ABSTRACT

This article focuses on a case study of English language teachers, who are asked to teach intercultural communication to mixed classes of local and international students in Chinese Higher Education, although they do not specialize in this complex field. They were interviewed to find out about their experiences and perceptions of this ‘improvised’ Intercultural Teacherhood. The study shows that their engagement with intercultural communication differs while the presence of international students has a major impact on all the teachers’ identity and sense of legitimacy. The paper ends on recommendations for (research on) preparing teachers to teach IC.

Tässä artikkelissa keskitytään tapaustutkimukseen englannin kielen opettajista, joita pyydetään opettamaan kulttuurienvälistä viestintää suomalaisten ja kansainvälisten opiskelijoiden Kiinan korkeakoulussa, vaikka he eivät ole erikoistuneet tähän monimutkaiseen alaan. Heitä haastateltiin kokemuksistaan ja käsityksistään tästä “improvisoidusta” kulttuurienvälisestä opettajuudesta. Tutkimus osoittaa, että heidän sitoutumisensa kulttuurienväliseen viestintään eroaa toisistaan. Kansainvälisten opiskelijoiden läsnäololla on suuri vaikutus kaikkeen opettajien identiteettiin ja legitiimiyden tunteeseen. Artikkeli päättyy suosituksiin (tutkimukseen) opettajien valmistamisesta opettamaan IC.

Introduction

Internationalization is often seen as a positive multifaceted phenomenon in today’s accelerating globalization (de Wit & Altbach, Citation2020). In Higher Education (HE), internationalization, in its complex forms (e.g., study abroad, internationalization at home, distance education), has become the norm and gives out ‘good points’ for international rankings (Lim & Øerberg, Citation2017). In order to deal with the changes triggered by this global phenomenon, teaching (about) interculturality appears to have become the sine qua non of HE around the world. As such HE teachers and scholars from different disciplines are often required to teach it in the fields of applied linguistics, intercultural encounters, communication studies and even health care (amongst others, see Tournebise, Citation2012).

This article focuses on the experiences of teachers of interculturality in Chinese HE. Through the help of China’s economic rise and the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative since 2013, the internationalization of Chinese HE has also become a major trend (Tian et al., Citation2020). According to the Outline of National Medium and Long-Term Education Reform and Development Planning (2010–2020) (Ministry of Education, Citation2010), in order to meet the complex requirements of internationalization, Chinese HE needs to focus on ‘solid English language skills, proficiency in language skills and cross-cultural communication skills, and knowledge of international economic and trade knowledge and norms’. These have accelerated the provision of intercultural education and training in China – universities being required to foster local and international students’ ‘intercultural awareness’ and enhance their ‘intercultural competence’ as learning objectives. Many courses and programs have been designed to fit under the labels of ‘intercultural’, ‘multicultural’, ‘bilingual’ teaching and learning, using English as an academic lingua franca in the classroom. However, the introduction of intercultural communication in China is often said to have been late compared to leading ‘Western’ universities and to lack paradigmatic and methodological sophistication, causing tensions and difficulties amongst teachers (Sun et al., Citation2021, p. 4). Tensions seem to come from the lack of university teacher preparation and professional development for interculturality. Teachers often need to ‘improvise’ by acquiring knowledge about the notion quickly, without being aware of the different kinds of ideologies prevailing in the field of interculturality (Dervin, Citation2014, Citation2016). For instance, globally dominating ‘Eurocentric’ / ‘Western’ / ‘Anglo-European’ models such as those of Byram (Citation1997) have been widely adopted by teachers and, sometimes, mixed together with e.g. Chinese philosophical perspectives (Peng et al., Citation2020; Sun et al., Citation2021, pp. 132–141). More critical perspectives such as non-essentialism and critical Chinese Minzu ‘minority’ perspectives are also used in China (e.g. Yuan et al., Citation2020). However, in general, the compulsory use of (mostly) ‘Western’ textbooks of intercultural communication in Chinese universities does not always facilitate renewed engagement with the notion of interculturality.

Globally, there appears to be a lack of systematic research on both HE teachers’ experiences of intercultural communication education and on their preparedness to teach it. The few previous studies from other countries highlight a picture of internationalization and intercultural communication education, which is not always promising. For example, Tange (Citation2010) shows that a shift from Danish to English, and having to teach multicultural classes, affects the quality and quantity of classroom IC in Denmark. Furthermore, Vaccarino and Li (Citation2018) discuss the lack of intercultural training of HE staff and suggest building internationalization capability through an intercultural communication workshop that encourages self-reflection. Likewise, in one of the only systematic review of intercultural communication education in higher education, taking the Finnish context as an illustration, Tournebise (Citation2012) shows that teachers lack formal training for teaching intercultural communication, seem unaware of the paradigms that they promote in their class and tend to blend in essentialist, culturalist, and critical perspectives. At the same time, these teachers seem to think that they share a common view about what interculturality is about (Tournebise, Citation2012). Tournebise’s study shows that her context of study is also unable to cater for coherent and systematic intercultural communication education in higher education, by adopting a neoliberal perspective, whereby teachers can teach what they wish, even if their perspectives can at times be on the verge of neo-racism (Tournebise, Citation2012).

Most of what these few studies show is that internationalization can be experienced negatively by HE teachers involved in IC teaching: lack of proper training and professional development, change of teaching language, introduction of different audiences, and curriculum changes. In the context of this study, China, we focus on teachers who represent the main contributors to IC teaching in higher education: teachers of the English language, who are non-specialists of IC but are asked to ‘improvise’ its teaching by delivering courses on IC as part of the English curriculum. Some factors have led to these teachers’ problems: they have to teach something new in English, a topic that they do not specialize in and they have to face a change of audience, from all Chinese to a mix of Chinese and international students. Very little is known of the experiences of these teachers.

A case study of English teachers working with students specializing in English at university is proposed in this paper. Not meant to generalize the specific experience of English teachers who do not specialize in IC in China (considering the complexity of Chinese HE), this article is based on data collected at a top university of finance, where IC is taught as a compulsory component in the English language curriculum. Using positioning theory and its interplay with teacher agency and legitimacy, as well as the notions of teacher identity and teacherhood, we are interested in their experiences of teaching IC within the framework of their institution internationalization. The teachers’ preparedness to teach IC is also of interest. Enunciative pragmatics (e.g. Angermuller, Citation2011), which is well-fitted for analyzing the teachers’ positioning and acts of agency, is applied to the data.

