ABSTRACT

Introduction

Infliximab (IFX) biosimilars are available to treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), offering cost reductions versus originator IFX in some jurisdictions. However, concerns remain regarding the efficacy and safety of originator-to-biosimilar switching. This systematic literature review evaluated safety and effectiveness of switching between IFX products in patients with IBD, including multiple switchers.

Methods

Embase, PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched to capture studies (2012–2022) including patients with IBD who switched between approved IFX products. Effectiveness outcomes: disease activity; disease severity; response to treatment; patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Safety outcomes: incidence and rate of adverse events (AEs); discontinuations due to AEs, failure rate; hospitalizations; surgeries. Immunogenicity outcomes (n, %): anti-drug antibodies; patients receiving concomitant immunomodulatory medication.

Results

Data from 85 publications (81 observational, two randomized controlled trials) were included. Clinical effectiveness outcomes were consistent with the known profile of originator IFX with no difference after switching. There were no unexpected/serious AEs after switching, and rates of AEs were generally consistent with the known profile of IFX.

Conclusions

Most studies reported that clinical, PROs, and safety outcomes for originator-to-biosimilar switching were clinically equivalent to originator responses. Limited data are available regarding multiple switches.

Protocol registration

www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero identifier is CRD42021289144.

1. Introduction

The introduction of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists represented a landmark in the clinical management of chronic conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [Citation1]. However, the high costs of biologics have had an important impact on healthcare expenditure, especially in chronic conditions, and consequently, patients have had limited access to these effective treatments [Citation2].

Infliximab (IFX; Remicade), a chimeric monoclonal IgG1 anti-TNF antibody, was the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – approved biologic for the treatment of moderate-to-severe IBD, which first gained US regulatory approval in 1998 [Citation3]. Since 2013, several IFX biosimilars have been approved by the US FDA and/or European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the clinical management of IBD [Citation4]. These include (EU and US, respectively) CT-P13 (Inflectra/Remsima; first approval [EMA]: 2013) and infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra)) [Citation5,Citation6], SB2 (Flixabi; first approval [EMA]: 2016) and infliximab-abda (Renflexis) [Citation7,Citation8], GP1111 (Zessly) and infliximab-qbtx (Ixifi; first approval [US]: 2017) [Citation9,Citation10] and ABP 710 (infliximab-axxq; Avsola; first approval [US]: 2019) [Citation11].

Biosimilars are approved following a rigorous process involving detailed analytical and functional assessments and comparative clinical studies showing that they are similar to the originator biologic in terms of safety, pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, purity and potency [Citation12]. As the development pathway for biosimilars is relatively truncated compared with originator biologics, biosimilars offer the potential for cost savings. By providing competition, biosimilars can improve patients’ access to these medications, allowing more patients the possibility of receiving a potentially more optimal treatment for their disease through additional services or access to newer medicines for those who do not or no longer respond to infliximab or other TNF inhibitors (TNFis) [Citation13,Citation14]. Indeed, biosimilars have alleviated cost-related barriers in some countries and regions, and they have enabled other countries and regions that had minimal access restrictions to channel savings into additional patient services or newer medicines for those who do not or no longer respond to TNFis.

Despite the growing availability of biosimilars and increasing published data on their highly similar clinical profiles (to their respective originators), barriers to biosimilar use exist due to issues around awareness [Citation15], incentive, education [Citation16,Citation17], experience [Citation17], insurance coverage, healthcare system reimbursement, formulary inclusion, drug availability and out‐of‐pocket costs [Citation18–22]. Moreover, many healthcare providers (HCPs) and patients remain skeptical about using biosimilars instead of the originator in bio-naïve patients, as well as switching patients who have responded to an originator to a biosimilar. Lack of familiarity with biosimilars is likely to contribute to persisting doubts regarding the quality, safety and efficacy of biosimilars [Citation23–26].

A prior systematic literature review (Feagan et al.) [Citation27] published in 2019 summarized the evidence on switching between IFX biosimilars and originator in patients with a range of inflammatory disorders, including CD and UC. The 2019 analysis revealed no differences in terms of efficacy or safety associated with single switching [Citation27]. However, the data available were relatively sparse, with only six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examined. Since that initial systematic review, numerous publications have emanated in the area focusing on IBD alone. In addition, at the time of the 2019 publication, data were only available for single switches (i.e. originator IFX [oIFX] to IFX biosimilar), while relatively limited information is available regarding switching between IFX biosimilars or multiple switching [Citation28]. Moreover, few data were available in 2019 regarding the influence of switching on mucosal healing.

The aim of the present systematic literature review is to evaluate the updated and existing evidence on the safety and effectiveness of switching between IFX products (including biosimilars) in patients with IBD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and objectives

The main objective of this systematic literature review is to assess the safety and effectiveness of switching between IFX products in patients with IBD. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and immunogenic response are also assessed.

This systematic literature review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and is registered on PROSPERO (Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) to avoid duplication and reduce potential reporting bias (registration number: CRD42021289144).

2.2. Search strategy

PubMed, Embase via Ovid, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews via Ovid, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via Ovid were searched to identify English-language articles (excluding conference abstracts) published between 1 January 2012 and 17 November 2021. Hand searches of abstracts from key IBD congresses were also conducted. The search was updated to include studies published between 17 November 2021 and 4 April 2022.

The search strings included ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as the following terms for IFX biosimilars and biosimilar candidates: GP 2018, ABP 710, BCD-055, GP1111, PF-06438179, GS 071, NI 071, SB2, Flixabi, CT-P13, Emisima, Flixceli, Infliximab BS, Remsima, infliximab-dyyb and Inflectra. The search string also contained known synonyms for these molecules (see Supplementary file 1 for full search string).

2.3. Eligibility criteria

Publications of interest measured efficacy/effectiveness, safety and immunogenicity after switching (Supplementary file 2). The effectiveness outcomes measured included disease activity, disease severity and response to treatment, including PROs. Safety outcomes included the incidence and rate of adverse events (AEs), discontinuations due to AEs, failure rate, hospitalizations and surgeries. Immunogenicity outcomes included anti-drug antibodies (ADAs; n, %) and number of patients receiving concomitant immunomodulatory medication (n, %).

Studies were selected for inclusion according to the prespecified Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study framework (see Supplementary file 3 for full eligibility criteria). Briefly, publications were included if they reported real-world evidence/observational studies or Phase II – IV clinical trials (including open-label extensions [OLEs]) involving patients with IBD (CD and UC) who switched between approved IFX products (i.e. from oIFX to biosimilar IFX or vice versa, or from one IFX biosimilar to another). Publications reporting preclinical, pilot or Phase I clinical studies, protocols, case reports/studies, notes, commentaries, letters, editorials, opinions, economic model studies, meta-analyses and reviews were excluded from the analysis. Also excluded were studies reporting outcomes that were not specific to patients switching between approved IFX products or reporting outcomes for mixed treatments and not specific to a given IFX product, as well as studies in pregnant women and studies that did not report effectiveness, safety or immunogenicity following a switch between IFX products. In addition, studies in patients who received a single version of IFX (i.e. originator or biosimilar) without a switch were excluded.

2.4. Screening and data extraction

Results from each database were downloaded to EndNote bibliographic software, with duplicates removed using EndNote algorithms and by hand. To ensure transparency, duplicate citations were retained. A pre-screen of the EndNote database was conducted by a single researcher to exclude records that were noticeably irrelevant (e.g. relating to animal studies or preclinical trials). The excluded records were evaluated by a second researcher and retained in an EndNote folder for transparency. References for which there was a disagreement were retained for title/abstract screening. Titles and abstracts, followed by full texts, were screened for eligibility in parallel by two independent researchers. Reasons for exclusion were provided and cross-checked by both reviewers. Data from full-text articles were extracted by one reviewer into a prespecified Microsoft Excel grid, which was assessed for accuracy by a second reviewer. Reference lists from eligible reviews and manuscripts were also examined to identify any publications that may not have appeared in the database searches.

2.5. Quality/bias assessment

RCTs were assessed for quality using the Cochrane risk-of-bias (RoB) 2.0 tool [Citation29]. Observational longitudinal studies (prospective or retrospective) were assessed for quality/risk of bias using the Newcastle – Ottawa Scale (NOS) [Citation30], which was also used for any non-randomized studies. Observational cross-sectional studies were assessed for quality using the adapted NOS [Citation31].

