ABSTRACT

Local reactions to climate change and sustainable development take various forms. The literature on grassroots innovation has grown recently, and it illustrates the myriad of initiatives that are actively working with the issues. The eco-village movement is one example of a grassroots innovation that reacts and adapts to its prerequisites, all striving for an alternative living with reduced environmental impact. This paper focuses on the development of eco-villages in Sweden, arguing that in recent years a fourth generation of initiatives has emerged, with ideals close to the pioneers of the first generation’s idealistic views and ambitions for alternative living as a way of reacting to global trends. The fourth generation is highly diverse in form and goals, but with an emphasis on outreach and networking as well as more focus on small-scale agriculture and permaculture. This paper presents, through literature reviews, database searches and interviews, how the eco-village idea has moved between initiatives and has taken various forms over the generations. In the first generation via books, reports and personal contacts, in the second and third also via contractors and professionals, and in the fourth via the internet and social media in order to attract members and have impact.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Responding to climate change and achieving sustainable development have been on the agenda for several decades. A growing body of literature focuses on the role of cities in low-carbon transitions (Bulkeley, Broto, Hodson, & Marvin, Citation2011; Geels, Citation2011), experiments (Bulkeley & Castán Broto, Citation2013) and community action (Taylor Aiken, Citation2014). Community groups are increasingly engaging in climate change actions in small scales and local levels through transition movements, transition towns (Feola & Nunes, Citation2014) and grassroots innovations and movements (Hargreaves, Hielscher, Seyfang, & Smith, Citation2013; Seyfang & Haxeltine, Citation2012; Seyfang & Smith, Citation2007).

Eco-villages (EVIs) are examples of such local action. They are intentional, locally owned traditional or urban communities that address all three dimensions of sustainability (social, ecological and economic). They function as laboratories, testing innovative technical and social forms and solutions as their inhabitants adopt alternative, sustainable lifestyles. Further, as argued by Shirani, Butler, Henwood, Parkhill, and Pidgeon (Citation2015), these are spaces where non-residents can encounter alternative lifestyles, which may generate interest.

The EVI movement has a long history and an international scope. In 2011, some 500 EVIs were registered with the Global Eco-village Network (GEN), which has regional networks across the world (Network, Citation2017). This paper focuses on presenting the Swedish EVI movement and the diffusion of the ideas surrounding EVIs in Sweden. There are currently around 30 EVIs spread across the country, with varying sizes and organizational structures. The movement can be traced back to the 1970s when it was part of the ‘green wave’ counter-urbanization movement, while EVIs started in the 1980s were often associated with the anti-nuclear movement (Jamison, Eyerman, & Cramer, Citation1990). Reacting against mainstream behaviour, the individuals initiating the first EVIs were motivated by a desire for alternative and communal lifestyles and for social sustainability (Ibsen, Citation2010).

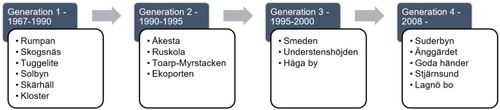

Berg, Cras-Saar, and Saar (Citation2002) argue that the development of EVIs in Sweden evolved over three generations, each with their own aims and organizational principles. The first initiatives were citizen-driven projects, with idealistic individuals taking charge and organizing projects. During the second generation (late 1980s and 1990s), construction companies were building their own versions of EVIs, while the third generation was characterized by projects with cooperation between citizens’ organizations and construction companies. This cooperation and sharing of knowledge accounts for the success of the third generation, according to Berg et al. (Citation2002).

This paper argues that we have now reached the fourth generation of EVI development in Sweden. Individuals and organizations are starting new settlements, often through mobilization on social media and other channels, and they operate within networks spanning national borders and areas of interests. This fourth generation followed a period of stagnation in the 2000s during which some EVIs abandoned key components and others started to replace once-innovative technical systems with mainstream municipal systems. This paper also provides a systematic mapping of the present state of the movement.

The literature on grassroots innovations (GI) has grown significantly in the last 10 years. Seyfang and Smith (Citation2007, p. 585) define GI as

networks of activists and organisations generating novel bottom-up solutions for sustainable development; solutions that respond to the local situation and the interests and values of the communities involved. In contrast to mainstream business greening, grassroots initiatives operate in civil society arenas and involve committed activists experimenting with social innovations as well as using greener technologies.

Recent studies on GIs have focused on social enterprises and local economies (Seyfang & Longhurst, Citation2013), community gardens and food networks (Seyfang, Citation2007), energy (Klein & Coffey, Citation2016), and the organization and prerequisites for GIs (Martin & Upham, Citation2016; Middlemiss & Parrish, Citation2010; Ornetzeder & Rohracher, Citation2013; Seyfang, Park, & Smith, Citation2013). With a few exceptions (cf. Kooij et al., Citation2018), GIs in Sweden have not been addressed in previous studies. There has also been critique of the assumptions within the GI literature, especially regarding the concept of ‘upscaling’ (cf. Schwanen, Citation2017), which will be addressed in this paper.

The aim of this paper is to analyse the evolution of the EVI movement in Sweden, in order to understand how the EVI concept has travelled between the projects, and to identify recent development trends. Two research questions guide the analysis:

How has the EVI concept been diffused in Sweden and travelled between projects?

What are the most recent trends in EVI development and how can these be explained?

Methods

The methodological approach adopted in this paper is inspired by Butzin and Widmaier’s (Citation2016) concept of innovation biography (IB). The concept addresses how knowledge is generated over time in particular settings, and how its spatiality is independent of administrative borders for the related social network’s cross-sectoral boundaries and spatial scales. An IB focuses on knowledge dynamics at the level of concrete innovations, and a time–space perspective on knowledge creation as well as understanding how innovations travel.

