ABSTRACT

Using an ethnomethodological approach, we examine a particular case of a dog and its handler learning the ‘lean’ command. In this scene of instruction, we come upon a place where the uses of a word are taught to both dog and human. Revisiting Vicki Hearne’s influential book on animal training, we reflect on animals in conversation with their trainers, and the interconnected problems of understanding and of a dog’s specific rights. We describe the establishing of a new command as a body position, location and duration. The opening and closing of a door, as part of learning the new command, poses a puzzle of both instruction and rights for the dog as pupil. Our findings begin to contribute to the ‘missing what’ of dog training and question the limits of animal geographies in relation to the ethics in, and of, training and education with animals. In addition, we show how animal geographers can learn from and describe the public availability of intersubjective practices. Specifically, we describe the witnessable organisation of learning new commands, as part of which, we acknowledge and are attentive to the dog’s work, thereby contributing to studies of animal training, cross-species communication and classrooms.

Understanding and confusion in the classroom

After one of many unsuccessful attempts to teach Star a new command, ‘lean’, Jenny, her friend, handler and amateur trainer, encourages her to continue:

C’mon

Oo:: ((High pitched yelp))

Are you confused

((looks at Jenny))

When pupils say to their teachers, ‘I’m a bit confused’, they begin to express a problem with their understanding of the lesson. In this case, the pupil expresses their confusion, without words, and it is the teacher who recognises and formulates, in hearable talk, their trouble. It is in this scene of a classroom encounter, one of instructing and responding, of understanding not yet reached, of the related and paired rights of pupils and teachers, that we will situate our inquiry.

There is another pertinent feature of the members of this classroom - some of them are dogs: dogs that are nevertheless pupils, committed to trying to provide a good enough response and paying attention to their teacher, in order to find out if they did provide it. Dogs cannot speak words, yet they are expressive and conversational participants, they are responsive to voiced, whistled or gestured requests and they come to understand and make moves in language games (Mondémé, Citation2022). They make guesses, they try out what they know how to do already, they provide correct and incorrect responses, they show their skill, their experience and they learn from their teachers through instructions, assessments, and corrections.

Star’s confusion, and Jenny’s acknowledgment of it, hint at what we want to examine: learning a new instruction, problems of understanding and problems of rights. We, as inquirers into human-dog classrooms, are trying to learn from an exemplary and particular case, elements of how assistance-dogs are trained and how handlers of assistance-dogs are trained. With the widened sense of language, of action and responsiveness that emerges from ethnomethodology and conversation analysis, we are interested in the conversations, the gestures, the handling of objects and more that constitute training in, and as, a classroom’s work. To immediately head off a common misunderstanding of ethnomethodology, it is not a methodology, it is the study of members’ methods and is an approach in human geography scholarship which has been influenced by ‘ordinary language philosophy’ (Laurier & Bodden, Citation2020). Its conception of language as action (and action as language) is particularly germane to describing how we understand teaching and learning involving non-human animals.

In breaching the established limit drawn by animal geographies around language and granting rights, we have re-traced the incursion of that same limit by Vicki Hearne, almost forty years ago. Direct work based on Hearne’s incursion is surprisingly absent from animal geographies, given how deeply her ideas influenced early animal studies, including Donna Haraway’s work, which have, in turn, shaped animal geographies. Her work’s absence reveals animal geographies’ wariness around Hearnes’s (Citation2007) central concern with the shared language of humans and non-human animals, her response to the threat of scepticism and scepticism’s interconnection with anthropomorphism.

Our study of a human-dog classroom is of its ‘missing what’, as ethnomethodology has described the absence of descriptions capturing the particularities of practices that constitutes sites of instruction and education (Macbeth, Citation2011). Consequently, in the lesson that we will examine, our focus is on the particularities of teaching and learning the ‘lean’ command through repetitions and variations in, and around, the pupil’s struggle to understand, alongside the handler’s struggle to teach. While these repetitions inevitably involve wrong responses, they also become the sites for the pupil to claim their rights to their very struggle around what the trainer is asking of them.

In the paper, we will bring together animal geographies with ordinary language philosophy and ethnomethodological studies of classrooms. Hearne’s ideas provide one place for doing this and the analyses of video recording from an episode in Jamie’s study of assistance-dog training provide a second place. One way that we are working at the ‘limits of animal geographies’ is by attending to understanding as it is locally accomplished in actions and responses.

Our concern with the particular case is a concern with and commitment to members’ perspectives and reasoning, and, indeed, the granularity with which they produce, recognise, and account for, what they do when they are teaching and learning (Lindwall & Lymer, Citation2024). It is no coincidence that Hearne’s study of training, stocked with particular cases, is as popular with animal trainers as it is in animal studies. Particular cases provide just what it is that animal training involves from the perspective of a trainer while also providing for teaching the ordinary language philosopher. Hearne’s ordinary language philosophy is an invitation to animal training for the theorist and an invitation to theorising for the animal trainer. It questions the assumptions of how we think about animal rights and how we encounter dogs (as well as chimpanzees, horses and cats) through our generalising theories about the dog rather than as a matter of encountering just this dog: a dog as someone else who we need to establish a relationship with before we have the right to greet them, let alone train them.

Responding to Hearne’s call

It is in Hearne’s influential book Adam's Task where we start our foray into animal training. Two of Hearne’s central premises were: first, to rethink rights in terms of animals being granted and earning them; and second, to recognise how animals speak to us by answering our calls, where their answering is, often enough, questioning those calls. Hearne builds her argument on the failures of our appreciation of an animal’s knowledge and acknowledgment of us through descriptions of her training practice and of the mistreatment of dogs, horses, apes and cats. Her approach emerges from the ordinary language philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein and Stanley Cavell. Both Wittgenstein’s idea of language games and Cavell’s related (Citation1999) emphasis on acknowledgement are called upon to help us understand how animals are talked with and to rather than talked at.

There is a tiny lexicon of words that are available for addressing dogs, although, we should note, there are rather more dog words than the set of four words used by Wittgenstein in his builder’s example. Wittgenstein’s builders expressing themselves and accomplishing their building work is used by him to show how even a single word can be used to accomplish many things (similarly on ‘dog words’, see Fraser, Citation2019). The builders’ dialogues are instructive to us about the varied uses of single words, their indexicality and the limits of an idea of a pre-fixed meaning of a word. The notion of a language game is central to Wittgenstein’s inquiries and is one that asks us to learn from simplified cases. Dogs and their trainers find the intelligibility of ‘sit’, ‘fetch’, ‘drop’ and similar in, and as part of, language games. Animal training is instructive in, and as, language games for animal geographies’ understanding of how we do things together with non-human animals.

For Hearne, training extends an invitation into shared language games for humans and animals. For both human trainer and animal trainee, it is in extending their shared language that responsibility, honesty and rights become possible. Hearne raises the pervasive threat of scepticism that surrounds what we think are the limits of our knowledge of animals. She argues, perhaps unexpectedly and a little confusingly, given her commitment to animals as knowable, that we are not sceptical enough about dogs and horses. Drawing on Cavell, Hearne writes that a horse or a dog confronts us with ‘our unreadiness to be understood’ and ‘theirs is our best picture of a readiness to understand’ (Cavell, quoted in Hearne, Citation2007, p. 115). Hearne goes on to note that dogs and horses, despite our denial of it, know us well, yet they know us so ‘without yielding their own volition’ (p. 115). In this paper, we aim to pursue training, as Hearne did, in training encounters where we witness the animal’s volition and their readiness to understand, although we will go on to examine confusions around instructions and rights that lead to this readiness becoming exhausted, and not just for the dog as pupil.

