ABSTRACT

This qualitative case study examines how the tension between control and collaboration is managed in the relationship between a Network Administrative Organization (NAO) and the 40 inter-organizational service delivery networks it governs using a performance management system. We found that the relationship between the NAO and networks operated as a ‘dance’, with the NAO taking steps to collaborate with and control the networks. We identified three forms of network governance ambidexterity that characterize this dance – structural, goal, and behavioural – and propose a framework of their antecedents, stability, and influencing factors. Network governance ambidexterity may help explain network functioning and performance.

Introduction

Demand for more coordinated, efficient, and sustainable service delivery has contributed to a rise in purpose-oriented networks in the public sector, particularly in healthcare (Goodwin, Stein, and Amelung Citation2021). Purpose-oriented networks bring together three or more autonomous organizations to participate in a joint effort based on a common purpose (Carboni et al. Citation2019; Nowell and Kenis Citation2019). These networks enable member organizations to work collectively to address ‘wicked social problems’ that individual organizations cannot manage alone (O’Toole Citation1997). Organizations in such networks need to collaborate and coordinate their actions to achieve their common purpose. They also need to align goals, balance power, manage conflict, monitor performance, and hold members accountable for network-level outcomes (Kenis and Provan Citation2006; Maron and Benish Citation2022; Provan and Kenis Citation2008). Because member organizations are autonomous entities, traditional hierarchical methods of coordination and control are absent or weak in most purpose-oriented networks (Carboni et al. Citation2019). Therefore, network governance is required (Carboni et al. Citation2019; Provan and Kenis Citation2008).

‘Network governance’ refers to how joint action is coordinated and controlled in networks to ensure that network-level goals are achieved (Provan and Kenis Citation2008). Empirical research demonstrates that network governance is associated with network performance outcomes (Bitterman and Koliba Citation2020; Liu and Tan Citation2022). Network governance has structural and processual components. Structurally, networks may be governed collectively by the member organizations themselves (shared governance), by a single member organization that takes on a lead role (lead organization governance), or by an external organization known as a Network Administrative Organization (NAO governance) (Provan and Kenis Citation2008). Network governance also involves a range of processes including setting goals, allocating resources, enforcing contracts, establishing methods for communication and decision-making, instituting incentives, and monitoring network activities (Carboni et al. Citation2019; Popp et al. Citation2014). Often, these network governance processes are operationalized through a performance management system to support network goal achievement (Alonso and Andrews Citation2018; Koliba, Campbell, and Zia Citation2011).

Scholars highlight many tensions inherent in network governance (Berthod and Segato Citation2019; Provan and Kenis Citation2008). Ambidexterity has been proposed as a means to manage and balance tensions in network governance (Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2015). Ambidexterity refers to the ability to hold opposing ends of a tension simultaneously. Ambidexterity plays an important role in network governance and performance, but empirical studies of ambidexterity in this context are limited (Berthod et al. Citation2017, Bryson et al., Citation2008; Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2015). Scholars have called for more research on how network governance tensions can be managed and specifically on ambidexterity as a potential solution (Bryson et al., Citation2008; Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2015).

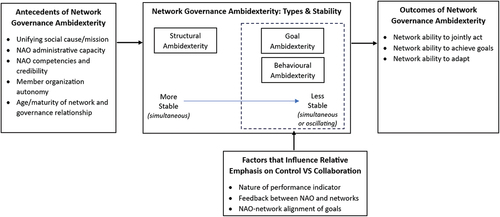

In this paper, we focus on a specific tension that must be addressed: the tension between control and collaboration. The very term ‘network governance’ exemplifies this tension with ‘network’ signifying collaboration and ‘governance’ signifying control (Provan and Kenis Citation2008). To examine this issue, we conducted a qualitative case study of a publicly-funded, mandated NAO and the 40 inter-organizational healthcare delivery networks it governs using a robust performance management system. Specifically, we asked, how do the NAO and networks manage the tension between control and collaboration in their relationship? Through interviews, document review, and observation, we found that the relationship between the NAO and the networks it governs operated as a ‘dance’ with the NAO taking steps to collaborate with the networks (as a supportive partner and mentor) and control the networks (as a forceful watchdog) over time and across performance management interventions. Similarly, the networks take steps to reinforce collaboration or control in their relationship with the NAO. We identified three forms of ambidexterity that characterize this dance: (1) structural ambidexterity, (2) goal ambidexterity, and (3) behavioural ambidexterity. In other words, elements of both control and collaboration were identified in codified contracts, standards, and processes of performance management (structural ambidexterity), perceived goals of performance management (goal ambidexterity), and in NAO and network interactions regarding performance management (behavioural ambidexterity).

This study makes three contributions. First, we find empirical evidence that networks led by a NAO can manage the tension between control and collaboration through ambidexterity. Second, we propose the construct of ‘network governance ambidexterity’ and develop a theoretical framework to explain this phenomenon and how it manifests in a simultaneous or oscillating pattern. This framework can be used to classify and compare network governance approaches, design complex network governance configurations capable of managing tensions, and, ultimately, help explain network functioning and performance. Third, we suggest that effective network governance ambidexterity requires certain contextual conditions, including a unifying social cause, strong NAO competencies, member autonomy, and a mature governance relationship.

Literature review

Formal structural versus informal behavioural network governance mechanisms

Network governance refers to the structures and processes used to coordinate and control joint action in a network and account for its activities (Provan and Kenis Citation2008; Vangen et al. Citation2015). Embedded in this definition are a range of concepts that span different fields, including networks, collaboration, control, and accountability. A core issue common to these fields is the tension between the formal and informal. The language used differs, but the underlying issue examined across these fields is the same: what are the roles of and interactions between the more formal, explicit, hierarchical, and structural dynamics of networks and the more informal, implicit, social, and behavioural dynamics? Formal network governance mechanisms refer to official and codified contracts, agreements, policies, and procedures that define roles, expectations, performance indicators, and other rules or mandates (Bauer, AbouAssi, and Johnston Citation2022). Informal network governance mechanisms refer to interpersonal and interorganizational interactions (Romzek et al. Citation2012). Both formal and informal governance mechanisms play a role in stimulating collaboration, maintaining order and control, ensuring accountability, and influencing performance in networks (Bryson et al. Citation2008, Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2015).

In general, networks governed by a shared model employ more informal governance mechanisms while those governed by lead organizations and NAOs rely on more formal mechanisms (Provan and Kenis Citation2008). Evidence suggests that some degree of formalization is necessary and that a lack of formal governance mechanisms generates role and task confusion, thereby stifling both accountability and collaboration (Babiak and Thibault Citation2009; Koliba, Zia, and Mills Citation2011; Lee Citation2022, Marques et al. Citation2011; Nylen Citation2007). Furthermore, embedding performance management, such as performance targets, in formal agreements is increasingly common (Koliba, Campbell, and Zia Citation2011; Marques et al. Citation2011) and associated with higher network or partnership performance (Alonso and Andrews Citation2018).

Scholars argue that less attention has been given to the informal behavioural dimension of network governance in comparison with the formal structural dimension (Romzek et al., Citation2012; Saz-Carranza and Ospina Citation2011). Two key types of informal governance mechanisms include shared social norms such as trust and reciprocity and facilitative behaviours such as information sharing and performing favours (Romzek et al. Citation2012, Romzek et al. Citation2014). Robust informal governance mechanisms reduce the need for formal mechanisms and are more likely to mitigate the challenges associated with working in networks than formal mechanisms (Marques et al. Citation2011; Romzek et al. Citation2014).

