ABSTRACT

Whilst research attention on the mental wellbeing of farmers is growing, there are few studies focused on young farmers. Our research set out to better understand the factors affecting young farmer mental wellbeing and help-seeking behaviour. We draw insights from a combined study in Ireland and the UK, supplemented by separate studies by the same author team in both places. Through the use of young farmer interviews and surveys, as well as interviews of those who support young farmers with their mental wellbeing, we identify a mixed picture of mental wellbeing and a plethora of factors affecting it. Though many of these factors have been identified in the wider literature, the impact of socialisation and time off the farm, and sexism/misogyny affecting young female farmers, were specifically identified in our study. In some cases, young farmers were considered to be better at speaking about mental wellbeing than their older counterparts, but our study indicated that some people in this demographic fail to seek assistance because of stigma, stoicism, and possible lack of confidentiality. Improving the accessibility of mental wellbeing services, as well as normalising conversations on the subject and providing support in informal social settings, were identified as key recommendations.

1. Introduction

This paper explores the factors affecting the mental wellbeing and help-seeking behaviour of young farmers. There has been a proliferation of social research to understand the prevalence and drivers of poor mental wellbeing in farming communities across all demographics, as well as the availability and accessibility of support services. A recent study by the Royal Agricultural Benevolent Institution (RABI) in England and Wales discovered that around a third of farmers were probably or possibly depressed (RABI, Citation2021; Wheeler & Lobley, Citation2022), whilst state-level analyses in the United States suggest that farmers and ranchers die by suicide at higher rates than people in other occupations (Miller & Rudolphi, Citation2022). In Ireland, farmer mental health and suicide is a major concern for those actively involved in farming with 23.4% of farmers being considered at risk of suicide (Stapleton et al., Citation2022). Drivers of poor wellbeing, such as unpredictable/bad weather, public criticism, loneliness, financial pressures, stressed personal relationships, and animal and crop diseases, are widely documented (Deegan & Dunne, Citation2022; McAloon et al., Citation2017; Meredith et al., Citation2020; Wheeler et al., Citation2023; Yazd et al., Citation2019; Younker & Radunovich, Citation2022). As the emphasis on more sustainable farming practices has increased, agricultural policy transitions are being made across the world, including the decline of the livestock industry in some parts of the world and a push towards digitalisation. These transitions create uncertainty and are also affecting farmer mental wellbeing (Carolan, Citation2023; Stapleton et al., Citation2022).

Whilst we may still lack detailed information on whether and how the prevalence and driving factors of poor mental wellbeing vary between different types of farmers, workers, and family members (Chiswell, Citation2022), recent studies have indicated that demographics does have an influence (see section 2). However, there is still relatively little academic research which specifically examines the drivers of poor mental wellbeing and the help-seeking behaviours of young farmers, including in the UK and Ireland. Our study combines insights from studies in Ireland and the UK with the specific aims of understanding the drivers of poor mental wellbeing in a young farmer demographic, as well as help-seeking behaviour. We seek to build the empirical knowledge base to make recommendations for how to understand wellbeing in this demographic and how to ensure that support interventions are best targeted towards them.

2. Literature review

Isolation, lack of anonymity in close-knit communities, and poor accessibility of support services have long been known to challenge mental wellbeing in rural communities (Philo & Parr, Citation2004; Philo et al., Citation2017). As a key part of rural communities and as essential workers providing food for society, farmers, farm workers, and their families are also known to suffer from poor mental wellbeing. Farming is one of the most dangerous occupations regarding the level of injuries and fatalities. Farm work or agricultural work can involve long working hours, labour and high levels of stress due to unpredictability of weather and farming demands (Glasscock et al., Citation2006; Mulkerrins et al., Citation2022). Looking across the public as a whole, the medical literature illustrates a clear link between mental and physical well-being (Burgard & Lin, Citation2013; Chesley, Citation2014; Frone, Citation2008). Ohrnberger et al. (Citation2017) argue that there is a ‘strong’ link between mental and physical health, although the causality is under-studied, while Punton et al. (Citation2022) find that long waiting times for young adult mental healthcare in the UK made underlying physical conditions worse amongst their study participants. In the agricultural sector, poor mental wellbeing co-existed alongside poor physical health in the RABI survey (Citation2021) whilst stress and anxiety play a role in worsening health and safety.

In the ‘Big Farming Survey’ of England and Wales by RABI, reports of poor mental wellbeing were more common in some farming sectors than others (e.g. dairy) whilst women were more likely to report problems with anxiety/depression (Wheeler & Lobley, Citation2022), a pattern also seen in a further UK study by Rose et al. (Citation2022). The nature of farm and family tasks vary by gender; for example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the disproportionate burden of childcare and home schooling falling on farming women caused enhanced stress (Budge & Shortall, Citation2023). In the RABI study, working-age women were more likely to report suffering from anxiety and loneliness due to gender-based pressures, such as childcare and caring (Wheeler & Lobley, Citation2023). Men particularly (although not exclusively) may be more likely to suffer from the stigma of admitting problems which prevents help-seeking (Hammersley et al., Citation2023).

