?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study examines the role of change agents, city leaders, and their networks in facilitating interlocal collaboration in environmental governance. We propose an Agent Network Collaboration (ANC) model that brings individual managers, as change agents, back into the study of the interlocal agreement (ILA). We argue that the leadership transfer networks, the collection of city managers’ career paths that connect cities, serve as an important channel for interlocal collaboration. With a dyadic panel data set of 14 cities in the Pearl River Delta region in China, we find substantive impacts of managers’ career paths on the formation of ILAs.

1. Introduction

The issues of fragmentation pose significant challenges to environmental governance at the local level. Horizontal collective action problems present severe challenges to local governments as cities located in the same region find it difficult to achieve efficient policy or governance outcomes when their decisions spill across geographic boundaries (Feiock and Scholz Citation2010; Yi et al. Citation2018). One approach adopted by cities to mitigate horizontal fragmentation is by entering into interlocal agreements (ILAs). While the formation of ILAs has been widely studied in the US and Europe, it has not been sufficiently addressed in other national contexts, especially in Asia.

Environmental issues pose significant challenges to policymakers in China, in dealing with deteriorating air, water, and waste pollution across local jurisdictions (Yi and Liu Citation2015). While national and local policies have been adopted to protect the environment (Tang, Liu, and Yi Citation2016), local governments are still faced with a collective action dilemma where local authorities and policy designs are fragmented and insulated. In response to the ineffectiveness of fragmented environmental policies, local jurisdictions in China increasingly resort to collaborative approaches to solving regional environmental issues (Huang et al. Citation2017).

Drawing upon existing literature on administrator networks (Feiock, Lee, and Park Citation2012) and interlocal agreements (Andrew Citation2009) in the US, we investigate how the network of city leaders affects the formation of interlocal agreements on environmental issues in Guangdong Province, China. In this study, we explicitly focus on the role of change agents, city leaders, and their networks in influencing the formation of interlocal collaboration. We propose an Agent Network Collaboration (ANC) model that brings individual managers, as change agents, back into the study of the interlocal agreement. We hypothesize that the leadership transfer network, the collection of the career paths of city managers that connect cities, serves as an important channel for interlocal collaboration. Specifically, we hypothesize that two cities are likely to have more ILAs between them when they have career path connections through the leadership transfer network.

With a dyadic panel data set of 14 prefecture-level cities in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region in Guangdong Province, China, from 2009 to 2015, we examine the impact of leadership transfer networks on the adoption of ILAs with dyadic panel zero-inflated negative binomial models. Next, we conduct a review of the extant literature on interlocal collaborations. We then propose an ANC model to explain the role of change agents in the formation of interlocal agreements. We then focus on the interlocal agreement in the context of China and formulate testable hypotheses based on ANC. We then present the sources of the data and demonstrate the operationalization of the variables, as well as the statistical methodology. We then report the results of the statistical analyses. The study concludes with practical and theoretical implications, in tandem with future directions of the research on the role of change agents in governance.

2. Interlocal collaboration

Under the theory of public choice, inter-jurisdictional spillover of policy externality could be effectively controlled by providing basic public services, such as police and sanitation services, within municipal boundaries (Ostrom and Ostrom Citation1971; Lowery Citation2000). A negative consequence of jurisdictional boundaries in service delivery is the problem of horizontal fragmentation, under which jurisdictions often find it hard to coordinate activities across geographic boundaries (Shrestha and Feiock Citation2009). The horizontal fragmentation issues could be mitigated by ILAs through bilateral or multilateral negotiations among local governments. ILA is a feasible and popular strategy to reallocate the superfluous capacity of public services from one jurisdiction to another (Feiock, Lee, and Park Citation2012). It provides the jurisdiction with lower levels of public service with external financial and professional resources through a formal contractual relationship between partnering jurisdictions, lowering the overall cost of public service in a region through the economics of scale (Carr, LeRoux, and Shrestha Citation2009).

Robust ILA literature has developed over the last decades by constantly rejuvenating theoretical perspectives and unveiling empirical evidence of the driving forces and consequences of collaboration. Specifically, a thread of studies focuses on the relationship between intergovernmental cooperation and policymakers. From the perspective of institutional arrangement, Krueger and McGuire (Citation2005) found that the city manager form of government facilitated ILA formation because city managers shoulder no direct responsibility to the constituency and are resistant to rent-seeking behaviours. Through in-depth interviews, Zeemering (Citation2008) explored how the shared responsibility between city managers and council members shaped the development of interlocal collaboration. Through the exponential random graph model, Feiock et al. (Citation2010, Citation2012) put forward that elected officials and administrators relied on their network positions to make low-risk collaboration decisions in economic development.

Besides, another stream of relevant literature focuses on interlocal service collaboration. Studies have examined the impact of individual-level social networks of managers, such as their joint participation in the regional association, joint membership in the professional association, and similar academic training in MPA, on interlocal service cooperation (LeRoux and Carr Citation2007; LeRoux, Brandenburger, and Pandey Citation2010). Lee, Feoick, and Lee (Citation2012) investigated how city managers’ perceptions about competition and cooperation influenced regional cooperation. LeRoux and Pandey (Citation2011) found that city managers’ career ambition to higher-level positions rather than the altruistic motives led to pursuing service collaboration. Hawkins, Hu, and Feiock (Citation2016) investigated how the informal policy network interacting with regional institutions affected the formation of formal contractual inter-municipal relationships.

Consisting of different types of public services, ILAs themselves are networks involving different levels of local governments, private institutions, and non-profit actors (Thurmaier and Wood Citation2002; Chen and Thurmaier Citation2009; Yi, Berry, and Chen Citation2018). They centre on the multiplex nature of public service delivery networks (Andrew Citation2009; Kwon and Feiock Citation2010; Shrestha and Feiock Citation2013; Chen, Suo, and Ma Citation2015) by treating cities as nodes and the service agreements among them as links. For these studies, the key research question focuses on why cities choose particular collaborative partners in providing public services.

However, little of the current research examines the impact of the career path trajectory of local administrators on the formation of ILAs in environmental governance. As argued by Thurmaier and Wood (Citation2002), it is very difficult to distinguish an organization’s brokerage role from crucial individuals who might be key stakeholders in promoting the interactions among organizations. To address this challenge, we shift the focus from professional social networks of public managers to public administrators’ career path networks by exploring how the career path network of city managers affects the formation of ILAs among cities, controlling for traditional factors driving interlocal cooperation. We propose an ANC model to provide a theoretical explanation for how the career trajectories of city managers, as social networks, affect the formation of ILAs among local jurisdictions. In the next section, we present the mechanisms behind the ANC model and propose two ANC hypotheses that explain the formation of ILAs in the context of China.

3. An agent network collaboration model

In the study of policy innovation and diffusion, some scholars have proposed network-based explanations for the diffusion of policy innovations across jurisdictions (Yi, Berry, and Chen Citation2018; Yi and Chen Citation2019). The basic argument was that public managers carry policy innovations between locations along their career paths because the knowledge and experience gained in the previous work locations help the public managers adopt and implement policy innovations in the new jurisdiction. Following the same logic, we propose an ANC model to explain interlocal collaboration, accounting for the impact of inter-jurisdictional personnel flows from a social network perspective. We contend that the agent network generated by the career trajectories of local government officials provides a direct channel that facilitates interlocal cooperation.

