ABSTRACT

Auditing is a key tool for governing performance. Informed by the ‘audit trail logic’ this article takes a micro-perspective on auditing in which the auditees play an active role. Using the case of eldercare, it explores what actors do as they take part in audits and how they make sense of the underlying logic. Findings reveal that the roles of auditor and auditee may not only shift between audits, but also blur during audit activities. Therefore, this article contributes to public performance literature and practice by empirically showing how actors involved in an audit negotiate a shared understanding of performance.

Introduction

The role of auditing in the governance of public sector performance has been the subject of extensive research and discussion over the last decades. By their claim to promote ‘good governance’ – values such as transparency and accountability (Shore and Wright Citation2015; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017) – auditing systems have become a key tool by which performance in public services is made governable. This development has had far-reaching consequences not only for public agencies being subjected to intensified auditing, but also for the very meaning of ‘performance’. Rather than being a neutral technique of monitoring and assessment, auditing has been described as shaping the environment in which it operates and forcing actors to adopt a ‘logic of auditability’ (Power Citation1996). Public organizations are increasingly established as auditable entities (Power Citation1997; Bromley and Powell Citation2012), where the act of auditing shapes not only the descriptions and evaluations of these organizations’ performance, but also their internal processes and how their employees think about their professional roles (Shore and Wright Citation2015).

While traditional auditing literature has tended to portray auditing as a static relationship wherein a specified auditor audits an assigned auditee, the performance management reforms during the last few decades have often implied mixed modes of governance and various forms of hybrid arrangements and public service delivery (e.g. Skelcher and Smith Citation2015). These developments have sparked a recent interest in hybrid accountabilities in public management (e.g. Blomqvist and Winbladh Citation2020; Overman Citation2020; Benish and Mattei Citation2020), acknowledging that not only have public organizations’ accountability commitments multiplied in recent years, but have also become increasingly entangled (Hagbjer Citation2014). While it has been argued that the effect of multiple accountabilities on the organizations audited or evaluated can be liberating as well as constraining (e.g. Pollock et al. Citation2018), scholars are now paying increased attention to how practices of rendering accounts and posing accountability obligations are shifting, situational, and largely intertwined with local considerations and justifications (Gassner, Gofen, and Raaphorst Citation2020; Ewert Citation2020; Overman Citation2020). This increased complexity has generated calls for studies that further explore the micro-foundations of performance management and audits (Power Citation2019), that focus on how processes of hybridization play out in practice (Benish and Mattei Citation2020), and that analyse how the multiplicity of roles and uses of accounting and performance management systems creates conflicts as well as opportunities in public administration (Steccolini Citation2019).

In light of this discussion, this paper sets out to analyse the practices by which performance is made auditable at an organizational level. To situate the study theoretically, we draw on a framework recently suggested by Power (Citation2019), focusing what he terms ‘the audit trail logic’. The audit trail logic is, simply put, a logic of auditing and auditability which is performative of the reality in which it operates and which ‘operationalizes and realizes different performance values’ (Power Citation2019, 4). The benefit of the framework is that it captures the process by which performance accounts are turned into facts about performance and directs us to put individual actors – those actually engaged in enacting, reproducing, and making sense of the underlying logic of auditing – at the centre of the analysis.

Taking Power’s framework as a point of departure, we use the context of eldercare in Sweden to analyse how the audit trail logic unfolds at the micro-level and what organizational actors actually do to make an organization auditable. Eldercare is a particularly fruitful site for exploring how actors make sense of and enact the idea of auditing, for two main reasons. First, it is a difficult task for auditors to make social work such as eldercare auditable. Performance in eldercare is hard to define and measure, and the knowledge base for what constitutes ‘good performance’ is contested (Munro Citation2004; Blomqvist and Winbladh Citation2020). Furthermore, eldercare is an operation that, to a large extent, takes place in the very private sphere of people’s homes, which makes performance monitoring even more challenging. Second, there is a multiplicity of actors auditing performance and quality in eldercare, each of whom has specific standards and measurements. Hence, organizational actors navigate in a highly complex field of accountabilities, where roles are all but static and conflicting demands are ever-present (Brandtner Citation2017; Hagbjer Citation2014).

Building on rich empirical data from Swedish public eldercare organizations, we describe how eldercare performance is made auditable through enacting the audit trail logic by producing accounts of performance in audits and identifying indicators by linking criteria to particular events, processes, or accounts, as well as through facilitating local usefulness by actively adopting an approach where audit is made comprehensible and meaningful. These activities illustrate the ways by which those assigned the task of auditing eldercare – the auditors – as well as those being audited – the auditees – interact to make sense of the audit process, as well as how these roles can shift and blur over time and depending on the particular audit. Specifically, the analysis reveals how formal auditees can be drawn into the conduct of auditing to the point where the very division of the roles ‘auditor’ and ‘auditee’ as a self-evident point of departure for studies of auditing can be called into question. This leads us to argue that a research approach that focuses on how the audited object is jointly created, rather than how specific actors fulfil a pre-defined role in a web of relationships, might be a key to further theoretical development of how performance in the public sector is visualized and made governable.

Making performance auditable: a micro-level approach

This paper assumes a broad definition of ‘audit’ as a systematic and independent examination of an object which leads to an assessment of whether the object meets some kind of standard, expressed in rules, codified norms, political goals, or the like, aiming to enable accountability and/or support improvement. This definition covers a wide range of monitoring practices used for accountability purposes and to support performance improvement (Dahler-Larsen Citation2019; Shore and Wright Citation2015; Power Citation1997). Common to these practices is that they are all based on an accountability relationship – be it public, professional, or market-based (Bovens Citation2007) – and have assessments as their end product. While such a broad definition might be criticized for being too imprecise (see Maltby Citation2008; Humphrey and Owen Citation2000), it serves as a fruitful point of departure for this study in which ‘audit’ is understood as a normative and performative idea as much as an operational practice (Power Citation1997).

The spread of this idea of auditing over the past few decades, and the consequences for public administration, is well-documented in research. Strathern (Citation2000) described from an anthropological perspective how ‘audit cultures’ pervade public and private sector institutions, and Power (Citation1997) suggested that we live in an ‘audit society’ in which basically everything in organizational life is made receptive to the same foundational principle of auditing, and organized so as to be auditable. The widespread adoption of performance measurement systems is described as a key component in this development (Steccolini Citation2019; Bowerman, Raby, and Humphrey Citation2000). While these systems aim to support the managing and improvement of performance, they also constitute important input in audit processes. As such, performance measurement systems and audits are largely intertwined: institutionally, as these phenomena have expanded side by side in public administration, and practically, as processes of measuring performance are entangled in performance auditing and vice versa (Gendron, Cooper, and Townley Citation2007; Funck Citation2015).

