ABSTRACT

A growing number of city governments worldwide engage in sustainability reporting, voluntarily and responding to legal pressures. Diverse practices emerged based on unique choices concerning formats, periodicity, authorship and dissemination efforts. Such design questions and associated outcomes are highly relevant for practitioners yet unaddressed in standard guidelines and most prior research that primarily concern content and conjectured reporting benefits. This article presents a framework suited to assessing real-life practices and outcomes. An exploratory evaluation in Amsterdam, Basel, Dublin, Freiburg, Nuremberg and Zurich suggests that sustainability reporting can benefit organizational change, management and communication yet also lead to ‘fatigue’ and discontinuation.

Introduction

It’s great to have an absolutely rigorous reporting framework. The only problem is they’re useless unless somebody uses them.

– Civil servant, Dublin City Council (I.16)

Sustainability reporting is on the rise throughout the public sector. International frameworks such as the United Nations’ ‘Sustainable Development Goals’ (specifically SDG target 12.6) call for increased reporting by all types of institutions. In the European Union, a recent directive (2014/95/EU) requires all large ‘public interest entities’ to start disclosing ‘non-financial and diversity information.’ France recently mandated all municipalities with more than 50,000 inhabitants to periodically produce sustainability reports (CGDD Citation2012), and similar legislation is mooted elsewhere.

Proponents of reporting applaud this trend, with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) as the internationally most influential institution. Media coverage can be emphatic too: referring to the positive experience of Amsterdam and other cities, one news article claims that ‘a commitment to sustainability reporting is a vital step towards creating vibrant cities’ (Ballantine Citation2014, 4). According to their prefaces, sustainability reports generally serve ambitious objectives targeting multiple audiences. The mayor of the German city of Freiburg, for example, writes that ‘this sustainability report, presented to the municipal council and the public, serves in conjunctions with the municipal budget as an important management instrument for sustainable urban development’ (Freiburg Municipality Citation2014, 3). In analogy to ‘magic concepts’ such as accountability and governance that are popular in public management (Pollitt and Hupe Citation2011), sustainability reporting is thus often portrayed as a magic, ‘jack of all trades’ tool simultaneously fostering better policymaking and citizen engagement.

What is the evidence for reporting being an effective, multi-purpose, universally applicable way of promoting sustainability, both inside and outside of local governments? There are conjectural statements about various positive effects (e.g. Lamprinidi and Kubo Citation2008) but also warnings: in the private and public sector, some critics fear ‘accountingization’ where sustainability reports are merely ‘an outlet for “greenwashing” or a source of “managerialist” information’ (Dumay, Guthrie, and Farneti Citation2010, 543) that ‘may reinforce business-as-usual and greater levels of un-sustainability’ (Milne and Gray Citation2013, 13). In a less extreme scenario, reporting may lack or lose its benefits; as evident from this article, in some cities, sustainability reporting was started with enthusiasm but later stopped following what practitioners describe as ‘reporting fatigue.’

Surprisingly, academic literature shows little consideration for these real-world phenomena. Most studies explore why organizations decide to become reporters and what kind of information they typically ‘disclose,’ implicitly assuming that transparency and thus reporting is worth pursuing. In sustainability reporting research, few studies address processes, and too easily the question of ‘how’ gets a response in terms of a ‘why’ (Stubbs and Higgins Citation2014). Recognizing the need for reflection, this journal published in 2012 the assertion that ‘research which simply focuses on enhancing public sector reporting practices without a broader theoretical engagement in the social and organizational context of the public sector is likely to be misguided’ (Lodhia, Jacobs, and Park Citation2012, 645). Arguably, sustainability reporting risks ‘merely exacerbating the already overwhelming amount of disclosure provided without adding further insight’ (S. Adams and Simnett Citation2011, 294) if negative outcomes such as ‘information overload’ (de Villiers, Rinaldi, and Unerman Citation2014) remain ignored.

This article responds to calls for context-sensitive, process and outcome-oriented research by investigating the use of sustainability reporting by local governments from a longitudinal perspective. Building on evaluation research (Weiss, Murphy-Graham, and Birkeland Citation2005), we developed a framework designed to analyse different reporting practices and explored those developed by six pioneering cities in Europe since 2004. This study thus pursues the following overall research question: How have sustainability reporting practices evolved in pioneering European local governments, and what are their effects?

This article is organized as follows: section ‘Sustainability reporting by local governments’ contains a review of research on sustainability reporting by local governments. Section ‘A framework to study reporting practices and outcomes’ introduces a framework designed to assess the use of sustainability reporting by local governments. Section ‘Research method’ addresses research methods including case selection criteria. Section ‘Results from six cities’ presents the results of the comparative analysis of six cases studies. Section ‘Discussion and conclusion’ concludes with a discussion of the results and the formulation of hypotheses for future research.

Sustainability reporting by local governments

It has been observed that the concept of sustainability has ‘saturated the modern world’ whereas ‘sustainability practices for public services have been neglected by scholars and others as a subject of theoretical research and in-depth investigation’ (Guthrie, Ball, and Farneti Citation2010, 450). External reporting is one core feature – along with the performance measurement and accruals accounting – of many reform processes of the recent decades (Marcuccio and Steccolini Citation2009). The focus on reports has also been fuelled by increased attention (from policymakers and researchers) to accountability (Bovens Citation2005; Willems and Van Dooren. Citation2012). In fact, external reporting arrangements are likely to feature in any performance management or public accountability discussion (Downe et al. Citation2010).

Given the popularity of both sustainability and external reporting, it may come as no surprise that the conceptual joint venture of ‘sustainability reporting’ has become influential. In the public sector, however, the phenomenon is not easy to study. To begin with, the term sustainability reporting has two key meanings: (i) producing reports yet also (ii) disclosing information. This dual meaning stands at the root of two major lines of research with different conclusions: firstly, when assessing the prevalence of reports, a common observation is that ‘the uptake, forms and practice of sustainability reporting among public agencies is still in its infancy compared to the private sector’ (Lamprinidi and Kubo Citation2008, 328); when studying mere disclosure, scholars praise increasing compliance rates (Navarro Galera et al. Citation2014; Williams, Wilmshurst, and Clift Citation2011).