The right to command, for Hearne an acquired human right, emerges in the details of just how a command is given. She provides the example of a dog known for its excellence in answering the ‘down’ command who, when bribed with a food treat, got up and walked away. To bribe was to lose the right to command. To talk with and command an animal requires mutual respect between trainer and pupil.

We do not have the space here to track the full uptake of Hearne in animal studies and philosophies of animal rights. Two of the significant figures, though, are Cary Wolfe (Citation2003) and Donna Haraway (Citation2003, Citation2007). Wolfe connects Hearne’s idea of extending language, inviting nonhumans into language, to similar invitations to animals in the theorisations of Lyotard, Levinas and Derrida. Wolfe is critical of Hearne for relying too heavily on Wittgenstein’s language games, wherein it seems that it extends the invitation to a shared community, only to those animals who can express themselves, leaving those animals that ‘speak in other tongues’ weakened or abandoned. It is left to later animal philosophers, such as Despret (Citation2008), to pick up Hearne’s ideas and extend them to, for example, scientific encounters. Each place of encounter has a distinct ‘we’ that establishes and then converses in other and distinct tongues, and so also different language games, with these other animals outside of Hearne’s training places.

Wolfe continues their critique by turning to what they see as the limits imposed by Hearne’s (and Cavell’s) social contract theory of rights. However, Haraway provides a different reading of Hearne’s bestowing and acquiring of rights, saying of Hearne that ‘in educating her dogs she “enfranchises” a relationship’ (Citation2003, p. 53). It is, in other words, in training where dogs gain rights from their particular humans, and vice versa. The issue becomes one of how humans ‘enter into a rights relationship with an animal’ (p. 53). Where Wolfe is uneasy about a social contract defining animals as property, Haraway’s rejoinder is that Hearne is concerned with contracts providing ‘reciprocity and rights of access’ (p. 54). As the human possesses a dog, so the dog also possesses a human.

Hearne on the expansiveness of a dog and human’s understanding a command

One of Hearne’s strengths is in tracking how a dog, in its responses to commands, only very gradually, in fits and starts, reluctances and acceptances, curiosity and boredom, acquires understanding, makes itself intelligible and takes its place in the discipline of training. As a dog is slowly and sometimes not so surely trained, it is gaining new understandings and new rights, moving towards the point where the dog is not always, nor even most often, the one responding to the trainer. Instead, the tables turn, and it is the dog beginning new conversations, saying new things which it has not been taught to say, and exercising new rights in initiating activities and saying new things (Hearne, Citation2007, p. 75).

In helping us see how much has to be understood in, though indexed by and around, a command, Hearne has us follow her training of a dog called Salty. Salty’s education moves her from the basics of language learning to extending language into different realms. Stage 1 of the training is rehearsals, where ‘sit’ is said to Salty and she is physically positioned in the sitting posture by Hearne. ‘Sit’ here ‘is not what “Sit” will come to mean, but an incomplete rehearsal of it’ (Hearne, Citation2007, p. 54). After several sessions, Hearne stops positioning Salty and moves to use ‘sit’ as a command, where Salty will be corrected if she does not sit. Hearne helps us grasp how much more is yet to come in a language game. She uses the term ‘looped thought’ to mark the early recognition of a word, where it is heard and is witnessably looping into a language game. As the training continues, the landscape of the language game is one where Hearne expands the command into new uses and ‘new moral contexts’ (Hearne, Citation2007, p. 59). The account of training Salty ends with Hearne remarking on the priority of commands over giving names to things and indeed giving names to dogs. To say ‘Salty’ is not to name her but to call her. Hearne’s claim is that the intelligibility of commands entails work with the dog as a member of the discipline of training with rights and duties, including a calling upon the other to fulfil their part as a trainer.

Animal geographies of training

In animal geographies’ and animal studies’ research on classrooms, their members (human and animal) are educated in different practices: obedience, scent, performance, assistance, guiding visually impaired persons, police or gun dog training, sports such as agility or flyball, and even medical detection of disease. As with human education, there are an array of human-animal practices taught in animal classrooms, with shared and divergent teaching practices, architectures, technologies and objects that comprise multiple ecologies of the classroom.

Charles et al. (Citation2021) examine dog training manuals for gundog and companion-dogs, showing how dogs feature as rational and agentive, yet instinctive. They find familiar patterns of gender, class, race and species inequalities in practices of dog training. Like Hearne, they emphasise that dogs choose to learn, and their argument is embedded with shifts from generalising theories of discipline to biopower in animal training cultures (see also Włodarczyck, Citation2018). In a different working relationship, Yarwood (Citation2015) considers the training of rescue dogs, taking us closer to how the movement in the landscape is reflexively tied to the dog’s scenting, where dog and human have distinct and distributed perceptual access. Pemberton (Citation2019, p. 94) similarly documents how trainers must ‘attune themselves to the dog’s distinctive ways of making an acquaintance and their species-specific sensorial, affective and tactile world’. While having affinities with Hearne’s ethics of training, we can note that these are not approaches that acknowledge a dog’s concern with rights to be commanded or to follow commands and these studies place limits on a dog's intelligibility, to others and to themselves.

Of greater relevance in its attention to the ‘missing what of training’ is Smith et al.’s (Citation2021) rich ethnographic description of training police dogs and handlers. Through their description, we come to understand, for example, learning to bite as police-work and, we would add, as the classroom’s task of the trainer, police handler and the dog as trainee. Learning the bite command is taught as a sequence of moves from intercepting, biting, responding and releasing which is comprised of the handler, dog, leash, target, and sleeve. From Smith et al.’s (Citation2021) account, we begin to have a sense of what teaching might involve through their attention to just how trainers twist and turn themselves as a proxy target during bite training, how the trainee responds and how their response is assessed.

Closer still to our ambitions in this paper is Fox et al.’s (Citation2022, p. 6) study of companion dog training where they pursue action as locally situated through ‘the small everyday details and processes of “becoming with” through which humans and canines navigate the training relationship’. They examine failed and successful attempts in a hurdle-jumping exercise. In the first attempt, which through a series of captioned photographs, they provides us with access to its organisation, a dog is jumping enthusiastically at her companion and her companion responds by making her lack of approval and response evident by folding her arms and looking away. In these descriptions of the back and forth between human trainer and dog trainee, we can begin to ground just what instructions, assessments and corrections consist of. Their account provides an understanding of a dog’s response and, in turn, the response of their trainer, and so a sketch of training as itself a kind of conversation. In the dog’s responses, as Hearne would likely point out, the dog has not yet entered properly into the shared language game of agility training. An interpretation which would lead Hearne to urge the trainer to be, in turn, responsive, and thereby to begin earning the right to call upon the dog to jump over a course of hurdles.