Teacherhood in the internationalization of higher education: framework for analyzing non-specialist teachers’ experiences of IC teaching

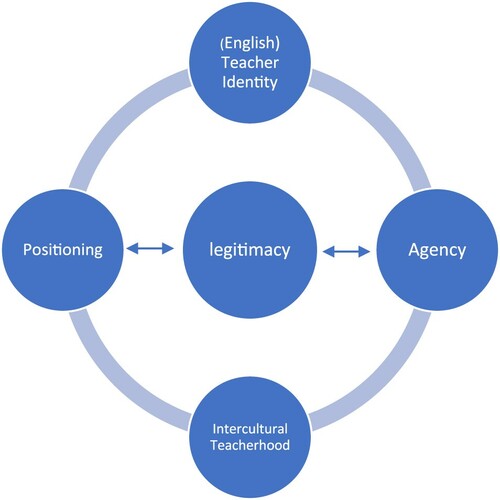

This section serves as a conceptual and theoretical background to the study. describes a framework containing two intersecting sets of concepts and notions that will be problematized here: A (continuum 1): English Teacher identity and Intercultural Teacherhood and B (continuum 2): Positioning, Legitimacy and Agency.

Continuum 1: English teacher identity and Intercultural Teacherhood

Considering the specific context and characteristics of our study, we first propose to focus on the continuum of (English) teacher identity and Intercultural Teacherhood. We argue that it is within this continuum that the English teachers under review experience teaching IC.

The concept of teacher identity has been discussed in the global literature for decades and has been explored in multiple ways. In a systematic review of the literature from the 2000s Beauchamp and Thomas (Citation2009) show that teacher identity refers to: first, teachers’ reinvention of themselves; second, the narratives they construct to describe their job; third, the discourses in which teachers are embedded, created by themselves or by others about the teaching profession; and fourth, the impact of various elements on teachers. For another scholar, Keller (Citation2017, p. 20), teacher identity represents, ‘The lived experiences, personal and professional beliefs, and dispositions that impact the personhood of a teacher’. What all these elements seem to indicate is that teacher identity is something fluid, adaptable and changeable, but of which teachers are in control, having been educated to sustain having to reinvent themselves (e.g. use of a new textbook, curriculum change), to face potential critiques from colleagues, parents and society at large.

As qualified teachers of English working with English majors in a prestigious institution, which composes a strong core English teacher identity for them (Beauchamp & Thomas, Citation2009), we argue that the teachers who are part of our study are ready to navigate through these different aspects, especially when it comes to teaching the English language and preparing students to communicate in the language. Going back to Keller’s (Citation2017) definition, English teacher identity here is thus understood as the experiences, beliefs and dispositions that reinforce teachers’ feeling of being ready, qualified and legitimate to stand in front of a class.

However, since our study examines an extreme case of change for teachers, triggered by internationalization of global and Chinese HE, we feel that another dimension, for which their English teacher identity may not prepare them (even in its very flexibility), needs to be added: Intercultural Teacherhood. As asserted in the introduction, in the Chinese context, it is common for teachers of English in higher education to teach some courses on IC since the topic is part of the curriculum. However English teachers, who might have majored in different fields such as language education, applied linguistics, translation, but also literature, are not systematically trained for IC during their university studies – or may not have any knowledge of IC at all. What is more no specific professional development courses on IC are provided when they start teaching in higher education. Therefore, teachers need to ‘improvise’ the teaching of IC, usually on the basis of a textbook and some extra materials they might have identified. Considering the complexity of the field of IC, with its many and varied ideological and political perspectives (Dervin, Citation2016; Dervin & Simpson, Citation2021; Holliday, Citation2010), having to teach IC could represent a non-negligible extra burden, which can question a strong (English) teacher identity.

In this paper, Intercultural Teacherhood thus comes as a complement, as an opposite pole to English teacher identity (while forming together a potential for ‘successful’ IC teaching), to analyze the experiences and preparedness of the teachers. To us, unlike teacher identity, teacherhood refers to having to teach something as non-specialists, exploring its characteristics, learning what it is about and finding ways to transfer knowledge to others. Although IC becomes part of the teachers’ English teacher identity somehow, Intercultural Teacherhood hints at the teachers’ potential lack of preparedness and thus unstable perceptions of who they are as English teachers who have to self-learn and improvise about the IC field. Intercultural Teacherhood represents a potentially disrupting part of teacher identity as it introduces ‘extreme’ change in the classroom for the teacher. One could argue, however, that, with time, experience, self-learning and cooperation with other teachers/specialists, Intercultural Teacherhood can become part of English teacher identity.

As we argue below, individuals constantly position themselves as ‘self-conscious as agents’ in their relationship to action and community (Harré, Citation1983, p. 108). Intercultural Teacherhood can have an influence on their active teacher identity confirmation and legitimacy. In the study, the participants are all highly qualified teachers of English, who need to juggle with an educational aspect which potentially threatens their English teacher identity – Intercultural Teacherhood.

Continuum 2: positioning, agency and the force of legitimacy

In the early years of teaching, a sense of competence and the recognition of competence by others is important to confirm and develop teachers’ identity (Lankveld et al., Citation2016). It is mostly through others (students, colleagues) that the quality of teacher identity is confirmed. In this section, we deal with three important interrelated phenomena that mediate continuum 1 (English teacher identity and Intercultural Teacherhood): positioning, agency and legitimacy. All three are other-centered, i.e. they process and result from the presence of others in the negotiating of English teacher identity.

We start with positioning, which can allow us to understand how positions and actions shape social structures as interlocutors engage in storylines (Davies & Harré, Citation1999). It is important to note that the term ‘position’ does not just refer to static roles, but also to ‘dynamic aspects of encounters in contrast to the way in which the use of “role” serves to highlight static, formal, and ritualistic aspects’ (Harré & Langenhove, Citation1999, p. 32). We thus hypothesize that positioning is an important mediator between English teacher identity and Intercultural Teacherhood.

Davies and Harré (Citation1999) theorized two types of positioning which will be important in our study: reflexive and interactive. Reflexive positioning relates to an individual assigning positions to themselves. Interactive positioning is an individual assigning positions to themselves while relating to others (Davies & Harré, Citation1990). These phenomena are multifaceted, dynamic, and conflicting at the same time. According to positioning theory (Davies & Harré, Citation1990) people constantly transform as the context changes in the process of interaction. However, when people do not accept or inhabit their interactively assigned positions, ‘they may attempt to reject them and/or impose their own. People thus claim the right or a duty to challenge their initial positioning by engaging in what Kayi-Aydar & Miller call ' repositioning’ (Citation2018, p. 81). They may also deny or allow others the right to challenge their interactively assigned positions. This repositioning process occurs in any changes of circumstances (Harré & Moghaddam, Citation2003), and is an ongoing negotiation of self and others, enabling possible actions in social interaction (Harré, Citation2012). The three processes of reflexive, interactive positioning and repositioning will allow us to examine how the English teachers whom we interviewed navigate the first continuum of English teacher identity and Intercultural Teacherhood.

Linked to positioning is the concept of agency. Agency is defined as ‘the capacity of people to act purposefully and reflectively on their world’ (Rogers & Wetzel, Citation2013, p. 63). For teachers, agency is their abilities, roles and beliefs to act in new and creative ways to make strong judgements and intentional actions according to internal contexts and external situational changes. Teacher agency is believed to be, amongst others, the capability to facilitate student learning (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015). Through agency, teachers can feel empowered, successful and even game-changing (Beauchamp & Thomas, Citation2009, p. 183). Agency can emerge from different factors (amongst others): strong pedagogical practices, pedagogical innovation, but also continuous professional development, collegiality with other teachers, institutional and educational policies (e.g. Biesta et al., Citation2017; Pyhältö et al., Citation2015). All these elements are systematically negotiated with and through others (colleagues, students, the institution, etc.) and contribute thus to various processes of positioning.