The search for disclosure – detecting the presence of desired indicators in institutional communications – has become the dominant research paradigm. A recent review of 178 studies concerning private and public-sector reporting classified 58 per cent as applying a form of document analysis (Hahn and Kühnen. Citation2013). Our review of the literature focusing on local governments produced a similar picture (see ).

Table 1. Recent studies concerning sustainability reporting by local governments.

In the private sector, sustainability reporting is often attributed to the objective of maintaining a ‘social licence to operate,’ and public-sector sustainability reporting research also refers to legitimacy-seeking behaviours. Various studies listed in affirm that local governments generally have institutional and political motives to adopt reporting practices, ‘mimicking managerial manners’ (Marcuccio and Steccolini Citation2005). Cities are keen to strengthen their credentials as being ‘green’ and ‘smart’ to gain a ‘competitive edge in the global knowledge economy’ (Yigitcanlar and Lönnqvist Citation2013).

In the times of ‘open data,’ however, local government disclosure takes place via different media (print or electronically), different documents (e.g. plans, reports, policy papers), at different intervals, and may be a stand-alone activity or part of a larger process. Furthermore, indicators can be used descriptively or with performance-oriented targets and rankings, which has profound management implications (Behn Citation2003). Therefore, studying mere disclosure faces ceiling effects and loses analytical power as it eschews the question of organizational use.

The alternative of researching the production of reports – as opposed to information – is challenging too. How many local governments have sustainability reports? This is difficult to answer in the absence of straightforward conceptual boundaries on what constitutes sustainability reporting. While some documents labelled ‘sustainability reports’ are little more than indicator tables, others are extensive accounts of trends, actions and plans. Putative sustainability reports may carry idiosyncratic titles such as ‘City X – Progress Account.’ Standardized frameworks – for example, the GRI’s guidelines that are widely used by companies – have failed to catch on among local governments whose reports show considerable diversity without recurring to the GRI (Williams, Wilmshurst, and Clift Citation2011). GRI estimates to have information on about half of all reports applying its guidelines (personal communication, 7 April 2015). The GRI’s publicly accessible registry (http://database.globalreporting.org) currently lists 450 ‘public agencies’ – mainly public enterprises – and about 50 cities including Melbourne in Australia and Incheon in South Korea. With reporting remaining voluntary in most countries, there are no reliable registries nor estimates of reporters. Presumably the vast majority of the world’s local governments has never (consciously) engaged in sustainability reporting yet some ‘early adopters’ have multi-year experience.

Furthermore, distinguishing ‘reporters’ from ‘non-reporters’ becomes even more difficult when organizations forgo distinct reports while rather including sustainability considerations into their general reporting cycle. Advocates of integrated reporting – designated IR by the International Integrated Reporting Council (Citation2008) – herald this approach as an effective way to increase the relevance of sustainability information for decision makers. The aim is to promote ‘integrated thinking’ and to overcome duplications and ‘silo thinking’ by integrating information systems of internal and external reporting (Stacchezzini, Melloni, and Lai Citation2016). Early discussions included the idea for an organization’s integrated report to be a high-level overview yet the current IR framework proposes replacing other forms of reporting (de Villiers, Rinaldi, and Unerman Citation2014). Critics ironically dub IR the ‘new holy grail’ (Milne and Gray Citation2013) and talk of ‘capture’ by the accounting profession (Flower Citation2015) yet it is increasingly popular among companies and also influencing the public sector (Bartocci and Picciaia Citation2013). As with sustainability reporting, most academic studies have explored determinants of IR adoption. Thus focusing on the ‘icing rather than the cake,’ ‘only a few papers attempt to assess the consequences (costs and benefits) of integrated reporting’ – Perego, Kennedy, and Whiteman (Citation2016, 6) therefore argue that quantitative studies based on publicly available data are inadequate and call for more qualitative research. In the words of Mitchell, Curtis, and Davidson (Citation2008, 68), ‘We must look beyond what is presented in reports, and evaluate the impact on those involved in the process of reporting.’ Specifically for local governments, research is required to understand which type of sustainability reporting leads to which type of short-term and long-term benefits and constraints. Moreover, research requires context-sensitivity: a recent meta-analysis of social accountability mechanisms concluded that ostensibly identical tools (e.g. participatory monitoring) can be effective or not depending on how they are embedded in local policies, and thus only ‘the subnational comparative method can reveal patterns of variation that otherwise would be hidden by homogenizing national averages’ (Fox Citation2015, 356).

A framework to study reporting practices and outcomes

Researching the local use and usefulness of sustainability reporting requires appropriate models and methods. Since no single theoretical framework is able to cover the range of reporting practices (Marcuccio and Steccolini Citation2009), we seek to make a contribution by constructing a theoretical framework that facilitates the understanding of reporting outcomes. For this purpose, we draw on relevant literature and guidelines about reporting contexts, features, processes and outcomes.

Concerning contexts, a first observation is significant diversity: Local governments share the fact of governing limited, subnational geographical areas such as towns or counties yet this takes place in different economies, cultures, environments, legal systems, etc. In the sphere of sustainability management there are thus important debates about the appropriateness of developing standardized as opposed to context-specific approaches and tools (e.g. Moreno Pires, Fidélis, and Ramos Citation2014; Joss et al. Citation2015). Concerning sustainability disclosures by local governments, research points to the influence of administrative cultures and data availability (e.g. Alcaraz-Quiles, Navarro-Galera, and Ortiz-Rodríguez Citation2014; Krank, Wallbaum, and Grêt-Regamey Citation2010), making it plausible that reporting practices too are influenced by such macro-contextual differences.

As for reporting features, since the 1990s, the notion of the ‘triple bottom line’ has been popular and implies the idea that sustainability reports provide information on environmental, social and economic matters (de Villiers, Rinaldi, and Unerman Citation2014). In 2005, the GRI launched sustainability reporting guidelines for the public sector that suggest addressing three information types, namely organizational performance, public policies and contextual issues. illustrates these with examples.

Figure 1. Information types in public-sector reports according to GRI (Citation2005).

For the GRI, ‘The focus is to provide reporting guidance on the first and second type of information, as the third type of information is often included in other types of reports’ (Global Reporting Initiative Citation2005, 5). Reporting thus on organizational performance rather than on wider, city-level indicators is plausible for many public-sector organizations such as utilities or universities. After all, it is ‘unrealistic to hold agencies accountable for achieving outcomes that are largely affected by forces outside the organization’s control’ (Pitts and Fernandez Citation2009, 403). By the same token, disregarding ‘state of the environment’ monitoring is unsatisfactory for governments as they are organized along jurisdictional lines and enjoy certain control.

