ABSTRACT

Through a thematic analysis on major themes researched in network governance and collaborative governance, this paper identifies the entangled relationship between these two research streams. We note the common and distinct themes in these two research streams that reveal four entanglements in the research and practice of network governance and collaborative governance. We propose future research could focus more on the implementation and comparative studies, adopting microperspectives of collaborative governance and network governance at the grass-root level in juxtaposition with interorganizational and institutional levels that are led by non-public actors for value co-creation in different institutional contexts.

Introduction

Even though the concept of governance is now firmly embedded in our understanding of public administration, there is a continuing tendency to conflate and confuse different governance concepts. Network governance (NG) and collaborative governance (CG) are such core concepts in governance literature that have received extensive attention and oftentimes used interchangeably but the similarities and differences between them remain unclear. A conceptual overlap is clearly existed between NG and CG when they are embedded in the theoretical orientation entertained by governance. For example, NG is defined as ‘entities that fuse collaborative public goods and service provision with collective policymaking’ (Isett et al. Citation2011, p. i158) that is based on the principles of trust, reciprocity, negotiation, and mutual interdependence among actors (Provan and Kenis Citation2008). These same elements of NG are also the characteristics in the definitions of CG (Fadda and Rotondo Citation2020). For instance, Ansell and Gash (Citation2008, 544) define CG as ‘a governing arrangement where one or more public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders in a collective decision-making process that is formal, consensus-oriented, and deliberative and that aims to make or implement public policy or manage public programmes or assets’. Both terms emphasize the collective decision-making process for public services delivery based on normative principles such as trust, power-sharing, diversity, consensus, inclusiveness, deliberativeness, egalitarian (Provan and Kenis Citation2008; Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh Citation2012). However, such an overlap between the two concepts might bring conceptual confusions and might further impact the significance of these two concepts in supporting a general theorization of governance, therefore, clarification and disambiguation of these two terms are needed for subsequent theory development in the governance-related research.

This article attempts to explore the close relationship between NG and CG. Specifically, we ask two research questions: what are the common or different concerns between NG and CG leading to a conceptual overlay? How will the current conceptualization of NG and CG merge together to prompt future governance research and guide managerial practices? These two research questions are meaningful in at least three ways. First, we believe that NG is a structural concept emphasizing more on pluricentric coordination as opposed to unicentric hierarchies or multicentric markets, while CG is a process concept emphasizing how a diverse set of actors engage in collaboration in order to govern a particular problem field. Thus, a comparative analysis of the themes studied in NG and CG literature could explicate the extent and nature of the conceptual overlay of these two core concepts in the governance context. Second, using an in-depth thematic analysis of NG and CG literature, we could identify similarities and differences between these two research streams, from which some general observations could be theorized to denote the entanglements in the research and practice of network governance and collaborative governance that could move the two research streams towards a general theorization of governance in public administration. Thirdly, an in-depth understanding on the similarities, differences and entanglements of NG and CG research could inform the managerial practice for public administration practitioners, especially when they engage in service delivery design and public decision making that involve multiple stakeholders of a society.

Network, collaboration, and governance

Network governance research, many scholars argued, was originated from the academic interests on corporatism, state theory, policy network, co-implementation and co-delivery of services, when a variety of interest groups or stakeholders in the political and policy system (network) defuse conflict among them and create instead broad consensus on policies, contributing to the co-delivery of public services (Molina and Rhodes Citation2002; Ottaway Citation2001). Collaborative governance research, on the other hand as argued by scholars, is rooted in classic liberalism and civic republicanism (Cohen Citation2018; Perry and Thomson, Citation2004). According to the classic liberalism, the motivation of collaboration is self-serving, and according to the civic republicanism, collaboration can signify values of trust and mutual understanding (Cohen Citation2018). Thus, CG grew out of both theories of deliberative democracy and the concern for participation of civil society in public governance. In recent two decades, the field of public administration is transforming itself when our societies have become multi-centred, the political and administrative authority is becoming more fragmented, and our governmental or private actors do not have the capacity alone to solve the increasingly complex and dynamic societal problems. In this context, both NG and CG capture and conceptualize this transformation in governance, thus constitutive to governance research (Sørensen, Bryson, and Crosby Citation2021).

The concept of governance, despite its wide usage in recent two decades, does not have a definitive definition in the discourse of public administration. Frederickson (Citation2007) argued that the first uses of ‘governance’ in public administration came from Harlan Cleveland (Citation1972). Cleveland (Citation1972) proposed some essential characteristics of governance when he explained that ‘the organizations that get things done will no longer be hierarchical pyramids with most of the real control at the top. They will be systems – interlaced webs of tension in which control is loose, power diffused, and centers of decision plural. Decision-making will become an increasingly intricate process of multilateral brokerage both inside and outside the organization which thinks it has the responsibility for making, or at least announcing, the decision. Because organizations will be horizontal, the way they are governed is likely to be more collegial, consensual, and consultative’ (Cleveland Citation1972, 13). The kind of organizing envisioned by Cleveland reflects the initial characterization of governance in public administration: the modes, manner, patterns and actions of governing that expands beyond government by the inclusion of all possible stakeholders such as market and civil society; the boundaries between public, private and civil society become blurred due to their interdependent roles and relations; and the policy-making and service delivery do not rest on command or authority but on interaction, negotiation and trust (Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh Citation2012; Stoker Citation1998; Rhodes Citation1996). More specifically, governance denotes a set of coordinating activities between the public, private and civic sectors that influences policy-making and public service delivery in solving public problems (Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2006; Frederickson et al. Citation2015).

Typologically, governance could be depicted as networks. Since networks are structures of interdependence involving multiple actors for solving problems or achieving collective objectives that cannot be accomplished by a single actor (Rhodes Citation1996; Agranoff and McGuire Citation2001), it depicts the situations when political or administrative actors need to interact with others to acquire resources, getting political alliance and address problems that go beyond the boundary of one actor. The network governance is a response to complex problems, environmental uncertainty and task complexity, which use social mechanisms for coordinating and safeguarding the exchanges to reduce transaction costs (Jones, Hesterly, and Borgatti Citation1997). In the context of the public service delivery, network governance is usually equated as governance since governance takes place within networks of complex interactions between public and non-public actors (Sørensen and Torfing Citation2018; Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016; Provan and Kenis Citation2008).

Conceptually, governance could be semanticized as collaboration in its essence. The nature of governance signifies ‘that the role of governmental and nongovernmental institutions is critical, and that the future of public service delivery will be characterized by collaborative relationships between both types of institutions’ (Frederickson et al. Citation2015, 246). Collaborative governance, consequently, has been defined as the collaboration of different organizations from public, private and civic sectors working together as stakeholders based on deliberative consensus and collective decision making to achieve shared goals that could not be otherwise fulfilled individually (Ran and Qi Citation2019; Ansell and Gash Citation2008; Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh Citation2012). Public administrators often use collaboration as a strategy to improve governance, and implement governance as collaboration (Roiseland Citation2011) in service delivery by sharing information, resources and capabilities through negotiation, and jointly creating rules and structures to govern their relationships (Thomson, Perry, and Miller Citation2009).

Both NG and CG focus on governance that leads to an entangled relationship between them that potentially hinders them to be fully developed as distinct concepts, and further impedes their ability to contribute to a general theorization of governance in the discourse of public administration. To reduce the conceptual ambiguity, we engaged in a systematic assessment of the use of these two concepts in literature to delineate their similarities and differences in public administration field and to provide some observations on how their entangled relationships signal the trends of the field in understanding governance related issues.

Review methodology

Literature search and coding strategy

Several criteria were used to establish the review scope. First, we selected journals that are generally regarded as the top-tier research outlets in the public administration field based on their most recent 5-year impact factor in 2018 ISI Journal Citation Reports. We chose the journals whose impact factor is larger than 2.5. We then selected journals in general public administration domain as opposed to journals that specialize in policy areas, because research in policy journals is more likely to study policy networks, not NG or CG. This led to seven journals ():

Table 1. Journals selected for review.

