ABSTRACT

Writing is central to PhD work, though often a source of challenge, given the dissertation is the basis for the award of the degree. Universities may offer writing workshops, but these frequently take a remedial, skills-based approach: writing as something to fix rather than a developmental life-learning process of gaining confidence and fluency as a writer. In this study, we report the design of an eight-month writing program premised on a developmental approach and the longitudinal assessment of participants’ journeys. Participants incorporated many elements of the developmental approach, including goal setting and review, metacognitive talk about their writing, valuing others’ perspectives, and viewing writing challenges as shared. Most, but not all, developed a broader understanding of learning to write as an exploratory learning process. Finally, the data collection and analysis structure proved productive, not just for the inquiry, but also formatively during the program – both for the participants and facilitators.

Introduction

Writing is central to PhD work though often experienced as a source of challenge and anxiety, given the dissertation (a substantial piece of writing) is the basis for the award of the degree (Cotterall, Citation2011). While some universities offer PhD researchers workshops, these often take a functional, instrumental skill set view of writing, as something to fix rather than as developmental: an iterative, exploratory life-long learning process of developing confidence and fluency as a writer (Barnacle & Dall’alba, Citation2014; Tardy et al., Citation2020). Cotterall (Citation2011) amongst others has called for stronger developmental pedagogies for doctoral writers, ones that frame their structure around a positive-growth model rather than a remedial one. In this study, we reportFootnote1 the design of an eight-month writing program premised on a developmental stance and the longitudinal assessment of participants’ journeys (pre, during and end of program).

Context

Writing traditions vary across disciplinary clusters (Cuthbert et al., Citation2009), for instance, in the humanities and social sciences, individuals often have more solitary/single authored experiences than in the sciences where papers are generally co/multi-authored. Still, broadly speaking, academic literacy from a developmental perspective comprises a) making sense of disciplinary ‘talk’ – that is, viewing reading (Haas, Citation1994) as a precursor to b) thinking critically and communicating effectively in the chosen field (Florence & Yore, Citation2004). From this perspective, developing academic writing literacy involves individuals setting goals regarding acquiring greater fluency, more metacognitive knowledge (a discourse about writing), and more persuasive skills in response to expanding expectations and more complex writing tasks (Beaufort, Citation2000). This process involves developing confidence as ‘a writer’ (Kamler & Thomson, Citation2008; Lea & Stierer, Citation2009) – thus, emotional investment (Aitchison et al., Citation2012) to situate oneself legitimately in relation to a reader/scholarly community (see Ivanic & Camps, Citation2001).

In other words, writing development is a personal, lifelong exploratory practice (Richardson & St Pierre, Citation2005) undertaken by scholars regardless of expertise (Kamler & Thomson, Citation2008); it benefits from interaction with peers (Aitchison, Citation2009) such as writing groups where members meet to exchange comments on previously circulated drafts (Aitchison & Lee, Citation2007). In Aitchison and Lee’s view, writing groups enable participants to experience and ultimately value how writing requires engaging with a community of readers (those in the group, in the first instance, but also unknown readers of something published). Such groups can also help junior researchers’ capacity for a) giving and receiving feedback (Caffarella & Barnett, Citation2000), b) critiquing their own writing, and c) gaining confidence as writers (Tardy et al., Citation2020).

Given the complexity of writing development, programs for PhD researchers need to move beyond the remedial, skills-based, toolkit model to a developmental one – and few examples exist (Badenhorst et al., Citation2012). The curricular challenge in designing a program around this approach is fourfold. Many participants may a) hold a functional, instrumental view of themselves as writers so seek ‘fixes’; b) be unfamiliar with setting and working towards personally invested writing goals so are undirected in their writing efforts; c) lack a metacognitive discourse to talk about/assess writing; and d) view writing as a solitary activity, not as a potential conversation with others.

Our program, designed to enact a developmental, process-focused stance, encouraged participants over time to:

Define their own writing goals and review them and related emotions as they progressed (Richardson & St. Pierre, 2005)

Establish a writing community to draw upon in order to enhance writing practices (confidence and criticality) (Aitchison & Lee, Citation2007) and to develop a shared discourse and new tools and strategies (Beaufort, Citation2000).

