ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to set out to explore how children living in Polish-English transnational families in the UK develop symbolic competence and symbolic power in home settings. By focusing on the children’s use of metaphor in family discourse when talking about the Moon, from a cognitive discursive perspective, this study explores the children’s creative use of language in achieving their social goals. It moves beyond seeing language, cognition and culture as bounded systems but rather powerful meaning-making resources that are part of the children’s complex discourse-worlds. The findings show how transnational families provide children rich opportunities to develop intercultural or ‘transcultural’ competence.

Celem niniejszej pracy badawczej było zbadanie, w jaki sposób dzieci mieszkające w transnarodowych polsko-angielskich rodzinach w Wielkiej Brytanii rozwijają w warunkach domowych kompetencje symboliczne i władzę symboliczną. Opisując z kognitywno-dyskursywnej perspektywy badawczej, użycie przez dzieci metafory w dyskursie rodzinnym, podczas rozmowy o księżycu, praca ta rzuca światło na twórcze użycie języka przez dzieci w osiąganiu celów społecznych. Język, procesy poznawcze i kultura nie są w niniejszej pracy postrzegane jako odrębne systemy, ale raczej jako potężne zasoby znaczeniotwórcze, stanowiące część złożonych dziecięcych światów dyskursywnych. Wyniki badania wskazują, w jaki sposób rodziny międzynarodowe zapewniają dzieciom bogate możliwości rozwijania kompetencji międzykulturowych lub ‘transkulturowych’.

Introduction

This study focuses on the spoken discourse of Polish-English transnational children from two families living in Glasgow, UK. The findings suggest that transnational family environments provide rich opportunities to develop intercultural competence, in particular symbolic competence (Kramsch, Citation2006).Footnote1 This notion refers to an ability that goes beyond a simple decoding of the language to an understanding of the dynamic, ongoing meaning-making processes of the interactions taking place during any communicative act (Kramsch, Citation2006; Kramsch, Citation2020). In a country where monolingualism is the prevailing ideology (Phipps & Fassetta, Citation2015), and where multilinguals are often framed in the deficit (Dakin, Citation2017; Safford & Drury, Citation2013), multilinguals’ cultural and linguistic resources are often left untapped to the detriment of both the individual and to our multicultural society (Bailey & Marsden, Citation2017). This study’s exploration of transnational children’s often creative use of language shows them as having competences that are becoming ever more necessary in our dynamic multilingual world.

Transnational children are used to navigating their way in and between the heritage and majority language and culture and they frequently know aspects of the host’s cultural norms and values more than their parents. Additionally, they have been shown to take a strong active role in the socialisation process, which can lead to traditional parent–child roles in the family being disrupted (Luykx, Citation2005; Renzaho et al., Citation2017). Whilst recent transnational studies have examined these changes through the lens of children’s agency from a sociolinguistic perspective (Said & Hua, Citation2017), I am not aware of any multilingual or transnational studies that have explored what language reveals about the cognitive architecture of the interlocutors during family interactions. Thus, this paper aims to explore the language children use to express their thoughts in family discourse and the effect it has on other family members. By focusing on this aspect of language use, it becomes possible to gain a deeper understanding not only of the social but also the conceptual motivations transnational children have to bring about such changes to the family dynamics.

The present article focuses on the spoken discourse of four children (aged between 7 and 10) of two Polish-English speaking families, living in Glasgow, who participated in the AHRC funded Creative Multilingualism project: The Moon in narrative, metaphor and reason: a multilinguistic perspective. As the Moon is an object of significant cultural interest, with each cultural community attaching its own symbolic meaning to it, it is a particularly useful lens to explore transcultural variation between different communities. Not only did the project reveal what cultures share, and how the meaning of the Moon varies across cultural groups (Zacharias, Citation2019), but it also explored how the variation was profoundly influenced by the participants’ social position within the family, as well as their worldviews and what texts the participants had engaged with, in other words, their knowledge, memories and ideologies they had.

Culture can be thought of as a set of shared ways to frame concepts that characterise groups of people. Many of these cultural understandings are reflected in the metaphors used by the members of a cultural group (Kövecses, Citation2005, p. 2, Citation2015; Sharifian, Citation2011), whereby a metaphor can be understood here as a device ‘through which we perceive or experience one entity in terms of another’ (Littlemore, Citation2019, p. 1). Due to the cultural significance of metaphors, the focus of the analysis in this study is on the metaphors the participants used to talk about the Moon. Focusing on metaphors allowed me not only an insight into the more established cultural resources that the participants were drawing from but also how and why they created novel language, in this case metaphor, to respond to the situation they were in, a key aspect of the concept of symbolic competence (Hult, Citation2014; Kramsch, Citation2006).

The innovative aspect of this paper lies in the approach of analysis, which fuses elements of sociolinguistics (Bourdieu, Citation1991; Kramsch, Citation2006, Citation2020; Reid & Ng, Citation1999) and metaphor theory (Kövecses, Citation2005, Citation2015; Littlemore, Citation2019), which belongs to the larger field of cognitive linguistics, an approach to understanding the relationship between conceptual thinking and language. Recent metaphorical research has called for a more ecological approach to understanding metaphor use, in which its use is inherently situated in and emerges from particular cultural, social, individual and environmental circumstances (Gibbs, Citation2020, p. 18). This approach that integrates insights from both cognitive linguistics and sociolinguistics moves beyond seeing language, cognition and culture as bounded systems. In other words, rather than shying away from the messiness and complexity of understanding metaphor in discourse, this paper, by acknowledging the situated, dynamic, contextual and, interactional factors at play, provides a more holistic view of the meaning-making processes involved. Thus, a fuller understanding of the symbolic competencies that emerge in the transnational children becomes possible.