Second, we used ISI Web of Science to search the relevant articles in these journals. We expanded the research period from the earliest available date of any articles indexed by Web of Science up to 30 November 2020. The search setting in the database were: Title = Collaboration or Collaborative Governance or Intergovernment Relations or Inter-organization or Network Governance or Governance Network or Network or Cooperation or Coordination. Time span = All years. Types = Articles. This research in the above seven journals yielded 545 articles.

Third, we read the titles and abstract of these 545 articles. At this stage, we were able to exclude articles that focus on information network and social network. This is because the articles on information network and social network mainly focused on the information systems or individual’s social network, rather than the collaborative network of organizations. Finally, 242 relevant articles on NG and CG were identified to be included in this review.

We then coded the 242 articles. The coding has three steps. In step 1, we classified which articles were in the category of NG and which were CG by using each article’s title, abstract, and keywords as the basis for categorization. If one article did not use NG or CG in its title, abstract or keywords, we read the full text of the article to make a judgment. We periodically exchanged notes on the classification of articles and discussed until the agreement was reached. In step 2, we read the full text to extract the main themes researched in an article. To increase the coding reliability, we respectively read the articles and used the Nvivo software to make notes about the main themes in each article. Based on Crobach’s alpha (α = 0.90), the level of agreement between the two coders was high and well above the threshold of 0.70 (Castaner and Oliveira Citation2020). For the inconsistent codes, we exchanged notes and discussed until an agreement was reached. For example, one coder coded examples of ‘participant-governed network’, ‘lead organization-governed network’, and ‘network administrative organization’ as the theme of ‘network structure’, but the other coder named them as ‘governance mode’. After comparing the examples supporting each other’s codes, we decided to code them as ‘governance mode’ since the theme of ‘network structure’ should focus on the degree of differentiation and integration in the network, such as ‘density-based integration’ and ‘centralized integration’. In step 3, we grouped some themes coded in step 2 into a larger classification if they denote the same thematic meaning. For example, ‘outcomes’, ‘effectiveness’, ‘benefit’ and ‘cost’ are all grouped into the theme of ‘network/collaborative performance’.

Sample description

Our sample of 242 articles shows an increasing trend for the studies of NG and CG in the top public administration journals (see ) with a substantial increase of NG and CG studies published in the most recent decade (2010–2020), signalling the leading journals are more and more receptive to NG and CG research. Articles about NG are more than CG. PMR, JPART, PA and PAR published the most NG and CG studies.

Table 2. Number of studies by journal and decade.

We explored whether the selected journals originated from Europe (PA and PMR) or the United States (ARPA, Governance, IPMJ, JPART and PAR) differed in the relative use of NG and CG as a manifestation of different research traditions. We found that the use of NG or CG was not conditional on the location of the journal’s headquarters (χ2 = 4.550, p > .10 [df = 4]), indicating the selected journals are inclusive of different research traditions and have a global reach.

Main themes in NG and CG research

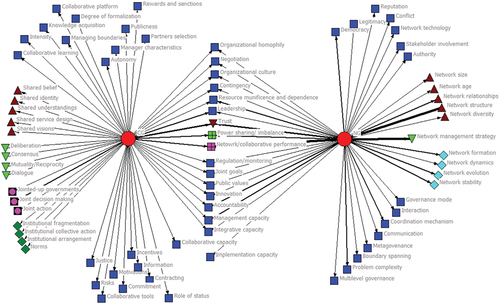

To provide an overview of the main themes addressed by NG and CG studies, we used the UCINET software to visualize a two-mode network to delineate the main research themes and their relationships among NG and CG (see ). In , the nodes in the network are the themes while the links show the relationships or flows between the nodes and NG or CG. The thickness of the links denotes frequency of the themes and high frequency means these themes were given more attention by scholars. shows 53 themes of CG and 42 themes of NG in the 242 articles. Among them, 30% of CG themes are overlapped with 38% of NG themes.

Specifically, we find that both NG and CG focus on resource dependence, leadership, trust, power, accountability, and network/collaborative performance. The differences in research themes are that NG pays more attention to network properties/structural elements (e.g. network structure, network size, network age, network relationships and network diversity), network development (network formation, network dynamics, network evolution, and network stability), and network management strategy, while CG focuses on sharing (e.g. sharing information, sharing belief, sharing identity, sharing understanding, sharing service design and sharing visions), collaborative characteristics (e.g. deliberation, consensus, mutuality/reciprocity and dialogue), joint efforts (e.g. jointed-up governments, joint decision making, and joint action), and institutional design (e.g. institutional fragmentation, institutional collective action, institutional arrangement and norms). We also find that journals originated from Europe (PA and PMR) and the United States (ARPA, Governance, IPMJ, JPART and PAR) differ in the distribution of some themes. PA and PMR published more themes on legitimacy, leadership and innovation, while the ARPA, Governance, IPMJ, JPART and PAR published more on the themes of network dynamics and evolution, network properties, incentives, and sharing. For example, PA and PMR published 77% leadership theme while journals originated from US published 23% leadership theme. However, the difference in the overall distribution of these themes is minor, and all journals have focused on the topics of network/collaborative performance, trust, power, institutional arrangement, network management and network structure.

The most common themes between NG and CG

There are 16 common themes between NG and CG, 5 of which are most common (resource dependence, leadership, trust, power and network/collaborative performance).

Resource dependence is the most common themes across NG and CG research. Some exemplar research in this area covers overcoming lack of resources as one of the major motivations for interorganizational collaboration. Researchers have the consensus that the interorganizational cooperation is a consequence of resource interdependence and when faced with complex problems, interdependent actors have to exchange resources to achieve their common goals (Fadda and Rotondo Citation2020; Sapat, Esnard, and Kolpakov Citation2019). Resources are often used as rational tools for resource holders to activate and influence partners, and partners with munificent resource will have high power and collaborative advantage.

Leadership is emerged as the second most common theme across NG and CG research. Many NG and CG studies explored the relationship between leadership (e.g. personal characteristics, styles, behaviours, capacities and contingencies) and collaborative/network processes and outcomes (Crosby and Bryson Citation2005; Torfing and Ansell Citation2017; Cepiku and Mastrodascio Citation2021). Research has shown that leadership can construct networks, empower members, facilitate communication and interaction, minimize conflicts, align the interest of members, build trust, encourage creativity, model new roles, promote systematic thinking and ultimately improve collaborative/network performance.

Trust is the third most common theme in both NG and CG studies. Trust is an important antecedent and cornerstone to collaboration, especially in collaborations that are not mandated by government but rather relying on the mobilization of partners’ resources towards the achievement of common goals (Lundin Citation2007; Vangen, Hayes, and Cornforth Citation2015). NG and CG researchers mainly focus on three aspects of trust: trust building as a critical first step for collaboration and how factors, such as agency’s reputation, successful past cooperation, frequency of interactions and network embeddedness, can contribute to trust-building (Lambright, Mischen, and Laramee Citation2010). The second is on measuring trust. Trust has been proposed to be measured by the quality of relationships in formal contracts or less formal referral ties (e.g. strength of ties or multiplexity) (Isett and Provan Citation2005). The third general research aspects in trust focuses on exploring how trust improves quality of network/collaboration.

Power is the fourth most common theme in NG and CG studies. In general, power in interorganizational collaborations originates from authority, resources and legitimacy (Purdy Citation2012) and power imbalance is likely to exist in any forms of collaborations since power is always unequally distributed across partners (Ran and Qi Citation2019). Some research identified that formal authority (e.g. legitimate right to make decisions) and control over critical resources (e.g. financial and expertise resources) are two sources of power imbalances (Hermansson Citation2016). Less powerful partners may need to bargain with the more powerful ones to achieve a fair influence on collaborative processes for gaining voluntary acceptance of collective decisions.

