ABSTRACT

We investigated the impact that teachers’ participation in a short compulsory course on active learning had on their teaching practice. The course was offered at all departments of a STEM faculty with a total of 516 participants. Evaluations showed that teachers especially appreciated collegial discussions and examples of teaching practices in the course. In a survey, 64% indicated the course had led them to implement active teaching. Comparing large-scale pre-course and post-course student surveys with up to 2389 individual responses revealed a significant increase in the number of courses with active learning. The course as a change strategy contains aspects of both middle-out and top-down approaches and organising the course at departments, enables movement from individual to structural level.

Introduction

In the 1990s the changes in higher education that had started already in the 1970s intensified towards internationalisation, globalisation, and a new paradigm of evidence-based educational policies. Although evidence-based policies have stimulated empirical research in higher education, the opposite is not necessarily true. Results from research studies have not influenced policy making as much as may have been expected (Zgaga et al., Citation2015). This is true when it comes to ‘scientific teaching’ and strategies for active learning. In this paper, we adopt the working definition of active learning as ‘anything that involves students in doing things and thinking about the things they are doing’ (Bonwell & Eison, Citation1991). Studies show benefits of student-activating teaching for students’ learning (see e.g. Deslauriers et al., Citation2011; Freeman et al., Citation2014), but it is known that the process of implementing new means of activating students is typically slow (Handelsman et al., Citation2004). In a meta study, Freeman et al. (Citation2014) showed an improvement in examination scores in active learning sessions compared to traditional lecturing, and students are less likely to fail. Active learning has also been shown to narrow the achievement gap of underrepresented students compared to other students (Theobald et al., Citation2020).

The change process

Considering the perceived benefits of active learning, it is critical to understand the barriers to implementing such practices. A recent review analysed these barriers through three categories; Leadership and organisation, Technology and Teaching competence and training needs (Børte et al., Citation2023). Focusing on the teachers, it becomes important to find ways to implement changes to their practice and to establish a community of practice (Wenger, Citation1998). How to best promote changes in teaching practice, top-down or bottom-up, is a research field on its own (Bradforth et al., Citation2015; Brinkhurst et al., Citation2011; Cummings et al., Citation2005; Henderson et al., Citation2011). Cummings et al. (Citation2005) characterises the top-down approach as leadership from the top, linked to university vision or strategic plan. Changes are made through imposing these central policies, which are supported through centrally allocated resources, infrastructure and funding. The bottom-up approach involves individuals or small groups of academics solving a particular problem, motivated by their self-interest in finding a solution. They work within a collegial and decentralised culture to achieve change at lower levels, e.g. departmental levels.

By analysing the effects of educational reforms, Fullan (Citation1994) drew the conclusion that neither purely top-down nor purely bottom-up approaches would work when applied in isolation. The policy set on higher levels does not have the impact intended by policymakers. Moreover, change initiatives not aligned with cultural and operational norms at lower levels, in this case departmental levels, are not likely to be successful. It is therefore important to transform departmental cultures so that they support educational development (Corbo et al., Citation2016). Trowler et al. (Citation2003) reached the same conclusion and emphasised the need to work from the ‘middle out’. The middle-out approach includes aspects from the other two extremes (Cummings et al., Citation2005) but is characterised as very problem-oriented and operational. In academic development, middle-out has been applied in different contexts and for different actors (Hodgson et al., Citation2008; Reinholz et al., Citation2019).

The analysis of the scholarship concerning changes in instructional practices, provided by Henderson et al. (Citation2011), characterise core differences along two dimensions. The first dimension is the target for change, ‘Individuals’ or ‘Environments and structures’. The question is whether teacher practice is mainly influenced by their own volition or by external structures. The second dimension is if the intended outcome has been decided in advance, i.e. is it ‘Prescribed’ or ‘Emergent’. In the former case, there might be a consensus of the goal at the beginning of the change process. In the latter case, the goal is developed as a part of a critical and collegial change process. Henderson et al. found that top-down approaches (Environments and structures/Prescribed) do not work, and to be successful, strategies have to be aligned with, or seek to change, the beliefs of the individuals involved.

