ABSTRACT

Conferences of the UN climate change convention have legacies both in formal outcomes and treaties and in raising the profile of emerging climate dilemmas. The joint legacies of COP26 in Glasgow and COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh have been in elevating the profile and formalising the potential for solidaristic action on ‘Loss and Damage’ from climate change. This article reviews the documented outcomes on Loss and Damage from the two events to analyse the significance and constraints of this element of the overall climate change regime. Loss and Damage is likely to be constrained as a global collective action by the capacity to identify and measure losses and damages and by the ability of the climate change regime to deliver on meaningful resource transfers. Yet the formalisation of elements of climate justice through Loss and Damage is a real and lasting legacy of these COP events.

The circus in town

When the circus leaves town it leaves everyone breathless and slightly bereft. The feelings, reflections and longing for action are reflected in fantastically observed ethnographic studies of two weeks in Glasgow in late-2021 in this journal issue (McGeachan, Citation2023; Moreau, Citation2023; Parr, Citation2022; Sutherland, Citation2023). But the circus moves on. Although the UNFCCC COP26 in Glasgow created mass media coverage and highlighted distinctive contributions to international climate policy by the UK and Scotland, it was, in effect, only one of a very long series of Conferences of the Parties. Some COPs are memorable in climate policy as landmark and lasting agreements: the Paris Agreement and Kyoto Protocol have retained their place in climate policy patois. Some more technical outputs have remained important – the Cancun Accords, the Marrakech Accords – while other cities have fallen into the mists of forgotten venues for the annual Conference. Whether the Glasgow Adaptation Imperative or the Glasgow Climate Pact remain in the climate diplomacy lexicon over the incoming decades remains to be seen. But one way to assess the role of COP26 and the UK presidency is to examine how initiatives at Glasgow influenced the subsequent COP27 and how they moved the dial in terms of diplomatic and public discourse.

So, what were the outcomes of COP27 that linked to any progress at COP26? The COP27 took place in Sharm el-Sheikh under the Egyptian presidency in November 2022 with overall some similar outcomes to the COP26. In one dimension, both COP26 and COP27 are staging posts on the way to the reassessment of the Paris Agreement from 2015, formalised under the so-called Global Stocktake in 2023. The UK Presidency of COP26 made much of progress on nature, forests and contested wording on the phasing down of coal and fossil fuels. But no significant breakthrough on volunteered emission reduction was ultimately agreed at Glasgow, and the combined reduction in emissions could still be heading the world for well beyond 2.5°C of mean warming, even if implemented in full. Similarly, there were no significant new pledges on mitigation and emissions targets at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, with continued discussions on the need for urgency and the already unlikelihood or impossibility of achieving emissions reductions which would meet the 1.5°C global climate target (Pflieger, Citation2023). Indeed, Stavins (Citation2022) and other commentators have suggested that climate diplomacy between nation-states outside of the COP has been more significant – notably the China–US joint talks on climate co-operation during the G20 summit happening in parallel to COP27.

The most striking outcome of COP27 is undoubtedly the agreement on Loss and Damage and a process towards a Loss and Damage fund. ‘Loss and Damage’ refers to impacts from climate change that cannot be avoided through adaptation actions. Such impacts are prevalent in places with low adaptive capacity, and which have or are likely to experience significant negative consequences ranging across loss of infrastructure, displacement of people, and loss of habitability. But there is no consensus or definitive means of identifying what constitutes Loss and Damage, although it is clearly recognition of an imposed harm and crucial to realising climate justice (Boyd et al., Citation2021).