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

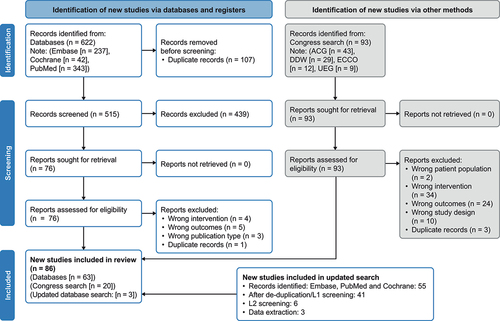

A total of 622 records (Embase, n = 237; Cochrane, n = 42; PubMed, n = 343) were identified from database searches between 1 January 2012 and 17 November 2021 (). An additional 55 records were identified in the updated search from 17 November 2021 to 4 April 2022. There was a 94% level of agreement in screening between researchers. After removal of duplicates, screening and application of eligibility criteria (based on interventions, outcomes, patient population and study design), a total of 85 publications (65 full-text articles, 20 conference abstracts) were included in this analysis which comprised 84 studies in total (81 observational studies; and two clinical trials, covered by four publications).

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram.

3.2. Study characteristics

Most studies were conducted in Europe (n = 63) [Citation32–40]; remaining studies were reported in the United States (n = 8) [Citation41–48], Australia (n = 1 longitudinal study) [Citation11], or Asia (n = 6) [Citation49–54], and four were multinational studies [Citation55–58].

The studies reported multiple switching (n = 7) [Citation34,Citation43,Citation47,Citation59–61], biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching (n = 7) [Citation34,Citation47,Citation59,Citation60,Citation62–64], biosimilar-to-originator switching (n = 3) [Citation35,Citation55,Citation65], and single switch from originator to biosimilar (n = 63) (). Sample sizes for these studies ranged from 9–1409 participants.

Among the longitudinal studies assessed for risk of bias using NOS (n = 52), 18 (34.6%), 13 (25.0%), and 16 (30.8%) were considered to have a high, medium, and low risk of bias, respectively. The RCTs were judged to have a low risk of bias based on the Cochrane RoB tool.

3.3. Clinical effectiveness outcomes: IFX originator-to-biosimilar

3.3.1. Randomized controlled studies (n = 2)

Four publications presenting results from two RCTs were identified, including three reporting data from the NOR-SWITCH trial in Norway [Citation66–68] and one reporting the multinational PLANET-CD trial [Citation55] (). Both included patients with IBD (CD and/or UC) who switched from oIFX to CT-P13.

Table 1. RCTs evaluating switching from IFX originator (oIFX) to biosimilar (N = 2), IFX biosimilar to oIFX (N = 1) or IFX biosimilar maintenance (N = 1).

The NOR-SWITCH trial included Norwegian patients with UC (n = 93) and CD (n = 155), and other inflammatory conditions (n = 482) who had received ≥6 months’ treatment with oIFX. Patients were randomized 1:1 to continue oIFX (maintenance group) or switch to CT-P13 treatment (switch group) for 52 weeks of follow-up in the main study [Citation68], followed by a 26-week OLE trial where all patients received CT-P13 treatment [Citation66,Citation67]. Similar clinical outcomes (Harvey – Bradshaw Index [HBI], Physician’s Global Assessment [PGA], C-reactive protein [CRP], fecal calprotectin [Fc], remission, disease worsening) were reported after switching in the main and OLE trials. At baseline of the main study, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) disease duration in patients with CD and UC was 14.3 (8.5) and 11.5 (7.5) years, respectively, in the switch group [Citation67]. NOR-SWITCH reported a decrease in partial Mayo Score (PMS) at 12 months versus baseline; and in the OLE, PMS was comparable between the maintenance and switch groups [Citation66–68]. This was also true for HBI, CRP, and Fc. HBI increased at 12 months from baseline in the maintenance and switch groups, and decreased at 18 months in the switch group [Citation68]. PGA did not show a significant mean difference at 12 months among 77 patients with CD after switching to CT-P13 (mean [SD], 0.93 [1.4]) versus baseline (0.88 [1.56]), suggesting no worsening of disease activity after transitioning to biosimilar treatment [Citation66–68].

In the multinational PLANET-CD study reported by Ye et al. (2019), patients with CD (n = 220) who had not responded to or were intolerant to non-biological treatments were randomized to initiate CT-P13 (n = 111) or oIFX (n = 109) as follows: CT-P13 → CT-P13 (n = 56), CT-P13 → oIFX (n = 55), oIFX → oIFX (n = 54) or oIFX → CT-P13 (n = 55), with switching at week 30 [Citation55]. Among 109 patients who initiated oIFX, both the oIFX → oIFX and oIFX → CT-P13 switch groups showed similar Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI)-70 and CDAI-100 response rates and clinical remission rates at weeks 6, 14, 30 and 54. Mean Fc and CRP concentrations decreased from baseline to week 6 and then remained stable, with no notable differences between groups at any visit.

Ye et al. (2019) also assessed endoscopy findings in PLANET-CD to provide objective information about the degree of inflammation [Citation55]. The presence and level of improvement of mucosal damage were evaluated by colonoscopy at baseline and week 54, and mucosal healing was assessed using the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD); there was no significant change in SES-CD scores between the various switching patterns () [Citation55].

Table 2. Mucosal healing associated with switching from (A) IFX originator (oIFX) to biosimilar (N = 4) or (B) IFX biosimilar to oIFX or biosimilar maintenance (N = 1) in patients with CD in RCTs and longitudinal studies.

Both RCTs included PRO assessments. In NOR-SWITCH, there was no substantial change in the EQ-5D index score, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) physical component summary score or Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire at 12 months, or in the IBD Questionnaire (IBDQ) score at 12 and 18 months from baseline after switching, indicating that CT-P13 has similar efficacy to oIFX [Citation66–68]. In PLANET-CD, a decrease from baseline in 2-item patient-reported outcome (PRO-2; mean [SD]) scores corresponding with improvement (−10.7 [5.94], n = 47) and an increase from baseline in the Short IBDQ (SIBDQ) score (17.0 [10.54], n = 55) were observed at 12.5 months post switch [Citation55]. There were no notable differences in PRO-2 scores between the CT-P13 and oIFX groups at any time-point in the study.

3.3.2. Longitudinal studies (n = 60)

Most longitudinal studies included in this analysis were observational prospective studies. The included publications commonly reported clinical outcomes of non-cardiac CRP, clinical response, remission and disease worsening (Table S1) [Citation11,Citation32–42,Citation44–46,Citation49–51,Citation53,Citation54,Citation57,Citation59–61,Citation69–112].

3.3.2.1. Clinical response (endoscopic)

Four studies reported Mayo Score as an outcome in patients with UC [Citation45,Citation69,Citation72,Citation77]. An Italian observational prospective study conducted by Armuzzi et al. reported a significant decrease (n = 87, p<0.001) in Mayo Score at 6 months versus baseline, which remained stable at 12 months in patients who switched from oIFX to CT-P13 [Citation69]. Furthermore, in the subgroup of patients with UC who had been previously exposed to IFX and were already responders to therapy and likely under remission at the time of switching, there was a significant further improvement in total Mayo Score and endoscopic Mayo subscore at 12 months [Citation69]. Padival et al. reported a similar improvement from baseline in Mayo Score, with no significant change after switching from oIFX to SB2 [Citation113]. Endoscopic Mayo subscore was used as an outcome for endoscopic severity in four further studies [Citation71,Citation72,Citation81,Citation102].

PMS was reported in 21 studies involving patients with UC. An observational prospective study reported a significant response (p<0.001) in PMS among patients switching from oIFX to SB2 (n = 17) compared with patients switching from CT-P13 to SB2 (n = 43) and multiple switchers (n = 24), indicating better clinical response in the single-switch patients [Citation60,Citation94]. Massimi et al. (2021) reported significant changes in PMS associated with clinical remission (p = 0.02) at first follow-up (135 days) versus baseline in patients (n = 85) switching from oIFX to SB2 [Citation96]. Another observational prospective study (n = 158) reported no mean change in PMS after 12.5 months of follow-up in patients switching from oIFX to CT-P13 when compared with baseline [Citation59]. A Finnish observational study (n = 30) reported a non-significant decline in PMS (p = 0.07) after switching from oIFX to CT-P13 compared with baseline [Citation82]. Another observational prospective study (n = 31) by Guerra Veloz et al. reported a non-significant change (p = 0.058) in median PMS at 12 months after switching to CT-P13 [Citation114]. Similarly, Padival et al. (2020, 2021) reported a non-significant decline (p = 0.8) in PMS after switching [Citation45,Citation46].

