ABSTRACT

The inclusion of intercultural communication and intercultural competence in English language education in Chinese Higher Education is now firmly established in the ‘National Standards’ (2020). In a post-project reflection, we explore the opportunities and challenges in co-constructing an interpretive (non-essentialist) approach to interculturality and the emergent pedagogic framework (theory, methodology, teaching materials) within a Chinese-European research project. While partners shared an enthusiasm to make the project successful, power relations, academic and professional expertise, and certain theoretical and methodological preferences challenged the co-construction of the framework. Thus, our reflections highlight tensions, challenges, and lessons learned which will inform future international collaborations.

中国教育部颁布的《国家标准》(2020)将跨文化交际和跨文化能力明确纳入高校英语语言教育之中。本文作者通过项目后的反思探讨了在共同构建文化间性的解释性(非本质主义)方法以及相应的教学框架(理论、方法、教材)中面临的机遇与挑战。期间,项目合作者均热切期待成功,但仍需要应对包括不同的权势关系、学术及职业的专业修养和对某些理论及方法的偏好等多方面的挑战。因此,作者的反思突出了合作过程中的冲突、挑战和经验教训,以期为未来的国际合作提供参考。

Interculturality has been gaining currency in China, particularly in the area of foreign language education. The cultivation of intercultural competences has increasingly been emphasised in contemporary education policy as China opens out and adopts an active role in global affairs (Jia et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, recent guidelines of the national Higher Education (HE) advisory boards have lent additional validity to this rationale. The National College English Teaching Advisory Board (Citation2014, p. 2020) re-stated the importance of ‘enhancing intercultural communication awareness and communication skills’ and ‘improving comprehensive cultural literacy’. And the National Foreign Language Teaching Advisory Board (MOE, Citation2020b) highlighted the need for systematic teacher training in intercultural communicative competences. This trend mirrors international developments, e.g, PISA’s 2018 Global Competence (PISA, Citation2021) assessment based on theories of intercultural competence; and within the pan-European context, the Council of Europe’s Research Framework of Competences for Democratic Cultures (RFCDC) (Citation2021) designed for its 47 member states.

Against this backdrop, the Resources for Interculturality in Chinese Higher Education (RICH-Ed) Erasmus+ projectFootnote1 (2017-2021) sought to develop a ‘training’ course to develop interculturality – consisting of intercultural teaching and learning activities – for language teachers and administrators in the context of internationalisation in China. Conceptually, the project sought to resist an ‘essentialist’ view of culture which, according to Holliday (Citation2000, p. 39), attempts ‘to fit the behaviour of people into pre-conceived, constraining structures’ where national cultures often become the main point of reference to interpret events and people’s behaviours. An essentialist view may also simplify intercultural communication to a set of skills and abilities pertaining to one cultural group which may lead to stereotypical interpretations of communication and behaviour, e.g. as exemplified in some intercultural competence models (see Spitzberg & Changnon, Citation2009, for an examination and evaluation of these models).

Instead, the project was underpinned by an interpretive approach to intercultural communication and intercultural learning. Drawing on social constructionism (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1966; Borghetti et al., Citation2015), this approach emphasises the multiple and relational nature of identity and culture; and the centrality of human experience, that is, how individuals make sense of the world they inhabit through their (intercultural) communication with others.

An interpretive approach also aligns with Holliday’s ‘small culture’ approach (Citation1999, Citation2013), which recognises the shifting nature of culture – not grounded in nation-state ideology, but complexity. Intercultural communication concerns individuals’ thought processes (e.g. introspection, self-reflection, and interpretation); individual agency, as communicators transgress, remediate, and renegotiate the rules established through everyday communication practices; and as a result, how individuals may critically (re-)evaluate representations of self and others (Holmes & O'Neill, Citation2012). This interpretive approach underpinned the rationale for the project, as formulated within the European Commission’s ‘capacity-building’ project guidelines.

The international, multilingual project was developed jointly among European and Chinese partners. The consortium consisted of approximately 20 Chinese researchers/teachers involved in English language education from five universities in China (two in the Northeast – Harbin and Jilin Universities, and three in the lower Yangtze River Delta – Hangzho Dianzi, Ningbo-Nottingham, and Zhejiang Wanli Universities) and seven researchers who were also teachers of intercultural communication from three European Universities (University of Bologna, Durham University, and KU Leuven, the lead institution).

But how is it possible to reconcile international and pan-European traditions and approaches with those extant and emerging in China and alongside the Chinese Ministry of Education’s recent initatives for intercultural competence development? How is it possible to construct a fluid, interpretive understanding of interculturality, rather than intercultural competence approaches that focus on ‘knowledge’ (of other cultures), ‘skills’ for intercultural engagement, and ‘attitudes’ (e.g. towards otherness) which can risk consolidation of national stereotypes and othering (Holliday, Citation2013; Citation2016)? And what tensions emerge in an international collaboration of researchers/teachers of intercultural communication when, together, they attempt to work together to create – or to co-construct – a resource for intercultural education in the Chinese context?

Our aim in this paper is to attempt to explore these challenges and tensions through post-project reflection, and highlight lessons learned as the project partners together attempted to co-construct an interpretive approach into intercultural education in China. In this project ‘co-construction’ meant sharing among all partners conceptual understandings of intercultural communication, and methods and resources for teaching it to create together (i) a framework of concepts that inform an interpretive approach to interculturality, (ii) a metholodogy, and (iii) activities (called ‘modules’ in the project) that can be used for teaching intercultural communication in Chinese HE classrooms.

We are guided by the following research question: RQ. What is the experience of co-constructing an interpretive approach to interculturality in HE in China among an international collaboration of researchers/teachers?

To answer this question, first we contextualise the study, highlighting recent reforms and policies shaping HE in China, particularly in English language education at the time when the RICH-Ed project was conceived and conducted, and where intercultural teaching and learning has been focused. Next, we describe the co-construction of the project and consortium membership. Then we turn to the research question to explore the processes we underwent in developing a framework for interculturality. From this analysis we draw conclusions on the complexities of implementing an interpretive approach to intercultural communication into HE in China.

Intercultural teaching and learning in China: national curriculum guidelines as institutional policies

The current focus on the intercultural dimension of English/foreign language teaching reflects to some extent China’s political economy (Jin et al., Citation2017) and the demand for intercultural and international talents for China’s persistent endeavour for rejuvenation. It also responds to the Ministry of Education’s (MOE) requirements for intercultural communicative competence-oriented English/foreign language teaching as stated in the national curriculum guidelines for both English (English majors) and non-English degree programmes (referred to as College English).