Spaces of instruction and training of animals

Ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (EMCA) has investigated the accountable actions that constitute teaching and learning in the classroom and has compiled a substantial collection of studies of educational settings (for a relatively recent review, see Gardner, Citation2019). Of relevance for us, from these classroom studies, is the recurrency and centrality of understanding and failing to understand as described by Macbeth (Citation2011). In common with most classroom studies, Macbeth looks at the uses of the ubiquitous, constitutive and under-appreciated three-part sequence in teaching:

asking a question + answering (or not) that question + assessing the answer.

The task for novices in classrooms is to find, in the instruction from a teacher, an action which they can produce as a relevant response. A response which is then open to inspection and assessment by the teacher. Macbeth, notably, is not concerned with questions of rights, whether those of the teacher to direct students to respond or of students to respond. The problem of whether a teacher is worth following, their sources of authority and where an instruction runs aground when a student expresses their confusion over what they are being asked to do, is touched upon in other studies (Waring, Citation2002).

We will return to education later, but first we need to outline the distinctive perspectives EMCA studies have on language. These studies have, from investigations going back to the 1970s, opened the invitation to conversation and reasoning to non-verbal voices. This invitation stretches across a number of relationships between conversationalists: from Goode’s (Citation1994) inquiries into, and acknowledgement of, the worlds of deaf-blind children; to Sudnow’s (Citation1978) piano experiments with sounded doings; to more recent work on sounding for other’s actions in dance (Keevallik et al., Citation2023), expressing disgust as the other than verbal (Wiggins & Keevallik, Citation2023) and humans’ responsiveness to dogs and parrots by recycling and reshaping their audible calls to us (Harjunpää, Citation2022). These investigations have similarities to the push in animal geographies towards documenting the different sensuous and embodied ways in which we communicate with animals (Ellis, Citation2021). Significantly for us, Mondémé (Citation2023b) has shown how dogs respond to requests with compliance, resistance and plain rejection, as well as how their human companions respond to dogs’ summons. Furthermore, Due (Citation2021), in his study of a visually impaired person and their guide dog, describes the pairing of the verbal command of the guided human and the tactile response from the guide dog, showing how these activities develop in and around asymmetries of access to a challenging walking environment.

It is David Goode’s (Citation2007) study of human-dog play that properly founds EMCA inquiries into non-human animals, inspired in large part by Hearne’s work. He marks out similarities to Hearne’s approach in EMCA’s treatment of intersubjectivity, indexical understanding of singular words, rule-governed sequencing, and ‘the hidden commitments’ of our local language. Where he finds differences from Hearne, through his careful inquiry into playing with his dog, is in the moral elements of his casual untrained play. Through the comparison with play, he remarks on how human-dog relationships inhabit ‘divergent sets of humanly authored orderlinesses, with associated divergent purposes, practices and descriptions’ (Goode, Citation2007, p. 117). What is striking in considering relationships of caring-for, is that when Goode is injured the language game is adjusted by his dog. On realising, and showing she understands his incapacitation, she abandons her usual distant drop of the ball from her retrieve, instead placing the ball right at, and for, his hand so he need not move.

Closer to the problems of understanding rights in training, which we will examine, Mondémé (Citation2012) describes a mistake made by a trainee guide dog while being handed over by its instructor, to a blind handler. The dog is guiding the handler and there is an obstacle in the way. Instead of following its training, which is to walk along the road edge, the dog squeezes through a gap between a wall and the obstacle. The dog’s actions, as failing to follow their training, are made available to all through the instructor’s verbal assessment ‘that wasn’t very clever’ (Mondémé, Citation2012, p. 96). Mondémé notices that the guide dog, on taking the ‘wrong’ route, turns their head back to the trainer and her gesture is understood by the trainer as seeking an assessment of her trajectory. Their wrong-ness, in a Hearnian register, is a question of rights. The three-part sequence, as Macbeth would say, extends its tendrils, with the dog showing their expectation of an assessment of an incorrect path, and, as we would add, doing something which they have no right to do in the job of guiding.

Our study grows out of Jamie’s research on assistance-dogs for physical disability (Arathoon, Citation2022, Citation2023), particularly where they examine how an assistance-dog shows that she has learned to pick up a wallet. Following the IRE sequence, the handler asks their dog to pick up a wallet and praises them when she does. Jamie describes the dog’s skill in using her mouth and paw to position the wallet, to make it available to be picked up. The dog is at a stage in her training where she is understood to have a clear understanding of the command. Her skill is in accomplishing it in this specific, difficult circumstance. The command is an other-than-verbal gestalt, it is a hearable command word which sits within a sequence of gestures.

The human classroom offers a helpful comparison for us to understand how a dog expresses its struggle to respond to a new and unfamiliar instruction. EMCA studies of students struggling to answer questions in classrooms have described the use of ‘I don’t know’ as one way of claiming insufficient knowledge (Sert, Citation2013). Notably, students more routinely respond with silence and/or avoidance of mutual gaze; in short, non-verbal responses (Sert, Citation2013; Waring, Citation2002). Recent classroom studies have foregrounded the centrality of non-verbal embodied actions to instructions (Lindwall et al., Citation2015). In these studies, there is, as Macbeth (Citation2011) underlines, first, a shared understanding of the request and, second, a sense that the lesson coheres in epistemic matters because there is an understanding of what the pupil is being asked to do (e.g. answer a question: see also Lindwall & Lymer, Citation2011). What our investigation in this paper brings to the fore is the struggle to understand what the request itself is requiring: what are you calling upon me to do?

There is another complication in the training of assistance-dogs of which Hearne would be the first to remind us. At stake is: who are we for each other? Star and Jenny, in our opening vignette above, are friends, trainee-handler and carer and cared-for; these three relationships to each other are available to be drawn upon, avoided, maintained or changed in the classroom. What is trying to be built in the classroom, via this language-game around a command like ‘lean’, is the capacity, and the associated set of rights, for Star to assist Jenny, although, with Hearne in mind, we can already imagine future uses of this game for Star in relation to opening doors, not as a response to Jenny but as a request to her. Relatedly, Jamie has described how Star will bring the lead to Jenny, thereby encouraging her cared-for human to go for a walk (Arathoon, Citation2022).

Where we make connections between EMCA’s distinctive approach and Hearne’s ideas is in extending the invitation to language, in recovering intelligibilities of action, sense and grammar, in acknowledging the responsiveness of a wider community of members’ actions towards one another. In this study, we will consequently draw together EMCA’s inquiries into the collective local production of education and training with Hearne’s parallel inquiry into learning commands as inseparable from granting (and withdrawing) rights to give and follow those commands. To do so is to return a different sort of ethical limit on animal education and it is one we investigate through the particular case of assistance-dog training.

Ethnography of a classroom

The data we will share emerges from ethnographic fieldwork at an assistance-dog training class run by the charity Dog A.I.D. This organisation helps physically disabled people to train their own pets to become their assistance-dogs. The journey between a pet’s work and a carer’s work is the Hearnian tasks facing both dog and human. An instructor (an experienced volunteer dog trainer) supervises the class. It contains four assistance-dog handlers and four trainee assistance-dogs. The aim of the class is to help the handlers and trainees in their training while acting as a social network to support handlers and trainees. The empirical material for this paper comes from a longer video recording in which Jenny (as handler) is teaching her dog Star (as trainee) in a classroom with an instructor. Ethical approval was gained from the University of Glasgow.