Mucosal healing (SES-CD) was reported in three longitudinal studies of patients with CD who switched from oIFX to biosimilars () [Citation46,Citation69–72]. None of these studies showed a significant change in mean SES-CD score at 6 and 12 months after switching. Moreover, in a 12-month follow-up of the prospective study by Tursi et al. (2019), 16/19 (84%) patients achieved mucosal healing, suggesting longer-term maintenance of disease stability in these patients [Citation72].

Most of the studies that used colonoscopy to assess endoscopic improvement did not describe a standardized formal reporting system for endoscopic assessments [Citation41,Citation48,Citation55,Citation58,Citation72,Citation81,Citation86,Citation95,Citation102,Citation115]. Chaparro (2019) used global endoscopic criteria of mild, moderate or severe activity for patients with CD [Citation81]. For post-surgical patients with CD, endoscopic activity was rated according to Rutgeerts score, and for those with ileal involvement, only complete colonoscopies with ileoscopy were assessed.

3.3.2.2. Clinical disease remission

A total of seven studies reported CDAI scores in patients with CD [Citation36,Citation49,Citation50,Citation53,Citation56,Citation57,Citation91]. An observational longitudinal study (n = 23) in South Korea and the EU reported similar mean CDAI scores from day 0 (time of switch) to 60 months, indicating relative disease stability after switching from oIFX to CT-P13 [Citation57]. Another publication by the same authors reported that a substantial proportion of patients had CDAI scores of<150 points within the same time intervals [Citation56]. Schmitz et al. (2018) also observed that the numbers of patients with CD reporting moderate disease activity (CDAI 150–400) after switching from oIFX to biosimilar were comparable between the four time points measured, with no significant difference in activity scores before and after switching [Citation36]. HBI was reported in 26 studies, three of which reported a significant change in HBI following switching from oIFX to biosimilar IFX [Citation69,Citation96,Citation116]. One observational prospective study (n = 87) noted a significant decline in HBI (p = 0.01) at 6 and 12 months after switching [Citation69,Citation70]. Similarly, Guerra Veloz et al. (n = 116) observed a significant difference (p = 0.001) in HBI (median [interquartile range (IQR)]) when compared between 0 and 12 months following switching [Citation115]. Macaluso et al. (n = 43) observed significantly improved HBI (p<0.001) in the multiple-switch group when compared with single-switch groups (oIFX → SB2 and CT-P13 → SB2) [Citation60,Citation94]. In most of the remaining studies, HBI scores remained stable after switching from oIFX to biosimilar.

Improved pediatric CDAI (PCDAI) scores (<10 points) in a pediatric IBD population (n = 42) were observed 6 months after switching from oIFX to biosimilar CT-P13 versus baseline (p = 0.005), with retention of overall patients’ stability in both CD and UC populations (van Hoeve et al., 2019) [Citation107]. The proportion of patients in clinical remission did not change after switching. Other studies that evaluated PCDAI score as an outcome showed stability or no change in PCDAI scores at 12 months following switching [Citation51,Citation85]. Cheon et al. (2021) reported that PCDAI scores were stable at 12 months and maintained for up to 60 months after switching [Citation56,Citation57].

Two observational studies reported PGA in patients with IBD who switched from oIFX to CT-P13 [Citation85,Citation101]. Both studies reported non-significant changes in PGA score over 12 months suggesting maintenance of clinical activity after switching.

A total of 23 studies reported remission outcomes in patients with IBD. In a prospective observational study (n = 361) by Bronswijk et al. (2020), in which over 60% of patients experienced clinical remission at baseline, a high hemoglobin level and low PRO-2 were significantly associated with clinical remission at 6 months post switch [Citation79]. Disease-worsening end points were reported in five studies among patients with IBD switching from oIFX to biosimilar [Citation11,Citation44,Citation79,Citation102]. Ho et al. (2020) reported that 347 (25%) patients in the CT-P13 group versus 375 (27%) patients in the oIFX group had disease worsening requiring acute care or treatment failure, suggesting better (p<0.01 for non-inferiority) tolerability of CT-P13 versus oIFX [Citation42]. However, the authors concluded that there was no increased risk of disease worsening for patients who switched to infliximab-dyyb compared with patients who remained on oIFX [Citation42]. A total of 114 (10%) patients in the CT-P13 group required acute care due to disease worsening compared with 174 (15%) patients in the oIFX group (p<0.01) [Citation42]. A separate study reported endoscopic remission in 38/119 (55%) patients before switch and 45 (65%) (p > 0.05) after switching from oIFX to CT-P13, with endoscopic worsening observed in 10/119 (15%) patients ~8 months after switching [Citation102].

Nine longitudinal studies in patients with IBD reported PROs after switching from oIFX to biosimilar IFX [Citation37–39,Citation59,Citation79,Citation88,Citation91,Citation99,Citation104,Citation112,Citation116]. In one prospective study (n = 361), the median PRO-2 decreased significantly from baseline to first infusion and at 6 months after infusion in patients who switched from oIFX to biosimilar [Citation79]. Another study by Razanskaite et al. (2017) showed a significant increase in median IBD-Control-8 subscore, which improved during switch and at the third dose [Citation104]; however, IBD-Control-Visual Analogue Scale showed no significant difference (p = 0.65) in mean value after the third dose of CT-P13 compared with before the switch.

Three studies reported PROs among patients with CD who transitioned from oIFX to biosimilar [Citation76,Citation91,Citation106]. No change was observed in the Short Health Scale mean composite score at 12 months after switching to biosimilar in a prospective study (n = 195) conducted by Bergqvist et al. (2018), indicating similar therapeutic effectiveness of biosimilar to oIFX [Citation76]. In a small observational prospective study (n = 26), Huoponen et al. (2020) [Citation91] identified a significant increase (p = 0.018) in median (IQR) SIBDQ score at 3 months (193 [190–206]; n = 20) compared with baseline (188 [170–198]; n = 26), correlating with improved clinical outcomes after switching. Across studies, there were generally no notable differences between the biosimilar IFX and oIFX groups in terms of change from baseline in SIBDQ score among patients with IBD. Similarly, there were no notable changes from baseline in EQ-5D [Citation58] score post switch.

3.3.2.3. Biological disease remission

A total of 12 and 27 longitudinal studies reported Fc and CRP outcomes, respectively, for patients with IBD who switched from oIFX to biosimilar (Tables S2 and S3). In general, mean Fc and CRP concentrations decreased from baseline (start of oIFX therapy) to week 6, then remained stable with no notable differences following switching. Across studies, median Fc concentrations post switch showed no significant change versus Fc concentrations at baseline, which corresponded to the achievement of biochemical clinical remission among patients (Table S2) [Citation32,Citation34,Citation37–39,Citation45,Citation46,Citation51,Citation64,Citation80,Citation82,Citation85,Citation89,Citation91,Citation92,Citation95,Citation96,Citation106]. In a retrospective study by Binkhorst et al. (2018) involving 197 Dutch patients, there was a slight decline in median Fc concentration 3.7 months following switch from oIFX to CT-P13, although still within the normal range as was before switch [Citation32]. In a UK study by Gervais et al. (2018) (n = 27), despite some fluctuations in median Fc concentration from baseline (113.5 mg/kg) to month 6 (148 mg/kg) and month 12 (99 mg/kg) after switching from oIFX to CT-P13, there was no significant difference between time-points (p = 0.98) [Citation85]. Similarly, CRP concentrations were generally maintained following switching across the various observational studies (Table S3) [Citation11,Citation32,Citation34,Citation36–39,Citation41,Citation45,Citation46,Citation51,Citation59,Citation60,Citation62–64,Citation79–81,Citation83–85,Citation87,Citation89,Citation92,Citation94–96,Citation98,Citation99,Citation102–104,Citation107,Citation108,Citation117]. For example, no significant change in median CRP was observed between time of switch (1.4 mg/L) to 6 months after infusion (1.4 mg/L; p = 0.39) in a Belgian study by Bronswijk et al. (2020) involving 361 patients with IBD switching from oIFX to CT-P13 [Citation79]. In another prospective observational study involving 148 German patients switching from oIFX to SB2, Fischer et al. (2021) observed little change in CRP concentrations at 18 months compared with baseline, with a slight decline at 6 months and elevation at 12 months [Citation83].