The recent National Curriculum Guide for College English (Citation2020a) has stipulated that intercultural communication be a key component of curriculum design within English language programmes, including English for General Purposes, English for Specific Purposes, and/or intercultural communication courses (MOE, Citation2014; Wang, Citation2016). For English majors, the National Standards (MOE, Citation2018) has listed intercultural communication to be part of core courses and compulsory to all students.

In response to the ‘National Standards’, the National Curriculum Guidelines for Undergraduate English Programmes (MOE, Citation2020b) was revised in 2020, providing an updated ‘blueprint’ for local performance of the interculturally-oriented curriculum in relevant programmes and universities. In both the ‘National Standards’ and the ‘Curriculum Guidelines’, intercultural communicative competence is defined explicitly as:

跨文化交际能力:尊重世界文化多样性,具有跨文化同理心和批判性文化意识;掌握基本的跨文化研究理论知识和分析方法,理解中外文化的基本特点和异同;能对不同文化现象、文本和制品进行阐释和评价;能有效和恰当地进行跨文化沟通;能帮助不同文化背景的人士进行有效的跨文化沟通 (MOE, Citation2020b, p. 95)

respect for the world's cultural diversity, having intercultural empathy and critical cultural awareness; having basic knowledge of intercultural theories and analytical methods, understanding the basic characteristics and similarities as well as differences between Chinese and foreign cultures; being able to interpret and evaluate different cultural phenomena, texts and artefacts; being able to communicate effectively and appropriately across cultures; being able to help people from different cultural backgrounds to communicate effectively. (our translation)

As a result of these reforms and curriculum changes, national and provincial funding schemes, symposia, new textbooks, and teacher training programmes have emerged, targeted at intercultural learning which is recognised as important part of humanistic education (Sun, Citation2015, Citation2016; Zhang, Citation2012) and aimed at developing interculturally competent global talents aligned to the strategic development of China under the framework of a community of shared future for humanity (see for example, Wang, Citation2018; Wang & Yang, Citation2021).

However, the ‘National Standards’ and the two curriculum guidelines only serve as general roadmaps, landmarked with basic requirements and principles. Without any given theoretical framework, the local operation of these official policies depends largely on the stakeholders’ own understanding and experiences of interculturality in the context of Chinese HE. Furthermore, the teaching objectives, curriculum, and standards for intercultural education are expected to conform to China’s national circumstances. The RICH-Ed project therefore operated during a crucial turning point for cultivating international/global talents and, in particular, intercultural English language education in China where informed and innovative pedagogy is much needed in a context of increasing scrutiny of teachers’ practices concerning how ‘interculturality’ is understood and represented and how those practices conform to current Chinese Communist Party ideology and political sensitivities (see Byram, Citation2020).

A review of intercultural learning in the Chinese context

The recent literature on interculturality by Chinese researchers and practitioners presents both concern and optimism regarding the integration of intercultural learning with English language learning. Concern is evidenced in Suo et al.’s (Citation2015) content analysis of 122 textbooks on intercultural communication, published between 1985 and 2014. They reported that teaching materials did not seem to be informed by theories of intercultural communication, and adopted a Euro/US-centric stance with little consideration of the local context and learners’ profiles.

An inventory of intercultural learning in Chinese HE undertaken within the project (RICH-Ed, Citation2021a) revealed different levels of experience and training (e.g. Zheng & Li, Citation2016); misconception of intercultural learning as intercultural knowledge and skills learning; misconception of intercultural communication as interaction between Chinese and foreigners/Westerners; failure to recognise the complexity and fluidity in intercultural encounters; and over-reliance on borrowed theories and practices from the global North in China. These misconceptions are also evidenced in the MOE (Citation2020a, Citation2020b) guidelines presented above. By contrast, the inventory also indicated a growing recognition among Chinese researchers of the importance of understanding culture as a dynamic and evolving process, recognising students’ autonomous agency and encouraging reflective and critical thinking (Sun, Citation2016); developing dialogic interaction amongst students, teachers, and texts as a basis for intercultural teaching and learning (Wang et al., Citation2017). This understanding of intercultural communication was also evidenced in new textbooks written in response to the new requirements of the National Curriculum guidelines (e.g. Jin & Cortazzi, Citation2011). For example, Sun’s (Citation2015) Think English series integrates critical thinking ability and intercultural learning with skills learning through the use of English.

Therefore, the RICH-Ed project came at a time when curriculum reform and policy change required greater preparedness by teachers and administrators. It also required new thinking concerning understanding of more fluid and co-constructed understandings of intercultural communication; the inclusion of the local context and its associated special needs; acknowledgement of the diversity within China itself, magnified by increasing rural-urban and north–south shifts and migration; recognition of education that embraces the Autonomous and Special Administrative Regions (SAR); and acknowledgement of China’s philosophical traditions in relation to its global ambitions.

Within this context, we describe the project proposal and consortium development. We then address our specific research question where we reflect on the challenges and tensions of co-constructing our interpretive approach (alluded to in the introduction) and the emergent RICH-Ed Pedagogic Framework.

The project proposal and consortium development

The idea for the project emerged in a 1-day workshop following the International Association for Languages and Intercultural Communication conference in Beijing in 2015 (Van Maele et al., Citation2015). The workshop was organised by Jan Van Maele (Belgium), based on an earlier project where he was a co-investigator (IEREST).Footnote2 Others present were the Bologna and Durham partners (Holmes and Ganassin), also co-investigators in IEREST; Song, from Harbin Institute of Technology (the third author); Wang from Hangzhou Dianzi University; and Dong from Nottingham Ningbo, all known to Van Maele and Holmes. The IEREST project was presented as an idea for developing intercultural materials for English language teaching in Chinese universities, and as an approach that resisted essentialist conceptualisations of culture evidenced in earlier Chinese textbooks and which the Chinese MOE was keen to move away from (as highlighted above).

In response to a call by the European Commission for European universities to engage in capacity building projects in developing countries, Van Maele then led the development of the proposal. While this conceptual underpinning made sense in response to recent MOE guidelines for intercultural learning in China, in writing the project proposal, Van Maele encouraged collaboration among all the partners in the co-construction of the proposal and activities (‘Work Packages’). At this point, other collaborators known to the group were included in the proposal writing. Thus, the project consortium of eight universities was formed, coalescing around the geopgraphical regions of the Yangtze River Delta (three universities), and the North-east (two universities).

