?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Corporatization has gained scholarly attention in recent years, yet little is known regarding why many corporations are eventually terminated, and what happens to their form and functions thereafter. Reinternalizing services is one option local governments may pursue. This paper focuses on the impact of tensions (systemic contradictions) on this final resolution reached: Do local governments choose or refuse reinternalization? Conducting machine learning, I predict termination outcomes based on an original dataset of 244 ceased English and German companies (2010–2020). The results show that macrosystemic tensions are more relevant for resourcing decisions and reinternalization is less likely to be caused by formal ownership issues.

Introduction

When a decision to terminate a local government-owned company (LGC) is made there are two main questions: Why is the decision taken and what alternatives, such as privatization, dissolution, mergers, transfer, or reinternalization are sought? I will examine reinternalization, as the most radical movement towards in-house service provision, and will demonstrate how mediating variables (tensions) impact whether a terminated company’s function is reinternalized or not.

Local governments have long created and operated single- or multi-purpose companies, organized under private law through sole public or various combinations of public and private participation, to perform services ranging from urban-infrastructure planning and social-services provision to back-office functions. The eligibility and effectiveness of such corporatization – as a viable means for public-service provision – remains a subject of debate among scholars and practitioners today (Andrews, Clifton, and Ferry Citation2022; Bel et al. Citation2022; Voorn, van Genugten, and van Thiel Citation2017). Some regard corporatization as a promising avenue towards lean and innovative administration (Cooper et al. Citation2021; Tremml Citation2020), while others have advocated a more democratic sense of public ownership (Berge and Torsteinsen Citation2022; Pesch Citation2008). While enthusiasm prevails concerning this system’s efficiency (Torsteinsen Citation2019), international experience features indicators leading to company closures. Reasons for these reversals reported so far centre around rampant policy fragmentation and opacity or loss of coordination (Bouckaert, Peters, and Verhoest Citation2010), closely related to poor performance and inefficiencies, concerns about democratic accountability or micropolitics, and ‘bureaushaping’ (Andrews, Clifton, and Ferry Citation2022; Camões and Rodrigues Citation2021; Gradus and Budding Citation2020; Lamothe, Lamothe, and Feiock Citation2008; Schröter, Röber, and Röber Citation2019). However, most studies remain theoretical, and evidence is scant. Exceptions include Andrews (Citation2020), Camões and Rodrigues (Citation2021), and Gradus and Budding (Citation2020). Andrews (Citation2020) examines the longitudinal effects of publicness on the dissolution of English local companies (2010–2016), underscoring the widely neglected relevance of control rights in empirical corporatization research. Camões and Rodrigues (Citation2021) find that financial pressures took precedence over political ones in Portuguese municipalities’ decision to dissolve their companies (1998–2012). Gradus and Budding (Citation2020) show that left-wing political affiliation led Dutch municipalities to switch to full in-house provision (1999–2014) and highlight the need to further investigate the impact of service characteristics on this process.

While these serve as valid explanations for company ‘break-ups’, more research is required, as our understanding of these local governance reversal decisions remains incomplete (Andrews, Clifton, and Ferry Citation2022). The organizational survival literature reveals that instability in organizations is often attributable to underlying tensions, or so-called ‘systemic contradictions’ (Benson Citation1977; Jarzabkowski, Lê, and van de Ven Citation2013). Such tensions arise, for instance, because actors must meet the conflicting demands of heterogeneous stakeholders and safeguard (political) legitimacy whilst maximizing cost efficiency (Camões and Rodrigues Citation2021; Corbett and Howard Citation2017; Leixnering, Meyer, and Polzer Citation2021; MacCarthaigh Citation2014) and can – if improperly navigated – lead to the ‘death’ of organizations (Das and Teng Citation2000). Tensions and their directional potential are well documented in the context of private sector inter-organizational relations (Vangen Citation2017b). However, they have not yet been systematically linked to LGCs or their closures, where accountability, legitimacy, and ownership issues or ‘ambiguities of control’ (Aars and Ringkjøb Citation2011, 843) can become prevalent (Andrews Citation2020; Collin et al. Citation2009), with even less empirically grounded insights into subsequent control claims. This is, however, important to consider, as different tensions may cause different kinds of termination outcomes with critical institutional implications, moving away from or closer to the public sector realm. Appreciating tensions is crucial for reflective management practice and can prevent undesired or premature termination (Das and Teng Citation2000).

Taking up this debate in the organizational literature for the corporatization context, I focus on reinternalization (of tasks or personnel), understood as the highest degree of public in-house provision and the least explored local reform. What impact do tensions inherent in LGCs have on whether a local government chooses or refuses to reinternalize formerly corporatized functions?

Reviewing the corporatization and organizational survival literature, I identify different types of tensions and develop an argument as to why tensions have an impact on the final typology of resolution reached when termination is considered. While Camões and Rodrigues find that reverse corporatization is ‘the politics of bad times’Footnote1 (2020, 7), I argue it is the politics of tense times. I test this using machine learning (ML) on 244 LGCs in England and Germany that ceased operations between 2010 and 2020.

Private law public companies were selected as the most prevalent and most understudied form of public-service provision outside core administration in both target countries (e.g. for Germany: Rackwitz and Raffer Citationwork in progress; for England: Andrews et al. Citation2019). Additionally, tensions will likely manifest more drastically in environments where public and private logics collide.

By termination, I refer to the specific point in time when a company is deleted from the commercial register or liquidation is initiated. This is done for analytical clarity in the effort to address the widely-voiced challenge of determining termination (Adam et al. Citation2007; Freeman, Carroll, and Hannan Citation1983). Data were collected through automated matching across different databases, supplemented by documentary analysis and telephone inquiries with local officials. Concentrating on England and Germany primarily served to ensure variance in data to assess the universality of claims and test them across conditions, but also afforded visualization of the level of variation in termination traits across countries with widely different reform trajectories and notions of market and state.

This work contributes to the research in four main ways. First, it provides insights into the termination dynamics of municipal corporatization and offers an empirically grounded classification of ‘break-up’ variants.

Second, it explores the directional potential of ‘systemic contradictions’ or tensions (Benson Citation1977; Jarzabkowski, Lê, and van de Ven Citation2013) that public corporations can experience, affecting local government’s resourcing decisions. In doing so, I ‘borrow’ prominent arguments from the literature on private sector firms and examine whether they hold when applied to public organizing in the private law domain.

Third, it illuminates the largely untapped methodological potential of ML (specifically, random forest) for understanding organizational reform dynamics in local contexts. From this, I suggest a pattern linking institutional tensions to responses, thereby adding to future research on the causal mechanisms underlying organizational mortality.

Finally, the claims are grounded in an international perspective, thereby addressing a gap in systematic cross-national evidence on organizational mortality and restructuring (Adam et al. Citation2007; Lægreid and Verhoest Citation2010) and corporatization research (Andrews Citation2020; Andrews, Clifton, and Ferry Citation2022; Torsteinsen Citation2019). Including two Western cultures supplements the predominant focus of comparative tension studies on Eastern versus Western cultures (cf. Keller, Loewenstein, and Yan Citation2017; Schrage and Rasche Citation2021).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the theoretical background, noting that predictors of organizational mortality often originate from latent or salient tensions that may destabilize organizations over time, eventually leading to termination. To account for the unique composition of LGCs, I focus on factors ubiquitous in the organizational survival literature and complement factors frequently discussed in the corporatization literature around service characteristics and ownership, also addressing calls by Andrews (Citation2020) and Camões and Rodrigues (Citation2021). I then develop an argument for why high tensions make local governments more likely to opt for reinternalization. Section 3, presents my methodological approach; Section 4, the results, which Section 5 discusses; Section 6, concludes.