While the GRI framework is about retrospective reporting, failing to address the time dimension beyond comparing a report to the previous one (Lozano and Huisingh Citation2011), the IR framework also requires forward-looking projections and targets (Stacchezzini, Melloni, and Lai Citation2016). This implies another information type, labelled ‘outlook,’ and implicitly addresses the question of periodicity. In the private sector, both financial and sustainability reports are usually published annually, strengthening the case for their integration, yet this is no necessity. Many local governments in Germany issue sustainability reports at multi-year intervals (Plawitzki Citation2010).

Concerning non-manifest aspects of reporting, practitioners face essential design choices. Who should be involved, what should those involved be doing and what process should they follow (Mitchell, Curtis, and Davidson Citation2008)? For these process questions, normative frameworks offer little guidance. Sustainability reporting as promoted by the GRI recommends the participation and targeting of a wide stakeholder audience, while IR has a narrower focus on providers of financial capital (C. A. Adams Citation2015). The latter may be inappropriate for the public sector (Bartocci and Picciaia Citation2013); for local governments, key stakeholders relevant for reporting minimally include civil servants, politicians and the public. Another process feature concerns external auditing which according to some authors ‘should be a permanent element of every sustainability report’ (Greiling and Grüb Citation2014, 220). The evidence base for this assertion is, however, scarce. Most extant research eschews the ‘black box’ of organizational processes (Perego, Kennedy, and Whiteman Citation2016).

As for outcomes associated with reporting, normative frameworks extol the positive – GRI guidelines do not identify costs but list multiple benefits including enhanced ‘intra- and inter-departmental coordination,’ ‘operating efficiency’ and ‘participation by various stakeholders in decision making and governance’ (GRI Citation2005). Integrated reporting implicitly alludes to potentially negative outcomes when promising to stop ‘numerous, disconnected and static communications’ (IIRC Citation2008, 2). IR thus draws attention to information needs and uses, an issue often neglected in transparency agendas. ‘The more information there is in a report about individual, social, environmental and economic impacts, policies and practices, the greater is the likelihood of information overload for readers’ (de Villiers, Rinaldi, and Unerman Citation2014, 1045). Evidently, sustainability reporting may have unintended consequences. With the introduction of reporting, some non-profit organizations apparently experienced that ‘morality was replaced by the financial bottom line’ (Dumay, Guthrie, and Farneti Citation2010, 534).

Some scholars distinguish informative and transformative reporting impacts; the latter is about external, communicative and the former about internal, managerial perspectives (Perego, Kennedy, and Whiteman Citation2016). Since many of the (purported) benefits of sustainability reporting concern organizational issues (see Lamprinidi and Kubo Citation2008), it appears expedient to conceptualize these in more detail. In this regard, a framework used in evaluation research that distinguishes three types of information use produces worthwhile insights. According to its main proponents, ‘Instrumental use is presumed to yield decisions of one kind or another. Conceptual use yields ideas and understanding. Political use yields support and justification for action or no action’ (Weiss, Murphy-Graham, and Birkeland Citation2005, 14). This typology allows the clustering of manifest impacts whilst also paying attention to the ‘politics of policymaking’ (Bauler Citation2012). In their prefaces to sustainability reports, for example, mayors commonly express the wish to promote accountability, yet beyond such socially valued aims, any publication can also be used as ‘ammunition’ in political debates (Lyytimäki et al. Citation2013). Since ‘use’ connotes intentionality, some researchers suggest also probing for information ‘influence,’ noting that use does not imply influence, and influence does not require conscious use (Lehtonen, Sébastien, and Bauler Citation2016).

juxtaposes three main uses, influences and outcomes of sustainability reporting with associated stakeholders, acknowledging that this is a simplification of complex matters. There is evidence of (public sector) sustainability reporting leading to organizational learning, facets of improved management, and positively valued communication with outside audiences (e.g. S. Adams and Simnett Citation2011). One might argue that sustainability reports can also foster learning or decision-making among citizens; after all, some mayoral prefaces profess that wish. Prior research on local government reports, however, found negligible citizen uptake (Steccolini Citation2004). It has been asserted that ‘as far as the public is concerned, the publication of performance data in annual reports and government white papers is for the most part equivalent to putting a message in a bottle and throwing it into the sea’ (Pollitt Citation2006, 52). Concerning external audiences, the agenda-setting influence of reporting is more plausible. further addresses the observability of outcomes, which we rated as generally low for internal ones and very low for external ones. This conjectural assessment, informed by the literature (e.g. Sébastien and Bauler Citation2013), serves to highlight the complexity of researching the effects of sustainability reporting. Most organizational changes and learning processes are incremental and influences on external stakeholders highly ephemeral, necessitating qualitative research methods (Perego, Kennedy, and Whiteman Citation2016).

Table 2. Outcomes associated with sustainability reporting.

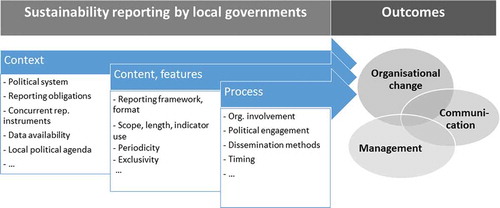

In summarizing the literature and concepts introduced so far, we posit that three main factors (roughly corresponding to independent variables) influence the effects of sustainability reporting by local governments: (i) context, (ii) reporting features and (iii) process characteristics. Concerning (ii) features, the three information types proposed by the GRI (context, policies, organizational performance) plus outlook derived from IR constitute relevant constructs; for (iii) processes, prior literature lends face validity to the distinction of organizational involvement, political efforts and dissemination strategies. Finally, adding organizational change, management and communication as outcome-oriented research categories (dependent variables) leads to the assessment framework presented in .

