ABSTRACT

This study investigates how public procurement is used strategically to create social value. Public management research has analysed the different levels, forms, and processes of social value creation, but little is known about the role of public procurement in this respect. Based on 17 cases of UK public-sector anchor institutions (Metropolitan Councils and hospitals), we unveil social value-oriented procurement strategies, inter-organizational structures, supplier management practices, and capability development and performance assessment activities. We contribute to public administration research by showing how social value policies translate into strategic procurement goals and activities.

Introduction

Public procurement accounts for a significant share of most nations’ economies. Evidence from OECD analysis (Citation2021) demonstrates the important weight of public procurement on the gross domestic product (GDP) in countries such as Germany (18%), the UK (16%), France (15%), and the U.S. (9%). The impact of public procurement has implications beyond the economic realm, as government spending effectively becomes a means to enact policies addressing contemporary grand challenges including climate change and social inequalities. An elaborate discussion of these public policy objectives is beyond the scope of this study. Yet, it is worth noting that in addition to value for money (Dimitri Citation2013), public procurement is linked to the achievement of multiple outcomes, notably innovation (Knutsson and Thomasson Citation2014; Selviaridis Citation2016, Citation2021), sustainability (Brammer and Walker Citation2011), economic development (Preuss Citation2009), engagement with small businesses (Choi and Park Citation2021; Selviaridis and Spring Citation2022), and social value (Wontner et al. Citation2020).

In this paper, we focus on the role of public procurement in creating social value. As recently pointed out (Hafsa, Darnall, and Bretschneider Citation2022), we still know little about the functionality of public procurement in this respect. Social value refers to the broader economic, social, and environmental wellbeing of the community where public administrations operate (Quélin, Kivleniece, and Lazzarini Citation2017). It extends beyond efficiency and value for money considerations (Patrucco, Luzzini, and Ronchi Citation2016) and includes sustainability and (local) economic development aspects (Snider, Reysen, and Katzarska-Miller Citation2013). Social value manifests through a diverse set of outcomes such as social inclusion (e.g. of disadvantaged minorities), employment and training, decent working conditions, small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) access to public contracting, environmental protection and ethical conduct in supply chains (Opoku and Guthrie Citation2018a; Troje and Andersson Citation2020).

Public management research has articulated how social value is created and distributed through the delivery of public services – it emphasizes the different forms and processes involved (Jain et al. Citation2020), as well as the different levels at which value creation manifests (Osborne et al. Citation2022). This stream of research also recognizes the role of public procurement in delivering social value (Jain et al. Citation2020) but stops short of studying in detail how, and under what conditions, procurement contributes to this end.

Public procurement research, on the other hand, has recently emphasized social value as a salient objective of strategic procurement (Vluggen et al. Citation2020). Public procurement practice is increasingly challenged to incorporate the demands of multiple stakeholders, ultimately reflecting governments’ mission to serve society (Malacina et al. Citation2022). The emphasis on social value reflects, at least partly, the development of related laws and regulations. In the UK context, for instance, The Public Services (Social Value) Act of 2013 requires public bodies to consider the creation of social and environmental value through their procurement process. The emerging literature on social value-oriented public procurement discusses how social value can be embedded at individual stages of the procurement process while noting significant implementation challenges (e.g. Amann et al. Citation2014; Grandia and Meehan Citation2017; Wontner et al. Citation2020). Yet, this literature lacks a unified analytical framework for studying more systematically the procurement strategies, processes and practices conducive to social value. We, therefore, ask: How does strategic public procurement promote social value creation?

We seek to answer this question by conducting empirical research in the context of UK public-sector anchor institutions (AIs). These are relatively large organizations that have roots in an identifiable geographical area. Their presence is expected to last, and their mission is to ensure the development and welfare of local communities (Taylor and Luter Citation2013). We focus on AIs for two main reasons: a) their mission is inherently linked to social welfare (Garton Citation2021), and (b) procurement is one of the main ways through which they seek to create social value (Ehlenz Citation2018; Newby and Denison Citation2018). Furthermore, AIs focus on local needs and priorities, offering a suitable context for studying the elevated role of place-based procurement strategies in achieving social value outcomes (Uyarra, Ribeiro, and Dale-Clough Citation2019).

We empirically investigate 17 cases of UK Metropolitan Councils and National Health Service (NHS) Trusts (hospitals), as two dominant types of AIs in the UK public sector context. The UK is an appropriate setting due to the Public Services (Social Value) Act (UK Government, Citation2012), which was enacted in 2013, and more recent regulations that mandate NHS Trusts to apply sustainability and social value criteria when buying goods and services (NHS England Citation2022). We limit our investigation to the UK context to control for possible confounding effects attributable to differences in country-level institutional factors influencing social value procurement.

We contribute to public management literature on social value (e.g. George et al. Citation2023; Jain et al. Citation2020; Osborne et al. Citation2022) by showing how strategic public procurement helps in achieving socio-economic and environmental outcomes. Specifically, we develop a set of propositions focusing on procurement strategies, structures, practices, capabilities, and performance evaluation approaches that AIs mobilize to create social value. We furthermore extend the literature on social value-oriented procurement (e.g. Wontner et al. Citation2020) by positioning a unified framework for analysing procurement-based strategies, processes and practices. We show, in particular, how AIs translate their social value goals and policies into suitable procurement strategies. In addition, we add to prior research stressing place-based specificities (Uyarra, Ribeiro, and Dale-Clough Citation2019) by demonstrating that AIs define social value themes and outcomes in line with local priorities. They also join regional collaborative networks to share resources and expertise in support of social value procurement implementation.

Literature review

Social value creation in public administration

Public management literature has highlighted the different aspects of social value beyond the economic dimension. Quélin et al. (Citation2017) observe that the notions of value in general management and public management literature are converging and incorporate wider social, environmental, and economic benefits to citizens. This is a key premise in the UK context, as clearly stated in the Public Services (Social Value) Act which came into force in January 2013. Yet, public management scholars acknowledge a lack of a singular definition of social value and the existence of different interpretations of the concept (Dayson Citation2017).

To bring more clarity, recent studies have provided encompassing frameworks setting the stage for public management research on social value. For example, Jain et al. (Citation2020) discuss the meaning, forms, and process of social value creation, arriving at a typology of social value: action-driven, outcomes-driven, sustainability-driven and pluralism-driven. Furthermore, Osborne et al. (Citation2022) propose an integrative framework for value creation in public service delivery using an ecosystem metaphor. They define different levels of value creation (macro, meso, micro, sub-micro) and discuss the different forms of value (e.g. value-in-society) and how these are created during the public service delivery process. George et al. (Citation2023) examine the strategic management of social responsibilities and find that most US universities are unable to translate their strategic plans into concrete organizational structures and initiatives to support implementation of their social value strategies.

Yet, the aforementioned studies do not explicitly examine the role of public procurement in the social value creation process. While public management research acknowledges that public procurement can help achieve sustainability, social inclusion, and community development goals (Jain et al. Citation2020), it offers scant empirical insights regarding the underlying procurement strategies and practices. Increasing our understanding in this area is important because public buying organizations are well positioned to influence social value delivery, either directly or through partnerships with private-sector suppliers (Karaba et al. Citation2022). The public procurement literature, on the other hand, has only recently started to emphasize social value aspects – while scholars predominantly focus on cost efficiency and compliance aspects (Malacina et al. Citation2022), a limited number of studies have sought to draw links between public procurement and social value creation.