Theoretical background

A tension lens on public-company terminations

Tension refers to elements of an organization that appear logical in isolation but oppositional in conjunction (Lewis Citation2000; Smith and Lewis Citation2011). The context of multi-actor arrangements is inherently tense (Ashforth and Reingen Citation2014; Ospina and Saz-Carranza Citation2010; Provan and Kenis Citation2008; Vangen Citation2017b). Corporatized private law entities are a classic example, characterized by a pluralistic logic (Jay Citation2013; Ospina and Foldy Citation2015; Skelcher and Smith Citation2015) and, thus, ‘persistent contradictions between interdependent elements’ (Schad et al. Citation2016, 6). This can result in competing demands, such as hierarchy versus heterarchy, short- versus long-term goal-setting, control versus autonomy, innovation versus replication, and rigidity versus flexibility (Leixnering, Meyer, and Polzer Citation2021; Schad et al. Citation2016; Raza‐ullah, Bengtsson, and Kock Citation2014), and ‘failure can derive from not getting the balance correct’ (Torsteinsen Citation2019, 5). Corroborating this, Das and Teng (Citation2000) and Park and Ungson (Citation1997) show that rivalry between forces is a key indicator of alliance dissolution. In a similar vein, Cui, Calantone, and Griffith (Citation2011) report goal incongruence among partners as the main predictor of their demise. High tensions, therefore, imply a pronounced dysbalance between logic (Das and Teng Citation2002). Tensions are not per se negative to organizational survival and can create generative forces (Cloutier and Langley Citation2017; Gulati and Puranam Citation2009; Jarzabkowski and Lê Citation2017). However, as Skelcher and Smith (Citation2015) reiterate, if not properly navigated, dysfunction occurs, increasing the desire of those involved to block one logic and sync again (Xiao et al. Citation2019; Zimbardo and Leippe Citation1991).

Premised on this understanding, this paper identifies and traces a collection of tension-proxying factors from the literature on private and public organizations, to determine how far these factors are characteristic of reinternalization in the context of company termination.

A company’s national context towards market and state

The first tension concerns diverging starting points for different national public sectors and collective notions of market and state that may conflict with the idea of rampant private law. Diverging starting points develop based on historical backgrounds, state structures and legacies, administrative traditions, and reform trajectories (Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017). While public companies in a nation do not necessarily share the same paradigm, national culture can inform ‘habitual ways’ (Vangen Citation2017a, 306) and how they address organizational challenges (Dyson Citation1980; Yesilkagit and Christensen Citation2010). Schrage and Rasche (Citation2021) demonstrate that Chinese and German businesses handled tensions differently when confronted with the same paradox. Schröter points to the British ‘entrepreneurial’ (Citation2019, 200) mindset that affects how actors understand, justify, and legitimate local reform strategies. Following this logic, public companies in countries that have traditionally taken a relatively market-oriented stance can be expected to face less tension when operating under private law, making termination less likely than in countries where the private sector is viewed with scepticism.

A company’s lifespan

Population ecologists highlight the relevance of age and size for organizational survival (cf. Abatecola, Cafferata, and Poggesi Citation2012; Freeman, Carroll, and Hannan Citation1983). Both these factors harbour fundamental tensions that can facilitate hypothesizing of companies’ breakdown types. Young companies strive to legitimize and position themselves in their fields by adhering to their normative contexts (Scherer, Palazzo, and Seidl Citation2013; Smith and Lewis Citation2011; Sullivan et al. Citation2013). This ‘liability of newness’ requires great capacity to build structures that can withstand legitimacy scrutiny (Singh, House, and Tucker Citation1986; Stinchcombe Citation1965). Alajoutsijärvi, Juusola, and Siltaoja (Citation2015) and Sonpar, Pazzaglia, and Kornijenko (Citation2010) demonstrate that new-borns’ low reputational capital and less-established accountability structures make them more vulnerable to the formative influence of ambiguous logic and thus more prone to termination.

A company’s size

While most empirical studies support that size plays a decisive role in an organization’s survival (Li, Zhang, and Shi Citation2020), more recent research evinces small or no effects (Corbett and Howard Citation2017; Boin, Kuipers, and Steenbergen Citation2010). The rationale here is closely related to a company’s lifespan: Larger companies may be more stable profiting from well-established structures and cost benefits, but they can be entrenched and cumbersome. Their smaller counterparts may be more adaptive to volatile environments but torn between multiple demands. This ‘liability of smallness’ makes them more prone to termination (Aldrich and Auster Citation1986; Boin, Kuipers, and Steenbergen Citation2010).

A company’s service type

Closely related is the tension inherent in certain service types. Lamothe, Lamothe, and Feiock find that if the delivery mode and service type are a ‘mismatch’ (Citation2008, 31), termination is the most likely outcome, suggesting a potential underlying tension that prompts reconsideration of the service delivery decision. For LGCs, this can be explained by tenants of transaction cost theory, according to which companies with low commerciality or ambiguities regarding service quality and quantity, such as those with social or administrative functions, are more likely to encounter a systemic conflict of demands when operating in private law environments (Brown and Potoski Citation2005). Andrews (Citation2020) argues that companies providing human services, such as social housing or benefits, may face a broader range of competing accountability tensions, meandering between profit maximization and best value outcome, subjecting them to greater termination risk.

A company’s number of owners

Tensions are also likely to rise with increasing shareholder numbers, an issue closely related to size. Although wide-scale inclusion can fertilize corporate dynamics by pooling diverse knowledge, resources, and competencies (Cappellaro, Tracey, and Greenwood Citation2020), it can also foster increased demand for coordination and control (Henry, Rasche, and Moellering Citation2022; Vangen Citation2017b). As Elston, Rackwitz, and Bel (Citationforthcoming) set out, the number of veto players and the potential heterogeneity of their preferences grows, causing increases in debating, bargaining, and decision time and reductions in flexibility, resulting in tensions and potentially a breakdown.

A company’s ownership distribution

Additionally, distribution of ownership and, thus, the level of ‘power over [own gain]’ (Huxham and Vangen Citation2005, 175) becomes critical to how companies evolve. The rationale here is that asymmetrical control by one partner constrains the other’s decision-making authority and ability to achieve personal or organizational goals (Purdy Citation2012). Therefore, a partner may seek to compensate for control and influence deficits through opportunistic behaviour, again undermining the stronger partner’s discretion and overall synergy (Makhija and Ganesh Citation1997). By contrast, more evenly distributed modes can provide mutual cost-sharing benefits and encourage strategic exchange, which alleviates tensions and, as Kwon, Pardo, and Burke (Citation2006) and Talay and Akdeniz (Citation2009) show, averts termination.

A company’s public ownership

If the private sector’s share is disproportionate to the public sector’s share, tensions between logic or actors’ commitment can be exacerbated, impacting the collaborative agenda (Andrews, Esteve, and Ysa Citation2015; Huxham and Vangen Citation2005). Da Cruz and Marques find evidence for high degrees of cognitive dissonance in mixed companies, which is ‘accentuated in ownership dispersion’ (2012, 5) that favours the private shareholder’s commerciality over public interest – circumstances prone to tension. Similarly, Battilana and Dorado (Citation2010) and Tracey, Phillips, and Jarvis (Citation2011) demonstrate that partners torn between market and social-mission logics perish when they prioritize one over the other.

These tensions may be mutually constitutive and recursive and, thus, coexisting and coevolving (Jarzabkowski, Lê, and van de Ven Citation2013; Lüscher and Lewis Citation2008). For example, low-age, mixed-owned companies with public and private shares may encounter greater tensions than older companies with full public ownership, as the former must withstand simultaneous legitimacy tests from competing normative contexts.

The following section now moves away from the predictor variables of ‘tensions’ to the response variable ‘termination outcome’ to develop an argument for why high tensions lead local governments to choose reinternalization.

Organizational mortality and termination outcomes

While studies on organizational survival are manifold, significantly fewer have considered the final stage of organizations’ existence (MacCarthaigh Citation2014; Zeemering Citation2018). Moreover, the few existing empirical studies on organizational mortality have regarded termination as a binary feature, neglecting to consider subtle differences in termination outcomes. The literature disagrees on when, or if, organizational ‘death’ can occur (Askim et al. Citation2020; Kaufman Citation1976). Broadly speaking, an organization may persist in various configurations after a company’s official breakdown. Das and Teng (Citation2000) frame firm strategic alliances’ termination options as either merger/acquisitions or dissolutions. Hannan and Freeman (Citation1989) identify four generic kinds of mortality – disbanding, absorption, merger, and radical change of form – while Adam et al. (Citation2007, 233) note that ‘a detailed description of how the changes were observed and classified’ is not provided. MacCarthaigh (Citation2014) echoes this in the context of public sector organizations by distinguishing between death, absorption, merger, and replacement. Transferred to the local government corporatization context, these frameworks do not provide a useful concept for reinternalization.

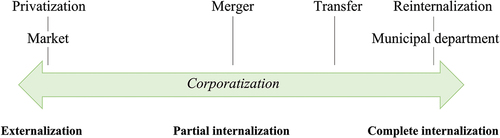

Thus, I adapt the distinction to identify characteristic organizational features, or packages of features, associated with particular types of LGC termination that I derived from the dataset. These types can be placed on a continuum ranging from municipal externalization to partial and complete internalization (Lamothe, Lamothe, and Feiock Citation2008), starting with privatization, moving through a merger with another company and transfer to another semi-autonomous legal form or public law company, and ending with this study’s focus: reinternalization, as the most internalized mode of public service delivery (). ‘Full dissolution’ is not included in , as the definitive discontinuation of a company with all its constituents means no ‘post functional lineage’ (MacCarthaigh Citation2014, 1027) remains.

