ABSTRACT

This article explores scaling deep through transformative learning in Public Sector Innovation Labs (PSI labs) as a pathway to increase the impacts of their work. Using literature review and participatory action research with two PSI labs in Vancouver and Auckland, we provide descriptions of how they enact transformative learning and scaling deep. A shared ambition for transformative innovation towards social and ecological wellbeing sparked independent moves towards scaling deep and transformative learning which, when compared, offer fruitful insights to researchers and practitioners. The article includes a PSI lab typology and six moves to practice transformative learning and scaling deep.

Introduction

The term ‘innovation’ is defined, interpreted, and applied differently across public sector contexts, as well as by public sector innovation labs (PSI labs) (Bason Citation2010, Citation2017; Brookfield Institute Citation2018; Brown and Osborne Citation2013; Considine and Lewis Citation2007; Gieske, van Buuren, and Bekkers Citation2016; Gryszkiewicz, Lykourentzou, and Toivonen Citation2016; Hartley, Sørensen, and Torfing Citation2013; Lewis Citation2021; McGann, Blomkamp, and Lewis Citation2018; Ricard et al. Citation2017; Sørensen and Torfing Citation2011; Tõnurist, Kattel, and Lember Citation2017). Public sector innovation (PSI) often focuses on innovative strategies, programmes, services, and projects that can be rapidly ‘scaled out’ across departments or communities. These tend to create surface-level changes but do not (or cannot) challenge or transform the underpinning assumptions or values upon which the interventions are based (Bencio Citation2018; Kieboom Citation2014; Moore Citation2017; Riddell and Moore Citation2015; Ryan and Koh Citation2018; Schulman CitationAugust 2013; Westley and Antadze Citation2010; Westley et al. Citation2014). Over time, we have seen that such efforts can cause harm because they ensure that the public sector looks to be busy addressing pressing issues and demonstrating success using scaling out and other traditional public sector measures, but there is no effort to tackle root causes. When working on social and ecological justice and wellbeing in particular, these root causes must be questioned and reimagined.

This article draws upon the experiences of two PSI labs grappling with the complex and urgent issues of social and ecological justice and wellbeing, Solutions Lab (SLab) in Vancouver, Canada and Co-Design Lab (The Lab) in Tāmaki/Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. Using these experiences and grounding in relevant literature, the article explores the potential of PSI labs to re-think their roles, shift purpose, and increase their impacts by scaling deep through transformative learning. Our framing and approach to innovation is grounded in the field of social innovation, described as a ‘complex process of introducing new products, processes or programmes that profoundly change the basic routines, resource and authority flows, or beliefs of the social system in which the innovation occurs’ (Westley and Antadze Citation2010, 2). The kinds of changes that the two PSI labs studied here seek to support, require challenging the dominant paradigms of power and governance that hold the status quo in place. Innovation in this context is not about surface-level changes that perpetuate the dominant paradigms and practices of government by making incremental and efficiency-oriented improvements, but about the transformation of power and systems towards new norms and paradigms which prioritize equity and ecologically sound outcomes.

Literature exploring paradigms of governance is vast, and we start by briefly situating our work within this. New Public Management (NPM) and settler colonialism are dominant governance systems from the local to national levels in the Canadian and New Zealand contexts, so when we frame our PSI research as a response to ‘dominant’ systems, structures, values, mindsets, and paradigms of governance this is a large part of what we mean. Much of what is written about PSI leaves these NPM and settler colonialism foundations in place; as stated earlier, our inquiry looks towards deeper and more transformative paradigmatic work. Literature covering emerging features of what comes after NPM is helpful in understanding the ways that governance paradigms define and shape what is meant by PSI – features of New Public Governance (NPG), post-NPM, network governance, neo-Weberian governance, design approaches, co-creation, co-production, and collaborative governance all provide useful signals and insights and are summarized briefly here.

Lewis et al. (Citation2017) characterize network governance as considering a diversity of different points of view, mobilizing resources, increasing flexibility of information flows, and trust building. Boukamel and Emery (Citation2017) call this phase post-NPM and characterize it as the creation of public value, enhancing democracy, transparency, and multidisciplinarity. Hartley et al. (Citation2013) describe neo-Weberian and collaborative governance as paying attention to different forms of leadership, inter- and intra-organizational coordination and collaboration, entrepreneurial approaches, citizen-centric behaviours, trust-based accountabilities, and the roles of different stakeholders in innovation processes. McGann et al. (Citation2021) explore co-production (as compared with deinstitutionalization, a more NPM-like approach to innovation) as an approach to PSI where citizens are active, participating, and mobilized contributors and co-creators of experiences, resources, and ideas to shape policy. Bason and Austin (Citation2022) describe an emerging form of human centred governance coming from the design lineage which they characterize as being relational, networked, interactive, and reflective. There is a large body of work on Indigenous governance systems which points to paradigms, systems, structures, values, and mindsets built on different foundations than those from Euro North American scholarly points of view, and a deep exploration of this body of work is outside the boundaries of this study. However, this resurgence of diverse Indigenous governance systems is provoking an active questioning, disrupting, reshaping, and remaking of the systems that the authors are working in and within the people that we are working with, and these ways of thinking about dominant systems of governance inform our thinking and writing here (for example, Goodchild Citation2021; Kimmerer Citation2013; Kovach Citation2009; Simpson Citation2017; Smith Citation2016; Topa and Narvaez Citation2022; Yunkaporta Citation2019).

The constructs of innovation paradigms, theory, processes, and practices are shaped by political, fiscal, social, ecological, and other issues as they rise and fall in their relative importance, and as different actors and sectors rise and fall in their ability and agency to influence public sector thinking and action. As these post-NPM paradigms emerge, it is becoming clearer that what is missing from earlier and still dominant paradigms of traditional bureaucracies and NPM are the theories and practices that help governments to respond to contemporary pressures that are very different than what has been seen before. The nature of complex, emergent, systems-, and justice-oriented challenges facing governments compels researchers and practitioners to seek new/resurgent paradigms and approaches to innovation, as neither traditional bureaucracies nor NPM is well suited to systemically respond to the particular complexity of this time.

From our perspective, this requires moving away from responding to complex issues through the dominant/primary strategies of ‘innovative solutions that can be scaled up and out’, and towards understanding that the solutions must also include re-patterning our systems around new and old/resurgent value systems and ways of working, and that this requires a deeper kind of change. To shift towards these different ways of working, transformational learning processes for the public sector that support ‘scaling deep’ are required. Scaling deep considers the specific histories and stories of people in place, underlying mindsets and mental models, and the power dynamics that underpin the current system, at entangled individual to system levels. Critical to this is going deep into the patterns that hold the status quo in place, (un)learning, making norms visible, and surfacing the values that those in the public sector hold about what ‘good solutions’ look like, for whom, and why. It means working in ways that have the capacity to critique, pause, and reset practice so that it begins to shift away from dominant paradigms, and from the notion of innovation as producing things/solutions, to innovation as learning and transformation. While such processes are well understood and established as part of transformative learning processes, there is a challenge in doing this within the contexts of innovation and innovation labs. Scaling deep is necessarily uncomfortable and requires an openness to disorientation, ambiguity, and not knowing. These ways of working and being sit in stark contrast to the characteristics of perfectionism, expertise, urgency, and narrow constructs of professionalism that are celebrated in the public sector (COCo Centre for Community Organizations Citation2019; DiAngelo Citation2018; Saad Citation2020).

This paper explores the role of PSI labs in enabling such transformative learning processes, moving away from the dominance of scaling up or out and towards integration of scaling deep. Labs are often expected to help develop innovations – discrete programmes, services, and solutions that can be scaled out and up for impact – which can inadvertently play into the current paradigm of governance by reinforcing dominant norms. This paper challenges that expectation, presenting a different idea about the potential of PSI labs. It investigates the role of PSI labs to support learning, and specifically transformative learning for scaling deep, as a means to help shift the capabilities and capacities of the public sector at individual and systems levels. To do this, we draw first on literature related to PSI labs, learning, and scaling. We then share insights resulting from action research of two labs that are grappling with the complex and urgent issues of social and ecological justice and wellbeing. Working towards scaling deep through transformative learning emerged as a way of growing the groundwork for thoughtful learning systems in both cases, and the stories of their evolution illustrate new ways to think about the potential roles and responsibilities of PSI labs. SLab (Vancouver) and The Lab (Tāmaki/Auckland) work in similar policy domains to one another, share a deep entanglement with Indigenous and anti-oppressive theory and purpose in their lab work, and in recent years have moved into integrating innovation learning into their practice. At the same time they have approached their practice independently and differently from one another, making this a rich pair to describe, compare and offer insights to others who are interested in this approach to PSI lab theory and practice. The article closes with a discussion about a distinct PSI lab type focused on transformative learning and scaling deep, evaluating the impacts of this approach, six moves that PSI labs might make in order to scale deep through transformative learning, and how scaling deep, up, and out relate to one another.

Literature review

This section first outlines the relationships between PSI labs and learning as understood to date, and then suggests ways to expand and enhance this understanding through considering literature on adult learning and transformative learning theory. Lastly, it introduces some key definitions of scaling and their significance in public sector transformation work, drawing connections between transformative learning and scaling deep.

Public sector innovation labs

PSI labs, variously called policy labs, social innovation labs, service innovation labs, policy innovation labs, and (co)design labs are an innovation catalyst rapidly emerging internationally in the last 10–15 years, and in different types of public sector organizations (PSOs). They are created for a variety of reasons including digital transformation, improvements to citizen experiences, increasing efficiency and effectiveness, improving public or stakeholder engagement, sparking policy innovations, working towards ecological and social wellbeing, and generally adding public value (Blomkamp Citation2018, Citation2021; de Vries, Bekkers, and Tummers Citation2016; Ferreira and Botero Citation2020; Lewis Citation2021; McGann, Blomkamp, and Lewis Citation2018; Puttick, Baeck, and Colligan Citation2014; Tõnurist, Kattel, and Lember Citation2017; Wellstead, Gofen, and Carter Citation2021). Amidst this diversity, researchers and practitioners are attempting to articulate and codify aspects of this field-in-motion and have identified some commonalities, summarized here.

Carstensen and Bason (Citation2012) describe PSI labs as innovation catalysts for host organization(s) that assist in the exploration phase of innovation, helping to drive the unfreezing process of organizational change in collaboration with stakeholders, and in response to a range of innovation barriers that exist in the day-to-day activities of the public sector. PSI labs are protected spaces that have permission to work differently than the rest of the public service. They may sit within, alongside, or at the edge of their host organization and use a range of innovation processes including design, creativity, experimentation, user-centeredness, co-creation, and others not yet in common or broad use in the public sector (Carstensen and Bason Citation2012; de Vries, Bekkers, and Tummers Citation2016; Lewis Citation2021; Lewis et al. Citation2017; Lewis, McGann, and Blomkamp Citation2020; McGann, Blomkamp, and Lewis Citation2018; Puttick, Baeck, and Colligan Citation2014; Tõnurist, Kattel, and Lember Citation2017; Wellstead, Gofen, and Carter Citation2021). Some constraints facing PSI labs include lack of/changes to political or senior leadership, insecure or insufficient resourcing, fear/risk-intolerance and lack of the skills and competencies necessary to do this work well (Evans and Cheng Citation2021; Lewis Citation2021; Wellstead, Gofen, and Carter Citation2021).

Several PSI lab studies suggest that the structure of a lab as a discrete, purpose-built, niche innovation unit means that the rest of the organization may think innovation work is taken care of by that unit and thus maintain the status quo everywhere else (Carstensen and Bason Citation2012; Timeus and Gascó Citation2018; Zivkovic Citation2018). Lewis (Citation2021) says that ‘labs are unlikely to be capable of acting as a panacea for the difficult terrain of coming up with and implementing solutions in a publicly funded and publicly accountable space. As other system-level studies of public sector innovation have argued, what is needed is the tilting of whole systems towards new ways of working that will make them more open to innovation (Lewis, Citation2021)’ (p.250). This provokes a question for us about how PSI labs might attempt to grow their influence and impact beyond these niches and constraints, and tilt systems towards creating and sustaining these new ways of working. Some PSI labs are beginning to incorporate an intentional and skilful learning and capacity building purpose into their work in response, including the two PSI labs described in this article.

In summarizing the purpose and focus of different kinds of PSI labs, Cole (Citation2021) iterates upon other work in the field to offer the following typology of four different PSI lab archetypes, none of which quite describes the PSI labs of focus in this article:

Creative Platform. Focused on employee-oriented ideation processes that aim to create buy-in to trying new methods;

Innovation Unit. Focused on user-centred value creation and using a wider range of different innovation processes and methods;

Change Partner. Centering both users and the organization and working on transformation of core public sector organizational narratives and processes; and

Systemic Co-design. Works with complexity through systems practice and social innovation processes. Holds an orientation beyond government itself, recognizing that working with complex challenges requires collaboration and co-creation with multiple partners in ways that share power and responsibility.

Relationship between PSI labs, innovation, and learning

The connection between innovation and learning is not yet a widespread or common focus in PSI labs, and learning does not tend to be included in the framing of what innovation means in both theory and practice for a PSI lab. Timeus and Gascó (Citation2018) studied innovation labs at the city level and found that there was almost no academic research focused on the role that innovation labs play in increasing the innovation capacities of organizations in the public sector. Several studies have explored innovation competencies needed at the individual, organizational, and/or network scale, and they include: capabilities for idea generation; ambidexterity (working in both experimentation and exploitation modes); learning and knowledge management systems; intensity of technology use; and collaboration (Choi and Chandler Citation2015; Dockx et al. Citation2022; Gieske, van Buuren, and Bekkers Citation2016; Timeus and Gascó Citation2018). A small number of studies have explored the intersections between PSI labs and transformative learning and capacity building (de Vries, Bekkers, and Tummers Citation2016; Evans and Cheng Citation2021; Gieske, van Buuren, and Bekkers Citation2016; Gryszkiewicz, Lykourentzou, and Toivonen Citation2016; Ricard et al. Citation2017; Timeus and Gascó Citation2018; Tõnurist, Kattel, and Lember Citation2017). Yee et al. (Citation2019) gathered four frameworks for transformative learning and considered their potential integration into social innovation work (not labs specifically) as a promising pathway to increasing impact.

PSI lab practitioners are ahead of academic research into innovation and learning in some ways. They are generating frameworks, practices, activities, and evaluation approaches at the intersections of PSI labs and learning as they try to deepen practice and increase impacts (Barling-Luke Citation2019; Centre for Public Impact Citation2021; Ferrarezi, Brandalise, and Lemos Citation2021; Hagen and Tangaere Citation2023; Kaur et al. Citation2022; Leurs and Roberts Citation2018; Leurs, Gonzalez-Ortega, and Hidalgo Citation2018; McKenzie Citation2021; Paper Giant Citation2019). Some practitioners are thinking about learning at the individual, team, organizational, and systems/problem scales; others are using systems thinking to understand learning structures, processes, and mindsets/paradigms (Christiansen Citation2018; Leurs and Roberts Citation2018; Zivkovic Citation2018). At an even larger scale, recent work by the Centre for Public Impact (Citation2021) advocates for a shift of public sector focus towards human learning systems as an alternative to the dominant NPM governance paradigm. Literature from transformative learning offers a rich body of work to sharpen our thinking about the potential held by PSI labs in integrating a robust learning orientation to their approach and is explored next.

Transformative learning

Transformative learning transforms problematic frames of reference, habits of mind, perspectives, and assumptions that no longer serve a person or situation in order to make them more open, reflective, and able to change (Mezirow Citation2000; Taylor Citation2009). For PSI, the inner work of transformation is an essential consideration. These transformed persepectives are viewed as better, or more appropriate, because they are likely to be more socially conscious, interdisciplinary, multicultural, and grounded in critical responses to current problematic systems and structures (O’Sullivan et al. Citation2002). Omer et al. (Citation2012) describe transformative learning as both an individual and collective process that ‘entails shifts in perspective, perceptual lenses, core beliefs, schemas, mental models, and mindsets’ and that these ‘perceptual shifts enable individuals and systems to inhabit new, more complex and emergent landscapes’ (p.375).

Mezirow (Citation2000), further elaborated by others (Lichtenstein and Plowman Citation2009; O’Sullivan et al. Citation2002; Taylor Citation2009), describes stages in transformative learning processes, which include a disorienting dilemma, critical reflection, taking responsibility, exploring and testing, and then integrating this new learning. Heifetz offers the related idea of cultivating a productive zone of disequilibrium in order for transformative learning to happen, which involves creating challenging spaces and opportunities, but is mindful to carefully balance levels of stress and the capability for a productive and expansive response (Heifetz Citation1994; Heifetz, Grashow, and Linsky Citation2009). This work is necessarily uncomfortable, and many adults will resist or avoid the discomfort and thus (un)consciously inhibit their own development. In public sector contexts, civil servants are expected to be experts in their fields. The stakes involved with an openness to not-knowing, and of disorientation as a pathway to transformed ways of thinking and being, can feel very high. Omnipresent in public sector organizations are values and practices of professionalism, defensiveness, competition, conflict avoidance, perfectionism, and others that normalize behaviours, systems, and structures designed to de-escalate or avoid discomfort making transformative learning in this context challenging (COCo Centre for Community Organizations Citation2019; DiAngelo Citation2018; Saad Citation2020).

Melacarne and Nicolaides (Citation2019) connect these ideas about transformative learning to the design and enactment of learning processes that build competencies and capacities required for responding to increasingly complex, volatile, and uncertain challenges. They articulate the concept of generative learning, which catalyses new perspectives that lead to radical innovation and rapid transformation in the face of continuous disruption. This process of transformative and generative learning points to transformative spaces that PSI labs working in system-shifting spaces seek to create to wrestle and reckon with mindsets and value systems. We explore literature about scaling deep next, building upon these foundations from transformative learning.

Scaling deep

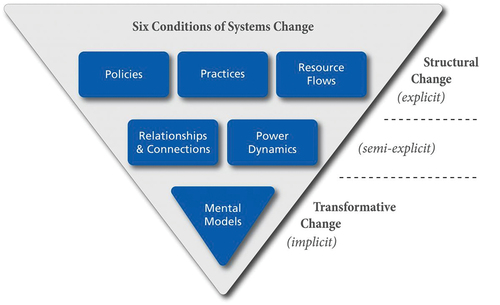

The conceptualization of scaling social innovations is helpful as a pathway for connecting literature about PSI labs and transformative learning. Social innovation seeks ways to profoundly change the basic routines, resource and authority flows or beliefs of the social system in which the innovation occurs with an aim of having durability and broad impact (Westley and Antadze Citation2010). Kania et al. (Citation2018) add that the shifting of policies, practices, resource flows, relationships and connections, power dynamics, and mental models are areas of focus for intervention in social innovation efforts ().

Figure 1. Six conditions of systems change (Kania, Kramer, and Senge Citation2018).

The concept of scaling in social innovation describes different potential pathways to growing the impact of a ‘successful’ social innovation from a small, niche experiment or prototype into products, processes, and programmes that are appropriate to, the specific contexts of people, place, and locality each PSI lab is working within. Moore, Riddell and Vocisano (Citation2015) offer a framework to describe different approaches to scaling social innovations ().

Figure 2. Pathways to scaling social innovation (Moore, Riddell, and Vocisano Citation2015).

Multiple approaches to scaling social innovations are often simultaneously underway and, at the same time, it is informative to understand these scaling pathways as distinct approaches that hold different potentials. Scaling up and scaling out have received the most attention in innovation efforts generally, and more specifically in social innovation initiatives, evaluation, and study. Scaling deep and its connection to transformative learning is our focus here. Scaling deep is about impacting cultural roots, values, and mindsets and the powerful roles that culture plays in shaping and changing the ways in which complex challenges are understood and acted upon. As Kania et al. (Citation2018) outline, while the tangible aspects of policies and resources, for example, are a critical part of shifting systems, the durable and sustaining work is the deeper, less tangible aspect of relationships and power dynamics that sit underneath that, and ultimately underpinning that, our mental models.

Some of the main documented strategies for scaling deep include spreading big cultural ideas, reframing stories to change beliefs and norms, and investing in transformative learning by sharing knowledge and practice through networks and communities of practice (Moore, Riddell, and Vocisano Citation2015; Riddell and Moore Citation2015). Tulloch (Citation2018) adds that scaling deep involves activations intended to promote transformation at the sociocultural level of individuals, organizations and/or communities. Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing scale deep (although it is not called this) into place, locality, people, history, and right relationships with humans and more-than-human kin (Goodchild Citation2021; Kimmerer Citation2013; Roussin Citation2020; Simpson Citation2017; Topa and Narvaez Citation2022; Yunkaporta Citation2019). Scaling deep focuses on the power in transforming culture, meaning, hearts, and minds to shift conditions and to transform paradigms.

Scaling deep is part of, and essential to, social innovation work that is durable and sustained, and the processes to get there necessarily involve transformative learning in people and systems. PSI labs working at the edges of the organizations and/or systems that they are working to change, can be in a marginal position, particularly as they become more transformative or disruptive to the usual ways of working (Geels Citation2011; Moore Citation2017). Scaling deep might offer a focus and intention of PSI labs towards nesting their work, practices, and thinking deeply into the people and culture of an organization, network, and system, and transformative learning offers a promising potential pathway here. The next section describes our methodology and the two PSI lab action research sites that have brought these concepts to life in practice.

Research method

This research used a critical qualitative research bricolage, with participatory action research (PAR) as the backbone method, applied here to explore the ways in which two PSI labs are working towards scaling deep through transformative learning in their theory and practice – The City of Vancouver Solutions Lab (SLab) and the Auckland Co-Design Lab (The Lab). These two labs were chosen for this study because: they are both working towards systemic transformation on complex social and ecological challenges; they are both developing and using scaling deep and transformative learning approaches in their lab practice; they are different enough (i.e. context, policy domains, team construction) to generate useful comparison and insights; and the teams work in documented ways that allow learning to be shared and compared.

Kincheloe et al. (Citation2017) say that ‘a critical research bricolage attempts to create an equitable research field and disallows a proclamation to correctness, validity, truth and the tacit axis of Western power through traditional research … Without proclaiming a canonical and singular method, the critical bricolage allows the researcher to become a participant and the participant to become a researcher’ (p. 253–4). Indigenous, feminist, and anti-oppressive methods were engaged by both SLab and The Lab in order to attempt to move beyond dominant Western paradigms of governance and of research, and into more transformative paradigms and processes of innovation (Brown Citation2017; Brown and Strega Citation2015; Cole Citation2021; Kemmis Citation2008; Kimmerer Citation2013; Kovach Citation2009; Simpson Citation2017; Smith Citation2016). A research bricolage approach allows for active entanglement of research and practice, and enables co-creation by researchers that hold standpoints about how PSI labs might improve their practice. This method also enables holding an aim of transformation while providing rigour and quality in ethics, process, and outcomes (Bradbury and Divecha Citation2020; Bradbury et al. Citation2019, Citation2019).

Reason and Bradbury (Citation2008) define action research as ‘a participatory process concerned with developing practical knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes. It seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern to people, and more generally the flourishing of individual persons and their communities’ (p.4). In PAR, research subjects become co-participants in the processes of inquiry which includes activities of generating questions and objectives, sharing knowledge, building research skills, interpreting findings, and implementing and measuring results. For many it is liberationist, and aims to address power imbalances typical of many Euro- and Anglocentric research approaches. The research design and context of each of the two action research sites, followed by descriptions of how each PSI lab moved towards an integration of scaling deep through transformative learning, is shared next.

Solutions lab (SLab) action research site

Research design

The PAR conducted with SLab was part of a larger, more formal university research project that went through research proposal, behavioural ethics review and approval, and research consent processes with action co-researchers at this site. This research took place between late 2016 and late 2020 and involved 32 co-researchers. Co-researchers and the co-author participated in various lab activities/PAR during the course of the research including strategic planning sessions, lab workshops focused on a variety of topics, learning journeys and community-based ethnographic research, prototype testing in the field, and reflection and evaluation sessions. Information and data were collected by the co-author through formal interviews, informal conversations, observation of lab activities, review of materials generated during lab processes, reflective and evaluative whole-group dialogues, and through cycles of action and reflection by the co-author. Emerging insights generated through this research were tested with action co-researchers prior to moving towards publication and knowledge mobilization.

