ABSTRACT

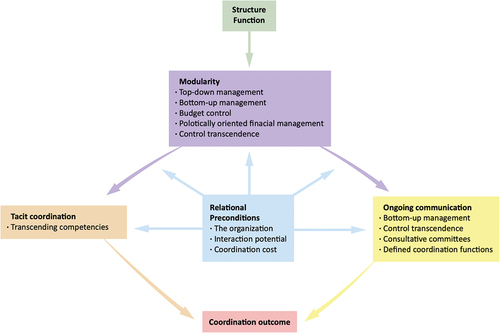

Involving several levels ranging from policy-making to service delivery, the coordination of regional public organizations is a complex matter. This paper explores how relational preconditions affect regional public organizations’ coordination activities and outcomes. A model is developed that links relational preconditions to coordination outcomes. Even though the coordination mechanisms and instruments are used, the coordination outcome might vary based on the individuals and the relationships among individuals. This study suggests that the use of coordination mechanisms and in turn coordination outcome, is affected by the individuals’ personal beliefs and personal relationships as well as trust in the vertical organization.

Introduction

Public administration challenges inspired public managers to apply private organization-based models, leading to multi-level public governance (Bache and Flinders Citation2004). This structure, and the instruments used, caused disaggregation of and separation between policymaking and management (Osborne Citation2006, Citation2010; Lœgreid et al. Citation2014) and led to the devolution of functions and specialization in vertical organizations (Christensen Citation2012). Such structures created autonomous self-centred local levels (Lodge and Gill Citation2011; Christensen and Lægreid Citation2010, Citation2011; Lægreid et al. Citation2015) concerned mainly with achieving their own objectives (Pollitt Citation2003; Gregory Citation2006). As such, government agencies act as self-serving agents (Jensen and Meckling Citation1976) that consider coordination and information processing as undesirable or even as a threat to their integrity (Wilson Citation1989).

The more autonomous the levels are, the less they coordinate with others (Bjurstrøm Citation2021), which makes the vertical coordination of public organizations – the coordination between policy-making, management and the implementation of policies (Baier et al. Citation1986)–increasingly complex and challenging. Coordination is ‘ … the instruments and mechanisms that aim to enhance the voluntary or forced alignment of tasks and efforts of organizations within the public sector’ (Bouckaert et al. Citation2010, 16).

A wide stream of research examines coordination and collaboration in public sector (c.f. Mayer and Kenter Citation2015; Wilkins et al. Citation2016; Hudson et al. Citation1999; Costumato Citation2021; Thomson and Perry Citation2006; Aunger et al. Citation2021; Willem and Buelens Citation2007; Peters Citation2018; Lægreid et al. Citation2015; Mu et al. Citation2019). In its broadest form, collaboration and cooperation are subsets of coordination (Bouckaert, Peters, and Verhoest Citation2010; Castañer and Oliveira Citation2020), though outlining and analysing their differences is beyond the scope of this study. This study focuses on coordination in its broadest form.

Coordination success equates to a higher degree of integration (Puranam et al. Citation2012), which is necessary to sustain an organization (Choi and Chandler Citation2015). However, public organizations are not designed for ultimate coordination (Chandler Citation1962; Perrow Citation1967; Hickson et al. Citation1969; Thompson Citation1967), nor can one assume that activities must be coordinated in organizations regardless of their design (Faraj and Xiao Citation2006; Heath and Staudenmayer Citation2000; Ballard and Seibold Citation2003; Gulati et al. Citation2012). Given that the goal of public sector programmes and policies is to create public value (Moore Citation1995; Try and Radnor Citation2007), vertical coordination is needed to bridge public programs and policies with their implementation.

The factors that inhibit or facilitate coordination is well discussed in coordination research (Williamson Citation1975; Rogers and Whetten Citation1982, Alexander Citation1995; Palmatier et al. Citation2007; Moshtari and Gonçalves Citation2011). Such studies focus on the connection between the preconditions and the choice of coordination activities, often referred to as coordination mechanisms. The definition of Bouckaert et al. (Citation2010) implies that instruments and mechanisms should be used to align the tasks and efforts of organizations to achieve coordination; that is, the focus is on coordination as an outcome rather than the instruments and mechanisms per se. If coordination activities equal coordination outcomes, researcher extensively explored how coordination preconditions influence instruments and mechanisms. Research on the association between the preconditions of coordination and coordination outcomes is scarce.

Besides structural and functional aspects, Palmatier et al. (Citation2007) point out that personal relations are also an important precondition. Thus, personal relations as a precondition may influence the outcome of coordination activities and the coordination outcome. As this aspect seems overlooked in previous research, we aim to fill this gap by answering the following research question: How do relational preconditions affect regional public organizations’ coordination activities and outcomes? To address this question, we examine the coordination between two administrative levels within Swedish regional public transport organizations.

This study makes three contributions to the literature. First, we develop a model that connects relational preconditions to coordination-mechanisms and coordination outcomes in regional public organizations. Second, we find that informal relations between individuals often generate the coordination outcome, rather than structural and functional aspects. Third, the findings open the way for further reflections on the risks of negative side effects in regional public organizations. Such risks relate to (1) situations in which agencies may, despite their efforts in structural and functional aspects, be perceived as engaging in ‘policy dressing’ and (2) spending resources on creating structures, mechanisms, and instruments, while neglecting the influence of individuals’ intentions, relationships, interpretations and self-centred views.

Theoretical framework

New public management (NPM) created specialization and decentralization, leading to more detailed and refined public services. This paradigm also caused fragmentation among agencies. The relationships between agencies seems to be based on self-interest, where each party will deliver only what is specified (Osborne Citation2010; Boyne Citation2002; Ferlie et al. Citation1996; Hood Citation2005). Previous studies argue that emphasizing the performance of single agencies rather than on broader goals and values creates strong incentives for single organizations to pursue activities that focus on their own organizations (Bouckaert et al. Citation2010). In addition to structural difficulties as far-reaching specialization and fragmentation, coordination difficulties also lie in the personal agendas of individuals who act based on bounded rationality and opportunism (Ouchi Citation1980; Kalra et al. Citation2020) in the best interests of their subagency (Bourgault Citation2007). This field of research does not yet explain how this leads to coordination difficulties in regional public organizations and the connection between informal relations among individuals and coordination outcomes.

Coordination

The definition of ‘coordination’ is often assumed. An extensive literature review confirms the existence of various definitions (Okhuysen and Bechky Citation2009; Castañer and Oliveira Citation2020). Therefore, the absence of a unanimous definition is not due to ignorance, but to the presence of too many different definitions (Alexander Citation1995).

Early coordination research (Fayol Citation1949; Taylor Citation1916; Chandler Citation1962; Hickson et al. Citation1969; Thompson Citation1967; Stover Citation1970; Woodward Citation1970) focused on ultimate organizing to coordinate efforts. Contemporary research on coordination assumes that activities must be coordinated in organizations regardless of the design, and therefore focuses on coordinating activities rather than organizing (Faraj and Xiao Citation2006; Heath and Staudenmeyer Citation2000; Ballard and Seibold Citation2003; Malone and Crowston Citation1990). This is based on the belief that the survival of an organization and its members requires resource mobilization and coordinating efforts (March and Simon Citation1958). In a review on coordination, Okhuysen and Bechky (Citation2009) described three commonalities in the definitions: people work collectively, the work is interdependent, and an outcome is achieved. For instance, Koop and Lodge (Citation2014) defined coordination as the attempted adjustment of actions among interdependent actors to achieve specified goals. Malone and Crowston (Citation1990) focused coordination on the act of managing interdependencies between activities performed to achieve a goal. Further, the literature suggested two types of coordination, formal and informal, based on contractual and relational coordination mechanisms, respectively (Cao and Lumineau Citation2015; Roehrich et al. Citation2020). We acknowledge both informal and formal coordination mechanisms, though we do not distinguish between them as it is not necessary to answer our research question.