Here, we define the agent as professional public administrators with leverage over policymaking and policy implementation. Most public administrators develop a long career in which they move between cities as they gain professional experiences over time and in different locations (Teodoro Citation2009). Through professional transfers and job mobility from one jurisdiction to another, these mobile agents serve as linkages connecting jurisdictions (Yi, Berry, and Chen Citation2018). The resulting career path network thus presents an underlying network that connects jurisdictions with the professional career paths of public administrators (Yi, Berry, and Chen Citation2018). We argue that the agent network connecting jurisdictions, as defined by the career path trajectories of these agents, facilitate the transmission of information, the development of trust, and finally the establishment of partnerships between two local governments.

In the terminology of social network analysis, local governments are ‘nodes’ in the agent network, and the career paths of the agents serve as ‘links’ or ‘channels’ connecting the cities. We argue that the network of personnel flows facilitates interlocal collaboration, under the assumption that transaction costs associated with information asymmetry or opportunistic withdrawal acts can be mostly reduced with the unique social connections between two cities through the career path network of city managers. The ANC model is compatible with the Institutional Collective Action (ICA) framework (Feiock Citation2013) due to its emphasis on the role of networks and horizontal collaboration. Therefore, we demonstrate how the career path network of city managers facilitates interlocal collaboration from the transaction cost perspective that is central to ICA in explaining interlocal collaboration choice.

If city manager A was transferred from City X to City Y, then A will possess several important characteristics pertaining to both cities. First, the agent has policy-relevant information and knowledge of local policy needs in both cities. This means that A understands the social, economic, and political context of both cities. Second, the agent has key social network contacts in both cities. Being a city manager in City X, A probably is familiar with elected officials, agency heads, staff members, and local policy activists in City X. These social contacts will most likely, if not all, remain in City X after A’s transfer from X to Y. Social capital will be very useful when A is engaged in formulating interlocal collaborative relationships between City X and City Y.

We focus on three dimensions of transaction costs: information cost, bargaining cost, and enforcement cost, as these are theoretically relevant and practically observable. First, the career path network of the city managers facilitates interlocal collaboration by reducing the information cost for the decision-makers. Information cost refers to the burden to rationally calculate the costs and benefits of proposed policy action, in our case, interlocal collaboration. As shown by Feiock, Steinacker, and Park (Citation2009), network relationships help reduce the information cost associated with regional economic partnerships. The mastery of policy-relevant information in both cities makes it easier for the city manager to identify needs and opportunities for interlocal collaboration and to find the right policy window in pushing for collaborative action.

Second, the career path network of the city managers facilitates interlocal collaboration by reducing the bargaining and enforcement costs of a collaborative agreement between the two locations. Bargaining cost is a type of transaction cost that measures the difficulties in negotiating a deal among parties involved, and enforcement cost refers to the cost associated with enforcing and monitoring the reforms (Inman and Rubinfeld Citation1997). Knowing people on the other side of the bargaining table on a personal level allows the city manager to build trust among the old colleagues. Dealing with a familiar friend/colleague facilitates signing the contract and eventually sustaining the collaboration.

To test our ANC model, we examine the impact of the career path network of city managers in the context of interlocal environmental collaboration in the Pearl River Delta, China. We next present the context of our study, along with testable hypotheses.

4. Hypotheses

Decentralized collaborative governance is increasingly popular among local governments in solving regional policy problems, such as public service delivery (Jing and Savas Citation2009), natural disaster insurance system (Wang and Yin Citation2012), and environmental governance (Chen, Suo, and Ma Citation2015). In this article, we focus on environmental governance in cities located at the Pearl River Delta (PRD). The PRD is one of the most industrialized metropolitans in China, with a population of 60 million and a GDP accounting for 10% of China’s total GDP (Yi, Berry, and Chen Citation2018). Environmental problems become increasingly important on the policy agenda of local governments, as industrial development resulted in severe water, air, and soil pollution in the region (Chen, Suo, and Ma Citation2015). Chinese cities often resort to formal contracts that define the regional policy problems, policy actors involved, regional policy designs, collaborative activities, and enforcement mechanisms (Shen, Feiock, and Yi Citation2017). Not only in PRD but the ILAs have also burgeoned in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and Yangtze River Delta region, taking various forms including informal ILAs and imposed authority to address the institutional collective action dilemma (Yi, Berry, and Chen Citation2018). In this article, we examine the extent to which cities engage in interlocal environmental contracts, with a focus on the impacts of the career path network of city managers.

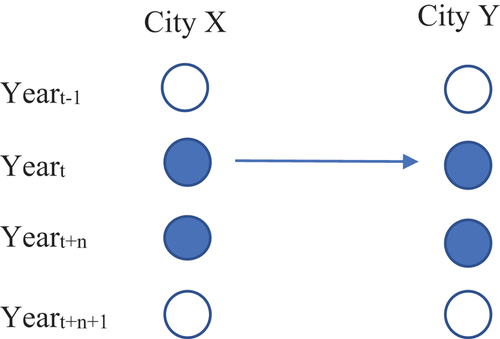

As discussed in the theory section, we argue that the career path network of city managers facilitates the transmission of information and nurtures mutual understanding and trust, which are conducive to partnership building between two local governments. Specifically, in the context of environmental governance, we expect that if a city manager is transferred from City X to City Y in his/her career trajectory, the two cities are more likely to establish interlocal environmental agreements as a result of the connection brought by the key personnel transfers. We assume that only incumbent managers can activate the window of opportunity for City X and City Y to partner. On average, city managers’ tenure varies, with 3 years in China (Yi, Berry, and Chen Citation2018), and 6 to 8 years in the US (Watson and Hassett Citation2004). The longer managers stay in the position in City Y, the widened the temporal window for a partnership opportunity. We term this proposition the direct agent network hypothesis (H1). provides a visual illustration of the hypothesis.

Figure 1. Direct agent network hypothesis.

Direct Agent Network Hypothesis (H1):

Two cities (X and Y) are likely to establish more interlocal environmental agreements, when a city manager transferred from X to Y, and that the city manager is in office in Y during Yeart to Yeart+n.

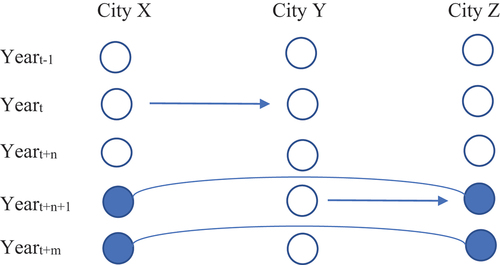

In practice, many managers have career trajectories that span over more than two jurisdictions. In such cases, the career transfer events create not only direct linkages between the most recent job locations but also indirect linkages between the current work location and all previous work locations. presents how such indirect network linkage works. Assume a city manager moves from City X to City Y in Yeart, and stays in office in City Y until Yeart+n. Then he/she moves from City Y to City Z in Yeart+n+1, and stays in office in City Z until Yeart+m. Based on H1, we expect that City X and Y will have an enhanced probability for more interlocal agreements during Yeart and Yeart+n, and that City Y and Z will have a higher probability during Yeart+n+1 and Yeart+m. The second career transfer event creates not only a direct linkage between Y and Z but also an indirect linkage between X and Z. In network terminology, the indirect linkage is a result of transitivity in social networks. Practically, it makes sense that a manager typically maintains his/her old social connections along his/her career trajectory. It should be noted that the indirect network effect is also temporary along with the tenure of managers. The indirect linkage between X and Z exists as long as the manager works in City Z.

