ABSTRACT

Introduction

Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor alpha, and GP1111 (Zessly®, Sandoz) is the most recently approved infliximab biosimilar in Europe. We reviewed the approval process and key evidence for GP1111, focusing primarily on the indications of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Areas covered

This narrative review discusses preclinical, clinical, and real-world data for GP1111.

Expert opinion

Results from the Phase III REFLECTIONS trial in patients with moderate-to-severe active RA despite methotrexate therapy confirmed the similarity in efficacy and safety between GP1111 and reference infliximab. Switching from reference infliximab to GP1111 in REFLECTIONS had no impact on efficacy or safety. Since the European approval of GP1111 in March 2018, real-world data have also confirmed the efficacy and safety of switching from another infliximab biosimilar to GP1111 in patients with RA and IBD. In addition, budget impact analysis of various sequential targeted treatments in patients with RA found that GP1111 was cost-effective when used early after failure of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Therefore, 5 years’ post-approval experience with GP1111 in RA and IBD, and key clinical and real-world evidence, support the safety and efficacy of continued use of GP1111 in all infliximab-approved indications.

1. Introduction

Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody with high affinity for membrane-bound and soluble tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [Citation1,Citation2]. Since its introduction in 1998, this biologic medicine has been widely used in the treatment of immune-related inflammatory diseases [Citation3,Citation4], and is approved for use in the following indications: rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and plaque psoriasis [Citation1,Citation2]. Wide-ranging evidence from randomized controlled trials, registries, and post-marketing surveillance studies in these populations has shown that infliximab is effective and offers an acceptable safety profile [Citation5–7].

Guideline recommendations in the EU and the US regarding the use of infliximab across all approved indications are shown in . For example, the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommends biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs, including infliximab) for patients with RA who are not reaching treatment targets with methotrexate (MTX) and have poor prognostic factors such as high swollen joint count, presence of early erosions, or failure of two or more conventional synthetic DMARDs [Citation8]. The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) recommends that adults with moderate-to-severe CD and inadequate induction responses to conventional therapy can receive infliximab combined with a thiopurine, and also recommends infliximab for the induction and maintenance of remission in adults with difficult-to-treat complex perianal fistulizing CD [Citation10]. In adults with moderate-to-severe UC, ECCO also recommends anti-TNF therapy (e.g. infliximab) for inducing remission in those who have an inadequate response or intolerance to conventional therapy, as well as maintaining remission in those who respond to induction therapy with the same medicine [Citation15].

Table 1. Guideline recommendations for the use of infliximab across the approved indications.

Biosimilars are biologic medicines that correspond to a reference medicine in terms of physicochemical, biological, immunological, efficacy, and safety properties. Although biosimilars are not identical copies of the reference medicine, biosimilars must have an identical amino acid sequence and show indistinguishable post-translational modifications and higher-order protein structure. Regulatory evaluation of biosimilars is therefore based on demonstrating structural and functional similarity to a reference biologic. The absence of clinically significant differences between the biosimilar and reference biologic is then confirmed by clinical pharmacokinetics (PK), effectiveness, and safety investigations. The use of biosimilars can reduce costs, contribute to budget sustainability in healthcare, and expand patient access to treatment [Citation25]. Four biosimilars of reference infliximab (Remicade®) have been approved in the EU: Inflectra® and Remsima® in 2013, Flixabi® in 2016, and Zessly® (GP1111) in 2018 [Citation26].

Here, we review the approval process and key clinical evidence for the infliximab biosimilar GP1111. We also summarize the available real-world evidence for GP1111, focusing primarily on data in the indications of RA and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), given the paucity of data in the other approved indications. With the increasing relevance of switching between biosimilars in daily practice, we review the evidence for switching from other infliximab biosimilars to GP1111. In addition, we provide an overview of recent administration and cost-effectiveness data for GP1111.