Public procurement and social value

Public procurement can be used strategically to promote social and environmental sustainability and economic development goals (Harland et al. Citation2019). Strategic public procurement influences social outcomes and local community benefits (Amann et al. Citation2014; Ambe Citation2019; Preuss Citation2009; Vluggen et al. Citation2020; Wontner et al. Citation2020). Socially-oriented procurement refers to the acquisition of products and services to promote, either directly or indirectly, desirable social outcomes (Furneaux and Barraket Citation2014; Hafsa, Darnall, and Bretschneider Citation2022).

Social value objectives can be considered at different stages of the procurement process: need identification, supplier selection, contracting and supplier evaluation. At the early stages of need definition and specification of requirements, consultation within the buying organization and along multiple (local) stakeholders to define relevant social challenges is necessary (Malacina et al. Citation2022; Uyarra, Ribeiro, and Dale-Clough Citation2019). Supplier selection processes may entail adopting an expanded view of the supply market and explicit consideration of social enterprises and third-sector organizations, either as suppliers or as actors that help monitor supplier compliance and support the implementation of social goals (Furneaux and Barraket Citation2014; Vluggen et al. Citation2020). Social and environmental outcomes can be reflected in supplier selection criteria and contractual performance objectives (Amann et al. Citation2014). Contract design and management practices include embedding social and environmental sustainability clauses in contracts, using reserved markets for employment opportunities, and assessing the social impacts of procurement (Bernal, San-Jose, and Retolaza Citation2019).

The uptake of social value-focused procurement is facilitated by targeted laws and policies seeking to promote social outcomes. A notable example beyond the UK Social Value Act is the Social Return on Investment (SROI) initiative in the Dutch public sector (Opoku and Guthrie Citation2018b; Vluggen et al. Citation2020). These policies form the institutional context within which public buying organizations operate and create value (Osborne et al. Citation2022).

Despite the interest in implementing socially-oriented public procurement, research suggests that these practices are still nascent (e.g. Higham et al. Citation2018; Troje and Andersson Citation2020), and that their implementation is problematic. For instance, Wontner et al. (Citation2020) find that procurement professionals are reluctant to implement social value criteria in tenders because they perceive this practice risky in terms of leading to legal challenges. Tensions between contract awards to SMEs or third-sector organizations, and synergies arising from centralized procurement inhibit implementation (Wontner et al. Citation2020). Budgetary constraints and the enforcement of standardization and cost efficiency imperatives are also at odds with procurement strategies seeking to achieve local community benefits and social goals (Uyarra, Ribeiro, and Dale-Clough Citation2019). Other issues include a lack of standardized practices and low level of institutionalization, regulatory barriers, weak incentives, risk aversion by procurement professionals and limited awareness of socially-oriented procurement (e.g. Bernal, San-Jose, and Retolaza Citation2019, Gidigah et al. Citation2022; Troje and Andersson Citation2020).

In sum, the literature shows how social value considerations are embedded at different stages of the procurement process. It also suggests that the uptake and implementation of social value procurement face important challenges (Higham et al. Citation2018; Uyarra, Ribeiro, and Dale-Clough Citation2019). Despite these contributions, the literature in this area remains limited and lacks an integrative analytical framework to study how public procurement strategies, processes and practices promote social value creation. In what follows, we develop a conceptual framework which is grounded on public management and public procurement literatures.

Public procurement for social value: a conceptual framework

Prior public management research has examined how public administrations create social value – Jain et al. (Citation2020) and Osborne et al. (Citation2022), as discussed earlier, offer frameworks that define social value and set out the overarching processes leading to its creation. We use these two studies to position our research. Specifically, our study relates to Jain’s et al. (Citation2020, 886) resource mobilization stage, given that procurement typically mobilizes internal and external resources (e.g. suppliers and related knowledge and capabilities) in public sector supply chains. We also position our study at the meso-level of Osborne’s et al. (Citation2022) Public Service Ecosystem, where value is created ‘in-production’ by organizational actors and networks and related service processes, rules, and norms. Beyond ‘value-in-production’, public service delivery can indirectly impact society more widely (‘value-in-society’).

More broadly, we ground our study on the concept of strategic management as used in public administration (Ferlie and Ongaro Citation2022). Bryson and George (Citation2020, 1) define strategic management as ‘an approach to strategizing by public organizations or other entities that integrates strategy formulation and implementation, and typically includes strategic planning to formulate strategies, ways of implementing strategies, and continuous strategic learning. Strategic management can help public organizations or other entities achieve important goals and create public value’. Strategic management is used as an encompassing term moving from planning to implementation ‘through, for instance, organizational design, resource management, performance measurement, and change management’ (p. 3). In this sense, strategic management is also linked to implementation issues through a set of concepts, processes, tools, techniques, practices, and structures that help produce desired results (Bryson and George Citation2020; George et al. Citation2023).

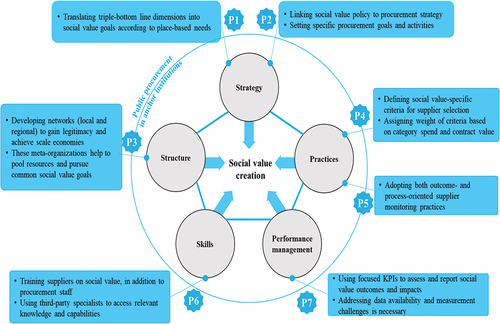

Public management literature has long borrowed concepts originating in private sector settings, while stressing the broader scope of public administration activity. Bryson and George, for instance, draw conceptually on Mintzberg et al. (Citation2020); while Walker (Citation2013) draw on Miles and colleagues (Miles et al. Citation1978). In our study, we develop our preliminary conceptual framework using Galbraith’s (Citation2002) star model. The model summarizes key design and implementation aspects controllable by public sector managers, specifically in the procurement domain. We essentially contextualize the star model to define the key decision areas that public buyers must consider concerning social value procurement. Based on prior research (Patrucco, Luzzini, and Ronchi Citation2017b; Spina et al. Citation2013), our framework captures five dimensions of public procurement practice: strategy, structure, practices, skills, and performance management. Because the public procurement literature has already incorporated the concept of strategic management (as used in public management), refers directly to public procurement studies for each of the five dimensions, including examples of studies that address multiple dimensions.

Table 1. Public procurement for social value: key conceptual dimensions.

Method

Given the scant empirical research on social value-oriented procurement strategies, we adopted a multiple case study design (Barratt, Choi, and Li Citation2011; Ketokivi and Choi Citation2014). Case-based research is suitable for empirical investigations of a contemporary phenomenon (Yin Citation2009). It allowed us to understand social value-focused procurement, a relatively immature phenomenon (Edmondson and McManus Citation2007), in the context of UK anchor institutions. We selected the UK public sector context because of the relevance of the Social Value Act, which requires public sector managers to consider social, economic and environmental benefits in their procurement and commissioning activities. The Act provides a regulatory framework and a set of guidelines that public procurement professionals follow.

