ABSTRACT

This article discusses the language needs analysis which informed the development of a beginner Arabic language course for Scottish primary education staff who work with Arabic-speaking refugee children and families. Interviews and focus group were carried out with: Scottish educators; Arabic-speaking refugee children; and parents/carers. They highlighted the following language needs for the course: (a) language for hospitality; (b) language for wellbeing; and (c) language for school. In this article we highlight the language needs as identified by refugee pupils and their families and we start a discussion on the importance of teaching a refugee language within formal educational settings.

نقدم في هذه المقالة تحليلاً للاحتياجات اللغوية، والذي تم اجراؤه بهدف تطوير منهاج لتعليم اللغة العربية لغير الناطقين بها للمبتدئين؛ ليتناسب مع موظفي التعليم الإسكتلنديين للمرحلة الابتدائية والذين يعملون مع الأطفال اللاجئين الناطقين بالعربية وعائلاتهم. تم عقد مقابلات فردية وجماعية مع موظفي التعليم الإسكتلنديين والأطفال اللاجئين الناطقين بالعربية ومع أولياء أمورِهم. ولقد سلطوا الضوء على الاحتياجات اللغوية التالية للدورة: (أ) لغة للضيافة؛ (ب) لغة للرعاية؛ (ج) لغة للمدرسة. نركز في هذا المقال على الاحتياجات اللغوية كما حددها موظفو التعليم الإسكتلندي والطلاب اللاجئون وأسرهم ونقوم بطرح النقاش حول أهمية تدريس لغة اللاجئين في البيئات التعليمية الرسمية.

Introduction

The New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy (Scottish Government, Citation2018. Henceforth New Scots) sets out principles for a ‘welcoming Scotland’. It emphasises the need to understand integration as a two-way process (Ager & Strang, Citation2008), where both newcomers and the host communities are actively engaged in ‘stretching towards hospitality’ (Imperiale et al., Citation2021). Scottish language policies value linguistic diversity (Scottish Government, Citation2012, Citation2015), and scholars have recommended a diversification of language teaching within the Scottish education system on the grounds of a range of considerations, including the welcoming of refugees and migrants (Phipps & Fassetta, Citation2015). However, it seems that there is still a gap between what the policies recommend and their full implementation, since community languages are taught only within complementary schools and/or as after-school activities, while in mainstream education a limited number of European languages, such as French, German and Spanish – sometimes with the addition of Mandarin and Urdu – are still dominating (Hancock & Hancock, Citation2019; Christie et al., Citation2016).

A wealth of research on translanguaging, affect, and decolonisation emphasises the importance of multilingualism in educational settings (e.g. Cummins, Citation2015; García & Kleyn, Citation2016; Tsimpli, Citation2017; Phipps, Citation2019). Although policies and research argue for the promotion of linguistic diversity and for the importance of maintaining and encouraging all learners’ linguistic repertoires, to the best of our knowledge little is known about education staff as language learners of one of their students’ languages, and the potential impact that this may have on the wider community. To date, research with refugees and migrants has predominantly focused on how they learn the language of the host community (e.g. Sowton, Citation2019; Capstick, Citation2016).

This article illustrates and discusses the first stage of the project Welcoming Languages: Including a Refugee Language in Scottish Education (henceforth, Welcoming Languages). The project explores the inclusion of a refugee language, namely Arabic, in Scottish education, as a concrete way to enact the promise of integration as a two-way process (Scottish Government, Citation2018). The project involves Scottish primary educators in learning Arabic through a course tailored to their needs. Arabic is the home language of a large number of pupils in Scottish education (Scottish Government, Citation2021), many of whom from refugee backgrounds. Trauma informed literature on education stresses the importance of creating positive and supportive school climate, alongside the need for informed interventions (Thomas et al., Citation2019), and we believe that making space for the language refugees bring can help to ensure a positive school climate for both children and families who may be dealing with very challenging circumstances.

In this article, we present the findings of the first stage of the project, which consisted of a language needs analysis, conducted through semi-structured focus groups with Scottish educators, Arabic-speaking children, and their parents/carers, to inform the design and development of the course. Language needs analysis is considered crucial to develop and plan foreign and second language teaching in a way that this is meaningful to the learners. This is particularly important when designing courses for languages for specific purposes, as in these courses, content and method of teaching should be guided by the learners’ needs (e.g. Richards, Citation2001; Kaya, Citation2021; Kaewpet, Citation2009).

This article is structured as follows: in the first section we provide an overview of the Scottish context and of the project; in the second section we present a literature review on language needs analysis; we then introduce the methodology adopted in this study; and finally, we present and discuss the findings of our language needs analysis.

The Welcoming Languages project: context, aims and design

The context of Scotland

Scotland describes itself as a ‘a diverse, complex, multicultural and multilingual nation’ (Scottish Government, Citation2015, p. 10). While immigration is a ‘reserved matter’ of competence of the UK Westminster government, the integration of refugees and service provision are ‘devolved matters’, for which the Scottish Government is responsible. Under the UK dispersal scheme, asylum seekers in the UK are assigned to locations around the UK on a no choice basis (Stewart, Citation2012). Since the start of this scheme, Glasgow has been one of the main dispersal areas, currently hosting about 11% of the total UK’s dispersed asylum population (Scottish Government, Citation2018). For instance, the city hosts the majority of the 3000 Syrian refugees arrived between 2015 and early 2020 under the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (Migration Scotland, Citation2019). As well as from Syrian refugee families, Arabic-speaking children in Scotland come from a range of other countries in the Middle East and North Africa and, in 2021 there were over 1,500 Arab pupils with asylum seeking or refugee backgrounds and 5,499 Arabic-speaking children in Scottish education (Scottish Government, Citation2022). Two main policies inform refugee integration in Scotland: the New Scots, which is currently being renewed; and the Scotland’s ESOL Strategy 2015–2020 which, although not renewed since publication, has been a key reference point for language learning and the integration of newcomers.

