ABSTRACT

To facilitate intercultural communicative competence, language learners are invited into the triadic capacity of Thirdness, where the social and critical interpretations of intercultural dialogue are explored. Little is known of the specific pedagogical stages to create such a terrain for the development of students’ sustainable intercultural competence. Situated within a tertiary-level English classroom in China, this study reveals how teachers can employ five pedagogical stages and humanised pedagogy to decentre cultural imperialism and promote plural values, behaviours and ways of knowing, and how students relativise their own beliefs to those of the target language culture.

为提高跨文化交际能力,语言学习者被邀请进入第三空间,探索如何用批判性语言文化立场视角深入开展跨文化对话。尽管第三空间理论为跨文化交际提供了概念化的理论视角,但少有研究关注如何在课堂上运用具体的教学手段促进学生对文化相对主义的理解和对可持续跨文化能力发展的培养。作者探究了在中国高等学校英语课堂上,揭示教师是如何有效运用五个具体教学阶段和人性化教学法来打破文化帝国主义,促进学生多元价值观和对文化的认知,以及学生如何将自己的价值信仰与目标语言文化进行对比与关联。

Introduction

As new varieties of English emerge and evolve around the world, English as a Lingua Franca (ELF)-oriented teaching has been widely recognised as a fluid paradigm that focuses on bilingual and multilingual students’ intercultural communicative competence (Patrão, Citation2018). ELF-oriented teaching proposes a paradigm shift that helps students critically reflect on the ownership of English to garner a more pluricentric view of language and cultural differences. Language and culture are incontrovertibly interconnected, and culture study is an essential component for mastering a foreign language. Although the ELF lens is widely acknowledged, language teachers still tend to unconsciously employ a ‘target culture teaching’ approach that reinforces the dominant cultural narrative, treating Western culture as a monolith (Kramsch, Citation1999; Núñez-Pardo, Citation2018) in a way that promotes cultural imperialism and hegemony. In light of the ineffectiveness of target culture teaching, scholars and teachers have begun to ponder how to allow more cultural ‘crowdsourcing representations’ (Constantinidis, Citation2016) and create a potential inspiring terrain where the process of negotiating and mediating cultural multivoicedness and new ways of interpretation and analytic reflection can be promoted both cognitively and affectively, as linguacultural study involves the cognitive mapping of rational analysis, inference as a schematic restructuring, and emotional interplay with sociocultural-mediated factors. The capacity of Thirdness opens a potential triadic reconceptualised landscape for critical intercultural communication and meaning-making where students can think about cultural likenesses and oppositions relating to the self and others from the metaphorical outsiders’ perspective. Language study is no longer a process of target language and culture assimilation but of exploring, negotiating, and mediating linguacultural commonality and difference. It is through such ‘cultural thirdness’ that students go beyond the dyadic matrix and concerns, tapping into a symbolic triangular landscape that deepens their awareness of language ownership and cultural relativity.

The importance of helping students explore circulations of multiple values among cultures is acknowledged, but how to pedagogically enact a ‘critical’ stance when constructing intercultural communication in this imagined third terrain still needs to be envisioned. Scant research has explored how language teachers can establish instructional stages to promote critical mindset interrogation and expansion facilitating cultural equity in a space where commonality, difference and Thirdness are closely intertwined and valued. Situated within a tertiary-level English classroom in China, this study explores how teachers employ five pedagogical stages to promote critical intercultural dialogue and hybrid meaning-making, helping students locate ‘difference-in-similarity’ (Canagarajah, Citation2013, p. 4). This research examines how critical dialogue about difference and incompatibility can potentially facilitate a transformative third perspective and eventually lead to new insights, facilitating students to share and embrace greater responsibility for possible future action (Anderson, Citation2019). The study adds to the larger body of work regarding how humanised pedagogy, sociocultural affordances and critical linguacultural otherness awareness help students enact a richer cultural identity, constructing a more critical stance in intercultural communication and eventually moving towards sustainable intercultural practices and competence.

Literature review

Interculturality and critical interculturality

Wen (Citation2016) emphasises that to promote students’ cross-cultural communication competence, it is necessary to deal wisely with the interconnectedness of native culture (C1), target culture (C2), and the cultures of other countries. However, the misunderstanding of teaching C2 is prominent, as the assumption that C2 is to be acquired will not lead to deep understanding for culture inquiry and dialogue (Holliday, Citation2017). Instead of a ‘target culture teaching’ approach, scholars advocate a shift from treating C2 as monolithic to a new paradigm of culture education encompassing intercultural dialogue, mutual understanding, communicative skills and attitudes that will serve students beyond the classroom (Piller, Citation2017). The prefix ‘inter’ emphasises communication between cultures to empower students to explore how people operate knowledge, attitudes and skills under mutual interaction. It begins with recognising students’ own underlying language ideology, agency and cultural dispositions; then, with target cultural encountering, the interaction and negotiation of both languages and cultures are leveraged and mediated to reimagine and rethink the communicative dialogues, where implicit cultural identity, power relations and linguistic ideology are inherently embedded (Ou & Gu, Citation2020). From the lens of interculturality, language education is much more than language itself; instead, it is an intercultural practice wherein each language and culture are recognised as valuable resources to promote cultural intelligence and competence and, more importantly, explore how dynamic power relationships, complex identity positions and linguistic ideology are negotiated throughout the process.

The term ‘critical interculturality’ was originally defined by Tubino (Citation2004) and Walsh (Citation2009, Citation2018) to investigate how cultural discrepancy has been constructed within a colonial framework in the context of Latin American schools and communities. The principle mainly examines the cultural issue from a distinct viewpoint of ‘otherness’ that advocates a symmetrical and critical cross-cultural dialogue recognising the cultural kaleidoscope and epistemic diversity of others. To facilitate students’ preparedness to engage in ‘intercultural dialogue as a political and ethical response to the thirdness in the in-between space of communication’ (Zhou & Pilcher, Citation2019, p. 13) that challenges existing mechanisms, educators must first help students identify with and maintain pride in their home cultures to strategically create communicative space and highlight critical consciousness to bring language in its fullest ‘critical’ sense to the plurilingual classroom. Another important perspective when framing the notion of ‘criticality’ is to enable learners to think about different aspects of the culture in which they live in order to bring transformational change where change is needed (Badwan & Simpson, Citation2019). Criticality rejects striving for neutrality and pure objectivity, as the destination is not to be neutral but to make the world a more just place (Granados-Beltrán, Citation2016). Therefore, it can be inferred that critical interculturality seeks a mission of linguacultural criticality that involves the impact of imbalances of power and complex identity construction in language learning and teaching practices, and a call for enacted action (Banegas & Villacañas-de-Castro, Citation2016). Critical interculturality amplifies interest in other countries from a critical stance, raising cultural understanding and tolerance, and reinforcing cultural conceptualisation in multiple ways and connections. It challenges the traditional static, monolithic view of language and cultural studies, proposing a relational, situated, ecological view of seeing and knowing, with the responsibility to stand up to bias, exclusion and prejudice in order to maintain social justice (Chun & Evans, Citation2016).