Teachers’ agency can be significantly constructed through active participation, cooperation and belonging. It can also be restricted when confronted with dilemmas, contradictions, incoherent educational visions, and uncertainty (Biesta et al., Citation2015). Our hypothesis is that Intercultural Teacherhood can potentially disrupt teachers’ agency, and thus have an influence on different actors’ reflexive, interactive positioning and repositioning in the process of teaching.

The last aspect of continuum 2 is legitimacy, which goes hand in hand with positioning and agency as a facilitating force for the English teacher identity-Intercultural Teacherhood continuum. This concept (which is often used as a synonym of authority or authenticity in educational research) has been widely defined in the context of HE However, to our knowledge, it remains unproblematized in relation to Intercultural Teacherhood. Gonzales and Terosky’s (Citation2016) article entitled ‘From the Faculty Perspective: Defining, Earning, and Maintaining Legitimacy Across Academia’ discusses legitimacy in the academic profession, which is very relevant for our context. Having used the method of conceptual interviews, to explore the meaning and conceptual dimensions of central terms used by their research participants, they interviewed faculty members about what it takes to be deemed legitimate in academia. The authors (Gonzales & Terosky, Citation2016) argue that legitimacy is ‘developed and reproduced by multiple, interrelated entities and actors that have an interest in the field, or more specifically, in maintaining historical, and thus familiar, arrangements of a field’. These can include, amongst others: colleagues but also disciplinary associations, accrediting agencies, ranking bodies (Gonzales & Terosky, Citation2016). Professional legitimacy, for Gonzales and Terosky (Citation2016), is also an important aspect of ‘endorsement’, which is unique to a professional field made with, for and by colleagues. Finally, cognitive work (knowledge and awareness of what is legitimate knowledge) is also included as a marker (Gonzales & Terosky, Citation2016). It is easy to see here how a sense of (il)legitimacy can influence positioning and agency, and, in the context of this study, make teachers oscillate between their English teacher identity and Intercultural Teacherhood.

In the following analysis we try to answer the following questions:

What are the English teachers’ experiences of teaching IC to English majors and how prepared do they believe they are to teach it?

How do they, as non-specialists of IC who have to deal with a complex, ideological and political field of research and knowledge, teach intercultural communication? Are there signs of professional illegitimacy, accompanied by potentially ill-adapted cognitive work, in how they discuss it?

How do positioning and agency (theirs and others’) influence their teaching of interculturality?

Research data

Research context and participants

This study was conducted with teaching staff from a School of Foreign Studies at a prestigious university specialized in finance and economics in China. Since very little research has been published in this context on the very topic of non-specialist English teachers’ experience of teaching IC, we have limited our study to the three English teachers from the School who teach IC. Since English teachers in Chinese higher education can have very different profiles (in terms of specialties, teaching, study abroad experiences), we feel that case studies can help us explore individual complexities of having to teach IC rather than try to generalize about these experiences. Participating in the study were three university teachers who represent altogether some of the diversity of English teachers of interculturality in China (Sun et al., Citation2021). Although they differ in age (30–50 years old), they all have in common being qualified English teachers for HE having studied abroad, and having had to shift from ‘just’ English language teaching to the teaching of interculturality to English majors (see ). There are slight differences in the names of the IC courses given by the teachers: Chinese Culture in the Context of Intercultural communication (Teacher 1) and Intercultural Business Communication (Teachers 2 and 3). All the courses are under the division of general education at the university and the medium of instruction required in the classroom is English. One course takes place over a semester of 15 weeks, with two hours teaching per week. Class sizes range from 20 to 50 students.

Table 1. Participants’ profiles.

All three teachers are qualified English teachers (tenured) from the School of Foreign Studies, which mainly focuses on English language teaching and research, English for Specific Purposes and foreign languages (Japanese and French). None of the three IC teachers majored in IC or related majors. Among them, two majored in Linguistics and applied linguistics. Teacher 1 has two PhD degrees (linguistics and education); Teacher 2 is a PhD candidate in English literature; Teacher 3 has a Master’s in linguistics and was an early PhD candidate in Intercultural Communication at the time of interviewing.

The class setting is the same for the three teachers: mixed classes, in which local Chinese students study with international students, who are exchange students mostly from European countries (duration of stays in China: half a year to a year). The ratio between Chinese and exchange students varies from around 3:1–1:3.

Data collection and analysis

A case study method was selected due to the exploratory nature of the research. Semi-structured interviews were organized so that the interviewer may ‘adjust prepared questions or bring in new questions’ (Gibson & Hua, Citation2016, p. 194) so as to probe answers to a question further. More space was also provided for the interviewed teachers to talk reflexively and elaborate on their experiences.

The data are from multiple sources collected for half a year, including interviews of the three teachers, fieldnotes and informal conversations with the teachers. Limited by space, this paper mainly presents our interpretation of data from the interviews, other data are supplementary if needed. Our interviews were conducted at the end of the semester, in quiet and private places such as the interviewees’ offices or meeting rooms at the university. The interviews were done in the interviewees’ L1 (Mandarin Chinese). We translated the data into English and polished, between us, some disputed translations a few times to minimize mistakes and misinterpretations. They were coded in English, while keeping a careful eye on potential issues of mistranslation.

In order to identify the teachers’ complex constructions of English teacher identity and Intercultural Teacherhood, by positioning themselves and putting forward their agency whenever legitimacy is presented, beyond mere descriptions on the surface of the data (mere ‘coding’, see Antaki et al., Citation2003), we make use of enunciative-pragmatics, a theory and method derived from the work of e.g. Benveniste, Culioli and Foucault but also Bakhtin’s Dialogism (Citation1981, Citation1984). This perspective emphasizes the heterogeneity of what people say, i.e. how when producing an utterance one ‘stages’ various speakers and voices and thus positions himself/herself (Angermuller, Citation2011, p. 2994). Bakhtin’s (Citation1984) approach focused on discourse, specifically, the use of multiple voices which he called polyphony within the multi-layered language system of heteroglossia. Heteroglossia, defined as ‘word-with-a-loophole’, ‘work-with-a-sidewards-glance’, ‘intentional quotation marks’ (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 274), expresses dynamic, ‘unitary’ language with centripetal and centrifugal forces as interlocutors interact with others in a given social context. The complex set of nested voices found in any utterance are called enunciators while the one who organizes these voices, the locutor (e.g. Maingueneau, Citation2007). Angermuller (Citation2011, p. 2997) explains: ‘In this view, utterances are viewed as ensembles of nested voices chained together in light of their argumentative value.’ In an enunciative analysis, we can ask the question of e.g. ‘who speaks in whose name against whom’ (Angermuller, Citation2011, p. 2997). Examining how the locutor animates the voices, the types of linguistic markers used to do so, can help us identify speakers, sources and contexts of enunciation as well as the way(s) the locutor positions themselves towards what the voices (the enunciators) are made to say, in other words how they construct discursive subjectivity and positioning (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Citation1980). These phenomena are referred to as polyphony (from Greek poluphōnia; polu- ‘many’ + phōnē ‘sound’). Our focus here is on the polyphonic organization of the English teachers’ utterances about their experiences of teaching interculturality as non-specialists. Who is made to speak by the teachers? For what purposes? What does the polyphony of their utterances reveal about their English teacher identity and Intercultural Teacherhood? How do they position them? Polyphonic plays of voices can be scrutinized by identifying linguistic markers of polyphony for instance in the teachers’ interviews. These include but are not limited to (e.g. Maingueneau, Citation2007):