The New Scots, now nearing the end of its second iteration, promotes a welcoming vision of Scotland. The Strategy states right from the very start that ‘[…] refugee integration [is] a two-way process, bringing positive change in refugees and host communities, and helping to build a more compassionate and diverse society’ (Scottish Government, Citation2018, p. 3). The idea of integration as a two-way process is underpinned by the integration framework developed by Ager and Strang (Citation2008) who noted how, from interviews with both newcomers and members of the host community, social connection and relationships are key to integration. Social connection goes beyond ‘absence of conflict’ and ‘toleration’ but is rather concerned with ‘active mixing’ and developing a sense of ‘belonging’ (Ager & Strang, Citation2008, p. 177). Languages, which enable relationships and social connections, are hence crucial to make ‘integration as a two-way process’ viable. While in the first run of the Strategy (2013–2017), language education was recognised as a priority, it was only in the second iteration of the New Scots (2018–2022) that language has become a standalone theme (Slade & Dickson, Citation2021; Cox, Citation2021).

The New Scots works in conjunction with the Scotland’s ESOL Strategy 2015–2020 whose vision is one where:

all Scottish residents for whom English is not a first language have the opportunity to access high quality English language provision so that they can acquire the language skills to enable them to participate in Scottish life. (Scottish Government & Education Scotland, Citation2015, p. 6)

Another Scottish language policy that promotes linguistic diversity, is the 1 + 2 Language Strategy (Scottish Government, Citation2012). Inspired by the language models recommended by the European Union, this policy advocates the introduction of a 1 + 2 approach to modern languages from primary school, and pupils are expected to learn two additional languages alongside their mother tongue (Scottish Government, Citation2012). The 1 + 2 Language Strategy is committed to enhancing the links with ‘language communities’ to ‘derive maximum benefit from foreign language communities in Scotland’ (ibid., p. 24). The implementation of the strategy is, however, still rather patchy, and it espouses a view of multilingualism that is labour-market oriented (Kanaki, Citation2020). Moreover, the extent to which this policy has benefited community languages remains questionable, as it still largely centres on English, while ostensibly celebrating the diversity of community languages spoken in Scotland (ibid.).

Overall, these Scottish policies promote linguistic diversity and value multilingualism, including migrants and refugees’ linguistic repertoires. These policies do indeed favour a welcoming environment in Scotland. However, when it comes to language learning, refugees are still largely expected to learn the host country’s language, and the use of their home language mostly happens within the private sphere or is supported as an extra-curricular activity (Hancock & Hancock, Citation2019; Christie et al., Citation2016; Ramalingam & Griffith, Citation2015). Thus, there is very little space in the public sphere for refugees’ home languages and, as such, refugees’ ‘linguistic capital’ (Bourdieu, Citation1991) remains undervalued and largely disregarded.

The Welcoming Languages project

The Welcoming Languages project (PI: Giovanna Fassetta; University of Glasgow, Award n. AH/W006030/1) explores the inclusion of Arabic as a refugee language in Scottish education. The project offers a free online Arabic course to Scottish primary educators (teachers, head-teachers, secretarial staff, classroom assistants) based in Glasgow. The course is a tailored version of an online Arabic language course that was designed during a previous project (see Fassetta et al., Citation2020) in collaboration with the Islamic University of Gaza (Palestine).

The Welcoming Languages project is articulated around four main phases: (i) a language needs analysis, to understand what language Scottish educators should learn as a matter of priority; (ii) the adaptation of the existing course to be tailored to the learners’ context and needs; (iii) the delivery of the course to Scottish educators; (iv) the overall evaluation of the project. In the next section, we explore relevant literature on language needs analysis.

Language needs analysis: a brief review of the literature

Understanding the needs of second or foreign language learners is key to plan and deliver language education, from the development of a syllabus to the planning of individual L2 lessons (Brown, Citation1995). In the case of language education for specific purposes, needs analysis becomes even more important to develop tailored and meaningful language courses (Dodigovic & Agustín-Llach, Citation2020; Huhta et al., Citation2013). Although there is no straightforward definition of ‘needs analysis’, there is agreement around the idea that this is a tool used by curriculum developers to identify what learners know, and what they need to know to perform in the specific target environments (Basturkmen, Citation2005). Language needs analysis often corresponds to a ‘placement test’ (Dodigovic & Agustín-Llach, Citation2020) carried out by language centres, which aims to understand learners’ competences and skills in order to place learners across levels. Some scholars argue that there is still a lack of understanding of the complexities of needs analysis (Long, Citation2005; Hutha et al., 2013).

We found a very limited number of studies on language needs analysis for Arabic for Specific Purposes. Golfetto (Citation2020) conducted a survey with 205 students enrolled in undergraduate and postgraduate courses in Linguistics and Cultural Mediation in Italy. The author investigated students’ motivation and their job orientation and concluded by outlining which courses are perceived as most useful to satisfy students’ professional motivations. Abdul Ghani et al. (Citation2019) wrote a literature review on Arabic for Specific Purposes courses in Malaysia, finding studies which also undertook language needs analysis: for example, Saleh (Citation2005) analysed the needs of Hajj pilgrims, and found that their main interest is religion and oral communication; Hashim (Citation2009) explored the needs of economics students, and found that reading skills were considered crucial to succeed. Ahmad (Citation2017) explored the needs of Syariah officers working in Malaysian Islamic banks, identifying Islamic banking and financial terms that those officers needed in their career. A number of studies focused on Arabic for tourism (e.g. Jaafar, Citation2013; Adam, Citation2013; Adam & Chick, Citation2011). What is interesting to note is that the majority of these language needs analysis studies focus on understanding what language skills should dominate in the teaching of Arabic, with some studies also exploring useful vocabulary and pedagogy (Abdul Ghani et al., Citation2019). None of the studies we found in the context of Arabic for Specific Purposes, however, adopted a task-based approach to needs analysis. We will return to the importance of task in the following paragraphs.

There are numerous methods and approaches to conduct needs analysis (Long, Citation2005). Significant research started around the 1970s, and it was further developed by the work of the Council of Europe in the 1990s (Huhta et al., Citation2013). We found a model developed in the early 1990s by Robinson (Citation1991) particularly helpful for our study. Robinson (Citation1991), working within English for Special Purposes, understood needs as pertaining to three levels: the micro-, the meso-, and the macro-levels. Micro-level needs concern, and are usually identified by, the individual learner. However, the author argued, we also need to consider the interests of the wider context in which learners operate (i.e. Robinson’s study, the workplace) and these represent the needs at the meso-level. Finally, Robinson pointed out that we should not forget the society’s needs, this being the macro-level.