Figure 2. Indirect agent network hypothesis.

Indirect Agent Network Hypothesis (H2):

Two cities (X and Z) are more likely to establish more interlocal environmental agreements, when a city manager transferred from X to Y, then from Y to Z, and that the city manager is in office in Z during Yeart to Yeart+n.

5. Method

The dependent variable for this study is the number of interlocal environmental agreements signed between any two cities in the PRD. Accordingly, we employ a novel non-directed dyadic count model analysis at the dyad-year level with an exhaustive combination of 14 municipalities over 7 years from 2009 to 2015. Every city is matched with the rest of the cities in PRD to form a dyad. This gives us a final sample size of 637. The reason for a non-directed model is that we consider the agreement between City X and City Y/Z, the same as the agreement between City Y/Z and City X. Our unit of analysis is dyad-year, therefore variables included in the model only consider the dyadic relationships between two cities, such as absolute differences in socio-economic variables. The dyadic panel data analysis has been applied to innovation diffusion studies (Gilardi and Füglister Citation2008) and international relation studies, such as international trade and civil wars (Robst, Polachek, and Chang Citation2007; Fuhrmann Citation2009; Tir and Ackerman Citation2009). We introduce these models to the study of interlocal collaboration because they allow us to embed the dynamic career path network into a panel data structure and then rigorously test the impacts of the network by estimating the coefficients of the models. While dynamic network analysis is an alternative possibility in terms of empirical strategy, it only works when the dependent variable is a binary variable that measures the existence of agreements between a pair of cities. Dyadic panel count models are the best strategy given the count format of our dependent variable, that is, the number of interlocal agreements between dyads of cities.

To model the count variable as the dependent variable, we can choose among Poisson, negative binomial, zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP), zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB), or hurdle models. Seventy-nine percent of dependent variable observations are ‘0’s, potentially making the zero-inflated regression to be a preferred method. The zero-inflated model, called the mixture model, assumes there are two distinct origins to generate zero – structural source and sampling source (Haslam et al. Citation1992; Yusuf, Afolabi, and Agbaje Citation2018), which both denote no agreement signed by the two cities. The sampling zero is from the usual negative binomial distribution and happens due to random chance. While structural zero is caused by the reason that makes them impossible to sign ILA with others. For instance, geographically distant cities will not engage in projects like sewage treatment (Hu, Pavlicova, and Nunes Citation2011). Structural zero exists because no niche is provided to develop partnerships, while sampling zero indicates that there is a niche but not filled (Lubell et al. Citation2002).

Zero-inflated models, comprised of both logit and count models, can differentiate structural zero and sampling zero, respectively. Logit model predicts the probability of non-existent cooperative opportunity, and count model predicts the expected number of ILAs where cooperative opportunity exists. Built upon Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework, Lubell et al. (Citation2002) argued that logit model concerns the setup of niches for partnership, where the benefits of resolving severe environmental problems are the main drivers for generating partnership opportunity, whereas the negative binomial equation can examine how transaction costs influence the strengths of the partnership. By assuming that all covariates have equal chances to influence both stages of ZINB, we would have the same batch of variables in the logit and negative binomial portions in ZINB to avoid deliberate selectionFootnote1. Hurdle negative binomial regression, on the other hand, assumes that all the zero observations of the ILA are originated from the structural source and all the positive observations are from the truncated binomial distribution (Hu, Pavlicova, and Nunes Citation2011). The dependent variable is overdispersed with a standard deviation larger than the mean, making negative binomial models better than Poisson models. ZINB, together with negative binomial and hurdle NB as robustness checks, would be employed in this study with the same model specificationsFootnote2.

Mathematically, we use the following formula in our empirical models:

where is the number of interlocal agreements signed between dyads of cities in Yeart.

is the intercept. Time-variant

represents our variable of interest, which measures the career path network between dyads of cities in Yeart. And

is the corresponding coefficient.

is a set of control variables that measure socioeconomic, demographic, public finance, geographic, and environmental factors of the dyads. All control variables, except for the geographic proximity variable, are time-varying.

are the corresponding estimated coefficient.

is the year-fixed effects, which are included to control for temporal dependency.

6. Measurement and data

In this section, we discuss the data source, measurement, and coding of the dependent variable, variables of interest, and control variables. Data sources and measurements are presented in . The descriptive statistics and correlation are presented in , where we can see that agent network variables do not strongly correlate with other covariates, thereby circumventing the problem of multicollinearity.

Table 1. Measurement and data sources.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlation.

6.1. Dependent variable

The dependent variable for this study is the number of ILAs for each dyad over time. In the interlocal collaboration literature, the number of partnerships has been frequently applied as the typical measure to capture the degree of collaboration (LeRoux, Brandenburger, and Pandey Citation2010; Wang and Fan Citation2022). The data for the dependent variable is based on a dataset of 123 interlocal agreements on sustainability and environmental governance in PRD. The ILAs were searched from news reports in the mainstream local media, with a combination of keywords of ‘cooperation’ (hezuo), ‘agreement’ (xieyi), and ‘environmental protection’ (huanjingbaohu). Considering that environmental problems are high-profile issues, media would pay close attention to them. Though some ILAs might be confidential to the public, we contend that the media sources can cover a large number of ILAs to disclose the collaboration degree among cities. The environmental ILAs in our dataset cover at least one of the following issue topics: ecological development, energy infrastructure development, eco-environment monitoring, water service cooperation, urban flood control, and water resource protection. Most of the ILAs are bilateral, and only six multilateral agreements were identified. Regardless, we checked and confirmed the robustness of the results by deleting the multilateral cases. We count the total number of ILAs for each pair of cities for a given year. Therefore, the dependent variable captures the strength of cooperation in every pair of cities in PRD relating to environmental issues. By composing the dyadic dataset generated by pairing every possible city in PRD, which has been confirmed to have at least signed one ILA, we are able to expand the traditional entity-year observation into a larger sample consisting of dyad-year observations.

From descriptive statistics in , some dyads of cities coordinate quite often, but some do not, ranging from 0 to 22. In 2009, Dongguan-Shenzhen and Huizhou-Shenzhen signed 22 ILAs. Many dyads of cities have not signed any collaborative agreements from 2009 to 2015, leading to many ‘0’s in the dependent variable. The dyadic transformation of our dataset includes the ‘impossible zero’ by allowing the dyad with no ILA to exist. This practice is favoured by some scholars (Dorff and Ward Citation2013; Carlson Citation2019), arguing that the explanation of excessive zero and the distinction between structural zero and random zero are empirically and statistically meaningful (Harris and Zhao Citation2007; Boucher, Denuit, and Guillen Citation2009; Carlson Citation2019). By contrast, some international relationship (IR) studies favour ruling out the impossible zero dyads (Morrow and Jo Citation2006). There is literally no relationship between most country dyads (King and Zeng Citation2001a, Citation2001b). We are interested in studying the ILAs between cities in the PRD, which are economically, geographically, and politically proximate to one another. Environmental issues like air and water pollution in one city are likely to get disseminated into other cities, therefore it is reasonable to include all cities in the PRD that have the potential to launch cooperation to tackle common problems.