Age also appears to play a role. Though there are relatively few studies that focus on young farmer wellbeing specifically, a number of studies have been able to draw out statistics for this demographic. The RABI survey found that younger age groups were more likely to highlight challenges with their mental wellbeing, with 40% of 18–24-year-olds reporting problems with anxiety/depression compared to just 12% of their non-farming peers in the UK (RABI, Citation2021; Wheeler & Lobley, Citation2022).

Loneliness, isolation, and forced pandemic lockdowns are also strong drivers of poor mental well-being in young people and young farmers specifically. Young people were more likely to feel lonely during the COVID-19 pandemic and suffer from poor mental well-being (Bu et al., Citation2020; Gagné & McMunn, Citation2023; Groarke et al., Citation2020; Loades et al., Citation2020; Pierce et al., Citation2020). In a previous study, Rose et al. (Citation2022) found that a higher number of young farmers in the UK reported a negative impact of isolation caused by COVID-19 lockdowns: 86% of 18–24-year-olds and 74% of 25–34-year-olds said that lockdowns had impacted on their mental health compared to 58% of the sample as a whole.

Though most studies focus on farming populations as a whole, some research on driving factors for poor farming mental wellbeing has specifically focused on young farmers. The Farm Safety Foundation raises awareness of mental health issues amongst farmers aged 18–40 in the UK. Such research has inspired new training specifically aimed at young farmers.Footnote1 In their 2022 survey (457 young farmer responses, Farm Safety Foundation), 94% of the UK’s young farmers said that poor mental health is one of the biggest hidden problems, and respondents talked about the difficulty of opening up and seeking help on this issue.Footnote2 Through the use of mixed methods, our study enabled us to probe further qualitatively on the reasons behind these statistics. In a US study, 170 young farmers responded to a survey of which 35.9% mentioned mild symptoms of anxiety and 34.7% reporting more moderate or severe symptoms (Rudolphi et al., Citation2020). Driving factors for this anxiety were found to be personal finances, time pressures, economic conditions, and stressed intrapersonal relationships. A further study in the US found that those young farmers and ranchers who died by suicide were more likely to have relationship problems (Miller & Rudolphi, Citation2022).

The literature on help-seeking behaviours and the landscapes of support for farmer wellbeing is growing (Shortland et al., Citation2023). Various barriers to farmers seeking help have been identified including, but not limited to; the stigma of asking for help (Roy et al., Citation2017), especially in close-knit communities (Philo et al., Citation2017; Philo & Parr, Citation2004) which may support certain macho stereotypes (Hammersley et al., Citation2023; Herron et al., Citation2020); poor accessibility or availability of formal support services in rural communities, made worse by a digital divide (Hagen et al., Citation2021; Philip et al., Citation2017); financial barriers to access support which is not free (Hagen et al., Citation2021); long hours and workload reducing the ability to enjoy time off the farm (Wheeler & Lobley, Citation2023); and lack of understanding about farming from health professionals (Shortland et al., Citation2023).

A study in Australia by Vayro et al. (Citation2022) indicated that young farmers may be more willing to talk about mental health issues than older farmers, but this is not currently supported widely elsewhere. In the RABI study, younger farmers were less likely to confide in anyone about poor mental wellbeing and more likely to report feeling lonely (RABI, Citation2021). This supports findings in the wider medical literature which has indicated that young people may be less likely to seek support for their mental health (Marcus et al., Citation2012; Rickwood et al., Citation2007). A literature review by Vanheusden et al. (Citation2008), which accompanied an empirical study, found multi-country evidence (e.g. New Zealand, Finland, The Netherlands) of young adults declining to access mental health services if they were struggling. The study suggested that this may partially be driven by personal experience and knowledge of services, but also as a result of mental health services not adequately engaging young people in accessible ways (see also Patel et al., Citation2007).

In farming, landscapes of support are diverse and varied (Shortland et al., Citation2023) but informal spaces of support provided by family, friends, and peers are critical (Furey et al., Citation2016: Knook et al., Citation2023; Nye et al., Citation2022). Some young farmer-specific studies have focused on help-seeking and support, but this is a relatively under-explored area. Syson-Nibbs et al. (Citation2009) describe a project amongst young hill farmers in England which utilised photographic methods encouraging the farmers to record their feelings and experiences of farming. These photos were shown in an exhibition and the process was found to improve the self-esteem and self-efficacy of the young farmers. Other studies suggest that different support methods may need to be utilised to reach young farmers, including talking at Young Farmers Clubs, using social media more, and making support seem less ‘clinical’ (Malaztky et al., Citation2022; Roy et al., Citation2017; Shortland et al., Citation2023). Informal spaces of support from family, friends, advisors, and in the community are also likely to remain important (Furey et al., Citation2016). Digital interventions, such as the use of social media or apps, are also useful for a young audience (Fergie et al., Citation2016; Newbold et al., Citation2020; Rickwood et al., Citation2007). A recent publication on the ‘digital self-care’ practised by young farmers in the UK illustrates the potential to support wellbeing in digital spaces (Holton et al., Citation2023). Holton et al. (Citation2023) interviewed 28 young farmers in the UK, exploring how they practise digital self-care through the curation of social media. From a geographical perspective, the online space (if accessible in rural communities with poor connectivity) offers the potential to overcome the physical problem of isolation and poor accessibility of mental health services. Indeed, Holton et al. (Citation2023, p. 2) report on research that shows that mobile phone apps and social media are ‘essential tools for generating belonging and embeddedness within rural communities’.