Drawing from Robinson’s model (Citation1991), Hutha et al. (2013) developed this work further, incorporating insights from the Common European Framework of Reference for Language (Council of Europe, Citation2001). Hutha et al. (2013) moved from ‘language-centred approaches’, which ‘focus exclusively on functions and notions and on the four skills of speaking, listening, writing and reading’ (p.14), and rather considered the ‘task’ (Council of Europe, Citation2001) as ‘the primary unit of needs analysis’ (Hutha et al., 2013, p.15). The meso- and the macro-levels then acquire particular importance as the learner is always perceived in interaction with others (Hutha et al., 2013). In our project, we grounded our needs analysis in this model, considering the task as the primary unit of analysis.

Hutha et al. (2013) suggest that a task-based needs analysis should be done mainly qualitatively, to allow researchers to dig deeper into the needs, as surveys and questionnaires might not provide the same depth of information. Similarly, texts analysis (including genre, content and discourse analysis) or language tests might not provide sufficient information around the learner profile (Hutha et al., 2013). Long (Citation2005) argued that often learners are ‘non-experts’ of the target language and, although they have an idea of what they might need, their expectations may not be entirely viable. As such, needs analysis should involve different stakeholders, especially those who might operate in the target environment.

In the Welcoming Languages project, the Arabic language learners are Scottish educators already working with Arabic-speaking families and children, who have a quite clear understanding of their needs. We therefore considered them, as ‘experienced learners’ (Long, Citation2005). We also included Arabic-speaking children and their parents/carers in the needs analysis, as they will be involved in the target context. In the next section, we present the methodology adopted for the task-based needs analysis.

Methodology

The chosen methodology involved qualitative data collection with different stakeholders, which we then triangulated. We conducted a total of 4 focus groups with Scottish educators, 3 focus groups with Arabic-speaking children, which also included the use of visual methods, and 3 focus groups with Arabic-speaking parents and carers. Focus groups were chosen as a method for data collection as they help to facilitate communication among participants and, at the same time, allow the collection of high-quality information in a restricted period of time (Acocella, Citation2012), an important consideration as the Welcoming Languages project is of relatively short duration (12 months).

Participants and participant recruitment

We conducted the needs analysis in four schools in the Glasgow City Council area, located in parts of the city with higher refugee resettlement numbers. We first approached the head-teachers of a number of primary schools in these areas, to explain the project in detail, and we then asked head-teachers to gauge interest among their staff. We then organised focus groups with the staff members who expressed an interest in learning Arabic. Following this, we asked the educators to facilitate the organisation of focus groups with Arabic-speaking parents and children in their schools. As one of the schools joined the project later than the others, we did not carry out the needs analysis with families and children in this school, as this would have held up the adaptation of the course.

Details of the focus groups and of participants are presented in . The focus groups with education staff included: a total of 11 primary teachers; 1 head-teacher; 3 English as an Additional Language (EAL) teachers; 4 family support staff; 1 head of subject, 1 administrator. The staff were almost entirely speakers of English as a fist language, although one was an Urdu speaker, and one already had some basic Arabic. Most of the staff had a school level knowledge of a modern language but only one had studied languages at university level. All schools celebrate linguistic diversity in some form, and one of the schools held ‘language of the month’ activities prior to closure during the Covid pandemic (which they hope to resume). However, by and large the celebration of linguistic diversity usually takes the form of multilingual posters and signage around the school.

Table 1. Overview of participants.

Methods

All data was collected through semi-structured focus groups. In the focus groups with educators, the participants were asked about the situations in which they saw themselves speaking Arabic, what tasks they expected they would need Arabic for, and what their priorities were. During the focus groups with parents and children, we asked participants to tell us what they thought the school staff should learn to say in Arabic.

The focus groups with parents/carers were conducted multilingually, mainly in Arabic but with some English used as and when the parents/carers felt this necessary. The focus groups with Arabic-speaking children run at the same time as the focus groups with the parents/carers. We gathered the families together and, after an introduction the project (including distributing the participant information sheet and asking parents and children to sign the consent/assent forms) we split the large group into parents/carers, who talked with the project’s research associate (a native Arabic speaker); and children, who worked in small groups to create collective posters with Author 1 (who speaks Arabic at an intermediate level) and Author 2, who used her ‘linguistic incompetence’ (Phipps, Citation2013) to invite the children to teach her Arabic through drawings and writing. Engaging children also through visual methods, rather than just verbally, helped to shift the focus of the conversation from the children to the physical object, creating a more relaxed environment by reducing direct pressure to respond (Punch, Citation2002). It allowed children to choose pictures and/or writing according to their literacy skills, their age, and their preference; and it complemented and supported the oral conversations that developed naturally around the material object of the poster (Literat, Citation2013). The option of using Arabic and/or English (both orally and in writing) added a translanguaging dimension to the children’s responses as they were able to freely use the language that better expressed what they wished to convey (Bradley et al., Citation2018).

As the focus groups with parents/carers and children were held in the same room, it frequently happened that the adults joined their children as they were writing on their posters and, vice-versa, that children joined the discussion with their carers/parents. The fluid, multimodal and multilingual nature of these interactions allowed the data collection to remain open to a range of ways of being and doing, an essential part of intercultural research (Phipps, Citation2013). Echoing recent conversations hosted by this journal on the use of arts-based methodologies with participants (e.g. Bradley et al., Citation2018) multilingual fluidity and flexibility coupled with multimodality meant a more ‘natural’ interaction with children and adults alike. This meant that all language users (educators, Arabic-speaking children and parents/carers) were involved in shaping the content of the Arabic course, in line with what Freire (Citation1970) terms ‘generative themes’. These are themes that emerge dialogically, ‘[…] filled with emotional content that constitutes experiences and shared values’ (Sousa et al., Citation2019) and that are oriented to action and transformation.

