ABSTRACT

This paper addresses a lacuna in animal geographies, extending the limits of this area of scholarship to include considerations of inanimate nonhuman animals. Drawing upon insights from animal geographies and interdisciplinary monster studies, a case is made that, in having effect and impact, monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures exert agency which can be harnessed to support the creation and commodification of tangible assets. The Scottish tourism industry has commodified legendary creatures that feature prominently in folklore, tradition and cultural heritage. The Loch Ness Monster, kelpies and unicorns are used to support three facets of contemporary heritage tourism, namely (i) Scotland the theme park, (ii) post-industrial commodification and economic regeneration and (iii) a search for the authentic, or subversive nationalism. There is potential for further studies to elucidate how monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures are intertwined with how people understand and engage with the world that they live in.

Introduction

Scotland’s rich folk tradition includes numerous accounts of animals with special powers (hare, raven, bull) and ‘a veritable bestiary’ (Harris, Citation2009, p. 8) of monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures which are often associated with specific places and environments. The Scottish bestiary includes shapeshifters such as selkies which could appear in animal or human form, hybrid human-animal creatures such as the wulver, nuckelavee and Blue Men of the Minch and fantastical animals such as the each-uisaig and dragons. Friendly but more often fearsome beasts have had a place in popular culture for centuries and some remain prominent today, featuring in, for example, fiction, film and works of art and contributing to the ‘unconscious discourse within which Scotland is a magical realm which transforms the stranger’ (MacArthur, Citation1993, p. 101). Many creatures within Scotland’s bestiary occupy a liminal space between reality and fiction, what Puglia (Citation2024, p. 3) describes as an epitome of ‘the interplay of the seen and unseen’. Some have become agents of twentieth and twenty-first century place (re)creation and vehicles through which places, or the nation as a whole, become imagined, marketed and exploited for economic gain.

Monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures have not featured in animal geographies scholarship which has, to date, focused on the animate nonhuman. This paper is an attempt to address this lacuna, to push the limits of what is established as the topics, methods and concepts associated with animal geographies. Drawing upon the animal geographies and monster studies literatures and using examples from heritage tourism, this contribution examines how monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures have been appropriated to sell Scotland’s cultural heritage. Relationships between human and such nonhuman agents are elucidated with reference to legendary creatures that appear in animal form, the Loch Ness Monster, the kelpie and the unicorn. The paper concludes with a call for animal geographies to embrace inanimate creatures – not in themselves ‘alive’ – as ones ‘in some way outside of the ordinary’ (Mittman, Citation2006, p. 6) whose presence, imaginative or otherwise, nonetheless shapes human lives in a myriad of ways.

Creating a place for monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures in animal geographies

Developments in animal geographies have been described in considerable detail elsewhere (see, for example, Wolch & Emel, Citation1995; Philo & Wilbert, Citation2000; Buller & Morris, Citation2007; Wolch et al., Citation2003; Buller, Citation2014). A short recapitulation is presented here before the comparatively recent interdisciplinary field of monster studies is introduced and arguments therein developed to present a case for an extension of animal geographies to include the monstrous, mythical and fantastical. An introduction to Scotland’s tourist industry, within which culture and heritage are prominent, is then presented. Tourism is of considerable importance to the national economy and has appropriated the monstrous, mythical and fantastical as vehicles for selling the nation.

Animal geographies

The zoogeography pursued by geographers such as Marion Newbigin in the early-twentieth century was largely concerned with mapping animal distributions and describing associations between these spatial patterns and place-based characteristics. This scholarship was followed by what Hovorka (Citation2018), borrowing from Urbanik, describes as a ‘second wave’ of animal geographies in the middle of the twentieth century, one that ‘features cultural perspectives examining animals as symbolic sites’ (Hovorka Citation2018, p. 454)which reflected Sauer-inspired writings about human-environment relations (c.f. Wolch et al., Citation2003). A ‘third wave’ emerged in the late-twentieth century, influenced by the cultural turn in human geography. ‘Third wave’ perspectives have, for example, highlighted animals as subjects in their own right, animal agency and human-animal engagements. This ‘revived animal geography’ considers ‘the complex entanglings of human-animal relations with space, place, location, environment and landscape’ (Philo & Wilbert, Citation2000, p. 4) and the ‘animal’s role in the social construction of culture and individual human subjects, and the nature of animal subjectivity and agency itself’ (Wolch et al., Citation2003, p. 199). Two senses of ‘place’ in relation to animals of concern for the new animal geography were identified by Philo and Wilbert (Citation2000). The first, animal places, refers to ‘the “place” which a particular animal, a given species of animal or even non-human animals in general can be said to possess in human classifications and orderings of the world’ (p. 6). The second, beastly spaces, is described as

ways in which animals, as embodied ‘meaty’ beings, often end up evading the places to which human seek to allot them … [and] begin to forge their own ‘other spaces’, countering the proper places stipulated for them by humans, thus creating their own ‘beastly places’ reflective of their own ‘beastly’ ways, ends, doings, joys and sufferings. (p. 13)