By focusing on metaphor as a discourse phenomenon, then, it becomes possible to trace how the transnational children negotiate their position of power in family interviews to be able to affect changes through their own (re) interpretation of the cultures they belong to.

Research context

This study was part of the Open World Research Initiative project: The Moon in narrative, metaphor and reason: A multilinguistic perspective, that was funded by the four-year (2016–2020) AHRC ‘Creative Multilingualism’ research programme, whose primary aim was to investigate the rich connections between linguistic diversity and creativity in contemporary Britain. Central to the research programme was the notion that there exists a fluid interplay between the different languages spoken in Britain that becomes a creative force that shapes how we live our lives. The programme advocates that being multilingual is part of the human condition (Kohl & Ouyang, Citation2020), whether it is the ability to speak more than one official language such as Polish or English, or being able to switch between registers: from telling a joke in the local dialect to a family member, to talking to a pet dog, or to writing an essay for school. The programme advocates that successfully adapting to our ever-changing environment requires all of us to creatively draw on, and shift between, the different cultural, cognitive and linguistic resources that we have at our disposal to collectively meet our current intellectual and social challenges (Kohl et al., Citation2020). This paper focuses on this phenomenon in transnational families, in particular the children, who by having to skilfully negotiate their way between cultures develop a translingual metalinguistic awareness in that they start to recognise the power of the languages they are in contact with. They become aware of the various effects of the languages they use and how they bring about changes in the others’ thoughts, emotions and behaviour, in other words, as Bourdieu (Citation1991) described it, the ‘symbolic power’ behind the language used.

Transnational families

Due to the recent intensification of globalisation, the number of transnational families worldwide has increased significantly. A transnational family maintains a sense of familyhood, despite the fact that the members are unable to be physically close to each other (Bryceson & Vuorela, Citation2002). Poles are the largest white migrant group in Scotland. Since the enlargement of the European Union in 2004, Scotland has seen a sharp rise in the number of Poles settling in the country, with the number of Polish-speaking children in schools at approximately 17,000 (Scottish Government, Citation2020).

With the increase in the numbers of transnational families, there has also been an increase in the amount of research carried out on transnational family life. Various topics have been studied, for example, identity (Chamberlain & Leydesdorff, Citation2004); emotions and belonging (Skrbiš, Citation2008); and intergenerational relations (Parreñas, Citation2005). More recently, attention has been given to the socialisation process both from the perspective of the caregivers and the children, with a focus on the participants' agency (Fogle & King, Citation2013; Said & Hua, Citation2017). Echoing Said and Hua’s (Citation2017) research on language socialisation, this paper also focuses on the children’s ability to bring about change in thought and action, however, instead it uses the concepts of symbolic competence and symbolic power (Bourdieu, Citation1991; Kramsch, Citation2006, Citation2020) to make sense of this process.

Symbolic competence and symbolic power

The transnational context of the project reflects the dynamics of increased contact between people from different cultural backgrounds. These situations have called for new notions of ‘competence’ that go beyond the functional notions of accuracy, efficiency and appropriateness of Hymes’s long-standing communicative competence (Kramsch, Citation2006). Even in interactions in which the same linguistic form is used, alternative interpretations will arise due to the different personal, social and historical trajectories each communicator is part of (Kramsch, Citation2006; Sharifian, Citation2013). As Kramsch (Citation2006, p. 251) reminds us:

Language learners are not just communicators and problem solvers, but whole persons with hearts, bodies, and minds, with memories, fantasies, loyalties, identities. Symbolic forms are not just items of vocabulary or communication strategies, but embodied experiences, emotional resonances, and moral imaginings.

Much linguistic research in this area has focused on language teaching contexts. In Li Wei’s (Citation2014) study, for example, he analyses multilinguals’ language practices in a Chinese complementary school in the UK, observing discrepancies between the teachers’ and the learners’ symbolic competencies, with teachers wishing to ‘transmit certain cultural values’ that are met with resistance from the pupils leading them to use their languages in creative ways. Application of the concept of symbolic competence to out-of-classroom settings is rarer. One notable exception is Hult’s study (Citation2014), which employed ethnographic and sociolinguistic approaches to explore the insider/outsider identities of covert bilinguals in Swedish speech settings. Both these studies illustrate a strong sociolinguistic tendency to explore symbolic competence. Yet, whilst Kramsch (Citation2011, p. 357) notes in her paper that symbolic symbols ‘are to be seen as conceptual categories, idealized cognitive models of reality that correspond to prototypes and stereotypes through which we apprehend ourselves and others (e.g. Fauconnier & Turner, Citation2002; Lakoff, Citation1987)’, there is a paucity of studies which explore symbolic competence and symbolic power from a cognitive-discursive perspective. This study hopes to make a contribution to fulfilling this gap.

Transcultural environments and prototypical understandings of the Moon

Cultures and languages, we are part of, offer us symbolic symbols (Kramsch, Citation2011), typical, ‘prototypical’ concepts at our disposal that act as common reference points for members of a community to use when communicating. Part of becoming a member of this culture is learning what these reference points are. To understand each other successfully in a transcultural environment is the ability to recognise that the variation in how we conceptualise the world depends, to a large extent, on the language varieties we speak and the cultures we are part of (Sharifian, Citation2013).