Data analysis

Having multimodal and multilingual data, we operated as a bricoleur (Kincheloe, Citation2001), combining multiple tools to make meaning of the data. We transcribed our multilingual data in the language in which they were collected, and we conducted the analysis in English. For our multimodal data, i.e. the children’s posters, we used multilingual thematic analysis, but we also used mind-mapping throughout the data analysis stage, and this helped us make meaning of the data we gathered (Ellingson, Citation2009). All the data collected from the focus groups with parents/carers, children and educators was cross analysed, to identify common themes across all stakeholders.

Findings and discussion

In this section we first present the findings of our needs analysis, reporting them under sub-headings for each group of participants. We then compare and converge the findings in the discussion part, highlighting three main themes that emerged from the needs analysis. These are also the broad themes around which the Arabic course is being designed, and we termed them: (a) language for hospitality; (b) language for wellbeing; (c) language for school.

Findings: focus groups with Scottish educators

There was consensus among the group of educators regarding the necessity to learn ‘basic expressions’ in Arabic to make newcomers, both parents and children, feel welcome. These expressions included: basic greetings, simple conversations that are usually held at the school gates, and some key expressions needed to arrange meetings, and to call an interpreter.

By way of example, a school staff member said:

For me I think it would be that welcoming

yeah

you know, to be able to communicate at basic level […] so that they feel that they are welcomed into the school and the community and (inaudible word). I mean maybe we value you.

I think I think school routine is very high on the list because trying to communicate to the children what's actually happening, what the other children are doing is quite difficult and we have to […] kind of assume […]

particularly a class teacher […]

yes, I am a class teacher, but it's just really hard to kinda say like ‘you come to the carpet?’ or ‘you stay there’. Or ‘cause we say to everybody, “if you need help, come to me”’ […]

things like that it's very important to have like that kind of instructions like classroom routines and things like that.

It concerns me the most when they're crying in class, and you say ‘what's wrong? Why are you sad?’ […] or ‘[Are] you hurt?’ ‘Are you unwell?’ Ehmm, you know, that's the communication that that eh, it is most important, I think.

There are a lot of children who are quite capable in math, but they’re just … can’t read it, so if we actually say like ‘You’re adding that together – we're taking that away […]’ I mean probably not for a beginner of course but …

that language I think would be quite.. very good

yeah yeah

I suppose words like add, take away, multiply […]

As noted earlier, the group of Scottish educators we interviewed did not only include classroom teachers, but also staff members with different roles, e.g. family support staff, EAL teachers, management. All participants highlighted specific language tasks that directly relate to their role: for example, classroom teachers stated that they needed basic instructions to run lessons smoothly while those involved in management expressed an interest in learning about basic instructions to enable enrollment, to explain what documents are needed and to be able to help parents fill in the required forms. Helping parents by signposting them to specific support available (e.g. food banks; financial support) was a task that family support staff wanted to be able to do.

Other topics were mentioned as important, such as (a) learning the Arabic alphabet in order to be able to begin to read some simple words that may be part of the school linguistic landscapes, and (b) being able to count in Arabic. A teacher told us:

I think it [counting] is the easiest to learn. Obviously, there's not much to learn. There are not many ways you can get it wrong

[giggling] yeah yeah, I see

so like so high it is counting with the little ones, you know, in their in their language, is eh it is quite powerful

Findings: focus groups with Arabic-speaking children

Children were asked in both Arabic and English what they would like staff in their school to know. The prompt was: ‘What Arabic words would you like to teach to Miss … or Mr … ?’ As they started talking, we invited them to write things down and also to use drawings if they wished to. In all focus groups, the immediate response from children was a very enthusiastic: ‘Everything!’ so we guided them to break down ‘Everything’ by thinking about the first words staff in their school should know.

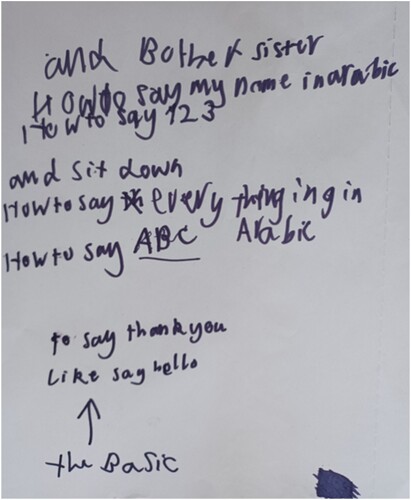

These first words were often greetings. Hello! Salam Alaykum! Thank you! Shokran. Children showed pride in saying those words in Arabic, even though when it came to writing, only some of them decided to write them in Arabic, preferring English instead. In the detail from a poster (), a child started by writing ‘the Basics’ and then, through our subsequent questions, added more details.

There was consensus among children that teachers should learn how to write in Arabic. Many of them pointed out that teachers do not know the pupils’ name in Arabic (or cannot pronounce their names correctly) and should learn how to write their own names and the children’s names in Arabic:

My name is G., but teachers don’t know how to write it in Arabic.

Would you like them to write your name in Arabic?

Yes! [enthusiastically]

let me try to write it down. is it how you spell it in Arabic [scribbling on the notebook]?

No, you should use this [letter] [scribbling it on the notebook, pronounced as J, as in John].

Ah, so it is J and not G. So your name is J. and not G.? Is that right?

Yes, it is. but I don’t mind. Here everyone calls me G., I like G.!

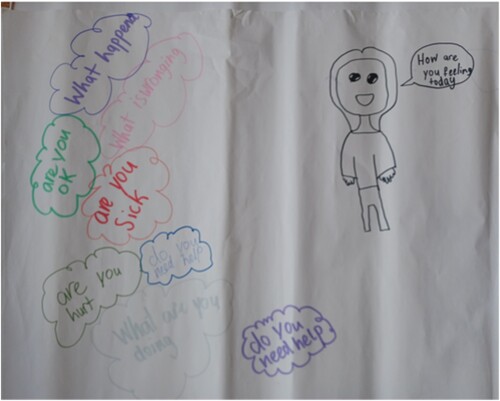

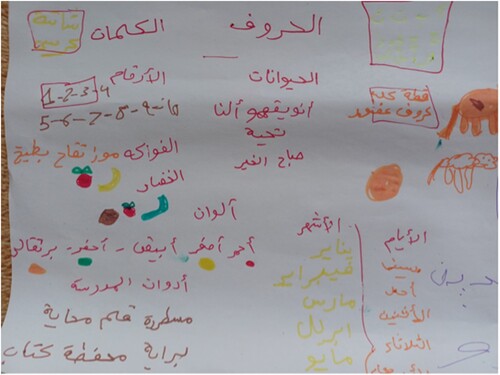

Other, mainly older, children mentioned they wanted teachers to learn language related to helping pupils, such as ‘What happened?’, ‘Are you sick?’, as shown in . This mirrored what educators and parents had also said. Younger children usually pointed out that numbers, colours, objects in the classrooms, objects in the gym and in the backyard should be learned. Some of them, as shown in , wrote a list of colours, fruits, animals. One EAL teacher, who was in the room when the focus group took place, explained that those were precisely the topics that the children were learning during their EAL support classes.