A few studies compare the relative influence of formal versus informal governance mechanisms in networks and partnerships. These studies suggest that informal network governance mechanisms are stronger determinants of goal congruence and/or network performance than formal governance mechanisms (Piatek et al. Citation2018; Romzek et al. Citation2014). These studies also acknowledge that formal and informal governance mechanisms co-exist but argue that tensions between formal and informal network governance mechanisms may arise such that the two work against each other (Romzek et al. Citation2014). Others suggest combining and/or switching between formal assertive and informal supportive modes of governance based on context and needs (Berthod et al. Citation2017; Koliba, Zia, and Mills Citation2011) – a point we return to in the next section.

A limitation of the literature on the formal and informal mechanisms of network governance is the assumption that the two can be easily distinguished and classified. We provide two examples relevant to our study to demonstrate this limitation. First, the literature treats lateral relationships and interactions among peer network member organizations as ‘informal’. The NAO, as an external organization providing oversight, is viewed as ‘formal’. However, this classification is based solely on the NAO’s structure; it fails to account for the NAO’s relationship and interactions with member organizations. The informal, behavioural aspect of the NAO-network dynamic is overlooked.

A second example is regarding performance management as a mechanism of network governance. Performance management is classified as a formal governance mechanism because it is typically codified and made official in written agreements. Yet, how performance management is enacted may not align with how it is codified on paper. In other words, even performance management entails both formal and informal aspects. In fact, in the literature on performance management, there is a tension between the formal, hierarchical, and compliance-oriented components of performance management needed for accountability (contracts and indicators) and the informal, socializing, learning-oriented components needed for improvement (norms, relationships, and dialogue) (Agostino and Arnaboldi Citation2018; Aucoin and Heintzman Citation2000; Ferlie and Shortell Citation2001; Freeman Citation2002; Gardner, Olney, and Dickinson Citation2018; Lewis and Triantafillou Citation2012; Mundy Citation2010; Tessier and Otley Citation2012; Van Dooren Citation2011; Van Dooren, Bouckaert, and Halligan Citation2010). Scholars debate whether performance management can be used for both accountability and improvement purposes. Those who argue that these goals of performance management cannot co-exist contend that each requires distinct system architectures and strategies for data analysis and use, and that pursuing both is costly and transmits conflicting signals to managers (Ferlie and Shortell Citation2001; Freeman Citation2002; Gardner, Olney, and Dickinson Citation2018; Lewis and Triantafillou Citation2012; Van Dooren Citation2011). However, our case study reveals this is a false dichotomy.

We contend and demonstrate in this paper that the boundaries between formal and informal network governance mechanisms may be fuzzier and more complex than originally thought. The debate in the performance management literature also suggests that perceived goals of network governance, or of specific governance mechanisms, may be an important, overlooked aspect of how we understand network governance. Much has been written about the issue of goal congruence in networks, that is, the alignment (or lack thereof) among network-level and organizational-level goals (Vangen & Huxham Citation2012; Piatak et al. Citation2018). While important, our interest is not in network goals, but rather in the perceived goals of network governance mechanisms, such as performance management. In summary, studying the operationalization of network governance requires attention to governance structures, perceived goals, and behaviours.

Tensions in network governance: control and collaboration

In addition to the tension between formal and informal governance mechanisms, discussed in detail above, there are many other tensions inherent in the practice of network governance, including the tension between: (1) efficient operations and inclusive decision-making, (2) stability for consistent and efficient network responses and flexibility for rapid network responses, (3) external legitimacy to outsiders and internal legitimacy among members, (4) unity needed for coordination and diversity needed for innovation, and (5) accountability for network goals and autonomy of members (Berthod et al. Citation2017; Ospina and Saz-Carranza Citation2010; Provan and Kenis Citation2008; Saz-Carranza and Ospina Citation2011).

Although these tensions are apparent in our data, it was another tension – that between control and collaboration – that emerged empirically as a defining feature of the relationship between the NAO and the networks we studied. The tension between control and collaboration also seems to underlie the varied tensions identified in the literature. Network governance approaches that favour informal governance mechanisms, inclusivity, flexibility, internal legitimacy, diversity, member autonomy, and/or learning are more likely to emphasize collaboration (i.e. a more hands-off, supportive, relationship-oriented approach). On the other hand, network governance approaches that favour formal governance mechanisms, efficiency, stability, external legitimacy, unity, and/or accountability are more likely to emphasize control (i.e. a more hands-on, assertive, compliance-oriented approach). The control-collaboration tension is thus an inherent and fundamental issue in network governance; both ends of the pole are needed for effective network governance and performance (Agostino and Arnaboldi Citation2018; Moynihan Citation2009; Sundaramurthy and Lewis Citation2003; Wang et al. Citation2019).

Managing tensions in network governance through ambidexterity

Managing and balancing tensions in network governance is critical for network functioning and performance (Berthod and Segato Citation2019; Lee Citation2022; Provan and Kenis Citation2008; Sundaramurthy and Lewis Citation2003; Wang and Ran Citation2021). Tensions can be managed through network governance approaches that combine ‘hands-on’ and ‘hands-off’ governance tools or involve switching between ‘assertive’/‘controlling’ and ‘supportive’/‘coaching’ modes of governance (Berthod et al. Citation2017; Chen Citation2021; Kreutzer and Jacobs Citation2011; Saz-Carranza and Ospina Citation2011; Sørensen and Torfing Citation2009; Waardenburg et al. Citation2020). This ability to combine or switch between formal assertive governance mechanisms and informal supportive governance mechanisms has been described in the literature using various labels, including ‘hybrid governance’ (Berthod et al. Citation2017), ‘behavioural agility’ (Kreutzer and Jacobs Citation2011), and ‘structural ambidexterity’ (Bryson et al., Citation2008; Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2015). We use the term ‘ambidexterity’ because it refers explicitly to the ability to hold opposing poles equally well and is based on a rich literature on organizational ambidexterity in strategic management (O’Reilly and Tushman Citation2013).

Empirical studies of ambidexterity in the context of network governance are limited, but generally find that ambidexterity effectively addresses various tensions thereby improving network or partnership functioning (Berthod et al. Citation2017; Chen Citation2021; Saz-Carranza and Ospina Citation2011; Waardenburg et al. Citation2020). Studies have also identified a few key antecedents and enablers of network governance ambidexterity. The most identified antecedents are regular discussions among network members in the context of stable, trusting relationships (Agostino and Arnaboldi Citation2018; Berthod et al. Citation2017; Chen Citation2021; Kreutzer and Jacobs Citation2011; Moynihan Citation2009). Strong relationships appear to provide a common foundation and foster mutual understanding amidst shifts in network governance approach. Studies also suggest that network governance ambidexterity is heightened during times of crisis due to the abrupt need for more centralized and assertive governance (Berthod et al. Citation2017; Moynihan Citation2009) and that it is facilitated by the involvement of a process manager or coach who can guide network members in managing the tensions inherent in their work (Waardenburg et al. Citation2020). Overall, these studies demonstrate that ambidexterity is dependent on a combination of contextual factors, structures, and processes with relationships (i.e. behavioural dynamics) at the core.

Despite some attention to ambidexterity in studies of network governance, as noted above, definitions and descriptions of the phenomenon of ‘network governance ambidexterity’ remain generic and under-theorized. Our case study responds to the call from network governance scholars for research on what kinds of ambidexterity are needed and how ambidexterity is developed and managed in the governance of networks and partnerships (Berthod and Segato Citation2019, Bryson et al., Citation2008; Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2015; Waardenburg et al. Citation2020).