pronouns such as the multi-referential third plural person we which can be used as an enunciative strategy to position oneself;

reported discourses that include in/directly the voice of heterogeneity in utterances through e.g. quotes;

passive voices which can ‘camouflage’ heterogeneity but reveal positioning;

the repetition of words;

modalities that indicate the subjectivity of the locutor (e.g. could, might, must …);

the use of negation that opposes different voices/enunciators (Angermuller, Citation2011, p. 2995).

The critical component of the form of discourse analysis that we use means that we examine how the use of these linguistic devices demonstrate ‘doing’ English teacher identity, positioning and agency, and linked them to potential empowerment and a sense of il/legitimacy in relation to IC teaching (see Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Citation1980).

Findings: non-specialist English teachers’ experiences of teaching IC and preparedness for it

In the analytical section, we first look at the way the teachers talk about themselves as non-specialists who have had to self-learn IC knowledge to pass it onto their students. The second section examines how the teachers have had to renegotiate three aspects of teaching while confronting their Intercultural Teacherhood: interacting with the students, social relations and pedagogical issues. It is important to note here that, since the field of IC is a complex one, with many and varied ideological approaches, our goal here is not to evaluate the teachers’ knowledge about IC or the effectiveness of their teaching but to examine their perceptions and experiences and preparedness of having to teach IC in their specific context.

Intercultural Teacherhood: a sense of illegitimacy?

In the interviews, all the participants positioned themselves clearly first and foremost as self-taught IC teachers because of the lack of IC expertise in their educational backgrounds. Looking at their fields of specialty, we note that Teachers 1 and 3 majored in linguistics and Teacher 2 in literature – both fields being somewhat distantly connected with IC. In the first excerpt, Teacher 1 appears to be clear about what she teaches while reflecting on the contents of her IC classes. As a reminder Teacher 1 is the most senior, having spent many years abroad. She is teaching a course entitled Chinese Culture in the Context of Intercultural communication:

| (1) | Teacher 1: My course is mainly Chinese culture, I divided the content into 15 sessions. The first session is the Confucius culture. The 2nd session is Lao Zi, and others include Tang Dynasty culture (prime time in Buddhism spreading), up to the Opening up to the outside world. When it comes to this, it can help students understand why China is so open and engaging in the Belt and Road Initiative. We were actually very open before. During the Tang Dynasty, many people visited China from foreign counties, mainly from European and East Asian countries. | ||||

In excerpt 1, the teacher as locutor seems to be in control of her enunciation: she speaks in her own name for most of the excerpt (use of first-person pronoun); she does not use any modality to modify what she is saying, indicating for example doubt or uncertainty (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Citation1980). In the second part of the excerpt, she does include others in her enunciative act (identifying as ‘we’-Chinese) and include linguistic elements that add to the quality of the statements made by her identification as We-Chinese: so in ‘China is so open and engaging’ and many in ‘many people visited China’. From Teacher 1’s excerpt, the direct link to IC theories and knowledge could appear to be very limited at first sight. Her focus appears to be on ‘Chinese culture’ (as in the title of the course she is teaching). The course seems to start from a historical perspective that presents the complexity of China, and the diversity and cultural mixing that has characterized it (e.g. the import of Buddhism; the Belt and Road Initiative). The content that she created is thus not ‘canonically’ based on intercultural theories or practices (e.g. Byram, Citation1997) but, in the end, it serves the same purpose, i.e. to show how a place like China that is often presented as a monolith, but is herself built up upon intercultural encounters, inside and with the outside (see Cheng, Citation2007). In the excerpt, the teacher speaks about what she teaches in a convincing and knowledgeable way, self-positioning and legitimizing her Intercultural Teacherhood in a good light.

Unlike Teacher 1, the two other teachers, who are younger, have less experience and teach a course entitled Intercultural Business Communication, appear to be less confident, positioning themselves in less coherent and compelling ways. Instead of presenting the content of what they teach, the other two teachers point out that they feel unqualified to teach IC because of their educational backgrounds. In excerpt 2, Teacher 2 presents this as being a common problem faced by teachers of English in intercultural communication education in Chinese universities:

| (2) | Teacher 2: it has a lot to do with my own knowledge system. I think I’m facing the same problems with many IC teachers from colleges and universities in China. We are not from IC major. We teach this course because we’ve majored in English language and literature, and we have had contacts with some foreign cultures and have had some experiences abroad. In fact, our knowledge system cannot adapt to the current [IC] development. If you want to teach in a better way, you need a better knowledge framework. Then you can conduct in-depth discussions on some topics. I personally feel that my knowledge in this area is lacking. | ||||

The except is constructed by means of different enunciators: at the very beginning and end of the except, the teacher as locutor is also the enunciator (‘I think’ … ‘I personally feel … ’). Yet, unlike excerpt 1, Teacher 2 as a locutor includes clear heterogeneity in her utterances (‘we’-many IC teachers) to describe the problems that she is encountering, somewhat ‘hiding’ behind them instead of placing herself on the line to present her problems (Maingueneau, Citation2007). The use of a generic ‘you’ before returning to the ‘I’ also seems to serve the purpose of protecting her face by not making it too personal – in other words: her illegitimacy as an IC teacher is shared by many others. If we look at the way Teacher 2 constructs her line of argumentation, we first notice that she positions her main problem as having the wrong ‘knowledge system/framework’, which means that, as a qualified teacher of English (her ‘knowledge system’, which is the basis of her English teacher agency), she feels unfit, or illegitimate, to teach IC. The generalizing sentence ‘we are not from IC major’, which is comforting this position by including ‘many IC teachers from colleges and universities in China’ (see ‘interactive positioning’, Davies & Harré, Citation1990), confirms clearly her opinion. She then manages to provide reasons behind the mismatch by including important aspects of her English teacher identity: they are language specialists, with experience of the ‘other’ (‘some foreign cultures’ ‘visits abroad’ in the excerpt). But, in the end, the coda of the quote reiterates that her Intercultural Teacherhood is illegitimate (see ‘teach in a better way’, ‘a better knowledge framework’, ‘my knowledge in this area is lacking’). The teacher’s position of illegitimacy returns during the interview from time to time.