As the languages we use have evolved through the interactions with both our material and social environments our conceptualisations (e.g. schemas, categories and conceptual metaphors) are largely cultural in nature (Kövecses, Citation2015; Sharifian, Citation2011). In turn, how we, as members of particular cultural communities use language to express our thoughts provides cultural meaning and variation (Sharifian, Citation2013). Each language community builds its own shared prototypical representation of its cultural symbols. The Moon is a particularly suitable lens for comparing and understanding different cultures as it features so strongly in all cultures. It acts as ‘a cultural mirror’ as every culture has stories to tell about the Moon (Jerram, Citation2017). In Polish culture, for example, the Moon frequently symbolises the mind, frequently an unstable mind and sometimes humour too, as reflected in the expression ‘spadł z księżyca’ (fall from the Moon) that is used to describe someone’s strange behaviour.

Many of these cultural symbols are conventional expressions that can be understood metaphorically. For example, in the expression ‘the Moon is made of green cheese’, that has found its way into children’s story books across the globe, the Moon is taken to be a round cheese wheel. Importantly, for this study, due to the cultural prototypes’ ubiquity in the language, they belong to people’s shared, everyday knowledge within each cultural group (Moon, Citation1998). Such stable associations, that specific cultural groups have about the Moon and reflect ‘the community’s conventional patterns of thought or world views’ (Boers, Citation2003, p. 235). This shared knowledge was reflected in the group interviews and was used in the analysis as one means to infer the meaning of the participants’ utterances.

Methodology and analytical approach

To explore the use of metaphor in the spoken discourse of the two families I designed, set up and administered two group interviews in each of the families’ homes. A purposive sampling approach was adopted and participants were recruited through personal contacts. Each family group interview lasted between 45 minutes to an hour. To create a relaxed atmosphere in which the family members, in particular the children felt at ease, the interviews were conducted at the home of the participants. The interview questions were designed to elicit from the participants their memories and experiences of seeing the Moon, any associations they made between the Moon and any cultural artefacts, such as books they had read or films they had seen. As different cultures ascribe a different gender to the Moon, there was also the opportunity to comment on whether they understood the Moon to be masculine or feminine. The participants were reassured that they were not going to be tested on their knowledge about the Moon; there were no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answers. The interview was semi-structured in design and included questions such as:

Can you describe the Moon?

Can you describe the last time you saw the Moon?

Would you say the Moon is masculine or feminine?

What does the Moon remind you of?

Whilst I, the interviewer, spoke only English, the interviews were conducted in both Polish and in English. The participants were encouraged to speak both languages as they normally would to each other at home. The first family ‘A’ had both a Polish mother and father who had lived in the UK for 14 years. Their two daughters were both born in the UK, and were Ania (pseudonym), 10 years, and Hanna (pseudonym), 8 years, respectively. The second family ‘B’, had a Polish mother and a Scottish father. Only the mother was present at the interview. The older sibling, Janek (pseudonym), 9 years, had spent the first four years of his life in Poland, whilst his younger sister Marta (pseudonym), 7 years, had spent just 11 months. Both children attended the local Polish community school regularly on Saturday mornings. The two families actively maintained Polish and spoke both languages at home.

Positionality of the researcher

The flexible nature of the interview allowed me to respond and follow up on the prepared set of questions and my responses reflected my own desires, needs and emotions as I interacted with the family members. The social roles and relationships which were enacted throughout the interviews can be conceived of as the ‘positionality’ of the researcher (Coffey, Citation1999; Copland, Citation2015). At the start of the interview process, a couple of the adult participants expressed they were anxious about being interviewed on a topic they felt they had little knowledge about, and that they might not be able to provide answers that I, the researcher, was hoping for. Another source of anxiety amongst the adult participants was their concern about how to interact with their children, in Polish and English, to a guest in their home who was there to carry out research. Being a parent from a bilingual household myself, I empathised with the parents, yet was also aware of the unique opportunity I had to collect data for my project. This tension was most acute at the start of the interviews but eased a little once an interview pattern had established, and the children appeared to take it all in their stride.

Approach to analysis

All the interviews were audio recorded and later translated and transcribed independently for the first stage of a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). I was mainly interested in sections of the transcript that linguistically represented a change brought about by the children and therefore examined passages in the transcript that showed changes in behaviour, attitude or emotion initiated by the children’s speech. Within these episodes, I investigated the children’s symbolic competence and symbolic power by exploring how the children utilised their apparent knowledge of the two languages and cultures to pursue their social goals. In addition, as I anticipated the participants might use metaphor to describe the Moon, for reasons outlined above, I drew on metaphor theory (Cameron & Maslen, Citation2010; Kövecses, Citation2005; Littlemore, Citation2019) and cognitive linguistics, e.g. conceptual blending theory (Fauconnier & Turner, Citation2002), more broadly, to explore these metaphors further and the impact they had on the social and cognitive dynamics.