Monster studies

Monster studies is a relatively new academic field, one which took off following the publication of the edited collection Monster Theory: Reading Culture (Cohen, Citation1996). This literature offers definitions of ‘monster’, ‘mythical’ and ‘fantastical’, intersecting concepts and terms sometimes used interchangeably. The legendary monster is ‘a strange, frightening, or unusual human or creature, real or imaginary, believed or not believed, that is, at the time of the telling, purported but not scientifically verified to exist in our world’ (Puglia, Citation2024, p. 5). The mythical creature is ‘a supernatural being that is or was believed to be a material creature residing in a particular territory on Earth and described in folk-lore sources native to that territory’ (Beconytė et al., Citation2013, p. 54). The fantastical has etymological roots in the Greek ‘fantastic’ (φανταστικο or phantastikos) and describes, after Musharbash (Citation2014), being able to present or show (to the mind) or being imaginable (as opposed to being in the imagination). Belief in supernatural, monstrous and magical imaginable beasts has pervaded human societies for centuries and folklore recounts numerous tales that continue to be told today and many monsters, mythical and fantastical creatures appear in nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first century adult and children’s fiction, film and other forms of cultural content.

Mittman (Citation2012, p. 6) proposes that ‘whether we believe or disbelieve the existence of a phenomenon is not what grants it social and cultural force … the monster is known through its effect, its impact’. Erle and Hendry (Citation2020, p. 4) develop Mittman’s arguments, stating that ‘Mittman essentially suggests that when we experience monsters through the emotional effect (“impact”) they have upon us, they become a physical reality for us’. Reference to effect and impact, expressions of agency, and associated ‘real-ness’ of the monstrous aligns with Lorimer et al.’s (Citation2019) conceptualisation of ‘animal atmospheres’. This work draws on ideas associated with work on atmospheric geographies and ‘the nonhuman materialities of atmospheres and how these shape human experiences’ (p. 27). While inanimate animals do not themselves have an animal atmosphere, they can serve to create an ‘atmosphere’ for humans, a manifestation of their agency that is expressed via their imaginable existence.

A simple binary of real and unreal is problematic when reflecting upon the place of monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures in contemporary societies. Such creatures may simultaneously be real and fictional: they occupy a liminal space. The analogy of the Möbius strip, an idea used by Pile (Citation2014) to explore the blurred boundaries between the human and nonhuman as a way of understanding the ‘beastly minds’ of two of Sigmund Freud’s patients, is helpful in unpicking this binary. A Möbius strip is created by taking a strip of paper, twisting it and joining the ends together. This creates both ‘a single surface out of a strip which had two different sides … . [and] creates a three-dimensional figure out of a two-dimensional surface’ (Pile, Citation2014, p. 235). Pile notes that ‘there is always a distinction between one side and yet, on the other, there is paradoxically also only one surface’ (p. 232), and he uses this argument to illustrate uncertainty between what is animal and what is human in the minds of Freud’s patients. The single surface of the Möbius strip topologically ‘connects seemingly opposing ideas’ (p. 232). In the context of the monstrous, mythical and fantastical, on one plane of the M ö bius strip these creatures are imaginable and thus real, yet on another we can be certain that they do not exist. The third dimension creates topological space within which monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures are in our minds, shaping our affectual and emotional landscapes, exerting ‘real’ impacts.

If we accept that the effect of monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures is real and is the means through which they are known and have impacts upon individuals, communities and places, then there is indeed the opportunity for envisioning a whole range of new subject-matters that could be released through a constructive engagement between animal geographies and monster studies. Musharbash (Citation2014, p. 1), an anthropologist, observes that, while her discipline has not engaged to any great extent with ‘the burgeoning inter-disciplinary field of monster studies’, there is ample scope for this area of academic inquiry to develop and for scholars from other disciplines, including geography, to contribute too. The monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures that are the focus of this paper are indeed ‘real’ in that they are imaginable, exert effects and have impacts upon human societies. They have agency which is expressed in a myriad of human-inanimate creature encounters that often take place in particular spaces, places, specific locations, environments and landscapes. There is, therefore, a new opening here for animal geographies to embrace inanimate nonhuman creatures.

The appropriation of monstrous, fantastical and mythical creature to sell Scottish culture and heritage

Having outlined developments in animal geographies and used insights from monster studies to make a case for monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures being capable of effecting and impacting upon humans in the same way as do animate nonhuman animals, the paper now turns to illustrate how such creatures have been appropriated to sell Scottish culture and heritage. The commodification of animate nonhuman animals has been explored by animal geographers (Hovorka, Citation2017). Research in this established area includes studies of animal-based tourism, a focus extended here to include the commodification of imagined creatures in support of the Scottish tourism economy, illustrating an opportunity for inanimate yet ‘real’ creatures to feature in animal geographies.

