ABSTRACT

The paper presents a summary biographical history of those persons who have held the title Geographer Royal or a variant since its inception in 1682. The distinction can be made between individuals who held the title because of their personal standing and geographical accomplishments, and those, principally map makers and geographical publishers, who held the title as a reflection of excellence in the commercial production of maps and atlases. The honorific Geographer Royal or equivalent illustrates the importance of royal patronage and the public recognition of geography’s commercial outputs. Neither topic is addressed in existing histories of geography.

Introduction

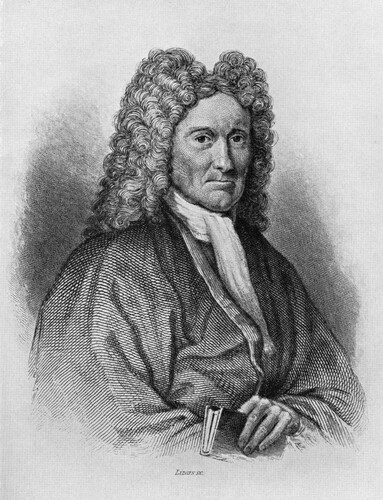

This paper presents a summary biographical history of those persons who have held the title Geographer Royal or variants of it. The first such position, that of Geographer Royal for Scotland, was created in 1682. The first to hold that title was the chorographer, physician, and natural philosopher Sir Robert Sibbald (see ). Including the present incumbent, Professor Jo Sharp of the University of St Andrews, only four other persons since Sibbald have held the title ‘Geographer Royal for Scotland’ or the related ‘Her Majesty’s Geographer for Scotland’. A further nine persons have held related titles such as ‘Geographer to His [or ‘Her’] Majesty.’ The title has either related directly and alone to Scotland or, as ‘Geographer to Her Majesty’ and similar variants, to Britain as a whole: there has never been a ‘Geographer Royal for England’.

Figure 1 Sir Robert Sibbald (1641–1722), first Geographer Royal for Scotland, the King’s Physician and founder of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

The distinction (not always clearly defined) should be noted between those who held the position by virtue of their individual academic standing and those who were appointed because of the quality of their commercial work, usually as part of a firm or company, either and most commonly as a map maker and cartographer, or as a geographical publisher. There are parallels in this respect with the position of ‘Géographe du Roi’, sometimes ‘Premier Géographe du Roi’, the titles held by leading geographers and map makers in pre-Revolutionary France such as Guillaume Delisle (1675–1726) and Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville (1697–1782). Probably because of the variability of surviving source materials – no official record has been kept of the position or of the criteria for appointment – no full study exists of the role of Geographer Royal or equivalent honorific either for Britain or for France (for some work in this direction see Heffernan, Citation2014; Withers, Citation1996; Citation2001, pp. 69–96).

This summary presents for the first time a listing of those who have held the position of Geographer Royal or equivalent. In doing so, it illuminates two related themes in geography’s history: the role of individual and institutional royal patronage, and geography’s civic and public commercial status, in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries especially. Neither theme is covered in those histories of British geography whose focus is on institutional origins, national narratives, or developments within the ‘discipline’ of geography (see, for example, Dunbar, Citation2001; Johnston, Citation2003; Livingstone, Citation1992; Withers, Citation2010).

The Geographers Royal since 1682

The life and work of those who have held the title Geographer Royal for Scotland or equivalent since 1682 is summarised in . From its establishment in 1682 until the post was held by James Wyld Senior in the 1830s, the title was awarded to individual geographers, initially in Scotland, in recognition of their geographical scholarship and publication: regional descriptions of Scotland in the case of Sibbald; maps of Scotland for Adair, and, for the London-based Thomas Jeffreys and William Faden both of whom were Geographer to the King, texts and maps. The decision to establish the post within the Royal Household probably reflected Charles II’s and, later, James VII and II’s desire to have regional descriptions of his kingdom. Sibbald’s joint appointment as the King’s Physician was a mark of Sibbald’s expertise as a physician. Both Adair and Sibbald undertook geographical work on behalf of the Scottish Parliament before its dissolution in 1707. John Ogilby, chorographer, map maker (and sometime theatre manager in Dublin where he was ‘Master of the King’s Revels’) was recorded as the ‘King’s Geographer’ before Sibbald, but the only official title afforded him was that of ‘Cosmographer and Geographick Printer’ to King Charles II in May 1674.

Table 1. The geographers royal or related titles, 1682 to the present.Table Footnote†

From James Wyld Senior to Thomas Brumby Johnston, the award was made in recognition of the high quality of commercially oriented geographical publication, principally maps and atlases. The association between royal patronage and geography in the century from 1830 reflects the strong connections between the Royal Geographical Society, the Royal Scottish Geographical Society (after 1884), the map trade, and geographical publishing (Herbert, Citation1983). This is especially the case for Alexander Keith Johnston and his brother Thomas Brumby Johnston. After a lapse following George Harvey Johnston’s appointment, the award was reinstated with an emphasis upon individual scholarship and academic standing with the appointment in September 2015 of Charles Withers and, in April 2022, of Jo Sharp, the first woman to hold the title.