Teacher training courses

One common change strategy is to implement teacher training courses. These courses have positive effects on teaching quality and learning (Gibbs & Coffey, Citation2004; Postareff et al., Citation2007) and include more student-centred learning and corresponding higher student satisfaction (Kember, Citation2009). Teachers report higher teaching-related self-efficacy, connected to more confidence in their knowledge about teaching and learning (Fabriz et al., Citation2021; Ödalen et al., Citation2019). However, to get the full effect of compulsory teaching courses requires strong support for ‘a culture of continuous improvement and professional development’ (Trowler & Bamber, Citation2005, p. 90). In Sweden, where the present study was carried out, the Higher Education Ordinance (government level) requires that teachers with permanent positions have completed compulsory teacher education. At Uppsala University, Sweden, many teachers fulfill part of a 10-week requirement through a general teacher training course provided by the central unit for Academic Teaching and Learning at the university. As both the course requirement and the organisation come from the university level, we classify this as a top-down approach.

The context

In 2016, the Faculty of Science and Technology at Uppsala University, Sweden, (hereafter the ‘Faculty’) decided to establish a high proportion of student-centred and student-active teaching forms on all education programmes at the Faculty. This decision emerged from collegial discussions at the Faculty, where several actors, including teachers, were pushing for increased use of active learning practices. The Faculty set out to map the variety of teaching methods used in all STEM education programmes and decided that a short training course covering both the meaning of student-active teaching and a variety of implementation examples should be taken by all teachers at the Faculty within 3 years.

The task of developing and giving this compulsory training course was given to TUR, the Council for Educational Development at the Faculty of Science and Technology. TUR is responsible for the pedagogical development and education of teachers at the Faculty. The council’s senior staff serve on a part-time basis and come from different disciplines and fields of expertise.

The first aim of this study was to understand the effect of a short compulsory course on the amount of student-activating teaching at a research-intensive university where most participants already had prior teacher training. The second aim was to analyse the teachers’ opinions about the course to be able to support best practice for implementing similar compulsory activities in other contexts.

Materials and methods

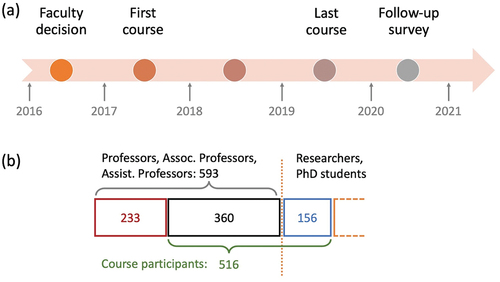

The faculty decision to increase the proportion of student active teaching was taken in 2016 (see ). The course was mandatory for faculty members within 3 years. In addition, PhD students and researchers with teaching duties were welcome to attend. TUR designed a short training course (3 h) covering both the meaning of student-active teaching and a variety of implementation examples of student-active teaching. The first Student Centered Teaching and Learning course was given in Spring 2017 and the last at the end of 2019. Three of the authors of this article took part in giving the course.

Figure 1. (a) Timeline for the course. (b) Overview of the number of teachers at the faculty in 2018 and number of course participants (516 in total). The left-hand side includes the entire teacher category, tenure, and tenure-track for which the course was compulsory; the right-hand side are non-tenure staff, some with teaching duties, for which the course was optional.

Course design and content

The course was given as a three-hour activity at departmental rather than faculty level. This enabled TUR to adapt the course content to the specific discipline of each department. We invited teachers from the department with experience in using student-centred methods in their teaching, to make short presentations of their methods and results. Some of these examples we also presented when giving the course later in other departments.

We initiated the course with a discussion on what our focus in teaching is – receiving or processing information, and the need for a shift in perspective for teachers and students towards more student-centred teaching. We introduced the concept of ‘Scholarly practice’ and that it entails engagement with literature, reflection on practice, communication with others, and adoption of suitable perspectives on what learning means (Boyer, Citation1990). As Uppsala University is a research-intensive institution, we early on focused on establishing that the recommendation of using student-centred methods is based on scientific evidence. In order to accomplish this, we presented and discussed seminal studies from STEM that showed this (e.g. Deslauriers et al., Citation2011; Freeman et al., Citation2014).

To ‘teach as we preach’, we used activating methods during the course. This encompassed several collegial discussions in smaller groups and in the main group, an exercise using post-its to make an inventory of the student-centred methods used at the department, a value exercise, and mentimeter questions on teachers’ views.