3.4. Clinical effectiveness outcomes: biosimilar-to-IFX originator, biosimilar-to-biosimilar, biosimilar maintenance, or multiple switching

3.4.1. Randomized controlled studies (n = 1)

The PLANET-CD study [Citation55] evaluated reverse switching from CT-P13 to oIFX versus continued CT-P13 treatment in patients with CD (). Baseline (i.e. week 30) CDAI scores were higher in reverse-switch patients (n = 55) than in patients who continued CT-P13 treatment (n = 56). At 12.5 months, fewer reverse-switch patients achieved CDAI-70 (n = 39, 71%) and CDAI-100 (n = 38, 69%) change scores compared with those who continued CT-P13 (n = 44, 79% and n = 43, 77%, respectively) [Citation55]. Mucosal healing occurred in 12 (26.1%, n = 46) reverse-switch group, where the mean SES-CD score was 10.4 (7.79); there was no significant change in SES-CD score in either maintenance or reverse switch group ().

Among reverse-switch patients (n = 55), mean [SD] PRO-2 score (−12.5 [5.92], n = 45) decreased and mean [SD] SIBDQ score (18.9 [10.94]) increased at 12.5 months from baseline after switching. Similar results were obtained at the same time-point in both the mean [SD] PRO-2 score (−12.8 [4.9], n = 40) and mean [SD] SIBDQ score (20.2 [13.1]) in the reverse-switch group [Citation55]. Hence, biosimilar switch, biosimilar maintenance and reverse switch all appear to be associated with amelioration in clinical outcomes.

3.4.2. Longitudinal studies (biosimilar IFX to oIFX, n = 3; biosimilar-to-biosimilar, n = 6; or multiple switching, n = 7)

Longitudinal studies that evaluated biosimilar-to-oIFX, biosimilar-to-biosimilar, or multiple switching are summarized in Table S4 [Citation34,Citation35,Citation40,Citation43,Citation47,Citation59–65,Citation75,Citation94,Citation97,Citation117]. Two longitudinal studies of patients with IBD who underwent biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching (CT-P13 → SB2 [Citation34] or CT-P13 → GP1111 [Citation64]) or multiple switching reported no detectable effect of switching on Fc concentrations (Table S2).

Six studies in patients with IBD who underwent biosimilar-to-biosimilar or multiple switching reported similar CRP concentrations between groups after switching (Table S3) [Citation34,Citation59,Citation60,Citation62–64,Citation94,Citation117]. A study by Hanzel et al. (2021) [Citation34], in patients with IBD who underwent biosimilar-to-biosimilar (n = 80) or multiple switching (n = 69) showed significant declines (p = 0.038) in CRP concentrations (mg/L), but no significant increase (p = 0.582) in the percentage of patients with CRP <5 mg/L at 12 months [Citation34]. A retrospective observational study by Khan et al. (2021) reported that in patients (n = 271) switching from oIFX to SB2 (single or double) 19.2% (n = 52) did not achieve remission at 12 months after switching [Citation43]. Furthermore, compared with a single switch, double switching was not associated with worse outcomes [Citation43]. Another prospective study (Lovero et al., 2021) reported no change in clinical remission rate from 6 months before to 3 months after switching (58% at both time-points) from CT-P13 to SB2 in patients with IBD (n = 36); the rate of mild activity varied from 28% to 33% (p = 0.68) [Citation62]. Mazza et al. (2021) (n = 52) also observed no difference in clinical remission or loss of clinical response after 5.5 months between single-switch (oIFX → CT-P13) and double-switch (oIFX → CT-P13 → SB2) cohorts [Citation61,Citation97].

3.5. Safety and immunogenicity outcomes: IFX originator-to-biosimilar

3.5.1. Randomized controlled studies (n = 2)

Two RCTs reported numbers and frequencies of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) among patients with IBD () [Citation55,Citation66–68]. In the PLANET-CD study, 21/55 (38%) patients with CD who switched from oIFX to CT-P13 experienced TEAEs after switching, while 14/54 (26%) patients who continued oIFX experienced TEAEs [Citation55]. The greatest number of TEAEs experienced by the highest percentage of patients with CD was observed in the NOR-SWITCH study: 130 AEs were reported in 57/77 (74%) patients after 52 weeks among patients who switched from oIFX to biosimilar at randomization, whereas 18/62 (29%) patients who switched at the start of the OLE experienced AEs during the 26-week extension [Citation68]. CT-P13 maintenance was associated with 42 TEAEs among 24/65 (37%) patients during the OLE [Citation66–68]. Among patients with UC, 65 events were reported in 29/46 (63%) patients who switched from oIFX to CT-P13 at randomization during the 52-week main NOR-SWITCH study and 20 events in 14/38 (37%) patients who switched to CT-P13 at the start of the 26-week OLE, corresponding to non-inferiority of biosimilar over oIFX in the extension phase [Citation67].

Table 3. Summary of TEAEs in RCTs, and overall AEs and SAEs in longitudinal studies in patients with IBD switching from IFX originator (oIFX) to biosimilar.

3.5.2. Longitudinal studies (n = 60)

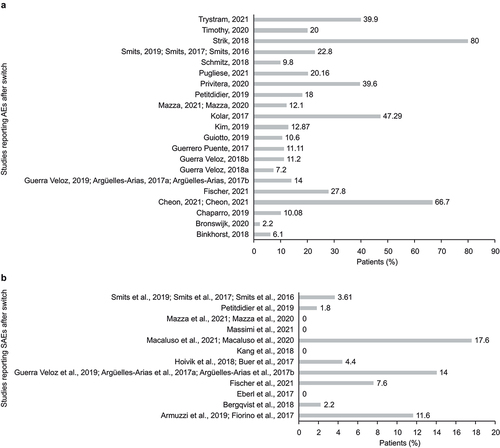

AEs were reported in 29 longitudinal studies of patients with IBD who switched from oIFX to biosimilars, ranging from 3.7 to 60 months’ duration () [Citation32,Citation36–39,Citation49–51,Citation56,Citation57,Citation59,Citation61,Citation79–83,Citation86,Citation87,Citation89,Citation92,Citation96,Citation97,Citation99,Citation102–104,Citation107,Citation108,Citation110,Citation111,Citation114]. Nine [Citation49,Citation71,Citation72,Citation76,Citation80,Citation87,Citation89,Citation103,Citation105,Citation106,Citation118] and five [Citation49,Citation76,Citation80,Citation89,Citation106] longitudinal studies reported overall AEs for patients with CD and UC, respectively (). Eleven longitudinal studies reported the proportions of patients with IBD who experienced overall AEs ().

Figure 3. Percentage of patients with (a) AEs and (b) SAEs in patients with IBD after switching from oIFX to biosimilar in longitudinal studies.

In a retrospective study by Chaparro et al. (2019) that included 48 (10.8%) patients who experienced a total of 61 AEs during follow-up, the incidence of AEs was 6% versus 13% in switch versus non-switch cohort (p<0.05) [Citation81]. A prospective study by Strik et al. (2018) found that 94/118 (80%) patients with IBD experienced ≥1 AE after switching to CT-P13 after ≥30 weeks of continuous treatment with oIFX [Citation106].

Serious AEs (SAEs) after switching to biosimilars were reported in 12 longitudinal studies [Citation35,Citation40,Citation60,Citation69,Citation70,Citation73,Citation74,Citation76,Citation80,Citation83,Citation86,Citation89,Citation94,Citation99,Citation106,Citation107,Citation114] of patients with IBD (); three studies [Citation76,Citation106,Citation115] each reported separate results for SAEs among patients with CD or UC (). A prospective study (Fischer et al., 2021) of patients with IBD (n = 144) who switched from oIFX to SB2 reported 11 SAEs in 40 patients (four malignancies, five intestinal surgical procedures, one liver abscess and one bronchopulmonary infection) [Citation83]. Another prospective study (Macaluso et al., 2021) reported three SAEs in 3/17 (17.6%) patients who switched from oIFX to SB2, representing an incidence rate of 18.9 per 100 patient-years’ exposure [Citation60]. A multinational prospective study (Strik et al., 2018) reported ≥ 1 SAE in 6/118 (5%) patients with IBD (CD: 3/60 [5%]; UC: 3/58 [5%]) who switched from oIFX to CT-P13 after 16 weeks of follow-up [Citation106]. Two observational studies of patients with IBD who switched from oIFX to CT-P13 reported SAEs in 4/195 (2.1%) [Citation76] and 1/67 (1.5%) [Citation115] patients with CD, and in 3/118 (2.5%) [Citation76] and 1/31 (3.2%) [Citation115] patients with UC, respectively, after 12 months of follow-up.