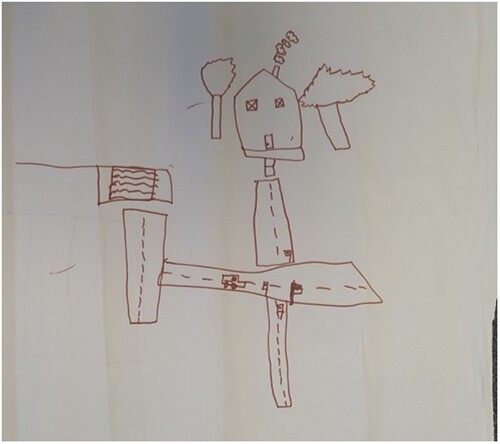

In another small group three children were drawing together, and they then explained what the drawing () represented:

What’s that? Is it a house or a school?

Yes, it is the school, in Arabic madrasa.

Madrasa. And here, what’s that? What should teachers know? [pointing at the streets and traffic light on the poster]

They know if it is red they have to stop, and green they can go.

Oh yes, that’s important to know. Should they be able to say that in Arabic?

Yes, green and red.

and all the colours.

Oh, I see, that’s a good idea! Write them down

Yes, let’s write the colours here

No, let’s draw a tree here

Findings: focus groups with parents/carers

Similar to the priorities highlighted by Scottish educators, parents agreed that it was crucial for staff to learn the ‘basics’ or ‘daily expressions’, that is, simple sentences for greetings and welcoming, and the alphabet. There was consensus regarding not teaching grammar at this level. These points are exemplified by the following extract:

الأهالي : نبدأ بالحروف، الأحرف الأبجدية اكيد

والد1: أحرف الأبجدية، هادا اييه قواعد العربي شوي صعبة مش للمبتدئ مش سهلة يتعلمها

والدة1: القواعد مش أساسية في هادا ال level ال اييه twenty first hours is not necessary

والد: الأحرف الأبجدية والجمل البسيطة مثل السلام عليكم وما اسمك؟ الحاجات البسيطة بسيطة

والدة2: ال Footnote1keywords

we start with letters. The alphabet, for sure

alphabets, this eeeh the Arabic grammar is a bit difficult; it’s not for a beginner; it’s not easy to learn.

Grammar is not necessary at this level. Eeeh [teaching Grammar during] the first twenty hours [of a course] is not necessary

alphabets and simple sentences like Assalaamu aleikom [hello – Islamic greeting], what’s your name? These simple things.

The – keywords.

والد: معرفة الطفل شعور الطفل لما يكون سعيد تعبان مريض شغلات زي هيك

والدة: مثلا انت زعلان؟ حدا مضايقك؟ تخانقت مع صديقك؟ او شي متل هيك

to know how the child feels, to know if he is happy, tired, sick, such things

for example, are you sad? Is there anyone bothering you? Did you argue/fight with your friend? Or anything like that.

لما بدي اسال على الطفل على سبيل المثال انا بدي كل اجي اليوم انا بعد الدوام اسال على ابني كيف كان وضعه ضمن النهار، كيف كان سلوكه بالمدرسة كل يوم، ف هدول ضروري الأشياء انن يتعلموها، لانه انا مثلا ما بعرف احكي لغة فلما بدي اجي اسال عن سلوك ابني يوميا ما بعرف كيف ف بحمل حالي وبمشي ما بقلن

when I want to ask about the child. For example, whenever I want to come after work to ask about my kid, how was he during the day, how did he behave every day, so these things are necessary for them [staff] to learn because I, for example, do not know how to speak a language [English], so whenever I want to ask about my son’s behaviour daily, I do not know how [to ask in English], so I just walk away [literal translation: carry myself and walk away] without telling them

There were also lengthy discussions about which Arabic variety should be taught, and there was no consensus about that. Arabic is a mulltiglossic language (Badawi, Citation1973), that is, it has different varieties. The word Fusha refers to two varieties: the classical variety and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). The classical variety is the language of Quran and of ancient literature, while MSA is the language of education and the language used by the media in the Arab world. However, daily communication is performed in what is called Ammyiah, which refers to the colloquial varieties used in each country of the Arab world.

Although all parents perceived Fusha as the ‘original’, ‘correct’ and ‘right’ form of the language, and although some of them mentioned that ‘it is better to teach Fusha’, others mentioned that the dialect would be ‘easier’ and would allow staff in the school to interact with children more adequately. It is noticeable, however, that those parents were cautious while mentioning this, as dialects are often perceived as a ‘corruption’ of Fusha, which is the variety that should be taught (Holes, Citation2004).

اه اه هي الفكرة، الفكرة هو الأصول يتعلموا اللغة العربية صح هو بس انتو هو كمشروع لتواصل مع الطلاب لو كانت اللغة العامية بردك حيكون شيء جميل يعني

it would be better if it [the course] was in Fusha, but the dialect may be easier for students […] The idea is that, conventionally, they should learn Arabic correctly [referring to Fusha], but as a project to communicate with students, Ammyiah would be good too.

Discussion

The aim of the language needs analysis was to guide the re-adaptation of an existing, generic beginner Arabic course into a beginner course tailored specifically to educational settings. The focus groups aimed to find out what tasks educators need to be able to perform in Arabic. We identified three main shared themes, which we termed: (a) Language for hospitality; (b) Language for wellbeing; (c) Language for school.