6.2. ANC network variables

We have two ANC variables that allow us to separately test the Direct Agent Network Hypothesis (H1) and the Indirect Agent Network Hypothesis (H2). The data on the career path network were collected by reviewing the resumes of 120 municipal public administrators, including city mayors and party secretaries. In China, the local government officials are not elected by citizens or the electorate. We take these two types of government officials as our operationalization of city managers in the context of China. Both party secretary and mayor have the same administrative rank and enjoy ‘de facto power over policymaking and resource allocation’ (Jiang Citation2018, 7). Both of them are considered key decision makers in interlocal cooperation (Chen et al. Citation2019; Liu et al. Citation2021). The leadership mobility phenomenon, the reshuffling of leadership in China, is not random but based on the ‘institutionalized performance-based promotion system to generate incentives for local government agents’ (Jiang Citation2018, 5). The mobility of leadership is not market-oriented like in the western context (Yi, Berry, and Chen Citation2018). In China, the higher-level officials are evaluated and decided by Central Organization Department with emphasis on their morality, competence, diligence, accomplishment, and probity, which are not connected to specific policies (Su et al. Citation2012; Jiang Citation2018). Empirically, the mobility and promotion of leadership were evaluated mostly on economic performance, while other factors play minimal roles in the rotation decision of leaders in China (Li and Zhou Citation2005). Hence, we assume that the mobility of leadership is exogenous to the policymaking process of environmental ILAs.

The career transfer events involve a series of scenarios. For example, agent A could transfer from the mayor position in City X to the party secretary position in City Y. We only code career paths of agents at least as mayor or higher (i.e. mayor and party secretary), which are entitled with legitimate influence over decision-making when they hold positions. The direct agent network hypothesis (H1) is tested with a variable of Direct ANCx,y,t. It is coded as ‘1’ when either mayor or party secretary is transferred from City X to City Y (or from City Y to City X) and takes office in City Y (or City X) from Yeart to Yeart+n and is coded as ‘0’ when no mayor or party secretary is transferred between City X and City Y because they are promoted internally or outside of the PRD. The indirect agent network hypothesis (H2) is tested with a variable of Indirect ANCx,z,t. It’s coded as ‘1’ when either mayor or party secretary is transferred from City X to City Y to City Z (or from City Z to City Y to City X) and takes office in City Z (or City X) from Yeart to Yeart+n and is coded as ‘0’ when there is no ‘two-step away’ work experience connecting City X and City Z. The Indirect ANCx,z,t captures the more temporally distant working experience, representing the ‘two-step away’ relationships between a dyad of cities through the career path network.

6.3. Control variables

Prior ILAx,y/z,t is a dummy variable with ‘1’ indicating that dyad of Cityx and Cityy/z had signed ILA before Yeart, and ‘0’ indicating that they didn’t have a cooperative relationship before Yeart. We expect that past cooperative relationships open opportunities for new future cooperation. Lubell et al. (Citation2002) estimated the formation of watershed partnerships by including past partnerships as controls and confirmed the positive effect. In terms of the environment-related factors, we include four variables of Waste Waterx,y/z,t, Industry Waste Gasx,y/z,t, Industry Solid Wastex,y/z,t, and Industry Dustx,y/z,t to capture the absolute differences in environmental conditions and characteristics between dyads of Cityx and Cityy/z. Lubell et al. (Citation2002) argued that deteriorated environment influences the formation of the partnership, which is a potential solution to the environmental problem. It is therefore expected that environmental conditions in Cityx and Cityy/z would impact their decision to join the inter-governmental collaboration.

Existing studies point out that climate policy adoption is attributed to socioeconomic and demographic factors (Krause Citation2011; Liu and Yi Citation2021). Population_Growthx,y/z,t, Budget_Growthx,y/z,t, City Sizex,y/z, and GDP Growthx,y/z,t are included to control for the absolute difference of socioeconomic conditions between Cityx and Cityy/z. Existing literature points out that Chinese leadership turnover is closely related to leaders’ economic performance (Li and Zhou Citation2005; Xu Citation2011), potentially confounding the influence of agent networks on ILA. We anticipate that more similar cities are likely to get engaged in the bilateral relationship, while discrepant cities tend to encounter higher transaction costs. In addition, geographic proximity or contiguity is often considered an important factor (LeRoux and Carr Citation2007; Shrestha and Feiock Citation2009) because local governments in geographically dense metropolis have more formal or informal interactions with environmental issues. To capture the time-invariant geographic adjacency, we construct the variable of Proximityx,y/z, which is coded as ‘1’ to indicate that Cityx and Cityy/z share a border and is coded as ‘0’ to indicate that two cities do not share a border with one another.

7. Results

presents the results of ZINB and NB regressions that estimate the formation of ILAs. In the negative binomial model, a positive coefficient indicates a higher count of ILAs between two cities. In the logit model in ZINB, a positive coefficient implies a higher probability of predicting two cities having no ILAs. In Model 1, we include Direct Agent Networkx,y,t in both negative binomial and logit models to get the effects of the direct career path network connection. In Model 2, Indirect Agent Networkx,z,t is added to estimate the indirect career path effects. Model 3 includes Prior ILAx,y/z,t and dyadic environmental characteristics. Model 4 includes the socioeconomic and demographic variables to compose the full model. Model 5 employs standard errors clustered on 91 dyads to adjust for interdependency within each dyad by assuming independency within each dyad. Serving as a robustness test of ZINB results, model 6 is the hurdle negative binomial regression and model 7 carries out the traditional negative binomial regressionFootnote3. The variables of interest are still positive and statistically significant. To provide more intuitive explanations, we include the average marginal effect (AME) in Model 8 based on Model 5 by setting the predicted probability of zero ILAs (logit model) at its mean.

Table 3. Zero-inflated negative binomial models for ILAs.

For each model, AIC and BIC in smaller values indicate a better fit across model specifications. By comparing Models 5, 6, and 7, we can see that hurdle NB is superior and ZINB is superior to NB in light of smaller AIC.Footnote4 Nevertheless, hurdle NB attributes all zero observations to structural sources, which might not be a realistic assumption in interlocal collaboration. Hence, the ZINB result is still preferred. In terms of Vuong tests, which are all significant across models, it indicates that ZINB is better than the standard negative binomial model. The alpha statistics compare the ZINB with the ZIP. They are statistically significant across different specifications, indicating that the ZINB models are preferred over ZIP.