The vertical fragmentation of the public sector, with levels of specific, nonoverlapping roles and functions, as well as often inconsistent goals, does not necessarily require the anticipation of other units’ actions, nor does it justify or encourage parties to adapt their actions to others. Therefore, fragmentation can affect the organizations’ perceptions of required integration and thus the perceived need for coordination. Paradoxically, a central assumption in organization theory is that specialization increases the need for coordination (Thompson Citation1967; Mintzberg Citation1979). Based on Metcalfe (Citation1994), Peters (Citation1998), Alexander (Citation1995) and Thompson (Citation1967), Bouckaert et al. (Citation2010) interestingly found the aspects of voluntariness and enforcement. Bjurstrøm (Citation2021) discussed why various levels of public organizations might regard coordination as undesirable and the connection between the desire for coordination and the agencies’ degree of autonomy: the more autonomous, the less desire to coordinate with others. The autonomy itself rather than the coordination mechanisms challenges the coordination between agencies.

Coordination mechanisms

Having discussed coordination, we now turn to the mechanism of coordination. Okhuysen and Bechky (Citation2009, 472) suggested that coordination mechanisms are ‘the organizational arrangements that allow individuals to realize a collective performance’. Drawing on empirical international comparative research, Bouckaert et al. (Citation2010) developed a typology of coordination instruments useful for the coordination of public sector organizations. Bouckaert et al. (Citation2010) grouped coordination instruments into management and structural instruments, and connected the coordination mechanisms with hierarchies, markets or networks to emphasize the mechanism underpinning the coordination efforts.

Okhuysen and Bechky (Citation2009) summarized the literature on coordination mechanisms by suggesting five coordination mechanisms within an organization: plans and rules, objects and representations, roles, routines, and proximity.

Given the research question, we focus on individuals’ coordination activities rather than coordination instruments as phenomena. Therefore, our interest is in categories with different mechanisms. Srikanth and Puranam (Citation2014) summarized coordination mechanisms identified in previous studies into three categories: modularity, ongoing communication and tacit coordination. This categorization offers a grouping in which mechanisms, despite their practical differences, are organized in a way that explains their significance in structural, interpersonal and intangible aspects. Similar groupings were useful in other coordination studies. For instance, in their literature review, Gulati et al. (Citation2012) used structural, institutional and relational schools of thought to discuss how to overcome coordination failures. Therefore, we adopted Srikanth and Puranam’s (Citation2014) categorization of coordination mechanisms.

Modularity involves designing public organization in terms of units of tasks and responsibilities. Interfaces create a system interaction among the units (Srikanth and Puranam Citation2014) segmented into a tacit practice for coordination between different units (Simon Citation1962). These interfaces (plans, rules and schedules specifying tasks and responsibilities) are indispensable to organizing (March and Simon Citation1958; Scott and Davis Citation2007; Galbraith Citation1977; Tushman and Nadler Citation1978), as interdependency is typical of all units in almost all organizations. The focus of the interfaces may vary depending on the focus of the organization. For instance, Johnson et al. (Citation2021) argued that when focusing on central control, modularity involves interfaces for information. When integrated solutions are central, modularity handles dependencies by focusing on innovative processes. As the focus on modularity and organizational design manages dependencies between units through interfaces, this reduces the need for ongoing communication. Thus, whereas ongoing communication constantly updates common ground, modularity involves working with a minimal, constant level of common ground embedded in the interface.

Ongoing communication, including ordinary interactions between people in interdependent units, is an important mechanism for updating and maintaining common ground (March and Simon Citation1958; Thompson Citation1967; Okhuysen and Bechky Citation2009; Srikanth and Puranam Citation2014). Physical closeness and co-locations positively influence the amount of interaction and communication (Allen Citation1977; Okhuysen and Bechky Citation2009), while virtual communication technology is limited in terms of updating common ground. Co-presence helps achieve coordination by creating visibility. Organization members can then see what others are doing. This stimulates them to update the common ground (Kraut et al. Citation2002; Olson and Olson Citation2000). When co-location is not possible, people attempt to make the work visible by communicating the status of the work through other means (Okhuysen and Bechky Citation2009). Further, ongoing communication and social closeness create awareness between units, thereby coordinating through the effect of awareness on the development of trust among individuals.

Tacit coordination mechanisms leverage tacit, explicitly shared knowledge, and include coordination without the need for ongoing communication (Camerer Citation2003; Srikanth and Puranam Citation2011). Such mechanisms work in two ways. First, they achieve coordination by using pre-existing common ground that may not be specific to the task at hand, such as rotating tasks among employees (Ghoshal et al. Citation1994; Nohria and Ghoshal Citation1997). Second, they build common ground as people observe each other when working side-by-side (Clark Citation1996; Cramton Citation2001; Gutwin et al. Citation2004). The latter relies on building common ground by observing the work context, actions and outcomes, making physical co-location a primary means (Clark Citation1996; Cramton Citation2001; Gutwin et al. Citation2004). The former leverages long-term ongoing personal communication and common ground as it creates awareness among members (Kraut et al. Citation2002).

Coordination preconditions

Extensive research examines the preconditions for relationship performance (Williamson Citation1975; Heide and John Citation1990; Bucklin and Sengupta Citation1993; Parkhe Citation1993; Morgan and Hunt Citation1994; Gundlach and Cadotte Citation1994; Lusch and Brown Citation1996; Siguaw et al. Citation1998; Wathne and Heide Citation2000; Cannon et al. Citation2000; Hibbard et al. Citation2001). In a comparative study, Palmatier et al. (Citation2007) used longitudinal data to provide several insights into the key drivers of relationship performance. They concluded that commitment-, trust-, and relationship-specific investments are parallel and equally important as key drivers (Palmatier et al. Citation2007), and placed individuals and relationships at the heart of the interorganizational performance. Similarly, Caldwell et al. (Citation2017) argued that organizational experience underpins effective coordination and performance. In the public context, individual aspects such as members’ ideologies, opportunistic behaviour, the lack of interest in coordination between actors due to autonomy, reluctance to share information, partisan politics and relationships between the actors arise as facilitators and inhibitors of effective coordination (Bouckaert et al. Citation2010). While these preconditions offer potential for extensive analysis, we require a broader categorization. Alexander (Citation1995) offered a less detailed, yet broader categorization that captures all these preconditions in an organization or its environment. These categories relate to personal agendas and individual relations. The three categories are: (1) the organization, (2) coordination costs and (3) interaction potential (Alexander Citation1995). Alexander (Citation1995, 21) argued that these preconditions control ‘ … organizations’ decisions so as to concert their actions and achieve mutually beneficial outcomes’.

The organization (i.e. the members of organizations) makes presumptions about policies, and these belief patterns shape the members’ approach to coordination (Chan and Clegg Citation2002; Campbell Citation2001). Alexander (Citation1995) argued that the organizational structure and its characteristics influence the perception of coordination. For instance, the more centralized an organization is, the more likely it is to appreciate and engage in coordinated efforts. Other indicators that an organization will be open to coordination are informal contacts within the organization and across its subunits; trust, a result of shared values; and a history of interaction or common background, with free exchange of information and resources (Stephenson and Schnitzer Citation2006; Whetten Citation1981).

