ABSTRACT

This study analyses the transcultural meaning-making and literacies that arise during the amateur translation of a fanfiction novel from Russian to English. We applied digital ethnography to make observations of the translation process and interviews with the participants. Transcultural meaning-making was identified during their discussions on how to adapt a Russian fanfiction novel for a global English-speaking readership. During the discussions the participants creatively mixed different linguistic and cultural resources. They also positioned themselves as mediators between two readerships, which pushed them to reflect on literary and philosophical traditions of the Russian and English-speaking cultures and engage in transcultural literacies.

В данной статье мы проводим анализ транскультурной коммуникации и грамотности в контексте фэндома на примере любительского перевода фанфика с русского на английский. Основываясь на методологии цифровой этнографии, мы провели серию наблюдений за процессом перевода и интервью с ключевыми участниками команды. Транскультурная коммуникация была выявлена в ходе дискуссий участников о том, как следует адаптировать русский фанфик для глобальной англоязычной аудитории. В ходе этих дискуссий участники перевода творчески смешивали различные языковые и культурные коды, а также позиционировали себя в качестве посредников между двумя разными аудиториями, что подтолкнуло их к критическому обсуждению культурных различий русскоязычной и англоязычной аудиторий.

Introduction

Digital technology has made intercultural contacts a daily activity for many people in the world. As a result, the globalization of cultural flows and the various ways that people appropriate these cultural flows have become hot topics for investigation, and the prefix ‘trans-’ can now be seen in terms like translocalities, transnational, translanguaging and transculturing, underlying the fluidity and mix of cultures, languages and localities in the digital environment (Baker & Sangiamchit, Citation2019; Black, Citation2008; Kytölä, Citation2016; Sultana & Dovchin, Citation2016; Vallejo & Dooly, Citation2019).

These transcultural meaning-making practices frequently occur in the context of fandoms (Black, Citation2006; Kytölä, Citation2016; Sauro, Citation2017; Thorne, Citation2008), which are online spaces made up of deeply engaged consumers with a shared interest in specific popular culture products (Jenkins, Citation2006). Fandom frequently unites people from different countries, who can engage in practices of cultural remix to produce fanfiction,Footnote1 fanart, fandubbing,Footnote2 etc. These practices can lead to informal learning, cross-border affiliation and the development of transcultural digital literacies (Black, Citation2008; Kim, Citation2016).

Drawing on Kim (Citation2016), we use the term transcultural literacies to describe a fluid cultural identification across boundaries and states within the realm of multimodal digital communication. Transcultural literacies can bring learners to reflect on cultural differences and reconstruct their identities by affiliating themselves with different cultural entities (Black, Citation2008; Kim, Citation2016; Zaidi & Rowsell, Citation2017). Though the field of transcultural digital practices is still relatively underexplored, the nature of transcultural meaning-making in online out-of-school environments is potentially of great interest to those involved with developing and implementing modern multicultural educational programs (Darvin & Norton, Citation2017; Kim, Citation2016).

The current study is intended to show how a digital practice can be enmeshed in different modalities, cultural flows and identities in the context of a brony fandom. ‘Bronies’ (‘brother’ + ‘pony’) are the male fans of a North American animated cartoon called My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic (henceforth MLP:FiM) which premiered on television in 2010 and ran until 2019. Though the core of the fandom generated by this cartoon is in the United States, there exist several local fandoms, which gather on specific digital platforms, speaking either a local language or a lingua franca. The brony fandom of interest here consists of fans from various post-Soviet republics who create and share animations, videos, fanfiction and fanart on different digital platforms. All of this is produced in Russian, making it in some cases unavailable for a global public.

Moreover, the current case study is situated in a variety of different cultural contexts and localities as we analyse the fan translation of the fanfiction novel based on the North American animated cartoon but written in Russian. The fan translators—from Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia and Poland—translate this text from Russian into English, while using Russian as their lingua franca. We argue that this translation activity of this sort can open up opportunities for the development of transcultural literacies.

Transcultural communication and translanguaging in a fandom

There is a growing body of research in sociolinguistics which connects popular culture with transculturality or translocality (Hepp, Citation2009; Kytölä, Citation2016; Valero-Porras, Citation2018), starting with the work of Pennycook (Citation2007), who coined the term transcultural flows while analysing the relationship between the hip-hop culture and English language appropriation. For Pennycook (Citation2007), the term transcultural flows refers to not only the global movement of cultural flows but also the unique way in which each culture appropriates these global flows in different communities all over the world. Baker and Sangiamchit (Citation2019) have developed this idea claiming that during online interactions users can appropriate a variety of global cultural references, which leads to the blurring of the borders between different cultures and languages. The authors use the term transcultural communication to describe the movement of texts and images across cultural and linguistic boundaries. During this transcultural communication, it is natural for translanguaging to occur, this term being understood as the dynamic use of the full linguistic repertory in interaction (Baker & Sangiamchit, Citation2019; Jones, Citation2019; Vallejo & Dooly, Citation2020). We hold that the notion of transcultural communication provides the ideal framework for analysing online interaction that jumps back and forth across linguistic and cultural boundaries.

The new literacy studies and transcultural literacies in a fandom

The new literacy studies is a theoretical framework frequently used in fan studies focused on language learning (Aliagas, Citation2017; Gee & Hayes, Citation2012; Shafirova et al., Citation2020; Vazquez-Calvo, Citation2018; Vazquez-Calvo et al., Citation2020; Zhang & Cassany, Citation2016, Citation2019). This framework describes reading and writing as social practices engraved in the coordinates of people’s daily routines. As these routines have migrated to the Internet, people have started to develop new abilities and skills, such as online teamwork or the use of multimodal resources. The main feature of the developing new literacies is that reading and writing on Web 2.0 has a social core, frequently developed in online communities, which makes it more collaborative, participative and distributive (Lankshear & Knobel, Citation2006).

Although some of the characteristics of transculturality in fandoms have been discussed previously (Black, Citation2008; Lam, Citation2006; Thorne, Citation2008; Thorne et al., Citation2009), the main focus of the new literacy studies has been on the collaborative and social dimensions of literacy practices. Nevertheless, more recently Kim (Citation2016) emphasized the importance of transcultural fan practices by adding the cultural dimension to new literacies and using the term transcultural digital literacies. With this idea, she followed Kostogriz and Tsolidis (Citation2008), who defined transcultural literacies as literacies that enable people to communicate across cultural borders while creating a third space beyond the dichotomy of ‘us’ and ‘them’ in the context of the Greek diaspora in Australia (Similarly, in Ntelioglou (Citation2017) the concept of transcultural literacies was used in cosmopolitan, diverse classrooms). Kim (Citation2016) took this term outside the diasporic context to argue that the collaborative and participative practices of young people communicating over the Internet could develop meaning-making and self-positioning relative to different cultural products and communities from all over the world. According to Kim (Citation2016, p. 205),

The practice of transcultural digital literacies is predicated on possibilities of new paths and combinations for cross-border connections and self-representations. This process is active not only in forging the online itinerary but also in the direct communication that occurs with other people from around the world.

In order to analyse transcultural literacies in the fan-translator community under study here, we formulated the following two research questions: (a) What type of negotiations do fan translators engage in when discussing cultural elements of the novel? and (b) How do fan translators engage in transcultural literacies?

Context

The brony fandom

Starting in 2011, the brony phenomenon has attracted considerable attention in the media, with commentators wondering how it was that men could be interested in a show aimed at young girls. Indeed, most of the research on brony fandom has centred around gender focusing on how bronies can challenge stereotypes about hegemonic masculinity (Hautakangas, Citation2015; Lehtonen, Citation2017; Valiente & Rasmusson, Citation2015). For instance, in the Finnish brony fandom, bronies ‘incorporated new elements’ into the traditional conception of masculinity (Hautakangas, Citation2015, p. 115), thus developing new gender identities (Lehtonen, Citation2017). Nonetheless, studies on brony fandom from literacy or transcultural perspectives are noticeably lacking (Shafirova & Cassany, Citation2019). This study hopes to help fill this gap by being one of the first to explore fan translation in the brony fandom.

The fanfiction novel

The Russian version of the fanfiction novel (B.T.) around which this case study revolves was written by A. in 2014 and published at ponyfiction.org for an adult readership. It is over 130,000 words in length and has received more than 1,000 comments. Readers have given it a five out of five rating and some 500 people have tagged this work as a favourite,Footnote3 making it a highly popular work in the fanfiction genre.

The fanfiction novel takes place in a far-away future in which biological engineering has advanced to the point where humans can create synthetic creatures based on cartoon characters, among them ponies. These creatures are living and breathing beings each with its own set of characteristics and personality traits. Nevertheless, the human population uses them as toys, slaves or sex workers. In this context, they essentially become commodities. The main character of the story, a human named Victor, becomes interested in the MLP:FiM show and buys a synthetic pony from it called Lyra. Lyra eventually runs away and faces all the terrors and injustices of the modern world. The resulting work of fiction is thus a dystopian novel covering such topics as freedom, slavery, capitalism and economic inequality while retaining the main idea of MLP:FiM, the value of friendship, as its leitmotif.

The action takes place in the gigantic global ‘City’ without further territorial specification. The names of the characters (such as Steven) suggest that it takes place in a somewhat Western reality; meanwhile, the main reference to Russia consists of the fact that the main character’s grandfather lives in Siberia.

The translation team

The team entrusted with translating B.T. into English consisted of four members, Bolk, Nork, Vic and Dan, all MLP:FiM fans and participants in a Russian-speaking brony fandom, with the main platform at https://tabun.everypony.ru/. Three of them were in their early 20s during the period when our data were collected, with only Nork, the leader of the team, in his mid-thirties. Living in Belarus, Ukraine, Estonia and Poland, they mainly communicated with each other using Russian as their lingua franca. None of the participants were professional translators but came from a variety of professional backgrounds, with Nork being a graphic designer, Vic a web developer. Dan a systems developer and Bolk working in the support service of an IT company.

For Bolk, the translation process was his hobby and his passion; he was the most experienced translator and was simultaneously participating in various translation projects within the fandom including the translation of scientific articles and board games, and also fandubbing. With less experience, Nork and Vic were hoping to improve their mastery of English through translating Russian into English. Dan, the fourth member of the team, was the original editor of the Russian version of the fanfiction novel; hence, he participated in the translation representing the original author of the fanfiction novel. From the outset, the team had considerable leeway in their translation as long as they did not stray too far from the original sense of the text, with Dan acting on behalf of the author to ensure that this was the case. Bolk and Nork identified as devoted brony fans, while Nork and Dan supported the brony fans and brony culture but did not identify as bronies per se. Nevertheless, all the participants shared one main objective, which was to present the Russian fanfiction novel to an international adult readership, thereby connecting the Russian-speaking fandom with their international counterparts. They therefore aimed to create a product of the highest possible quality.

The process of translation and adaptation of the novel

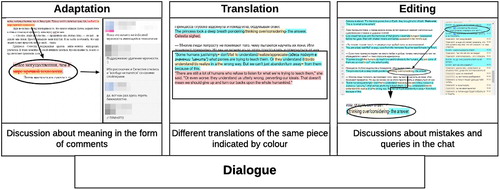

The translation process of the fanfiction novel began in 2016 and proceeded chapter by chapter with all members of the translation team working in close collaboration. The translation was carried out mainly on two digital writing platforms, Google Docs and Etherpad.Footnote4 Afterward, every chapter was published on the fanfiction repository FimFiction. The process of translation was divided into three main phases, as illustrated in below: adaptation of the Russian text for the international audience, translation and editing. During the first phase, each participant read the original text of the chapter in Russian and made comments on a shared Google Document concerning the adaptations they thought would be appropriate. These comments were frequently organized into discussions concerning cultural and linguistic differences between the Russian- and English-speaking worlds. During the second phase, working on the Etherpad platform, participants translated the parts of the chapter they had chosen, with each translator’s work distinguished by a particular colour highlighting. During the editing phase, the participants corrected and discussed all the translations until they reached consensus about the best translation for each paragraph. Finally, the entire translation was turned over to a native speaker for proofreading. In the present paper we will be primarily concerned with the first of these three phases, the adaptation phase.

Figure 1. Structure of the translation workflow (Shafirova & Kumpulainen, Citation20XX).

Materials and methods

Digital ethnography is a popular framework for research on online literacies (Black, Citation2006; Lam, Citation2006; Lee, Citation2016; Vazquez-Calvo, Citation2018) and was the methodological framework applied here. Digital ethnography applies traditional ethnographic methods, such as observation and interviews, to the digital realm while taking into account the peculiarities of the digital media (Markham, Citation2017). We also hold our design as an in-depth case study of the fan translation team. Our main field site of observation was a network of digital platforms including Google Docs and Etherpad (Burrell, Citation2009). The main observations were made by the first author, who first contacted the members of this fan translating community and then followed the individual participants online, even participating in the translation of one chapter of the novel as an ‘active observer’ (DeWalt & DeWalt, Citation2011).Footnote5 The bulk of her interactive involvement consisted of written chat discussions with participants on Google Docs during the adaptation phase and on Etherpad during the translation and editing phases and written interactions over Skype. Data gathering consisted of making screenshots and taking field notes that focused on the participants’ discussions among themselves and her own perceptions of the translation process. The fieldwork of the study lasted from June 2017 to February 2018.

Moreover, five semi-structured interviews were conducted via Skype. The first exploratory interview was made previous to the observation process with Nork and Bolk, who answered general questions about their motivation, the phases of the translation process and their perceived level of English. Afterward, a follow-up interview with Bolk was conducted which centred on his participation in the project, his feelings about collaborative work, his other fan practices and his engagement in fan translation. Finally, individual follow-up interviews with Bolk, Nork and Vic were carried out after the observation period and focused on cultural references, the adaptation phase, the overall workflow and their particular involvement in the translation process.

The primary data comprises 94 comments from Google Docs on the novel’s adaptation (6,648 words). The secondary data includes transcripts of the five semi-structured interviews via Skype chat (12,613 words), field notes (5,942 words) and screenshots of the chat discussions and translations (55 images).

Analysis

The data was analysed in terms of qualitative content and discourse. The interviews and field notes were subjected to qualitative content analysis to extract information regarding the participants’ ideas on translating and adapting the text. Analysis of the interviews allowed us to identify translators’ common attitudes towards effective collaborative work and the adaptation of the translation for a global audience as well as their avowed common objectives, such as to achieve native-like language flow or high-quality translation. From the field notes, we found that the participants all valued plurilingualism, prioritized the quality of translation over time constraints and genuinely enjoyed translating and debating about the text in their free time.

The 94 comments comprising participants’ discussions during the adaptation phase were subjected to bottom-up content analysis following Schreier (Citation2012). We explored what topics the participants were discussing and the relation of those topics to transcultural meaning-making, where each single comment with its reference to the text of the novel represents a unit of analysis. Categories such as the logic of the narrative, stylistic errors, the fantasy world description, character development and cultural elements emerged from the topics of the comments.

We then used discourse analysis following Gee (Citation2011) to analyse the category of cultural elements (57 of 94 comments in total) in greater depth. We analysed what cultural adaptations the participants proposed to make and how they argued their propositions. From this analysis, categories such as semantic change (32 comments), stylistic change (16 comments) and content change (9 comments) emerged. We then focused on transcultural communication inside these categories. Following Bakhtin’s (Citation1986) notion of intertextuality and the above mentioned study by Baker and Sangiamchit (Citation2019), we indexed the instances of the use of different voices referring to various sociocultural products and contexts, which we coded as translanguaging and transcultural references. These data from the discourse analysis of the discussions were fully consistent with the results of our analysis of interviews and field notes, which supports the credibility of this study.