In this paper, I attempt to recreate the trail of the EVI concept diffusion, by identifying the continuous local adjustments and fine-tuning required to suit particular settings. Multiple sources, through a pragmatic perspective on methods and knowledge (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004), are used to trace the information flows. A pragmatic research approach means that methods should ‘be mixed in ways that offer the best opportunities for answering important research questions’ (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004, p. 16), meaning that qualitative and quantitative methods can be mixed and that approaches may be pluralistic and eclectic. This paper is not based on a mix of qualitative and quantitative data, but mixes all possible relevant sources. Empirical data were collected during the autumn of 2016 and early 2017. An initial mapping of existing EVIs was done and information was obtained about their goals, location, activities, networks and key people. The information was stored in a database and emerging EVIs were included in the database. Websites, databases, newspapers and reports of EVIs were studied along with previous research on EVIs. The approach associated with risks of resulting in asymmetry between cases, as some are better documented than others, but as the aim was to cover the process extensively and show a broader picture, the risks of biases that lead to unbalanced analysis is limited.

Thirteen interviews were carried out, focusing on EVIs that were not covered well in other sources, especially emerging and recently established ones. Interviews were used in order to gain knowledge on the EVIs that could not be obtained through written material, but one must be aware of the pitfalls of interviews. The interview is a social interaction between the researcher and the informant, which might lead to bias. When analysing the interview, one must also take into consideration that a considerable amount of time that might have passed between the event and the interview, as well as the risk of the informant overstating their own importance in the process that is the subject of the interview (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2014). This was taken into account in the analysis, along with ambitions to, as much as possible, triangulate the statements through written documents.

Three of the interviewees represented interest organizations; the national umbrella organizations for EVIs (EVO), the Transition Network and ‘Rural Sweden’. The questions in the semi-structured interviews focused on the development of the village, motives, organization, problems that had emerged, future trends and expectations. The interviews were conducted in person or over the telephone in cases where there were time and distance limitations. Kvale and Brinkmann (Citation2014) argue that telephone interviews have advantages as geographical distances are overcome, but that body language and subtle signs cannot be registered from either part. In a face-to-face interview, the researcher might let silence last longer as he or she can see that the informant is thinking and searching for an answer, and in a telephone interview the risk is that the interviewer rush past those moments. Still, for this research project, the pros of telephone interviews outweighed the cons.

Theory: grassroots innovations

Taking GI as its point of departure, this paper analyses EVIs in Sweden. Market-based innovations work within a market economy, driven by motives for profit and the companies promoting the innovations base their income on commercial activities. GIs, on the contrary, work within a social economy focused on ideological aims based on social need, and are organized in a variety of ways (voluntary associations, cooperatives and informal community groups). The resource base is grant funding, voluntary inputs, and mutual exchanges (Seyfang & Smith, Citation2007). Research has developed and expanded, covering topics such as community energy (Seyfang, Hielscher, Hargreaves, Martiskainen, & Smith, Citation2014; van Veelen, Citation2017; Walker & Devine-Wright, Citation2008), community currencies (Seyfang & Longhurst, Citation2013), food networks and community gardens (Seyfang, Citation2007; White & Stirling, Citation2013) and community leadership in energy projects (Martiskainen, Citation2017).

Developing GI projects require certain skills that go beyond the technical and administrative skills that are often found in community groups. There are also needs for social skills, confidence and emotional stamina as projects may carry on for a long time (Seyfang et al., Citation2014). Ornetzeder and Rohracher’s (Citation2013) study of successful GIs in the energy field showed that what fuels the initial drivers is not finances but the wider social discourse on sustainable energy use. Seyfang and Smith (Citation2007) argue that social and technical innovations are interrelated, especially when it comes to co-housing, which is often associated with EVIs. Co-housing can involve communal activities (planning meetings, shared tasks, shared meals), often based at a community centre. Such innovations are social rather than technical, as it restructures the social institution of housing. However, Seyfang and Smith (Citation2007) also argue that these activities open up for technical innovations, such as the use of more sustainable construction materials and designs, greywater recycling, and the pooling of resources (e.g. rainwater). In all these cases, cooperation through shared costs and efforts may lead to improvements. These characterizations are taken as starting points for the understanding of Swedish EVIs.

Hossain (Citation2016) has stated in an article reviewing the GI literature that the consensus is that GI is a bottom-up approach for sustainable development and that the main theories used are within the sociotechnical transition studies literature (cf. Geels, Citation2002; Geels & Schot, Citation2010; Smith & Raven, Citation2012), such as strategic niche management and the multi-level perspective. For an overview of this field, see Markard, Raven, and Truffer (Citation2012). According to this literature, transformative change towards sustainability is a gradually unfolding process over several decades, involving technical and non-technical elements (Markard et al., Citation2012). The multi-level perspective has been an important step in conceptualizing societal transformations based on a sociotechnical perspective. Its main claim is that changes at three different levels of structuration interact to produce fundamental transformations: sociotechnical niches, regimes and landscapes. Niches are protective spaces in which inventions evolve over time, among a few actors. The regime level comprises the dominant configuration of technical artefacts, networks, users, market structure, institutions, regulations and knowledge. These are stable configurations, making them difficult to change and disrupt. Thus, the success of innovative niches depends on possibilities to enter the stable regime level. The landscape level comprises large-scale, slowly changing external factors, such as climate change and economic trends, which influence regime actors but are beyond control of single actor groups (Geels, Citation2002, Citation2011).

Critique has been raised about some of the assumptions in the GI-literature, especially concerning the epistemological connections with the sociotechnical transitions literature. Schwanen (Citation2017) argues that sociotechnical transition studies could include literature from geographical scholars, since much of the transition literature starts out from a hierarchical ontology of scales, which could be problematized with the help of geographical perspectives.

Coenen, Benneworth, and Truffer (Citation2012) and Coenen and Truffer (Citation2012) argue that much of the sociotechnical transition studies literature needs to take space and scale into consideration to a larger extent, as institutionalized knowledge and socio-economic practice is embedded in a variety of contexts beyond the national scale, which has been seen as the main context in which regimes and niches take place. On the other hand, GI studies start out from the local contexts and communities, with an assumption of them being the lowest scale but, as argued by Bulkeley (Citation2005), the understanding of ‘scalar nesting’ needs to be reconsidered. Networks of actors, groups, institutions and organizations are rearticulating and rescaling the nature, authority and territoriality of the state, and these networks have scalar dimensions that go beyond their scope.