Evaluations

We employed evaluations in three different ways corresponding to different time scales: (i) end-of-course evaluation from participating teachers, (ii) teacher follow-up survey, and (iii) student surveys (2016–2022). The end-of-course evaluation was administered on site and thus includes teachers participating in the course. The follow-up survey was sent to all tenured teachers employed at the Faculty in June 2020. Course participants without tenure were not asked to fill in the survey. Student surveys were sent out to all students at the faculty registered at a study programme. In the two teacher surveys, no background questions were asked. In the end-of-course evaluation, participants were only identifiable by department. In the follow-up survey, they were fully anonymous. In the student survey, we only had access to aggregated data by study programme. As all answers are given voluntarily and cannot be coupled to sensitive personal data, no ethical approval was needed.

The course ended with a three-item evaluation: i) what worked well, ii) what could be improved and iii) an option for other comments. We collected a total of 326 written responses. The answers were independently categorised by two of the authors, and then adjustments were made to the categories and category groups after a discussion with all co-authors. All the responses were analysed by department. As there were no notable differences in the answers across the different departments, the results are presented as an aggregate of all surveys.

In June 2020, a follow-up survey was sent to all teachers by email to investigate if the course had influenced them to change their teaching practice towards more student-centred activities. As teachers participated in the course at different times, the delay between the course and the survey ranged from 1 to 3 years. A total of 58 responses were received, which relative to the 516 participants gives an 11% response frequency. The survey included two compulsory items. First, teachers had to indicate the level of agreement for the statement ‘I have made changes in my teaching practice as a result of the course’. Second, a free-text question asking ‘What have you changed? Give examples of student-activation session(s) you have implemented in your teaching as a result of taking the course’. The answers to the two questions were connected in the analysis, i.e. each free-text answer could be matched to the level of agreement with the first statement.

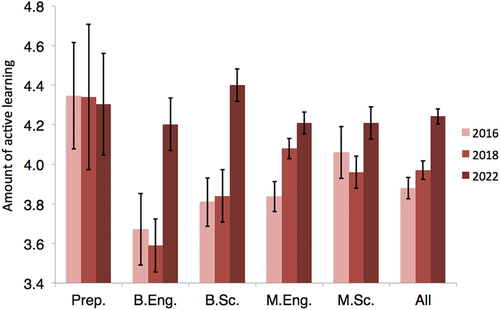

The biennial student surveys are sent out to all students at the Faculty registered at a study programme. The 2022 survey included a total of 58 questions about the learning and study environment organised in 23 categories. A question about active teaching was included for the first time in 2016, and then in all following surveys: ‘During the teaching sessions I have had to actively process the course contents (not only attend)’. The possible answers were: Almost none (1) - (2) – Half the courses (3) - (4) – Almost all (5). As the survey was not administered during the pandemic, the analysis includes results from three surveys, 2016, 2018, and 2022. The surveys were filled in by 1416, 2389, and 2222 students, respectively. The corresponding response frequencies were 33%, 59%, and 41%. The answers have been analysed by the type of study programme: Technical preparatory (1-year programme), Bachelor of Engineering (6 different 3-year programmes), Bachelor of Science (8 different 3-year programmes), Master of Engineering (10 different 5-year programmes), and Master of Science (27 different 2-year programmes and two 1-year programmes). In 2022, the number of responses in each programme category was 70, 190, 338, 1052, and 581, respectively. The 2016 survey represents data before the start of the course, the 2018 survey represents a time point where some teachers had taken the course, and the 2022 survey is a post-course time point. In comparisons between time points, changes are considered significant if there is no overlap between the 95% confidence intervals of the mean.

Results

At the end of 2019, TUR had given the course Student Centered Teaching and Learning on a total of 26 occasions in the following subject areas: biology, chemistry, earth sciences, engineering sciences, information technology, mathematics, and physics. In addition, the teachers also had two opportunities to take the course at Faculty level. A total of 516 participants attended the course (see ) of which 360 participants in the teacher category and 156 PhD students and researchers with part-time teaching duties. The numbers correspond to 60% of 593 teachers employed at the Faculty during 2017–2019 that were mandated to take the course.