While IEREST and its non-essentialist approach provided the foundation for the development of the project proposal, there was a deliberate attempt to involve all partners in co-constructing the conceptual and pedagogic framework, and associated materials and module development, as discussed next.

A description of the RICH-Ed pedagogic framework

The RICH-Ed Pedagogic Framework (REPF) (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) consists of a theoretical framework; a methodology underpinning the development of teaching materials; eight modules; learning objectives and learning outcomes; assessment of learning; and a glossary of terms. Here, we focus on the key concepts, the methodological underpinnings, and issues related to the assessment of learners’ intercultural communicative competence – the key components that shaped the development of the modules which came later.

Theoretical standpoints

The concepts underpinning the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) described below drew from the previous (IEREST) on which the European partners had worked together. They are also concepts familiar to them through their own research and teaching. As stated in the introduction, our understanding of interculturality and intercultural learning draws on social constructionism (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1966) and it underpins all the RICH-Ed modules. Within a social constructionist frame, intercultural communication is dialogic, and recognises the multiple and relational nature of identity, culture, language, and power in shaping shared human experience.

The REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) begins with a presentation of how ‘culture’ is understood in intercultural communication research and how such understanding is relevant to the wider Chinese socio-cultural context. Here, our concern was to move beyond dichotomies of ‘Chinese and foreign’ and ‘Eastern or Western’ to acknowledge the diverse nature of the Chinese context where different languages, cultures, and ethnicities, i.e. the 56 Mínzú民族 or ethnic groups are at play (Adamson & Feng, Citation2021; Ganassin, Citation2020). We drew on Holliday’s (Citation1999, p. 2013) ‘small culture’ lens to understand the shifting nature of culture, not grounded in nation-state ideology but in complexity. A small culture approach views society as comprising dynamic groupings of individuals formed through shared understandings, and where people move in and out of these groups and shape new groups within their ‘large culture’ or society (Holliday, Citation2013). Interculturality (in Chinese kuàwénhuà跨文化) is about how individuals interact with others in intercultural encounters – the spaces where people from different cultural, national, and social backgrounds engage and develop self-awareness and reflect on themselves (Holmes & O'Neill, Citation2012). Central to the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) is the idea that intercultural encounters can happen between people from the same country; for example, they can involve two Chinese people (e.g. one from Beijing, and one from the North-east of China). In such encounters people share similarities, but their different ‘small cultures’ (Holliday, Citation1999) and their different positions, understandings, or interpretations of an event are can be so salient that the encounters can facilitate intercultural learning. Intercultural encounters are also imbued with power: individuals may exert power over others – by what they say or do, or through interpersonal relations depending on one’s position within the family, group, community, or organisation, etc.

The anthropocosmic approach to interculturality (Jia et al., Citation2019; Jia & Jia, Citation2016), which draws on the Confucian tradition, represents a further key theoretical standpoint of the framework. Central to the approach is 仁 rén ‘humaneness’, or the ethic of ‘being for others’ and ‘being for both self and other’ (Tu, Citation2013). 仁 rén symbolises that a person can only grow, develop and establish him or herself in relation to and in interaction and integration with others (Jia et al., Citation2019). Overall, the anthropocosmic approach embraces a view of Confucianism as a resource for intercultural understanding with a focus on ensuring harmony of humans, nature, and the universe (Jia & Jia, Citation2016). As explained by Tu (Citation2013), Confucian humanism seeks an integration of body and mind, an interaction of self and community, a sustainable and harmonious relationship between human and nature, and a mutuality between the human heart and Heaven.

The REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) also draws on Byram’s (Citation1997, Citation2021) descriptive model of intercultural competence, and its five savoirs, to understand individuals’ communication with one another. Byram emphasises the importance of engaging, through a foreign language, in intercultural communication with interlocutors with different culturally influenced values, beliefs, and assumptions. The model was chosen for three main reasons. First, in common with the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b), the model draws on an interpretivist view of language and culture that is negotiated and performed in interaction. Second, it has had a considerable influence on language research, policy, and practice around the world, and in the recently developed ‘National Guidelines’, and it is potentially applicable outside of the European context where it has originated. Third, rather than explicitly focusing on language, the model points to the role of the intercultural speaker, the person who ‘has an ability to interact with ‘others’, to accept other perspectives and perceptions of the world, to mediate between different perspectives, to be conscious of their evaluations and differences’ (Byram et al., Citation2001, p. 5). This final point is particularly significant in our context. Although the project was developed against the backdrop of English language education in Chinese HE where assessment cannot be easily ignored, the modules are not specifically concerned with teaching or assessing (English) language; rather, they can develop intercultural learning more broadly.

Grounded in these understandings, the RICH-Ed framework represents the first notable effort to reconcile theories and methodologies for intercultural learning and education – broadly speaking – from Anglo/European and Chinese traditions. In the process of constructing the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b), we focused on synergies rather than on differences in the effort to create a coherent set of theory-informed modules for Chinese teachers and learners.

Methodology

The methodology of the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) draws on Kolb’s (Citation1984) experiential learning cycle which enables learners to come directly into contact with socially-constructed ways of engaging in intercultural encounters. Learners are facilitated to move from ‘concrete experience’ (i.e. exploring teaching materials), to ‘reflective observation’ (i.e. collective or individual reflection on a task), followed by ‘abstract conceptualisation’ supported by the teacher’s input and, finally, by ‘active experimentation’ where students are required to produce an output.

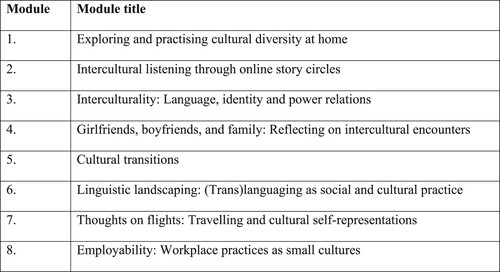

Inspired by Kolb’s (Citation1984), we developed eight modules () which included reading, interactive tasks, research tasks, and assessment. Each module included a handbook for teachers, and a student learning resource.Footnote3

Overall, the modules were designed to develop learners’ understanding of themselves and others through intercultural communication so that learners can recognise, understand, and interpret interactions with people who may come from different (national, cultural, social, educational) backgrounds to their own (Holmes & O'Neill, Citation2012). The modules were designed for teachers and students within Chinese HE, with a focus on providing intercultural learning for the majority of ‘home’ students who cannot access study abroad opportunities, and to encourage learners and their teachers to embrace diversity within, and thus problematise monocultural and monolingual ideologies.