Take into account in their writing the intertextual (reading) as well as interpersonal nature of scholarly communication (Ivanic & Camps, Citation2001)

The longitudinal iterative design is one possible answer to Cotterall’s (Citation2011) call: Where’s the pedagogy?

Research questions

We asked the following broad question: What were the views of relatively competent writers as to their own writing development in relation to the program experience? We focused on this group since we were particularly interested in learning the extent to which our developmental approach could provide learning opportunities for relatively competent writers (as proposed by Kamler & Thomson, Citation2008).

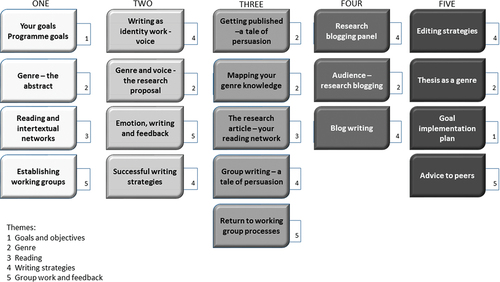

Designing the program

The non-credit program we designed and co-facilitated focused on helping participants reach goals they set themselves. The program stretched over eight months (April-November). Participants met nine times (roughly every 3–4 weeks) in both: a) five five-hour plenaries where we facilitated group work and discussion around elements of scholarly communication; and b) four meetings of small working groups between each plenary where groups of participants (3–4) discussed the work emerging from the plenaries and provided each other feedback on their writing. In other words, we, as co-facilitators did not provide feedback on specific pieces of their writing, but rather offered tools (strategies, and a discourse) to enable participants to think meta-cognitively about their writing – no matter what the specific genre was. Below, we describe the program goals and rationales and how we designed the two types of meeting to facilitate the goals.

Program goals

There were five learning goals.

G. 1: Improve as regards your own targeted goals

To encourage participants to take ownership of their development in relation to their own goals. (Richardson & St. Pierre, 2005)

To position writing as developmental and individualised rather than remedial and centralised.

Badenhorst et al. (Citation2012): shift from ‘what’s wrong with the PhD researcher to how to use curriculum to support success; Barnacle and Dall’alba (Citation2014): shift from skills-based to process-based program approach

G. 2: Develop confidence as an academic writer

To understand how positive emotion around writing can be encouraged and used to improve writing practices.

To make visible the ways in which emotion affects both perception and practice of writing.

Kamler and Thomson (Citation2008); Aitchison et al. (Citation2012): emotionality of doctoral writing interacting with pedagogical practices to impact writing development

G. 3: More critically assess your own and others’ writing

To encourage separation of self as writer from the object of writing in order to see their own writing as others might.

To review other authentic doctoral writing from peers as well as critique published writing.

Caffarella and Barnett (Citation2000): preparing and receiving critiques is perceived to be most influential element in helping doctoral researchers understand the iterative formative nature of writing

G. 4: Develop skill in giving, receiving and using constructive feedback

To develop expertise in critiquing others’ texts in order to encourage critical distance on participants’ own writing.

Aitchison and Lee (Citation2007): value of small group work in enabling understanding of value of giving and receiving feedback

G. 5: Become more strategic in your reading, both what and how

To understand how they each located themselves in the scholarly community or network.

To explicitly consider the relationship between reading and writing.

Haas (Citation1994): texts filled with purpose and motive, linked to the individuals and the cultures that produce them; this knowledge can be used to make a place for self as author

Role of plenaries

We wove the goals/thematic strands across the five plenaries through different types of activities. (See Appendix A for overview.)

Goal 1: The participants’ goals prior to the program were collated, reviewed and discussed during the first plenary. We wanted participants to have perspective on the direction of the program as well as the individual goals of their peers (Badenhorst et al., Citation2012). Further, we prompted individuals, to review their own goals during the program, for instance, in both mid-program surveys. During the last plenary, participants reviewed and revised their goals, as appropriate, and created individual implementation plans (concrete actions with timelines).