Figure 1. Range of follow-up governance structures for terminated public-service companies derived from the dataset and informed by Hannan and Freeman (Citation1989), Lamothe, Lamothe, and Feiock (Citation2008), and MacCarthaigh (Citation2014).

Reinternalization is pursued for multiple reasons. This can be for a lack of delivery alternatives but is often attributed to public control claims (Lamothe, Lamothe, and Feiock Citation2008) and, as I argue, the need for synchronization. Switching to complete internalization is said, for instance, to have the potential to streamline service provision due to decompartmentalization and defragmentation (Fiss and Zajac Citation2004). While it does not necessarily reduce costs, it allows local governments to use internal control mechanisms consistent with their premises (Williamson Citation1981). Finding evidence on reinternalization’s efficiency and effectiveness is beyond this research, but this line of reasoning helps to set forth my argument.

I hypothesize that reinternalization becomes a viable option for a local government that is assumed to interpret and filter events through the public sector environment’s deeply ingrained norms and values (Christensen, Lægreid, and Røvik Citation2020). When rationally or irrationally motivated, it sees its logic threatened by high tensions in its corporations, which leads us to my hypothesis:

Hypothesis: When tensions are high in LGCs, the local government will opt for reinternalization when deciding to terminate.

Data and method

To scrutinize this hypothesis, I look at the formerly corporatized local government entity as the unit of analysis. I have analysed 86 English and 158 German companies over 10 years, which provides us with important information to analyse longitudinal change. First, terminated companies were identified by automated matching of different databases in R, which allowed the accuracy of the data to be confirmed/double-checked and missing information in one database to be filled from by the other: purchased statistical offices’ for Germany, Bureau Van Dijk’s (Citation2022) Fame for England, and manually collected data and North Data’s (Citation2022) for both countries. Subsequently, the final data set was cleaned for companies for which some variables relevant for robust hypothesis testing could not be identified.

Case setting

To increase the results’ validity and reliability, I aimed to ensure that the sample had sufficient diversity regarding the companies’ national starting points and reform trajectory during the selection of cases’ national context. Therefore, this study follows a ‘most different system design’ (MDSD) (Przeworski and Teune Citation1970), choosing companies embedded in countries with different institutional contexts, administrative traditions, and ‘swings of the pendulum’: England and Germany.

Although standardization pressures at the EU (cf. single market rules) and national levels and recent local government reforms affecting the two countries have somewhat eroded their diversity (Cumbers and Becker Citation2018; Rosell and Saz-Carranza Citation2020; Wollmann and Marcou Citation2010), fundamental differences remain. England is chiefly associated with the Anglo-SaxonFootnote2 model of public interest culture, pragmatism, and a tendency towards more radical reform compared to the Weberian Rechtsstaat model, based on legality, probity, and predictability of outcomes, characteristic of Germany (Andresani and Ferlie Citation2006; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017).

As such, Germany has been classified as a late and incoherent adopter of reform, producing its own coordinated, ‘variegated form of neoliberalism’ (Cumbers and Becker Citation2018, 6; John, Citation2000), whereas England is considered a market-oriented pioneer (Cooper et al. Citation2021), such that social dialogue with the private sector domain is not as broadly accepted in Germany as in England (Schröter Citation2019). While Germany is a federal state nested within dense multi-scalar governance with a tradition of strong local self-government, England has a comparatively highly centralized political-administrative system in which national government interventions directly impact local public-management strategy, limiting local agency and capacity (Bulkeley and Kern Citation2006; Wollmann and Marcou Citation2010).

In both countries, arm’s length companies have long been viable vehicles for local service provision. Over the last decade (2010–16), in both countries, the number of LGCs has risen: in England’s major local governments by about 23% (Andrews et al. Citation2019), and in Germany by about 12%Footnote3 (German Federal Statistical Office Citation2021); however, we have little insight into their termination dynamics.

Instead, debates about ‘reclaiming public services’ (Kishimoto and Petitijean Citation2017) have recently centred on remunicipalization, that is, restoring formerly privatized services to local government ownership, mostly after amassing negative experiences with private contractors (Becker, Beveridge, and Naumann Citation2015; Warner Citation2008). This strategic reversal may explain the rare incidence of privatization in the data as a form of local governance ex-post corporatization. However, while evidence suggests a move away from privatization into public ownership, we know little about whether this fuels corporatization or involves complete internalization (Albalate, Bel, and Reeves Citation2022; Voorn, van Genugten, and van Thiel Citation2021). Some reports speak of an ‘insourcing revolution’ in England (APSE Citation2019; Labour Citation2020), while German reference to this issue is effectively non-existent.

Thus, while this study aimed to apply and test a theoretical framework through ML using a highly versatile dataset, entering country into the model further adds to the debate by determining whether national differences mirrored in state structure and administrative reform paths proxying tensions uniquely impact reinternalization decisions.

English data

The initial data for the English set was made available by a research team from the Universities of Birmingham, Cardiff, and DurhamFootnote4 (Andrews et al. Citation2019; Andrews Citation2020; Ferry et al. Citation2018). These primary data included all companies at least partly owned by single- or upper-tier local authorities in England from 2009 to 2017. Single-tier local authorities operate mostly in urban areas, while upper-tier local authorities operate in the two-tier local government system that covers rural areas.

The team scrutinized each authority’s annual statements of account to identify companies that local authorities controlled or had an interest in, which revealed almost 700 separate local-authority companies. To construct a company-level dataset, each entity’s registered company number was searched via Bureau Van Dijk’s Fame financial database providing major British company information (Bureau Van Dijk Citation2022). Then, the registered numbers were imported into the Fame database to extract the company information needed for analysis. This revealed that some companies did not have complete accounting data. After this data cleaning, three legal formats with private law elements were represented in the sample that formed the basis for this study’s dataset: companies limited by shares, companies limited by guarantee, and limited liability partnerships.

German data

Annual data on all German municipally-owned companies for 2009–2020 were purchased from the Federal National Statistical Office. As these data only provided company names, states, and service types, additional desk research on archival data from council websites, primarily annual accounts, formal requests for information, and news articles, was needed to determine their legal status and whether entities’ disappearance indicated the end of a project, either due to early termination, or conclusion or that they had been renamed/merged. Information on companies with the legal form of a limited liability company (Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung) was collected, as this is the most prevalent German form under private law.

Final dataset

To obtain additional information regarding termination types and make the data more robust, the cross-country dataset was matched with North Data’s (Citation2022) database using R. North Data links various business registers in England and Germany to provide a wide range of company information. Additional missing variables were collected manually via desk research and 25 telephone calls to acquire information from local officials. For the German context, this approach to gathering information on local corporatization is more reliable than those applied in previous studies, which relied on surveys with relatively low response rates or voluntarily filled databases. For the English context, this cross-linkage helped identify English companies within the set terminated from 2017 to 2020. Therefore, the English 2017–2020 data in this analysis refer only to companies that were terminated after 2017, not those founded and terminated from 2017 to 2020.

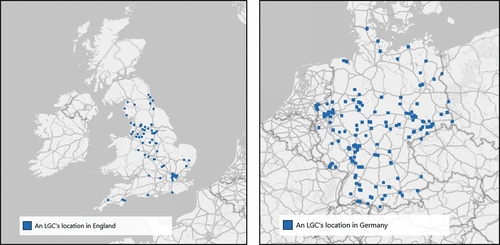

This resulted in a final dataset of 86 English and 158 German LGCs. Their large spatial dispersion in each country additionally controls for possible effects of local institutional homogeneity and ensures data variance within and across countries (see APPENDIX, for the sample’s location in England and Germany).

Predictor variables (features)

The seven outlined tension-proxying factors potentially relevant to company mortality were operationalized as follows (see APPENDIX, for the definitions and descriptive characteristics of these predicting [tensions] and responding [outcomes] variables). Tensions related to a company’s national context, lifespan, and size were measured using the corporate variables country, lifespan, and size. The categorical variable country, used to account for national cultural and political tradition, took DE and EN for companies registered in Germany and England, respectively. Company lifespan reflected the number of years between the dates of formal incorporation and official liquidation (as recorded in the national commercial registers). The start of liquidation, rather than the deletion of the company, was chosen to exclude the less representative, atypical phase of liquidation (selling assets, paying creditors, etc.).