(a) Language for hospitality

The main task all participants identified as crucial is making newcomers, both children and parents/carers, feel welcome when they first arrive. Ricoeur (Citation2004) talks about ‘linguistic hospitality’ in the context of translation, noting that translation is an act of hospitality as it enables communication. However, translation requires interlocutors to have a proficient language level. We posit here that acquiring ‘language for hospitality’ does not require a proficient language level but rather reflects the process of enabling imperfect, incorrect, imprecise communication which acknowledges and starts from the ‘linguistic incompetence’ (Phipps, Citation2013) of all interlocutors. We understand ‘language for hospitality’ as including basic greetings and welcoming sentences, aimed at providing welcoming and forging connections through the knowledge of some simple, kind and ‘hospitable’ words and sentences.

We include in the ‘language for hospitality’ theme, the wish of education staff, but also of parents and children, to learn the Arabic alphabet. As we noted above, this challenged our assumptions that education staff would only be interested in speaking and listening. However, the staff’s wish to learn to read and write in Arabic – or at least to be able to recognise the Arabic alphabet – suggests that they hold an expectation of themselves as speakers of Arabic, one in which they have access to what Kramsch (Citation2006, p. 98) calls ‘fantasies of other identities’. Being an Arabic learner, then, also includes this ‘fantasy of another identity’, one in which they are able to make sense of the ‘squiggles’ – as one of the teachers called them – of the Arabic script.

(b) Language for wellbeing

Within the ‘Language for wellbeing’ theme, we included what all participants mentioned in relation to being able to identify and respond to basic needs, provide help, and explore emotions and feelings, in particular when pupils are distressed. Research on the ways in which distress is communicated in foreign languages abounds, with consensus on the importance of using the distressed person’s native tongue (Costa & Dewaele, Citation2012). However, this implies the possibility to work with interpreters and translators.

The tasks that educators, children and parents mentioned during the focus groups, once again, do not require mastering a foreign language at proficient levels, but rather offering an immediate response to get through the distressful moment. As Noddings (Citation1984) notes, an ‘ethics of care’ should be at the heart of the education system, and care requires receptive attentiveness (Noddings, Citation2012). Being able to provide and demonstrate this attentiveness through the use of the Arabic language, however limited or imperfect, was a communicative task that all participants identified as crucial.

(c) Language for school

During our focus groups, both educators and Arabic-speaking children and their families highlighted that another priority should be to learn some basic language specific to the educational settings. Refugees and migrants are required to learn new language skills upon their arrival to the host country, and substantial research has been done on teaching methodologies, curriculum development, teacher education, and more broadly the teaching of the language of the host community in relation to refugee pupils’ specific needs (e.g. Crul, Citation2017; Sarmini et al., Citation2020). For example, beginner courses for English as an Additional Language, provide basic English knowledge and skills to allow children to function within the school environment. Our participants mentioned very similar topics to the ones that children learn during their EAL classes, in relation to the school environment. Tasks include to be able to explain the school routine to both children and parents/carers, to be able to communicate basic instructions to children when they are in class, and potentially some subject-related content. What was interesting to note, in relation to this theme, was the readiness with which the children were able to imagine staff in their school as language learners, readily transposing their own experiences of learning on them.

Conclusions

In this article we presented a task-based language needs analysis conducted to inform the re-adaptation of a generic beginner Arabic course to suit the specific needs of professionals in education in Scotland. In Scotland, several language policies promote linguistic diversity and the inclusion of newcomers as active members of the society (Scottish Government, Citation2012, Citation2015, Citation2018). The New Scots is underpinned by the principle that integration is a two-way process. This involves reciprocal learning and mutual efforts, in which not only refugees and migrants need to take a step towards the host community, but where also the host community tries to ‘stretch towards’ hospitality (Imperiale et al., Citation2021; Imperiale & Slade, Citation2022).

Hospitality – and integration – often happen in language, and language education has a key role in developing inclusive societies, when learning the language of the ‘Other’ becomes a way to get closer to this same ‘Other’. However, it is always newcomers who are required to learn the language of the host community, while community languages are not mainstreamed in education settings. The Welcoming Languages project tries to challenge this, and to enhance the visibility and presence of refugee languages in Scottish education settings by teaching Arabic to Scottish educators.

We conducted the needs analysis to guide the design and development of the Arabic course by consulting different stakeholders through semi-structured focus groups: we involved primary Scottish educators based in four schools in the Glasgow district, Arabic-speaking children and their parents/carers. The aim was to gather themes that are meaningful to educators and to Arabic-speaking children and parents/carers, based on the tasks that they carry out in their everyday interactions (Freire, Citation1970). We found that there was consensus among educators, Arabic-speaking children and parents/carers around three main themes, which we named: (a) language for hospitality, (b) language for wellbeing, and (c) language for school. While (c) is specific to the educational setting, the former two themes could also be extended beyond the school context to all service providers who work with refugees and newcomers. Language for hospitality and language for wellbeing, in fact, both aim to establish caring interpersonal relationships that do not depend so much on proficiency in the target language but more on the demonstration of an active willingness to make space for the languages of those who have made Scotland their home. While the Welcoming Languages project has an important practical dimension, the symbolic dimension of Scottish education staff learning a refugee language cannot be underestimated, as it embodies a willingness to welcome and care for New Scots that stands in sharp contrast to the ‘hostile environment’ policy pursued by the UK Home Office (Fekete, Citation2020).