Performance is the fifth most common theme across NG and CG research. Literature has focused on two aspects of performance: how to measure it and what factors affect it. Different perspectives and indicators can be used to evaluate the performance of certain aspects of network/collaboration, rather than assessing whether a collaboration as a whole is effective or ineffective (Ran and Qi Citation2018). For example, some used procedural indicators to measure performance, such as degree of democracy, deliberation, building trust and enabling adjustment to proposed actions (Cristofoli and Markovic Citation2016) while others used output and outcome indicators to measure performance (e.g. resource utilization, efficiency, effectiveness and equity) (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016). Moreover, network/collaborative performance has been explained by various structural and contextual factors, such as network integration, external control, system stability, trust, network coordination approaches and resource munificence (Herranz Citation2010; Markovic Citation2017; Provan and Milward Citation1995) and how the various factors combined to affect the different levels and dimensions of performance (Cristofoli and Markovic Citation2016; Fadda and Rotondo Citation2020).

The distinctive themes in NG or CG

Distinctive themes in NG

Network properties

Network properties refers to the characteristics of a network (size, age, relationship, structure, density, centrality, diversity, etc.) as a result of the design of the network (e.g. roles, procedures, and processes of interaction) and the types of relationships among network members (e.g. consensual, lead agency and a hybrid form) (Milward et al. Citation2010). Network properties are considered as important determinants of network performance. NG literature has focused on two aspects of network properties: what factors affect network properties, and how network properties affect network performance. For example, policy context, resources and contingent contextual factors have been used to explain network characteristics (Lee, Rethemeyer, and Park Citation2018; Provan and Huang Citation2012). Larger network size and more diversified network members would increase the complexity of network and uncertainty in it, and thus affecting network effectiveness (Span et al. Citation2012). Literature also shows that network properties when combined with other factors (e.g. network complexity, cooperative mechanisms and network management), will jointly affect network sustainability, outcomes, effectiveness and performance (Cristofoli and Markovic Citation2016; Kapucu and Garayev Citation2012).

Network management

Network management is a deliberate process to facilitate interorganizational interactions among network members (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016). NG research mainly focused on a wide variety of network management strategies, activities and behaviours, such as activating members, constructing conditions conducive to coproduction, framing the work of cooperation, managing collaborative processes, creating new organizational arrangements, connecting strategies and mobilizing organizational resources (Agranoff and McGuire Citation2001; Klijn, Steijn, and Edelenbos Citation2010). Some research also examines the relationship between network management and network performance. For example, O’Toole and Meier’s public management model (Citation1999) emphasized that the positive effect of managerial activities should be understood in a contingent setting, that is, the network management should be combined with other factors (e.g. trust and network structure) to affect the network performance (Cristofoli and Markovic Citation2016).

Network development

Network development refers to the network formation, dynamics, evolution, and stability. Networks have four development stages: activation/formation, collectivity, institutionalization and stability/decline/reorientation (Imperial et al. Citation2016). Many NG studies focused on conditions for network development. For example, Krueathep, Riccucci, and Suwanmala (Citation2010) used five determining factors such as the nature of the programmesand management capacity to explain when and why networks are likely to be formed. Scholars also found that network formation and diffusion follow a contingency logic promoted by resources, network environment and internal coordination among members over time (Isett and Provan Citation2005; Provan and Huang Citation2012). Compared with hierarchy, network is more flexible and dynamic, thus inherently short-term (Wachhaus Citation2012). However, existing literature further points out that network evolution needs to be stable in design, functioning and direction, because stability is an important factor for network success (O’Toole and Meier Citation2004). Provan and Lemaire (Citation2012) further discussed the stability-dynamic paradox and proposed that networks need to be relatively stable at their core while maintaining flexibility at the periphery.

Distinctive themes in CG

Sharing

Sharing should be conceptually fundamental to both NG and CG, however, we cannot extract ‘sharing’ as the keyword from NG literature, comparing with sharing as the most prominent characteristic of CG literature (e.g. shared information and knowledge, shared power, shared belief, shared identity, shared visions and shared motivations, etc. among partners to establish a mutual understanding of common tasks and values in collaboration). The shared understanding can be seen as a part of collaborative learning process (Ansell and Gash Citation2008; Kelman, Hong, and Turbitt Citation2013) where stakeholders interact through collaborative learning and knowledge sharing to increase consensus on policy beliefs and public service goals (Leach et al. Citation2014). Literature has focused on how sharing affects collaborative behaviours among partners (Choi and Robertson Citation2014, Citation2019), how information sharing leads to long-term collaboration with shared identity, beliefs and core values (Thomson and Perry Citation2006; Conner Citation2016), and how the interaction among partners will promote information sharing, foster trust, internal legitimacy and shared commitment, and thus generating shared motivation (Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh Citation2012).

Deliberation and dialogue

CG differs from traditional command and control arrangements in its use of deliberation and dialogue in developing mutual understanding to reach consensus among partners (Choi and Robertson Citation2014; Amsler Citation2017). Existing studies mainly focus on whether and how deliberation among actors causes their behavioural change (e.g. Doberstein Citation2016), whether and under what conditions a deliberation process can reach a consensus-oriented decision outcome that is more acceptable to actors and stakeholders (e.g. Robertson and Choi Citation2012), and whether and how deliberation effects on policy innovation (e.g. Torfing and Ansell Citation2017).

Joint efforts

Joint efforts allow actors achieve joint goals at a community level that could not be achieved without the collaboration (Vangen, Hayes, and Cornforth Citation2015). In return, joint goals lead to joint efforts of collaboration, such as joint strategic thinking and joint organizational structure and design (Silvestre, Marques, and Gomes Citation2018). Literature in CG mainly focused on what factors affect joint efforts and how joint efforts promote collaboration. For instance, trust, goal congruence and collaborative capacity should exist simultaneously to promote joint actions (Lundin Citation2007; Sullivan, Barnes, and Matka Citation2006). Increasingly informal and formal joint procedures can reduce transaction costs and administrative burdens (Hartlapp and Heidbreder Citation2018), help build trust among partners (Ansell and Gash Citation2008), promote resources sharing and achieve larger degree of consensus (Purdy Citation2012).

Institutional design

CG is an organizational manifestation of institutional design and arrangements for interorganizational relationships (Skelcher, Mathur, and Smith Citation2005). Institutions signal to potential collaborative partners a policy orientation and commitment by the government (Smith Citation2009) that might reduce transaction costs, risks and information barriers for collaboration. (Casula Citation2020). Literature in CG mainly examines how institutional arrangements affect collaboration. For example, stable institutions can help mitigate cognitive deficiencies, and thus can facilitate collaboration by allowing public managers and politicians to commit to a course of action in a policy arena (Smith Citation2009). Overall, institutional design in CG emphasizes ground rules that all actors need to conform and therefore increase the procedural legitimacy of collaborative process.

Entanglements between NG and CG

The thematic analysis on the common and distinct themes in NG and CG literature not only provides us a clear picture on the similarities and differences between these two research streams that suggests the degree of conceptual overlay, but also reveals the entanglements between research in NG and CG that expose to some degree the potential conceptual quagmire found in the governance literature. These entanglements point out potential directions scholars and practitioner could aim their attention to in helping to bring conceptual clarity surrounding collaborative governance and network governance in particular and governance theories in general. We noted both NG and CG tend to focus more and more on the governance in the interface between public, private, non-profit and civil society, where juxtaposition of different levels (individual, organizational, interorganizational and institutional) contributes to the tensions and paradoxes in governance that necessitates a contingency perspective.

Entanglement 1: both NG and CG focus on the interface between public, private, non-profit and civil society

Interface refers to the arrangements organized to interconnect or link different organizations, functions, and inner and outer environments (Edelenbos, van Schie, and Gerrits Citation2010). The literature of NG and CG centralizes substantially around governance in the interface among public (administration/policy), private (businesses), non-profit and civil society. shows 72% and 67% studies investigate the interface governance in NG and CG literature, respectively. Most studies on interface governance focus on the interface between public and public or the interface with more than two categories of actors (e.g. public-private-non-profit or public-private-civil society).

Table 3. Interface governance.