Context

The Solutions Lab is a small and impermanent public sector social innovation lab inside the City of Vancouver, Canada. SLab was created in response to the growing pressures on municipal governments to face urgent and often intractable challenges such as affordability, climate change, growing inequity, and others and from within increasingly unpredictable, high-pressure, and complex environments (City of Vancouver Citation2018, Citation2022). SLab began in 2016, and brings people together in creative and experimental processes to seek transformative solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing Vancouver. Its work focuses on four priority policy domains: Greenest City/Climate Emergency; Healthy City; Reconciliation; and Equity.

Evolution toward scaling deep through transformative learning

After a promising first iteration of SLab from April 2017 – June 2018 which focused on designing and delivering time-bound innovation lab processes on four different complex challenges, developmental evaluation (Gamble Citation2008; Gamble, McKegg, and Cabaj Citation2021; Patton Citation2011) surfaced five recommended reframes relevant to scaling deep and transformative learning. These reframes included: (1) Shift from individual labs to growing innovation infrastructure; (2) Shift from expert-driven lab processes to a community of practice; (3) Fully integrate decolonization, inclusion, and equity into how innovation is understood and practiced; (4) Shift from focusing on discrete lab questions and challenges to a broader transformation orientation; and (5) Shift from a City-driven lab to multi-partner collaboration (City of Vancouver Citation2018). The evaluation found that if SLab remained solely focused on running short-term labs on discrete complex challenges and on cultivating a small ‘expert’ innovation team, the likelihood of having durable, lasting, transformative impact at personal, organizational, and systems levels was likely to remain quite limited over time. At the end of this iteration, it was clear that resources dedicated specifically to SLab were likely to remain scarce and unstable, and thus a different way of thinking about the lab was required if it was to be able to increase its impacts and influence.

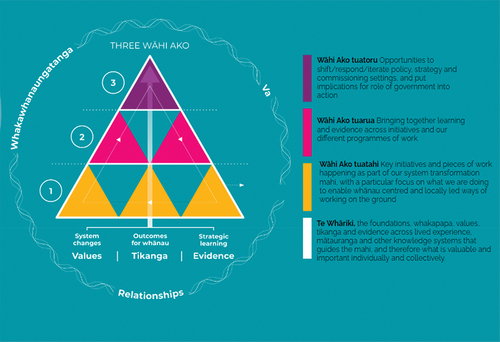

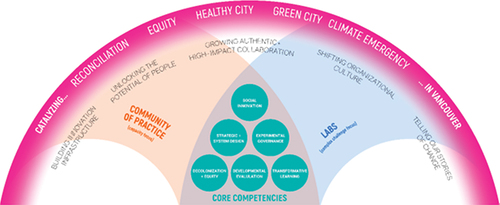

In response, a focus on scaling deep through transformative innovation learning was integrated into the theory of change () for the second iteration of SLab, which began in June 2018. This included articulating six core competencies being built through SLab work: social innovation; strategic and systemic design; experimental governance; decolonization and equity; developmental evaluation; and transformative learning. These core competencies were then integrated into the design and facilitation of each lab challenge, as well as by adding a community of practice (CoP) as a second major SLab activity. This CoP focused specifically on building competencies, capacities, and capabilities to shift paradigms, thinking, and practice of civil servants and community members (see Appendix for more detail about these activities).

Figure 3. Solutions lab 2.0 theory of change (City of Vancouver Citation2022).

Five hunches about scaling deep through integrating transformative learning were tested through experimentation and reflection/evaluation. The first was that this approach might result in more durable, interconnected, and extensive impacts than discrete, SLab-driven, shorter-term labs would be able to achieve on their own. Second, that a network of people involved with the labs and the CoP, and the competencies, capacities, and connections that they built with one another, might continue, spread, and grow beyond the boundaries of SLab work. The third possibility being tested was if shared language, vision, ambition for innovation, and a ladder for increasing engagement with PSI lab practice for people involved with SLab could be built. Fourth, this iteration tested if these innovation learning activities, and in particular, the CoP, might connect people together in ongoing relationships, across departments and teams, and co-create stronger capabilities, or enabling conditions, for their individual and shared innovation work. Finally, this cycle of PAR would attempt to establish and codify foundational theories and practices for transformative learning – the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of this approach – to integrate into the SLab theory of change in an ongoing way.

Auckland co-design lab (the lab) action research site

Research design

The Lab is a public sector learning and innovation unit nested inside local government and co-funded by central government agencies. They take an applied research approach that involves tracking impact, testing and localizing existing evidence, and developing new practice-based evidence out of documented and intentional learning loops. The team intentionally draws upon and relates their work to established literature and evidence and documents practice findings. They are not governed by a university ethics board but instead are guided by values and tikanga (cultural protocols) approach that draws upon established Māori ethics practice (Hudson et al. Citation2016), expertise of Māori practitioners and elders, and relevant academic, organizational, and legislative ethical guidelines. A rigorous approach to action research is supported through a culturally grounded and place-specific learning and evaluative practice, known as Niho Taniwha (more information in Appendix). Niho Taniwha supports learning in complex systems settings, embedding critical reflective practice into the team’s work, drawing on kaupapa Māori evaluation approaches and western systems change and social innovation practice (Tarena et al. Citation2021). It is designed specifically to support innovation, systems change, and learning in the context of Aotearoa New Zealand, and intentionally embeds cycles of learning, data gathering, analysis, and synthesis to track insights and impact. The Lab team is intentional about capturing and sharing learning through regular reflection sessions, reality testing with partners and collaborators, public practice sessions that bring together shared practice learning with other teams and communities, and codification of learning through blogs, papers, book chapters, and reports, all of which form the sources of information and data for this paper.

Context

The Lab was established in 2015 to address complex social and systems issues through participatory and design-led ways of working. The Lab’s remit is to help build the capability and readiness of the public sector to shift the norms and patterns of working that hold inequity in place. They do this by taking a local view with a systems lens – working with families, communities, and other system partners to understand and demonstrate the conditions (e.g. policy, practices, resource flows, mindsets) for equity and intergenerational wellbeing, and to model and promote investment in the social and cultural infrastructure and ways of working that enable this. They do this in partnership with The Southern & Western Initiative (TSI/TWI), a place-based socio-economic transformation unit focused on prosperity for communities in South and West Auckland. These communities are culturally rich, youthful, innovative and diverse. They are also sites of historic land confiscation, structurally racist policies, and underinvestment and Māori and Pacific communities living there experience the burden of ongoing inequity and colonization.

Evolution toward scaling deep through transformative learning

The Lab was initiated around a series of co-design challenges as a means to address complex socio-economic issues. Staff from different agencies joined with community and other systems partners in a co-design team to innovate around child wellbeing, youth employment, and driver licencing. The Lab also ran co-design master classes and experiences. This first phase demonstrated the value of taking a more participatory and systemic perspective, but also that this was not enough to bridge the gap between design concepts, recommendations, and reality, or to shift system behaviours in a sustainable way. There had been learning at an individual level for team members involved in the process, but that was not necessarily transferable into wider organizational/agency values or decision-making processes. More problematic was that co-design practices initially promoted by The Lab were also grounded in western concepts, and while seeking to address inequity was actually also perpetuating colonial approaches and mindsets (Mark and Hagen Citation2020).

The later phases of The Lab moved away from a focus on co-design methods towards the conditions for power-sharing, and for building the capacity and readiness in the system to work differently. A critical part of this was working alongside Indigenous colleagues from TSI (such as Angie Tangere and Anna Edwards) who were deepening social innovation practice from a cultural perspective, aligning practices to Māori and Pacific ways of being, and ensuring processes intentionally lead with, prioritized, and re-balanced power through centring Indigenous practices. The Lab also adopted a shared leadership model, reflecting the partnership intended through Te Tiriti o Waitangi.Footnote1

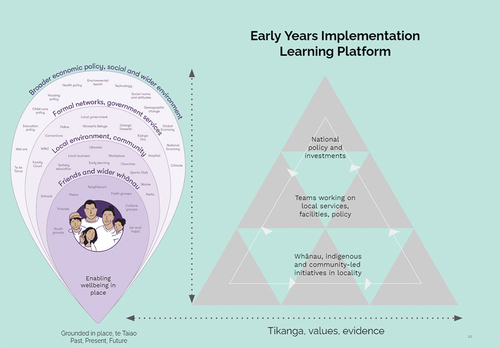

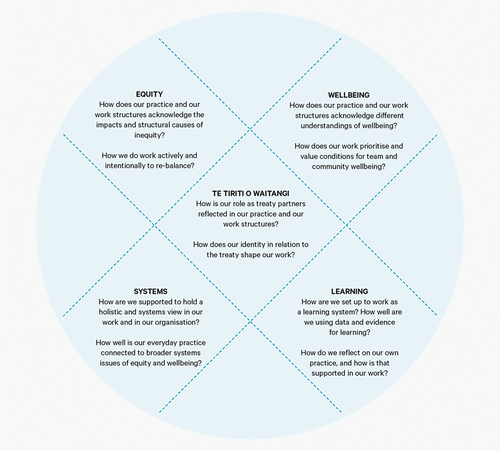

They also shifted to learning programmes that were deliberately focused on scaling deep, supporting teams to surface and grapple with fundamental mindsets and practices within the public sector and to become more critical around how these perpetuate inequity or enhance equity. This often revealed a conflict between personal values and the values on which the system operates. It also helped equip practitioners and teams with the means to disrupt these foundations and to identify ways to prioritize other mindsets and practices as a contribution towards equity and transformational change of the system. The Foundations Wheel () represents key areas of these programmes. There was also a shift away from discrete innovation projects or prototypes, towards embedding longer term, ongoing, implementation learning processes that would create the space for learning at practitioner and systems level and for scaling deep as part of implementation.

Figure 4. Foundations wheel describing foundations of the lab programs (Auckland Co-Design Lab Citation2022).

These shifts in The Lab approach reflect the understanding that what is necessary for systems transformation to address equity and wellbeing in Aotearoa is a deep shift in: (a) the assumptions, values, and worldviews which underpin decision-making; (b) the approach to resourcing, funding, and monitoring; (c) the acknowledgement of, and the space and time to unlearn and grapple with, racist, colonial, and monocultural practices; and (d) the rebalancing of power and reconfiguration of mindset, policy, and infrastructure away from replication and scaling out, towards place-based and culturally grounded approaches that better reflect the rights of First Peoples and the cultural context and communities in Aotearoa. Further details about the specific programmes and how these ways of working have been implemented can be found in the Appendix.

Discussion

In reflecting on what, we have learned across these two case studies, the discussion addresses four key ideas. First, an introduction of a fifth typology to the four PSI typologies outlined earlier. Second, how the impacts of scaling deep and transformative learning might be evaluated and tracked. Third, six moves that PSI labs might take in order to increase the impacts of their scaling deep and transformative learning work. Lastly, the relationship between scaling deep and scaling out and up.

PSI typologies

In the literature section, we shared four PSI lab typologies offered by Cole (Citation2021): (1) Creative Platform; (2) Innovation Unit; (3) Change Partner; and (4) Systemic Co-design. Our shared reflection on the purpose and actions of SLab and The Lab suggests a fifth PSI lab typology and purpose that integrates, grows from, and is different from these previous generations of labs: (5) Transformative Learning and Scaling Deep. This typology is about growing the capacity of individuals, relationships, and the system to hold the complexities of working deeply through transformative learning processes. It focuses on the challenging work of transformation internally (hearts, minds, paradigms) and externally (systems, power, culture) together. This typology is important to define and recognize because it directs our understanding of PSI labs towards a different set of purposes, outcomes, and impacts than earlier lab iterations. This fifth typology stays entangled with acting, learning, inquiring, and evaluating in ongoing cycles. It moves beyond working on discrete challenges in time-bound ways, into much broader challenge framing, a more spacious sense of time, and an acknowledgement that impacts and outcomes will likely take longer to be realized and be difficult to measure. Boundaries of what is/not the ‘lab’ become less clear and more embedded throughout people, organizations, and systems. As noted in the following section, this understanding of PSI lab work, outcomes, and impacts demands a different approach to tracking impact or evaluation than more conventional programmatic approaches.

Evaluating impacts of scaling deep and transformative learning

Working in complex systems change never has neat cause–effect relationships. Deep work takes time to fully take root and grow, with ripple effects that can and should appear for many years to come. This means that evaluating impacts in this PSI lab context is different to conventional public sector approaches to measurement. It relies more on tracking shifts and looking for signals or tohu (signs) of change. While the two PSI labs studied here had different processes for evaluating and tracking impacts, both drew on developmental evaluation methods of ongoing cycles of action, reflection, learning, and iteration to generate an understanding of the impacts of scaling deep and transformative learning. Both labs looked for and tracked evidence on shifts at both personal and organizational/systems levels. Examples of these are described here drawing from across both cases, and noting that this is not an exhaustive list of impacts.

Personal level: practitioner capabilities, practices, mindsets

The building/growing of new mindsets and then skilfully applying these to future projects and work beyond what happened in the lab. For example: holding complexity and equity lenses and confidently examining not just what teams are doing, but why, how, and for whom.

Increased comfort with uncomfortable conversations and ability to create room for these conversations as being part of the work. For example: interrogating what allyship looks like, and recognizing and addressing racism.

Adoption of new paradigms, ways of working, practices, and tools that allow other ways of being, knowing, and acting. For example: learning and adoption of Indigenous tools and frameworks in public sector innovation work.

Working at the root causes of systemic challenges when designing processes, projects, services, programmes, and other interventions. For example: active questioning in the work around default patterns/approaches to how work is framed, scoped, managed, and commissioned.

Organizational and systems levels: policies, resources, infrastructures

Shifts in policy and policy language, programme and service descriptions, plans, and other organizational artefacts to reflect what is surfacing through the learning and transformative processes catalysed by the lab. For example: Centering Indigenous history, place, culture, contexts, and ways of knowing and being, and the experiences of systemically excluded communities in plans and policies focused on social and ecological wellbeing.

Distributed leadership and relationships in public sector innovation beyond the boundaries of the lab. For example: rich, authentic, and impactful collaborations between the public sector and partners in community in ways that share power, decision-making, and resources.

Investment in learning infrastructure, spaces, and opportunities that support and encourage teams and organizations to grapple with the issues, discomforts, and the challenging conversations as part of a renewed ‘business as usual’ of government (not separate to it). For example: creation of communities of practice inside the public sector that are focused on learning, practicing, and building shared competencies, capacities, and capabilities for civil servants to work differently on complex, systemic challenges.

Active work to connect lived experience and expertise of communities into policy processes, including recognition of place and importance of localization. For example: evidence of civil servants working directly and reciprocally with people whose experiences a policy or programme is trying to improve as it is in development.

Growing a more critical understanding of how measures and indicators are developed and used, and whose values and ideas of ‘good’ they represent. For example: moving away from external or deficit indicators defined by government to wellbeing outcomes that are informed by community values.

Six moves for PSI labs when focused on transformative learning and scaling deep

The following six moves offer potential ways for PSI labs to increase the impacts of their scaling deep and transformative learning work. These moves were generated and articulated through PAR activities designed to experiment with and explore theory and practice of scaling deep and transformative learning within each of the action research sites. Alongside these activities, the authors engaged in generative dialogue, action, and reflection as we found shared patterns, meaning, and insights across the two research sites.

Move 1: Some of the attributes associated with a lab must become more diffuse. When a lab is seeking to catalyse, support, or create space for transformative learning and scaling deep the boundaries of the lab will be less clear. The lab team is likely to be working in allyship with other public sector transformation work such as equity, anti-racism, reconciliation, decolonization, and sustainability. The goal will be to support and create space for innovation leadership and learning throughout the system so that existing practices, relationships, and power dynamics are exposed, challenged, and shifted. Power and expertise will be shared and recognized as sitting with all of those involved, rather than held closely by an expert lab team. To achieve this collective approach, the theories, tools, and techniques that underpin the approaches of PSI labs will necessarily draw from a broader range of fields than other lab typologies.

Move 2: The paradigm, power structures, and practices embedded in dominant forms of western, colonial, and New Public Management (NPM) governance must become a focus of the transformation work, and are questioned, engaged with, and re-imagined in order to scale transformative innovation deeply. Many PSI labs shy away from engaging directly with governance paradigms as a place for innovation; however, the very fibres of NPM define evidence and value, set standards of professional practice, set policy-making and budgeting processes, define who is an ‘expert’ and whose ways of knowing and being are ‘legitimate’, determine measurement and monitoring practices, and many other core government functions. Scaling deep and transformative learning will challenge these core tenets of governance and explore them as sites of innovation in order to increase the depth, breadth, and potential impact of innovation work in ways that expand outside/beyond dominant paradigms.

Move 3: The work of PSI and labs must be rooted and located in context and be informed by the history and stories of people and their relationships to place. PSI work is not generic or context-agnostic, even though innovation practitioners may wish for helpful shortcuts and replicable pathways already travelled by others. Although there are helpful shared approaches to PSI lab work, it is important to be in specific, deep, reciprocal, and right relationship with people, history, and place. These relational dimensions of context influence lab starting points and approaches – there is specificity about what needs to be challenged and dismantled, and what needs to be built and emerge, in the everyday processes and practices of government in each unique place. The transformative learning dimension to this move includes supporting public sector practitioners who are used to working in the abstract (e.g. with aggregated population-level views that can disconnect from human scales) to instead also begin to work with the specificity of people, place, and history as an active and foundational dimension of transformation. This means taking a focus on ways of being, doing, and working more than on techniques, tactics, or outcomes.

Move 4: PSI labs must move more fully into the spaces and opportunities of implementation in order to scale deep and to increase both short- and longer-term impacts of their work. PSI labs have generated a great deal of novelty, creativity, energy, and had some successes with dislodging stuck thinking and systems as an attempt to open up people, spaces, and opportunities for change. There is a risk that these shifts stay in the prototyping space or on the edges of business as usual practice. The learning by doing approach of labs needs to occupy the space of ‘implementation learning’ in order to ensure it is really grappling with the surrounding systems conditions that hold the status quo in place. A key role of labs is to help public sector teams take the good intent of policy and strategy and contend with what it takes to see transformative policy and strategy fully implemented in practice. The dominant system pushes back hardest in this move to implementation of transformative interventions because the stakes are higher. This is when the potential for more significant shifts arise – when there is a move away from experiments, policy, and ideas and into scaling deep into infrastructure, mental models, operating models, programs, budgets, and job descriptions.

Move 5: Public sector innovators must grow into the role of learning partners to support deep process and practice. PSI lab archetypes 1–4 tend to tackle complex issues in isolation as discrete challenge spaces, using specific innovation processes and methodologies. This approach does not result in shifting underlying structures, patterns, and mindsets that hold stuck challenges in place across a system/organization. Thus, the idea of ‘innovation projects to address a complex issue’ can actually act as a distraction from really wrestling and reckoning with deeper issues. Public sector innovators, PSI labs, and the people that commission innovation work can get caught up in cycles of initiatives that look like they are attending to the issues but are only shallow in reach. This tends to be because they have agency and permission in this realm, can build confidence in their abilities and reputations as experts, and can feel like they are doing something helpful. Deep process and practice work holds space for capacity and capability development, relationship and movement building, and reflection and reckoning with the ways that power and privilege shape perspectives and approaches. This type of process work calls us in to be vulnerable, challenge biases and assumptions, undo and unlearn that which no longer serves, have courageous conversations, and create mutual accountability, responsibility, and hope for transformation.

Move 6: Understanding, measuring, and telling stories of impact, outcomes, and transformation must include multiple ways of knowing. The public sector is often stuck in measuring the impacts of their work using dominant evidence frameworks and practices, which connects back to dominant paradigms of governance. Measuring the impacts of innovation work that aims to scale deep through learning and work towards transformation will not be able to adequately tell its story through this limited lens. Relational, values-led, narrative, and place-based practices of understanding impact with intentional inclusion of multiple evidence bases, knowledges, and lived experiences are possible and necessary. Different signals of change and transformation, as shown in the examples above, are tracked over time. There is a rich and robust set of qualitative and participatory research methods that can lend themselves to understanding impacts, and innovation in the public sector needs to harness these in the service of telling their stories of scaling deep, learning, and transformation so that this work is more visible, understood, and acknowledged.

Scaling deep in relationship to scaling up and out

The intent of this article is to immerse in the unique possibilities and potential of scaling deep as under examined in public sector social innovation work; this includes how it is entangled with the other scaling types from . The public sector, including PSI labs, tends to focus on scaling out (i.e. replication or increasing in reach of services, interventions, and programmes) and scaling up (i.e. changing policies, rules, roles, decision-making structures). Skillful consideration and integration of scaling deep alongside these approaches means that the systemic impacts of the overall innovation effort are likely to be much greater. In other words, scaling up and out will look different, and will realize different impacts, when scaling deep is part of the strategy. This is because scaling up and out do not typically contend with the deeper layers of systems change efforts including mindsets, paradigms, values, power, and relationships that may fundamentally change the direction, value base, or intent of policy or programme approaches. For example, in an initiative supported by The Lab, the process of scaling deep with communities to learn about activating child wellbeing led to a shift in how the agency understood the role of scaling out, focusing on scaling the conditions for wellbeing in the community, rather than on scaling specific programmes or services.

By making time and space for scaling deep alongside scaling up and out, it is much more likely that an innovation effort will be more challenging to the status quo. If scaling up, out, and deep are happening together, the process and outcomes are different, more fundamental, harder, and disruptive. Scaling deep can reconceptualize what scaling up and out might look like, and what scaling approaches – together – aim to achieve. For PSI labs, more specifically, inclusion of scaling deep approaches means that experiments and prototypes have the possibility of scaling into changing hearts and minds and into the deep social infrastructures and values of the public sector that then shape governance strategies, commissioning/procurement and investment approaches, approaches to sharing power and collaborations, and operating models for budgets, programme delivery, job descriptions, and the like. An example of the interplay of these types of scaling is social/ethical/sustainable procurement in the public sector. Scaling up focuses on establishing policies and decision-making processes and protocols for these shifts in procurement. Scaling out expands social procurement across multiple departments, teams, and even organizations. Scaling deep connects to the values and purposes of the work, including the learning-related aspects of this work, where staff are supported to understand why this is important, see how their individual actions can make a difference, and are encouraged to lead and innovate in their own contexts. Without this final aspect of scaling that helps people align to the value of social procurement and why it is important, other scaling efforts may exist in principle but are not fully activated or prioritized.

Some limitations of scaling deep in a PSI lab context are that activities and impacts can be less visible, and they can be much harder to measure and demonstrate value in standard ways (i.e. KPI’s). It can become less clear what the work of the lab is about as it tends to move away from running distinct time- and problem-bound innovation processes and towards intervening in governance processes and the systems and structures of power and in activities like professional development, organizational management/change, project management, public engagement, and human resource management. Another limitation is that it often pushes at the edges of peoples’ tolerance levels and readiness for transformation, resulting in push back, resistance, and conflict. Scaling deep surfaces what it really takes to work differently, which can expose difficult truths about things that the public sector tends to hide or avoid, for example, the amount of time it actually takes to make real progress on complex challenges, the kinds of risks that are and are not tolerated, the critical nature of building trust-based relationships and how often this is short-cutted or harmed, how ego shows up in public sector work, and the various ways that civil servants have to game the dominant systems and approaches to work systemically, equitably, and relationally. Scaling deep can be harder for some people but also easier, more aligned, and integrous for many others even though it is rarely centred as a valid and valued way of being and working in the public sector.

Conclusion

The potential of scaling deep through transformative learning points towards the need for thoughtful learning systems within the public sector to support transformation towards different ways of working, knowing, and being at the individual, relational, and systems scales. By articulating a PSI lab typology focused on scaling deep through transformative learning and by sharing lessons from two cases to describe six moves for PSI labs interested in scaling deep and transformative learning to make, this article generalizes and makes available ways for researchers and practitioners to further theorize and enact this approach to public sector innovation.

This research has also generated questions for further inquiry. Instead of envisioning and shaping a lab as a discrete, protected, special place guided by the work of experts in a specific set of practices, what if the construct of ‘lab’ was re-imagined? What if Labs were thought of as diffuse, boundary-less throughout the sector, taking the form of shared practices and deep commitments to collectively work towards transformation of what it means to be of service in the public sector, in these times? What if labs were part of an ecosystem of transformation, and in allyship with the other major forces disrupting the public sector at this time, for example reconciliation, anti-racism, equity, and climate change? These (and other) questions are important to continually inquire into because we need to grow our abilities to move from aspiration to implementation of transformation within the public sector and develop capacities to grapple with the challenges we find when we do this. We hope the insights offered here, drawing upon literature and practice, help to move forward ideas of innovation and in particular social innovation aimed at transformative change for social and ecological justice and wellbeing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Recognised as Aotearoa New Zealand’s founding document signed as a partnership between some Māori tribes and the Crown.

References

- Auckland Co-Design Lab. 2022. “Practice Foundations: Hautū Waka.” https://www.aucklandco-lab.nz/resources-summary/hautu-waka.

- Barling-Luke, N. 2019. “Changing Mindsets: The Policy Lab’s Evaluation of Our Programme.” https://states-of-change.org/stories/changing-mindsets-policy-labs-evaluation-of-our-programme.

- Bason, C. 2010. Leading Public Sector Innovation: Co-Creating for a Better Society. Portland, OR; Bristol, UK: Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qgnsd.

- Bason, C. 2017. Leading Public Design: Discovering Human-Centred Governance. Bristol, UK; Chicago, USA: Policy Press.

- Bason, C., and R. D. Austin. 2022. “Design in the Public Sector: Toward a Human Centred Model of Public Governance.” Public Management Review 24 (11): 1727–1757. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1919186.

- Bencio, C. 2018. “An Open Letter to Converge Participants.“ Personal communication.

- Blomkamp, E. 2018. “The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 77 (4): 729–743. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12310.

- Blomkamp, E. 2021. “Systemic Design Practice for Participatory Policymaking.” Policy Design and Practice 5 (1): 12–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2021.1887576.

- Boukamel, O., and Y. Emery. 2017. “Evolution of organizational ambidexterity in the public sector and current challenges of innovation capabilities.” The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal 2 (22).

- Bradbury, H., and S. Divecha. 2020. “Action Methods for Faster Transformation: Relationality in Action.” Action Research 18 (3): 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750320936493.

- Bradbury, H., K. Glenzer, B. Ku, D. Columbia, S. Kjellström, A. O. Aragón, R. Warwick, et al. 2019. “What is Good Action Research: Quality Choice Points with a Refreshed Urgency.” Action Research 17 (1): 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750319835607.

- Bradbury, H., S. Waddell, K. O’ Brien, M. Apgar, B. Teehankee, and I. Fazey. 2019. “A Call to Action Research for Transformations: The Times Demand It.” Action Research 17 (1): 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750319829633.

- Brookfield Institute. 2018. Exploring Policy Innovation. Canada: Brookfield Institute for Innovation Entrepreneurship.

- Brown, a. m. 2017. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico, CA: AK Press.

- Brown, L., and S. P. Osborne. 2013. “Risk and Innovation.” Public Management Review 15 (2): 186–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.707681.

- Brown, L. A., and S. Strega. 2015. Research as Resistance: Revisiting Critical, Indigenous, and Anti-Oppressive Approaches. Second ed. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Carstensen, H., and C. Bason. 2012. “Powering Collaborative Policy Innovation: Can Innovation Labs Help?” Innovation Journal 17 (1): 1–26.

- Centre for Public Impact. 2021. “Human Learning Systems: Public Service for the Real World.” https://www.centreforpublicimpact.org/assets/documents/hls-real-world.pdf.

- Choi, T., and S. M. Chandler. 2015. “Exploration, Exploitation, and Public Sector Innovation: An Organizational Learning Perspective for the Public Sector.” Human Service Organizations, Management, Leadership & Governance 39 (2): 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2015.1011762.

- Christiansen, J. 2018. “Developing an Impact Framework for Cultural Change in Government.” https://states-of-change.org/stories/developing-an-impact-framework-for-cultural-change-in-government.

- City of Vancouver. 2018. “Navigating Complexity: The Story of the Solutions Lab.” https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/navigating-complexity-solutions-lab.pdf.

- City of Vancouver. 2022. “Tending to What We Want to Grow: Continuing on the Journey of Vancouver’s Solutions Lab.” https://vancouver.ca/solutions-lab.

- COCo (Centre for Community Organizations). 2019. “White Supremacy Culture in Organizations.” Accessed December, 2020. https://coco-net.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Coco-WhiteSupCulture-ENG4.pdf.

- Cole, L. 2021. “A Framework to Conceptualize Innovation Purpose in Public Sector Innovation Labs.” Policy Design and Practice 5 (2): 164–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2021.2007619.

- Considine, M., and J. M. Lewis. 2007. “Innovation and Innovators Inside Government: From Institutions to Networks.” Governance 20 (4): 581–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00373.x.

- de Vries, H., V. Bekkers, and L. Tummers. 2016. “Innovation in the Public Sector: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda.” Public Administration 94 (1): 146–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12209.

- DiAngelo, R. 2018. White Fragility: Why It’s so Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Boston, Mass: Beacon Press.

- Dockx, E., K. Verhoest, T. Langbroek, and J. Wynen. 2022. “Bringing Together Unlikely Innovators: Do Connective and Learning Capacities Impact Collaboration for Innovation and Diversity of Actors?” Public Management Review 0 (0): 1–24. on-line first. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.2005328.

- Evans, B., and S. M. Cheng. 2021. “Canadian Government Policy Innovation Labs: An Experimental Turn in Policy Work?” Canadian Public Administration 64 (4): 587–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/capa.12438.

- Ferrarezi, E., I. Brandalise, and J. Lemos. 2021. “Evaluating Experimentation in the Public Sector: Learning from a Brazilian Innovation Lab.” Policy Design and Practice 4 (2): 292–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2021.1930686.

- Ferreira, M., and A. Botero. 2020. “Experimental Governance? The Emergence of Public Sector Innovation Labs in Latin America.” Policy Design and Practice 3 (2): 150–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1759761.

- Gamble, J. A. A. 2008. A Developmental Evaluation Primer. McConnell Family Foundation. https://mcconnellfoundation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/A-Developmental-Evaluation-Primer-EN.pdf.

- Gamble, J. A. A., K. McKegg, and M. Cabaj 2021. “A Developmental Evaluation Companion.” McConnell Family Foundation. https://mcconnellfoundation.ca/the-developmental-evaluation-companion-now-available/.

- Geels, F. W. 2011. “The Multi-Level Perspective on Sustainability Transitions: Responses to Seven Criticisms.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 1 (1): 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.002.

- Gieske, H., A. van Buuren, and V. Bekkers. 2016. “Conceptualizing Public Innovative Capacity: A Framework for Assessment.” Innovation Journal 21 (1): 1–25.

- Goodchild, M. 2021. “Relational Systems Thinking.” Journal for Awareness Based Systems Change 1 (1): 75–103. https://doi.org/10.47061/jabsc.v1i1.577.

- Gryszkiewicz, L., I. Lykourentzou, and T. Toivonen. 2016. “Innovation Labs: Leveraging Openness for Radical Innovation?” Journal of Innovation Management 4 (4): 68–97. https://doi.org/10.24840/2183-0606_004.004_0006.

- Hagen, P., and A. Tangaere. 2023. “forthcoming). Practice-Based Evidence for Social Innovation: Working and Learning in Complexity.” In The Routledge Companion to Design Research, Y. Akama and J. Yee edited by, 429–441. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003182443-37.

