ABSTRACT

Do civil servants in some countries have higher organizational commitment? Is there any substantial cross-national variation in the form and degree of commitment? Good governance studies show a positive link between Weberian bureaucracy and favourable macro-level outcomes. However, previous comparative research is silent regarding cross-national differences of individual bureaucrats’ attitudes and their relationship with national bureaucratic structures. Employing social exchange theory, we argue that closed civil service systems produce higher commitment in senior public officials than open systems do. Using two large data sets in 20 European countries, we find closed systems are associated with continuance and normative commitment.

Introduction

The last two decades have seen a reappraisal of Weberian bureaucratic structures and of the significant role bureaucracy plays in shaping public policies, their implementation, and the related socioeconomic outcomes (Dahlström, Lapuente, and Teorell Citation2012a; Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2017; Evans and Rauch Citation1999; Fukuyama Citation2013; Miller Citation2000; Miller and Whitford Citation2016; Olsen Citation2006, Citation2008; Painter and Peters Citation2010; Rauch and Evans Citation2000; Rothstein and Teorell Citation2008). In particular, a large body of cross-national and sub-national studies show that politically autonomous and impartial bureaucratic structures (i.e. Weberian bureaucracy), where civil servants are recruited through merit examination and have tenure protection, have an empirical link with positive macro-level outcomes including socioeconomic development (Evans and Rauch Citation1999; Nistotskaya, Charron, and Lapuente Citation2015; Rauch and Evans Citation2000), corruption prevention (Charron et al. Citation2017; Dahlström, Lapuente, and Teorell Citation2012a), regulatory quality and entrepreneurship (Nistotskaya and Cingolani Citation2016), scientific productivity (Fernández-Carro and Lapuente-Giné Citation2016), innovation outputs (Suzuki and Demircioglu Citation2018), civic actions (Cornell and Grimes Citation2015), political legitimacy, satisfaction with government, and support for democracy (Boräng, Nistotskaya, and Xezonakis Citation2017; Dahlberg and Holmberg Citation2014; Rothstein Citation2009), and administrative effectiveness (Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2017).

While this line of good governance literature, mostly grounded in political science, has enhanced the understanding of the role of Weberian bureaucracy, we still know little about individual civil servants and how their attitudes are influenced by the administrative structure from a comparative perspective. On the other hand, a substantial body of the public management literature has examined the determinants of individual attitudes mainly within an organizational setting, not from a cross-national perspective. Despite the recent increase in attention to comparative and contextual factors in public management (Meier, Rutherford, and Avellaneda Citation2017; O’Toole and Meier Citation2015), the field is said to neglect the national characteristics of bureaucracies and a broad view of governance, assuming that ‘all states are alike’ (Milward et al. Citation2016, 312; Roberts Citation2018). In order to fill this gap, our paper aims to connect existing good governance literature with the public management literature, taking the individual-level outcomes into account.

This study examines how characteristics of national bureaucracy are associated with the degree and form of organizational commitment in senior public officials. The Weberian bureaucratic model is multidimensional, consisting of 1) a formal structure (e.g. hierarchy and specialization), 2) administrative procedures and processes (e.g. compliance to formal rules, strong emphasis on law), and 3) a personnel system (e.g. meritocratic recruitment, seniority, and tenure protection) (Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2017; Gualmini Citation2008). We focus on the personnel system, following previous studies (Cornell and Grimes Citation2015; Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2017; Evans and Rauch Citation1999; Nistotskaya and Cingolani Citation2016; Oliveros and Schuster Citation2018; Rauch and Evans Citation2000). In particular, we look at the degree to which recruitment and promotion systems of public officials are open or closed (Lægreid and Wise Citation2015; Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2017). Closed systems are characterized by the career distinctiveness of public service (Christensen Citation2012; Lœgreid and Wise Citation2007; Peters Citation2010; Rauch and Evans Citation2000). Public service careers are restricted through formalized exams, public employees enjoy lifetime tenure protection, and special labour regulations are applied to public sector employees. On the other hand, open systems feature career mobility of officials who switch between public and private sectors, more diverse and flexible access to the public sector, and less distinction between the public and the private.

To study employee commitment, we rely on the concept of organizational commitment (Meyer and Allen Citation1991; Meyer et al. Citation2012). Organizational commitment has been widely used as a significant indicator for employee attitude. According to Meyer and Allen (Citation1991) and Wiener and Vardi (Citation1980, 86), commitment can take three forms: (a) affective commitment (i.e. emotional attachment to organizational goals and values); (b) continuance commitment (i.e. commitment based on the side benefits and costs of leaving); and (c) normative commitment (i.e. feelings of obligation to remain with the organization). Specifically, we employ social exchange theory as a theoretical framework (Gould-Williams and Davies Citation2005; Gould-Williams Citation2007; McClean and Collins Citation2011; Nishii and Mayer Citation2009; Wayne, Shore, and Liden Citation1997; Van De Voorde, Paauwe, and Marc Citation2012).

Social exchange theory focuses on the exchange of obligations or the reciprocal relationship between employees and their organizations. Social exchange is defined as ‘voluntary actions of individuals that are motivated by the returns they are expected to bring and typically do in fact bring from others’ (Blau Citation1964, 93). When employees feel that their organizations are committed to them such as providing job security, training opportunities, fostering collegiality, they ‘seek a balance in their exchange relationships with organizations by having attitudes and behaviors commensurate with the degree of employer commitment to them as individuals’ (Wayne, Shore, and Liden Citation1997, 83). We argue that the characteristics of closed systems are more likely to produce such an exchange of obligations between organization and public officials than open systems, which leads to higher organizational commitment. Using two unique large comparative data sets in 20 European countries – the COCOPS Top Executive Survey (Hammerschmid Citation2015; Van de Walle et al. Citation2016) and the QoG (Quality of Government) Expert Survey (Dahlström et al. Citation2015a) – we find that closed systems are associated with continuance and normative commitment, but not with affective commitment. Thus, closed systems enhance commitment, but not all forms of commitment equally.

This paper first explains the theoretical framework for this study. The second section offers the hypotheses tested in this study while highlighting how variation in commitment is associated with characteristics of various civil service systems. The third section explains the data and methods of this study, followed by a fourth section containing results and analysis. Finally, this paper ends with discussion, conclusions, and limitations.

Weberian bureaucracy and open/closed civil service system

We focus on human resource management aspects as they are one of the core components of the Weberian model. Previous studies suggest that one significant way to characterize the personnel system of bureaucracy is to look at the extent to which systems are ‘open’ or ‘closed’ with respect to recruitment and promotion (Dahlström, Lapuente, and Teorell Citation2012b; Lægreid and Wise Citation2015). Characteristics of the open system include greater flexibility in recruitment and promotion of public officials, a high degree of job mobility between the public and private sector, a focus on selecting the best candidate for each position (i.e. position-based systems), and regulation of public organizations by general labour laws. On the other hand, a closed system entails regulated entry and mobility patterns, a low degree of public and private sector mobility, a focus on formalized entry to the public service, seniority systems, lifetime employment (i.e. career-based systems), and special labour laws that regulate public sector employees (Dahlström, Lapuente, and Teorell Citation2012b; Lægreid and Wise Citation2015; Selden Citation2012). By open/closed civil service systems, we mainly refer to the de facto status of HR practices rather than de jure (Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2017).Footnote1 This is because previous studies report a discrepancy between law and practice in human resource management. For instance, meritocratic laws are often bypassed. Schuster (Citation2017) points out the discrepancy between merit-based civil service management in law and practice, using a comparative data set of 117 countries.

One of the core elements of the classic Weberian bureaucracy entails meritocratic recruitment, tenure protection, the separation of public service careers from private sector careers, and a low degree of mobility between public and private organizations (Byrkjeflot, Du Gay, and Greve Citation2018; Evans and Rauch Citation1999; Gualmini Citation2008). Therefore, the Weberian model is more similar to the closed civil service system than open systems (Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2017). However, in the real world, human resource management practices in many countries have departed from the classic model, adopting more private-sector HR practices and open civil service systems (Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2017; Lægreid and Wise Citation2015). One reason for such variation is that the Weberian model has been challenged by reform efforts which reduce the distinctiveness of public service careers and make public organizations more like private organization, most clearly exemplified by New Public Management (NPM) approaches (Lægreid and Wise Citation2015; Gualmini Citation2008). Several studies have referred to the degree to which bureaucracies are open or closed (Auer, Demmke, and Polet Citation1996; Bekke and Meer Citation2000; Peters Citation2010). However, the data collection effort of a group of researchers at the Quality of Government Institute, Sweden, has enabled researchers to see quantification of characteristics of national bureaucracy covering over 150 countries (Dahlström et al. Citation2015a, Citation2015b), including the degrees of closedness/openness of civil service systems across countries (Please see Dahlström, Lapuente, and Teorell [Citation2012b] for details).