Research methods

To test the assessment framework, we applied it to real-world practices. In light of evidence that the adoption of reporting is influenced by short-lived fashions (Marcuccio and Steccolini Citation2005), we considered it most instructive to study cases where sustainability reporting was developed over longer periods. The purposeful selection of ‘early adopters,’ ‘frontrunners’ and ‘reporting champions’ as cases is a well-established methodological choice (e.g. Bebbington, Higgins, and Frame Citation2009; C. A. Adams and Frost Citation2008). Our main selection criteria thus were the implementation of sustainability reporting over several years and positive appraisal from researchers, peers or the awarding of public prizes. To ensure a minimum and comparative level of administrative capacities, we chose to focus on European cities with at least 100,000 inhabitants. The six Dutch, German, Irish and Swiss cities presented in were identified via the literature (see ), report registries including the GRI’s, and by consulting experts in international organizations including GRI and ICLEI.

Table 3. Case study cities.

To explore the context, history, emergent practices and effects of sustainability reporting in accordance with the theoretical framework () required applying mixed research methods. As virtually all outcome areas including organizational change and agenda-setting are not directly observable (cf. ), we applied a document analysis and exploited insights retrieved from key informants. In each city, semi-structured interviews were held with three types of informants: civil servants, elected politicians (mayor or city councillor) and academics or NGO representatives. Adding the GRI, nineteen interviews (each lasting 30–90 min) with twenty-one informants (numbered as I.1 to I.21) were held during visits and by telephone. All interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed and key statements translated into English for interviews held in German and Dutch. Data were collected and coded according to the assessment framework () and the additional operationalization presented in . For each discernible reporting practice, the first author qualitatively rated four reporting features, namely the comprehensiveness and quality of information concerning context, public policies, organizational performance and outlook. Further qualitative ratings were applied to the aggregate intensity of three process features (organizational involvement, political involvement and dissemination efforts) and the perceived strength of effects in three outcome clusters (organizational change, management, communication). The rating was omitted when interviewees lacked knowledge, for example, of processes dating 10 years ago.

Table 4. Operationalization of research constructs.

This study design has evident limitations: from six, purposefully selected, diverse yet well-resourced ‘pioneers’ one cannot generalize findings to hypothetical ‘average local governments.’ While the theoretical framework assumes the importance of context factors, the small case number did not allow exploring these in detail. The fact that cities were identified by name may have contributed to biased responses from key informants, though this risk was mitigated by triangulation strategies. Experimenting voluntarily with diverse strategies, local governments had little performance pressure, and interviewees expressed much openness to share shortcomings and critical reflections.

Results from six cities

The six analysed ‘early adopters’ all initiated sustainability reporting voluntarily. Over the years, each deliberately made different major design choices. This section presents a comparative assessment, starting with observations on features, processes and outcomes before identifying potential causal links.

At the level of reporting features, in four cities we identified one major practice such as tri-annual reports in Nuremberg and annual reports in Dublin. For Zurich, we distinguished two phases, as its local government initially published longer, multi-year reports before changing to shorter, annual ones. Amsterdam experimented with various strategies including stand-alone sustainability reports, followed by the integration of sustainability indicators into its general (annual, financial) statements, and the launching of a ‘sustainability agenda.’ The last two instruments do not represent typical sustainability reports; nonetheless, analysing them appeared vital to understand the evolving system. According to official documents, Amsterdam will relaunch dedicated, annual sustainability reports to ‘enter into an intensive dialogue with the city’ while ‘the financial statements can then focus on managing on the basis of the results and targets’ (Amsterdam Municipality Citation2015, 60). In the six cities, we thus identified nine sustainability reporting practices that are summarized in . Evidently, discerning reporting practices is not clear-cut; in every local government, multiple reporting instruments exist in parallel and evolve over time.

Table 5. Comparative assessment of reporting features and perceived outcomes.

Comparing features of stand-alone reports revealed diverse information quantities (e.g. documents with 31 pages in Zurich, 126 in Nuremberg), the absence of external auditing, and the predominance of own, tailor-made formats. Amsterdam (initially), Dublin and Freiburg made loose references to GRI guidelines yet all local governments argued that no existing framework met their needs, prompting the development of their own formats. In the view of several key informants, comparisons and benchmarking were desirable but local relevance an overriding concern. In the words of one civil servant (I.13), ‘It’s good that there are no standardised indicator sets. At most a menu makes sense where local governments can choose which indicators are important for us.’

The analysis of content quality showed a mixed picture. Most reports addressed questions of context, public policies, organizational performance and outlook to some degree. In Zurich, switching from multi-year to annual reports brought reduced coverage of context and outlook issues. Freiburg’s report stands out since it pays detailed attention to (select) public policies and organizational performance while lacking city-level outcome indicators, a context feature common to most sustainability reports. From one edition to another, reports usually discuss long-term trends through a set of indicators (ranging from 21 in Basel to over 100 in Nuremberg). In addition to such continuity in monitoring, Nuremberg’s reports contain changing focus themes (e.g. ‘education’).

The exploration of reporting processes showed that in most cities report writing was led by staff units that engaged other departments in indicator selection and the drafting of narratives. In some cities, external stakeholders were also consulted in the design stage (e.g. universities in the case of Zurich, Dublin and Freiburg). Generally, draft reports then underwent a screening process by political decision makers such as members of the municipal executive. In some cities, finalized reports were discussed in the municipal council, evidencing political involvement. In this context, exclusivity plays a role – Freiburg stressed that its sustainability report, seemingly a stand-alone document, was actually highly integrated into the policy cycle because councillors received it as sole annex to the (biannual) budget. According to a politician (I.2) from Amsterdam:

If sustainability reporting is separate, we will discuss it separately in the council. When reviewing the annual report, somebody might have a question about sustainability but the discussion will be about finances. Thus, a separate report gets more attention.

Interestingly, Basel opted for the contrary when its local government recently decided to discontinue sustainability reporting and merge it with general reporting. According to a Basel political executive (I.5),

In our system, we have departmental reports but they remain at the bottom of the drawer […]. This is why we decided […] to join cyclical assessments, planning, general reporting and sustainability reporting in a four yearly rhythm. […] Of course, the danger of integration is that the ‘flying altitude’ rises, with much more general, noncommittal accounts.

Contrary to practices elsewhere, Nuremberg’s report did not undergo extensive internal vetting. In the words of a civil servant (I.13), ‘These are the environmental department’s analyses. Neither the mayor nor others ever objected. Our critical views are backed up by indicators nobody can simply refute.’ Interestingly, reporting is thus used politically within the collegiate as part of debates between the economics and environmental departments.