Course evaluation from participating teachers

contains the participants’ answers to the question what was good with the course, and what could be improved. The answers were grouped into eight categories for the first question and nine categories for the second. These categories were further assigned to three and four category groups, respectively.

Table 1. Identified categories for all the free-text answers in the course evaluation for participants in the course, aggregated over all answers, with examples.

Table 2. Identified categories for all the free-text answers in the course evaluation for participants in the course, aggregated over all answers, with examples.

A majority of the answers to the question Was there anything especially good with the course? could be placed in the two categories ‘Examples on active teaching from colleagues’ (67 answers) and ‘Discussion, dialog, collegial’ (58 answers). One comment was ‘Examples and lively discussions, made seminar relevant and gave possibility for exchange’. These two categories were both classified as being part of collegial reflection (‘Sharing experience’; a total of 125 answers). Four of the categories (‘Generic unspecified, positive answer’, ‘New active, useful methods’, ‘Course setup’, and ‘Practical, interactive activities’) were grouped in the category group ‘Confirmation on good setup’ with 98 answers. One opinion was ‘Good use of active learning techniques throughout the course’. A few answers were positive in a more introspective way (‘Opportunity for reflection’ and ‘Confirmation’).

For the second question, What could be improved with the course?, many of the answers related to ‘Suggestions on course setup’ (76 of 169 answers). The participants thought that more structure and activating of the participants were needed and that the course should be longer, or, on the contrary, shorter. Another category group with many comments was ‘Requests for more content’ (64 of 169 answers). This category could be subdivided into three category groups: ‘More (general, practical) examples’, ‘Missing topics’, and ‘More discussions’. One teacher wrote ‘More discussions of difficulties during student-centred activities could be very helpful’. In 11 answers, the teachers requested more scientific evidence on student activating teaching.

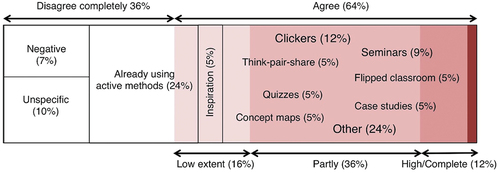

Teacher follow-up survey

For the first statement, ‘I have made changes in my teaching practice as a result of the course’, 36% of the respondents (21 individuals) selected ‘Disagree completely’, see . We used the free-text answers to divide this group into three categories: ‘Already using’, ‘Unspecific’, and ‘Negative’. The largest group (12 respondents) said that they were already using student-active methods before the course and that the course did not change their practice. ‘I already had some student activation and didn’t see the need to increase it further.’ Six respondents did not provide any motivation for the lack of agreement, only stating that ‘I have made no changes to my course’. Four respondents provided clear negative comments about the course, e.g. that ‘the course was a total bore-out!’.

Figure 2. Results of the faculty wide follow-up evaluation after the course, where teachers responded to the statement: ‘I have made changes in my teaching practice as a result of the course’. The answers had five levels of agreement, from complete disagreement to complete agreement, and show a positive impact of the course on 64% of the respondents. Categorized answers to the free-text question ‘what have you changed?’ are shown in text within the diagram. As some have mentioned more than one specific method, the text responses add up to more than 100%.

Looking at the 64% of the respondents (37 individuals) that indicated they had implemented active learning, the agreement ranged from a low extent to complete agreement, see . The group that agreed to a low extent (16%) includes those that are already using active learning methods, as well as those that felt inspired, but had not yet implemented changes, ‘I got inspired by comparing to what colleagues have done and their experiences’. Some respondents with low level of agreement still cite specific activities that they added to their teaching repertoire. As the level of agreement increases, the respondents described specific activities that they have implemented. Finally, some respondents with a high level of agreement claimed that the course not only led to changes in their teaching but also led them to take other pedagogical courses offered by the Faculty:’This course inspired me to take a course in subject didactics’.

In total, 78% (45) of the respondents stated that they used active teaching methods, either before or as a result of the course. An additional 5% (3) had been inspired to use such methods in the future. Among all respondents, 22 provided at least one specific example of learning activities that they had implemented in their courses, e.g. clicker questions, seminars, and concept maps (see ).