2. Development and approval of GP1111 (biosimilar infliximab)

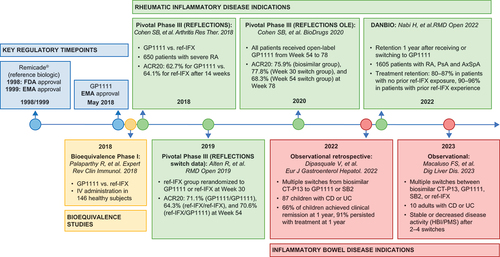

GP1111 was approved by the European Medicines Agency in May 2018 () [Citation27,Citation29]. Regulatory approval of biosimilars is granted by the European Medicines Agency and US Food and Drug Administration based on an extensive comparison that establishes similarity in quality characteristics, structure, biological activity, clinical safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity to those of the licensed reference biologic medicine. A robust, consistent manufacturing process is also required [Citation30].

Table 2. Approved indications for infliximab medicines, including biosimilars, in Europe and the USA.

Approval of GP1111 considered the totality of evidence, that is, the whole body of analytical, preclinical, and clinical evidence, which demonstrated that GP1111 matched reference infliximab in terms quality characteristics, structure, biological activity, PK, pharmacodynamics, clinical safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity, supporting its use in all relevant indications [Citation3,Citation31]. GP1111 has similar physicochemical characteristics to reference infliximab with regard to primary, secondary, and tertiary structures, with tertiary structures being assessed through the use of crystallography and analytical ultracentrifugation studies [Citation32,Citation33]. PK similarity of GP1111 to reference infliximab has been demonstrated in healthy volunteers and in patients with moderate-to-severe RA despite MTX therapy [Citation34,Citation35]. The key studies for GP1111, including clinical and post-approval studies, are summarized in . Pharmacodynamic similarity of GP1111 to reference infliximab has been shown with respect to Fab-related and Fc-related properties (e.g. binding to soluble TNF-α and response inhibition, TNF-α binding kinetics, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, and complement-dependent cytotoxicity activity) [Citation33,Citation36]. A pivotal Phase III, multinational, randomized, double-blind, double-arm, parallel-group study in patients with moderate-to-severe RA despite MTX therapy (REFLECTIONS B537-02) established the similarity of GP1111 to reference infliximab in terms of safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity [Citation37]. Based on the totality of evidence establishing the biosimilarity of GP1111 to reference infliximab, GP1111 was approved for all indications in which the reference medicine was approved ().

Figure 1. Timeline highlighting key studies for GP1111. ACR20: American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement criteria; AxSpA: axial spondyloarthritis; CD: Crohn’s disease; EMA: European Medicines Agency; FDA: US Food and Drug Administration; HBI: Harvey–Bradshaw Index; IV: intravenous; OLE: open-label extension; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; PMS: Partial Mayo Score; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; ref-IFX: reference infliximab; UC, ulcerative colitis.