For the dissemination of reports, all local governments recently used websites and social media. Usually this involves making reports available for download (with Dublin’s not existing in print); only Zurich visualizes its data on a dedicated dashboard. Additional dissemination efforts varied significantly, as a civil servant (I.8) from one city explained:

For the first two reports, we did larger events […], a media conference with councillors. We phased that out. Now our main motivation is actually an obligation – we can’t just leave the website unattended. In 2013 we wanted to do a public event but it was difficult to get attention. Which is understandable from the media perspective. The news value is not so large.

Regarding outcomes, it appeared that even though none of the local governments explicitly started sustainability reporting with the aim to learn from the writing process, such effects were evident in all cities. Key informants frequently mentioned more inspiration, motivation, cooperation and improved data management systems triggered by the inter-departmental elaboration of indicator sets and narratives. According to one civil servant (I.13), ‘It has been a lot of work to bring all indicators together but when we produced Nuremberg’s first sustainability report it had a resounding effect in Germany. We printed 1000 copies which were gone in no time.’

Unsurprisingly, there is tentative evidence for a link between organizational involvement and organizational learning. Freiburg officials, for example, mentioned improved morale resulting from extensive staff consultations. However, such relationships appear to be non-linear. Several organizational benefits, for example, improved data management capacities and collegial contacts, were associated with the elaboration of a first report and not consecutive ones. Concerning outcomes in the sphere of management, stronger effects were observed in Amsterdam and Freiburg. In these cities, there is evidence of reports being actively used by decision makers. This appears to relate to the presence of two main content factors: targets and politically salient information. In Zurich, for example, politicians showed keen interest in a public perception survey (one of twenty-one sustainability indicators) as this reflects on voter opinions. However, one interviewee (I.8) also observed:

Setting targets is political. That needs to be backed up; we cannot do that as municipal administration. Even using a traffic light – we tried to discuss this in the steering group yet realised that this immediately leads to controversial discussions […]. Our sustainability monitoring system is not the central management instrument of our city governments […]. All departments have their own key indicators.

As for outcomes in the sphere of communication, most local governments lacked insights and relevant data (e.g. media statistics) about the reception of reports by external stakeholders. Only in Amsterdam, Dublin and Nuremberg there was anecdotal evidence of active resonance among local audiences such as newspapers, businesses, NGOs or universities. In Dublin, Nuremberg and Freiburg, reporting triggered contact requests from many other cities, nationally and internationally. There is no evidence that any reporting methods were directly emulated in other cities or organizations. Some local governments received public recognition for their reporting, for example, Nuremberg in the awarding of the German Sustainability Prize.

Concerning negative outcomes, several cities experienced frictions when civil servants perceived report writing as a burden. Critically, in some cities including Dublin and Zurich, key informants spoke of ‘reporting fatigue’; positive effects associated with initial reports were perceived to wear out in the face of decreasing internal ‘learning curves’ or reduced public interest. In the words of a Dublin civil servant (I.16): ‘One of the first things about the high frequency is that it ends up being a lot of work. Unfortunately, you end up repeating a lot of things. There’s no new data. […] There’s definitely the idea of consultation fatigue.’ Among the six local governments studied, four (Amsterdam, Basel, Dublin and Zurich) discontinued or substantially changed their sustainability reporting practices due to dissatisfaction with the approach taken hitherto. This suggests that designing a reporting system with continued use and usefulness is no easy chore.

Among early adopters, Nuremberg’s strategy appeared most continuous. Its ostensibly successful strategy, within its particular context, is the elaboration of extensive, low-periodicity reports with a fixed indicator set yet changing focus themes. A Nuremberg politician (I.14) remarked: ‘I am not a friend of yearly reporting because especially the big issues – air quality, education – don’t change that quickly.’

At a macro level, Amsterdam’s experience and decision to develop several sustainability-oriented planning and reporting instruments in parallel suggests that learning, management and communication – and associated internal and external audiences – require distinct strategies. This interpretation also fits Freiburg’s approach: its highly complex sustainability report – initiated when accruals accounting and performance-oriented budgeting became compulsory for local governments in this part of Germany – implicitly targets councillors, not the public. In the words of a civil servant (I.10),

We have excellent sectoral reports that go into detail. Our sustainability report can’t emulate this. [Its] contribution is to create an overall context […] to stimulate ideas or to identify trade-offs and goal conflicts. For example, we all want to promote public transport and cycling, that’s a declared aim but also requires using space and cutting some trees […]. We don’t have a red or green traffic light but want to show the municipal council its options for action.

Evidently, action orientation helps to increase salience of reports for specific target groups such as councillors. In this regard, political systems constitute an important contextual factor. As a politician from Dublin (I.17) remarked, ‘In Ireland, the amount of competencies of local government are fairly small. So one could have a fairly incomplete picture if one only looked at the city council’s own activities.’

Discussion and conclusion

In response to our research question – how have sustainability reporting practices evolved in pioneering European local governments, and what are their effects – this study covering six cities in four European countries showed that various types of reporting can be valuable for local governments as a learning, management and communication tool. Financial costs can be very limited; some local governments do not even print their reports and rely only on electronic dissemination. There is evidence of organizational benefits, for example, concerning increased staff motivation and data management capacities. This is noteworthy as internal changes were usually no explicit objective. This finding is in line with other studies, for example, the perception of sustainability reporting as a learning experience in universities (Ceulemans, Lozano, and Alonso-Almeida. Citation2015) and of voluntary yet publicized self-assessments stimulating sustainability policies among local governments (Niemann, Hoppe, and Coenen Citation2016). Organizational outcomes, however, tended to be strongest during the inception of sustainability reporting and to dissipate over time, while (continued) usefulness for management purposes and external communication appeared more difficult to achieve. Various local governments experienced ‘reporting fatigue,’ leading to the discontinuation or radical altering of sustainability reporting practices.