Student surveys

To get an idea about the changes in practice at the Faculty, we have analysed a question in the faculty-wide student survey about the presence of elements where the students had to ‘actively process’ the contents of the course. The answers have been grouped by type of study programme, as well as an aggregated number for all students, see . The most important result is a significant increase in the number of courses with active learning elements between the pre-course 2016 survey and the post-course 2022 survey. When looking at all students, the mean value increases from 3.879 ± 0.054 to 4.242 ± 0.038 (95% confidence interval of the mean) during this time span. The corresponding data for the intermediate time point 2018 gives a mean value of 3.971 ± 0.047, between that of the two end points but not significantly different from 2016.

Figure 3. Results from the faculty-wide student surveys regarding the use of active teaching. The question was ‘during the teaching sessions I have had to actively process the course contents (not only attend)’. the answer options range from almost none (1) - half the courses (3) - almost all (5). The columns represent (in order) the technical preparatory year (prep.), Bachelor of engineering (B.Eng.), Bachelor of science (B.Sc.), master of engineering (M.Eng.), master of science (M.Sc.), and aggregated data for all programs at the faculty. Bars represent the 95% confidence interval of the mean.

Looking at results by type of study programme, there is no consistent trend when comparing 2016 and 2018, but the levels of active teaching are generally higher in 2022, with significant changes for three of the groups; Bachelor of Engineering, Bachelor of Science, and for Master of Engineering. The only exceptions to the trend of a significant increase in the amount of active learning are the Technical preparatory and the 2-year Master of Science programmes. The former already had a high level of active teaching reported in 2016, and the small number of students in this group also gives rise to large statistical uncertainty. The Master of Science programmes only have courses at the advanced level. They are often taught to smaller groups of specialised students and might already have included active learning through projects and advanced assignments and would thus be less affected by the type of student-activating methods that were the main focus of the course.

Discussion

We will initiate by discussing the results of the evaluations and surveys, and use these insights to place this teacher training course into the frameworks formulated by Cummings et al. (Citation2005) and Henderson et al. (Citation2011). We will then analyse the effect of the course on teaching practice.

Evaluations and surveys

Based on the answers from the course evaluation’s first question; Was there anything especially good with the course? (), the participating teachers appreciated meeting, discussing, and learning from colleagues in their own subject. This was evident from the answers in the category ‘Examples on active teaching from colleagues’ and almost as many answers in the category ‘Discussion, dialog, collegial’. This result may indicate that the teachers felt they lacked a venue where they could discuss teaching and learning with colleagues in their own department, or, at least, that they would appreciate more opportunities to do so. Some answers to the question; What could be improved with the course? () mentioned ‘More examples’ and ‘More discussions’ as well. This is in line with Knight et al. (Citation2006) showing that ‘conversations with departmental colleagues’ were one of the top three of the teachers’ preferences for additional professional learning. It also matches the findings of White et al. (Citation2016) where participants in an initiative to implement active learning reported that interacting with colleagues already engaged in this practice had a very strong influence. All these observations align with the idea of a community of practice (Wenger, Citation1998).

The teachers appreciated that we used ‘new active, useful methods’ () in the course. They also responded positively to the fact that the course was designed according to the principle ‘teach as you preach’. This entailed implementing examples of active methods throughout the course so that the teachers could ‘learn by doing’. In fact, some teachers wanted to be even more active in the course (). Many participating teachers appreciated that we included ‘Examples on active teaching from colleagues’. We included both local examples from teachers at the actual department but also good examples we encountered when the course was given at other departments. This was an attempt to share best practices, but also to spread examples between subjects and departments, within the Faculty.

The teacher follow-up survey gave similar results as the course evaluation, with the best parts being the local nature of the course and the meetings with, and examples from, colleagues. A relatively small group (7% of respondents, ) provided negative feedback, with most of them commenting on the course being compulsory, and that it was not worth the time of those attending. With the low response frequency, the size of this group could be affected by selection bias, in either direction. Still, it is clear that the fact that the course was compulsory was a major reason for the negative attitudes provided by some respondents, even though the total time required was only 3 h.