However, making performance auditable has proven to be a much more multifaceted practice than merely installing systems for performance measurements and providing auditors with the output of these systems. First, other forms of performance accounts such as oral or written narratives are often used to complement the picture of the audited operations. Research has shown that such a diversity of accounts is particularly important in situations where metrics are contested, such as in social services (Munro Citation2004; Kastberg and Ek Österberg Citation2017), and where accountability arrangements are multiplying and various perspectives of performance co-exist (Overman Citation2020; Schwabenland and Hirst Citation2020; Dahler-Larsen Citation2019; Bromley and Powell Citation2012). Second, the ways in which accounts of performance are produced and used in particular audits are dependent on the local context in which they are embedded. Auditability is thus to a large extent a socially situated and localized achievement (Radcliffe Citation1999; Power Citation2019). Although the idea of audit presupposes that actual performance by nature is comparable to standards of (good) performance, auditing performance is very much about defining, at a highly practical level, the meaning of performance.

The audit trail logic

Acknowledging the contextual nature of audit and auditability and advancing the importance of micro-level analyses of how the idea of auditing affects and reproduces itself in actual audit operations, Power (Citation2019) suggested the notion of the audit trail: a performative meta-logic which operationalizes and realizes the presumed values of auditing. According to Power’s framework, it is the repeated enactment and reproduction of this logic that constitute the micro-foundations of the audit society and which could (and should) be at the centre of future empirical studies. Simply stated, the audit trail shows how things are made auditable through a stepwise production of organizational performance accounts. The logic, as described, is inevitably linked to claims for facticity, which means that information ‘come to be seen, and made sense of, by actors as referring to an organizational reality of performance’ (Power Citation2019, 20). Thus, it is an ‘acquired taken-for-grantedness’, conditioned by the well-established procedures of measurement and documentation reported in previous studies on auditability. The fact that auditing is often defended on the grounds of transparency (Christensen and Cornelissen Citation2015; de Fine Licht Citation2019) signals the confidence placed on the ability of audit processes to generate true reflections or facts about organizational operations.

According to the audit trail logic, auditing consists of two sub-processes: 1) the production of primary traces, and 2) the production of organizational performance accounts. In the first phase, organizational actors use a variety of methods and artefacts to create performance facts, that constitute and define the auditability of performance (Power Citation2019, s. 16). In the second phase, these facts are systematically aggregated into systematic descriptions and valuations of organizational performance. Through these sub-processes, the audit trail underlines the logic and practices by which representations of various kinds become ‘facts’ of performance and how organizational actors are entangled in their reproduction. The framework thereby supports an analysis on how operations are made auditable on an organizational rather than institutional level (cf. Power Citation1996).

Furthermore, the audit trail framework draws attention to the actors in the process. The notion of facticity, as compared to objectivity and transparency, emphasizes that whether representations are in themselves accurate or true is subordinate to how they become accepted and normalized as facts among the actors involved. This is not to say that actors relate un-reflected to them. Rather, several studies have shown that actors may embrace the logic and be attracted to its outcomes, and at the same time be critical of the reductive and partial nature of it, in a highly dynamic and reflexive way (Pollock et al. Citation2018; Gassner, Gofen, and Raaphorst Citation2020; Sauder and Espeland Citation2009). However, through repeated enactment of the logic, actors will, according to the model, form dispositions to act ‘as if’ accounts produced are truths about reality, which allows the logic to be reproduced. Power (Citation2019) suggested that such disposition formation takes place through an ongoing sense-making process, which explains how institutionalization evolves from weak through medium to strong.

Actors in this case are simply the individuals involved in auditing. Traditionally, these are presented as assuming two roles: the auditor and the auditee. Within the auditing literature, the role of auditor is explored through empirical studies on their knowledge, approach, methods, and practices by which they strive to make an impact on audited organizations and be both effective and legitimate (Pentland Citation1993; Radcliffe Citation1999; Gendron, Cooper, and Townley Citation2007). In contrast, auditees have primarily been analysed as receivers of audit who, in various ways, react and conform towards the instruments and judgements they are subjected to, and not as actors partaking in the audit activities (Espeland and Sauder Citation2007; Shore and Wright Citation2015; Bromley and Powell Citation2012). The shifting of work practices, changes in resource allocation, and proliferation of gaming strategies are aspects of such reactivity identified in previous studies (Taylor Citation2020; Bevan and Hood Citation2006).

Recent studies, however, suggest a more salient and active position for auditees in the audit process. First, research shows that auditees not only respond to and game audits, but are sometimes highly involved in them. They are active players who largely interact with the auditors during the process of making their operations auditable, particularly in settings where quantitative accounts of performance are contested, such as in social services (Munro Citation2004). Second, Pollock et al. (Citation2018) argued, building on a multi-sited study of rankings in the IT sector, that a strict focus on conformance fails to fully explain how organizations, whether private or public, respond when audits are multiplying, i.e. when there are many different standards from which performance is evaluated. This reasoning speaks to the evolving literature on hybrid accountability, which explores how actors navigate in the web of multiple, often competing, demands and obligations of contemporary governance systems (e.g. Benish and Mattei Citation2020). In the context of auditing, this multiplicity can take the form of several auditors auditing various aspects of performance, sometimes even simultaneously. In the context of public service delivery, it can also involve hierarchies of auditing wherein an auditor at one level finds herself in the role of the auditee in another, such as when external auditors audit the performance of internal auditors, as shown by Liston‐Heyes and Juillet (Citation2020) analysis of public sector auditing in Canada; when local level auditing is audited by central level actors, as shown by Lindgren, Hanberger, and Lundström (Citation2016) study of school governance in Sweden; or when global orders structure multiple layers of certification and accreditation, as described by Gustafsson (Citation2020). Taken together, while the roles of auditor and auditee are formally given in particular audit processes, these are played out in complex and dynamic audit arrangements where we can expect a variety of audit trails to co-exist, being manifestations of the same meta logic. This complexity calls for more nuanced empirical examinations of how auditing is actually realized at the level of practice and what it means in terms of institutionalization.