- Hartley, J., E. Sørensen, and J. Torfing. 2013. “Collaborative Innovation: A Viable Alternative to Market Competition and Organizational Entrepreneurship.” Public Administration Review 73 (6): 821–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12136.

- Heifetz, R. A. 1994. Leadership without Easy Answers. London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674038479.

- Heifetz, R., A. Grashow, and M. Linsky. 2009. The Practice of Adaptive Leadership. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business Press.

- Hudson, M., M. Milne, K. Russell, B. Smith, P. Reynolds, and P. Atatoa-Carr. 2016. “The development of guidelines for indigenous research ethics in Aotearoa/New Zealand.” In Ethics in Indigenous Research, Past Experiences – Future Challenges, edited by A.-L. Drugge, 157–174. Umea, Sweden: Vaartoe Centre for Sami Research, Umea University.

- Jones, P. H. 2014. “Systemic Design Principles for Complex Social Systems.” In Social Systems and Design, edited by G. S. Metcalf, 91–128. Tokyo: Springer Japan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54478-4_4.

- Kania, J., M. Kramer, and P. Senge. 2018. The Water of Systems Change. FSG. https://www.fsg.org/resource/water_of_systems_change/.

- Kaur, M., H. Buisman, A. Bekker, and C. McCulloch. 2022. “Innovative Capacity of Governments: A Systemic Framework.” OECD Working Papers on Public Governance No. 51. https://doi.org/10.1787/52389006-en.

- Kemmis, S. 2008. “Chapter 8: Critical Theory and Participatory Action Research.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, edited by P. Reason and H. Bradbury, 18. London: Sage Publications.

- Kieboom, M. 2014. Lab Matters: Challenging the Practice of Social Innovation Laboratories. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Kennisland.

- Kimmerer, R. W. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions.

- Kincheloe, J. L., P. McLaren, S. R. Steinberg, and L. D. Monzo. 2017. “Chapter 10: Critical Pedagogy and Qualitative Research - Advancing the Bricolage.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. Lincoln. 5 ed, 40. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Kovach, M. 2009. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

- Leurs, B., P. Gonzalez-Ortega, and D. Hidalgo. 2018. Experimenta: Building the Next Generation of Chile’s Public Innovators. London, UK: Nesta, Laboratorio de Gobierno & ProChile.

- Leurs, B., and I. Roberts. 2018. Playbook for Innovation Learning. Nesta, UK: Innovation Foundation.

- Lewis, J. M. 2021. “The Limits of Policy Labs: Characteristics, Opportunities and Constraints.” Policy Design and Practice 4 (2): 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1859077.

- Lewis, J. M., M. McGann, and E. Blomkamp. 2020. “When Design Meets Power: Design Thinking, Public Sector Innovation and the Politics of Policymaking.” Policy & Politics 48 (1): 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557319X15579230420081.

- Lewis, J. M., L. M. Ricard, E. H. Klijn, and T. Ysa. 2017. Innovation in City Governments: Structures, Networks and Leadership. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315673202.

- Lichtenstein, B. B., and D. A. Plowman. 2009. “The Leadership of Emergence: A Complex Systems Leadership Theory of Emergence at Successive Organizational Levels.” The Leadership Quarterly 20 (4): 617–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.04.006.

- Mark, S., and P. Hagen. 2020. Co-Design in Aotearoa New Zealand: A Snapshot of the Literature. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland Co-design Lab.

- McGann, M., E. Blomkamp, and J. Lewis. 2018. “The Rise of Public Sector Innovation Labs: Experiments in Design Thinking for Policy.” Policy Sciences 51 (3): 249–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9315-7.

- McGann, M., T. Wells, and E. Blomkamp. 2021. “Innovation Labs and Co-Production in Public Problem Solving.” Public Management Review 23 (2): 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1699946.

- McKenzie, F., 2021. “Building a Culture of Learning at Scale: Learning Networks for Systems Change.” Orange Compass for the Paul Ramsay Foundation. https://www.orangecompass.com.au/images/Scoping_Paper_Culture_of_Learning.pdf.

- Melacarne, C., and A. Nicolaides. 2019. “Developing Professional Capability: Growing Capacity and Competencies to Meet Complex Workplace Demands.” New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education 2019 (163): 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20340.

- Mezirow, J. 2000. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Moore, M. 2017. “Chapter 12: Synthesis - Tracking Transformative Impacts and Cross-Scale Dynamics.” In The Evolution of Social Innovation, F. Westley, K. McGowan, and O Tjörnbo. edited by. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786431158.00017.

- Moore, M.-L., D. Riddell, and D. Vocisano. 2015. “Scaling Out, Scaling Up, Scaling Deep: Strategies of Non-Profits in Advancing Systemic Social Innovation.” The Journal of Corporate Citizenship 2015 (58): 67–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/jcorpciti.58.67.

- Omer, A., M. Schwartz, C. Lubell, and R. Gall. 2012. “Wisdom Journey: The Role of Experience and Culture in Transformative Learning praxis.” 10th International Conference on Transformative Learning Proceedings. Center for Transformative Learning, Meridian University, CA.

- O’Sullivan, E., A. Morrell, M. A. O’Connor, E. O’Sullivan, A. Morrell, and M. A. O’Connor. 2002. Expanding the Boundaries of Transformative Learning: Essays on Theory and Praxis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-63550-4.

- Paper Giant. 2019. “States of Change: The Journey of Learning Through Innovative Action.” https://medium.com/states-of-change/states-of-change-d49e5399778d.

- Patton, M. Q. 2011. Developmental Evaluation. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Puttick, R., P. Baeck, and P. Colligan. 2014. I-Teams: The Teams and Funds Making Innovation Happen in Governments Around the World. London, UK; New York, USA: Nesta and Bloomberg Philanthropies.

- Quayle, M. 2017. Designed Leadership. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Reason, P., and H. Bradbury. 2008. The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice (2 ed.).). London: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607934.

- Ricard, L. M., E. H. Klijn, J. M. Lewis, and T. Ysa. 2017. “Assessing Public Leadership Styles for Innovation: A Comparison of Copenhagen, Rotterdam and Barcelona.” Public Management Review 19 (2): 134–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1148192.

- Riddell, D., and M.-L. Moore 2015. “Scaling Out, Scaling Up, Scaling Deep: Advancing Systemic Social Innovation and the Learning Processes to Support It.” McConnell Foundation: https://mcconnellfoundation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ScalingOut_Nov27A_AV_BrandedBleed.pdf.

- Roussin, D. 2020. “Personal Communication.”

- Ryan, A., and J. Koh 2018. “Why Improvement Does Not Equal Innovation.” States of Change Blog Post, Accessed December, 2020. https://states-of-change.org/stories/why-improvement-does-not-equal-innovation.

- Saad, L. F. 2020. Me and White Supremacy. Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks.

- Scharmer, C. O. 2016. Theory U: Leading from the Future as It Emerges: The Social Technology of Presencing. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., a BK Business Book.

- Schulman, S. 2013. “A Lab of Labs.” Stanford Social Innovation Review August.

- Simpson, L. B. 2017. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. Minneapolis, Minn: University of Minnesota Press.

- Smith, L. T. 2016. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Second ed. London: Zed Books.

- Sørensen, E., and J. Torfing. 2011. “Enhancing Collaborative Innovation in the Public Sector.” Administration & Society 43 (8): 842–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399711418768.

- Tarena, E., P. London, A. Tangaere, P. Hagen, and R. Taniwha-Paoo. 2021. Kia Tipu Te Ao Mārama. The Auckland Codesign Lab, the Southern Initiative (Auckland Council). Auckland, New Zealand: Tokona Te Raki.

- Taylor, E. W. 2009. “1: Fostering Transformative Learning.” In Transformative Learning in Practice, edited by J. Mezirow and E. Taylor, 11. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Timeus, K., and M. Gascó. 2018. “Increasing Innovation Capacity in City Governments: Do Innovation Labs Make a Difference?” Journal of Urban Affairs 40 (7): 992–1008. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1431049.

- Tõnurist, P., R. Kattel, and V. Lember. 2017. “Innovation Labs in the Public Sector: What They are and What They Do?” Public Management Review 19 (10): 1455–1479. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1287939.