Change strategy

When looking at the course as a change strategy, we notice that it contains aspects of both middle-out and top-down approaches. There are two important aspects of the course that are characterised by a middle-out approach; its origin and its implementation. The decision to give the course did not arise from a government or university mandate but rather from collegial discussions within the Faculty, where several actors, including TUR, were pushing for increased use of active learning practices. These discussions were important for the faculty’s decision to establish the course. As organisers of the course, TUR assumes the role of middle-out because although it acts in the Faculty’s interests, it is still separate from the leadership and decisional structure at the Faculty. A key aspect of TUR is that members are also teachers at the undergraduate level, and thus closely linked to the daily activities of the different departments.

In the implementation of the course, the departments were responsible for information and administration. To the largest extent possible, one of the course leaders was from the same department as those taking the course. Together with the involvement of experienced teachers from the individual departments, this reduced the impression of the course being a central mandate.

The course also had aspects of a top-down approach, as the decision to implement the course was taken at the faculty level and that it was announced as compulsory for all teachers. The top-down approach can be credited for the relatively high attendance, as the 516 participants compare favourably to the approximately 60 teachers that annually attend voluntary teacher training courses organised by TUR. We also note that although the course was announced as compulsory, the departments did not implement any consequences for those that did not attend. In the end, 60% of the primary target group attended the course as a result of this ‘soft’ compulsory approach. Enforcement would probably have led to larger attendance, but it is also likely that negative attitudes to the course would have been more widespread.

Using the framework of Henderson et al. (Citation2011), the course at first glance belongs to the ‘Disseminating’ (Prescribed, Individuals) category. The outcome, increased use of active learning methods, is prescribed at the start of the project, and it specifically targets individual teachers. At a closer look, the implementation of the course moves it into other categories as well. Organising the courses at the departmental level enables a movement from the ‘Individual’ to the ‘Environments and Structures’ level. From the course evaluations, the two most frequently mentioned positive aspects: ‘Examples on active teaching from colleagues’ and ‘Discussion, dialog, collegial’ are both relevant for this dimension. Here, we note the role of the ‘soft’ compulsory. In addition to reaching teachers that attended despite not previously prioritising educational responsibilities, teachers that had already adopted active learning methods attended and shared their experiences. Although some teachers in this group did not change their own practice, it was highly positive that they could meet teachers with less experience. This increased the strength of the collegial approach. The teacher-to-teacher interactions also have the potential to move the course from ‘Prescribed’ to ‘Emergent’, as these interactions lead to changes beyond those suggested by the organisers.

Recommendations

To share best practices, we give recommendations for planning and implementing teacher training activities. Based on the results from the evaluations and our experiences of organising a compulsory teacher training course across a large research-intensive university, we propose the following success factors.

Taking a middle-out approach when organising the activity helps reaching higher acceptance from teachers resistant to top-down activities.

Making the course compulsory makes it possible to change departmental culture by allowing teachers with different levels of engagement and experience of teaching to meet.

Design the course according to the principle ‘teach as you preach’, allow ample time for collegial discussions, and show research results on the effectiveness of student-activating methods.

Invite experienced teachers that provide examples of subject specific practice but also share examples between departments to effectively spread new ideas.

Impact of the course

Has the course led to changes in teaching practice at the Faculty? The teacher follow-up survey points towards a positive impact, with 64% of respondents reporting that they had changed their practice to some degree (). Many teachers embrace several approaches, often complementing the ones they were already using. We have limited data on what types of new activities that were implemented, but activities promoting discussions among students are some of the most frequently adopted (McCoy et al., Citation2018). Our evaluation does not differentiate between experienced and less experienced teachers, making it difficult to conclude which category benefits the most from the compulsory course (Ödalen et al., Citation2019). It is likely that the group that had not changed their practice because they had already implemented student activating methods (24%, ), mainly consists of experienced teachers.

The large-scale student surveys clearly show a positive trend towards more active teaching at the Faculty. The large number of responses makes these results statistically reliable. The results should also be unbiased because students answer without being aware of the existence of a teacher course on active learning.