Implications of theoretical framework

This paper uses Power’s (Citation2019) framework of the audit trail logic as a guide for analysis of how eldercare performance is made auditable at the micro-level. Central to the framework is the idea of performativity which suggests that the logic reproduces itself in processes of producing auditable accounts of performance, and forming the disposition of actors to act ‘as if’ these accounts represent reality. While the framework conceptualizes how such dispositions develop (are strengthened) over time, thereby forming the basis for transitions between stages of institutionalization, our focus is on the local dynamics at a specific time. This means that, rather than following a whole process of institutionalization, we draw attention to and approach auditability as an achievement in each audit, focusing on a) what actors do to produce auditable organizational accounts of performance (i.e. which primary traces are produced or brought to use; how these are aggregated and linked to standards of performance), and b) how actors make sense of these activities and internalize (or not) the logic (i.e. how dispositions are formed).

We refer to actors as the individuals taking part in audit work (whether as formal auditor or as formal auditee), while the audit object is constructed as the ‘thing’ being audited. The activities of both auditors and auditees are acknowledged as being part of audit work, and both groups are acknowledged, analytically, as performers of audit. Moreover, we do not focus on specific audit processes but take into account that actors experience and take part in a multiplicity of auditing activities. Hence, roles are dependent on what attention is directed towards at what particular point in time – a point of departure which is reflected in the study´s research design and methods.

Research design and the case of auditing in eldercare

Determining the boundaries of an audit, when the process starts, ends and which actors and actions are included, is not as simple as it might seem. Also, various audit processes are linked to or build on each other. We believe that in order to understand how organizational actors enact and make sense of the audit trail logic, this complexity needs to be taken into account.

The research strategy is inspired by what Marcus (Citation1995) terms ‘multi-sited ethnography’. This entails a traditional ethnographic ideal of long-lasting observation and participation (Bate Citation1997), though instead of a single-site location, the object of study is multi-sited and defined by logical connections created as the researcher moves across settings. In our case, fieldwork was conducted through a series of research activities, including interviews and observations, as well as analysing documents, newspaper articles, and websites, which in different ways relate to auditing of performance in eldercare. The main advantage of such a research strategy is that it avoids getting stuck in conventional points of departure and categories, which fits well the theoretical framing of the study.

Albeit multi-sited, the starting point for fieldwork was the auditing of performance in Swedish eldercare services, consisting of homebased services and special housing. While national regulations (the Social Security Act and the Healthcare Act) frame the conditions and specify basic requirements, local authorities have the primary responsibility for the delivery of services. From an international perspective, the Swedish municipalities (there are 290) are unusually independent (Sellers, Lidström, and Bae Citation2020). This means that they not only keep major responsibility for designing and implementing welfare services, but they also have the ability to set their own tax rates and are thereby responsible for the funding of eldercare.

Moreover, while Sweden has a history of universalistic ambitions to provide tax-funded eldercare services of high quality (Meagher and Szebehely Citation2013), reforms associated with the New Public Management agenda, and not least the focus on performance management and marketization, found fairly fertile ground in Sweden (e.g. Hall Citation2013; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017), and there is widespread experience of performance measurement and auditing in the eldercare sector. Today, auditing of performance in Swedish eldercare is a well-established practice wherein audit processes, rather than being contested, are the target of ongoing finetuning.

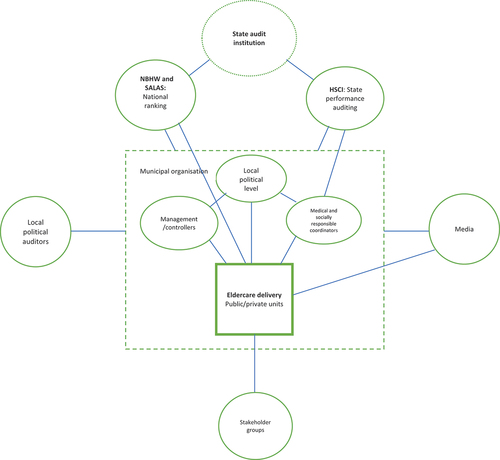

The local authorities have an obligation by law to monitor eldercare performance: by auditing activities initiated from the central level as well as through institutionalized systems of reporting user complaints and care deviations. At the same time the authorities themselves are audited by several external actors as ultimately responsible for eldercare services. The Health and Social Care Inspectorate (HSCI) has a key role through its mission to audit compliance with core national regulations. Also, another state agency, the National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW), stands with the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) behind the national quality ranking system ‘Open Comparisons’, which build on information reported by each municipality and which is highly influential. shows the complexity of audit relations (bold lines) in the eldercare landscape; where national as well as local actors are engaged in securing eldercare performance, and where actors in the formal role as auditor at one level can turn into a formal auditee at another level.

All these types of auditing deal in different ways with performance and, thus, gradually came to be included in the empirical study. Eldercare has a strong tradition of individual and intuitive work in which both quality standards and the objects being audited are highly elusive. Despite growing commitment to evidence-based practice, eldercare is ‘close to an auditor’s worst nightmare’ (Munro Citation2004). To achieve legitimate assessments of performance, a broad range of traces is required. In situations like these, we can expect auditees to have a crucial role during audits, which makes eldercare a particularly fruitful case in relation to the aim of this study.

The analysis in this paper builds on data that stretch over about a decade. As in all ethnographic studies, time is crucial as it enables deep engagement in the object of study and multi-faceted field material to evolve gradually. There is, however, no longitudinal ambition: development and change are not dealt with analytically. Rather, we explore the micro-level of auditing – actions, sensemaking and contextual dynamics – and thereby bring nuance to the enactment of the audit trail logic which, by extension, could be used in the debate on broader organizational and societal issues, as suggested by Power (Citation2019).

Data and analysis

We rely on 28 semi-structured interviews with 35 professionals at different levels in Swedish eldercare, representing five different municipalities and state agencies (see appendix 1). The interviewees are state auditors (6), politicians and managers at municipal level (9), administrative coordinators (7), medically responsible nurses and socially responsible coordinators (8), and elder care professionals (4). In addition, one interview (1) was conducted with a representative of the SALAR who was not himself active in auditing but worked to support quality development in eldercare. All of them work with eldercare issues and are involved in different ways in auditing of performance. The interviews have been conducted within two different research projects focusing on auditing activities in eldercare, in 2008–2011, and in 2016–2018. Within both projects, the aim was to explore audit at the level of practice, including activities of both auditors and auditees.

The interviews covered broad themes such as common and recurring audit activities, specific audit experiences, audit visits, documentation, indicators and data-obtaining, and audit reports. Depending on the interviewee’s position, the focus of the interviews varied. While some spoke primarily about following up in contractual relations, some underlined the reporting of deviations from care users and professionals, and others mainly discussed the state level auditing. Most of them switched quite easily between different forms of auditing in their descriptions in a way that made clear the interrelatedness between different audit forms and activities. The interviews lasted between fifty minutes and two and a half hours. 20 were recorded and transcribed verbatim. In those 8 not recorded (either due to technical problems or because the interviewees did not want to), notes were taken that were carefully summarized in direct connection with the interviews.

The study was conducted in line with laws and ethical guidelines for research involving personal data in Sweden, and followed all regular processes for ethical and quality assurance at the University of Gothenburg. All interviews were conducted with informed consent, and no information on personal names or specific contextual markers that could identify any actors was reported at any stage of the study. Moreover, the empirical data and tentative analysis was presented to practitioners on several occasions throughout the phase of data collection, thereby informing and confirming the final analysis.

In addition to the interviews, a broad range of written material has been analysed. This material can be sorted in two broad categories: texts produced within auditing processes, such as audit reports and correspondence, and texts about auditing, such as policy documents and news media articles. While texts in the second category were used for developing a deep understanding of the study object and thereby define its boundaries in line with the multi-sited ethnographic approach (Marcus Citation1995), the texts in the first category were used more explicitly in the analysis. The empirical material as a whole (interviews and written material) has been used to support our understanding of actors’ doings and sensemaking.

When analysing the interview data, we used an open approach wherein we moved back and forth between theory and the actual narratives as told by the interviewees. This means that we processed the data in several steps. First, we coded the interview transcripts manually and summarized them in keywords, tables, and narratives. Thereafter, we structured the data using broad empirical categories which were then revisited and revised continuously in relation to our analytical questions, focusing on what actors do and how they make sense of what they do when making eldercare auditable.

By focusing on what actors did to create new primary traces, as well as to use existing ones in order to link to particular assessment structures, our attention was drawn to the work of audit actors in identifying what traces could be seen as trustworthy representations of performance in particular audit trails and processes. Moreover, we found that activities were largely justified and made meaningful by the local usefulness actors jointly came to search for. The theoretical framework enabled us to conceptualize the reflexive approach of actors being the result of engaging in a variety of audit trail processes, united by the same meta-logic, while at the same time assuming different objects and different roles.

Enacting the audit trail logic in eldercare

In the following, we present our findings of how the audit trail logic is enacted – i.e. how eldercare performance is made auditable at the micro-level – in three themes: producing accounts and identifying indicators (which focus on the production and joint identification of auditable accounts of performance), and facilitating local usefulness (which focuses on how actors make sense of these activities and strive to make them meaningful and useful). Everyone working in eldercare, in the municipal organization or the care companies providing eldercare, gets involved in various ways in auditing of performance, and hence are in some sense actors in auditing. In Sweden, key actors in the auditing of performance in eldercare are: the external state performance auditors who temporarily intervene in local eldercare organizations; local politicians and managers, whose control ambitions are reflected in a range of monitoring activities and who also, as formally responsible for the operations and economy, have a key role in external accountability relations; coordinators at a central management level (quality controllers, contract managers, development strategists, etc.), who have a key role in the performance management system as well as organizing and bridging external audit initiatives locally; the socially responsible coordinator and the medically responsible nurse, which are key positions in the quality system and in local deviation reporting systems; and users and care professionals, being the actors participating in the actual execution of eldercare services, who contribute largely to the audit system via, e.g. complaints and deviation reporting.

All these groups of actors are involved in various forms of monitoring activities, quality assurance systems, and external audits, albeit in different roles. For instance, the coordinators at a central management level act as auditors in monitoring performance of the providing units and care companies, and as auditees in relation to state auditors. Further, for the socially responsible coordinator and the medically responsible nurse, auditing quality in care constitute the main task assignment. At the same time, their processes and judgements are central parts of what is being audited by state authorities. As we will show, actors involved in various and constantly ongoing audits – whether as auditors or auditees – partake in what resembles a joint project of establishing eldercare as an auditable object.

Producing accounts

Auditing eldercare performance involves collecting, producing, and using a broad range of data. Some of these data are produced through ongoing performance and quality reporting, available in digital systems, databases, and reports. While these reporting systems are extensive, seem to be steadily growing, and continuously produce a type of trace that is well-suited for verification and aggregation, the actors involved in auditing (both auditors and auditees) work actively to supplement them with (perceived) more valid traces of performance where the actual care relations are put at the centre to a greater extent.

An explanation for this multiplicity of accounts is the elusive character of performance in eldercare. Performance is largely understood in terms of quality, the meaning of which is constantly debated among the actors involved. There are stated goals of maintaining or increasing quality and of securing the development of good quality in future eldercare. However, what eldercare quality is remains a kind of mystery, which the actors involved in auditing were highly aware of.

The regulating state authority declares that quality means:

[…]that a business meets the requirements and objectives that apply in accordance with laws and other regulations for the business as well as decisions that have been announced with the support of such regulations. (SOSFS Citation2011, 9)

The law, which according to the quote should be met for a business to be regarded as high or sufficient quality, states in turn that the business ‘must be of good quality’ (SoL Citation2001, 453). Thus, ‘quality’ means achieving good quality, which does not provide much guidance.

In the absence of clear standards of performance, the rules and comprehensive guidance for how to measure and report performance (including quality) were given a particularly important role in the audit processes. For instance, each local authority, as formally responsible for eldercare services, has an obligation by law to conduct systematic quality work and to have a management system through which this work can be conducted. This includes processes and routines for risk analysis and self-control. Having a system for collecting and handling users’ complaints and comments is also mandatory. Further, there are specific laws for staffs’ obligation to report malpractice and medical injuries, which is reflected at the local level in extensive systems for documentation and investigation of deviations. Hence, while the systems were largely handled by the coordinators at a central management level, basically everyone – managers, care professionals, as well as users and their relatives – were involved through continuous reporting. The production of traces of performance involved all levels of the organizations and was constantly ongoing.

The outputs produced by these systems were determined by both internal control ambitions and external requirements such as the mandatory annual reporting of key figures to a national open database. However, regardless of the reasons behind what was registered and not, the outputs were highly essential as traces in the auditing of eldercare performance. The interviewees continuously referred to them – some with pride, such as one coordinator who described in detail improvements in the processes of handling the less serious deviations, while others were more sceptical. Most were pragmatic in their attitude and seemed to share the view that something is better than nothing.

Reflecting on the total amount of systems-produced accounts, a politician responsible for eldercare services (I21), stated that there is no lack of information. As he put it, ‘lots of materials’ are continuously produced and used ‘as a first layer’ in a broad range of audit settings. The question is rather what to do with all the information, and how to handle what others do with the information. This was the case not least with the media, whose reporting and judgements of the first layer material, from his point of view, were not always comprehensible and reasonable. However, the situation was quite the different for the auditees who were involved in the audit processes. They were very much aware of the structure and logic whereby each judgment was made possible, and actively partook in the work of identifying relevant indicators together with the auditors. This brings us to the next category.

Identifying indicators

Due to the elusive character of eldercare performance, the actors perceived the picture of the operations that the systems-produced outputs gave as severely limited in practice. A great deal of the auditing activities were thus about supplementing these data-driven traces with other types of performance information, such as narrative descriptions of the actual conduct. These descriptions could be written, as when managers were asked to describe some specific aspect of the operations in a report, but were often produced through interaction in more or less formalized forums for dialogue between auditors and auditees, which constituted an essential part of most audit processes. For instance, group interviews with care staff, unit managers, and central management were common events during audits, as were tours and on-site observations, which enabled conversations between auditors and auditees. Further, coordinators at the central management level who had key roles in organizing the auditing activities had continuous dialogue by email and telephone with different actors involved in the process.

The dialogues enabled complementary narrative accounts of performance in which the actual conduct of care was often in focus. Several interviewees emphasized that this was essential for auditors’ ability to really understand the operations audited, as well as for the auditees to find judgements reasonable and meaningful. Moreover, the dialogues permitted a negotiation and joint search for which traces that could be used as signs of performance. In audits, traces of performance become signs of something specific. For instance, in one audit, the percentage of care implementation plans having a user signature was used as a sign of users’ participation and influence. In another, a book club for the care staff was pointed out by a manager as an indicator of competence development. Likewise, an advisory group for meals at a special housing was interpreted as an indicator of ensuring the quality of meals in a dialogue between a unit manager and state auditors.

This joint search was essential since auditors did not know the operations enough to find out what could be important indicators from their perspective. The auditees, for their part, knew of the operations but not which out of all the mundane activities could be assigned importance in each specific situation. Thus, in the dialogues the actors jointly found out what was important and how in what particular context. Although ostensibly sticking to the formal roles as auditor and auditee, the construction of eldercare performance as an auditable object became something that the audit actors were in together.

Dialogues were also key to auditors’ anchoring and justification of particular audit trails, i.e. the assessment structure of traces and criteria and the overall goals and values these are linked to. The logic thus became comprehensible for the actors involved. One care professional described:

We didn´t really know how they would look, or what they would look at. But a lot of documentation, that much we knew … You could kind of understand that … They had done it elsewhere, if it was in X where they had clamped down on the documentation. (…) And we found out, when we looked at it … it is something that is very important! That you have binders and such things locked. Or if you have the doors locked in special housing for users with dementia, that there is a code visible. (Care professional, special housing, I4)

Several interviewees emphasized the advantage of dialogues as accounts-producing forums because they made it possible for the actors to include the user perspective more thoroughly, and thus avoid the audit’s focus straying too far from the individual care user. Questions like, ‘What do the ones we are here for think about the services they receive?’ were repeatedly asked as a reminder of the right perspective and approach. ‘Obviously, we are in a unit for eldercare and it is our users we are here for in the first place, after all’, as one socially responsible coordinator stated (I26), without concealing her criticism towards everything they are required to do that does not clearly benefit the elderly. Further, eldercare users often lack the ability and energy to express their point of view, which also explained why the actors – both auditors and auditees – found the role of channelling user voices, which the care staff often took on, as even more important.

Facilitating local usefulness

While the audit processes largely took shape in order to enable interaction and dialogue about indicators and criteria, they also manifested core values of auditor independence and objectivity. This was most clearly expressed in the various ways by which the audit object (the description of eldercare performance) was separated from the assessment of this particular object, rather than in a demarcation between auditor and auditees, as common understandings of auditing would suggest. The scientific terminology whereby auditing was communicated reflected the importance of such a separation. The separation was also reflected in the reluctance of the auditors to communicate valuing statements (too) early in the process, even in situations where the auditees explicitly requested it. Furthermore, the so-called ‘facts-checking procedure’ included in most audit processes was a crucial manifestation of the step-wise logic. The procedure meant that the auditees confirmed and approved the description of performance on which the assessment was made, before the assessment was communicated and published. This was done by the auditor sending a draft of the report without the final assessments included, which the auditees (most often a manager or coordinator) were to read through and, if necessary, correct. Though the procedure functioned more or less ceremonially and rarely affected the descriptions in a substantial way, it was an important event, as it acted as a bridge from ‘the making auditable process’ to the process of dealing with audit results.

Although the number of actors involved in the interaction with auditors during audit processes varied depending on each audit´s scope and character, the group was often limited. In most cases, one or a few of the civil servants at a central management level were involved, acting in the role of (internal) auditor or as a coordinator of external audit initiatives. The socially responsible coordinator and the medically responsible nurse had similar shifting roles, sometimes acting as auditors and sometimes as auditees. Together, these actors formed a local expert groups for auditing, and, as previously described, actively participated in the construction of the audit object. This included being responsible for mediating information about upcoming audits’ purpose and criteria, coordinating unit-level collection of performance accounts, and communicating audit results. Through this, these actors became important interpreters not only of performance as such, but of the specific ways in which performance was defined in specific situations. During audit processes they helped managers at special housings and units for home-based services to report the ‘right’ or ‘valuable’ things in their operations, at times beyond what was formally reported in the performance measurement systems. In doing so, they also facilitated ongoing, broad discussions on performance, which served as a means to make sense of the various measures, statements and processes.

However, when audit results were published, new actors were drawn into the process. Among the actors who had been involved in the process, audit results usually came as no surprise. ‘It was no surprise, it wasn’t, and that was a relief of course’, one manager said (I1). ‘The report didn’t contain any news’, a coordinator maintained (I3). While statements like these signalled that deficiencies were already known, it also signalled knowledge about what deficiencies that are common in that particular audit context. One unit manager described how she prepared herself for critique on care documentation: ‘We understood quite early that focus is on care documentation (…) They had done it elsewhere; I think it was in the municipality nearby. There, they were obsessed with the documentation’ (I4).

The local politicians, care professionals, and users and their relatives were often less prepared. Regarding the users and their relatives, a coordinator described the ‘mess’ audit reports could cause if vulnerable eldercare users suddenly got the feeling that they could not feel safe. This, she continued, was why there is always a need for additional information to users and relatives on what results of audits actually mean. Critique does not mean that care is bad. Similar reinterpretations and translations were also often made in relation to the local politicians who were formally responsible for the results, but largely outside the audit processes.

The ‘Open comparisons’ ranking system stood out in this regard. Although the ranking is the result of self-reported data, it is difficult to understand even for those reporting the data. The rankers clearly stated that results must be thoroughly analysed at the level of unit and municipality in order to enrich development work. Local actors were, however, highly sceptical of the value of the performance indicators; several interviewees maintained that everyone interprets and reports the indicators differently. The same indicators were aggregated differently in the ‘Open comparisons’ and the National user survey, leading to different statements on care quality. Those not familiar with the rankings, such as citizens and local politicians, could incorrectly believe that quality had dropped rapidly between the publications of two rankings, when in fact the situation was stable. This was, as one coordinator at central management level maintained, ‘a challenge when the results are published’ (I25).

Despite the anxiety and irritation that arose as a result of audit initiatives, the actors involved seemed to agree on what was the desirable, correct approach towards audits. Being audited should be seen as a learning opportunity, even in situations when the auditors underlined accountability purposes rather than improvement. The desirable approach also meant seeing audits as something normal; a standard procedure, nothing to be afraid of. One manager explained that it is important that the climate in the organization allows for being audited without feeling that they are looking for failures (I1). It should be positive to find out how far one has come in one’s work. This applies to all audits, internal and external, she argued. ‘They are not police officers, it is a learning opportunity, really, to talk with others about how they view what we do’, another manager pointed out (I16). Even in situations when there are clear weaknesses in the audit process and results, there are things to learn:

We thought it was a really bad audit report, we stand for that. But, it doesn´t mean it is worthless! I use to think that way about The Health and Care Inspectorate as well. Their audits are not ‘Oh, this was great’, but on the other hand you feel that all audits are good. It is the approach I have, that we can always learn something, we always get something highlighted. (Eldercare manager, I16)

In essence, this shows how actors in the audit process learn to decode and negotiate the process, thereby making it a meaningful activity.

Discussion and conclusions

This study draws attention to practices of auditing which, in recent decades, have become key to the governing of public performance and whose far-reaching effects on public administration and management are well-documented in research. In light of increasing hybridity in accountability arrangements in public administration (Benish and Mattei Citation2020; Pollock et al. Citation2018) and based on recent calls for micro-level studies of the role of auditing in organizations and society (e.g. Power Citation2019; Shore and Wright Citation2015), we set out to explore what actors actually do as they take part in audit processes and how they make sense of the logic that underlies them. With Swedish eldercare as an empirical case, our starting point was that auditees, like auditors, are performers of audits. By analytically focusing on the enactment of ‘the audit trail logic’ (Power Citation2019) our aim was to add nuance to contemporary understandings of how the practice of auditing affects public organizations and the governing and management of performance.

As the literature on auditability suggests, the standards against which operations are to be compared in audits shape what type of performance information that is produced and used. In our analysis at the micro-level, this was expressed in a search for not (only) ‘true’ but relevant information, in the sense of being adequate in relation to specific criteria. Moreover, the analysis revealed that the actors involved, whether as auditors or as auditees, developed a shared understanding of auditing as something they were in together: a joint project of establishing eldercare as an auditable object. This process was facilitated by actors shifting roles between different audits – sometimes taking on the formal role as auditor, sometimes as auditee, depending on the level of the audit – and by continuous dialogues on the meaning and function of audits. In these dialogues, actors in the formal role of auditee are by no means passive receivers. Rather, they actively enact the logic of auditing and strive to make it reasonable in their local settings. By linking mundane activities – such as ways of offering activities for the elderly, setting the table, or documenting medical deviations – to standards of performance and to overall goals and values for the audit, auditors as well as auditees participate in the construction of what performance actually is. The importance of audit dialogues as forums for making sense of local concerns as well as particular audit trails – what is considered valid as a sign of what in this specific situation – was emphasized by all the actors involved. Also, in cases of perceived shortcomings, they found ways to make them meaningful and useful. Thus, the actors partook in reproducing the logic, as suggested by Power (Citation2019), albeit without being completely controlled by it.

Theoretically, the main contribution of the study is that it challenges not only the traditional picture of auditees as passive receivers of audits, but also the analytical usefulness of the division in the two (often assumed static) roles of auditor and auditee. The analysis indicates that the main dividing line is not necessarily between auditor and auditees, but between those taking active part in the audit trail process, and those who are not. Actors in the first category are drawn into the conduct of audits as well as the logic that surrounds it. In our case, this role was typically held by the medically responsible nurse and the socially responsible coordinator, the civil servants at a central administrative level, and, to some extent, managers. Actors in the second category, such as local politicians responsible for the operations and assistant nurses who actually deliver care, had a peripheral role during the process and did not manage to make sense of the whole to the same extent. This is not to say that formal roles do not matter; after all, they tend to come with both status and power to sanction. It does, however, indicate that making eldercare performance auditable, and eventually transforming it into an object that has received the status of having been audited, is a project that extends beyond the formal roles as auditor and auditee, and that a strict focus on these roles, rather than on what actors do and what they construct, involves a risk of hiding important nuances from the analysis.

The study illustrates the usefulness of Power’s (Citation2019) framework of the ‘audit trail logic’ in analysing the construction of auditability at the level of practice. By linking the high ambitions of transparency and accountability to the everyday practices of measuring, narrating, and reporting through a performative logic maintained by actors in the process, the framework offers a guide for empirical data collection and enables analysis of the local without ignoring the institutional. One advantage, we argue, is that the framework analytically separates objects being audited from subjects being audited, a distinction that the notion of auditees tends to blur. The analytical focus on how, in our case, eldercare performance is made into an auditable object opens up for empirical investigation of the actors involved and their activities rather than on their formal roles. Expressed differently, by exploring rather than assuming the roles of auditing, micro-level studies can contribute with in-depth understanding of the local dynamics by which performance is made auditable. By focusing on the multiplicity of ways in which the audit trail logic manifests itself in eldercare, this study shows that the diversity of objects created (the result of each trail presupposing a unique combination of criteria, accounts, and traces) gives rise to a variety of co-existing roles and relations, which we believe is crucial in continued theorizing of how, when, and by whom the audit trail logic reproduces itself and the mechanisms behind the transitions between stages of performativity.

