ABSTRACT

This study focused on the experiences of three Asian undergraduate students at a private urban institution in the United States. The findings indicate that the participants' racial, cultural and linguistic identities are dynamic and complex, echoing features indicated by the concept of superdiversity. Yet, under the influences of the rising nationalism and the strong grip of monolingualism, participants have been constantly under the pressure from English-only ideologies and the so-called forever-foreigner stereotype against Asian Americans. This study sheds light on rethinking higher education teaching and learning from the perspectives of marginalized students in the era simultaneously featuring superdiversity and nationalism.

本研究关注三名美籍亚裔本科生的经历。在民族主义抬头和单一语言意识形态的影响下,学生承受着亚裔是“永远外国人”刻板印象的压力。本研究在超级多样性和民族主义并存的时代,从边缘化学生的角度重新思考高等教育。

Introduction

The growing diversity and internationalization of higher education has called for researchers to go beyond the rigid native vs. nonnative speaker paradigm and investigate multilingual students’ languaging experiences through the lens of superdiversity (Vertovec, Citation2007). Highlighting the complexity of identity and the interplay of language, culture, race, and ethnicity among other factors, superdiversity emphasizes ‘the ways in which people take on different linguistic forms as they align and disaffiliate with different groups at different moments and stages’ (Arnaut et al., Citation2016, p. 26). This, along with recent nation-wide anti-racist movements in the United States, has led to a call for linguistic justice among students from marginalized backgrounds by pluralizing, localizing and racializing and decolonizing English (e.g. Baker-Bell, Citation2020; Cushman, Citation2016; Flores & Rosa, Citation2015). However, with the recent rise in nationalism and growing visibility of public discourses advocating monolingualism in the US (McIntosh, Citation2020), English-only ideologies are still rampant in American higher education (e.g. Kafle, Citation2020; Zhang-Wu & Brisk, Citation2021). Culturally and linguistically minoritized students, especially those of Asian descent, are subject to xenophobic and racist assumptions being regarded as forever-foreigners in American society (Chou & Feagin, Citation2015; Lo, Citation2016; Tuan, Citation1998), whose rich multilingual identities are often problematically minimized to linguistically incompetent English language learners (Zhang-Wu, Citation2018). How do students of Asian descent in American higher education make sense of their linguistic identities when the US faces rising nationalism? Specifically, what challenges do they encounter, if any, and how do they cope with them?

Informed by these questions, this exploratory qualitative study focused on the experiences of three undergraduate students of Asian descent at a private urban institution in the United States. The findings indicate that the participants’ racial, cultural and linguistic identities are dynamic and complex, echoing features indicated by the concept of superdiversity (Vertovec, Citation2007). Yet, under the influences of the rising nationalism and the strong grip of monolingualism in the US, participants have been constantly under the pressure from English-only ideologies and the so-called forever-foreigner stereotype against Asian Americans. Calling for American higher education curriculum to cultivate a space for inclusion, healing and empowerment and to acknowledge the experiences of minoritized students, this study sheds light on rethinking teaching and learning from the perspectives in the era simultaneously featuring superdiversity and nationalism in the US.

Language, nationalism, and English-only

Language and nationalism are closely interconnected. Hobsbawm (Citation1990) defines language as a ‘semi-artificial construct’ (p. 54) which justifies territory marking and power preservation. Language is neither natural or neutral; instead it is an artificially created form of social capital which is closely related to nation building and power reservation (e.g. Flores & Rosa, Citation2015; Makoni & Pennycook, Citation2007; Zhang-Wu, Citation2021a).

Research around the world has explored the relationship between language, power and nationalism. Some researchers focus on the power of language as a tool to exclude others and preserving national identities. For instance, analyzing news reports on immigration and immigrants among major right-wing media outlets in the UK and US, Jenks and Bhatia (Citation2020) examine how anti-immigration political ideologies are constructed through written language to preserve mainstream power and alienate migrants. Similarly, examining French and English texts from a corpus of Canadian newspapers, Vessey (Citation2014) discovers that languages function as boundary markers, and language choices are related to national group affiliation and sensemaking of belonging in Canadian society. Conversely, other researchers reimagine the possibility of hybrid languaging practices in transcending nationalist ideologies to facilitate international connections. For example, Tange’s (Citation2022) ethnographic study explores the role of hybrid cultural and linguistic practices in transcending nationalism, facilitating global consciousness and enhancing cosmopolitan learning.

In non-English speaking contexts, the global spread of English is often considered a threat to nationalism which is ‘detrimental to the national identity’ (Porto, Citation2014, p. 1). Substantial attention has been drawn to its influence as a ‘lingua frankensteinia’ (Phillipson, Citation2008, p. 250), perpetuating imperialist agendas through promoting English teaching and learning around the world (e.g. Flores, Citation2013; Tange & Jæger, Citation2021). Conversely, in the US, English is positioned as a static standard language and a tool to preserve nationalist power. From the perspective of superdiversity, this is ‘far too positive, narrow, and absolute’ by denying the dynamics of communication and agency during the languaging process (Arnaut et al., Citation2016, p. 26). While there is no official language by law, English is the de facto language of power, representing the nationalist discourse norms of ‘mainstream’ Americans (e.g. Flores & Rosa, Citation2015; Rosa & Flores, Citation2017). Particularly, with the rising nationalism fueled by recent changing political landscapes culminating in Trump’s presidency, the US witnesses growing public discourses advocating monolingualism (McIntosh, Citation2020). Consequently, despite the nation’s history which is largely defined by immigration and the recent multilingual turn in English teaching and learning (e.g. Cook, Citation2010; Garcia, Citation2009), nationalist English-only ideologies remain rampant in US contexts.