Methodology

Study setting

We identified an exemplar NAO in Ontario, Canada that funds and oversees 40 inter-organizational service delivery networks using a robust performance management system. Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) is a government agency that manages the Ontario Renal Network and is responsible for monitoring and improving cancer and renal care on behalf of the Government of Ontario. CCO is thus a NAO that provides external governance by mandate and through centralized mechanisms (Provan and Kenis Citation2008). The 40 service delivery networks and their NAO can be classified as a purpose-oriented ‘network of networks’, united by a shared goal to plan, deliver, and improve cancer and renal care. According to previous research, international health data comparisons, and media reports, CCO and its performance management system are high-performing and internationally renowned (Bell Citation2019; CIHI Citation2019; Frketich and LaFleche Citation2019; Hagens et al. Citation2020).

CCO was first established in 1943 as the Ontario Cancer Treatment and Research Foundation. In 1997, it was re-named CCO and given a broader mandate. In 2004, CCO’s mandate was modified again, and the cancer networks were established through a voluntary re-structuring process (Sullivan et al. Citation2004; Thompson and Martin Citation2004). The renal networks pre-existed the development of the ORN in 2009 under the auspices of CCO (Woodward et al. Citation2015). Each cancer and renal network that CCO oversees is made up of multiple non-profit, publicly funded hospitals and other types of non-profit and for-profit publicly funded health services providers within specific geographical boundaries. Fourteen of the networks deliver cancer services and 26 deliver renal services. Cancer networks are led by Regional Vice Presidents while renal networks are led by Regional Directors. Regional Vice Presidents and Regional Directors have dual accountability to CCO and the hospital at which they are based. CCO also recruits practicing clinicians from the networks to serve as Clinical Leads. Clinical leads are typically paid by CCO for 1–2 days per week to participate in strategic planning, indicator selection and target-setting, guideline development, and implementation of clinical improvement initiatives (Duvalko, Sherar, and Sawka Citation2009).

The performance management system used to oversee these networks comprises multiple interventions implemented in a staggered approach first in cancer care since 2005 and then in renal care since 2013. The performance management interventions include funding contracts; a scorecard; web-based access to performance data; quarterly performance review reports and meetings; performance recognition certificates; an escalation process for poor or declining performance; and public reporting (Bytautas et al. Citation2014; Cheng and Thompson Citation2006; Duvalko, Sherar, and Sawka Citation2009; Sullivan et al. Citation2004). Additional details on CCO’s performance management system are provided in the appendix.

Study design

We conducted a qualitative case study, a methodology well-suited for deeply examining issues in their real-life context and answering ‘how’ questions (Yin Citation2018). Our unit of analysis was the whole network, inclusive of the NAO and 40 service delivery networks; as such, this research constitutes a single, embedded case study. We applied a qualitative constructivist approach. A constructivist perspective assumes that multiple realities exist and examines how stakeholders construct reality and what the consequences of their constructions are for their behaviours and interactions (Patton Citation2002).

At the time of data collection, the first author of this paper was an embedded researcher at CCO; her role was to carry out research and evaluation through a collaborative process by working inside CCO as a staff member while affiliated with an external academic institution (Vindrola-Padros et al. Citation2017). She was thus both an insider and an outsider, a situation common to those who conduct ethnographic research (Lewis and Russell Citation2011). Reflexivity was facilitated using several strategies (Davies Citation1999). First, a research team was established consisting of academic experts; the first author was the only member embedded at CCO. Second, an advisory committee was established of CCO representatives, network representatives, and the research team. The committee provided feedback on the study, facilitated access to participants for data collection, and supported dissemination of results. Third, ethical processes were followed, including ensuring raw data was only available to the first author, obtaining informed consent, and guaranteeing participants confidentiality. Formal ethics review was waived because the lead researcher was embedded at CCO and the study complied with privacy regulations. CCO is designated a ‘prescribed entity’ as per Section 45(1) of the Personal Health Information Protection Act of 2004. CCO is thus authorized to collect and use data to manage, evaluate, or monitor the health system. Finally, member checking was conducted through presentations and written summaries (Davies Citation1999).

Data collection

We aimed to capture perspectives of the NAO and member networks, both of which included administrative and clinical staff from multiple hierarchical levels. To participate, individuals had to be employed by CCO or a member network and involved in or influenced by CCO’s performance management system. A list of eligible CCO administrative and clinical representatives was generated by the Performance Management Units of the cancer and renal branches of the organization. For recruitment of individuals within networks, an invitation was e-mailed to the Regional Vice Presidents (cancer) and Regional Directors (renal). Networks that agreed to participate provided a list of eligible administrative and clinical leaders. This purposeful sampling approach was augmented by snowball sampling.

During a six-month period between 2017 and 2018, the first author conducted 40-minute semi-structured individual and group interviews with 59 CCO representatives and 88 representatives from 12/14 (86%) cancer networks and 19/26 (73%) renal networks for a total sample size of 147 individuals. The sample included both high- and low-performing networks based on scorecard rankings. summarizes participant demographics. Interviews with CCO representatives were primarily conducted in person, while those with network representatives were primarily by phone due to geographic dispersion. Both CCO and network representatives were asked the same set of questions, namely, to assess (1) CCO’s role in managing performance, (2) the relationship between CCO and the networks, and (3) the interventions that constitute CCO’s performance management system (see Appendix for interview guide). We probed on identified strengths and weaknesses and encouraged participants to share anecdotes. Participants were then shown a list of CCO’s performance management interventions as a cognitive aid and asked to identify additional strengths and weaknesses. The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

The interviews were supplemented by document analysis and non-participant observation. Documents were identified for analysis through discussion with Performance Management Unit staff at CCO and included documents that constituted or described the performance management system, such as policies, meeting minutes, and data files. The first author also conducted non-participant observation of 15 one-hour quarterly performance review meetings over a one-year period. During these meetings, the first author took notes in three categories: observational notes (what was seen or heard), personal notes (what the observer felt), and theoretical notes (interpretive attempts to attach meaning to observations and feelings) (Baker Citation2006). Most notes were regarding (1) how CCO and network representatives discussed and/or responded to poor versus strong performance, and contextual challenges influencing performance, and (2) the nature of the relationship between CCO and each network based on tone, word choice, and content of conversations.

Data analysis

An inductive approach to coding was applied using NVivo software (Patton Citation2002). First, two coders independently open coded three transcripts and met to compare, reconcile, and finalize a preliminary coding framework. One member of the team then coded the remaining transcripts, adding new inductive codes as needed in discussion with the second coder. Documents and observation notes were also coded in NVivo to contextualize, supplement, and triangulate the interview data. This initial round of coding resulted in inductive codes organized into the following broad categories: perceptions of the NAO, NAO-network relationship, goals of performance management, practice of performance management (by CCO), experience of performance management (by the networks), determinants of performance management, and consequences of performance management.

Following a thematic analysis methodology (Braun and Clarke Citation2012), we identified two recurrent patterns across the codes. First, we found that participants from CCO and from both high- and low-performing networks expressed strong positive assessments of the performance management system. Participants agreed that CCO uses a robust performance management system that has had a positive impact on performance in cancer and renal care due to province-wide priority-setting, data collection, reporting, benchmarking, and sharing of best practices across networks. Participants also recognized opportunities for improvement, highlighting the significant opportunity cost associated with (a) data collection and reporting and (b) the number and scale of required initiatives. Second, we found a complex and synergistic dynamic between control and collaboration. Taken together, these two themes suggested that this ‘network of networks’ was effectively managing the tension between control and collaboration. Given extensive discussion and debate on such tensions in the literature on network governance, we wanted to better understand how this NAO was able to do so. We thus revisited our data and inductive codes with a more focused research question: how do the NAO and networks effectively manage the tension between control and collaboration in their relationship? We aggregated relevant inductive codes into representative empirical themes and finally abstracted those themes to produce higher-level conceptual dimensions (See Appendix for data structure demonstrating progression from inductive codes to conceptual dimensions) (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013).