Across studies, there were no relevant changes observed in the profile of AEs, SAEs and TEAEs after switching, with moderate numbers of patients reporting certain specific AEs. No treatment-related AEs of grade 4 or higher, malignancies or deaths were reported in any group. The rates of AEs following switching to biosimilar were consistent with the known AE profile of IFX across most studies. However, one study conducted in US veterans showed that patients who switched from oIFX to biosimilar IFX were more likely to discontinue treatment and switch to another originator biologic (468/610 [76.6%]) than patients who remained on oIFX (118/617; 19.2%) [Citation93]. Among the biosimilar recipients, most switched back to oIFX (426/468 [91.0%]). The reasons for discontinuation and switching were unknown.

Only one study (Boone et al., 2018) reported nocebo effects upon switching from oIFX to biosimilars in an IBD population [Citation33]. In that study, nocebo-effect responses, defined as an unexplained unfavorable therapeutic effect subsequent to a non-medical switch from oIFX to biosimilar IFX, with regaining of the beneficial effects after re-initiating oIFX, were reported in 13/101 (12.9%) patients with IBD. Patient education strategies to inform shared decision-making and patient empowerment will likely be needed to lessen the nocebo effect.

3.6. Safety and immunogenicity outcomes: IFX biosimilar-to-originator, biosimilar-to-biosimilar, biosimilar maintenance, or multiple switching

3.6.1. Randomized controlled studies (n = 2)

In the PLANET-CD study, one patient with CD who remained on CT-P13 at week 30 and reverse switched from CT-P13 to oIFX reported SAEs [Citation55]. In the NOR-SWITCH RCT, seven SAEs were reported in six (9%) patients with CD on CT-P13 maintenance [Citation66–68].

3.6.2. Longitudinal studies (n = 3)

Three longitudinal studies of patients with IBD [Citation34,Citation61,Citation62,Citation97], assessed overall AE profiles following biosimilar-to-biosimilar [Citation34] or multiple switching [Citation34,Citation61,Citation97]. One prospective observational study (Hanzel et al. 2021) reported eight (10%) and two (3%) patients who developed AEs after switching from CT-P13 to SB2 (n = 80) or multiple switching (n = 69), respectively [Citation34]. Mazza et al. (2022) reported five TEAEs (all grade ≤ 3; no IRs) in 4/52 double-switched (oIFX → CT-P13 → SB2) patients with IBD after 24 weeks of follow-up, and no differences in safety outcomes compared with a single-switch group of 66 patients with IBD [Citation61].

Only one longitudinal study, reported in two publications (Macaluso et al. 2020 and 2021) [Citation60,Citation94], evaluated SAEs after biosimilar-to-biosimilar (CT-P13 → SB2) or multiple (oIFX → CT-P13 → SB2) switching. Authors reported 11 SAEs in 11/43 (25.6%) patients after 28 patient-months follow-up, and four SAEs in 4/24 (16.7%) patients in the multiple-switch group (oIFX → CT-P13 → SB2) after 16 patient-months follow-up in the biosimilar-to-biosimilar and multiple-switch groups, respectively [Citation60,Citation94].

3.7. Feasibility assessment

83 publications (63 full-text publications and 20 conference abstracts) were considered for qualitative feasibility assessment (see Supplementary file 4 for full details of the feasibility analysis).

4. Discussion

Assessment of the effects of switching between IFX products and multiple switching on safety and effectiveness outcomes can enable HCPs to develop a wider understanding of these therapies when considering switching in patients with IBD.

Of the 85 studies included in this systematic literature review, 65 were longitudinal observational studies; only two were RCTs (one multinational, one conducted in Norway). For most of the identified studies, the clinical, patient-reported and safety outcomes in patients with IBD switching from originator to biosimilar were highly similar to the originator responses, and outcomes following switching were consistent with the known profile of oIFX [Citation32,Citation39,Citation42,Citation55,Citation58,Citation60,Citation75,Citation76,Citation82,Citation88,Citation102]. Of particular note, four studies, including one RCT, reported mucosal healing in patients with CD after switching from oIFX to biosimilar [Citation45,Citation46,Citation55,Citation69–72], and the RCT also identified mucosal healing in patients after reverse switching from IFX biosimilar to oIFX [Citation55]. Interpretation of these findings is difficult because mucosal healing is time-dependent and the conversion of patients from active inflammation to healing status may be reflective of sustained drug exposure, rather than resulting from differences in agent. Across the studies, switching to biosimilar did not have a significant impact on the rates of AEs, SAEs or TEAEs or the proportion of patients with detectable ADAs. In general, switching to biosimilars was associated with stability in AEs, corresponding to non-inferiority of IFX biosimilars over oIFX among patients with IBD. In two studies (NOR-SWITCH and PLANET-CD), the percentage of TEAEs was higher in patients who switched from originator to biosimilar than in patients who continued with originator. However, this difference may be numerical (e.g. higher percentage of AEs in the oIFX group before switching, or higher rate of reporting AEs, both maintained following switching) rather than related to safety signals. Originator-to-biosimilar switching did not increase the percentage of patients with detectable levels of ADAs or increase the rate of discontinuation due to AEs. It is not certain whether therapeutic drug monitoring lessens immunogenicity when switching agents. Additionally, it is not known if the use of concurrent immunomodulators is needed to lessen immunogenicity prior to switching. This strategy may be appropriate in patients undergoing multiple switches.

A few longitudinal studies evaluated multiple switches. In these studies, comparison between single- and multiple-switch cohorts revealed non-inferiority of multiple switches over single switch [Citation61,Citation97]. Only one study demonstrated a significant improvement in clinical remission among a single-switch cohort versus multiple-switch and biosimilar-switch cohorts [Citation60,Citation94].

Of the 85 IBD studies included in this systematic literature review, only two RCTs, PLANET-CD [Citation55] and NOR-SWITCH [Citation66–68], assessed the efficacy and safety of IFX biosimilars. Additional well-designed RCTs with clearly defined follow-up periods and outcomes would be useful to provide conclusive evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of biosimilars in this population. In addition, detailed information about the type of endoscopy used is limited, and few studies have reported on hypersensitivity, mucosal healing and fistula closure outcomes in patients with IBD. Only a small number of studies have reported results from multiple switching (n = 5), biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching (n = 6), and reverse switching (n = 4) at this time. Therefore, a comparative analysis of all switching patterns was not possible. While outside the scope of this systematic literature review, RCTs of multiple switching between originator and biosimilar adalimumab have been conducted in patients with psoriasis [Citation119–121] and rheumatoid arthritis [Citation122, Citation123]. In those studies, multiple switches between reference and biosimilar did not negatively affect pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, effectiveness, or safety [Citation119,Citation120]. Finally, the follow-up duration for the studies included in this systematic literature review ranged from 3 months to 3 years for most studies, with only three studies reporting a longer follow-up duration (of 5 years). Additional studies with longer follow-up duration may be helpful in guiding decisions regarding maintenance therapy.

The key strength of this review is its use of a standardized, thorough, and transparent approach to identify and appraise the included studies. This review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines and included a comprehensive literature search in addition to independent selection and quality assessment of the included studies by two researchers. Limitations of this review include those inherent in any systematic review of the published literature, including the potential for missing relevant studies not identified in the systematic literature database searches, studies not published in English or studies published after the date the searches were conducted (4 April 2022). The inherent heterogeneity in study populations, evaluation methods, length of follow-up and outcomes assessed is important to consider when interpreting the findings.

5. Conclusions

This update improves understanding of the safety and effectiveness of biosimilars based on recent publications, which is important to inform the optimal treatment of patients with IBD switching from oIFX to IFX biosimilar for financial or other reasons. This updated systematic review builds on a prior (2019) review of IFX switching in patients with various inflammatory disorders [Citation27]. Notably, this update includes more robust data that have been published in the interim, including the PLANET-CD study and additional analyses from the NOR-SWITCH study [Citation55,Citation66,Citation67]. By performing this systematic review we have identified important areas of interest that have not yet been adequately evaluated.

Evidence from the recent literature, particularly a number of longitudinal real-world studies, indicates that switching from oIFX to biosimilars is associated with similar effectiveness, safety and tolerability. Thus, results continue to support IFX biosimilar use as an alternative to originator for patients with IBD. Over the long term, switching from originator to biosimilars did not impact PROs, quality of life, or immune response in patients with IBD.

Despite the wealth of recent data on biosimilar use in patients with IBD, our systematic literature review highlights some evidence gaps. In particular, high-quality RCTs with longer follow-up periods and clearly defined clinical outcomes using formal reporting procedures for endoscopy outcomes, including mucosal healing and fistula closure, are lacking.