Video recordings of human-animal places are rich materials for animal geographers (Arathoon, Citation2023; Bear et al., Citation2017; Brown & Dilley, Citation2012; Lorimer, Citation2010; Smith et al., Citation2021) and are well suited to concerns with the particular in ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (Laurier, Citation2014; Llewellyn et al., Citation2022) and behavioural approaches in animal welfare (Wemelsfelder, Citation2007). In animal geographies, video has served in post hoc analysis of embodied, inter-subjective human and non-human animal action (Lorimer, Citation2010). Video displaces the researcher’s post hoc textual reporting of the animal’s action to give priority to examining animal responsiveness in a field of sequential, embodied and visually organised practices. By doing so, practical reasoning and its acknowledgement as, and in, inter-species conversations is there to be witnessed with wonder, not for detail’s sake but as the very whatness of things, their haecceities. It is an inverse view of order as always local and so available for studying locally, common to EMCA and Foucault’s responses to understanding order as filamental rather than of ontologically distinct levels of macro, micro or even meso (Laurier & Philo, Citation2004).

The training example analysed in this paper takes place in a scout hut used as a teaching space, wherein a counter with a half-door is used by the handler and instructor to train dogs in opening doors. This space is part of a family of animal training architectures – the pen, the corral, and the dolphin’s pool. We are interested in the door as it is used in dog training from the perspective of architecture-in-action. Where the retrievable object, a ball perhaps, is central to ‘fetch’, so the door is to ‘lean’. In action, the door provides for opening or closing, gaps that are narrow, wide or just right, and for slow, or fast, opening and closing. As it is for almost all domesticated animals, the door is established as a device used by friends and trainers to stop an animal’s progress, to close them away from other spaces, to make offers and so on. It is a device which a dog like Star can scratch at, point at, linger beside or bark from behind. In the lesson that we will examine, the door raises questions: which side is Jenny on? is it open? is it open for me to see through? or to pass through? It is itself part of establishing a pedagogical participation framework with the instructor positioned away from the door, well-placed to monitor the training of Star and, from what she witnesses, to teach the handler how better to train her trainee.

Following the policies of EMCA studies of education and classrooms, our ambition is not to correct or assess the teachers via, for instance, their correct or incorrect application of training techniques. Nor is our intention to critique forms of dog training philosophy, these can be found in Pręgowski (Citation2015) and Włodarczyck (Citation2018). Instead, it lies in describing ethnomethodologically the work of instruction of trainee and trainer. They are becoming competent and intelligible as a classroom task that necessarily, in its local production, seeks to establish and use the very structures and language games being taught and learned (Lindwall et al., Citation2015, p. 142).

Understanding the work will require recovering its identifying details and this recovery risks our analyses being misunderstood as ‘micro’. To picture it that way would be to picture Wittgenstein as a philosopher of micro-reason, micro-scepticism or indeed micro-philosophy, rather than one whose investigation learns from and provides a clearer account from a particular case (Moi, Citation2015). Examining a particular case is, indeed, one of the central ways in which EMCA re-specifies theoretical problems by returning them to ordinary practices (Lynch, Citation1992). To name our form of inquiry ‘micro’ reveals more about the persistence and resilience of a macro-micro scalar binary in animal geographies and elsewhere in the social sciences, than it reveals of our approach and of what we it can teach us about our understanding of understanding.

Leaning on an open door

In Hearne’s description of the long journey of training, the episode that we will examine is early in one sense and late in another. It is early because ‘lean’ has only recently been introduced as a new command. The shared assumptions of Jenny and the instructor are that Star does not and could not yet understand ‘lean’. It is a command that is to be taught, for now, through using a door, where a door is itself already part of a language game between Star and Jenny. It is late because Star and Jenny already have an established friendship, with its familiarised ways of calling upon one another, having reached what Hearne (Citation2007, p. 54) describes as ‘shared commitments and collaboration’. In Hearne’s recounting of training, it is the very training itself that makes ‘mutual autonomy possible’ (p. 54) so here autonomy is itself one of the things at stake.

The two-stage introductory practice for the handler is, in stage one, to say ‘lean’ while tapping their own thighs as a summons and providing a positive assessment of the dog when they stand up to lean on their thighs (Hearne, Citation2007; Mondémé, Citation2020, Citation2023b). In stage two, the handler is to say ‘lean’ while tapping on the door, encouraging the dog to understand that ‘lean’ involves finding where the lean is to be located. In stage one, to paraphrase Hearne, this is not what ‘lean’ will come to mean, just the rehearsal of it. In stage two, Star is to find a projection of ‘lean’ into a different place. ‘Lean’ has to be transformed to leaning on a door, a movement from Jenny’s warm body to a known-in-common, yet fraught, architectural device. A preliminary understanding of ‘lean’ as a body-position is not a simple matter given that, unlike ‘sit’, ‘lean’ is not known that way. It will become all the more challenging because the shift of location is the difference between ‘sit’ on the floor to being instructed to ‘sit’ on an immaculate white sofa.

In our first extract, after Jenny has made a series of attempts to move to stage two by tapping the door rather than her legs. Star had yelped loudly as an early expression of her struggle to understand. Hearing the yelp, the instructor walks over from another part of the classroom to help Jenny and Star. In this three-party pedagogical participation framework, the instructor is instructing the handler in how to instruct the trainee dog. While different from Hearne’s dyad of trainer and trainee, the participation is similar to the three-party frameworks of guide, police or companion training (Fox et al., Citation2022; Mondémé, Citation2023b; Smith et al., Citation2021). In our case, Jenny is not Hearne’s expert trainer, rather she is, in turn, being instructed by an expert in how to command a dog (as we were when we read Hearne’s work). It is a form of training where the handler and their dog are learning to inhabit the language game of ‘lean’. The yelp, as a cry of frustration that expects help in an interspecies language game, is witnessably understood this way through the response of the instructor in walking across to help Star and Jenny.

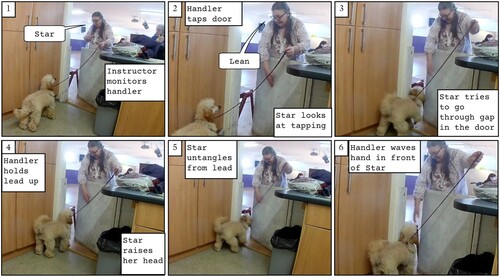

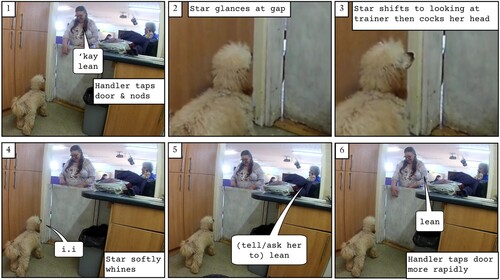

A first suggestion made by the instructor is that Jenny should move from standing beside the door to standing behind it. Her suggestion is one that will begin to reveal if Star understands the lean command as a body position, while also transferring ‘lean’ on to the door. For Star to lean on Jenny’s legs again and get a cuddle, she will have to lean on the door first. We can start to follow what occurs in our graphic transcript (), containing a sequence of numbered ‘panels’.