As the analysis took place after the interviews, the sections of the data that were selected and closely analysed and later presented were lifted from their ‘original’ context. This resulted in me construing the social realities of the participants in different ontological domains: one at the interview as I remembered it and the other as I read the transcripts. Although these two versions of the event were occasionally realised in my mind as two separate realities, they often blended in my mind to form one reality. The constant toggling between these different layers of realities, meant a cautious approach to the analysis was necessary. My aim, however, was to make my inferences as transparent as possible to allow for verification to enhance the trustworthiness of my claims.

One further aspect of the process is worth mentioning. As I read the transcript, I developed a further sense of who the participants were through a process of characterisation. By reading the transcript and soft-assembling other snippets of knowledge I gained of the participants, for example their age, position in the family, and profession, I developed a mini-mental model (Stockwell, Citation2020) of the participants and I used this schematic knowledge to interpret the cognitive and social dynamics of the interaction. To help overcome any potential biases that might have arisen from this characterisation process, I was able to check my interpretations with family members and a Polish speaker.

One complication was that I do not speak Polish and therefore I was heavily reliant on the English translation of the events that took place. To overcome this obstacle, my interpretations were also read and checked by a Polish speaker. Our combined linguistic and cultural knowledges, including mental-models of the participants, constituted our discourse-worlds (Gavins, Citation2007; Kramsch, Citation2006; Werth, Citation1999), which allowed for a more rigorous interrogation of the data. In sum, there was myself, an English speaker, who had carried out the interviews and who approached the analysis of the English written texts with a vivid recollection of the interviews, and there was a Polish/English speaker, who, although not present at the interviews, drew on her knowledge of both languages and cultural prototypes to help me interpret the texts.

The analysis of the data involved a number of stages. As the focus of the analysis was on spoken discourse, the analysis followed the steps of the discourse dynamics approach outlined by Cameron and Maslen (Citation2010). Here, after first reading through and familiarising myself with the entire transcript and recalling the events of the interview, I identified any potential metaphors. Rarely, did the entire metaphor reveal itself explicitly in the text. However, from knowing the topic of conversation and the context, the topic of the metaphor was, in most cases, the Moon itself. The entity that the Moon (or Moon’s light, shape, etc.) was being compared to, surfaced in the language as a ‘lexical unit’; either an individual word or phrase (Cameron & Maslen, Citation2010, p. 103). Sometimes, they were expressed as a direct metaphor, or a simile, where the speaker made it clear that one entity is being compared to another: ‘A is like B’. The lexical unit was labelled as metaphoric if its meaning in the context contrasted to a more basic meaning. During the analysis, I noticed that the metaphors were either conventional or more creative. Seeing the degree of creativity of the metaphors used in the spoken discourse to be both an individual and social phenomenon, I took creativity to be ‘the interplay between ability and process by which an individual or group produces an outcome or product that is both novel and useful as defined within some social context’ (Plucker et al., Citation2004, p. 90), and used this definition to guide my analysis. The findings were then discussed and verified with the Polish/English speaker.

Findings

Analysis one: mothers, daughters, moons and croissants

The following episode is from the group interview with family ‘A’. Here, the family were asked to describe the Moon and also, what it looked like the last time they saw it. The mother and father started responding to my questions in both English and Polish, with Ania, the eldest daughter, listening first in the wings before offering her own answer. Hanna, the youngest daughter, fidgeting a little, had just been asked to sit next to her father. This episode is near the start of the interview, when the participants were still settling down. Possibly for this reason, the mother takes quite an assertive role in steering the conversation by asking her own questions to both myself and her husband. The conversation moves at a fast pace.

So, how would you describe the Moon?

What the moon looks like, right? Um, więc księżyc jest okrągły, albo ma kształt sierpa jest srebrny, ma szare plamy, które odpowiadają kraterom i wzgórzom na księżycu. [So, the Moon is round, or has a shape of a sickle, it is silver, has grey spots which mean there are craters and hills on the Moon.] Would you agree?

It is quite tricky actually. Księżyc jest różny. [The Moon is versatile/different every time.]

Różny? A co masz na myśli? Co masz na myśli mówiąc, że jest różny? [Versatile? What do you mean? What do you mean saying that it is versatile?]

Może być srebrny, może być szary. Może być czerwony, pełny pusty. [It can be silver, it can be grey. It can be red, full or empty.]

Jak może być pusty? [How can it be empty?]

You can still see the outline so it’s just empty.

When you last saw the moon, can you remember when you last saw the moon? What you saw?

Um, it was quite, I think it’s like one quarter of that. It was not big. It was like what? Eighth of the moon size?

Wyglądał trochę jak rogalik. [It looked a bit like a small croissant.]

Yes. But it … he didn’t look tasty.

Quiet laughter [long pause 15 seconds]

Have you seen a lunar eclipse?