The public-public cooperation mainly explores the vertical and horizontal collaboration within public sectors, including inter-governmental networks, inter-national governance, inter-local agreements, inter-municipal cooperation and regional governance. The governance of interface with more than two categories of actors mainly focuses on solving more complex issues, such as public health, emergency management, and environment protection, which needs more actors to collaborate. The public-private interface mainly studies the infrastructure governance where the private participation has been attracted effectively to address the infrastructure or public services issues that involve user charges, such as toll roads and sewage treatment. In contrast, the public-non-profit, public-civil society, non-profit-civil society interfaces mainly focus on the social service provision without user charges (such as welfare) that attracts non-profit and civil society participation. suggests some possible research directions in further investigating dyadic collaborations in public service delivery, especially how public agencies or non-profits collaborate with civil society, how non-profits collaborate and interact with private businesses, and how non-profit collaborate with other non-profits in addressing complex social issues. Similarly, the research in quadrilateral relations could also be strengthened since we are in dire need to understand how public, private, non-profit and civil society all together collaborate in addressing wicked social problems. Such studies will bring worthy insights on the essence of governance, to reflect the changing nature of public administration in our time when all stakeholders have to interact to solve a societal problem or provide a public service. It will also link public administration research more coherently with other administrative sciences, such as business management research or non-profit research.

Entanglement 2: both NG and CG focus on juxtaposition of different levels

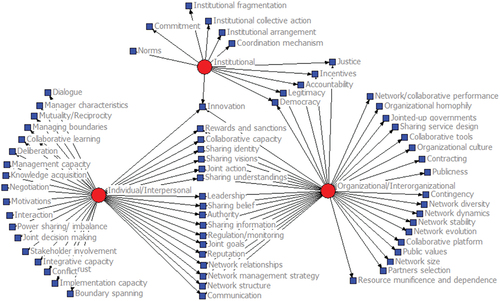

NG and CG research pays significant attention to the juxtaposition of different levels of governance: individual/interpersonal (micro), organizational/interorganizational (meso) and institutional/international (macro). illustrates how research themes (see ) are distributed in micro-meso-macro levels. Some themes are discussed mainly in one single level. For example, dialogue and manager characteristics are handled mainly at the individual/interpersonal level. Organizational homophily and joined-up government are mainly discussed in the organizational/interorganizational level. Institutional fragmentation and institutional arrangement are mainly studied in the institutional level. Other themes are discussed cross two levels. For example, joint action has been used as both individual joint action and organizational joint action. Very few themes in literature connect all three levels. We only coded innovation discussed in individual, organizational and institutional levels.

It should be noted that the categorization of the identified themes into different levels of individual/interpersonal, organizational/inter-organizational and institutional is meant to provide a systematic organization of how the different themes are currently handled in the literature at different levels of scope and implication. However, this categorization also suggests that the identified themes should not be exclusively studied at a certain level as there could be many interconnectivity and embeddedness amongst these themes across different levels. For example, learning or knowledge is currently mainly studied at micro individual/interpersonal level in literature, but it will provide us more insight if these themes could be investigated at mesoorganizational level or macro institutional level. More research could be developed by re-focusing a theme at a different level than the current level discussed in literature. Moreover, a theme at a single level could also be researched in juxtaposition with different levels, such as the micro-foundation of meso/macro level themes or macro-manifestation of micro/meso-level themes. Such research on juxtaposition of different levels is gaining importance for two reasons: it provides micro-level conceptual rigour for macro-level empirical and practical relevance; and it will strengthen our understanding on how governance in juxtaposition of different levels functions, such as how meso/macro-concepts are emerged from micro level concepts when doing social aggregation, and how micro-level concepts are manifested in meso/macro-levels to impact governance.

Entanglement 3: interfaced and juxtaposed governance is full of tensions or paradoxes

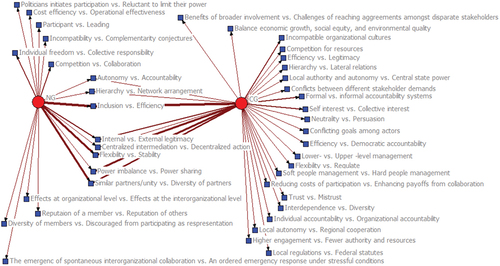

Paradoxes could be understood as the ‘interdependent and persistent tensions (that) are intrinsic to organizing’ (Schad et al. Citation2016, 10). According to Smith and Lewis (Citation2011, 387), paradox proposes ‘contradictory yet interrelated elements (dualities) that exist simultaneously and persist over time; such elements seem logical when considered in isolation but irrational, inconsistent, and absurd when juxtaposed’. Scholars have highlighted two components of paradoxes: (1) underlying tensions caused by ‘elements that seem logical individually but inconsistent and even absurd when juxtaposed’, and (2) ‘the two sides of any contradiction exist in an active harmony, opposed but connected and mutually controlling’ (Peng and Nisbett Citation1999, 743; Hargrave and Van de Ven Citation2017; Lewis Citation2000; Smith and Lewis Citation2011). Under these assumptions, tensions arising from paradoxical situations are oppositional, inconsistent and conflictual on the one hand, but on the other hand, such tensions are also interconnected, synergistic and reciprocally established. Thus, the paradox perspective emphasizes the imperativeness of consciously acknowledging and accepting the tension that often exists when a paradoxical situation presents itself with a view to mitigating and repressing such tension as much as possible. In NG and CG, when different actors are interfacing and different levels are juxtaposing in interorganizational collaborations, it will naturally confront with different interests, preferences, resources, and powers, that undergo a continuous process of negotiation and contestation over allocation of social and material resources and political power, thus tensions, conflicts, dilemma, and paradoxes are heightened. We analysed how the research themes (see ) are related to conflicts, uncertainty, inconsistencies, disagreements, incompatibilities, and tensions by focusing on the challenges, problems, or issues caused by assumptions, principles, mechanisms, and outcomes in collaborative governance and network governance as revealed either within an article or between articles. We then linked these contradicting assumptions, principles and mechanisms to form relevant paradoxes. At the end of this analysis, a combined total of 41 pairs of paradoxical circumstances were generated ().

The tensions and paradoxes in the NG and CG literature mainly focus on three issues: What are these tensions/paradoxes? Why there are tensions/paradoxes? And how to handle tensions/paradoxes? shows the types of tensions, conflicts, and paradoxes we coded in the 242 NG and CG articles. Five basic tensions or contradictory logics (paradoxes) have been often discussed by both NG and CG (the thickest line between NG and CG): Efficiency versus inclusiveness, internal versus external legitimacy, flexibility versus stability, unity versus diversity, and power imbalance versus power sharing. For example, competing values, such as individual freedom and collective interest, transparency and privacy, rights and obligations, and efficiency and equity, cause paradoxes (Yang Citation2020). How these tensions and paradoxes are managed and balanced will be critical for network/collaboration performance (Provan and Kenis Citation2008). Reducing tensions through hybrid governance model and network/process management maybe useful (Chen Citation2021; Sørensen and Torfing Citation2009; Waardenburg et al. Citation2020).

Although a few research discussed some tensional or paradoxical characteristics of NG or CG thus helped to bring awareness to the issue in governance, to the best of our knowledge, there is no comprehensive framework proposed to systematically examine the tensional or paradoxical factors of network governance or collaborative governance. Such a framework could categorize as the first step the different paradoxes and tensions such as paradoxes between normative principles of NG and CG, paradoxes between normative principles and real-life practice in NG and CG, and paradoxes in real-life practice of collaborative/network governance. We also noticed that the literature has analysed reasons on why tensions or paradoxes occur in NG or CG, yet most of these reasons are tied to certain tensions or paradoxes in a specific case of collaboration. It might be fruitful to analyse the essential nature of ‘wicked problems’ tackled by multiparty collaboration as the root cause for such tensional or paradoxical situation to reveal essence of tensions or paradoxes beyond the specific context of collaborative arrangement. Furthermore, literature either suggests some solutions to deal with these tensions or paradoxes by focusing on handling certain tension/paradox in a specific collaborative context, making them less generalizable, or stops at general thoughts about tensions/paradoxes, missing more actionable strategies to guide collaborative practices. Vangen (Citation2017) discussed how a paradox lens can contribute to the development of practice-oriented theory of collaboration and help promote collaborations in practice, thus there is a need to zoom in concrete managerial and administrative principles in handling tensions/paradoxes that can be applied across different governance contexts, such as having a dynamic equilibrium mindset and adopting contingency and holistic approach.