Thirdness

It is widely recognised that critical engagement with other perspectives involves transcending the boundaries between dyadic ways of seeing the world. The attempt to explore and conceptualise possibilities for a more diverse, reflexive and multi-voiced positionality requires the capacity of a triadic and relational space of reflection. ‘Shared Thirdness’ provides such a triadic lens and opens a place for thinking and relating the self and the other in a hybrid process of meaning-making and negotiation. The notion of Thirdness has been increasingly utilised to break up the archaic dualistic formulation of thinking, extending well beyond the dyad to embrace multiple potentially conflicting encounters. Under this overarching position of ‘shared Thirdness’, exemplar metaphorical terms include Third Space, Third Place, and Third Culture, together creating a domain of shared being with mutual communicative and reflective synthesis upon the self and encounters with others.

The primary capture of Thirdness is embodied in Third Space, the influential term developed by Homi K. Bhabha (Citation1988, Citation1994) in which he delineates the third spatial awareness of the in-between, hybridity on the borderline. According to Bhabha’s, Citation1994 book The Location of Culture, ‘third space is an ambivalent site where cultural meaning has no primordial unity or fixity’ (p. 37). He denotes the cultural meanings in heterogeneous Third Space as ‘otherness’ and offers a lens through which people can explore the space to reimagine the hybrid self beyond the parochial dichotomy. Bhabha contests the ‘centred causal logic’ (p. 141) in cultural formations characterised by unchanging order with archaic dualistic rigidity; instead, he brings people to ‘the beyond’ space, using concepts such as ‘interstice’ and ‘liminality’ to denote the boundary and in-between positions fraught with hybridity, contingency, and ambiguities. The theory of Third Space is widely used in foreign language education and intercultural and cross-border educational studies. According to Cho (Citation2016), the Third Space in language and cultural education is a critical space of consciousness, and, as it is virtual, metaphorical and fluid, the space is open to all possibilities. In such a space, people are neither to be ‘rejected’ nor ‘assimilated’; instead, the space emphasises the equal integration of L1/C1 and L2/C2 during the dynamic, formative production process and changes the isolated state of language and culture into an aggregated state, forming a synergy effect of ‘1 + 1 > 2’ (Ye & Wang, Citation2016). Although Bhabha’s Third Space is widely acknowledged, certain critical interpretations of the concept of Third Space assert that struggles, tensions, and confrontations in the historical colonial situation are in danger of being forgotten with Bhabha’s constant emphasis on hybridity and self-interpretative ambiguity (Dirlik, Citation1997; MacDonald, Citation2019; Moore-Gilbert, Citation1997). In addition, people navigating multiple cultures can feel pressured to express themselves in a hybrid way to be socially acceptable: they can be multicultural, certainly, but not too C1 and not too C2. As colonialism is baked into much of what humans do and think and is hard to unlearn, people with anti-colonialist intensions can fall into the trap of dictating how multicultural someone else is allowed to be. What is more, scholars also raise the issue of who should serve as the responsible subject to open such a space for the third to be mediated by and accommodated into the dyadic matrix (Mizutani, Citation2013). Critiques of such postcolonial Third Space also relate to Bhabha’s pursuit of Eurocentric bias legitimising the dominant Eurocentric discourses, which is contradictory to the construction of the periphery grounded in postcolonial theory. There is concern that Bhabha’s concept of hybridity itself is potential essentialist positionality, creating discrete communities with certain minority cultures to be regarded as rivals to the dominant culture, contributing to the marginalisation of particular practices and groups (MacDonald, Citation2019).

Another connotation of shared Thirdness is embedded in the term Third Place. In his Citation1989 book The Great Good Place, sociologist Ray Oldenburg coins and defines the concept of Third Place as the informal public social space that exists outside home (the first place) and the workplace (the second place), a crucial realm where people can be themselves and experience both individual well-being and fellowship in community. Anthropologist and linguist Kramsch (Citation1993) applied the concept in the field of foreign language teaching and cross-cultural communication, defining Third Place as a terrain where students perform fluid, hybrid, dynamic cultural and linguistic practices, honing a deeper understanding of confined boundaries. Kramsch argued against the traditional binarism between L1 and L2 and their cultural counterparts C1 and C2, advocating an intercultural third position ‘carving out against the hegemonic tendencies of larger political and institutional structures’ (Citation1993, p. 247), where learners’ perceptions can be socially recognised, constructed, mediated and accepted. Over time, Kramsch’s ideas about Thirdness changed, however, evolving from fostering intercultural communicative competence and critical possibilities in the Third Place to orientating further into a symbolic dimension of Thirdness that she calls ‘symbolic competence’ (Citation2006, p. 251). The prevalence of symbolic value representation and genuine symbolic dimensions of Thirdness goes beyond understanding and empathy for self and others, highlighting the need to reframe and refract discursive practices beyond words and actions, embracing a ‘relationship of possibility’ (Kramsch & Whiteside, Citation2008, p. 664). Going beyond dyadic relating, the notion of Thirdness ‘must be less seen as a PLACE than as a symbolic PROCESS of meaning-making that sees beyond the dualities of national languages (L1-L2) and national cultures (C1-C2)’ (Kramsch, Citation2011, p. 355), encompassing the symbolically broader aesthetic, historical and ideological dimensions of language teaching that have largely been left unexplored. From intercultural communicative competence in the Third Place to the refinement of meaning-making and sensible mentality as ‘symbolic competence’, Kramsch and Steffensen (Citation2008) further advocate going beyond the bounded analytical and critical mode of communication across culture and propose an ecological paradigm, arguing that although elements in the Third Place are not all mutually dependent, they are still symbiotic as part of the greater situational, cultural and societal environment maintaining an atmosphere of inclusivity, as at the holistic intersection of language education and cultural studies, both of which are collectively and interdependently scaffolded and are sensitive to what environment and context demand.

In addition to Third Space and Third Place, the notion of Third Culture (Useem, Citation1963) opposes the traditionally dyadic relations in cultural dimensions, arguing for transcendence of the two original cultures through the convergence of dialogical self and others, where dynamic communication is leveraged and mediated in intercultural interactions. The term Third Culture Kids (Pollock & Van Reken, Citation1999; Useem, Citation1993) describes those who face the cultural liminality of home culture and host culture and who sense the cultural incompatibility and predicament during intercultural communication. Casmir (Citation1999) advocates crossing the line into the third cultural area, designating third-culture building as a model to describe the dynamic growing awareness of intercultural sensitivity, and the interactive and open negotiation of meaning. To challenge monolithic cultural narratives and imposition, Holliday (Citation2018, Citation2022) advocates a ‘deCentred’ methodology to stand with the hybrid identity and open-ended multiplicity, making sense of how Thirdness is mediated in terms of intercultural connectedness and difference. His rhetoric positioning of cultural ‘deCentredness’ opens opportunities for self-reflexivity and being able to see possible challenging dichotomies and distributed creativity from a new stance.