3. GP1111 in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases

3.1. Clinical trial data for GP1111 in RA

REFLECTIONS was a Phase III, double-blind, parallel-group, confirmatory study that assessed intravenous (IV) GP1111 or reference infliximab administered in combination with MTX in 650 patients with moderate-to-severe active RA despite MTX therapy [Citation37]. At the start of the 78-week study, patients were randomized 1:1 to either GP1111 or reference infliximab. At Week 30, patients receiving reference infliximab were re-randomized to GP1111 or reference infliximab, then at Week 54, the remaining patients receiving reference infliximab were switched to GP1111 until the end of the study. The study design is summarized in . In REFLECTIONS, American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement criteria (ACR20) response rates after 14 weeks of treatment, the primary endpoint, were 62.7% for GP1111 and 64.1% for reference infliximab; both results were within the range reported in historical registration trials for reference infliximab (50–76%) [Citation37]. In addition, ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 response rates were similar between the two groups at all time points through Week 30 [Citation37]. Subgroup analyses at Week 14 showed that ACR20 response rates and changes in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, with four components based on hs-CRP (DAS28-CRP), were similar between GP1111 and reference infliximab in patient cohorts stratified by age, sex, race, region, treatment history, and immunogenicity status [Citation38]. Results to Week 30 continued to show similar efficacy of GP1111 and reference infliximab across all subgroups [Citation38]. The safety profiles of GP1111 and reference infliximab were comparable, with no clinically meaningful differences observed between treatment arms [Citation37,Citation39,Citation40]. In REFLECTIONS, the incidence of treatment-related adverse events (AEs) over 30 weeks of treatment was 25.1% versus 23.0% for GP1111 versus reference infliximab [Citation37]. There were no notable differences in the incidence and characteristics of treatment-emergent AEs of special interest (infusion-related reactions, hypersensitivity, infections [including tuberculosis and pneumonia], and malignancy [including lymphoma]) between the GP1111 and reference infliximab groups [Citation37]. Over the initial 30-week treatment period, the incidence of antidrug antibody (ADA) development was 48.6% versus 51.2% for GP1111 versus reference infliximab [Citation37]; of the ADA-positive patients, 79.0% and 85.6% tested positive for neutralizing antibodies against GP1111 and reference infliximab, respectively.

Figure 2. Timeline highlighting key studies for GP1111. Adapted from Cohen SB, et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:155 [Citation37]. Image adapted under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.Org/licenses/by/4.0/).

![Figure 2. Timeline highlighting key studies for GP1111. Adapted from Cohen SB, et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:155 [Citation37]. Image adapted under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.Org/licenses/by/4.0/).](/cms/asset/24b66dce-3311-4947-ab96-3fd4859dea95/iebt_a_2377298_f0002_oc.jpg)

In REFLECTIONS, there was no significant impact on efficacy or tolerability when switching from reference infliximab to GP1111 [Citation39]. During the 24-week period following the first switch to GP1111 (Weeks 30–54), efficacy was sustained regardless of whether patients continued to receive GP1111, switched from reference infliximab to GP1111, or continued to receive reference infliximab. Switching had no impact on efficacy, with ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 response rates and DAS28-CRP scores at Week 54 similar across the three treatment groups [Citation39]. Results from Weeks 54‒78, when all patients received open-label treatment with GP1111, demonstrated that ACR20 response rates and DAS28-CRP scores were sustained, with no clinically meaningful differences in efficacy between patients who maintained GP1111 throughout the 78 weeks of the study and those who switched from reference infliximab to GP1111 [Citation40]. During Weeks 30‒54 and 54‒78, there were no clinically meaningful differences in immunogenicity between the treatment groups [Citation39,Citation40].

In a meta-analysis, seven randomized controlled clinical trials, including REFLECTIONS, were assessed [Citation41]. This analysis covered six infliximab biologic agents (ABP 710, BCD-055, CT-P13, GP1111, NI-071, SB2) and 3,168 patients with active RA and an inadequate response to MTX. The meta-analysis indicated no significant difference in ACR20 response rates and serious AEs between infliximab biosimilars and reference infliximab [Citation41].

3.2. Real-world evidence for switching from another infliximab biosimilar to GP1111

In the years following the approval of infliximab biosimilars, only limited data on switching from one biosimilar to another became available. An evaluation based on data of the Danish DANBIO registry provided new insights in RA and other inflammatory rheumatic diseases. In this observational cohort study of 1,605 patients with RA, psoriatic arthritis, or axial spondyloarthritis, outcomes were investigated after a nationwide infliximab biosimilar-to-biosimilar switch from CT-P13 to GP1111 [Citation42]. The switch was based on Danish guidelines recommending the use of the cheapest infliximab medicine available in the absence of individual patient considerations [Citation43]. Treatment retention at 1 year following switches between biosimilars was high (80–87% in patients with all conditions who switched with no prior reference infliximab treatment exposure, and 90–96% in patients who switched with prior reference infliximab experience) [Citation42]. Withdrawal rates were lower in reference infliximab-experienced patients than in reference infliximab-naïve patients across all indications (statistically significant in patients with RA: hazard ratio 0.36; 95% confidence interval 0.19, 0.68; and in patients with psoriatic arthritis: hazard ratio 0.23; 95% confidence interval 0.07, 0.75). Disease activity in individual patients 4 months pre and post-switch was stable, with no clinically relevant differences [Citation42]. These real-world data support the effectiveness and safety of switching to GP1111 from another infliximab biosimilar in patients with RA and related disorders.