The design of the student survey itself reflects an increasing focus on active learning, with questions about the presence of active learning activities appearing for the first time in 2016 and with increasing detail about the contribution to learning of specific activities in later surveys. Here, we note that the question about the presence of active learning appears in a separate category, well before additional questions about specific activities. Answers to this question should therefore be comparable between surveys. The addition of student-activating methods as a result of the course, as reported by the teachers in the follow-up survey, thus aligns with a student-reported increase in such methods across all the education programmes during this time frame. It is possible that the increase is part of a larger push towards active student teaching, but as an important part of the Faculty’s strategy to promote active learning methods, it is reasonable to assume that the course has had a positive impact. The relatively large effect of a short course, relative to the 10-week course requirement for all teachers, is attributed to the focus on one particular topic. As student-activating methods become more integrated into the basic teacher training courses, the one-time effect of this particular course content might decrease over time. However, the positive outcome of the implemented change strategy will remain.

Limitations of the study

The main advantages of the study are that it analyzes changes from a faculty-wide perspective. The course involved a majority of tenured teachers and the evaluation of the amount of active teaching included a majority of all the students. One limitation is that the teacher follow-up survey, designed to probe long-term effects, had a limited sample across the faculty. The responding teachers might not be representative, which has not been corrected for. That survey also relied on self-reported implementations or improvements in their teaching. Further, the responses do not include non-tenured attendants, many with low levels of pedagogical training. The pedagogical practices of these participants could have been more strongly affected by the activity. The student survey was not administered in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, missing one data point in the time series. More importantly, the amount of active teaching could also be affected by other factors. During the pandemic, teaching was redesigned to fit the online format with student activation using online means. Although teaching had long returned to the original on-site format when the 2022 survey was administered, potential effects of the pandemic cannot be separately accounted for.

Conclusions

We see the development of a culture of student-activating methods as a positive effect, where both students, teachers, course, and programme responsible become engaged in discussions and assessment, leading to a higher level of student satisfaction and teacher confidence. The overall quality of teaching has increased across the entire Faculty owing to a multifaceted approach for educational development, which includes compulsory teacher training like this course, but also teacher collegiums with sharing of best practices, funding for pedagogical development of courses, student-surveys for enhancing quality and more.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Office of Science and Technology at the Faculty for their support, Emma Kristensen for student survey data, Lena Forsell and Sofia Stenler for teacher data at the Faculty. We acknowledge the contribution of the teachers in the course: Maja Elmgren, Jannika Andersson-Chronholm, Magnus Jacobsson, Björn Victor, Malin Östman, Felix Ho, Thomas Lennerfors, and Brita Svensson. We also thank Maja Elmgren and Jannika Andersson-Chronholm for useful discussions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katarina Andreasen

Katarina Andreasen is an education coordinator and educational developer working at the Biology Education Centre and for the Council for Educational Development at the Faculty of Science and Technology, Uppsala University.

Marcus Lundberg

Marcus Lundberg is a senior lecturer and educational developer working at the Department of Chemistry - Ångström Laboratory and for the Council for Educational Development at the Faculty of Science and Technology, Uppsala University.

Stefan Pålsson

Stefan Pålsson is a lecturer and educational developer working at the Department of Information Technology and for the Council for Educational Development at the Faculty of Science and Technology, Uppsala University.

Nicusor Timneanu

Nicusor Timneanu is a senior lecturer and educational developer working at the Department of Physics and Astronomy and for the Council for Educational Development at the Faculty of Science and Technology, Uppsala University.

References

- Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, School of Education and Human Development, George Washington University.

- Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Princeton University Press.

- Bradforth, S. E., Miller, E. R., Dichtel, W. R., Leibovich, A. K., Feig, A. L., Martin, J. D., Bjorkman, K. S., Schultz, Z. D., & Smith, T. L. (2015). University learning: Improve undergraduate science education. Nature, 523(7560), 282–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/523282a

- Brinkhurst, M., Rose, P., Maurice, G., & Ackerman, J. D. (2011). Achieving campus sustainability: Top-down, bottom-up, or neither? International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 12(4), 338–354. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676371111168269

- Børte, K., Nesje, K., & Lillejord, S. (2023). Barriers to student active learning in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(3), 597–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1839746

- Corbo, J. C., Reinholz, D. L., Dancy, M. H., Deetz, S., & Finkelstein, N. (2016). Framework for transforming departmental culture to support educational innovation. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 12(1), 010113. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.010113

- Cummings, R., Phillips, R., Tilbrook, R., & Lowe, K. (2005). Middle-out approaches to reform of university teaching and learning: Champions striding between the top-down and bottom-up approaches. International Review of Research in Open & Distributed Learning, 6(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v6i1.224