Direct Agent Networkx,y,t is statistically significant and positive in the negative binomial model in ZINB across model specifications, which renders support for the first hypothesis. According to Model 5, the number of ILAs between Cityx and Cityy with a direct agent network connection enhances 83.2% (exp(0.605)-1) compared to cities without a direct agent network connection, ceteris paribus. To test the second hypothesis, we examine the effect of Indirect Agent Networkx,z,t, which is significantly positive across negative binomial models in ZINB and therefore substantiates the second hypothesis. In Model 5, the number of ILAs between Cityx and Cityy with an indirect agent network connection enhances 120% (exp(0.789–1) compared to cities without an indirect agent network connection, ceteris paribus. The results in Models 6 and 7 also corroborate the significant effects of direct and indirect agent networks on ILAs, ensuring the robustness of the results in ZINB. The estimation results from the logit section in ZINB (model 5) substantiate that two cities connected through an indirect agent network are more likely to break the impossible zero and offer an opportunity for cities to form ILAs. While the logit section in hurdle NB (model 6) confirms that both direct and indirect network matter to overcome the structural zero.

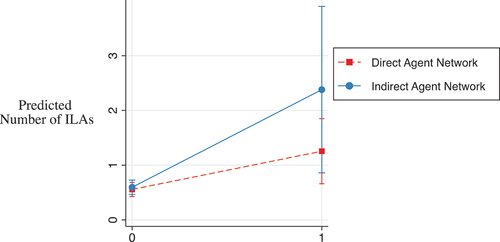

In Model 8, the average marginal effect (AME) calculates the mean differences in the predicted count of ILAs when the dichotomous variable changes from 0 to 1. On average, Cityx and Cityy with direct agent network connection (Direct Agent Networkx,y,t = 1) sign on average 0.699 more ILAs than cities with no direct agent network connection, ceteris paribus. On average, Cityx and Cityy with an indirect agent network (Indirect Agent Networkx,z,t = 1) sign on average 1.784 more ILAs than cities with no indirect ANC, ceteris paribus. The predicted number of ILAs is illustrated in . The predicted counts of ILAs of Direct Agent Networkx,y,t and Indirect Agent Networkx,z,t are almost the same when they are in the reference group of 0.

Figure 3. Effects of direct and indirect ANC on ILAs.

Now, turning to the effect of controls in Model 8. Prior ILA x,y/z,t exerts substantive influence on the ILAs. When Cityx and Cityy had signed prior ILAs, the predicted number of ILAs would be 2.219 higher than those without signing prior ILAs. It confirms Feiock and Park’s (Citation2005) contention that collaborative relationships are durable once governments establish social capital through initial interactions. To test whether the prior relationship has an imminent effect on ILA, we include the lagged ILA in Appendix . Regarding environmental controls, only Industrial Waste Gasx,y/z,t and Industrial Solid Wastex,y/z,t are significant, but the multicollinearity between environmental factors as indicated in would overshadow the results. By entering these two variables separately into the model, their significant effects as anticipated vanish. In terms of the socioeconomic and demographic variables, Population_Growthx,y/z,t and GDP Growthx,y/z,t impose significant negative impacts on the predicted count of ILAs, corroborating that the bilateral collaboration is less likely to develop between cities with dissimilar economic and population growth. While the ILAs are not attributed to budget growth, city size, or proximityFootnote5. It is possible that the attributes at the city level rather than the dyad level would be more essential than the relative attributes at the dyad level. We replace all controls with either Cityx or Cityy in Appendix . It does not change our results of interest. Also, the lag of Direct Agent Networkx,y,t and Indirect Agent Networkx,y,t are used to check whether the mechanisms’ effect persists into the next year.

8. Discussion

This study offers a new theoretical perspective to examine the role of change agents, city leaders, and their networks in facilitating interlocal collaboration. Interlocal collaboration presents challenges to policy makers and public managers in the context of regional and local governance. We propose an Agent Network Collaboration (ANC) model that brings individual managers, as change agents, back into the study of the interlocal agreement. We argue that the leadership transfer networks serve as an important channel for interlocal collaboration. Specifically, we hypothesize that cities are more likely to engage in more collaborations through both the direct and indirect linkages created through the personnel flows between jurisdictions. The results from the dyadic panel ZINB provide strong and consistent support for our hypotheses. We identify that agent networks established by leadership transfer either directly or indirectly still do make a difference in the interlocal collaboration between cities.

Existing interlocal collaboration literature highlights the role of city leaders in promoting ILAs (Zeemering Citation2008; LeRoux and Pandey Citation2011; Kwon, Feiock, and Bae Citation2014), with some of these studies offering social network explanation for understanding how city leaders’ social network influences the ILAs (Thurmaier and Wood Citation2002; Thurmaier Citation2005). This study contributes directly to the latter lineage of ILA literature by stressing that city leaders’ career network built upon the personnel flow trajectory is as important as the professional and disciplinary network through regional associations and councils (Thurmaier and Wood Citation2002; LeRoux, Brandenburger, and Pandey Citation2010). Our focus on career path networks widens the extant social network focus by highlighting the importance of the city leaders’ intertemporal and spatial career connections. Specifically, cities where leaders worked before are more likely to triumph over other candidates to be chosen as interlocal collaborators.

This study sheds light on the exploration of key actors’ dynamic and non-static social networks. By differentiating the direct and indirect agent networks, we could clearly identify their stand-alone effect and significant impact on ILAs. To further test the robustness of the result, we run the interaction of Direct Agent Networkx,y,t, and Direct Agent Networkx,y,t in model A6 in Appendix . Their main effects stand, and the interaction is not significant, indicating that they do not depend upon one another. As shown in , the positive effect of Indirect Agent Networkx,z,t appears to be larger than the effect of Direct Agent Networkx,y,t, nevertheless the difference is found insignificant due to overlapping confidence intervals. Based on this, we could reach a quite profound implication that the indirect agent network is as mighty as the direct agent network in promoting ILAs. The indirect agent network constructed through a two-path connection does not necessarily represent a weaker tie or relay less information than the direct connection. Instead, the indirect agent network could refer to quite a strong tie, which tends to be part of the transitive triad (Granovetter Citation1973). The equivalent practical implication is that top leaders moving among different cities could create a denser trans-local career network, resulting in a tighter interlocal agreement network among various cities.

This study also extends current scholarship on environmental governance by emphasizing a range of other factors that impact the ILAs. Born out of the lineage of institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework, environmental governance decision and behaviour is well portrayed by a handful of factors. This study also involves some of them as part of the equation. The most salient factor is Prior ILA x,y/z,t, confirming that the collection action institution evolves upon prior institutional arrangement (Lubell et al. Citation2002). We also consider the impact of geographic distance on the formation of environmental collaboration, however, no empirical result supports this presupposition. It is in line with the existing mixed evidence of the effect of geographic proximity on ILAs (Lubell et al. Citation2002; Feiock, Steinacker, and Park Citation2009; Hawkins, Hu, and Feiock Citation2016). The geographic proximity might not automatically activate trust and enhance communication and interaction between neighbouring cities. Derived upon our findings, the setup of interlocal agreements entails a more solid bond that top managers deem reliable and trustworthy. It echoes Thurmaier’s (Citation2005) contention that administrators’ underlying social networks could be crucial for the ILAs. Our finding also substantiates that top leaders’ career network surpasses other socioeconomic and environmental factors to be the salient element in propelling ILAs, reaffirmed by the results in Appendix by changing the control variables.