Despite differences in the age/maturity of the performance management system in cancer versus renal care and despite representation from both high- and low-performing networks, themes were overlapping. We therefore do not distinguish between cancer and renal networks or between high- and low-performing networks in the results.

Results

We found that the governance relationship between CCO and the networks it governs operates as a ‘dance’ with CCO taking steps to collaborate with and control the networks over time and across performance management interventions. The networks also have agency and take steps that reinforce collaboration or control in the dance with CCO. It is through this dance that network governance and performance management function to achieve the network’s mission. We identified three forms of network governance ambidexterity that characterize this dance: (1) structural ambidexterity, (2) goal ambidexterity, and (3) behavioural ambidexterity. We describe below each of these forms of ambidexterity and how they manifested in the data. Then we identify factors that seemed to influence the relative emphasis on control and/or collaboration; that is, whether the control-collaboration tension was managed simultaneously (control ‘and’ collaboration) or in an oscillating pattern (control ‘or’ collaboration).

Structural ambidexterity

Elements of both control and collaboration were identified in the codified contracts, standards, and processes of performance management, suggesting that ‘structural ambidexterity’ is built into the system. Performance requirements and deliverables as well as sanctions are codified. For example, CCO’s contracts with the networks state, ‘The Recipient shall perform the Performance Requirements … and adhere to the Program Expectations specified below’. In both the contracts and the escalation policy for poor or declining performance, there is reference to what is ‘required’ of networks not meeting performance requirements and of the criteria for withdrawing funds. Similar language was used by both CCO and network representatives. For example, CCO representatives discussed ‘setting expectations and standards through funding contracts’ (P003 CCO). Network representatives explained, ‘our contractual agreements clearly define what the requirements are so there is a legal commitment there’ (P055 Network) and ‘if you don’t perform, you end up sometimes losing resources as per our funding letters’ (P048 Network). This last sentiment regarding potentially losing resources for poor performance was common among network representatives. However, CCO only retracts funds for failing to meet a deliverable – such as patient volumes, regular data submission, and implementation of initiatives – not for failing to meet a performance target (except for one former indicator). Nevertheless, there was a pervasive perception among network representatives that funds were on the line based on their performance on all scorecard indicators.

Despite this heavy emphasis on control in performance management documents, there were also codified expectations for collaboration. For example, in CCO’s Quarterly Performance Review Report template, the aims of the report are described as fostering ‘joint discussion, problem solving, and quality improvement within and between hospitals’. In CCO’s escalation policy for poor or declining performance, CCO’s role involves ‘developing performance requirements and indicators in collaboration with [network] stakeholders’ and ‘work[ing] with [networks] to understand and address performance issues’. The escalation policy also emphasizes the importance of engaging networks, often referred to as ‘partners’, and of providing support or assistance in addressing performance issues.

Finally, interdependence between CCO and the networks is also codified in a way that supports both control and collaboration. CCO is mandated by law to oversee and manage the cancer and renal systems, while the networks are mandated and funded to deliver cancer and renal services to patients. CCO cannot fulfil its mandate without performance data from the networks and their cooperation on provincial initiatives. The networks cannot paint a complete picture of their performance and improve their services without the benchmarking data CCO feeds back to them. As one CCO representative declared, ‘I don’t see us managing the regions. The regions are our critical partners. We would not be able to execute our provincial strategies without our regional partners because CCO is not a service deliverer, the regions are’ (P025 CCO).

Network leaders also have dual accountability to both CCO and to their host hospital enshrined in their employment contracts. Similarly, clinical leads are paid by CCO for one day per week of their time. In both cases, network employees in key leadership positions have employment contracts that refer to or are from CCO, creating a strong codified interdependence between the networks and CCO that facilitates both control and collaboration. As one participant pointed out, ‘The fact that CCO pays salary for directors and physicians to participate has subtly, but very definitely, resulted in buy-in’ (P053 Network).

Goal ambidexterity

When the goals of performance management are both controlling and collaborative, we refer to this as goal ambidexterity. Most participants from CCO and the networks identified both accountability and improvement as goals associated with CCO’s role as a NAO and its performance management system. Descriptions of CCO’s role often began with standard-setting, funding, monitoring, and compliance, suggesting that accountability takes precedence. This is corroborated by consensus among network representatives that a strength of the performance management system is that it fosters a sense of accountability, as this participant described: ‘In the past, we functioned independently with not much oversight…We weren’t accountable to anybody. [Now we have] that accountability and clear expectations’ (P068 Network).

Yet, participants’ anecdotes and word choice revealed that they viewed improvement as the ultimate aim. Participants described CCO ‘enabling’ (P024 CCO) and ‘shepherding’ (P073 Network) improvement. Many argued, ‘We’re seeing changes in practice occur and that’s their [CCO’s] job’ (P062 Network). Another participant argued that improvement, not accountability, provides the ‘bigger picture view on what the ultimate goal of measuring those things [is] (P060 Network).

Participants suggested that accountability is a goal in service of the ultimate goal of improvement. This does not mean, however, that accountability is a proximal or intermediate goal in a causal pathway to improvement; this linear approach to thinking about the two concepts is misleading. For example, with regard to development of performance indicators, we heard that it may take time for an indicator to be ‘ready’ for use as an accountability tool. As one participant noted, ‘Those indicators should have been developmental and facilitated regions to learn. They were nowhere close to being ready for accountability’ (P056 Network). This example reinforces the need for a temporal perspective on the goals of performance management. Our data suggest that not only is accountability often in service of improvement (i.e. simultaneous requirements), particularly in the healthcare industry, but there may in fact be movement back and forth between the goals of accountability and improvement (i.e. sequential or oscillating requirements) depending on the nature of the indicator and its stage of development (as the above example suggests), as well as other factors such as provincial performance trends and what constitutes ‘good performance’. For example, if most networks are near, at, or have exceeded the target there may be a shift from accountability to continuous improvement or maintenance as the goal.

In summary, stakeholder perceptions of the role of CCO and the goals of performance management point to an ambidextrous practice in which CCO both establishes accountability and enables improvement, thus leveraging both control and collaboration either simultaneously or sequentially.

Behavioural ambidexterity

The most complex and intriguing form of ambidexterity we identified was behavioural ambidexterity, that is, how the (inter-)actions of CCO and the networks exemplified both control and collaboration. CCO’s performance management system relies on interventions that appear control-oriented based on how they are described in CCO documents and by CCO and network representatives. For example, CCO representatives discussed the activities they undertake including ‘requiring work plans’ (P009 CCO), ‘rolling out tools and initiatives’ (P025 CCO), ‘ensuring accountabilities are met through measurement and monitoring at regular intervals’ (P014 CCO), and ‘asking why aren’t you meeting this target and what are you doing about it?’ (P002 CCO). Network representatives agreed, ‘we know that we’re going to have to account for where we’re doing well and where we’re not’ (P073 Network). When sharing various anecdotes, network representatives also reported feeling ‘defensive’ (P068 Network) ‘embarrassed’ (P048 Network), ‘threatened’ (P067 Network) and ‘tired’ (P070 Network) at times, sentiments that suggest a sense of being controlled.