This study’s findings tentatively suggest that meeting different information needs of different stakeholders requires smart strategies such as combining extensive, multi-year reports with executive annual updates disseminated in various media. For some local governments studied, especially those producing stand-alone reports, the pursuit of public legitimacy is an explicit objective, corroborating prior studies (Marcuccio and Steccolini Citation2009). In some cities, this endeavour is relatively successful, with active dissemination efforts producing desired resonance (such as the launching of reports in public events). Various local governments, on the other hand, struggled to maintain public interest over time. This appears to relate to a lack of news value when repeated reports showed unchanged trends on descriptive indicators yet also to a lack of politically salient information. Most local governments meticulously vet narratives so as to accommodate diverging opinions. In one deviant case, the published report is more outspoken and used for ‘debates’ between executives. The space for such utilization appears to be influenced by political systems and cultures (cf. Alcaraz-Quiles, Navarro-Galera, and Ortiz-Rodríguez Citation2014), with cases in this study showing sub-national diversity in political embeddedness (cf. Fox Citation2015). Local governments tying sustainability to policy and budgetary cycles aim to inform management, and there is tentative evidence of this being effective. However, targeting internal decision makers has consequences for the design and writing style of relevant documents – as also asserted elsewhere (Cohen and Karatzimas Citation2015), sustainability reports geared towards managers are generally not attractive to citizens.

This suggests that sustainability reporting is no ‘magic tool’ simultaneously fulfilling communication and management functions; instead, attempts to reach all audiences with a single document are doomed to fail, ushering in ‘jackof all trades – master of none.’ Simply calling for integrated, high-frequency, high-complexity reporting is misguided as there are trade-offs between conciseness and completeness (cf. Perego, Kennedy, and Whiteman Citation2016). In the words of one NGO representative (I.12) interviewed:

If you have the ambition of achieving an integrated approach, you’ll quickly face unmanageable amounts of data and thick reports nobody reads. Or you’re describing in one chapter what you’re doing against soil sealing, and in another […] the shortage of housing, as if the two were not related. Then you have some cities that simply decide to zoom in on focus areas but are rightly challenged too. The crux is solving this tension between comprehensive and focussed.

As a matter of fact, integration can refer to several dimensions including report types, contents and internal processes, and sustainability reporting requires making choices for each. At the same time, many national statistics offices are mounting sophisticated dashboards that individual local governments need not compete with in terms of disclosing macro indicators. The growth of interactive, electronically linked sustainability reporting formats leads to yet more diverse uses by wide-ranging audiences. Facing these developments and choices, there is high demand for guidance that current frameworks (e.g. GRI, IR) do not provide. The GRI’s focus on organizational performance without considering territorial outcomes is unsatisfactory for (local) governments. For them, the linking of policies and actions to territorial outcomes constitutes the ultimate management and accountability demand.

Against this backdrop, the framework developed in this study – revolving around the distinction of main contents (context, policies, performance and outlook), key process considerations (organizational involvement, political involvement, dissemination) and three outcome clusters (organizational change, management and communication) – is valuable for multiple audiences.

For practitioners, the framework is a point of departure to initiate or redesign sustainability reporting successfully. While the presence of trade-offs and our analysis of a small while diverse set of front runners makes searching generalizable ‘best practices’ inappropriate, this study uncovered many ‘good practices’ that practitioners elsewhere will find inspiring. identifies such practices in relation to our research framework and case studies. The tentative rating of complexity (low/medium /high) serves to indicate ease of replicability. The selection of context indicators and compilation of relevant data, for example, is relatively straightforward and constitutes a recommendable practice for any city initiating sustainably reporting. Political target-setting and impact assessments of governmental decisions, on the other hand, are complex and require more skills and resources.

Table 6. Positive local government reporting practices.

Regarding outcomes, contains the implicit recommendation for sustainability reporters to self-evaluate. Simple satisfaction surveys among report contributors and the monitoring of download statistics, for example, produce important feedback at hardly any cost. Researching the utilization of reports by various audiences is more complex yet may interest a local university, as happened in Basel. For policymakers – including those contemplating mandatory municipal sustainability reporting as in France, or subsidized voluntary reporting as in parts of Germany (LUBW Citation2015) – the framework and evidence produced by this study will give guidance about policy objectives and local government needs.

For researchers, the theoretical framework and major design choices identified in this article – such as periodicity, information types, process arrangements – suggest major lines of enquiry. In terms of sustainability reporting, we posit that the focus on disclosure as main research paradigm has had its day, and that more utilization- and impact-oriented studies are urgently needed. There is potential for increased mutual learning with the adjacent fields of performance management (see e.g. Navarro Galera, Rodriguez, and López Hernández Citation2008) and city-oriented sustainability monitoring (see e.g. Tanguay et al. Citation2010). lists a set of hypotheses derived from this explorative study to inform further research.

Table 7. Hypotheses for further research.

In light of preliminary evidence that sustainability reporting by local governments can be beneficial at limited costs and risks, we conclude by calling for perseverant yet reflective experimentation. As a civil servant from Dublin (I.16) put it:

You have to say on the first day: We’re going to do five years of sustainability reporting and then evaluate. Just to create that expectation. Because it’s very hard to do a good job the first time. You have to learn the lesson.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the open sharing of data and thoughts by all interviewed practitioners, institutional support provided by VNG International (The Hague), and feedback on the manuscript from anonymous reviewers and Larry J. O’Toole.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ludger Niemann

Ludger Niemann works as Lecturer in International Public Management at The Hague University of Applied Sciences. He holds degrees in Natural Sciences (Cambridge University), Psychology (Freiburg University) and Public Administration (Erasmus University Rotterdam), and is a PhD candidate at the University of Twente researching the use of sustainability indicators in Latin American and European cities.

Thomas Hoppe

Thomas Hoppe holds a master’s degree in Public Administration specializing in Public Policy and Environmental Policy, and a PhD in Public Policy from the University of Twente. Thomas’ research focus is ‘Governance of Energy Transitions’. Currently, he works as Associate Professor at the section of Policy, Organisation, Law and Gaming (POLG) within the Multi Actor Systems (MAS) department of the faculty of Technology, Policy and Management (TPM) at Delft University of Technology.

References

- Adams, C. A. 2015. “The International Integrated Reporting Council: A Call to Action.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 27 (Mar.): 23–28. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2014.07.001.

- Adams, C. A., and G. R. Frost. 2008. “Integrating Sustainability Reporting into Management Practices.” Accounting Forum 32 (4): 288–302. doi:10.1016/j.accfor.2008.05.002.

- Adams, S., and R. Simnett. 2011. “Integrated Reporting: An Opportunity for Australia’s Not-For-Profit Sector: Integrated Reporting for Not-For-Profit Sector.” Australian Accounting Review 21 (3): 292–301. doi:10.1111/j.1835-2561.2011.00143.x.