Organizational commitment as work morale and attitudes

This study focuses on organizational commitment as a measurement for the relationship between employees and their organizations. Research on organizational commitment has developed significantly over the past four decades (Becker Citation1960; Meyer and Allen Citation1991; Mowday, Porter, and Steers Citation1982; Porter et al. Citation1974; Salancik Citation1977). Managing organizational commitment by fostering employee morale is a crucial concern for public managers, since higher levels of involvement in that organization’s activities (i.e. high level of organizational commitment) are expected to lead to positive workplace outcomes such as work effort, productivity, and performance (Moldogaziev and Silvia Citation2015). In fact, a substantial body of research has shown that organizational commitment is positively related to work motivation, work effort, productivity, and performance (Anderfuhren-Biget et al. Citation2010; Boardman and Sundquist Citation2009; Caillier Citation2013; Locke Citation1997; Moynihan and Pandey Citation2007; Wright Citation2004).

Results of management studies suggest that organizational commitment is multi-dimensional. According to Allen and Meyer (Citation1990) and Meyer and Allen (Citation1991), organizational commitment can take three forms: (a) affective commitment refers to employees’ emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organization; (b) continuance commitment refers to commitment based on the costs that employees associate with leaving the organization; (c) normative commitment refers to employees’ feelings of obligation to remain with the organization. Specifically, the nature of each form of commitment shows a significantly different effect on employee outcomes.Footnote2

A variety of theoretical explanations have been offered for why organizational commitment occurs, and numerous constructs have been examined as its antecedents. Previous research has shown that commitment can be explained by a broad range of antecedents such as motivational factors, individual factors, organizational culture, managerial level, sector, institutional context, politics and power, political environment and administrative reform, public service motivation, leadership, goal clarity and empowerment, and performance appraisal systems (Dick Citation2011; Moldogaziev and Silvia Citation2015; Moon Citation2000; Park and Rainey Citation2007; Stazyk, Pandey, and Wright Citation2011; Taylor Citation2007; Wilson Citation1999; Yang and Pandey Citation2008). However, individual and organizational variables are the main targets of scholarly interest, resulting in the failure to relate these variables to macro factors such as bureaucratic structure (Egeberg Citation1999). Country-level institutional factors have been relatively overlooked, although some literature has considered cultural factors in the variation of commitment (Fischer and Mansell Citation2009; Meyer et al. Citation2012; Randall Citation1993). Thus, we know little about these differences in the context of public organizations. In particular, the major constraints limiting cross-national studies are lack of data and resources for an extensive data collection process, and more importantly the barriers in getting access to public managers across countries (Chordiya, Sabharwal, and Goodman Citation2017). In particular, while several studies examine cross-national variation in public employees’ attitudes and values (Esteve et al. Citation2017; Fernández-Gutiérrez and Van de Walle Citation2019; Lapuente and Suzuki Citation2017; Jeannot, Van de Walle, and Hammerschmid Citation2018), none of the studies assess the effect of bureaucratic structure on commitment.Footnote3 Thus, despite the large volume of research on organizational commitment and Weberian bureaucracy, the two concepts have seldom been examined together.

Social exchange theory, closed civil service system, and organizational commitment

How can we explain a link between closed/open civil service systems (i.e. their HRM practices and activities) and organizational commitment? We employ social exchange theory as a theoretical framework. Organizational researchers have often used the social exchange concept to explain how an organization’s investments in human resource (HR) activities and the organizational environment will elicit positive work attitudes and behaviour (Gould-Williams Citation2007; Gould-Williams and Davies Citation2005; McClean and Collins Citation2011; Van De Voorde, Paauwe, and Marc Citation2012). According to Blau (Citation1964), social exchange can be defined as ‘voluntary actions of individuals that are motivated by the returns they are expected to bring and typically do in fact bring from others’ (Blau Citation1964, 93). On this basis, employees who positively value HR activities will reciprocate through showing attitudes and behaviours that are valued by the organization (Eisenberger, Fasolo, and Valerie Citation1990; Gould-Williams Citation2007; Van De Voorde, Paauwe, and Marc Citation2012). These employee reactions to HR activities depend on employees’ perceptions of how committed the employing organization is to them (Eisenberger, Fasolo, and Valerie Citation1990; Gould-Williams and Davies Citation2005; Romzek Citation1990; Wayne, Shore, and Liden Citation1997). For instance, Eisenberger, Fasolo, and Valerie (Citation1990) describe that ‘positive discretionary actions by the organization that benefited the employee would be taken as evidence that the organization cared about one’s well-being’ (Citation1990, 51). Therefore, when employees perceive that organizations value and deal equitably with them, they will reciprocate these ‘good deeds with positive work attitudes and behaviors’ (Aryee, Budhwar, and Chen Citation2002, 268; Gould-Williams and Davies Citation2005, 4; Haas and Deseran Citation1981). We argue that, in closed civil service systems, public officials are likely to have such reciprocal relationships or exchanges of obligations between public officials and their organization, which leads to greater employee commitment.

HR activities in a closed system and continuance commitment

First, we expect a positive relationship between closed systems and continuance commitment. Based on social exchange theory, we argue that HR practices and activities in closed systems produce more reciprocal relationships between public organizations and officials than open systems do, which lead to greater continuance commitment. In a closed system, public officials typically spend their entire career in the public sector and invest their time and resources acquiring public-sector specific skills and knowledge. Outside employment opportunities are typically limited, thus public officials may sense fewer viable alternatives or side benefits in a closed system. On the other hand, open systems feature career mobility of public officials who switch between public and private sectors, more diverse and flexible access to the public sector, and less distinction between the public and the private.

According to Becker (Citation1960), Allen and Meyer (Citation1990), and Meyer et al. (Citation2002), the magnitude and number of side benefits that employees recognize, including retirement funds and medical benefits, positively affect continuance commitment. Furthermore, the lack of employment alternatives also increases the perceived costs associated with leaving the organization. The fewer viable alternatives that employees believe are available, the stronger will be their continuance commitment to their current employer. We argue that a number of HR practices grounded in closed systems such as tenure protection, seniority rule, employee benefits such as retirement fund and superior health-care plans, and public-sector specific knowledge and skills produce a greater sense of obligation in civil servants to remain in their organization. Moreover, we also hypothesize that if employees perceive a lack of career alternatives and incurred sunk costs, they would want to give in return to their organization, leading to increased continuance commitment. Thus, we argue that HR activities and customs in closed systems are likely to enhance public officials’ perceptions of the benefits they receive from their organizations and associated costs of leaving their organization, which are returned by civil servants’ positive continuance commitment:

Hypothesis 1: A closed bureaucratic structure is positively associated with senior public sector managers’ continuance commitment.

HR activities in a closed system and normative commitment

Secondly, we expect that closed systems are also positively associated with normative commitment. Closed systems include lifelong tenure, and a high degree of internal homogeneity in employees’ educational background and professional skills. Typically, once public officials enter the public sector, they remain in the public sector for the rest of their career. Job mobility between public and private sectors is limited. On the other hand, open systems usually include more job mobility between public and private organizations, and more diversity in employees’ educational and career background.