This study contributes to the field of language education with refugees and migrants in two ways: firstly, it starts conversations around learning with and from refugees, which is something that is still scantly discussed in the relevant literature (Imperiale & Slade, Citation2022). This concerns the involvement of refugees as primary stakeholders in determining what is needed to create a welcoming environment (Freire, Citation1970), in and with language, to actively engage in ‘linguistic hospitality’. Our recommendation is that, in thinking about language policies in Scottish education, refugee and migrant communities are included in the conversation, to broaden the range of considerations that inform language policies in education, and to ensure that the languages spoken by ‘New Scots’ have parity of voice and parity of esteem (see also Phipps & Fassetta, Citation2015). Secondly, we hope that our language needs analysis contributes to the field of needs analysis by providing an example of task-based approach to needs analysis for Arabic for Specific Purposes, a topic that, to the best of our knowledge, has not yet been explored.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants who took part in this study, and to the anonymous peer-reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maria Grazia Imperiale

Maria Grazia Imperiale (University of Glasgow, School of Education) is a Lecturer in Adult Education at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. Her research interests focus on language education for adult refugees and migrants, multilingualism, and intercultural education. She conducted research in several contexts, including Palestine, Lebanon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Italy and Scotland. She also worked as a language teacher and a teacher trainer. She is a member of the Glasgow Refugee Asylum Migration Network (GRAMNet) and part of the network’s steering committee. E-mail: [email protected]

Giovanna Fassetta

Giovanna Fassetta (University of Glasgow, School of Education) is a Senior Lecturer in Social Inclusion in the School of Education (University of Glasgow) and one of the co-conveners of the Glasgow Refugee Asylum and Migration Network (GRAMNet). Giovanna’s background is in language teaching and primary education, and her teaching and research focus on: linguistic and cultural diversity; culture and arts for peacebuilding; inclusion of children and young people from refugee and migrant backgrounds; and inclusion of marginalised groups in educational settings. E-mail: [email protected]

Sahar Alshobaki

Sahar Alshobaki (University of Glasgow, School of Education) is PhD candidate at Roehampton University, Media, Culture and Language department, and a Research Associate at the University of Glasgow (School of Education). She has taught languages (English and Arabic) online and face-to-face in the UK, Austria, Turkey, and Palestine in the primary and secondary school sector, as well as in higher education. She is interested in language learning and teaching, in particular the use of vision and strategies in teaching and learning a foreign language. Sahar is also interested in researching second language motivation, translanguaging, self, and online teaching and learning. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1 Translation from Arabic into English was done by the third author.

References

- Abdul Ghani, M. T., Wan Daud, W. A. A., & Ramli, S. (2019). Arabic for specific purposes in Malaysia: A literature review. Issues in Language Studies, 8(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.33736/ils.1293.2019

- Acocella, I. (2012). The focus groups in social research: Advantages and disadvantages. Quality & Quantity, 46(4), 1125–1136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9600-4

- Adam, Z. (2013). Taalim al arabiah li aghradh siyahiyah fi Malizia: Tahlil al hajat wa tasmim wihdat dirasiah. Unpublished PhD Thesis, International Islamic University Malaysia.

- Adam, Z., & Chick, A. R. (2011). Al hajat ila daurah al lughah al arabiah li aghrad al siyahah fi Malizia. Prosiding Seminar Antarabangsa Pengajaran Bahasa Arab 2011 (SAPBA'11) (pp. 320–332). Selangor: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

- Ager, A., & Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies, 21(2), 166–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016

- Ahmad, N. A. (2017). Wehdah dirasiyyah muqtarahah li taalim al arabiah li muwazzifi al syaria fi al bunuk al islamiah fi Maliziya. Unpublished Master Dissertation, International Islamic Universiti Malaysia.

- Badawi, M. (1973). Mustawayāt al-ʿarabiyya al-muʿāṣira fī Miṣr. Dār al-Maʿārif.

- Basturkmen, H. (2005). Ideas and options in English for specific purposes. Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Harvard University Press.

- Bradley, J., Moore, E., Simpson, J., & Atkinson, L. (2018). Translanguaging space and creative activity: Theorising collaborative arts-based learning. Language and Intercultural Communication, 18(1), 54–73. DOI: 10.1080/14708477.2017.1401120

- Brown, J. D. (1995). The elements of language curriculum: A systematic approach to program development. Cambridge University Press.

- Capstick, A. (2016). Language for resilience – The role of language in enhancing the resilience of Syrian refugees and host communities. British Council. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/language_for_resilience_report.pdf (last accessed: 8/9/2022)

- Christie, J., Robertson, B., Stodter, J., & O’Hanlon, F. (2016). A Review of Progress in Implementing the 1 + 2 Languages Policy. Association of Directors of Education in Scotland (ADES).

- Costa, B., & Dewaele, J.-M. (2012). Psychotherapy across languages: Beliefs, attitudes and practices of monolingual and multilingual therapists with their multilingual patients. Language and Psychoanalysis, 1(1), 18–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2013.838338

- Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages. Cambridge University Press.

- Cox, S. (2021). ‘You and me, we're the same. You struggle with Tigrinya and I struggle with English.’ An exploration of an ecological, multilingual approach to language learning with New Scots. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis [University of Glasgow].

- Crul, M. (2017). Refugee children in education in Europe. How to prevent a lost generation? SIRIUS Network Policy Brief Series, Issue No. 7.

- Cummins, J. (2015). Inclusion and language learning: Pedagogical principles for integrating students from marginalized groups in the mainstream classroom. In C. M. Bongartz, & A. Rohde (Eds.), Inklusion im Englischunterricht (pp. 95–116). Switzerland.

- Dodigovic, M., & Agustín-Llach, M. P. (2020). Vocabulary in curriculum planning: Needs, strategies and tools. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ellingson, L. (2009). Engaging crystallization in qualitative research. An introduction. SAGE.

- Fassetta, G., Imperiale, M. G., Aldegheri, E., & Al-Masri, N. (2020). The role of stories in the design of an online language course: Ethical considerations on a cross-border collaboration between the UK and the Gaza Strip. Language and Intercultural Communication, 20(2), 181–192. DOI: 10.1080/14708477.2020.1722145

- Fekete, L. (2020). Coercion and compliance: The politics of the ‘hostile environment’. Race and Class, 62(1), 97–109. DOI:10.1177/0306396820930929

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin Modern Classics.

- García, O., & Kleyn, T. (2016). Translanguaging with multilingual students: Learning from classroom moments. Routledge.

- Golfetto, M. A. (2020). Towards Arabic for specific purposes: A survey of students majoring in arabic holding professional expectations. Ibérica, 39, 371–398. http://www.revistaiberica.org/index.php/iberica/article/view/88

- Hancock, A., & Hancock, J. (2019). Scotland’s language communities and the 1 + 2 language strategy. Languages, Society & Policy, 210–220. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.47263

- Hashim, N. (2009). Taalim Al Arabiyyah Li Aghrad Khassah: Durus Li Al Mutakhassisin Fi Majal Al Iqtisad. Unpublished Master Dissertation, International Islamic University Malaysia.