Entanglement 4: tensional or paradoxical governance necessitates a contingency perspective

Since interorganizational collaborations cannot avoid paradoxical and conflictual situations, success in NG and CG are considered elusive, depending upon many inner and outer factors (e.g. contexts, nature of tasks, institutions, leaders and resources) (Prentice, Imperial, and Brudney Citation2019; Alford and Hughes Citation2008), which effectuated many research exploring the key question of how to determine which approach is more suitable for which circumstance under what conditions for which stakeholders. Thus, the mediating effects, moderating effects and other contingency effects are becoming increasingly important in NG and CG research. For example, Ran and Qi (Citation2018) proposed a system of contingency factors influencing the relationship between power sharing and the effectiveness of collaborative governance. Trust is often used as a moderator or mediator between independent (e.g. network management strategies) and dependent variables (e.g. network performance) (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2016; Siddiki, Kim, and Leach Citation2017; Ran and Qi Citation2019). Collaborative processes (e.g. joint decision making and resources sharing) was shown to mediate the effects of antecedents (e.g. resources and organizational legitimacy) on network outcomes (Chen Citation2010).

Contingency approach focuses on improving a system’s flexibility, elasticity, and resilience when managing tensions or paradoxes in collaboration rather than pursuing easily transferable solutions; and dynamic equilibrium among conflicting aspects inherent in governance requires a sufficient level of flexibility. A lot of contingency factors, such as resource dependence, institutional environment, structure of collaborative network, are critical when considering the priority of some demands above others when addressing tensional or paradoxical situation in collaboration. Understanding the contingencies enables policymakers and practitioners to design and manage the network and collaborations strategically and purposefully to achieve the common goals (Markovic Citation2017).

Research agenda

We envisage a few more research opportunities that leverage the similarities, differences, and entanglements that we identified in our review. Future research could focus more on the comparative studies, adopting micro perspectives of CG and NG at the grass-root level in juxtaposition with interorganizational and institutional levels that are led or mediated by non-public actors (private-led, non-profit led, or citizen-led) for value co-creation (or forbearance) in different institutional contexts.

NG and CG at grassroot level

In our thematic analysis, we noted that many NG and CG research has its focus on macro dimensions of large-scale projects, such as strategic (Ansell and Gash Citation2008; Siddiki et al. Citation2015; Lewis Citation2011; Hendriks Citation2008), cultural (Cohen Citation2018), institutional (Edelenbos, van Schie, and Gerrits Citation2010; Roiseland Citation2011; Smith Citation2009) aspects of large-scale CG and NG projects at metropolitan, regional, country or international levels (Chen Citation2010; Hermansson Citation2016; Krueathep, Riccucci, and Suwanmala Citation2010; Silvestre, Marques, and Gomes Citation2018; Casula Citation2020). This line of research is significant in helping us understand macro dynamics in large collaborative or network governance projects; however, it should be noted that a significant number of collaborative efforts in public sector happens primarily at the ordinary day-to-day practices of a traditional government agency, most likely at grassroot levels. The empirical reality of the primary daily practices that comprise governance of collaborative or network nature has not yet captured the major attention of scholars in CG and NG.

The empirical reality of the role of collaboration in the daily administrative life of a government agency doing numerous small scale collaborative projects or networked arrangement at grassroot level directly touches on citizens’ life and impacts governance effectiveness at grassroot level, thus needs focused attention in public administration. It is especially important to understand how citizens, non-state, and non-market stakeholders at the grassroot level impact the effective governance in a diverse and complex environment where power is diffused and conflicts are unavoidable, which can only be achieved through collaboration and partnership of all grassroot stakeholders, especially those previously excluded from the decision-making processes. A dire need is called upon for more empirical evidence that provides rich contextual and process insights and that touches on the dynamics and essence of collaboration at grassroot level. Scholars then could enrich their understanding and possibly generate a better theorization that could match the complexity and sophistication of the realities of daily managerial and administrative work with theories.

Leading roles played by non-public actors in NG and CG

When governance implies a set of coordinating activities between the public, private, and civic sectors that influence policy-making and public service delivery in solving public problems, who is leading these activities becomes a central issue. Leading a cross-sector collaboration denotes the general phenomenon of bringing partners together, guiding the cooperation, and ensuring all parties achieving collective goals as well as their individual goals. This leading role should be played by a certain actor that has unique professional resources and strategic positions to motivate other stakeholders, facilitate the formation of partnership, build trust among stakeholders, design how stakeholders will interact, gain commitment to partnerships, and effectively manage the partnership. In our examination of various themes related to these activities, we noted literature has focused on a predominant leading-role played by a governmental actor or actors.

It is true that majority of collaborations and governance networks has been led and mediated by governmental actors. However, researchers have noticed a growing role played by non-governmental actors in leading collaborations (Cheng Citation2019; Wang, Qi, and Ran Citation2022). It will be fruitful to explore under what conditions non-public actors could emerge to play a leading-role in a collaboration or in a network. Especially, scholars have not paid enough attention to the agency of ordinary citizens in the NG and CG literature. Can ordinary citizens play a leading role in public service delivery and policy implementation? If they can, what are the mechanisms and contingencies for citizens to be a leading partner of a collaborative arrangement, rather than just recipients of the local policy-making and service provisions? More of such research is called upon to further our understanding on how, when and why non-public actors lead a collaborative effort.

Designing and implementing CG and NG against their enigmatic nature

Insights of scholars on the conflictual and paradoxical nature of NG and CG capture the complexity and challenges facing collaborative practices and point to some potential research agenda in designing and implementing CG and NG. In this regard, we envisage broad fields for research and practice tackling the enigmatic nature of collaboration-based governance. For example, participants in NG and CG usually expect mutually beneficial interdependencies, and the achievement of one participant’s goals and interests depends on other participants’ actions (Thomson, Perry, and Miller Citation2009; Wood and Gray Citation1991). However, NG and CG in practice usually witness conflicts in goals and interests (Vangen and Huxham Citation2012), tensions between loyalty to parent organizations and accountability to the collaboration (Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2006; Huxham et al. Citation2000), and differences in strategies and tactics of addressing problems (Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2006). Mutually beneficial interdependence often yields to competitions between participants in obtaining more resources in collaboration or having more influences on decision making. It is then important to investigate how to design and implement an effective strategy to handle this reality.

Another challenge in designing and implementing CG and NG is balancing participants’ autonomy and network’s authority. Different from top-down hierarchical arrangements, there is often no formal hierarchical authority in collaborative arrangement, and participants usually are able to maintain their autonomy (Provan and Kenis Citation2008; Thomson and Perry Citation2006; Thomson, Perry, and Miller Citation2009). However, some administrative structure or a central position with authority, is oftentimes necessary and even required to coordinate communication, organize and disseminate information, and keep various participants alert to jointly determined rules for the collective goals (Thomson and Perry Citation2006; Thomson, Perry, and Miller Citation2009). Scholars are still unclear on how to design and implement a collaborative arrangement in which the obedience to the authority of a collaboration will not reduce participants’ independent power associated with their autonomy. Related, more research needs to be done in finding a strategic solution to the eternal problem of participants’ struggle on being accountable to whom and for what (Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2006; Koliba, Mills, and Zia Citation2011). Representatives of participating organizations are often subject to conflicting accountabilities to their own organizations and to the collaborative network in which they are involved. How to balance the potential conflicts in these two accountabilities needs focused research.

