ABSTRACT

This article discusses the process of negotiating the storyline for videos developed as part of an online Arabic language course. The project was guided by a social-justice-through-education agenda, explicitly aiming to redress the high unemployment rate of language graduates in the Gaza Strip. We illustrate how the international team designing the course gradually moved from talking about intercultural communication to doing intercultural communication during the process of creating the course materials. We also explore the meanings that the stories of the language course carry from the distinct perspectives of the teams based in Scotland and in the Gaza Strip.

يناقش هذا المقال عملية التواصل والتفاوض لإعداد قصة عبر فيديوهات تعليمية قصيرة تم تطويرها كجزء من منهاج الكتروني لتعليم اللغة العربية عبر الإنترنت. ويهدف تطويرهذا المنهاج لتعزيز العدالة الاجتماعية عبر التعليم والمساهمة في تخفيف معدل البطالة المرتفع بين خريجي اللغة العربية واللغة الإنجليزية الفلسطينيين في قطاع غزة. ويوضح الباحثون كيف انتقل الفريق الدولي الذي صمم المنهاج تدريجيا من مجرد نقاش حول التواصل بين الثقافات إلى مرحلة يتم فيها إجراء تواصل فعلي بين الثقافات أثناء عملية التفاوض لإعداد القصة و إعداد المادة التعليمية. وسيتم أيضا دراسة المعاني التي تتضمنها قصص المادة التعليمية من منظورين متمايزين للفريق المقيم في اسكتلندا و الفريق الفلسطيني المقيم في قطاع غزة.

Introduction

This article reflects on the role of narratives in the design of the Online Arabic from Palestine (OAfP) language course. The OAfP course was the main output of the research project The impact of language. Collaborating across borders to the design, development and promotion of an online Palestinian Arabic course (hereafter Impact of Language), during which an international team based at the University of Glasgow (UofG, UK) and at the Arabic Center of the Islamic University of Gaza (IUG, Palestine) collaboratively developed an Arabic language course for beginners. In this article we investigate the ways in which the team negotiated the tensions that emerged during the drafting of a storyline for the videos of the course, tensions which created a ‘between space’ (Clandinin, Murphy, Huber, & Orr, Citation2009, p. 82) in which different stories could converge.

Throughout this article, narratives are seen as both a phenomenon and a method, as we explore the evolution of the story-based materials for the course, and, at the same time, use some elements of narrative inquiry to analyse our experiences of telling the story (Clandinin, Citation2006). In so doing, we chart our shifting from talking about intercultural communication as an element to be embedded into the language course, to doing intercultural communication, specifically through the process of co-creating the course materials.

The Impact of Language project was funded in 2017 by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) through the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF). It explicitly aimed to redress the high unemployment rate of Palestinian graduates in the Gaza Strip, while generating research about the dynamics of online intercultural collaboration and on language teaching/learning in and from a context of protracted crisis. The project was guided by a social-justice-through-education agenda (Freire, Citation1992) thus making this specific research project, and the ongoing partnership between the UofG and IUG, an instance of ‘academic activism’ (Askins, Citation2009).

The Gaza Strip (Palestine) is a tiny strip of land of 365 km2 home to two million Palestinians, which makes it one of the most populous areas in the world, with 5,203 people per km2 (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Citation2018). The blockade imposed by the Israeli government on the Strip limits the flow of goods, raw materials, and people, causing extremely difficult living conditions. In this challenging context, international collaborative projects offer opportunities to academics in the Gaza Strip to overcome isolation and to engage in knowledge exchanges and intercultural encounters that would not be possible otherwise. Online communication represents a way to bypass the virtually impassable borders of the Strip, and a means to enhance employment prospects.

The OAfP language course consists of 24 beginner-level lessons that are now taught online by young (mainly female) teachers based in the Gaza Strip to learners worldwide. The course is fully grounded in Palestinian everyday life and adopts a holistic approach to language learning. Central to the OAfP course are three of Martha Nussbaum's capabilities (Citation2006): the capability of ‘senses, imagination and thought’, the capability of ‘emotions’ and the capability of ‘affiliation’. The course, therefore, is inspired by the capabilities approach, and adopts this as an ethical framework that allows focus on teachers’ and learners’ wellbeing, interpreted as the potential of individuals to aspire to, and to conduct the life that they value (Sen, Citation2009). In the case of the Gaza Strip, this potential is powerfully influenced by the specific socio-historical and geographical context.