When it comes to discussing their knowledge, Teachers 2 and 3 comment on the compulsory textbook of IC that they have to use in the course – which they did not choose themselves. Teacher 2 feels that the content of the textbooks that she has used differs from the complexity of the field of IC – showing awareness of potentially more critical voices:

| (3) | Teacher 3: My knowledge is mainly from textbooks. There is an invisible structure outside of textbooks, but I don’t know what it is. Textbooks have some flaws. I’m not in this major so I don’t know what a bigger picture is behind it. In addition, I don’t know some issues related to interculture in society, nor some hot topics. I’m not sure. | ||||

In excerpt 3, the teacher is somewhat transparent about her own position and does not ‘camouflage’ herself behind, e.g., generic pronouns or modalities that would transform the enunciative force of her utterances: she uses the present tense mostly, indicating certainty as to the problems in using the textbooks (Angermuller, Citation2011). Of interest too is the systematic use of the negative sentences such as I don’t know and I’m not sure, which shows that Teacher 3 does not try to hide her feeling of illegitimacy and lack of knowledge. It is clear from what Teacher 3 asserts that her awareness of her illegitimate position is based on the impression that her own knowledge about IC, which she gets from textbooks, is neither sufficient nor proper. For example, she mentions lacking knowledge about what she calls ‘the bigger picture’ and societal issues (‘related to interculture in the society’) of IC. This shows again that her English teacher identity is troubled by the awareness that she is given/imposed an extra aspect to this identity (Intercultural Teacherhood) that she cannot fulfill. Her agency appears negated by this fact and there is no attempt at repositioning herself as a competent teacher of IC during the entire interview (Davies & Harré, Citation1990).

What we see in this section is that the three teachers do not seem to teach what could be considered as ‘canonical’ IC knowledge (knowledge about China, textbook IC instead). This seems to be an issue for the younger teachers (2 and 3), which triggers a sense of incompetence and superficiality, while for the more experienced teacher, she tells us about the contents of what she teaches in a credible way, without showing signs of illegitimacy (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015). Besides content knowledge, Teachers 2 and 3 also worry about their? IC theory development and being insecure teachers, cognizant of a wider IC knowledge framework, who have in-depth knowledge (Gonzales & Terosky, Citation2016). In the way the teachers make us of polyphony and ‘manipulate’ different enunciators, one also notices differences: Teachers 1 and 3 are both frank about their good sense of competency (Teacher 1) and their sense of illegitimacy (Teacher 3); while Teacher 2 ‘hides’ partly behind other IC teachers to describe the problems she faces.

Multifaceted stress and pressure: others’ influence on Intercultural Teacherhood

Reading through the transcriptions of the interviews, one notices a large amount of discourses that position the teachers as experiencing stress and pressure. These include: extra workload, dealing with international students’ attitudes and behaviors as well as the fear of controversy in the classroom.

Increased workload due to the presence of international students

The first aspect that appeared in all the teachers’ interviews was discussing the increased workload due to teaching interculturality. For the first time in her interview, halfway through it, Teacher 1 discusses the issue of pressure and stress:

| (4) | Teacher 1: I think the amount of workload is more than other undergraduate classes. If the class is mostly composed of exchange students, then it requires definitely more time, because you’ve to prepare a lot. It’s stressful. The pressure is huge because you do not know what they will ask in the class. | ||||

Although most of Teacher 1’s interview revolves around her taking hold of the enunciative force by including herself directly in her utterances (Johansson & Suomela-Salmi, Citation2011), in this excerpt, apart from the first part of the first sentence, the rest of the excerpt is based on other enunciators such as a generic you and an indirect formulation excluding her own voice (‘if the class is mostly composed of … it requires definitely more time’) to discuss increasing stress. This excerpt is difficult to analyze because it is hard to tell who the teacher refers to here (both in Chinese and English). As such it is unclear if she includes herself in what she is saying or plays the spokesperson for other teachers, and if this reveals any sense of illegitimacy or lack of agency regarding this aspect of her Intercultural Teacherhood. Increased workload has often been reported in studies on internationalization of HE (e.g. Chen, Citation2019). It is important to note, however, that, whenever change appears, teachers will face extra workload, regardless of the context and the audience. This ‘troubling’ aspect of teacher identity is not limited to the context of internationalization.

Interestingly, while the other teachers focus mostly on content and course building when they discuss increased workload (see similar results in Chen, Citation2019), for this teacher, the pressure and extra workload seem to relate to one uncertain element: the fact that teachers find it hard to guess what international students might be asking during the class. As such, Teacher 1 does not characterize this openly as ‘uncertainty’ like the other teachers, but the use of the future tense in will (‘you do not know what they will ask in class’) hints at the unexpectedness of the teaching situation as being perceived as insecure (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Citation1980). Because of the generality of the utterances in the excerpt this might hint at concerns for herself and/or others about not being legitimate to answer the international students’ questions (Gonzales & Terosky, Citation2016). We come back to the issue of controversy in students’ questions in 4.2.3.

Fear of losing control

The second aspect that adds to the teachers’ stress in teaching IC relates to their fear of losing control of the class. For Skaalvik and Skaalvik (Citation2011) students’ behaviors in the classroom may constitute a source of teachers’ wellbeing and job satisfaction, which, in turn, could have an impact on the teachers’ agency maintenance. All three teachers complained about this.

Teacher 2 seems stressed by her perceptions of the attitudes and characters of international students. In what follows, she operates a comparison of the two dichotomized groups (locals and internationals), using clear stereotypes and representations, that interestingly go beyond the national as she groups all international students into one large ‘international’ group:

| (5) | Teacher 2: From the two semesters I taught, Chinese students are seldom late, they arrive early. Some of the homework that I let them do is basically done by them. Although exchange students are more active in the classroom, in fact, the disciplines and homework assignments I have arranged after class, including case studies, etc. Chinese students are often more serious. … I feel that the exchange students, their attitudes are relatively loose. | ||||

In the excerpt, the teacher takes responsibility for most of her assertions about both Chinese and international students enunciatively: the use of the present tense makes the utterance authoritative (Maingueneau, Citation2007). The assertions are modified slightly by some models such as ‘seldom’ (late), ‘often’ (more serious) for Chinese students and ‘relatively’ (loose) for international students – with the later increasing the negativity of the generalization. In this excerpt the teacher uses typical culturalist (culture as the sole explanation for people’s behaviors) and essentialist references to time use (late/on time), work ethics (serious/not), and class participation (active/passive) to compare people from different intercultural contexts (e.g. Piller, Citation2010). These dichotomies have been shown to create unfair ‘cultural’ hierarchies, stereotypes leading to prejudice and even racism (Holliday, Citation2010). By qualifying the local Chinese students as ‘seldom late’, serious with homework, she uses stereotypes that could divulge unfair superior qualifications. By making such statements, the teacher indirectly includes negative assertions about international students in opposition to Chinese students. The reference to being passive/active in class could, in a sense, counterbalance some of these representations, as an advantage to international students. What is revealed here is that the teacher uses herself very problematic ideologies about intercultural communication to voice her own stressful experience of IC teaching, and her ensuing low level of Intercultural Teacherhood, placing international students in potentially inferior positions (Piller, Citation2010). While taking control of the position of direct enunciator, she also reveals her potential biases against international students.