When designing and implementing NG and CG, artificially-designed or naturally-developed systems often impose significant challenges. Artificial systems are designed by people with its artificial spatial and temporal boundaries where natural systems are developed naturally without artificial spatial or temporal boundaries. When these two systems mismatch, NG and CG will be doomed to failure (Qian Citation2020). For example, a political election system is designed artificially with its relatively short-term cycles while environmental system is a natural system with long-term processes. When the mission of a collaborative arrangement is to deal with an environmental problem but is inevitably affected by a short-term political-election cycle, the effectiveness of the collaborative arrangement will face the danger of failure (Kallis, Kiparsky, and Norgaard Citation2009). Also, spatial mismatch between artificial and natural systems also generates a dilemmatic situation. For example, when artificially designed administrative regions (cities, counties, and states) collaborate or form a network to address problems across artificial boundaries (such as economic development, labour market, poverty alleviation), how to design and implement a strategy so that artificial boundaries will not restrict collaborative efforts, and participants could think and act beyond artificial boundaries need scholars’ focused attention.

Value co-creation or forbearance

Both NG and CG research has focused on the study of network/collaborative performance and outcomes. We noticed that literature has focused on performance measurements (such as degree of democracy, deliberation, building trust, enabling adjustment to proposed actions, resource utilization, efficiency, effectiveness, and equity) or on factors affecting its performance or outcomes (such as network integration, external control, system stability, trust, network coordination and resource munificence). Undoubtedly, NG and CG generate both tangible outcomes (e.g. the effective delivery of the public services) and intangible outcomes such as the co-creation of certain values both for service users and for society (Osborne, Nasi, and Powell Citation2021; Dudau, Glennon, and Verschuere Citation2019), but very few studies have focused on the potential values co-created through NG and CG as one major indicator of its performance. Value co-creation, in the field of public administration, is generally understood as an interactive creation by the combined actions of all stakeholders such as public service providers and users (Osborne, Nasi, and Powell Citation2021; Wright Citation2015). We envisage more research focusing on values to examine the mechanisms, processes, logics, drivers, and barriers of value co-creation when multiple stakeholders engage in a collective and deliberative decision-making process that aims to make or implement public policy or manage public programmes or assets.

It will also be interesting to investigate when NG and CG stop creating or promoting values. We noted when we studied the enigmatic nature of NG and CG that they can create beneficial outcomes but might as well result in forbearance of certain paradoxical values (such as forbearing a balance between inclusiveness of all stakeholders and efficiency of the decision-making; or enduring the compromise between autonomy of participants and authority of the network). We highly encourage researchers to explore why and how paradoxical values might be foreborne by actors during the collaboration processes, and under what conditions certain values are compromised.

Strengthening comparative research

We also anticipate opportunities for deepening the NG and CG studies through more comparative research that will strengthen our understanding of the common and distinctive themes that we summarized. In this regard, we envisage at least four opportunities, including (1) among 16 common themes we identified between NG and CG (such as resource dependence, leadership, trust, power, accountability and performance), we call for more research on whether these themes display different functions and characteristics between NG and CG. (2) It will also be fruitful to investigate institutional culture, cooperation history, network management strategies, deliberation traditions and joint effort processes in different cases and contexts that effectuate NG or CG successes. (3) We need to strengthen our knowledge from failed NG or CG cases as compared with their successes in different contexts (Bianchi, Nasi, and Rivenbark Citation2021). And (4) we call for more medium or large-N CG or NG studies that focus on cross-country comparison on institutional design, leadership, collaborative process, accountability, and performance by using some common pool cases, such as the Collaborative Governance Case Database (Douglas et al. Citation2020).

Conclusion

In this article, our goal is to reveal similarities, differences, and entanglements in thematic topics of NG and CG research through a systematic literature review and how we envisage future NG and CG research based on our findings that might move the two research streams towards a general theorization of governance in public administration. Three observations could be drawn when embedding our review in this larger context of public administration.

First, NG and CG are constitutive of governance as evidenced by their similar definitions and their merging research themes. From the governance perspective, NG is the typological system of governance while CG is the conceptual system of governance, collectively contributing to a general understanding of governance theories. Second, the characteristics of NG and CG reflected in the articles we reviewed signal that the research streams of NG and CG are not an alternative method of carrying out policy and providing public service, but a realization of a historically embedded and entrenched idea describing how humans organize and manage their public affairs. The emergence of the concept of governance reflects this historical picture of governing public affairs through collaborative efforts of every fibre of society, being public, private or civil, as reflected by most of the research we reviewed. Third, the current conceptualization of NG and CG is entangled in different interfaces and levels and is full of tensions and paradoxes, which will largely give impetus to prompt future governance research that could be used to reconcile the often contending empirical and normative interests.

Our thematic analysis makes several theoretical contributions to the governance literature with potential managerial implications for public managers engaged in collaborative efforts.

From a theoretical perspective, our systematic review on the thematic topics in NG and CG literature helps to address the concept ambiguity about the two research streams. Clarifying the similarities, differences, and entanglements between the two research streams is useful for scholars to compare the two literature and get a sense of the core tenets of the two literature. Second, our review of the entangled relationship between NG and CG helps to discover an emerging trend of holistic integration on governance literature. Both NG and CG capture the dynamics in governance research and provide us platforms that could be used to reconcile the contending empirical and normative interests. Third, the thematic analysis of similarities, differences and entanglements between NG and CG allows us to generate many relevant research questions, and we thus develop a potential research agenda for NG, CG and governance studies in future. Fourth, our research ideas and methodological approach can be useful for designing other relevant conceptual comparison and literature reviews, such as clarifying the conceptual overlap among co-production, civic engagement, and public participation.

From a managerial perspective, our findings signal the important considerations for public network/collaboration management, public service delivery and public policy making. We believe the similar and distinctive themes of higher frequency () suggest the area of focus for public managers. For example, leadership is critical for the success of collaborative efforts, because a collaborative network needs to be initiated, facilitated, mediated, and managed by both formal and informal leaders. Thus, cultivating a public managers’ competency in leading collaborative efforts is of critical importance in leadership training. Also, the collaborative process should be strengthened by building formalized coordination mechanisms, which can be used by leaders as the management tool to manage participants’ interactions, thus, it is necessary to cultivate a strategic network/collaborative management perspective for public managers. In terms of public policy, our findings on the main themes and entanglements suggest that to achieve public service performance, policies establishing incentives to cooperate within the multiple agencies could help to build trust, share power, and make joint-decision. When making such policies, decision makers need to be aware of potential paradoxes embedded in collaborative efforts and try to find a balance between competing demands and interests.

Our study has its limitations. We focused on the thematic similarities, differences, and entanglements between NG and CG, but we did not explore what factors (e.g. methodological differences, research contexts, etc.) might lead to the similarities, differences, and entanglements. Moreover, there are certainly many other angles besides thematic analysis that could be used to analyse NG and CG literature, such as a bibliometric analysis or an in-depth comparison of the methodologies across NG and CG research, all of which could generate very fruitful outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all anonymous reviewers of this article for their formative feedback and insightful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Huanming Wang

Huanming Wang: His research area includes collaborative governance and public service delivery.

Bing Ran

Bing Ran: His research area focuses on governance and socio-technical systems.

References

- Agranoff, R., and M. McGuire. 2001. “Big Questions in Public Network Management Research.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 11 (3): 295–326.

- Alford, J., and O. Hughes. 2008. “Public Value Pragmatism as the Next Phase of Public Management.” The American Review of Public Administration 38 (2): 130–148.

- Amsler, L.B. 2017. “Collaborative Governance: Integrating Management, Politics, and Law.” Public Administration Review 76 (5): 700–711.

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2008. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571.

- Bianchi, C., G. Nasi, and W.C. Rivenbark. 2021. “Implementing Collaborative Governance: Models, Experiences, and Challenges.” Public Management Review 23 (11): 1581–1589.

- Bryson, J.M., B.C. Crosby, and M.M. Stone. 2006. “The Design and Implementation of Cross-Sector Collaborations: Propositions from the Literature.” Public Administration Review 66: (s1):44–55.