The project context

Part of the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPTs), the Gaza Strip is a narrow ribbon of land facing the Mediterranean Sea. Its coastline is 45 km long, while the width of the Strip measures between 6 km at its narrowest and 14 km at its widest. Home to two million Palestinians, the Strip borders with Egypt to the south, and to the north and east with Israel. For the past 13 years, Israel has imposed a blockadeFootnote1 on Gaza which has severely restricted the movement of people. The effects of the blockade, further aggravated by internal political divisions, have meant (and still mean) a virtual collapse of the Strip's economy (Winter, Citation2015; World Bank, Citation2018). Additional limitations to travel through the Southern border of the Strip imposed by Egypt severely curtail people's opportunities to escape unemployment and poverty by migrating to other countries. Recurrent bombings by the Israeli air force, as well as three large scale military operations in the past decade, have caused huge loss of civilian livesFootnote2, and the destruction of much of the Strip's infrastructure.

Tawil-Souri and Matar (Citation2016) describe the Gaza Strip as a ‘statistical impossibility’, since:

[…] more than two-thirds of the population is made up of refugees; 70% live in poverty; 20% live in ‘deep poverty’; just about everybody has to survive on humanitarian hand-outs; adult unemployment hovers around 50% give or take a few percentage points; 60% of the population is under the age of 18. This is the Gaza where on a good day there is not electricity ‘only’ 20 hours a day; where, before the latest Israeli military operation, in summer 2014, there was already a shortage of 70,000 homes; where 60% of the population suffers from food insecurity; where 95% of piped water is below international quality standards; where every child age 8 or [older] has already witnessed three massive wars. […] Gaza – the city and the Strip – today is hermetically-sealed: the flow of people, goods, as well as medicines, fuel, and electricity is tightly controlled by Israel, all the while subjected to various forms of military and political violence. As in any other place, Gaza's changes are dynamic. But the conditions imposed on the territory and the people that live in it are man-made. (p. 3)

Furthermore, people wishing to travel to Gaza are, at least in the U.K., strongly discouraged from doing so, as Home Office guidelines currently warns against all travel to the Gaza Strip, and institutional insurance does not cover travel to this part of the world. As a result of the isolation this creates, Gaza experiences ‘forced monoculturalism’ (Imperiale, Phipps, Al-Masri, & Fassetta, Citation2017) and the Strip’s academics and students are severely limited in their opportunities to travel to learn, expand their intercultural competence and further their academic, and professional development and intercultural awareness.

In this challenging context, online communication tools offer a way to bypass the physical immobility that the blockade imposes on academics and students in Higher Education institutions (Fassetta, Imperiale, Frimberger, Attia, & Al-Masri, Citation2017; Imperiale et al., Citation2017). We wish to stress that virtual movement cannot and should not be an acceptable substitute for the freedom to travel. However, online tools have allowed several collaborative projects between Higher Education Institutions in the Gaza Strip and their counterparts in a range of countries, and the project discussed in this article built directly on one such online collaboration.

The origins of the Impact of Language project

The Researching Multilingually at the Borders of Language, the Body, Law and the State (hereafter RM Borders) project was one of three Large Grants awarded by the U.K.’s Arts and Humanities Research Council under the ‘Translating Cultures’ theme. Part of RM Borders, the Teaching Arabic to Speakers of Other Languages case study was a collaboration with IUG to develop and deliver a training programme for teachers of Arabic as a foreign language. The training was tailored for online delivery and, concurrently, focussed on methodologies and tools for online language teaching. Its aim was to provide Arabic language teachers in the Gaza Strip with innovative online teaching skills that would increase their employment opportunities (Fassetta et al., Citation2017).

As part of the training programme, the Palestinian teachers were required to practice by teaching volunteer learners via Skype. Feedback gathered from the volunteer learners highlighted how, while the teacher’s approach was praised as creative and engaging, the materials used during the lessons had been somewhat disappointing. As the trainee teachers lacked access to a course grounded specifically in ‘Palestinian culture’Footnote3, they had resorted to adapting Arabic language courses that were originally developed in other Arabic-speaking countries (e.g. Saudi Arabia). In some cases, the teachers had also translated and adapted materials from English to Speakers of Other Languages courses. The volunteer learners identified the creation of materials grounded in and illustrative of Palestinian ways of life and identity as central to increasing motivation for potential students, and thus for increasing uptake of a course taught online from the Gaza Strip. From these considerations, the Impact of Language project proposal – to be developed collaboratively by the UofG and IUG – took shape.

The ‘Impact of Language’ project

As noted earlier, the importance of feeling a connection with Palestine had emerged from feedback by volunteer learners during the project. However, designing a language course fully grounded in Palestinian experiences, taught by teachers in Gaza and showing life in the Strip, was more than just a way to offer prospective language students an improved learning experience by engaging their emotions as well as their cognition (Kramsch, Citation2009). It was deliberately chosen as an instance of ‘academic activism’, a way ‘of doing research and thinking in ethically sensitive and socially transformative ways’ (Askins, Citation2009, p. 10). The project proposal clearly stated the aim of working with academics and teachers in the Gaza Strip to overcome the barriers imposed by the blockade, increase their chances for contact with the world outside the Strip, and their employment opportunities. This meant openly acknowledging the project team’s ethical concern about the situation in Gaza and recognising that there are political implications in all research and teaching, including in the apparently neutral terrain of language teaching (Kramsch, Citation2014). In addition, it aimed to generate research on interculturality in online settings in terms of intercultural pedagogy, but also with a focus on interculturality as research methodology and a way of working.