In particular, the analysis reveals that the multiplicity of trails was crucial to how actors made sense of what they were doing, and that the continuous shift between audit trails – and, for some actors, between roles – strengthened their reflexivity and ability to decode and adapt to various audit trails. Moreover, it helped actors adopt a healthy scepticism, since judgements of performance were seen as having as much to do with how specific audits were conducted as with the actual operations. In line with Pollock et al. (Citation2018), this indicates that organizational responses become more proactive and flexible with increased hybridity, and that situations of multiple accountability relations may not only constrain but also offer resources for agency (Schwabenland and Hirst Citation2020, 325). Thus, role-shifting is, we believe, a source of variation to further explore within the audit trail framework, as well as an observation that brings nuance to the process of how and why actors make sense of the audit trail processes and the meta-logic these embody.

In terms of implications for practice, previous research in social services shows that vague quality and performance standards affect audit practices in several ways (e.g. Munro Citation2004; Moberg, Blomqvist, and Winblad Citation2018; Blomqvist and Winbladh Citation2020). Our study supports such a conclusion and points to the crucial role of auditing as an interpreter of good performance, or at least as a tool for discussions on what this might mean. As such, auditing could – and in some sense did, in our case – contribute to improvement of performance in services (as the actors through discussions become increasingly aware of performance issues) as well as to anchor (vague) political goals and regulations by linking them to actual work practices through the procedures of audit.

In a broader sense, our description of the joint construction of an auditable object in dialogues between actors blurring their formal roles as auditors and auditees could be seen as conflicting with democratic ideals of transparency and objectivity. On the other hand, this informal side of auditing could generate stronger conditions for accountability in the form of supporting the creation of a virtuous organization, not only by supporting compliance and smooth processes, but also by reducing the risk of disconnection between, on the one hand, accounts, and on the other, stated goals. Moreover, the aspirations and attempts of auditees to achieve local value when the stated purpose of the audits was accountability is significant from a public management perspective, as it underlines the potential to take advantage of the values embedded in audit trails, and from a broader public administration or societal perspective, as it might add nuance to the discussion on value inverting audit society effects (Steccolini Citation2019; Power Citation2019).

This study has limitations that could be addressed by future research. The case of eldercare was chosen to represent a difficult case of auditing wherein both standards of what constitutes good performance and ways of measuring performance are contested. However, eldercare is only one of many sites in which micro-level studies of auditing are relevant. By exploring the local dynamics in different settings, future studies could further develop the understanding of the role of auditing in the governing of performance. These different setting could vary in terms of the involvement of those assigned the role of auditee in the production of primary traces, or in the composition of different complementary or competitive audit trail arrangements. Another potential limitation is the focus on Sweden. While we argue that Sweden represents a typical case of public administration that has been influenced by new public management ideals in terms of quantitative goals, Sweden also has a long history of universalistic welfare and participation. Therefore, studies taking a similar approach to the decoding of the audit process would be highly useful for exploring how different cultural and political settings shape conditions for how performance is constructed and made auditable.

Finally, the multi-sited research design comes with advantages as well as drawbacks. Although we have argued that it has the clear advantage of facilitating analysis of phenomena which extend over time and space, the analysis admittedly loses parts of the local context. Therefore, single-site longitudinal studies of ongoing processes of making performance auditable could bring valuable insights into how various audit arrangements become intertwined and how local understandings of the audit trail logic develop over time. This would be particularly important in order to understand how, when, and why transitions take place between the ‘stages of performativity’ (Power Citation2019), and what values are, or can be, embedded in, and thus strengthened through, these processes.

Acknowledgments

A previous version of this paper was presented at the New Public Sector seminar 2019 in Edinburgh where the authors received useful comments. The authors also wish to thank the research team at the Department for Management Accounting and Control, Helmut Schmidt University, as well as the three anonymous reviewers for insightful and valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emma Ek Österberg

Emma Ek Österberg is associate professor at the School of Public Administration at the University of Gothenburg. Her research focuses on various forms of governing public performance and quality, in particular public sector auditing.

Jenny de Fine Licht

Jenny de Fine Licht is associate professor at the School of Public Administration at the University of Gothenburg. Her main research interests are transparency, auditing, and public perceptions of legitimacy.

References

- Bate, S. P. 1997. “Whatever Happened to Organizational Anthropology? A Review of the Field of Organizational Ethnography and Anthropological Studies.” Human Relations 50 (9): 1147–1175. doi:10.1177/001872679705000905.

- Benish, Avishai, and Paola Mattei. 2020. “Accountability and Hybridity in Welfare Governance.” Public Administration 98 (2): 281–290. doi:10.1111/padm.12640.

- Bevan, Gwyn, and Christopher Hood. 2006. “What’s Measured Is What Matters: Targets and Gaming in the English Public Health Care System.” Public Administration 84 (3): 517–538. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00600.x.

- Blomqvist, Paula, and Ulrika Winbladh. 2020. “Contracting Out Welfare Services: How are Private Contractors Held Accountable?” Public Management Review. Published online 27 September 2020. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1817530.

- Bovens, Mark. 2007. “Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework.” European Law Journal 13 (4): 447–468. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x.

- Bowerman, Mary, Helen Raby, and Christopher Humphrey. 2000. “In Search of the Audit Society: Some Evidence from Health Care, Police and Schools.” International Journal of Auditing 4 (1): 71–100. doi:10.1111/1099-1123.00304.

- Brandtner, Christof. 2017. “Putting the World in Orders: Plurality in Organizational Evaluation.” Sociological Theory 35 (3): 200–227. doi:10.1177/0735275117726104.

- Bromley, Patricia, and Walter W. Powell. 2012. “From Smoke and Mirrors to Walking the Talk: Decoupling in the Contemporary World.” The Academy of Management Annals 6 (1): 483–530. doi:10.5465/19416520.2012.684462.

- Christensen, Lars T., and Joep Cornelissen. 2015. “Organizational Transparency as Myth and Metaphor.” European Journal of Social Theory 18 (2): 132–149. doi:10.1177/1368431014555256.

- Dahler-Larsen, Peter. 2019. Quality. From Plato to Performance. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- de Fine Licht, Jenny. 2019. “The Role of Transparency in Auditing.” Financial Accountability & Management 35 (3): 233–245. doi:10.1111/faam.12193.

- Espeland, Wendy N., and Michael Sauder. 2007. “Rankings and Reactivity: How Public Measures Recreate Social Worlds.” American Journal of Sociology 113 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1086/517897.