Several options for operationalizing a company’s size are proposed in the literature. I opted for the most accessible – but no less informative – approach. For England, using the Birmingham, Cardiff, and Durham team’s dataset, company size was measured through a dichotomous variable coded ‘1’ for companies from the top quartile of the sample regarding sales (according to the Fame database) and ‘0’ otherwise. This accounted for missing accounting information for the smallest companies in which municipalities have a stake and the non-normal distribution of turnover figures for companies with complete information (cf. Andrews et al. Citation2019). Similarly, for Germany, size was captured by entering ‘1’ if the arithmetic mean of a company’s balance sheet for the three years prior to liquidation fell within the top quartile of the sample and ‘0’ otherwise. The three-year period was chosen to allow sufficient dispersion and indicate the potential well-being of the companies before their demise.

Another categorical variable was used for service, covering eight public service types: administration, development, education, environment (including energy and water), housing, leisure, social care, and transport (Andrews Citation2020).

For number of owners, a continuous variable was used that counted companies’ partners. Public ownership was represented by the percentage of company shares held by public organizations compared to private shares. Finally, one distributional measure, the normed Gini coefficient, illustrated the distribution of (corporate) ownership among shareholders:

where is the corrected Gini coefficient,

is the number of samples,

is the relative share, and

is the cumulated relative characteristics. The Gini coefficient is normed as a number between 0 and 1, where 1 represents absolute unequal distribution (one person owns everything, all others nothing) and 0 represents absolute equal distribution (all persons own the same assets).

Response variables (classes)

The response variable termination outcome comprised two classes, respectively representing local governments’ responses to tensions: reinternalization into the core administration (reinternalization) and no reinternalization (noreinternalization). For analytical clarity and model accuracy, all other subclasses derived from the initial categorization of the information gathered on each company were subsumed under noreinternalization and, through this, the possible consequences of company cessation that did not involve reinternalization were summarized; that is, complete dissolution, formal privatization, merger with another company of the same legal form, or transfer to an alternative jurisdiction. These classes were not always mutually exclusive; in some cases, parts of a company were, for example, reinternalized while smaller parts were merged with other companies. In such cases, only the predominant category (reinternalization) was selected to represent the service’s future delivery method.

Random forest

With my two pre-set groups of termination outcomes, a decision-tree-based approach for classification was applied (e.g. Breiman Citation2001). Decision-tree methods are supervised ML algorithms that have advantages over traditional linear regression, as they can map non-linear relationships in complex datasets. Moreover, they apply to a combination of categorical and numerical data. While this method has been well established in various fields (see e.g. Grimmer, Roberts, and Stewart Citation2021; Reades, De Souza, and Hubbard Citation2019; Yin, Cao, and Sun Citation2020), its potential for organization and public administration studies has only recently been recognized (Anastasopoulos and Whitford Citation2019).

The random-forests approach, useful for relatively small datasets, was applied, as it leverages the power of multiple decision trees to predict a final aggregated output. The random selection makes the method robust against overfitting. To prepare for the computational process in the R environment (‘randomForest’ package, Liaw and Wiener Citation2002), a command was established that shuffled the data to ensure each termination outcome was represented in each sample.

A critical component of most ML approaches is splitting the data for training and testing purposes. Following the most common recommendation, 70% was used for training and 30% for testing (Breiman et al. Citation2017). To manage the class imbalance of the dataset (reinternalization: 29.9%, no reinternalization: 70.1%; see APPENDIX, ), a synthetic minority up-sampling technique was deployed. To tune the resulting model to its best possible accuracy, loops were installed to determine the ideal hyperparameter. The hyperparameter ntree (number of trees grown) was systematically tested with values of 10–500, with no observed effect on training and test accuracy; consequently, it was set to 500. The parameter mtry (number of variables randomly sampled as candidates at each split) was automatically optimized for ntree = 500 (Liaw and Wiener Citation2002). Through this recursive portioning, it was possible to classify observations (predictors) and predict qualitative outcomes (responses), yielding an accuracy of 0.98 for the training set and 0.77 for the testing regarding the percentage of correct predictions (further explanation of the technicalities can be found in the APPENDIX, ).

Results

Relative importance

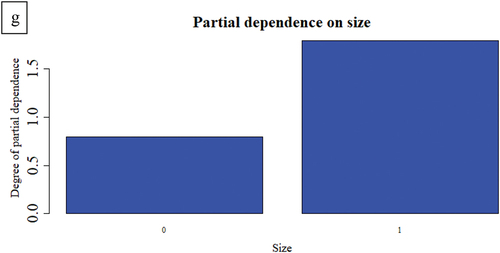

First, the individual predictors’ relative importance for predicting whether a local government will, in the event of company termination, respond by returning the company’s function to core administration were considered (see ). This showed that service type (58%), lifespan (52%), and country (31%) were the largest contributors to the model. Number of owners (27%), share of public ownership (26%), and ownership distribution (27%) were less relevant, with size (22%) having the smallest influence overall.

Table 1. Relative importance of independent variables for predicting termination outcomes.

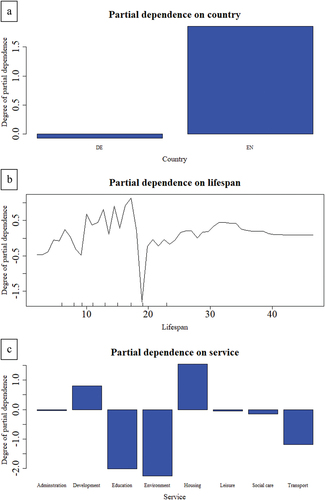

Partial dependence

illustrate the dependence between the target response and the set of input features, marginalizing the values of all other input features (Liaw and Wiener Citation2002). For each feature, starting with the most relevant, negative values (on the y-axis) indicated that the positive class (reinternalization) was less likely for that value of the independent variable (on the x-axis). Similarly, positive values (on the y-axis) indicated that the positive class (reinternalization) was more likely for the given value of the independent variable (on the x-axis). Zero implied no average impact on class probability.

Figure 2. The marginal effects of the predictor variables on the probability of the class reinternalization; for the mathematical derivation of the ‘degree of partial dependence’ depicted on the y-axis, see Liaw and Wiener (Citation2002, 13).

Country characteristics also differed substantially: In Germany, a ceased company’s function or form was comparatively rarely reinternalized; in England, reinternalization was highly probable ().

Regarding company lifespan, a partially steady increase in the probability of reinternalization was observed, which implies that the older the company, the more likely it is to reinternalize. However, there are clear variations, with a very low probability of reinternalization in the first 10–15 years of a company’s existence, a very high one in years 15–20, and a marked increase from there after a company turns 30 years old ().

While company size has a comparatively small influence on local governments’ response and, consequently, both large and small companies are likely to be brought in-house, very large companies tend to be reinternalized to full control of the core administration ().

Although service type played the largest role in the decision for/against reinternalization, the partial-dependence plot shows a more nuanced situation. Social housing seems to be preferentially absorbed into full control of the core administration, but this is not the case for other social services; education and, as expected, the environment and transport sectors, have the highest likelihood of an alternative form of restructuring. Additionally, reinternalization seems the most likely choice for development ().

For companies with more than one owner, the probability of reinternalization fell drastically and remained consistently low when the number of shareholders exceeded 12 ().

The results for public ownership and ownership distribution were more ambiguous. Regarding share of public ownership in a company, an overall linear relationship between the two benchmarks was observable. Interestingly, two peaks can be identified, indicating that companies with a public share of 50% and those wholly owned by the local government are most likely to be reinternalized (). Companies with fully balanced ownership were most likely to be reinternalized; all others were restructured elsewhere or fully dissolved, with the probability slightly increasing at a Gini-value of >0.4 ().

Discussion

This study applied a tension lens to investigate whether LGCs are reinternalized into core administration after their cessation. It rendered reinternalization as a move towards a context, as I argued, more in line with a local government’s premises. Looking at the descriptive dataset, while no reinternalization is the most likely choice when termination is considered, reinternalization is a thoroughly applied alternative (29.9% of all observations, see APPENDIX, ). Therefore, it is even more surprising that research has largely neglected this type of final resolution reached.

To address this, I analysed novel longitudinal data of 244 terminated LGCs across English and German local governments through an ML technique. The findings contribute to raising awareness of underlying tensions inherent in local governance reform choices and shifting empirical attention from the ubiquitous ‘outward’ dynamics of local public service delivery to the ‘inward’, reiterating that organizations can have a ‘[lively] life after death’ (MacCarthaigh Citation2014, 1034).

The findings demonstrate that resourcing decisions are more strongly determined by tensions proxied by a company’s service type, lifespan, and national context. The limited significance of size lends weight to the low to no effects observed by Corbett and Howard (Citation2017).

