ABSTRACT

The prospects and challenges of boundary-spanning public value co-creation are one of the quintessential features of public management in the current age of complexity. This paper argues that boundary-spanning takes on a heightened salience in multilevel jurisdictions where actors must not only navigate the horizontal contours of inter-organizational relations but also vertical tiers of jurisdiction in pursuit of joint action. Drawing insights from the multilevel governance literature, and using Canada's recent Innovation Superclusters Initiative as case study, the paper sheds some light on how public managers and policy entrepreneurs navigate strategically across boundaries in federal and other multitiered systems.

Introduction

The past two decades have witnessed a seismic transformation in public administration theory and practice related to the creation and delivery of public services. A central feature of this transformation is its emphasis on boundary-spanning inter-organizational mechanisms of value creation rather than on intra-organizational processes of public management. This shift does not discount the significance of internal intra-organizational processes. However, it places greater importance and urgency on positioning public managers to pursue boundary-spanning ventures among a constellation of actors through mechanisms premised on public value co-creation with, and for, citizens and society (Osborne Citation2018).

Recent studies in public management have looked at patterns of involvement in co-creation (Bentzen Citation2020), the key determinants of stakeholder salience (Best, Moffett, and McAdam Citation2019) and the implications of various mechanisms of value co-creation for public service users’ experiences (Farr Citation2016). One of the most systematic reviews of public value co-creation concludes that future studies could focus more on the outcomes of co-creation processes (Voorberg, Bekkers, and Tummers Citation2015). This paper builds on this body of works, but with the aim of understanding co-creation through the conceptual lens of boundary spanning. The analytical emphasis of boundary spanning as a conceptual framework in this paper is placed less on the particular configuration of network structures and more on the processes of network socialization that facilitate the integration of ideas and resources across organizations and jurisdictions (Brandsen, Steen, and Verschuere Citation2018; Bovaird et al. Citation2019; Tushman Citation1977).

Despite the prevalence of boundary-spanning in public administration practice over the past two decades, the concept itself has a long intellectual legacy in the field of organization theory dating back to the 1950s as scholars attempt to describe and analyse the mechanisms by which inter-organizational networks facilitate the flow of ideas and resources across a policy system (Tushman Citation1977; Thomson Citation1967; March and Simon Citation1958). Over this course of time, a rich body of literature across several research traditions has examined the character of the horizontal contours of boundary-spanning joint action in public administration and management (Bovaird et al. Citation2019; Matous and Wang Citation2019; Brandsen, Steen, and Verschuere Citation2018; Bergenholtz Citation2011; Tushman Citation1977; Allen and Cohen Citation1969; Thomson Citation1967; March and Simon Citation1958).

However, further elucidation of the concept is required to understand its implications for public management sector in the context of federal systems such as Canada, Australia and the United States, or for multitiered systems like the European Union. For instance, Meerkerk and Edelenbos’ (Citation2018) investigation of the facilitating conditions for boundary-spanning behaviour has proven rich and insightful, but it is focused on unitary institutional contexts. Guarneros-Meza and Martin (Citation2016) have explored the vertical dimensions of boundary spanning. However, their empirical focus on local public service partnerships in the UK leaves much room for elucidating vertical flows in multitiered systems. Federal systems, for instance, often consist of large geographies with profoundly fragmented layers and loci of policy subsystems (Bakvis, Brown, and Baier Citation2019; Fenna Citation2019; Brock Citation2018; Fabbrini Citation2017; Fossum Citation2017; Beland and Lecours Citation2016). The aim of this paper, therefore, is to shed light on boundary spanning processes in multitiered systems.

The empirical focus of the discussion is an examination of Canada’s recent Innovation Superclusters Initiative (ISI), a federal government initiative aimed at building a network of five regionally based national innovation systems (or clusters) across the country. These ‘Superclusters’ consist of a constellation of cities and regions stretching across provinces and bringing together public agencies, post-secondary institutions, research centres, businesses and a wide range of civic entrepreneurs (Government of Canada Citation2017a. Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) 2017). The ISI initiative in Canada thus provides a fitting case study to examine the boundary-spanning contours of public value co-creation in federal systems because it was conceived as a federal government programme whose implementation involves the cooperation of provincial governments in whose territorial jurisdictions the Superclusters are to be based. Moreover, the programme is conceived as a public-private venture involving third parties such as innovation system stakeholders drawn from the private sector, research centres and post-secondary institutions. These non-state actors are expected to play significant roles in the delivery of innovation policy as a joint venture in public value co-creation.

The main question to be addressed is as follows: What are the key features, strengths and constraints of Canada’s ISI initiative as a boundary-spanning venture of public value co-creation in a federal system? Addressing this question will shed light on how public officials and non-state actors navigate the complex labyrinth of multitiered jurisdictions while seeking, or responding to, joint initiatives in public value creation. The analysis will highlight some of the administrative triumphs and conundrums of value co-creation in Canada’s regionally fragmented and multi-layered federal system, with theoretical and practical implications for understanding similar processes in other multitiered systems.

The rest of the analysis is structured as follows. The next section provides a brief overview of key elements of the boundary-spanning literature in public administration before drawing insights from the multilevel governance (MLG) literature to advance our understanding of value co-creation in multitiered jurisdictions. In developing the framework, the discussion draws insights from several research traditions addressing distinct but overlapping concepts like boundary-spanning, multilevel governance, networks of policy entrepreneurs, co-creation, federalism and regionalism. The central thread that binds these concepts together is their shared focus on how actors navigate horizontal and vertical organizational boundaries in pursuit of joint action. The concept of regionalism in this framework centres the analysis on how such interorganizational joint actions in the context of federal systems with vast geographies are largely embedded in local regions. The third section provides an overview of the methodology that informed the study’s design, data collection and analysis. The fourth section empirically examines through the proposed analytical framework Canada’s pursuit of the ISI initiative. The fifth and concluding section makes some practical and theoretical observations about boundary-spanning processes in the context of multitiered jurisdictions.

Theoretical framework: Boundary-spanning through the lens of multilevel governance

The patterns and events characterizing the environment of public management can be described along several dimensions such as whether the environment is stable or unstable, homogenous or heterogeneous, concentrated or dispersed, simple or complex (Daft Citation2001). It also includes factors like the nature of public agencies’ dependence on their operating environment for resources and support (Tompkins Citation2005). While this insight long predates the past two decades (Thomson Citation1967; Mintzberg Citation1983), however, increasingly public managers seek to adapt to accelerating environmental complexities through boundary-spanning activities that often involves establishing favourable links with key elements in the environment, or attempting to shape the environmental domain by changing or aligning partners (Bovaird et al. Citation2019).

The complexity of joint action thus involves several actors across a multi-dimensional setting (Agranoff and McGuire Citation2010). Joint action can be coordinative, cooperative, or collaborative. These joint actions are often formal and informal relationships, with relatively enduring resource transactions, flows and linkages between organizations to pursue mutually beneficial ends (Mazzei et al. Citation2020; Singh and Prakash Citation2010; Oliver Citation1990). Collaborative arrangements represent the most formalized and integrated form of joint action (Kernaghan, Borins, and Marson Citation2000). The present discussion focuses on collaborative contexts of public value co-creation and service delivery through boundary-spanning processes of inter-governmental and inter-organizational partnership arrangements.

The term ‘public value co-creation’ in this paper refers to the joint delivery of public policy programmes by actors drawn from the public, private and non-profit sectors (Crosby, Hart, and Jacob Citation2017). Recent discourses in value co-creation in public service delivery are reinforcing emergent shifts in public administration theory and praxis over the past two decades from narrow intra-organizational and managerial issues to inter-organizational relationships and governance processes (Page et al. Citation2015). These practices place value creation for, and with, citizens and society at the heart of public services delivery (Osborne Citation2018). They also challenge the traditional paradigms of public management theorization and practices (Bovaird et al. Citation2019). This centres the analytical lens of scholars on the boundary-spanning activities of public sector organizations as they engage with non-state actors in strategic processes of co-design, co-production and co-delivery (Mazzei et al. Citation2020; Brandsen, Steen, and Verschuere Citation2018; Poocharoen and Ting Citation2015).