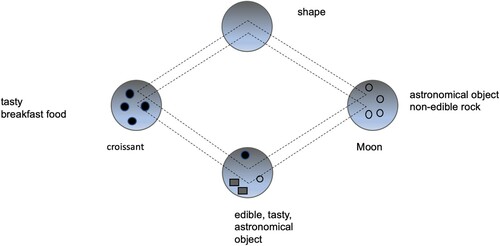

The Polish word rogalik (a Polish bakery item with a crescent shape) may trigger in the daughter’s mind the English mental space of ‘croissant’. Rogalik is often used in Polish to refer to the Moon’s shape. It is a conventional term and not particularly novel. However, here on hearing rogalik, Ania, who has lived all her life in Britain, draws on her experiential knowledge of eating croissants. This is possibly the most accessible knowledge structure she has for the concept rogalik. The resulting comic effect relies on the incongruity of the fact that we do not normally eat Moons. What is a conventional metaphor in Polish has become a novel metaphor in English. Although this cognitive analysis explains why this metaphor is funny, it ignores the symbolic power behind Ania’s use of Polish and English, in other words, Ania’s desire and potential ability to affect the participants’ emotions through her creative use of metaphor to achieve her social goals. Based on my schematic knowledge of the participants, and observation of the co-text, we have a mother-daughter interaction, in which the mother is quite assertive, and comes across as a ‘cultural carrier’ of Polish. Ania responds to her mother by humouring her through her use of metaphor, reinforced through negation ‘but, it … he didn’t look tasty’, that cancels out her mother’s claim that the Moon and rogalik look similar. The use of ‘he’ is also intriguing as it could be interpreted as an additional means of humouring her mother: The switch from the grammatically correct ‘it’ to the grammatically incorrect ‘he’ in English as it assigns gender, is noteworthy as it indicates a possible deliberate intention to borrow the Polish grammatical gender marking whilst speaking English to tease her mother (see analysis three for further discussion of gender markings).

This episode explores how Ania uses humour to release some of the tension and to possibly assert some of her own authority, through her developing symbolic competence. She does this by using her knowledge of the two languages and cultural domains creatively to form a type of ‘hybrid’ mixing, in her ongoing pursuit of her social goals in collaboration with others.

Analysis two: remembering the Moon with her brother

The next episode is the response given by the mother from family ‘B’ and her two children, Janek and Marta, after I asked them to describe the Moon. The episode begins with the mother interacting with Janek. She then directs her attention to Marta (7), who, according to the mother, is quite shy and does not like speaking Polish. In this episode, the mother takes the lead by first eliciting from Janek details about the Moon.

Odbija co? [Reflects what?]

Odbija od księżyca. [Reflects from the Moon.]

Ale co odbija? [But reflects what?]

Słońce! [The Sun!]

Nie, nie słońce, promienie słoneczne! [No, not the Sun, the Sun rays!]

Tak! [Yes!]

Promienie słoneczne idą od słońca, przechodzą aż do księżyca i odbijają się od jego powierzchni. Dlatego go widzimy tak? To o to chodziło. Ale on jest srebrny, dobrze, a jaki ma kształt? [The Sun rays travel from the Sun, approach the Moon and they are reflected from its surface. That is why we see the Moon, right? That’s what you meant. But is it silver, ok, and what is the shape of it?]

Okrągły. [Round.]

No, dobrze okrągły. Marta? A jaki kształt może jeszcze mieć księżyc? Marta, księżyc może być całkiem okrągły tak? I jaki jeszcze jest? Pamiętasz oglądaliśmy księżyc niedawno w ciągu dnia. [Ok, right, round. Marta? And what other shape can the Moon have? Marta, the Moon can be completely round, right? And what else? Remember we were watching the Moon recently during the day.]

Taki bananowy. [Sort of banana-shaped]

Może być jak banan, tak? [It can be like a banana, right?]

Może być taki … pół koła..kółka. [It can be like this … half a circle.]

Janek, Marta’s older brother, is the more talkative of the two children. He re-enters the conversation with ‘taki bananowy’ [sort of banana shaped] despite the fact the question was directed at the daughter. It’s not clear if the boy was present at the scene the mother is evoking but he provides a direct metaphor, flagged with ‘taki’ – ‘sort of’, that concurs with his mother’s question. This is a useful metaphor to use, as banana and the Polish banan are cognates and it is therefore easy for the daughter to understand. Also, Janek might think Marta is familiar with the cultural prototype of SHAPE OF THE MOON IS FOOD. Evidence for this is found three minutes later in the conversation when the mother and Janek refer to this cultural prototype through the linguistic realisation: ‘the Moon is like cheese’:

Takie dziury jakby prawda? Takie dziury w serze czasami się tak robi, że księżyc się tak rysuje, że wygląda jak ser. [Like holes, right? Like cheese holes, sometimes people draw the moon like cheese with holes.]

Dlatego ludzie mówią, że księżyc to ser. ‘The moon just made of cheese’. [That’s why people say the moon is cheese.]

<laughing>

Aaa, bo ma takie dziury, prawda? [Aaa, because of the holes, right?]

Finding Janek’s response credible, the mother re-uses ‘the Moon is a banana’ metaphor in the next turn. Taking creativity to be the production of both a novel and useful entity as defined within some social context (Plucker et al., 2004, p. 90), this metaphor stands out to be creative in that it is novel in the sense that it is new to the discourse (it was not found earlier in the transcript) and it is perceived by the mother to be useful: she re-uses the metaphor in the following turn. It is also useful for Janek, as it may serve his personal desire to assert his own agency to gain recognition, but also to realise certain social goals, such as to please his mother, to support his sister by scaffolding the interaction, or even just to fill a gap in the conversation. With his creative use of metaphor, Janek’s demonstrates his developing symbolic competence, through his awareness of the effect of the language he uses, and thus earns and probably re-affirms his position in the family.

Analysis three: A man? No, it’s like a poshy lady wearing a silver dress!

The last analysis shows how the father and two children of family ‘A’, draw on their cultural knowledge to categorise the Moon according to gender. In the following analysis, the father’s perspective, which represents, here, the conventional cultural norms that he is part of, will be presented first, and then compared to the eldest daughter’s perspective.