We focus on Metropolitan Councils and NHS Trusts as two main types of AIs that are required to embed social value in their procurement activities, in contrast to other types (e.g. universities) where social value procurement initiatives are still voluntary. Metropolitan Councils are local government authorities running most local services, including schools, social services, waste collection and roads. They include major cities such as Manchester and Leeds but exclude London Councils, which have a separate local government structure. NHS Trusts (hospitals) provide secondary care services and are seen as impactful public-sector AIs that contribute to achieving social value and sustainability outcomes (NHS England Citation2022).

Our case selection followed a criterion sampling logic (Patton Citation2002): we sampled AIs with clearly stated social value objectives and related policies. We examined all Councils and NHS Trusts and selected those that could be considered the most active on social value and reported on their social value procurement initiatives. We additionally considered practicalities regarding data availability and completeness – several AIs publish only limited information regarding their social value procurement initiatives. In total, we selected 17 cases: 10 cases of Councils and 7 cases of NHS Trusts.

The research followed a theory elaboration approach (Ketokivi and Choi Citation2014), building on the conceptual framework defined above. Using abductive reasoning (Ketokivi Citation2006), we iterated between the framework () and our empirical data. Our initial empirical observations pointed to AIs seeking to connect their social value definitions, goals and policies to procurement strategies, which are in turn linked to specific needs for the development of appropriate structures, skills and performance management systems. We thus drew on Galbraith’s (Citation2002) model as our initial analytical frame. We subsequently elaborated on the framework based on our cross-case findings, for instance, the tendency of AIs to form inter-organizational networks of support. The result of this process was the development of seven research propositions linked to an augmented framework (see Discussion section).

We collected data through 67 publicly available sources, notably the organizations’ webpages as well as policy and strategy documents that the AIs produced. These policy documents included procurement strategies, sustainability and social value policies, social impact reports and supplier guidelines. These official documents have been reviewed and vetted by public servants, thus ensuring data validity. Our data included also reports produced by independent, credible organizations such as the Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES); the Social Value Portal; regional organizations focusing on social value such as the Greater Manchester Social Value Network; regional procurement hubs (e.g. STAR Procurement); and national bodies such as NHS England. Details of all data sources are provided in the Online Supplement. Overall, the use of secondary data is a well-established practice (Calantone and Vickery Citation2010; Ellram and Tate Citation2016). Ellram and Tate (Citation2016) argue that using secondary data can reduce researchers’ biases and preconception, creating more meaningful and generalizable results. Furthermore, our use of different types of secondary data, as mentioned above, helped us ensure data completeness and validity. It also enabled us to achieve data triangulation – for instance, we used CLES reports to complement data on performance measurement aspects (see the ‘social value KPIs’ dimension).

The data was coded and analysed using a coding scheme (see Appendix 1) we developed by iterating between our data and the literature (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002; King Citation1998). Specifically, our initial within-case analysis resulted in several open codes (Strauss and Corbin Citation1990) related, for instance, to social value definition, supplier selection criteria and social value-specific job roles within procurement departments. We progressively reduced and refined these open codes as we started searching for patterns across the cases (Yin Citation2009). For example, we dropped the code related to job roles because this was relevant only to a small subset of the cases. On the other hand, we retained the code ‘procurement collaboration’ as we observed that AIs seek collaboration, both internally and with other organizations. As a next step, we grouped these codes into higher-order categories using axial coding (Strauss and Corbin Citation1990) and iterating with the conceptual framework themes i.e. strategy, structure, practices, skills, and performance management. Appendix 2 shows the resulting codes. The Online Supplement offers details of the within-case analysis, while the results of the cross-case analysis are presented in the next section.

Cross-case analysis and findings

We report our findings across the 17 cases of anchor institutions (AIs) we studied, aided by . We identified similarities and differences across the cases regarding the definition of social value, the link between social value and procurement strategy, tendering and supplier management practices, collaboration among AIs, capacity building, and impact assessment of social value procurement. We synthesize our findings in the form of research propositions.

Table 2. Cross-case analysis: how public procurement in anchor institutions promotes social value creation.

Social value definition and key themes

All but one of the AIs in our sample formally define social value (see ). This is not surprising as we studied AIs who declare their social value objectives. However, we found differences in these definitions across the sample. In 11 out of the 16 cases where a definition is available, social value is referred to as the ‘wider’ benefits to (local) communities, beyond the ‘value for money’ imperative which is typical for public buying organizations. While social value is thus essentially seen as ‘value added’, three AIs explicitly stress that social value is not ‘an add-on’ and should be embedded into their daily activities. Moreover, 10 AIs define social value in terms of ‘triple-bottom-line’ objectives related to economic development, social welfare and environmental protection, e.g.:

‘A process whereby organisations meet their needs for good, services, works and utilities in a way that achieves value for money on a whole life basis, in terms of generating benefits not only to the organisation, but also to society and economy, whilst minimising damage to the environment’. [Stockport Borough Council]

Another notable finding is that NHS Trusts, as compared to Councils, emphasize the health and wellbeing benefits for local residents (). This is in line with the NHS’s vision to promote the role of NHS providers as AIs driving improvements in health outcomes in their local communities (Reed et al. Citation2019). For example:

‘Social value is the opportunity for the organisation to provide “added value” to benefit our local society, by enhancing people’s lives through community support, inclusivity, economic and environmental sustainability through activities that improve health and wellbeing’. [Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust]

Overall, our cross-case findings suggest that AIs employ definitions of social value which share common characteristics, such as the reference to triple-bottom line goals. This is likely because AIs refer to nationally accepted frameworks such as the UK Government’s Social Value Model. Importantly, however, we found that the operationalization of these definitions is a lot more diverse. Although many AIs in our sample use the Social Value Portal’s National Themes, Outcomes and Measures (TOMs) framework or other relevant ones (e.g. Social Value Quality Mark), they opt for themes and outcomes that are customized to local needs and priorities and/or place-based specificities. In doing so, they clearly identify salient local issues and define initiatives and activities that meet citizens’ needs. For example, Trafford Council has customized the Greater Manchester Social Value Framework to its priorities and identified six local themes: a) Promote employment and economic sustainability, b) Raise the living standards of local residents, c) Promote participation and citizen engagement; d) Build the capacity and sustainability of the voluntary and community sector, e) Promote equity and fairness, and f) Promote environmental sustainability.

In a similar vein, all the NHS Trusts in our sample have developed customized social value themes and outcomes based on national frameworks such as the Social Value Model. For instance, the Dorset County Hospital has defined six key areas (e.g. local investment, local employment and good employer) following its Social Value Pledge.

In sum, we find that AIs explicitly define social value emphasizing (wider) economic, social, environmental and wellbeing benefits to local communities. Clear definitions form the basis for developing a social value-focused procurement strategy (Uyarra, Ribeiro, and Dale-Clough Citation2019). We also find that AIs translate the rather generic triple-bottom line dimensions into concrete social value themes and outcomes, in line with local needs and priorities. Such customized outcomes allow AIs to contextualize generic social value frameworks, turning them into actionable procurement goals and plans (Malacina et al. Citation2022). Hence, we propose:

Proposition 1:

Anchor institutions translate abstract triple-bottom-line dimensions into specific social value themes and outcomes befitting their place-based needs and priorities.