In patients with IBD, multiple switching between GP1111 and SB2 or CT-P13 has been investigated in two real-world studies. A multicenter, observational, retrospective study of 87 pediatric patients with CD or UC in the Sicilian Network for IBD found that over a median follow-up of 15 months, 20 (23%) were multiply switched from biosimilar CT-P13 to GP1111 or SB2, or vice versa [Citation44]. At 12 months, 66% of patients had achieved clinical remission, 91% persisted with treatment, and there was a low incidence of nonserious AEs [Citation44]. In addition, an observational, retrospective study of switching in patients with IBD at a single center in Italy reported the results for 10 patients who switched between reference infliximab and/or three biosimilars (GP1111, SB2, and CT-P13). After two to four switches, disease activity, as determined by the Harvey–Bradshaw Index or the Partial Mayo Score, either remained stable (n = 6) or decreased (n = 4) for all patients [Citation45]. These data suggest that in real-world clinical practice, multiple successive switches between GP1111 and other infliximab biosimilars appear to be effective with an acceptable safety profile in patients with IBD.

4. Administration of GP1111

Physicochemical and biological analyses have demonstrated that GP1111 is not negatively affected by reconstitution, dilution, or extended storage of diluted preparations required for IV infusion in clinical practice [Citation46]. Following reconstitution (10 mg/mL), the physicochemical and biological stability of GP1111 was maintained for 30 days in refrigerated storage (5°C [±3°C]) and for 14 days at room temperature (25°C [±2°C] and 60% [±5%] relative humidity). After dilution (0.4 mg/mL or 4.0 mg/mL) for IV infusion, GP1111 stability was maintained for up to 30 days in refrigerated storage or at room temperature [Citation46].

5. Cost-effectiveness of GP1111

Due to price competition introduced by biosimilars, increasing acceptance of biosimilars could result in many more patients benefiting from biologic therapies [Citation26]. The budget impact of various treatment sequences in patients in Thailand with RA for whom three or more conventional synthetic DMARDs had failed was analyzed [Citation47]. The treatments analyzed included targeted therapies for RA approved and marketed in Thailand by 2019, including two infliximab biosimilars (CT-P13 and GP1111). Direct medical costs relevant to healthcare payers were also included in the model. The results for the base case scenario and various sensitivity analyses showed that the treatment sequence of rituximab as first-line therapy, followed by GP1111, tofacitinib, and tocilizumab, had the smallest impact on the budget for the treatment of moderate-to-severe RA over 5 years. The second lowest budget impact was the treatment order of GP1111 as first-line therapy and rituximab as second-line therapy, followed by tofacitinib and tocilizumab. These results suggest that GP1111 was cost-effective when used after the failure of conventional synthetic DMARDs [Citation47].

In an Italian survey of respondents from 26 pediatric IBD departments in Italy, most centers (n = 20) reported switching from the reference medicine to a biosimilar in everyday clinical practice, and most centers (n = 20) did not register any acute side effects. All centers used infliximab biosimilars, including two centers that used GP1111, and all centers considered cost savings as the main benefit of biosimilars [Citation48].