The geographical scholars further offer ‘alternative logics and vocabularies to the notion of up-scaling that pervades MLP-infected reasoning’ (Schwanen, Citation2017, p. 10). The success of a niche innovation and of GIs is often evaluated based on potential for replication, scaling up and growing by attracting new members and becoming mainstream (Hoppe, Graf, Warbroek, Lammers, & Lepping, Citation2015; Seyfang & Longhurst, Citation2016). The critique is based on research on communities striving towards socially just transitions, often analysed using a post-capitalist perspective, where e.g. Chatterton (Citation2016) uses the concept of ‘urban commons’ to illustrate the geography of post-capitalist transitions. He argues that ‘commons are always partial, coexisting with a myriad of other public and private forms of ownership and governance. They emerge through experimentation and risk taking in terms of embedding other values and social relations beyond capitalism’ (Chatterton, Citation2016, p. 407). Against this backdrop, the analysis of GI development could take into account how networks go beyond territorial scales and that the notion of up-scaling needs to be broadened beyond hierarchical scales.

Taylor Aiken (Citation2016) argues further that the ‘prosaic state’ through everyday tasks, decisions and evaluations, creates procedures and imposes requirements on communities, so that they can justify the use of government funding, which can affect the groups negatively. Taylor Aiken (Citation2016, p.25) argues that:

demonstration required number-justification, altering the ways of knowing and understanding preferred. Second, community became valued instrumentally rather than intrinsically. Third, and more fundamentally, these processes led to a splitting of means and ends, accompanying a crowding out of relational understandings.

GIs and community energy have not been as successful in Sweden as they have been in places like the Netherlands and Denmark (cf. Oteman, Kooij, & Wiering, Citation2017; Oteman, Wiering, & Helderman, Citation2014). Kooij et al. (Citation2018) argue that the obstacles in Sweden include the centralized energy system, including strong often publicly owned production facilities and regulated distribution networks. Strong municipalities have also played a crucial role due to their planning monopolies and ownership of energy plants.

Previous research: eco-villages

Most literature on EVIs comprises case studies focusing on their planning processes, day-to-day life and challenges, and comprehensive studies are rare. However, Barton (Citation2000) did survey 55 ‘eco-neighbourhoods’ across the world applying sustainability criteria from economic, social and environmental perspectives, and found few successful EVIs. Some have succumbed to affordability issues and many were built in sparsely populated areas. Political and bureaucratic inertia were other factors affecting their success.

Undeterred, Jackson (Citation2004, p. 26) argues that ‘the ideal eco-village does not exist. It is a work in process – a fundamental component of the new paradigm, where much is yet to be learned’. Although many EVIs have not reached their potential, the goal is to aim higher and take a different direction.

There is no comprehensive mapping of EVIs in Sweden, although Norbeck (Citation2004) studied the history, values and technical solutions of nine Swedish EVIs and she found two general trends. Firstly, knowledge of the pitfalls of different technical systems and technologies increased and was diffused through reports, conferences and personal contacts. Secondly, awareness of aesthetics had increased, as the first EVIs were idealistic and focused on reduced energy use, while later EVIs paid increasingly attention to aesthetic aspects and quality of life, in line with general trends in society.

Several studies have emphasized the roles of the pioneers in each project. Ibsen (Citation2010) stressed the pioneer knowledge and commitment at the EVI Tuggelite, which was also evident in Solbyn (Palm Lindén, Citation1998). There are examples of EVIs with lacking citizen involvement in the planning processes, leading to a reduced sense of responsibility among the ‘commoners’ (Berg et al., Citation2002; Norbeck, Citation2004). Winston (Citation2012) studied the development of Ireland’s first EVI, Cloughjordan, established in 2007, and found that the drive and enthusiasm of initial members was a crucial factor, as was diversity of skills in the various stages of the planning process. Van Schyndel Kasper (Citation2008) found that commitment to the community’s overall mission and goal was a core issue and that the pioneers often wrote the initial visions.

In many EVIs, social aspects are seen as equally important as environmental aspects. Norbeck (Citation2004) and Atlestam et al. (Citation2015) found that social interactions were often mentioned as the most important aspect of living in Swedish EVIs. Van Schyndel Kasper (Citation2008) studied eight EVIs in the United States and concluded that the reasons for initiating and moving to an EVI vary, but that longing for a community and a good atmosphere for children are common motivators. Kirby (Citation2003) studied a large-scale EVI in Ithaca, New York, with room for 200 houses, and found that different kinds of ‘connections’ were important. Connection to nature and social connections were important, specifically connection to a community and movement towards a common goal, and connections across generations. This connectedness led to a commitment to sustainability and continuity over time.

Palm Lindén (Citation1998) studied Myrstacken and Solbyn, two EVIs in Sweden, and identified two overarching ecological and social goals. Cooperation was central to both, as common decisions needed to be taken, and inhabitants were expected to adopt environmentally friendly norms and behaviours. Balancing the private and common realms was a challenge, as the residents still valued their privacy.

The evolution of Swedish eco-villages

There are various definitions of what constitutes an EVI. In 1991, the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning in Sweden developed a definition that emphasized sustainable small villages (maximum 50 households) with access to farming lots. The villages should also contain a community house, eco-friendly construction materials, building locations based on best climate practices (such as large windows on the southern side), recycling, low energy use and local sewage systems as far as possible (Boverket, Citation1991). One reason for developing this definition was to help EVI projects obtain loans, for they were often met with scepticism from banks (TT, Citation1991).