Results

Fan translation, as a practice, opens up great opportunities for reflecting on differences between cultures leading to intercultural learning (Vazquez-Calvo et al., Citation2020). During the translation process under study here, the participants had to discuss what parts of the novel they felt it was necessary to adapt culturally and how. The three main types of cultural changes required by the adaptation process, which resulted in different kinds of discussions and transcultural meaning-making, are presented in below.

Table 1. The three areas of discussion about elements of the translation that required cultural adaptation.

Most frequently, cultural adaptation concerned semantics, with the participants searching for the equivalents of idiosyncratic Russian expressions and proper nouns in English in order to make the text more fluent. Nonetheless, the changes proposed were usually straightforward and consensus was reached quickly, making the discussions relatively short (300 words in 32 comments). The second most prominent type of change regarded stylistics as participants attempted to adapt Russian narrative style to something more appropriate to modern English literature. This led to longer discussions (557 words in total), but mostly because style changes were often associated with other issues such as inadequate character development. The last area of discussion was concerned with bringing a character’s actions into line with the values and ideology of English-language literature. This topic yielded only two discussions, but these discussions were the longest and the most reflective ones. In the following section we will discuss each type of cultural change that provoked discussion and provide examples of participants’ comments.

Semantic change: idioms, puns, and proper nouns

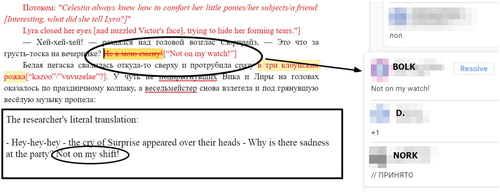

A clear example of this kind of discussion, which generally revolved around the translation of idioms, puns or proper nouns, can be seen in , in which Bolk proposes to change the Russian expression Не в мою смену ‘Not on my shift’ to the English expression ‘Not on my watch’ in order to make the phrase of the character-pony more authentic. Dan then approves the translation and Nork closes the discussion with the word Принято, ‘approved’.

In this case, Bolk demonstrated his intercultural and linguistic proficiency, and his proposed solution was quickly approved by the other participants. However, other issues of a semantic nature led to more extensive discussions in which the participants discussed semantic adaptation using different cultural and linguistic resources. This is illustrated in , where a discussion about the adaptation of the name of the character Дед ‘Grandad’ involves translanguaging and transcultural resources.

Table 2. Discussion surrounding how to adapt a character’s name.

In the first comment, Bolk proposes to change the name of the character, while mixing English and Russian together with the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets: Не grandfather.Footnote6 Не granddad. Not grandfather. Not granddad.’ where ‘не’ is written in Cyrillic. Bolk refers to the object of discussion (‘granddad’) in English, but makes his argument in Russian. Similarly, Dan (Comment 2) uses the two alphabets and languages when he writes он же Bart, он же Fart ‘he is also Bart, also Fart’. The main meaning is transmitted in Russian, while simultaneously there is a joke made in English with the Bart-Fart rhyme. In these two comments, the participants construct meaning through translanguaging as they easily switch between alphabets and languages in order to make an argument (Baker & Sangiamchit, Citation2019).

Moreover, according to our ethnographic notes, plurilingualism was of high value for the participants. In their Skype conversations, they were curious to ask each other how certain phrases could be translated into the various languages they knew, whether Polish, Hebrew, Ukrainian or Spanish. The use of multiple languages was viewed as an asset.

Going back to , we also see the interactants intertextually mix different cultural references in order to transmit meaning (Bakhtin, Citation1986). They talk about a grandfather from Siberia and try to modify his name into something in English with a different connotation. In order to describe this difference, Bolk in Comment 1 uses the analogy of а-ля Дон Карлеоне ‘like Don Corleone’, referring to the 1972 American movie The Godfather and thus making a global cultural reference. Then Dan (Comment 2) disagrees with Bolk and uses the pun of он же Bart, он же Fart ‘he is also Bart, also Fart’. Bart was the actual name of the character in the fanfiction novel, while Fart references the North American TV cartoon The Simpsons, since a universally known character from that cartoon, Bart, has been repeatedly called Fart Simpson in memes and gifs. This comment creates a playful double meaning which crosses several different cultural and linguistic boundaries. Responding to this, Bolk (Comment 3) defends his point of view by referring to the narrative of the fanfiction novel (‘Because he will die afterwards in an extravagant way’), bringing in the dimension of the plot of the fanfiction novel.

Because this mix of global cultural references of different origins manifests the free movement between cultures and national boundaries, this discussion can be labelled transcultural (Baker & Sangiamchit, Citation2019). To participate in this transcultural discussion, the interactants had to develop the ability to move through different references and languages (Kim, Citation2016). This discussion thus serves as an example of cross-border connections in discourse in the context of fan translation.

Stylistic change: modern English literature

The most common stylistic change debated by the translating team was related to a character’s thought process. The original Russian text contains many passages narrated from a third-person perspective. In many cases, the translators felt that a first-person ‘inner dialogue’ would be more consistent with rhetorical practice in English-language fiction. According to field notes and interviews, the participants called this practice a ‘show not tell’ technique and actively applied it during translation. As Bolk comments during the first interview:

Например, прием ‘мысли вслух’ – это как раз адаптация, потому что английский художественный текст требует соблюдения принципа show, don't tell, чего в русском языке нету.

‘For instance, the method “thoughts out loud” – is an adaptation because an English literary text needs to adjust to the rule show, don’t tell, which doesn’t exist in the Russian language.’