Assessing intercultural learning

A key aspect of the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) concerns the assessment of intercultural learning which has been debated extensively (Borghetti, Citation2017; Deardorff, Citation2016). Borghetti (Citation2017) discusses a number of conceptual and ethical issues in relation to the assessment of intercultural competence (ICC), including: the weaknesses of the existing models of ICC with respect to assessment; the relationship between ICC and interculturally-competent performance; the context-based and relational nature of ICC; and the affective dimension of ICC and how this is problematic to assess. And Deardorff (Citation2016) highlighted the importance of a multi-pronged approach to assessment that was both top-down (teacher led) and bottom-up (student self- and peer-assessment), and included both quantitative and qualitative forms of assessment.

Given these concerns, three key principles informed the development of the assessment tools in the RICH-Ed materials: (a) an acknowledgment that all assessment tools have limitations; (b) assessment tools always need to be used in combination; and (c) the assessment process needs to include a mix of direct and indirect evidence (Deardorff, Citation2016). Qualitative methods that allow students to reflect on their learning (e.g. reflective journals, peer- and self-assessment, portfolio entries, and teacher observations) were prioritised. A set of explicit ‘learning objectives’ and ‘learning outcomes’ specific to each module respond to Deardorff’s (Citation2016) call for the articulation of clear learning goals and objectives.

Having contextualised the project, and described its co-construction, consortium membership, and its product – the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b), we now turn to our guiding research question: What is the experience of co-constructing an interpretive approach to interculturality in HE in China among an international collaboration of researchers/teachers?

Co-constructing the interpretive approach within the project consortium

Here, we present our reflections on the first year of the project (Ganassin et al., Citation2019), a crucial part of the project where consortium members dialogued, shared knowledge and experience, and collaborated to shape the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b). According to Schön (Citation1983), reflective practice involves professionals becoming aware of their implicit knowledge base and learning from this experience. Reflection enabled us, as researchers and authors, to develop our own awareness and reappraise our approaches, decisions, methods, and challenge assumptions as we engaged in the development of the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) during this first year, and in this post-analysis, to reflect on this practice with one another. We (the three authors) dialogued with one another about key moments of shared and unshared understandings and misunderstandings that occurred in this first year. These emerged into key themes upon which we wrote more detailed reflections, followed by further checking and elaboration of one another’s written interpretations.

Our reflections, presented as a narrative, are the result of this shared, co-constructed process. They coalesce around six key themes: membership and formation of the partnership at the outset; shared and unshared theoretical perspectives; developing a project methodology; a focusing on ‘interculturality at home’ in module development; assessing intercultural learning; and power relations.

Getting started: membership and formation of the partnership

From the outset, all the Chinese partners were enthusiastic about the RICH-Ed project. International collaboration has been encouraged and welcomed by Chinese universities, and the more internationally recognised the grants and partner universities, the more support the universities are likely to give, as evidenced in the Chinese-hosted consortium meetings and training events throughout the project. However, China is diverse, and so are its institutions, as represented in this consortium which included universities from the three tiers of the education sector, all with their own institutional requirements and priorities. Despite overall enthusiasm toward the project, the different levels of prior engagement in the teaching and researching of interculturality and unexpected changes of participants affected the establishment of a core team, and thus, shared understanding, especially in the early stages.

The structure in Chinese universities divides English language education into English majors and non-English majors, the former more academically trained in theory and research methods through their masters and doctoral education, often obtained abroad, and the latter more skills oriented. However, more recently, a PhD is required, regardless of the teaching focus. The consortium was constructed in such a way so that more experienced partners (from China and Europe) could ‘build the capacity’ of those institutions. However, the participants who were teachers of non-English majors, as well as being early career researchers, tended to lack support from their institution.

Shared and unshared theoretical perspectives

Among the partnership there were diverse understandings of interculturality. At the first meeting at Ningbo-Nottingham University, it became apparent that the participants had different motivations and expectations due to their personal academic backgrounds, professional interests, and roles in engaging with and and/or managing the project work. Lack of conceptual knowledge, formal training, and teaching experience in intercultural communication, particularly among early career researchers/teachers and teachers of non-English majors in China (who are expected to teach according to pre-defined teaching plans, rather than research or introduce ideas about interculturality) may have led to later difficulties when they were required to produce module materials informed by the conceptual and pedagogic approach. Research undertaken in China suggests that teachers are not necessarily familiar with theoretical conceptions of interculturality, and may view cultural content in terms of ‘knowledge’, of traditions and customs, history, geography or political conditions (Byram, Citation2020; Qin & Holmes, Citation2022; Yan, Citation2014). Limited opportunities for training also mean that some teachers may not be aware of developments in the literature, and if so, are unsure about which intercultural approach to adopt or how to implement it in their classroom (Sun et al., Citation2021). English language education in China is examination-oriented, and teachers tend to attach greater importance to teaching knowledge about language rather than the intercultural aspects (Qin & Holmes, Citation2022).

Given these differences and limitations, some of the Chinese colleagues appeared to be more interested in learning through participation in a project partnership, rather than leading on and co-constructing intercultural materials.

Some tensions immediately became apparent. First, within the consortium we faced difficulty in co-constructing an appropriate interpretive approach that included theory, methodology, and pedagogy. In the first meeting, the European partners outlined the theoretical basis of the interpretive approach in IEREST, and invited partners in HE in China to present their conceptual and pedagogic approaches to teaching intercultural communication. Some of the partners were using interpretive approaches underpinned by ethnographic and experiential methods, as adopted in the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b); others preferred to work with more essentialist theoretical constructs linked to intercultural communication found in the earlier literature (e.g. the cultural dimensions approaches developed by Hofstede, Citation1980; and Hall, Citation1976), and where national identity is prominent. Inevitably, positivist theoretical perspectives emerged in the development of the modules that focused on dichotomies of East and West, thereby neglecting the diversity within China. More importantly, the content and focus did not represent the ambitions of the project, nor the requirements of the Chinese MOE (as discussed earlier). Thus, later, the partners worked together to revise and ensure alignment with the interpretive approach in the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b).

A further contention arose around the inclusion of the anthropocosmic approach. As the approach had been developed by one of Song’s colleagues at Harbin University (Jia et al., Citation2019) and they had been working on the concept with their students, it seemed appropriate to include it. Although the anthropocosmic approach is rooted in the Chinese Confucian tradition and Confucian humanism, (Jia & Jia, Citation2016), it shares similarities with other Western theories of intercultural communication (e.g. see Ferri, Citation2014) in that it views intercultural dialogue as an ethical way of being human. Furthermore, part of the anthropocosmic approach aligns with social constructionism (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1966). Both of these theoretical stances recognise the importance of interrelationality, interdependence, and interconnectedness in intercultural communication, and the often-resulting blurring of all boundaries. The anthropocosmic approach incorporates important philosophical concepts inherent in Chinese social life and identity that require acknowledgement and understanding in intercultural communication in the Chinese and global context. There was some concern among the European partners that the theoretical framework, despite strong efforts to be inclusive when discussing approaches, was appearing Eurocentric in its foundations, and thus, including the anthropocosmic approach would help to address this concern as well as appearing to introduce a Chinese dimension to the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b).

Only in the latter stages of the project did it become apparent to Holmes (through personal communication with a Chinese partner) that not all Chinese partners agreed to its inclusion. First, some questioned if a new theory, which had not been empirically tested, should be included. The anthropocosmic approach is new in the field of interculturality in China, despite its links to Confucianism, and New Confucianism (Tu, Citation2013) which is gaining attention in China and internationally. And how the concept of 仁ren, ‘humaneness’ might be understood in intercultural theory beyond the anthropocosmic approach, and outside of the Chinese context, is unclear. Second, is it even appropriate to introduce an anthropocosmic approach into the REFP (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b)? And third, should it be prioritised over other established and emergent approaches developed by other Chinese scholars? Unfortunately, these questions were not shared or discussed among the partners, and therefore need further exploration to understand the relevance of the anthropocosmic approach to intercultural theory and encounters. Thus, integrating this approach – for all partners involved in module development – appeared to be difficult, and only one module included it (RICH-Ed, Citation2021c).

Developing a project methodology

While our first meeting (in Ningbo) centred on developing the theoretical framework, the second meeting, three months later in Harbin, focused on methodologies. The meeting began with a workshop given by the Bologna partners (who had led on the development of the IEREST activities). They began by introducing Kolb’s (Citation1984) experiential learning cycle which had underpinned the IEREST activities. The Bologna team were careful to point out that this was intercultural learning, not ‘training’ as it was important to share and understand the principles and approaches, rather than ‘instruct’. However, IEREST was devised for a different purpose – study abroad. With its focus on experiential learning, it eschewed solid, stereotypical approaches to language, culture, and identity; and adopted decentring methodologies and pedagogies that place the learner centre-stage through co-constructed, dialogic, experiential, and multimodal ways of understanding intercultural communication (Beaven & Borghetti, Citation2016; Borghetti et al., Citation2015).

Similarly, and as part of the co-construction process, the Chinese partners introduced the methodologies they used for teaching intercultural communication. These included both interpretative and essentialist approaches to understanding interculturality (the former focusing on experiential learning activities, and the latter on activities that focused on knowledge and invited understandings of language and culture according to cultural dimensions approaches.)

All partners appeared to agree to the inclusion of Kolb’s (Citation1984) experiential model because, regardless of its European origins, it challenges teacher-centred approaches to education commonly found in Chinese classrooms, and places learners at the centre of learning processes; it aligns with the theoretical orientations of the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b); and, moreover, it had worked well within the IEREST pedagogic framework. Although some of the Chinese partners were familiar with Kolb’s experiential learning approach, it is not commonly seen in Chinese textbooks and not practiced in an assessed classroom context. Therefore, implementing the methodology into the pedagogic tasks provided a learning opportunity for some.

Developing an ‘interculturality at home’ focus

As many students in China do not have access to study abroad and international work placement experiences (Ganassin et al., Citation2021), consortium partners wanted to embed ‘interculturality at home’ within the materials in order to promote intercultural learning within local contexts, and more ambitiously, to nurture a cadre of global talents to help realise China’s international ambitions (in response to the MOE’s guidelines). By focusing on interculturality at home and through the teaching of English, we wanted to extend our reach to all English language learners in HE in China, beyond those global elites in China who may envisage English language learning for purposes of business, tourism, and study abroad (O'Regan, Citation2014). Initially, it became important to emphasise that nation states are diverse, and that China is no exception; intercultural encounters can be as much intra-national as international. This was a stance we encouraged (see, for example, modules 1, 2, and 3).3 That educational systems strive to present a unified linguistic, historical, and cultural narrative is not unique to China, but the pervasive force of such narratives in educators’ minds can be difficult to counter.

Yet, as the project was ‘capacity building’, these challenges were, in a sense, part of the project remit. However, these wide conceptual, professional, and practical discrepancies in understanding intercultural communication and how it might be taught in HE in China created challenges around establishing a shared understanding of the goals of the project and the interpretive approach. Such differences also affected the building of rapport and trust among some of the partners, and willingness and/or capacity to dialogue openly about the directions of the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b). Thus, in this first year, the meetings were characterised by shared and unshared understandings, approaches, and practices regarding researching and teaching interculturality.

Assessing intercultural learning

The centrality of assessment in the Chinese educational context had arisen in discussions throughout the development of the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b). How to assess intercultural learning became a focus in the third meeting (in Hangzhou). The consensus among the partners was that an assessment element should be included as teachers and their learners would expect it. The partners agreed that, in the spirit of the REPF and as reflected in the learning objectives and outcomes in the modules, the forms of assessment should be holistic and qualitative. They should acknowledge learners’ value-informed responses and emotions in intercultural encounters, and that intercultural learning is a lifelong process which entails the recognition and appreciation of learners’ and others’ multiplicities, and accommodates variation in learners’ responses to the complexity of interculturality. Thus, all of the modules included an assessment element that had a formative focus rather than summative. As Borghetti (Citation2017) argues, all teaching should be assessed: ‘if IC(C) development is one of the educational aims of language learning and teaching, it appears logical enough to assess language students’ intercultural learning as well’.

Although the RICH-Ed project was developed against the backdrop of English language education in Chinese HE where assessment cannot be easily ignored, the modules are not specifically concerned with teaching or assessing (English) language; rather, they aim to develop intercultural learning more broadly and in contexts beyond language learning and focus on the complexity of intercultural encounters, and socially-constructed understandings of self and other in dialogic encounters. However, how language skills and interculturality might be assessed within the framework are important considerations that require further exploration, especially given that the teachers may be implementing the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) within English language education, in accordance with requirements from the ‘National Guidelines’ (2020).

Power relations in the project

From the start, the project leader, Van Maele, highlighted to all involved that, although the project falls under the umbrella of ‘capacity building’ (acknowledging the funding call), he emphasised that the project was collaborative, drawing on the expertise and experiences of all the partners. Unsurprisingly, not all partners fully understood or shared expectations, had the requisite knowledge and experience, or agreed on proposals as the project unfolded. At times, there were open disagreements, and at other times, disagreement was conveyed privately. Ideologically, politically sensitive issues (e.g. concerning how some ethnic minorities in China access education) could not be discussed openly. There were also some unshared understandings and misunderstandings about the HE system in China, specific institutional contexts in a diverse educational structure within China, how teaching is planned and conducted, and misunderstandings concerning the preparedness and expertise of teachers in intercultural matters. Differing power positions (linked to experience and institutional affiliation), perceived roles in the project, and knowledge (linked to education and training in intercultural communication) affected how individuals within the project engaged. While every attempt was made at meetings to share knowledge and co-generate material, individuals made their own choices about their perceived role in the project and how much they were willing or able to contribute. After all, the project had to cater to multiple levels of researcher/teacher knowledge, experience, and capacity within HE in China.

Despite these spoken and unspoken differences, the focus on shared goals and tasks, and finding common ground to ensure the project’s success overrode individual differences. In co-constructing the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b), the partners were encouraged to work together (through carefully selected diverse groupings) and support one another, and through dialogue and written feedback on module development in the spirit and ethos of the project.

To conclude this section, while we have highlighted some of the key challenges and tensions that emerged in the co-construction of the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b), we cannot address them all within one paper. Next, we reflect on these major challenges and tensions to summarise lessons learned and provide insights for future international collaborations.

Lessons learned: insights for future international collaborations

From the six themes discussed above, several insights emerge. First, partnership formation is crucial in international projects. While a diverse and large membership offers the potential for rich engagement and intellectual flourishing in the co-construction of an interpretive approach to interculturality, the challenges should not be underestimated. Our project benefited from stability, an ambition to create something worthwhile, and a shared desire to succeed; contextually, it focused on two geographical regions, and partners came from all three tiers of universities in China, resulting in extreme differences in theoretical understanding and academic expertise. Among the European partnership, understanding of the Chinese context differed. These diverse academic, professional, and teaching experiences meant that not all members shared equally the desire – or capacity – to participate and contribute. Groupwork was not always as effective as expected, with responsibilities and contributions affected by power positions, perceived academic expertise, and a commitment to finalising the end product: the REPF RICH-Ed, Citation2021b), and modules with teacher/student guidelines. As with all projects, sensitive ideological and subjective differences had to be negotiated, and while open and frank dialogue may be a goal, contextual factors, and interpersonal and power relations may prevent its realisation. These factors require careful consideration when identifying partner institutions and their members to ensure effective and balanced working conditions and relations.

Second, the intention to introduce an interpretive theoretical approach, pedagogy, and materials into intercultural education was grounded in an assumption – from the project’s inception (and as rooted in the IEREST project) – that such an approach was both necessary, important, and perhaps even novel in the Chinese context. Had these assumptions been teased out at the start of the project among participants, such discussions may have led to improved understanding of various power positions, and greater respect for diverse academic and professional knowledge and expertise. Notwithstanding these assumptions, the project focus was both appropriate and timely, given the mandating of intercultural learning within English language education in the new ‘National Standards’ (2020).

Third, the project must be recognised for its inherent weaknesses. The REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) may not have been sufficiently developed to support teachers in implementing interculturality into their teaching, and support learners in the classroom, especially in the English language context. For example, it may have been over-ambitious to combine into one document theoretical concepts, methodology, learning objectives and outcomes, assessment, and learning materials, rather than as separate items, e.g. a textbook on intercultural communication theory and its application to teaching, accompanied by a separate resource book (the modules), and with more extensive teacher and student guidance. Teachers may need more support to understand the theories, their interlinkages, and how to apply them in the classroom to support the students’ understanding and learning. This challenge is not unique to the Chinese context; teachers are by nature practitioners, and do not have the training or time to focus on theory. The success of the RICH-Ed materials, teachers’ implementation or them, and students’ experiences of their intercultural learning will require further empirical investigation. Our overall interpretive approach, including the anthropocosmic dimension, will need deeper investigation in relation to other theories of interculturality developed by other scholars in China.

Finally, the final 16 months of the project unfolded under Covid conditions which precluded face-to-face meetings. Thus, the work undertaken in the first year was important relationally in enabling members to become familiar with one another and understand (to some extent) different working practices. The European partners were able to travel to China and experience the context first hand, and the partners from China visited the universities of Durham and Bologna. These connections sustained the final 2 years of the project (which included a 6 month extension) conducted online. However, the absence of face-to-face dialogue did curtail serendipitous conversations where these reflections could have been explored, and where the theoretical framework, its links to the pedagogy and modules, and its relevance in the Chinese context could have been worked on in greater depth. Instead, our communication was confined to 2-hour online meetings bi-monthly, and two 3-day online consortium meetings which combined synchronous and asynchronous sessions and tasks among different partners and in different time zones. Feedback was also achieved via word documents and emails. Therefore, the opportunity to collect in-depth reflections from other project members at the end of the project was missed.

Beyond these issues, our study has its own limitations, thus raising further directions for research. First, while we have attempted to provide our reflection on this international collaboration, we are aware that other project members may not share our views. Second, to some extent, social constructionism (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1966) allowed us to introduce other concepts that have built on the theory (e.g. Byram, Citation1997; Holliday, Citation2013; Citation2016). This bricolage approach – that inspires creativity and originality, making possible new ways of putting things together (Ganassin, Citation2020; Levi-Strauss, Citation1962) – could potentially be useful in shaping the REPF (RICH-Ed, Citation2021b) in other contexts. Furthermore, our research is not grounded in any nation-state ideology, and we specifically focused on rejecting ‘East’/‘West’ binaries; yet, we faced ideological, experiential and practical challenges in the development of our material. Future research might explore the transferability of the approach in other national contexts, or perhaps where similar ideologies are in operation. It would be useful to build in dialogue and reflection from all partners and participants as part of this process, including dialoguing with teachers and students in the field to gain their understanding of the usefulness of the approach and materials in their classroom practices.

In conclusion, Fantini (Citation2020, p. 56) warns that ‘from a North American and English point of view, we alone cannot definitively determine something about a concept that requires multiple views and applies to people of multiple language-culture backgrounds’. In this sense then, an international collaboration appears beneficial. Despite the caveats revealed, our study has shown how theoretical, ontological, and political divergences, misconceptions, and misunderstandings – alongside convergences and co-construction – can inspire new approaches and pedagogies for intercultural education. The analysis of our attempt here offers inspiration for future researchers to explore elsewhere and in their own contexts, and through international collaborations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Prue Holmes

Prue Holmes is a Professor of Intercultural Communication and Education, and Director of Research at the School of Education, Durham University, UK. Her research areas include critical intercultural pedagogies for intercultural communication, language and intercultural education, and multilingualism in research and doctoral education. Prue has worked on several international projects. She was the former chair of the International Association of Languages and Intercultural Communication (IALIC) and she is the lead editor of the Multilingual Matters book series Researching Multilingually.

Sara Ganassin

Sara Ganassin is a Lecturer in Applied Linguistics and Communication at the School of Education Communication and Language Sciences, Newcastle University (UK). Sara’s research interests include internationalisation of higher education and mobility, migrant and refugee communities, and Chinese heritage language learning and teaching. She has been involved in different European projects on internationalisation and intercultural learning. Sara has also worked for seven years in the voluntary sector as project coordinator and researcher with migrant and refugee women and young people.

Song Li

Song Li is a professor of English and Intercultural Communication at the School of International Studies, Harbin Institute of Technology (China). She holds a PhD in English Language and Literature from Shanghai International Studies University (China). Her teaching and research focus on an intercultural communicative approach to foreign language education, intercultural language education, English as an international language and global intercultural communication from an anthroponomic perspective. She has been principal investigator in several national and international research projects on interculturality in Chinese higher educational contexts.

Notes

1 The Erasmus+ project, Resources for Interculturality in Chinese Higher Education (RICH-Ed) (585733-EPP-1-2017-1-BE-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP), is funded under the ‘Cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices: Capacity building in Higher Education’ (KA2) initiative.

2 Intercultural Educational Resources for Erasmus Students and their Teachers (IEREST) [527373-LLP-1-2012-1-IT-ERASMUS-ESMO] provided the impetus for the RICH-Ed project.

3 Modules (including teacher and student versions) can be downloaded at http://www.rich-ed.com/index.php?s=/List/index/cid/15.html.

References

- Adamson, B., & Feng, A. (2021). Mutlilingual China: National, minority and foreign languages. Routledge.

- Beaven, A., & Borghetti, C. (2016). Editorial: Interculturality in study abroad. Language and Intercultural Communication, 16(3), 313–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2016.1173893

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor Books.

- Borghetti, C. (2017). Is there really a need for assessing intercultural competence? Some ethical issues. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 44. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319304155_Is_there_really_a_need_for_assessing_intercultural_competence_Some_ethical_issues

- Borghetti, C., Beaven, A., & Pugliese, R. (2015). Interactions among future study abroad students: Exploring potential intercultural learning sequences. Intercultural Education, 26(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2015.993515

- Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters.

- Byram, M. (2020). The responsibilities of language teachers when teaching intercultural competence and citizenship - an essay. China Media Research, 16(2), 77–84.

- Byram, M. (2021). Teaching and assessing intercultural competence: Revisited. Multilingual Matters.

- Byram, M., Nichols, A., & Stevens, D. (2001). Developing intercultural communicative competence in practice. Multilingual Matters.

- Deardorff, D. K. (2016). How to assess intercultural competence. In Z. Hua (Ed.), Research methods in intercultural communication (pp. 120–134). Wiley Blackwell.

- Fantini, A. E. (2020). Reconceptualizing intercultural communicative competence: A multinational perspective. Research in Comparative & International Education, 15(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499920901948

- Ferri, G. (2014). Ethical communication and intercultural responsibility: A philosophical perspective. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2013.866121

- Ganassin, S. (2020). Language, culture and identity in two Chinese community schools. More than a way of being Chinese? Multilingual Matters.

- Ganassin, S., Holmes, P., & Song, L. (2019, July 7–10). ‘European’ and ‘Chinese’ co-construction of an intercultural pedagogy for internationalisation of universities in ‘new’ China [Conference presentation]. International Association of Intercultural Relations (IAIR) and China Association for Intercultural Communication (CAFIC), Shanghai International Studies University, Shanghai, China.

- Ganassin, S., Satar, M., & Regan, A. (2021). Virtual exchange for internationalisation at home in China: Staff perspectives. Journal of Virtual Exchange, 4 SI:IVEC 2020, 95–116. https://doi.org/10.21827/jve.4.37934

- Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Doubleday.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International difference in work-related values. Sage.

- Holliday, A. (2016). Difference and awareness in cultural travel: Negotiating blocks and threads. Language and Intercultural Communication, 16(3), 318–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2016.1168046

- Holliday, A. R. (1999). Small cultures. Applied Linguistics, 20(2), 237–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/20.2.237

- Holliday, A. R. (2000). Culture as constraint or resource: Essentialist versus non-essentialist views. Iatefl Language and Cultural Studies SIG Newsletter, 18, 38–40.

- Holliday, A. R. (2013). Understanding intercultural communication: Negotiating a grammar of culture. Routledge.

- Holmes, P., & O'Neill, G. (2012). Developing and evaluating intercultural competence: Ethnographies of intercultural encounters. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(5), 707–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.04.010

- Jia, Y. X., Byram, M., Jia, X. R., Song, L., & Jia, X. L. (2019). Experiencing global intercultural communication: Preparing for a community of shared future for mankind and global citizenship. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

- Jia, Y. X., & Jia, X. L. (2016). The anthropocosmic perspective on intercultural communication: Learning to be global citizens is learning to be human. Intercultural Communication Studies, XXV(1), 32–52. https://www-s3-live.kent.edu/s3fs-root/s3fs-public/file/JIA-Yuxin-JIA-Xuelai.pdf

- Jin, L., & Cortazzi, M. (2011). Re-evaluating traditional approaches in Second Language Teaching and Learning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol. 2) (pp. 558–575). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-99872-7.

- Jin, Y., Wu, Z., Alderson, C., & Song, W. (2017). Developing the China standards of English: Challenges at the macropolitical and micropolitical levels. Language Testing in Asia, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-017-0032-5

- Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall.

- Levi-Strauss, C. (1962). La pensee sauvage. Paris. English translation. The savage mind (Chicago, 1966).