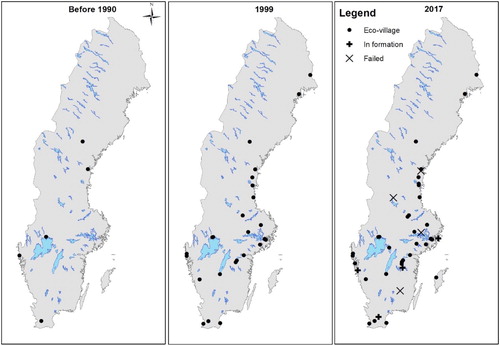

The communities range from small rural EVIs to urban settlements. shows the 30 or so existing EVIs spread across Sweden, which can be compared to around 50 in Denmark, around 15 in Finland and 23 in Russia (Ecovillages Project, Citation2018); Trust, Citation2018). shows how the EVIs have developed in Sweden, that there are at least four EVIs in formation, and at least four failed projects.

The identified EVIs in Sweden can be found in , most of which were established in the 1990s. They vary in size from only a few households to around 50. The most recently developed villages are also the smallest, but they all aim to attract new members, in order to develop the EVI with more projects and create a larger community.

Table 1. Information about Swedish eco-villages.

There are substantial differences in prioritized activities between the EVIs. Some would, arguably, fall outside the definition if social aspects were seen as crucial, as the only thing left of the EVI ideas are the buildings. This will be further discussed below.

Four generations of eco-villages

In the next section, four generations of EVIs are analysed in light of societal trends that affected their development. The origins of the initiatives, their motives and how knowledge and ideas were diffused, are also described.

The most prominent cases in each generation are visualized in . It should be noted that such division is never clear-cut as the development is a fluid process and there are overlaps in terms of time.

First-generation EVIs

The first generation of EVIs, as defined by Berg et al. (Citation2002), includes Rumpan, Skognäs, Tuggelite, Solbyn and Skärhäll. The key pioneers at these EVIs were influenced by other movements such as the ‘green wave’ (Jamison et al., Citation1990), the increased environmental awareness generated by for example Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and, as in the case of Tuggelite, the anti-nuclear movement (Ibsen, Citation2010; Atlestam et al., Citation2015, interview Solbyn 2016). The exception is Skärhäll, which started as an artists’ village and only later adopted ecological ideas (Atlestam et al., Citation2015).

These first EVIs were rooted in strong idealism but, as argued by Berg et al. (Citation2002), some had poorly developed technological systems and inadequate organization. Municipalities located them on the outskirts of cities, which on the one hand meant a nice living environment close to nature, but on the other hand led to large distances to service and thus car dependency. The projects were started by environmentally concerned citizen groups, inspired by global discourses (Atlestam et al., Citation2015).

A group of researchers in a cross-disciplinary research group at the University of Gothenburg were the pioneers in the Tuggelite project in the 1970s. They argued that government housing policy, as exemplified in the modernistic inspired Million Programme, was unsustainable, especially as regards energy use. Instead, they strove for ‘alternative living along the visions of “small is beautiful” in combination with new advanced technical methods that kept down the use of energy without compromising comfort’ (Ibsen, Citation2010, p. 132). Their ideas were published in a report, called the Välsviken Project, which inspired other citizen groups in Sweden. Along with new, efficient technical systems, social life was emphasized (Ibsen, Citation2010), which resonates with Seyfang and Smith’s (Citation2007) argument that social and technical innovations are interlinked and generate synergies.

Skill levels among the pioneers were often high, as they were academics applying theoretical knowledge to practical matters and using their networks when skills were insufficient. The involvement of architect Krister Wiberg was crucial in the Solbyn project as he had knowledge of sustainable house construction and he was later involved in several other projects (Atlestam et al., Citation2015, interview Solbyn 2016). Knowledge transfer took place between the projects via the Välsviken report and Wiberg, mainly focusing on the technical components and design of the villages (Oredsson, Citation2011, interview Solbyn 2016; Solbyn, Citation2017). There were also contact between the EVIs, and they learned from each other’s mistakes, and then formed their own versions (Svane & Wijkmark, Citation2002). The project pioneers were in the centre of the developments, but the housing association HSBFootnote1 was also highly involved, which will be discussed further below.

Innovations often face resistance from mainstream actors and structures, and all EVIs have wrestled with daunting planning processes and bureaucracy. Tuggelite, for example, encountered Nimbyism from neighbouring homeowners. The opposition was based on aesthetics, discomfort with composting toilets and increased car traffic, and Ibsen (Citation2010) argues that individualism and prejudice were the underlying causes of these objections.

Second-generation EVIs

Berg et al. (Citation2002) argue that a second generation of EVIs commenced in the early 1990s. These initiatives came from entrepreneurs rather than citizen groups, and municipalities and politicians showed interest, particularly due to the Agenda 21 work that had started in municipalities. The financial crisis seriously affected the building sector, bringing several projects to a halt or creating tensions (Atlestam et al., Citation2015). By this point, the concept of EVIs had gained momentum and a general trend towards ecological building had emerged, as evidenced by the fact that entrepreneurs borrowed the concept to make their own versions. Knowledge gained from the initial projects was diffused and became part of a general trend of generic knowledge on energy efficient construction.

It is important to stress the role of municipalities in the different generations of EVIs. In the first generation, Tuggelite got substantial support from the municipality: help with finding the land and financial support (Ibsen, Citation2010). Myrstacken in Malmö was started by the municipality, together with HSB, as part of the Agenda 21 work, but also as a direct inspiration from the Solbyn-project in neighbouring Lund (Palm Lindén, Citation1998). In the Understenshöjden-project, in the suburbs of Stockholm, the municipality was on board at an early stage, both supporting the project and working at a high pace getting the detailed area plan accepted (Svane & Wijkmark, Citation2002).

One problem in the second generation of EVIs was that future residents were either not involved at all or came into the project late (Atlestam et al., Citation2015). Projects like Lillkyrka, Lövåsen and Orsa failed because of a lack of knowledge or a failure to connect with the EVI movement (Berg et al., Citation2002; Wiberg, Citation1991). One of the more high-profile projects at the time was Åkesta outside Västerås, started by a citizen group inspired by Tuggelite and Solbyn. However, the project became politicized and was taken over by a building company that wanted to finish the project in time for a building fair in 1990. The original ideas of the citizen group were thus not implemented, and an attempt was made to make the houses more aesthetically appealing than in the past, but this imposed financial strains. These were exacerbated by the economic recession (Atlestam et al., Citation2015). Similar problems plagued the development of Myrstacken, with high aesthetic goals, resulting in higher costs (Palm Lindén, Citation1998).