The project’s main objectives were to: (1) provide a unique, creative, contextually-grounded and appealing course that would attract potential learners to the Arabic Center; (2) build capacity for the Arabic Center to become a model for innovative, sustainable, engaging online language teaching/learning; (3) design and develop a holistic course that would engage emotions as well as cognition; (4) promote and disseminate the course through knowledge exchange events and via social media. These objectives were pursued through close collaborative work between team members based within the UNESCO Chair for Refugee Integration through Languages and the Arts (UofG, School of Education) and team members based at the Arabic Center at IUG. The OAfP language course for beginners, the main output of the collaboration, is now available on IUG’s Moodle site to fee-paying learners worldwide. The OAfP develops over 24 taught lessons divided into eight units, and all the lessons introduce vocabulary and structures with the aid of a short video. Each lesson lasts two hours, 90 min of which are taught online by a teacher based at IUG’s Arabic Center, while the remaining 30 min are for preparation and revision.

Designing the OAfP course: the capabilities approach

The OAfP course was guided by the capabilities approach, a normative framework to evaluate wellbeing, which takes into account individuals’ freedom to live the life they have reason to value (Sen, Citation2009) and to live a life in dignity and human flourishing (Nussbaum, Citation2006). Nussbaum (Citation2000, Citation2011) identifies a list of ten capabilities, which, she argues, constitute the threshold for ‘human dignity’. The capability approach is extensively used in human development, in social welfare and economy, and in education. However, in the field of language education it has so far received little attention, with the exception of Crosbie (Citation2014), Imperiale (Citation2017, Citation2018) and Imperiale et al. (Citation2017).

Adopting the capabilities approach as a framework for developing a language course meant aspiring to the holistic wellbeing of both language teachers and students, to nourish some of Nussbaum’s (Citation2000, Citation2011) central capabilities, the ones the course design team assessed to be most appropriate to a context of language education in/from the Gaza Strip. Thus, the course was designed with three of Nussbaum’s central capabilities at its core: the capability of ‘senses, imagination, and thought’, the capability of ‘emotions’; the capability of ‘affiliation’.

Summarising Nussbaum (Citation2011), the capability of ‘senses, imagination and thought’ refers to the opportunity to use one's senses; to imagine, think, and reason; to be able to use imagination and thought in connection with making, and with enjoying the process and results of one’s creation; to be free to express one’s mind for both political and artistic speech; and to be able to have pleasurable experiences. The capability of ‘emotions’, refers to connections to things and people outside ourselves, to love, to grieve, to experience longing, gratitude, and justified anger. Finally, the capability of ‘affiliation’ refers to the ability to live with others; to recognise and show concern for fellow human-beings; to engage in interactions; and to imagine the situation of another person. Alongside three of Nussbaum’s (Citation2000, Citation2011) central capabilities, the OAfP course development also engaged extensively with the ‘narrative imagination’, one of the three-part model Nussbaum (Citation2006) identified as crucial to the development of global citizenship through education. The narrative imagination refers to the use of language and the arts to navigate others’ cultural contexts and to put oneself in other people’ shoes, thus developing empathy and understanding.

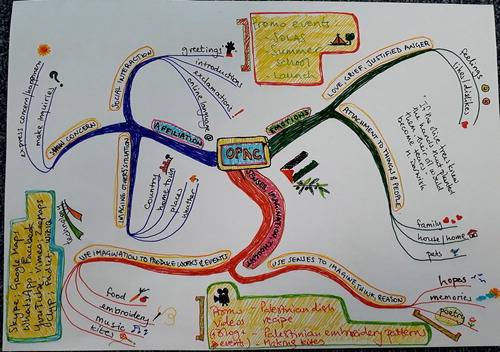

Thinking about ways to link these capabilities to language learning and weaving the narrative imagination throughout the course, while keeping learning materials embedded in Palestinian life, provided a compass for the development of the OAfP which helped the team to maintain a holistic perspective grounded not only in cognition but also emotions and values. On the basis of Nussbaum’s capabilities outlined above, the project team brainstormed ideas for the initial design of the Arabic language course. This resulted in the mind-map above, which was created and shared by the team in Glasgow during the early stages of the project, and to which the whole team returned regularly throughout the collaborative design and the development of the OAfP syllabus and materials ().

Sumud and Arabic language teaching

Palestinian language and culture are interwoven with the political and socio-economic situation of the Palestinian people, in particular the dispossession caused by the Nakba (Arabic for ‘catastrophe’) of 1948, when huge numbersFootnote4 of Palestinians were forced to leave their homes and villages to make space for the State of Israel (Khalidi, Citation1992), as well as with the trauma of war, socio-economic marginalisation and internal political conflicts. As remarked earlier, over three-quarters of the population of the Gaza Strip is made up of refugees (and their descendants) who were displaced during the Nakba and by the violence of the decades that followed.