Allen and Meyer (Citation1990) have proposed that employees may develop a sense of moral obligation toward the organization through organizational socialization. Organizational socialization refers to the process by which individuals learn what they believe most others in the organization will actually do (Van Vugt and Hart Citation2004). Through this process, employees acquire knowledge about the adjustment to new jobs, roles, workgroups, and the culture of the organization in order to participate better as an organizational member (Haueter, Macan, and Winter Citation2003; Saks and Ashforth Citation1997; Cohen and Veled-Hecht Citation2010). We argue that closed systems are more likely to produce normative commitment than open systems do, for a number of reasons, through the organizational socialization process. First, unlike open systems, closed systems tend to have a high degree of internal homogeneity among employees, which stems from similar educational background and professional skills. Such similarity in educational and career backgrounds engenders and fosters collegiality or esprit de corps (Barberis Citation2011; Peters Citation2010). Through the socialization process, public officials in closed systems develop such esprit de corps, which leads to a normative obligation to remain in their organization. Second, closed systems tend to need a high degree of loyalty to the organization, which comes from the high degree of political loyalty expected in a traditional bureaucratic system. Therefore, through the socialization process, civil servants may produce a sense of moral obligation to the organization in closed systems.

Employing social exchange theory, we argue that if civil servants perceive this loyalty norm and a high degree of internal homogeneity in closed system they are more likely to reciprocate with a strong sense of moral obligation to the organization as a positive normative commitment. Thus, our second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2: A closed bureaucratic structure is positively associated with senior public sector managers’ normative commitment.

HR activities in a closed system and affective commitment

Finally, we expect that closed systems are also associated with affective commitment. Meyer and Allen (Citation1987) have pointed out that work experiences such as organizational support or perceptions of justice provide the strongest evidence for affective commitment. Those experiences fulfil employees’ psychological needs and make them feel comfortable within the organization and competent in their work-role. We argue that the organizational support received and perceptions of justice made by public officials in closed systems are likely to produce more affective commitment via social exchange.

Formalized systems with formal rules and regulated career recruitment and promotion systems are significant components of closed systems. For instance, theoretically, in highly formalized systems, little flexibility exists in determining how a decision is made or what outcomes are due in a given situation; procedures and rewards are dictated by the rules (Schminke, Ambrose, and Cropanzano Citation2000, 96). We expect that this should contribute to an individual’s confidence that he/she is being treated the same as others in similar situations, as the rules are well documented and well known (ibid). Additionally, bureaucratic structures and processes with formal rules such as meritocratic recruitment are especially meant to support professionals’ autonomy (Diefenbach and Sillince Citation2011, 1522–1523). Thus, we can assume that employees in closed systems should have more psychological support in the organization than employees in open systems. Thus, using a social exchange framework, employees who perceive a high level of organizational support in a closed system are more likely to feel an obligation to ‘repay’ the organization in terms of affective commitment (Eisenberger et al. Citation1986). Thus, we expect that creating HR activities in closed systems (i.e., hierarchical bureaucratic structures with formal rules and regulated career recruitment and promotion systems) would enhance civil servants’ perceptions of being valued equitably, supported, and cared for by reciprocating with positive affective commitment. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: A closed bureaucratic structure is positively associated with senior public sector managers’ affective commitment.

Data and methods

Little comparative research has been done in the study of public administration and bureaucracy (Dahlström, Lapuente, and Teorell Citation2012b; Eglene and Dawes Citation2006; Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2011). One reason for the scarcity has been the lack of systematic data on both bureaucratic structures and civil servants’ attitudes. This study aims to bridge this gap in the literature with two unique cross-national data sets. The first one is the COCOPS Executive Survey on Public Sector Reform in Europe (Hammerschmid Citation2015), which contains the survey answers of 9,333 senior public sector executives from 21 European countries. The second data set is the QoG Expert Survey Dataset II (Dahlström et al. Citation2015a), which captures characteristics of national bureaucratic structures constructed from the opinions of over 1,200 country experts. In this study, we combine these two data sets. Independently, both the COCOPS survey and the QoG Expert Survey data have been used in many academic publications.Footnote4 The empirical novelty of this study is combining these two data sets. Using these data sets is appropriate for our research question in several ways. First, the COCOPS survey was conducted to collect data on public officials’ value preferences and work attitudes, including their organizational commitment. Thus, its purpose fits our research interest. Second, the survey was ‘a response to the observed lack of rigorous quantitative comparative research into public administration reforms in Europe’ (Jeannot, Van de Walle, and Hammerschmid Citation2018, 5). Thus, it serves our purpose of advancing the field of empirical comparative public management. Thirdly, the QoG Expert Survey provides crucial information on a variety of bureaucratic structures across countries. Finally, by combining two different data sets, we can avoid a common source bias issue (George and Pandey Citation2017; Jakobsen and Jensen Citation2015) because our dependent and independent variables are not from the same data set.

Between 2012 and 2015 the COCOPS project administered its Executive Survey, in order to quantitatively assess the impact of NPM-style reforms in European countries (Hammerschmid, Oprisor, and Štimac Citation2013). The cross-national survey captured the experiences and perceptions of public-sector executives with respect to the current status of management, coordination and administrative reforms, as well as to gauge the effect of NPM-style reforms on performance, and the impact of the financial crisis. Designed by an international team of public administration researchers, it provides a comprehensive census of both central government ministries and agencies as well as state and regional administrations in the target countries while avoiding random sampling and response bias issues.Footnote5 Twenty-one countries were surveyed, targeting 36,892 senior-level managers; the countries included were: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. However, due to missing data, we exclude Poland, leaving 20 countries in our data set. After data cleaning, there were 9,333 responses reflecting a 25.3% response rate. Compared to similar online surveys, the response rate is relatively high. However, the sample cannot be considered as representative of the distribution of top-level officials within and among ministries and agencies. Nonetheless, as Bezes and Jeannot (Citation2018, 7) argue, ‘the diversity of our responses is, on average, [satisfying], both for the distribution between central administrations in ministries and agencies and for policy sectors.’ In addition, the data set provides crucial source of information on understudied cross-national variation in senior officials’ attitudes and preferences. Therefore, while being aware of the above limitation, it is preferable to advance the field with currently available data rather than waiting for ideal data set.

The QoG Expert Survey offers quantitative data for the study of Weberian bureaucracy, which has hitherto been neglected by empirical analysis (Dahlström, Lapuente, and Teorell Citation2010). Based on the innovative work of mapping bureaucratic structures in 35 less-developed countries conducted by Peter Evans and James Rauch (Rauch and Evans Citation2000; Evans and Rauch Citation1999), the first survey was taken by researchers at the QoG Institute in 2008–2012, culminating in their first data set (Teorell, Dahlström, and Dahlberg Citation2011). Their second survey – the Expert Survey II – was undertaken in 2014 and received 1,294 responses from experts in 159 countries. The survey elicited experts’ perceptions of their country’s public bureaucracy, including views on bureaucratic structures such as recruitment and career systems, policies concerning replacement and compensation, procedures for policy-making and implementation, gender representation, and the level of transparency. We used information from the second QoG Expert Survey regarding employment systems in the current research.

Dependent variable

This study utilizes an organizational commitment variable created as an index from the COCOPS survey items that aims to measure public managers’ three forms of organizational commitment. Our dependent variable depends on the respondents agreement or disagreement with the following seven statements: 1) ‘I feel valued for the work I do;’ 2) ‘I would recommend it as a good place to work;’ 3) ‘I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own;’ 4) ‘I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization;’ 5) ‘It would be very hard for me to leave my organization right now, even if I wanted to;’ 6) ‘I was taught to believe in the value of remaining loyal to one organization;’ 7) ‘Things were better in the days when people stayed with one organization for most of their career.’ Following Caillier (Citation2013), Meyer and Allen (Citation1991), and Moldogaziev and Silvia (Citation2015), we measured three types of commitment, namely affective commitment from items 1–2, continuance commitment from 4, 5, 6, and 7, and normative commitment from 3. Affective commitment is a mean value of answers for survey items 1–2 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75), and continuance commitment are the mean values of items 4–7 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.69). As for the normative commitment, we use the original scale (ordinal from 1 to 7) of the answer for item 3. Since none of these commitment variables take values lower than 0 or greater than 7, we treat them as truncated dependent variables.