The low-resource technical solutions were implemented in these projects, although sometimes flawed or suboptimal as in Åkesta (Berg et al., Citation2002), but social aspects were neglected. However, the fact that the entrepreneurs were inspired by earlier EVIs is important and shows that knowledge transfer took another form, passing through people, professionals and organizations in parallel with books and technical reports.

Third generation

The 1990s third-generation projects, like Understenshöjden in Stockholm, Smeden in Jönköping and Hågaby in Uppsala, were built closer to city centres and the planning process contained closer connections between construction companies and the citizen groups. Berg et al. (Citation2002) argue that they took advantage of lessons learnt over the previous 25 years and developed technological systems and construction processes further.

Several key organizations and persons can be identified in relation to the transfer of knowledge and ideas. HSB built Solbyn, Myrstacken and Understenshöjden and later implemented components from the EVI projects in some of their conventional houses (HSB, Citation2017) and Wiberg continued to design eco-friendly housing around Sweden. Traditional study visits played an important role for knowledge transfer, for example for Hultabygden which took inspiration from and created their own version of the sewage system in Smeden (interview Hultabygden Citation2017).

It should, however, be mentioned that the impact from the third-generation projects outside of the EVI niche has been limited. The literature (cf. Berg, Citation2004; Berg et al., Citation2002; Svane & Wijkmark, Citation2002) often stresses the importance of the successful cooperative planning and construction processes, but later EVI projects, or other conventional projects, have not followed that model.

Stagnation

Between 2001 and 2007, no new EVIs were established and several existing EVIs abandoned their technical systems; for instance, several replaced urine-separating toilets with conventional ones. Ekoporten in Norrköping was originally owned by the municipal housing corporation but was sold to a private company which removed the urine-separating toilets for cost reasons (SR, Citation2006). Instead of looking for new solutions, the EVIs have connected to municipal systems, which happened in Hågaby (Nilsson, Citation2010), Solbyn (interview Solbyn Citation2017), Tuggelite (Strinnholm, Citation2011) and Åkesta (Atlestam et al., Citation2015). Åkesta was restructured and abandoned guiding principles of social cooperation, small-scale farming and cooperative ownership (Atlestam et al., Citation2015). Åsen outside Härnösand had financial problems and the houses became individually owned (interview Åsen Citation2017).

More of the initial ideals have been contested in some of the projects. When original tenants leave, it puts pressure on the original principles (Baas, Magnusson, & Mejía-Dugand, Citation2014; interview Solbyn Citation2017). However, as argued by Van Schyndel Kasper (Citation2008), the guiding principles and visions of the pioneers may well need to be regularly adjusted and revised in order to keep the community strong. For example, in Solbyn, the size of the EVI meant that new residents did not get to know each other as well as the initial group of people had done. Some of the new residents also had different ideals and environmental interests, which made cooperation more difficult (interview Solbyn Citation2017).

The findings of Baas et al. (Citation2014), show that residents in EVIs struggled with their self-image and feelings that they are being overtaken by the mainstream. Biomass heating and sorting household waste were unconventional when the EVIs were first established but are now standard practices. The former owner of Åsen insists that this should not be a problem:

The eco-village still lives in people’s minds; it’s rather a relational thing. If you build houses today, they are well insulated. We were just 15 years ahead of our time. […] Those who live there probably do not think they live in an eco-village, they flush their toilets like everyone else. (Interview Åsen Citation2017)

Some communities, such as Gebers (an apartment building in southern Stockholm) have dealt with severe disputes between the residents. A by-law at Gebers limited the selling price of flats to a sixth of the market price in order to keep prices affordable. Residents who wanted to sell at market price took the case to court. They lost, but the acrimony created a bad atmosphere (Stigfur, Citation2016). This is yet another illustration of how changed ideals can lead to strained relationships in the communities.

Fourth generation

Since 2008, the EVI movement has regained some momentum and at least 10 new EVIs have been founded or been in formation during this time.

The explanation for this resurgence is arguably the global trend towards greater climate awareness, which particularly affected Sweden in 2008–2009, around the time of the 2009 Copenhagen Climate Change Conference (Anshelm, Citation2012). The Transition Movement started in 2006, and the Swedish branch started in 2009 (Sykes, Citation2017). In the same period, internet usage increased, and forums, blogs and other social media relating to EVIs emerged.

These recent EVI initiatives were initiated by citizen groups without the backing of construction companies. They are diverse in form and organization, more so than earlier EVIs. The established ones, such as Suderbyn, Goda Händer, Stjärnsund, Lagnö Bo and Änggärdet are located in rural areas and several started around a small farm, purchased by an individual who would then invite others to join them, either through membership of an ‘incorporated association’ or by sales of lots. These units are smaller in terms of residents compared to earlier EVIs, sparking discussion about whether they can be categorized as EVIs, but the main ideas are the same: sustainability, community, shared work and innovative technical solutions. It is also common for these projects to have a greater focus on agriculture and permaculture than several of the previous ones. (Atlestam et al., Citation2015; interview ERO Citation2017; interview Fjälla Citation2017, interview Grönbo 2017; interview Stjärnsund Citation2017, interview Suderbyn 2017).

These new projects are networked to a larger extent than previous generations. Suderbyn on the island of Gotland is probably the most prominent case. It takes advantage of various kinds of international grants, and gets help from volunteers (interview Suderbyn 2017) as did Goda Händer (Atlestam et al., Citation2015). Several of the EVI projects are tightly connected to the permaculture movement and transition network, as well as taking a lot of inspiration from international EVIs (interview ERO Citation2017; interview Stjärnsund Citation2017, interview Suderbyn 2017). Obtaining international inspiration and developing networks is easier for the new EVIs compared with earlier ones, thanks to information sharing on internet blogs and forums.