Article highlights

Despite the growing availability of biosimilars and increasing data on their highly similar clinical profiles (to their respective originators), many healthcare providers still remain skeptical regarding the safety of using biosimilars instead of the originator in bio-naïve patients, as well as switching patients from an originator to a biosimilar.

A number of longitudinal real-world data indicates that switching from originator IFX to biosimilars is associated with similar effectiveness, safety, and tolerability which continues to support IFX biosimilar use as an alternative to originator for patients with IBD.

Over the long term, switching from originator to biosimilar IFX had no observed impact on patient-reported outcomes, quality of life or immune response in patients with IBD.

There is a lack of high-quality randomized controlled trials evaluating biosimilar use in patients with IBD with longer follow-up periods and clearly defined clinical outcomes using formal reporting procedures for endoscopy outcomes, including mucosal healing and fistula closure.

Declaration of interest

GR Lichtenstein has acted as a consultant for AbbVie, American Regent, Cellgene/Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Endo International, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi (Health and Wellness Partners), Gilead, Janssen (now Johnson & Johnson), MedEd Consultants, Pharmacosmos, Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories, Sandoz, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and UCB. Performed CME supported by AbbVie, Allergan, American Gastroenterological Association, American Regent, Annenberg Center for Health Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Exact Sciences, Ferring, IBD Horizons, Ironwood, Janssen (now Johnson & Johnson), MedEd Consultants, Pennsylvania Society of Gastroenterology, Sanofi, Salix, Seres Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, Vindico. Other finances received: Eli Lilly for DSMB (Honorarium for Data Safety Monitoring Board), Gastro-Hep Communications (Honorarium for executive editor), Janssen Orthobiotech (Finances to Fund GI IBD Fellowship), Pfizer (Finances to Fund GI IBD Fellowship), Professional Communications, Inc- textbook royalty, Springer Science and Business Media- Editor (Honorarium), Up To Date- Walters Kluwer- Author (Honorarium). Research: Takeda, UCB, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen (now Johnson & Johnson). BG Feagan has acted as a consultant for AbbVie, AbolerIS Pharma, Agomab Therapeutics, AllianThera Biopharma, Amgen, AnaptysBio, Applied Molecular Transport Inc, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Avoro Capital Advisors, Atomwise, BioJamp, Biora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boxer Capital, Celsius Therapeutics, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb, Connect Biopharma, Cytoki Pharma, Disc Medicine, Duality Biologics, EcoR1, Eli Lilly, Equillium, Ermium Therapeutics, First Wave BioPharma, FirstWord Pharma, Galapagos NV, GalenAtlantica, Genentech/Roche, Gilead Sciences, Gossamer Bio, GSK, Hinge Bio, HotSpot Therapeutics, InDex Pharmaceuticals, Imhotex, Immunic Therapeutics, JAKAcademy, Janssen (now Johnson & Johnson), Japan Tobacco Inc., Kaleido Biosciences, Landos Biopharma, Leadiant Biosciences, L.E.K. Consulting, Lenczner Slaght, LifeSci Capital, Lument AB, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, MiroBio, Morgan Lewis, Morphic Therapeutic, Mylan, OM Pharma, Origo BioPharma, Orphagen Pharmaceuticals, Pandion Therapeutics, Pendopharm, Pfizer, Prometheus Therapeutics and Diagnostics, Play to Know AG, Progenity Pharmaceuticals/Biora Therapeutics, Protagonist Therapeutics, PTM Therapeutics, Q32 Bio, Rebiotix, REDX Pharma, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi, Seres Therapeutics, Surrozen, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Thelium Therapeutics, TiGenix, Tillotts Pharma UK, Ventyx Biosciences, VHSquared Ltd., Viatris, Ysios Capital, Ysopia Bioscience, and Zealand Pharma. Speaker for AbbVie, Janssen, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. S Singh is an employee of Curo, a division of the Envision Pharma Group, which was a paid consultant to Pfizer in connection with the development of this manuscript. A Soonasra and M Latymer are employees of Pfizer and hold stock or stock options in Pfizer. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (154.9 KB)Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Sharmila Blows, PhD, of Envision Pharma Group and was funded by Pfizer. The authors thank Karen Smoyer, PhD, of Curo, a division of the Envision Pharma Group, for contributing to the study design, analyzing the data, and organizational contributions to this work, which was funded by Pfizer.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or as supplementary information files.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2024.2378090

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cui G, Fan Q, Li Z, et al. Evaluation of anti-TNF therapeutic response in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: current and novel biomarkers. EBioMedicine. 2021 Apr;66:103329. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103329

- Baumgart DC, Misery L, Naeyaert S, et al. Biological therapies in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: can biosimilars reduce access inequities? Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:279. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00279

- Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies. REMICADE® (infliximab). Prescribing information. Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies; 2021. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/103772s5359lbl.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. Biosimilar product information 2021 [ updated 2021 Sept 20; cited 2021 Oct 11]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-product-information

- Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. FDA approves infliximab biosimilar inflectra. GaBi Online; 2016 [cited 2022 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/news/FDA-approves-infliximab-biosimilar-Inflectra

- European Medicines Agency. Remsima: EPAR. Product information. European Medicines Agency; 2013 [cited 2023 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/remsima

- Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. FDA approves biosimilar infliximab Renflexis. GaBi Online; 2017 [ updated 2017 May 05;cited 2022 Sep 23]. updated 2017 May 05 https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/news/FDA-approves-biosimilar-infliximab-Renflexis

- European Medicines Agency. Flixabi: EPAR. product information. European Medicines Agency; 2016. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/flixabi

- Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. FDA approves biosimilar infliximab Ixifi. GaBi Online; 2018. Available from: https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/news/FDA-approves-biosimilar-infliximab-Ixifi

- European Medicines Agency. Zessly: EPAR. product information. European Medicines Agency; 2018 [cited 2023 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zessly

- Haifer C, Srinivasan A, An YK, et al. Switching Australian patients with moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease from originator to biosimilar infliximab: a multicentre, parallel cohort study. Med J Aust. 2021 Feb;214(3):128–133. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50824

- US Food and Drug Administration. Biosimilar development, review, and approval 2017 [ updated 2017 Oct 20;cited 2022 Sep 23]. updated 2017 Oct 20 https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-development-review-and-approval

- Troein P, Newton M, Scott K, et al. The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe. IQVIA white paper. 2021. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/the-impact-of-biosimilar-competition-in-europe-2021.pdf

- Aladul MI, Fitzpatrick RW, Chapman SR. Impact of infliximab and etanercept biosimilars on biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs utilisation and NHS budget in the UK. BioDrugs. 2017 Dec;31(6):533–544. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0252-3

- Chen AJ, Ribero R, Van Nuys K. Provider differences in biosimilar uptake in the filgrastim market. Am J Manag Care. 2020 May;26(5):208–213.

- Edgar BS, Cheifetz AS, Helfgott SM, et al. Overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption: real-world perspectives from a national payer and provider initiative. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021 Aug;27(8):1129–1135. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2021.27.8.1129

- Oskouei ST, Kusmierczyk AR. Biosimilar uptake: the importance of healthcare provider education. Pharmaceut Med. 2021 Jul;35(4):215–224. doi: 10.1007/s40290-021-00396-7

- Baer Ii WH, Maini A, Jacobs I. Barriers to the access and use of rituximab in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a physician survey. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2014 May 7;7(5):530–544. doi: 10.3390/ph7050530

- Lammers P, Criscitiello C, Curigliano G, et al. Barriers to the use of trastuzumab for HER2+ breast cancer and the potential impact of biosimilars: a physician survey in the United States and emerging markets. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2014 Sep 17;7(9):943–953. doi: 10.3390/ph7090943

- Socinski MA, Curigliano G, Jacobs I, et al. Clinical considerations for the development of biosimilars in oncology. MAbs. 2015;7(2):286–293. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1008346

- Cherny N, Sullivan R, Torode J, et al. ESMO European consortium study on the availability, out-of-pocket costs and accessibility of antineoplastic medicines in Europe. Ann Oncol. 2016 Aug;27(8):1423–1443. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw213

- Monk BJ, Lammers PE, Cartwright T, et al. Barriers to the access of bevacizumab in patients with solid tumors and the potential impact of biosimilars: a physician survey. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2017 Jan 28;10(1):19. doi: 10.3390/ph10010019

- Lepelaars LRA, Renda F, Pani L, et al. Comparing safety information of biosimilars with their originators: a cross-sectional analysis of European risk management plans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018 Apr;84(4):738–763. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13454