6. Discussion and conclusion

The totality of evidence for GP1111 compared to reference infliximab led to its approval in 2018 for use in RA, CD, UC, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and plaque psoriasis. Evidence gathered in the 5 years following the approval of GP1111 underscores the safety and efficacy profile of GP1111. Clinical and real-world data in the RA and IBD settings demonstrate that switching from reference infliximab or another infliximab biosimilar to GP1111 does not appear to have an impact on efficacy, safety, or immunogenicity [Citation37,Citation39,Citation40,Citation42,Citation44,Citation45]. In real-life settings, patients are likely to switch multiple times between GP1111 and other infliximab biosimilars, and it is reassuring that in doing so, efficacy and safety appear to be maintained. These additional post-approval data for GP1111 are particularly important to guide treatment decisions and provide reassurance to healthcare professionals and patients who may have concerns, particularly when considering switching between infliximab biosimilars.

In patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, there remains a need for access to biologics and appropriate timing for initiation of treatment with these agents [Citation49,Citation50]. After considering effectiveness, safety, and treatment recommendations, cost may also determine which biologic is used and when. Although limited, available data suggest that GP1111 is a cost-effective treatment option that may help improve access to or enable earlier use of biologic therapy in this patient population [Citation47,Citation48].

In conclusion, experience for GP1111 five years after approval in patients with RA and IBD, based on clinical trials and real-world evidence, supports its continued safe and effective use.

7. Expert opinion

In the 5 years since the approval of GP1111 in Europe, real-world evidence has supported the safety and efficacy of GP1111 in patients with RA and IBD, including scenarios where patients switched to GP1111 from another infliximab biosimilar or the reference medicine. In the next 5 years, it is reasonable to expect that further real-world data will emerge supporting the safety and efficacy of the routine use of GP1111 across all reference infliximab-approved indications. Since the approval of CT-P13 (Remsima®), the first infliximab biosimilar, increased understanding of biosimilar development and regulatory approval have contributed to a change in the perception of IBD experts, demonstrating an increase in confidence to prescribe biosimilars [Citation51,Citation52].

With infliximab biosimilars in use across healthcare systems globally, the volume of evidence for the positive economic impact of infliximab biosimilars should also increase over the next 5 years. The impact on real-world outcomes in clinical settings has been significant, particularly regarding the savings incurred in switching from reference biologic therapy to biosimilars [Citation26]. As savings are realized in the treatment of patients receiving infliximab across various healthcare systems, these savings may be reinvested in the care of patients eligible for infliximab therapy, leading to wider patient access to infliximab. In many healthcare systems, there is a strong preference to prescribe biosimilars, while the option to prescribe infliximab has been limited. In comparison with healthcare systems with a free choice, we do not observe worse patient outcomes. This may also lead to changes in attitude toward the use of infliximab by payors who are balancing the contradicting forces of optimizing patient care while managing limited healthcare resources. In addition, in countries where governments, and thereby taxes, pay for healthcare, the savings incurred by prescribing infliximab biosimilars over the reference medicine may also contribute to increased availability of resources for new, innovative treatments, highlighting an advantage not just for patients who require infliximab therapy for their disease but also for other patients living with other health conditions that are currently not satisfactorily managed [Citation53].

As prescription of infliximab biosimilars becomes more commonplace, it would also be prudent to continually update the literature for differences in adherence between reference infliximab and biosimilars, including GP1111, to better understand how treatment patterns are evolving with the advancement of biosimilars. An adherence study published in 2022 has shown that adherence for reference infliximab was greater (64%) than infliximab biosimilars (36%) in patients who were prevalent infliximab users; however, larger sample sizes are needed to accurately assess adherence in patients using infliximab biosimilars [Citation54].

Five years from now, we expect there to be more research into how different factors may influence the likelihood of both a physician prescribing biosimilar treatment and a patient’s willingness to receive biosimilar treatment, given patients’ high level of trust in specialists’ recommendations and their widespread use of external sources of information [Citation55]. It will also be interesting to see how factors including age, level of education, the presence of comorbidities, and disease-related complications may influence adherence to biosimilars.