For example, Hållkollbo, a new initiative in Stockholm, uses its website and social media to disseminate information and attract interest (interview Hållkollbo Citation2017), Stjärnsund sees mass media as an important outreach tool (interview Stjärnsund Citation2017) and Suderbyn has a similar approach of reaching out nationally and internationally through media and social media (interview Suderbyn 2017).

The permaculture trend is strong among the new EVIs like Suderbyn, Goda Händer, Stjärnsund, Fjälla, Grönbo (Atlestam et al., Citation2015; interview ERO Citation2017; interview Fjälla Citation2017, interview Grönbo 2017; interview Stjärnsund Citation2017, interview Suderbyn 2017):

I would say that there’s an explosion if you look at permaculture and interest in it. When we started five years ago, maybe two farms in Sweden claimed that they were doing permaculture on the website for WWOOF [World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farming] and today I think there might be 20 or so. (Interview, Stjärnsund Citation2017)

Stjärnsund has also developed its own currency. It has social goals as the residents exchange services such as babysitting and massages. By trading their skills, the members can afford things that might be considered luxuries (interview Stjärnsund Citation2017; cf. Seyfang & Longhurst, Citation2013).

Knowledge from early EVIs has been transferred to new projects like Lagnö bo, a multi-dwelling building on the outskirts of Trosa with a cooperative ownership structure and along with several other EVI features. Inspiration for technical systems, building techniques, and materials and design was gathered from Smeden and Baskemölla (interview Lagnö bo Citation2017). The pioneers at Suderbyn preferred to use existing EVIs like Gebers and Solbyn as benchmarks when taking the next step for EVIs (interview Suderbyn 2017). The national organization for EVIs was restarted in 2012, with several of the new EVIs as members. Knowledge exchange takes place through the organization, as well as through membership of the national permaculture association or the transition movement (interview ERO Citation2017).

Concluding discussion

The aim of this paper has been to analyse the evolution of the EVI movement in Sweden in order to understand how the EVI concept has been transferred between projects. Further, the aim has been to identify recent development trends. First of all, I have argued that the EVI movement in Sweden has reached its fourth generation, according to the characterization of Berg et al. (Citation2002). The first three generations have been different in terms of organization and project management, but a lineage of knowledge exchange can be seen between projects and generations, which can be traced by following the EVI concept via an IB approach (Butzin & Widmaier, Citation2016).

Knowledge has travelled in different forms. Initially, the exchange took place through books, reports, study visits and other contacts, and then each village created its own version. The movement gathered momentum in the 1990s, inspiring several new projects and knowledge of the EVI movement became more widespread and part of a broader trend. Knowledge exchange took place by way of the housing association HSB, which was involved in several of the projects, and through key professionals, such as the consultants and architects involved. In the fourth generation, all previous forms of knowledge transfer take place, but social media, internet forums and blogs are a significant additional factor in the circulation of ideas and knowledge today. However, the pioneer projects are still seen as benchmarks.

After a period of stagnation during most of the 2000s, a new wave emerged around 2008 and today there are several new projects under way. Many are modest in size, but their idealism is similar to that seen in first-generation EVIs. They have been started by citizen groups with a strong focus on agriculture and rural development. The new project groups are networked worldwide, and include volunteer programmes and knowledge sharing. These trends are closely linked to an increasing awareness of climate change and interest in permaculture as part of resource-efficient living.

Sweden has a history of centralized energy production and, as a result, the development of GIs in energy is limited (cf. Magnusson & Palm, Citationin press). However, the EVIs are examples of initiatives that are more closely connected to the GI movement as described in the international literature (Seyfang, Citation2007; Seyfang & Haxeltine, Citation2012). Nevertheless, in regards to the critique raised concerning some of the assumptions in the GI literature (Chatterton, Citation2016; Schwanen, Citation2017; G Taylor Aiken, Citation2016), this study does raise some questions concerning the notion of ‘up-scaling’. The EVI movement in Sweden is still small; it is a peripheral phenomenon that gains interest due to the alternative framing, but over these years, its growth must be seen as modest. The rapid development in the 1990s slowed down, and today there are around 30 initiatives. So judging by the numbers alone, it is questionable whether there has been an ‘up-scaling’. If up-scaling should be measured in terms of knowledge sharing outside the villages, it is obviously more difficult to fully prove causality. It is at least striking that the third generation of EVIs, with planning processes involving larger networks of actors, has not been diffused widely. The few examples often mentioned are still unique within their categories, despite the organization form showing great potential. If success is measured based on up-scaling as used in the GI literature, or sociotechnical transitions studies, the Swedish EVI movement may well be seen as a stagnating outlier. However, moving beyond those measurements, as argued by Chatterton (Citation2016), the non-hierarchical networks formed by the movement contribute in other ways. Qualitative aspects, such as ‘caring, nurturing, solidarity as well as the risky and process-based approaches to transitions can be over-looked, but they are at the heart of post-capitalist transitions’ (Chatterton, Citation2016, p. 411). The fourth-generation EVIs are created in horizontal networks, without involvement from professional actors, but with highly engaged enthusiasts. The knowledge sharing between projects shows how ideas flow in non-hierarchical networks and inspire action beyond spatial borders and ‘levels’.

Much of the research shows that financing is often supplemented by subsidies and grants, which is also the case in Sweden, and Taylor Aiken (Citation2016) argues that the formalization might be counterproductive as it leads to modified logics and number-justifications. On the one hand, the fact that EVIs acquired a definition given by the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning helped projects get funding and loans, and thus the formalization helped the projects move forward. On the other hand, all projects have expressed obstructions due to bureaucracy and inflexible planning processes. This is, however, always the case when new ideas and innovations emerge, and those that find a way to navigate and make good use of the systems might turn the formal processes into an advantage by applying broadly for funding and making good use of networks.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on the paper as well as the research group TEVS and the Geography Network at Linköping University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. A member-owned housing association with 600,000 members.