However, Palestinian language and culture are also characterised by Sumud, a concept that is at the very heart of ‘Palestinianness’. As Marie, Hannigan, and Jones (Citation2018, p. 29) note, Sumud is ‘the art of living to survive and thrive in the homeland in spite of hardship and under occupation practices.’ In other words, Sumud is the social and cultural manifestation of individual resilience when it becomes part of a nations’ identity, rooted in a strong attachment to the land and its products. A concept peculiar to Palestinian people, Sumud is expressed through poetry, songs, music and art, as well as linked to food connected to the land (e.g. thyme, olive oil, bread). The past and present of the Nakba, and the collective resilience of Sumud, are all important elements of Palestinian identity and weaving these elements into the OAfP course was essential, the team agreed, to contribute to a process of language teaching and learning that is both discourse-based and historically grounded (Kramsch, Citation2011).

To ensure that the course was embedded in Palestinian everyday life, it was decided from the very start of the project that the whole process of designing and developing the materials had to be co-constructed through a close collaboration between the ‘Glasgow team’ (the P.I., a researcher and the project administrator) and the ‘Gaza team’ (the Co-I., four course developers and a local project coordinator). The collaboration was carried out through online and mobile communication tools, while the course itself was tailored for Computer Assisted Languge Learning (CALL), and technology therefore constituted a crucial dimension of the project.

The technology

As noted in the introductory section, the use of digital technologies is vital to allow Gazan language teachers to teach Arabic as a foreign languge to international learners despite the challenges imposed by the blockade, and the team made extensive use of Skype, WhatsApp, Moodle, Facebook and emails for the project. Since electricity is often only available for four hours each day, public places and individuals (who can afford it) have invested in private or shared generators and/or solar panels to maintain reliable Internet connection. While the fact that Internet and mobile networks are run by Israeli providers means that Gazans do not have full control over their digital setup (Aouragh, Citation2016), the infrastructure that has been developed allows good Internet speed and a generally stable connection, thus making online work a feasible option.

Over the past 20 years, computer mediated communication has been increasingly popular for telecollaboration and as a tool for language teaching (Chun, Smith, & Kern, Citation2016). However, the distortions, interruptions, delays and limitations to physical proximity of the online environment can result in greater focus on the surface features of language (Kramsch, Citation2014), and risk leaving out the affective aspects of languge learning. Despite potential technical difficulties, the team’s emphasis on the capabilities approach as a core element of the learning process, and the wish to create a narrative that would help learners understand life in the Gaza Strip, ensured that history, memory and emotions remained central to the course (the Douglas Fir Group, Citation2016; Levine & Phipps, Citation2011; Swain, Citation2013). This was pursued through the narrative of the course videos, which would (re)present life in Gaza in its practical/ authentic, everyday interactions as well as in its historical dimension and emotional resonance.

The storyline of the videos

Nussbaum (Citation2006, Citation2008) stresses the essential role of ‘narrative imagination’ in order to develop intercultural understanding of lives that are grounded in unfamiliar worldviews, priorities, and practices. By telling stories, as Downey and Clandinin (Citation2010) note, we ‘create coherence through time, between the personal and social, and across situations’ (p. 387), and the 24 lessons that comprise the OAfP course have at their heart a narrative of Gaza, one that came together to show the country and its people as our Palestinian colleagues wished them to be known.

The videos tell the story of Sara and Adam, a brother and sister born in Italy of Palestinian parents. We follow them as Sara first meets Anas – an Arabic language teacher in the Gaza Strip – via Skype and as the siblings organise their trip there to improve their Arabic and learn more about their parents’ country. Once in Gaza, Sara and Adam are shown around by Anas, who introduces them to various places and customs. We see Sara and Adam drinking tea with mint and with sage; eating Palestinian food and sweets; visiting the ‘House of Sumud’ in Gaza to be introduced to the symbolic dimension of the ‘key of return’Footnote5, and to the art of Palestinian embroidery. The siblings also visit a Palestinian home and are introduced to Anas’ family, and they go to the University library. While browsing an atlas, they are told about Jerusalem, the Holy City, and about the fact that, because of the blockade, it is extremely hard for Anas to travel to other parts of Palestine.

In the short videos, the capability of ‘senses imagination and thought’ is fostered through open acknowledgement of challenging political themes, but also of pleasurable experiences. The capability of ‘emotions’ comes across through the importance of objects and people outside the self, but also through the expression of love, longing, and ‘justified anger’ (Nussbaum, Citation2006). The capability of ‘affiliation’ is advanced through the ability to engage with others, to show concern for fellow human-beings, and to imagine the situation of another person.