Independent variables

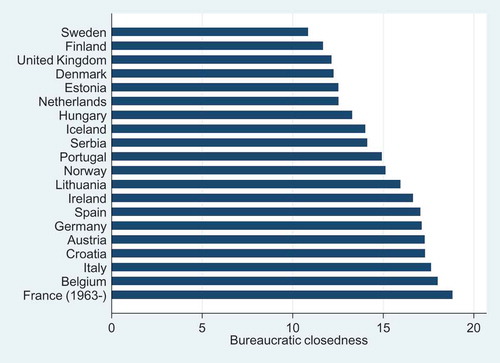

We use the QoG Expert Survey Dataset II to capture how closed the employment system is. This is an aggregate measure, and this variable has been used in previous research (Dahlström, Lapuente, and Teorell Citation2012a; Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2017). Following the existing literature, this index is created based on a principal component analysis (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75) of the following three questions: (1) ‘Public sector employees are hired via a formal examination system;’ (2) ‘Once one is recruited as a public sector employee, one remains a public sector employee for the rest of one’s career;’ and (3) ‘The terms of employment for public sector employees are regulated by special laws that do not apply to private sector employees.’ The higher the value, the more isolated, or ‘closed,’ public employees are from the practices of the private sector. shows the variation in the closed/open nature among our sample of 20 European countries. Countries such as France, Belgium, Italy, Croatia, Austria, Germany, and Spain have relatively closed systems, in which entry into a public service career is restricted through formalized exams, public employees enjoy lifetime tenure protection, and special labour regulations are applied to public sector employees. On the other hand, bureaucrats in countries such as Sweden, Finland, United Kingdom, Denmark, Estonia, and the Netherlands work in more open civil service systems.

Figure 1. Variations in the degree of closedness in civil service systems. Source: Created from the QoG expert survey dataset II (Dahlström et al. Citation2015a)

Control variables

We also control for other factors that are expected to influence organizational commitment. The relatively small number of countries (N = 20) does not allow us to include a large number of country-level controls. Therefore, we limit the number of controls to significant factors that may affect our dependent variables and test them in different models. Control variables, which are expected to influence dependent variables, are selected based on previous literature. The models include GDP per capita (2011–15 mean values, logged) as a country level control from the QoG Standard Dataset (Teorell et al. Citation2017). Results of previous studies suggest that levels of economic development are negatively associated with affective and normative commitment (Fischer and Mansell Citation2009). Previous research has also identified country culture as a significant predictor for commitment (Fischer and Mansell Citation2009; Meyer et al. Citation2012; Randall Citation1993). Therefore, we use national cultural factors from Hofsted’s dimension of cultural values, namely power distance and individualism-collectivism (Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov Citation2010) as additional country-level control variables. Following previous studies (Steyrer, Schiffinger, and Lang Citation2008; Avolio et al. Citation2004; Ang, Van Dyne, and Begley Citation2003; Mathieu and Zajac Citation1990), we control for the following individual-level factors that may affect commitment: gender, organizational type (ministry or agency/other), organizational size, respondent’s current position, age, years of experience in current organization, private sector experience, educational level, degree of job autonomy, organizational social capital, job satisfaction, and organizational goal clarity. All of these variables are collected or created from the COCOPS survey dataset. in the Appendix presents descriptive statistics of all variables in the analysis. We conducted collinearity diagnostics using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) based on our main models. Mean values of VIF are less than 1.49 in all main models (model 2 in ). The highest individual VIF score for individual variables is 1.77 (age). These results suggest that the models do not have serious multicollinearity issues. in the Appendix reports the correlation matrix.

Table 1. Multilevel models measuring senior public managers’ organizational commitment.

Table 1A. Descriptive statistics.

Table 2A. Correlation Matrix.

Empirical strategy

Our dataset has a hierarchical structure, with public sector managers (level 1) nested in country-level factors (level 2), and thus multilevel analysis seems to be an appropriate method (Jones Citation2008). We assume that intercepts of individual-level variables can vary across countries due to the country-level factors, therefore a random intercept model is applied. Since the main dependent variables are censored continuous variables of mean values of survey items ranging from 1 to 7, we employ multilevel mixed-effects tobit regression models. As for the normative commitment variable, we utilize multilevel-ordered logit models as the variable is in ordinal form from 1 to 7. The first model includes only individual-level independent and control variables. The second model adds a country-level control variable and the independent variable. In our robustness check models (models 3–8), we use a different set of country-level controls, including power distance and individualism (from Hofsted’s dimension of cultural values), competitive salary in the public sector, administrative burden, corruption perception index (public officials/civil servants), and polity score.

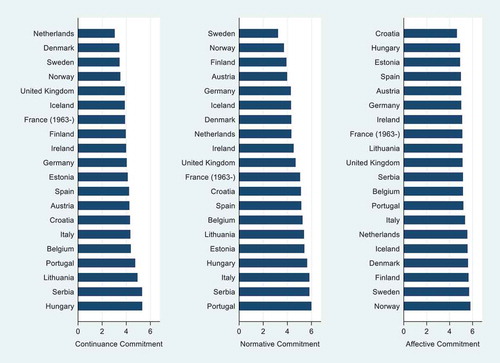

Descriptive results: cross-national variation in organizational commitment

We present cross-national variation in levels and forms of commitment prior to the main regression results. shows the variation in country mean values of all three types of commitment across our sample countries. It is notable that countries ranked high or low in terms of commitment values differ depending on types of commitment. For instance, Hungary, Serbia, Lithuania, Portugal, Belgium, Italy, and Croatia score high in continuance commitment. On the other hand, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and UK score low. Country orders in the normative commitment show a similar trend. Affective commitment seems to have a negative relationship with continuance and normative commitment (correlation coefficients between CC and AC = −0.58 with p = 0.008 and CC and NC = −0.59 with p = 0.007). Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and Iceland show higher affective commitment, while Croatia, Hungary, Estonia, and Spain exhibit lower commitment. These results suggest that our sample exhibits cross-national variation in levels and forms of commitment.

Figure 2. Country comparison of mean values of organizational commitment by commitment type. Source: Created from the COCOPS Executive Survey on Public Sector Reform in Europe (Hammerschmid Citation2015)

Having shown the variation, we now turn to results of the multilevel analysis. Results of the multilevel tobit regression models are reported in for the three types of commitment. Results suggest that closed bureaucracies are positively and statistically significantly associated with continuance commitment and normative commitment. However, the link between closed bureaucracy and affective commitment is positive but not statistically significant. In closed systems, senior public officials show higher level of continuance and normative commitment than those in more open systems, holding other factors fixed. Thus, senior public officials in more closed systems show more commitment to their organizations based on the side benefits and costs of leaving and feelings of obligation to remain with the organization than those in more open systems. This confirms our hypotheses 1 and 2, but not hypothesis 3. It is notable that results show that all forms of commitment are not associated with the closed systems, only continuance and normative commitment. In fact, this result is consistent with existing literature that attitudes to continue membership of an organization for economic benefits or out of norm-based obligations may not necessarily coincide with higher affective commitment or loyalty towards the organization (Chordiya, Sabharwal, and Goodman Citation2017; Solinger, Van Olffen, and Roe Citation2008; Stazyk, Pandey, and Wright Citation2011). Results of our robustness check models (see ) also show the same results (positive impact of closed systems on normative and continuance commitment, but not affective commitment).

Table 2. Results from multilevel model estimates: using additional country-level controls.