Article highlights

Clinical studies have demonstrated the biosimilarity of GP1111, an infliximab biosimilar, to reference infliximab

In the Phase III, randomized, double-blind, REFLECTIONS trial, there was no significant impact on efficacy or tolerability when switching from reference infliximab to GP1111 in patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) despite methotrexate therapy

GP1111 was approved by the European Medicines Agency in May 2018

Since approval, real-world studies have further demonstrated the effectiveness and safety of GP1111 in patients with RA and inflammatory bowel disease, including in cases where patients have switched to GP1111

Limited cost-effectiveness data have also indicated that GP1111 is a cost-saving medicine

Abbreviations

ACR20: American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement criteria; ACR50: American College of Rheumatology 50% improvement criteria; ACR70: American College of Rheumatology 70% improvement criteria; ADA: antidrug antibody; AE: adverse event; bDMARD: biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; CD: Crohn’s disease; DAS28-CRP: Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, with four components based on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; DMARD: disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; ECCO: European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation; EULAR: European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IV: intravenous; MTX: methotrexate; PK: pharmacokinetics; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Declaration of interest

TWJ Huizinga reports receiving research support/lecture fees/consultancy fees from Abbott, Ablynx, Biotest, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Galapagos, Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB. J Heyn and M Zabransky report employment with Sandoz/HEXAL AG. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has received research, speaking and/or consulting support from Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline/Stiefel, AbbVie, Janssen, Alovtech, vTv Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Samsung, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen, Dermavant, Arcutis, Novartis, Novan, UCB, Helsinn, Sun Pharma, Almirall, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Mylan, Celgene, Ortho Dermatology, Menlo, Merck & Co, Qurient, Forte, Arena, Biocon, Accordant, Argenx, Sanofi, Regeneron, the National Biological Corporation, Caremark, Teladoc, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ono, Micreos, Eurofins, Informa, UpToDate, and the National Psoriasis Foundation. They hold stock in Causa Research and Sensal Health. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors met criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). The authors did not receive payment related to the development of this manuscript. Medical writing support was provided by Dan Hami, of Rhea, OPEN Health Communications, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines (www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Remicade summary of product characteristics [Internet]. European Medicines Agency. 2022 [updated 2022 Sep 26; cited 2022 Nov 16]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/remicade-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- REMICADE highlights of prescribing information [Internet]. US Food and Drug Administration. 2020 [cited 2023 Nov 16]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/103772s5401lbl.pdf

- McClellan JE, Conlon HD, Bolt MW, et al. The ‘totality-of-the-evidence’ approach in the development of PF-06438179/GP1111, an infliximab biosimilar, and in support of its use in all indications of the reference product. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819852535. doi: 10.1177/1756284819852535

- Kornbluth A. Infliximab approved for use in crohnʼs disease: a report on the FDA GI advisory committee conference. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1998;4:328–329. doi: 10.1097/00054725-199811000-00014

- Smolen JS, Emery P. Infliximab: 12 years of experience. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:S2. doi: 10.1186/1478-6354-13-S1-S2

- Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Infliximab for Crohn’s disease: more than 13 years of real-world experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:490–501. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx072

- Wilhelm SM, McKenney KA, Rivait KN, et al. A review of infliximab use in ulcerative colitis. Clin Ther. 2008;30:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.02.014

- Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:685–699. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655

- Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73:924–939. doi: 10.1002/acr.24596

- Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:4–22. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz180

- Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, et al. ACG clinical guideline: management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:481–517. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2018.27

- Feuerstein JD, Ho EY, Shmidt E, et al. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2496–2508. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.022

- Ruemmele FM, Veres G, Kolho KL, et al. Consensus guidelines of ECCO/ESPGHAN on the medical management of pediatric Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1179–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.04.005

- de Zoeten EF, Pasternak BA, Mattei P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of perianal Crohn disease: NASPGHAN clinical report and consensus statement. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:401–412. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182a025ee