- MOE. (2014). National curriculum guide for college English (testing version). The National College English Teaching Advisory Board.

- MOE. (2018). National standards for assessing the teaching quality of undergraduate programs in English. The National Foreign Language Teaching Advisory Board.

- MOE. (2020a). National curriculum guide for college English. The National College English Teaching Advisory Board.

- MOE. (2020b). National curriculum guide for undergraduate English majors. The National Foreign Language Teaching Advisory Board.

- O'Regan, J. P. (2014). English as a lingua franca: An immanent critique. Applied Linguistics, 35(5), 533–552. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amt045

- PISA. (2021). PISA 2018 Global Competence. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/innovation/global-competence/

- Qin, S., & Holmes, P. (2022). Exploring a pedagogy for understanding and developing Chinese EFL students’ intercultural communicative competence. In T. McConachy, I. Golubeva, & M. Wagner (Eds.), Intercultural learning in language education and beyond: Evolving concepts, perspectives, and practices (pp. 227–249). Multilingual Matters.

- Research Framework of Competences for Democratic Cultures. (2021). https://www.coe.int/en/web/campaign-free-to-speak-safe-to-learn/reference-framework-of-competences-for-democratic-culture

- RICH-Ed. (2021a). Resources for interculturality in Chinese higher education: Inventory of intercultural learning in Chinese higher education. http://www.rich-ed.com/index.php?s=/Show/index/cid/40/id/69.html

- RICH-Ed. (2021b). Resources for interculturality in Chinese higher education: Pedagogic framework. http://www.rich-ed.com/index.php?s=/Show/index/cid/40/id/81.html

- RICH-Ed. (2021c). Resources for interculturality in Chinese higher education. Teacher instructions, Module 6: Linguistic landscaping – Languaging and translanguaging as social and cultural practice. http://www.rich-ed.com/index.php?s=/Show/index/cid/38/id/102.html

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Song, L. (2008). Exploration of a Conceptual Framework for Intercultural Communicative English Language Teaching in China [Unpublished doctoral dissertation], Shanghai International Studies University. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFD0911&filename=2009026155.nh

- Song, L. (2009). Teaching English as intercultural education: Challenges of intercultural communication. Intercultural Communication Research, 1, 261–277. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?bcode=CCJD&dbname=CCJDTEMP&filename=KWJY200900019&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=DTfUKbH3OvESu4SOGEdAVtKz9aUj96w2AOtyXrFWbA1rvLQ-JbeVm7aIZ8Uy8ilS

- Spitzberg, B. H., & Changnon, G. (2009). Conceptualising intercultural competence. In D. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultrual competence (pp. 2–52). SAGE.

- Sun, Y. Z. (2015). Editor in chief. Think•English (textbook series for intercultural English learning). Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

- Sun, Y. Z. (2016). 外语教学与跨文化能力培养 [Foreign language education and intercultural competence development]. 《中国外语》[Foreign Languages in China], 13(3), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.13564/j.cnki.issn.1672-9382.2016.03.001

- Sun, Y. Z., Liao, H. J., Zheng, X., & Qin, S. Q. (2021). 《跨文化外语教学研究》 [Research on intercultural foreign language teaching and learning]. 北京: 外语教学与研究出版社. [Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press].

- Suo, G. F., Weng, L. P., & Kulich, S. (2015). 我国30年跨文化交际/传播教材的分析性评估 (1985-2014) [An analytical evaluation of intercultural communication textbooks published in China (1985–2014)]. 《外语界》[Foreign Language World], 2(3), 89–96. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2015&filename=WYJY201503013&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=l-LzfG_3xCTHWpNiYqRt0k0-Uab7i-Czqqc9ghYfds2VbtKlwD2h-gLeYCfZe0yR

- Tu, W. M. (2013). Spiritual Humanism. Hangzhou International Congress, “Culture: Key to Sustainable Development”, http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/images/Tu_Weiming_Paper_2.pdf

- Van Maele, J., Čebron, N., Ganassin, S., & Holmes, P. (2015, November 30). How can the IEREST Study Abroad Pathway support internationalisation in Chinese Universities? [Conference presentation]. International Association for Languages and Intercultural Communication (IALIC), Peking University, Beijing, China.

- Wang, D. H. (2018). 改革开放40年来我国外语教育的政策回眸 [A review of the policies on foreign language education in China over the past 40 years of reform and opening-up]. 《课程教材教法》[Curriculum,Teaching Materials and Method], 38(12), 4–11.

- Wang, D. H., & Yang, D. (eds.). (2021). 《人类命运的回响——中国共产党外语教育100年》 [Voices of mankind with a shared future: 100 years of foreign language education under the leadership of CPC]. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

- Wang, S. R. (2016). 《大学英语教学指南》要点解读 [An interpretation of guidelines on college English teaching]. . 《外语界》[Foreign Language World], 3, 2–10. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2016&filename=WYJY201603001&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=H0eeDLxwrAoJBqAr61Am2_l_-cgSMw_FIuodEj63x0wdOmqT65-FD3Ic18q1EBT5

- Wang, Y. A., Deardorff, D. K., & Kulich, S. J. (2017). Chinese perspectives on intercultural competence in international higher education. In D. Deardorff, & L. Arasaratnam (Eds.), Intercultural competence in international higher education (pp. 95–108). Routledge.

- Yan, J. L. (2014). 外语教师跨文化交际能力的“缺口”与“补漏” [A study of ‘Gap’and ‘Patching’of intercultural communication competence of foreign language teachers]. 《上海师范大学学报(哲学社会科学版)》[Journal of Shanghai Normal University (Philosophy & Social Science Edition)], 43(1), 138–145. https://doi.org/10.13852/j.cnki.jshnu.2014.01.009

- Zhang, H. L. (2012). 以跨文化教育为导向的外语教学:历史、现状与未来 [Intercultural education-oriented foreign language teaching: History, status and future]. 《外语界》[Foreign Language World], 2, 2–7. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2012&filename=WYJY201202001&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=8QNrTVhkBNjiVuCQpkcjtg9BLoBf_myGu4o9Btx7jnVG07OERZpG1Rb8rUIFKjf1

- Zheng, X., & Li, M. Y. (2016). 探索反思性跨文化教学模式的行动研究 [Exploring reflective intercultural teaching: An action research in a College English class]. 《中国外语》[Foreign Languages in China], 13(3), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.13564/j.cnki.issn.1672-9382.2016.03.002