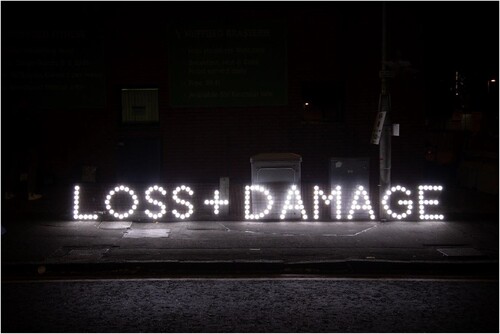

The genesis of this agreement on funding for Loss and Damage goes back well beyond the Warsaw International Mechanism from 2013 (see Johansson et al., Citation2022) and the Paris Agreement Article 7 from 2015 (see Boyd et al., Citation2021). But it was boosted at COP26 by solidarity between many climate-vulnerable countries, progressive industrialised countries, and civil society pressure during the COP26 events. The art installation shown in was one of a series created by Still/Moving across Glasgow during the COP26 weeks and is illustrative of the centrality of the issue of Loss and Damage to wider calls for climate justice. The Scottish First Minister pledged £1 million to the nascent Loss and Damage funding mechanism, alongside pledges from Wallonia, and increased this funding to £7 million in advance of COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh (Loss and Damage Collaborative, Citation2022). Such first moves by the Scottish government are clearly an attempt to create influence and distinctive contributions by the quasi-hosts (see Wilson et al., Citation2020). So, is Loss and Damage then the most likely significant outcome of COP26 and COP27 combined? The answer depends on whether Loss and Damage is an empty shell or the game-changer for climate justice.

Prospects for loss and damage

Is Loss and Damage mainly symbolic of climate justice? The COPs have been the site of disagreement about ultimate responsibility for climate change since they began, following the implicit inclusion of the ‘polluter pays principle’ in the original Framework Convention in 1992 through the notion of common but differentiated responsibility (Caney, Citation2010). The pollutert pays principle is central to many climate justice campaigns and calls for solidarity. It has led to development of diverse Funds within the climate change regime as means of redistributing resources from countries that have benefitted from fossil fuel development historically. Most of these Funds have been criticised for being too small to be effective, or indeed of stalling progress on the main objective of reducing emissions to avoid climate change in the first place (the precautionary principle).

There is therefore a risk that Loss and Damage, although central to contestations of climate justice advocates, becomes a further symbolic discussion about the urgency and peril of global society. The climate regime is littered with examples of framings of parts of the climate change dilemma that act as ‘boundary objects’ – rather than becoming substantial in themselves. These are often phrases in the Convention texts or in decisions and declarations from the subsequent Agreements and Protocols, but little more in practice.

As an example, there were prominent discussions in the mid-2000s that defining and measuring dangerous climate change would unlock global action, when the realisation of danger for all actors would supposedly spur urgent decarbonisation. The phrase ‘dangerous’ originates from the ultimate objective of the Framework Convention in Article 2: avoiding ‘dangerous anthropogenic interference in the climate system’, naming food insecurity, ecological consequences and economic disruption as such dangerous outcomes. The UK G8 Presidency of 2005 deployed diplomatic and scientific resources to make the phrase more meaningful to leaders of the world’s largest economies.Footnote1 The UK G8 Presidency convened a scientific conference hosted by the UK Met Office, where the UK Prime Minister challenged the community to identify a level of atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases that is ‘self-evidently too much’ (Blair, Citation2006). Yet ever more accurate scientific portrayals of the systematic consequences of climate change have not moved the dial of climate action with the G8 leaders, and the concept of dangerous climate change was overtaken by subsequently agreed global targets of 2.0°C and 1.5°C of warming as thresholds (Randalls, Citation2010).

Loss and Damage has already taken on some characteristics of just such a symbolic ‘boundary object’, rather than a specific mechanism within climate governance. The phrase has become a shorthand for all currently observed impacts of extreme weather where infrastructure is damaged or people are traumatised and displaced. Wildfires in California through to the major Pakistan floods of 2022 are evoked as examples of Loss and Damage in the present day.