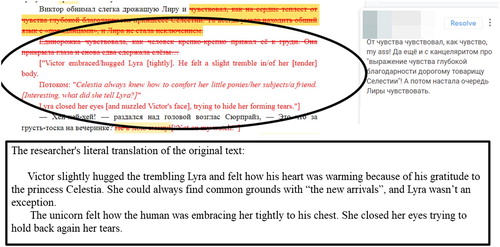

Similarly, in below Nork proposes to include more action to the text by cutting the parts about ‘feeling gratitude’, while also shifting from third-person narration to ‘inner thought’. He marks the ‘inner thought’ segment by using italics, inverted commas and the word Потоком ‘as a flow’.

Figure 3. Discussion among translators in which stylistic adaptation to an ‘inner thought’ narrative perspective is proposed.

In this case, the stylistic change was also executed as a norm, almost without discussion, with all participants fully aware of how to convey an ‘inner dialogue’. This collective meaning-making and agreement on differences between literary styles indicates how the participants portray themselves as mediators of different audiences with distinct literary traditions. Their self-positioning as mediators between different cultures also develops their ability to not only move across different cultural traditions but also develop reflective thinking about such differences.

Content change

In comments related to the adaptation of content, the most significant changes to the narrative discussed were aimed at culturally adapting the text for a global readership. The translators proposed to change the behavioural patterns of the characters in order to adapt them to what they assumed would be the cultural expectations of such a global readership. As an example, we present in an excerpt from the longest and most profound discussion in our data (6 comments, 356 words) regarding one character’s behaviour. In short, in this discussion, the main character Lyra talks to another pony, Princess Celestia (the leader of all the ponies in MLP:FiM), about the cruelty of the human world until Princess Celestia calms Lyra down by explaining to her that it is nearly impossible to change anything.

Table 3. Discussion of a content change based on cultural values.

In Comment 1, Nork proposes to change the character’s behavioural patterns by suggesting that Lyra should be more active and assertive to be more in keeping with the English literary traditions. Nork describes the ‘passive’ Lyra by using metaphors like ‘you just have to hide in a hole and sit there’ and a Russian idiom ‘hoping it won’t lead to anything’ which became popular due to Chekhov’s portrayal of an unassertive conformist in his novel The man in a case. Nork argues that ‘passiveness’ on the part of Lyra would be ‘OOC’ (out of character), as Lyra is a North American character that, albeit fictional, must be consistent with what one would expect of the heroine of a work of English literature. Being ‘OOC’ is a constant preoccupation in fanfiction writing, where it is essential that the portrayal of characters and setting in the fan text must be fully consistent with the original cultural product (Guerrero-Pico, Citation2015).

In the next turn, Nork bases his argument on the examples from literature, attributing Russian literary traditions to the passive ‘Chekhovian young lady’ as opposed to the active ‘Shakespearean school’: ‘the proactive heroine of the “Shakespearean school” would never agree to calmly sit on her rump and wait for death with her hooves folded like a Chekhovian young lady’. He argues that the novel’s ‘passive’ character could never be perceived as a ‘good’ one by an English-speaking audience. Nork reflectively alludes to the idea that our expectations for the ‘main character’ in literature are based on our previous reading experiences (his use of Chekhov’s idiom earlier is consistent with this idea). Moreover, in Nork’s comment cultural literary traditions are intertwined with the brony fandom references when he uses the word ‘hooves’ instead of the ‘hands’ one would expect. This reference to ponies keeps the discussion playful and appealing to his fellow bronies.

After extensive reasoning, Nork proposes to change the narrative by writing an alternative speech for one of the pony characters, Celestia. Curiously, while this speech is intended to be oriented to the English-language reader, it is mixed with references to Soviet popular culture. For example, the phrase Наше дело правое ‘Our cause is just’ is from the 1941 radio speech announcing the entry of German forces into the USSR at the outset of the Second World War. The following phrases Служба и опасна, и трудна ‘Service is both dangerous and difficult’ and Но на первый взгляд конечно не видна ‘But could not be observed at first glimpse’ are both quotes from a song featured in a very famous Soviet TV series called Investigation held by Znatoki (1971–1989). Both references are widely known in the former USSR and form part of the common ground of the participants. With these cross-border connections, Nork illustrates the actual ‘activeness’ and ‘assertiveness’ of fictional characters in the Soviet Union, which goes against the categorization of all Russian fictional characters as ‘passive’.

Nork does not reflect on this slight inconsistency in the use of references. Most likely he uses them to appeal to other participants and to make the comment playful while negotiating his post-Soviet cultural identity. At the end of Celestia’s speech, Nork uses different languages and alphabets playfully, writing Ожидай инструкций, майн зольдатен ‘Wait for instructions, mein soldaten’, the last two words being German transliterated in Cyrillic. Here he humorously frames Celestia as a German commander sending her troops on a mission, in the process crossing linguistic and cultural boundaries (Baker & Sangiamchit, Citation2019). In sum, in just one comment, Nork defends his argument by juggling references to Russian and English literary traditions, the MLP:FiM cartoon series, fanfiction values, Soviet popular culture and German military discipline.