References

- Anshelm, J. (2012). Kampen om klimatet : miljöpolitiska strider i Sverige 2006-2009. Storå: Pärspektiv.

- Atlestam, G., Bremertz, M., Haglind Ahnstedt, C., Havström, M., Hedberg, M., Hultén, E.-L., & Höglund, C.-M. (2015). Ekobyboken – frihetsdrömmar, skaparglädje och vägar till ett hållbart samhälle. Karlstad: Votum & Gullers.

- Baas, L., Magnusson, D., & Mejía-Dugand, S. (2014). Emerging selective enlightened self-interest trends in society: Consequences for demand and supply of renewable energy. Report LIU-IEI-R, 204, Linköping University.

- Barton, H. (Ed.) 2000. Sustainable communities: The potential for eco-neighbourhoods. London: Earthscan.

- Berg, P. G. (2004). Sustainability resources in Swedish townscape neighbourhoods: Results from the model project Hågaby and comparisons with three common residential areas. Landscape and Urban Planning, 68(1), 29–52. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2046(03)00117-8

- Berg, P. G., Cras-Saar, M., & Saar, M. (2002). Living dreams: om ekobyggande-en hållbar livsstil. Nyköping: Scapa.

- Boverket. (1991). Ekobyar. Karlskrona: Boverket.

- Bulkeley, H. (2005). Reconfiguring environmental governance: Towards a politics of scales and networks. Political Geography, 24(8), 875–902. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.07.002

- Bulkeley, H., Broto, V. C., Hodson, M., & Marvin, S. (2011). Cities and low carbon transitions. New York, USA: Routledge.

- Bulkeley, H., & Castán Broto, V. (2013). Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(3), 361–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00535.x

- Butzin, A., & Widmaier, B. (2016). Exploring territorial knowledge dynamics through innovation biographies. Regional Studies, 50(2), 220–232. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.1001353

- Chatterton, P. (2016). Building transitions to post-capitalist urban commons. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 41(4), 403–415. doi: 10.1111/tran.12139

- Coenen, L., Benneworth, P., & Truffer, B. (2012). Toward a spatial perspective on sustainability transitions. Research Policy, 41(6), 968–979. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.014

- Coenen, L., & Truffer, B. (2012). Places and spaces of sustainability transitions: Geographical contributions to an emerging research and policy field. European Planning Studies, 20(3), 367–374. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.651802

- Ecovillages Project. (2018). Om ekobyar. Retrieved from http://www.balticecovillages.eu/sv/om-ekobyar

- Feola, G., & Nunes, R. (2014). Success and failure of grassroots innovations for addressing climate change: The case of the transition movement. Global Environmental Change, 24, 232–250. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.11.011

- Geels, F. W. (2002). Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Research Policy, 31(8), 1257–1274. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00062-8

- Geels, F. W. (2011). The role of cities in technological transitions: Analytical clarifications and historical examples. In H. Bulkeley, V. Castán Broto, M. Hodson, & S. Marvin (Eds.), Cities and low carbon transitions (pp. 13–28). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Geels, F. W., & Schot, J. (2010). A multi-level perspective on transitions. In J. Grin, J. Rotmans, & J. Schot (Eds.), Transitions to sustainable development – new directions in the study of long term transformative change (pp. 18–28). New York, NY: Routledge.

- GEN. (2017). About GEN. Retrieved from https://ecovillage.org/global-ecovillage-network/about-gen/.

- Hargreaves, T., Hielscher, S., Seyfang, G., & Smith, A. (2013). Grassroots innovations in community energy: The role of intermediaries in niche development. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 868–880. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.008

- Hoppe, T., Graf, A., Warbroek, B., Lammers, I., & Lepping, I. (2015). Local governments supporting local energy initiatives: Lessons from the best practices of Saerbeck (Germany) and Lochem (The Netherlands). Sustainability, 7(2), 1900–1931. doi: 10.3390/su7021900

- Hossain, M. (2016). Grassroots innovation: A systematic review of two decades of research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 137, 973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.140

- HSB. (2017). HSBs historia. Retrieved from https://www.hsb.se/om-hsb/historia/

- Ibsen, H. (2010). Walk the talk for sustainable everyday life: Experiences from eco-village living in Sweden. In P. Söderholm (Ed.), Environmental policy and household behaviour: Sustainability and everyday life (pp. 129–148). London: Earthscane.

- Jackson, R. (2004). The ecovillage movement. Permaculture Magazine, 40, 25–30.

- Jamison, A., Eyerman, R., & Cramer, J. (1990). The making of the new environmental consciousness: A comparative study of environmental movements in Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands (Vol. 1). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033007014

- Kirby, A. (2003). Redefining social and environmental relations at the ecovillage at Ithaca: A case study. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(3), 323–332. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00025-2

- Klein, Sharon J. W., & Coffey, Stephanie. (2016). Building a sustainable energy future, one community at a time. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 60, 867–880. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.01.129

- Kooij, H.-J., Oteman, M., Veenman, S., Sperling, K., Magnusson, D., Palm, J., & Hvelplund, F. (2018). Between grassroots and treetops: Community power and institutional dependence in the renewable energy sector in Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands. Energy Research & Social Science, 37, 52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.019

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2014). Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Magnusson, D., & Palm, J. (in press). Come together – historic development of Swedish energy communities. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions.

- Markard, J., Raven, R., & Truffer, B. (2012). Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Research Policy, 41(6), 955–967. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.013

- Martin, C. J., & Upham, P. (2016). Grassroots social innovation and the mobilisation of values in collaborative consumption: A conceptual model. Journal of Cleaner Production, 134, 204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.04.062

- Martiskainen, M. (2017). The role of community leadership in the development of grassroots innovations. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 22, 78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2016.05.002

- Middlemiss, L., & Parrish, B. D. (2010). Building capacity for low-carbon communities: The role of grassroots initiatives. Energy Policy, 38(12), 7559–7566. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2009.07.003

- Nilsson, A. (2010, January 15). Håga ekoby – något utöver det vanliga. Fria Tidningar.

- Norbeck, M. (2004). Individual community environment: Lessons from nine Swedish eco-villages. Retrieved from http://www.ekoby.org/

- Oredsson, S. (2011, July 15). Minnesord Krister Wiberg Arkitekten bakom Solbyn i Dalby. Sydsvenskan, p. 17.

- Ornetzeder, M., & Rohracher, H. (2013). Of solar collectors, wind power, and car sharing: Comparing and understanding successful cases of grassroots innovations. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 856–867. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.12.007

- Oteman, M., Kooij, H.-J., & Wiering, M. A. (2017). Pioneering renewable energy in an economic energy policy system: The history and development of Dutch grassroots initiatives. Sustainability, 9(4), 550. doi: 10.3390/su9040550

- Oteman, M., Wiering, M., & Helderman, J.-K. (2014). The institutional space of community initiatives for renewable energy: A comparative case study of the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. Energy, Sustainability and Society, 4(1), 11. doi: 10.1186/2192-0567-4-11

- Palm Lindén, K. (1998). Ekologi och vardagsliv: en studie av två ekobyar: slutrapport (Vol. 198). Stockholm: AFR, Naturvårdsverket.

- Schwanen, T. (2017). Thinking complex interconnections: Transition, nexus and geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 43, 1–22. doi:10.1111/tran.12223

- Seyfang, G. (2007). Growing sustainable consumption communities: The case of local organic food networks. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 27(3/4), 120–134. doi: 10.1108/01443330710741066

- Seyfang, G., & Haxeltine, A. (2012). Growing grassroots innovations: Exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Environment and Planning-Part C, 30(3), 381. doi: 10.1068/c10222

- Seyfang, G., Hielscher, S., Hargreaves, T., Martiskainen, M., & Smith, A. (2014). A grassroots sustainable energy niche? Reflections on community energy in the UK. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 13, 21–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2014.04.004

- Seyfang, G., & Longhurst, N. (2013). Growing green money? Mapping community currencies for sustainable development. Ecological Economics, 86, 65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.11.003

- Seyfang, G., & Longhurst, N. (2016). What influences the diffusion of grassroots innovations for sustainability? Investigating community currency niches. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 28(1), 1–23. doi: 10.1080/09537325.2015.1063603

- Seyfang, G., Park, J. J., & Smith, A. (2013). A thousand flowers blooming? An examination of community energy in the UK. Energy Policy, 61, 977–989. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2013.06.030

- Seyfang, G., & Smith, A. (2007). Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environmental Politics, 16(4), 584–603. doi: 10.1080/09644010701419121

- Shirani, F., Butler, C., Henwood, K., Parkhill, K., & Pidgeon, N. (2015). ‘I’m not a tree hugger, I’m just like you’: Changing perceptions of sustainable lifestyles. Environmental Politics, 24(1), 57–74. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2014.959247

- Smith, A., & Raven, R. (2012). What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Research Policy, 41(6), 1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012

- Solbyn. (2017). Om Solbyn. Retrieved from http://www.solbyn.org/about.html

- SR. (2006). Privat hyresvärd har kopplat bort miljövänliga toaletter. Retrieved from https://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=160&artikel=934491

- Stigfur, S. (2016, September 17). Drömmar gick i kras för pionjärerna i Orhem. Tidningen Farsta/Sköndal.se.

- Strinnholm, S. (2011, August 11). Tuggelite – fortfarande ekologiskt. Värmlands Folkblad.

- Svane, Ö, & Wijkmark, J. (2002). När ekobyn kom till stan: lärdomar från Ekoporten och Understenshöjden (Vol. T1:2002). Stockholm: Formas.

- Sykes, A. (2017, June 19). Nu bildas nationellt omställningsråd. Landets Fria.

- Taylor Aiken, G. (2014). Common sense community? The climate challenge fund’s official and tacit community construction. Scottish Geographical Journal, 130(3), 207–221. doi: 10.1080/14702541.2014.921322

- Taylor Aiken, G. (2016). Prosaic state governance of community low carbon transitions. Political Geography, 55, 20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.04.002

- Trust, G. (2018). Danish ecovillage network. Retrieved from http://gaia.org/global-ecovillage-network/danish-ecovillage-network/

- TT. (1991, August 20). Ny definition på ekobyar ger chans till bostadslån. TT.

- Van Schyndel Kasper, D. (2008). Redefining community in the ecovillage. Human Ecology Review, 15(1), 12–24.

- van Veelen, B. (2017). Making sense of the Scottish community energy sector – an organising typology. Scottish Geographical Journal, 133(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1080/14702541.2016.1210820

- Walker, G., & Devine-Wright, P. (2008). Community renewable energy: What should it mean? Energy Policy, 36(2), 497–500. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2007.10.019

- White, R., & Stirling, A. (2013). Sustaining trajectories towards sustainability: Dynamics and diversity in UK communal growing activities. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 838–846. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.06.004

- Wiberg, K. (1991). Generalregler. Tidskrift för Arkitekturforskning, 4(2), 100–102.

- Winston, N. (2012). Chapter 5 Sustainable housing: A case study of the Cloughjordan eco-village, Ireland. In A. Davies (Ed.), Enterprising communities: Grassroots sustainability innovations (Vol. 9, pp. 85–103). Bingley: Emerald Group.

- Interviews

- ERO – Ekobyarnas riksorganisation, member board of directors, 2017-10-04

- Fjälla ekoby, founders, 2017, 2017-10-02

- Gröbo ekoby, member board of directors, 2017-10-06

- Hela Sverige ska leva, member board of directors, 2016-10-15

- Hultabygden, founder, 2017-10-01

- Hållkollbo, member board of directors, 2017-09-16

- Lagnö bo, founders, 17-12-21

- Omställning Sverige, former chariman, 16-10-14

- Solbyn, chairman, 170103

- Solbyn, member energy group, 2017-01-11

- Stjärnsund, founder, 17-01-19

- Suderbyn, founder, 16-12-14

- Åsen, founder, 17-09-08