Results of analysis also offer other significant results that deserve attention. Being a female manager, compared to a male manager, is negatively associated with continuance commitment (p < 0.01) and normative commitment (p < 0.1). Compared to male officials, female officials are likely to exhibit lower continuance and normative commitment. However, we do not find any statistically significant link between gender and affective commitment. A previous meta-analysis using all correlations indicated that women tend to be more committed than men, while it illustrated a slightly stronger relationship between women and affective commitment (Mathieu and Zajac Citation1990). Our present study shows no statistically significant association between women and affective commitment. Organizational type also affects the degree of commitment. Compared to senior officials working for a ministry, those in an agency or other types of organization tend to show more commitment to their organization in the form of continuance and normative commitment (p < 0.01), holding other factors constant. However, the level of affective commitment is not statistically associated with types of organizations. Age also has positive link with continuance and normative commitment (p < 0.01). Previous meta-analysis shows that age was significantly more related to affective commitment than to normative commitment (Mathieu and Zajac Citation1990). In our study, older officials tend to have more commitment based on side benefits or normative obligation to remain in the organization than younger officials. The positive relationship between working years at the current organization and continuance commitment is also found (p < 0.01). The longer officials work for the same organization, the more continuance commitment they are likely to exhibit. This is consistent with previous studies as organizational tenure tended to be more positively related to normative commitment (Mathieu and Zajac Citation1990). In our study, years spent in the same organization are likely to yield greater side benefits, such as a pension plan, and develop greater continuance and normative commitment. With respect to private sector experience of managers, those managers having less than 5 years of private sector experience or more than 5 years of private sector experience exhibit higher normative commitment than those without private sector experience (p < 0.01).Footnote6 Education level is negatively associated with continuance and normative commitment. Compared to senior officials who completed a bachelors-level degree, those who completed master-level education show lower continuance commitment (p < 0.01). Those who completed PhD-level education exhibit lower continuance (p < 0.01) and normative commitment (p < 0.05). Therefore, education negatively affects these forms of commitment. This inverse relationship result is consistent with previous meta-analysis results (Mathieu and Zajac Citation1990). In this research, we found that more educated civil servants would have higher expectations that the organization may be unable to meet and have a greater number of job options, and are less likely to become entrenched in any one position or organization (Mowday, Porter, and Steers Citation1982; Mathieu and Zajac Citation1990; Meyer and Parfyonova Citation2010). Organizational factors such as organizational social capital and goal clarity have a positive association with all forms of commitment (p < 0.01). Also, job autonomy is positively related to normative and affective commitment (p < 0.01) and job satisfaction has a positive link with all forms of commitment (p < 0.01).

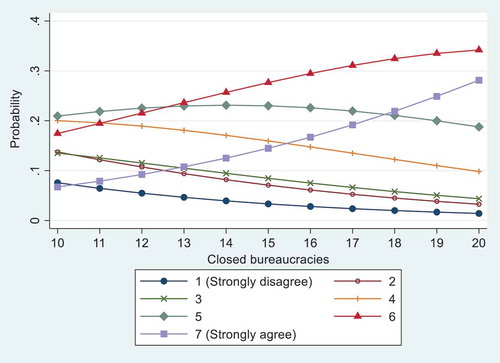

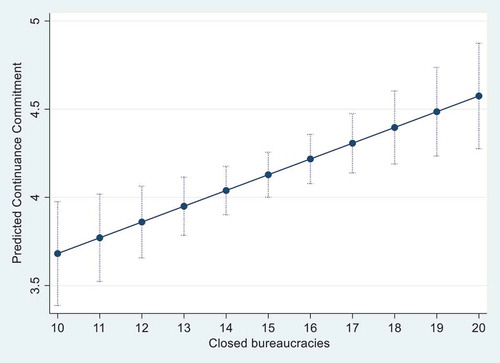

Visualizing predicted probabilities help to interpret the results of the multilevel-ordered logit model. illustrates the predicted probabilities for outcomes 1 (strongly disagree)-7(strongly agree) concerning normative commitment (model 2 in ). As seen from the figure, the probability of selecting outcome 7 or 6, which shows greater normative commitment, increases as the degree to which bureaucracies are closed increases. The probability of selecting outcome 7 is above 30% when the closedness value is higher than 17, which is around Spain’s closedness value (17.04). The probability of picking low levels of normative commitment such as outcomes 1–3 are relatively higher when the closedness bureaucracy variable is low (i.e. open civil service systems). On the other hand, these probabilities drop as the degree of closedness increases. In other words, senior public officials in more closed systems are less likely to show lower normative commitment than those in more open systems. This gives empirical support for H2. shows predicted values of continuance commitment as the degree of closed service systems varies. Recall that continuance commitment is a censored continuous variable, that is created from separate survey items, ranging from 1 to 7. These values are calculated based on model 2 in . Holding other factors at mean, a higher degree of bureaucratic closedness increases senior public managers’ continuance commitment. Senior public officials working in more closed civil service systems are more likely to have higher continuance commitment than those working in more open systems.

Figure 3. Predicted normative commitment by degree of closed bureaucracy*.

*Samples are based on model 2 for normative commitment in .

Figure 4. Predicted continuance commitment by degree of closed bureaucracy*.

*Samples are based on model 2 for continuance commitment in .

In sum, the results of our multilevel models show that characteristics of employment systems of civil servants matter for levels of some types of organizational commitment even after controlling for several significant country-level factors such as culture, administrative conditions, and political factors. There are strong empirical positive associations between closed systems and higher levels of continuance and normative commitment. However, we do not find any empirical link between closed systems and affective commitment.

We ran robustness check models with additional control variables. Those additional variables include country cultures (power distance and individualism from Hofsted’s dimension of cultural values), competitive salary in the public sector, administrative burden, corruption perception index (public officials/civil servants), and polity score. The coefficients of closed bureaucracy are robust across models with different country controls as seen in . A closed bureaucracy has a positive empirical association with continuance commitment (p < 0.01) and normative commitment (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05), holding other variables at mean. Affective commitment is not statistically significantly associated with closed bureaucracy. These results demonstrate the robustness of our results.

Discussion and conclusions

Bureaucratic structure plays a large role in shaping public policies, their implementation, and the related socioeconomic outcomes. The effect of the different characteristics of civil service systems on employee work attitudes is an important empirical question. This study presents evidence on this broad question using cross-national comparative data sets. We have argued that closed civil service systems are associated with higher levels of continuance, normative, and affective commitment via social exchange. Senior public managers in a more closed bureaucracy should show higher levels of continuance commitment due to the perceived costs associated with leaving and the number of alternative options outside the public sector. Public officials in closed systems should also have greater normative commitment because they feel that organizations expect their loyalty and because of the high degree of internal homogeneity. Finally, closed systems should be also associated with greater affective commitment because of higher perceived organizational support, justice, and equal treatment. After controlling for significant individual and country level factors, results of multilevel analysis suggest that only continuance and normative, but not affective commitment, are associated with the type of civil service system.

Results of this study suggest the importance of looking at individual bureaucrats for broader outcomes. As results of this study show, civil servant work morale varies not only among individuals but also among countries with different bureaucratic structures. Civil servants in closed systems are more committed to their organization than those in more open systems. However, the types of commitment are not the same. Bureaucrats in closed systems have higher continuance and normative commitment than those in the open systems. What does this result imply? Although our current studies cannot directly connect these commitment differences with macro-level outcomes, future study should explore consequences of organizational commitment in more macro-outcomes. Results reported in previous good governance studies suggest that the Weberian bureaucratic structure is one of the primary predictors for favourable country-level outcomes. How does organizational commitment of civil servants play a role in these outcomes? As Meyer and Parfyonova (Citation2010) argue, benefits of organizational commitment are not equal among different types of commitment. Empirical results of some studies suggest a positive link between affective commitment and perceived performance and quality of work (Park and Rainey Citation2007), organizational ethical climate (Erben and Güneşer Citation2008), whistle-blowing attitudes when combined with transformational leadership (Caillier Citation2015), and innovative attitudes (Jafri Citation2010; Xerri and Brunetto Citation2013). On the other hand, previous studies have not yet found a strong link between continuance or normative commitment and good outcomes such as innovativeness, ethical behaviour, and acceptance of organizational change. Future studies should undertake to discover how different levels and types of commitment of bureaucrats are connected to country-level differences such as innovativeness, government effectiveness, and corruption level.

Results of this study also shed light on potential positive aspects of closed civil service systems. Previous studies have shown that closed civil service systems are not linked with favourable outcomes such as government effectiveness, lower levels of corruption, and innovative administration (Dahlström and Lapuente Citation2017). In addition, reform efforts, particularly those associated with the New Public Management approach, have further cast doubt on the effectiveness of the traditional civil service system, pushing to reduce the distinction between public and private careers and to make public organizations more like private ones. However, results of our study show that civil servants in more closed systems have higher levels of commitment to their organization than those in more open systems. As we discussed, organizational commitment is an important determinant of individual performance and an organizations’ success and well-being. Therefore, it is reasonable to deduce from our study that having a sense of working under hierarchical bureaucratic structures with formal rules, tenure protection, seniority, regulated career recruitment and promotion systems would strengthen civil servant’s commitment to the organization (especially, higher continuance and normative commitment as suggested by the current study) which, in turn, could lead to greater job performance and government effectiveness. Thus, while the Weberian model of bureaucracy has been challenged by the NPM reform efforts, it is still important to reassess positive aspects of the classic model in the NPM and post-NPM era.