Yet, despite a perceived focus on control, participants also emphasized the collegial non-punitive behaviours and tone of how the performance management system is executed. In the interviews, CCO representatives described a ‘we’re in this together approach’ (P071 CCO) in which they ‘try to make it a discussion and make it collaborative, rather than punitive … so [networks] feel that they can share their challenges with us’ (P007 CCO). Another CCO representative elaborated, ‘It’s an atmosphere of how can we help you succeed?… How can we connect you with another program that’s similar in size and demographics that’s doing really well and that you can learn from?’ (P024 CCO). Use of the term ‘partnership’ was common among CCO representatives as well as the recognition that while the agency is ‘dictating’ to some extent, there are ‘strong feedback mechanisms and opportunities for the regions to make CCO aware of the realities close to the ground’ (P001 CCO). A CCO representative provided an example of these feedback mechanisms in action:

We’re taking two patient experience indicators off the scorecard at the request of the RVPs [Regional Vice Presidents], because they’ve become a source of negativity. Their teams work really hard to improve, local measurement suggests its going well, then they get these reports, and they haven’t moved or they’ve gotten worse … We need more sensitive measures (P002 CCO)

Examples such as these demonstrate a skilled practice of behavioural ambidexterity in which CCO both exerts control using performance indicators and collaborates by listening and responding to network feedback.

Network representatives validated the views of CCO representatives, stating that ‘the conversations are not punitive’ (P60 Network), describing the ‘supportive responsiveness of CCO’ (P049 Network), and clarifying that they ‘never experienced a “thou shalt” command from CCO’ (P041 Network). They described performance management as ‘a little stressful, but very valuable’ (P063 Network) and ‘good pressure’ (P062 Network). One participant described a ‘spirit of wanting to understand what the challenges are and offer help centrally to address any of those issues’ (P60 Network). Another explained, ‘I see their role as supportive and including knowledge transfer, data and information sharing, establishing communities of practice, and providing expertise’ (P051 Network).

Our observation of quarterly performance review meetings corroborate the results above, namely that the behaviours and tone are largely non-punitive, supportive, and collaborative. We noted that CCO leaders typically started by thanking each network for their efforts before describing performance strengths and weaknesses (strengths were always mentioned first). CCO leaders congratulated networks where they improved or sustained performance, often mentioning individuals by name. They consistently asked for learnings where things were going well, and for challenges and improvement plans where things were not. They also often asked how they could help and invited network leaders to contact them following the meeting, as needed.

Behavioural ambidexterity in the relationship between CCO and the networks was also apparent when networks took it upon themselves to request both more collaborative and more controlling behaviours from CCO. For example, many network representatives expressed a desire for CCO to take on a more explicit role in local improvement. One representative explained, ‘CCO needs to instruct centres more on what they need to do in response to performance reports and escalation letters. I think the managers just don’t know enough about the data to know what the next steps are’ (P053 Network). Even CCO representatives concurred that providing additional support as it relates to improvement is appropriate and justified, as this individual pointed out, ‘Just giving some numbers and some trends … that puts all the onus on them to understand the methodology of measurement and what they need to do to be better. There probably is a more fulsome role for us to be more of the partner in helping to identify solutions’ (P071 CCO).

Networks also requested more controlling behaviours from CCO. This finding was unexpected. As noted above, most of the performance management interventions are deterrents or sanctions. CCO expects that networks will comply with contracts to avoid losing funding and will comply with performance requirements to avoid undergoing the escalation process or to avoid negative attention (e.g. in the media) or at meetings with their colleagues and peer networks. However, we found instances where regional leaders requested that CCO apply a penalty. For example, regional leaders have requested in private that CCO ‘be hard’ on them and their team during quarterly performance reviews meetings (P042 Network). The most common form of requesting a penalty was regarding formal escalation letters, which are issued in exceptional circumstances, for persistent poor or declining performance. In the past, leaders have requested that a formal letter be sent to them by CCO because they can use that letter to mobilize attention and resources at their institution, particularly with hospital administrators to whom they are also accountable, as described below.

We’ve sent an escalation letter … to resolve a specific issue at their demand, because then they have a letter from CCO saying this is a problem. And they go to their hospital CEO and to finance and say, we’re in trouble and how are we going to resolve this? So, the regional scorecard and all that is helpful to us at CCO in improving performance, but it’s also helpful for them. It’s a source of power (P029, CCO)

Without an agency like CCO, network representatives would have to mobilize attention and resources to performance challenges on their own. This could potentially stress the relationship between network leaders and hospital administrators. In the current governance structure, these networks can point the finger at CCO instead, thereby securing what they need to improve while maintaining positive relationships within their organization.

In another example, a network that received a formal escalation letter seemed to desire more follow-up and support, and even perhaps additional consequences for their inability to improve their performance:

We received an escalation letter requesting an action plan…We submitted our action plan. There haven’t been any further formal steps that have happened from that. We’re still challenged with that indicator and we have been asked about how we’re still not performing. But what’s next in terms of the escalation policy? (P049 Network)

These results are corroborated by our observation of quarterly performance review meetings, where prior to meeting start we heard a network leader ask CCO to be ‘more assertive’ and, in another meeting, a network leader referred to their request for a formal escalation letter. Through observation, we also became aware of a CCO committee tasked with improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the quarterly performance review reports. Given the opportunity to reduce demands associated with the reports, network representatives sitting on the committee chose to retain the current volume of indicators citing how helpful the information is to them and that there are no other sources for this information. Overall, controlling behaviours by CCO not only supported network-level goal achievement (i.e. improved performance on a CCO-monitored indicator), but also organizational goals related to the distribution of attention, information, and resources.

In the interviews we also heard examples of how behavioural ambidexterity acted like a reinforcing feedback loop with controlling behaviours strengthening the partnership between CCO and the networks and facilitating more collaborative behaviours, as this CCO representative shared:

They’ve been struggling on this indicator, and every quarter we have the same conversation: your performance is bad, what are you doing? They would provide every reason under the sun … and we would never get any traction about what they could do to make it better. When we formally escalated, they got some dedicated resources to do a root cause analysis … they identified a key contributing factor and now have improvement activities around that … the act of going through a formal escalation got them more organised and focused, and I think it also, in a way, created a better partnership between us and them … Now it’s much more of a two-way dialogue (P071, CCO)

These results emphasize the importance of distinguishing between how performance management interventions are codified (formal governance mechanisms) and how they are executed in practice (informal governance mechanisms). As one participant pointed out, ‘It’s not just about what the accountabilities are on the part of the [networks]. It’s about how we use them, how we apply them in context’ (P001 CCO). In this case, CCO exercises control with a collaborative tone to incite network agency and action, but the networks also call on CCO to engage in this practice judiciously. CCO representatives seemed to grapple with managing this tension, as this participant explained:

It’s a fine balance between wanting to jump in and take action [controlling behavior] versus work with [the networks] to help them identify the issues and work through them on their own [collaborative behavior]. A lot of it is relationship management. We want to have a strong relationship with our regional partners, but how much do we push?… We have to make judgements about when to do that or not do that (P008, CCO)

Discussion

Addressing the tension between control and collaboration is critical for network performance; yet, there is limited theory and empirical evidence regarding how such tensions are managed in practice in network governance relationships. Our study reveals how a NAO and the ‘network of networks’ it oversees managed the control-collaboration tension in their relationship through ambidexterity. depicts the components of a theoretical framework of network governance ambidexterity based on our data. We describe below these components.

Figure 1. A theoretical framework of network governance ambidexterity in the context of a NAO-governed, network-level performance management system involving both control and collaboration.

Network governance ambidexterity: types and stability

In our case study, network governance ambidexterity was achieved because elements of both control and collaboration were embedded in (a) codified structures and processes of performance management, (b) perceived goals of performance management, and (c) NAO-network interactions regarding performance management, thus enabling structural, goal, and behavioural ambidexterity, respectively. Our data suggest that structural ambidexterity is the most stable type of ambidexterity and provided the necessary scaffolding for flexible network governance. Goal and behavioural ambidexterity are less stable, and thus capable of simultaneously emphasizing control and collaboration or oscillating between the two as the situation demands.