At COP27, the final ‘cover decision’ includes reference to a process to set up a Loss and Damage Fund within the climate change regime. The home of this Fund is contested. It could be a Fund that relates to the Framework Convention or positioned under the Paris Agreement. The Paris Agreement included a statement that countries, in agreeing to Loss and Damage, are not admitting a basis for liability and compensation. If Loss and Damage is part of the Framework Convention, then countries identified in 1992 as being ‘developing’ bear less responsibility and are urged only to act voluntarily. Alternatively, if the Loss and Damage Fund is part of the Paris Agreement, then all countries, including growing polluters such as China, are more morally bound to contribute. Any process to set up such a Fund is likely to involve three to five years of discussions at COPs. And the history of funding suggests that the realisation of significant resource transfers will not be easy, and that there may be substitution between funds rather than additional funds. Developed countries have previously pledged $100 billion for mitigation and adaptation, but these pledges have not been upheld and the substantial majority have been allocated to decarbonisation rather than adapting to climate change impacts (OECD, Citation2022). So, in one sense, Loss and Damage is primarily the latest incarnation of attempts for financial flow to make the polluter pay – this time on the basis of liability and moral suasion, where previous voluntary funds were resourced on the basis of an ethics of solidarity.

Can Loss and Damage be made meaningful?

A second issue on the prospects for Loss and Damage is whether it can be bounded and governed. For a Fund to work, for example, there needs to be some scientific and agreed policy consensus on what constitutes losses from climate change and damages from climate change: metrics or measures of the standard losses and damages that can then in theory be compensated. Once in place, there is a requirement for a governance mechanism that addresses those losses that are not able to be compensated, through restorative justice, recognition justice or some other means.

Losses and damages are understood to be of different nature in physical and biological systems compared to social systems. Mechler and colleagues summarise a scientific convergence that Loss and Damage refers to the adverse climate-related impacts from both sudden-onset events (floods, wildfire, and cyclones) and slower-onset processes, including droughts, sea-level rise, glacial retreat, and desertification (Mechler et al., Citation2020). In essence, impacts of current and projected climate changes beyond 1.5°C have consequences for ecosystems such as coral reefs, wetlands, desiccated regions and low-lying land that cross thresholds.

There is therefore a significant challenge to generate meaningful metrics or measures of losses. In many countries, there are well-established mechanisms for compensating for loss of property and infrastructure where harm or fault or compulsory purchase is required (Larsen et al., Citation2008; Siders, Citation2019). But many elements of Loss and Damage are classified under the Warsaw Mechanism as non-economic loss and damage: life, mobility, health, territory, cultural heritage, indigenous knowledge, social identity, biodiversity and ecosystem services. This categorisation appears to be deliberately comprehensive and inclusive of all possible consequences of climate change that are not obviously financial and not commonly traded in markets. The categories encompass elements that relate to individuals, communities, or the environment more widely. The assumption is that these elements cannot be operationalised as monetary compensation is not adequate for their loss. Tshakert and colleagues (Citation2019) document that such losses are commonly reported everywhere and are place-specific experiences that are not easily commensurable.

While such elements of non-economic loss and damage such as loss of cultural heritage, elements of identity, and indigenous knowledge, have less standard observed consequences, even their loss can be evaluated in terms of their consequences on loss of well-being or even consequences for mental ill-health and perceived loss (Head, Citation2016). Marshall et al. (Citation2019), for example, showed how loss of pride and place attachment among residents of the Great Barrier Reef region in Australia, prompted both identifiable loss of perceived well-being after major coral bleaching events and fuelled the discourse of permanent potential loss of reefs that are important for human senses of place. Wewrinke-Singh (Citation2022) reports on research that the right to healthy environments has in itself led to policy change and amended priorities in those countries which had adopted such rights in national legislation. The adoption of a ‘healthy environment right’ under the UN General Assembly in 2022 is reflected in the COP27 text.

