436.2021.1932476.

- France 24. 2022. “Mali Withdraws from G5 Sahel Regional Anti-Jihadist Force.” France 24 16 May 2022. sec. africa https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20220515-mali-withdraws-from-g5-sahel-regional-anti-jihadist-force

- Frowd, Philippe M. 2021. “Borderwork Creep in West Africa’s Sahel.” Geopolitics 27 (5, March): 1–21. doi:10.1080/14650045.2021.1901082.

- G5 Sahel. 2021. “Le Dispositif de Pilotage Du G5 Sahel’. G5 Sahel Executive Secretariat (blog).” 14March 2021. https://www.g5sahel.org/le-dispositif-de-pilotage-du-g5-sahel/.

- Gasinska, Karolina, and Elias Bohman. 2017. ”Joint Force of the Group of Five: A Review of Multiple Challenges.” FOI-R–4548–SE. Totalfåorsvarets forskningsinstitut. https://www.foi.se/rest-api/report/FOI-R–4548–SE.

- Henke, Marina E. 2017. “The Politics of Diplomacy: How the United States Builds Multilateral Military Coalitions.” International Studies Quarterly 61 (2): 410–424. doi:10.1093/isq/sqx017.

- Hope, Col. Ian. 2008. Unity of Command in Afghanistan: A Forsaken Principle of War. Carlisle PA: Strategic Studies institute.

- Ikpe, Ibanga B. 2014. “Reasoning and the Military Decision Making Process.“ Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics 2 (1): 143–160.

- International Crisis Group. 2017. ‘Finding the Right Role for the G5 Sahel Joint Force’. 258. International Crisis Group. https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/258-finding-the-right-role-for-the-g5-sahel-joint-force.pdf.

- Jahara, Matisek, and Michael W. Fowler. 2020. “The Paradox of Security Force Assistance After the Rise and Fall of the Islamic State in Syria–Iraq.” Special Operations Journal 6 (2): 118–138. doi:10.1080/23296151.2020.1820139.

- Kelly, Fergus. 2020. “Sahel Coalition: G5 and France Agree New Joint Command, Will Prioritize Fight Against Islamic State.” The Defense Post (blog). 14 January 2020. https://www.thedefensepost.com/2020/01/14/sahel-coalition-france-g5-islamic-state/.

- King, Anthony. 2021. “Operation Moshtarak: Counter-Insurgency Command in Kandahar 2009-10.” Journal of Strategic Studies 44 (1): 36–62. doi:10.1080/01402390.2019.1672160.

- King, Nigel. 2004. “Using Templates in the Thematic Analysis of Text.” In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research, edited by Cassell, Catherine and Gillian Symon, 256–270. London: Sage. http://www.sagepub.co.uk/booksProdDesc.nav?prodId=Book224800&

- Kreps, Sarah E. 2011. Coalitions of Convenience: United States Military Interventions After the Cold War. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199753796.001.0001.

- Lacher, Wolfram. 2013. “The Malian Crisis and the Challenge of Regional Cooperation”. Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 2(2). Art. 18. doi:10.5334/sta.bg.

- Layne, Christopher. 2000. “US Hegemony and the Perpetuation of NATO.” Journal of Strategic Studies 23 (3): 59–91. doi:10.1080/01402390008437800.

- Livingston, Thomas K. 2011. Building the Capacity of Partner States Through Security Force Assistance. Washington D.C: Congressional Research Service.

- Männiste, Tõnis, Margus Pedaste, and Roland Schimanski. 2019. “Review of Instruments Measuring Decision Making Performance in Military Tactical Level Battle Situation Context.” Military Psychology 31 (5): 397–411. doi:10.1080/08995605.2019.1645538.

- Marston, Daniel Patrick. 2021. “Operation TELIC VIII to XI: Difficulties of Twenty-First-Century Command.” Journal of Strategic Studies 44 (1): 63–90. doi:10.1080/01402390.2019.1672161.

- McInnis, Kathleen J. 2013. “Lessons in Coalition Warfare: Past, Present and Implications for the Future.” International Politics Reviews 1 (2): 78–90. doi:10.1057/ipr.2013.8.

- Mearsheimer, John J. 2001. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton.

- Mello, Patrick A. 2019. “National Restrictions in Multinational Military Operations: A Conceptual Framework.” Contemporary Security Policy 40 (1): 38–55. doi:10.1080/13523260.2018.1503438.