Coordination costs and benefits are important drivers for accepting coordination, such as when overhead costs change based on changed modularity or communication paths versus the benefits of such changes in modularity. Coordination costs can also concern self-interest; that is, perceived threats to personal intentions (Whetten Citation1981). In public organizations, individuals may pursue specific policy and political goals that benefit their personal interests and may not seek cooperation for fear of reducing their chances of reaching those goals (Bouckaert et al. Citation2010). Similarly, middle-level officials, managers or administrators who view such developments as a threat to their control over valuable information (Alexander Citation1995) or attempts to increase governance coherence may undermine or sabotage administrative routines, coordination efforts and even legal mandates for implementation.

Interaction potential includes the attitudes and relations between different organizations or divisions (Thomas et al. Citation2007; Alexander Citation1995). Previous experience, real or perceived task interdependency, resource dependency (Whetten Citation1981; Alexander Citation1995) and previous experiences of similar collaborations and relationships in similar contexts may influence such attitudes and relations. Organizations with positive experiences have strong prospects for coordination. Despite the task interdependence designed to accomplish a task, perceived interdependence can vary. For instance, there is high vertical interdependence among politicians, administrative units and autonomous organizations to create user-oriented policies and formulate and implement them in daily work (Laegreid et al. Citation2014; Whetten Citation1981). Despite such interdependencies, organizations may focus on their own missions and perceived independence (Alexander Citation1995).

Summary

The theoretical framework provides a basis for coordination in public organizations and the preconditions influencing the coordination. We discuss NPM reforms and their influence on the structure and function of public organizations to clarify coordination challenges. Deepening the discussion on coordination and coordination mechanisms, this study elaborates on the concept of coordination and its preconditions. We also examine the challenges of public organizations’ coordination, emphasizing the influence of individuals and their relationships rather than focusing solely on structures and functions.

Although the three categories of coordination mechanisms described above are very well established in the literature, we examine how individuals and their relationships influence the use of these coordination mechanisms, with particular attention to how it affects the coordination outcome.

Methodology

Swedish public transport

In Sweden’s 21 regions, regional public transport is governed through Regional Public Transport Authorities (RPTAs) and organized via operational departments within the regional body or publicly owned corporations. In all except the two largest regions, the RPTAs are small departments consisting of one to three civil servants.

While Swedish public transport regulation is comprehensive, it remains open to regional interpretation or adaption. The autonomous organizations that deliver the public service are self-directing, but they are still linked to administrative regional authorities through politically mandated structures. Regional political bodies make funding decisions, resulting in several levels of resource dependency.

In this context, three levels of analysis are relevant to this study. The political level (Level 1) refers to politicians representing the municipalities directly or indirectly through regional/county committees. This level sets the overall policies of regional public transport and budget. The level of departments (Level 2) is the core of the administration, situated directly below the political level; this is where the RPTAs are placed. Quasi-autonomous organizations are present at Level 3, which include agencies performing tasks for public organizations. These agencies are organized either as operational departments within the regional body or as publicly owned companies. In the context of this study, this level is an administrative unit and does not deliver the service per se; these quasi-autonomous organizations are assigned to organize the regional public transport services. They fulfil their commitment by steering and monitoring the procured service performance of the public transport operators. Thus, there is also a fourth level, at which the actual public transport services are realized and performed. We focus on the coordination instruments between Levels 2 & 3 and the complexity behind the use of such instruments.

Sampling

We used purposive sampling to select the study participants (Saunders et al. Citation2009). We used a pre-study with four semi-structured phone interviews to test the appropriateness of the research context and the informants. The pre-study showed three types of regional organizational solutions: (1) the regional federation chosen for the RPTA, (2) financial management and (3) the form of the operational organization for public transport; that is, either through departments within the regional body or publicly owned companies. This information guided our sampling. We chose six additional cases to broadly represent the different types of RPTAs.

The interviewees were selected based on their role within the RPTAs. The interviewee had to be active in the RPTA’s daily processes (Level 2), which requires communication with politicians in Level 1 and with quasi-autonomous organizations in Level 3. As the mapping prior to the study revealed, only between one and three individuals in each region are active within Level 2, which offered a clear delimitation of the sample. These participants were identified using each region’s website and the authors were then guided through the organizations to find the final participants. The final sample size for this study was 10 research participants from 10 regions. summarizes the basic information of the study’s participants.

Table 1. An overview of the cases.

Data collection

Before the interviews, we studied all the participants’ regional policy documents that RPTAs must create by law. The semi-structured interviews were conducted by phone, audio-recorded and transcribed, resulting in approximately 30 hours of recorded interviews and 200,000 words. The researcher asked the participants to provide their explicit consent to ensure that they agreed to participate in the research interview voluntarily. The interview guide focused on the reasons for the chosen structure of the regional public transport, long-term goals, the role of public transport in its region, how the RPTAs coordinate with the organizer of the regional public transport (Level 3), what tools they use and how they follow up on the public transport performance (Appendix 1 provides further information about the cases).

Data analysis

Given the research question, we needed to understand what drives the relational preconditions, coordination instruments and activities. We therefore adopted two different coding processes: one exploring the insights of coordination mechanisms and the other focusing on the relational preconditions. We analysed the extensive dataset using the two parallel processes in Gioia et al. (Citation2013) method shown in . Step 1, in the first-order of analysis, we began the coding by recognizing initial concepts and grouping them into codes to create a manageable set of information in the transcripts. We ensured that the codes were closely aligned with the participants’ responses using codes closely connected to terms used by the participants. Step 2, we composed themes in the second-order analysis after identifying these codes. Thus, codes explaining the same theme were put together using more descriptive theme labels. This coding resulted in (1) eight coordination instruments () four themes for coordination preconditions (). Step 3, the second-order themes were refined and distilled into aggregate dimensions. Step 4, for both analyses (), we reviewed the aggregate dimensions against the existing literature and applied existing concepts to explain the second-order themes. As such, the aggregate dimensions labels in (modularity, ongoing communication and tacit coordination) and aggregate dimensions labels in (the organization, interaction potential and coordination cost) originate from existing literature (Srikanth and Puranam Citation2014; Alexander Citation1995). We present the coordination instruments and the preconditions of coordination in the findings section. The two parallel analyses confirmed the existing literature on coordination mechanisms and relational preconditions. However, the second-order themes and the understanding of them based on the first-order terms in each analysis made it possible to bridge the two coding processes. It is in the interface between these two that the main contributions rest, which we present in .

Data quality

We relied on Lincon and Guba’s (Citation1985) concept of trustworthiness. To ensure the trustworthiness of this study, we followed the guidelines and methodological in Gioia et al. (Citation2013) and used member checks on different occasions. All 10 interviewees had the opportunity to approve the narrative case descriptions. For the four cases in the pre-study, the result of the pre-study was presented and discussed at an in-person meeting; all participants approved. In addition, the findings of the study were presented at a workshop attended by representatives of all 21 Swedish RPTAs (including the 10 cases studied) and other national actors within Swedish public transport. Informants agreed with the findings and the logic of the study and provided feedback that confirmed the analysis. We also include context descriptions, quotes and coding schemas.

Findings

Coordination instruments and mechanisms

In the first-level coding, which focuses on coordination activities, we identified eight coordination instruments (see ). On an aggregated level, three generic coordination mechanisms explain these instruments: modularity, ongoing communication and tacit coordination.

Theme 1: top-down management

In planning and processes, interviewees spoke about hierarchical objectives and targets, as well as performance monitoring. Some cases revealed that RPTAs have policy documents with compelling goals that lower levels must report on. The targets do not belong to the quasi-autonomous department that should meet the goals; rather, they belong to the upper level – the RPTAs. The following excerpts from two interviewees indicate the methods of top-down management, where the expected performance, performance targets, and evaluation of the performance are in the hands of upper management.