The aforementioned metaphorical terms around Thirdness have been widely discussed and are often used almost interchangeably. The terms had yet to be compared in a meaningful way until MacDonald (Citation2019) employed comparative corpus-based analysis to examine how metaphors centred around Thirdness are used in terms of lexical collocation patterns and grammatical formation. According to MacDonald, these primary usages of metaphorical terms can be intricately accommodated and woven into the broader conceptualisation of the discourse of metaphors of Thirdness, offering a triadic and relational terrain for students to engage with others across difference, providing the possibility of challenging dichotomies from a new position and a therapeutic and symbolic setting to nurture a process-oriented disposition of cultural competence.

Linguacultural otherness

Culture is defined as a particular group’s characteristics and knowledge, encompassing language, religion, social habits, arts, etc. (Bennett, Citation2009). Language is one of the most important parts of culture and the carrier of culture (Gao, Citation2021); therefore, language education and culture teaching are inseparable. The term ‘linguaculture’ concerns the intersections of linguistics and culture, as learning a new language requires precise coding of culture signs. In such a context, language curricula and textbooks tend to focus on the cultural, historical and ethnic characteristics of the target language community (Han, Citation2021). Research reveals that students learn L2 better if texts include cultural details that make them more aware of how culture informs our capability to relate to each other (Arasaratnam-Smith, Citation2016).

Although integrating culture into language teaching is widely acknowledged, scholars have begun to question the positioning of ‘target culture centricity’, arguing that the assumption that target culture is to be acquired and imitated represents the unequal power relationship of ideological infiltration and that the imposed, passive consumption of Western culture without active negotiation will become a menace to cultural identity construction (Al-Issa, Citation2021; Banegas & Villacañas-de-Castro, Citation2016). Scholars advocate that how culture is approached should be critically evaluated and assessed (Granados-Beltrán, Citation2016). What is urgently needed is a shift from deficit modelling positing students as recipients of target cultural knowledge and vessels to be passively filled (Hu, Citation2005) to recognising students as active agents, multicultural and multilingual dialogue participants, co-constructing meaning and knowledge with a broader spectrum of perspectives relevant to multiple contexts. The lens of linguacultural ‘otherness’ aligns with such trends in language and culture education, facilitating students to think critically about issues of social justice and equity (Larsen & Searle, Citation2017). It reconstructs and re-presents text from the outsider’s perspective and examines the connection between the local and the global, focusing on the relationship between language and power in texts (Martin & Pirbhai-Illich, Citation2016). ‘Otherness’ also fosters students’ capacity to transform and create new narratives and structures, reinforcing conceptualisation in multiple ways with complex understandings of the connections between culture, language, race, identity, ethnicity and nationality (Litvinaite, Citation2022).

Prevailing studies on the issue of language and culture education suggest enhancing the awareness of linguistic diversity and multicultural dimensions with an inclusive pedagogical approach in the multilingual language classroom. Nevertheless, previous research has failed to demonstrate the exact pedagogical stages for how language teachers might purposefully and strategically enact a ‘critical’ otherness stance in the third terrain and how such a space challenges, expands, or reshapes students’ understanding of language and culture study, restructuring and transforming their previous understanding of multiculturalism. In addition, most research studies of culture are conducted in a K-12 context, and there is a paucity of studies about how such a community of critical dialogue about difference takes place in the Chinese tertiary-level English classroom. The two overarching research questions girding this study are: 1) How do teachers establish pedagogical stages and employ humanised pedagogy to decentre cultural imperialism and to promote plural values, behaviours and ways of knowing? 2) How do students relativise their own beliefs and behaviours to those of the target language culture, and how is dialogue about difference negotiated, reconstructed and embraced in the metaphorical domain of Thirdness?

Theoretical framework

Thirding-as-Othering

This study draws on the theoretical lens of Thirding-as-Othering. Influenced by the discourse of Thirdness in language and intercultural studies, this framework focuses on the triadic relating and aesthetic notion of Thirdness and Otherness, delineating the embedded hidden aspect of imagination and the unknown beyond traditional dualism. Thirding-as-Othering is delineated as the potential terrain to realise equal dialogue and communication and as an intermediate and symbolic zone of being and becoming. Instead of blindly instilling students with specific cultural knowledge, it tries to cultivate a desirable Thirdness perspective, to look for the intersection of language and culture in a critical and transformational multicultural lens, establishing a newer, richer, more complex cross-cultural compound identity. Thirding emphasises fluid sociality and diversity and brings the Other into the dualistic pairing of what is and is not (Fourie & Adendorff, Citation2015), and such a triadic relationship is no longer an either/or but is the potentiality of both/and, which permits and encourages that Thirding enact the creative combination of all-encompassing modes of thinking. What Thirding and Othering encompass is not just a hybrid or ‘in-between’ position but an all-inclusive continuum, a critical expanding journey challenging marginality and inequality. Within the co-created and shared-third terrain, cultural duality is challenged and belonging is advanced, critical dialogue takes place and creativity emerges. Thirding-as-Othering, which accentuates the critical spatial practices of cultural dialogue, exemplifies how power dynamics can oscillate between the dualistic powers and how subjectivity and objectivity, singularity and diversity can coexist in the lived space (Zhou & Dai, Citation2014).

Humanising pedagogy

Education is in desperate need of humanisation (Delport, Citation2016). This study draws on the theoretical framing of ‘humanising pedagogy,’ which emphasises the well-rounded development of a person’s body, mind and morality. The ultimate objective of higher education is to help students see the interrelationship of different modes of knowing and thinking and take initiative to critically analyse their potential to change the world (Petek & Bedir, Citation2018). Humanising pedagogy confronts deficit-driven practices that view culture, literacies and languages of diverse students as of secondary value. It purposefully combines the sociocultural resources into the classroom, encouraging the reflexive thought of opposites and the possibility of systemic change (Cervantes-Soon et al., Citation2017). The systematic humanistic philosophy of language education believes that students are active participants in the inclusive learning environment where their culture, life experiences and background knowledge are valued (Philip et al., Citation2019). Humanising pedagogy focuses on the embedded psychological and social dimensions of language education, promoting the design and enactment of a more inclusive linguistic structure where binary opposition can no longer find its place (Austin, Citation2022).