The Loch Ness Monster, the kelpie and the unicorn are intimately associated with Scotland. Based on definitions presented above, all three, to various degrees, embody monstrous, mythical and fantastical elements. They are charismatic creatures with innate agency and/or agency ascribed to them by humans, individually and as communities, something occurring for centuries. They are entangled with three dimensions of contemporary Scottish heritage (developed from concepts discussed in McCrone et al., Citation1995): namely Scotland the theme park; post-industrial commodification; and a search for authentic or subversive nationalism. These are vehicles through which cultural commodities have been commercialised to support the tourism sector of the national economy. Although the dimensions of Scottish heritage are cross-cutting in nature, in this paper Loch Ness and the Loch Ness Monster are deployed to illustrate Scotland the theme park, the kelpie is used to illustrate post-industrial commodification and economic regeneration, and the unicorn illustrates a search for the authentic or subversive nationalism, the latter defined as ‘a hidden kind of nationalism, reminding the reader of stories once told’ (Ismangil, Citation2019, p. 241).

Tourism and the heritage industry

Tourism is one of the largest, and fastest-growing, global industries (Edensor, Citation2009; UN Tourism, Citationno date) and, despite being hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic and other recent global shocks such as conflict between Russia and Ukraine (OECD, Citation2022), it remains of considerable importance to the economies of numerous nations (c.f. data available from the UN Tourism Data Dashboard). Cultural heritage tourism is a distinct segment of global tourism, part of wider, dynamic, cultural processes that create, sustain and reframe identities and the meaning(s) of, for example, environments, places, historic buildings, monuments and artefacts. Travel in search of ‘authentic’ representations is, Light (Citation2015, p. 14) suggests, one of the ‘most conspicuous way[s] in which history and the past are appropriated and commodified for economic gain in contemporary societies’. A heritage ‘industry’ is at the vanguard of cultural commercialisation.

Tourism is one of the most important sectors of the Scottish economy, crucial to the economic vitality of many urban and rural communities. Pre-pandemic, tourism contributed approximately £6bn of Scottish GDP (5% of the total) and supported around one in twelve jobs (Tourism Leadership Group, Citation2018). The Scottish tourism industry plays on the nation’s cultural heritage, selling visions of sublime landscapes, romantic ruins, and a ‘Scottish’ identity designed to attract domestic and international visitors, the latter group including numerous members of the Scottish diaspora enticed to return to their ancestral homeland (Bhandari, Citation2016). Many tourists visit destinations across Scotland hoping to see iconic species of birds and mammals, some of which have a high profile as a result of being used, as is the case of Highland cattle for example, in images emblazoned upon tourism marketing materials and merchandise sold in popular tourist destinations. The monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures of Scottish folklore have also, as illustrated below, been mobilised within Scotland’s tourism industry becoming intimately associated with representations and the commodification of specific locations or types of place.

Loch Ness and the Loch Ness Monster: Scotland the theme park

Scotland’s landscape and popular iconography are used to advertise a version of Scotland that will attract mass market tourism. Tartanry, Landseer’s Monarch of the Glen, Balmorality and Brigadoon underpin ‘Scotland the theme park’, a highly successful business model based on selling manufactured representations of the nation. Forays into myth and fantasy are integral to this promotion of the nation’s heritage, including the appropriation of Nessie, Scotland’s international superstar fantastical creature. The first recorded sighting of ‘something’ associated with Loch Ness was in AD565 when St Columba reportedly saved a man from a creature swimming towards him in the River Ness (Parsons, Citation2004). Numerous sightings of a fantastical creature, an niseagi, followed (Breton, Citation2001), as did sightings of fearsome water creatures lurking in other large fresh water bodies such as Loch Morar’s a’Mhorag and Loch Tay’s pisces sine intestines (fish without a belly) inscribed on the mediaeval Gough Map of Great Britain (see http://www.goughmap.org/).

The commodification of a monstrous creature living in Loch Ness dates to the early-1930s when the editor of the Inverness Courier, Evan Barron, is reported to have coined the term ‘monster’ to describe a strange spectacle observed in Loch Ness in April 1933 by the then manageress of the Drumnadrochit Hotel. Measures to protect the unknown ‘thing’ in Loch Ness were put in place,Footnote1 and the observation was followed a year later by publication of the infamous ‘surgeon’s photo’Footnote2 (see ). Other well-publicised images have followed (many later outed as hoaxes). Coupled with improved road infrastructure in and around Loch Ness, the growth of leisure time in post-war Britain stimulating domestic tourism and, more recently, cheap air travel facilitating international travel, mass-market tourism based around the monster has developed. Hundreds of thousands of visitors have travelled to Loch Ness in the hope of catching a glimpse of Nessie. Academic researchers have also been drawn to Loch Ness, seeking scientifically credible explanations for purported sightings of a monster. Although these efforts have led to environmental conditions in and around Scotland’s second deepest loch being better understood, no evidence of Nessie has been found – so far.

Figure 1. The Surgeon’s photograph and other representations of the Loch Ness Monster. Clockwise from top left: The Loch Ness Centre, Drumnadrochit (© The Loch Ness Centre); the ‘Surgeon’s photo’ published on the front page of the Daily Mail, 21st April 1934; Nessie soft toys on sale in an Edinburgh souvenir shop, summer 2023 (© Lorna Philip); cover image of The Treasure of the Loch Ness Monster reproduced by kind permission of Floris Books, Edinburgh.