The Moon was frequently referred to as an animate object throughout the interviews especially in passages in which the participants were talking about the Moon and the Sun together. By way of an example, the father in family ‘A’ said ‘I do tend to compare it with the Sun and I think I see it as a slightly passive entity’. Here, he uses the adjective ‘passive’ whose basic sense is: ‘accepting what happens without trying to control or change events or to react to things’ (Rundell & Fox, Citation2007). Personification results in this example because to be ‘passive’ is, according to this definition, the attribute given to an agent: only humans can accept and try. The personification is reinforced when the participant goes on to say ‘yeah, yeah it’s kind of a minor key if you like … a minor player’. The father then referred to the Moon and the Sun in terms of psychological traits:

Więc myśląc o opozycji pomiędzy słońcem a księżycem. Jeżeli myślę o księżycu to księżyc jest dla mnie bardziej podświadomością i tą sferą nieracjonalną, w przeciwieństwie do słońca, które jest bardziej racjonalne i bardziej związane z tym, co widać. To me it (the Moon) would symbolise femininity, feminine aspects of life. [So, when I think about the opposition between the Sun and the Moon. When I think of a Moon, the Moon is for me more like subconsciousness and this irrational sphere, in contrast to the Sun, which is more rational and more connected with what is visible.] To me it (the Moon) would symbolise femininity, feminine aspects of life.

Interestingly, when asked later in the interview, if the Moon was either masculine or feminine the father and the mother both replied, with certainty, that the Moon was masculine, whereas both of the children said that the Moon could be both masculine and feminine.

Oba. Zawsze.

[Both. Always.]

Dla mnie to jest mężczyzną, panem.

[For me it is a man, a sir.]

Because in Polish ‘księżyc’[the moon] is male gender.

I think it’s both because like when it’s like that {pointing to the children’s books about the Moon on the table}, like all the legend which we read. Um, they were all about a boy going to the Moon. But then when it’s like a full Moon or it’s normally it’s feminine because it’s like a poshy lady wearing, oh, silver dress from my books I read. So I remember, I just remember a lady on the front cover, like the lady like this silver dress and [inaudible].

Yeah, it’s definitely a masculine male.

Drawing on my own knowledge about the family dynamics and considering Ania’s age (10), hearing her parents making reference to this aspect of language knowledge might have triggered some resistance in Ania towards them. In response to her mother’s statement: ‘Because in Polish “księżyc” [the Moon] is male gender’, Ania shifts the conversation by not referring to a grammatical category but by referring to a book she has read. As Reid and Ng (Citation1999) note, a change in the topic in intergroup casual conversations indicates an attempt by the speaker to control the conversation. Her desire to take control may explain why she chooses to shift the topic towards her knowledge of books, to ascribe gender through the use of personification, instead of accepting the information provided by her parents.

Ania, then, builds on her younger sister’s position that the Moon can be ‘both [masculine and feminine] always’. Without acknowledging her parents’ claims that the Moon is masculine, Ania makes explicit reference to the [Polish] book and the symbolism in the book to explain her reasoning. She recognises a metaphorical connection between the Moon and a lady in a silver dress and uses the simile, ‘it’s like a poshy lady’ to justify that it can be feminine. Her response demonstrates an ability to reflect on the non-arbitrary nature of the metaphor by reflecting on her social and sensorimotor experiences. This ability to reflect on the meaning-making process is further evidence of her developing symbolic competence (Kramsch, Citation2006). Although her parents do not explicitly acknowledge her response, I, the interviewer, respond to Ania two lines later with ‘Oh that’s interesting!’. With this comment, I see Ania’s response as legitimate and as a credible source of information. It is not just the words which hold symbolic power, but the credibility the speaker holds due to their social position (Bourdieu, Citation1991, p. 170; Kramsch, Citation2020, p. 6). I viewed Ania during the interview as an expert in Polish, a position she may not frequently hold in the eyes of her parents.

Discussion and conclusion

Recent studies on intercultural understanding of transnational children in home and school contexts have shown that these children play an active role in their own and the other interlocuters’ socialisation process often through creative means (Said & Hua, 2017; Wei, Citation2014). By negotiating their way in and across cultural and linguistic landmarks, transnational children develop strategies and competencies that go beyond that of achieving efficiency and clarity in communication to ones which involve an understanding of the meaning-making process itself; its symbolic competence (Kramsch, Citation2006, Citation2020). Whilst all humans have developed this competence through navigating their way around different registers, and are in this sense ‘multilingual’ (Kohl & Ouyang, Citation2020), transnational children’s position as re-interpreters of two (or more) languages appears, as is shown in this paper, to amplify this competence. Although hitherto transnational studies have highlighted and convincingly demonstrated transnational children’s ability to affect change, their focus on solely the social dynamics of the interactions limits their scope in understanding the conceptual work taking place to bring about these changes. Despite the small data set and the difficulties, at times, in capturing and representing the context, this paper set out to contribute to these discussions by providing a cognitive-discursive account of these processes.