There are, of course, limitations associated with our study. First, due to the unavailability of data, our study does not consider intra-country variation. Even within the same country, hiring and promotion practices may differ across government organizations. Although we include several organization-related variables such as organizational size, organizational level of social capital, and organizational goal clarity in our model, the COCOPS data set does not allow us to implement three-level multilevel analysis (country-organization-individual). Thus, future studies should be conducted to consider such intra-country variations and organizational-level differences as data becomes available. Secondly, our study focuses on top-level executives, not street-level or mid-level bureaucrats. The association between closed systems and commitment that we have identified might be different for lower level civil servants. Therefore, we stress that results of this study cannot be generalizable for different levels of bureaucrats. Thirdly, survey response rate of the COCOPS survey and country selection are also a limitation of this research. Our samples only include European countries. Even though these European countries still have variations as shown in the literature on the public administration tradition (Painter and Peters Citation2010), obviously bureaucratic structures that are grounded in other traditions such as East Asia, Latin America, or Middle Eastern countries are not included in our analysis. We do not claim generalization from our findings.

Relatedly, we advise that future research should examine the relevance of potential mediator or moderator variables on the relation between civil service systems and organizational commitment. Specifically, one may wonder whether the moderating effects of an employment system of a national bureaucracy and organizational commitment would have been even stronger if the data which was collected had included information such as professional identification, lack of employment alternatives, and organizational socialization. Hence, future research might explore additional contextual factors in these relationships. Finally, future research should consider sector differences in employees’ commitment. We built our theoretical framework based on social exchange theory and organizational commitment, which are grounded in the literature of private sector management. However, as previous research suggests, employee organizational commitment differs between private and public employees depending on the organizational context and environment (Baldwin Citation1990; Boyne Citation2002; Fletcher and Williams Citation1996; Markovits et al. Citation2010; Odom, Randy Boxx, and Dunn Citation1990; Rainey Citation2014). Employees in the public and private sectors experience different working conditions and employment relationships. Therefore, theories built on the private sector management research may need some modification in future research. Despite these limitations, this study shows how senior public managers’ commitment and their work morale can be associated with bureaucratic structure. As Van de Walle et al. (Citation2016) argue, scholars are still in the early stages of data collection efforts for comparative bureaucratic research. Future research should undertake these abovementioned tasks as the data becomes available.

Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank Carl Dahlström and Victor Lapuente at the Quality of Government Institute for their valuable and helpful comments on our earlier drafts of our manuscript. We also received helpful suggestions from other members of the Quality of Government Institute and panel discussants and participants at the annual conferences of American Political Association, Midwest Political Science Association, European Consortium for Political Research, and International Research Society for Public Management. We also thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kohei Suzuki

Kohei Suzuki is an assistant professor at Institute of Public Administration, Leiden University, the Netherlands. He obtained his Ph.D. in Public Policy from the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University, Bloomington. He mainly studies administrative reform and bureaucratic structures with a focus on cross-national settings and Japanese local municipalities. Please see his website for his recent work.

Hyunkang Hur

Hyunkang Hur is an assistant professor at the Department of Public Administration and Health Management, Indiana University, Kokomo. He obtained his Ph.D. in Public Affairs from the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University, Bloomington. His research focuses on human resource management and organizational commitment of civil servants.

Notes

1. We appreciate an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

2. Previous meta-analytic reviews demonstrate that affective and normative commitment are positively correlated with job performance and organizational citizenship behaviour, while continuance commitment is negatively correlated with job performance and unrelated to organizational citizenship behaviour (Meyer et al. Citation2002). Additionally, in terms of turnover, absenteeism, and stress and work-family conflict consequences, the correlations between the three commitment scales and turnover were all negative, while only affective commitment was found to be negatively related to absenteeism; however, continuance commitment is positively correlated with absenteeism, stress, and work-family conflict (Meyer et al. Citation2002). Thus, results of previous meta-analyses suggest that affective commitment is most strongly tied with job performance and other employee outcomes followed by normative and continuance commitment in turn. In particular, continuance commitment has often been found to be unrelated or negatively related to those employee behaviour outcomes (Meyer et al. Citation2002).

3. A study by Andrews, Hansen, and Huxley (Citation2018) examines organizational commitment across European countries; however, their focus is effects of private sector experience on commitment, not the relationship between bureaucratic structures and commitment.

4. For the COCOPS survey, see, for example, Andrews (Citation2017), Andrews, Beynon, and Aoife (Citation2019), Bezes and Jeannot (Citation2018), Hammerschmid, Van de Walle, and Stimac (Citation2013), Hammerschmid et al. (Citation2016), Ongaro, Ferré, and Fattore (Citation2015), Raudla et al. (Citation2015), Raudla et al. (Citation2017), Van der Voet and Steven (Citation2015). For the QoG Expert Survey, see Boräng, Nistotskaya, and Xezonakis (Citation2017), Charron, Dahlström, and Lapuente (Citation2016), Cho et al. (Citation2013), Cornell (Citation2014), Cornell and Grimes (Citation2015), Dahlström and Lapuente (Citation2017), Fernández-Carro and Lapuente-Giné (Citation2016), Gustavson and Aksel (Citation2016), Kopecký et al. (Citation2016), Nistotskaya and Cingolani (Citation2016), Sundell (Citation2014), Schuster (Citation2016), Suzuki and Demircioglu (Citation2018), Van de Walle et al. (Citation2016), Versteeg and Ginsburg (Citation2017), Van de Walle, Steijn, and Jilke (Citation2015).

5. Within central government ministries, the top two administrative levels are included in the target. For central government agencies, the survey targets the first two executive levels. State-owned enterprises and audit courts are excluded. Appropriate regional and state government ministries and agencies are included in order to maximize the number of senior executives reached. However, local government bodies and local service delivery organizations are not included (Hammerschmid, Oprisor, and Štimac Citation2013).

6. This result is not comparable with the results of Andrews, Hansen, and Huxley (Citation2018) because their work operationalizes the ratio of private sector experience to public sector experience and also includes different control variables.

References

- Allen, N. J., and J. P. Meyer. 1990. “The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment to the Organization.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 63 (1): 1–18.

- Anderfuhren-Biget, S., F. Varone, D. Giauque, and A. Ritz. 2010. “Motivating Employees of the Public Sector: Does Public Service Motivation Matter?” International Public Management Journal 13 (3): 213–246.

- Andrews, R. 2017. “Organizational Size and Social Capital in the Public Sector: Does Decentralization Matter?” Review of Public Personnel Administration 37 (1): 40–58.

- Andrews, R., J. R. Hansen, and K. Huxley. 2018. “Senior Public Managers’ Organizational Commitment: Do Private Sector Experience and Tenure Make a Difference?” International Public Management Journal. doi:10.1080/10967494.2019.1580231

- Andrews, R., M. J. Beynon, and M. Aoife. 2019. “Configurations of New Public Management Reforms and the Efficiency, Effectiveness and Equity of Public Healthcare Systems: A Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis.” Public Management Review. doi:10.1080/14719037.2018.1561927.

- Ang, S., L. Van Dyne, and T. M. Begley. 2003. “The Employment Relationships of Foreign Workers versus Local Employees: A Field Study of Organizational Justice, Job Satisfaction, Performance, and OCB.” Journal of Organizational Behavior: the International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 24 (5): 561–583.

- Aryee, S., P. S. Budhwar, and Z. X. Chen. 2002. “Trust as a Mediator of the Relationship between Organizational Justice and Work Outcomes: Test of a Social Exchange Model.” Journal of Organizational Behavior: the International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 23 (3): 267–285.

- Auer, A., C. Demmke, and R. Polet. 1996. Civil Services in the Europe of Fifteen: Current Situation and Prospects. Maastricht: European Institute of Public Administration.

- Avolio, B. J., W. Zhu, W. Koh, and P. Bhatia. 2004. “Transformational Leadership and Organizational Commitment: Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment and Moderating Role of Structural Distance.” Journal of Organizational Behavior: the International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 25 (8): 951–968.

- Baldwin, J. N. 1990. “Public versus Private Employees: Debunking Stereotypes.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 11 (1–2): 1–27.