Goal 2: In the plenaries, we regularly discussed the emotions individuals reported and linked these when possible to the literature to demonstrate the centrality of positive and negative emotion in writing and getting feedback (Aitchison et al., Citation2012; Kamler & Thomson, Citation2008). For instance, participants created journey plots, graphical images, to articulate their emotional responses in preparing to receive and responding to feedback on a piece of writing. These were discussed in small groups and then in plenary.

Goal 3: We introduced participants to a range of writing concepts and academic genres: fluid conventions that readers will recognise that provide a basis for writers to create discourse (Beaufort, Citation2000). We chose genres based on the ones individuals had reported in their applications, such as abstracts and journal articles. Other writing-related notions included: voice, persuasion, inter-textual network. Generally, our intent was to offer participants new ways of thinking about analysing and critiquing their writing, as well as the writing of others.

Goal 4: Participants were introduced to group structures and roles as well as strategies for giving and receiving feedback in the first plenary (Aitchison & Lee, Citation2007). When they met in their working groups, among other things, they took turns receiving feedback on their writing, and then reported in a structured fashion (emailing us a summary using a template) as well as more informally in the plenaries.

Goal 5: Participants were introduced to the notion of their intertextual network, i.e. the scholars past and present they connect to (Ivanic & Camps, Citation2001) through a mapping exercise to visualise the key scholars they drew on. This meant that they drew a map of relationships that showed how they connected themselves to different scholars (past and present) who influenced their thinking about their present research. We encouraged them to review and update their networks from time to time.

Role of working groups

In between plenaries, participants met in their working groups to offer feedback on each other’s work (goals 3 and 4) or focus on a particular element of writing discussed in the most recent plenary (goals 1, 2 or 5). We created these groups being attentive to variation in experience and in field/specialism, with the aim to avoid scholarly arguments within their own fields and instead focus on ways to make their writing more successful. (These working groups tended to work together in the plenaries.) We chose the term ‘working group’ consciously in recognition that individuals would engage in a number of different activities related to writing.

Research methods and design

While we took a narrative stance (Elliott, Citation2005) in examining participants’ learning journeys, we designed the inquiry as a whole through the lens of a program evaluation, drawing on the principles underlying instructional design (Amundsen & d’Amico, Citation2019). This meant a longitudinal multi-pronged qualitative approach to data collection and analysis to ensure that we could track the experiences of participants over time: before, during and end of program.

Recruitment

In designing the program, we recruited doctoral participants in a college in a UK university through an email inviting them to take part in the program. The participation criteria were that they a) imagined an academic careerFootnote2 and b) wished to improve their communication skills. If interested, they returned a form that provided baseline information about their reading and writing experiences, their own writing goalsFootnote3 for the program (specifying up to three) and a commitment to attend the plenaries, the dates of which were included in the application to make clear this was a program, not a series of discrete workshops. We sought consistent participation given the design and evaluation premise was of a slow iterative learning investment. As well, consistent participation would enable us to examine fully the ways in which participants engaged with and learned from elements of the program. Eighteen expressed interest: 14 were in the social sciences and four in the humanities. Before participating individuals gave ethical consent.

Participants

We report on the experiences of five of the participants (using pseudonyms) based on the following criteria. First, they were in the social sciences and humanities so generally shared scholarly writing traditions. Second, before the program, their level of comfort in writing was average or above average (from 5–8 on a 10-point scale), so they were chosen for this case study to see if our developmental approach had learning benefits for individuals who already held relatively positive views of themselves as writers. Further, they a) consistently provided data prior to the start, during and post-programFootnote4; and b) attended all the plenaries, so we had a full longitudinal data set for each. The five were in their 2nd or 3rd year of doctoral study, so well along in their programs, given the UK focus on finishing in three years.