- Alcaraz-Quiles, F. J., A. Navarro-Galera, and D. Ortiz-Rodríguez. 2014. “Factors Determining Online Sustainability Reporting by Local Governments.” International Review of Administrative Sciences, Nov.: 20852314541564. doi:10.1177/0020852314541564.

- Amsterdam Municipality. 2015. Sustainable Amsterdam. Agenda for Renewable Energy, Clear Air, a Circular Economy and a Climate-Resilient City. Adopted by the Municipal Council of Amsterdam. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Municipality.

- Ballantine, J. 2014. ‘The Value of Sustainability Reporting by Cities.” Cities Today, December 1. http://cities-today.com/2014/12/value-sustainability-reporting-cities/

- Bartocci, L., and F. Picciaia. 2013. “Towards Integrated Reporting in the Public Sector.” In Integrated Reporting. Concepts and Cases that Redefine Corporate Accountability, edited by C. Busco, M. Frigo, A. Riccaboni, and P. Quattrone, 191–204. Cham: Springer.

- Bauler, T. 2012. “An Analytical Framework to Discuss the Usability of (Environmental) Indicators for Policy.” Ecological Indicators 17: 38–45. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.05.013.

- Bebbington, J., C. Higgins, and B. Frame. 2009. “Initiating Sustainable Development Reporting: Evidence from New Zealand.” Accounting, Auditing Accountability Journal 22 (4): 588–625. doi:10.1108/09513570910955452.

- Behn, R. D. 2003. “Why Measure Performance? Different Purposes Require Different Measures.” Public Administration Review 63 (5): 586–606. doi:10.1111/1540-6210.00322.

- Bovens, M. 2005. “Public Accountability.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Management, edited by E. Ferlie, L. Lynn, and C. Pollitt, 182–208. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ceulemans, K., R. Lozano, and M. Alonso-Almeida. 2015. “Sustainability Reporting in Higher Education: Interconnecting the Reporting Process and Organisational Change Management for Sustainability.” Sustainability 7 (7): 8881–8903. doi:10.3390/su7078881.

- Cohen, S., and S. Karatzimas. 2015. “Tracing the Future of Reporting in the Public Sector: Introducing Integrated Popular Reporting.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 28 (6): 449–460. doi:10.1108/IJPSM-11-2014-0140.

- CGDD (Commissariat Général au Développement Durable). 2012. Premiers Éléments Méthodologiques Pour L’élaboration Du Rapport Sur La Situation En Matière de Développement Durable À L’usage Des Collectivités Territoriales et EPCI À Fiscalité Propre de plus de 50 000 Habitants. Paris: Service de l’Économie, de l’Évaluation et de l’Intégration du Développement Durable.

- de Villiers, C., L. Rinaldi, and J. Unerman. 2014. “Integrated Reporting: Insights, Gaps and an Agenda for Future Research.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 27 (7): 1042–1067. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-06-2014-1736.

- Downe, J., C. Grace, S. Martin, and S. Nutley. 2010. “Theories of Public Service Improvement.” Public Management Review 12 (5): 663–678. doi:10.1080/14719031003633201.

- Dumay, J., J. Guthrie, and F. Farneti. 2010. “GRI Sustainability Reporting Guidelines For Public and Third Sector Organizations. A Critical Review.” Public Management Review 12 (4): 531–548. doi:10.1080/14719037.2010.496266.

- Flower, J. 2015. “The International Integrated Reporting Council: A Story of Failure.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 27 (Mar.): 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2014.07.002.

- Fox, J. A. 2015. “Social Accountability: What Does the Evidence Really Say?” World Development 72 (Aug.): 346–361. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.011.

- Freiburg Municipality. 2014. 1. Freiburger Nachhaltigkeitsbericht. Beispielhafter Ausschnitt Zur Darstellung Des Nachhaltigkeitsprozesses. Freiburg Sustainability Report. Freiburg im Breisgau.

- GRI (Global Reporting Initiative). 2005. Sector Supplement for Public Agencies. Amsterdam: Global Reporting Initiative.

- Goswami, K., and S. Lodhia. 2014. “Sustainability Disclosure Patterns of South Australian Local Councils: A Case Study.” Public Money & Management 34 (4): 273–280. doi:10.1080/09540962.2014.920200.

- Greco, G., N. Sciulli, and G. D’onza. 2012. “From Tuscany to Victoria: Some Determinants of Sustainability Reporting by Local Councils.” Local Government Studies 38 (5): 681–705. doi:10.1080/03003930.2012.679932.

- Greiling, D., and B. Grüb. 2014. “Sustainability Reporting in Austrian and German Local Public Enterprises.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 17 (3): 209–223. doi:10.1080/17487870.2014.909315.

- Guthrie, J., A. Ball, and F. Farneti. 2010. “Advancing Sustainable Management of Public and Not for Profit Organizations.” Public Management Review 12 (4): 449–459. doi:10.1080/14719037.2010.496254.

- Guthrie, J., and F. Farneti. 2008. “GRI Sustainability Reporting by Australian Public Sector Organizations.” Public Money and Management 28 (6): 361–366.

- Hahn, R., and M. Kühnen. 2013. “Determinants of Sustainability Reporting: A Review of Results, Trends, Theory, and Opportunities in an Expanding Field of Research.” Journal of Cleaner Production 59 (Nov.): 5–21. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.005.

- IIRC (International Integrated Reporting Council). 2008. “Consultation Draft of the International Integrated Reporting Framework.” http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/13-12-08-THE-INTERNATIONAL-IR-FRAMEWORK-2-1.pdf

- Joss, S., R. Cowley, M. de Jong, B. Müller, B. S. Park, W. E. Rees, M. Roseland, and Y. Rydin. 2015. Tomorrow’S S City Today. Prospects for Standardising Sustainable Urban Development. London: University of Westminster.

- Krank, S., H. Wallbaum, and A. Grêt-Regamey. 2010. “Constraints to Implementation of Sustainability Indicator Systems in Five Asian Cities.” Local Environment 15 (8): 731–742. doi:10.1080/13549839.2010.509386.

- Lamprinidi, S., and N. Kubo. 2008. “Debate: The Global Reporting Initiative and Public Agencies.” Public Money & Management 28 (6): 326–329. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9302.2008.00663.x.