- Barberis, P. 2011. “The Weberian Legacy.” In International Handbook on Civil Service Systems, edited by A. Massey, 13–30. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Becker, H. S. 1960. “Notes on the Concept of Commitment.” American Journal of Sociology 66 (1): 32–40.

- Bekke, A. J. G. M., and F. M. Meer. 2000. Civil Service Systems in Western Europe. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bezes, P., and G. Jeannot. 2018. “Autonomy and Managerial Reforms in Europe: Let or Make Public Managers Manage?” Public Administration 96 (1): 3–22.

- Blau, P. M. 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley.

- Boardman, C., and E. Sundquist. 2009. “Toward Understanding Work Motivation: Worker Attitudes and the Perception of Effective Public Service.” The American Review of Public Administration 39 (5): 519–535.

- Boräng, F., M. Nistotskaya, and G. Xezonakis. 2017. “The Quality of Government Determinants of Support for Democracy.” Journal of Public Affairs 17: 1–2.

- Boyne, G. A. 2002. “Public and Private Management: What’s the Difference?” Journal of Management Studies 39 (1): 97–122.

- Byrkjeflot, H., P. Du Gay, and C. Greve. 2018. “What Is the ‘Neo-Weberian State’as a Regime of Public Administration?” In The Palgrave Handbook of Public Administration and Management in Europe, edited by E. Ongaro and S. Van Thiel, 991–1009. London, UK: Springer.

- Caillier, J. G. 2013. “Satisfaction with Work-Life Benefits and Organizational Commitment/Job Involvement: Is There a Connection?” Review of Public Personnel Administration 33 (4): 340–364.

- Caillier, J. G. 2015. “Transformational Leadership and Whistle-Blowing Attitudes: Is This Relationship Mediated by Organizational Commitment and Public Service Motivation?” The American Review of Public Administration 45 (4): 458–475.

- Charron, N., C. Dahlström, and V. Lapuente. 2016. “Measuring Meritocracy in the Public Sector in Europe: A New National and sub-National Indicator.” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 22 (3): 499–523.

- Charron, N., C. Dahlström, V. Lapuente, and M. Fazekas. 2017. “Careers, Connections, and Corruption Risks: Investigating the Impact of Bureaucratic Meritocracy on Public Procurement Processes.” The Journal of Politics 79 (1): 89–104.

- Cho, W., I. Tobin, G. A. Porumbescu, H. Lee, and J. Park. 2013. “A Cross-Country Study of the Relationship between Weberian Bureaucracy and Government Performance.” International Review of Public Administration 18 (3): 115–137.

- Chordiya, R., M. Sabharwal, and D. Goodman. 2017. “Affective Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction: A Cross-National Ocmparative Study.” Public Administration 95 (1): 178–195.

- Christensen, J. G. 2012. “Pay and Prerequisites for Government Executives.” In The SAGE Handbook of Public Administration, edited by B. G. Peters and J. Pierre, 102–129. London, UK: SAGE.

- Cohen, A., and A. Veled-Hecht. 2010. “The Relationship between Organizational Socialization and Commitment in the Workplace among Employees in Long-Term Nursing Care Facilities.” Personnel Review 39 (5): 537–556.

- Cornell, A. 2014. “Why Bureaucratic Stability Matters for the Implementation of Democratic Governance Programs.” Governance 27 (2): 191–214.

- Cornell, A., and M. Grimes. 2015. “Institutions as Incentives for Civic Action: Bureaucratic Structures, Civil Society, and Disruptive Protests.” The Journal of Politics 77 (3): 664–678.

- Dahlberg, S., and S. Holmberg. 2014. “Democracy and Bureaucracy: How Their Quality Matters for Popular Satisfaction.” West European Politics 37 (3): 515–537.

- Dahlström, C., V. Lapuente, and J. Teorell. 2012a. “The Merit of Meritocratization: Politics, Bureaucracy, and the Institutional Deterrents of Corruption.” Political Research Quarterly 65 (3): 656–668.

- Dahlström, C., V. Lapuente, and J. Teorell. 2012b. “Public Administration around the World.” In Good Government: The Relevance of Political Science, edited by S. Holmberg and B. Rothstein, 40–67. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Dahlström, C., J. Teorell, S. Dahlberg, F. Hartmann, A. Lindberg, and M. Nistotskaya. 2015a. The QoG Expert Survey Dataset II. Gothenburg, Sweden: Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg.

- Dahlström, C., J. Teorell, S. Dahlberg, F. Hartmann, A. Lindberg, and M. Nistotskaya. 2015b. The QoG Expert Survey II Report. QoG Working Paper Series 2015:9. Gothenburg, Sweden: Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg.

- Dahlström, C., and V. Lapuente. 2017. Organizing the Leviathan: How the Relationship between Politicians and Bureaucrats Shapes Good Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dahlström, C., V. Lapuente, and J. Teorell. 2010. Dimensions of Bureaucracy: A Cross-National Dataset on the Structure and Behavior of Public Administration. QoG Working Paper Series 2010:13. Gothenburg, Sweden: Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg.

- Dick, G. P. M. 2011. “The Influence of Managerial and Job Variables on Organizational Commitment in the Police.” Public Administration 89 (2): 557–576.

- Diefenbach, T., and J. A. A. Sillince. 2011. “Formal and Informal Hierarchy in Different Types of Organization.” Organization Studies 32 (11): 1515–1537.

- Egeberg, M. 1999. “The Impact of Bureaucratic Structure on Policy Making.” Public Administration 77 (1): 155–170.

- Eglene, O., and S. S. Dawes. 2006. “Challenges and Strategies for Conducting International Public Management Research.” Administration & Society 38 (5): 596–622.

- Eisenberger, R., P. Fasolo, and D.-L. Valerie. 1990. “Perceived Organizational Support and Employee Diligence, Commitment, and Innovation.” Journal of Applied Psychology 75 (1): 51–59.

- Eisenberger, R., R. Huntington, S. Hutchison, and D. Sowa. 1986. “Perceived Organizational Support.” Journal of Applied Psychology 71 (3): 500.

- Erben, G. S., and A. B. Güneşer. 2008. “The Relationship between Paternalistic Leadership and Organizational Commitment: Investigating the Role of Climate regarding Ethics.” Journal of Business Ethics 82 (4): 955–968.

- Esteve, M., C. Schuster, A. Albareda, and C. Losada. 2017. “The Effects of Doing More with Less in the Public Sector: Evidence from a Large-Scale Survey.” Public Administration Review 77 (4): 544–553. doi:10.1111/puar.12766.

- Evans, P., and J. E. Rauch. 1999. “Bureaucracy and Growth: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects Of” Weberian” State Structures on Economic Growth.” American Sociological Review 64 (5): 748–765.

- Fernández-Carro, R., and V. Lapuente-Giné. 2016. “The Emperor’s Clothes and the Pied Piper: Bureaucracy and Scientific Productivity.” Science and Public Policy 43 (4): 546–561.

- Fernández-Gutiérrez, M., and S. Van de Walle. 2019. “Equity or Efficiency? Explaining Public Officials’ Values.” Public Administration Review 79 (1): 25–34.

- Fischer, R., and A. Mansell. 2009. “Commitment across Cultures: A Meta-Analytical Approach.” Journal of International Business Studies 40 (8): 1339–1358.

- Fitzpatrick, J., M. Goggin, T. Heikkila, D. Klingner, J. Machado, and C. Martell. 2011. “A New Look at Comparative Public Administration: Trends in Research and an Agenda for the Future.” Public Administration Review 71 (6): 821–830.

- Fletcher, C., and R. Williams. 1996. “Performance Management, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment1.” British Journal of Management 7 (2): 169–179.

- Fukuyama, F. 2013. “What Is Governance?” Governance 26 (3): 347–368.

- George, B., and S. K. Pandey. 2017. “We Know the Yin—But Where Is the Yang? toward a Balanced Approach on Common Source Bias in Public Administration Scholarship.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 37 (2): 245–270.

- Gould-Williams, J. 2007. “HR Practices, Organizational Climate and Employee Outcomes: Evaluating Social Exchange Relationships in Local Government.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 18 (9): 1627–1647.