Nevertheless, there is still relatively little academic research which specifically examines the drivers of poor mental wellbeing and the help-seeking behaviours of young farmers, including in the UK and Ireland. Our study combines insights from studies in Ireland and the UK with the specific aims of understanding the drivers of poor mental wellbeing in a young farmer demographic, as well as help-seeking behaviour. We seek to build the empirical knowledge base to make recommendations for how to understand wellbeing in this demographic and how to ensure that support interventions are best targeted towards them and sufficiently resourced.

3. Methods

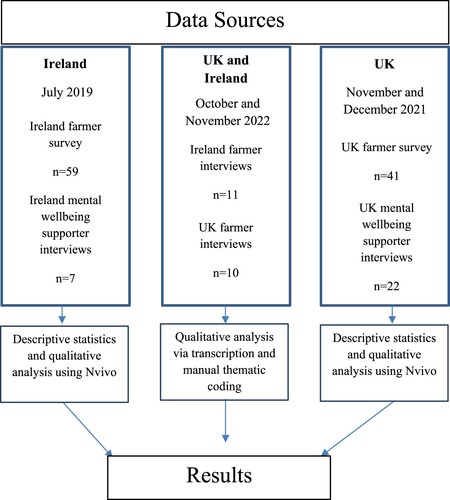

For this paper, we combine insights from two separate studies and one joint study by the listed authors (see ). Though the initial two studies were conducted separately during 2019 and 2021 respectively, there are valuable lessons learned in drawing themes together, which inspired the joint interview work conducted in late 2022/early 2023. When outlining the results, we report distinctly on the separate methods, before reflecting on key lessons. We targeted two specific groups in this research, young farmers themselves and those who supported farmer wellbeing in various roles. We discuss the methods used to gain insights from each group below. For all data collection, ethical approval was gained from the relevant institution (UCD, Reading, Cranfield). We have created some appendices containing further details of the two studies – questionnaire designs and sample information, etc. – that are included in a Supplemental Information document available with this paper on the Scottish Geographical Journal website. Those appendices are cross-referenced in the text below.

3.1. Young farmers

Definitions of what constitutes a ‘young farmer’ vary, but for the purposes of this research, interview and survey recruitment focused on farmers between the age of 18 and 40 (in line with an EU definitionFootnote3). We gained the views of 21 young farmers via common semi-structured interviews in Ireland and the UK, as well as two separate surveys in the same countries. The interviews focused on the two main objectives outlined above: drivers of poor mental wellbeing and help-seeking/support (see Appendix 1). In the UK, volunteers were recruited between October and November 2022 via social media posts (Twitter, LinkedIn, The Farming Forum) and by emailing student unions and representatives at the major UK agricultural colleges and universities (see Appendix 1). In Ireland, volunteers were recruited between October 2022 and January 2023 via the young farmer organisation (Macra na Feirme), agricultural colleges and universities, and agricultural extension services (see Appendix 1). Sampling attempted to ensure we had representatives across farming sectors and genders. The sample was skewed towards male farmers (Ireland [10 males, 1 female], UK [7 male, 3 female]) and towards the livestock sector in Ireland (see Appendix 1).Footnote4

We conducted ten interviews in the UK with farmers aged between 20 and 36, from England, Wales, Scotland, and NI and eleven interviews in Ireland, with farmers aged between 21 and 32 (see Appendix 1). The UK interviews lasted between 13 and 31 min and the Irish interviews lasted between 20 and 60 min. Interviews were conducted over the phone or online, recorded, transcribed, and manually thematically coded to pick out drivers of poor mental wellbeing and views related to help-seeking and support services (one person analysed all interviews). In the UK, interviews were carried out by one female researcher and in Ireland interviews were carried out by two male and one female researchers.

The UK survey focused on factors affecting both farmer wellbeing and help-seeking (see Appendix 2), but did not specifically target young farmers. It used an online survey distributed via social media and farmer contacts in the UK between November and December 2021. In total, 207 responses were gathered with 41 responses from farmers under 35 being analysed in this paper (the next category was 35–44 so was excluded from analysis).

The Irish survey specifically targeted young farmers in July 2019. Containing open-ended and closed-ended questions, the survey was composed of several sections, including background and farmer wellbeing, understanding of services and mental wellbeing, availability of support services, and accessibility to support services and a mental wellbeing scale (see Appendix 3). The questionnaire was completed by 59 farmers aged 17–40 across the North-West of Ireland (see Appendix 4).

We recognise the relatively small sample sizes in both surveys and therefore caveat quantitative statements made in the results. However, we also utilise qualitative information from these surveys alongside in-depth comments, italicised in what follows, arising in the interviews.

3.2. Supporters of farmers and farmer wellbeing

Supporters of farm mental health include formal individuals/organisations (healthcare, mental health charities) and informal individuals/organisations (farmer peer groups, advisors, auction mart staff, chaplains) which may not overtly focus on mental wellbeing (Shortland et al., Citation2023). Their perspective gained from working with young farmers is important to include in our assessment of driving factors and help-seeking behaviours. We included these perspectives in this paper via two separate semi-structured interview guides.