- Lehtonen, M., L. Sébastien, and T. Bauler. 2016. “The Multiple Roles of Sustainability Indicators in Informational Governance: Between Intended Use and Unanticipated Influence.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 18 (February): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.05.009.

- Lodhia, S., K. Jacobs, and Y. J. Park. 2012. “Driving Public Sector Environmental Reporting: The Disclosure Practices of Australian Commonwealth Departments.” Public Management Review 14 (5): 631–647. doi:10.1080/14719037.2011.642565.

- Lozano, R., and D. Huisingh. 2011. “Inter-Linking Issues and Dimensions in Sustainability Reporting.” Journal of Cleaner Production 19 (2–3): 99–107. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.01.004.

- LUBW. 2015. N!-Berichte Für Kommunen. Leitfaden Zur Erstellung von Nachhaltigkeitsberichten in Kleinen Und Mittleren Kommunen. 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Ministerium für Umwelt,Klima und Energiewirtschaft Baden-Württemberg.

- Lyytimäki, J., P. Tapio, V. Varho, and T. Söderman. 2013. “The Use, Non-Use and Misuse of Indicators in Sustainability Assessment and Communication.” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 20 (5): 385–393. doi:10.1080/13504509.2013.834524.

- Marcuccio, M., and I. Steccolini. 2005. “Social and Environmental Reporting in Local Authorities.” Public Management Review 7 (2): 155–176. doi:10.1080/14719030500090444.

- Marcuccio, M., and I. Steccolini. 2009. “Patterns of Voluntary Extended Performance Reporting in Italian Local Authorities.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 22 (2): 146–167. doi:10.1108/09513550910934547.

- Milne, M. J., and R. Gray. 2013. “W(H)Ither Ecology? The Triple Bottom Line, the Global Reporting Initiative, and Corporate Sustainability Reporting.” Journal of Business Ethics 118 (1): 13–29. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1543-8.

- Mitchell, M., A. Curtis, and P. Davidson. 2008. “Evaluating the Process of Triple Bottom Line Reporting: Increasing the Potential for Change.” Local Environment 13 (2): 67–80. doi:10.1080/13549830701581937.

- Moreno Pires, S., T. Fidélis, and T. B. Ramos. 2014. “Measuring and Comparing Local Sustainable Development through Common Indicators: Constraints and Achievements in Practice.” Cities 39: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2014.02.003.

- Navarro Galera, A., A. de los Ríos Berjillos, M. R. Lozano, and P. T. Valencia. 2014. “Transparency of Sustainability Information in Local Governments: English-Speaking and Nordic Cross-Country Analysis.” Journal of Cleaner Production 64 (February): 495–504. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.038.

- Navarro Galera, A., D. O. Rodriguez, and A. M. López Hernández. 2008. “Identifying Barriers to the Application of Standardized Performance Indicators in Local Government.” Public Management Review 10 (2): 241–262. doi:10.1080/14719030801928706.

- Niemann, L., T. Hoppe, and F. Coenen. 2016. “On the Benefits of Using Process Indicators in Local Sustainability Monitoring: Lessons from a Dutch Municipal Ranking (1999–2014).” Environmental Policy and Governance. doi:10.1002/eet.1733/full.

- Perego, P., S. Kennedy, and G. Whiteman. 2016. “A Lot of Icing but Little Cake? Taking Integrated Reporting Forward.” Journal of Cleaner Production 136 (Feb.): 53–64. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.106.

- Pitts, D. W., and S. Fernandez. 2009. “The State of Public Management Research: An Analysis of Scope and Methodology.” International Public Management Journal 12 (4): 399–420. doi:10.1080/10967490903328170.

- Plawitzki, J. K. 2010. “Welcher Voraussetzungen Bedarf Es in Deutschen Kommunen Für Die Erstellung Eines Nachhaltigkeitsberichtes?” [What Conditions are Required in German Local Governments for the Elaboration of a Sustainability Report?]. Bachelor thesis, Leuphana Universität, Lüneburg.

- Pollitt, C. 2006. “Performance Information for Democracy the missing link?” Evaluation 12 (1): 38–55.

- Pollitt, C., and P. Hupe. 2011. “Talking about Government. The Role of Magic Concepts.” Public Management Review 13 (5): 641–658. doi:10.1080/14719037.2010.532963.

- Sébastien, L., and T. Bauler. 2013. “Use and Influence of Composite Indicators for Sustainable Development at the EU-Level.” Ecological Indicators 35: 3–12. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.04.014.

- Stacchezzini, R., G. Melloni, and A. Lai. 2016. “Sustainability Management and Reporting: The Role of Integrated Reporting for Communicating Corporate Sustainability Management.” Journal of Cleaner Production 136 (Feb.): 102–110. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.109.

- Steccolini, I. 2004. “Is the Annual Report an Accountability Medium? An Empirical Investigation into Italian Local Governments.” Financial Accountability & Management 20 (3): 327–350. doi:10.1111/fam.2004.20.issue-3.

- Stubbs, W., and C. Higgins. 2014. “Integrated Reporting and Internal Mechanisms of Change.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 27 (7): 1068–1089. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-03-2013-1279.

- Tanguay, G. A., J. Rajaonson, J.-F. Lefebvre, and P. Lanoie. 2010. “Measuring the Sustainability of Cities: An Analysis of the Use of Local Indicators.” Ecological Indicators 10 (2): 407–418. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2009.07.013.

- Weiss, C. H., E. Murphy-Graham, and S. Birkeland. 2005. “An Alternate Route to Policy Influence How Evaluations Affect DARE.” American Journal of Evaluation 26 (1): 12–30. doi:10.1177/1098214004273337.

- Willems, T., and W. Van Dooren. 2012. “Coming to Terms with Accountability.” Public Management Review 14 (7): 1011–1036. doi:10.1080/14719037.2012.662446.

- Williams, B., T. Wilmshurst, and R. Clift. 2011. “Sustainability Reporting by Local Government in Australia: Current and Future Prospects.” Accounting Forum 35: 176–186. doi:10.1016/j.accfor.2011.06.004.

- Yigitcanlar, T., and A. Lönnqvist. 2013. “Benchmarking Knowledge-Based Urban Development Performance: Results from the International Comparison of Helsinki.” Cities 31: 357–369. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2012.11.005.