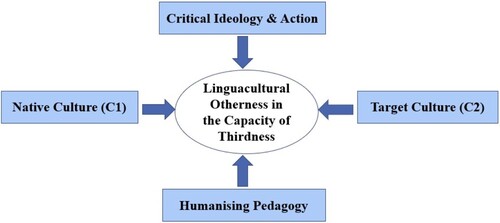

The synthesis structuring framework of Thirding-as-Othering combined with humanising pedagogy informs this study, for when people ‘Humanise the Other’, negative representations of binary opposition and stereotypes can be challenged, contradicted and rejected, leading towards a dialogical Thirdness as a source of learning. In addition, to solidify how language and culture can be Othered due to social cleavages and hierarchies embedded in power and privilege, teachers also need to foster ‘Critical Ideology and Action’ to encourage students to think and reflect critically in relation to diversity and power issues and, more importantly, cultivate the ability to translate such exploration into culturally enacted practices to reinterpret and reclaim the hybrid identity and explore potential possibilities for social change. The integrative theoretical framework undergirds the data analysis and encourages questions about how teachers employ humanising pedagogy critically by incorporating language and culture study into the creation of new inclusive narratives, identities and structure, and how students negotiate, reconstruct and re-present inequitable power relations and reshape the way they perceive the world. In sum, the theoretical constructs provide epistemological lenses to conduct an instrumental construct on the social and critical spatial interpretation of language and culture education ().

Methods

Research setting

Tertiary-level English language education in China has experienced great changes over the past decade, from purely emphasising target language acquisition and Western cultural absorption to the challenge of the dominance of English-only monolingual ideology and occidental cultural hegemony over traditional Chinese culture and ethnic moral quality. According to Wen (Citation2016), foreign language learning should not be accomplished at the cost of native cultural moral ethics education. With China’s burgeoning national power and growing international status, the current circumstance of English education in China advocates the strengthening of students’ linguacultural criticism consciousness. While acquiring foreign culture, equal adherence is positioned upon China’s stance and the capability to promote Chinese culture and narrate Chinese stories worldwide. Intercultural awareness requires understanding national and world conditions. The on-going ecological and sociolinguistic orientation to critical intercultural citizenship education in English education instigates a teaching paradigm shift: instead of letting certain cultures execute global hegemony, the new curriculum fosters a decolonial space to facilitate critical linguacultural knowledge construction to help students understand the symbolic power of native culture, cultivating students’ bilingual and intercultural awareness so that they may have a unique voice and critically engage in the dynamic and complex social interaction of global affairs.

Participants

The participants in this study are three Chinese tertiary-level English teachers and 90 ELLs at a public university in North China. Teachers Hong, Meimei and Yixin (pseudonyms) were born and raised in China, earned their bachelor’s degrees in English and master’s degrees in English education, and have an average of seven years of teaching experience. The students major in STEM-related subjects and are enrolled in the compulsory three-credit language course during the spring semester. The students, randomly selected from different sections of the course, are sophomores and Mandarin native speakers who learned English through classroom instruction for at least six years. The course met two days per week, 90 min each day for 12 weeks, and aimed to improve students’ overall listening, speaking, reading, writing and translation skills.

Data sources

A questionnaire survey, audio recordings of semi-structured interviews, classroom observations, and group discussions were the primary sources of the data-gathering instrument. The 30-item questionnaire (5-point Likert scale) distributed to students measured the following constructs: perception of native culture and target culture (six items); linguistic ideology (five items); how perception of culture influenced English study (six items); students’ perception of teachers’ language use and culture instruction (five items); and students’ bilingual and bicultural practices and understanding of power dynamics of language and culture (eight items). The Likert scale employed in this study helped to gauge participants’ focused opinions on teachers’ instruction, interpret and translate the students’ understanding of multilingualism, critical cultural power and positioning into meaningful quantifiable data, yielding holistic and tenable insights into the structural underpinning of linguistic and cultural equity. At the end of the questionnaire, there were four open-ended questions to capture the students’ reflections on class interactions and their own understandings of critical interculturality. Two semi-structured interviews with each teacher were conducted and audio-recorded (the first interview conducted at the beginning and the second at the end of the semester, approximately one hour for each). Interviews were conducted in Mandarin Chinese; narratives were transcribed and translated in English for the analysis. The first interview explored teachers’ backgrounds, previous practice, and philosophy in language teaching, and the second interview focused on planning and actual lesson instruction. In addition, by using the real-time instruction observation protocol (RIOT) combined with behaviour engagement related to instruction (BERI) to categorise the teachers’ pedagogical behaviour and students’ performance, video recordings of systematic and dynamic classroom observations were also collected throughout the spring semester with the researcher sitting at the back of the classroom. The teacher-student group discussions were also undertaken with three participant teachers and 15 volunteer students by the end of Week 9 in the English department conference room to engage the whole group in discussion about why the students thought and behaved the way they did in the classroom and other concerns and reflections on topics related to critical interculturality. Group discussion has its intrinsic advantage in helping uncover subtleties not covered in the questionnaire survey and interviews, offering a breadth of data and embedded contextual information. Additionally, textual documents like teachers’ syllabi and lesson plans and students’ feedback forms were collected to understand teachers’ language ideologies and how the teachers translate their beliefs into pedagogical practice. Student artifacts like work samples were collected to investigate how students make meaning and negotiate, mediate and construct multifaceted identities during language and culture study.

Data analysis

Inductive grounded theory analysis was adopted in analysing all collected data. Heuristics content analysis focusing on the evaluation of correlations and synthesis of thinking and performance in the shifting landscape guided the data analysis (Strauss & Feiz, Citation2014). Audio-recorded files of interviews, classroom observation and group discussion were imported into Dedoose software. Data were analysed following the cyclic coding technique (Miles et al., Citation2014) and the coding procedures of qualitative thematic analysis (Guest et al., Citation2012). Three coding cycles were followed: first, open coding, in which each file was independently coded for generic categories and patterns; second, theoretical and analytical frameworks were employed to identify emergent themes; third, connections were examined between themes, clustering themes and superordinate themes, compiling directories of participants’ discourses and generating a master list of themes for all cases. During the third cycle, the researcher also focused on verbatim dialogues, non-verbal interactions, and structural and environmental conditions. Two independent raters, colleagues of the researcher, were given a random sample of the data, discussed coding disagreements with the researcher to check if coding needed to be redefined or reformulated, and came to a consensus. Reciprocal member checking was employed throughout the analysis; after the participant constructed the narrative, the researcher analysed it and sent it back to the participant in the post-interview so that the participant might reflect and make meaning-focused revisions to resolve discrepancies. All narratively coded field texts were maximally triangulated to avoid subjectivity, ensuring the rich description, trustworthiness, persuasiveness and plausibility of the entire data instrument.