Except for size, the less-contributing variables all relate to a company’s ownership structure. While this is interesting and transcends quantitative survival studies, which often focus on organizational national culture, size, and age, the lack of relative model relevance may suggest that formal ownership is not as crucial to decisions or as conflictual (Friedländer, Röber, and Schäfer Citation2021), and that tensions are also caused by other levels of vulnerabilities, rationally or irrationally motivated (Da Cruz and Marques Citation2012; Rackwitz and Raffer Citationwork in progress), also see the debate on ownership publicness versus control publicness by Bozeman and Bretschneider (Citation1994). The relative model relevance of tensions proxied by life span and size, both key factors prominently cited by population ecologists for the survival of private firms, also states – crucially – that while there is potential for more integrative theory, the transferability of arguments valid for the private sector is a task that needs to be carefully crafted because, as the highest model relevance of service clearly shows, these arguments remain incomplete for public sector corporate dynamics. These are insights that cater to Andrews (Citation2020) and Gradus and Budding’s (Citation2020) calls yet urge research to more closely examine the impact of service characteristics on organizational termination and, more generally, their suitability for being corporatized by a public authority in the first place.

Moreover, tensions may be mutually constitutive (Lüscher and Lewis Citation2008), and organizational macro and micro levels intertwined (Andriopoulos and Lewis Citation2009). While the random-forests approach accounts to some extent for this cross-level dependence, it strikes that the tensions with the highest model relevance refer to external forces that apply to a large population of organizations that are similarly affected by macrosystemic challenges (tensions) such as national culture, service type, or age, while the others are conversely internal forces that apply to a subsystem facing relatively individual microsystemic challenges (tensions), such as size, or ownership. Compared to microsystemic variables, tensions associated with macrosystemic variables are seen as more permanent or ‘appear intractable’ (Jarzabkowski et al. Citation2019, 1) and are thus difficult to moderate individually (Vangen Citation2017b). Additionally, as I deduce, public powerholders may perceive little leeway for synchronization, consequently leading them to favour resourcing. Therefore I may propose a pattern linking tensions and responses to the debate, suggesting that tensions arising from macrosystemic rather than microsystemic settings are more likely to determine institutional responses (cf. the literature of scale on collective action problem-solving, e.g. Hahn and Knight Citation2021). However, substantial research is needed to identify the underlying causal mechanisms more clearly (Jarzabkowski, Lê, and van de Ven Citation2013).

The findings regarding particular attribute levels of features proxying tensions that lead local governments to choose or refuse reinternalization are more puzzling, only partially backing the hypothesis.

Contrary to my assumption and contrasting Andrews (Citation2020), all services with social relevance (except housing) have a low likelihood of being brought in-house. This high probability for housing could stem from the fact that it is characterized by sensitive public interest and is thus a highly controversial, low-market service, for which disruption is generally not considered a social good. Additionally, especially in England, there have been relatively negative experiences concerning ‘arms-length’ entities inadequately fulfiling their housing responsibilities, which manifested tensions that were defensively countered by institutional reorganizations (e.g. the landmark case of London’s Grenfell Tower; Hodkinson Citation2020).

The results suggesting that development services tend to provoke reinternalization are less intuitive. However, this could be traced to the inconsistent level of quality measurement and commerciality of the related sub-services, which, in turn, have a less polarizing proneness to tensions in line with Brown and Potoski (Citation2005). While these findings fuel the debate about which services are suitable for outward provision in the first place, greater nuance in further studies may provide greater clarity.

Inconsistent with the hypothesis, the evidence for ownership suggests that where there is arguably a lower level of tension and, thus, a greater degree of cognitive agreement (Makhija and Ganesh Citation1997), such as occurs with full public, sole, and perfectly balanced ownership, reinternalization tends to be preferred.

Similarly, the findings do not confirm governments reclaim very young or small companies susceptible to tensions; this is more likely for older and larger companies. This could be explained by Fichman and Levinthal’s ‘liability of adolescence’ (Citation1991, 442), which states that companies, after an initially vulnerable period of orientation, consolidate their preferred ‘beliefs’ or ‘psychological commitment’; when these do not accord with those of the core administration, tensions arise, which could result in reinternalization. These results could, however, also stem from a measurement idiosyncrasy, and it may be the ‘perceived’ rather than actual size of a company that causes tension and, as Corbett and Howard (Citation2017) demonstrate, triggers termination.

Contrasting with my assumption, the results indicate that reinternalization is more likely in England and, thus, in a traditionally more market-affirmative environment, an environment expected to be less fraught with tension. This, however, may well reflect England’s more radical either/or approaches to reform decisions (Cooper et al. Citation2021). It should also be noted that the German local corporatization landscape exhibits increasingly branched structures of directly and indirectly owned entities (Rackwitz and Raffer Citationwork in progress). This means German local government administrations have greater scope for applying alternative organizational forms that gradually increase their influence on services (Torsteinsen Citation2019; Wollmann Citation2016). Against historically stronger scepticism towards neo-liberal reforms, this illustrates a less radical, more ambivalent market attitude (Cumbers and Becker Citation2018) that tends to avoid both privatized delivery (low control) and in-house delivery (full control).

Concurrently, however, the relevance of this variable is comparatively low, which again puts the context dependency into perspective and suggests that the directional potential of national culture may be overrated (cf. Schröter Citation2019) and that other overarching corporate dynamics are involved (see APPENDIX, for illustration of the final findings in consideration of macro- versus micro-level tensions).

Overall, the hypothesis requires a more differentiated view, in that ‘tense times’ do not necessarily result in some type of company termination. For instance, challenging Cui, Calantone, and Griffith (Citation2011), Talay and Akdeniz (Citation2009) find that goal incongruence does not contribute significantly to termination, which they attribute to timely tension navigation, as also suggested by Skelcher and Smith (Citation2015). In-depth process tracing on effective management and leadership interventions will clarify.

Awareness of underlying tensions – that may guide the decision to choose or refuse a particular type of termination – can stimulate reflective management practice and aid practitioners in making conscious decisions that consider potential tensions and their consequences early on. At the same time, it cautions public managers not to simply ‘borrow’ strategic solutions from their private sector colleagues and vice-versa.

Limitations and future research avenues

Some limitations to this study should be acknowledged but at the same time open new research opportunities. First, the tensions proxied in their combination were intended to represent the unique composition of LGCs, yet are merely exemplary; termination outcomes may be related to additional, unobserved parameters. For example, another interesting potential tension would be a funding or aid institution paradox; more specifically, how funding the problem and the solution impedes (a company’s) progress (Fleming et al. Citation2021). In fact, the analysis did not distinguish between voluntary and compulsory company closures, yet, these are sometimes forced due to discontinued funding or legislative change at the EU (at least prior to Brexit, single market rules might, e.g. explain some of the lack of reabsorption of environment and transport sectors, see Pollitt Citation2019; Rosell and Saz-Carranza Citation2020) or national levels (e.g. austerity pressure post-financial crisis pushing authorities into changing ownership and organizational forms, see Cumbers and Becker Citation2018; Torsteinsen Citation2019).

Second, while this MDSD helped to detect overarching patterns by providing data variance, it naturally reduces comparability. For both aspects, a more detailed country comparison with case-sensitive analyses is key to add to the picture. This may involve taking into account the countries’ regulatory frameworks, the local single-tier board (England) versus two-tier board (Germany) structures and their effect on politicians’ monitoring role in operational decisions (Andrews Citation2020), or the mediating effect of a local government’s historical expertise in managing tensions. Such aspects are all likely to influence the ability and need of local government to bring functions back under full control. Future studies could pursue contextual elements further, including inquiries into institutional heterogeneity given the cases’ large spatial dispersion within each country (see APPENDIX, ). Moreover, it would be interesting to see how a company’s ‘perceived’ size relates differently to tensions and termination outcomes compared with its actual size (Corbett and Howard Citation2017). Relatedly, as noted earlier, caution is warranted in transferring theory assumptions from the literature on private firms to their public counterparts one-to-one. A replication of this study in private sector environments would be insightful and elaborate on cross-sectoral differences and similarities in termination dynamics more soundly.

Third, the design focused on limited liability companies and one specific delivery mode following termination, but this was at the expense of nuance. Hence, it would be promising to explore termination linked to different LGC organizational forms and zoom in on the ‘no reinternalization’ variable and its facets to obtain an even more nuanced understanding of local governments’ sourcing decisions. While the latter was not possible for this paper due to the limited number of companies terminated in the study period, it could be achieved by successively adding more data points to the set, such as more countries, service types, or, in the future, more years, thus gradually improving the algorithm.