- Gould-Williams, J., and F. Davies. 2005. “Using Social Exchange Theory to Predict the Effects of HRM Practice on Employee Outcomes: An Analysis of Public Sector Workers.” Public Management Review 7 (1): 1–24.

- Gualmini, E. 2008. “Restructuring Weberian Bureaucracy: Comparing Managerial Reforms in Europe and the United States.” Public Administration 86 (1): 75–94.

- Gustavson, M., and S. Aksel. 2016. “Organizing the Audit Society Does Good Auditing Generate Less Public Sector Corruption?” Administration & Society 50 (10): 1508–1532.

- Haas, D. F., and F. A. Deseran. 1981. “Trust and Symbolic Exchange.” Social Psychology Quarterly 44 (1): 3–13.

- Hammerschmid, G. 2015. “COCOPS Executive Survey on Public Sector Reform in Europe - Views and Experiences from Senior Executives - Full Version. [ZA6598 Data file Version 1.0.4]. Cologne: GESIS Data Archive. doi:10.4232/1.12474

- Hammerschmid, G., A. Oprisor, and V. Štimac. 2013. COCOPS Executive Survey on Public Sector Reform in Europe: Research Report. http://www.cocops.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/COCOPS-WP3-Research-Report.pdf

- Hammerschmid, G., S. Van de Walle, R. Andrews, and P. Bezes. 2016. Public Administration Reforms in Europe: The View from the Top. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hammerschmid, G., S. Van de Walle, and V. Stimac. 2013. “Internal and External Use of Performance Information in Public Organizations: Results from an International Survey.” Public Money & Management 33 (4): 261–268.

- Haueter, J. A., T. H. Macan, and J. Winter. 2003. “Measurement of Newcomer Socialization: Construct Validation of a Multidimensional Scale.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 63 (1): 20–39.

- Hofstede, G., G. J. Hofstede, and M. Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival. 3rd ed. New York; London: McGraw-Hill.

- Jafri, M. H. 2010. “Organizational Commitment and Employee’s Innovative Behavior: A Study in Retail Sector.” Journal of Management Research 10 (1): 62–68.

- Jakobsen, M., and R. Jensen. 2015. “Common Method Bias in Public Management Studies.” International Public Management Journal 18 (1): 3–30.

- Jeannot, G., S. Van de Walle, and G. Hammerschmid. 2018. “Homogeneous National Management Policies or Autonomous Choices by Administrative Units? Inter-And Intra-Country Management Tools Use Variations in European Central Government Administrations.” Public Performance & Management Review 41 (3): 497–518.

- Jones, B. S. 2008. “Multilevel Models.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by J. M. Box-Steffensmeier, H. E. Brady, and D. Collier. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Kopecký, P., J.-H. N. Sahling, F. Panizza, G. Scherlis, C. Schuster, and M. Spirova. 2016. “Party Patronage in Contemporary Democracies: Results from an Expert Survey in 22 Countries from Five Regions.” European Journal of Political Research 55 (2): 416–431.

- Lægreid, P., and L. R. Wise. 2015. “Transitions in Civil Service Systems: Robustness and Flexibility in Human Resource Management.” In Comparative Civil Service Systems in the 21st Century, edited by T. Toonen, F. van der Meer, and J. Raadschelders, 203–222. New York, NY: Palgrave.

- Lapuente, V. G., and K. Suzuki. 2017. The Prudent Entrepreneurs: Women and Public Sector Innovation. QoG Working Paper Series 2017:11. Gothenburg, Sweden: Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg.

- Locke, E. A. 1997. “The Motivation to Work: What We Know.” Advances in Motivation and Achievement 10: 375–412.

- Lœgreid, P., and L. R. Wise. 2007. “Reforming Human Resource Management in Civil Service Systems: Recruitment, Mobility, and Representativeness.” In The Civil Service in the 21st Century, edited by Jos C. N. Raadschelders, Theo A. J. Toonen and Frits M. Van der Meer, 169–182. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Markovits, Y., A. J. Davis, D. Fay, and V. D. Rolf. 2010. “The Link between Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: Differences between Public and Private Sector Employees.” International Public Management Journal 13 (2): 177–196.

- Mathieu, J. E., and D. M. Zajac. 1990. “A Review and Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences of Organizational Commitment.” Psychological Bulletin 108 (2): 171–194.

- McClean, E., and C. J. Collins. 2011. “High-Commitment HR Practices, Employee Effort, and Firm Performance: Investigating the Effects of HR Practices across Employee Groups within Professional Services Firms.” Human Resource Management 50 (3): 341–363.

- Meier, K. J., A. Rutherford, and C. N. Avellaneda, eds. 2017. Comparative Public Management: Why National, Environmental, and Organizational Context Matters. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Meyer, J. P., D. J. Stanley, L. Herscovitch, and L. Topolnytsky. 2002. “Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 61 (1): 20–52.

- Meyer, J. P., D. J. Stanley, T. A. Jackson, K. J. McInnis, E. R. Maltin, and L. Sheppard. 2012. “Affective, Normative, and Continuance Commitment Levels across Cultures: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 80 (2): 225–245.

- Meyer, J. P., and N. J Allen. 1987. “A Longitudinal Analysis of the Early Development and Consequences of Organizational Commitment.” Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement 19 (2): 199–215. doi:10.1037/h0080013"10.1037/h0080013.

- Meyer, J. P., and N. J. Allen. 1991. “A Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational Commitment.” Human Resource Management Review 1 (1): 61–89.

- Meyer, J. P., and N. M. Parfyonova. 2010. “Normative Commitment in the Workplace: A Theoretical Analysis and Re-Conceptualization.” Human Resource Management Review 20 (4): 283–294.

- Miller, G. 2000. “Above Politics: Credible Commitment and Efficiency in the Design of Public Agencies.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10 (2): 289–328. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024271.

- Miller, G. J., and A. B. Whitford. 2016. Above Politics: Bureaucratic Discretion and Credible Commitment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Milward, B., L. Jensen, A. Roberts, M. I. Dussauge-Laguna, V. Junjan, R. Torenvlied, A. Boin, H. K. Colebatch, D. Kettl, and R. Durant. 2016. “Is Public Management Neglecting the State?” Governance 29 (3): 311–334.

- Moldogaziev, T. T., and C. Silvia. 2015. “Fostering Affective Organizational Commitment in Public Sector Agencies: The Significance of Multifaceted Leadership Roles.” Public Administration 93 (3): 557–575.

- Moon, M. J. 2000. “Organizational Commitment Revisited in New Public Management: Motivation, Organizational Culture, Sector, and Managerial Level.” Public Performance & Management Review 24 (2): 177–194.

- Mowday, R. T., L. W. Porter, and R. M. Steers. 1982. Employee-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover. New York: Academic press.

- Moynihan, D. P., and S. K. Pandey. 2007. “Finding Workable Levers over Work Motivation: Comparing Job Satisfaction, Job Involvement, and Organizational Commitment.” Administration & Society 39 (7): 803–832.

- Nishii, L. H., and D. M. Mayer. 2009. “Do Inclusive Leaders Help to Reduce Turnover in Diverse Groups? the Moderating Role of Leader–Member Exchange in the Diversity to Turnover Relationship.” Journal of Applied Psychology 94 (6): 1412–1426.

- Nistotskaya, M., and L. Cingolani. 2016. “Bureaucratic Structure, Regulatory Quality, and Entrepreneurship in a Comparative Perspective: Cross-Sectional and Panel Data Evidence.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26 (3): 519–534.

- Nistotskaya, M., N. Charron, and V. Lapuente. 2015. “The Wealth of Regions: Quality of Government and SMEs in 172 European Regions.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 33 (5): 1125–1155.

- O’Toole, L. J., and K. J. Meier. 2015. “Public Management, Context, and Performance: In Quest of a More General Theory.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 25 (1): 237–256. doi:10.1093/jopart/muu011.

- Odom, R. Y., W. Randy Boxx, and M. G. Dunn. 1990. “Organizational Cultures, Commitment, Satisfaction, and Cohesion.” Public Productivity & Management Review 14: 157–169. doi:10.2307/3380963.

- Oliveros, V., and C. Schuster. 2018. “Merit, Tenure, and Bureaucratic Behavior: Evidence from a Conjoint Experiment in the Dominican Republic.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (6): 759–792. doi:10.1177/0010414017710268.