Findings

Affordances and humanisation in the triadic capacity of Thirdness

‘As the ideological orientation of English education has shifted, I am always thinking about how students can actively engage in my language classroom and how to evoke proactivity and reciprocity of critical dialogue exchange’, teacher Hong said in her interview. To develop students’ critical intercultural competence, all three participant teachers included the ‘five pedagogical stages’ in their teaching plans. The ‘five pedagogical stages’ were originally brought up by teacher Hong and shared in the monthly faculty lesson preparation group meetings. Teachers Meimei and Yixin were staunch supporters of these stages and included them in their own teaching plans. These pedagogical stages were originally in Chinese and are translated into English in below.

Throughout the five stages, the teachers treat the dynamic and multifaceted exploration of culture as an open, fluid, ongoing meaning-making process. According to the participant teachers, to cultivate students’ critical intercultural competence, the first step is to let students be familiar with both cultures with related cultural immersion activities, and such cultural omnivorousness in multiethnic societies will inevitably bring up certain dissonance, tensions, or conflict, which is shown in stage 2. Then, during stage 3, conflicting cultural norms result in the nonacceptance or resistance of students, who argue or counterattack from their own standpoints. In stage 4, with teachers’ guidance to reflect on cultural connotations and connections, students rethink the gap between cultural values, with dialogue deepening during the reflective process. In stage 5, students cultivate integrative cross-cultural competence, with the possibility of advocating for symbolic actions to embrace cross-cultural sustainability. Excerpt 1 collected from the classroom observation shows how teacher Hong implemented these pedagogical stages during instruction:

Excerpt 1 (collected from classroom observation regarding an English film discussion)

OK, now we’ve watched the film Gua Sha, how do you feel about this film in general?

I like the film, a very moving story about the parents’ love for their child.

What else? Do you sense any culturally related issue or theme in this film?

Oh yes, before watching this film, I knew there is difference between Eastern and Western culture, but what surprises me is the deep misunderstanding of culture; for example, the traditional Chinese scraping therapy of Gua Sha is beneficial to our health. But the foreigners know nothing about our traditional Chinese medicine.

他们有点无知 (They are kind of ignorant.)

What do you think of Da Tong, the father’s action in this movie? If you were the kid’s father, would you do the same?

I would do the same to fight back, as I feel discriminated against. As you can see, the whole family was hurt.

Just fighting back is no use, I think we need to explain to Westerners what Gua Sha really means in our culture, and how it is good for our health. As people in the West never experience such therapy, they have no idea what it is all about. We can even invite them to try Gua Sha therapy in person when they are sick, hahahaha, then they will know the therapeutic effect.

I am glad to hear your discussion about the cultural difference, but how is such conflict ultimately solved, and if you jump out of the box, do you see any common ground between the two cultures as well?

We need to let people from other cultures be aware that traditional Chinese scraping Gua Sha is not abuse but an effective treatment. The common ground this film represents is the legal protection and emotional love for children.

The classroom interaction and discussion with in-depth culture enquiry promoted the students’ intercultural competence and reduced the stereotypical misrepresentation of any particular moral norms. Below are students’ understanding of culture from the questionnaire survey:

Excerpt 2 (collected from students’ questionnaire survey open-ended questions)

Table

Notes:

‘We need to see culture in an objective way; different cultures blend with each other and we need to learn from each other. We should respect each culture, not blindly deny nor follow any culture. We need to stand higher and see culture in a critical way. Each culture is valuable, therefore need to see culture in a bird view, see from a higher space critically.’

‘The character on the left represents native culture. The character on the right represents Western culture. The character in the middle represents multiculturalism inclusion and their mutual learning. All three characters hold hand in hand.’

Critical language awareness of Otherness

Early theorising in applied linguistics suggested that language learners were linguistic ‘vessels’ (Hu, Citation2005) passively being filled with linguistic points instead of bearing any nascent relational social-emotional development. When asked to discuss the objective for language instruction at a tertiary level, teachers still tend to mention bilingualism, biliteracy development and cross-cultural competence, but are not motivated to seek the fourth goal, ‘critical language awareness’ (Metz, Citation2021). Teachers in this study intentionally brought the fourth element of ‘criticality’ framing into instruction. Below is an excerpt from a classroom observation:

Excerpt 3 (collected from classroom observation regarding a text discussion)

Now let’s discuss the central theme of this text. Anyone want to share something?

The theme is online shopping fever, how consumption changed along the way.

Can anybody name any detailed examples of the online shopping illustrated within?

The author talked about America’s consumer intention on two major shopping days, Black Friday and Cyber Monday, and the author narrated how people wait online for the substantially discounted product on the Monday after Thanksgiving.

Who is in this text, and who do you think is missing?

The title of this text is Global Online Shopping. The author discusses a Western country’s shopping manners; do you think any voices are missing? If you were the author, how would you like to write?

I may add how people from the East, like people from China, Korea and Japan do their shopping online. Take China, for example. Foreigners may not be familiar with our Double-11 Online Shopping Festival, and how the Nov 11 E-commerce Shopping Carnival can involve the largest number of Chinese consumers, and our own online shopping culture, things like that.

Very good point.

Excerpt 4 (collected from a student in the questionnaire open-ended question section, originally in Chinese, translated into English):

I am shocked to find that English texts and mechanisms behind the curriculum are probably not serving me. Initially, my thought was that language learning is pure language learning. I already paid for the English textbook; how can the book possibly not serve me? With this class, I started to think about how what I read in class can favour a certain dominant culture. For instance, textbook narrations about online shopping behaviour from people in the West or other images of American food (hamburger, pizza, donuts), are they representative for all? To have equal dialogue, voices from other countries need to be included as well.

The Pearson correlation coefficient is used to represent the strength of each component listed in the survey items. From , it is seen that the correlation coefficient between LTS, C1&C2, IN and BBC are 0.466, 0.536, and 0.513, respectively, demonstrating a significant positive correlation between these components at the 0.01 level. The correlation coefficient values between CDR, C1&C2, IN and BBC are 0.425, 0.459, and 0.534, demonstrating a significant positive correlation between each component at the 0.01 level.

Table 1. Pearson correlation analysis of critical interculturality.

below is the mediate effect model analysis to see how ‘cultural dialectical reflection’ plays a mediator role in Thirdness construction.

Table 2. Mediation effect model analysis of cultural dialectical reflection.