At the societal level, English-only is phrased in American federal and state-level educational policies (e.g. No Child Left Behind Act, Proposition 227 in California, Question 2 in Massachusetts) as a prerequisite for all students to achieve academic advancement and realize their American dreams. At the institution level, despite being the world’s top international student host country, English is still often problematically positioned as the one and only proper medium of communication (Zhang-Wu, Citation2022) and a gatekeeper for academic publication (Horner et al., Citation2011). At the individual level, American immigrant parents are under socioeconomic pressure to come up with family language policies in favor of English development and suppressing heritage language maintenance (Kaveh & Sandoval, Citation2020) to fit their children into the nationalist ‘mainstream.’

Asians in the USA: linguistically ‘Incompetent’ forever foreigners?

The recent rise in nationalism and growing public discourses advocating English-only (McIntosh, Citation2020) has led to growing linguistic racism against racially, culturally and linguistically minoritized populations in the US. Consequently, non-English languages and racialized varieties of English are subject to discrimination and exclusion due to white language supremacy (Inoue, Citation2019). Meanwhile, English communication from marginalized backgrounds is often stigmatized and under constant scrutiny from listening subjects who represent ‘standard’ English communication (Flores & Rosa, Citation2015; Rosa & Flores, Citation2017).

Among those who are racially, culturally and linguistically minoritized, individuals of Asian descent face additional layers of challenges due to the wide-spread stereotype positioning them as forever foreigners in American society (Chou & Feagin, Citation2015; Lo, Citation2016; Tuan, Citation1998). At the macro level, regardless of their length of residence in the US, citizenship and actual English proficiency, Asian Americans are often problematically regarded as linguistically deficient foreigners having questionable national loyalty, facing substantial difficulties in assimilation into the host country and posing potential threat to national security (Chou & Feagin, Citation2015; Lo, Citation2016; Tuan, Citation1998). The recent rising nationalist wave fueled by the Trump presidency and the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated such deficit stereotypes, leading to repeated hate crimes against Asian Americans (Stop AAPI Hate, Citation2022). At the micro level, due to the rampant nationalist ideologies and the strong grip of English superiority fallacy in the US, Asian kids and adolescents may develop heritage cultural and linguistic shame, who chose to conform to monolinguistic power to fit in (e.g. Zhang-Wu, Citation2021b, Citation2022).

In American higher education, despite the popular stereotype portraying Asians as smart, diligent and competent academically, their elite educational achievements hardly prevent them from discrimination (Lee & Ramakrishnan, Citation2018). Not only are Asian students often positioned as linguistically incompetent cash cows in American higher education (Zhang-Wu, Citation2021b), but also they are subject to institutional racism and marginalization. For instance, the chancellor at Purdue Northwest University openly mocked the Asian accent in his public speech during the 2022 graduation ceremony, leading to substantial backlash from the Asian community (Yang, Citation2022). Such discrimination also occurs when it comes to government-sponsored funding opportunities. A recent study conducted by the University of California Los Angeles analyzing the US National Science Foundation’s funding decision has revealed that over the past two decades Asian researchers consistently faced the lowest funding rate compared to applications from other racial categories, such as white, Hispanic/Latino, and black (Hewitt, Citation2022). This finding is especially concerning given the large presence of Asian Americans in US higher education, representing the highest college enrollment rate (82%) as compared with all other racial categories (Postsecondary National Policy Institute, Citation2022). Such a discrepancy between Asians’ low funding rate from US government and their high presence in American higher education again echoes the rampant forever-foreigner stereotype in society (Tuan, Citation1998).

Alim et al. (Citation2016) emphasize the importance to ‘answer critical questions about the relations between language, race and power’ (p. 3) amidst rising nationalism, rampant English-only ideologies and intersecting oppressions (Crenshaw, Citation2017) against Asian Americans. Furthermore, Canagarajah (Citation1995) points out the urgency to examine the interplay of language, race, power and identity at the individual and local level by focusing on the ‘lived, and experienced in the day-to-day life of the people and communities in the periphery’ (p. 592). Responding to these calls, this study draws upon the lived experiences of three Asian American students to investigate how they make sense of their linguistic identities amidst rising nationalism as well as challenges and opportunities that emerged in the process.

Methods

Research contexts and participants

This study occurred in an undergraduate elective course (Writing and DiversityFootnote1) offered by the English Department at a private urban research university on the east coast of the US in Fall 2020. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB #: 20-08-07). At the time of the study, I was the course’s instructor. Opening to all undergraduate students, the goal of Writing and Diversity was to raise students’ awareness of diversity and inclusion issues in and through literacy practices. Nineteen students enrolled in this course, among whom three (Ashly, Vicky, Emily) self-identified as Asian Americans (Japanese, Chinese and Korean American respectively) and were the focal participants of the present study. English major Ashly was a fourth-year undergraduate student while Data Science major Vicky and Biology major Emily were in their second year.