As we reflect on the team’s focus on the capability approach to ‘anchor’ the storyline, we want to clarify that we cannot claim that the OAfP course can – or will – develop these capabilities in depth, nor that it may substantially redress the many challenges, practical and emotional, experienced by the Palestinian colleagues. Nevertheless, maintaining the capabilities as a focus, while developing the story for the videos, pushed the team, on both sides of the screen, to ensure that Palestinian subjectivity and historicity were constantly present in the OAfP’s simple storyline.

It was the team’s intention that the narrative of the video would act as a stimulus to engage students in conversation, developing cultural understanding as a discursive practice (Freadman, Citation2014) that would be central to the learning experience. Stimulating students’ and teachers’ engagement in intercultural exchange was, therefore, one of the explicit objectives pursued by the team while designing the course. However, as we started inquiring more systematically about the narratives that were created, we realised that the collaborative writing of the video storyline required a similar process of intercultural understanding, adjustment and engagement by team members. The story we co-created in fact stood in relation – sometimes in tension – to many other stories (Downey & Clandinin, Citation2010) on both sides of the screen, including narratives of who we are, how we wish to see ourselves and how we wish to be seen.

Negotiating the storyline: reflections from Glasgow

As Freadman (Citation2014) notes, ‘there is a certain humility required for the enterprise of intercultural understanding: one's own voice may, as in music, harmonise in any cultural environment only on condition of a well-attuned ear’ (p. 384). In this section, we reflect on the process of ‘attuning the ear’, on the effort it took for this to happen within the project team, and on a few challenging conversations. A large part of the collaborative work between the team at UofG and IUG focussed on developing the storyline and then the script for the course videos, and many conversations and adjustments were required to ensure that the narrative, setting, props and dialogues reflected Gazan daily life as experienced by our colleagues, while also being adjusted to the linguistic repertoire of a beginner-level language course.

As discussed earlier, language teaching and learning were intended as a process to enable teachers and students to express and exchange emotions and experiences, using some of Nussbaum’s (Citation2011) central human capabilities as an anchor to develop the course language content and storyline. This further ensured that cultural and affective narratives were an integral part of the course and of language learning (Kramsch, Citation2009). Reflecting back on the experience, however, we can see that applying these principles to the OAfP meant first of all using them in the team’s communications. By being part of one project – albeit in two teams located in two different countries and only able to meet virtually – we were modelling the intercultural elements of the course in our working interactions: engaging in frank conversations, taking stock of emotions, and ‘attuning our ear’ to our partners’ narratives of themselves and of their context.

While we were not aware of this at the time, we can now see how each of the 24 short videos introducing the course lessons was the result of several hours of discussion and reflection, reciprocal assumptions confronted, mutual expectations challenged (or validated) in order to collaboratively shape the story, multilingually and interculturally. In the original screenplay, which the Glasgow team members started, Sara, the protagonist, was to travel to Gaza on her own and meet her teacher Anas there. However, the Gaza team members tactfully but firmly pointed out that it would not have been appropriate for Sara to go alone with a male teacher to the market, to restaurants and to his house. The Gaza context, they told us, is rather conservative, and depicting a woman travelling alone would not have been culturally appropriate, nor an accurate reflection of reality. To remedy this, the Palestinian team members suggested the inclusion of a third character Adam, Sara’s brother. This development raised some concerns among the Glasgow team, keen to depict for the course a female character who, in defiance of widespread stereotypes of Muslim women, would be independent and self-reliant. However, it also demonstrated that the Gaza team members were prepared to challenge their Glasgow colleagues, to assert their own particular narrative as central to the story.

A similar event happened when the Glasgow team members realised that changes to the script made in Gaza meant that Sara had been left out of three videos. At first, this created anxieties in the Glasgow team, who worried that the female character had been seen as less central than her male companions and side-lined, revealing Western anxieties around the marginalisation of women in a Muslim context. However, as soon as concerns about this were voiced to the partners in Gaza, elimination of Sara was acknowledged as an oversight, and the storyline was quickly changed again to reintroduce her. As Butler (Citation2008) notes, Western narratives of progress often see the unfolding of time:

as one story, developing unilinearly […] rather [than] as a convergence of histories that have not always been thought together, and whose convergence or lack thereof presents a set of quandaries that might be said to be definitive of our time. (p. 6)

The lengthy reflections and conversations required to negotiate the video storyline led to the realisation that the team’s collaboration needed to happen within a ‘symbolic place that is by no means unitary, stable, permanent and homogeneous [but rather] multiple, always subject to change and to the tensions and even conflicts that come from being “in between”’ (Kramsch, Citation2009, p. 238). Co-creating the story of the course represented an opportunity for nurturing the capabilities that were at the core of the OAfP course, recognising that effective intercultural negotiation and communication are not always easy. As Downey and Clandinin (Citation2010, p. 385) poignantly note: ‘learning begins only when certainty ends’, and as an intercultural team, we all learned a lot in the process of letting go of our assumptions and of allowing a space for messiness and muddles, exactly as we had planned that the design of the OAfP course would lead future language students to do.