Similarly, ML and the random-forest approach offer many advantages not only for this study’s research question and data basis but also generally for tracing decision-making in dynamic governance contexts, holding unprecedented opportunities for increasingly sound policymaking even with limited data available. That being said, this method also involves artificially generated cases; thus, expanding the sample to include more companies would be useful for increasing the robustness of the findings.

Conclusion

By bridging the literature on corporatization and organizational survival, the very concept of organizational tension offers a useful approach to reconciling explanations for public-management reform strategies. More specifically, this study encourages focusing on the widely neglected inward dynamics of service provision by representing an attempt to elucidate the explanatory potential of ‘tense times’ to understand a local government’s sourcing decisions. This lays the foundation for more extensive testing and refinement, for which ML has proven valuable, provided careful tuning of hyperparameters and sufficiently large and sound databases. It also highlights that, whilst advanced analyses of corporatization as a middle-ground strategy will continue to be critical, its reversal and the corresponding consequences for local governments deserve future visibility in a renewed research agenda.

Acknowledgment

Parts of this research were conducted during a research stay at the Blavatnik School of Government (BSG), University of Oxford, funded by the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) under grant number: 57556282. I am grateful to the BSG and DAAD for their support

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. With ‘bad’ times, Camões and Rodrigues (2021, 7) refer to times of financial instability and austerity in the aftermath of the global financial crises, especially from 2011 to 2012.

2. While commonly applied, the term of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ as primary designation for English culture has lately been contested, see, e.g. Rambaran-Olm and Wade (2022).

3. A recent study finds a 48% increase in corporatization intensity, which includes all directly- and indirectly-owned LGCs in 34 German cities from 1998 to 2017 (Rackwitz and Raffer work in progress).

4. I would like to thank especially Rhys Andrews for sharing initial data for the English set.

References

- Aars, J., and H. Ringkjøb. 2011. “Local Democracy Ltd.” Public Management Review 13 (6): 825–844. doi:10.1080/14719037.2010.539110.

- Abatecola, G., R. Cafferata, and S. Poggesi. 2012. “Arthur Stinchcombe’s “Liability of newness”: Contribution and Impact of the Construct.” Journal of Management History 18 (4): 402–418. doi:10.1108/17511341211258747.

- Adam, C., M. W. Bauer, C. Knill, and P. Studinger. 2007. “The Termination of Public Organizations: Theoretical Perspectives to Revitalize a Promising Research Area.” Public Organization Review 7 (3): 221–236. doi:10.1007/s11115-007-0033-4.

- Alajoutsijärvi, K., K. Juusola, and M. Siltaoja. 2015. “The Legitimacy Paradox of Business Schools: Losing by Gaining?” Academy of Management Learning & Education 14 (2): 2772–2791. doi:10.5465/amle.2013.0106.

- Albalate, D., G. Bel, and E. Reeves. 2022. “Are We There Yet? Understanding the Implementation of Re-Municipalization Decisions and Their Duration.” Public Management Review 24 (6): 951–974. doi:10.1080/14719037.2021.1877795.

- Aldrich, H. E., and E. R. Auster. 1986. “Even Dwarfs Started Small: Liabilities of Age and Size and Their Strategic Implications.“ Research in Organizational Behavior 8 (2): 165–198.

- Anastasopoulos, L. J., and A. B. Whitford. 2019. “Machine Learning for Public Administration Research, with Application to Organizational Reputation.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 29 (3): 491–510. doi:10.1093/jopart/muy060.

- Andresani, G., and E. Ferlie. 2006. “Studying Governance Within the British Public Sector and Without.” Public Management Review 8 (3): 415–431. doi:10.1080/14719030600853220.

- Andrews, R. 2020. “Organizational Publicness and Mortality: Explaining the Dissolution of Local Authority Companies.” Public Management Review 24 (3): 350–371. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1825780.

- Andrews, R., J. Clifton, and L. Ferry. 2022. “Corporatization of Public Services.” Public Administration 100 (2): 179–192. doi:10.1111/padm.12848.

- Andrews, R., M. Esteve, and T. Ysa. 2015. “Public–Private Joint Ventures: Mixing Oil and Water?” Public Money & Management 35 (4): 265–272. doi:10.1080/09540962.2015.1047267.

- Andrews, R., L. Ferry, C. Skelcher, and P. Wegorowski. 2019. “Corporatization in the Public Sector: Explaining the Growth of Local Government Companies.” Public Administration Review 80 (3): 482–493. doi:10.1111/puar.13052.

- Andriopoulos, C., and M. W. Lewis. 2009. “Exploitation-Exploration Tensions and Organizational Ambidexterity: Managing Paradoxes of Innovation.” Organization Science 20 (4): 696–717. doi:10.1287/orsc.1080.0406.

- APSE. 2019. Rebuilding Capacity. The Case for Insourcing Public Contracts. Manchester, UK: Association for Public Service Excellence.

- Ashforth, B. E., and P. H. Reingen. 2014. “Functions of Dysfunction: Managing the Dynamics of an Organizational Duality in a Natural Food Cooperative.” Administrative science quarterly 59 (3): 474–516.

- Askim, J., J. Blom-Hansen, K. Houlberg, and S. Serritzlew. 2020. “How Government Agencies React to Termination Threats.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 30 (2): 324–338. doi:10.1093/jopart/muz022.

- Battilana, J., and S. Dorado. 2010. “Building Sustainable Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Commercial Microfinance Organizations.” Academy of Management Journal 53 (6): 1419–1440. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.57318391.

- Becker, S., R. Beveridge, and M. Naumann. 2015. “Remunicipalization in German Cities: Contesting Neo-Liberalism and Reimagining Urban Governance?” Space and Polity 19 (1): 76–90. doi:10.1080/13562576.2014.991119.

- Bel, G., M. Esteve, J. C. Garrido, and J. L. Zafra‐gómez. 2022. “The Costs of Corporatization: Analysing the Effects of Forms of Governance.” Public Administration 100 (2): 232–249. doi:10.1111/padm.12713.

- Benson, J. K. 1977. “Organizations: A Dialectical View.” Administrative Science Quarterly 22 (1): 3–21. doi:10.2307/2391741.

- Berge, D. M., and H. Torsteinsen. 2022. “Corporatization in Local Government: Promoting Cultural Differentiation and Hybridity?” Public Administration 100 (2): 273–290. doi:10.1111/padm.12737.

- Boin, A., S. Kuipers, and M. Steenbergen. 2010. “The Life and Death of Public Organizations: A Question of Institutional Design?” Governance 23 (3): 385–410. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2010.01487.x.

- Bouckaert, G., B. G. Peters, and K. Verhoest. 2010. The Coordination of Public Sector Organizations: Shifting Patterns of Public Management. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bozeman, B., and S. Bretschneider. 1994. “The ‘Publicness puzzle’ in Organization Theory: A Test of Alternative Explanations of Differences Between Public and Private Organizations.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 4 (2): 197–224.

- Breiman, L. 2001. “Random Forests.” Machine Learning 45 (1): 5–32. doi:10.1023/A:1010933404324.

- Breiman, L. 2017. Classification and Regression Trees. New York, USA.: Routledge.

- Breiman, L., J. H. Friedman, R. A. Olshen, and C. J. Stone. 1984. CART: Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont, USA: Wadsworth.

- Brown, T. L., and M. Potoski. 2005. “Transaction Costs and Contracting: The Practitioner Perspective.” Public Performance & Management Review 28 (3): 326–351.

- Bulkeley, H., and K. Kern. 2006. “Local Government and the Governing of Climate Change in Germany and the UK.” Urban Studies 43 (12): 2237–2259. doi:10.1080/00420980600936491.

- Bureau Van Dijk. 2022. https://www.bvdinfo.com/en-gb/our-products/data/national/fame

- Camões, P. J., and M. Rodrigues. 2021. “From Enthusiasm to Disenchantment: An Analysis of the Termination of Portuguese Municipal Enterprises.” Public Money & Management 41 (5): 387–394. doi:10.1080/09540962.2020.1763605.

- Cappellaro, G., P. Tracey, and R. Greenwood. 2020. “From Logic Acceptance to Logic Rejection: The Process of Destabilization in Hybrid Organizations.” Organization Science 31 (2): 415–438. doi:10.1287/orsc.2019.1306.

- Christensen, T., P. Lægreid, and K. A. Røvik. 2020. Organization Theory and the Public Sector: Instrument, Culture and Myth. London, UK: Routledge.