The category of mobility as an element of non-economic losses is an example of a category of loss that appears to be a catch-all for undesirable social change. Involuntary displacement from place of residence is a common outcome of weather extremes – predominantly temporary, but always traumatic (Adger & Safra De Campos, Citation2020; McLeman, Citation2014). Displacement has been shown to lead to many negative well-being and health consequences, including loss of sense of place and identity, and lowered economic and life opportunities. The category of mobility seeks to incorporate such loss but is open to interpretation in other ways. In addition, many adaptation interventions are designed to minimise the risk of temporary or permanent displacement with those losses in mind. At the same time, however, not all movement of populations can be regarded as loss, given that migration is an effective and common individual adaptation response to the changing opportunity landscape brought about by climate change (Black et al., Citation2011). Hence, there are no easily identifiable metrics and indicators for mobility as a category of loss, both because it has multiple outcomes and because the category includes elements that are not specifically losses.

In summary, the operationalisation of Loss and Damages relies on being able both to agree on metrics and measures of the diverse elements of loss as well as damage. But measures of loss are not a pre-requisite for fair and sustainable compensation as long as compensation is treated as beyond financial transfers, but includes words and actions derived from recognitional and restorative justice.

Conclusions

The legacies of Conference of the Parties mean much to host cities and governments. But they are only ever part of a long and tortuous narrative: the attempt to solve the global dilemma of climate change through global collective action by nation-states. Clearly global formalised action through treaty-making, diplomacy, and awareness-raising has elevated the global consciousness of the climate crisis since the Convention was signed in 1992. But it will only ever be part of the story. The Loss and Damage issue is a further manifestation of the requirement for solidarity and recognition of the multi-dimensional injustices of climate change. The legacy of COP26 and COP27 may not be visible in the continued moniker of ‘Glasgow’ or ‘Sharm’ in the lexicon of climate diplomacy, but the timely interventions to promote Loss and Damage as a means to a collective solidaristic response to the climate challenge will still be there.

For Glasgow and Sharm el-Sheikh, then, Loss and Damage is a significant and real legacy. Loss and Damage brings the issues of climate justice into sharp relief: climate change is not simply about technologies, carbon markets, and alternative imagined futures, but about the lived experience of climate change consequences for life and livelihoods. Those lived experiences are in every corner of the world, but are particularly acute in marginalised places and communities without significant adaptive capacity. Discussions around Loss and Damage at COPs and beyond reinforce climate change as a ‘violence’ and ‘imposed harm’. The mechanism of a Loss and Damage Fund may not be perfect, and indeed seems already to be on a trajectory for long and painful negotiation (Lo, Citation2023). Yet the discourse on Loss and Damage seeks to ensure that climate change cannot be resolved by leaving behind communities, places and people that are otherwise hidden in global-scale collective action.

Acknowledgements

Comments from the Editor are gratefully acknowledged. This research was funded in part by the Wellcome Trust (Grant 216014/Z/19/Z) and by International Development Research Centre, Justice in a Changing Climate programme (Grant 109741-002). For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Group of 8 (G8) and G20 are part of the international set of institutions seeking coordination between the world’s largest economies on issues of collective geopolitical concern.

References

- Adger, W. N., & Safra De Campos, R. (2020). Climate change disruptions to migration systems. In T. Bastia & R. Skeldon (Eds.), Routledge handbook of migration and development (pp. 382–395). Routledge.

- Black, R., Bennett, S. R., Thomas, S. M., & Beddington, J. R. (2011). Migration as adaptation. Nature, 478(7370), 447–449. https://doi.org/10.1038/478477a

- Blair, T. (2006). Foreword. In H.J. Schellnhuber, W. Cramer, N. Nakicenovic, T. Wigley, & G. Yohe (Eds.), Avoiding dangerous climate change. Cambridge University Press.

- Boyd, E., Chaffin, B. C., Dorkenoo, K., Jackson, G., Harrington, L., N'guetta, A., Johansson, E. L., Nordlander, L., De Rosa, S. P., Raju, E., & Scown, M. (2021). Loss and damage from climate change: A new climate justice agenda. One Earth, 4(10), 1365–1370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.09.015

- Caney, S. (2010). Climate change and the duties of the advantaged. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 13(1), 203–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230903326331

- Head, L. (2016). Hope and grief in the Anthropocene: Re-conceptualising human–nature relations. Routledge.