As illustrates, the independent variables are C1&C2, IN and BBC, the dependent variable is LTS, with CDR serving as a mediator. From the mediation effect analysis, it is shown that (1) Using C1&C2, IN, BBC as independent variables and LTS as dependent variable for linear regression analysis, the R-squared value of the model is 0.440, indicating that C1&C2, IN, BBC can explain the 44.0% change in LTS. The regression coefficient values for C1&C2 are 0.210 (t = 2.707, p < 0.01), IN is 0.350 (t = 3.432, p < 0.01) and BBC is 0.350 (t = 3.399, p < 0.01), indicating that C1&C2, IN, BBC all have a significant positive impact on LTS. (2) Taking C1&C2, IN, BBC as independent variables and CDR as dependent variable for linear regression analysis, the R-squared value of the model is 0.394, indicating that C1&C2, IN, BBC can explain 39.4% of the change in CDR. The regression coefficient value for C1&C2 is 0.155 (t = 2.329, p < 0.05), the regression coefficient value for IN is 0.203 (t = 2.317, p < 0.05) and the regression coefficient value for BBC is 0.353 (t = 3.996, p < 0.01), indicating that C1&C2, IN, BBC all have a significant positive impact on CDR. (3) Using C1&C2, IN, BBC, CDR as independent variables and LTS as dependent variable for linear regression analysis, the R-squared value of the model is 0.469, indicating that C1&C2, IN, BBC, CDR can explain the 46.9% change in LTS. The regression coefficient values for C1&C2 are 0.169 (t = 2.154, p < 0.05), IN is 0.296 (t = 2.876, p < 0.01), BBC is 0.256 (t = 2.331, p < 0.05) and CDR is 0.266 (t = 2.165, p < 0.05), indicating that C1&C2, IN, BBC, CDR all have a significant positive impact on LTS. Therefore, CDR generated a statistically partial mediation effect in the model contributing to the positioning of linguaculturality in the third space.

Language, a powerful tool for communication, can be used for both inclusivity and discrimination. Including critical language awareness scaffolding as a means of deepening dialogue in the classroom resonates with Bourdieu’s (Citation1982) notion of the power dynamics of language as a form of symbolic power, and a statement of how the necessary Thirdness can serve as an actual and symbolic function facilitating interactive representation and self-transcendence, which should be inherently nested in language education (Kramsch, Citation2011; Zhu & Kramsch, Citation2016). Throughout the teachers’ pedagogical scaffolding framed by critical linguistic pedagogy, the students started to become critical consumers of information and producers of knowledge through collaboration and dialogue of mutual understanding. Students are considered active agents of their own learning; by raising different levels of critical cultural awareness during language study, students no longer purely construct linguistic pedagogical knowledge per se (Roux & Becker, Citation2016) but simultaneously experience mindset expansion to interrogate their language ideologies from a cross-cultural perspective, forming a pluralistic view of English study from a critical stance.

Cultural equity and compound cultural identity

Under the broader socio-cultural milieu, bringing attention to cultural equity in language study tends to focus on the learners’ identity construction, cultural value orientations, power negotiations and cultural positioning. Students’ identities can be mediated as they voyage through ‘new spaces of learning and sharing knowledge, critique and reflecting on new or unfamiliar conceptions’ (Daniels & Brooker, Citation2014, p. 69). With dynamic and fluid identity construction during the process of becoming, a new sense of self is shaped, and such a newly shaped identity position will inform learning agency, autonomy and motivation to learn in diverse educational and social contexts (van Lier, Citation2008).

For English learners in China, who are categorised as a less diverse cohort group of students, to take the initiative to agentively engage in constructing hybrid identity, the capacity of Thirdness plays a critical role in producing hybrid texts, hybrid self, and semiotic creative meanings beyond the restrictive cultural parameters. The learning spaces created and the pedagogical stages employed by teachers are of overriding importance. One unit of the observed class centred around Chinese-English translation skills. The teacher chose curriculum material involving cultural difference or ‘culturally loaded’ words to bring forth students’ reflexivity associated with multiple identity positioning and a robust agency exercise to either take up or resist a certain position. The following excerpt demonstrates how the teacher strategically facilitated such a process:

Excerpt 5 (collected from classroom observation of a Chinese-English cultural translation exercise)

Here comes a phrase translation practice. I want you to think for a second: How do you translate ‘亚洲四小龙’?

The four rising dragons from Asia.

OK, good try. Do you know how ‘dragon’ can be interpreted differently in the East and West?

The dragon in China symbolises strength and power, something good, as we Chinese are called the ‘heir of the dragon’, but in the West, dragon refers to a huge monster that spits fire from its mouth, something bad.

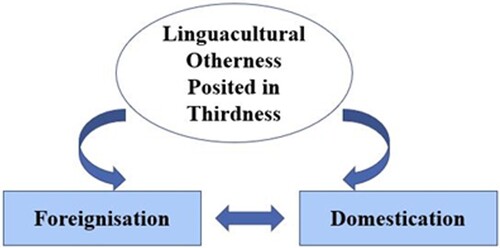

Thank you. Here, let me introduce the translation technique of ‘domestication’, which means minimising the strangeness of the foreign text for target language readers, versus ‘foreignisation’, maintaining the foreignness of the original text. So here comes the dilemma: Which English word should we use for this translation?

I think we need replace ‘dragon’ with a word that means something good in Western people’s eyes, like ‘tiger’, as the tiger is vigorous, powerful and full of hope, perfectly suiting the context for this translation.

Good point, now people from Western culture can understand it better, terrific!

I do not quite agree. I understand that for Westerners to fully understand, we will use ‘tiger’ instead of ‘dragon,’ but if we always use the ‘domestication’ strategy during translation, it obliterates our national characteristics of the original text, and Western readers will never understand the unique status and connotation of Oriental ‘dragon’.

Wow, very good argument. Now that you can see there are no exactly right or wrong answers, our discussion can be open to all possible interpretations.

Class interaction showed that students developed an understanding of the cultural symbolism representation difference, and then, with the teacher’s thought-provoking, evaluative and amplifying questions, the students realised how the meaning of a certain term is socially constructed with cross-cultural dissonance. In stage 3, heated discussions brought forth tensions and resistance associated with how translation approaches can possibly lean towards the source culture or the target culture. During the process of ‘becoming’ critical thinkers, the students pondered the issue of cultural belonging, exercised their third analytic agency, and were brought into the liminal and hybrid terrain that allows for shared meaning-making with those whose lives otherwise seldom intersect. The students shared their own cultural positioning in terms of how ‘domestication’ and ‘foreignisation’ can be employed in translation practice. Such active (re)negotiation and (re)construction of cultural and linguistic phenomena also gave rise to the triadic agency as language learners, in terms of how they could take initiative and a critical perspective to learn, respond and (re)interpret self-other relationships. Through constant and systematic identity construction and cultural ideology negotiation, the capacity for symbolic Thirdness agency is mediated, stimulated and consolidated. When students intersect with cultural issues, they are empowered to progressively navigate, negotiate and reconstruct the compound cultural identity, which is not fixed or intrinsic, in relation to context. As a result of the reflexive process in terms of cultural value orientation, students started to build a sense of commitment to confront incoherence and inconsistence, becoming active and critical enactors of knowledge with a holistic and integrative understanding of richer cultural values, understanding the ethics of cultural difference, hegemony, ethnocentrism, etc. The teachers’ instruction played an indispensable and valuable role in advocating cultural equity and shaping students’ compound cultural identities. Mediated by a dynamic structural context and trajectory, the pedagogical stages offer a favourable milieu to facilitate navigating cultural identity (re-)positioning and (re-)construction ().