Our framework of network governance ambidexterity builds on the literature on organizational ambidexterity, which examines how organizations manage tensions in strategic management. There are three approaches to organizational ambidexterity: sequential (oscillating between the two poles by changing formal structures and processes over time), simultaneous or structural (pursuing both poles by having separate subunits with different structures and processes focus on each pole), and contextual (allowing individuals to choose how to divide their time among the two poles) (O’Reilly and Tushman Citation2013). Sequential and simultaneous ambidexterity solve tensions through structures, while contextual ambidexterity solves them through behaviours. Our framework has a similar division between the structural (formal) and behavioural (informal), however there are three key differences. First, we use the term ‘structural ambidexterity’ more broadly. The poles of a tension do not necessarily need to be separated into discrete subunits; rather, they can be intertwined in formal, codified structures and processes. Second, we add a novel construct, ‘goal ambidexterity’. Prior research on organizational ambidexterity suggests that an overarching vision is required to legitimate the need for both poles of a tension (O’Reilly and Tushman Citation2013), yet vision or goals have not been identified as a means through which ambidexterity can be expressed alongside structures and behaviours. Third, ‘behavioural ambidexterity’ is a multi-level construct, encompassing not only individual behaviours, but also collective NAO-network behaviours and interactions. The relational component at the centre of behavioural ambidexterity in network governance is largely overlooked in previous conceptualizations of similar constructs like ‘contextual ambidexterity’ (O’Reilly and Tushman Citation2013) and ‘behavioural agility’ (Kreutzer and Jacobs Citation2011). Considering the important role of relationships in supporting network governance ambidexterity (Agostino and Arnaboldi Citation2018; Berthod et al. Citation2017; Chen Citation2021; Kreutzer and Jacobs Citation2011; Moynihan Citation2009), explicitly defining behavioural ambidexterity in terms of the interactions and relationship between the governor and governed is necessary.

Our results support literature suggesting that informal governance mechanisms are stronger determinants of network functioning and reduce the need for formal governance mechanisms (Marques et al., Citation2011; Piatek et al., Citation2018; Romzek et al. Citation2014). Many examples of behavioural ambidexterity in our data explicitly countered formal, codified aspects of performance management, such as when CCO removed two indicators from their scorecard based on network feedback or when networks requested controlling behaviours from CCO. While such phenomena may be viewed as contradictions between the formal and informal that generate confusion and conflict (Romzek et al. Citation2014), we suggest that what have traditionally been perceived as incongruences are synergistic and ultimately productive, strengthening NAO-network relationships and reinforcing performance management as a mutually beneficial system.

Factors that influence the relative emphasis on control VS collaboration

We identified three inter-related factors that seemed to explain the relative emphasis of goal and behavioural ambidexterity on control versus collaboration. First, the nature of the performance indicator, including the indicator’s stage of development and performance trends, can determine whether control is warranted (e.g. indicator is well-developed with strong data quality and/or performance is highly variable across networks), or collaboration is warranted (e.g. indicator requires further development and testing). Second, feedback and dialogue between CCO and the networks can dictate whether a controlling, accountability-driven or a collaborative, improvement-driven approach to performance management is warranted. For example, networks often requested more controlling or more collaborative behaviours and CCO complied. Finally, alignment of goals between CCO and the networks also influenced the relative emphasis on control versus collaboration. For example, when CCO’s provincial performance goals aligned with a network’s performance goals or their internal operational goals, networks were more likely to request control or collaboration.

These three influencing factors represent a nuanced, situation-based view of how the tension between control and collaboration can be managed. This is in stark contrast to the literature on performance management in healthcare, which argues that performance management systems should either be accountability-driven (controlling) or improvement-driven (collaborative), but not both (Ferlie and Shortell Citation2001; Freeman Citation2002; Gardner, Olney, and Dickinson Citation2018; Lewis and Triantafillou Citation2012; Van Dooren Citation2011).

Antecedents of network governance ambidexterity

The network governance ambidexterity apparent in our case study may only be possible within the context of a particular type of network governance relationship characterized by a unifying social cause, strong NAO competencies, member organization autonomy, and a mature governance relationship. Scholars have identified a range of factors that influence the nature and hybridity of governance relationships, including psychological factors such as motivation, trust, and organizational (or network) identification, and contextual factors such as hierarchy, power distance, and environmental stability (Agostino and Arnaboldi Citation2018; Berthod et al. Citation2017; Chen Citation2021; Davis, Schoorman, and Donaldson Citation1997; Hernandez Citation2012; Kreutzer and Jacobs Citation2011; Moynihan Citation2009). Our results verify the importance of these factors and suggest that with NAOs overseeing a mature purpose-oriented network of service delivery networks, additional factors may be at play. We describe five psychological and contextual factors that may help explain the network governance ambidexterity we identified. First, meeting the needs of patients with cancer and chronic kidney disease is a unifying ‘cause’ that both CCO and network representatives can agree is the reason for their existence. The internalization of this raison d’être facilitates a collaborative relationship even amidst a flurry of control-oriented performance management interventions. Second, at the time of data collection, CCO was a large organization with high administrative capacity in terms of human and financial resources. Administrative capacity influences network performance (Alonso and Andrews Citation2018; Bitterman and Koliba Citation2020) and network governance formality (Bauer, AbouAssi, and Johnston Citation2022); according to our results, it may also support network governance ambidexterity. Third, CCO has considerable credibility, both within the broader health system as evidenced by the media reports referenced earlier (Bell Citation2019; Frketich and LaFleche Citation2019) and among the networks. In the interviews, participants referred to the expertise and capabilities of CCO, which demonstrates strong network-level competencies (Provan and Kenis Citation2008). Fourth, participants referred to CCO’s efforts to involve network leaders and clinical leads in decision-making, allow discretionary space for networks to design local solutions, and identify and address systemic barriers affecting performance. These efforts promoted network autonomy, enhanced the credibility of CCO’s performance management approach, and improved alignment of interests between CCO and the networks. Finally, at the time of this study CCO’s performance management system had been in operation for 12 years in cancer care and 4 years in renal care, ample time to develop sophisticated infrastructure and mature, trusting relationships capable of perpetuating and coping with both control and collaboration (Wang and Ran Citation2021).

Outcomes of network governance ambidexterity

We propose that network governance ambidexterity improves a network’s ability to jointly act, achieve network goals, and adapt to change. By enabling a network to emphasize both control and collaboration, ambidexterity leverages the strengths of each pole while offsetting its weaknesses, generating the conditions necessary for network members to work together in pursuit of network goals (Lee Citation2022; Saz-Carranza and Ospina Citation2011). Without a governance approach that embraces both control and collaboration, network members may not experience the felt accountability and social bonds necessary for joint action and goal achievement. Network governance ambidexterity may also support network adaptation, whether to changing needs and expectations within the network or to external stimuli (Berthod et al. Citation2017). Specifically, behavioural ambidexterity allows the network to pivot and adjust quickly to new demands.

Limitations and future research

This study has limitations. First, we only interviewed physicians in a clinical lead role and we did not interview other healthcare professionals, such as nurses. These individuals, who are more removed from CCO’s influence, may have had differing experiences and views of performance management. Future research on network governance in healthcare should include physicians in non-leadership roles as well as other front-line providers. Second, many of our network interviews took place in groups, rather than one-on-one. The group setting may have deterred some participants from sharing their views and experiences. That said, we explicitly asked participants for weaknesses and risks associated with the performance management system, and we invited them to contact us directly via email or phone if they wanted to share additional points following the interview (no one did). Third, our results are based on a single qualitative case study of a NAO and the 40 healthcare delivery networks it oversees in one jurisdiction using a performance management system. It is necessary to determine if the ambidexterity we identified in our case applies in other jurisdictions and to other network governance forms that do not involve a NAO and/or a performance management system. Future studies should also adopt multiple case study designs and/or quantitative methods to build on and test the proposed theoretical framework with a broader sample of networks in and outside of healthcare.