About passivity and activity in class, the same teacher recalls overhearing a conversation amongst some international students in her class, which seems to have embarrassed her and questioned her agency:

| (6) | Teacher 2: I heard a few international students chatting during the break, they were talking freely in English. I can understand. I heard that an international student said that he felt the Chinese students were too quiet. ‘The teacher had been pushing, urging them to talk, but [Chinese students] did not respond’. He said that he felt that he was very uncomfortable. Then I heard at that time, and I felt very uncomfortable too. … I think the words of these students at that time still hurt me. | ||||

Using both direct and indirect quotes from a male student, thus making him direct enunciator of the negative utterances that will end up ‘hurting her’ (Angermuller, Citation2011), the teacher describes how he had commented on the fact that Chinese students did not participate in class, even if the teacher had been trying to motivate them to talk. Interestingly, Teacher 2 seems to have taken this very personally as if the student were attacking her. Her evaluation is very emotionally marked, suggesting that this perceived incompetence has an influence on her teacher identity. Her emotions are enunciated directly through the use of the first-person: ‘I felt very uncomfortable too’ and ‘I think the words of these students at that time still hurt me’. By uttering his words, which the teacher heard, the core of her English teacher identity, beyond Intercultural Teacherhood here, is felt as being targeted (Keller, Citation2017). This might also have added to her sense of pressure and stress when working with mixed groups.

Facing controversies in the classroom: adding to a ‘weak’ sense of Intercultural Teacherhood

The final element of this section relates to an important component of IC teaching: controversies. Most international students who come to China often start their study experiences with stereotypical views on themselves and the Chinese, but also on Chinese society and politics (Du et al., 2018). China Angst, or divided feelings about the position of China in the world today, has had a large influence on foreigners’ views on these issues (McCarthy & Song, Citation2018). IC classes are one of the only contexts in China, where international students can discuss their perceptions of China, ask questions and potentially revise their representations. The participants of our study all discuss this aspect of IC teaching to a mixed audience. The teachers all mention topics that were contained in the questions they have had from international students, which they find somewhat challenging: The Cultural Revolution, China Taiwan and the role of women in Chinese society. In general, the teachers felt unprepared to face such situations, lacking agency and legitimacy to do so (Biesta et al., Citation2017). Their core English teacher identity did not even seem to represent support for dealing with this.

Teacher 3 expresses well how she faced this issue:

| (6) | Teacher 3: I think the most impressive thing is that they will ask you all kinds of questions during class and ask questions at any time [in the class]. I am not afraid of being asked, but I don’t know how to answer them. They would ask politically sensitive questions but I am not sure about politics. They asked about the Cultural Revolution … I didn’t know how to answer, except to say, as far as I know … or personally speaking, that was something. I could only personally answer like this. | ||||

Teacher 3 takes over the enunciation by putting herself forward here, stating directly both her confidence and awareness of her lack of knowledge about certain controversial issues (‘I am not afraid’; ‘I could only personally answer’; ‘I don’t know’ repeated twice) (Maingueneau, Citation2007). She even inserts two direct self-quotes (‘as far as I know … personally speaking’), showing further self-confidence. Polyphony appears in the insertion of the students’ indirect voices in the repetition of the pronoun they + the verb answer – turning the utterances into some sort of indirect dialogue between the students and the teacher, i.e.: ‘they will ask you all kinds of question’; ‘they would ask politically sensitive questions’; ‘They asked about the Cultural Revolution’. At the beginning of the excerpt, the teacher summarizes what constitutes problems about these questions: first and foremost, they are multifaceted and come at unexpected times during the lessons, which creates added uncertainty for the teacher. After this claim, Teacher 3 positions herself positively (‘I am not afraid of being asked’), while admitting her lack of agency and legitimacy to answer some of the questions (‘but I don’t know how to answer them’). Interestingly, as we shall see for the two other teachers, Teacher 3 demonstrates that she has thought of a strategy that indicates reflexivity and an awareness of the subjective aspect of answering politically flavored questions in education, especially in relation to IC. Using the aforementioned self-quotes (‘as far as I know … or personally speaking’), her strategy reveals an approach to interculturality which could be considered as critical since the teacher is telling the students that her answers to controversies are based on her own perceptions – and that other Chinese may not necessarily provide them with similar answers (e.g. Piller, Citation2010). This also helps her to make the students reflect on both their own representations of the elements they are asking about, and on the fact that interculturality requires criticality and reflexivity – controversies are neither perceived nor addressed the same way by an entire people and answers need to be unpacked. Through this answer, the teacher shows that her Intercultural Teacherhood, although presented as limited by herself, could be based on the epistemology of critical interculturality (e.g. Holliday, Citation2010), whereby one refrains from generalizing and makes clear that one’s perceptions and explanations are based on one’s subjectivity – without her being aware of it.

Teacher 1 also shares strategies that she has used to answer the students’ questions. Her strategy is that of the ‘mirror’ (Dervin & Yuan, Citation2021), i.e. to help the students compare critically their representations of China to other contexts:

| (7) | Teacher 1: I told them to view things from another angle, some media may be one-sided and one thing is exaggerated. … I gave them another example, which is the Paris [Yellow vest] demonstrations, the yellow vest demonstrated had lasted for several weeks. The Chinese media also had the same [one-sided], which is the angle of the camera to shoot. We [Chinese journalists] shot the fire burnt by the parade from an angle close to the fire, the flame seemed like burning the whole building. In fact, [flame] was far, like a pile of trash, a little bit. | ||||

Apart from the beginning of the excerpt that contains two elements showing that the teacher is directly responsible for the enunciation (‘I told them’; ‘I gave them’), the rest is based on an enunciator represented by the (Chinese) media demonstrating how they manipulate images (Maingueneau, Citation2007). The shift to the direct actions from the media could serve as convincing validation for her Intercultural Teacherhood. Her comment here is based on a critique of the media and on how they might report from biased perspectives. At the time of the interview, protests (the so-called yellow vests movement) were taking place in France and the teacher used this to show how Chinese media may misrepresent what was happening. She mentions the subjective use of the camera by reporters to make things look worse (fire everywhere). By so doing, the teacher makes an important indirect link to, e.g., Critical Media Literacy (CML), which Wilson (Citation2012) sees as central in intercultural dialogue. CML is defined as ‘the ethical use of media, information and technology’ (Wilson, Citation2012, p. 16). What Teacher 1 shows is that she is preparing the students for an important component of intercultural learning (critical literacy, see, e.g., Urlaub, Citation2013), although she may not be aware that this is part of it. She concludes the topic by saying: ‘There is no special way to deal with these challenging questions, no’ she somewhat confirms that she is not aware of that. There thus seems to be a mismatch between her actions and claims about Intercultural Teacherhood and what it could be about.