Nessie is big business, estimated to be worth nearly £41 million a year to the Scottish Economy (Press and Journal, 2018). Two of the top ten paid visitor attractions in Scotland in 2019 were Loch Ness or Nessie-themed: Urquhart Castle, located on a promontory overlooking Loch Ness, attracted 447,581 visitors and Loch Ness by Jacobite cruises and tours attracted 321,980 people (Visit Scotland, Citation2020). The recent £1.5million investment to renovate the Loch Ness Centre at Drumnadrochit (BBC News, Citation2023) is indicative of revenue expected to flow into this business from future entrance fees. For those unable to visit Loch Ness, tourist attractions and retail outlets across Scotland sell Nessie-themed souvenirs, providing additional opportunities for further commercial gain to be made from this monstrous creature.

The Kelpies: post-industrial commodification and economic regeneration

There is a long standing tradition in Scottish folklore to regale tales where the power of water presents both a supernatural threat and a means of defence (Harris, Citation2009), sometimes associated with freshwater and marine ‘monsters’. Cultural artefacts, such as Pictish stone carvings, include figurative illustrations of both recognisable and inexplicable fantastical aquatic creatures. One such beast is the kelpie, whose powers are referred to in stanza twelve of Robert Burn’s 1788 poem Address to the Deil:Footnote3

When thowes dissolve the snawy hoord,

An’ float the jinglin icy-boord,

Then water-kelpies haunt the foord,

By your direction;

An’ nighted trav’llers are allur’d

To their destruction

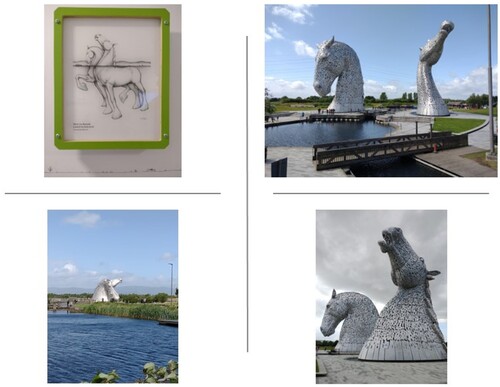

The power of the kelpie and its association with water underlies the tourism-led regeneration of Helix Park near Falkirk, one of numerous locations where the cultural heritage of once thriving industrial communities has been exploited in efforts to regenerate towns and cities across the UK and beyond. Opened in 2014, Helix Park is important to the ‘reimagining of the area [Falkirk] evidencing a symbolic interplay between the past, the present and the future’ (McKean et al., Citation2017, p. 742). Helix Park occupies a site within the estate of Scottish Canals where the industrial and transport heritage of the Forth and Clyde and the Union canals has been reimagined to develop a leisure and tourism attraction designed to support economic development in the Falkirk area. A unique attraction at Helix Park is the Kelpies, a pair of 100 foot high horse heads (see ). Thought to be the largest equine sculptures in the world, these spectacular representations of a legendary creature represent the magical power of the malevolent kelpie of Scottish folklore, geographically re-positioned from their purported home in rural Scotland to a post-industrial location. At Helix Park they also symbolise the strength of the heavy horses that drove traffic on Scotland’s canal network (and other industrial and agricultural activities), a tangible representation of the kelpie’s supernatural power.

Figure 2. The Kelpies at Helix Park. Sources: all © Lorna Philip. Top left is a photograph of one of a number of sketches by Andy Scott displayed at the Helix Visitor Centre, the caption for which is What lies beneath, a sketch by Andy Scott © Andy Scott Public Art.

Quoted in The Scots Magazine (n.d., paragraph 7), the sculptor who created the landmark structures, Andy Scott, said that:

the original concept of mythical water horses was a … starting point … I visualised the Kelpies as a monument to the horse and a paean to the lost industries of the Falkirk area, … I also envisaged them as a symbol of modern Scotland - proud and majestic, of the people and the land.

Marketed by tourism bodies and promoted by tours of the maquettes on which the sculptures are based,Footnote4 the Kelpies have quickly become iconic landmarks. Scottish Canals (Citation2023) estimate that around 50 million people worldwide see an image of the Kelpies each year and an estimated 40 million sightings of the Kelpies have been made by those travelling on the M9 motorway (BBC News, Citation2024). Pre-pandemic, Helix Park was in the top 15 most popular visitor destinations in Scotland (McKean et al., Citation2017). Post-pandemic visitor numbers increased significantly, to 930,000 in 2021 (Visit Scotland, Citation2022). With the Kelpies thought to have attracted 7.3 million visitors to Falkirk and Grangemouth (BBC News, 2024), it is unsurprising that Falkirk Council (Citation2023, p. 6) describes Helix Park and the Kelpies as ‘hero’ attractions ‘capable of drawing both international and domestic visitors in their own right’. The economic contribution of the Kelpies is considerable, their importance to the post-industrial economy of central Scotland unquestionable.

The unicorn: search for the authentic, or subversive nationalism?