- Castaner, X., and N. Oliveira. 2020. “Collaboration, Coordination, and Cooperation among Organizations: Establishing the Distinctive Meanings of These Terms through A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Management 46 (6): 965–1001.

- Casula, M. 2020. “A Contextual Explanation of Regional Governance in Europe: Insights from Inter-municipal Cooperation.” Public Management Review 22 (12): 1819–1851.

- Cepiku, D., and M. Mastrodascio. 2021. “Leadership Behaviours in Local Government Networks: An Empirical Replication Study.” Public Management Studies 23 (3): 354–375.

- Chen, B. 2010. “Antecedents or Processes? Determinants of Perceived Effectiveness of International Collaborations for Public Service Delivery.” International Public Management Journal 13 (4): 381–407.

- Chen, J. 2021. “Governing Collaborations: The Case of A Pioneering Settlement Services Partnership in Australia.” Public Management Review 23 (9): 1295–1316.

- Cheng, Y. 2019. “Exploring the Role of Nonprofits in Public Service Provision: Moving from Co-production to Co-governance.” Public Administration Review 79 (2): 203–214.

- Choi, T., and P. J. Robertson. 2014. “Caucuses in Collaborative Governance: Modelling the Effects of Structure, Power, and Problem Complexity.” International Public Management Journal 17 (2): 224–254.

- Choi, T., and P. J. Robertson. 2019. “Contributions and Free-riders in Collaborative Governance: A Computational Exploration of Social Motivation and Its Effects.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 29 (3): 394–413.

- Cleveland, H. 1972. The Future Executive: A Guide for Tomorrow’s Managers. New York: Harper and Row.

- Cohen, G. 2018. “Cultural Fragmentation as A Barrier to Interagency Collaboration: A Qualitative Examination of Texas Law Enforcement Officers’ Perceptions.” American Review of Public Administration 48 (8): 886–901.

- Conner, T.W. 2016. “Representation and Collaboration: Exploring the Role of Shared Identity in the Collaborative Process.” Public Administration Review 76 (2): 288–301.

- Cristofoli, D., and J. Markovic. 2016. “How to Make Public Networks Really Work: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis.” Public Administration 94 (1): 89–110.

- Crosby, B.C., and J. M. Bryson. 2005. “A Leadership Framework for Cross-sector Collaboration.” Public Management Review 7 (2): 177–201.

- Doberstein, C. 2016. “Designing Collaborative Governance Decision-making in Search of A Collaborative Advantage.” Public Management Review 18 (6): 819–841.

- Douglas, S., C. Ansell, C.F. Parker, E. Sorensen, T Hart, and J Torfing. 2020. “Understanding Collaboration: Introducing the Collaborative Governance Case Databank.” Policy and Society 39 (4): 495–509.

- Dudau, A., R. Glennon, and B. Verschuere. 2019. “Following the Yellow Brick Road? (Dis)enchantment with Co-design, Co-production and Value Co-creation in Public Services.” Public Management Review 21 (11): 1577–1594.

- Edelenbos, J., N. van Schie, and L. Gerrits. 2010. “Organizing Interfaces between Government Institutions and Interactive Governance.” Policy Sciences 43: 73–94.

- Emerson, K., T. Nabatchi, and S. Balogh. 2012. “An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (1): 1–29.

- Fadda, N., and F. Rotondo. 2020. “What Combinations of Conditions Lead to High Performance of Governance Networks? A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis of 12 Sardinian Tourist Networks.” International Public Management Journal. doi:10.1080/10967494.2020.1755400.

- Frederickson, H. G., K. B. Smith, C. W. Larimer, and M. J. Licari. 2015. The Public Administration Theory Primer. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Westview Press.

- Frederickson, H. G. 2007. “Whatever Happened to Public Administration? Governance, Governance Everywhere.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Management, edited by E. Ferlie, L.E. Lynn Jr, and C Pollitt, 282–304. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hargrave, T. J., and A. H. Van de Ven. 2017. “Integrating Dialectical and Paradox Perspectives on Managing Contradictions in Organizations.” Organization Studies 38 (3–4): 319–339.

- Hartlapp, M., and E.G. Heidbreder. 2018. “Mending the Hole in Multilevel Implementation: Administrative Cooperation Related to Worker Mobility.” Governance 31: 27–43.

- Hendriks, C. M. 2008. “On Inclusion and Network Governance: The Democratic Disconnect of Dutch Energy Transitions.” Public Administration 86 (4): 1009–1031.

- Hermansson, H.M.L. 2016. “Disaster Management Collaboration in Turkey: Assessing Progress and Challenges of Hybrid Network Governance.” Public Administration 94 (2): 333–349.

- Herranz, J, Jr. 2010. “Multilevel Performance Indicators for Multisectoral Networks and Management.” The American Review of Public Administration 40 (4): 445–460.

- Huxham, C., S. Vangen, C. Huxham, and C. Eden. 2000. “The Challenge of Collaborative Governance.” Public Management an International Journal of Research and Theory 2 (3): 337–358.

- Imperial, M.T., E. Johnston, M. Pruett-Jones, K. Leong, and J. Thomsen. 2016. “Sustaining the Useful Life of Network Governance: Life Cycles and Developmental Challenges.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14 (3): 135–144.

- Isett, K.R., I.A. Mergel, K. LeRoux, P.A. Mischen, and R.K. Rethemeyer. 2011. “Networks in Public Administration Scholarship: Understanding Where We are and Where We Need to Go.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21 (1): i157–i173.

- Isett, K.R., and K.G. Provan. 2005. “The Evolution of Dyadic Interorganizational Relationships in A Network of Publicly Funded Nonprofit Agencies.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15 (1): 149–165.

- Jones, C., W.S. Hesterly, and S.P. Borgatti. 1997. “A General Theory of Network Governance: Exchange Conditions and Social Mechanisms.” Academy of Management Review 22 (4): 911–945.

- Kallis, G., M. Kiparsky, and R. Norgaard. 2009. “Collaborative Governance and Adaptive Management: Lessons from California’s CALFED Water Program.” Environmental Science & Policy 12 (6): 631–643.

- Kapucu, N., and V. Garayev. 2012. “Designing, Managing, and Sustaining Functionally Collaborative Emergency Management Networks.” The American Review of Public Administration 43 (3): 312–330.

- Kelman, S., S. Hong, and I. Turbitt. 2013. “Are There Managerial Practices Associated with the Outcomes of an Interagency Service Delivery Collaboration? Evidence from British Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 23: 609–630.

- Klijn, E-H., B. Steijn, and J. Edelenbos. 2010. “The Impact of Network Management on Outcomes in Governance Networks.” Public Administration 88 (4): 1063–1082.

- Klijn, E-H., and J. Koppenjan. 2016. Governance Network in the Public Sector. New York: Routledge.

- Koliba, C.J., R.M. Mills, and A. Zia. 2011. “Accountability in Governance Networks: An Assessment of Public, Private, and Nonprofit Emergency Management Practices following Hurricane Katrina.” Public Administration Review 71 (2): 210–220.

- Krueathep, W., N.M. Riccucci, and C. Suwanmala. 2010. “Why Do Agencies Work Together? the Determinants of Network Formation at the Subnational Level of Government in Thailand.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20: 157–185.

- Lambright, K.T., P.A. Mischen, and C.B. Laramee. 2010. “Building Trust in Public and Nonprofit Networks.” The American Review of Public Administration 40 (1): 64–82.

- Leach, W.D., C.M. Weible, S.R. Vince, S.N. Siddiki, and J.C. Calanni. 2014. “Fostering Learning through Collaboration: Knowledge Acquisition and Belief Change in Marine Aquaculture Partnerships.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 24: 591–622.

- Lee, J., R.K. Rethemeyer, and H.H. Park. 2018. “How Does Policy Funding Context Matter to Networks? Resource Dependence, Advocacy Mobilization, and Network Structures.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 28: 388–405.

- Lewis, J. M. 2011. “The Future of Network Governance Research: Strength in Diversity and Synthesis.” Public Administration 89 (4): 1221–1234.