The next section illustrates another way in which the development of the OAfP storyline went beyond a depiction of geographical settings or cultural practices in the Gaza Strip. Through the shooting of the videos, the Gaza team members took the opportunity to challenge established narratives imposed by international media and public discourses, using the filming as a way to put forward their own narrative of Gaza and of life in the Strip.

Negotiating the storyline: reflections from Gaza

As Freadman (Citation2014) argues, the formation of cultural identities may need to come to terms with painful histories. In the case of the Gaza Strip, this also includes a painful present, and the long blockade of the Strip and the everyday challenges this entails for the people of Gaza – including its language teachers – could not be ignored in the OAfP course. While the role of a language course and of language teachers is not to impose a personal view on events, ‘what one chooses to talk about or not to talk about, whether it be politics, sex, or religion, is a political act’ (Kramsch, Citation2014, p. 307). The choice about what to include in a course is always a political one, and one that all course developers make when deciding what to show and what to obscure about the socio-historical context(s) of a particular language. While developing the OAfP’s material, the team felt that it was important for prospective learners to be encouraged to reflect on their understanding of the Palestinian and Gazan context, and for teachers to have the opportunity ‘to model for their students through narratives of personal experience the deep emotions that memories and beliefs generate in those who hold them’ (Kramsch, Citation2014, p. 307).

As noted earlier, co-writing a storyline and the script for the OAfP videos meant that the Gaza team members were able to shape the narrative to ensure that it would reflect their lived experience of the Gaza Strip, even with the necessary linguistic limitations of a beginners’ course. Moreover, as the videos were shot in and around Gaza city, the IUG team members were able to visually represent the Strip as they wished it to be known, challenging the ‘othering’ representations of Palestine (Said, Citation1992) that are common in Western media. As one of the Gaza colleague notes, creating the OAfP visuals gave them the opportunity:

to reflect [on] life in Gaza rather than death, […] to change the stereotypes about Gaza that mainstream media plant in people's minds. (JM, course developer, IUG)

Being able to put forward a narrative of the Gaza Strip that challenges the one depicted by global media meant, for the Gaza team members, being able to show that everyday life in Gaza continues to hold happiness, beauty, hope and pleasure despite the continued blockade. As one of the IUG colleagues notes:

I always try to reflect [on] the beauty and happiness of Gaza, the kindness of people here and [the] simplicity of life, even [in] my Instagram account, I insist to name it “Happy Gaza” because we really breathe hope to keep alive. (LA, course developer, IUG)

Through teaching Arabic with using videos and a chosen scenario, we wanted to travel with the learner […] to the Palestinian landmarks, especially Gaza, so that [s]he would know us more closely and know more about our culture. In this way, the learner knows that Gaza in its small size has a big heart and ancient culture who can welcome all people happily besides learning Arabic. (HA, project coordinator, IUG)

Conclusion

The Impact of Language research project resulted in the development of an online Arabic language course for beginners, the OAfP. The design of the course was guided by three of Nussbaum’s (Citation2006) central capabilities, and the project explored the extent to which the capability approach can be a useful framework for the inclusion of intercultural understanding, relationship-building and emotions as an integral part of language learning. We pursued this primarily through the storyline written for the videos that introduce each of the course lesson, which constitute the ‘narrative hook’, that is: ‘the story whose function is to stimulate the students’ interest, thus engaging them in the learning that makes sense of it’ (Freadman, Citation2014, p. 380).

This article explored some of the most ethically challenging and enriching moments in the teams’ collaborative drafting of the storyline, as we all learnt to work together, to confront assumptions, and to challenge narratives. Engaging with others, as Clandinin (Citation2006, p. 47) notes, means ‘walking in the midst of stories’ and learning to recognise that all situations are nested within a complex web of other situations, each with its own narrative. As the team worked together to create the video storylines, narratives of ‘the self’ and of ‘the other’ had to be acknowledged and ‘moved out of’ (Downey & Clandinin, Citation2010) to allow for new and alternative stories to emerge.

Reflecting on the ways in which narratives of ‘the self’ and ‘the other’ were challenged and altered in the process of developing the course videos highlights the importance of having shared aims and established ways of working in order for a complex online collaboration to develop successfully and with little friction. Perhaps more importantly, the instances of divergence that arose prove the fundamental role of trust in international collaborative projects (Fassetta & Imperiale, Citation2018). Reciprocal trust means that issues can be discussed openly and safely, as was the case of the Glasgow team's concern over what was perceived as biased treatment of the female character in the course videos. Feeling able to express concerns to colleagues in Gaza ensured that they were addressed, that a consensus could be reached, and that greater reciprocal understanding was gained. This meant, of course, agreeing to compromises on both sides of the computer screen, but being willing to do so in the understanding that this is a necessary part of effective international and intercultural collaborations.