The supporter interviews in Ireland, conducted in July 2019 and lasting up to 20 min, addressed the topics of: (i) the level of mental wellbeing of young farmers in the northwest of Ireland; (ii) examination of the support services available to young farmers; and (iii) an assessment of the services that are offered (see Appendix 5). Seven key informants in the agricultural industry were interviewed who worked to provide advice to farmers, including on wellbeing. These key informants were identified through the leading organisations of Macra Na Feirme, Irish Farmers Association (IFA), Mental Health Ireland (MHI), and the Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine (DAFM). A pilot study for the questionnaires was carried out with agriculture students at University College, Dublin. Pilot interviews were also carried out with Macra Na Feirme. A full transcription of each recording was carried out immediately after each interview. The transcriptions were then imported into the statistical analysis software NVivo for thematic coding.

The UK interviews of supporters of farm mental health did not specifically ask questions about young farmers, but they were discussed in many of the interviews and this data has not been specifically reported on before (see Appendix 6 for questions). Organisations were selected through the Prince’s Countryside Fund National Directory of Farm and Rural Support Groups (Citation2021),Footnote5 as well as known contacts. Interviews were carried out in England, Wales, and Scotland due to the contacts we were able to generate at the time. We interviewed 22 supporters of farmer mental wellbeing, including ten mental health charities, three healthcare workers, three farmer peer groups, two chaplains, an agricultural organisation, a member of a local council, a local community group member, and one staff member at an auction mart. They were conducted online or on the phone during the months of May and June 2021, which varied in length from 30 to 70 min. They were audio-recorded and transcribed. The interviews were undertaken by three researchers on the project team; interviews were coded both manually and by using NVivo by two co-authors. Analysis for this paper specifically searched the transcript for comments related to young farmers in relation either to drivers or poor wellbeing or help-seeking behaviours.

4. Findings

4.1. Factors affecting young farmer mental wellbeing

Respondents to the young farmer survey in NW Ireland were asked to define mental wellbeing and their answers can be grouped into three main themes:

Being happy, content or relaxed (‘being happy in yourself and your surroundings’ [farmer], 29 comments).

Having a positive, enjoyable or healthy mindset (‘being able to get out of the bed in the morning to do what you enjoy doing’ [farmer], 15 comments).

Having the calmness and resilience to deal with stressful situations (‘being able to deal with the daily ups and downs life throws at us’ [farmer], 11 comments).

This survey also asked young farmers if they thought mental wellbeing was an issue amongst their peers in the region, to which 55/59 (93%) said ‘Yes’. When asked to describe their daily mental wellbeing, it was clear that not all young farmers in the sample were struggling, since 37/57 of young farmers answered ‘good’ or ‘great’ (65%) with 16/57 rating it as ‘average’ (28%) and just 4/57 (7%) as ‘poor’. The statistics are not necessarily contradictory – young farmers in our study and in the survey carried out by the Farm Safety FoundationFootnote6 (2022) could legitimately say that mental well-being is an important issue amongst their peers while not struggling themselves. Some of our interviewees expanded on reasons why they enjoyed farming, and also the quotes around socialisation in section 4 indicate that some enjoy access to supportive social networks. This finding illustrates the danger of making assumptions that mental wellbeing is bad for all farmers, including the younger demographic. In the interviews, several young farmers described how they ‘love farming’ (Male farmer, Ireland, interview 9) and that it has a positive impact on their mental wellbeing:

When you are up and say you're finished milking and you would be maybe going down on the quad on a nice day and the cows are out grazing, it’s a really nice place to be, you would feel very content. (Male farmer, Ireland, interview 3)

I suppose being out in fresh air and out and about is the best thing for mental health. (Male farmer, Ireland, interview 7)

I consider myself very lucky to live here and work here. (Female farmer, UK, interview 6)

I’ve had bad PTSD from the past and working with animals helps me. (Male farmer, UK, interview 3)

I am definitely not built for an office job. I like being outside, being around cows, having the peace and quiet. (Female farmer, UK, interview 1)

Many of the supporters of farming mental wellbeing in Ireland agreed that it was not a problem for everyone, indeed being ‘quite good’ (Irish supporter, interview 3) for some. However, one supporter said (interview 4) who worked extensively in the NW Ireland region said ‘you never know what’s going on behind closed doors’.

In both surveys, we asked about factors affecting young farmer mental wellbeing. In the UK survey, to which 20 and 18 farmers (out of 41) replied they had not reached out for support with their mental wellbeing either before or after the COVID-19 pandemic. For those who had sought support, prominently ranked drivers before the pandemic were (in order from highest to lowest):

Illness (including mental illness) – 7

Family or relationship issues – 7

Financial problems – 7

Rural crime – 6

Succession – 4

This differed slightly from the top five list of prominently ranked drivers for all 207 farmers across all ages (Rose et al., Citation2022). Across all farmers, ‘succession problems’ – meaning who was going to inherit or take over the farm – was not ranked in the top five, being replaced by ‘pressure of regulations and government inspections’.

For those who had sought support, prominently ranked drivers during the pandemic were (in order from highest to lowest):

Loneliness and social isolation – 9

Rural crime – 8

Illness (including mental illness) – 6

Family or relationship issues – 6

( = ) Succession, post-Brexit uncertainty, media farmer portrayal, financial problems – 4

The changes indicated that loneliness and social isolation created particular problems for young farmers during the pandemic and rural crime also became a bigger driver of poor mental wellbeing. This mid-pandemic ranking was slightly different than for all 207 farmer respondents across all ages (Rose et al., Citation2022). For all farmers, financial problems and loneliness were ranked equally first, followed by illness, family problems, and rural crime. Succession was only ranked eighth.