- Johansson, A., Calliari, E., Walker-Crawford, N., Hartz, F., McQuistan, C., & Vanhala, L. (2022). Evaluating progress on loss and damage: an assessment of the Executive Committee of the Warsaw International Mechanism under the UNFCCC. Climate Policy, 22(9-10), 1199–1212. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2112935

- Larsen, P. H., Goldsmith, S., Smith, O., Wilson, M. L., Strzepek, K., Chinowsky, P., & Saylor, B. (2008). Estimating future costs for Alaska public infrastructure at risk from climate change. Global Environmental Change, 18(3), 442–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.03.005

- Lo, J. (2023). Missed deadline raises risk of delays to loss and damage fund. Climate Home News. https://www.climatechangenews.com/2023/02/10/missed-deadline-raises-risk-of-delays-to-loss-and-damage-fund/

- Loss and Damage Collaborative. (2022). How Scotland spent its loss and damage pledge. Loss and Damage Collaborative. https://www.lossanddamagecollaboration.org/stories-op/how-scotland-spent-its-loss-and-damage-pledge

- Marshall, N., Adger, W. N., Benham, C., Brown, K., Curnock, M., Gurney, G. G., Marshall, P., Pert, P., & Thiault, L. (2019). Reef Grief: investigating the relationship between place meanings and place change on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Sustainability Science, 14(3), 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00666-z

- McGeachan, C. (2023). Growing love for the world: COP26 and finding your superpower. Scottish Geographical Journal, this issue.

- McLeman, R. A. (2014). Climate and human migration: Past experiences, future challenges. Cambridge University Press.

- Mechler, R., Singh, C., Ebi, K., Djalante, R., Thomas, A., James, R., Tschakert, P., Wewerinke-Singh, M., Schinko, T., Ley, D., & Nalau, J. (2020). Loss and Damage and limits to adaptation: recent IPCC insights and implications for climate science and policy. Sustainability Science, 15(4), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00807-9

- Moreau, M. (2023). COP26 protests in Glasgow: Encountering crowds and the city. Scottish Geographical Journal, this issue.

- OECD. (2022). Climate finance provided and mobilised by developed countries in 2016-2020: Insights from disaggregated analysis, climate finance and the USD 100 billion goal. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/286dae5d-en

- Parr, H. (2022). Encountering COP26 as a security event: a short walking ethnography. Scottish Geographical Journal, this issue.

- Pflieger, G. (2023). COP27: One step on loss and damage for the most vulnerable countries, no step for the fight against climate change. PLOS Climate, 2(1), e0000136. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000136

- Randalls, S. (2010). History of the 2 C climate target. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 1(4), 598–605. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.62

- Siders, A. R. (2019). Social justice implications of US managed retreat buyout programs. Climatic Change, 152(2), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2272-5

- Stavins, R. (2022). What really happened at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh? Harvard Kennedy School. Blog post. https://www.robertstavinsblog.org/2022/11/22/what-really-happened-at-cop27-in-sharm-el-sheikh/

- Sutherland, C. (2023). COP26 and opening to postcapitalist climate politics, religion, and desire. Scottish Geographical Journal, this issue.

- Tschakert, P., Ellis, N. R., Anderson, C., Kelly, A., & Obeng, J. (2019). One thousand ways to experience loss: A systematic analysis of climate-related intangible harm from around the world. Global Environmental Change, 55, 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.11.006

- Wewerinke-Singh, M. (2022). Enabling the right to a healthy environment. Nature Climate Change, 12(10), 885–886. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01487-2

- Wilson, B., Freeman, S., Funnemark, A., & Mason, E. (2020). Climate justice at COP26: how Scotland can champion change. Scottish Geographical Journal, 136(1-4), 57–61. doi:10.1080/14702541.2020.1863609