The term ‘boundary spanning’ in the present context is defined as the mechanisms and processes by which policy actors in the public, private and non-profit sectors transcend organizational and institutional silos in pursuit of public value co-creation (Brandsen, Steen, and Verschuere Citation2018; Bovaird et al. Citation2019; Matous and Wang Citation2019). The organizational and institutional silos or boundaries could be horizontal – as prevalent in the tendency of public agencies and private organizations alike to guard their turf – or vertical, as in distinct tiers of jurisdiction in federal systems. Boundary-spanning as a concept in this paper thus refers to the individual and collective efforts of agencies and actors within a given policy domain to link their organizations’ respective programmes and resources into more integrated and synchronized initiatives (Bovaird et al. Citation2019; Tushman Citation1977; Thomson Citation1967; March and Simon Citation1958). The structures and processes that emerge from these efforts could take the form of formal and/or informal interorganizational networks (Bergenholtz Citation2011; Matous and Wang Citation2019; Allen and Cohen Citation1969).

Boundary-spanning as conceptualized in this paper is different from other frameworks of joint action (such as network theory) in that it places emphasis on the strategic agency of actors or ‘policy entrepreneurs’ rather than on the structural configuration of such systems. For instance, this approach is consistent with Bryson et al.’s (Citation2017) call to focus on strategic frameworks of public value co-creation. In this regard, Jochim and May’s (Citation2010, 307) construct of boundary-spanning policy regimes provides an interesting point of reference. For instance, the concepts of issues, ideas, interests and institutions advanced by these scholars resonate with the present framework of strategic agency in boundary spanning ventures. Issues are the defining elements that trigger the agency of actors to change or preserve the status quo. Ideas are central ingredients in actors’ cognitive frames and strategic visioning about desired outcomes in their boundary spanning manoeuvres. Interests are the constellation of players with vested stakes in the outcome of a policy or programme. Institutions are the integrative forces bringing actors together.

However, Jochim and May (Citation2010) construct of boundary-spanning is not applicable to the framework in this paper because they see institutions as ‘integrative forces across elements of policy subsystems’ (p. 313) whereas in the present construct, institutions are seen as integrative forces across organizational boundaries within the same policy subsystem. Moreover, the analysis in this paper is situated within public management scholarship and practice. Boundary-spanning in this analysis thus advances a framework that focuses on the strategic agency of public managers and their non-state partners within the same policy domain.

In keeping with the emphasis on strategic agency, it is worth clarifying the notion of a ‘strategic’ approach to policy joint action. The concept ‘strategic’ denotes developing a continuing commitment to a shared mission or vision among a constellation of actors within a policy subsystem (Poister, Pitts, and Edwards Citation2010). It is about sustaining a collective disciplined focus on a given set of articulated agenda that transcends organizational and jurisdictional boundaries (Durand, Grant, and Tammy Citation2017; Baker Citation2007). It is about directing collaborative and flexible multi-stakeholder relationships in building systems capacities for the creation of public value. The strategic approach focuses on the processes that facilitate the integration of proactive policy design and delivery across a network of agencies and jurisdictions in an ongoing way (Bryson Citation2011). The strategic approach to boundary spanning thus calls attention to how policy stakeholders pursue joint action in the context of operating environmental systems characterized by fragmentation, complexity and constant change.

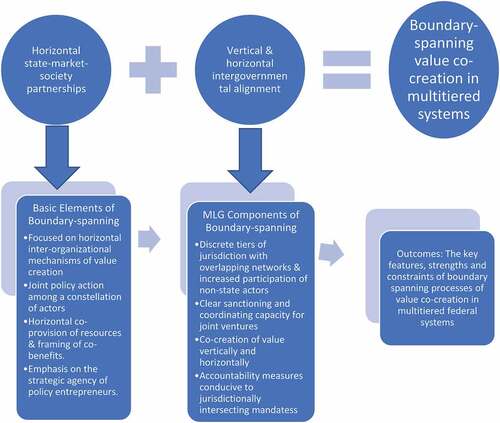

However, multitiered systems face peculiar challenges in value co-creation given their fragmented geographies and highly complex vertical structures (Fenna Citation2019; Fossum Citation2017; Beland and Lecours Citation2016). The institutional environment in the United States, Canada and Australia, for instance, is often more dispersed, heterogeneous, unstable and complex than unitary systems. The inter-jurisdictional and inter-organizational boundary-spanning challenges and opportunities of value co-creation in the multi-scalar institutional contexts of federal and other multitiered systems thus calls for a fresh lens on the boundary-spanning literature. The MLG literature provides such an analytical lens. The rest of this section combines the conventional elements of boundary spanning discourses with insights from the MLG literature to provide an analytical framework conducive to boundary spanning value co-creation in multitiered systems. This framework is illustrated in .

There is burgeoning literature on MLG that has focused attention on the institutional, structural and processual mechanisms of multiscalar collaboration (Hooghe and Marks Citation2003; Stephenson Citation2013; Cargnello and Flumian Citation2017; Bakvis, Brown, and Baier Citation2019; Galvin Citation2019). However, the MLG literature has not cross-pollinated with the boundary-spanning literature despite common themes. The main thread weaving through the fabric of the MLG literature is the recognition that most policy issues (social, economic or environmental) manifest a profound degree of complexity. This complexity tends to dwarf the financial resources, technical expertise, constitutional posturing and jurisdictional authority of any single agency or even level of government, thereby necessitating some form of boundary-spanning joint action in value co-creation and delivery. In Canada, for instance, the pragmatic imperatives of such ‘wicked’ problems have necessitated not only a plethora of state-society partnership arrangements but also profound departures from the formal strictures of federal constitutional provisions (Brock Citation2018; Doberstein Citation2013; Montpetit and Foucault Citation2012).

While originating as a framework to understand multi-scalar governance within the EU and EU member countries (Hooghe and Marks Citation2003; Gänzle Citation2017), the MLG literature has gained considerable traction among scholars examining policy issues and contexts outside of the EU, typically to analyse federal systems or jurisdictions with multiple levels of government (Tortola Citation2017; Howlett, Joanna, and del Río. Citation2017). However, the MLG literature sets itself apart from conventional constructs of intergovernmental relations that are prevalent in the traditional federalism literature (Fenna Citation2019; Fabbrini Citation2017; Fossum Citation2017; Beland and Lecours Citation2016). For instance, regulatory federalism is juxtaposed with MLG to highlight the highly fluid and adaptive character of the latter (Bakvis, Brown, and Baier Citation2019; Cargnello and Flumian Citation2017). One of the key themes in the MLG literature consists of mapping and analysing diverse sets of coordination arrangements among formally independent but functionally interdependent entities that have complex relations to another (Piattoni Citation2018; Howlett, Joanna, and del Río. Citation2017; Tortola Citation2017; Horak and Young Citation2012; Hooghe and Marks Citation2003). MLG thus deals with the challenges and prospects of boundary-spanning mechanisms of policy and programme coordination across multiple jurisdictions and loci (Tortola Citation2017).

Scholars have agreed on two typologies to classify different MLG frameworks – Type 1 and Type 2 (Hooghe and Marks Citation2003; Leo et al. Citation2009; Stephenson, Citation2013). Type 1 MLG is organized according to the principle of subsidiarity, whereby each of the various activities of government are carried out at the lowest level possible (Leo and August Citation2009; Galvin Citation2019). Type 1 conceives of the dispersion of authority to a limited number of non-intersecting jurisdictions. This is similar to classical federalism, which is more closely described by intergovernmental relations (Fenna Citation2019; Brock Citation2018; Fossum Citation2017; Cargnello and Flumian Citation2017).