Conclusion and implications

Taking on the framework of Thirding-as-Othering and humanised pedagogy, the purpose of this study was to explore how teachers guided students to decentre cultural imperialism by promoting a more plural linguistic and cultural landscape with specific humanised pedagogical stages established in a transformational Thirdness, and how students critically relativised their cultural beliefs to those of the target language, finding linguacultural Otherness with a richer compound cultural identity. The study reveals that in the conceptualised inclusive interpretation, students rethink and reframe heterogeneity in all linguistic and cultural practices and cultivate the semiotic power of the critical self in the interpretive and objective judgmental perception of pluralism and multiculturalism that pertains to the essence of Thirdness. The finding echoes the notion of the important ‘critical and transformational aspects of the original conceptualisation of thirdness’ (MacDonald, Citation2019, p. 107). The bundling of target culture alongside language instruction should be abandoned as an imperialist relic, as culture is represented in the complexity of Thirdness, and interpretive opportunities should be deliberately brought up to showcase such ambiguity and plurality. Under the cultural equity-oriented teaching paradigm, contradictions and absurdities in Thirdness can be viewed as the driving force to bridge barriers to equity in language and cultural learning and education. This study highlights the critical and humanistic aspect of language teaching and learning that can meaningfully be seen as cultural niche construction, providing students with ample opportunities to leverage their fluid dialogic linguacultural practices and meaning negotiation. The pedagogical stages employed by teachers facilitate inclusive narratives that move beyond national circumscription and confinement to explore more accessible, equitable, reflective and sustainable cultural matrices and paradigms.

The implication of this study lies in that it reconceptualises tertiary-level foreign language education, which often focuses on communicative competence, to the negotiation of language ideology, language boundaries, symbolic cultural power, equity and inclusion. These discussions create an in-between agentive Thirdness terrain and transfer students’ interaction with the dyad towards sustainable linguistic and intercultural practices in the aesthetics of Thirdness, suggesting how malleable language ideology can be in the face of imperialism and how humanised pedagogy can be conducive to students’ hybrid identity construction overriding the old. The humanised pedagogy in the epistemological Thirdness breaks down the unidimensional landscape of language education and facilitates language learning through cultivating critical linguacultural otherness towards a culturally and socially sensitive language pedagogy, birthing a critically new consciousness transcending the traditional dualist space of rigid, closed binary opposition to dynamic cultural innovation with flexibility, fluidity and hybridity. The inherent capacity of Thirdness is not abolishing dichotomies, nor is it an idealistic attempt to gloss over difference. Instead, within this transformative space, ambivalence, marginality and criticality can co-exist as cultural symbiosis. The compound and multiple identity enactments reconstructed within each student affects how they conceive, perceive and achieve beyond the language classroom, builds their capacity to make transformational change, and prepares them as interculturally competent and responsible individuals in society. This study will inform pre-service and in-service teachers’ pedagogical practices to not only support students’ tolerance and accommodation of difference but to see how additional Thirdness in the interstice among differences can become the encompassing territory they all share and embrace.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fang Gao

Fang Gao is Associate Professor in the English Department at Shenyang Pharmaceutical University. She has taught multilingual learners in the United States and China in schools and community spaces. Her academic research and professional work focus on translanguaging practices and bilingual and biliteracy education with multiple projects relating to undergraduate, graduate/professional, and staff and faculty-facing initiatives. Her academic publications include articles in the Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, Journal of Language, Identity and Education, and Educational Leadership.

References

- Al-Issa, A. (2021). Using English language teaching professionalism to bash cultural imperialism in the Sultanate of Oman: A response to Wyatt and Sargeant. Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education, 28(3), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2021.1904381

- Anderson, J. (2019). In search of reflection-in-action: An exploratory study of the interactive reflection of four experienced teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102879

- Arasaratnam-Smith, L. A. (2016). An exploration of the relationship between intercultural communication competence and bilingualism. Communication Research Reports, 33(3), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2016.1186628

- Aronin, L., & Singleton, D. (2012). Affordances theory in multilingualism studies. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 2(3), 311–331. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.3.3

- Austin, T. (2022). Linguistic imperialism: Countering anti Black racism in world language teacher preparation. Journal for Multicultural Education, 16(3), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-12-2021-0234

- Badwan, K., & Simpson, J. (2019). Ecological orientations to sociolinguistic scale: Insights from study abroad experiences. Applied Linguistics Review, 13(2), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2018-0113

- Banegas, D. L., & Villacañas-de-Castro, L. S. (2016). Criticality. ELT Journal, 70(4), 455–457. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccw048

- Bennett, J. M. (2009). Cultivating intercultural competence: A process perspective. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 121–140). Sage.

- Bensalah, H., & Gueroudj, N. (2020). The effect of cultural schemata on EFL learners’ reading comprehension ability. Arab World English Journal, 11(2), 383–394. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol11no2.26

- Bhabha, H. K. (1988). The commitment to theory. New Formations, 5, 1–23.

- Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1982). Language and symbolic power. Harvard University Press.

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2013). Introduction. In A. S. Canagarajah (Ed.), Literacy as translingual practice: Between communities and classrooms (pp. 1–10). Routledge.

- Casmir, F. L. (1999). Foundations for the study of intercultural communication based on a third-culture building model. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23(1), 91–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(98)00027-3

- Cervantes-Soon, C., Dorner, L., Palmer, D., Heiman, D., Schwerdtfeger, R., & Choi, J. (2017). Combating inequalities in two-way language immersion programs: Toward critical consciousness in bilingual education spaces. Review of Research in Education, 41(1), 403–427. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X17690120

- Cho, H. (2016). Crafting a third space: Integrative strategies for implementing critical citizenship education in a standards-based classroom. University of Washington.

- Chun, E., & Evans, A. (2016). Rethinking cultural competence in higher education: An ecological framework for student development. ASHE Higher Education Report, 42(4), 7–162. https://doi.org/10.1002/aehe.20102

- Constantinidis, D. (2016). Crowdsourcing culture: Challenges to change. In K. Borowiecki, N. Forbes & A. Fresa (Eds.), Cultural heritage in a changing world (pp. 215–234). Springer International Publishing.

- Daniels, J., & Brooker, J. (2014). Student identity development in higher education: Implications for graduate attributes and work-readiness. Educational Research, 56(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2013.874157

- Delport, A. (2016). Humanising pedagogies for social change. Educational Research for Social Change, 5(1), 6–9.

- Dirlik, A. (1997). The postcolonial aura: Third world criticism in the age of globalization. Westview Press.