- Cloutier, C., and A. Langley. 2017. “Negotiating the Moral Aspects of Purpose in Single and Cross-Sectoral Collaborations.” Journal of Business Ethics 141 (1): 103–131. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2680-7.

- Collin, S. O., T. Tagesson, A. Andersson, J. Cato, and K. Hansson. 2009. “Explaining the Choice of Accounting Standards in Municipal Corporations: Positive Accounting Theory and Institutional Theory as Competitive or Concurrent Theories.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 20 (2): 141–174. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2008.09.003.

- Cooper, C., J. Tweedie, J. Andrew, and M. Baker. 2021. “From ‘Business‐like’ to Businesses: Agencification, Corporatization, and Civil Service Reform Under the Thatcher Administration.” Public Administration 100 (2): 193–215. doi:10.1111/padm.12732.

- Corbett, J., and C. Howard. 2017. “Why Perceived Size Matters for Agency Termination.” Public Administration 95 (1): 196–213. doi:10.1111/padm.12299.

- Cui, A. S., R. J. Calantone, and D. A. Griffith. 2011. “Strategic Change and Termination of Interfirm Partnerships.” Strategic Management Journal 32 (4): 402–423. doi:10.1002/smj.881.

- Cumbers, A., and S. Becker. 2018. “Making Sense of Remunicipalization: Theoretical Reflections on and Political Possibilities from Germany’s Rekommunalisierung Process.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (3): 503–517. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy025.

- Da Cruz, N. F., and R. C. Marques. 2012. “Mixed Companies and Local Governance: No Man Can Serve Two Masters.” Public Administration 90 (3): 737–758. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.02020.x.

- Das, T. K., and B. S. Teng. 2000. “Instabilities of Strategic Alliances: An Internal Tensions Perspective.” Organization Science 11 (1): 77–101. doi:10.1287/orsc.11.1.77.12570.

- Dyson, K. H. 1980. The State Tradition in Western Europe: A Study of an Idea and Institution. Oxford, UK: Robertson.

- Elston, T., M. Rackwitz, and G. Bel. forthcoming. “Going Separate Ways. Ex-Post Interdependence and the Dissolution of Collaborative Relations.” International Public Management Journal.

- Ferry, L., R. Andrews, C. Skelcher, and P. Wegorowski. 2018. “Corporatization of Local Authorities in England in the Wake of Austerity 2010–2016.” Public Money & Management 38 (6): 477–480. doi:10.1080/09540962.2018.1486629.

- Fichman, M., and D. A. Levinthal. 1991. “Honeymoons and the Liability of Adolescence: A New Perspective on Duration Dependence in Social and Organizational Relationships.” Academy of Management Review 16 (2): 442–468. doi:10.2307/258870.

- Fiss, P., and E. Zajac. 2004. “The Diffusion of Ideas Over Contested Terrain: The (Non) Adoption of a Shareholder Value Orientation Among German Firms.” Administrative Science Quarterly 49 (4): 501–534. doi:10.2307/4131489.

- Fleming, P. J., M. M. Spolum, W. D. Lopez, and S. Galea. 2021. “The Public Health Funding Paradox: How Funding the Problem and Solution Impedes Public Health Progress.” Public Health Reports 136 (1): 10–13. doi:10.1177/0033354920969172.

- Freeman, J., G. Carroll, and M. T. Hannan. 1983. “The Liability of Newness: Age Dependence in Organizational Death Rates.” American Sociological Review 48 (5): 692–710. doi:10.2307/2094928.

- Friedländer, B., M. Röber, and C. Schäfer. 2021. “Institutional Differentiation of Public Service Provision in Germany: Corporatisation, Privatisation and Re-Municipalisation.” In Public Administration in Germany, edited by S. Kuhlmann, I. Proeller, D. Schimanke, and J. Ziekow, 291–309. Cham, Germany: Palgrave Macmillan.

- German Federal Statistical Office 2021. https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online?operation=previous&levelindex=2&step=1&titel=Tabellenaufbau&levelid=1658304763262&levelid=1658304663432#abreadcrumb

- Gradus, R., and T. Budding. 2020. “Political and Institutional Explanations for Increasing Re-Municipalization.” Urban Affairs Review 56 (2): 538–564. doi:10.1177/1078087418787907.

- Grimmer, J., M. E. Roberts, and B. M. Stewart. 2021. “Machine Learning for Social Science: An Agnostic Approach.” Annual Review of Political Science 24 (1): 395–419. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-053119-015921.

- Gulati, R., and P. Puranam. 2009. “Renewal Through Reorganization: The Value of Inconsistencies Between Formal and Informal Organization.” Organization Science 20 (2): 422–440. doi:10.1287/orsc.1090.0421.

- Hahn, T., and E. Knight. 2021. “The Ontology of Organizational Paradox: A Quantum Approach.” Academy of Management Review 46 (2): 362–384. doi:10.5465/amr.2018.0408.

- Hannan, M. T., and J. Freeman. 1989. Organizational Ecology. Cambridge, USA: Harvard University Press.

- Henry, L. A., A. Rasche, and G. Moellering. 2022. “Managing Competing Demands: Coping with the Inclusiveness–Efficiency Paradox in Cross-Sector Partnerships.” Business & Society 61 (21): 267–304. doi:10.1177/0007650320978157.

- Hodkinson, S. 2020. Safe as Houses: Private Greed, Political Negligence and Housing Policy After Grenfell. Manchester UK: Manchester University Press.

- Huxham, C., and S. Vangen. 2005. Managing to Collaborate: The Theory and Practice of Collaborative Advantage. London, UK: Routledge.

- Jarzabkowski, P., R. Bednarek, K. Chalkias, and E. Cacciatori. 2019. “Exploring Inter-Organizational Paradoxes: Methodological Lessons from a Study of a Grand Challenge.” Strategic Organization 17 (1): 120–132. doi:10.1177/1476127018805345.

- Jarzabkowski, P., and J. K. Lê. 2017. “We Have to Do This and That? You Must Be Joking: Constructing and Responding to Paradox Through Humor.” Organization Studies 38 (3–4): 433–462. doi:10.1177/0170840616640846.

- Jarzabkowski, P., J. K. Lê, and A. H. van de Ven. 2013. “Responding to Competing Strategic Demands: How Organizing, Belonging, and Performing Paradoxes Coevolve.” Strategic Organization 11 (3): 245–280. doi:10.1177/1476127013481016.

- Jay, J. 2013. “Navigating Paradox as a Mechanism of Change and Innovation in Hybrid Organizations.” Academy of Management Journal 56 (1): 137–159. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0772.

- John, P. 2000. “The Europeanisation of Sub-National Governance.” Urban Studies 37 (5–6): 877–894.

- Kaufman, H. 1976. Are Government Organizations Immortal?. Washington, DC, USA: The Brookings Institution.

- Keller, J., J. Loewenstein, and J. Yan. 2017. “Culture, Conditions and Paradoxical Frames.” Organization Studies 38 (3–4): 539–560. doi:10.1177/0170840616685590.

- Kishimoto, S., and O. Petitijean. 2017. Reclaiming Public Services: How Cities and Citizens are Turning Back Privatisation. Paris, France/Amsterdam, Netherlands: Transnational Institute.

- Kwon, H., T. A. Pardo, and G. B. Burke. 2006. “Interorganisational Collaboration and Community Building for the Preservation of State Government Digital Information: Lessons from NDIIPP State Partnership Initiative.” Government Information Quarterly 26 (1): 186–192. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2008.01.007.

- Labour. 2020. https://labour.org.uk/press/labour-announcesinsourcing-revolution-end-scandal-public-service-outsourcingjohn-mcdonnell/

- Lægreid, P., and K. Verhoest, eds. 2010. Governance of Public Sector Organizations: Proliferation, Autonomy and Performance. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lamothe, S., M. Lamothe, and R. C. Feiock. 2008. “Examining Local Government Service Delivery Arrangements Over Time.” Urban Affairs Review 44 (1): 27–56. doi:10.1177/1078087408315801.

- Leixnering, S., R. E. Meyer, and T. Polzer. 2021. “Hybrid Coordination of City Organizations: The Rule of People and Culture in the Shadow of Structures.” Urban Studies 58 (14): 2933–2951. doi:10.1177/0042098020963854.

- Lewis, M. W. 2000. “Exploring Paradox: Toward a More Comprehensive Guide.” Academy of Management Review 25 (4): 760–776. doi:10.2307/259204.

- Liaw, A., and M. Wiener. 2002. “Classification and Regression by randomForest.” R News 2 (3): 18–22.