Later on, Bolk (Comment 2) disagrees with Nork’s opposition of ‘Chekhovian young lady’ to the active ‘Shakespearean school’, providing a counter-argument for which he switches to English at the end of his comment (here in italics): ‘Meanwhile in reality, I recall a British newspaper headline about a recent terrorist attack in Manchester about how Britain should carry on as if nothing happened (as it did countless times before)’. His opening ‘meanwhile in reality’ proclaims his proposition as valid and ‘objective’, while it also questions the validity of Nork’s literary examples (Martin & White, Citation2005). By using English, he not only reinforces his claim to validity but also negotiates his expertise as an English speaker. His opening ‘meanwhile in reality’ proclaims his proposition as valid and ‘objective’ while it also questions the validity of Nork’s literary examples (Martin & White, Citation2005). By using English, he reinforces this claim to validity and also negotiates his expertise as an English speaker. He questions the British values of ‘assertiveness’; however, he does not re-categorize these values or compare them to Russian values. Later, in comment 4, Nork reflects on the origin of the phrase ‘Keep calm and carry on’, which he identifies as a transcultural reference to the WW2 poster whose presumed message is that a civilised person never loses his or her cool but just continues with daily life as usual. With this reflection, he argues that Bolk’s argumentation is based on a false assumption.

Meanwhile, in comment 3, Dan questions Shor’s argument about the proactiveness of Princess Celestia. He reacts to Celestia’s ‘militaristic’ speech and makes a transcultural reference to Michael Collins, the twentieth century Irish freedom fighter, thus demonstrating his expertise in British culture and history. At the end of the discussion, Bolk agrees about the meaning of the British headline and asks Nork to show his version of the fragment.

In every argumentation strategy, we see an abundance of different cultural references and translinguistic play. The cultural references serve two main communicative purposes: to back up the argument and to reinforce the bond of shared knowledge among peers. The data indicate that references to British culture and the use of English are of value for the participants because they serve as evidence of their expertise in the topic of adaptation, while the references to Soviet culture and ponies are made to appeal to other team members. Moreover, the importance they place on evidentiality and objectivity indicates that the interactants are eager to show the credibility of their point of view, yet also attempt to stay neutral with respect to the comparison of different traditions and cultural values by avoiding the us/them dichotomy. They also reflect on the arguments of their team members questioning cultural assumptions. However, there is some lack of criticality when the expectations of the English-speaking readership are generalized. Moreover, when they hypothesise about assertiveness or passiveness of a female character, they do not problematize or discuss gender, unlike what has been observed in previous works on the brony fandom (Lehtonen, Citation2017). The problem was addressed only in connection with literary traditions without critical reflection on its possible intersectionality. Nevertheless, we would argue that the respectful reflection on these cultural topics, the ability to question cultural assumptions and the general interest in another culture indicate the deep engagement of these fanfiction translators in transcultural literacies.

Discussion and conclusions

Our participants engaged in online discussions of issues arising from the adaptation of a Russian fanfiction novel for a global readership. In this highly collaborative team activity, the participants had to exchange views and come to agreement. The collaborative and participative nature of this translation process indicates that it could be characterized as a new literacy practice in the sense that the fan translators share their distributed knowledge and follow certain values and norms of the community (Lankshear & Knobel, Citation2006; Vazquez-Calvo, Shafirova, et al., Citation2019; Vazquez-Calvo, Zhang, et al., Citation2019; Zhang & Cassany, Citation2016). Moreover, this practice can be linked to the notion of transcultural literacies given that it involves, following Kim (Citation2016, p. 205), ‘new paths and combinations for cross-border connections and self-representations’. These new paths for cross-border connections can be seen in the transcultural discussions related to the adaptation phase of the translation process. These discussions included transcultural communication and translanguaging (Baker & Sangiamchit, Citation2019) and emerged as a result of the movement between different localities, cultures and nation-states (Pennycook, Citation2007).

Analysing the ‘new paths for cross-border connections’, these discussions reveal three different types of cultural adaptations, namely semantic (i.e. finding English equivalency for idiomatic expressions or word-play), stylistic (i.e. changing style to make it consistent with English stylistic traditions) and content-related (i.e. changing elements of character, behaviour or setting to make it credible and appropriate to an English-language readership). We found that each type of discussion activated a different level of reflection and transcultural communication. In the first type, related to semantics, the participants reflected on the differences between audiences, occasionally engaging in transcultural discussions; however, they almost never engaged in profound, reflective discussions. The second type of discussion, related to style, implied more profound reflection, revolving around differences in literary traditions (though the participants seemed to have previously reached agreement, thus reducing the need for further discussion). Finally, the third and least frequent type of discussion, related to content, not only produced the longest turns but was also the most polemical and reflective. Here, the participants constructed elaborate arguments regarding cultural differences between the Russian and English literary traditions, values and philosophy.

We suggest that the mixed cultural context present here (translators from different Post-Soviet countries, North American cartoon, fanfiction written in Russian for the Russian-speaking audience being translated into English for English speaking audience) encouraged the translators to use different cultural references during their discussions and to reflect on some of these references. Transcultural communication and translanguaging mostly appeared in this type of discussion, serving to bolster evidentiality and linguistic and cultural play while appealing to the other participants. Hence, we can see that discussions about major changes in the translation opened up more opportunities for not only reflection on the text but also a fuller use of cross-border connections and transcultural communication (Baker & Sangiamchit, Citation2019). We suggest that this type of discussion was the most fruitful for the development of transcultural literacies as it induced reflection about the differences between cultures (Kostogriz & Tsolidis, Citation2008) and elicited different cross-border connections (Black, Citation2006; Kim, Citation2016).