- Fourie, R., & Adendorff, M. (2015). An analysis of the bodily spatial power relations in Agaat by Marlene van Niekerk. Tydskrif Vir Letterkunde, 52(2), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.4314/tvl.v52i2.1

- Gao, F. (2021). Negotiation of native linguistic ideology and cultural identities in English learning: A cultural schema perspective. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 42(6), 551–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1857389

- Granados-Beltrán, C. (2016). Critical interculturality. A path for pre-service ELT teachers. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 21(2), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v21n02a04

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Sage.

- Han, L. M. (2021). Research on Chinese cultural aphasia in English learning. Journal of Higher Education, 12, 52–55.

- Holliday, A. (2017). PhD students, interculturality, reflexivity, community and internationalisation. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(3), 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2015.1134554

- Holliday, A. (2018). Understanding intercultural communication: Negotiating a grammar of culture (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Holliday, A. (2022). Searching for a third-space methodology to contest essentialist large-culture blocks. Language and Intercultural Communication, 22(3), 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2022.2036180

- Hu, W. Z. (2005). The empirical study of intercultural communication. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 37(5), 323–327.

- Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford University Press.

- Kramsch, C. (1999). Thirdness: The intercultural stance. In T. Vestergaard (Ed.), Language, culture and identity (pp. 41–58). Aalborg University Press.

- Kramsch, C. (2006). From communicative competence to symbolic competence. The Modern Language Journal, 90(2), 249–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00395_3.x

- Kramsch, C. (2011). The symbolic dimensions of the intercultural. Language Teaching, 44(3), 354–367. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444810000431

- Kramsch, C., & Steffensen, S. V. (2008). Ecological perspectives on second language acquisition and socialization. In P. A. Duff & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education: Language socialization (pp. 17–28). Springer-Verlag.

- Kramsch, C., & Whiteside, A. (2008). Language ecology in multilingual settings. Towards a theory of symbolic competence. Applied Linguistics, 29(4), 645–671. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amn022

- Larsen, M. A., & Searle, M. J. (2017). International service learning and critical global citizenship: A cross-case study of a Canadian teacher education alternative practicum. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.011

- Litvinaite, J. (2022). Between resistance and collaboration: A teacher’s professional activity in the third space. Journal of Education Culture and Society, 13(1), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.15503/jecs2022.1.157.171

- MacDonald, M. N. (2019). The discourse of ‘Thirdness’ in intercultural studies. Language and Intercultural Communication, 19(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2019.1544788

- Martin, F., & Pirbhai-Illich, F. (2016). Towards decolonising teacher education: Criticality, relationality and intercultural understanding. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 37(4), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2016.1190697

- Metz, M. (2021). Pedagogical content knowledge for teaching critical language awareness: The importance of valuing student knowledge. Urban Education, 56(9), 1456–1484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918756714

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Mizutani, S. (2013). Hybridity and history: A critical reflection on Homi K. Bhabha’s post-historical thoughts. Ab Imperio, 2013(4), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2013.0115

- Moore-Gilbert, B. (1997). Postcolonial theory: Context, practices, politics. Verso.

- Núñez-Pardo, A. (2018). The English textbook. Tensions from an intercultural perspective. GIST Education and Learning Research Journal, 17(17), 230–259. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.402

- Oldenburg, R. (1989). The great good place: Cafés, coffee shops, community centres, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts, and how they get you through the day. Paragon House.

- Ou, W. A., & Gu, M. M. (2020). Negotiating language use and norms in intercultural communication: Multilingual university students’ scaling practices in translocal space. Linguistics and Education, 57, 100818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2020.100818

- Patrão, A. (2018). Linguistic relativism in the age of global lingua franca: Reconciling cultural and linguistic diversity with globalization. Lingua. International Review of General Linguistics. Revue internationale De Linguistique Generale, 210, 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2018.04.006

- Petek, E., & Bedir, H. (2018). An adaptable teacher education framework for critical thinking in language teaching. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 28, 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.02.008

- Philip, T. M., Souto-Manning, M., Anderson, L., Horn, I., Carter Andrews, D. J., Stillman, J., & Varghese, M. (2019). Making justice peripheral by constructing practice as “core”: How the increasing prominence of core practices challenges teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487118798324

- Piller, I. (2017). Intercultural communication: A critical introduction. Edinburgh University Press.

- Pollock, D., & Van Reken, R. (1999). The third culture kid experience. Intercultural Press.

- Roux, C., & Becker, A. (2016). Humanising higher education in South Africa through dialogue as praxis. Educational Research for Social Change, 5(1), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i1a8

- Strauss, S., & Feiz, P. (2014). Discourse analysis: Putting our worlds into words. Routledge.

- Tubino, F. (2004). Del interculturalismo funcional al interculturalismo crítico. In M. Samaniego & C. G. Garbarini (Eds.), Rostros y fronteras de la identidad (pp. 151–164). Universidad Católica de Temuco.

- Useem, J. (1963). The community of man: A study in the third culture. The Centennial Review, 7(4), 481–498.

- Useem, R. H. (1993). Third culture kids: Focus of major study. http://www.tckworld.com/useem/art1.html.

- van Lier, L. (2008). Agency in the classroom. In J. P. Lantolf & M. E. Poehner (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages (pp. 163–186). Equinox.

- Walsh, C. (2009). Interculturalidade crítica e pedagogia decolonial: In-surgir, re-existir e re-viver. In V. Candau (Ed.), Educação intercultural na América Latina: Entre concepções, tensões e propostas (pp. 12–42). 7 Letras.

- Walsh, C. (2018). Interculturality and decoloniality. In W. D. Mignolo & C. E. Walsh (Eds.), On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis (pp. 57–80). Duke University Press.

- Wen, Q. F. (2016). Teaching culture(s) in English as a lingua franca in Asia: Dilemma and solution. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 5(1), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1515/jelf-2016-0008

- Ye, H., & Wang, K. F. (2016). Exploration of the ‘third space theory’ cross-cultural communication. The Seeker, 5, 42–46.

- Yu, K. H. (2018). Implications of the affordance theory for second language acquisition. Foreign Language Teaching, 3, 34–42.

- Zhou, S. Y., & Dai, J. C. (2014). Logic analysis of concept and theory of cultural geography: Process in cultural geography in China’s Mainland during the past decade. Acta Geographica Sinica, 69(10), 1521–1532. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb201410011

- Zhou, V. X., & Pilcher, N. (2019). Tapping the Thirdness in the intercultural space of dialogue. Language and Intercultural Communication, 19(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2018.1545025

- Zhu, H., & Kramsch, C. (2016). Symbolic power and conversational inequality in intercultural communication: An Introduction. Applied Linguistics Review, 7(4), 375–383. doi:10.1515/applirev-2016-0016