The company presents targets specifically designated by RPTAs in all meetings with the political committee, which is five times a year. The company is only present for a short time during the meeting, briefly presenting its operations and how it is doing financially in relation to the ordered traffic by the municipalities. (Case 10)

We have a follow-up model that controls the follow-up in detail. The targets that the company must report on have been created by the RPTA. (Case 2)

Theme 2: bottom-up management

The participants provided example policies and targets influenced strongly by the lower level organizations that are to realize the goals. Even in higher-level policy decisions, the lower level was included in the discussion and seen as a righteous party with valuable opinions. Further, the interviewees explained that in these cases monitoring of objectives is a joint process in which representatives from different levels work together in a team. This trust-based instrument relies on negotiation with and inclusion of the lower level. Bottom-up management coordination instruments clarify the lower-level perspective, and can therefore be explained with both modularity and ongoing communication. Cases 10 and 3 offer examples of how RPTAs use bottom-up management coordination instruments.

When we created the regional policy document, the company thought we should reformulate one part of the document because it was too detailed. We listened to them and changed it. We have a follow-up system that is done once a year and we do this together with the company. (Case 3)

The development of the regional policy document was really a collaboration among the company, me, and someone from the infrastructure department. (Case 10)

Theme 3: budget control

When discussing roles and responsibilities, participants mentioned financial management and that the tasks and responsibilities can be coordinated and strictly controlled by far-reaching budget specifications. They also explained that in such cases the budget is directly linked to the operation in detail, a direct principal-and-agent situation. The focus is on maintaining the budget and financial framework. Two interviewees explained how this tool is used:

You really have no power to control what the budget should be spent on because the municipalities themselves decide; they pay for the traffic they want. (Case 8)

The company should only operate the traffic that has been ordered. The company is not allowed to make changes such as the schedules; they have no such authority. (Case 10)

Theme 4: politically oriented financial management

Other participants described financial management as being more loosely connected to the overall budget, reflecting the mission and political intention. In these cases, the affected organization cannot make financial decisions. The budget is often based on taxes, and the organization competes with other public services such as health care or urban planning. The political intentions are seen in the size of the budget. However, this coordination instrument often offers greater freedom and allows organizations to act freely within the budget framework and other declarations of intent.

The regional council supported the national target of doubling the regional public transport and, so far, the budget has given room for it. (Case 3)

Within the framework of the budget, the operational department has the freedom to execute, take responsibility for, and follow up on operations itself. (Case 1)

The council says, ’You get 738 million, do as much public transport as possible’. (Case 6)

Theme 5: control transcendence

Most regional public organizations consist of several sub-units, each with its own hierarchy. When discussing ways to bridge the coordination challenges created by the connections of several sub-units, the participants mentioned key individuals with a broad span of control. For instance, having the same manager for different departments or having the same chairperson in the different levels through the decision-making process changes the transcendence of control and can ease coordination. In these cases, authority and responsibility are specified, but the transcendent control also creates a formal schema for ongoing communication. The interview excerpts below show two examples.

The head of the operational department and the traffic director are the same person and the head of the operational department has a far-reaching delegation. (Case 5)

The chair of the Traffic Committee is also chair of the County Council. Before any political meetings, we have a small committee that meets up, which consists of the Traffic Committee’s chair, vice chair, and administration manager, so we have not experienced any problems in the decision making. We reason with the chair of the small committee if we have any thoughts on how different issues should be handled, then he handles this further. (Case 1)

Theme 6: consultative committees

When speaking further about coordination challenges arising from the connections of several sub-units, participants mentioned groups or committees established to ease information distribution among the different organizations and create interorganizational information exchange. The interviewees explained that these committees have no decision-making power; they just bridge boundaries and create a holistic view to avoid creating new formal units whose only aim is to connect distant departments or organizations. As such, the exchanged information can be either one-way or two-way depending on the question and situation. Two interviewees explained their use of this coordination instrument:

The Traffic Committee has no formal decision-making power, but they prepare cases and decide what to include in the board discussion … It is a way for different departments to come together before committee meetings. (Case 1)

There is a need for an employee group from both the County Council and the company, but we do not need to be placed within the same organization; we can work together anyway. Therefore, we have the department for RPTA support within the company. (Case 6)

Theme 7: defined coordination functions

While this theme is reminiscent of consultative committees, another type of grouping is used to bridge communication gaps. However, the focus of these functions is to monitor and control the organizations that are to be coordinated. Such entities are used for direct control and getting access to information that might not otherwise have reached them. As such, it seems to be a tool for ongoing communication, albeit only in one direction. One interviewee explained this function emphasizing direct control:

I also act as counsel, even when the company has the power to make its own decisions, because, yes, I know more than anyone else about the company and laws and regulations. I am the RPTA, I am the owner’s representative, I exercise some form of owner supervision while I have ongoing dialogue with the company. (Case 10)

For monitoring, these functions need not be formal units within the organizational hierarchy. As one interviewee explained, these functions can exist ‘on the side’ with the sole purpose of gaining insight:

For municipalities to control the county council that is responsible for public transport, there is something called the Transport Board. It has no formal position in the county council or in its hierarchy, but is only for the purpose of insight and control. The Transport Board is like an ugly duckling. (Case 9)

Theme 8: transcending competencies

Some participants mentioned ways of bringing different entities together to create holistic understandings or even declarations of intention, such as through co-location and organizational co-existence. These activities focus on bridging organizations, entities or people to create visibility and familiarity. In some cases, it is about the organizational placement of the department in hierarchy and that such positioning will lead to common ground. In other cases, it is about familiarity, where individuals know each other either through previous or current co-existence.

The Department of Regional Growth refers to the regional growth, of which public transport is a part. It is a logical positioning to have the RPTA placed within that department. (Case 4)

I used to work at the company before I got this position. (Case 3)

I think it would do a lot if we were just sitting in the same building so we could see each other. (Case 8)

Coordination precondition

Through the first-level coding, with its focus on the preconditions of coordination activities, we identified four themes: the interpretation of the national regulation, the municipalities’ trust in the regional council or association, the trust in the quasi-autonomous entities organizing the service, and the intention with the public service. On an aggregate level, three dimensions explain these themes: the organization, interaction potential, and coordination costs. We describe each theme below and its relationship with the aggregate-level dimensions.

Theme 1: municipalities’ trust in the regional council or association

When discussing the regulatory requirements and their interpretation, one interviewee explained that the trust of the municipalities governed the placement of RPTA because the municipalities must agree on where to place the RPTA within the organization. In Case 1, the municipalities had strong confidence in the county council:

In our county, the municipalities have a well-founded confidence in the county council and our expertise in traffic matters. (Case 1)

In Case 1, the county council is the RPTA and the county council politicians control public transport services in terms of the relevant taxes. The matter of where to situate the RPTA then become simple. In Case 2, however, the municipalities were afraid of losing control of public transport. They wanted the RPTA to be placed somewhere other than within the county council. Case 2 chose a multi-purpose municipal association owned by the municipalities of the region. The budget of the RPTA was set by the political representative of each municipality. The incongruity in Case 7 was even greater; the fundamental distrust in existing associations resulted in a single-purpose municipal association for public transport services.

The municipalities could not agree on whether public transport issues should be handled in an existing municipal association or county council, so a compromise was made. (Case 7)

In a single-purpose municipal association, the politicians have full control of public transport services without having to compromise with other public services. The attitudes and relationships between Levels 1 and 2, as well as the trust between the levels based on previous experiences (best explained as the precondition of the organizations and interaction potential), influenced the structure of the RPTAs. Thus, the municipalities’ trust in the regional council or association created a diverse structure that required a different type of coordination.

Theme 2: interpretation of regulations

Interpretations of regulations also seem to guide each region in its chosen structure. All 10 cases seem to agree on the aim of separating strategic and operational platforms. However, the cases seem to have different interpretations of doing so requires. Some respondents argued that such separation is only achieved by separating the RPTA and the operational level by having them in different organizations. Others argued that there is no need to create new departments and structures to fulfil the law. Our cases indicate that the interpretation of regulations affect the structure of regional public transport. One could argue that the various interpretations, reflecting members’ ideologies about policy, influenced their need for coordination and the type of coordination instruments.

Theme 3: regional council or association intentions with the service

We find that the organization’s intention with the service influences which coordination instruments it uses. As such, the regional organizations not only interpret regulations in various ways, but also have different intentions with the service. The intentions seem to be founded either on shared values among the members, explained by the organization precondition or opportunistic self-interest among significant factors that influence the coordination activities. Some RPTAs argued for the benefits of regional public transport services and have a high level of ambition. They use the policies and regulations to create the best possible organization fit for the purpose. In Case 1, the RPTA’s interest is in demonstrating that it cares about public transport services. In Case 3, the importance of public transport is even clearer: it created a large ‘middle management’ organization (11 people), while most RPTAs have no middle management.

Some regions consider public transport services as a requirement for public transport regulations. These organizations aim to fulfil the minimum regulatory requirements and spending taxpayers’ money on more important services. Two interviewees explained:

Public transport is not seen as a service that develops the region; rather it is seen more as a cost to keep as low as possible. (Case 9)

We don’t want to hire a lot of people just to have a civil service organization for public transport. (Case 5)

Theme 4: the regional councils’ or associations’ trust in the quasi-autonomous entity

The level of trust that the regional councils or associations have in the quasi-autonomous entity seems to be a precondition for coordination. Low trust seems to lead to a higher need for control and monitoring, while high trust results in a low degree of monitoring and unanimous goals. Attitudes and relationships between levels seem to influence coordination activities, as do shared values and trust based on previous experiences. Some regional councils/associations dealt with low trust in the quasi-autonomous entity by creating numerous regulatory documents that specify the obligations of each party. Other cases portray a high level of trust in the quasi-autonomous entity, where the RPTAs and the quasi-autonomous organizations work together as a team to reach common goals. In high-level trust situations, some cases have even outsourced all responsibilities for public transport services to the quasi-autonomous organization.

Discussion

We explored how relational preconditions affect regional public organizations’ coordination activities and outcomes. Using Gioia et al. (Citation2013) method, we identified themes that explained the preconditions of coordination and the coordination mechanism in regional public organizations. We next focus on establishing the actual bridge between them. The findings, summarized in , highlight the relevance of relational coordination preconditions for the coordination mechanisms, and in turn, the coordination outcome. We used the coordination instruments and mechanism themes, as well as coordination precondition themes () identified in the coding process to discuss how individuals and their relationships influence the coordination outcome. The relevance of such individual- and relationship-specific preconditions on coordination outcomes are in line with findings by Palmatier et al. (Citation2007), Moshtari and Goncalves (Citation2011), and Bouckaert et al. (CitationCitation2010).

shows that relational preconditions; that is, the individuals’ personal beliefs and personal relationships in the vertical organization affect coordination outcomes. As such, the use of similar coordination instruments can have different coordination outcomes depending on the relational preconditions. Below, we elaborate our findings in terms of the relational precondition and its influence on the coordination mechanism (Srikanth and Puranam Citation2014), and in turn, the coordination outcome.

Relational preconditions’ influence on modularity

Modularity in the organization’s design is a main category of approaches to coordinating in private settings (Srikanth and Puranam Citation2014). In public settings, modularity becomes even more complex because a different paradigm of public management guides the organizations towards a general structure of modularity, which limits the potential to tailor the organization and because the main intention in public settings is not always clear (Mahoney et al. Citation2009).

NPM favours decentralization in the public sector, which influences the overall modularity. This led to an increase in the pillarization and siloization of the public sector, resulting in high fragmentation (Osborne Citation2010; Boyne Citation2002; Ferlie et al. Citation1996; Hood Citation2005; Bouckaert et al. Citation2010). High decentralization and often inconsistent public goals foster self-centred agencies, leading to a great need for coordination but a disinclination to do so (Bouckaert et al. Citation2010). Previous research sought to solve these modularity issues through structural changes. The challenge is that trust, shared values and history of interaction (Stephenson and Schnitzer Citation2006; Whetten Citation1981) remain influential. As such, the matter of coordination is not only due to structural aspects regarding the choice and use of coordination instruments, but also due to individual aspects of the agents active in those processes. The organizations included in this study consist of several specialized agencies and coordinates via formal channels. The themes distilled through the coding process revealed that individuals’ beliefs, intentions, trust and relations influence the use of modularity instruments.

NPM creates autonomous organizations that unwillingly coordinate between levels. The findings suggest that it can be affected by individuals’ trust, shared values, and history of interaction (Stephenson and Schnitzer Citation2006; Whetten Citation1981). As such, the organization as a precondition is linked to the actual use of modularity. For example, organizations interpret the regulation requiring the existence of the RPTAs and the separation of strategic and operational platforms differently. While some of the interviewees believe that a clear separation between policy and operational departments in required, others interpret the requirements of the law as a formality. The actual use of the modularity instruments seems to be based on the interpretation of the RPTAs. Accordingly, members’ presumptions about policies are an influencing factor (Chan and Clegg Citation2002; Campbell Citation2001).

The findings suggest that coordination costs (Whetten and Leung Citation1979; Alexander Citation1995; Bouckaert Citation2010) regarding monetary benefits for the RPTA, retention of power and overall convenience, influence both the choice and the use of coordination instruments. Such preconditions to coordination instruments act as a link to modularity in terms of individual and opportunistic behaviour (Verhoest and Bouckaert Citation2005; Christensen and Lægreid Citation2010) among actors in the vertical bodies and likely insufficient interfaces. For example, the intention behind the public service affects the design of the organization into different units, the use of and relevance of these units, and the coordination outcome. While formal modularity indicates central control or integrated solutions (Johnson et al. Citation2021), the use of such coordination instrument is affected by individual cost and benefits. This associates coordination costs with modularity.

Relational preconditions’ influence on ongoing communication

Ongoing communication dynamically updates and maintains the common ground needed to fulfil the intentions of modularity (Clark Citation1996; Okhuysen and Bechky Citation2009; Srikanth and Puranam Citation2014). It links modularity to the coordination outcome through various coordination instruments. Interactions between organizational members are important in ongoing communication (March and Simon Citation1958; Thompson Citation1967; Okhuysen and Bechky Citation2009; Srikanth and Puranam Citation2014). We identified the coordination instruments that reinforce communication and influence the coordination outcome depending on the preconditions. For instance, consultative committees or defined coordination functions can be used either for insight and control purposes or to actually create interfaces that enable communication. Our findings indicate that trust within the vertical organization; that is, the trust of regional politicians and that of the RPTAs, influences how the instruments of ongoing communication are used. The existence of the ongoing communication instruments does not offer much information per se, nor does it offer an understanding of how the instruments actually are being used. Instead, an understanding of the different attitudes and relations between the different agencies – the interaction potential – is needed to appreciate the relevance of the coordination instruments on the coordination outcome. This connects interaction potential with ongoing communication.

Additionally, coordination instruments connected to ongoing communication can be used to create interactions or reassure regional politicians. It can also create an impression of a well-coordinated organization without actually coordinating tasks. When the intention is to create a public service value, the focus is on the coordination outcome and the communication instruments then accomplish much more than bare-minimum compliance with national regulations. For instance, previous research argued that when members meet, they update their common ground (Allen Citation1977; Olson and Olson Citation2000; Kraut et al. Citation2002; Okhuysen and Bechky Citation2009). However, our findings indicate that physical co-location can have different uses and outcomes dependent on its intention. When monitoring and control are the central reason behind the physical and/or organizational co-location, then it does not update the common ground. Rather, the co-location as ongoing communication seems to be used purely for insight and control. In cases with high trust and unanimous goals between the co-located entities, such coordination instruments can be used to enhance coordination and activate the ongoing communication as coordination instrument. This links coordination costs to ongoing communication.

Relational preconditions’ influence on tacit coordination

Tacit coordination finds its foundation in modularity and gives an expectation of coordination outcomes. The interpretation of modularity thus expands based on the pre-existing common ground among individuals and the ability to establish common ground through organizational or physical closeness between entities (Kraut et al. Citation2002; Ghoshal et al. Citation1994; Nohria and Ghoshal Citation1997; Clark Citation1996; Cramton Citation2001; Gutwin et al. Citation2004). Transcending competencies with various instruments such as promoting staff, physical and/or organizational coexistence is a theme for tacit coordination in this study. Tacit coordination includes coordination without the need for an ongoing communication mechanism (Camerer Citation2003; Srikanth and Puranam Citation2011). We find that preconditions influence the reason behind using transcending competencies. For example, Case 3 indicates that coordination is easy and based on informal contacts, as the civil servant managing Level 2 used to work within the company for many years before being promoted. As such, the coordination seems to be based on a history of interaction or common background, leading to shared values and trust (Stephenson and Schnitzer Citation2006; Whetten Citation1981). Further, different attitudes and relations between different organizations or divisions (Thomas et al. Citation2007; Alexander Citation1995) between the agencies, shaped by previous experiences (Whetten Citation1981), influence the reason for using transcending competencies. For instance, despite organizational interdependence in public organizations (Laegreid et al. Citation2014; Whetten Citation1981), specialization and fragmentation can affect agents’ perceptions of the required integration between the levels. Further, agents may focus on their own missions and perceive independence. Accordingly, organizational co-existence or physical co-location may have different coordination outcomes based on how the agents perceive dependence (Hibbard et al. Citation2001; Bouckaert et al. Citation2010). This links coordination costs, the organization, and interaction protentional to tacit coordination.

Conclusion

visualizes the influence of individuals and their relationships on coordination outcomes. The study connected each coordination mechanism with its respective preconditions, showing how these preconditions affect the use of each mechanism, and thus the coordination outcome. Studies tend to discuss the drivers or inhibitors of coordination and assume a desire to coordinate. Doing so misses the preconditions that make coordination mechanisms and instruments successful; that is, individuals and their relationships. Our research also has important managerial implications for practice and policies. If regional public organizations neglect the preconditions of coordination, they risk putting organizations in a situation where agencies may, despite their efforts on structural and functional aspects, be perceived as engaging in ‘policy dressing’: creating documents and formal instruments for coordination, albeit without the intention to coordinate. Such policy dressing hinders the insight in organizations and the accountability of the use of public funding. Such instruments can be used in isolation to accomplish their own goals. Furthermore, public organizations may expend considerable resources creating structures, mechanisms and instruments that ease coordination. By neglecting individuals’ intentions, interpretations and self-centredness, as well as their relationships as preconditions of coordination, public organizations risk missing the key issue of why differences in coordination outcomes exist.

Limitations and future research

Swedish public transport undergone de-regulation and structural changes (Enquist and Johnson Citation2013). In situations of change, the relevance of individual relations may have a greater impact on coordination outcomes than in stable situations; therefore, it may take an optimistic view of individual relations and the coordination outcome. However, if the relevance of individuals and their relationships on coordination outcomes is not due to de-regulation and structural changes, then the results of this study are important for regional public management, especially in countries with strong regional impacts such as Sweden. The policies of these regions and their implications for important public service silos such as healthcare, education and elderly care may depend more on individual-level factors than on national public settings. Such knowledge contributes to regional public management. Future studies should explore our findings in other regional public services with different characteristics. Public silos do not act in a vacuum; rather, the policy implementation and service delivery is based on interdependent policies that aim to create greater coherence and reduce redundancy, gaps and contradictions within and between policies (Peters Citation1998). Increasing our understanding of how individual relations may affect or influence the ability to implement policies requires further exploration.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (88 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors want to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their contribution. Special thanks to Sebastian Wiman who helped us with the layout of the model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2022.2134915.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

S. Davoudi

Sara Davoudi, PhD in business Administration and member of CTF- Service Research Center, Karlstad University, Sweden. Research on intersection between organizational perspective and user perspective in public context. Her research focus is on how activities between and within different administrative levels of public sector affect the service delivery to the public service user.

M. Johnson

Mikael Johnson, PhD, Senior lecturer in Business Administration at Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences. His research explores the intersection between sustainable development and service management, and management accounting in both private and public contexts. His research often elaborates the challenges related to bridging efficiency and effectiveness in organizations.

References

- Alexander, E. R. 1995. How Organizations Act Together: Interorganizational Coordination in Theory and Practice. London: Psychology Press.

- Allen, T. 1977. Managing the Flow of Technology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Aunger, J. A., R. Millar, J. Greenhalgh, R. Mannion, A. M. Rafferty, and H. McLeod. 2021. “Why Do Some Inter-Organisational Collaborations in Healthcare Work When Others Do Not? A Realist Review.” Systematic Reviews 10 (1): 1–22.

- Bache, I., and M. Flinders, eds. 2004. Multi-Level Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Baier, V. E., J. G. March, and H. Saetren. 1986. “Implementation and Ambiguity.” Scandinavian Journal of Management Studies 2 (3–4): 197–212. doi:10.1016/0281-7527(86)90016-2.

- Ballard, D. I., and D. R. Seibold. 2003. “Communicating and Organizing in Time: A Meso-Level Model of Organizational Temporality.” Management Communication Quarterly 16 (3): 380–415. doi:10.1177/0893318902238896.

- Bjurstrøm, K. H. 2021. “How Interagency Coordination is Affected by Agency Policy Autonomy.” Public Management Review 23 (3): 397–421. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1679236.

- Bouckaert, G., B. G. Peters, and K. Verhoest. 2010. The Coordination of Public Sector Organizations: Shifting Patterns of Public Management. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bourgault, J. 2007. “Corporate Management at Top Level of Governments: The Canadian Case.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 73 (2): 257–274. doi:10.1177/0020852307077974.

- Boyne, G. A. 2002. “Public and Private Management: What’s the Difference?” Journal of Management Studies 39 (1): 97–122.

- Bucklin, L. P., and S. Sengupta. 1993. “Organizing Successful Co-Marketing Alliances.” Journal of Marketing 57 (2): 32–46. doi:10.1177/002224299305700203.

- Caldwell, N. D., J. K. Roehrich, and G. George. 2017. “Social Value Creation and Relational Coordination in Public‐private Collaborations.” Journal of Management Studies 54 (6): 906–928. doi:10.1111/joms.12268.

- Camerer, C. 2003. Behavioral Game Theory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Campbell, J. L. 2001. ”Institutional Analysis and the Role of Ideas in Political Economy.” In The Rise of Neoliberalism and Institutional Analysis, edited by J.L. Campbell and O.K. Pedersen, 159–190. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Cannon, J. P., R. S. Achrol, and G. T. Gundlach. 2000. “Contracts, Norms, and Plural Form Governance.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 28 (Spring): 180–194.