The analysis in this paper aimed to demonstrate how Polish-English transnational children use language, in particular metaphors, to bring about change in family interviews when talking about the meaning of the Moon, an elusive object of deep significance to all cultures. Seeing these changes as a collaborative effort of pursuing one’s own as well as others’ social goals, I have adopted the notion of symbolic power (Bourdieu, Citation1991; Kramsch, Citation2006, Citation2020) to frame the changes taking place during family interactions. Although there exist moments of collaboration and at times tension in all families, my findings have set out to show how this power game plays out and is reflected in the interactions held in multiple languages spoken by transnational families. Transnational family members may be perceived within their family to know aspects of the host and heritage cultures and languages in different ways than other families, which can lead to new role reconfigurations and potential tensions. These points of tension surfaced in my data, for example, with Ania in collaboration with others using her knowledge of Polish and English to create language (it … he didn’t look tasty; like a poshy lady) to tease and humour her parents. Noteworthy, were the several moments of co-operation, for example, in episode two, where Janek assists his mother with her elicitation.

Although I anticipated the participants to use metaphor in the interviews, I had not anticipated the extent to which the children would use metaphor so creatively to achieve certain social goals. Despite the small data set, and a limited number of participants with this analysis I explored how and why the children created this new metaphorical language to respond to the situation they were in, a key aspect of the concept of symbolic competence (Hult, Citation2014; Kramsch, Citation2006). This paper also reflected an important shift in our understanding of metaphor use in multilingual contexts. The creative metaphors analysed in this paper could have been interpreted as errors and might have been framed therefore as ‘problems in need of remedy’ (MacArthur, Citation2016, p. 133), if interpreted against native speaker norms. However, by taking a cognitive-discursive approach, language use can be viewed more positively, as being examples of ‘hybrid’ metaphors (MacArthur, Citation2016, p. 133). This finding supports what others have noted, that adopting strict native speaker norms can be unhelpful when analysing speakers of multiple languages (Seidlhofer, Citation2001). Framing the metaphors as hybrids enabled me to see the metaphors as transcultural meaning-making tools to bring about change to the children’s social position.

I finished my analysis by drawing attention to how Ania’s credibility as an expert in Polish was seen through the interviewer’s eyes. To me, a non-Polish speaker, she had earned the status of an expert, not only through her understanding of Polish but also her developing symbolic competence. In a country in which bilinguals are often portrayed as a problem, this short analysis provides some further evidence, that transnational households can provide rich linguistic tapestries that afford symbolic competencies and linguistic creativity that should be valued in schools and in the wider society. The wider implications of this study’s findings are that transnational children can be seen as assets. Yet, the question remains whether these competences are transferable to other contexts, if the children are unaware that they have them. And, if the children do not have the opportunity to critically reflect on them, would these transcultural competences lay dormant and eventually cease to exist.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Creative Multilingualism team for supporting my work with the AHRC’s Open World Research Initiative fund. I am also very grateful to the families I interviewed, to Aneta Marren’s encouragement, and guidance with the Polish, to Furzeen Ahmed and Ian Cushing who have supported me through their critical engagement of my work, and to the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sally Zacharias

Sally Zacharias is a lecturer in educational linguistics and teacher education in the School of Education at the University of Glasgow, UK. Her research interests draw on cognitive frameworks and discourse studies to investigate the development of abstract concepts in pedagogical and home settings. Her fields of research include cognitive linguistics, metaphor, intercultural understanding, and multilingualism. She delivers language awareness sessions for pre- and in-service subject teachers.

Notes

1 In metaphor studies, it is convention to represent the conceptual metaphor with small capitals (see e.g. Kövecses, Citation2010).

References

- Bailey, E. G., & Marsden, E. (2017). Teacher’s views on recognizing and using home languages in predominantly monolingual primary schools. Language and Education, 31(4), 283–306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2017.1295981

- Boers, F. (2003). Applied linguistics perspectives on cross-cultural variation in conceptual metaphor. Metaphor and Symbol, 18(4), 231–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327868MS1804_1

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Polity Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryceson, D., & Vuorela, U. (2002). The transnational family: New European frontiers and global networks. Berg.

- Cameron, L., & Maslen, R. (2010). Identifying metaphors in discourse data. In L. Cameron & R. Maslen (Eds.), Metaphor analysis: Research practice in applied linguistics, social sciences and the humanities (pp. 97–115). Equinox Publishing.

- Chamberlain, M., & Leydesdorff, S. (2004). Transnational families: Memories and narratives. Global Networks, 4(3), 227–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2004.00090.x

- Coffey, A. (1999). The ethnographic self. Sage.

- Copland, F. (2015). Case study two: Researching feedback conferences in pre-service teacher 430 education. In F. Copland, A. Creese, F. Rock, & S. Shaw (Eds.), Linguistic ethnography: Collecting, analysing and presenting data (pp. 89–116). Sage.

- Cornips, L., & Hulk, A. (2008). Factors of success and failure in the acquisition of grammatical gender in Dutch. Second Language Research, 24(3), 267–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658308090182

- Dakin, J. (2017). Incorporating cultural and linguistic diversity into policy and practice: Case studies from an English primary school. Language and Intercultural Communication, 17(4), 422–436. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2017.1368142

- Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (2002). The way we think: Conceptual blending and the mind’s hidden complexities. Basic Books.

- Fogle, L. W., & King, K. K. (2013). Child agency and language policy in transnational families. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 19(1), 1–25.

- Gavins, J. (2007). Text world theory: An introduction. Edinburgh University Press.