Methodologically, this study proposes a novel method that allows scholars to embed the network data into a dyadic panel data structure and empirically test the dynamic impact of leadership transfer networks on the extent of interlocal collaboration activities. We acknowledge that this method is only one among several feasible approaches to studying the impact of career networks. More sophisticated network-based regression is suggested to answer some delicate questions related to social networks at the triadic and substructure level. But the above approaches resort to denser network data, which are hard to construct for longitudinal data in the ILA studies. Our employment of longitudinal dyadic zero inflated negative binomial models is one of the approaches that balance network embeddedness, time continuity, and interlocal connectivity. Future methodological development is needed to improve the methodological toolbox for governance scholars who are interested in the dynamics of network and collaborative governance, especially for solving the co-evolution of social networks and policymaking processes.

9. Conclusion

This study presents a theoretical contribution to the study of interlocal collaboration by advancing a network-based explanation for the interlocal collaboration processes. This article highlights the importance of the career paths of local managers and the resulting personnel flows in the study of collaborative governance. Even though the field of collaborative governance features extensive application of network analysis and network concepts, this study presents a unique perspective by examining the influence of the career trajectories of public managers. More distinctively, two career network mechanisms are introduced to reveal their influence on interlocal agreements. The results show that the indirect agent network works as well as the direct agent network, signifying the stability and consistency of the career network effect. In sum, the career path trajectory of top leaders functions as an effective network in directing and channelling involved city actors to the common policy arena, bringing promise to interlocal collaboration in solving environmental problems.

We acknowledge that the hypotheses of this study are more tailored to the Chinese context, where leadership mobility is heavily influenced by the central government, than to the rest of the world. Though we consider the endogeneity of leadership mobility weak to the formation of ILAs, we should be cognizant of its consequence in influencing leaders’ performance and further promotion or demotion. Echoing existing literature, we confirm that change agents play important roles in environmental governance through interlocal collaboration (Yi and Chen Citation2019). Considering the complexity of ILA, future studies are needed to investigate how the agent network influences other dimensions of ILA, such as engagement of agency, area of focus and scope of collaboration. Our focus on leadership mobility contributes to the horizontal mechanism underlying the formation of ILAs. To foster the development of the mechanisms, we advise future studies to factor in influences from the upper-level governments to examine their functions in ILA formation.

This study draws several practical implications for practitioners in local governments. The role of top leaders in setting up ILAs is decisive. To a large extent, either interlocal service agreements or interlocal environmental agreements count on the deliberation of top leaders. Social network has been substantiated to shape top leaders’ preference in selecting collaborators. By facilitating the communication and interaction among top leaders across jurisdictions, the prevalence of regional associations and councils in the United States is effective and conducive to the pursuit of ILAs. While in the non-Western context where these informal mechanisms lack, social networks could also be formulated under formal personnel flow arrangement. Another insight drawn from this study is for environmental practitioners. The resolution of the wicked environmental problems should vanquish the collective action dilemmas, which have long confronted the fragmented policy implementation actors. If local government aims at establishing environmental cooperation with certain governments with low willingness, top leaders could serve as brokers by taking advantage of their individual networks like career networks to reconcile both sides’ interests and goals. This strategy conforms to the Institutional Collection Action (ICA) framework by fully tapping bridging and bonding capital in promoting bilateral or multilateral cooperation (Feiock and Scholz Citation2010).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data is available in https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RP09MJ.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Some studies add different variables of interest in the negative binomial and logit stages of ZINB (Lubell et al. 2002; Smith 2009; Corredoira and Rosenkopf 2010). This literature provides more elaboration on how different covariates function differently in two stages from a theoretical point of view.

2. Vuong test could examine whether ZINB outperforms the negative binomial model (Vuong 1989). However, Wilson and Spies-Butcher (2016) questioned the widespread practice of the Vuong test to determine the superiority of the zero-inflated model when applied to non-nested model. Some scholars therefore suggest the usage of the conventional negative binomial model because the interpretation of ZINB could be challenging, and more robust tests are entailed to examine the appropriateness of ZINB (Allison 2012; Fisher, Hartwell, and Deng 2017). As a complementary test, two maximum likelihood model-based methods, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), would be used to check the model performance, with lower AIC/BIC indicating better model fit (Staub and Winkelmann 2013; Yusuf, Afolabi, and Agbaje 2018).

3. Lubell et al. (2002) raised the concern that the negative binomial model generates a more accurate predicted possibility of count in comparison to observed count, which might contradict the Vuong test. We therefore also resort to the robustness check from the negative binomial model.

4. Existing literature has an abundant discussion about the usage of AIC and BIC (Dalrymple, Hudson, and Ford 2003; Fortin and DeBlois 2007). The direct comparison between AIC and BIC is not appropriate because they have a different philosophical bases where the target model of AIC is “specific for the sample size at hand” (Burnham and Anderson 2004, 299), while BIC assumed the existence of a true model independent of n (Reschenhofer 1996).

5. To reveal the effect of geographic distance, the spatial model is more appropriate to take into account the spatial interdependency of the local actors.

References

- Allison, Paul. 2012. “Do We Really Need Zero-Inflated Models?” . https://statisticalhorizons.com/zero-inflated-models.

- Andrew, Simon A. 2009. “Recent Developments in the Study of Interjurisdictional Agreements: An Overview and Assessment.” State and Local Government Review 41 (2): 133–142. doi:10.1177/0160323X0904100208.

- Boucher, Jean-Philippe, Michel Denuit, and Montserrat Guillen. 2009. “Number of Accidents or Number of Claims? An Approach with Zero-Inflated Poisson Models for Panel Data.” The Journal of Risk and Insurance 76 (4): 821–846. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6975.2009.01321.x.

- Burnham, Kenneth P., and David R. Anderson. 2004. “Multimodel Inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in Model Selection.” Sociological Methods & Research 33 (2): 261–304. doi:10.1177/0049124104268644.

- Carlson, David. 2019. “Modeling-Related Processes with an Excess of Zeros.” Political Science Research and Methods 7 (4): 889–902. doi:10.1017/psrm.2018.25.

- Carr, Jered B., Kelly LeRoux, and Manoj Shrestha. 2009. “Institutional Ties, Transaction Costs, and External Service Production.” Urban Affairs Review 44 (3): 403–427. doi:10.1177/1078087408323939.

- Chen, Bin, Jie Ma, Richard Feiock, and Liming Suo. 2019. “Factors Influencing Participation in Bilateral Interprovincial Agreements: Evidence from China’s Pan Pearl River Delta.” Urban Affairs Review 55 107808741882500 (3): 923–949. doi:10.1177/1078087418825002.

- Chen, Bin, Liming Suo, and Jie Ma. 2015. “A Network Approach to Interprovincial Agreements: A Study of Pan Pearl River Delta in China.” State and Local Government Review 47 (3): 181–191. doi:10.1177/0160323X15610384.

- Chen, Yu-Che, and Kurt Thurmaier. 2009. “Interlocal Agreements as Collaborations: An Empirical Investigation of Impetuses, Norms, and Success.” The American Review of Public Administration 39 (5): 536–552. doi:10.1177/0275074008324566.

- Corredoira, Rafael A., and Lori Rosenkopf. 2010. “Should Auld Acquaintance Be Forgot? The Reverse Transfer of Knowledge Through Mobility Ties.” Strategic Management Journal 31 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1002/smj.803.