A further indication of the participants’ engagement in transcultural literacies is the way they revealed new forms of self-representation (Kim, Citation2016; Pandey et al., Citation2007). The participants positioned themselves as ‘mediators’ between different cultures (similarly to what is reported in Vazquez-Calvo, Shafirova, et al., Citation2019). As mediators, they had not only to appear more objective and constructive in their argumentation, but also to obtain some knowledge about the British and Russian cultures, literary genres and traditions, the rules of fanfiction writing and the brony fandom. We suggest that self-positioning as mediators in this cross-border meaning-making process pushed them to be reflective about each other’s arguments, to avoid the us/them dichotomy and, in consequence, to engage in transcultural literacies. The participants in previous studies (Kim, Citation2016; Kostogriz & Tsolidis, Citation2008) engaged in transcultural literacy practices by affiliating with other cultures (Korean culture in the case of Kim, Citation2016), or with different nation-states (in the case of Kostogriz & Tsolidis, Citation2008). Meanwhile, in the context of fan translation, the cultural mediator identity is one of the ways to engage in transcultural literacies by listening to an interlocutor’s position, by using playful translinguistic and transcultural resources in argumentation and by reflecting on cultural differences in dialogue.

All in all, this study adds to our knowledge about the novel and unexplored concept of transcultural literacies while it also sheds the light on the transcultural discussions of young people from Eastern Europe, outside the dominating Westernized perspective. In particular, it draws parallels between transcultural communication and transcultural literacies, underlining how cross-border connections can be constructed. Finally, it shows the rich opportunities for reflective transcultural discussion that arise for those who engage in fan translation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Liudmila Shafirova is a researcher associated with the Department of Translation and Language Sciences, Pompeu Fabra University, Spain. Her research interests include informal language learning (Russian, English), multilingual computer-mediated interactions, identity building online and transcultural literacies.

Daniel Cassany is a professor at the Department of Translation and Language Sciences, Pompeu Fabra University, Spain. Daniel currently leads the research group GRAEL and a research project ForVid. His current research interests include multiliteracies, online language learning and educational ethnography.

Carme Bach is a Serra Hunter fellow and associate professor at the Translation and Language Sciences Department of Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona. Her current interests include discourse analysis, transculturality and language learning.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The writing of alternative fictional narratives based around pop culture products.

2 The translation and subsequent audio overdubbing of an audiovisual product.

3 Exact numbers are not provided in the interest of data protection.

4 A platform for collaborative writing, similar to Google Drive.

5 This study was compliant with the guidelines of the International Association of Internet Researchers (Markham & Buchanan, Citation2012). All the participants were fully informed about the study and signed a participation consent form which explicitly gave their permission to publish direct quotations. Participants’ real names have been replaced with pseudonyms.

6 We have marked the use of different languages and the Latin alphabet with boldface for clarification purposes.

References

- Aliagas, C. (2017). Rap music in minority languages in secondary education: A case study of Catalan rap. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2017(248), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2017-0036

- Baker, W., & Sangiamchit, C. (2019). Transcultural communication: Language, communication and culture through English as a lingua franca in a social network community. Language and Intercultural Communication, 19(6), 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2019.1606230

- Bakhtin, M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. University of Texas.

- Black, R. W. (2006). Language, culture, and identity in online fan fiction. E-learning, 3, 170–184. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2006.3.2.170

- Black, R. W. (2008). Just don’t call them cartoons: The new literacy spaces of anime, manga and fanfiction. In J. Coiro, M. Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D. J. Leu (Eds.), Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 583–610). Erlbaum.

- Burrell, J. (2009). The field site as a network: A strategy for locating ethnographic research. Field Methods, 21(2), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X08329699

- Darvin, R., & Norton, B. (2017). Investing in new literacies for a cosmopolitan future. In R. Zaidi & J. Rowsell (Eds.), Literacy lives in transcultural times (pp. 89–101). Routledge.

- DeWalt, K., & DeWalt, B. (2011). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers. Altamira Press.

- Gee, J. (2011). How to do discourse analysis: A toolkit. Routledge.

- Gee, J. P., & Hayes, E. (2012). Nurturing affinity spaces and game–based learning. In C. Steinkuehler, K. Squire, & S. Barab (Eds.), Games, learning, and society: Learning and meaning in the digital age (pp. 129–153). Cambridge University Press.

- Guerrero-Pico, M. (2015). Producción y lectura de fan fiction en la comunidad online de la serie Fringe: transmedialidad, competencia y alfabetización mediática. Palabra Clave - Revista de Comunicación, 18(3), 722–745. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2015.18.3.5

- Hautakangas, M. (2015). It’s ok to be joyful? My little pony and brony masculinity. The Journal of Popular Television, 3(1), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1386/jptv.3.1.111_1

- Hepp, A. (2009). Transculturality as a perspective: Researching media cultures comparatively. [33 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-10.1.1221

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Fans, bloggers, and gamers: Exploring participatory culture. New York University Press.

- Jones, R. H. (2019). Creativity in language learning and teaching: Translingual practices and transcultural identities. Applied Linguistics Review. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2018-0114

- Kim, G. M. (2016). Transcultural digital literacies: Cross-border connections and self-representations in an online Forum. Reading Research Quarterly, 51(2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.131

- Kostogriz, A., & Tsolidis, G. (2008). Transcultural literacy: Between the global and the local. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 16(2), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681360802142054

- Kytölä, S. (2016). Translocality. In A. Georgakopoulou & T. Spilioti (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language and digital communication (pp. 371–388). Routledge.

- Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2006). New literacies: Everyday practices and classroom learning. Open University Press.

- Lam, W. S. E. (2006). Re-envisioning language, literacy, and the immigrant subject in new mediascapes. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 1(3), 171–195. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15544818ped0103_2

- Lee, H. (2016). Developing identities: Gossip Girl, fan activities, and online fan community in Korea. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 13(2), 109–133.

- Lehtonen, S. (2017). “I just don’t know what went wrong”: Neo-sincerity and doing gender and age otherwise in a discussion forum for Finnish fans of my little pony. In S. Leppänen, E. Westinen, & S. Kytölä (Eds.), Social media discourse, (Dis)identifications and diversities (pp. 287–309). Routledge.

- Markham, A., & Buchanan, E. (2012). Ethical decision-making and Internet research: recommendations from the AoIR ethics working committee (version 2.0). http://aoir.org/reports/ethics2.pdf

- Markham, A. N. (2017). Ethnography in the digital internet era. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 650–668). Sage Publications.

- Martin, J. R., & White, P. R. (2005). The language of evaluation: Appraisal in English. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ntelioglou, B. Y. (2017). Examining the relational space of the self and other in the language-drama classroom: Transcultural multiliteracies, situated practice and the cosmopolitan imagination. In R. Zaidi & J. Rowsell (Eds.), Literacy lives in transcultural times (pp. 58–72). Routledge.

- Pandey, I. P., Pandey, L., & Shreshtha, A. (2007). Transcultural literacies of gaming. In L. Cynthia, E. SelfeGail, & D. I. Hawisher (Eds.), Gaming lives in the twenty-first century (pp. 37–51). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230601765_3

- Pennycook, A. (2007). Global Englishes and transcultural flows. Routledge.

- Sauro, S. (2017). Online fan practices and CALL. Calico Journal, 34(2), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.33077

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage Publications.

- Shafirova, L., and Kumpulainen, K. (20XX). Online collaboration in a brony fandom: Constructing a dialogic space for identity work in a fan translation project. E-Learning and Digital Media, in review.

- Shafirova, L., & Cassany, D. (2019). Bronies learning English in the digital wild. Language Learning and Technology, 23(1), 127–144. https://doi.org/10125/44676

- Shafirova, L., Cassany, D., & Bach, C. (2020). From “newbie” to professional: Identity building and literacies in an online affinity space. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 24, 100370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100370

- Sultana, S., & Dovchin, S. (2016). Popular culture in transglossic language practices of young adults. International Multilingual Research Journal, 11(2), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2016.1208633

- Thorne, S. L. (2008). Transcultural communication in open internet environments and massively multiplayer online games. In S. Magnan (Ed.), Mediating discourse online (pp. 305–327). Amsterdam.

- Thorne, S. L., Black, R. W., & Sykes, J. M. (2009). Second language use, socialization, and learning in Internet interest communities and online gaming. The Modern Language Journal, 93, 802–821. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00974.x

- Valero-Porras, M. J. (2018). La Construcción discursiva de la identidad en el fandom: estudio de caso de una aficionada al manga (Doctoral dissertation, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain). https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/459254

- Valiente, C., & Rasmusson, X. (2015). Bucking the stereotypes: My little pony and challenges to traditional gender roles. Journal of Psychological Issues in Organizational Culture, 5(4), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpoc.21162

- Vallejo, C., & Dooly, M. (2019). Plurilingualism and translanguaging: Emergent approaches and shared concerns. Introduction to the special issue. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1600469

- Vazquez-Calvo, B. (2018). The online ecology of literacy and language practices of a gamer. Educational Technology & Society, 21(3), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.2307/26458518

- Vazquez-Calvo, B., Elf, N., & Gewerc, A. (2020). Catalan teenagers’ identity, literacy and language practices on YouTube. In M. R. Freiermuth & N. Zarrinabadi (Eds.), Technology and the Psychology of second language learners and users (pp. 251–278). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vazquez-Calvo, B., Shafirova, L., Zhang, L. T., & Cassany, D. (2019). An overview of multimodal fan translation: Fansubbing, fandubbing, fan translation of games and scanlation. In M. Ogea Pozo & F. Rodríguez Rodriguez (Eds.), Insights into audiovisual and comic translation. Changing perspectives on films, comics and videogames (pp. 191–213). UCOPress.

- Vazquez-Calvo, B., Zhang, L. T., Pascual, M., & Cassany, D. (2019). Fan translation of games, anime, and fanfiction. Language Learning & Technology, 23(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10125/44672

- Zaidi, R., & Rowsell, J. (2017). Introduction. In R. Zaidi & J. Rowsell (Eds.), Literacy lives in transcultural times (pp. 1–15). Routledge.

- Zhang, L. T., & Cassany, D. (2016). Fansubbing from Spanish to Chinese: Organization, roles and norms in collaborative writing. BiD: Textos universitaris de biblioteconomia i documentació, 37(2). http://bid.ub.edu/en/37/tian.htm

- Zhang, L. T., & Cassany, D. (2019). Prácticas de comprensión audiovisual y traducción en una comunidad fansub del español al chino. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics, 32(2), 620–649. https://doi.org/10.1075/resla.17013.zha