- Gibbs Jr, R. W. (2020). The particularities of metaphorical experience: An appreciation of Fiona MacArthur's metaphor scholarship. In A. M. Piquer-Píriz & R. Alejo-González (Eds.), Metaphor in foreign language instruction (pp. 17–35). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Hult, F. M. (2014). Covert bilingualism and symbolic competence: Analytical reflections on negotiating insider/outsider positionality in Swedish speech situations. Applied Linguistics, 35(1), 63–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amt003

- Jerram, L. (2017). Museum of the Moon Official Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3YDOmKezwsI

- Kohl, K., Dudrah, R., Gosler, A., Graham, S., Maiden, M., Ouyang, W. C., & Reynolds, M. (2020). Creative multilingualism: A manifesto. Open Book Publishers.

- Kohl, K., & Ouyang, W. C. (2020). Introducing creative multilingualism. In K. Kohl, R. Dudrah, A. Gosler, S. Graham, M. Maiden, W. C. Ouyang, & M. Reynolds (Eds.), Creative multilingualism: A manifesto (pp. 1–23). Open Book Publishers.

- Kövecses, Z. (2005). Metaphor in culture: Universality and variation. Cambridge University Press.

- Kövecses, Z. (2010). Metaphor: A practical introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Kövecses, Z. (2015). Where metaphor comes from: Reconsidering context in metaphor. Oxford University Press.

- Kramsch, C. (2006). From communicative competence to symbolic competence. The Modern Language Journal, 90(2), 249–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00395_3.x

- Kramsch, C. (2011). The symbolic dimensions of the intercultural. Language Teaching, 44(3), 354–367. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444810000431

- Kramsch, C. (2020). Language as symbolic power. Cambridge University Press.

- Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, fire and dangerous things. What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago University Press.

- Littlemore, J. (2019). Metaphors in the mind. Cambridge University Press.

- Low, G. (2020). Taking stock after three decades: ‘On teaching metaphor’ revisited. In A. M. Piquer-Píriz & R. Alejo-González (Eds.), Metaphor in foreign language instruction (pp. 37–56). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Luykx, A. (2005). Children as socializing agents: Family language policy in situations of language shift. In ISB4: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism (Vol. 1407, p. 1414). Cascadilla Press.

- MacArthur, F. (2016). Where languages and cultures meet: Mixed metaphors in the discourse of Spanish speakers of English. In R. Gibbs (Ed.), Mixing metaphor (pp. 133–154). John Benjamins.

- MacKay, D. G., & Konishi, T. (1980). Personification and the pronoun problem. Women’s Studies International Quarterly, 3(2-3), 149–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-0685(80)92092-8

- Moon, R. (1998). Fixed expressions and idioms in English: A corpus-based approach. Oxford University Press.

- Parreñas, R. (2005). Long distance intimacy: Class, gender and intergenerational relations between mothers and children in Filipino transnational families. Global Networks, 5(4), 317–336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2005.00122.x

- Phipps, A., & Fassetta, G. (2015). A critical analysis of language policy in Scotland. European Journal of Language Policy, 7(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3828/ejlp.2015.2

- Plucker, J., Beghetto, R., & Dow., G. (2004). Why isn’t creativity more important to educational psychologists? Potentials, pitfalls, and future directions in creativity research. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 83–96. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.gla.ac.uk/10. 1207/s15326985ep3902_1

- Reid, S. A., & Ng, S. H. (1999). Language, power, and intergroup relations. Journal of Social Issues, 55(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00108

- Renzaho, A. M. N., Dhingra, N., & Georgeou, N. (2017). Youth as contested sites of culture: The intergenerational acculturation gap amongst new migrant communities – parental and young adult perspectives. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0170700. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170700

- Rundell, M., & Fox, G. (2007). Macmillan English dictionary for advanced learners (2nd ed.). Macmillan Education.

- Safford, K., & Drury, R. (2013). The ‘problem’ of bilingual children in educational settings: Policy and research in England. Language and Education, 27(1), 70–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2012.685177

- Said, F., & Zhu, H. (2017). ‘No, no Maama! Say “Shaatir ya Ouledee Shaatir”!’ Children’s agency in language use and socialisation. International Journal of Bilingualism, 23(3), 771–785. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006916684919

- Scottish Government. (2020). Pupil census. Supplementary statistics. https://www.gov.scot/publications/pupil-census-supplementary-statistics/

- Seidlhofer, B. (2001). Closing a conceptual gap: The case for a description of English as a lingua franca. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11(2), 133–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1473-4192.00011

- Sharifian, F. (2011). Cultural conceptualisations and language: Theoretical framework and applications. John Benjamins.

- Sharifian, F. (2013). Cultural linguistics and intercultural communication. In F. Sharifian & M. Jamarani (Eds.), Language and intercultural communication in the new era (pp. 60–82). Routledge.

- Skrbiš, Z. (2008). Transnational families: Theorising migration, emotions and belonging. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 29(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07256860802169188

- Stockwell, P. (2020). Cognitive poetics: An introduction. Routledge.

- Wei, L. (2014). Negotiating funds of knowledge and symbolic competence in the complementary school classrooms. Language and Education, 28(2), 161–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2013.800549

- Werth, P. (1999). Text worlds: Representing conceptual space in discourse. Longman.

- Zacharias, S. (2019). What can we learn from studying multilingual moon idioms and stories? Creative Multilingualism. https://www.creativeml.ox.ac.uk/blog/exploring-multilingualism/what-can-we-learn-studying-multilingual-moon-idioms-and-stories