The instruction sequence is initiated by calling the dog’s name (panel 1). Jenny then taps on the door while saying the word ‘lean’ (panel 2). If we look at Star on being called, she is witnessably ready and involved, her name being a summons to the task of learning. She is standing oriented towards the door, not just to the door but to the side that opens. When Jenny taps the door with her hand (panel 2), Star watches Jenny’s hand. Star’s response to the tapping and ‘lean’ is to walk towards the gap in the door (panel 3). Her response, as a response to just that action, expresses her understanding of the meaning of the instruction: ‘lean’ is hence seemingly a summons to join Jenny. It is not hard for us to understand Star’s misunderstanding: a door, with a gap opened, is being tapped by her handler, accompanied by an as yet uncertain new command, giving all the appearances of a summons to pass through a doorway.

In an attempt to redirect Star’s attention to the door’s surface rather than its gap, Jenny uses the lead to lift her head towards it (panel 4). Star’s response is to untangle herself (panel 5), which is, after all, a relevant response, because lifting a lead is a way of asking a dog to help in the untangling. The sequence ends with Jenny trying a third gesture – waving her hand in the gap, which Star does watch, presumably as we would, wondering about what sort of response should be made to it (panel 6). We ought to appreciate in Star’s responses her candidate understandings of the initiating actions from Jenny. Given the purpose of the command ‘lean’ is to open doors, the set-up of the door, as already open, itself obscures or distracts from what the action is to accomplish. At this early stage, the instructor's and Jenny’s ambition is to have Star assume the lean position rather than make use of it to open doors.

Given the now apparent problem of Star’s response to the open door, Jenny then accounts for why the door is open. While she does this, she demonstrates it by pushing against the stiff door. We can note that Star is again monitoring the door and its gap and is responsive to its movement, as can be seen in . Jenny’s account has, built into it, a recognition of the open door as the source of the misunderstanding from Star, and the ‘if I shut it’ (panels 7 and 8) marks her awareness of Star finding it too difficult to open. When the instructor closes the door, Star retreats and thereby places herself back into a start position for the lesson (panel 10). Meanwhile, she is witnessably paying attention to one and then the other (panels 8, 9 and 10), although, for their part, the two trainers are engaged with one another over solving the stiff door problem. Star’s looks are themselves inquiring looks, raising a question around the open door and the summons. Hearne asks us to be attentive to puzzlement by dogs, and Hearne deliberately will act puzzlingly during training for her trainees as a trainer’s method to draw animals into ‘trying to work out the implications of my behaviour’ (Hearne, Citation2007, p. 52).

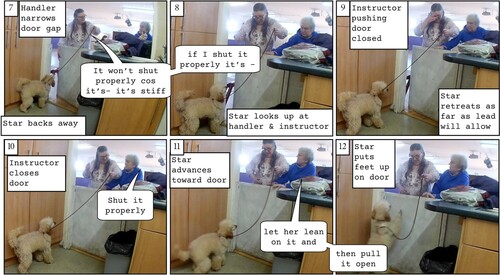

In response to the instructor closing the door, Star steps not just one step backward but several (panel 9). She is making clear that she understands this course of action to be ended. It is seemingly obvious, yet, in her re-set, she shows her knowledge, recognition and production of the structures of training as commands and responses (Macbeth, Citation2011). One of dog training’s abiding and projectable qualities is its repeated body-movement sequences that makes dog training less like the classroom and something closer to the repetitions of sports coaching or dance instruction (Broth & Keevallik, Citation2014). Moreover, Star expresses, in her attentiveness, a readiness for whatever request is to be made next, a readiness despite her earlier responses not having received a positive assessment. Star changes the learning sequence now: she initiates the next-time-through by advancing towards the door (panels 11 and 12) and then leaning on it with Jenny watching. For this next time in the lesson, Star has successfully leaned on the door and opened it without a tapping gesture or ‘lean’ command from Jenny, as shown in (panel 13).

Star’s door-opening is enthusiastically assessed (panels 14–17: see also Mondémé, Citation2020). It is, in instructional terms, not a clear display of understanding given the absence of ‘lean’ as instruction. Nonetheless, were her opening not to be praised, it would raise the problem of not recognising a correct response and so further confusing the trainee. Star cannot be said to have fulfilled the criteria for having learnt ‘lean’, but has learned a little more through what is not so far from (and might just be) an educated guess. She has found that there was something, as yet to be fully fathomed, which she has just done which was correct and pleasing to her trainer. Indeed, on having opened the door, Star checks with her trainer and instructor, by lifting her head, on what their response will be to her having opened the door. In all of this, she is continuing her inquiry into: what is the training thing that I am being asked to do? It would not be unreasonable, and it is not so far from the lesson’s project, that opening a door is a praise-able part of it. The praise is underlined with a reward to nibble on (panel 16). In reflecting on praise, Hearne differentiates trying to please trainers from ‘the awe that consists in honouring the details’ (Hearne, Citation2007, p. 70). Star is not yet far enough into the lean language game to have even a mouthful of its details, but here she has found something of it even if she cannot yet be said to know what it is.

In their successful redoing of the instructed sequence from the handler, the trainee shows what are the beginnings of an understanding of it (Hearne, Citation2007; Lindwall et al., Citation2015; Macbeth, Citation2011). Star’s opening of the door is positively assessed in dog-relevant terms ‘good girl’ (panels 15–17: see also Mondémé, Citation2020). The instructor is responsive to Star’s guess, and she suggests reversing the order and saying ‘lean’ after Star leans on the door, as shown in (panel 19). With the door closed again, the hander tries the ‘lean’ command (panels 21–22). This repeat is one that has been reshaped through the changed initial state of the door. Simultaneously, Jenny has adjusted the instructional sequence to begin with tapping. There is a short delay after the tapping before Star rises up, in a slowed, tentative way, to put her paws on the door. On this try, it is only when Star assumes the lean position that Jenny then says ‘lean’ (panel 22). As stiff as Jenny had warned it would be, the door only opens a crack, and so, as suggested by the trainer, Jenny helps Star by opening the door further (panel 23).

These, then, are the increments in which training progresses. Notably, Star has relinquished the lean position immediately, since it is as much a small shove as a lean that uses force and duration to open a door. Let us highlight two further aspects here: first, with the use of ‘lean’ in a distinct way, this time by Jenny saying ‘lean’ at the very moment that Star assumes it, we have the building of Hearne’s ‘looped thought’. This position is part of the landscape of this command. On this attempt, it does not precede it as a command, for it is the tapping instead that is understood by Star as a request to touch that part of the door. The second aspect is Star’s witnessable cautiousness, in its slowed pace, lifting herself up, to touch the door. As we remarked at the outset, doors are objects to be treated with caution by dogs. As significant shared objects for both human and dog, dogs are likely to be corrected for touching them under the wrong circumstances and especially for opening them when they do not have the rights to do so.