The Type 2 approach calls for jurisdictional boundary-spanning and argues that many intersecting, task-specific institutional arrangements will allow for mechanisms of joint action in order to maximize synchrony and efficiency (Leo and August Citation2009; Hooghe and Marks Citation2003). Overall, Type 2 has functionally specific jurisdictions, intersecting memberships and many levels of flexible institutional architecture. Type 2 is thus closely related to the literature on boundary-spanning in public value co-creation and co-delivery.

Bache, Bartle, and Flinders (Citation2016) have distilled MLG practices as consisting of four common features: first, decision-making at various territorial levels is characterized by the increased participation of non-state actors; second, the identification of discrete or nested territorial levels of decision-making is becoming more difficult in the context of complex overlapping networks; third, the role of the state is being transformed as state actors develop new strategies of coordination, steering and networking; fourth, the nature of democratic accountability has been challenged and need to be rethought or at least reviewed in the context of such jurisdictionally intersecting mandates. Homsy, Liu, and Warner (Citation2019) have also proposed five components that make up MLG, which are particularly relevant for our construct of boundary-spanning ventures of joint action in public value creation. These are: co-production of knowledge vertically and horizontally, framing of co-benefits, engagement of civil society, provision of capacity, and sanctioning and coordinating capacity.

Combining the above insights from the MLG literature with the conventional elements in the extant literature on boundary spanning would provide an analytical framework conducive to value co-creation in multitiered systems. Distilling the conventional literature on boundary-spanning would result in the following basic elements: First, it focuses on horizontal inter-organizational mechanisms of value creation; second, it calls attention to the mechanics of joint policy action among a constellation of actors; third, it sheds light on horizontal co-provision of resources and framing of co-benefits; and fourth, it places emphasis on the strategic agency of policy entrepreneurs. Adding insights drawn from the MLG literature, we can now conceive of boundary-spanning in multitiered systems as also consisting of the following elements: First, discrete tiers of jurisdiction with overlapping networks along with increased participation of non-state actors; second, clear sanctioning and coordinating capacity for joint ventures involving two or more tiers of jurisdiction; third, co-creation of value not only horizontally but also vertically; and fourth, the importance of accountability measures conducive to jurisdictionally intersecting mandates spanning several levels of government. These combined features from the conventional literature and from MLG would constitute the key features boundary spanning processes of value co-creation in multitiered federal systems. The extent to which actors in these systems manifest the combined features outlined above would determine the strengths and/or constraints of their strategic endeavours of boundary spanning value co-creation.

Using the analytical framework developed above and illustrated in , the empirical analysis in the paper thus addresses the following question: What are the key features, strengths and constraints of Canada’s Innovation Supercluster Initiative (ISI) as a boundary-spanning venture of public value co-creation in a federal system? The empirical section of this paper addresses this question, shedding light on how public officials and non-state actors strategically navigate the complex labyrinth of Canada’s multitiered jurisdiction while seeking, or responding to, the federal government’s pursuit of ISI as a joint initiative in public value creation. The analysis will highlight some of the administrative triumphs and conundrums of value co-creation in Canada’s regionally fragmented and multi-layered federal system, with theoretical and practical implications for understanding similar processes in other multitiered systems.

Research method

The paper employs a configurative idiographic case study design, with a focus on process tracing analytic method (George and Bennet Citation2005a; King, Keohane, and Verba Citation1994). The configurative single case study approach provides a detailed examination of a case to test or apply analytical frameworks that may be generalizable to other cases (Gerring Citation2009). The case study method also lends itself to exploring complex causal relations in which there can be many alternative causal paths to a given outcome (George and Bennett Citation2005b). The outcome under investigation in this paper consists of the key features, strengths and constraints of boundary spanning processes in multitiered federal systems.

As noted in the introduction, the Innovation Supercluster Initiative (ISI) in Canada provides a fitting case study to examine the boundary-spanning contours of public value co-creation in federal systems for two reasons. First, the initiative was conceived as a federal government programme whose implementation involves the cooperation of provincial governments in whose territorial jurisdictions the Superclusters are to be based. Second, the ISI initiative was billed as a public-private venture involving third parties such as innovation system stakeholders drawn from the private sector, research centres and post-secondary institutions. The ISI initiative is thus a typical case from which lessons about boundary-spanning public value co-creation could be drawn and tentatively applied to other multitiered systems.

Considering this manuscript’s theoretic aims to analyse the key features, strengths and constraints of boundary spanning processes in multitiered federal systems, process tracing provides a fitting analytic method. Process tracing, as the name implies, allows the investigator to systematically track developments and underlying patterns in the strategies that actors employ over a given time period in pursuit of their objectives (Collier Citation2011; Schulte-Mecklenbeck, Kühberger, and Ranyard Citation2011). Process tracing involves establishing links between possible causes and observed outcomes through the collection of multiple data points in observing the theoretical implications of a set of actions (Gerring Citation2009; George and Bennett Citation2005b).

The value of process tracing in the present case of Canada’s ISI initiative is enhanced by the fact that it lends itself to synchronic temporal variation of events within a single case. The ISI is a five-year initiative that is subject to the ever-shifting contours of Canadian federalism and changes in state-society-market relations in the country’s liberal democratic system. The analysis in this paper thus traces the ISI policy initiative of the federal government and the responses of relevant actors within the country’s innovation policy subsystem to establish causal processes that could account for the key features, strengths and constraints of its boundary spanning processes.

The data for this paper were collected and analysed over a period of seventeen months (February 2018 to March 2020) by a combination of semi-structured interviews and reviews of media articles and primary (mostly government) documents. The semi-structured interviews were conducted with eighteen individuals (high-level, mid-level, frontline officials and one recently retired officialFootnote1) identified through a purposive sampling strategy to ensure representation from the various levels of government in Canada and across the public, private and non-profit sectors. Interviewees were drawn from public sector agencies (federal, provincial, local, and regional), industry associations and non-profit organizations in Canada.Footnote2

By using data from interviews (along with media articles and primary documents), the study is conducive to human-centred social scientific inquiry such as understanding the strategic agency of actors within a complex policy system. Interview data are also ideal for social scientific inquiries that focus on policy actors’ lived experiences within their operating environment (Palys and Atchison Citation2014). Privileging interview data recognizes that policy entrepreneurs are cognitive beings who actively perceive and make sense of the world around them. In this regard, the understanding generated by semi-structured in-depth interviews employed in this study amounts to ‘verstehen’ (Palys and Atchison Citation2014) – the intimate understanding of human action in complex environments.

Each of the interviews above took an average of one hour and consisted of questions covering the following: The mandates of the interviewees’ organizations; their relationship with key partners in Canada’s innovation policy system; their perception of the constraints and opportunities posed by the country’s intergovernmental structures in attaining their organizational goals; and their strategies in overcoming constraints in pursuing joint action across vertical and horizontal institutional boundaries.Footnote3 Not all the interviews were directly referenced in the discussion below, but together they provided considerable empirical insight that enriched the analysis of the case. The independent review of media articles and government documents (archival reports, commissioned studies and web-based departmental information) provide some measure of triangulation with the semi-structured interviews.

Case: the supercluster initiative in Canada

This section is divided into two parts. The first part provides an overview of the ISI initiative’s key policy and institutional features. The second part dives into an analysis and interpretation of the data to ascertain the ISI’s strengths and weaknesses as a boundary-spanning venture of public value co-creation. This second part builds into highlights of the strategic actions and agency of networks of policy entrepreneurs in the Discussion and Conclusion section of the paper, with implications for public management theory and practice.

Overview of the ISI’s core features

The Canadian federal government announced plans in December 2018 to restructure and modernize its national innovation programme following a comprehensive programme review (Government of Canada Citation2017; Citation2018). This led to the introduction of programmes with major initiatives that now largely define the current landscape of the federal government’s innovation policy. These are the Innovation Superclusters Initiative (ISI), the Strategic Innovation Fund (SIF), Innovative Solutions Canada (ISC), the Clean Growth Hub (CGH) and the Accelerated Growth Service (AGS). For analytical focus and depth, the discussion focuses on the ISI initiative since exploring the details of each of these programmes is beyond the scope of the present discussion. Moreover, focusing on the ISI serves to highlight key features that are common to all the programmes introduced under the 2018 initiative. The aim is to shed light on some of the programme’s implications for boundary-spanning multilevel joint action.

The ISI initiative is designed to support superclusters spanning a wider geographic radius than conventional economic clusters (Government of Canada Citation2017b). The five superclusters are located across major regions of the country: Canada’s Digital Technology Supercluster; the Protein Innovations Supercluster; the AI-Powered Supply Chains Supercluster; the Ocean Supercluster; and the Advanced Manufacturing Supercluster. The ISI programme itself is based on the now globally predominant economic cluster literature (Porter Citation1990; Enright Citation2003) and the literature on national innovation systems (Markusen Citation2003; Doloreux and Shearmur Citation2018; Staber and Morrison Citation2000; Doloreux and Shearmur Citation2018). According to insights from this literature, the ISI is grounded on the premise that the creation of a successful innovation ecosystem involves the development of partnerships between policymakers, entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, post-secondary institutions and other actors (Council of Canadian Academies Citation2018; Globerman and Emes Citation2019). These actors are expected to come together to make a transformative impact on the economy and encourage openness to international opportunities and technological changes (Deloitte Citation2018; Nicholson Citation2018; Schwanen Citation2017; Government of Canada Citation2017b; Randstad Canada Citation2019). The plan, which is labelled as a first of its kind for Canada, intends to expand upon previous federal innovation initiatives through an investment of up to 950 USD million.

The centrepiece of the ISI programme is that it was designed as a policy tool to build public-private institutional platforms that will encourage business-led innovation. Thus, from its inception, the programme mandated a partnership between the public and private sectors. The first and prominent feature of the ISI programme in this regard is its requirement that 50% of funding should come from industry partners (Government of Canada Citation2017b). Underlying this requirement is the goal of overcoming the perceived risk-averse culture of the Canadian private sector by incentivizing businesses to be willing to invest more in new ventures.Footnote4 This feature of the ISI reflects the increased participation of non-state actors in co-production arrangements, including the framing of co-benefits and associated decision-making about programme delivery discussed in the previous section.

The second core feature of the ISI programme is its pursuit of federal-provincial alignment. The ISI programme is framed not just as a horizontal partnership between the federal government and non-state actors but also a vertical mechanism of value co-creation consisting of the federal government consulting with its provincial counterparts while entering into partnership agreements with the private sector (Government of Canada Citation2018). The federal government stipulated when establishing the ISI application process that no provincial government could serve as the lead applicant for a supercluster. Nevertheless, the selected superclusters were ‘encouraged to seek out provincial and territorial programmes to determine how they can contribute to overall activity funding’ (Government of Canada Citation2017, 10).

The third key feature of the ISI initiative is that it seeks to create industry-led consortia that will consist not only of private firms but also industry-relevant research centres, universities and colleges. In this regard, the consortia are to bolster collaborations between private, academic and public sector organizations pursuing private-sector led innovation and commercial opportunities. These consortia consist of networks of regional innovation ecosystems spread across the ten provinces of the country. The consortia are mandated to serve as platforms for the development and facilitation of industry supply chains. In this regard, the ISI initiative has positioned itself to serve as a conduit connecting geographically dispersed regional innovation ecosystems, linking knowledge flows across industries, research centres and post-secondary institutions within a vast network of supply chain management (Cooper Citation2017).

Considering the centrality of vertical as well as horizontal mechanisms of joint action as the key features of Canada’s ISI initiative, the question then arises – what the strengths and constraints of the ISI as a boundary-spanning venture of public value co-creation? The next subsection addresses this question through the lens of the analytical framework developed in the previous section. Using process tracing, the analysis systematically tracks developments and underlying patterns in the strategies that actors employ in pursuit of their objectives.

Results: analysis of the ISI as a boundary-spanning initiative

As noted above, the ISI programme is framed as a vertical and horizontal mechanism, consisting of the federal government consulting with its provincial counterparts and entering into partnership agreements with the private sector. However, from the outset, one of the challenges confronting the programme was the federal public officials’ process for selecting the winning superclusters.Footnote5 For instance, observations from stakeholders across the country charged that ‘the five chosen superclusters seemed rather politically convenient’ as the funding went to regions with prior government engagement and interest (Phillips Citation2018, p.2). The geographical location of each supercluster within five ‘winning’ provinces created tension among the provinces, especially with the exclusion of a major western Canadian province, Alberta, the geographic epicentre of the Canadian oil industry and the heart of the conservative political ideology and movement in the county.Footnote6

Insights from the MLG literature on boundary-spanning ventures in multitiered systems would indicate the need for clarity on the role of discrete tiers of jurisdiction as well as clear sanctioning and coordinating capacity for joint ventures involving these levels of government. While the intention behind the creation of the ISI programme was to build five regional superclusters that focused on provincial needs with presence in Canada’s five major regions, the programme managers’ selection process and funding allotment was perceived as exclusive and inequitable given that not all the provinces were able to participate within the initiative.Footnote7 This omission haunted the legitimacy of the programme in the sense that not all provinces felt included in the ISI as a national inter-jurisdiction network (Sá Citation2018). This raises critical concerns from the standpoint of intergovernmental boundary-spanning ventures in joint value co-creation because a key factor accounting for the success of such initiatives designed to span vertical and horizontal jurisdictional boundaries is to structure them from their inception for a clear articulation of the roles of all relevant tiers of jurisdiction as well as a specification of their respective sanctioning and coordinating capacity for managing the venture.

It is worth noting that policy entrepreneurs from Ontario, Alberta and several other provinces attempted to strategically navigate around this difficulty. This process was pursued by putting together a coalition of multi-provincial applicants who sought to address the problem of perceived exclusion and interprovincial rivalry by pooling partners from across several provinces.Footnote8 Ironically, however, while these multi-provincial applicants made it to the final round of selections, they were not included in the five funded superclusters.

Another key challenge of the ISI programme relates to its espoused pursuit of federal-provincial alignment. This was a laudable aspiration of the ISI’s programme managers from the standpoint of boundary-spanning joint action, even if not all provinces were eventually included. However, the federal public officials conveyed a mixed message in their stipulation that no provincial government could serve as the lead applicant for a supercluster while also encouraging superclusters to seek out provincial and territorial programmes to could contribute to funding (Government of Canada Citation2017a. Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) 2017). This mixed message violates not only the imperative of clear sanctioning and coordinating capacity for joint ventures among tiers of jurisdiction but also undermines the logic of vertical co-creation of value. Joint arrangements for the provision of public value as boundary-spanning ventures in multilevel systems should be accompanied by mechanisms for specifying the co-production among partners, the framing of co-benefits, some degree of shared sanctioning and coordinating capacity among the respective tiers of jurisdiction (Homsy, Liu, and Warner Citation2019). The allowance of provincial and municipal funding of the superclusters thus has the potential for increased resource capacity without the guarantee of better collaboration and alignment between different levels of government.Footnote9

Nonetheless, one must track the processes of strategic reasoning that could account for why the federal officials have chosen to include the provinces in a non-direct role for the funding innovation initiative. One of the permanent features of governance in federal systems is the vicissitudes of policy trajectories resulting from ideological tensions between various levels of government occupied by different political parties. For instance, in the case of the ISI, public managers were mindful that an ideologically centrist Liberal federal government was initiating this programme in the political context of several right-leaning Conservative provincial governments. The history of such intergovernmental ideological tensions and the resulting head-spinning policy reversals from change of government at any one level thus informed fears of a possible lack of compliance over time with established agreement (Crelinsten Citation2017; Wherry Citation2017).

For instance, there have been several cuts made to provincial innovation organizations under Conservative provincial governments in both Alberta and Ontario just as the centrist Liberal federal government was pursuing its ISI initiative (The Globe and Mail Citation2019).Footnote10 An example of this is the Alberta province Premier’s 76 USD-million budget cut for Alberta Innovates (Stephenson Citation2019), and the Ontario Premier’s funding cuts by as much as half of the Ontario Centres for Excellence innovation funding (The Globe and Mail Citation2019). Thus, by the strategic calculation of federal public managers, while the ISl policy is set up as a means to pursue long-term multitiered joint action, broader ideological and political currents of intergovernmental relations could militate against its very logic.

Furthermore, by the federal public managers’ strategic calculation, contesting or decrying provincial funding decisions that go against the goals of the ISI face the risk of bureaucratic officials being perceived as undermining the democratic accountability of provincial decision-making by elected leaders in those provinces. However, the lack of clearly established intergovernmental agreements committing the various orders of government to the programme renders it all too easy for provincial governments to potentially vacillate on their financial contributions without fear of being held accountable by voters in their respective provinces for violating intergovernmental agreements. This highlights the importance of the element of accountability measures conducive to jurisdictionally intersecting mandates spanning several levels of government, as articulated in the analytical framework. Accountability in this context also includes a careful consideration of democratic accountability in such trans-jurisdictional ventures (Bache, Bartle, and Flinders Citation2016). The ISI programme officials’ encouragement of the superclusters to approach the provinces for funding towards the supercluster initiative rests on a fluid and volatile accountability architecture of boundary-spanning joint action.

Another core feature of the ISI programme noted above is its requirement that 50% of funding should come from industry partners (Government of Canada Citation2017b). This is a laudable strategy to incentivize businesses to be more willing to invest more in new ventures.Footnote11 This provision is also consistent with the conventional literature on boundary-spanning which highlights key elements such as horizontal co-provision of resources and framing of co-benefits. Attending this funding arrangement of the ISI is the provision that the day-to-day administration of the programme is to be provided by officials in the Canadian government’s Ministry of Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED). At the same time, the superclusters are expected to enjoy considerable autonomy in their operations (Government of Canada Citation2017b).

This provision is consistent with co-production arrangements involving inter-organizational mechanisms of value creation whereby governments put in place associated decision-making arrangements with nonstate actors in programme delivery. The ISI initiative seems to have accomplished the 1:1 ratio of co-investment within public–private partnerships, and each cluster is spending the time to ensure that they have a board of directors and a bureaucratic structure.Footnote12 These elements would seem consistent with the conventional literature on horizontal inter-organizational mechanisms of value creation as well as mechanism for joint policy action among a constellation of actors. They reflect the transformation of the role of the state as it pursues boundary-spanning state-society partnership strategies of coordination, steering and networking while also seeking to protect its policy autonomy (Breznitz, Ornston, and Samford Citation2018; Mazzucato Citation2018). However, as noted in the theoretical section earlier, such horizontal inter-organizational mechanisms of value creation necessitate greater attention to the mechanics of joint policy action involving a constellation of nonstate actors. In particular, there are intrinsic boundary-spanning tensions between the goals of ‘involvement’ and ‘autonomy’. For instance, process tracing of the requirement for the matching funds to come from businesses during the application phase of the ISI project revealed that some private sector stakeholders labelled the application process as a quite restrictive exercise when the government claims to be ‘building a joint strategy based on true partnership’.Footnote13

The ISI programme’s commendable aim for increased participation of non-state actors seems inadequate when with respect to the MLG literature’s call for clear sanctioning and coordinating capacity that reconciles the tensions between ‘involvement’ and ‘autonomy’ in joint action among partners. In light of these emergent tensions, some observers (Bergman and Geiger Citation2018; Seddon and Usmani Citation2017; Edler Citation2019) have recommended establishing an equal relationship that focuses on co-investment within public–private partnerships. They also call for a precise method to be outlined for the evaluation of policy goals, an independent monitoring body of experts, and a system of rationalized cluster support.

Moreover, while the MLG literature highlights the importance of vertical accountability measures conducive to jurisdictionally intersecting mandates spanning several levels of government, as articulated in the analytical framework, this logic of accountability could be extended to horizontal inter-organizational mechanisms of value creation between government and its nonstate partners. However, there are no clear outlines in the ISI for the evaluation of policy goals, and there is no regulation for how each cluster must be set-up.Footnote14 Furthermore, there are also no clear guidelines as to how or whether the public–private partnerships will continue to exist after the first funding period ends. Moreover, despite the business-led institutional logic of the ISI programme’s delivery and the federal government’s attempt to set strict rules for the creation of superclusters, the diametrically opposed cultures of a democratically accountable and process-driven public sector on the one hand, and that of an atomistic, competitive and result-oriented private sector on the other continue to generate intrinsic tensions in such partnerships.

The ISI initiative in Canada thus presents a case of a bold pursuit of a boundary-spanning joint action in public value co-creation. Through the combined lens of the conventional literature on boundary-spanning as well as the MLG literature, the ISI’s core features could be said to have some provisions for horizontal co-provision of resources and framing of co-benefits. However, tracing the process of programme delivery through the lens of the key actors reveal that these provisions are not well articulated vertically among tiers of jurisdiction or horizontally with nonstate partners. Federal public managers along with their provincial counterparts and nonstate partners continue to deal with the challenges of institutional fissures and potential entanglements in the programme’s delivery.

The above challenges from the standpoint of boundary-spanning ventures of joint action are exacerbated by the vertically fragmented nature of Canada’s innovation funding architecture in a nation known for its vast geography and assertive regionalism (Tamtik Citation2016). Reinforcing these tendencies is the fact that regional innovation hubs often consist of spatially delimited constellations of postsecondary institutions, research centres, industry partners and municipal public sector actors. From their vantage point, these actors are often more concerned about the geographically proximate parameters of innovation clusters in their respective industrial corridors rather than conceptually nebulous national innovation systems advanced by federal managers of the supercluster initiative. Thus, while federal officials seem preoccupied with the distinct features of Canada’s national innovation programmes, the network of actors within regional innovation systems are preoccupied with how upper-tier programmes fit into the practical imperatives of their immediate local concern. Ironically, these pragmatic considerations have incentivized informal bottom-up boundary-spanning initiatives that have proven more resilient than the formal top-down initiatives. This phenomenon provides the best illustration of the significance of the strategic agency of policy entrepreneurs, as emphasized in the boundary spanning literature. Through further process tracing, the rest of this section tracks developments and patterns in the strategies that actors employ in pursuit of their objectives.

One of the key strengths of the ISI initiative is its design of industry-led consortia consisting of private firms, research centres, universities and colleges. These platforms serve as conduits through which actors bolster collaborations between private, academic and public sector organizations through networks of regional innovation ecosystems spread across the ten provinces of the country. In this regard, the ISI platforms serve as conduits for actors to strategically mitigate feelings of exclusion among some provinces. They also present immense opportunities for purposive knowledge exchange among innovation stakeholders by providing the institutional architecture for a strategic adaptation to rapid changes in a knowledge-intensive global economy.

The boundary-spanning opportunities presented by the superclusters as regionally embedded platforms for the strategic agency of policy entrepreneurs include the following: First, they provide actors a relative degree of stability over time while also allowing them to exercise some degree of flexibility and adaptability to the shifting exigencies of their operating environment, especially in instances of intergovernmental ideological tensions and policy reversals (Bergman and Geiger Citation2018); second, they serve as government-mandated proactive structures through which actors strategically facilitate, catalyse or integrate collective actions within the market rather than merely passively playing a supportive bureaucratic role as with stand-alone agencies. The ISI as boundary-spanning platforms thus operate in a context of ‘distributed action’, meaning that they can serve as a canopy under which a myriad set of semi-independent actors pursue their strategic interests.Footnote15

The significance of the above processes is that they highlight the boundary spanning strategic agency of policy entrepreneurs in multitiered systems. They shed light on how public managers and their nonstate partners make accommodations for much of the deficiencies in the formal provisions of the ISI by forging informal vertical and horizontal inter-organizational mechanisms of value creation. To further illustrate this point using process tracing, one of the informal mechanisms by which innovation cluster network actors have responded to the aforementioned challenges of federalism and regionalism is by initiating regularized consultations with funding agencies from upper-tier jurisdictions.Footnote16 A key source of the resulting multilevel synchronization, therefore, is the strategic effort of these network of actors from local regions across the country who from their spatial/geographical lens tend to hold a more holistic view of resource alignment. These actors construct narratives of local economic reinvention that make sense for their mixed bag of funding support from federal and provincial agencies. It is thus the strategic manoeuvres of regional and local innovation networks that serve as the boundary-spanning ‘glue’ binding together Canada’s otherwise fragmented institutional architecture. The seemingly smooth operations of the boundary-spanning MLG processes in Canada’s innovation policy environment is, therefore, largely a function of the adaptive and pragmatic manoeuvres of regionally embedded constellations of innovation policy entrepreneurs seeking to leverage much-needed resources and expertise from upper levels of government.

However, despite all the merits of strategic inter-jurisdictional calibration, one critical policy and institutional lacunae in this context of pragmatic accommodation is the absence of proper democratic and fiscal accountability systems to trace which programmes may be poorly designed and therefore in need of recalibration. When innovation clusters are succeeding, such strategic manoeuvres of bottom-up multi-scalar alignments, pragmatic accommodations and informal processes seem to suffice and even look ideal in a policy environment that thrives on creativity and entrepreneurial opportunism (Canada Citation2020Innovation Project 2017). However, when funded programmes fail to meet the stated policy objectives, as is sometimes the case, these informal and opaque entanglements leave all sides shifting blame. In this regard, the challenge is to apply lessons from the MLG literature in preserving the merits of strategic, fluid and informal bottom-up boundary-spanning adaptations while establishing appropriate accountability measures conducive to jurisdictionally intersecting mandates to provide oversight of major policy initiatives such as the federal government’s ISI programme.

Another limitation in the current strategic approach to the boundary-spanning multi-scalar alignment of Canada’s innovation policy is that local and non-state actors are still vulnerable to the vacillating whims, ideological pendulums and shifting policy priorities in events of regime changes after major elections. A process tracing of events following Ontario’s recent provincial election illustrates this point. This election brought to power the Progressive Conservative government which, compared to the ousted Liberal government, has demonstrated less enthusiasm for investing in innovation programmes (The Globe and Mail Citation2019). Since the election, the subsequent funding cuts and programme restructuring in Ontario have raised questions about the province’s innovation policy and shaken the morale of some local innovation ecosystem actors.Footnote17 Thus, in the absence of clear framing of binding co-funding arrangements along with the sanctioning and coordinating authority of parties to the joint ventures, political and ideological vacillations seem just as pernicious to informal and bottom-up mechanisms of boundary-spanning MLG (McDougall Citation2017).

In a nutshell, notwithstanding the institutional gaps and policy inconsistencies in Canada’s ISI programme, tracing the processes of boundary-spanning ventures of joint action in Canada’s innovation system reveals that it has largely been a function of the strategic agency of a constellation of policy entrepreneurs. Despite their institutional vulnerability to the vicissitudes of federal politics, these informal mechanisms of bottom-up boundary-spanning serve as a form of corrective that policy entrepreneurs employ to navigate the dysfunctional tendencies in a multitiered and geographically fragmented system. For public managers operating within Canada’s kaleidoscope of regional economic configuration, these strategic manoeuvres even provide a myriad of institutional ‘laboratories’ that serve as platforms of policy experimentation, learning and transfer across regions.

However, given that political and ideological vacillations seem just as pernicious to informal and bottom-up mechanisms of boundary-spanning value creation, this would imply the need for public managers to pay attention to how more formal programme delivery and monitoring mechanisms that can balance informal bottom-up strategic calibrations. Such two-pronged approaches can better position public managers to address some of the political vacillations and institutional fragmentation that threaten the integrity and sustainability of value co-creation ventures in multitiered federal systems.

Conclusion

The analysis above has attempted to highlight the core features of Canada’s recent Innovation Superclusters Initiative (ISI) initiative and then examine its strengths, weaknesses, challenges, and pragmatic accommodations through the conceptual lens of boundary-spanning value co-creation in multitiered systems. The paper’s main objective was to highlight through its focus on the ISI initiative as a typical case study how the analytical lens of MLG could enrich the concept of boundary spanning value co-creation in public administration theory and practice.

The case provides a lens for understanding through process tracing how policy entrepreneurs navigate strategically across institutional boundaries in multitiered systems. Process tracing in this case involved tracking developments and patterns in the strategies that actors employed to navigate the complex contours of Canadian federalism and state-market relations. These developments in Canada’s ISI initiative also provide an interesting window on the interplay between how policy entrepreneurs navigate the lines between the spatial distribution and geographic configuration of nationally framed policies on the one hand and the complex vertical architecture of federal systems on the other.

The answers to the research question about the key features, strengths and constraints of Canada’s ISI as a boundary-spanning venture could be summarized as follows: First, the delivery of the ISI programme was constrained by the process of choosing the five superclusters that was perceived to have left out some provinces. The resulting political tensions presented public managers and their nonstate counterparts with institutional fissures that they must navigate in delivering the programme. Second, even though the ISI programme’s espoused pursuit of intergovernmental federal-provincial alignment was a laudable aspiration, its lack of provisions clearly spelling out the sanctioning and coordinating authority of the various orders of government left public managers exposed to the ideological and jurisdictional quagmires of pursuing boundary-spanning joint action in the country’s federal system.

Third, the ISI programme’s requirement that 50% of funding should come from industry partners rests on a justifiable rationale of a joint provision of capacity and shared responsibility. This joint funding initiative is consistent with the boundary-spanning literature regarding co-provision of resources. However, the lack of clarity in the framing of co-benefits, including funding partners’ respective authority, left programme managers finding the right balance between close involvement with non-state actors on the one hand and maintaining policy autonomy to ensure democratic and fiscal accountability on the other.

On a more positive note for public managers in multitiered systems, the pragmatic realities of Canada’s ISI initiative as a boundary-spanning multijurisdictional venture illustrates multi-scalar processes in which public managers and their nonstate partners pursue programme alignment that are regionally grounded within myriad governance arrangements, with incremental changes and adaptations reflecting specific configurations of joint actions unique to each regional innovation system. Multilevel boundary-spanning joint policy action is thus a function of the strategic manoeuvres of pragmatically minded networks of policy entrepreneurs that serve as the main undercurrents of institutional adjustments in an otherwise fragmented federal system.

Furthermore, for public managers in multitiered systems, Canada’s ISI initiative illustrates the immense opportunities for within-country policy learning, transfer and exchange. As the case above indicates, the strategic adaptation of economic governance platforms that are grounded within the spatial entity of cities and regions can and do serve as ‘laboratories’ of learning. For other policy areas, future research could explore how these ‘laboratories’ of strategic multilevel experimentation may take different forms and processes.