Data sources and analysis

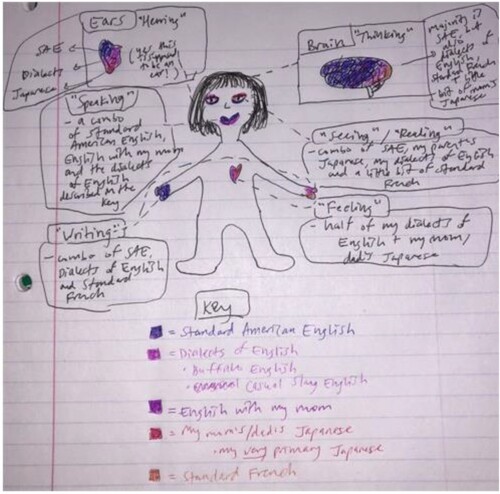

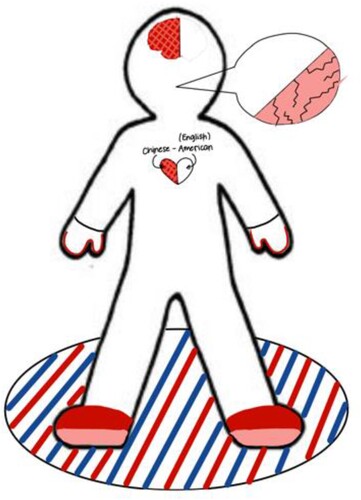

Data sources were collected from participants’ written coursework submitted through the university’s online learning system, including linguistic identity self-portrait drawings (N = 3), short written explanations describing their drawings (N = 3), and narrative essays about their racial, cultural and linguistic identities (N = 3). Linguistic identity drawings represented students’ creative self-portrait of their identities as communicators using colors and patterns (an example see ). Together with their drawings, students were asked to submit a short two-page essay to explain their self-portrait. Finally, based on their drawings and explanations, each student was asked to submit a narrative essay in reflection of their racial, cultural and linguistic identities. Throughout the process, participants were instructed to consider their racial, cultural and linguistic identities in light of their family linguistic history and heritage culture amidst rising nationalism.

Data were coded following the procedures recommended by applied thematic analysis (Guest et al., Citation2012). First, 32 content codes were assigned to the texts and drawings to make sense of data, such as heritage language maintenance, resistance, familial influence, English-only, bilingual, perception of identity as a child, perception of identity as an adult, dialects, culture shame, culture pride, forever foreigners, dual identity, differences as shame, differences as strength, and peers. After careful reading and re-reading, these codes fell into the following categories, which represent the main themes identified in the data: experiences with languages, identity sense-making, challenges encountered in navigating dual identities, and coping strategies developed to address the challenges. In the section below, I report findings based on how each student made sense of their identities amidst the rising nationalism, particularly in relation to the three themes identified.

Findings

Reflecting on their languaging experiences as children of Asian immigrants, Ashly, Vicky and Emily developed unique understandings of their dynamic and evolving cultural, racial and linguistic identities. Ashly discussed her journey from eagerly wanting to fit in with her peers by resorting to a monolingual English speaker identity to agentively reclaiming her multilingual and multicultural identity and resisting being positioned as a ‘token Asian friend.’ Vicky reflected on her lived experiences juggling the intricate relationship between language, race and power, and shuttling across English and various dialects of Chinese in search of her identity in American society. Emily focused on her shifting perceptions of her cultural, racial and linguistic identities, from being ashamed of her heritage to embracing her differences as strength. In their identity sense-making, the participants faced various challenges, especially regarding the forever-foreigner stereotype against Asian Americans and linguistic expectations from their peers. To cope with these challenges, they developed different coping strategies to navigate their dynamic cultural and linguistic identities.

Ashly: [R]esist[ing] the suffocating boxes that the world has tried so hard to shove me aside

Ashly joined Writing and Diversity during her last year as an undergraduate English major. Born in the United States to parents who were first-generation immigrants originally from Japan, Ashly’s identity sense-making journey went from a self-perceived monolingual English speaker eagerly seeking validation from her peers to an agentive Japanese-English bilingual who forcefully resisted the deficit stereotype of being a forever foreigner and ‘just someone’s token Asian friend.’

According to Ashly, when she was a child, her parents devoted relentless efforts to preserve their heritage language and culture. At home, they created a bilingual environment by trying to engage her in Japanese conversations and decorating numerous bilingual posters around the house (an example see ). When they were outside of the house, Ashly’s parents used to play Japanese CDs in the car and send her to heritage language classes every Sunday to create more language exposure and arouse her interest in Japanese.

Yet, regardless of her parents’ efforts, Ashly was not motivated to excel in Japanese. She described her heritage language proficiency as ‘very primary’ and considered herself a speaker of ‘変な日本語’ (awkward Japanese). Ashly reported feeling most comfortable communicating in English. According to Ashly, prior to taking this course, she used to self-identify as a monolingual English speaker who tried to distance herself from her Japanese heritage in response to rampant nationalist ideologies equating English as the only ‘official language’ in US society.

In her narrative essay, Ashly documented her reluctance to learn Japanese as a child, describing Japanese heritage language classes as ‘unimpressionable’ and ‘a burden’ and considering Japanese language learning as ‘not a priority for [her].’ Ashly explained that this was because as a child, she noticed that ‘[her] connections with [her] peers were strained with the burden of looking different’ and reported ‘envying [her] blue, wide-eyed’ peers. Recognizing that it was impossible to change her physical appearance to fit into ‘the white-washed world [she] was part of,’ Ashly aspired to become a monolingual English speaker just like her American classmates to seek validation from her peers and be accepted as a legitimate member in her friend circle.