- Lewis, M. W. 2000. “Exploring Paradox: Toward A More Comprehensive Guide.” Academy of Management Review 25 (4): 760–776.

- Lundin, M. 2007. “Explaining Cooperation: How Resource Interdependence, Goal Congruence, and Trust Affect Joint Actions in Policy Implementation.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 17: 651–672.

- Markovic, J. 2017. “Contingencies and Organizing Principles in Public Networks.” Public Management Review 19 (3): 361–380.

- Milward, H. B., K.G. Provan, A. Fish, K.R. Isett, and K. Huang. 2010. “Governance and Collaboration: An Evolutionary Study of Two Mental Health Networks.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20: i125–i141.

- Molina, O., and M. Rhodes. 2002. “Corporatism: The Past, Present, and Future of A Concept.” Annual Review of Political Science 5: 305–331.

- O’Toole, L. J., Jr., and K.J. Meier. 1999. “Modeling the Impact of Public Management: Implications of Structural Context.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 9 (4): 505–526.

- O’Toole, L. J., Jr., and K.J. Meier. 2004. “Public Management in Intergovernmental Networks: Matching Structural Networks and Managerial Networking.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 14: 469–494.

- Osborne, S.P., G. Nasi, and M. Powell. 2021. “Beyond Co-production: Value Creation and Public Services.” Public Administration. doi:10.1111/padm.12718.

- Ottaway, M. 2001. “Corporatism Goes Global: International Organizations, Nongovernmental Organization Networks, and Transnational Business.” Global Governance 7 (3): 265–292.

- Peng, K., and R. E. Nisbett. 1999. “Culture, Dialectics, and Reasoning about Contradiction.” American Psychologist 54 (9): 741.

- Perry, J. L., and A.M. Thomson. 2004. Civic Service: What Difference Does It Make? New York: Routledge.

- Prentice, C.R., M.T. Imperial, and J.L. Brudney. 2019. “Conceptualizing the Collaborative Toolbox: A Dimensional Approach to Collaboration.” The American Review of Public Administration 49 (7): 792–809.

- Provan, K. G., and R.H. Lemaire. 2012. “Core Concepts and Key Ideas for Understanding Public Sector Organizational Networks: Using Research to Inform Scholarship and Practice.” Public Administration Review 72 (5): 638–648.

- Provan, K.G., and H.B. Milward. 1995. “A Preliminary Theory of Interorganizational Network Effectiveness: A Comparative Study of Four Community Mental Health Systems.” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (1): 1–33.

- Provan, K.G., and K. Huang. 2012. “Resource Tangibility and the Evolution of A Publicly Funded Health and Human Services Network.” Public Administration Review 72 (3): 366–375.

- Provan, K.G., and P. Kenis. 2008. “Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (2): 229–252.

- Purdy, J.M. 2012. “A Framework for Assessing Power in Collaborative Governance Process.” Public Administration Review 72 (3): 409–417.

- Qian, H. 2020. “Book Review: Incentives to Pander: How Politicians Use Corporate Welfare for Political Gain, by N. M. Jensen and E. J. Malesky.” Economic Development Quarterly. doi:10.1177/0891242419896032.

- Ran, B., and H. Qi. 2018. “Contingencies of Power Sharing in Collaborative Governance.” The American Review of Public Administration 48 (8): 836–851.

- Ran, B., and H. Qi. 2019. “The Entangled Twins: Power and Trust in Collaborative Governance.” Administration & Society 51 (4): 607–636.

- Rhodes, R.A. 1996. “The New Governance: Governing without Government.” Political Studies XLIV: 652–667.

- Robertson, P.J., and T. Choi. 2012. “Deliberation, Consensus, and Stakeholders Satisfaction.” Public Management Review 14 (1): 83–103.

- Roiseland, A. 2011. “Understanding Local Governance: Institutional Forms of Collaboration.” Public Administration 89 (3): 879–893.

- Sapat, A., A.M. Esnard, and A. Kolpakov. 2019. “Understanding Collaboration in Disaster Assistance Networks: Organizational Homophily or Resource Dependency?” The American Review of Public Administration 49 (8): 957–972.

- Schad, J., M.W. Lewis, S. Raisch, and W.K. Smith. 2016. “Paradox Research in Management Science: Looking Back to Move Forward.” Academy of Management Annals 10 (1): 5–64.

- Siddiki, S., J. Kim, and W.D. Leach. 2017. “Diversity, Trust, and Social Learning in Collaborative Governance.” Public Administration Review 77 (6): 863–874.

- Siddiki, S., J. L. Carboni, C. Koski, and A. A. Sadiq. 2015. “How Policy Rules Shape the Structure and Performance of Collaborative Governance Arrangements.” Public Administration Review 75 (4): 536–547.

- Silvestre, H.C., R.C. Marques, and R.C. Gomes. 2018. “Joined-up Government of Utilities: A Meta-review on A Public-public Partnership and Inter-municipal Cooperation in the Water and Wastewater Industries.” Public Management Review 20 (4): 607–631.

- Skelcher, C., N. Mathur, and M. Smith. 2005. “The Public Governance of Collaborative Spaces: Discourse, Design and Democracy.” Public Administration 83 (3): 573–596.

- Smith, C.R. 2009. “Institutional Determinants of Collaboration: An Empirical Study of County Open-space Protection.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19 (1): 1–21.

- Smith, W. K., and M. W. Lewis. 2011. “Toward A Theory of Paradox: A Dynamic Equilibrium Model of Organizing.” Academy of Management Review 36 (2): 381–403.

- Sørensen, E., J. Bryson, and B. Crosby. 2021. “How Public Leaders Can Promote Public Value through Co-creation.” Policy & Politics. doi:10.1332/030557321X16119271739728.

- Sørensen, E., and J. Torfing. 2009. “Making Governance Networks Effective and Democratic through Metagovernance.” Public Administration 87 (2): 234–258.

- Sørensen, E., and J. Torfing. 2018. “The Democratizing Impact of Governance Networks: From Pluralization, via Democratic Anchorage, to Interactive Political Leadership.” Public Administration 96: 302–317.

- Span, K.C.L., K.G. Luijkx, J.M.G.A. Schols, and R. Schalk. 2012. “Roles and Performance in Local Public Interorganizational Networks: A Conceptual Analysis.” The American Review of Public Administration 42 (2): 186–201.

- Stoker, G. 1998. “Governance as Theory: Five Propositions.” International Social Science Journal 50 (155): 17–28.

- Sullivan, H., M. Barnes, and E. Matka. 2006. “Collaborative Capacity and Strategies in Area-based Initiatives.” Public Administration 84 (2): 289–310.

- Thomson, A. M., and J.L. Perry. 2006. “Collaboration Processes: Inside The Black Box.” Public Administration Review 66 (s1): 20–32.

- Thomson, A. M., J.L. Perry, and T.K. Miller. 2009. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Collaboration.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19 (1): 23–56.

- Torfing, J., and C. Ansell. 2017. “Strengthening Political Leadership and Policy Innovation through the Expansion of Collaborative Forms of Governance.” Public Management Review 19 (1): 37–54.

- Vangen, S., and C. Huxham. 2012. “The Tangled Web: Unraveling the Principle of Common Goals in Collaborations.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (4): 731–760.

- Vangen, S., J.P. Hayes, and C. Cornforth. 2015. “Governing Cross-sector, Interorganizational Collaborations.” Public Management Review 17 (9): 1237–1260.

- Vangen, S. 2017. “Developing Practice‐Oriented Theory on Collaboration: A Paradox Lens.” Public Administration Review 77 (2): 263–272.

- Waardenburg, M., M. Groenleer, J. de Jong, and B. Keijser. 2020. “Paradoxes of Collaborative Governance: Investigating the Real-life Dynamics of Multi-agency Collaborations Using A Quasi-experimental Action-research Approach.” Public Management Review 22 (3): 386–407.

- Wachhaus, T. A. 2012. “Anarchy as A Model for Network Governance.” Public Administration Review 72 (1): 33–42.