- Dalrymple, Michelle L., Irene L. Hudson, and Rodney P.K. Ford. 2003. “Finite Mixture, Zero-Inflated Poisson and Hurdle Models with Application to SIDS.” Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 41 (3–4): 491–504. doi:10.1016/S0167-9473(02)00187-1.

- Dorff, Cassy, and Michael D. Ward. 2013. “Networks, Dyads, and the Social Relations Model.” Political Science Research and Methods 1 (2): 159–178. doi:10.1017/psrm.2013.21.

- Feiock, Richard C. 2013. “The Institutional Collective Action Framework: Institutional Collective Action Framework.” Policy Studies Journal 41 (3): 397–425. doi:10.1111/psj.12023.

- Feiock, Richard C., In Won Lee, and Hyung Jun Park. 2012. “Administrators’ and Elected Officials’ Collaboration Networks: Selecting Partners to Reduce Risk in Economic Development.” Public Administration Review 72 (s1): S58–68. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02659.x.

- Feiock, Richard C., In Won Lee, Hyung Jun Park, and Keon Hyung Lee. 2010. “Collaboration Networks Among Local Elected Officials: Information, Commitment, and Risk Aversion.” Urban Affairs Review 46 (2): 241–262. doi:10.1177/1078087409360509.

- Feiock, Richard C., and Hyung Jun Park. 2005. “Bargaining, Networks and Institutional Collective Action in Local Economic Development.” In Annual Meeting of the American Society for Public Administration. Milwaukee, WI, USA.

- Feiock, Richard C., Scholz, John T., eds. 2010. “Self-Organizing Governance of Institutional Collective Action Dilemmas: An Overview .” In Self-Organising Federalism: Collaborative Mechanisms to Mitigate Institutional Collective Action Dilemmas, 3–32. Cambridge University Press.

- Feiock, Richard C., Annette Steinacker, and Hyung Jun Park. 2009. “Institutional Collective Action and Economic Development Joint Ventures.” Public Administration Review 69 (2): 256–270. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.01972.x.

- Fisher, William H., Stephanie W. Hartwell, and Xiaogang Deng. 2017. “Managing Inflation: On the Use and Potential Misuse of Zero-Inflated Count Regression Models.” Crime & Delinquency 63 (1): 77–87. doi:10.1177/0011128716679796.

- Fortin, Mathieu, and Josianne DeBlois. 2007. “Modeling Tree Recruitment with Zero-Inflated Models: The Example of Hardwood Stands in Southern Québec, Canada.” Forest Science 53 (4): 529–539.

- Fuhrmann, Matthew. 2009. “Taking a Walk on the Supply Side: The Determinants of Civilian Nuclear Cooperation.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 53 (2): 181–208. doi:10.1177/0022002708330288.

- Gilardi, Fabrizio, and Katharina Füglister. 2008. “Empirical Modeling of Policy Diffusion in Federal States: The Dyadic Approach.” Swiss Political Science Review 14 (3): 413–450. doi:10.1002/j.1662-6370.2008.tb00108.x.

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” The American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469.

- Harris, Mark N., and Xueyan Zhao. 2007. “A Zero-Inflated Ordered Probit Model, with an Application to Modelling Tobacco Consumption.” Journal of Econometrics 141 (2): 1073–1099. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.01.002.

- Haslam, S. Alexander, John C. Turner, Penelope J. Oakes, Craig McGairty, and Brett K. Hayes. 1992. “Context-Dependent Variation in Social Stereotyping 1: The Effects of Intergroup Relations as Mediated by Social Change and Frame of Reference.” European Journal of Social Psychology 22 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420220104.

- Hawkins, Christopher V., Qian Hu, and Richard C. Feiock. 2016. “Self‐organizing Governance of Local Economic Development: Informal Policy Networks and Regional Institutions.” Journal of Urban Affairs 38 (5): 643–660. doi:10.1111/juaf.12280.

- Huang, C., T. Chen, Y. Hongtao, X. Xiaolin, S. Chen, and W. Chen. 2017. “Collaborative Environmental Governance, Inter-Agency Cooperation and Local Water Sustainability in China.” Sustainability 9 (12): 2305. doi:10.3390/su9122305.

- Hu, Mei-Chen, Martina Pavlicova, and Edward V. Nunes. 2011. “Zero-Inflated and Hurdle Models of Count Data with Extra Zeros: Examples from an HIV-Risk Reduction Intervention Trial.” The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 37 (5): 367–375. doi:10.3109/00952990.2011.597280.

- Inman, Robert P., and Daniel L. Rubinfeld. 1997. “Rethinking Federalism.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 11 (4): 43–64. doi:10.1257/jep.11.4.43.

- Jiang, Junyan. 2018. “Making Bureaucracy Work: Patronage Networks, Performance Incentives, and Economic Development in China.” American Journal of Political Science 62 (4): 982–999. doi:10.1111/ajps.12394.

- Jing, Yijia, and E. S. Savas. 2009. “Managing Collaborative Service Delivery: Comparing China and the United States.” Public Administration Review 69: S101–7. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02096.x.

- King, Gary, and Langche Zeng. 2001a. “Explaining Rare Events in International Relations.” International Organization 55 (3): 693–715. doi:10.1162/00208180152507597.

- King, Gary, and Langche Zeng. 2001b. “Logistic Regression in Rare Events Data.” Political Analysis 9 (2): 137–163. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pan.a004868.

- Krause, Rachel M. 2011. “Policy Innovation, Intergovernmental Relations, and the Adoption of Climate Protection Initiatives by U.S. Cities.” Journal of Urban Affairs 33 (1): 45–60. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2010.00510.x.

- Krueger, Skip, and Michael McGuire. 2005. “A Transaction Costs Explanation of Interlocal Government Collaboration.” Working Group on Interlocal Services Cooperation, Paper 21.

- Kwon, Sung-Wook, and Richard C. Feiock. 2010. “Overcoming the Barriers to Cooperation: Intergovernmental Service Agreements.” Public Administration Review 70 (6): 876–884. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02219.x.

- Kwon, Sung-Wook, Richard C. Feiock, and Jungah Bae. 2014. “The Roles of Regional Organizations for Interlocal Resource Exchange: Complement or Substitute?” The American Review of Public Administration 44 (3): 339–357. doi:10.1177/0275074012465488.

- Lee, In Won, Richard C. Feiock, and Youngmi Lee. (2012).“Competitors and Cooperators: A Micro-Level Analysis of Regional Economic Development Collaboration Networks“ Public Administration Review, 72 (2): 253–262. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02501.x.

- LeRoux, Kelly, Paul W. Brandenburger, and Sanjay K. Pandey. 2010. “Interlocal Service Cooperation in US Cities: A Social Network Explanation.” Public Administration Review 70 (2): 268–278. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02133.x.

- LeRoux, Kelly, and Jered B. Carr. 2007. “Explaining Local Government Cooperation on Public Works: Evidence from Michigan.” Public Works Management & Policy 12 (1): 344–358. doi:10.1177/1087724X07302586.

- LeRoux, Kelly, and Sanjay K. Pandey. 2011. “City Managers, Career Incentives, and Municipal Service Decisions: The Effects of Managerial Progressive Ambition on Interlocal Service Delivery.” Public Administration Review 71 (4): 627–636. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02394.x.