The Scottish tourism industry exploits historic buildings, locations associated with significant historical events, and museums and galleries displaying Scottish artefacts or items which help to tell stories of Scotland’s past, present and relationships with the rest of the world today and through time. These attractions allow visitors to engage with an authentic past, one where heritage gives legitimacy to a distinct national identify, and to experience a form of subversive nationalism, being reminded of stories about people, places and artefacts in the context of the everyday act of visiting heritage locations, activities via which nationalism, as Nairn (Citation1981, p. 144) suggests, ‘involves the reanimation of one’s history’. It is in this guise that unicorns come to the fore.

The unicorn, a white, horse-like creature with a large horn protruding from the forehead, has an ancient pedigree. Documented in Hebrew scripture, which ‘mentions single-horned beasts called the re’em, surely meaning unicorns’ (Boehm, Citation2020, p. 7), unicorns were also referred to by the Greek philosophers Cteslas and Aristotle, and by the Roman writer Pliny the Elder. The unicorn appeared in early Christian literature, in the Bestiary (or Book of Beasts) which ‘advanced a complicated metaphor in which Jesus is “the spiritual unicorn”, citing biblical passages to bolster the argument’ (Boehm, Citation2020, p. 9). Aligned with this Christian reference, unicorns became associated with mediaeval chivalry, symbolic of purity, virtue, fortitude and strength. Unicorns became explicitly associated with the Scottish monarchy in the early fifteenth century:

… in 1426 … James I appointed a Unicorn Pursuivant and the crown used a unicorn signet for official matters between 1427 and 1462 … during James III’s reign. … [From 1484] the royal arms were depicted sometimes supported by unicorns, sometimes by lions, and sometimes by a unicorn standing behind a lion on each side of the shield. The unicorn in these royal arms was, more often than not, shown earning a crown-shaped collar with a long chain … to show that this notoriously proud and haughty beast had been tamed and bent to serve the Scottish crown. (Stevenson, Citation2004, p. 12)

Unicorns appear in sculptural and pictorial form at locations across Scotland, guarding prominent landmarks and identifying buildings and organisations associated with monarchy and institutions of the crown and state. They are also portrayed on numerous objects d’art held in public and private collections and feature on coats of arms and other quasi-heraldic devices. These representations are a far cry from the pastel coloured, glitter adorned, highly gendered representations of unicorns seen on children’s toys and clothing.

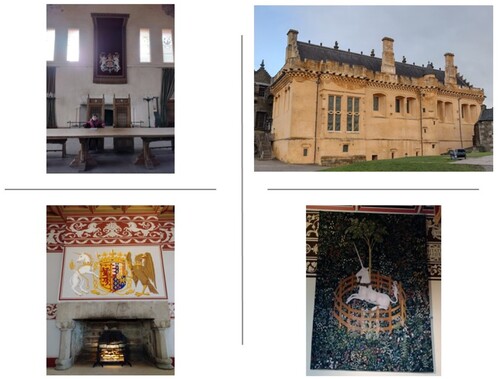

The unicorn as a representation of Scotland’s pre-Union of Crowns identity is prominent at a number of historic properties, including Stirling Castle, a monument in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. Attracting 609,698 paying visitors in 2019, tourism associated with Stirling Castle makes a notable contribution to the total tourism related GVA (gross value added) in the Stirling local authority area, £129.5 million in 2019 (Visit Scotland, Citation2020). The ornately decorated Royal Palace built by James V in the 1530s was part of moves to enhance ‘the “imperial” status of Stewart monarchy’ (Macdougall, Citation2001, p. 354) and intended to be ‘a symbol of Stewart power’ (Watson & Lynch, Citation2001, p. 592). In James V’s buildings the pedigree of the Stuart dynasty was flaunted as being far superior to that of the newcomer Tudor monarchs of England, while dynastic links to continental Europe, France in particular, were portrayed. Unicorns as symbols of monarchy feature prominently on the coats of arms for James V and his second wife, Mary of Guise, which adorn the walls of the royal chambers. Modern reproductions of seven Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries, thought to have either been purchased by James V in France in 1536–1537 or brought to Scotland by James V’s first wife, Madeline of Valois in 1537, as part of her trousseau (Boehm, Citation2020), also hang on the walls of these rooms. Unicorns are prominent in other areas of the castle complex: for example, golden unicorns sit atop the roof of the Great Hall and embroidered textiles displaying a pre-1603 variant of the Royal Arms of Scotland, featuring a central lion rampantFootnote6 guarded by two unicorns, hang on the interior walls (see ).

Figure 3. Stirling Castle unicorns. Sources: all © Lorna Philip. Clockwise from top left: canopy above the High Table in the Great Hall, embroidered with the Royal Arms of Scotland; exterior of the Great Hall which is surmounted by two unicorns; the Unicorn in Captivity, one of the Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries on display in the royal apartments; the Royal Standard of Mary of Guise in the Queen’s Apartments.