In terms of theoretical implications, while acknowledging the rich body of works on boundary-spanning in the extant literature, this paper was premised on the argument that how policy entrepreneurs navigate strategically across boundaries in multilevel governance is still in need of further elucidation. The conventional literature on boundary-spanning has highlighted basic elements such as horizontal inter-organizational mechanisms of value creation, horizontal co-provision of resources and framing of co-benefits, and the strategic agency of policy entrepreneurs navigating the boundaries separating government and its nonstate counterparts. Insights from the MLG literature, however, situate boundary-spanning within the context of multitiered systems by highlighting critical elements such as discrete tiers of jurisdiction with overlapping networks, the need for clear sanctioning and coordinating capacity for joint ventures involving two or more tiers of jurisdiction, and the imperative for thinking about accountability measures conducive to jurisdictionally intersecting mandates. These combined elements from the conventional literature and from MLG arguably constitute a more promising analytical lens for investigating the key features, strengths and constraints of boundary spanning value co-creation ventures in multitiered systems. It provides a more holistic picture of how policy entrepreneurs navigate strategically across boundaries in such systems.

Therefore, while boundary-spanning trends have become pervasive in public administration research and practice, there is still much work to be done to understand their full implications for public managers in multitiered jurisdictions. As these trends have opened exciting new frontiers of opportunities and challenges in public service delivery (Bovaird et al. Citation2019; Osborne Citation2018; Brandsen, Steen, and Verschuere Citation2018; Poocharoen and Ting Citation2015; Pierre and Peters Citation2005), public managers in multilevel systems face peculiar challenges given the highly complex vertical structures of their operating environment.

Boundary-spanning ventures of public value co-creation and co-delivery in federal systems imply the transformation of management toolkits as policy entrepreneurs pursue and develop new strategies of coordination, steering and networking while contending with the imperative to respect and preserve governments’ policy autonomy (Crosby, Hart, and Jacob Citation2017; Page et al. Citation2015). For instance, the central concept of accountability in public administration would need to be revisited to render it more relevant for contexts of jurisdictionally intersecting mandates in value co-creation.

In closing, insights drawn from the MLG literature have provided a lens for analysing some of the managerial triumphs and conundrums of boundary-spanning value co-creation in a multitiered system. The MLG literature also provides a useful lens for understanding how public and private actors could interface across scales of jurisdiction and the boundaries separating the public and private sector to co-create and co-deliver value for citizens and society. It sheds some light on the vertical and horizontal dimensions of public management as top-down and bottom-up boundary-spanning mechanisms to overcome chronic coordination problems in multitiered systems.

There is one important caveat worth noting for the purpose of generalizability across policy fields and beyond Canada. Canada’s ISI initiative has served as a typical case study to illustrate the challenges and opportunities public managers and their nonstate counterparts encounter in their delivery of a national innovation programme initiative within the institutional context of centrifugal forces of federalism and regionalism. However, future research could expand on this work by applying the framework advanced in this paper to other policy fields and other multitiered systems. Better still, future studies could undertake comparative small-n studies of boundary-spanning value creation in federal systems to systematically isolate through process tracing or similar methods contingent factors peculiar each country’s political system in the bid to highlight the core features of how policy entrepreneurs navigate strategically across boundaries in multitiered systems. In a similar vein, future studies could also compare boundary-spanning value creation between federal systems on the one hand and other multitiered systems like the European Union on the other.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Charles Conteh

Charles Conteh, PhD Professor, Department of Political Science, Director, Niagara Community Observatory, Brock University, Ontario, Canada

Brittany Harding

Brittany Harding, MA, Research Assistant, Department of Political Science, Research Associate, Niagara Community Observatory, Brock University, Ontario, Canada

Notes

1. This recently retired official is included because he was a key figure in the design of the ISI program. His insights were invaluable in shedding light on the federal government’s original vision of how the ISI program was to be delivered in partnership with other levels of government and nonstate actors.

2. See Appendix A for list of interviewees cited in the text. For confidentiality purposes, the names and titles of the interviewees are withheld.

3. See Appendix B for the list of interview questions.

4. Interviews with Canadian Ministry of Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) official, and with NGen, the Advanced Manufacturing Supercluster (one of the five superclusters) based in Ontario, November 2019

5. Interview with the province of Ontario’s Ministry of Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade (MEDJCT), November 2019

6. Interview with a university Innovation Commercialization official, Alberta, December 2019

7. Interview with a senior official in the province of Manitoba Ministry of Economic Development and Training, December 2019

8. Interview with a senior official in the province of Manitoba Ministry of Economic Development and Training, December 2019

9. Interview with an Economic Development Officer, Niagara Regional Municipality, Ontario, January 2020

10. Interview with a university Innovation Commercialization official, Alberta, December 2019

11. Interview with a senior staff at the Ontario Chamber of Commerce, January 2020

12. Interview with a staff at Innovate Niagara, a Regional Innovation Centre (RIC) in Ontario, January 2020

13. Interview with a senior staff at the Ontario Chamber of Commerce, January 2020. Similar opinions were expressed in other interviews.

14. Interview with NGen, the Advanced Manufacturing Supercluster (one of the five superclusters) based in Ontario, November 2019

15. Interview with NGen, the Advanced Manufacturing Supercluster (one of the five superclusters) based in Ontario, November 2019

16. Interview with Communitech, a Regional Innovation Centre (RIC) based in Ontario, February 2020

17. Interviews with Communitech and MaRS Centre, two Regional Innovation Centres (RICs) based in Ontario, February 2020.

18. For confidentiality purposes, the names and titles of the interviewees are withheld.

19. Follow up questions vary based on the responses of the interviewees.

References

- Agranoff, R., and M. McGuire. 2010. “A Jurisdiction-Based Model of Intergovernmental Management In.” U.S. Cities. Publius 28 (4): 1.

- Allen, T J, and S Cohen. 1969. “Information Flow in R&D Labs.” Administrative Science Quarterly 14 (1): 12–19. doi:10.2307/2391357.

- Bache, I., I. Bartle, and M. Flinders. 2016. “Multi-level Governance.” In Handbook on Theories of Governance, edited by Ansell, Christopher K., and Jacob. Torfing, 486–498. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Baker, D. 2007. Strategic Change Management in Public Sector Organizations. Oxford: Chandos.

- Bakvis, H, DM Brown, and G. Baier. 2019. Contested Federalism: Certainty and Ambiguity in the Canadian Federation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Beland, D, and A. Lecours. 2016. “Ideas, Institutions and the Politics of Federalism and Territorial Redistribution.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 4: 681. doi:10.1017/S0008423916001098.

- Bentzen, T. Ø. 2020. “Continuous Co-creation: How Ongoing Involvement Impacts Outcomes of Co-creation.” Public Management Review 1–21. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1786150.

- Bergenholtz, C. 2011. “Knowledge Brokering: Spanning Technological and Network Boundaries.” European Journal of Innovation Management 14 (1): 74–92. doi:10.1108/14601061111104706.

- Bergman, A., and M. Geiger 2018. How Will Canadian Technology Clusters Continue to Thrive and Remain Competitive in Managing STEM Migration for Innovation and Growth?Accessed March 2020. http://migrationforinnovation.info/upload/634548/documents/7A21E1357CF968D6.pdf

- Best, B., S. Moffett, and R. McAdam. 2019. “Stakeholder Salience in Public Sector Value Co-creation.” Public Management Review 21 (11): 1707–1732. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1619809.

- Bovaird, Tony, Sophie Flemig, Elke Loeffler, and Stephen P. Osborne. 2019. “How Far Have We Come with Co-Production - and What’s Next?” Public Money & Management 39 (4): 229. doi:10.1080/09540962.2019.1592903.

- Brandsen, Taco, Trui Steen, and Bram Verschuere. 2018. Co-Production and Co-Creation : Engaging Citizens in Public Services. London: Routledge.

- Breznitz, D., D. Ornston, and S. Samford. 2018. “Mission Critical: The Ends, Means, and Design of Innovation Agencies.” Industrial and Corporate Change 27 (5): 883–896. doi:10.1093/icc/dty027.

- Brock, Kathy. 2018. “Canadian Federalism in Operation.” In Issues in Canadian Governance, edited by Jonathan Craft and Amanda Clarke, 109–126. Toronto: Emond Publishing.

- Bryson, J., A. Sancino, J. Benington, and E. Sørensen. 2017. “Towards a Multi-actor Theory of Public Value Co-creation.” Public Management Review 19 (5): 640–654. doi:10.1080/14719037.2016.1192164.

- Bryson, J.M. 2011. Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations: A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organizational Achievement. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Canada 2020 Innovation Project. (2017). Towards an Inclusive Innovative Canada Report. canada2020.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/020317-EN-FULL-FINAL.pdf

- Cargnello, D. P., and M. Flumian. 2017. “Canadian Governance in Transition: Multilevel Governance in the Digital Era.” Canadian Public Administration 60 (4): 605–626. doi:10.1111/capa.12230.

- Collier, David. 2011. “Understanding Process Tracing.” PS, Political Science & Politics 44 (4): 823–830.

- Cooper, R. 2017. Supply Chain Development for the Lean Enterprise: Interorganizational Cost Management. London: Routledge.

- Council of Canadian Academies. 2018. Competing in a Global Innovation Economy: The Current State of R&D in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Expert Panel on the State of Science and Technology and Industrial Research and Development in Canada, Council of Canadian Academies.

- Crelinsten, J. 2017. Why Superclusters May Be Doomed to Failure. Toronto, Canada: Globe and Mail.

- Crosby, Barbara, Paul ‘t Hart, and Torfing Jacob. 2017. “Public Value Creation through Collaborative Innovation.” Public Management Review 19 (5): 655–669. doi:10.1080/14719037.2016.1192165.

- Daft, R. L. 2001. Essentials of Organization Theory & Design. Cincinnati, Ohio: South-Western College Pub.

- Deloitte. 2018. “Canada’s Competitiveness Scorecard Measuring Our Success on the Global Stage.” Business Council of Canada. Accessed 18 January 2020. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ca/Documents/finance/finance-bcc-deloitte-scorecard-interactive-aoda.en.pdf

- Doberstein, C. 2013. “Metagovernance of Urban Governance Networks in Canada: In Pursuit of Legitimacy and Accountability.” Canadian Public Administration 56 (4): 584–609. doi:10.1111/capa.12041.

- Doloreux, D., and R. Shearmur. 2018. “Moving Maritime Clusters to the Next Level: Canada’s Ocean Supercluster Initiative.” Marine Policy 98: 33–36. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2018.09.008.

- Durand, Rodolphe, R. M. Grant, and L. M. Tammy. 2017. “The Expanding Domain of Strategic Management Research and the Quest for Integration.” Strategic Management Journal 38 (1): 4–16. doi:10.1002/smj.2607.

- Edler, J. 2019. A Costly Gap: The Neglect of the Demand Side in Canadian Innovation Policy. IRPP Insight 28: Institute for Research on Public Policy. Montreal. https://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A-Costly-Gap-The-Neglect-of-the-Demand-Side-in-Canadian-Innovation-Policy.pdf.

- Enright, Michael J. 2003. “Regional Clusters: What We Know and What We Should Know.” In Innovation Clusters and Interregional Competition, edited by Johannes Bröcker, Dirk Dohse, and Rüdiger Soltwedel, 99–129. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Fabbrini, S. 2017. “Intergovernmentalism in the European Union. A Comparative Federalism Perspective.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (4): 580–597. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1273375.

- Fenna, A. 2019. “The Centralization of Australian Federalism 1901–2010: Measurement and Interpretation.” Publius 49 (1): 30–56. doi:10.1093/publius/pjy042.

- Fossum, J. 2017. “Federal Challenges and Challenges to Federalism. Insights from the EU and Federal States.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (4): 467–485. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1273965.

- Galvin, P. 2019. “Local Government, Multilevel Governance, and Cluster‐based Innovation Policy: Economic Cluster Strategies in Canada’s City Regions.” Canadian Public Administration 62 (1): 122–150. doi:10.1111/capa.12314.

- Gänzle, S. 2017. “Macro-regional strategies of the european union (EU) and experimentalist design of multi-level governance: The case of the EU strategy for the danube region.” Regional & Federal Studies27(1): 1–22.

- George, A. L., and A. Bennett. 2005a. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- George, Alexander L., and Andrew Bennett. 2005b. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences, 214–215. London: MIT Press.

- Gerring, J. 2009. “The Case Study: What it is and What it Does.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics, edited by Carles Boix and Susan C. Stokes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Globerman, S., and J. Emes. 2019. Innovation in Canada: An Assessment of Recent Experience. Fraser Institute. Toronto. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/innovation-in-canada_0.pdf.

- Government of Canada. 2017b. Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED). Innovation Superclusters Program Guide: Innovation for a Better Canada. Ottawa.

- Government of Canada 2018. “Building a Nation of Innovators. Innovation for a Better Canada.” Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISEDC). Accessed January 2019. https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/062.nsf/eng/h_00105.html

- Government of Canada 2017a. Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED). 2017. Innovation Superclusters Initiative. Accessed 20 January 2020. https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/093.nsf/eng/home

- Guarneros-Meza, V., & Martin, S. 2016. “Boundary Spanning in Local Public Service Partnerships: Coaches, advocates or enforcers?” Public Management Review 18(2): 238–257.

- Homsy, G., Z. Liu, and M. Warner. 2019. “Multi-level Governance: Framing the Integration of Top down and Bottom-Up Policymaking.” International Journal of Public Administration 42 (7): 572–582. doi:10.1080/01900692.2018.1491597.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2003. “Unravelling the Central State, but How? Types of Multilevel Governance.” American Political Science Review 97 (2): 233–243.

- Horak, M., and Y. Robert. 2012. Sites of Governance: Multilevel Governance and Policy Making in Canada’s Big Cities, 3–25. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Howlett, M., V. Joanna, and Pablo del Río. 2017. “Policy Integration and Multilevel Governance: Dealing with the Vertical Dimension of Policy Mix Designs.” Politics and Governance 5 (2): 69–78. doi:10.17645/pag.v5i2.928.

- Jochim, A.E., and P J. May. 2010. “Beyond Subsystems: Policy Regimes and Governance.” Policy Studies Journal 38 (2): 303–327. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00363.x.

- Kernaghan, K., Sanford F. Borins, and Brian Marson. Institute of Public Administration of Canada. 2000. The New Public Organization. Toronto: IPAC =IAPC.

- King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba. 1994. Designing Social Inquiry, 86. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Leo, C., and M. August. 2009. “The Multilevel Governance of Immigration and Settlement: Making Deep Federalism Work.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 42 (2): 491. doi:10.1017/S0008423909090337.

- March, J, and H. Simon. 1958. Organisations. New York: Wiley.

- Markusen, A. 2003. “Fuzzy Concepts, Scanty Evidence, Policy Distance: The Case for Rigour and Policy Relevance in Critical Regional Studies.” Regional Studies 37 (6–7): 701–717. doi:10.1080/0034340032000108796.

- Matous, P., and P. Wang. 2019. “External Exposure, Boundary-spanning, and Opinion Leadership in Remote Communities: A Network Experiment.” Social Networks 56: 10–22. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2018.08.002.

- Mazzei, M., S. Teasdale, F. Calò, and M. J. Roy. 2020. “Co-production and the Third Sector: Conceptualising Different Approaches to Service User Involvement.” Public Management Review 22 (9, September 1): 1265–1283. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1630135.

- Mazzucato, M. 2018. Mission-oriented Innovation Policy and Dynamic Capabilities in the Public Sector. 787-801. Accessed 15 February 2020. https://academic.oup.com/icc/article-abstract/27/5/787/5089909

- McDougall, J. 2017. “How to Strengthen Canada’s Innovation Performance.” The Globe and Mail. Accessed 21 February 2020. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-commentary/how-to-strengthen-canadas-innovation-performance/article36692994/