Since it was launched more than a year ago, the OAfP has been taught to twenty international students, while increasingly attracting attention and inquiries from all over the world. The Arabic Center has also been contacted by a number of international institutions (in the Maldives, Germany, Belgium, for example), which has helped improve IUG's profile as an online Arabic language provider. As well as offering job opportunities for language graduates and ways to expand intercultural awareness on both sides of the computer screen, the attention the project attracted also increases the potential for academic collaborations between IUG and other higher education institutions worldwide, and the growth of knowledge and skills this entails.

Phipps and Barnett (Citation2007) define as ‘academic hospitality’ the many practices that relate to the hosting of colleagues within each other’s institutions, and to the collective rituals which pave the way for the exchange of knowledge and understanding, for the building of new theoretical and empirical insights, and sometimes also for new friendships. Choosing to collaborate online with colleagues in Gaza to offer ‘virtual academic hospitality’ has been a way to ensure that they remain part of the global academic conversation, an example of ‘academic activism’ exercised by engaging in research that aims to generate social change.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge our colleagues at IUG’s Arabic Center for being the best colleagues one could hope for.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Giovanna Fassetta is a Lecturer in Intercultural Literacies and Languages in Education in the School of Education, University of Glasgow. Giovanna is part of the UNESCO Chair for Refugee Integration through Languages and the Arts (UNESCO-RILA) team and of Glasgow Refugee Asylum and Migration (GRAMNet) Executive.

Maria Grazia Imperiale is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in the School of Education at the University of Glasgow. She holds a PhD in Language Education from the University of Glasgow, and Master’s Degree (Hons) in Applied Linguistics from the University of Foreigners of Siena (Italy).

Esa Aldegheri is a Doctoral Researcher and a Research Associate at the University of Glasgow’s School of Education. Her ESRC-funded PhD investigates how narrative exchange and community mapping can facilitate encounter and integration in the context of forced migration in Scotland and Italy.

Nazmi Al-Masri is an Associate Professor of TEFL and curriculum development at the Islamic University of Gaza, Palestine. He is a partner and local coordinator on several research projects with universities in the U.K., Germany, Finland and Norway.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Throughout this paper we will refer to the restrictions of movement imposed on the Gaza Strip by Israel as ‘blockade’ in accordance with The United Nation Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (see: https://www.ochaopt.org/theme/gaza-blockade. Last accessed: 27/09/2018).

2 In 2008, during operation ‘Cast Led’, an estimated 1,300 people, many of them civilians, died. In 2012, during operation ‘Pillar of Defence’, at least 167 Palestinians were killed. In 2014, during operation ‘Protective Edge’, authorities reported that over 2,200 people were killed and many more injured (see: https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/20436092. Last accessed: 8/02/2019).

3 By using the term ‘Palestinian culture’ we do not wish to espouse an essentialist notion of culture. Rather, we work with Said’s (Citation1986) view that, although multifaceted, non-comprehensive and difficult to represent, the claiming of a shared identity/culture is central to Palestinian people to affirm their resistance and their existence, as their physical presence on the land has been denied, leading to their displacement.

4 Approximately 5 million Palestinian refugees qualify for support by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNWRA) for Palestine refugees in the Near East (see: https://www.unrwa.org/palestine-refugees. Last accessed: 25/09/2019).

5 Many Palestinian refugees worldwide still hold on to the keys of their original homes (or the homes of their forebears), and the ‘key of return’ is central to the Palestinian people.

References

- Aouragh, M. (2016). Revolutionary manoeuvrings: Palestinian activism between cybercide, and cyber Intifada. In L. Jayyusi, & A. S. Roald (Eds.), Media and political contestation in the contemporary Arab world. A decade of change (pp. 129–160). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Askins, K. (2009). ‘That’s just what I do’: Placing emotion in academic activism. Emotion, Space and Society, 2(1), 4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2009.03.005

- Bangstad, S. (2011). Saba Mahmood and anthropological feminism after virtue. Theory, Culture & Society, 28(3), 28–54. doi: 10.1177/0263276410396914

- Butler, J. (2008). Sexual politics, torture, and secular time. The British Journal of Sociology, 59(1), 1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00176.x

- Chun, D., Smith, B., & Kern, R. (2016). Technology in language use, language teaching, and language learning. The Modern Language Journal, 100, 64–80. doi: 10.1111/modl.12302

- Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative inquiry: A method for studying lived experience. Research Studies in Music Education, 27, 44–54. doi: 10.1177/1321103X060270010301

- Clandinin, D. J., Murphy, M. S., Huber, J., & Orr, A. M. (2009). Negotiating narrative inquiries: Living in a tension-filled midst. The Journal of Educational Research, 103(2), 81–90. doi: 10.1080/00220670903323404

- Crosbie, V. (2014). Capabilities for intercultural dialogue. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14(1), 91–107. doi: 10.1080/14708477.2013.866126

- Douglas Fir Group. (2016). A Transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal, 100, 19–47. doi: 10.1111/modl.12301

- Downey, C. A., & Clandinin, D. J. (2010). Narrative inquiry as reflective practice: Tensions and possibilities. In N. Lyons (Ed.), Handbook of reflection and reflective inquiry: Mapping a way of knowing for professional reflective inquiry (pp. 383–397). London: Springer.