In the Irish survey of young farmers, the five most highly ranked factors affecting wellbeing were: workload and time available to socialise off the farm; financial concern; isolation and loneliness (including lack of sexual relationships); family challenges (relationships, childcare, illness); and weather. Several comments noted how individual stressors combined to create multiple challenges at the same time.

In our young farmer interviews in the UK and Ireland, a number of similar and additional factors were raised, as shown in . To this table, we also add insights gathered from UK and Irish interviews from those people who advise and support young farmers.

Table 1. Factors affecting mental health in young farmer interviews and surveys (UK and Ireland). Source: authors’ own research.

Broadly, these factors affecting mental health can be split into four categories, although they overlap:

Farming specific – animal/crop disease, work performance, regulations, workload, weather.

Social – illness, loneliness and isolation, relationships, time off the farm, sexism, succession.

Economic – finances and business performance.

Public engagement – media negativity and rural crime.

Although research seeking to understand drivers of poor mental wellbeing is gathering pace, Chiswell (Citation2022) argues that finer level detail is still lacking about the prevalence of problems across farming communities, particularly on why some farmers appear to be affected more than others. Recent studies have begun to explore the variations in levels of mental wellbeing between different types of farmers (e.g. by age, gender, enterprise), as well as how drivers themselves might vary (Miller & Rudolphi, Citation2022; Rudolphi & Barnes, Citation2020; Wheeler & Lobley, Citation2022). While all of the factors outlined in have been identified before as driving factors in previous literature (see reviews by et al., Citation2019; Younker & Radunovich, Citation2022), there is limited research specifically on why – and the extent to which – individual factors (which readily combine to create multiple stressors) affect young farmers specifically.

Our research highlights the particular importance of socialising (described as ‘critically’ important in our study) to young farmers and the value of spending time off the farm. We know that this demographic in the UK had reported a higher negative impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on their mental health (Rose et al., Citation2022). Socialising is made difficult by intense workloads, the struggle to make money, and the challenge of either feeling forced to take over the farm or struggling to become established in the industry for those without farming backgrounds. It is also challenged by geographical isolation, which further reduces time for building platonic and sexual relationships that are so important for young people. Our research further notes the impact of sexism and misogyny faced by some women in farming, although it should be noted that we only spoke to four female farmers. There were different manifestations of this problem noted by three female farmers; on the one hand, misogynistic comments about appearance and relationships, and on the other hand, sexism relating to the stereotype that women may not be seen as being as strong as men and therefore had to work harder to give the appearance of strength (even in the midst of having additional non-farming responsibilities).

4.2. Accessing support

Various sources of support were identified by the participants in our studies, including professional help (i.e. GPs, mental health nurses, counsellors and psychiatrists), mental health charities, family, friends, and farmer groups, particularly young farmers clubs. Our data collection instruments noted a number of different factors affecting the help-seeking behaviour of young farmers. provides an overview of the factors collected from our farmer/supporter interviews and surveys; again factors are interlinked (e.g. stigma being affected by stoicism). By far the most prominently discussed theme was the stigma around seeking support for mental wellbeing, particularly (but not exclusively) for young male farmers.

Table 2. Factors (and possible solutions) influencing the help-seeking behaviour of young farmers. Source: authors’ own research [all data sources].

The factors listed in have been identified before in previous literature on farmer help-seeking behaviour. Previous research has identified lack of awareness and accessibility of support as key factors (Hagen et al., Citation2021), the importance of support from family and friends (Furey et al., Citation2016: Knook et al., Citation2023; Nye et al., Citation2022), and the value of offering support that is less ‘clinical’ in nature, more informally framed, and digitally for younger generations (Cole & Bondy, Citation2020; Fergie et al., Citation2016; Holton et al., Citation2023; Malaztky et al., Citation2022; Roy et al., Citation2017). Research has also identified the role of stigma and stoicism in reducing help-seeking, especially within communities where there are high levels of social connectedness (Philo et al., Citation2017; Philo & Parr, Citation2004; Roy et al., Citation2017). Our research suggests that stigma might especially affect farming men, which has been noted previously (Hammersley et al., Citation2023; Herron et al., Citation2020), but the influence of the macho stereotype clearly affects both genders. As noted above when highlighting the issue of sexism, a female farmer in Ireland (interview 2) said in our study:

There is a stigma to it. I think when you look, especially if you bring this into young farmers … [there] will be a high percentage of males where mental health has always been an issue … [but] the male gender being able to talk or ask for help [is more difficult] … if you are female in agriculture, you have to make yourself as strong as the other people around you.