- Li, Y., Y. A. Zhang, and W. Shi. 2020. “Navigating Geographic and Cultural Distances in International Expansion: The Paradoxical Roles of Firm Size, Age, and Ownership.” Strategic Management Journal 41 (5): 921–949. doi:10.1002/smj.3098.

- Lüscher, L., and M. W. Lewis. 2008. “Organizational Change and Managerial Sensemaking: Working Through Paradox.” Academy of Management Journal 51 (2): 221–240. doi:10.5465/amj.2008.31767217.

- MacCarthaigh, M. 2014. “Agency Termination in Ireland: Culls and Bonfires, or Life After Death?” Public Administration 92 (4): 1017–1037. doi:10.1111/padm.12093.

- Makhija, M. V., and U. Ganesh. 1997. “The Relationship Between Control and Partner Learning in Learning-Related Joint Ventures.” Organization Science 8 (5): 508–520. doi:10.1287/orsc.8.5.508.

- North Data. 2022. URL: https://www.northdata.de/ [25.01.2022].

- Ospina, S., and E. Foldy. 2015. “Enacting Collective Leadership in a Shared-Power World“ In Handbook of Public Administration, edited by Perry, J. L., and R. K. Christensen, 489–507. San Francisco, USA: Jossey-Bass.

- Ospina, S. M., and A. Saz-Carranza. 2010. “Paradox and Collaboration in Network Management.” Administration & Society 42 (4): 404–440. doi:10.1177/0095399710362723.

- Park, S. H., and G. R. Ungson. 1997. “The Effect of National Culture, Organizational Complementarity, and Economic Motivation on Joint Venture Dissolution.” Academy of Management Journal 40 (2): 279–307. doi:10.2307/256884.

- Pesch, U. 2008. “The Publicness of Public Administration.” Administration & Society 40 (2): 170–193. doi:10.1177/0095399707312828.

- Pollitt, M. G. 2019. “The European Single Market in Electricity: An Economic Assessment.” Review of Industrial Organization 55 (1): 63–87. doi:10.1007/s11151-019-09682-w.

- Pollitt, C., and G. Bouckaert. 2017. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis - into the Age of Austerity. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Provan, K. G., and P. Kenis. 2008. “Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (2): 229–252. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum015.

- Przeworski, A., and H. Teune. 1970. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry (Comparative Studies in Behavioral Science). Hoboken, USA: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Purdy, J. M. 2012. “A Framework for Assessing Power in Collaborative Governance Processes.” Public Administration Review 72 (3): 409–417. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02525.x.

- Rackwitz, M., and C. Raffer. work in progress. “Shifts in Corporatization Intensity. Evidence from German Cities.”

- Rambaran-Olm, M., and E. Wade. 2022. “What’s in a Name? The Past and Present Racism in ‘Anglo-Saxon’ Studies.” The Yearbook of English Studies 52 (1): 135–153. doi:10.1353/yes.2022.0010.

- Raza‐ullah, T., M. Bengtsson, and S. Kock. 2014. “The Coopetition Paradox and Tension in Coopetition at Multiple Levels.” Industrial Marketing Management 43 (2): 189–198. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.11.001.

- Reades, J., J. De Souza, and P. Hubbard. 2019. “Understanding Urban Gentrification Through Machine Learning.” Urban Studies 56 (5): 922–942. doi:10.1177/0042098018789054.

- Rosell, J., and A. Saz-Carranza. 2020. “Determinants of Public–Private Partnership Policies.” Public Management Review 22 (8): 1171–1190. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1619816.

- Schad, J., M. W. Lewis, S. Raisch, and W. K. Smith. 2016. “Paradox Research in Management Science: Looking Back to Move Forward.” The Academy of Management Annals 10 (1): 5–64. doi:10.5465/19416520.2016.1162422.

- Scherer, A. G., G. Palazzo, and D. Seidl. 2013. “Managing Legitimacy in Complex and Heterogeneous Environments: Sustainable Development in a Globalized World.” Journal of Management Studies 50 (2): 259–284. doi:10.1111/joms.12014.

- Schrage, S., and A. Rasche. 2021. “Inter-Organizational Paradox Management: How National Business Systems Affect Responses to Paradox Along a Global Value Chain.” Organization Studies 43 (4): 547–571. doi:10.1177/0170840621993238.

- Schröter, E. 2019. “Culture’s Consequences? In Search of Cultural Explanations of British and German Public Sector Reform.“ In Comparing Public Sector Reform in Britain and Germany. Key Traditions and Trends of Modernisation, edited by H Wollmann and E Schröter, 198–223. London, UK: Routledge.

- Schröter, E., M. Röber, and J. Röber. 2019. “Re-Discovering the Political Rationale of Public Ownership: Explaining the Creation, Proliferation and Persistence of Government-Owned Enterprises.” Zeitschrift für Öffentliche und Gemeinwirtschaftliche Unternehmen (ZÖgU)/Journal for Public & Nonprofit Services 42 (3): 198–214. doi:10.5771/0344-9777-2019-3-198.

- Singh, J. V., R. J. House, and D. J. Tucker. 1986. ““Organizational Change and Organizational Mortality.” Administrative Science Quarterly” 31 (4): 587–611. doi:10.2307/2392965.

- Skelcher, C., and S. R. Smith. 2015. “Theorizing Hybridity: Institutional Logics, Complex Organizations, and Actor Identities: The Case of Nonprofits.” Public Administration 93 (2): 433–448. doi:10.1111/padm.12105.

- Smith, W. K., and M. W. Lewis. 2011. “Toward a Theory of Paradox: A Dynamic Equilibrium Model of Organizing.” Academy of Management Review 36 (2): 381–403. doi:10.5465/AMR.2011.59330958.

- Sonpar, K., F. Pazzaglia, and J. Kornijenko. 2010. “The Paradox and Constraints of Legitimacy.” Journal of Business Ethics 95 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0344-1.

- Stinchcombe, A. L. 1965. “Social Structure and Organizations.” In Handbook of Organizations, edited by J. G. March, 142–193. Chicago, USA: Rand McNally.

- Sullivan, H., P. Williams, M. Marchington, and L. Knight. 2013. “Collaborative Futures: Discursive Realignments in Austere Times.” Public Money & Management 33 (2): 123–130. doi:10.1080/09540962.2013.763424.

- Talay, M. B., M. B. Akdeniz, R. R. Sinkovics, and P. N. Ghauri. 2009. “What Causes Break-Ups? Factors Driving the Dissolution of Marketing-Oriented International Joint Ventures“ In New Challenges to International Marketing, edited by R. R. Sinkovics, and P. N. Ghauri, 227–256. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

- Torsteinsen, H. 2019. “Debate: Corporatization in Local Government– the Need for a Comparative and Multidisciplinary Research Approach.” Public Money & Management 39 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1080/09540962.2019.1537702.

- Tracey, P., N. Phillips, and O. Jarvis. 2011. “Bridging Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Creation of New Organizational Forms: A Multilevel Model.” Organization Science 22 (1): 60–80. doi:10.1287/orsc.1090.0522.

- Tremml, T. 2020. “Barriers to Entrepreneurship in Public Enterprises: Boards Contributing to Inertia.” Public Management Review 23 (10): 1527–1552. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1775279.

- Vangen, S. 2017a. “Culturally Diverse Collaborations: A Focus on Communication and Shared Understanding.” Public Management Review 19 (3): 305–325. doi:10.1080/14719037.2016.1209234.

- Vangen, S. 2017b. “Developing Practice‐oriented Theory on Collaboration: A Paradox Lens.” Public Administration Review 77 (2): 263–272. doi:10.1111/puar.12683.

- Voorn, B., M. L. van Genugten, and S. van Thiel. 2017. “The Efficiency and Effectiveness of Municipally Owned Corporations: A Systematic Review.” Local Government Studies 43 (5): 820–841. doi:10.1080/03003930.2017.1319360.

- Voorn, B., M. L. van Genugten, and S. van Thiel. 2021. “Re-Interpreting Re-Municipalization: Finding Equilibrium.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 24 (3): 305–318. doi:10.1080/17487870.2019.1701455.

- Warner, M. 2008. “Reversing Privatization, Rebalancing Government Reform: Markets, Deliberation and Planning.” Policy and Society 27 (2): 163–174. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2008.09.001.

- Williamson, O. 1981. “The Economics of Organization: The Transaction Cost Approach.” The American Journal of Sociology 87 (3): 548–577. doi:10.1086/227496.

- Wollmann, H. 2016. “Comparative Study of Public and Social Services Provision.” In Public and Social Services in Europe: From Public & Municipal to Private Sector Provision, edited by H. Wollmann, I. Kopric, and G. Marcou, 1–12. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.