- Patel PK, King CR, Feldman SR. Biologics and biosimilars. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(4):299–302. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1054782

- Leonard E, Wascovich M, Oskouei S, et al. Factors affecting health care provider knowledge and acceptance of biosimilar medicines: a systematic review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019 Jan;25(1):102–112. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.1.102

- Halimi V, Daci A, Ancevska Netkovska K, et al. Clinical and regulatory concerns of biosimilars: a review of literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Aug 11;17(16):5800. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165800

- Feagan BG, Lam G, Ma C, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of switching patients between reference and biosimilar infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019 Jan;49(1):31–40. doi: 10.1111/apt.14997

- Mysler E, Azevedo VF, Danese S, et al. Biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching: what is the rationale and current experience? Drugs. 2021 Nov;81(16):1859–1879. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01610-1

- Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019 Aug 28;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

- Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Oxford; 2000 [cited 2023 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Study quality assessment tools 2021 [ updated 2023 January 17;cited 2023 Mar 28]. updated 2023 January 17 https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- Binkhorst L, Sobels A, Stuyt R, et al. Short article: switching to a infliximab biosimilar: short-term results of clinical monitoring in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jul;30(7):699–703. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001113

- Boone NW, Liu L, Romberg-Camps MJ, et al. The nocebo effect challenges the non-medical infliximab switch in practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018 May;74(5):655–661. doi: 10.1007/s00228-018-2418-4

- Hanzel J, Jansen JM, Ter Steege RWF, et al. Multiple switches from the originator infliximab to biosimilars is effective and safe in inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 May 20;28(4):495–501. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab099

- Mahmmod S, Schultheiss JPD, van Bodegraven AA, et al. Outcome of reverse switching from CT-P13 to originator infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 Nov 15;27(12):1954–1962. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izaa364

- Schmitz EMH, Boekema PJ, Straathof JWA, et al. Switching from infliximab innovator to biosimilar in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month multicentre observational prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Feb;47(3):356–363. doi: 10.1111/apt.14453

- Smits LJ, Derikx LA, de Jong DJ, et al. Clinical outcomes following a switch from Remicade® to the biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a prospective observational cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2016 Nov;10(11):1287–1293. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw087

- Smits LJT, Grelack A, Derikx L, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes after switching from Remicade® to biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017 Nov;62(11):3117–3122. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4661-4

- Smits LJT, van Esch AAJ, Derikx L, et al. Drug survival and immunogenicity after switching from Remicade to biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease patients: two-year follow-up of a prospective observational cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Jan 1;25(1):172–179. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy227

- Mahmmod S, Schultheiss JPD, Tan T, et al. P326 reasons for and effectiveness of switching back to originator infliximab after a prior switch to CT-P13 biosimilar. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(Suppl 1):S316–S317. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz203.455

- Bhat S, Altajar S, Shankar D, et al. Process and clinical outcomes of a biosimilar adoption program with infliximab-Dyyb. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020 Apr;26(4):410–416. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2020.26.4.410

- Ho SL, Niu F, Pola S, et al. Effectiveness of switching from reference product infliximab to infliximab-dyyb in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in an integrated healthcare system in the United States: a retrospective, propensity score-matched, non-inferiority cohort study. BioDrugs. 2020 Jun;34(3):395–404. doi: 10.1007/s40259-020-00409-y

- Khan N, Patel D, Pernes T, et al. The efficacy and safety of switching from originator infliximab to single or double switch biosimilar among a nationwide cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Crohns Colitis 360. 2021;3(2):otab022. doi: 10.1093/crocol/otab022

- Mehta SA, Ritter TE, Fernandes CC, et al. S837 payor-mandated non-medical switching from infliximab to biosimilar creates dosing delays. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(1):S388. doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000776880.16345.04

- Padival R, Qayyum F, Lee JA, et al. Fr525 biosimilar switch in a large quaternary care American medical institution does not result in worsening of inflammatory bowel disease activity. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):S346–7. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(21)01546-8

- Padival R, Heis F, Lee JA, et al. S0820 real world comparison of bio-originator infliximab vs the biosimilar infliximab-abda in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(1):S421–S422. doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000705328.61690.cb

- Pernes T, Patel M, Khan N. S0792 the safety of switching from originator infliximab or biosimilar CT-P13 to SB2 among a nationwide cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(1):S405. doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000705216.13543.4d

- Yoo T, Zhornitskiy A, Fung B, et al. S0858 assessing the efficacy and safety of a transition from infliximab to infliximab biosimilar in the management of IBD in a safety net population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Oct 01;115:S443. doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000705480.65270.c6

- Kim NH, Lee JH, Hong SN, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of CT-P13, a biosimilar of infliximab, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective multicenter study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep;34(9):1523–1532. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14645

- Nakagawa T, Kobayashi T, Nishikawa K, et al. Infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 is interchangeable with its originator for patients with inflammatory bowel disease in real world practice. Intest Res. 2019 Oct;17(4):504–515. doi: 10.5217/ir.2019.00030

- Kang B, Lee Y, Lee K, et al. Long-term outcomes after switching to CT-P13 in pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a single-center prospective observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018 Feb 15;24(3):607–616. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx047

- Kang YS, Moon HH, Lee SE, et al. Clinical experience of the use of CT-P13, a biosimilar to infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a case series. Dig Dis Sci. 2015 Apr;60(4):951–956. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3392-z

- Park SH, Kim YH, Lee JH, et al. Post-marketing study of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) to evaluate its safety and efficacy in Korea. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9(Suppl 1):35–44. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1091309

- Jung YS, Park DI, Kim YH, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13, a biosimilar of infliximab, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective multicenter study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Dec;30(12):1705–1712. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12997

- Ye BD, Pesegova M, Alexeeva O, et al. Efficacy and safety of biosimilar CT-P13 compared with originator infliximab in patients with active Crohn’s disease: an international, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 non-inferiority study. Lancet. 2019 Apr 27;393(10182):1699–1707. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32196-2

- Cheon J, Kang H, Lee S, et al. P358 an observational, prospective cohort study to evaluate the long term safety and effectiveness of intravenous CT-P13 (biosimilar of infliximab) in patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 May 27;15(Supplement_1):S378–S379. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab076.482

- Cheon JH, Nah S, Kang HW, et al. Infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 observational studies for rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, and ankylosing spondylitis: pooled analysis of long-term safety and effectiveness. Adv Ther. 2021 Aug;38(8):4366–4387. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01834-3

- Abraham B, Eksteen B, Nedd K, et al. Impact of infliximab-dyyb (infliximab biosimilar) on clinical and patient-reported outcomes: 1-year follow-up results from an observational real-world study among patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the US and Canada (the ONWARD study). Adv Ther. 2022 May;39(5):2109–2127. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02104-6

- Trystram N, Abitbol V, Tannoury J, et al. Outcomes after double switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 and biosimilar SB2 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Apr;53(8):887–899. doi: 10.1111/apt.16312

- Macaluso FS, Fries W, Viola A, et al. The SPOSIB SB2 Sicilian cohort: safety and effectiveness of infliximab biosimilar SB2 in inflammatory bowel diseases, including multiple switches. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 Jan 19;27(2):182–189. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izaa036

- Mazza S, Piazza O, Sed N, et al. Safety and clinical efficacy of the double switch from originator infliximab to biosimilars CT-P13 and SB2 in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (SCESICS): a multicenter cohort study. Clin Transl Sci. 2022 Jan;15(1):172–181. doi: 10.1111/cts.13131

- Lovero R, Losurdo G, La Fortezza RF, et al. Safety and efficacy of switching from infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 to infliximab biosimilar SB2 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Feb 1;32(2):201–207. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001988

- Luber RP, O’Neill R, Singh S, et al. An observational study of switching infliximab biosimilar: no adverse impact on inflammatory bowel disease control or drug levels with first or second switch. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Sep;54(5):678–688. doi: 10.1111/apt.16497

- Siakavellas SI, Barrett RA, Plevris N, et al. 610 both single and multiple switching between infliximab biosimilars can be safe and effective in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): real world outcomes from the Edinburgh IBD unit. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):S120. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(21)01042-8

- Ilias A, Szanto K, Gonczi L, et al. Outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases switched from maintenance therapy with a biosimilar to remicade. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Nov;17(12):2506–2513. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.036