However, as she grew up, Ashly’s high English proficiency did not shield her from substantial challenges posed by deficit racial stereotypes in American society, especially the rampant nationalist misconception considering Asian Americans as forever foreigners (Chou & Feagin, Citation2015; Lo, Citation2016; Tuan, Citation1998). Growing up, Ashly frequently received offensive questions such as ‘where are you really from,’ which she often responded with silence and a ‘political smile.’ Moreover, Ashly was assigned a ‘token label’ as ‘the Asian friend’ among a clique of white girls, receiving ‘back-handed compliment’ of being fluent in English or being pretty for an Asian.

According to Ashly, after taking Writing and Diversity and being pushed to critically examine her languaging practices and linguistic identities while ‘align[ing] and disaffliat[ing] with different groups at different moments and stages’ (Arnaut et al., Citation2016, p. 26), she realized the urgency to ‘resist the suffocating boxes that the world has tried so hard to shove [her] aside in ever since [she] was that little girl searching for a validation that is impossible to achieve.’ Recognizing that monolingual English speaker identity would never bring her full validation as an equal member among her peers, Ashly came up with the coping strategy of reclaiming her multilingual and Asian American identity as empowerment.

Reclaiming her multilingual and multicultural identity required Ashly to rethink her previously self-claimed monolingual English-only self through critical reflections of her daily languaging experiences. In her creative self-portrait of her linguistic identity (), Ashly was able to consider her linguistic identity beyond standard American English, the de facto official language of the country, and embraced other languages and varieties of English. As clarified in her short written explanation, beyond standard American English which helped her to meet the linguistic demands at school, Buffalo English, Slang English, English with her mother, her parents’ Japanese, her own limited Japanese as well as textbook French which she reported learning at school all played a role in shaping her sense-making and feeling of the world. It was worth noting that although reporting standard English as her strongest language, Ashly considered the dialects of English representing the community she grew up in and her parents’ Japanese as the linguistic resources that have touched her heart. According to Ashly, once she was able to distance herself from a monolingual, monocultural identity eager to seek validation from her peers, she found strength in her rich linguistic repertoire and unique cultural heritage as resistance to break the nationalist stereotype, or what she referred to as a ‘suffocating box’ that others had forced her into. Rather than hiding her multilingual and multicultural identity under the mask of English-only to seek validation from the mainstream American society, Ashly started to take pride in her differences as strength after joining Writing and Diversity:

Instead of answering for my mother when the grocery clerk refuses to look past her accented English and turns to me for the “translation,” I let my mother speak for herself. Instead of politely laughing when a person has the nerve to ask me, “where are you really from,” I respond with a confidence that may make them uncomfortable, but puts them in their rightful place.

Vicky: [A]n ABC will always be an ABC

Second-year undergraduate student Vicky was a Data Science major. Vicky self-identified as a Chinese American who was born and raised in the US to parents who were first-generation immigrants from Taishan, China. Vicky described herself as a multilingual communicator, shuttling back and forth across English and three varieties of Chinese (Mandarin, Cantonese and Taishanese) in her everyday life. According to Vicky, her cultural and linguistic identity was highly fluid, as she had to constantly juggle with uneven power relations across the four linguistic varieties shaping her daily languaging practices based on communicative contexts and interlocutors. While Vicky reported that she used to be confused about her complex linguistic identity, she eventually embraced the dynamics of her identity as an ‘ABC’ (American-born Chinese) and appreciated Chinglish, or an unsystematic mixture of Chinese and English, as the bridge between her Chinese and American identities.

Vicky reported that ever since she was a child, she had encountered substantial challenges with the overly-simplified umbrella term of ‘Chinese American’ due to the complicated interrelationships between language and power. As explained in her narrative essay, Vicky’s parents were first-generation immigrants from Taishan, a small city in Guangdong Province, China. For generations, Taishan has been the ‘No. 1 Home of Overseas Chinese,’ though Chinese Americans from Taishan are often known as blue-collar immigrant labors working at the bottom of US society (Pierson, Citation2007). Echoing findings from previous research (Leung, Citation2010), Vicky pointed out that although Taishanese, Cantonese and Mandarin were all considered Chinese, these dialects and their speakers held drastically different social capitals. While Tainshanese and its users often stereotyped as being somewhat less cultured (Leung, Citation2010), Mandarin and Cantonese were often considered linguistic varieties that could elevate ‘one’s place in [their] political economic system’ whose speakers were ‘permit[ted] full participation in the capitalist economy’ (Kroskrity, Citation2001, p. 503).

According to Vicky, because of the widely-known stereotype associating Chinese immigrants with Taishanese origin as uneducated, low-skill workers, her parents who themselves were workers at Chinese restaurants with very limited English proficiency, tried to minimize talking to her in Taishanese at home. Instead, they preferred communicating with Vicky in English, Cantonese, or Mandarin, hoping to prevent her from being discriminated racially and ethnically. In her narrative essay, Vicky reflected on her unique experiences growing up with ‘broken English’ and ‘broken Chineses’ given her simultaneous exposure to English, Cantonese, Mandarin and Taishanese. According to Vicky, growing up, although she picked up some Taishanese by communicating with members in her extended family, she failed to develop high proficiency in her heritage language due to the lack of exposure. While she was immersed in a rich linguistic environment hearing English, Cantonese and occasionally Mandarin at home, due to her parents’ limited proficiency in these languages, she failed to master any particular dialect. Vicky claimed that being exposed to multiple languages had crippled her ability to express herself as a child relying heavily on Chinglish, mingling all linguistic resources she possessed to fulfill communicative purposes. It was not until when she attended school that she finally developed high proficiency in one language – English.

Vicky reported in her narrative essay that her lived experiences juggling multiple language varieties and trying to understand their power relations have posed significant challenges for her to make sense of her identity as a Chinese American with Taishanese heritage. On the one hand, due to her parents’ language ideologies and family language policy, she lacked sufficient proficiency in any Chinese dialects, making it difficult to fully embrace her Chinese heritage. Additionally, Vicky recalled that her parents ‘always push[ed] [her] boundaries of being Chinese American by shaping [her] to be whitewashed’ for the sake of ‘surviving in an American society’ and realizing ‘[her] American dream’ (emphasis added). Vicky explained that to make her fit into the ‘mainstream’ American society dominated by whiteness and English-only, her parents put heavy emphasis on her English development ever since she was young. For instance, Vicky recalled that despite of her parents’ low English proficiency, they tried their best to read her English bedtime stories every night. On the other hand, Vicky reported feeling caught by the dilemma of being a Taishanese yet being discouraged to associate with this heritage. Due to the negative social stereotype on Taishanese speakers and her parents’ language ideologies, Vicky developed ethnic shame as a child, who often ‘asked [her]self if [she] wanted to even associate [her]self with the Taishanese culture.’ Self-perceived as ‘a Taishanese fraud,’ Vicky described her lack of belonging when walking in Chinatown:

[M]y people roamed the streets and buildings, filling the space with Taishanese language and culture, yet I never sensed a belonging there – as a Taishanese fraud. I knew that my limited Chinese-speaking skills would hinder my flow of casual conversations with those who only knew how to speak Chinese, but, more importantly, my connection to my Chinese identity as a Chinese American.

Instead of being confused by her conflicting identities and feeling ashamed by her ‘broken’ Chinese and English, Vicky found strength in her in-betweenness as a Chinese American thanks to reflections in this course. As she wrote, ‘[A]n ABC will always be an ABC.’ Instead of forcing herself into mainstream Chinese or American communities, she could navigate unequal power relations to function linguistically across contexts by negotiating identities and taking pride in her unique Chinglish articulation, thinking and feeling (see in pink). As illustrated in her linguistic portrait, embracing her dynamic Chinese heritage (red in feet) and her Chinglish (pink in feet), she proudly stood on the ground marked by the three colors of American flag.

Emily: You can never understand one language until you understand at least two

Second-year undergraduate student Emily was a Biology major who was born in the US to first-generation immigrant parents who had left South Korea as teenagers. Emily self-identified as a Korean American, multilingual in Korean, English, and Konglish, which she defined as her ‘own unique mix of Korean and English that [she] switch[s] around whenever the situation calls for it.’ Emily’s identity journey shifted from regarding her Korean heritage as a shame to embracing and reclaiming it as a pride.

Emily mentioned that, when she was young, she used to be ashamed of her Korean identity who wished to speak ‘white English’ like her peers and hide traces of her heritage roots in order to break the forever-foreigner stereotype against Asians and fit into American society. This was despite her parents’ efforts to maintain their cultural roots by mandating Korean as their home language and spending substantial time in heritage language homeschooling. Emily reflected in her narrative essay that in her childhood, she used to deny her racial, cultural and linguistic differences by ‘hid[ing] the fact that [she] was able to speak a language other than English,’ ‘responding to [her] parents’ Korean questions in English in front of [her] friends’ and ‘refus[ing] to tell others [her] middle name, which was also [her] Korean name.’ Moreover, during her childhood, despite her ability to carry out basic conversations in Korean, Emily tried to limit her Korean conversation with relatives to simple phrases such as ‘네’ (yes) and ‘아니요’ (no). Emily believed that such decisions of limiting Korean usage ended up resulting in her ‘more and more distant’ relationship with her grandparents.

However, regardless of her efforts to suppress her Korean identity to cultivate a ‘mainstream’ American identity, Emily reported facing substantial challenges in seeking acceptance by her peers; growing up, she was constantly positioned as an exotic outsider. Emily recalled that despite attending a predominantly white, English-only elementary school, her peers never accepted the ‘authentic English speaker’ identity that Emily had hoped to create for herself. Instead, she was often requested by peers to ‘say something in Korean’ in front of the class: ‘I felt vulnerable, as if my bilingualism was something to be put on display.’ Similarly, although she tried hard to ‘live a double life’ during adolescence by hiding her heritage and ‘immers[ing] [her]self in American pop songs and TV shows in order to keep up in conversation with other kids,’ Emily reported being often alienated by her peers who expected her to have extensive knowledge about Korean dramas and movies instead.