Stirling Castle’s prominent displays of the unicorn, symbol of chivalry, monarchical power and patronage, on its own and in combination with the lion rampant, reference a supposedly authentic past and illustrate how a mythical beast is entangled with Scotland’s late-mediaeval history. Specifically, they are represented as they were by the Stuarts in the sixteenth century, before the Union of Crowns in 1603, after which James VI and I quartered the Royal Arms of Scotland with those of England and Ireland. From 1603 the Scottish Royal Arms could be depicted surrounded by a unicorn to the left and a lion rampant to the right and they are illustrated thus at other historic properties associated with the monarchy in Scotland, including Edinburgh Castle. As used at Stirling Castle, however, the royal unicorn is symbolic of a pre-1603 Scottish cultural and political identity, and here their presence and interpretation in information available to visitors is a reminder of this earlier period of Scotland’s history. Interpreted thus, the unicorn as appropriated within this heritage tourism site is a vehicle through which a retelling of stories of Scotland’s past is achieved. Conveying James V’s propaganda messages of the 1530s, those visiting the Royal Place today experience a form of subversive nationalism. With Stirling Castle having been in the top three most visited paid attractions in Scotland for years, the many representations of the unicorn at this site and what they mean – with small but significant variations – in the context of Scotland’s history have been consumed by millions of domestic and overseas tourists.

Discussion and concluding comments

The monstrous, mythological and fantastical are intangible assets that can be mobilised to support the creation and exploitation of tangible assets (after Berk, Citation2016). The examples of the commodification of the Loch Ness Monster, the kelpie and the unicorn as a means of supporting heritage tourism, as presented in this paper, illustrate a tangible impact of imagined creatures. Wolch et al. (Citation2003, p. 188) observed that nonhuman animals ‘leave imprints on particular places, regions and landscapes over time, prompting studies of animals and places … and places in the grip of powerful forces of economic or social change’. In the Scottish context, Nessie, the kelpies and the unicorn speak to this observation, extending our gaze from the animate animal to the inanimate yet imaginable creature.

Tourists are attracted by the charisma of the Loch Ness Monster, the kelpie and the unicorn; these creatures express, to various degrees, the three types of nonhuman charism articulated by Lorimer (Citation2007), namely ecological, aesthetic and corporeal charism. Nessie has ‘jizz’, defined by Lorimer (Citation2007, p. 917) as ‘the unique combination of properties of an organism that allows its ready identification and differentiation from others’. Nessie’s ecological context is part of her attraction. She can only be found in one location, Loch Ness, whose mountainous surrounds and mysterious depths are part of an assemblage that creates an ecological charisma around her. Hunts for this monster take visitors to Loch Ness where proximity to the water can provide visitors with a moment of enchanting proximity and an ‘I will see her’ sense of anticipation, a manifestation of a strong affective response to the monstrous. The Kelpies sculptures at Helix Park are a reinvention of a fantastical creature about whom stories have been told for centuries. There is a liminality to the sculptures: they concurrently express the fantastical qualities of the kelpie of legend and the appearance and strength of the heavy horses that powered the canals and associated heavy industrial activities of central Scotland. Andy Scott’s creations have created a twenty-first century manifestation of the fantastical that offers aesthetic charisma to those who visit them. Their aesthetic charisma extends to representations in visual media, images with the power to lure visitors to view the massive sculptures ‘in the flesh’, in the unique ecological context where they arise from the waters of the Forth and Clyde canal. The mythical unicorn has multiple forms of charisma. Unicorns may exude a cute and cuddly aesthetic and corporeal charism in the form of children’s soft toys or cartoonish depictions on clothing. In contrast they may also be fierce, dangerous, or benevolent, all dimensions of numerous chivalric representations and what their use as symbols of monarchy is designed to convey. The sculptural and pictorial bodies of royal unicorns found across Scotland, be they atop mercat crosses in Royal Burghs or painted on the walls of royal properties, are a corporeal expression of their charisma and reminders of elements of Scotland’s past. Their charisma can capture the imagination and inspire visitors of all ages to undertake their own unicorn hunt.

As Lorimer (Citation2007, p. 927) noted, the charisma of animals can be ‘magnified through marketing and is open to a degree of construction’. This argument can be extended to the charisma of monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures: in the case of Scotland the charisma of Nessie, the kelpie and the unicorn has been very successfully constructed and curated by heritage and tourism executives and marketing teams and exploited to ‘sell’ these creatures and the places with which they are associated. They have become vehicles through which mass market tourism, Scotland the theme park, is promoted. Post-industrialisation place-(re)creation efforts are supported and accompany presentations of the nation’s history. The thousands of annual visitors to Loch Ness and Helix Park indicate an appetite amongst the public to engage with Scotland’s legendary creatures – and to spend money in doing so. If monstrous, mythical and monstrous creatures can have impacts such as this in Scotland, they are likely to have similar impacts arising elsewhere.

This paper set out to address a lacuna in animal geographies, to extend the limits of this area of scholarship to include inanimate nonhuman animals, specifically monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures. Such creatures are ‘real’ in that they are meaningful to, effect and have impacts upon individuals and communities. They exert agency, albeit agency based upon humanly-imagined entities. In exploring how the Loch Ness Monster, the kelpie and the unicorn have been commodified within the Scottish tourism industry, an example of the potential for animal geographies to embrace the agency of monstrous, mythical and fantastical creatures in other animal geographies research is provided. At the same time, links between animal geographies and inter-disciplinary monster studies are opened up which in future could lead to more geographers ‘taking seriously how the monstrous manifests locally and documenting the socio-culturally specific ways in which people relate to monsters reveals how people understand themselves, their world, and their position within it’ (Musharbash, Citation2014, p. 2).