- Liu, Yao, Jiannan Wu, Hongtao Yi, and Jing Wen. 2021. “Under What Conditions Do Governments Collaborate? A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Air Pollution Control in China.” Public Management Review 23 (11): 1664–1682. doi:10.1080/14719037.2021.1879915.

- Liu, Weixing, and Hongtao Yi. 2021. “Policy Diffusion Through Leadership Transfer Networks: Direct or Indirect Connections?” Governance. doi:10.1111/gove.12609.

- Li, Hongbin, and Li-An Zhou. 2005. “Political Turnover and Economic Performance: The Incentive Role of Personnel Control in China.” Journal of Public Economics 89 (9): 1743–1762. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.009.

- Lowery, David. 2000. “A Transactions Costs Model of Metropolitan Governance: Allocation versus Redistribution in Urban America.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10 (1): 49–78. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024266.

- Lubell, Mark, Mark Schneider, John T. Scholz, and Mihriye Mete. 2002. “Watershed Partnerships and the Emergence of Collective Action Institutions.” American Journal of Political Science 46 (1): 148. doi:10.2307/3088419.

- Morrow, James D., and Hyeran Jo. 2006. “Compliance with the Laws of War: Dataset and Coding Rules.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 23 (1): 91–113. doi:10.1080/07388940500503838.

- Ostrom, Vincent, and Elinor Ostrom. 1971. “Public Choice: A Different Approach to the Study of Public Administration.” Public Administration Review 31 (2): 203. doi:10.2307/974676.

- Reschenhofer, Erhard. 1996. “Prediction with Vague Prior Knowledge.” Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 25 (3): 601–608. doi:10.1080/03610929608831716.

- Robst, John, Solomon Polachek, and Yuan-Ching Chang. 2007. “Geographic Proximity, Trade, and International Conflict/Cooperation.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 24 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1080/07388940600837680.

- Shen, Ruowen, Richard C. Feiock, and Hongtao Yi. 2017. “China’s Local Government Innovations in Inter-Local Collaboration“ In Public Service Innovations in China, edited by Jing, Yijia, Osborne, Stephen P., 25–41. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Shrestha, Manoj K., and Richard C. Feiock. 2009. “Governing U.S. Metropolitan Areas: Self-Organizing and Multiplex Service Networks.” American Politics Research 37 (5): 801–823. doi:10.1177/1532673X09337466.

- Shrestha, Manoj K., and Richard C. Feiock. 2013. “Institutional Collective Action Dilemmas in Service Delivery: Exchange Risks and Contracting Networks Among Local Governments.” In PMRC Conference, Madison, WI.

- Smith, Craig R. 2009. “Institutional Determinants of Collaboration: An Empirical Study of County Open-Space Protection.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum037.

- Staub, Kevin E., and Rainer Winkelmann. 2013. “Consistent Estimation of Zero-Inflated Count Models.” Health Economics 22 (6): 673–686. doi:10.1002/hec.2844.

- Su, Fubing, Ran Tao, Lu Xi, and Ming Li. 2012. “Local Officials’ Incentives and China’s Economic Growth: Tournament Thesis Reexamined and Alternative Explanatory Framework.” China & World Economy 20 (4): 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1749-124X.2012.01292.x.

- Tang, Xiao, Zhengwen Liu, and Hongtao Yi. 2016. “Mandatory Targets and Environmental Performance: An Analysis Based on Regression Discontinuity Design.” Sustainability 8 (9): 931. doi:10.3390/su8090931.

- Teodoro, Manuel P. 2009. “Bureaucratic Job Mobility and the Diffusion of Innovations.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (1): 175–189. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00364.x.

- Thurmaier, Kurt. 2005. “Elements of Successful Interlocal Agreements: An Iowa Case Study.” http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/interlocal_coop/2.

- Thurmaier, Kurt, and Curtis Wood. 2002. “Interlocal Agreements as Overlapping Social Networks: Picket-Fence Regionalism in Metropolitan Kansas City.” Public Administration Review 62 (5): 585–598. doi:10.1111/1540-6210.00239.

- Tir, Jaroslav, and John T. Ackerman. 2009. “Politics of Formalized River Cooperation.” Journal of Peace Research 46 (5): 623–640. doi:10.1177/0022343309336800.

- Vuong, Quang H. 1989. “Likelihood Ratio Tests for Model Selection and Non-Nested Hypotheses.” Econometrica 57 (2): 307. doi:10.2307/1912557.

- Wang, Xuechun, and Ziteng Fan. 2022. “Understanding Interlocal Collaboration for Service Delivery for Migrant Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Guangdong, China.” Public Management Review, no. August: 1–21. doi:10.1080/14719037.2022.2116095.

- Wang, Feng, and Haitao Yin. 2012. “A New Form of Governance or the Reunion of the Government and Business Sector? A Case Analysis of the Collaborative Natural Disaster Insurance System in the Zhejiang Province of China.” International Public Management Journal 15 (4): 26. doi:10.1080/10967494.2012.761063.

- Watson, Douglas J., and Wendy L. Hassett. 2004. “Career Paths of City Managers in America’s Largest Council-Manager Cities.” Public Administration Review 64 (2): 192–199. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00360.x.

- Wilson, Shaun, and Ben Spies-Butcher. 2016. “After New Labour: Political and Policy Consequences of Welfare State Reforms in the United Kingdom and Australia.” Policy Studies 37 (5): 408–425. doi:10.1080/01442872.2016.1188911.

- Xu, Chenggang. 2011. “The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development.” Journal of Economic Literature 49 (4): 1076–1151. doi:10.1257/jel.49.4.1076.

- Yi, Hongtao, Frances S. Berry, and Wenna Chen. 2018. “Management Innovation and Policy Diffusion Through Leadership Transfer Networks: An Agent Network Diffusion Model.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 28 (4): 457–474. doi:10.1093/jopart/muy031.

- Yi, Hongtao, and Wenna Chen. 2019. “Portable Innovation, Policy Wormholes, and Innovation Diffusion.” Public Administration Review 79 (5): 737–748. doi:10.1111/puar.13090.

- Yi, Hongtao, and Yuan Liu. 2015. “Green Economy in China: Regional Variations and Policy Drivers.” Global Environmental Change 31: 11–19. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.12.001.

- Yi, Hongtao, Liming Suo, Ruowen Shen, Jiasheng Zhang, Anu Ramaswami, and Richard C. Feiock. 2018. “Regional Governance and Institutional Collective Action for Environmental Sustainability.” Public Administration Review 78 (4): 556–566. doi:10.1111/puar.12799.

- Yusuf, Oyindamola B., Rotimi F. Afolabi, and Ayoola S. Agbaje. 2018. “Modelling Excess Zeros in Count Data with Application to Antenatal Care Utilisation.” International Journal of Statistics and Probability 7 (3): 22. doi:10.5539/ijsp.v7n3p22.

- Zeemering, Eric S. 2008. “Governing Interlocal Cooperation: City Council Interests and the Implications for Public Management.” Public Administration Review 68 (4): 731–741. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.00911.x.

Appendix

Table A1. Zero-inflated negative binomial models for ILA formation.