To cope with her challenges, Emily decided to seek socioemotional support from peers in the larger Korean-American community. During high school, she joined a local Korean-American youth group, which connected her with many youths in the neighborhood who shared the same cultural and linguistic heritage with her. According to Emily, finding such a community was an empowering and liberating experience:

This was the first time that I felt a hint of pride in my Korean identity, as I could find a common culture with the rest of them. I was able to relate about different favorite foods, casually joke in our [heritage] language and refer to Korean pop culture … For me, it felt like I was switching to a language where I didn’t have to suppress anything nor live a double-life. It was a freeing, foreign experience that I felt myself slowly being immersed into.

While Emily reported feeling ‘intimidated’ by her ambition to re-learn Korean in college, feeling ‘too old to learn a language,’ she reminded herself that it was around this age that her parents first immigrated to the US and started learning English; if they were able to concur the difficulties to master English and find jobs in English-only environment, there should be no excuse for her to feel hesitant in reclaiming her Korean identity. Through her hard work, Emily’s literacy skills in Korean improved significantly; she reported even being able to read simple children’s literature in Korean recently. According to Emily, her progress in heritage language learning has made her appreciate multilingualism and develop deeper understanding of the famous saying: ‘최소 두 가지 언어를 이해할 때까지 결코 한 언어도 이해하지 못한다’ (You can never understand one language until you understand at least two).

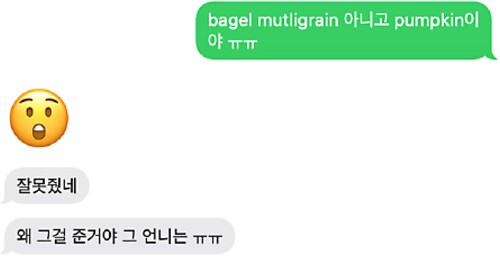

Although it may take time before Emily’s Korean proficiency could be sufficient to engage in in-depth conversations and literacy practices, Emily was able to rely on Konglish, a ‘secret language that [she] was no longer ashamed of’ to bring together all her linguistic resources in English and Korean for meaning-making. In college, beyond often ending phone calls with translingual expressions such as ‘아빠, I love you’ (Daddy, I love you), Emily also found herself frequently resorting to Konglish in text messaging (). As indicated in her creative self-portrait (), although being trained to mainly engage in written communication in English at school (hands with patterns mirroring the American flag), Emily relied on Konglish to stand up for herself (mixed color on feet) and embrace her pride as a Korean American (see Korean placed as the language of her heart).

Discussion

Echoing the concept of superdiversity (Vertovec, Citation2007), despite the three participants’ identical racial category, their identities dynamically interplayed with their languaging experiences, family migration and linguistic history, power relations, and experiences with mainstream listening subjects (Flores & Rosa, Citation2015; Rosa & Flores, Citation2017). While all fell under the broad category of Asian Americans and shared some similarities in their languaging practices growing up, Ashly, Vicky and Emily experienced different challenges making sense of their racial, cultural and linguistic identities. For example, while Ashly faced the difficulty of being pushed into a ‘suffocating box’ of ‘token Asian friend’ among her peers, Emily was constantly positioned as an exotic outsider and an expert of Korean language and culture. Additionally, Vicky’s journey growing up juggling with the intricate power dynamics among the three dialects of Chinese (Taishanese, Cantonese and Mandarin) as well as their different social capitals associated with their speakers has further illustrated the within-group superdiversity complicating our understanding of the over-simplified umbrella term ‘Chinese American.’

Across the three cases, language and nationalism have been closely interrelated. In particular, English has played an important role in preserving nationalist power while othering minoritized populations (Makoni & Pennycook, Citation2007; McIntosh, Citation2020). Ashly, Vicky and Emily, who ended up developing native-like proficiency in English, all perceived mastering English as a crucial way to integrate into the mainstream society and seek acceptance from their peers. Yet, they still suffered from nationalist ideologies in the US being positioned as linguistically incompetent forever foreigners due to their Asianness (Chou & Feagin, Citation2015; Lo, Citation2016; Tuan, Citation1998). This echoes the concept of raciolinguistics (Flores & Rosa, Citation2015; Rosa & Flores, Citation2017), according to which people of color’s communicative practices and linguistic repertoires were often stigmatized, problematized and marginalized regardless of their English proficiency. As a result, the participants were constantly subject to white gaze and judgement from mainstream listening subjects (Flores & Rosa, Citation2015), facing sharp questions interrogating where they were really from (Ashly), were expected to be able to know heritage language and culture well (Vicky, Emily), and were not fully accepted as a member of the mainstream group (Ashly, Vicky, Emily).

Yet, from the perspective of superdiversity, such rigid ethnic profiling is ‘especially problematic’ (Arnaut et al., Citation2016, p. 34), given the dynamic process of doing identities and languaging across cultures and contexts. Responding to such challenges, the participants came up with different coping strategies in order to reclaim identity (Ashly), appreciate in-betweenness (Vicky), and cultivate heritage pride (Emily). Rather than denying their identities and forcing themselves to seek acceptance the mainstream group, Ashly, Vicky, and Emily rediscovered strength in their differences through conducting critical reflections, resorting to Asian American literature, and seeking empowerment from peers within the ethnic group. Rejecting her assigned identity by her peers as a ‘token Asian friend,’ Ashly conducted critical reflections of her languaging practices across contexts and eventually managed to notice how her self-claimed monolingual identity has masked her rich linguistic resources and reclaim her multilingual, multicultural self. Lacking a sense of belonging to either the mainstream or ethnic groups, Vicky resorted to Asian American literature for empowerment who eventually appreciated her fluid in-betweenness as an ‘ABC’ shuttling freely across all resources in her linguistic repertoire. Feeling alienated by her peers as a representative of Korean language and culture instead of a legitimate member of the mainstream group, Emily joined a Korean youth group, through which she found her community, developed heritage pride, endeavored to re-learn Korean and re-negotiate her multilingual identity.