- Holes, C. (2004). Modern Arabic: Structures, functions, and varieties. Georgetown University Press.

- Huhta, M. Vogt, K. Johnson, E., & Tulkki, H. (2013). Needs Analysis for Language Course Design. A holistic approach to ESP. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Imperiale, M. G., Phipps, A., & Fassetta, G. (2021). On online practices of hospitality in higher education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 40(6), 629–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-021-09770-z

- Imperiale, M. G., & Slade, B. (2022). Learning with and from refugees: adult education to strengthen inclusive societies. CR&DALL Briefing Paper 6/ PASCAL Briefing Paper 20. Available at: http://cradall.org/content/learning-and-refugees-adult-education-strengthen-inclusive-societies

- Jaafar, M. N. (2013). Tahlil Hajat Mutakhassisi Al Lughah Al Arabiah Wa Al Ittisalat Bi Jamiah Al Ulum Al Islamiah Al Maliziah Fi Taalum Al Lughah Al Arabiah Li Aghrad Siyahiayh. 4th International Conference of Arabic Language and Literature (ICALL 2013). IIUM Press.

- Kaewpet, C. (2009). A framework for investigating learner needs: Needs analysis extended to curriculum development. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 6(2), 209–220.

- Kanaki, A. (2020). Multilingualism from a monolingual habitus: The view from Scotland. In C. Strani (Ed.), Multilingualism and politics. Revisiting multilingual citizenship (pp. 210–220). Palgrave Mcmillan.

- Kaya, S. (2021). From needs analysis to development of a vocational English language curriculum: A practical guide for practitioners. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 5(1), 154–171. https://doi.org/10.33902/JPR.2021167471

- Kincheloe, J. L. (2001). Describing the bricolage: Conceptualizing a new rigor in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 7(6), 679–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040100700601

- Kramsch, C. (2006). The multilingual subject. Preview article. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 16(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2006.00109.x

- Literat, I. (2013). “A pencil for your thoughts”: Participatory drawing as a visual research method with children and youth. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12(1), 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691301200143

- Long, M. H. (2005). Second language needs analysis. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667299

- Migration Scotland. (2019). Refugee resettlement. http://www.migrationscotland.org.uk/uploads/19-028%20Item%2002%20Refugee%20Resettlement.pdf

- Morrice, L., Tip, L. K., Collyer, M., & Brown, R. (2019). You can’t have a good integration when you don’t have a good communication’: English-language learning among resettled refugees in England. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(1), 681–699. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez023

- Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. University of California Press.

- Noddings, N. (2012). The language of care ethics. Knowledge Quest, 40(5), 52–56.

- Phipps, A. (2013). Intercultural ethics: Questions of methods in language and intercultural communication. Language and Intercultural Communication, 13(1), 10–26. DOI: 10.1080/14708477.2012.748787

- Phipps, A. (2019). Decolonising Multilingualism: Struggles to Decreate: Multilingual Matters.

- Phipps, A., & Fassetta, G. (2015). A critical analysis of language policy in Scotland. European Journal of Language Policy, 7(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.3828/ejlp.2015.2

- Punch, S. (2002). Research with children. The same or different from research with adults? Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark), 9(3), 321–341. DOI: 10.1177/0907568202009003005

- Ramalingam, V., & Griffith, P. (2015). Saturdays for success: How supplementary education Can support pupils from All backgrounds to flourish. Institute for Public Policy Research.

- Richards, J. C. (2001). Curriculum development in language education. Cambridge University Press.

- Ricoeur, P. (2004). Sur la traduction. Bayard.

- Robinson, P. (1991). ESP today: A practitioner's guide. London: Prentice Hall.

- Saleh, A. H. (2005). Tasmim Wihdat Dirasiyyah Lil Hujjan Wa Al Mutamirin Al Maliziyyin Fi Taalim Al Lughah Al Arabiyyah Li Aghrad Khassah. Unpublished Master Dissertation, International Islamic University Malaysia.

- Sarmini, I., Topçu, E., & Scharbrodt, O. (2020). Integrating Syrian refugee children in Turkey: The role of Turkish language skills (a case study in Gaziantep). International Journal of Educational Research, Open, 1, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100007

- Scottish Government & Education Scotland. (2015). Welcoming Our Learners: Scotland’s ESOL Strategy 2015 - 2020. https://www.education.gov.scot/Documents/ESOLStrategy2015to2020.pdf

- Scottish Government. (2012). Language learning in Scotland: A 1 + 2 approach, Scottish government languages working group report and recommendations. Edinburgh.

- Scottish Government. (2018). New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. https://www.gov.scot/publications/new-scots-refugee-integration-strategy-2018-2022/

- Scottish Government. (2021). Integrating New Scots. Available from https://www.gov.scot/news/integrating-new-scots/ (Last accessed on 15th April 2022)

- Scottish Government. (2022). Pupil Census: Supplementary Statistics. https://www.gov.scot/publications/pupil-census-supplementary-statistics/ (Last accessed on 15th April 2022)

- Slade, B. L., & Dickson, N. (2021). Adult education and migration in Scotland: Policies and practices for inclusion. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 27(1), 100–120. DOI:10.1177/1477971419896589

- Sousa, D. T., Wals, A. E. J., & Jacobi, P. R. (2019). Learning-based transformations towards sustainability: A relational approach based on Humberto Maturana and Paulo Freire. Environmental Education Research, 25(11), 1605–1619. DOI: 10.1080/13504622.2019.1641183

- Sowton, C. (2019). Language learning: Attitude, ability, teaching and materials in host and refugee communities in Jordan. British Council. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/language-learning-attitudes-jordan-2020.pdf

- Stewart, E.S. (2012). UK Dispersal Policy and Onward Migration: Mapping the Current State of Knowledge. Journal of Refugee Studies, 25(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fer039

- Thomas, M. S., Crosby, S., & Vanderhaar, J. (2019). Trauma-Informed practices in schools across Two decades: An interdisciplinary review of research. Review of Research in Education, 43(1), 422–452. DOI: 10.3102/0091732X18821123

- Tsimpli, I. M. (2017). Multilingual education for multilingual speakers. Languages, Society & Policy, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.9803