Adjusting the sequence attends to how Star could misunderstand what ‘lean’ is in a request and response pairing. As a sequential matter when teaching the command, the tapping action is done first and then the word is said. The tap makes relevant the correct surface for leaning on. As Crist and Lynch (Citation1990, p. 12) describe it, commands ‘are not merely static labels for particular actions. Teaching the dog to sit in response to the command “sit” is partly teaching the dog to obey, but it is also teaching the dog linked action’. As we described at the outset, Hearne (Citation2007, p. 59) takes linked action further into domains of trust, rights and judgement where a ‘great variety of projections of “Sit” are going to be required, and these are by and large projections into new moral contexts’. Training is the map of a new ethics of opening doors as help, as changes in what we are going to do next, as invitations and, as Hearne (Citation2007) reminds us, of opportunities for judgments of excellence and dishonesty.

There is more to note in the instructor’s suggestion to shift the saying of ‘lean’ to the later part of the instruction sequence. The door opens after the word ‘lean’ has been uttered. Should it not have opened, ‘lean’ can be repeated until the door does open, and Star would be learning that ‘lean’ involves sustaining a position like ‘sit’ or ‘stand’. Teaching a police dog how to bite has a durational aspect, but the biting is not towards biting off the detainee’s arm as its successful conclusion. Indeed, its error would be in drawing blood, and its proper ending is accomplished through the ‘release’ command (Smith et al., Citation2021). Similarly, Star has to learn that ‘lean’ is a continuing action alongside what directs, allows or counts for it to be finished.

The further instruction from the instructor to bring Star through ‘because she wants to come to you’ (panel 24) could be based on the instructor’s authority as an expert in dogs, and consequently, she is entitled to say what Star wants over and above Jenny’s intimate knowledge of Star. It might equally be locally occasioned by Star’s previous attempts to get through the door to reach Jenny. Whatever it is, the instructor extends the sequence of actions that are placed in a grammar for Star. Opening the door is followed by, and is for the purposes of, getting through the door. Equally, it deals with satisfying Star’s desire for embodied praise through petting and, for the lesson, of closing the instructional sequence (Macbeth, Citation2011; Mondémé, Citation2020).

Problems of misunderstanding as problems of rights

One successful pairing of command and response, with an assessment of it as correct, does not affirm for any of the parties that an understanding of a command has been reached. As classroom studies have demonstrated many times over, students’ mistakes, in their details, provide a rich seam for the teacher to develop their students’ understanding of the rule or idea that is the topic of the lesson (Gardner, Citation2019; Macbeth, Citation2004). There are occasions where the student continually fails to grasp what they are being instructed to do, which ought then to be instructive for both pupil and teacher. After the early success of Star opening the door, Jenny is left questioning – across the next series of repetitions of the training – not the failures of Star’s attempts, eagerness to learn and so on, but rather her own teaching. Across the next attempts, we will examine Star not opening the door as the witnessable and publicly available confusion of a trainee unable to learn what the teacher is trying to teach (Macbeth, Citation2011), a confusion that turns on an early puzzle for the dog, as Hearne (Citation2007) alerts us, of the rights to act in an, as yet, not fully comprehended way on the morally weighted site of the door.

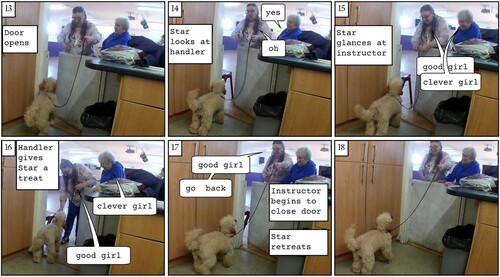

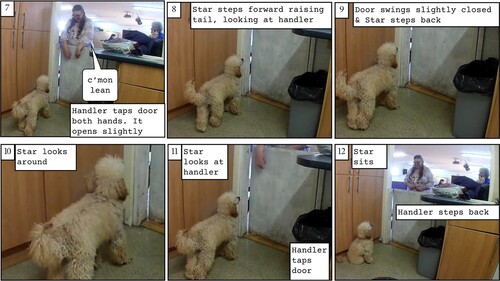

After congratulating Star with a hug for her two previous correct responses, Jenny places herself behind the door. Jenny taps and says ‘kay lean’ quietly and then repeats it a little more loudly, as can be seen in (panel 1). Jenny is repeating the successful command gestalt: standing behind the door, tapping the door and saying ‘lean’. It is clearer now to Jenny and to us, in Star’s whine, that she is not sure of what she is being commanded to do. As we noted above, the previous correct response was provided without the response yet being grounds for claiming and relying upon Star understanding ‘lean’. Star repeating the correct response consistently would begin to be the basis for her having understood the dog-word (see Hearne, Citation2007, p. 55).

In panel 4, Star cannot produce words but she can produce ‘sounded-doings’, a term used by David Sudnow (Citation1978) to widen the intelligibility of action beyond the verbal. Star’s whines are produced as organisational things, hearable by her listeners as ‘instructably observable’ (Garfinkel, Citation2002, p. 185). They are hearable for what they are, as struggles to understand, in the structuring of this classroom lesson, as a teacher could witness their pupil sighing and rubbing their temples, or in a different local setting the vet treating a dog, where whimpering is hearable as discomfort (MacMartin et al., Citation2014).

If we examine yet more carefully what Star is doing after ‘kay lean’ in panel 1, we can appreciate the witnessability of her query around the door and the command. The centrality of practices of looking and gazing to inter-species interaction has been examined by Mondémé (Citation2023a) in relation to showing availability, summoning someone, eliciting praise and indeed expanding praise. Here Star’s gaze shift is picking out the feature of the door which she is puzzling over: the slight gap, and then looking to check Jenny is looking, before then cocking her head and thereby posing the gap as the questionable thing (panels 2–3). It is from her querying look that Star then adds her whine (panel 4). The whimper initiates further instruction from the instructor to Jenny (panel 5). The instructor hears the struggle to understand, but this time does not appear to notice that the door is open again and hears the whine instead as marking the absence of further instructions from Jenny.

Jenny repeats ‘lean’ (panel 6) while also altering her tapping and speaking to a faster pace. In her fourth repetition of the command she changes it again, prefacing it with ‘c’mon’ and tapping with both hands and leaning in, as in , panel 7. Inadvertently, Jenny’s two-handed tapping opens the door a little further (panel 7). Star immediately steps forward showing her grasp of it as a part of a summons which is letting her through to Jenny (panel 8). In all the things that ‘lean’ might yet be used for, Star shows a candidate understanding of ‘lean’ as a form of summons to the trainer. She is also leaving the right to open, close and even, merely, touch the doors as Jenny’s, not hers. The tapping accidentally produces Jenny as the one who is opening (and then narrowing) the door gap. By what right in the midst of a lesson would a well-trained dog respond to a door, seemingly controlled by her trainer, by opening it?

Jenny repeats her instruction as talk accompanied by tapping on the door and, in doing so, once again widens the gap in front of Star (panel 7). Star shows her understanding of the widening and narrowing of the gap in altering her stance – moving forward (panel 8) – when it seems, once again, to be a projected offer from her handler for her to pass through the gap. She shows her readiness in raising her tail and establishing a mutual gaze with Jenny (also panel 8).