Anna, Education, writing comfort: 6 (scale of 1-10 with 10 very comfortable)

David, Anthropology, writing comfort: 7/8

McCreadie, Education/Interdisciplinary, comfort level 5

Vanessa, International Development, comfort level: 5

Yasmin, Theology, comfort level: 6

Data collection

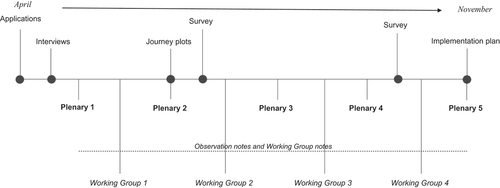

As noted earlier, participants completed an application form before the program asking them to articulate their experience of scholarly communication: experience of different genres, co-authorship and communication challenges, strategies and personal goals. Responses included short answer, sentence completion, scales and choices from lists. (See for data collection timeline.)

Participants also completed two further surveys during the program (after plenaries 2 and 4). These included some of the same questions as the application form and documented a) their progress on their personal goals, b) which strategies they had tried out of the ones we had introduced,Footnote5 and c) the extent to which they had found each one useful. As noted previously, each participant created an implementation plan in Plenary 5.

As well, data were collected during the plenaries: a) individual journey plots (previously described), b) observation notes of the interaction in plenaries (kept by whichever of us was not facilitating the session), and c) working group ‘reports’ in plenary (written on flip charts at the time in which the events took place). In addition to these data, we also drew on written reports of the sessions of each working group on the structured form provided. All data were stored in an online secure location for easy access by both authors.

Analysis

We used an iterative thematic analysis common in narrative research, theorising first within each case rather than deriving themes across cases (Riessman, Citation2008). This approach aligns well with a holistic perspective on intentions and experiences through time: the narrator, an active agent (Elliott, Citation2005), makes connections between events, and demonstrates the influence of time in carrying the action forward (Coulter & Smith, Citation2009). The intent is to understand the chronological arc of meaning in an individual’s experience.

This meant all the data provided by each of the five participants (as well as relevant aspects of the plenary and working group meeting notes) were read through and discussed by both authors to seek each individual’s expressions of engagement, investment: goals, related emotion, interaction with community, and response to new tools and strategies. Then, drawing on this discussion, the first author created a chronological narrative for each of the five, including quotes, about the interaction among these elements, with the second author reviewing these cameos drawing on her knowledge of the data. These rich low-inference descriptions of individuals’ accounts of their experiences over time (Elliott, Citation2005) formed a basis for the two authors to discuss and interpret the individual journeys; we then explored how the accounts resonated with the data from all participants to seek patterns of similarity and difference.

Results and discussion

What were the participants’ views of themselves as writers and of their own writing development in relation to their program experience?

Here we report the findings, integrating them with discussion. We begin by introducing two individuals to offer a longitudinal personal representation of program experience. First, Vanessa who was average in her confidence beforehand, and then David, who expressed the most confidence of the five. These cameos provide a sense of how individuals developed, changed or added to their personal goals over the course of the program; their emotional stance to writing (and changes, if any); and the role of any program elements in their developing communication practices (both concrete tools and social interaction). Then, we move to the patterns that emerged across the group.

Cameos

Vanessa, in her application, described the program as a way to ‘learn [writing’s] nuts and bolts’. Her starting goal was ‘to understand the main aspects of academic writing and use them in my writing’ because ‘I want to communicate my ideas and analysis to my audience clearly’. Her stance was more pragmatic and less emotive than Yasmin’s (‘I love to write … even if only writing for myself!’). However, she recognised that understanding her readers was essential to her success (Kamler & Thomson, Citation2008). Vanessa’s goals for the program also focused on the role of the community of her peers in enhancing her writing practice from the beginning: with specific goals to ‘learn from other participants’ and have ‘a meaningful workshop experience’ (Aitchison & Lee, Citation2007).

In the first mid-program survey, she was still working towards her original goals. She added an additional priority: to use effective writing strategies and improve her written work for her dissertation and publications (Badenhorst et al., Citation2012). In the second mid-program survey, she affirmed her original goal by naming the tools practiced in the program to date. She stated: ‘My overall goal of understanding academic writing is the same – but now specific focus on voice … intertextual network’ (Haas, Citation1994), genres’.