Implications for research and practice

Our tripartite taxonomy of network governance ambidexterity may inform efforts to classify and compare network governance forms and relationships. To date, network governance has primarily been described based on formal structure, either shared governance, having a lead organization, or having a NAO, or some combination of these. Network governance may be further described and classified based on ambidexterity thereby providing richer and more nuanced descriptions that account not only for what is codified on paper (formal governance mechanisms), but also for how network governance is executed and experienced in practice (informal governance mechanisms). Application of the constructs of structural, goal, and behavioural ambidexterity and the development of associated measures can thus aid in comparing and synthesizing results across studies (Carboni et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, the theoretical framework () and associated results answer calls for research on how ambidexterity is developed and managed in networks and partnerships (Berthod and Segato Citation2019, Bryson et al., Citation2008; Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2015). The theoretical framework can inform future studies of network governance ambidexterity and performance management, as well as potentially explain network functioning and performance.

Our results also have practical implications. Policymakers and managers can draw from our findings to effectively foster both control and collaboration in network governance by infusing elements of both into their structures, perceived goals, and behaviours. Often, those designing network governance configurations focus on formal systems; our results suggest that they must also explicitly plan and design for ambidexterity. However, careful consideration for context is required. In our study, CCO’s mandate, structure, and history likely contributed to their ambidexterity whereas in other contexts a dynamic interplay between control and collaboration, such as by executing controlling behaviours with a collaborative tone, may be construed as paying lip service or sending mixed signals. Policymakers and managers may aim to mimic CCO’s contextual conditions by emphasizing a unifying social cause, developing NAO expertise and capabilities, supporting member autonomy and local solutions, ensuring that levels of trust are high, and allowing the governance relationship to mature. Combining controlling and collaborative approaches under these conditions and through structural, goal, and behavioural ambidexterity may enhance network governance and performance.

Human Subjects Research

Cancer Care Ontario is designated a ‘prescribed entity’ for the purposes of Section 45(1) of the Personal Health Information Protection Act of 2004. As a prescribed entity, Cancer Care Ontario is authorized to collect and use data with respect to the management, evaluation or monitoring of all or part of the health system, including the delivery of services. Because this study complied with privacy regulations, ethics review was waived. All participants provided verbal informed consent prior to participation in the research.

Acknowledgments

At the time of data collection for this study, JME was a Staff Scientist with Cancer Care Ontario (CCO). During data analysis and writing, JME had transitioned to a new job and no longer had an affiliation with CCO. In 2019, after the completion of data collection, CCO was merged into a new agency, Ontario Health. CCO's programs and services, including their performance management system, remain unchanged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agostino, D., and M. Arnaboldi. 2018. “Performance Measurement Systems in Public Service Networks: The What, Who, and How of Control.” Financial Accounting & Management 34 (2): 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12147.

- Alonso, J. M., and R. Andrews. 2018. “Governance by Targets and the Performance of Cross-Sector Partnerships: Do Partner Diversity and Partnership Capabilities Matter?” Strategic Management Journal 40 (4): 556–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2959.

- Aucoin, P., and R. Heintzman. 2000. “The Dialectics of Accountability for Performance in Public Management Reform.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 66 (1): 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852300661005.

- Babiak, K., and L. Thibault. 2009. “Challenges in Multiple Cross-Sector Partnerships.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 38 (1): 117–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764008316054.

- Baker, L. 2006. “Observation: A Complex Research Method.” Library Trends 55 (1): 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2006.0045.

- Bauer, Z., K. AbouAssi, and J. Johnston. 2022. “Cross-Sector Collaboration Formality: The Effects of Institutions and Organizational Leaders.” Public Management Review 24 (2): 159–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1798709.

- Bell, B. 2019. “Don’t Harm Cancer Care Ontario While Restructuring Health Agencies”. The Toronto Star. Accessed December 30, 2019, https://www.thestar.com/opinion/contributors/2019/01/17/dont-harm-cancer-care-ontario-while-restructuring-health-agencies.html.

- Berthod, O., M. Grothe-Hammer, G. Muller-Seitz, J. Raab, and J. Sydow. 2017. “From High-Reliability Organizations to High-Reliability Networks: The Dynamics of Network Governance in the Face of Emergency.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 27 (2): 352–371. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muw050.

- Berthod, O., and F. Segato. 2019. “Developing Purpose-Oriented Networks: A Process View.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 2 (3): 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvz008.

- Bitterman, P., and C. J. Koliba. 2020. “Modeling Alternative Collaborative Governance Network Designs: An Agent-Based Model of Water Governance in the Lake Champlain Basin, Vermont.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 30 (4): 636–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muaa013.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2012. “Thematic Analysis.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Research Designs, edited by H. Cooper, P.M. Camic, D.L. Long, A.T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K.J. Sher, 57–71. Vol. 2. Washington: American Psychological Association.

- Bryson, J. M., B. C. Crosby, and M. M. Stone. 2015. “Designing and Implementing Cross-Sector Collaborations: Needed and Challenging.” Public Administration Review 75 (5): 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12432.

- Bryson, J. M., B. C. Crosby, M. M. Stone, and J. C. Mortensen 2008. “Collaboration in Fighting Traffic Congestion: A Study of Minnesota’surban Partnership Agreement”. Report no. CTS 08-25, Center for Transportation Studies, University of Minnesota. accessed June 5, 2023. https://cts-d8resmod-prd.oit.umn.edu/pdf/cts-08-25.pdf.

- Bytautas, J., M. Dobrow, T. Sullivan, and A. Brown. 2014. “Accountability in the Ontario Cancer Services System: A Qualitative Study of System leaders’ Perspectives.” Healthcare Policy | Politiques de Santé 10 (Sp): 45–55. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpol.2014.23919.

- Carboni, J. L., A. Saz-Carranza, J. Raab, and K. R. Isett. 2019. “Taking Dimensions of Purpose-Oriented Networks Seriously.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 2 (3): 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvz011.

- Chen, J. 2021. “Governing Collaborations: The Case of a Pioneering Settlement Services Partnership in Australia.” Public Management Review 23 (9): 1295–1316. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1743345.

- Cheng, S. M., and L. J. Thompson. 2006. “Cancer Care Ontario and Integrated Cancer Programs: Portrait of a Performance Management System and Lessons Learned.” Journal of Health Organization & Management 20 (4): 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777260610680131.

- CIHI (Canadian Institute for Health Information). 2019. “OECD Interactive Tool: International Comparisons – Quality of Care”. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.cihi.ca/en/oecd-interactive-tool-international-comparisons-quality-of-care.

- Davies, C. A. 1999. Reflexive Ethnography: A Guide to Researching Selves and Others. London: Routledge.

- Davis, J. H., F. D. Schoorman, and L. Donaldson. 1997. “Toward a Stewardship Theory of Management.” The Academy of Management Review 22 (1): 20–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/259223.

- Duvalko, K. M., M. Sherar, and C. Sawka. 2009. “Creating a System for Performance Improvement in Cancer Care: Cancer Care Ontario’s Clinical Governance Framework.” Cancer Control: Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center 16 (4): 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/107327480901600403.

- Ferlie, E. B., and S. M. Shortell. 2001. “Improving the Quality of Health Care in the UK and the US: A Framework for Change.” The Milbank Quarterly 79 (2): 281.

- Freeman, T. 2002. “Using Performance Indicators to Improve Health Care Quality in the Public Sector: A Review of the Literature.” Health Services Management Research 15 (2): 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1258/0951484021912897.