The distinction between the recognition of individual esteem and of institutional excellence in a company’s commercial geographical output is as noted not easily drawn, especially in the later eighteenth century and for those who held the position Geographer Royal or Geographer to His or Her Majesty after 1830. Thomas Jefferys, who was apprenticed to the leading map maker Emanuel Bowen, and William Faden were distinguished individual map makers and, in Faden’s case, a geographical author. Both were closely involved in the ‘public map world’ of map making, publishing, and associated trades in late-eighteenth-century London and Paris (Pedley, Citation2005). And even some of those individuals honoured earlier for their work, such as John Adair, were principally map makers: the Scottish Parliament’s Act of June 1686, ‘In Favours of John Adair, Geographer, for Surveying the Kingdom of Scotland, and Navigating the Coasts and Isles thereof’ is testament to this (Withers, Citation2001, p. 92). Politically motivated (and under-funded) as it was, Adair’s coastal mapping of Scotland was of high quality but never completed (Moore, Citation2000).

There is no consistent evidence about the warrant of appointment. The honorific was given as a reflection of geographical work rather than as a stimulus to it. There was no requirement that the incumbent’s work had of necessity to be maps, books, or geographical descriptions, for example, or in the case of the earlier Geographers Royal, to serve the needs of the Scottish state. Geographical work of different sorts was recognised and patronised by the award, but it was not driven by Royal command. At one time or another, Adair held the title ‘Surveyor of the Shires’, ‘Hydrographer Royal’, ‘Geographer to the King’, ‘Geographer for Scotland’, and ‘The Queen’s Geographer in these Parts’ [Scotland]. His work was both helped and hindered by his predecessor, Robert Sibbald. The two worked together on aspects of Scotland’s geography, Sibbald terming Adair a ‘skilful mechanick’ for his map work, but they later fell out over contractual matters. Adair may have owed his preferment to the fact that Sibbald’s 1682 appointment was not renewed by William II in 1689 (perhaps because of Sibbald’s short-lived conversion to Catholicism).

Sibbald and Adair confined their work largely to Scotland. The connections between the Geographer Royal or equivalent title, royal patronage, and public recognition of geography’s commercial and civic productions, principally maps, is first clear for Britain as a whole in the work of Thomas Jefferys, who was appointed Geographer to Frederik, Prince of Wales, in May 1746 and whose maps, signed thus, appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine from 1748. Jefferys was later Geographer to Prince George from 1757 and became Geographer to the King upon the latter’s accession. These connections were built upon by William Faden, who was appointed Geographer to George III in June 1783 and re-appointed in January 1821 having been Geographer to the Prince Regent from 1818 to 1820 (Worms, Citation2004).

The principal geographical output of the commercial Geographers Royal or equivalent was maps and atlases. That of the later individual holders has been scholarly monographs and research articles. The most evident public promotion of geography by a Geographer Royal was the ‘Colossal Globe’ or ‘Wyld’s Monster Globe’ as James Wyld Junior styled his walk-in globe, which was situated in London’s Leicester Square between 1851 and 1862. The globe was over 60’ in diameter. On entering, the public viewed the surface of the earth on the globe’s concave interior, with rivers and mountains modelled in plaster of Paris. As Geographer to Her Majesty, Wyld Junior is the only holder of the honorific to inherit it from his father. There is no record as to how this happened. Following the death in 1871 of Alexander Keith Johnston as Geographer Royal for Scotland, some in Scotland thought to advance his son, the geographer Keith Johnston, to the position. Officials within the Lord Chamberlain’s Office in St James’s Palace rejected the idea, noting (without reference to the Wylds) that it was ‘not usual to appt a son to succeed a father.’ As other candidates for the office had applied to the Lord Chamberlain (we are not told who), Keith Johnston was advised to submit his name in the usual way (Royal Archives, PP/VIC/1871/9707). It is not known whether he did, or how Thomas Brumby Johnston, or his son George Harvey Johnston, came to take up the title.

Several of those honoured worked with their predecessor or successor, even developing maps or texts together: Adair and Sibbald worked together before falling out, the Wylds and the Johnstons did so. Alexander Keith Johnston and the German map maker, Augustus Heinrich Petermann, worked together but their relationship turned sour. Petermann trained with Johnston in Edinburgh in the early 1840s before moving to London and Johnston had good reason to suspect the German of passing off Johnston’s work and that of his fellow trainees as his own. Petermann held his specific title at the same time as Johnson held his, the only foreign national to be so honoured. Petermann’s mapping was of a high standard but while in London he on several occasions promoted German geographical interests over those of the British and so incurred the disfavour of the geographical community there, several of whom bridled at Petermann’s honorific (Withers, Citation2019).