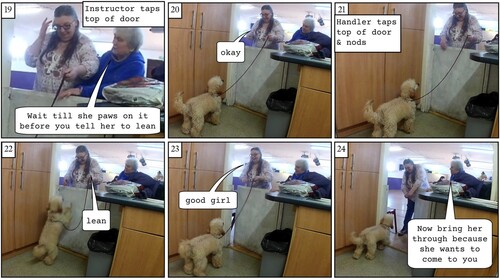

Once again the stiff door swings back slightly and Star retreats a step (panel 9). Her struggle to understand is expressed in her looking downward at the wall, then the door and then up to Jenny’s face again (panels 10–11). When she sits (panel 12), she maintains a mutual gaze with Jenny. There is no disengagement from the larger lesson, just a ‘giving up’ on what we are trying to do together here, right now. There is a show of not knowing how to go on, what the right response could be. Jenny herself shows her recognition of an impasse in stepping back from the door. Beyond the transcript, the instructor encouraged Jenny to continue, Jenny did then repeat the ‘lean’ command while Star remained sitting. She remained sitting through several more repetitions until eventually Jenny opened the door and had a cuddle with her.

Why might it be that the door raises such a puzzle for Star? It is because, as we noted earlier, it poses a problem of her rights to act. Doors are the devices that handlers have the right to operate, although, of course, many dogs (recorded and enjoyed in many social media videos) have startling capacities to open all manner of doors when their human companions are not around. Even Mondémé’s (Citation2023a) guide dogs, with their greater rights to act, are trained only to point at door handles, not open them. When fully closed and not being moved by handler or instructor, it becomes something that is not part of the action of offering or denying passage (e.g. like a barrier in a home to stop a dog getting into a certain room: Power, Citation2008). The problem, which Hearne places at the centre of commanding, is not just what am ‘I’ being asked to do but what have ‘I’ the right to do. Hearne leaves us to identify occasions when new rights are being bestowed, which is what we have begun to reveal here in the trouble of teaching the lean command.

Conclusion: the threat of confusion/the uses of confusion/rights to stop the lesson

[T]o teach a being to speak presupposes not only a tolerance of but also a profound interest in misunderstandings. (Despret, Citation2008, p. 125)

At the heart of our paper is the teaching encounter, where the task is to learn a new command for both the trainee and the handler. It raises not just problems of understanding but their intertwining with rights to do certain actions in response. We would say, learning from Star’s struggles, that the door raises the problem of rights of passage. For Star, training will give her a new right to open doors for Jenny as part of her caring work and, as Hearne (Citation2007) made clear, this right requires judgements by Star around just when and for whom she can open doors. In institutionally assisting, she acquires new commands and new rights as a carer where ultimately, as Hearne emphasised, ‘lean’ will be not only a two-way conversation, it will be one where Star uses her leaning position to say new and unexpected things. Yet, at this early stage of learning, part of the puzzle that we can appreciate Star facing is more than a matter of comprehension, it is one of responding to a command that involves an action which one does or does not have the right to do. As a pupil, she not only expresses her struggle to understand, she calls a halt to the instruction sequence.

From Hearne’s passionate reflections on training, we gather insights into the granting, maintaining and transforming of the rights of dogs and humans. As we have argued earlier, Hearne takes a distinct perspective from early ideas of animal rights on the bestowing (and removing) of rights through the particular case of training. It is an obvious remark to make, yet one we should still state, that dog training comes with hierarchies of the commander and the commanded, emerging from longer projects of domestication upon which Hearne herself comments. In helping us develop our understanding of our close relationships with certain animals Hearne asks us to ‘wonder at the priority of commands’ (Hearne, Citation2007, p. 25) and to realise that in doing so there is a handing over of authority to her dog to say ‘something I haven’t taught her to say’. Her turn is away from the sheer presence of commands and commanding in the world as evidence of human power over animals and towards the ethics of ‘reverence, humility and obedience’ from those commanding and those following, where those who command are able to command only whom they follow. Authority is required but it is not a good in itself, and instead, her work unflinchingly examines ‘the taint in our authority’ (Hearne, Citation2007, p. xvi). The limit of animal geographies, to which we have returned through both Hearne and thinking with a training class, is animal geographies’ willingness to acknowledge animals. When we, as students of animal geographies move close to recount an encounter, we depart all too quickly from what animals are saying, from particular conversations with particular animals that bestow or deny rights and which acknowledge the judgements of non-human animals.

Turning to EMCA studies of classrooms, teaching and animals, we hope to have shown through our study how animal geographies can stay with the troubling availability of intersubjective practices (and not spend too long worrying over whether video is a better form of recording, registering and attending to the lives of non-human animals). EMCA has itself become increasingly interested in the gestural, non-verbal and embodied aspects of conversations, what it broadly refers to, in response to theories of talk from linguistics, as multi-modal interaction (Mondada, Citation2019). Our ambition, for both classroom studies and animal training studies, is to foreground the problems of rights, where in this study it is rights to respond to instructions from a teacher or trainer. In Smith et al.’s (Citation2021) study of police dog training, while they examine how biting is taught, they do not consider the bestowing of the right to bite on command as a similar puzzle, we imagine, for the dog that begins with learning that it does not have the right to bite humans. For Hearne, reflecting on untrained biting, she considers how it is interwoven with judging character. Yet that is, itself, a different use of a bite, namely to warn-off or reject an unwanted advance from a stranger. Our case lacks the moral sharpness of biting, where a dog can be killed by institutions for doing so, yet door opening is a challenging task for which a dog is being asked to take responsibility.

What we have described is an episode in a dog’s education: learning a task for the institutional work that is becoming the care assistant of their friend. It leaves us revisiting a brief comment by Hearne (Citation2007, p. 71) on a dog being taught to retrieve: ‘Salty doesn’t (can’t) retrieve for me, she can only retrieve with me. This is a mentor relationship.’ Salty had to care about retrieving to be successful at it, just as for Star opening doors is for Jenny more than with Jenny. It is a caring-for relationship where an assistance-dog provides care for their human handler and handler provides care for their assistance-dog through the developing of rights.

Acknowledgements

Liz Peele, Liz Stokoe and Chloé Mondémé for early data sessions. SEDIT members for their noticings. Our anonymous reviewers and Chris Philo for refining and reshaping this manuscript and its analyses. The authors confirm that there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arathoon, J. (2022). The geographies of care and training in the development of assistance dog partnerships [Unpublished PhD thesis]. University of Glasgow. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/82798/

- Arathoon, J. (2023). Using ethnomethodology as an approach to explore human–animal interaction. Area, 55(3), 390–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12865

- Bear, C., Wilkinson, K., & Holloway, L. (2017). Visualizing human-animal-technology relations: Field notes, still photography, and digital video on the robotic dairy farm. Society & Animals, 25(3), 225–256. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341405

- Broth, M., & Keevallik, L. (2014). Getting ready to move as a couple: Accomplishing mobile formations in a dance class. Space and Culture, 17(2), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331213508483

- Brown, K., & Dilley, R. (2012). Ways of knowing for ‘response-ability’ in more-than-human encounters: The role of anticipatory knowledges in outdoor access with dogs. Area, 44(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2011.01059.x

- Cavell, S. (1999). The claim of reason: Wittgenstein, skepticism, morality, and tragedy. Oxford University Press.