Social value policy and procurement strategy

Our cross-case results show a strong connection between the implementation of social value policies of AIs and their procurement strategies. More specifically, in 13 of the 17 cases, there is evidence that AIs seek to create social value through their procurement strategy and related activities (). Furthermore, three AIs also refer to the role of commissioning (i.e. planning and sourcing public services) in addition to that of procurement. The majority of AIs in our sample explicitly state that they seek to implement their social value policies and achieve related goals through their strategic procurement initiatives e.g.:

‘We have developed a Social Value Commitment for the city […] the principles set out below now shape all of the commissioning and procuring that we do as a Council. Although our ambition is to create Social Value through all Council activity, we recognise that the way we buy goods, works and services for the city is a very important lever for Social Value’. [Newcastle City Council]

In general, these findings are consistent with prior research suggesting that procurement and commissioning are key mechanisms through which AIs can create social value in local communities (e.g. Bernal, San-Jose, and Retolaza Citation2019; Ehlenz Citation2018). A closer look at the evidence (see also the ‘Online Supplement’) furthermore reveals that pursuing social value outcomes through strategic procurement entails: a) either embedding social value goals into broader procurement strategies or b) developing social value-specific strategic procurement initiatives. In the former case, AIs define clear and measurable social value objectives in their general-purpose procurement strategies. In other words, social value is one key element of their procurement strategy (e.g. see Doncaster City Council and Leeds Teaching Hospitals). In the latter case, AIs craft strategic procurement initiatives specific to the Council’s social value agenda. Bradford City Council is an illustrative case of this approach, as it has developed social value-focused procurement policies and practices championed by a cross-functional steering committee. Regardless of which of the approaches above is used, AIs in our sample seek to translate social value outcomes into meaningful strategic procurement objectives and associated activities. These observations extend prior research suggesting a link between strategic public procurement and achieving social outcomes (Amann et al. Citation2014; Furneaux and Barraket Citation2014). We therefore propose:

Proposition 2:

When anchor institutions perceive strategic procurement as a key enabler for social value creation, they explicitly link their social value policy to their procurement strategy. This entails translating social value objectives into specific procurement goals and activities.

Collaborative networks for social value-oriented procurement

The cross-case findings suggest that AIs join inter-organizational networks and collaborate with like-minded organizations, mainly locally and regionally. More specifically, in 14 cases in our sample, AIs are members of local or regional networks (). Some of these networks focus on promoting social value specifically – examples include the Greater Manchester Social Value Network, the Salford Social Value Alliance and (healthcare-related) Sustainability Networks in Cheshire. We also found that five AIs in our sample are members of procurement-focused regional networks whose remit includes pursuing social value and sustainability goals. Examples of such procurement-oriented networks include the STAR Procurement shared service, whose members include Rochdale, Stockport, Tameside and Trafford Councils; the Lancashire Procurement Cluster; and the ‘Smart Together’ Procurement shared service based in the London area. In addition, we found that four AIs collaborate with specialist organizations, such as the Social Value Portal to access expertise and implementation support. Furthermore, four NHS Trusts explicitly state collaboration with other actors in regional Integrated Care Systems to pursue social value goals.

A key motivation for forming these collaborative networks focusing on social value (procurement) issues is the availability of resources – Councils and NHS Trusts often lack the financial and human resources to fully implement their social value policies and practices. Anchors can share this resource burden through collaboration. These networks also help AIs to increase their legitimacy, share effective practices and achieve economies of scale – the latter is particularly important in the case of procurement-focused clusters. These examples of collaborative networks are in line with what Gulati et al. (Citation2012, 573) refer to as meta-organizations: ‘networks of firms or individuals not bound by authority based on employment relationships, but characterized by a system-level goal’. Geographical proximity is an important characteristic of these collaborative anchor networks, as they all have well-defined geographical boundaries. These meta-organizations allow AIs in the same region to focus their efforts and resource investments around common goals and create social welfare for their local populations. Accordingly, we propose:

Proposition 3:

Anchor institutions collaborate with other entities and form meta-organizations to pursue common social value procurement goals, pool resources, improve practices, and gain legitimacy locally and regionally.

Tendering and supplier management practices for social value

Our cross-case findings show that AIs seek to engage directly with potential suppliers regarding social value issues, both before and during the tendering stage. We find that AIs use various means of engaging with suppliers to explain their social value requirements, raise awareness of upcoming contract opportunities and understand better what suppliers can offer in this respect. In only four cases in our sample AIs seem to limit such engagement to the actual tendering documents as a formal means of communicating their social value-related needs. In the rest of the cases, AIs use a mix of more informal ways to interact with suppliers, such as ‘meet the buyer’ events, supplier consultations, and sessions focusing on presenting contract opportunities to suppliers, including to small firms and voluntary/third-sector organizations (see ). We also find that AIs might also opt to develop ‘supplier guidance’ resources to help bidders to understand key requirements in relation to tender opportunities. However, this was relevant in only four cases of Councils. Notably, a limited number of AIs in our sample (Rotherham, Salford, Stockport Councils and Dorset Hospital) seek to early engage with suppliers and ‘soft-test’ market offerings to ensure that social value requirements are feasible to implement. These early interactions also allow suppliers to understand better what is required and to identify ways to build capacity according, e.g.:

‘In engagement and consultation with potential providers, we focus not only on what we intend to buy from them, but also on the ways they run their organisation. By understanding their ethos, processes, local connections and plans for the future, we can make the strongest connections between what they can achieve and who will benefit’. [Newcastle City Council]

Regarding supplier selection criteria, we found that in all but one case in our sample, AIs include in tender documents social value-specific requirements that bidders must satisfy, in addition to conventional cost, quality and delivery requirements (). Evidence across the cases suggests that the weighting of social value – often presented as a sub-component of the ‘quality’ component” of the tender – varies between 10% and 20%. This observation applies to both Councils and NHS Trusts. For both subsets of AIs, embedding social value criteria for supplier selection is driven by requirements based on the Social Value Act and the UK Government’s Social Value Model. In the case of NHS Trusts, for instance, there is an NHS England and Improvement mandate (linked to the UK Government’s Social Value Model) to have a minimum 10% social value component in tenders. However, we also identified some differences between the cases. First, in four of the Council cases the social value component applies for contacts above a certain threshold, and in one of the cases (Rotherham Council) a 20% weight applies for contracts above £100,000 in value. NHS Trusts, on the other hand, do not specify any contract value thresholds. For instance, Stockport Council stipulates that social value must be included:

[…] in every procurement opportunity where relevant and proportionate and attribute a minimum weighting of 15% with an overall target of 20%, in all competitive procurement activity with a total agreement value in excess of £25k.

Second, in five cases the decision about the allocation of percentage weight depends on the spend category or the characteristics of the procurement project (). Third, our detailed analysis also reveals that in a few cases (e.g. Manchester City Council and Leeds Hospitals) AIs use tenders to urge bidders to consider how to cascade social value requirements along their supply chains to create a ‘multiplier effect’. However, this approach does not seem to be prevalent across our cases. Notwithstanding these nuances, the majority of AIs in our sample do apply social value criteria for supplier selection regardless of contact value, spend category or procurement project features. Based on these findings, we propose:

Proposition 4:

Anchor institutions embed social value-specific criteria for supplier selection in tenders as a means of incentivizing suppliers to fulfil related requirements. The salience of social value requirements (percentage weight) is contingently determined depending on spend category and contract value.

Regarding contract management, we find that AIs employ multiple approaches that appear to co-exist: from emphasizing supplier compliance with social value requirements as a key outcome to focusing on more process-oriented approaches entailing the adoption of contract management tools and collaboration. More specifically, in 11 cases, AIs stress supplier compliance as an expected outcome of contract management. The aim is to highlight legal requirements and ensure that suppliers deliver on their contractual promises, e.g.:

‘If successful, it is very likely that you will be contractually obliged to deliver on your Social Value commitments promised, so ensure that they are realistic and deliverable. Agree with the buying organisation how and when you will report on your progress in delivering your Social Value commitments during the contract’. [Tameside Council]

In the rest of the cases, by contrast, the emphasis is on mechanisms and tools such as contract review mechanisms, social value monitoring committees, supplier performance reporting tools and supplier relationship management (). Accordingly, we propose:

Proposition 5:

Anchor institutions employ both outcome- and process-oriented contract management practices: those emphasizing supplier compliance with social value requirements and specific mechanisms and tools for monitoring supplier progress towards performance goals.

Developing skills and capabilities for social value-oriented procurement

Our cross-case findings suggest that AIs invest in developing skills and capabilities for social value procurement. In all 17 cases in our sample, we found evidence that AIs have initiated training and mentoring activities for their procurement and commissioning staff. However, we identified many different approaches across the cases, with key activities spanning from sets of guidelines, case studies, workshops and best-practice sharing events to specific tool kits supporting tender design and contract management (). For example, Rotherham and Newcastle Councils have developed specific guidelines that support their procurement staff to identify and report opportunities for social value creation:

‘We have developed a set of social value opportunity identification (SVOI) questions which we use to identify social value opportunities where appropriate’. [Newcastle City Council]

Seven AIs in our sample seek external support for training from specialist organizations such as the Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES) and the Social Value Portal, a social impact company. CLES, for instance, has worked with Leeds and Manchester Councils to educate procurement staff and help them assess the impact of their social value procurement strategies over time. Other AIs use the Social Value Portal’s guidelines and toolkits, including the ‘TOMs’ framework, for specification, supplier selection and performance management tasks. Four AIs in our sample seek to access knowledge and capabilities from collaborative networks such as the STAR Procurement and the Salford Social Value Alliance, e.g.:

‘Salford Social Value Alliance have created a Toolkit of general and legal information, case studies and FAQs to help you get to grips with social value. There is information for providers of services, voluntary and community groups, businesses, commissioners and procurement teams’. [Salford City Council]

We also found that approximately a third of the AIs in our sample seek to extend such training and education activities to their (possible) suppliers (). This is because it is deemed important for suppliers to understand social value requirements and how to embed them into their bids. It is notable, however, that none of the NHS Trusts engage in supplier training, and the practice is adopted only by Councils. Bradford City Council, for instance, developed a Social Value tool kit that seeks to provide guidance and support suppliers:

The AIs in our sample with less well-developed supplier guidelines and toolkits (e.g. Stockport Council) tend to refer suppliers to external specialists, such as the Social Value Portal and STAR Procurement, as a source of expertise and support. In sum, our findings show that AIs seek to raise awareness of social value procurement, develop standardized practices and build capacity both within public buying organizations and suppliers, thereby addressing some of the reported implementation challenges (Bernal, San-Jose, and Retolaza Citation2019; Troje and Andersson Citation2020). Accordingly, we propose:

Proposition 6:

Anchor institutions educate and train procurement staff and suppliers to support social value procurement implementation. While some anchor institutions invest in development of capabilities internally, others access relevant knowledge and capabilities from external entities.

Impact assessment of social value-oriented procurement

Our cross-case analysis reveals that using key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure supplier performance and assess social value outcomes and impacts is prevalent – in only one case (Stockport), we could not find relevant evidence. We identified two main approaches regarding the use of KPIs: while about half of the AIs in our sample employ rather ‘narrow’ sets of KPIs focusing, for instance, on the percentage of local spend, jobs and environmental outcomes, the other half of organizations deploy a comprehensive suite of KPIs covering diverse, triple-bottom line objectives (see ). It is notable that two NHS Trusts in our sample (Lancashire and Wirral) refer to ‘key value indicators’ (KVIs) instead of KPIs, which reflects their engagement with the Social Value Quality Mark accreditation process.

Our cross-case findings also suggest that AIs assess, document and report social value outcomes and impacts: 14 AIs in our sample engage in impact assessment activities. At the same time, three organizations state their intent but provide no related evidence (). Eight of the 14 AIs that assess and report impacts do so for relatively small sets of outcome metrics. This reflects their narrowly defined sets of KPIs, as described above. Anchor institutions, for instance, report improvements in terms of the percentage of spend with local suppliers, creation of jobs and apprenticeships and increased spend with SMEs:

‘In 2019/20, Council contracts included over 100,000 hours of voluntary and community work, provided through our suppliers to support Manchester communities. […]. We spent £353 m with Manchester based suppliers, with an estimated £143 m being invested back into the Manchester economy’. [Manchester City Council]

Although AIs assess and report social value outcomes and impacts, our cross-case findings also suggest that these organizations face data availability and measurement challenges that limit their ability to monitor and assess effects more comprehensively (). We observed such challenges, especially in five cases of NHS Trusts and two Councils (Stockport and Trafford). Data availability issues do not only result from a lack of systematic data collection efforts but also from the fact that AIs likely focus their data collection and analysis activities only in certain performance areas or supplier contracts that are deemed important (e.g. see East London and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trusts). In addition, measurement challenges make a systematic comparison of social value impacts among AIs very difficult. Specifically, there are differences in the financial year that AIs use as baseline, and the amount of total spend available to each one. For example, some of the Councils in our sample concentrate their measurement and reporting on the top 300 suppliers by spend. In contrast, others consider the total spend regardless of supplier market share. There are also geographical or socio-economic idiosyncrasies that can influence how AIs measure and report on certain outcomes. For instance, Newcastle City Council also reports the percentage of spend with suppliers in the (North-East) region. In contrast, others such as Leeds City Council and Manchester City Council do not.

In sum, our findings suggest that AIs seek to assess and showcase the impacts of social value and justify the added value of strategic procurement beyond cost efficiency imperatives (Uyarra, Ribeiro, and Dale-Clough Citation2019). At the same time, however, AIs appear to be focused on certain performance areas or suppliers and face data availability and measurement issues. Accordingly, we propose:

Proposition 7:

Anchor institutions assess and report social value outcomes using a focused set of indicators. A more comprehensive and systematic approach to impact assessment and benchmarking requires overcoming data availability and measurement challenges.