- Cao, Z., and F. Lumineau. 2015. “Revisiting the Interplay Between Contractual and Relational Governance: A Qualitative and Meta-Analytic Investigation.” Journal of Operations Management 33 (1): 15–42. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2014.09.009.

- Castañer, X., and N. Oliveira. 2020. “Collaboration, Coordination, and Cooperation Among Organizations: Establishing the Distinctive Meanings of These Terms Through a Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Management 46 (6): 965–1001. doi:10.1177/0149206320901565.

- Chan, A., and S. Clegg. 2002. “History, Culture and Organizational Studies.” Culture and Organization 8 (4): 259–273.

- Chandler, A. D. 1962. Strategy and Structure: Chapters in History of the Industrial Enterprise. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Choi, T., and S. M. Chandler. 2015. “Exploration, Exploitation, and Public Sector Innovation: An Organizational Learning Perspective for the Public Sector.” Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance 39 (2): 139–151.

- Christensen, T. 2012. “Post-NPM and Changing Public Governance.” Meiji Journal of Political Science and Economics 1 (1): 1–11.

- Christensen, T., and P. Lægreid. 2010. “Increased Complexity in Public Organizations: The Challenges of Combining NPM and Post-NPM ” In Governance of Public Sector Organizations, edited by Lægreid, Per, Koen, Verhoest, 255–275. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Christensen, T., and P. Lægreid. 2011. “Complexity and Hybrid Public Administration: Theoretical and Empirical Challenges.” Public Organization Review 11 (4): 407–423.

- Clark, H. 1996. Using Language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Costumato, L. 2021. “Collaboration Among Public Organizations: A Systematic Literature Review on Determinants of Interinstitutional Performance.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 34 (3): 247–273. doi:10.1108/IJPSM-03-2020-0069.

- Cramton, C. D. 2001. “The Mutual Knowledge Problem and Its Consequences for Dispersed Collaboration.” Organisation Science 12 (3): 346–371.

- Enquist, B., and M. Johnson. 2013. Styrning Och Navigering I Regionala Kollektivtrafiknätverk. Karlstad University Press.

- Faraj, S., and Y. Xiao. 2006. “Coordination in Fast-Response Organizations.” Management Science 52 (8): 1155–1169. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0526.

- Fayol, H. 1949. General and Industrial Management. London: Pitman Publishing Company.

- Ferlie, E., Ashburner, L., L. Fitzgerald, and A. Pettigrew. 1996. The New Public Management in Action. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

- Galbraith, J. 1977. Organization Design. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

- Ghoshal, S., H. Korine, and G. Szulanski. 1994. “Interunit Communication in Multinational Corporations.” Management Science 40 (1): 96–110. doi:10.1287/mnsc.40.1.96.

- Gioia, D. A., K. G. Corley, and A. L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1177/1094428112452151.

- Gregory, B. 2006. “Theoretical Faith and Practical Works: undefined-Autonomizing and Joining-Up in the New Zealand State Sector.” In Autonomy and Regulation: Coping with Agencies in the Modern State, edited by T. Christensen and P. Laegreid, 137–161. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Gulati, R., F. Wohlgezogen, and P. Zhelyazkov. 2012. “The Two Facets of Collaboration: Cooperation and Coordination in Strategic Alliances.” The Academy of Management Annals 6 (1): 531–583. doi:10.5465/19416520.2012.691646.

- Gundlach, G. T., and E. R. Cadotte. 1994. “Exchange Interdependence and Interfirm Interaction: Research in a Simulated Channel Setting.” Journal of Marketing Research 31 (4): 516–532. doi:10.1177/002224379403100406.

- Gutwin, C., R. Penner, and K. Schneider. 2004. “Group Awareness in Distributed Software Development.” In Proceedings of the 2004 ACM conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (ACM), 72–81. New York.

- Heath, C., and N. Staudenmayer. 2000. “Coordination Neglect: How Lay Theories of Organizing Complicate Coordination in Organizations.” Research in Organizational Behavior 22: 153–191. doi:10.1016/S0191-3085(00)22005-4.

- Heide, J. B., and G. John. 1990. “Alliances in Industrial Purchasing: The Determinants of Joint Action in Buyer-Supplier Relationships.” Journal of Marketing Research 27 (1): 24–36. doi:10.1177/002224379002700103.

- Hibbard, J. D., F. F. Brunel, R. P. Dant, and D. Iacobucci. 2001. “Does Relationship Marketing Age Well?” Business Strategy Review 12 (4): 29–35. doi:10.1111/1467-8616.00189.

- Hickson, D. J., D. S. Pugh, and D. C. Pheysey. 1969. “Operations Technology and Organization Structure: An Empirical Reappraisal.” Administrative Science Quarterly 14 (3): 378–397. doi:10.2307/2391134.

- Hood, C. 2005. “The Idea of Joined-Up Government: A Historical Perspective.” In Joined-Up Government, edited by V. Bogdanor, 19–42. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hudson, B., B. Hardy, M. Henwood, and G. Wistow. 1999. “In Pursuit of Inter-Agency Collaboration in the Public Sector: What is the Contribution of Theory and Research?” Public Management an International Journal of Research and Theory 1 (2): 235–260.

- Jensen, M. C., and W. H. Meckling. 1976. “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure.” Journal of Financial Economics 3 (4): 305–360. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X.

- Johnson, M., J. K. Roehrich, M. Chakkol, and A. Davies. 2021. “Reconciling and Reconceptualising Servitization Research: Drawing on Modularity, Platforms, Ecosystems, Risk and Governance to Develop Mid-Range Theory.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 41 (5): 465–493. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-08-2020-0536.

- Kalra, J., M. Lewis, and J. K. Roehrich. 2020. “The Manifestation of Coordination Failures in Service Triads.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 26 (3): 341–358.

- Koop, C., and M. Lodge. 2014. “Exploring the Co-Ordination of Economic Regulation.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (9): 1311–1329. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.923023.

- Kraut, R., S. Fussell, S. Brennan, and J. Siegel. 2002. “Understanding Effects of Proximity on Collaboration: Implications for Technologies to Support Remote Collaborative Work.” In Distributed Work, edited by P. J. Hinds and S. Kiesler, 137–162. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lægreid, P., K. Sarapuu, L. H. Rykkja, and T. Randma-Liiv. 2015. “New Coordination Challenges in the Welfare State.” Public Management Review 17 (7): 927–939. doi:10.1080/14719037.2015.1029344.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Lodge, M., and D. Gill. 2011. “Toward a New Era of Administrative Reform? The Myth of Post‐npm in New Zealand.” Governance 24 (1): 141–166. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2010.01508.x.

- Lœgreid, P., T. Randma-Liiv, L. H. Rykkja, and K. Sarapuu. 2014. “Introduction: Emerging Coordination Practices in European Public Management.“ In: Organizing for Coordination in the Public Sector, edited by Lægreid, P., Sarapuu, K., Rykkja, L., Randma-Liiv, T., 1–17. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lusch, R. F., and J. R. Brown. 1996. “Interdependency, Contracting, and Relational Behavior in Marketing Channels.” Journal of Marketing 60 (October): 19–38.

- Mahoney, J. T., A. M. McGahan, and C. N. Pitelis. 2009. “Perspective – the Interdependence of Private and Public Interests.” Organization Science 20 (6): 1034–1052.

- Malone, T. W., and K. Crowston. 1990. “What is Coordination Theory and How Can It Help Design Cooperative Work Systems? Computer-Supported Cooperative Work.” In Proceedings of the 1990 ACM conference on computer-supported cooperative work, 357–370. Los Angeles, CA.

- March, J. G., and H. A. Simon. 1958. Organizations. New York: Wiley.