- Ewert, Benjamin. 2020. “Focusing on Quality Care Rather than ‘Checking Boxes’: How to Exit the Labyrinth of Multiple Accountabilities in Hybrid Healthcare Arrangements.” Public Administration 98 (2): 308–324. doi:10.1111/padm.12556.

- Funck, Elin K. 2015. “Audit as Leviathan: Constructing Quality Registers in Swedish Health Care.” Financial Accountability & Management 31 (4): 415–438. doi:10.1111/faam.12063.

- Gassner, Drorit, Anat Gofen, and Nadine Raaphorst. 2020. “Performance Management from the Bottom Up.” Public Management Review. Published online 22 juli. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1795232.

- Gendron, Yves, David J. Cooper, and Barbara Townley. 2007. “The Construction of Auditing Expertise in Measuring Government Performance.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (1–2): 101–129. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2006.03.005.

- Gustafsson, Ingrid. 2020. How Standards Rule the World. The Construction of a Global Control Regime. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hagbjer, Eva. 2014. Navigating a Network of Competing Demands: Accountability as Issue Formulation and Role Attribution across Organisational Boundaries. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Hall, P. 2013. “NPM in Sweden: The Risky Balance between Bureaucracy and Politics.” In Nordic Lights: Work, Management and Welfare in Scandinavia, edited by Å. Sandberg, 406–419. Stockholm: SNS förlag.

- Humphrey, Christopher, and David Owen. 2000. “Debating the ‘Power’ of Audit.” International Journal of Auditing 4 (1): 29–50. doi:10.1111/1099-1123.00302.

- Kastberg, Gustaf, and Emma Ek Österberg. 2017. “Transforming Social Sector Auditing. They Audited More but Scrutinized Less.” Financial Accountability and Management 33 (3): 284–298. doi:10.1111/faam.12122.

- Lindgren, Lena, Anders Hanberger, and Ulf Lundström. 2016. “Evaluation Systems in a Crowded Policy Space: Implications for Local School Governance.” Education Inquiry 7 (3): 237–258. doi:10.3402/edui.v7.30202.

- Liston‐Heyes, Catherine, and Luc Juillet. 2020. “Burdens of Transparency: An Analysis of Public Sector Internal Auditing.” Public Administration 98 (3): 659–674. doi:10.1111/padm.12654.

- Maltby, Josefine. 2008. “There Is No Such Thing as Audit Society: A Reading of Power, M. (1994a) ‘The Audit Society’.” Ephemera 8 (4): 388–398.

- Marcus, George E. 1995. “Ethnography In/of the World System. The Emergence of Multi-sited Ethnography.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 95–117. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523.

- Meagher, Gabrielle, and Marta Szebehely. 2013. Marketization in Nordic Eldercare: A Research Report on Legislation, Oversight, Extent and Consequences. Stockholm: Stockholm Studies in Social Work.

- Moberg, Linda, Paula Blomqvist, and Ulrika Winblad. 2018. “Professionalized through Audit?: Care Workers and the New Audit Regime in Sweden.” Social Policy and Administration 52 (3): 631–645. doi:10.1111/spol.12367.

- Munro, Eileen. 2004. “The Impact of Audit on Social Work Practice.” The British Journal of Social Work 34 (8): 1075–1095. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bch130.

- Overman, Sjors. 2020. “Aligning Accountability Arrangements for Ambiguous Goals: The Case of Museums.” Public Management Review 1–21. Published online 3 February 2020. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1722210.

- Pentland, Brian, T. 1993. “Getting Comfortable with the Numbers.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 18: 605–620. doi:10.1016/0361-3682(93)90045-8.

- Pollitt, Christopher, and Geert Bouckaert. 2017. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis - into the Age of Austerity. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Pollock, Neil, Luciana D’Adderio, Robin Williams, and Ludovic Leforestier. 2018. “Conforming or Transforming?: How Organizations Respond to Multiple Rankings.” Accounting, Organisations and Society 64: 55–68. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2017.11.003.

- Power, Michael. 1996. “Making Things Auditable.” Accounting, Organisations and Society 21: 289–315. doi:10.1016/0361-3682(95)00004-6.

- Power, Michael. 1997. The Audit Society. Rituals of Verification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Power, Michael. 2019. “Modelling the Microfoundations of the Audit Society: Organizations and the Logic of the Audit Trail.” Academy of Management Review. Published online March 7. doi:10.5465/amr.2017.0212.

- Radcliffe, Vaughan S. 1999. “Knowing Efficiency: The Enactment of Efficiency in Efficiency Audit.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 24 (4): 333–362. doi:10.1016/S0361-3682(98)00067-1.

- Sauder, Michael, and Wendy N. Espeland. 2009. “The Discipline of Rankings: Tight Coupling and Organizational Change.” American Sociological Review 74 (1): 63–82. doi:10.1177/000312240907400104.

- Schwabenland, Christina, and Alison Hirst. 2020. “Hybrid Accountabilities and Managerial Agency in the Third Sector.” Public Administration 98 (2): 325–339. doi:10.1111/padm.12568.

- Sellers, J. M., Anders Lidström, and Yooil Bae. 2020. Multilevel Democracy: How Local Institutions and Civil Society Shape the Modern State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shore, Cris, and Susan Wright. 2015. “Audit Culture Revisited: Rankings, Ratings, and the Reassembling of Society.” Current Anthropology 56 (3): 431–432. doi:10.1086/681534.

- Skelcher, Chris, and Steven R. Smith. 2015. “Theorizing Hybridity: Institutional Logics, Complex Organizations, and Actor Identities: The Case of Nonprofits.” Public Administration 93 (2): 433–448. doi:10.1111/padm.12105.

- SoL. 2001. “Socialtjänstlagen [Social Security Act].” 453.

- SOSFS. 2011. “Socialstyrelsens föreskrifter och allmänna råd om ledningssystem för systematiskt kvalitetsarbete [The National Board of Health and Welfare’s Regulations and General Advice on Management Systems for Systematic Quality Work].” 9.

- Steccolini, Ileana. 2019. “Accounting and the Post-new Public Management: Re-considering Publicness in Accounting Research.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 32 (1): 255–279. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-03-2018-3423.

- Strathern, Marilyn. 2000. Audit Cultures. Anthropological Studies in Accountability Ethics and the Academy. London: Routledge.

- Taylor, Jeannette. 2020. “Public Officials’ Gaming of Performance Measures and Targets: The Nexus between Motivation and Opportunity.” Public Performance & Management Review 44 (2): 272–293. doi:10.1080/15309576.2020.1744454.