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks are due to Chris Philo for providing me with an opportunity to engage with the subject matter of this paper, developing ideas that were outlined in an article I contributed to the Royal Scottish Geographical Society’s newsletter The Geographer (Philip, Citation2021). The genesis of those ideas was musings about the agency of the Loch Ness Monster presented in a short co-authored piece, published under a pseudonym, in the Royal Geographical Society Postgraduate Forum’s publication, Praxis (Gordon & Tonic, Citation1997). A copy of the Praxis article is available on request. Thanks are also due to the two anonymous reviewers and the Special Issue editors whose helpful and supportive comments informed the revised version of the paper published in this special issue. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In December 1933 excitement about the presence of a monster prompted the then Secretary of State for Scotland to introduce protection in law for the ‘thing’ living in Loch Ness (Breton, Citation2001). In 2001, Scottish Natural Heritage (now NatureScot) prepared a code of practice designed to offer protection to any new species found in Loch Ness, guidance that would cover the discovery of Nessie and which remains in place today (BBC News, , Citation2018).

2 British surgeon Colonel Robert Wilson claimed to have taken the photograph reproduced in on 19th April 1934. Interpreted by many as evidence that the Loch Ness Monster was a dinosaur-like creature, the photograph was circulated world-wide but, 60 years later, was revealed to be a hoax. It was actually a photograph of a toy submarine with a carved sea-serpent’s head attached floating in the water.

3 From The Poetical Works of Robert Burns, 1994, Senate Press Ltd.

4 The maquettes, one tenth-sized models, were created by sculptor Andy Scott and used by the artist to model the full-sized, 300 tonne sculptures. Over a six year period they toured the globe, being exhibited at locations including New York, Chicago, Milan, London and at the 2014 Ryder Cup. They have also been exhibited across Scotland.

5 Note that two spellings may be used to refer to the Stewart/ Stuart dynasty. The latter spelling became common following the Union of the Crowns and has been used in this paper except where a different spelling has been used in in-text quotations from the literature.

6 The English Royal Arms of the time also used the lion as a symbol of monarchy but in the form of three lions passant guardant. The Royal Arms of the English Tudor monarch Henry VIII, James V’s contemporary, were represented guarded by a lion to the left and a dragon on the right.

References

- BBC News. (2018). What happens if someone catches the Loch Ness Monster? July 6, 2018. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-44519189.

- BBC News. (2023). Nessie visitor centre undergoing £1.5 m renovation. January 5, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-64172845.

- BBC News. (2024). The Kelpies: Ten years of the towering horse sculptures. April 27, 2024. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cpvgqnd3nxzo.

- Beconytė, G., Eismontaitė, A., & Žemitienė, J. (2013). Mythical creatures of Europe. Journal of Maps, 10(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2013.867544

- Berk, F. M. (2016). The role of mythology as a cultural identity and a cultural heritage: The case of phrygian myhtology. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 225, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.06.009

- Bhandari, J. (2016). Imagining the Scottish nation: Tourism and homeland nationalism in Scotland. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(9), 913–929. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.789005

- Boehm, B. D. (2020). A blessing of unicorns: The Paris and cloisters tapestries. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Summer 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/A_Blessing_of_Unicorns.

- Breton, J. (2001). Le kelpie, ou les monstres lacustres / The Kelpie, or the lake monster. Études écossaise, 7(7), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesecossaises.3461

- Buller, H. (2014). Animal geographies I. Progress in Human Geography, 38(2), 308–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513479295

- Buller, H., & Morris, C. (2007). Animals and society. In J. Pretty, A. S. Ball, T. Benton, J. S. Guivant, D. R. Lee, D. Orr, M. J. Pfeffer, & H. Ward (Eds.), Sage handbook of environment and society (pp. 471–484). Sage.

- Cohen, J. J. (Ed.). (1996). Monster theory: Reading culture. University of Minnesota Press.

- Edensor, T. (2009). Tourism. In R. Kitchen & N. Thrift (Eds.), International encyclopedia of human geography (pp. 301–312). Elsevier.

- Erle, S., & Hendry, H. (2020). Monsters: Interdisciplinary explorations in monstrosity. Palgrave Communications, 6(53), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0428-1

- Falkirk Council. (2023). Falkirk Area tourism strategy 2023-2028. https://www.falkirk.gov.uk/services/tourism-visitor-attractions/tourism-strategy.aspx.

- Gibbs, L. M. (2020). Animal geographies I: Hearing the cry and extending beyond. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 769–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519863483

- Gordon, L., & Tonic, M. (1997.). Lochs, monsters and geography: Towards an understanding of non-humans and place creation. Praxis, 34(Spring 1997), 5–7.

- Harris, J. M. (2009). Perilous Shores: The unfathomable supernaturalism of water in 19th - Century Scottish folklore. Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkein, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature, 28(1, article 2), 5–25. https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol28/iss1/2/.