The introduction of new tools and strategies gave Vanessa a greater sense of command of her writing (Richardson & St Pierre, Citation2005). When asked to reflect on her goals at the end of the program and complete the implementation plan, Vanessa signalled that she wanted to continue with her overarching goal to improve her academic writing but that she had completed her other two goals, i.e. to learn from other participants and to share her questions and have a meaningful workshop experience. She used the implementation plan to add two new goals; use the tools learnt in the workshop and follow a regular writing schedule (Richardson & St Pierre, Citation2005). In fact, while completing this plan, Vanessa commented on how ‘vague’ she felt her original goals had been; we wonder the extent to which this was due to an initial lack of specific discourse to describe the elements of writing that she had really wanted to focus on. Her final goals were more concrete and demonstrated clarity around those elements she wished to continue to improve: voice; genre moves, that is, functional units in a text serving a specific purpose (Swales, Citation1990); reverse outlining (a practical exercise to identify the structure of paragraphs in a text); etc. She now had a discourse for talking about writing.

Vanessa’s experience of the small working groups was positive and she felt that her peers had been ‘supportive and helpful’. As a result, she had incorporated their feedback into her draft work (Aitchison & Lee, Citation2007). Vanessa had clearly set out from the beginning to use her peers in improving her writing and so this outcome is perhaps not surprising. In the final implementation plan, Vanessa’s sense of developing confidence is portrayed in her emotive statement that she now writes because, ‘I have something to say and I want to say it clearly’. A stronger sense of her awareness of rhetoric as a persuasive device is newly present in this final statement (Kamler & Thomson, Citation2008).

David had significant writing experience (and publications) before the program: ‘I’m good at it; I want to get better’. He positioned himself as a good writer and his application confirmed he had experience of a range of genres and numerous strategies in place to support both effective reading as well as writing. His goals were ‘self-discipline in writing, a clear and engaging academic prose style and produce a good volume of written/publishable work’. Still, he identified his challenge as procrastination: ‘Getting started. Buckling down. Putting in the hours’. He also noted ‘there is always more to read before I get started’. Like Yasmin and Vanessa, he was aware of the need to situate his thinking inter-textually (Haas, Citation1994).

David saw the program as a way of refining his writing, but his goals suggests he saw writing as a solitary rather than community activity (Aitchison & Lee, Citation2007). He continued working towards the same goals throughout, adding another goal on the second mid-program report related to genres (genre-specific knowledge), one of the new concepts he found productive:

The concept of ‘genres’ has enable[ed] me to see how certain aspects of my work can fit better in some venues than others. I aim to produce more work for a greater variety of genres, especially peer-reviewed papers and popular media such as blogs.

Initially, David felt the small working group supported his aim of increased working time and increased production, stating on the first mid-program survey:

The group imposes a deadline to submit and critique written work. It forces [me] to produce coherent, if not polished, work under time pressure. … The group then takes some of the burden of editing from the writer and offers perspective and analysis the writer might otherwise lack.

Notably, this support was linked to writing as emotional ‘labour’ – the group ‘imposes’ and ‘forces’; there is ‘pressure’ and ‘burden’, suggesting a view of writing more functional than developmental (Badenhorst et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, David’s language reflected purposive behaviour (Richardson & St Pierre, Citation2005) with his goals to ‘put in effective hours’ and ‘produce a good volume’ of written work. Perhaps this is why David’s later evaluation suggested the peer work was not serving his purposes – whereas the other four and participants in general reported the value of these discussions. Interestingly, David’s group changed its format during the program (we do not know David’s role in this) to a ‘shut up and write’ format where time dedicated to writing was guaranteed. We saw it as positive that the group felt empowered to do this (Richardson & St Pierre, Citation2005), especially as this shift in the purpose of the community proved useful enough that they continued meeting after the program and invited new members.