The younger generation are much better than the older generation. I think that’s a universal factor in about acknowledging mental health issues … they’re much better about talking about their mental health. (Chaplain, UK, interview 3)

I think the young are better at coming forward, so … it might be that it’s stigma or that it’s just more normal to be looking into those sorts of things. (NHS worker, UK, interview 8)

[T]here’s been a few polls conducted, like the Scottish Association of Young Farmers, and they found there was a high percentage of young farmers coming through who are more open and believe that talking about mental health is a way to reduce the stigma, so we’re maybe going to see a generational change over the next ten or so years about being a bit more open to talk about it. (Mental health charity, UK, interview 12)

Two young farmers in interview complicated this view, however, echoing the conclusions of the RABI study (Citation2021) which found that the youngest age groups were less likely to reach out for support:

[M]ental health in general, has always been quite taboo. A lot of people find it hard, and I don’t want to stereotype a demographic here, but men tend to be like ‘suck it up’. But in the last couple of years, like there is more of an acceptability to put your hand up and say I’m having a problem, but it wasn’t always like that, and it’s still not like that in a lot of places. (Male farmer, Ireland, interview 11)

It's seen as like a bit of a weakness, and I think it’s still seen as a weakness, even though we’re all aware of it now. A lot of people are aware of it. I think it’s still seen as if you admitted you’ve got a bit of a problem people … would look down on them. (Male farmer, UK, interview 7)

5. Discussion and conclusions

A specific focus on the mental wellbeing of young farmers has thus far been lacking from the literature. Our paper indicates that many of the driving factors for poor mental wellbeing identified in the wider literature hold relevance in the context of young farmers. Furthermore, our findings on the mixed picture of farmer mental wellbeing, with some individuals struggling more than others who enjoy farming, are mirrored elsewhere in surveys across farming demographics. However, our focus on young farmer mental wellbeing particularly highlights the prominence of the impact of socialisation and time off the farm (or lack thereof) on the mental wellbeing of this demographic. Although we spoke to relatively few young female farmers, our research also suggests that the impact of different forms of sexism and misogyny is likely to be impacting the mental wellbeing of others outside of this study. Our UK survey also indicated that succession concerns may affect mental wellbeing of young farmers more than other age groups. Our findings reinforce recent calls for further research into the impact of the combination of multiple stressors on farmer mental wellbeing and how these are distributed across different types of farmers (Chiswell, Citation2022; Rose et al., Citation2022; Wheeler & Lobley, Citation2023). We know that different types of farmers – young/old, male/female, arable/livestock, etc. – face varying pressures that affect mental wellbeing. However, we need further research into understanding how the stacking of different demographics and situations affects mental wellbeing and which combination might make someone particularly vulnerable; for example, how do the drivers of, and risk for, poor mental wellbeing differ between a young, female, livestock farmer as compared to an old, male, arable farmer?

On the subject of help-seeking behaviour and the accessibility of support for poor mental wellbeing, we too noted some similarity in factors as identified in the wider literature, with stigma featuring prominently as a major barrier to gaining support. Our findings allowed us to reflect on whether younger farmers may be more or less affected by stigma, with mixed conclusions drawn from previous literature (RABI, Citation2021; Vayro et al., Citation2022). Whilst conversations about mental wellbeing may be more prominent than before in young farmer clubs and other social settings, our research indicated that stigma is still a primary factor affecting the ability of some young farmers to seek support. Further research is required to understand whether and how help-seeking is changing amongst the young demographic. Our research also reinforced conclusions in previous literature that informal social settings may be the best place to provide support to young farmers (e.g. Young Farmers Clubs), but professional support is still required, especially for those who feel that they cannot open up to friends, peers, and family. Our results further indicated that digital tools to support mental wellbeing could also be useful for young farmers in particular, and learnings from the literature on digital self-care (Holton et al., Citation2023) will therefore be useful to take forward in terms of how young farmers are engaging with social media. Academic studies of interventions to improve mental wellbeing for young farmers could test the efficacy of various methods of engagement, centring on variables like format (e.g. digital, paper), location (in-person, digital, young farmers clubs, colleges/universities, workplace), and who delivers it (e.g. peers, medical professionals).

Our recommendations to improve the accessibility and acceptability of support for mental wellbeing are rooted in the suggestions made by young farmers themselves. It is not just a case of improving the availability of support services in remote rural locations, increasing the farming knowledge of professional supporters, and equipping all individuals who come into contact with farmers with the skills needed to spot signs of distress and signpost towards support. Whilst all of these actions are important, further normalising conversations around poor mental wellbeing in all of the spaces that young farmers occupy (schools, colleges, universities, workplaces, social settings) is vital. The root causes of poor farming mental health also need to be tackled. Normalisation may not always overtly take the form of support for mental wellbeing. Young farmers in our study argued for mental wellbeing support that masquerades as something less intrusive or scary; for example, social activities and discussion groups where farmers may be encouraged to open up or reflect on how they are feeling without the pressure of talking specifically about mental wellbeing. These actions also require assistance from a wide range of people who engage young farmers, therefore emphasising the need for farming support organisations (especially peer groups) to work in and beyond traditional farming settings and to embrace digital technologies as a means of complementing face-to-face support.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (50.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank all people who participated in our study or helped to distribute surveys. We thank Lorna Philip and the editorial team and the reviewers for their comments. We thank Dr Faye Shortland for all her work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Interview data is not available due to the sensitivity of the topics discussed and possibility to identify respondents. Survey data from Ireland is not available as there were no resources to anonymise and archive it. Anonymised survey data from the UK is available at https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/855791/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

4 Ireland is predominantly a grass-based farming industry (84% of agricultural area is grass, 9% common and rough grazing) and so our interviewees covered various enterprises within the livestock sector. In Ireland 13% of farm holders are women. Around 55% of the farm workforce in the UK are women, although only 16% are registered farm holders (https://www.nfuonline.com/updates-and-information/let-s-value-every-player-on-the-bench/).