- Nicholas, Marsh, and Øystein H. Rolandsen. 2021. “Fragmented We Fall: Security Sector Cohesion and the Impact of Foreign Security Force Assistance in Mali.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 15 (5): 1–16. doi:10.1080/17502977.2021.1988226.

- Nilsson, Mikael. 2008. “The Power of Technology: U.S. Hegemony and the Transfer of Guided Missiles to NATO During the Cold War, 1953–1962.” Comparative Technology Transfer and Society 6 (2): 127–149. doi:10.1353/ctt.0.0007.

- Nilsson, Niklas. 2020. “Practicing Mission Command for Future Battlefield Challenges: The Case of the Swedish Army.” Defence Studies 20 (4): 436–452. doi:10.1080/14702436.2020.1828870.

- Relief, Web. 2017. “Challenges and Opportunities for the G5 Sahel Force - Mali | ReliefWeb.” Relief Web. 7 July 2017. https://reliefweb.int/report/mali/challenges-and-opportunities-g5-sahel-force.

- Rice, Anthony J. 1997. “Command and Control: The Essence of Coalition Warfare.” Parameters 27 (1). doi:10.55540/0031-1723.1817.

- Sahel, EUCAP. 2019. The European Union’s Partnership with the G5 Sahel Countries. EEAS. https://www.eucap-sahel.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/factsheet_eu_g5_sahel_july-2019.pdf.

- Saideman, Stephen M. 2016. “The Ambivalent Coalition: Doing the Least One Can Do Against the Islamic State.” Contemporary Security Policy 37 (2): 289–305. doi:10.1080/13523260.2016.1183414.

- Sandnes, Marie. 2022. “The Relationship Between the G5 Sahel Joint Force and External Actors: A Discursive Interpretation.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines 57 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/00083968.2022.2058572.

- Shurkin, Michael, IV Gordon John, Frederick Bryan, and G. Pernin. Christopher 2017. ”Building Armies, Building Nations: Toward a New Approach to Security Force Assistance.” RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1832.html.

- Snyder, Glenn H. 1997. Alliance Politics by Glenn H. Snyder | Hardcover. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801434020/alliance-politics/.

- UN Security Council. 2020. “Joint Force of the Group of Five for the Sahel: Report of the Secretary-General’. S/2020/1074.” UN Security Council. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/S_2020_1074.pdf.

- UN Security Council. 2021a. “Joint Force of the Group of Five for the Sahel: Report of the Secretary-General.” UN Security Council. S/2021/442. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/S_2021_442.pdf

- UN Security Council. 2021b. ”Joint Force of the Groupp of Five for the Sahel: Report of the Secretary-General.” S/2021/442. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/S_2021_442.pdf/.

- UN Security Council. 2022. “Joint Force of the Group of Five for the Sahel: Report of the Secretary-General.” S/2022/382. UN Security Council. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/S_2022_382.pdf.

- Vincent, Elise. 2022. “After Ten Years, France to End Military Operation Barkhane in Sahel’.” Le Monde, 9 November 2022. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2022/11/09/after-ten-years-france-to-end-military-operation-barkhane-in-sahel_6003575_4.html.

- Walt, Stephen M. 1990. The Origins of Alliances. Itchata and London: Cornell University Press. https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801494185/the-origins-of-alliances/.

- Webb, Michael C., and Stephen D. Krasner. 1989. “Hegemonic Stability Theory: An Empirical Assessment.” Review of International Studies 15 (2): 183–198. doi:10.1017/S0260210500112999.

- Weitsman, Patricia A. 2003. “Alliance Cohesion and Coalition Warfare: The Central Powers and Triple Entente.” Security Studies 12 (3): 79–113. doi:10.1080/09636410390443062.

- Welz, Martin. 2022a. “Institutional Choice, Risk, and Control: The G5 Sahel and Conflict Management in the Sahel.” International Peacekeeping 29 (2): 235–257. doi:10.1080/13533312.2022.2031993.

- Welz, Martin. 2022b. “Setting Up the G5 Sahel: Why an Option That Seemed Unlikely Came into Being’.” The Conversation. 11 April 2022. http://theconversation.com/setting-up-the-g5-sahel-why-an-option-that-seemed-unlikely-came-into-being-180422.

- Yarger, Richard H. 2010. “Towards a Theory of Strategy: Art Lykke and the US Army War College Strategy Model.” In The U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Issues, edited by Bartholomees, J. Boone, 45–52. 4th ed. Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College.