Discussion and conclusions

Our empirical study of Metropolitan Councils and NHS Trusts unveils the strategies, processes, and practices through which public procurement creates social value. We elaborate on the five dimensions of strategic public procurement () based on the cross-case findings. presents our augmented framework and related propositions.

elaborates the initial framework () by elucidating the following aspects of social value procurement. First, we show that the translation of abstract triple-bottom line objectives into social value themes and outcomes directly relevant to local needs and priorities (Uyarra, Ribeiro, and Dale-Clough Citation2019) are critical precursors of implementing social value-focused procurement. We also highlight the importance of linking AIs’ social value policies to their procurement strategy (Malacina et al. Citation2022), such that social value objectives translate into specific procurement goals and activities. Second, creating inter-organizational collaborative networks (locally and regionally) is an important structural mechanism hitherto underplayed, as existing research tends to emphasize intra-organizational structures (George et al. Citation2023). These networks facilitate strategy implementation by enabling resource and knowledge sharing; they can thus be seen as a specific form of meta-organization (Gulati, Puranam, and Tushman Citation2012) supporting the achievement of social value goals. Third, public-sector AIs employ social value-specific supplier selection criteria and differentiate the salience of such criteria depending on the procurement situation at hand. They also employ both outcome- and process-oriented contract management practices to monitor supplier progress and compliance. Such supplier selection and management practices also support the implementation of AIs’ strategies to create social value (George et al. Citation2023). Fourth, AIs seek to train suppliers, in addition to procurement professionals (Troje and Andersson Citation2020), and tend to use third-party expertise to help them implement social value procurement. Fifth, despite AIs’ use of focused KPIs to assess supplier performance, data availability and measurement issues seem to restrict the breadth and depth of activities to assess social outcomes and impacts.

More generally, our augmented framework builds on the public management literature on strategic planning and management (Bryson and George Citation2020; George et al. Citation2023; Walker Citation2013): it shows how social value policies of AIs translate into specific procurement processes, activities, and inter-organizational structures to facilitate strategy implementation. We add to the meso-level analysis of value creation, as conceptualized by Osborne et al. (Citation2022), by showing that the inter-organizational networks involved in public service delivery include supplier firms that not only provide resource inputs but also actively contribute to social value creation. In other words, procurement of goods and services that are essential for the delivery of public services also has an indirect, positive impact on local communities. In this sense, we extend the ‘value-in-society’ concept (Osborne et al. Citation2022) to social value procurement settings. In addition, we find that AIs form collaborative networks to build capacity for social value creation through procurement, thereby extending Osborne et al’.s (Citation2022) conceptualization of networks revenant for public service delivery.

Research implications and contributions

Our study makes three contributions. First, we extend public administration research on social value (e.g. George et al. Citation2023; Jain et al. Citation2020; Osborne et al. Citation2022) by offering theoretical and empirical insights with respect to the role of procurement in creating social value. We build on the concept of strategic management, as used in public administration (Bryson and George Citation2020; George et al. Citation2023), to show how AIs use public procurement strategically to create social value. Drawing on prior literature on strategic sourcing and public procurement (Malacina et al. Citation2022; Spina et al. Citation2013; Patrucco et al. Citation2017a) and on the case findings, our augmented framework () and set of propositions reveal specific procurement strategies, inter-organizational structures, practices, capabilities, and performance evaluation approaches that AIs mobilize to promote social value creation.

Second, we contribute to the literature on social value-oriented public procurement (e.g. Vluggen et al. Citation2020; Wontner et al. Citation2020) by positioning an integrative framework for analysing the mechanisms through which public procurement creates social value. Prior research has examined how social value is embedded into the different stages of the procurement process (e.g. Bernal, San-Jose, and Retolaza Citation2019; Furneaux and Barraket Citation2014). We extend this literature by demonstrating the links between the social value policies of AIs on the one hand, and their procurement strategies on the other. We also add to research on implementation challenges (e.g. Gidigah et al. Citation2021; Troje and Andersson Citation2020) by showing that training initiatives (both for procurement professionals and suppliers) and the formation of inter-organizational support networks help to raise awareness of social value procurement, and to codify and institutionalize related procurement practices.

Third, we extend prior research by elaborating on the role of place-based specificities (Uyarra, Ribeiro, and Dale-Clough Citation2019) in designing and implementing social value-oriented procurement strategies. Specifically, we show that AIs seek to translate widely accepted definitions of social value and associated frameworks (e.g. TOMs) into specific themes and outcomes based on their local needs and priorities. These themes and outcomes subsequently translate into specific strategic procurement goals and activities. AIs also seek to amplify the impact of their social value procurement activities by joining networks of local and regional actors who pursue similar objectives. These collaborative networks are useful for pooling resources, sharing knowledge and best practices, and building legitimacy. Geographical proximity and common socio-economic challenges are key drivers of collaboration.

Implications for practice and policy

Our study has implications for public procurement practice and policy. The augmented framework () and set of propositions can guide the efforts of public managers within public-sector AIs in systematically articulating the design, implementation and evaluation of their social value-focused procurement strategies. Regarding the design phase, a key issue concerns the definition of social value in terms of concrete themes and outcomes in coordination with relevant stakeholders. An explicit social value policy that is embedded in the organization’s procurement strategy is a key enabler for consistently selecting suitable procurement practices. Regarding the implementation phase, key activities include a meaningful engagement with (existing and prospective) suppliers, the design of tenders with an explicit social value component, and a robust contract management approach to monitor supplier performance against social value requirements and goals. In the evaluation phase, public managers need to identify strategies for monitoring and reporting the impact of social value procurement. Given resource and capacity constraints, building alliances with specialist organizations who can support impact assessment exercises can be an effective approach.

We also offer policy-related insights regarding the investment needed to support strategies, practices and skill sets conducive to social value-oriented public procurement. A key area for improvement is investments in data collection and measurement systems to assess social value outcomes and impacts more comprehensively. Another improvement area concerns education and further support of suppliers, especially SMEs, social enterprises and minority suppliers, so that they understand and embrace social value requirements and are well-equipped to respond to tender opportunities accordingly. While some third-party, specialist organizations, such as the Social Value Portal, seek to bridge this gap in the UK context, a more systematic approach to educating and training suppliers is required.

Limitations and future research

Our study presents certain limitations. First, our analysis is grounded in the context of UK Metropolitan Councils and NHS Trusts, which, arguably, might place limits on the generalizability of the findings. Future research should expand its scope to consider other types of AIs and other countries, potentially with different institutional environments. Second, our empirical study relies on secondary data sources, notably the websites of AIs, policy documents produced by these organizations and reports from third-party entities. Despite our data triangulation efforts, we acknowledge that there is room for further research using primary data (e.g. interviews) and other types of secondary data (e.g. contract award information) to strengthen further validity. Third, our analysis offered insights into external alliances and network organizations supporting the implementation of social value procurement strategies. Further research is needed to understand how collaborative anchor networks contribute to social value creation, and what conditions influence their effectiveness. Our study offers, nevertheless, a basis for further research on how the power of procurement can be harnessed to drive social outcomes and enable the transformations required to tackle grand societal challenges more generally (Knight et al. Citation2022).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (91.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2277814

References

- Amann, M., J. Roehrich, M. Eßig, C. Harland, Stefan Schaltegger, and Roger Burritt. 2014. “Driving Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Public Sector: The Importance of Public Procurement in the European Union.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 19 (3): 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-12-2013-0447.

- Ambe, I. M. 2019. “The Role of Public Procurement to Socio-Economic Development.” International Journal of Procurement Management 12 (6): 652–668. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPM.2019.102934.