- Hovorka, A. J. (2017). Animal geographies I: Globalizing and decolonizing. Progress in Human Geography, 41(3), 382–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516646291

- Hovorka, A. J. (2018). Animal geographies II: Hybridizing. Progress in Human Geography, 42(3), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517699924

- Ingold, T. (1988). Introduction. In T. Ingold (Ed.), What is an animal? (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

- Ismangil, M. (2019). Subversive nationalism through memes: A Dota 2 case study. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 19(2), 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/sena.12298

- Light, D. (2015). Heritage and tourism. In E. Waterton, & S. Watson (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of contemporary heritage research (pp. 144–158). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lorimer, J. (2007). Nonhuman charisma. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 25(5), 911–932. https://doi.org/10.1068/d71j

- Lorimer, J., Hodgetts, T., & Barua, M. (2019). Animals’ atmospheres. Progress in Human Geography, 43(1), 26–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517731254

- MacArthur, M. (1993). ‘Blasted heaths and hills of mist’: The Highlands and Islands through travellers' eyes. Scottish Affairs, 3(1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.1993.0026

- Macdougall, N. (2001). James V. In M. Lynch (Ed.), The Oxford companion to Scottish history (pp. 353–354). Oxford University Press.

- McCrone, D., Morris, A., & Kiely, R. (1995). Scotland – The brand. The making of Scottish heritage. Edinburgh University Press.

- McKean, A., Harris, J., & Lennon, J. (2017). The Kelpies, the Falkirk Wheel, and the tourism-based regeneration of Scottish Canals. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(6), 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2146

- Mittman, A. S. (2006). Maps and monsters in medieval England. Routledge.

- Mittman, A. S. (2012). Introduction: The impact of monsters and monster studies. In A. S. Mittman & P. Dendle (Eds.), The Ashgate research companion to monsters and the monstrous (pp. 1–16). Ashgate. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:27705/.

- Musharbash, Y. (2014). Introduction: Monsters, anthropology, and monster studies. In Y. Musharbash & G. H. Presterudstuen (Eds.), Monster anthropology in Australasia and beyond (pp. 1–24). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nairn, T. (1981). The break-up of Britian: Crisis and neo-nationalism (2nd ed.). Verso.

- OECD. (2022). OECD tourism trends and policies 2022. https://www.oecd.org/cfe/tourism/oecd-tourism-trends-and-policies-20767773.htm.

- Parsons, E. C. M. (2004). Sea Monsters and mermaids in Scottish folklore: can these tales give us information on the historic occurrence of marine animals in Scotland? Anthrozoös, 17(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279304786991936

- Philip, L. (2021). Imaginative animal geographies: Scotland’s mythical beasts and monsters. The Geographer (newsletter of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society). Spring 2021, 33. https://www.rsgs.org/the-geographer.

- Philo, C., & Wilbert, C. (2000). Animal spaces, beastly places: An introduction. In C. Philo & C. Wilbert (Eds.), Animal spaces, beastly places: New geographies of human-animal relations (pp. 1–36). Routledge.

- Pile, S. (2014). Beastly minds: A topological twist in the rethinking of the human in nonhuman geographies using two of Freud’s case studies, Emmy von N. and the Wolfman. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(4), 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12017

- Puglia, D. (2024). The (mostly) unseen world of cryptids: Legendary monsters in North America. Humanities, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13010001

- The Scots Magazine. (n.d.). Scotland’s Kelpies. https://www.scotsmagazine.com/articles/scotlands-kelpies/.

- Scottish Canals. (2023). The story of the Kelpies. https://www.scottishcanals.co.uk/destinations/the-kelpies/the-story-of-the-kelpies/.

- Stevenson, K. (2004). The unicorn, St Andrew and the thistle: Was there an order of chivalry in late medieval Scotland? The Scottish Historical Review, LXXXIII:(215), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.3366/shr.2004.83.1.3

- Tourism Leadership Group. (2018). Tourism in Scotland. The economic contribution of the sector. Scottish Government. https://www.gov.scot/publications/tourism-scotland-economic-contribution-sector/documents/.

- UN Tourism. (no date). Why tourism? https://www.unwto.org/why-tourism.

- Visit Scotland. (2020). Insight department: Key facts on Tourism in Scotland 2019. https://www.visitscotland.org/research-insights/about-our-industry/statistics.

- Visit Scotland. (2022). Loch Lomond, The Trossachs and Forth Valley industry update 14/10/2022. https://www.visitscotland.org/news/2022/forth-valley-industry-update-oct.

- Watson, F., & Lynch, M. (2001). Stirling/ Stirling Castle. In M. Lynch (Ed.), The Oxford companion to Scottish history (pp. 591–593). Oxford University Press.

- Wolch, J., & Emel, J. (1995). Guest editorial: Bringing the animals back in. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 13(6), 735–760. https://doi.org/10.1068/d130735

- Wolch, J., Emel, J., & Wilbert, C. (2003). Reanimating cultural geography. In K. Anderson, M. Domosh, S. Pile, & N. Thrift (Eds.), Handbook of cultural geography (pp. 185–206). Sage.