- Raine T, Bonovas S, Burisch J, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;16:2–17. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab178

- Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, et al. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1450–1461. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.006

- Turner D, Ruemmele FM, Orlanski-Meyer E, et al. Management of paediatric ulcerative colitis, part 2: acute severe colitis-an evidence-based consensus guideline from the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization and the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67:292–310. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0000000000002036

- Turner D, Travis SP, Griffiths AM, et al. Consensus for managing acute severe ulcerative colitis in children: a systematic review and joint statement from ECCO, ESPGHAN, and the Porto IBD Working Group of ESPGHAN. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:574–588. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.481

- Ramiro S, Nikiphorou E, Sepriano A, et al. ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:19–34. doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-223296

- Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, et al. 2019 update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71:1285–1299. doi: 10.1002/acr.24025

- Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:700–712. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217159

- Singh JA, Guyatt G, Ogdie A, et al. Special article: 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:5–32. doi: 10.1002/art.40726

- Nast A, Smith C, Spuls PI, et al. EuroGuiDerm guideline on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris – part 1: treatment and monitoring recommendations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2461–2498. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16915

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Kim H, Alten R, Avedano L, et al. The future of biosimilars: maximizing benefits across immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Drugs. 2020;80:99–113. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01256-5

- Car E, Vulto AG, Houdenhoven MV, et al. Biosimilar competition in European markets of TNF-alpha inhibitors: a comparative analysis of pricing, market share and utilization trends. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1151764. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1151764

- Zessly summary of product characteristics [Internet]. European Medicines Agency. 2023 [Updated 2023 July 14; cited 2023 Nov 16]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/zessly-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- IXIFI highlights of prescribing information [Internet]. US Food and Drug Administration. 2020 [updated 2020 Jan; cited 2020 Nov 16]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761072s006lbl.pdf

- Zessly (infliximab) summary of opinion (initial authorisation) [Internet]. European Medicines Agency. 2018 [updated 2018 Mar 22; cited 2023 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/smop-initial/chmp-summary-positive-opinion-zessly_en.pdf

- Daller J. Biosimilars: a consideration of the regulations in the United States and European Union. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;76:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.12.013

- Derzi M, Johnson TR, Shoieb AM, et al. Nonclinical evaluation of PF-06438179: a potential biosimilar to Remicade® (infliximab). Adv Ther. 2016;33:1964–1982. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0403-9

- Lerch TF, Sharpe P, Mayclin SJ, et al. Crystal structures of PF-06438179/GP1111, an infliximab biosimilar. BioDrugs. 2020;34:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s40259-019-00390-1

- CHMP assessment report: Zessly (international non-proprietary name: infliximab). European Medicines Agency; 2018 [Updated 2018 Mar 22; cited 2023 Nov 16]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/zessly-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

- Palaparthy R, Rehman MI, von Richter O, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of PF-06438179/GP1111 (an infliximab biosimilar) and reference infliximab in patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:1065–1074. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2019.1635583

- Palaparthy R, Udata C, Hua SY, et al. A randomized study comparing the pharmacokinetics of the potential biosimilar PF-06438179/GP1111 with Remicade® (infliximab) in healthy subjects (REFLECTIONS B537-01). Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:329–336. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2018.1446829

- Al-Salama ZT. PF-06438179/GP1111: an infliximab biosimilar. BioDrugs. 2018;32:639–642. doi: 10.1007/s40259-018-0310-5

- Cohen SB, Alten R, Kameda H, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing PF-06438179/GP1111 (an infliximab biosimilar) and infliximab reference product for treatment of moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:155. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1646-4

- Kameda H, Uechi E, Atsumi T, et al. A comparative study of PF-06438179/GP1111 (an infliximab biosimilar) and reference infliximab in patients with moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis: a subgroup analysis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020;23:876–881. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13846