- Charles, N., Fox, R., Smith, H., & Miele, M. (2021). ‘Fulfilling your dog's potential’: Changing dimensions of power in dog training cultures in the UK. Animal Studies Journal, 10(2), 169–200. https://doi.org/10.14453/asj.v10i2.8

- Crist, E., & Lynch, M. (1990). The analyzability of human-animal interaction: The case of dog training. International Sociological Association Conference, Madrid, Spain, July 1990 (copies available from the authors). Available in French as: Lynch, M., & Crist, E. (2022). L’analysabilité de l’interaction entre humains et animaux : le cas de l’éducation canine. Langage et société, N° 176(2), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.3917/ls.176.0027.

- Despret, V. (2008). The becomings of subjectivity in animal worlds. Subjectivity, 23(1), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2008.15

- Due, B. L. (2021). Interspecies intercorporeality and mediated haptic sociality: Distributing perception with a guide dog. Visual Studies, 38(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2021.1951620

- Ellis, R. (2021). Sensuous and spatial multispecies ethnography as a vehicle to the re-enchantment of everyday life: A case study of knowing bees. In A. Hovorka, S. McCubbin, & L. Van Patter (Eds.), A Research Agenda for Animal Geographies (pp. 87–100). Edward Elgar.

- Fox, R., Charles, N., Smith, H., & Miele, M. (2022). ‘Imagine you are a dog’: Embodied learning in multispecies research. Cultural Geographies, 30(3), 429–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/14744740221102907

- Fraser, M. M. (2019). Dog words – or, How to think without language. The Sociological Review, 67(2), 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026119830911

- Gardner, R. (2019). Classroom interaction research: The state of the art. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 52(3), 212–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2019.1631037

- Garfinkel, H. (2002). Ethnomethodology's program: Working out Durkheim's aphorism. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Goode, D. A. (1994). A world without words: The social construction of children born deaf and blind. Temple University Press.

- Goode, D. (2007). Playing with my dog Katie. Purdue University Press.

- Haraway, D. J. (2003). The companion species manifesto: Dogs, people, and significant otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press.

- Harjunpää, K. (2022). Repetition and prosodic matching in responding to pets’ vocalizations. Language & Société, 176(2), 69–102. https://doi.org/10.3917/ls.176.0071

- Hearne, V. (2007). Adam's task: Calling animals by name. Skyhorse.

- Keevallik, L., Hofstetter, E., Weatherall, A., & Wiggins, S. (2023). Sounding others’ sensations in interaction. Discourse Processes, 60(1), 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2023.2165027

- Laurier, E. (2014). Noticing. In R. Lee, N. Castree, R. Kitchin, V. Lawson, A. Paasi, C. Philo, S. Radcliffe, S. M. Roberts, & C. W. J. Withers (Eds.), Handbook of human geography (pp. 250–272). Sage.

- Laurier, E., & Bodden, S. (2020). Ethnomethodology/ethnomethodological geography. In A. Kobayashi (Ed.), International encyclopedia of human geography (2nd ed., pp. 329–334). Elsevier.

- Laurier, E., & Philo, C. (2004). Ethnoarchaeology and undefined investigations. Environment and Planning A, 36(3), 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3659

- Lindwall, O., & Lymer, G. (2011). Uses of “understand” in science education. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(2), 452–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.08.021

- Lindwall, O., & Lymer, G. (2024). Detail, granularity, and Laic analysis in instructional demonstrations. In M. Lynch & O. Lindwall (Eds.), Instructed and instructive actions. The situated production, reproduction, and subversion of social order (pp. 37–54). Routledge.

- Lindwall, O, Lymer, G, & Greiffenhagen, C. (2015). The sequential analysis of instruction. In N. Markee (Ed.), The handbook of classroom discourse and interaction (pp. 142–157). Wiley.

- Llewellyn, N., Hindmarsh, J., & Burrow, R. (2022). Coalitions of touch: Balancing restraint and haptic soothing in the veterinary clinic. Sociology of Health & Illness, 44(4-5), 725–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13458

- Lorimer, J. (2010). Moving image methodologies for more-than-human geographies. Cultural Geographies, 17(2), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474010363853

- Lynch, M. (1992). Scientific Practice and Ordinary Action. Cambridge University Press.

- Macbeth, D. (2004). The relevance of repair for classroom correction. Language in Society, 33(05), 703–736. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404504045038

- Macbeth, D. (2011). Understanding understanding as an instructional matter. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(2), 438–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.12.006

- MacMartin, C., Coe, J. B., & Adams, C. L. (2014). Treating distressed animals as participants: I know responses in veterinarians’ pet-directed talk. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47(2), 151–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2014.900219

- Moi, T. (2015). Thinking through examples: What ordinary language philosophy can do for feminist theory. New Literary History, 46(2), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2015.0014

- Mondada, L. (2019). Contemporary issues in conversation analysis: Embodiment and materiality, multimodality and multisensoriality in social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 145, 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.01.016

- Mondémé, C. (2012). Animal as subject matter for social sciences: When linguistics addresses the issue of a dog’s “speakership”. In P. Gibas, K. Pauknerová, & M. Stella (Eds.), Non-humans in social science: Animals, spaces, things (pp. 87–105). Pavel Mervart.

- Mondémé, C. (2020). Touching and petting: Exploring “haptic sociality” in interspecies interaction. In A. Cekaite & L. Mondada (Eds.), Touch in Social Interaction (pp. 171–196). Routledge.

- Mondémé, C. (2022). Why study turn-taking sequences in interspecies interactions? Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 52(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12295

- Mondémé, C. (2023a). Sequence organization in human–animal interaction. An exploration of two canonical sequences. Journal of Pragmatics, 214, 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2023.06.006

- Mondémé, C. (2023b). Gaze in interspecies human-pet interaction: Some exploratory analyses. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 56(4), 291–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2023.2272527

- Pemberton, N. (2019). Cocreating guide dog partnerships: Dog training and interdependence in 1930s America. Medical Humanities, 45(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2018-011626

- Power, E. (2008). Furry families: Making a human–dog family through home. Social & Cultural Geography, 9(5), 535–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360802217790

- Pręgowski, M. P. (2015). Your dog is your teacher: Contemporary dog training beyond radical behaviorism. Society & Animals, 23(6), 525–543. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341383

- Sert, O. (2013). ‘Epistemic status check’ as an interactional phenomenon in instructed learning settings. Journal of Pragmatics, 45(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.10.005

- Smith, H., Miele, M., Charles, N., & Fox, R. (2021). Becoming with a police dog: Training technologies for bonding. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 46(2), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12429

- Sudnow, D. (1978). Ways of the hand: The organization of improvised conduct. Harvard University Press.

- Waring, H. Z. (2002). Expressing noncomprehension in a US graduate seminar. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(12), 1711–1731. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00047-4

- Wemelsfelder, F. (2007). How animals communicate quality of life: The qualitative assessment of behaviour. Animal welfare, 16(S1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962728600031699

- Wiggins, S., & Keevallik, L. (2023). Transformations of disgust in interaction: The intertwinement of face, sound, and the body. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v6i2.134841

- Włodarczyck, J. (2018). Genealogy of obedience: Reading North American dog training literature, 1850s–2000s. Brill Books.

- Wolfe, C. (2003). Zoontologies: The question of the animal. University of Minnesota Press.

- Yarwood, R. (2015). Lost and hound: The more-than-human networks of rural policing. Journal of Rural Studies, 39, 278–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.11.005