- Mayer, M., and R. Kenter. 2015. ”The Prevailing Elements of Public-Sector Collaboration.” In Advancing Collaboration Theory: Models, Typologies, and Evidence, edited by J. C. Morris and K. Miller-Stevens, 63–84. New York: Routledge.

- Metcalfe, L. 1994. “International Policy Co-Ordination and Public Management Reform.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 60 (2): 271–290. doi:10.1177/002085239406000208.

- Mintzberg, H. J. 1979. The Structuring of Organizations: A Synthesis of the Research. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Moore, M. H. 1995. Creating Public Value – Strategic Management in Government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Morgan, R. M., and S. D. Hunt. 1994. “The Commitment–trust Theory of Relationship Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 58 (July): 20–38.

- Moshtari, M., and P. Gonçalves. 2011. “Understanding the Drivers and Barriers of Coordination Among Humanitarian Organizations.” In POMS 23rd Annual Conference Chicago, 1–39.

- Mu, R., M. de Jong, and J. Koppenjan. 2019. “Assessing and Explaining Interagency Collaboration Performance: A Comparative Case Study of Local Governments in China.” Public Management Review 21 (4): 581–605. doi:10.1080/14719037.2018.1508607.

- Nohria, N., and S. Ghoshal. 1997. The Differentiated Network: Organizing Multi-National Corporations for Value Creation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Okhuysen, G.A., and B. A. Bechky. 2009. “10 Coordination in Organizations: An Integrative Perspective.” The Academy of Management Annals 3 (1): 463–502. doi:10.5465/19416520903047533.

- Olson, G. M., and J. S. Olson. 2000. “Distance Matters.” Human–computer Interaction 15 (2): 139–178.

- Osborne, S. P. 2006. “The New Public Governance? 1.” Public Management Review 8 (3): 377–387. doi:10.1080/14719030600853022.

- Osborne, S. P., edited by. 2010. The New Public Governance?: Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance. London: Routledge.

- Ouchi, W. G. 1980. “Markets, Bureaucracies, and Clans.” Administrative Science Quarterly 25 (1): 129–141. doi:10.2307/2392231.

- Palmatier, R. W., R. P. Dant, and D. Grewal. 2007. “A Comparative Longitudinal Analysis of Theoretical Perspectives of Interorganizational Relationship Performance.” Journal of Marketing 71 (4): 172–194. doi:10.1509/jmkg.71.4.172.

- Parkhe, A. 1993. “Strategic Alliance Structuring: A Game Theoretic and Transaction Cost Examination of Interfirm Cooperation.” Academy of Management Journal 36 (August): 794–829.

- Perrow, C. 1967. “A Framework for the Comparative Analysis of Organizations.” American Sociological Review 32 (2): 194–208. doi:10.2307/2091811.

- Peters, G. B. 1998. “Managing Horizontal Government: The Politics of Coordination.” Public Administration 76 (2): 295–311.

- Peters, B. G. 2018. “The Challenge of Policy Coordination.” Policy Design and Practice 1 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/25741292.2018.1437946.

- Pollitt, C. 2003. “Joined-Up Government: A Survey.” Political Studies Review 1 (1): 34–49. doi:10.1111/1478-9299.00004.

- Puranam, P., M. Raveendran, and T. Knudsen. 2012. “Organization Design: The Epistemic Interdependence Perspective.” Academy of Management Review 37 (3): 419–440. doi:10.5465/amr.2010.0535.

- Roehrich, J. K., K. Selviaridis, J. Kalra, W. Van der Valk, and F. Fang. 2020. “Inter-Organizational Governance: A Review, Conceptualisation and Extension.” Production Planning & Control 31 (6): 453–469. doi:10.1080/09537287.2019.1647364.

- Rogers, D. L., and D. Whetten. 1982. Interorganizational Coordination: Theory, Research, and Implementation. Ames, IO: Iowa State University Press.

- Saunders, M., P. Lewis, and A. Thornhill. 2009. Research Methods for Business Students. 5th ed. Essex, UK: Pearson Education.

- Scott, W. R., and G. F. Davis. 2007. Organizations and Organizing: Rational, Natural, and Open Systems Perspectives. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Siguaw, J. A., P. M. Simpson, and T. L. Baker. 1998. “Effects of Supplier Market Orientation on Distributor Market Orientation and the Channel Relationship: The Distributor Perspective.” Journal of Marketing 62 (July): 99–111.

- Simon, H. A. 1962. The Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Srikanth, K., and P. Puranam. 2011. “Integrating Distributed Work: Comparing Task Design, Communication and Tacit Coordination Mechanisms.” Strategic Management J 32 (8): 849–875. doi:10.1002/smj.908.

- Srikanth, K., and P. Puranam. 2014. “The Firm as a Coordination System: Evidence from Software Services Offshoring.” Organization Science 25 (4): 1253–1271. doi:10.1287/orsc.2013.0886.

- Stephenson, M., Jr., and M. H. Schnitzer. 2006. “Interorganizational Trust, Boundary Spanning, and Humanitarian Relief Coordination.” Nonprofit Management & Leadership 17 (2): 211–233.

- Stover, J. F. 1970. The Life and Decline of the American Railroad. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Taylor, F. W. 1916. “The Principles of Scientific Management. Bulletin of the Taylor Society, December.” In Classic Organization Theory, edited by J. M. Shafritz and J. S. Ott, 66–79. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. Reprinted.

- Thomas, G. F., E. Jansen, S. P. Hocevar, and R. G. Rendon. 2007. “Field Validation of Collaborative Capacity Audit.” ( No. NPS-AM-07-123).

- Thompson, J. D. 1967. Organizations in Action: Social Science Bases of Administrative Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Thomson, A. M., and J. L. Perry. 2006. “Collaboration Processes: Inside the Black Box.” Public Administration Review 66: 20–32.

- Try, D., and Z. Radnor. 2007. “Developing an Understanding of Results‐based Management Through Public Value Theory.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 20 (7): 655–673. doi:10.1108/09513550710823542.

- Tushman, M., and D. Nadler. 1978. “Information Processing as an Integrating Concept in Organization Design.” Academy of Management Review 3 (3): 613–624.

- Verhoest, K., and G. Bouckaert. 2005. ”Machinery of Government and Policy Capacity: The Effects of Specialisation and Coordination.” In Policy Capacity, edited by M. Painter and J. Pierre, 92–111. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Wathne, K. H., and J. B. Heide. 2000. “Opportunism in Interfirm Relationships: Forms, Outcomes, and Solutions.” Journal of Marketing 64 (October): 36–51.

- Whetten, D. A. 1981. “Interorganizational Relations: A Review of the Field.” The Journal of Higher Education 52 (1): 1–28. doi:10.2307/1981150.

- Whetten, D. A., and T. K. Leung. 1979. “The Instrumental Value of Interorganizational Relations: Antecedents and Consequences of Linkage Formation.” Academy of Management Journal 22 (2): 325–344. doi:10.5465/255593.

- Wilkins, P., J. Phillimore, and D. Gilchrist. 2016. “Public Sector Collaboration: Are We Doing It Well and Could We Do It Better?” Australian Journal of Public Administration 75 (3): 318–330. doi:10.1111/1467-8500.12183.

- Willem, A., and M. Buelens. 2007. “Knowledge Sharing in Public Sector Organizations: The Effect of Organizational Characteristics on Interdepartmental Knowledge Sharing.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 17 (4): 581–606.

- Williamson, O. E. 1975. Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications. New York: The Free Press.

- Wilson, J. Q. 1989. Bureaucracy: What Government Agencies Do and Why They Do It. New York: Basic Books.

- Woodward, J. 1970. Industrial Organization: Behaviour and Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.