- Alten R, Batko B, Hala T, et al. Randomised, double-blind, phase III study comparing the infliximab biosimilar, PF-06438179/GP1111, with reference infliximab: efficacy, safety and immunogenicity from week 30 to week 54. RMD Open. 2019;5:e000876. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000876

- Cohen SB, Radominski SC, Kameda H, et al. Long-term efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the infliximab (IFX) biosimilar, PF-06438179/GP1111, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after switching from reference IFX or continuing biosimilar therapy: week 54-78 data from a randomized, double-blind, phase III trial. BioDrugs. 2020;34:197–207. doi: 10.1007/s40259-019-00403-z

- Lee YH, Song GG. Comparative efficacy and safety of infliximab and its biosimilars in patients with rheumatoid arthritis presenting an insufficient response to methotrexate: a network meta-analysis. Z Rheumatol. 2023;82:114–122. doi: 10.1007/s00393-021-01040-0

- Nabi H, Hendricks O, Jensen DV, et al. Infliximab biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease: clinical outcomes in real-world patients from the DANBIO registry. RMD Open. 2022;8:e002560. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002560

- RADS recommendation regarding the use of biosimilar infliximab and etanercept. 2016. [updated 2016 Jun 12; cited 2024 Jun 12]. Available from: https://www.regioner.dk/media/3488/rads-notat-om-anvendelsen-af-biosimilaere-juni-2016.pdf

- Dipasquale V, Pellegrino S, Ventimiglia M, et al. Real-life experience of infliximab biosimilar in pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease: data from the Sicilian Network for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;34:1007–1014. doi: 10.1097/meg.0000000000002408

- Macaluso FS, Casà A, Renna S, et al. Switching from SB2 to PF-06438179/GP1111 and back in inflammatory bowel disease: “the superswitchers”. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55:424–425. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2022.12.008

- Vimpolsek M, Gottar-Guillier M, Rossy E. Assessing the extended in-use stability of the infliximab biosimilar PF-06438179/GP1111 following preparation for intravenous infusion. Drugs R D. 2019;19:127–140. doi: 10.1007/s40268-019-0264-1

- Osiri M, Dilokthornsakul P, Chokboonpium S, et al. Budget impact of sequential treatment with biologics, biosimilars, and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in Thai patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Ther. 2021;38:4885–4899. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01867-8

- Dipasquale V, Martinelli M, Aloi M, et al. Real-life use of biosimilars in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a nation-wide web survey on behalf of the SIGENP IBD working group. Paediatr Drugs. 2022;24:57–62. doi: 10.1007/s40272-021-00486-8

- Taylor PC, Woods M, Rycroft C, et al. Targeted literature review of current treatments and unmet need in moderate rheumatoid arthritis in the United Kingdom. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:4972–4981. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab464

- Danese S, Allez M, van Bodegraven AA, et al. Unmet medical needs in ulcerative colitis: an expert group consensus. Dig Dis. 2019;37:266–283. doi: 10.1159/000496739

- Danese S, Fiorino G, Raine T, et al. ECCO position statement on the use of biosimilars for inflammatory bowel disease–an update. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:26–34. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw198

- Park SH, Park JC, Lukas M, et al. Biosimilars: concept, current status, and future perspectives in inflammatory bowel diseases. Intest Res. 2020;18:34–44. doi: 10.5217/ir.2019.09147

- Goll GL, Kvien TK. Improving patient access to biosimilar tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in immune-mediated inflammatory disease: lessons learned from Norway. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2023;23:1203–1209. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2023.2273938

- Alanaeme CJ, Sarvesh S, Li CY, et al. Adherence patterns in naïve and prevalent use of infliximab and its biosimilar. BMC Rheumatol. 2022;6:65. doi: 10.1186/s41927-022-00295-7

- Khoo T, Sidhu N, Marine F, et al. Perceptions towards biologic and biosimilar therapy of patients with rheumatic and gastroenterological conditions. BMC Rheumatol. 2022;6:79. doi: 10.1186/s41927-022-00309-4