- Ancarani, A., F. Arcidiacono, C. Di Mauro, and M. D. Giammanco. 2021. “Promoting Work Engagement in Public Administrations: The Role of Middle managers’ Leadership.” Public Management Review 23 (8): 1234–1263. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1763072.

- Barratt, M., T. Y. Choi, and M. Li. 2011. “Qualitative Case Studies in Operations Management: Trends, Research Outcomes, and Future Research Implications.” Journal of Operations Management 29 (4): 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2010.06.002.

- Bernal, R., L. San-Jose, and J. L. Retolaza. 2019. “Improvement Actions for a More Social and Sustainable Public Procurement: A Delphi Analysis.” Sustainability 11 (15): 4069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154069.

- Brammer, S., and H. Walker. 2011. “Sustainable Procurement in the Public Sector: An International Comparative Study.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 31 (4): 452–476. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571111119551.

- Bryson, J., and B. George. 2020. “Strategic Management in Public Administration.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.139.

- Calantone, R. J., and S. K. Vickery. 2010. “Introduction to the Special Topic Forum: Using Archival and Secondary Data Sources in Supply Chain Management Research.” The Journal of Supply Chain Management 46 (4): 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2010.03202.x.

- Choi, D., and J. Park. 2021. “Local Government as a Catalyst for Promoting Social Enterprise.” Public Management Review 23 (5): 665–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1865436.

- Dayson, C. 2017. “Evaluating Social Innovations and Their Contribution to Social Value: The Benefits of a ‘Blended value’ Approach.” Policy & Politics 45 (3): 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557316X14564838832035.

- Dimitri, N. 2013. ““Best value for money” in procurement.” Journal of Public Procurement 13 (2): 149–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-13-02-2013-B001.

- Dubois, A., and L. E. Gadde. 2002. “Systematic Combining: An Abductive Approach to Case Research.” Journal of Business Research 55 (7): 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8.

- Edmondson, A. C., and S. E. McManus. 2007. “Methodological Fit in Management Field Research.” Academy of Management Review 32 (4): 1246–1264. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.26586086.

- Ehlenz, M. M. 2018. “Defining University Anchor Institution Strategies: Comparing Theory to Practice.” Planning Theory & Practice 19 (1): 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1406980.

- Ellram, L. M., and W. L. Tate. 2016. “The Use of Secondary Data in Purchasing and Supply Management (P/SM) Research.” Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 22 (4): 250–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2016.08.005.

- Ferlie, E., and E. Ongaro. 2022. Strategic Management in Public Services Organizations: Concepts, Schools and Contemporary Issues. London: Routledge.

- Furneaux, C., and J. Barraket. 2014. “Purchasing Social Good(s): A Definition and Typology of Social Procurement.” Public Money & Management 34 (4): 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2014.920199.

- Galbraith, J. R. 2002. “Organizing to Deliver Solutions.” Organizational Dynamics 31 (2): 194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-2616(02)00101-8.

- Garton, P. 2021. “Types of Anchor Institution Initiatives: An Overview of University Urban Development Literature.” Metropolitan Universities 32 (2): 85–105. https://doi.org/10.18060/25242.

- George, B., M. J. Worth, S. Pandey, and S. Pandey. 2023. “Strategic Management of Social Responsibilities: A Mixed Methods Study of US Universities.” Public Money & Management 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.2197253.

- Gidigah, B. K., K. Agyekum, and B. K. Baiden. 2022. “Defining Social Value in the Public Procurement Process for Works.” Engineering, Construction & Architectural Management 29 (6): 2245–2267. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-10-2020-0848.

- Glas, A. H., M. Schaupp, and M. Essig. 2017. “An organizational perspective on the implementation of strategic goals in public procurement.” Journal of Public Procurement 17 (4): 572–605. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-17-04-2017-B004.

- Grandia, J., and J. Meehan. 2017. “Public Procurement as a Policy Tool: Using Procurement to Reach Desired Outcomes in Society.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 30 (4): 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-03-2017-0066.

- Gulati, R., P. Puranam, and M. Tushman. 2012. “Meta‐Organization Design: Rethinking Design in Interorganizational and Community Contexts.” Strategic Management Journal 33 (6): 571–586. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1975.

- Hafsa, F., N. Darnall, and S. Bretschneider. 2022. “Social Public Purchasing: Addressing a Critical Void in Public Purchasing Research.” Public Administration Review 82 (5): 818–834. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13438.

- Harland, C., J. Telgen, G. Callender, R. Grimm, and A. Patrucco. 2019. “Implementing Government Policy in Supply Chains: An International Coproduction Study of Public Procurement.” The Journal of Supply Chain Management 55 (2): 6–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12197.

- Higham, A., C. Barlow, E. Bichard, and A. Richards. 2018. “Valuing sustainable change in the built environment: Using SuROI to appraise built environment projects.” Journal of Facilities Management 16 (3): 315–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFM-11-2016-0044.

- Jain, P. K., R. Hazenberg, F. Seddon, and S. Denny. 2020. “Social Value as a Mechanism for Linking Public Administrators with Society: Identifying the Meaning, Forms and Process of Social Value Creation.” International Journal of Public Administration 43 (10): 876–889. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1660992.

- Karaba, F., J. Roehrich, S. Conway, and J. Turner. 2022. “Information Sharing in Public-Private Relationships: The Role of Boundary Objects in Contracts.” Public Management Review 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2022.2065344.

- Karjalainen, K. 2011. “Estimating the Cost Effects of Purchasing Centralization: Empirical Evidence from Framework Agreements in the Public Sector.” Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 17 (2): 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2010.09.001.

- Kauppi, K., and E. M. van Raaij. 2015. “Opportunism and Honest Incompetence: Seeking Explanations for Noncompliance in Public Procurement.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 25 (3): 953–979. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mut081.

- Ketokivi, M. 2006. “Elaborating the Contingency Theory of Organizations: The Case of Manufacturing Flexibility Strategies.” Production & Operations Management 15 (2): 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2006.tb00241.x.

- Ketokivi, M., and T. Choi. 2014. “Renaissance of Case Research as a Scientific Method.” Journal of Operations Management 32 (5): 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2014.03.004.

- King, N. 1998. “Template Analysis.” In Qualitative Methods and Analysis in Organisational Research, edited by G. Symon and C. Cassell, 118–134. London: Sage.

- Knight, L., W. Tate, S. Carnovale, C. Di Mauro, L. Bals, F. Caniato, J. Gualandris, et al. 2022. “Future Business and the Role of Purchasing and Supply Management: Opportunities for ‘Business-Not-As-usual’ PSM Research.” Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 28 (1): 100753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2022.100753.

- Knutsson, H., and A. Thomasson. 2014. “Innovation in the Public Procurement Process: A Study of the Creation of Innovation-Friendly Public Procurement.” Public Management Review 16 (2): 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.806574.

- Koppenjan, J., E. H. Klijn, S. Verweij, M. Duijn, I. van Meerkerk, S. Metselaar, and R. Warsen. 2022. “The Performance of Public–Private Partnerships: An Evaluation of 15 Years DBFM in Dutch Infrastructure Governance.” Public Performance & Management Review 45 (5): 998–1028. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2022.2062399.

- Kristensen, H. S., M. A. Mosgaard, and A. Remmen. 2021. “Circular Public Procurement Practices in Danish Municipalities.” Journal of Cleaner Production 281:124962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124962.