In his final plan, David reported progress in his initial goals. As regards ‘effective hours’, he had now made writing a daily routine and wanted to allocate more time to it. He added another goal regarding his dissertation: to write daily as least 1000 words, and keep a calendar with goals and deadlines to track progress (Richardson & St Pierre, Citation2005). As well, he had come to realise the emotional nature of writing: ‘everyone has the same struggles – with time, discipline and structure of writing’ (Kamler & Thomson, Citation2008).

Patterns

We found participants incorporated many elements of the developmental approach, including goal setting and review, dealing with emotion, metacognitive talk (tools/resources) about their writing, valuing others’ perspectives, and viewing writing challenges as shared. Most, but not all, developed a broader understanding of learning to write as an exploratory learning process. Finally, the data collection and analysis structure proved productive, not just for the inquiry, but also formatively during the program – both for participants and facilitators. We expand on these points below.

Efforts to be agentive: Goal setting

These individuals already saw themselves as writers before they began the program, yet still wanted to invest in the program and had personal goals to work towards. At program end, all felt they had made progress, if not accomplished, their original goals. Further, all created new goals that had more clarity, more focus, and nearly always drew on their new knowledge of writing processes. Their goals and related comments at the end suggest a sense of mastery and confidence not present in the original goals, as well as an awareness that they could be agentive in achieving these goals; even to the extent of the change in David’s group as to their small working group purpose (Richardson & St Pierre, Citation2005; Tardy et al., Citation2020).

Managing emotions

Their emotional stance to writing was evident in nearly all the data, beginning with their initial goals and desire for a unique and powerful writing style (Aitchison et al., Citation2012). While most continued to report both positive and negative emotions, some expressed a greater understanding of the role of emotion. For instance, Anna in recognising the normative negative discourse around doctoral experience; McCreadie in naming the effort required to invest in writing even when change might not always by visible; and David and Yasmin in coming to understand that all had the same struggles. By the end, most individuals had a better sense of how to manage the related emotions when facing future writing challenges.

Program tools to gain greater command

The evidence suggests these individuals had new tools to enhance their flexibility in contributing to their field through different forms of communication. First, the new critiquing strategies we introduced and participants practiced provided a foundation on which to build as they continued to progress their careers. All referenced different program elements in either the second survey or final implementation plan, as well as in the plenaries and working group notes. For instance, Yasmin, Vanessa, McCreadie and David named ‘genres’ (Anna was aware of them at the start of the program) as offering a new perspective: note Yasmin referred to previously ‘unnoticeable genres’. Further, individuals also cited ‘voice’, ‘writing process’, and ‘community’. They had a stronger sense of the multiple ways in which they might communicate: their knowledge of the underlying structures in these different and sometimes key genres (e.g. abstracts) provided a sense they could be more persuasive. Thus, participants had taken on a discourse and a way of thinking about their writing that was different from before the program, as they became increasingly sophisticated and flexible writers (Tardy et al., Citation2020). While we cannot know what the future holds, we conclude that this relatively short investment of time on their part should continue to reap expanding benefits as they have new ‘tools’ with which to achieve their goals.

Community orientation

Aside from David, the other four named and identified with the community aspect of the program (recall Vanessa’s comment): their new inter-personal network which, if only temporarily, supported their growing sense of confidence and flexibility as writers. This network provided a visible, defined space for discussion of scholarly communication, which prompted an explicit understanding that developing as a writer was challenging, yet a common and ongoing process. Further, their exchanges enhanced their metacognitive knowledge of writing and genre (Tardy et al., Citation2020). It is unlikely they had other communities in which to have such conversations. There was also a growing awareness that they needed to understand, if not belong to, any set of readers they wished to engage with and perhaps influence.

Intertextual nature of writing

Three of the five, Vanessa, Jasmin and David referred to the contemporary and historical relationships among ideas/scholars that they drew on. However, overall, references of this type were limited across all participants. We speculate this ‘absence’ might be due to: a) none of the participants sharing the same inter-textual networks given their diverse research focuses (so no points of comparison to discuss); and b) the focus in the program on their shared inter-personal network (the plenary and working group communities) with much less explicit attention to their inter-textual ones.