- Frketich, J., and G. LaFleche 2019. “Super Agency Brings End to Independent Cancer Care Ontario”. Hamilton Spectator. Accessed December 30, 2019, https://www.thespec.com/news-story/9510881-super-agency-brings-end-to-independent-cancer-care-ontario/.

- Gardner, K., S. Olney, and H. Dickinson. 2018. “Getting Smarter with Data: Understanding Tensions in the Use of Data in Assurance and Improvement-Oriented Performance Management Systems to Improve Their Implementation.” BMC Health Research Policy & Systems 16 (1): 125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0401-2.

- Gioia, D. A., K. G. Corley, and A. L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151.

- Goodwin, N., V. Stein, and V. Amelung. 2021. “What is Integrated Care?” In Handbook of Integrated Care, edited by V. Amelung, V. Stein, E. Suter, N. Goodwin, E. Nolte, and R Balicer, 3–25. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69262-9_1.

- Hagens, V., C. Tassone, J. M. Evans, D. Burns, V. Simanovski, and G. Matheson. 2020. “From Measurement to Improvement in Ontario’s Cancer System: Analyzing the Performance of 28 Provincial Indicators Over 15 Years.” Healthcare Quarterly 23 (1): 53–59. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcq.2020.26138.

- Hernandez, M. 2012. “Toward an Understanding of the Psychology of Stewardship.” Academy of Management Review 37 (2): 172–193. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0363.

- Kenis, P., and K. G. Provan. 2006. “The Control of Public Networks.” International Public Management Journal 9 (3): 227–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967490600899515.

- Koliba, C., E. Campbell, and A. Zia. 2011. “Performance Management Systems of Congestion Management Networks.” Public Performance & Management Review 34 (4): 520–548. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576340405.

- Koliba, C., A. Zia, and R. M. Mills. 2011. “Accountability in Governance Networks: An Assessment of Public, Private, and Nonprofit Emergency Management Practices Following Hurricane Katrina.” Public Administration Review 71 (2): 210–220.

- Kreutzer, K., and C. Jacobs. 2011. “Balancing Control and Coaching in CSO Governance: A Paradox Perspective on Board Behavior.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 22 (4): 613–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-011-9212-6.

- Lee, S. 2022. “When Tensions Become Opportunities: Managing Accountability Demands in Collaborative Governance.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 34 (4): 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muab051.

- Lewis, S. J., and A. J. Russell. 2011. “Being Embedded: A Way Forward for Ethnographic Research.” Ethnography 12 (3): 398–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138110393786.

- Lewis, J. M., and P. Triantafillou. 2012. “From Performance Measurement to Learning: A New Source of Government Overload?” International Review of Administrative Sciences 78 (4): 697–614.

- Liu, Y., and C. Tan. 2022. “The Effectiveness of Network Administrative Organizations in Governing Interjurisdictional Natural Resources.” Public Administration 101 (3): 932–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12834.

- Maron, A., and A. Benish. 2022. “Power and Conflict in Network Governance: Exclusive and Inclusive Forms of Network Administrative Organizations.” Public Management Review 24 (11): 1758–1778. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1930121.

- Marques, L., J. A. Ribeiro, and R. W. Scapens 2011. “The Use of Management Control Mechanisms by Public Organizations with a Network Coordination Role: A Case Study in the Port Industry.” Management Accounting Research 22 (4): 269–291.

- Moynihan, D. P. 2009. “The Network Governance of Crisis Response: Case Studies of Incident Command Systems.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 19 (4): 895–915. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mun033.

- Mundy, J. 2010. “Creating Dynamic Tensions Through a Balanced Use of Management Control Systems.” Accounting, Organizations & Society 35 (5): 499–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2009.10.005.

- Nowell, B. L., and P. Kenis. 2019. “Purpose-Oriented Networks: The Architecture of Complexity.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 2 (3): 169–173. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvz012.

- Nylen, U. 2007. “Interagency Collaboration in Human Services: Impact of Formalization and Intensity on Effectiveness.” Public Administration 85 (1): 143–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00638.x.

- O’Reilly, C. A., III, and M. L. Tushman. 2013. “Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, Present, and Future.” Academy of Management Perspectives 27 (4): 324–338. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2013.0025.

- Ospina, S. M., and A. Saz-Carranza. 2010. “Paradox and Collaboration in Network Management.” Administration & Society 42 (4): 404–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399710362723.

- O’Toole, J. L., Jr. 1997. “Treating Networks Seriously: Practical and Research-Based Agendas in Public Administration.” Public Administration Review 57 (1): 45–52.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Piatak, J., B. Romzek, K. LeRoux, and J. Johnston 2018. “Managing Goal Conflict in Public Service Delivery Networks: Does Accountability Move Upand Down, or Side to Side?.” Public Performance & Management Review 41 (1): 152–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2017.1400993.

- Popp, J. K., H. B. Milward, G. MacKean, A. Casebeer, and R. Lindstrom. 2014. Inter-Organizational Networks: A Review of the Literature to Inform Practice. Washington, D.C: IBM Center for The Business of Government.

- Provan, K. J., and P. Kenis. 2008. “Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 18 (2): 229–252.

- Romzek, B. S., K. LeRoux, and J. Blackmar 2012. “A Preliminary Theory of Informal Accountability Among Network Organizational Actors.” Public Administration Review 72 (3): 442–453.

- Romzek, B., K. LeRoux, J. Johnston, R. J. Kempf, and J. S. Piatak. 2014. “Informal Accountability in Multisector Service Delivery Collaboration.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 24 (4): 813–842. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mut027.

- Saz-Carranza, A., and S. M. Ospina. 2011. “The Behavioral Dimension of Governing Interorganizational Goal-Directed Networks – Managing the Unity-Diversity Tension.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 21 (2): 327–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq050.

- Smith, P. C. 2002. “Performance Management in British Health Care: Will It Deliver?” Health Affairs 21 (3): 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.103.

- Sørensen, E., and J. Torfing. 2009. “Making Governance Networks Effective and Democratic Through Metagovernance.” Public Administration 87 (2): 234–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01753.x.

- Sullivan, T., M. Dobrow, L. Thompson, and A. Hudson. 2004. “Reconstructing Cancer Services in Ontario.” Healthcare Papers 5 (1): 69–80. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpap.16843.

- Sundaramurthy, C., and M. Lewis. 2003. “Control and Collaboration: Paradoxes of Governance.” The Academy of Management Review 28 (3): 397–415. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040729.

- Tessier, S., and D. Otley. 2012. “A Conceptual Development of Simons’ Levers of Control Framework.” Management Accounting Research 23 (3): 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2012.04.003.

- Thompson, L., and M. Martin. 2004. “Integration of Cancer Services in Ontario: The Story of Getting It Done.” Healthcare Quarterly 7 (3): 42–48. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcq.16624.

- Van Dooren, W. 2011. “Better Performance Management: Some Single- and Double-Loop Strategies.” Public Performance and Management Review 34 (3): 420–433. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576340305.

- Van Dooren, W., G. Bouckaert, and J. Halligan. 2010. Performance Management in the Public Sector. London: Routledge.

- Vangen, S., J. P. Hayes, and C. Cornforth 2015. “Governing Cross-Sector, Inter-Organizational Collaborations.” Public Management Review 17 (9): 1237–1260.

- Vangen, S., and C. Huxham 2012. “The Tangled Web: Unraveling the Principle of Common Goals in Collaborations.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 22 (4): 731–760. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur065.

- Vindrola-Padros, C., T. Paper, M. Utley, and N. Fulop. 2017. “The Role of Embedded Research in Quality Improvement: A Narrative Review.” BMJ Quality & Safety 26 (1): 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004877.