- Fassetta, G., & Imperiale, M. G. (2018). Indigenous engagement, research partnerships, and knowledge mobilisation. ESRC/AHRC GCRF Indigenous Engagement programme. Retrieved from https://www.ukri.org/news/esrc-ahrc-gcrf-indigenous-engagement-programme/related-content/fassetta-imperiale/

- Fassetta, G., Imperiale, M. G., Frimberger, K., Attia, M., & Al-Masri, N. (2017). Online teacher training in a context of forced immobility: The case of Gaza, Palestine. European Education, 49(2–3), 133–150. doi: 10.1080/10564934.2017.1315538

- Feldman, A. (2016). Fragmented memory in a global age: The place of storytelling in modern language curricula. The Modern Language Journal, 98(1), 373–385.

- Freadman, A. (2014). Fragmented memory in a global age: The place of storytelling in modern language curricula. The Modern Language Journal, 98(1), 373–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2014.12067.x

- Freire, P. (1992). Pedagogy of hope. Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Bloomsbury.

- Imperiale, M. G. (2017). A capability approach to language education in the Gaza Strip: ‘To plant hope in a land of despair’. Critical Multilingualism Studies, 5(1), 37–58.

- Imperiale, M. G. (2018). Developing language education in the Gaza Strip: Pedagogies of capability and resistance (Unpublished PhD thesis).

- Imperiale, M. G., Phipps, A., Al-Masri, N., & Fassetta, G. (2017). Pedagogies of hope and resistance: English language education in the context of the Gaza Strip, Palestine. In E. J. Erling (Ed.), English across the Fracture lines (pp. 31–38). London: British Council.

- Khalidi, R. I. (1992). Observations on the right of return. Journal of Palestine Studies, 21(2), 29–40. doi: 10.2307/2537217

- Kramsch, C. (2009). Third culture and language education. In V. Cook, & L. Wei (Eds.), Contemporary applied linguistics (pp. 233–254). London: Continuum.

- Kramsch, C. (2011). The symbolic dimensions of the intercultural. Language Teaching, 44(3), 354–367. doi: 10.1017/S0261444810000431

- Kramsch, C. (2014). Teaching foreign languages in an era of globalization: Introduction. The Modern Language Journal, 98(2), 296–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2014.12057.x

- Levine, H., & Phipps, A. (Eds.). (2011). Critical and intercultural theory and language pedagogy. Boston: Cengage Heinle.

- Marie, M., Hannigan, B., & Jones, A. (2018). Social ecology of resilience and Sumud of Palestinians. Health, 22(1), 20–35. doi: 10.1177/1363459316677624

- Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. (2006). Frontiers of justice: Disability, nationality, species membership. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. (2008). Democratic citizenship and the narrative imagination. Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, 107(1), 143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7984.2008.00138.x

- Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating capabilities. The human development approach. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2018). On the occasion of the International Population Day 11/7/2018. Retrieved from http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/post.aspx?lang=en&ItemID=3183

- Phipps, A., & Barnett, R. (2007). Academic hospitality. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 6(3), 237–254. doi: 10.1177/1474022207080829

- Said, E. (1986). After the last sky. London: Faber and Faber Limited.

- Said, E. (1992). The question of Palestine. New York: Vintage Books.

- Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Swain, M. (2013). The inseparability of cognition and emotion in second language learning. Language Teaching, 46(2), 195–207. doi: 10.1017/S0261444811000486

- Syed, J., & Ali, F. (2011). The white woman’s Burden: From colonial civilisation to third world development. Third World Quarterly, 32(2), 349–365. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2011.560473

- Tawil-Souri, H., & Matar, D. (2016). Gaza as metaphor. London: Hurst & Company.

- UN Conference on Trade and Development. (2017). Assistance to the Palestinian people: Developments in the economy of the occupied Palestinian territory. Geneva: United Nations. Retrieved from https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/tdb64d4_embargoed_en.pdf

- Winter, Y. (2015). The siege of Gaza: Spatial violence, humanitarian strategies, and the biopolitics of punishment. Constellations, 23(2), 308–319. doi: 10.1111/1467-8675.12185

- World Bank. (2018). Cash-Strapped Gaza and an economy in collapse put Palestinian basic needs. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/09/25/cash-strapped-gaza-and-an-economy-in-collapse-put-palestinian-basic-needs-at-risk