Writing stance

Amongst the five as well as the other participants, David stands out for his functional, strategic stance throughout the program: viewing writing as labour, small group deadlines creating pressure, the desire to produce volume. Though the others did not express such views, the notion of writing as a requirement for the PhD (Cotterall, Citation2011) was present. Anna, for instance, said she wrote because ‘it’s a way to figure things out and also because I have to!’ Still, the five, including David, benefitted from the developmental elements, such as goal setting and review, new writing strategies and discourse and integrated them into their own writing efforts. This suggests the elements in a developmental program can still be usefully explored and taken up by participants without their making a shift in their view of writing; in fact, this process may take much longer than eight months.

Inquiry design

Our choice of research design was premised on our developmental perspective with the intent to track individual perspectives over the length of the program (Amundsen & d’Amico, Citation2019). In reflecting on this rationale, we have come to realise that it was particularly productive. The data served us well in doing the inquiry analysis. Further, both participants and we, as facilitators, were able to draw on these elements formatively in our respective practices during the program. For instance, we used the information when refining later plenaries as well as summarising the results to report to participants as to variation in the group. As well, participants could (and were asked to) return to their earlier responses to consider their personal goals and progress. In our view, this synergy between inquiry and instructional design offers a possible model for future writing-program design.

Significance/Value of research

We began by arguing that, despite a common view that academic writing is a functional, instrumental activity, in fact, developing communicative fluency is an ongoing, iterative exploratory process. It requires effortful action, draws forth emotional responses (often negative), and involves engagement with scholarly communities (e.g. Richardson & St. Pierre, 2005). Since PhD researchers often find such learning a challenge, we wanted to design a program based on a process approach and assess its effectiveness in supporting PhD researcher writing development, even for those who already felt relatively confident as writers. Further, we designed the data collection to be useful during the course for both participants and us as designers. The results support the notion that we can frame writing support as a pedagogy of growth (Cotterall, Citation2011) since these writers were relatively confident as writers to begin with. In other words, the inquiry provided rich evidence of the potential power of a developmental, community-oriented writing program to advance the writing practices of the participants: to help them develop new critiquing strategies, confidence and greater ownership of their writing processes – regardless of whether they held a developmental or strategic notion of writing. Further, by integrating the instructional and inquiry design elements (Amundsen & d’Amico, Citation2019), we were able to a) use learning strategies to encourage participant reflection in relation to program goals, b) use the data as formative feedback for participants and our own planning, and c) track participants’ longitudinal learning journeys.

Of what value are these findings for those supporting doctoral researchers’ writing trajectories? The findings suggest that writing support conceived as a) a program (not a workshop) with b) a developmental growth perspective, focused on c) introducing and enabling mastery of key writing process concepts can enhance participant confidence as growing scholars.

Future research could consider the extent to which both frequency of meetings and length of program may influence writing development as this is as yet unexamined. As well, what kind of design would better integrate a focus on inter-textual networking given a knowledge of the field is central to writing development?

In closing, academic literacy comprises both thinking critically and taking action that can contribute to one’s chosen field (Florence & Yore, Citation2004), and increasingly other audiences. For PhD researchers, developing fluency to engage in a range of communication practices requires investment of time, energy and emotion – and the ability to learn how to manage emotion so that it becomes a vehicle for moving forward rather than stopping or procrastinating. The real issue though is that generally (with some exceptions) institutions have not seen it as their role to provide pedagogical writing development support. How we might engage them in doing so remains an open question – one we hope those with similar views to ours will take up.

Ethics approval

The studyreceived ethics approval from the University of Oxford CentralUniversity Research Ethics Committee (SSD/CUREC/14–015).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lynn McAlpine

Lynn McAlpine’s research interest in PhD careers has evolved over time. Her early research in this area followed scientists and social scientists for up to seven years as they navigated their careers and personal lives during and after finishing the PhD. Seeing how many did not remain in the academy led her several years ago to studying post-PhD careers outside the academy. Overall, her interest is how PhD graduates navigate their own desires amidst global trends for highly skilled workers, national policy regimes and institutional affordances and constraints.