- Malacina, I., E. Karttunen, A. Jääskeläinen, K. Lintukangas, J. Heikkilä, and A.-K. Kähkönen. 2022. “Capturing the value creation in public procurement: A practice-based view.” Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 28 (2): 100745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2021.100745.

- McKevitt, D., P. Davis, R. Woldring, K. Smith, A. Flynn, and E. McEvoy. 2012. “An exploration of management competencies in public sector procurement.” Journal of Public Procurement 12 (3): 333–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-12-03-2012-B002.

- Miles, R. E., C. C. Snow, A. D. Meyer, and H. J. Coleman Jr. 1978. “Organizational Strategy, Structure, and Process.” The Academy of Management Review 3 (3): 546–562. https://doi.org/10.2307/257544.

- Mintzberg, H., B. Ahlstrand, and J. B. Lampel. 2020. Strategy Safari. London: Pearson UK.

- Murray, G. J. 2009. “Public Procurement Strategy for Accelerating the Economic Recovery.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 14 (6): 429–434. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540910995200.

- Newby, L., and N. Denison 2018. “Harnessing the Power of Anchor Institutions: A Progressive Framework.” Tool Kit. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Available at: https://democracy.leeds.gov.uk/documents/s181576/4%20Anchor%20Institution%20Progression%20Framework%20Toolkit.pdf.

- NHS England. 2022. “Applying Net Zero and Social Value in the Procurement of NHS Goods and Services.” 23 March 2022. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/publication/applying-net-zero-and-social-value-in-the-procurement-of-nhs-goods-and-services/.

- OECD. 2021. “Government at a Glance - 2021 edition: Public procurement.” Available at: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=107598.

- Opoku, A., and P. Guthrie. 2018a. “Education for Sustainable Development in the Built Environment.” International Journal of Construction Education and Research 14 (1): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/15578771.2018.1418614.

- Opoku, A., and P. Guthrie. 2018b. “The Social Value Act 2012: Current State of Practice in the Social Housing Sector.” Journal of Facilities Management 16 (3): 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFM-11-2016-0049.

- Osborne, S. P., M. Powell, T. Cui, and K. Strokosch. 2022. “Value Creation in the Public Service Ecosystem: An Integrative Framework.” Public Administration Review 82 (4): 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13474.

- Patrucco, A. S., T. Agasisti, and A. H. Glas. 2021. “Structuring Public Procurement in Local Governments: The Effect of Centralization, Standardization and Digitalization on Performance.” Public Performance & Management Review 44 (3): 630–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2020.1851267.

- Patrucco, A. S., D. Luzzini, and S. Ronchi. 2016. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Public Procurement Performance Management Systems in Local Governments.” Local Government Studies 42 (5): 739–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2016.1181059.

- Patrucco, A. S., D. Luzzini, and S. Ronchi. 2017b. “Research Perspectives on Public Procurement: Content Analysis of 14 Years of Publications in the Journal of Public Procurement.” Journal of Public Procurement 17 (2): 229–269. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-17-02-2017-B003.

- Patrucco, A. S., D. Luzzini, S. Ronchi, M. Essig, M. Amann, and A. H. Glas. 2017a. “Designing a Public Procurement Strategy: Lessons from Local Governments.” Public Money & Management 37 (4): 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2017.1295727.

- Patrucco, A. S., H. Walker, D. Luzzini, and S. Ronchi. 2019. “Which Shape Fits Best? Designing the Organizational Form of Local Government Procurement.” Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 25 (3): 100504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2018.06.003.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

- Plantinga, H., H. Voordijk, and A. Dorée. 2020. “Clarifying strategic alignment in the public procurement process.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 33 (6/7): 791–807. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-10-2019-0245.

- Preuss, L. 2009. “Addressing Sustainable Development Through Public Procurement: The Case of Local Government.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 14 (3): 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540910954557.

- Quélin, B. V., I. Kivleniece, and S. Lazzarini. 2017. “Public‐Private Collaboration, Hybridity and Social Value: Towards New Theoretical Perspectives.” Journal of Management Studies 54 (6): 763–792. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12274.

- Reed, S., A. Göpfert, S. Wood, D. Allwood, and W. Warburton. 2019. Building Healthier Communities: The Role of the NHS as an Anchor Institution. London: The Health Foundation.

- Selviaridis, K. 2016. “Public Procurement and Innovation: A Review of Evidence on the Alignment Between Policy and Practice.” Proceedings of the 25th IPSERA Annual Conference, 20-23 March 2016, Dortmund, Germany.

- Selviaridis, K. 2021. “Effects of Public Procurement of R&D on the Innovation Process: Evidence from the UK Small Business Research Initiative.” Journal of Public Procurement 21 (3): 229–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-12-2019-0082.

- Selviaridis, K., and M. Spring. 2022. “Fostering SME Supplier-Enabled Innovation in the Supply Chain: The Role of Innovation Policy.” The Journal of Supply Chain Management 58 (1): 92–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12274.

- Snider, J. S., S. Reysen, and I. Katzarska-Miller. 2013. “How We Frame the Message of Globalization Matters: Globalization Message Framing.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43 (8): 1599–1607. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12111.

- Spina, G., F. Caniato, D. Luzzini, and S. Ronchi. 2013. “Past, Present and Future Trends of Purchasing and Supply Management: An Extensive Literature Review.” Industrial Marketing Management 42 (8): 1202–1212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.04.001.

- Steinfeld, J. M. 2022. “Leadership and Stewardship in Public Procurement: Roles and Responsibilities, Skills and Abilities.” Journal of Public Procurement 22 (3): 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-04-2021-0024.

- Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage.

- Taponen, S., S. Hinrichs-Krapels, and K. Kauppi. 2022. “How Do purchasers’ Control Mechanisms Affect Healthcare Outcomes? Cancer Care Services in the English National Health Service.” Cancer Care Services in the English National Health Service Public Money & Management 42 (8): 658–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2021.1874738.

- Taylor, H., and G. Luter. 2013. Anchor Institutions: An Interpretive Review Essay. USA: Anchor Institutions Task Force 2013, University of Buffalo.

- Troje, D., and T. Andersson. 2020. “As Above, Not so Below: Developing Social Procurement Practices on Strategic and Operative Levels.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 40 (3): 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-03-2020-0054.

- UK Government. 2012. “The Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012.” Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/3/enacted.

- Uyarra, E., B. Ribeiro, and L. Dale-Clough. 2019. “Exploring the Normative Turn in Regional Innovation Policy: Responsibility and the Quest for Public Value.” European Planning Studies 27 (12): 2359–2375. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1609425.

- Vluggen, R., R. Kuijpers, J. Semeijn, and C. J. Gelderman. 2020. “Social Return on Investment in the Public Sector.” Journal of Public Procurement 20 (3): 235–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-06-2018-0023.

- Walker, R. M. 2013. “Strategic Management and Performance in Public Organizations: Findings from the Miles and Snow Framework.” Public Administration Review 73 (5): 675–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12073.

- Wontner, K. L., H. Walker, I. Harris, and J. Lynch. 2020. “Maximising “Community Benefits” in Public Procurement: Tensions and Trade-Offs.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 40 (12): 1909–1939. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-05-2019-0395.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.