Implications

This study focused on the lived languaging experiences of three Asian American students to explore how they make sense of their identities, the challenges they have encountered in the process as well as their corresponding coping strategies. The findings of the study shed important light on American higher education teaching and learning. One may argue that Asians are somewhat less minoritized compared with other racialized groups in the US given their status as the ‘model minority.’ Yet, with former US president Trump referring to the COVID-19 global pandemic as a ‘Chinese Virus’ and a ‘Kung Flu,’ Asian Americans were victimized by violent hate crimes (Stop AAPI Hate, Citation2022), denied legitimacy as American citizens, and othered as foreigners who posed threat to national security (Moynihan & Porumbescu, Citation2020). This makes it urgent to support Asian American students amidst rising nationalist sentiment in society.

Since in the US nationalist ideologies are often passed down through the educational system in the form of language policies (see in literature review), advocacy work for culturally, racially and linguistically minoritized students must also start in schooling. American higher education instructors should be provided professional development opportunities to learn about important concepts such as superdiversity and the interrelationship between language and nationalism so as to understand the unique challenges facing Asian Americans to support them accordingly. Furthermore, it is necessary to cultivate a space for inclusion, healing and empowerment in American higher education curriculum, such as that created in Writing and Diversity, to acknowledge the experiences of Asian American students by encouraging multilingual/translingual meaning-making to decenter English-only (Ashly, Vicky and Emily’s coping strategy), incorporating Asian American literature and scholarship (Vicky’s coping strategy), encourage deep conversations and critical reflections to problematize decades-long deficit stereotypes positioning them as linguistically deficient forever foreigners (Ashly’s coping strategy), and to create a community to bring together Asian American students on campus to facilitate heritage pride (Emily’s coping strategy).

With the rising superdiversity in American higher education, nationalist ideologies, especially the forever-foreigner stereotype against Asian Americans, still pose challenges in racially minoritized students’ identity sense-making. Echoing Canagarajah’s call (Citation1995), this study explored three Asian American students’ lived experiences as the first step to advocate for them. The findings of the study highlight the complexity and interrelationship among language, race, power and nationalism. This study draws implications on inclusive pedagogy in American higher education.

Despite its potentials, the present study is limited by its small sample size and contextualized nature. While the intention of this exploratory qualitative study has never been to seek generalizability, but instead to understand lived everyday languaging and identity sense-making experiences among minoritized individuals, future research could adopt survey methods to recruit a larger pool of participants to further explore superdiversity among Asian Americans. Moreover, since the three participants in this study are all 2nd generation immigrants, their parents may be relatively attached to their heritage culture and language which could skew their identity sense-making. Echoing Arnaut et al.’s (Citation2016) call to explore superdiversity across the generations, it would be worthwhile for future research to adopt ethnographic methods to compare the identity negotiation, challenges and coping strategies between recent Asian immigrants with those whose families have been in the US for generations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Qianqian Zhang-Wu

Qianqian Zhang-Wu is Assistant Professor of English and Director of Multilingual Writing at Northeastern University, USA. Her research focuses on multilingualism and multiliteracies. Zhang-Wu is author of the book Languaging Myths and Realities: Journeys of Chinese International Students (Multilingual Matters, 2021). Her work appears in edited collections and peer-reviewed journals including TESOL Quarterly, College English, Journal of Language, Identity and Education, Composition Forum, Journal of Education, Journal of International Students among others. Zhang-Wu is recipient of AERA Travel Award, CNV fellowship at the NCTE Research Foundation, CCCC Scholar for the Dream, Best Dissertation Award and Best Book Award at CIES.

Notes

1 Pseudonyms were used throughout the study to protect participant privacy.

References

- Alim, H. S., Rickford, J. R., & Ball, A. F. (2016). Raciolinguistics: How language shapes our ideas about race. Oxford University Press.

- Arnaut, K., Blommaert, J., Rampton, B., & Spotti, M. (Eds.). (2016). Language and Superdiversity. Routledge.

- Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge.

- Canagarajah, A. S. (1995). Review. Language in Society, 24(4), 590–594. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500019102

- Chou, R. S., & Feagin, J. R. (2015). Myth of the model minority: Asian Americans facing racism. Routledge.

- Cook, G. (2010). Translation in language teaching: An argument for reassessment. Oxford University Press.

- Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press.

- Cushman, E. (2016). Translingual and decolonial approaches to meaning making. College English, 78(3), 234–242.

- Flores, N. (2013). The unexamined relationship between neoliberalism and plurilingualism: A cautionary tale. Tesol Quarterly, 47(3), 500–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.114

- Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149

- Garcia, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. SAGE Publications.

- Hewitt, A. (December 5, 2022). NSF awards funding to white scientists at higher rates than other groups, study shows. UCLA Newsroom. https://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/national-science-foundation-funding-race-ethnicity.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. (1990). Nations and nationalism since 1780: Programme, myth, reality. Cambridge university press.