There are instances of persons using their royal honorific to advance their commercial interests as geographers – A. K. Johnston felt that Petermann did so in his use of the title ‘Physical Geographer to the Queen’ (and see the footnote to ) – but only one of an unsuccessful case being made for the position of Geographer Royal. The leading Edinburgh-based cartographer John George Bartholomew only ever held the title ‘Cartographer to the King’, despite a memorial signed by Fellows of the Royal Society, the Royal Geographical Society, the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and the Royal Scottish Geographical Society (undated, but c.1906-7) that he be appointed Geographer Royal for Scotland. The memorialists argued that the title ‘Geographer Royal for Scotland’ would, ‘on public and professional grounds, be an appropriate recognition of his eminence as a Geographer, and an encouragement in the prosecution of the highly important works on which he is at present engaged’ (RGS (with IBG) Archives, Corr., Citation1881-Citation1910: Bartholomew, p. 3). Whether this memorial was ever forwarded to the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, and, if it was, by whom Bartholomew was thought unworthy and on what grounds, is not known. The memorialists’ recognition of ‘public and professional grounds’ usefully summarises the bases on which appointments were made, with different emphases at one time or another.

Conclusion

The importance of royal patronage to geography is evident at an institutional level in Britain in the titles given the Royal Geographical Society, founded in 1830, and the Royal Scottish Geographical Society (Royal from 1887). This paper has for the first time documented those individual geographers who have received royal patronage from 1682 and noted the public and professional grounds on which they were recognised. The Geographer Royal for Scotland is the second oldest such subject-based honorific. The oldest is that of Her Majesty’s Historiographer Royal (present holder Christopher Smout, University of St Andrews), which was created in 1681. The position of Her Majesty’s Botanist for Scotland (also known as the Queen’s Botanist) was created in 1699 (present holder, Stephen Blackmore). That of Astronomer Royal for Scotland has been in existence since 1834 (present holder, Professor Catherine Heymans, University of Edinburgh).

That the Geographer Royal for Scotland or equivalent title has existed since 1682 is an indication of geography’s civic status and of the royal and public recognition of individual geographers and their work. The individual professorial esteem of some has been paralleled by those who held the position because of their professional output as, broadly, map makers. Quite why the position lapsed between George Harvey’s Johnston’s tenure of the position, and how his tenure came to overlap for some years with that of Edward Stanford, is not known. The impetus behind the revival of the position came from the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, which was keen to see the post as a marker of geography’s civic status. The criteria for the post of Geographer Royal for Scotland when the post was re-instated in 2015 were five-fold: ‘Candidates should be: professional, practicing geographers of high standing within the profession; able to operate over the whole subject matter of geography; prepared to speak up for geography in public; supporters of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society and its role, and committed to undertaking the role effectively’. Discharging these responsibilities over my six-year term – always enjoyable and a profound honour personally and for a subject I hold dear – was much affected over the last two years by the Covid-19 pandemic: epidemics are no respecters of personal esteem or professional output. In drawing upon her distinguished scholarship and public recognition, Professor Jo Sharp will no doubt confront new challenges and identify new opportunities as the latest custodian of an honour held by only a few over the past 340 years.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Professor Chris Philo for the invitation to write this essay and to Chris and Professor Jo Sharp for comments upon an earlier draft, to the staff of the Royal Archives and Royal Collection Trust for permission to cite from material in their care, and to Francis Herbert for drawing to my attention the memorial in respect of John George Bartholomew.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Dunbar, G. (ed.). (2001). Geography: Discipline, profession and subject since 1870. Kluwer.

- Heffernan, M. (2014). Geography and the Paris academy of sciences: Politics and patronage in early 18th-century France. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(1), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12008

- Herbert, F. (1983). The royal geographical society's membership, the map trade, and geographical publishing in britain 1830 toca1930: An introductory essay with listing of some 250 fellows in related professions. Imago Mundi, 35(1), 67–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085698308592557

- Johnston, R. (2003). The institutionalisation of geography as an academic discipline. In R. Johnston, & M. Williams (Eds.), A century of British geography (pp. 45–90). Oxford University Press.

- Livingstone, D. (1992). The geographical tradition: Episodes in the history of a contested enterprise. Blackwell.

- Moore, J. (2000). John adair's contribution to the charting of the Scottish coasts: A re-assessment. Imago Mundi, 52(1), 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085690008592919

- Pedley, M. (2005). The commerce of cartography: Making and marketing maps in eighteenth-century France and England. University of Chicago Press.

- RGS (with IBG) Archives, Corr. 1881–1910: Bartholomew.

- Royal Archives. PP/VIC/1871/9707.

- Withers, C. (1996). Geography, science and national identity in early modern Britain: The case of Scotland and the work of Sir robert sibbald (1641–1722). Annals of Science, 53(1), 29–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/00033799600200111

- Withers, C. (2001). Geography, science, and national identity: Scotland since 1520. Cambridge University Press.

- Withers, C. (2010). Geography and science in britain, 1831–1939: A study of the British association for the advancement of science. Manchester University Press.

- Withers, C. (2019). On trial: Social relations of map production in mid-nineteenth-century britain. Imago Mundi, 72(2), 72–95.

- Worms, L. (2004). The maturing of British commercial cartography: William faden (1749–1836) and the map trade. The Cartographic Journal, 41(1), 5–11. doi:10.1179/000870404225019972