References

- Bu, F., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Social Science & Medicine, 265, Article 113521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113521

- Budge, H., & Shortall, S. (2023). Agriculture, COVID-19 and mental health: Does gender matter? Sociologia Ruralis. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12408

- Burgard, S. A., & Lin, K. Y. (2013). Bad jobs, bad health? How work and working conditions contribute to health disparities. American Behavioural Scientist, 57(8). https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213487347

- Carolan, M. (2023). Digital agriculture killjoy: Happy objects and cruel quests for the good life. Sociologia Ruralis. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12398

- Chesley, N. (2014). Information and communication technology use, work intensification and employee strain and distress. Work, Employment and Society, 28(4), 589–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017013500112

- Chiswell, H. (2022). Psychological morbidity in the farming community: A literature review. Journal of Agromedicine. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2022.2089419

- Cole, D. C., & Bondy, M. C. (2020). ‘Meeting farmers where they are–rural clinicians’ views on farmers’ mental health’. Journal of Agromedicine, 25(1), 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2019.1659201

- Deegan, A., & Dunne, S. (2022). An investigation into the relationship between social support, stress, and psychological well-being in farmers. Journal of Community Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22814

- Fergie, G., Hilton, S., & Hunt, K. (2016). Young adults’ experiences of seeking online information about diabetes and mental health in the age of social media. Health Expectations, 19(6), 1324–1335. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12430

- Frone, M. R. (2008). Are stressors related to employee substance use? The importance of temporal context in assessments of alcohol and illicit drug use. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.199

- Furey, E. M., O’Hora, D., McNamara, J., Kinsella, S., & Noone, C. (2016). The roles of financial threat, social support, work stress, and mental distress in dairy farmers’ expectations of injury. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 126. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00126

- Gagné, T., & McMunn, A. (2023). Mental health inequalities during the second COVID-19 wave among millennials who grew up in England: Evidence from the next steps cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 327, 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.101

- Glasscock, D. J., Rasmussen, K., Carstensen, O., & Hansen, O. N. (2006). Psychosocial factors and safety behaviour as predictors of accidental work injuries in farming. Work & Stress, 20(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370600879724

- Groarke, J. M., Berry, E., Graham-Wisener, L., McKenna-Plumley, P. E., McGlinchey, E., & Armour, C. (2020). Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 psychological wellbeing study. PLoS ONE, 15(9), e0239698.

- Hagen, B. N. M., Sawatzky, A., Harper, S. L., O’Sullivan, T. L., & Jones-Bitton, A. (2021). ‘Farmers aren’t into the emotions and things, right?’: A qualitative exploration of motivations and barriers for mental health help-seeking among Canadian farmers. Journal of Agromedicine, 27(2), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2021.1893884

- Hammersley, C., Meredith, D., Richardson, N., Carroll, P., & McNamara, J. (2023). Mental health, societal expectations and changes to the governance of farming: Reshaping what it means to be a ‘man’ and ‘good farmer’ in rural Ireland. Sociologia Ruralis. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12411

- Herron, R. V., Ahmadu, M., Allan, J. A., Waddell, C. M., & Roger, K. (2020). ‘Talk about it’: Changing masculinities and mental health in rural places? Social Science and Medicine, 258, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113099

- Holton, M., Riley, M., & Kallis, G. (2023). Keeping on[line] farming: Examining young farmers’ digital curation of identities, (dis)connection and strategies for self-care through social media. Geoforum, 142, Article 103749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2023.103749

- Knook, J., Eastwood, C., Michelmore, K., & Barker, A. (2023). Wellbeing, environmental sustainability and profitability: Including plurality of logics in participatory extension programmes for enhanced farmer resilience. Sociologia Ruralis. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12413

- Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

- Malaztky, C., Bourke, L., & Farmer, J. (2022). ‘I think we’re getting a bit clinical here’: A qualitative study of professionals’ experiences of providing mental healthcare to young people within an Australian rural service. Health and Social Care in the Community, 30(2), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13152

- Marcus, M. A., Westra, H. A., Eastwood, J. D., & Barnes, K. L. (2012). What are young adults saying about mental health? An analysis of internet blogs. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(1), e17. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1868

- McAloon, C. G., Macken-Walsh, Á, Moran, L., Whyte, P., More, S. J., O’Grady, L., & Doherty, M. L. (2017). Johne’s disease in the eyes of Irish cattle farmers: A qualitative narrative research approach to understanding implications for disease management. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 141, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2017.04.001

- Meredith, D., McNamara, J., Van Doorn, D., & Richardson, N. (2020). Essential and vulnerable: Implications of COVID-19 for farmers in Ireland. Journal of Agromedicine, 25(4), 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2020.1814920

- Miller, C. D. M., & Rudolphi, J. M. (2022). Characteristics of suicide among farmers and ranchers: Using the CDC NVDRS 2003–2018. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 65(8), 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23399

- Mulkerrins, M., Beecher, M., McAloon, C. G., & Macken-Walsh, Á. (2022). Implementation of compact calving at the farm level: A qualitative analysis of farmers operating pasture-based dairy systems in Ireland. Journal of Dairy Science, 105(7), 5822–5835. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-21320