- Deslauriers, L., Schelew, E., & Wieman, C. (2011). Improved learning in a large-enrollment physics class. Science, 332(6031), 862–864. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201783

- Fabriz, S., Hansen, M., Heckmann, C., Mordel, J., Mendzheritskaya, J., Stehle, S., Schulze-Vorberg, L., Ulrich, I., & Horz, H. (2021). How a professional development programme for university teachers impacts their teaching-related self-efficacy, self-concept, and subjective knowledge. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(4), 738–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1787957

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(23), 8410–8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

- Fullan, M. (1994). Coordinating top-down and bottom-up strategies for educational reform. Systemic reform: Perspectives on personalizing education (Ronald J. Anson, Ed). OERI, USDE.

- Gibbs, G., & Coffey, M. (2004). The impact of training of university teachers on their teaching skills, their approach to teaching and the approach to learning of their students. Active Learning in Higher Education, 5(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787404040463

- Handelsman, J., Ebert-May, D., Beichner, R., Bruns, P., Chang, A., Dehaan, R., Gentile, J., Lauffer, S., Stewart, J., Tilghman, S. M., & Wood, W. B. (2004). Education. Scientific teaching. Science, 304(5670), 521–522. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1096022

- Henderson, C., Beach, A., & Finkelstein, N. (2011). Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices: An analytic review of the literature. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(8), 952–984. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20439

- Hodgson, D., May, S., & Marks‐Maran, D. (2008). Promoting the development of a supportive learning environment through action research from the ‘middle out’. Educational Action Research, 16(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790802445718

- Kember, D. (2009). Promoting student-centred forms of learning across an entire university. Higher Education, 58(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9177-6

- Knight, P., Tait, J., & Yorke, M. (2006). The professional learning of teachers in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 31(3), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600680786

- McCoy, L., Pettit, R. K., Kellar, C., & Morgan, C. (2018). Tracking active learning in the medical school curriculum: A learning-centered approach. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 5, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120518765135

- Postareff, L., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., & Nevgi, A. (2007). The effect of pedagogical training on teaching in higher education. Teaching & Teacher Education, 23(5), 557–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.013

- Reinholz, D. L., Ngai, C., Quan, G., Pilgrim, M. E., Corbo, J. C., & Finkelstein, N. (2019). Fostering sustainable improvements in science education: An analysis through four frames. Science Education, 103(5), 1125–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21526

- Theobald, E. J., Hill, M. J., Tran, E., Agrawal, S., Arroyo, E. N., Behling, S., Chambwe, N., Cintrón, D. L., Cooper, J. D., Dunster, G., Grummer, J. A., Hennessey, K., Hsiao, J., Iranon, N., Jones, L., II, Jordt, H., Keller, M., Lacey, M. E., Littlefield, C. E. & Freeman, S. (2020). Active learning narrows achievement gaps for underrepresented students in undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(12), 6476–6483. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1916903117

- Trowler, P., & Bamber, R. (2005). Compulsory higher education teacher training: Joined‐up policies, institutional architectures and enhancement cultures. International Journal for Academic Development, 10(2), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440500281708

- Trowler, P., Saunders, M., & Knight, P. M. (2003). Change thinking, change practices: A guide to change for heads of department, programme leaders and other change agents in higher education. LTSN Generic Centre.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- White, P. J., Larson, I., Styles, K., Yuriev, E., Evans, D. R., Rangachari, P. K., Short, J. L., Exintaris, B., Malone, D. T., Davie, B., Eise, N., McNamara, K., & Naidu, S. (2016). Adopting an active learning approach to teaching in a research-intensive higher education context transformed staff teaching attitudes and behaviours. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(3), 619–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1107887

- Zgaga, P., Teichler, U., Schuetze, H. G., & Wolter, A. (Eds.). (2015). Higher education reform: Looking back looking forward. Peter Lang.

- Ödalen, J., Brommesson, D., Erlingsson, G. Ó., Schaffer, J. K., & Fogelgren, M. (2019). Teaching university teachers to become better teachers: The effects of pedagogical training courses at six Swedish universities. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(2), 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1512955