Discussion and conclusion

Based on a case study at a specific (top) university in China, this article examined the experiences of and preparation of non-specialist teachers involved in IC teaching. Our interest was in how these teachers deal with the continuum of teacher identity (in the field of English language education) and Intercultural Teacherhood, a newly added component to the latter, deriving from internationalization of their institution. The use of enunciative pragmatics (Angermuller, Citation2011) in the paper appears to be fruitful to offer a fine-grained analysis of how the teachers’ and other actors’ positioning and agency contribute to negating and/or confirming their Intercultural Teacherhood. The notion of Intercultural Teacherhood represents a major addition to try to make sense of English teacher identity in turbulent times of change triggered by internationalization.

The three participating teachers were somewhat different in describing, discussing and re-negotiating Intercultural Teacherhood during the interviews. Since they had different profiles, teaching and study abroad experiences, our results are meant to highlight the complexity of their experiences of teaching IC as non-specialists and should thus not be generalized to the thousands of Chinese teachers of English in higher education, who are themselves extremely diverse. The study shows that two of the teachers feel unprepared and somewhat illegitimate to be teaching the subject, for different reasons and in different ways. This was often reflected in the way they either constructed their utterances in distanced ways (letting polyphony take over, moving away from agency) or by taking the responsibility for enunciation (direct use of ‘I’ without any use of modalities of, e.g., uncertainty) (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Citation1980). The senior teacher seems to be in control of this position, integrating it somehow into her English teacher identity. Enunciatively she demonstrated ‘control’ over what she said, relying mostly on personal voices. Only when she seemed to be the spokesperson for other persons, did she include other enunciators (‘we’ as IC teachers). We should bear in mind that teacher 1 was involved in a course about Chinese culture, while the other teachers were teaching intercultural business communication. This might influence the teachers’ sense of agency and legitimacy and thus impact their Intercultural Teacherhood. In any case, what the teachers seem to have in common is that their English teacher identity is presented as disrupted by the very presence of international students in their classes. There were signs that their presence, alongside Chinese students, was seen as threatening the teachers’ English teacher identity.

The teachers’ experiences also reveal that they are very well aware of the difficulties they face, e.g. their lack of holistic and up-to-date knowledge about IC, which is often limited to the use of a textbook from the United States published in China (Teachers 2 and 3), containing mostly culturalist and essentialist perspectives about ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Holliday, Citation2010), and about dealing with controversial issues in class, based on international students’ socio-political representations of China (all teachers). However, although the teachers’ Intercultural Teacherhood might appear weak at times, it is interesting to note that they all show signs that, in fact, they seem to know how to deal with IC teaching, in critical ways, especially when they discussed the controversial issues that are introduced by the students in class. As such Teacher 1 refers indirectly to the method of critical media literacy when considering how she introduces critical discussions about (Chinese) media biases, while Teacher 3 demonstrates a good command of reflective and critical interculturality in dealing with questions about the Cultural Revolution, whereby she presents students with answers emphasized as being personal rather than generic and/or representative of all Chinese people. Yet the teachers don’t seem to be aware that these elements do in fact constitute important elements of IC teaching (see Piller, Citation2010).

The results from our study lead us to make the following recommendations for IC teaching and research, especially if taught by non-specialists (i.e. teachers who have no degree in IC or an IC teacher qualification). First, as we saw, the teachers of our case study majored in fields where diversity and communication are central (linguistics, education and literature). These are often seen as unrelated to IC teaching. Yet these fields deal with issues that can feed into new and different knowledge in the field of IC. It is thus suggested that teachers should start from their own relevant knowledge as an important interdisciplinary complement to IC before exploring the range of perspectives of interculturality available in the literature (from the ‘West’ and beyond). We argue that this could improve their sense of agency and help them deal with Intercultural Teacherhood in better ways. ‘Canonical’ Western knowledge about IC presented in textbooks cannot but be ideological and limited to a specific approach to IC, which may not suffice for the Chinese context (or any other context for the matter), especially in the internationalization of HE.

Our second recommendation is based on the fact that the teachers whom we have interviewed were somehow ‘forced’ to teach IC, because of their English language background. The curriculum and the use of a textbook (amongst others) were not negotiated by them but imposed top-down. This seems to contribute to their unstable Intercultural Teacherhood and the feeling of illegitimacy that some experienced. It thus appears legitimate to suggest that an inversed trend of teachers having their voice heard in the planning and management processes boost their agency and to better fit the important aspect of IC teaching in the era of accelerated internationalization.

Thirdly, during the interviews, the teachers discussed their need for further and systematic professional development, which is not always offered by the institution. For Biesta et al. (Citation2015, p. 624): ‘the promotion of teacher agency does not just rely on the individual teachers to their practice, but also requires collective development and consideration’. Professional development could help the teachers to feel more legitimate, especially if they could spend time, e.g. forming professional learning communities (Gorski & Parekh, Citation2020), identifying instructional, institutional, and structural challenges. Learning communities may provide a good place for teachers to share their views, experiences and knowledge with colleagues on a regular basis as well. Enabling them to update their interdisciplinary knowledge about IC (again a very complex field of knowledge) would also be useful for the teachers, and could allow them to navigate more smoothly the continuum of English teacher identity and Intercultural Teacherhood. In facing culturally diversified audiences in class, both teacher collaboration and support from the institution are necessary. For the teachers, reflexive tools and critical approaches are needed to ‘dig deeper’ (Dervin, Citation2017; Layne & Lipponen, Citation2016) in their repositioning and agency in reaction to changes in the classroom. For example, in a case study about a Canadian school district Miled (Citation2019) showed that teachers introduced to a form of ‘critical transformative multiculturalism’ may supported them well to handle the complexities of diversity and the changing demographics in class.

Internationalization (face-to-face and/or online) is here to stay in China and elsewhere. There is thus urgency to make sure that all teachers of IC (specialists and non-specialists) are heard around the world and that their needs are met, so that the IC work that they do can make a real difference. Further research on this topic is thus needed more than ever.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Huiyu Tan

Huiyu Tan is a lecturer in English at the School of Foreign Studies at Shanghai University of Finance and Economics. Currently a PhD student in education at the University of Helsinki (Finland), she teaches and researches intercultural communication education and internationalization.

Ke Zhao

Dr. Ke Zhao is a professor in the School of Foreign Studies, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics. Her research area includes intercultural education, language policy and technology assisted language learning.

Fred Dervin

Dr. Fred Dervin is a professor of Multicultural Education at the University of Helsinki (Finland). He is the author of more than 150 and 70 books in Chinese, English, Finnish, and French.