- Horner, B., NeCamp, S., & Donahue, C. (2011). Toward a multilingual composition scholarship: From English only to a translingual norm. College Composition and Communication, 63(2), 269–300.

- Inoue, A. B. (2019). How do we language so people stop killing each other, or what do we do about white language supremacy. College Composition and Communication, 71(2), 352–369.

- Jenks, C. J., & Bhatia, A. (2020). Infesting our country: Discursive illusions in anti-immigration border talk. Language and Intercultural Communication, 20(2), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2020.1722144

- Kafle, M. (2020). “No one would like to take a risk”: Multilingual students’ views on language mixing in academic writing. System, 94, 102326. https://search.crossref.org/?q=%E2%80%9CNo+one+would+like+to+take+a+risk%E2%80%9D%3A+Multilingual+students%E2%80%99+views+on+language+mixing+in+academic+writing&from_ui=yes#

- Kaveh, Y. M., & Sandoval, J. (2020). No! I’m going to school, I need to speak English!: Who makes family language policies? Bilingual Research Journal, 43(4), 362–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2020.1825541

- Kroskrity, P. (2001). Language ideologies. In A. Duranti (Ed.), Linguistic anthropology: A reader (pp. 496–517). Wiley Blackwell.

- Lee, J., & Ramakrishnan, K. (March 27, 2018). Op-Ed: Asian Americans think an elite college degree will shelter them from discrimination. It Won’t. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-lee-ramakrishnan-asian-american-prestige-20180327-story.html.

- Leung, G. Y. (2010). Learning about your culture and language online: Sifting language ideologies of hoisan-wa on the internet. Working Papers in Educational Linguistics (WPEL), 25(1), 37–55.

- Lo, A. (2016). “Suddenly faced with a Chinese village”: The linguistic racialization of Asian Americans. In A. Samy, J. Rickford, & A. Ball (Eds.), Raciolinguistics: How language shapes Our ideas about race (pp. 97–111). Oxford University Press.

- Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (Eds). (2007). Disinventing and reconstituting languages. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853599255

- McIntosh, K., ed. (2020). Applied linguistics and language teaching in the neo-nationalist era. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moynihan, D., & Porumbescu, G. (September 16, 2020). Trump’s ‘Chinese virus’ slur makes some people blame Chinese Americans. But Others Blame Trump. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/09/16/trumps-chinese-virus-slur-makes-some-people-blame-chinese-americans-others-blame-trump/.

- Phillipson, R. (2008). Lingua franca or lingua frankensteinia? English in European integration and globalisation. World Englishes, 27(2), 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2008.00555.x

- Pierson, D. (2007, May 21). Taishan’s U.S. well runs dry. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2007-may-21-fg-taishan21-story.html.

- Porto, M. (2014). The role and status of English in Spanish-speaking Argentina and its education system: Nationalism or imperialism? Sage Open, 4(1), 2158244013514059. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013514059

- Postsecondary National Policy Institute. (2022, May 11). Asian American and Pacific Islander Students. https://pnpi.org/asian-americans-and-pacific-islanders/.

- Rosa, J., & Flores, N. (2017). Unsettling race and language: Toward a raciolinguistic perspective. Language in Society, 46(5), 621–647. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404517000562

- Stop AAPI Hate. (2022, May 28). The rising tide of violence and discrimination against Asian American and Pacific Islander women and girls. https://stopaapihate.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Stop-AAPI-Hate_NAPAWF_Whitepaper.pdf Accessed 5 June. 2022.

- Tange, H. (2022). Banal nationalism and global connections: the 23rd World Scout Jamboree as a site for cosmopolitan learning. Language and Intercultural Communication, 22(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2021.1912067

- Tange, H., & Jæger, K. (2021). From Bologna to welfare nationalism: international higher education in Denmark, 2000–2020. Language and Intercultural Communication, 21(2), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2020.1865392

- Tuan, M. (1998). Forever foreigners or honorary whites?: the Asian ethnic experience today. Rutgers University Press.

- Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and Its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701599465

- Vessey, R. (2014). Borrowed words, mock language and nationalism in Canada. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14(2), 176–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2013.863905

- Yang, M. (December 15, 2022). Purdue Northwest chancellor sorry for mocking Asian language in speech. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2022/dec/15/purdue-northwest-chancellor-apology-mocking-asian-language.

- Zhang-Wu, Q. (2018). Chinese international students’ experiences in American higher education institutes: A critical review of the literature. Journal of International Students, 8(2), 1173–1197. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v8i2.139

- Zhang-Wu, Q. (2021a). (Re)Imagining translingualism as a verb to tear down the English-only wall: “monolingual” students as multilingual writers. College English, 84(1), 121–137.

- Zhang-Wu, Q. (2021b). Languaging myths and realities: Journeys of Chinese international students. Multilingual Matters.

- Zhang-Wu, Q. (2022). Keeping home languages out of the classroom’: Multilingual international students’ perceptions of translingualism in an online college composition class. Journal of Multilingual Theories and Practices, 3(1), 146–168. https://doi.org/10.1558/jmtp.21280

- Zhang-Wu, Q., & Brisk, M. E. (2021). “I must have taken a fake TOEFL!”: Rethinking linguistically responsive instruction through the eyes of Chinese International Freshmen. TESOL Quarterly, 55(4), 1136–1161. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3077