Corinne Boz

Corinne Boz’s research interest is in academic literacies and the pedagogies that promote them. She has focused on writing practices in higher education at different stages of the academic trajectory from students making the transition into university disciplinary writing through to early career researchers developing writer identities. She is currently the Director of the Academic Centres Division and Professor of Continuing and Online Education at the University of Cambridge, Institute of Continuing Education.

Notes

1. We are academics interested in communication studies who wanted to design and evaluate a program such as this.

2. This was so that they would share similar writing interests, given the importance of the group work.

3. Their goals strongly influenced our design, particularly Goal 1. (See goals and rationales above).

4. The research approach involving multiple data points for each individual ensured that any benefit (or disadvantage) emerging from the program might be documented.

5. e.g., analysing an article abstract from a genre-perspective and then rewriting one of their own; analysing their own texts from the perspective of voice.

References

- Aitchison, C. (2009). Writing groups for doctoral education. Studies in Higher Education, 34(8), 905–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902785580

- Aitchison, C., Catterall, J., Ross, P., & Burgin, S. (2012). ‘Tough love and tears’: Learning doctoral writing in the sciences. Higher Education Research and Development, 31(4), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.559195

- Aitchison, C., & Lee, A. (2007). Research writing: Problems and pedagogies. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510600680574

- Amundsen, C., & d’Amico, L. (2019). Using theory of change to evaluate socially-situated, inquiry-based academic professional development. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 61(5), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.04.002

- Badenhorst, C., Moloney, C., Rosales, J., & Dyer, J. (2012). Graduate research writing: A pedagogy of possibility. Learning Landscapes, 6(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.36510/learnland.v6i1.576

- Barnacle, R., & Dall’alba, G. (2014). Beyond skills: Embodying writerly practices through the doctorate. Studies in Higher Education, 39(7), 1139–1149. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.777405

- Beaufort, A. (2000). Learning the trade: A social apprenticeship model for gaining writing expertise. Written Communication, 17(2), 185–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088300017002002

- Caffarella, R., & Barnett, B. (2000). Teaching doctoral students to become scholarly writers: The importance of giving and receiving critiques. Studies in Higher Education, 25(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/030750700116000

- Cotterall, S. (2011). Doctoral students writing: Where’s the pedagogy? Teaching in Higher Education, 16(4), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.560381

- Coulter, C., & Smith, M. (2009). The construction zone: Literary elements in narrative research. Educational Researcher, 38(8), 577–590. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09353787

- Cuthbert, D., Spark, C., & Burke, E. (2009). Disciplining writing: The case for multi-disciplinary writing groups to support writing for publication by higher degree by research candidates in the humanities, arts and social sciences. Higher Education Research and Development, 28(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360902725025

- Elliott, J. (2005). Using narrative in social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020246

- Florence, M., & Yore, L. (2004). Learning to write like a scientist: Coauthoring as an enculturation task. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(6), 637–668. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20015

- Haas, C. (1994). Learning to read biology: One students’ rhetorical development in college. Written Communication, 11(1), 43–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088394011001004

- Ivanic, R., & Camps, D. (2001). I am how I sound: Voice as self-representation in L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 10(1–2), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1060-3743(01)00034-0

- Kamler, B., & Thomson, P. (2008). The failure of dissertation advice books: Toward alternative pedagogies for doctoral writing. Educational Researcher, 37(8), 507–514. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08327390

- Lea, M., & Stierer, B. (2009). Lecturers’ everyday writing as professional practice in the university as workplace: New insights into academic identities. Teaching in Higher Education, 34(4), 417–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902771952

- Richardson, L., & St Pierre, E. (2005). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 959–978). Sage.

- Riessman, C. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

- Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge University Press.

- Tardy, C., Sommer-Farias, B., & Gevers, J. (2020). Teaching and researching genre knowledge: Toward an enhanced theoretical framework. Written Communication, 37(3), 287–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088320916554