References

- Angermuller, J. (2011). From the many voices to the subject positions in anti-globalization discourse. Enunciative pragmatics and the polyphonic organization of subjectivity. Journal of Pragmatics, 43, 2992–3000. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2011.05.013

- Antaki, C., Billig, M., Edwards, D., & Potter, J. (2003). Discourse analysis means doing analysis: A critique of six analytic shortcomings. Athenea Digital: Revista de Pensamiento e Investigacion Social, 1(3), 14–35.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays (C. Emerson and M. Holquist, Trans). University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). Problems of Dostoevsky’s poetics (C. Emerson, Trans.; ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640902902252

- Biesta, G. J. J., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 624–640. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

- Biesta, G. J. J., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2017). Talking about education: Exploring the significance of teachers’ talk for teacher agency. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1205143

- Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters.

- Chen, R. T.-H. (2019). University lecturers’ experiences of teaching in English in an international classroom. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(8), 987–999. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1527764

- Cheng, A. (2007). Can China think? Publications du Collège de France.

- Davies, B., & Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1990.tb00174.x

- Davies, B., & Harré, R. (1999). Positioning and personhood. In R. Harre & L. v. Langenhove (Eds.), Positioning theory (pp. 32–52). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Dervin, F. (2014). Exploring ‘new’ interculturality online. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14(2), 191–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2014.896923

- Dervin, F. (2016). Interculturality in education. A theoretical and methodological toolbox. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dervin, F. (2017). “I find it odd that people have to highlight other people's differences – even when there are none”: Experiential learning and interculturality in teacher education. International Review of Education, 63(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-017-9620-y

- Dervin, F., & Simpson, A. (2021). Interculturality and the political within education. Routledge.

- Dervin, F., Du, X., & Härkönen, A. (Eds.) (2018). International Students in China: Education, Student Life and Intercultural Encounters Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dervin, F. & Yuan, M. (2021). Revitalizing interculturality in education. Chinese Minzu as a Companion. Palgrave Macmillan.

- de Wit, H., & Altbach, P. G. (2020). Internationalization in higher education: Global trends and recommendations for its future. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 5(1), 28–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2020.1820898

- Gibson, B., & Hua, Z. (2016). Interviews. In Z. Hua (Ed.), Research method in intercultural communication: A practical guide (pp. 181–194). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Gonzales, L. D., & Terosky, A. L. (2016). From the faculty perspective: Defining, earning, and maintaining legitimacy across academia. Teachers College Record, 118(7).

- Gorski, P., & Parekh, G. (2020). Supporting critical multicultural teacher educators: Transformative teaching, social justice education, and perceptions of institutional support. Intercultural Education, 31(3), 265–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2020.1728497

- Harré, R. (1983). An introduction to the logic of the sciences. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harré, R. (2012). Positioning theory: Moral dimensions of social-cultural psychology. In J. Valsiner (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of culture and psychology (pp. 191–207). Oxford University Press.

- Harré, R., & Langenhove, L. V. (1999). Positioning theory: Moral contexts of intentional action. Blackwell Publishers.

- Harré, R., & Moghaddam, F. (2003). The self and others: Positioning individuals and groups in personal, political, and cultural contexts. Praeger.

- Holliday, A. (2010). Intercultural communication and ideology. Sage.

- Johansson, M., & Suomela-Salmi, E. (2011). Enonciation: French pragmatic approach(es). In J. Zienkowski, J.-A. Ostman, & J. Verschueren (Eds.), Discursive pragmatics (pp. 71–98). Amsterdam.

- Kayi-Aydar, H., & Miller, E. (2018). Positioning in classroom discourse studies: A state-of-the-art review. Classroom Discourse, 9(2), 79–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2018.1450275

- Keller, T. M. (2017). “The world is so much bigger”: Preservice teachers’ experiences of religion in Israel and the influences on identity and teaching. In Handbook of research on efficacy and implementation of study abroad programs for P-12 teachers. IGI Global, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-1057-4.ch016

- Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. (1980). L'énonciation de la subjectivité dans le langage (Enunciating subjectivity in language). Armand Colin.

- Lankveld, T., Schoonenboom, J., Volman, M., Croiset, G., & Beishuizen, J. (2016). Developing a teacher identity in the university context: A systematic review of the literature. Higher Education Research & Development, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1208154

- Layne, H., & Lipponen, L. (2016). Student teachers in the contact zone: Developing critical intercultural ‘teacherhood’ in kindergarten teacher education. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 14(1), 110–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2014.980780

- Lim, M. A., & Øerberg, J. W. (2017). Active instruments: On the use of university rankings in developing national systems of higher education. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 1(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2016.1236351

- Maingueneau, D. (2007). Analyser les textes de communication. Armand Colin.

- McCarthy, G. M., & Song, X. (2018). China in Australia: The discourses of changst. Asian Studies Review, 42(2), 323–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2018.1440531

- Miled, N. (2019). Educational leaders’ perceptions of multicultural education in teachers’ professional development: A case study from a Canadian school district. Multicultural Education Review, 11(2), 79–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2019.1615249

- Ministry of Education. (2010). 国家中长期教育改革和发展规划纲要(2010-2020年) (Outline of the National Plan for Medium- and Long-Term Education Reform and Development). http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2010-07/29/content_1667143.htm

- Peng, R. Z., Zhu, C. G., & Wu, W. P. (2020). Visualizing the knowledge domain of intercultural competence research: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 74, 58–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.10.008

- Piller, I. (2010). Intercultural communication: A critical introduction. Edinburgh University Press.

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2015). Teachers’ professional agency and learning – from adaption to active modification in the teacher community. Teachers and Teaching, 21(7), 811–830. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.995483

- Rogers, R., & Wetzel, M. M. (2013). Studying agency in literacy teacher education: A layered approach to positive discourse analysis. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 10(1), 62–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2013.753845

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teachers’ feeling of belonging, exhaustion, and job satisfaction: The role of school goal structure and value consonance. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 24(4), 369–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2010.544300

- Sun, Y. Z., Liao, H. J., Zheng, X., & Qin, S. Q. (2021). Research on intercultural foreign language teaching and learning. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

- Tange, H. (2010). Caught in the Tower of Babel: University lecturers’ experiences with internationalization. Language and Intercultural Communication, 10(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14708470903342138

- Tian, M., Dervin, F., & Lu, G. (Eds.). (2020). Academic experiences of international students in Chinese Higher Education (China perspectives series). Routledge.

- Tournebise, C. (2012). The place for a renewed interculturality in Finnish higher education. IJE4D Journal, 1, 103–116.

- Urlaub, P. (2013). Critical literacy and intercultural awareness through the reading comprehension strategy of questioning in business language education. Global Business Languages, 18. Article 6. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/gbl/vol18/iss1/6

- Vaccarino, F., & Li, M. (2018). Intercultural communication training to support internationalisation in higher education. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 44, http://immigrantinstitutet.se/immi.se/intercultural/nr46/vaccarino.html

- Wilson, C. (2012). Media and information literacy: Pedagogy and possibilities. Comunicar, 20(39), 15–22.

- Yuan, M., Sude, W. T., Zhang, W., Chen, N., Simpson, A., & Dervin, F. (2020). Chinese Minzu education in higher education: An inspiration for ‘Western’ diversity education? British Journal of Educational Studies, 68(4), 461–486. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2020.1712323