- Newbold, A., Warren, F. C., Taylor, R. S., Hulme, C., Burnett, S., Aas, B., Botella, C., Burkhardt, F., Ehring, T., Fontaine, J. R. J., Frost, M., Garcia-Palacios, A., Greimel, E., Hoessle, C., Hovasapian, A., Huyghe, V. E. I., Lochner, J., Molinari, G., Pekrun, R., … Watkins, E. R. (2020). Promotion of mental health in young adults via mobile phone app: Study protocol of the ECoWEB (emotional competence for well-being in young adults) cohort multiple randomised trials. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 458. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02857-w

- Nye, C., Winter, M., & Lobley, M. (2022). The role of the livestock auction mart in promotion help-seeking behavior change among farmers in the UK. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1581. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13958-4

- Ohrnberger, J., Fichera, E., & Sutton, M. (2017). The relationship between physical and mental health: A mediation analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 195, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.008

- Patel, V., Flisher, A. J., Hetrick, S., & McGorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet, 369(9569), 1302–1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7

- Philip, L., Cottril, C., Farrington, J., Williams, F., & Ashmore, F. (2017). The digital divide: Patterns, policy and scenarios for connecting the ‘final few’ in rural communities across Great Britain. Journal of Rural Studies, 54, 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.12.002

- Philo, C., & Parr, H. (2004). ‘They shut them out the road’: Migration, mental health and the Scottish highlands. Scottish Geographical Journal, 120(1–2), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00369220418737192

- Philo, C., Parr, H., & Burns, N. (2017). The rural panopticon. Journal of Rural Studies, 51, 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.08.007

- Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., Kontopantelis, E., Webb, R., Wessely, S., McManus, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

- Punton, G., Dodd, A. L., & McNeill, A. (2022). ‘You’re on the waiting list’: An interpretive phenomenological analysis of young adults’ experiences of waiting lists within mental health services in the UK. PLoS ONE, 17(3), e0265542. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265542

- RABI. (2021). The big farming survey the health and wellbeing of the farming community in England and Wales in the 2020s. Retrieved April 2022, from https://rabi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/RABI-Big-Farming-Survey-FINAL-single-pages-No-embargo-APP-min.pdf

- Rickwood, D. J., Deane, F. P., & Wilson, C. J. (2007). When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? The Medical Journal of Australia, 187(S7), S35–S39. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01334.x

- Rose, D. C., Shortland, F., Hall, J., Hurley, P., Little, R., Nye, C., & Lobley, M. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on farmers’ mental health: A case study of the UK. Journal of Agromedicine. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2022.2137616

- Roy, P., Tremblay, G., Robertson, S., & Houle, J. (2017). ‘Do it all by myself’: A salutogenic approach of masculine health practice among farming men coping with stress. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(5), 1536–1546. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988315619677

- Rudolphi, J. M., & Barnes, K. L. (2020). Farmers’ mental health: Perceptions from a farm show. Journal of Agromedicine, 25(1), 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2019.1674230

- Rudolphi, J. M., Berg, R. L., & Parsaik, A. (2020). Depression, anxiety and stress among young farmers and ranchers: A pilot study. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(1), 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00480-y

- Shortland, F., Hall, J., Hurley, P., Little, R., Nye, C., Lobley, M., & Rose, D. C. (2023). Landscapes of support for farming mental health: Adaptability in the face of crisis. Sociologia Ruralis, https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12414

- Stapleton, A., Russell, T., Markey, A., & McHugh, L. (2022). Dying to farm: National-level survey finds farmers’ top stressor is government policies designed to reduce climate change. figshare. Poster. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21681377.v1

- Syson-Nibbs, L., Robinson, A., Cook, J., & King, I. (2009). Young farmers’ photographic mental health promotion programme: A case study. Arts & Health, 1(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533010903031622

- The Princes’ Countryside Fund. (2021). National directory of farm and rural support groups. Retrieved April 2022, from https://www.princescountrysidefund.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Support-Groups-directory-2021-spreads-1.pdf

- Vanheusden, K., Mulder, C. L., van der Ende, J., van Lenthe, F. J., Mackenbach, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2008). Young adults face major barriers to seeking help from mental health services. Patient Education and Counselling, 73(1), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.006

- Vayro, C., Brownlow, C., Ireland, M., & March, S. (2022). A thematic analysis of the personal factors influencing mental health help-seeking in farmers. The Journal of Rural Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12705

- Wheeler, R., & Lobley, M. (2022). Health-related quality of life within agriculture in England and Wales: Results from a EQ-5D-3L self-report questionnaire. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13790-w

- Wheeler, R., & Lobley, M. (2023). Anxiety and associated stressors among farm women in England and Wales. Journal of Agromedicine. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2023.2200421

- Wheeler, R., Lobley, M., McCann, J., & Phillimore, A. (2023). ‘It’s a lonely old world’: Developing a multidimensional understanding of loneliness in farming. Sociologia Ruralis. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12399

- Yazd, S. D., Wheeler, S. A., & Zuo, A. (2019). Key risk factors affecting farmers’ mental health: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(23), 4849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234849

- Younker, T., & Radunovich, H. L. (2022). Farmer mental health interventions: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010244