- Goll GL, Jørgensen KK, Sexton J, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) after switching from originator infliximab: open-label extension of the NOR-SWITCH trial. J Intern Med. 2019 Jun;285(6):653–669. doi: 10.1111/joim.12880

- Jørgensen KK, Goll GL, Sexton J, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease after switching from originator infliximab: exploratory analyses from the NOR-SWITCH main and extension trials. BioDrugs. 2020 Oct;34(5):681–694. doi: 10.1007/s40259-020-00438-7

- Jørgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet. 2017 Jun 10;389(10086):2304–2316. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30068-5

- Armuzzi A, Fiorino G, Variola A, et al. The PROSIT cohort of infliximab biosimilar in IBD: a prolonged follow-up on the effectiveness and safety across Italy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Feb 21;25(3):568–579. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy264

- Fiorino G, Manetti N, Armuzzi A, et al. The PROSIT-BIO cohort: a prospective observational study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab biosimilar. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Feb;23(2):233–243. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000995

- Tursi A, Allegretta L, Chiri S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 in treating ulcerative colitis: a real-life experience in IBD primary centers. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2017 Dec;63(4):313–318. doi: 10.23736/S1121-421X.17.02402-3

- Tursi A, Mocci G, Faggiani R, et al. Infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 is effective and safe in treating inflammatory bowel diseases: a real-life multicenter, observational study in Italian primary inflammatory bowel disease centers. Ann Gastroenterol. 2019 Jul;32(4):392–399. doi: 10.20524/aog.2019.0377

- Argüelles-Arias F, Guerra Veloz MF, Perea Amarillo R, et al. Switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: 12 months results. Eur J Gastroenterol & Hepatol. 2017;29(11):1290–1295. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000953

- Argüelles-Arias F, Guerra Veloz MF, Perea Amarillo R, et al. Effectiveness and safety of CT-P13 (biosimilar infliximab) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in real life at 6 months. Dig Dis Sci. 2017 May 01;62(5):1305–1312. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4511-4

- Avouac J, Moltó A, Abitbol V, et al. Systematic switch from innovator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory chronic diseases in daily clinical practice: the experience of Cochin University Hospital, Paris, France. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Apr;47(5):741–748. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.10.002

- Bergqvist V, Kadivar M, Molin D, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to the biosimilar CT-P13 in 313 patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756284818801244. doi: 10.1177/1756284818801244

- Bouhnik Y, Fautrel B, Desjeux G, et al. PERFUSE: a French non-interventional cohort study of infliximab-naive and transitioned patients receiving infliximab biosimilar SB2; an interim analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(Suppl 1):S529. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz203.765

- Bouhnik Y, Fautrel B, Beaugerie L, et al. PERFUSE: a French non-interventional study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving infliximab biosimilar SB2: a 12-month analysis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848221145654. doi: 10.1177/17562848221145654

- Bronswijk M, Moens A, Lenfant M, et al. Evaluating efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics after switching from infliximab originator to biosimilar CT-P13: experience from a large tertiary referral center. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020 Mar 4;26(4):628–634. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz167

- Buer LC, Moum BA, Cvancarova M, et al. Switching from Remicade(R) to Remsima(R) is well tolerated and feasible: a prospective, open-label study. J Crohns Colitis. 2017 Mar 1;11(3):297–304. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw166

- Chaparro M, Garre A, Guerra Veloz MF, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the switch from Remicade® to CT-P13 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019 Oct 28;13(11):1380–1386. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz070

- Eberl A, Huoponen S, Pahikkala T, et al. Switching maintenance infliximab therapy to biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017 Dec;52(12):1348–1353. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2017.1369561

- Fischer S, Cohnen S, Klenske E, et al. Long-term effectiveness, safety and immunogenicity of the biosimilar SB2 in inflammatory bowel disease patients after switching from originator infliximab. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:1756284820982802. doi: 10.1177/1756284820982802

- Fischer S, Mesfin S, Klenske E, et al. P548 efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics after switching from infliximab originator to biosimilar SB2 in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a long-term observational, prospective cohort study. J Crohn’s And Colitis. 2020;14(Supplement_1):S466–S467. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz203.676

- Gervais L, McLean LL, Wilson ML, et al. Switching from originator to biosimilar infliximab in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease is feasible and uneventful. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018 Dec;67(6):745–748. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002091

- Guerra Veloz MF, Belvis Jiménez M, Valdes Delgado T, et al. Long-term follow up after switching from original infliximab to an infliximab biosimilar: real-world data. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819858052. doi: 10.1177/1756284819858052

- Guerrero Puente L, Iglesias Flores E, Benitez JM, et al. Evolution after switching to biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease patients in clinical remission. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Nov;40(9):595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2017.07.005

- Hlavaty T, Krajcovicova A, Sturdik I, et al. Biosimilar infliximab CT-P13 treatment in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases – a one-year, single-centre retrospective study. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;70(1):27–36. doi: 10.14735/amgh201627

- Hoivik ML, Buer LCT, Cvancarova M, et al. Switching from originator to biosimilar infliximab - real world data of a prospective 18 months follow-up of a single-centre IBD population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018 Jun;53(6):692–699. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1463391

- Huguet JM, Cortés X, Bosca-Watts MM, et al. Real-world data on the infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 (Remsima(®)) in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Clin Cases. 2021 Dec 26;9(36):11285–11299. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11285

- Huoponen S, Eberl A, Räsänen P, et al. Health-related quality of life and costs of switching originator infliximab to biosimilar one in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Jan;99(2):e18723. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018723

- Kolar M, Duricova D, Bortlik M, et al. Infliximab biosimilar (remsima) in therapy of inflammatory bowel diseases patients: experience from one tertiary inflammatory bowel diseases centre. Dig Dis. 2017;35(1–2):91–100. doi: 10.1159/000453343

- Lin I, Melsheimer R, Bhak RH, et al. Impact of switching to infliximab biosimilars on treatment patterns among US veterans receiving innovator infliximab. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022 Apr;38(4):613–627. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2022.2037846

- Macaluso FS, Fries W, Viola A, et al. P425 SPOSIB SB2: a Sicilian prospective observational study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab biosimilar SB2. J Crohn's Colitis. 2020;14(Suppl 1):S387–S388. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz203.554

- Martín-Gutiérrez N, Sanchez-Hernandez JG, Rebollo N, et al. Long-term effectiveness and pharmacokinetics of the infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 after switching from the originator during the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2020 Oct 28;29(4):222–227. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2020-002410

- Massimi D, Barberio B, Bertani L, et al. Switching from infliximab originator to SB2 biosimilar in inflammatory bowel diseases: a multicentric prospective real-life study. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan 01;14:17562848211023384. doi: 10.1177/17562848211023384

- Mazza S, Fasci A, Casini V, et al. Mo1872 safety and clinical efficacy of double switch from originator infliximab to biosimilars CT-P13 and SB2 in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (SCESICS): a multicentre study. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S957. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(20)33071-7

- Nascimento C, Revés J, Morão B, et al. P555 outcomes of multiswitching from original infliximab to biosimilars in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn’s And Colitis. 2021;15(Supplement_1):S520–S521. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab076.676

- Petitdidier N, Tannoury J, De’angelis N, et al. Patients’ perspectives after switching from infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month prospective cohort study. Dig Liver Dis. 2019 Dec;51(12):1652–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2019.08.020

- Plevris N, Jones GR, Jenkinson PW, et al. Implementation of CT-P13 via a managed switch programme in Crohn’s disease: 12-month real-world outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2019 Jun;64(6):1660–1667. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5406-8

- Privitera G, Pugliese D, Tolusso B, et al. Sa1877 effectiveness, safety and immunogenicity of switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) in a large cohort of IBD patients. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S462. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(20)31836-9

- Pugliese D, Guidi L, Privitera G, et al. Switching from IFX originator to biosimilar CT-P13 does not impact effectiveness, safety and immunogenicity in a large cohort of IBD patients. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2021 Jan;21(1):97–104. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2020.1839045

- Ratnakumaran R, To N, Gracie DJ, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of initiating, or switching to, infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a large single-centre experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018 Jun;53(6):700–707. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1464203

- Razanskaite V, Bettey M, Downey L, et al. Biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: outcomes of a managed switching programme. J Crohns Colitis. 2017 Jun 1;11(6):690–696. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw216

- Sieczkowska J, Jarzebicka D, Banaszkiewicz A, et al. Switching between infliximab originator and biosimilar in paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Preliminary observations. J Crohns Colitis. 2016 Feb;10(2):127–132. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv233