ABSTRACT

Grounded in social information processing and social exchange theories, this study explores the effect of team power distance orientation on the indirect relationship between ethical leadership and affective commitment through workplace bullying. Based on a sample of 289 public servants nested in 59 teams in Vietnam, the affective commitment of public servants is positively related to ethical leadership while having a negative association with workplace bullying. We found evidence for the moderation effect of high team power-distance orientation. The findings highlight the importance of contextual values in understanding how ethical leadership mitigates the adverse impacts of workplace bullying.

Workplace bullying is a severe form of workplace mistreatment that impairs the health and well-being of employees (Boudrias, Trépanier, and Salin Citation2021; Nielsen and Einarsen Citation2012). It involves repeated and frequent exposure to negative work-related and person-related behaviours, such as continuous criticism of one’s work and effort, isolation or exclusion, or a target of hostile reaction or practical jokes (Nixon, Arvan, and Spector Citation2021; Notelaers et al. Citation2019). Unlike single episodes of workplace harassment or workplace conflicts, or aggressive behaviours such as incivility or social undermining that occur infrequently and occasionally at low intensity (Boudrias, Trépanier, and Salin Citation2021), workplace bullying exemplifies persistent and prolonged exposure to systematically hostile and abusive behaviours from the perpetrator, enabled by power imbalance where the target experiences difficulties defending themselves (Nielsen and Einarsen Citation2018).

There is mounting evidence of bullying in the public sector in the West (e.g. Ervasti et al. Citation2023; Öztürk and Aşcıgil Citation2017; Plimmer et al. Citation2022; Venetoklis and Kettunen Citation2016). However, research on how public sector organisations can mitigate negative workplace behaviours remains inadequate (Hassan Citation2019; Smith, Halligan, and Mir Citation2021). Though the first decades of studies concentrated on Western countries, researchers now recognize it as a prominent psychosocial hazard in the East, wherein growing evidence presents a clear need to address workplace bullying in Southeast Asian economies (D’Cruz, Noronha, and Mendonca Citation2021). We take an opportunity to enrich the stream of workplace bullying literature by examining workplace bullying in the public sector in Vietnam, where more than half of public sector participants report high levels of bullying exposure (relative to the rate in Western economies; Nguyen et al. Citation2017).

Leaders within organisations are responsible for preventing or mitigating the unhealthy and hostile work environments that fertilize bullying behaviours (Boudrias, Trépanier, and Salin Citation2021; McAllister and Perrewé Citation2018; Nielsen and Einarsen Citation2018). Recent studies that have begun to consider the multilayered processes involved highlight the critical role of ethical leadership (EL) in reducing bullying prevalence, in part through cultivating a work environment in which this form of ethically unacceptable behaviour cannot thrive (Bedi, Alpaslan, and Green Citation2016; Cao et al. Citation2022; Harvey et al. Citation2009; Valentine, Fleischman, and Godkin Citation2018). There is some evidence for significant main effects linking EL to workplace bullying in several workplace contexts (Ahmad Citation2018; Ahmad, Sohal, and Cox Citation2020; Freire and Pinto Citation2022; Stouten et al. Citation2010). However, these studies so far overlooked moderating mechanisms that explain when the impact of EL on negative work behaviours is likely to be stronger or weaker. Scholars (Ahmad Citation2018; Ahmad, Sohal, and Cox Citation2020) suggested more research on the potential moderating effects of cultural orientations on the EL-workplace bullying-outcome linkage because a handful of studies underscored particularly the role of cultural orientations in influencing employee reactions and responses to workplace bullying (Jacobson, Hood, and Van Buren Citation2014; Loh, Restubog, and Zagenczyk Citation2010; Power et al. Citation2013; Salin Citation2021). Indeed, meta-analytic evidence shows that follower reactions and responses to leadership regarding workplace mistreatment are utterly conditional by cultural orientations (Cao et al. Citation2022). Creating new knowledge of the effects of EL on workplace bullying shaped by cultural orientations can inform effective bullying prevention within Southeast Asia through evidence-based leadership. In line with our goal to study bullying in the Southeast Asian context, we introduce a relevant moderating variable: power distance orientation to add value to the under-researched stream of workplace bullying research.

Power distance orientation shapes understandings of social distance, dependence on others, and accepted behaviours within social relationships (Kirkman et al. Citation2009). Historically, Hofstede (Citation1980) defined power distance orientation at the societal level. Empirical studies have also conceptualized, operationalized, and analysed power distance orientation at the individual and group levels of analysis (Peltokorpi and Ramaswami Citation2021; Peng et al. Citation2021) to understand the buffering role of power distance orientation in varying the impacts of leadership on the behaviours of followers (Cao et al. Citation2022). Previous research results about the moderating role of power distance orientation in the relationship between EL, employee behaviours, and work outcomes remain conflicting. For example, Peng and Kim (Citation2020) found that high power distance orientation strengthens the negative influence of EL on counterproductive behaviours as employees highly tolerate power disparities and follow authority to act appropriately. Li et al. (Citation2021) did not find the significant moderation effect of power distance orientation on the relationship between EL and employee engagement. These inconclusive findings support our reasoning for examining power distance orientation as the possible boundary conditions of the associations between EL, workplace bullying, and outcomes.

Within the workplace bullying literature, scholars (Jacobson, Hood, and Van Buren Citation2014; Salin Citation2021; Samnani and Singh Citation2016) urged to examine the potential influences of power distance orientation in reinforcing or weakening the impacts of organisational factors, such as leadership, on employee behaviours, perceptions, and responses to bullying. Despite limited evidence for the connection between workplace bullying and power distance orientation (Loh, Restubog, and Zagenczyk Citation2010; Power et al. Citation2013), the literature on the moderating effects of power distance orientation on the workplace bullying process remains scarce (Jacobson, Hood, and Van Buren Citation2014; Salin Citation2021; Samnani Citation2013). We contribute to this literature paucity by exploring power distance orientation as a potential boundary condition of the outcomes of EL and workplace bullying because imbalanced power distribution is one of the fundamental enablers and boosters of workplace bullying (Jacobson, Hood, and Van Buren Citation2014; Salin Citation2021; Samnani Citation2013). Power distance orientation is high in Southeast Asian countries with respect to workplace bullying, compared to Western economies (D’Cruz, Noronha, and Mendonca Citation2021; Hewett et al. Citation2018; Jacobson, Hood, and Van Buren Citation2014; Loh, Restubog, and Zagenczyk Citation2010). We address the recommendations of scholars in studying the buffering role of power distance orientation in the associations between EL, workplace bullying, and outcomes within the Vietnamese public sector, typically characterized by high power distance and the prevalence of workplace bullying (Nguyen et al. Citation2017; Quang and Vuong Citation2002; Thang et al. Citation2007).

We selected affective commitment as the outcome variable in this study to enhance the resonance of our findings in the public sector context. Affective commitment reflects the emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organisation (Allen and Meyer Citation1990; Hodgkinson et al. Citation2018). Previous research (see Boyne Citation2002; Hodgkinson et al. Citation2018) has noted public sector employees tend to report weaker organisational commitment than their counterparts in private sector organisations. The literature on public administration portrays that affective commitment is a powerful and consistent predictor of public service delivery, work motivation, and innovative work behaviours of public servants (Brimhall Citation2021; Hansen and Kjeldsen Citation2018; Jung and Ritz Citation2014; Nyhan Citation1999; Park and Rainey Citation2007) because it secures employee loyalty and foster job performance (Mercurio Citation2015) and employee engagement in various tasks and activities that contribute to the organisation (Bos‐Nehles, Conway, and Fox Citation2021).

Conceptually, our study is informed by integrating social information processing (SIP) theory with a lens of social exchange principles. SIP theory posits that the attitudes and behaviours of individuals in a particular context are formed and adapted as a result of processing prominent context-related social information together with social cues learned and acquired through social interactions (Salancik and Pfeffer Citation1978). Under the tenets of SIP theory, we conceptualize and operationalize power distance orientation at the team level and argue that team power distance orientation is a prominent cue that intensifies the associations between EL and workplace bullying. The literature posits that reciprocal norms of social and relational work contexts govern the consequences of EL and workplace bullying (Ahmad Citation2018; Naseer et al. Citation2018; Parzefall and Salin Citation2010), as depicted by social exchange theory (SET). Employees reciprocate a positive work environment and high-quality interpersonal relationships through promising and positive attitudes and behaviours (Cropanzano et al. Citation2017). Employees are more likely to return high disengagement, low dissatisfaction, and increased intentions to quit towards unfair and aggressive treatment at work (Ahmad Citation2018; Naseer et al. Citation2018; Parzefall and Salin Citation2010). As SET is one of the most meaningful theoretical frameworks for understanding workplace behaviours (Cropanzano et al. Citation2017), it is pertinent to explain the mechanisms through which how EL and workplace bullying influence affective commitment in this study.

Our study contributes to the literature on workplace bullying in the Southeast Asian cultural context by seeking to shine new light on how public sector organisations can mitigate workplace bullying by systematically embedding EL behaviours and cultural orientations at the team level into complementary anti-bullying strategies. Research has explored factors at different organisational levels as predictors of bullying, such as organisational climate, leadership, and work design (Dollard et al. Citation2017; Tuckey et al. Citation2022) in separate streams of the literature. Integrating organisational factors at different levels allows us to explore whether or not and how team power distance orientation acts as a primary boundary for the effectiveness of anti-bullying strategies within public sector organisations. This study broadens the scholarship on the boundary conditions of EL and workplace bullying because cultural orientations make it challenging to generalize research results from Western contexts to countries like Vietnam.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Employees attend to social cues from the nature of working conditions and interpersonal relationships to make sense of the work environment and develop socially plausible and legitimate attitudes and behaviours congruent with the organisational norms and expectations (Salancik and Pfeffer Citation1978). Social information from words or actions of interrelations and interactions with supervisors and co-workers shape attitudes and behaviours of individuals through their interpretation of the organisation based on saliency (i.e. immediately being aware of social norms) and relevance (i.e. understanding accepted attitudes and behaviours) (Salancik and Pfeffer Citation1978). Supervisors are primary social informants and salient figures representing the organisation as their leadership behaviours transmit expected attitudes and behaviours endorsed by the organisation (Fehr, Fulmer, and Keng‐Highberger Citation2020; Jiang and Gu Citation2016; Lu, Zhang, and Jia Citation2019). Employees use social information on leadership behaviours to interpret work events, jobs, or interpersonal relationships and navigate their appropriate attitudes and behaviours. SIP theory is relevant to explain the influence of EL on workplace bullying as supervisors have a social impact facilitated by their hierarchical power and status to provide social cues and distribute rewards or punishments to form employee perceptions of respect, fairness, credibility, and integrity (Koopman et al. Citation2019; Mayer, Kuenzi, and Greenbaum Citation2010). Employees mirror and emulate the behaviours of ethical supervisors to act consistently with the expected norms for interpersonal relationships at work (Ahmad Citation2018; Koopman et al. Citation2019; Walsh et al. Citation2018).

While SIP theory highlights the critical role of leadership behaviours in constructing social cues to shape employee attitudes and behaviours, SET principles emphasise employee reciprocity towards the treatment given by supervisors and the organisation (Cropanzano et al. Citation2017). Much knowledge posits that employees reciprocate positive attitudes and behaviours towards the respectful, fair, and trustworthy treatment of EL (Bedi, Alpaslan, and Green Citation2016; Hoch et al. Citation2018). Public management literature shows the promising benefits of ethical leaders in increasing affective commitment and willingness to report unethical behaviours among public servants to return to the fair treatment of ethical leaders (Hassan, Wright, and Yukl Citation2014; Moon and Christensen Citation2022; Thaler and Helmig Citation2016). Evidence of the outcomes of EL and negative work behaviours underpinned by SET remains lacking in the public management literature (Young, Hassan, and Hatmaker Citation2021). As EL fosters role models of highly moral behaviours, the interaction with ethical leaders reinforces a sense of obligation to produce affective commitment as a reciprocal form of favourable work outcomes (Mayer et al. Citation2012; Moon and Christensen Citation2022). On the other hand, we base on SET to argue that workplace bullying as an unfavourable and disrespectful treatment reduces the motivation to develop an emotional attachment to the organisation as the organisation does not uphold fairness and integrity (Bulutlar and Öz Citation2009; López-Cabarcos, Vázquez-Rodríguez, and Piñeiro-Chousa Citation2016; McCormack et al. Citation2009).

Although employees can follow behaviours of ethical supervisors, the influence of leadership behaviours on employees in responding to interpersonal relationships and interactions at work is never context-free (Jacobson, Hood, and Van Buren Citation2014). SIP tenets highlight that the attitudes and behaviours of individuals are shaped and influenced by the salient overarching norms and beliefs within the broader sociocultural context, which can shape the cultural orientations of individuals (Gelfand, Erez, and Aycan Citation2007; Zajenkowska et al. Citation2021). These cultural orientations also inform employee attitudes, behaviours, and reactions towards social interactions and events in the workplace (Gelfand, Erez, and Aycan Citation2007; Kirkman et al. Citation2009). Employees are also likely to use cultural orientations towards power and authority (Kirkman et al. Citation2009; Yang, Mossholder, and Peng Citation2007) to evaluate, determine, and react to leadership behaviours and workplace circumstances (Gelfand, Erez, and Aycan Citation2007; Hu et al. Citation2018). Research applying SET addresses that cultural orientations attenuate or exacerbate the impacts of workplace interactions on employee outcomes (Farh, Hackett, and Liang Citation2007; Lin, Wang, and Chen Citation2013; Liu, Yang, and Nauta Citation2013). As affective commitment is motivated by employee reciprocity towards workplace treatment benefits (Cropanzano et al. Citation2017), we contend that cultural orientations are contingent factors underpinning employee reciprocal attitudes and behaviours towards workplace treatment (Cao et al. Citation2022).

Power distance is one of the crucial cultural orientations underpinning employee responses and reactions to leadership behaviours and workplace interactions (Kirkman et al. Citation2009; Peng et al. Citation2021; Song et al. Citation2019). Empirical studies (Hu et al. Citation2018; Lin, Wang, and Chen Citation2013; Loi, Lam, and Chan Citation2012; Peltokorpi and Ramaswami Citation2021) provided evidence that power distance orientation amplifies the influences of leadership behaviours on employee attitudes and behaviours. Despite the growth of research on the moderation role of power distance orientation within leader–employee relationships, we have limited knowledge of how power distance orientation influences employee interpretation of EL behaviours and reactions to workplace bullying (except Loh, Restubog, and Zagenczyk Citation2010; Samnani Citation2013). Grounded in the tenets of SIP theory, we test whether team power distance orientation intensifies the negative influence of EL on workplace bullying as high power distance orientation at the team level encourages employees to attend a collective understanding of respect and compliance with normative behaviours endorsed and facilitated by ethical supervisors. Based on SET principles, we expect that team power distance orientation could strengthen the unfavourable reciprocation of employees to the organisation when workplace bullying generates employee perceptions of an unsafe and unhealthy psychosocial environment. demonstrates the proposed model in this study.

Ethical leadership, workplace bullying, and affective commitment

Although EL could create healthy and normative interpersonal relationships (Bedi, Alpaslan, and Green Citation2016; Hoch et al. Citation2018), relatively few empirical studies have examined its impacts on the attitudes and behaviours of public servants (Hassan, Wright, and Yukl Citation2014; Thaler and Helmig Citation2016; Young, Hassan, and Hatmaker Citation2021). Drawing on SIP theory, we argue that EL plays a role in minimizing bullying at work by providing powerful social cues, signalling that unethical conduct, such as bullying, does not belong, through two perspectives: that of a moral person and a moral manager (Harvey et al. Citation2009; Stouten et al. Citation2010; Valentine, Fleischman, and Godkin Citation2018). First, a supervisor is ethical (i.e. a moral person) when s/he possesses and shows traits and behaviours of integrity, justice, and fairness in their words and actions. Second, an ethical supervisor is a (moral) manager who consistently communicates about and rewards ethical conduct in others and disciplines unethical behaviours at all levels of the organisation. Both perspectives make it likely that EL enhances the moral awareness of followers and creates fertile soil for employees to engage in and comply with the ethical standards of an organisation (Brown, Treviño, and Harrison Citation2005; Treviño Citation2018; Young, Hassan, and Hatmaker Citation2021). Other studies (Cao et al. Citation2022; Stouten et al. Citation2010; van Gils et al. Citation2015) show that EL informs employees about the rewards for respectful interrelationships and the engagement in appropriate conduct, and punishments for normative violations or inappropriate behaviours. We anticipate that EL can minimize the likelihood of workplace bullying exposure by increasing the understanding that workplace bullying is unacceptable as it breaches moral standards for interpersonal relationships endorsed by EL. More importantly, ethical supervisors encourage employees to address workplace bullying timely and provide further social information about the consequences of instigating workplace bullying (Stouten et al. Citation2010; van Gils et al. Citation2015). Consistent with this rationale, empirical findings (Ahmad Citation2018; Cao et al. Citation2022; Freire and Pinto Citation2022) have shown that EL discourages workplace bullying and other aggressive behaviours. We argue that the words and actions of EL are crucial catalysts in navigating employee familiarity with performing fair and respectful behaviours in workplace relationships. Therefore, EL can reduce workplace bullying by developing an understanding of what is valued and supported:

Hypothesis 1:

Ethical leadership is negatively related to workplace bullying.

Affective commitment is affected by the quality of interpersonal relationships within organisations (Su, Baird, and Blair Citation2013), suggesting that it should be sensitive to workplace bullying (Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen Citation2020). Bullying at work is a threat stressor associated with a sense of direct harm or loss (cf. Tuckey et al. Citation2015) and undermines basic psychological needs (Boudrias, Trépanier, and Salin Citation2021). Extending the principles of SIP theory to the consequences of bullying, we expect that employees would interpret social information from workplace bullying incidents as an indicator that the environment is unsafe, stressful, and hostile (Plimmer et al. Citation2022). In turn, working in an unhealthy environment erodes the extent to which employees can remain personally and emotionally invested, along with the willingness to stay and contribute to the organisation (Salin Citation2021; Su, Baird, and Blair Citation2013). Employees could perceive workplace bullying as a lack of organisational care and protection for employee well-being, thereby reducing their emotional attachment to the organisation (Teo, Bentley, and Nguyen Citation2020). Based on the SET perspective, employees tend to reciprocate positive outcomes towards supportive and fair treatment from the organisation (Cropanzano et al. Citation2017). In this instance, employees rationalize workplace bullying as an unjust treatment that violates the norms for a high-quality exchange relationship between employees and the organisation. Workplace bullying contributes to the emotional detachment from the organisation as workplace bullying signals insecure, poor, and aggressive social interactions at work (Bulutlar and Öz Citation2009; Glasø and Notelaers Citation2012; López-Cabarcos, Vázquez-Rodríguez, and Piñeiro-Chousa Citation2016; McCormack et al. Citation2009).

In addition, we argue for the potential flow-on effect of EL on affective commitment through workplace bullying. EL is crucial to reducing the likelihood of workplace bullying by upholding normative standards and punishments for employee inappropriate behaviours. Ethical supervisors also consider fairness and justice by minimizing job-related stressors, such as unreasonable job demands and unfavourable work conditions, that could fertilize workplace bullying (Nielsen and Einarsen Citation2018; Stouten et al. Citation2010; Valentine, Fleischman, and Godkin Citation2018). EL can maintain the harmonious stability of an ethical, caring, and safe work environment, which makes employees generate a mindset of staying with the organisation (Brown and Mitchell Citation2010; Harvey et al. Citation2009; Stouten et al. Citation2010). Based on the norms of social exchange, moral values and principles set by EL increase affective commitment amongst subordinates as they feel respected, listened to, and involved in decision-making (Bedi, Alpaslan, and Green Citation2016; Brown, Treviño, and Harrison Citation2005).

Hypothesis 2:

Ethical leadership is indirectly related to affective commitment through the mediating role of workplace bullying.

Team power distance orientation

Hofstede (Citation1980, 45) defined power distance orientation as ‘the extent to which a society accepts the fact that power in institutions and organisations is distributed unequally’. Although this concept was originally introduced at the societal level, several studies (Hu et al. Citation2018; Peng et al. Citation2021; Song et al. Citation2019) have explored and analysed power distance orientation at individual and group levels in an organisational context to uncover the boundary conditions of social phenomena at work. Accordingly, high power distance orientation refers to the acceptance of the legitimacy of the imbalanced power distribution within an organisation (Farh, Hackett, and Liang Citation2007; Kirkman et al. Citation2009). Employees with high power distance orientation are likely to endorse power differences and status privileges inherent within an organisation, arising from its hierarchical structure (Farh, Hackett, and Liang Citation2007; Lin, Wang, and Chen Citation2013; Peltokorpi and Ramaswami Citation2021). In this instance, the negative impact of EL on unethical behaviours is likely to be strengthened as employees respect their authority and social status of ethical supervisors who have more attractive role models for ethical conduct (Cao et al. Citation2022; Peng and Kim Citation2020).

SIP theory highlights that social cues arising from team interactions characterize acceptable and principal behaviours for the whole team, providing a strong context to shape individual attitudes and behaviours (Ali, Wang, and Boekhorst Citation2023; Salancik and Pfeffer Citation1978; Yang, Mossholder, and Peng Citation2007). Applied to this study, when a team has a shared high power distance orientation, members will share the sensitivity to the hierarchical level of their supervisor (Hu et al. Citation2018). High team power distance orientation should strengthen the beliefs and acceptance of power, authority, and status of the leader. In this situation, team members will share an understanding that following ethical behaviours endorsed by ethical supervisor is expected and regulated. Therefore, ethical supervisors can promote norm obedience and constrain variations of employee attitudes and behaviours in high power distance contexts (Peng and Kim Citation2020). By attenuating or overriding individual differences, the neutralizing effects of power distance orientation on the relationship between EL and bullying beyond effects may be particularly evident at the team level.

Hypothesis 3:

High team power distance orientation will strengthen the negative relationship between EL and workplace bullying.

Employees develop the emotional bond with the organisation when they receive a high-quality reciprocal relationship with the organisation and a positive treatment (Cropanzano et al. Citation2017). Employees can interpret workplace bullying as a form of workplace mistreatment that discourages the development of emotional ties to the organisation (Parzefall and Salin Citation2010). Team power distance orientation could intensify the negative relationship between workplace bullying and affective commitment due to the shared perception of authority deference that minimizes employees’ willingness to speak up about workplace bullying. Within such a low-quality relationship, team power distance orientation could reinforce the distance between employees and the organisation as employees see the superior management of the organisation as unapproachable and autocratic (Farh, Hackett, and Liang Citation2007). They hence hesitate to express ethical concerns or seek advice (Daniels and Greguras Citation2014; Loi, Lam, and Chan Citation2012). Employees may get the sense that the ability to gain attention from superior managers to offer personal opinions is relatively minimal due to power disparities (Peltokorpi and Ramaswami Citation2021). Although team power distance orientation can foster a shared understanding that workplace bullying may be a legitimate and regular practice within the organisation that they need to obey (D’Cruz, Noronha, and Mendonca Citation2021; Samnani Citation2013), workplace bullying creates a stressful and unhealthy environment. Employees in such situations may be inclined to a sense of lacking respect, dignity, and belongingness to the organisation.

Hypothesis 4:

High team power distance orientation will strengthen the negative relationship between workplace bullying and affective commitment.

Methodology

Research context

Leadership behaviours and work-related experiences are seen as sensitive topics in the Vietnamese public sector, raising the suspicion of public sector managers about this type of research (Bartram, Stanton, and Thomas Citation2009; Quang and Vuong Citation2002). Therefore, prior to distributing the questionnaire, we obtained the approval of a provincial government that allowed the research team to collect the data from their employees without any consequences. Regarding ethics requirements, we provided potential respondents with a supporting letter from the director and the participant information letter to help them understand their voluntary and confidential participation in this project. These primary steps of the data collection process were used to encourage honest and thoughtful responses and prevent the potential for social desirability bias and other types of response errors (see Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff Citation2012).

Demographic information

We recruited a sample of 500 public servants working in local agencies in a province of Vietnam. The final sample consisted of 289 public servants from 59 teams who agreed to answer and completed the questionnaire. This sample size had good power and effect size to yield the flexibility and accuracy of the four-predictor model (Cohen Citation1988). In our study, half of the respondents identified as male (51.80%). More than three quarters (80.10%) indicated their age ranging from 26 to 40 years old, while 17.80% aged from 41–60 years old. Of the respondents, a quarter (25.30%) were from small-size agencies (less than 20 employees), and 43.90% reported working in agencies with approximately 20–49 employees. Additionally, the majority (82.20%) had at least three years of experience in their jobs. Likewise, 85.70% had at least three years of experience working in their current agencies. Furthermore, more than half of the respondents (65.6%) reported being married. Finally, 86.30% had at least undergraduate degrees.

Measures

We followed the back-translation approach (Brislin Citation1970) to ensure the content and face validity of the instruments in Vietnamese. Specifically, three authors who have bilingual abilities undertook the translation for the survey from English to Vietnamese and back to English. We then compared and corrected interpretation errors. We further carried out a pre-test of the translated survey with 50 part-time postgraduate business and commerce students to ensure the face and content validity of the study constructs.

Power distance orientation

This was measured at individual level using a six-item scale from Dorfman and Howell (Citation1988) that was adopted by Farh et al. (Citation2007), and Zhong et al. (Citation2016) on a seven-point Likert scale anchored by ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ (α=.86). Sample items included ‘Managers avoid off-the-job social contacts with employees’. The individual ratings on power distance orientation were aggregated to team-level. To support the aggregation of power distance orientation construct at the team level, we examined three conventional aggregation statistics. The first one is the interrater agreement indicator which is rwg (James, Demaree, and Wolf Citation1984, Citation1993). Two other interrater reliability indicators include an interclass correlation – ICC(1) (i.e. an intraclass correlation that signifies the percentage of variance accounted by between-group differences) and ICC(2) (i.e. the reliability of the group mean; Bliese Citation2000; Kozlowski and Klein Citation2000). To calculate rwg, we used a standardized null distribution. The mean rwg was .88. The values of ICC(1) and ICC(2) were .49 and .82, respectively. Accordingly, the ICC(1) value was higher than the cut-off median value of .12 and the ICC(2) value was higher than the cut-off median value of .70 (James Citation1982). In general, the values of rwg, ICC(1), and ICC(2) in this study were acceptable and comparable with the median or the cut-off values of ICC statistics reported in the literature (George and Bettenhausen Citation1990; Schneider, White, and Paul Citation1998), indicating that the aggregation of power distance orientation was supported. The Cronbach’s alpha of this team-level construct was .94.

Ethical leadership

We used a 10-item scale from Brown et al. (Citation2005) to measure employee perceptions of EL behaviours of their direct supervisors on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly agree’ (α=.90). Sample items included ‘my supervisor conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner’.

Workplace bullying

To measure the frequency of employees’ exposure to workplace bullying, we used a short form of NAQ scale developed by Notelaers, Van der Heijden, Hoel, and Einarsen (Citation2019) on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘daily’ (α=.94). Sample items included ‘Spreading gossip and rumors about you’.

Affective commitment

We adopted a seven-item scale from Allen and Meyer (Citation1990) to measure employees’ affective commitment on a seven-point Likert scale anchored by ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ (α=.90). Samples of items included ‘I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organisation’.

Control variables

We controlled for gender, age, education level, and job tenure that have associations with ethical leadership (Hassan, Wright, and Yukl Citation2014) and workplace bullying in the literature (Hoel et al. Citation2010; Zapf et al. Citation2011).

Data analysis

Measurement model estimation

Using IBM AMOS ver25, we undertook nested model difference tests between the preferred model in each study with other alternative models to validate the discriminant validity of all the latent constructs at the individual level. The comparison of Chi-square different tests reveals that the hypothesized four-factor model had the best fit to the data (χ2 [271] = 461.70, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .049, SRMR = .04), compared to the 3-factor model (χ2 [274] = 924.81, CFI = .88, TLI = .86, RMSEA = .091, SRMR = .102), the 2-factor model (χ2 [276] = 1378.39, CFI = .80, TLI = .76, RMSEA = .118, SRMR = .170), and the single-factor model (χ2 [277] = 1960.12, CFI = .69, TLI = .64, RMSEA = .145, SRMR = .209). reports CR, AVE, and MSV values that indicated convergent and discriminant validity of constructs as their AVE values, the square root of AVE, and the values of MSV met the thresholds (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981; Hair et al. Citation2010).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables.

Analytical procedure

Similar approaches to detect the potential of CMV were applied in this study. First, the Harman’s single-factor analysis using an unrotated solution produced one single factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1 accounting for 27.56% of the variance in the exogenous and endogenous constructs, which is below the 50% threshold. shows that the CFA of the preferred model had a good fit to the data, compared to other models. Finally, the significant mediation and moderation effects minimized the potential of CMV in the data (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff Citation2012). These tests indicated that CMV was not a problem.

Table 2. Hierarchical linear modelling results.

We employed Hierarchical Linear Modelling (HLM, Raudenbush and Bryk Citation2002) to test the hypotheses because this technique can account for the data aggregation while testing a cross-level moderation effect and accounting for the different sources of variance (Hofmann, Griffin, and Gavin Citation2000). We first assessed whether EL, workplace bullying, and affective commitment varied between teams by running null hypothesized models (no individual- or team-level antecedents) as indicated by ICC(1). Accordingly, ICC(1) for EL was .10 (λ2[58] = 90.41, p < .01), indicating that 10% of its total variance remained between teams. The result of ICC(1) for workplace bullying was .33 (λ2[58] = 199.32, p < .001), showing that 33% of its variance resided between teams. Finally, 12% of the variance of affective commitment resided between teams as indicated by the ICC(1) value of .12 (λ2[58] = 95.22, p < .01). These results showed that there was significant team-level variance in ethical leadership, workplace bullying, and affective commitment. This conclusion indicated that the aggregation of team power distance orientation is meaningful to explain the team-level variance in these individual-level constructs (Bliese Citation2002; Snijders and Bosker Citation1999). Therefore, the utilization of HLM is appropriate in this study.

reports the results of HLM analyses. We followed Snijders and Bosker (Citation1999, 102–103) to calculate the R2 values as an indicator of variance explained by a specific set of variables in different levels. Additionally, we followed Bauer et al. (Citation2006) to employ a simple bootstrapping method to test the mediating effect of workplace bullying as this approach can generate bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) for the standard errors. Additionally, this bootstrapping approach does not require a normal distribution for the standard errors of the indirect relationship (Bauer, Preacher, and Gil Citation2006).

Results

reports the means, standard deviance, CR, AVE, MSV, and the correlations between control variables and latent constructs. As shown, the respondents in our study reported a fairly low level of workplace bullying (Mean = 1.47, SD = .76). Additionally, the respondents reported exposing to four significant bullying behaviours regularly (i.e. ‘now and then’ and ‘monthly’). Specifically, of the respondents, 65% reported exposing to ‘evaluating of your work and efforts’ (Mean = 1.90, SD = .96). Furthermore, 60% of respondents experienced ‘gossip or rumors about you’ (Mean = 1.85, SD = .93). Approximately 52% indicated to be victims of the behaviour of ‘repeated reminders about your blunders or mistakes’ (Mean = 1.77, SD = .97). Finally, half of the respondents reported experiencing ‘silence or hostility as a response to your questions or attempts at conversations’ (Mean = 1.76, SD = .95).

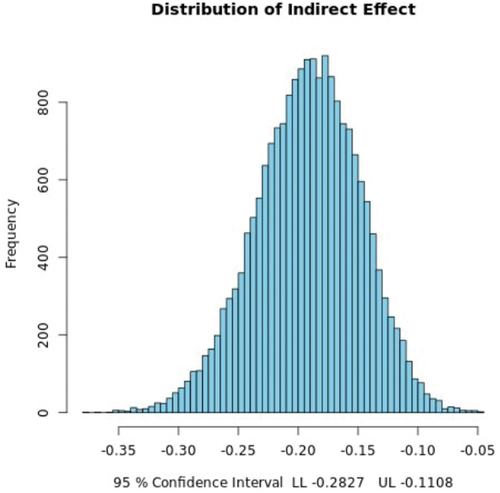

shows the negative and statistically significant relationship between EL and workplace bullying (γ=-.16, p < .05). This finding supports Hypothesis 1. Additionally, the association between workplace bullying and affective commitment was significantly negative (γ=-.26, p < .001). Furthermore, we found a significant and positive relationship between EL and affective commitment (γ=.74, p < .001). The main effect of EL on affective commitment remained significant when workplace bullying was entered as a mediator. A 95% CI[−.111, −.283] based on 20,000 bootstrap samples that did not include zero (Bauer, Preacher, and Gil Citation2006) showed that the main effect of ethical leadership on affective commitment remained significant when workplace bullying was entered as a mediator, supporting Hypothesis 2 (see ).

Figure 2. Indirect effect of workplace bullying on the relationship between EL and affective commitment.

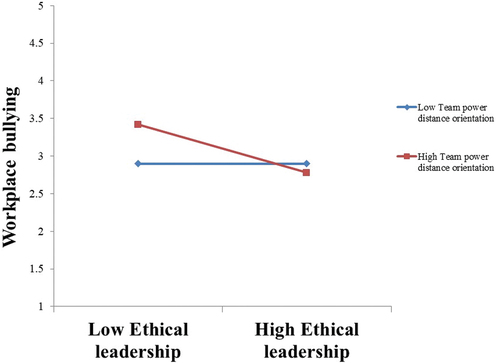

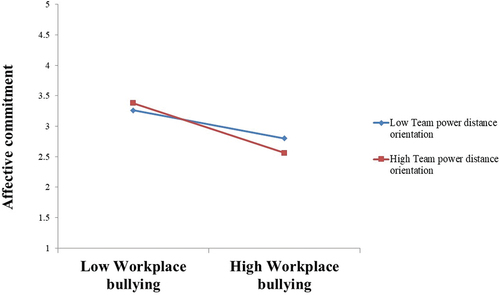

also shows the result of the HLM analysis for testing Hypotheses 3 and 4. We used the ‘slopes-as-outcomes’ model to test these hypotheses where the variance in the slope across teams is expected to be significantly related to power distance orientation. Following scholars (Hofmann and Gavin Citation1998; Hofmann, Morgeson, and Gerras Citation2003), we entered team power distance orientation as a predictor of the variance in the slopes relating to ethical leadership and workplace bullying. Likewise, team power distance orientation was also entered as the predictor of the variance in the slopes with respect to workplace bullying and affective commitment. As shown in , the interaction effect between the team power distance orientation and individual perceptions of EL was negatively related to workplace bullying (effect=−.16, p < .05), explaining 11% of the within-group variance and 6% of the between-group variance. The interaction effect between team power distance orientation and workplace bullying was significantly negative with respect to affective commitment (effect=−.09, p < .05), explaining 20% of the within-group variance and 40% of the between-group variance.

We simply plotted the interaction effects on using one standard deviation above and below the mean of team power distance orientation (Aiken and West Citation1991). In line with Hypothesis 3, depicts that the slope representing the linear relationship between EL and workplace bullying was negatively greater when team power distance orientation increased. Our Hypothesis 4 stated that the negative relationship between workplace bullying and affective commitment would be stronger when team power distance orientation was high. shows the supportive evidence for Hypothesis 4 because the slope representing the linear relationship between workplace bullying and affective commitment was sharper and negative when team power distance was high.

General discussion

Drawing upon the integration of SIP and SET perspectives, we proposed that power distance orientation would provide alternate social signals that strengthen the protective role of EL in preventing workplace bullying, as well as exaggerate the negative relationship between workplace bullying and affective commitment. We conceptualized a framework including the moderating effect of power distance orientation at the team level on the relationships between EL, workplace bullying, and affective commitment. We utilized a sample in the public sector in Vietnam to test the hypotheses. We observed that team power distance orientation enhanced the preventative effects of EL. Said another way, our key finding is that increasing power distance orientation at the team level in public sector organisations intensifies the negative relationship between EL and workplace bullying exposure, with flow-on effects to affective commitment at the individual level. As expected, affective commitment was positively related to EL and workplace bullying partially mediated this effect. Finally, the negative association between workplace bullying and affective commitment was worsened when team power distance orientation was high. Our findings add a significant value to understanding workplace bullying and the organisational implications of preventing this psychosocial hazard.

Theoretical implications

Research on the impact of EL on the negative behaviours of employees in the public management domain is scarce (e.g. Hassan, Wright, and Yukl Citation2014; Young, Hassan, and Hatmaker Citation2021). Reinforcing the findings of earlier studies (Ahmad Citation2018; Ahmad, Sohal, and Cox Citation2020; Freire and Pinto Citation2022; Young, Hassan, and Hatmaker Citation2021), our research provides evidence that EL plays a leading and predominant role in discouraging workplace bullying to increase positive organisational outcomes. Through the lens of SIP theory, this finding echoes the consistent conclusion that EL is a unique and powerful precursor for bullying at work (Ahmad Citation2018; Ahmad, Sohal, and Cox Citation2020; Cao et al. Citation2022; Stouten et al. Citation2010). The words and actions of EL signal what to do and how to treat others at work. Indeed, EL attracts employees through role models and provides social information that forms an ethical workplace environment in which employees endorse moral, respectful, and fair social interactions (Fehr, Yam, and Dang Citation2015; van Gils et al. Citation2015). This study supports SET research that EL could enhance affective commitment by minimizing workplace bullying as the outcome of social exchange processing (Brown and Mitchell Citation2010; Harvey et al. Citation2009; Stouten et al. Citation2010). More importantly, the main discovery from our study is that these relationships are more complex than the main effects observed within the existing literature. We underscore how team power distance orientation, EL, and workplace bullying are intertwined.

Under a SIP theory framing, our research shows that even though EL is a salient source of social information for employees to behave appropriately and ethically, other contextual factors can send competing and even overriding signals that exaggerate or attenuate the positive influence of this leadership style in reducing workplace bullying and enhancing affective commitment. We focused on power distance orientation as an alternate source of social cues influencing how employees make sense of leadership behaviours and the workplace environment (Hu et al. Citation2018; Lin, Wang, and Chen Citation2013; Liu, Yang, and Nauta Citation2013). We found that high levels of power distance orientation at the team level bolster the effects of EL. Our findings suggest that EL may not be sufficient to prevent bullying directly in specific environments, where it instead operates in concert with other work environment factors. This study highlights that a team level of power distance orientation deserves to gain more attention within the literature on EL and workplace bullying in both public and general management theories.

While the current review (Matthews, Kelemen, and Bolino Citation2021) concluded inconsistent and mixed impacts of power distance orientation on the relationship between leadership and follower outcomes, our study displays the positive contribution of power distance orientation to leadership influences. Based on SIP theory, individuals seek peer guidance to adjust their attitudes and behaviours to fit the work environment (Salancik and Pfeffer Citation1978). Team members use the social information of team power distance orientation to behave invariably and consistently according to the shared values of a team to show their compliance and conformity (Farh, Hackett, and Liang Citation2007). Looking across our research, it seems that the effects of shared power distance orientation for teams may be even more cohesive and more constructive concerning encouraging EL to be more effective. From this perspective, team power distance orientation is a vital contingency in the relationship between EL and workplace bullying. Specifically, EL could be more likely to mitigate workplace bullying in teams with high power distance orientation as employees see supervisors as the representative of hierarchical status and power in the organisation. This result may suggest that ethical supervisors can amplify and strengthen their formal authority and power in a high-power distance context to carry out their duties in inhibiting workplace bullying as team members collectively rationalize and agree to comply with normative standards established by EL. Although bullying is necessarily legitimate for power and hierarchy disparities in such environments (Kwan, Tuckey, and Dollard Citation2014; Samnani Citation2013), high-power distance-oriented employees are more sensitive to and rely on the decisions and actions made by their supervisors without questioning the decision-making or going against their supervisors. Therefore, it is reasonable and beneficial for ethical supervisors to display a powerful role model of ethical conduct and discipline unethical behaviours (Farh, Hackett, and Liang Citation2007). This finding responses to the call for research on contextual conditions for the impacts of EL on minimizing unethical and aggressive work behaviours (Cao et al. Citation2022; Peng and Kim Citation2020).

Our study is contradictory to another stream of research (Kirkman et al. Citation2009; Newman and Butler Citation2014) that has shown power distance orientation as the weakener on the influences of constructive leadership (e.g. transformational leadership) on employee outcomes (e.g. organisational citizenship behaviour) in a high context of power distance orientation. The literature portrays that positive leadership behaviours, such as transformational leadership, could be incongruent with the expectations of employees who believe leaders are superior, autocratic, and inapproachable (Farh, Hackett, and Liang Citation2007). Displaying caring behaviours or involving employees in decision-making could conflict with the organisational hierarchy and authoritative relationships. As such, team members could collectively believe that approaching a leader socially or expressing concerns about ethical issues results in anti-complementarity in the leader–team relationship. Therefore, employees with high power distance orientation could be less likely to observe, interpret, and learn the normative manner of those supervisors (Loi, Lam, and Chan Citation2012). Also, the tendency to maintain position distinctions between subordinates and a supervisor could attenuate social cues established by EL, and a high power distance orientation could weaken the motivation of employees to voice or speak up about ethical issues (Daniels and Greguras Citation2014). Our findings exemplify that high team power distance amplifies the powerful authority and a role model of moral behaviours of EL that employees would not go against high-status supervisors to avoid punishments for inappropriate behaviours. It is more interesting to consider the competing perspective to investigate bullying as an organisational issue by examining multilevel processes and effects in the future research.

As we expected in Hypothesis 4, team power distance orientation could strengthen the negative association between workplace bullying and affective commitment. This pattern of research findings is inconsistent with the existing literature stating that aggressive work behaviours do not have much impact on employees with a high power distance orientation as they could internalize the social information of high power distance culture to endorse power distances and status privileges inherent in an organisation due to the nature of its hierarchical structure (Farh, Hackett, and Liang Citation2007; Lin, Wang, and Chen Citation2013; Loh, Restubog, and Zagenczyk Citation2010; Peltokorpi and Ramaswami Citation2021). Therefore, it is understandable that the likelihood of experiencing job dissatisfaction is lessened among employees in high power distance contexts when they experience aggressive treatment (Lin, Wang, and Chen Citation2013; Peltokorpi and Ramaswami Citation2021). However, we contend that the conclusion from previous studies that workplace bullying has a minimal impact on employee attitudes and behaviours within a high context of power distance orientation is supported when aggressive and hostile treatment is from supervisors who hold hierarchical authority and power (Hon and Lu Citation2016; Loh, Restubog, and Zagenczyk Citation2010; Peltokorpi and Ramaswami Citation2021; Richard et al. Citation2020). In this study, the instigators of workplace bullying could be supervisors or peers (Nixon, Arvan, and Spector Citation2021; Notelaers et al. Citation2019). Therefore, the crucial aspect of our theory-expansion efforts pertains to integrating SIP and SET theories in providing evidence that team power distance orientation could amplify a shared understanding that workplace bullying is legitimate and inevitable in a high power distance context. Therefore, employees tend to show passive and reactive attitudes and behaviours (such as disengagement in work tasks and low performance, Zhang and Liao Citation2015) in reciprocating unfavourable treatment from others and a low-quality, unhealthy, and stressful relationship with the organisation. Our study draws upon SIP and SET lenses to show that team power distance orientation as a dominant trigger may intensify the feeling of discouragement and disconnection from the organisation when workplace bullying as a stressor fosters uncomfortable cognitive and emotional reactions (Bond et al. Citation1985; Peltokorpi 2019; Welbourne et al. Citation2015). While there remains a lack of evidence about power distance orientation in the public management literature on EL, workplace bullying and outcomes, our findings advance the effects of social information and social exchange in highly power distance-oriented contexts. This study supports the argument that contextual factors (e.g. EL and power distance orientation) are foremost in understanding better workplace bullying and its outcomes (Boudrias, Trépanier, and Salin Citation2021; Neall and Tuckey Citation2014; Nielsen and Einarsen Citation2012, Citation2018).

Finally, our exploration of the social signals provided by leadership behaviours alongside power distance orientation contributes much-needed empirical evidence regarding the role of the cultural context of non-Western societies, such as Vietnam, in bullying at work. Our finding suggests that, in the East, shared cultural orientations and individual acceptance of broader cultural values may offset the effects of leadership behaviours by individual managers within an organisation. In Eastern organisations, cultural values provide dominant cues that powerfully influence levels of mistreatment, including moderating the effects of other work environmental factors. Our study affirms that research on workplace bullying and other negative behaviours in high power distance contexts needs to be more sensitive to cultural dimensions as these factors influence how individuals and teams make sense of negative social behaviours and leadership impacts. There may be some relationships regarding the antecedents and outcomes of bullying that are widely invariant between the East and the West. Yet it is becoming evident that research needs to include cultural factors that provide strong contextual influences to better understand workplace bullying in a specific context (see D’Cruz, Noronha, and Mendonca Citation2021; Salin Citation2021; Samnani Citation2013).

Managerial implications

The findings in our study offer various managerial implications to public sector organisations in Vietnam and beyond. Public sector organisations must pay attention to shared cultural orientations held by employees and cultivate these as primary social signals that shape employee attitudes and behaviours. A range of mechanisms could be introduced to bridge power distance in appropriate ways without undermining formal organisational authority. For example, formal human resource (HR) mechanisms could be introduced to provide anonymous feedback about experiences of mistreatment, or to gather input from staff at all levels regarding psychosocial hazards and how to remedy them. Disciplinary approaches along with formal training in conflict management implemented by HR managers could also be effective and favour in high-power distance contexts. Care must also be taken to minimize the potential for power distance to be misused. Decision authority could be devolved to employees regarding matters within their job scope, and collective inputs into reviewing and how people and tasks are managed offer a concrete focal point for bullying prevention efforts. Finally, as bullying benefits the bullies, while the victims tolerate silence within a high-power distance-oriented context, managers must be responsive to any bullying that does occur to foster the willingness to raise and speak up about ethical concerns (Kwan, Tuckey, and Dollard Citation2016).

Based on our findings, public sector organisations can create a trickle-down effect that involves senior managers, supervisors, and employees in effective bullying prevention. First, organisations could promote EL programmes, strategies, and tactics to increase ethics-related awareness, and enact and stimulate ethical behavioural conduct. Second, leaders including direct supervisors are primary actors in setting the tone for appropriate behaviours. Therefore, organisations should advance formal policies, programmes, and practices about role modelling ethical leadership and ethical standards to facilitate normative behaviours among subordinates (Brown and Treviño Citation2006). Moreover, leaders could consider the availability of resources and support in helping employees feel confident and safe to report workplace bullying, and ensure they take meaningful action to resolve potential bullying issues before they escalate.

Limitations and future directions

We utilized several procedural and statistical remedies to minimize the potential for CMV in this study, such as different end-point scales, post-hoc CMV checks, and multilevel analysis. Our concern about CMV was reduced when there was evidence for cross-level moderation effects of team power distance orientation. We would caution future studies in using cross-sectional data as an issue is the potential to conclude the causal relationships from our cross-sectional data given that workplace bullying could impact perceptions of ethical leadership in the opposite direction to what we predicted and observed (see also Stouten et al. Citation2010). Future research could collect data from multi-source and over multiple waves to bolster support for the causal paths in our model. We consider other consequences of EL and workplace bullying and through which cognitive and emotional mechanisms could be interesting in the future exploration.

This study controlled for dominant demographic variables related to EL and workplace bullying (Hassan, Wright, and Yukl Citation2014; Hoel et al. Citation2010; Zapf et al. Citation2011) in testing hypotheses. These control variables are consistent with the hypothesized model underlined by the aspects of SIP-SET integration to explore the boundary conditions of EL and workplace bullying on affective commitment. Although a recent review on leadership and workplace aggression, including EL and workplace bullying, argued that contextual factors are stronger predictors than individual or dispositional factors (Cao et al. Citation2022), we acknowledge that other factors could impact the research findings. We suggest future studies include additional control variables, such as affect, mood, or experience with the team, in resolving the bias. Future studies could apply trait activation theory to explore potential covariates of individual factors and the variables of interest.

This study only focuses on the moderation effects of team power distance orientation. We highlight a need for a mixed-method design in the future to discover more insights and narratives about workplace bullying exposure and how employees use social cues within the organisation to respond to and cope with mistreatment. Such research will advance our limited knowledge of workplace bullying pertaining to contextual conditions. We note that the findings are derived from public sector organisations in Vietnam. We expect to have consistent or competing results in the future research that can validate the possible applicability of the study to other sectors and regions. It would be insightful for future studies examining other leadership behaviours, work environment characteristics, other behavioural outcomes (e.g. public service delivery), and the impacts of different cultural variables to enrich our understanding of how various sources of social information work together in mitigating or encouraging workplace bullying. For instance, the GLOBE project indicates the associations of collectivism, humane orientation, or performance orientation with workplace bullying (Power et al. Citation2013). Finally, future research could focus on the generalization and expansion of our study in under-researched contexts involving more specific contextual conditions to validate the promising benefits of EL in minimizing psychosocial hazards such as workplace bullying to create healthy and safe environments for employees within the public sector.

Conclusion

We use SIP and SET theories to highlight the potential for two critical sources of social information to shape workplace bullying and reciprocal outcomes in different ways. Specifically, we present evidence of the primary role of EL in diminishing workplace bullying to nurture a healthy and safe work environment but highlight the potential for widely held cultural values – in this case, team power distance orientation – to bolster the positive effects. While we uncover new specific information about the roles of power distance orientation and EL in workplace bullying, at a broader level, our findings highlight the importance of considering the cultural context in understanding how the work environment manifests in bullying. We also highlight the strengthening impact of team power distance orientation on the harmful effect of workplace bullying on the emotional bond of employees with the organisation. Our study has managerial implications for public sector organisation in Vietnam and beyond, particularly regarding the need to execute constructive strategies to counteract the silencing effects of power distance while cultivating positive forms of leadership and desired work relationships with employees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Ahmad, S. 2018. “Can Ethical Leadership Inhibit Workplace Bullying Across East and West: Exploring Cross-Cultural Interactional Justice as a Mediating Mechanism.” European Management Journal 36 (2): 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.01.003.

- Ahmad, S., A. S. Sohal, and J. W. Cox. 2020. “Leading Well is Not Enough: A New Insight from the Ethical Leadership, Workplace Bullying and Employee Well-Being Relationships.” European Business Review 32 (2): 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-08-2018-0149.

- Aiken, L. S., and S. G. West. 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Ali, A., H. Wang, and J. A. Boekhorst. 2023. “A Moderated Mediation Examination of Shared Leadership and Team Creativity: A Social Information Processing Perspective.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 40 (1): 295–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-021-09786-6.

- Allen, N. J., and J. P. Meyer. 1990. “Organizational Socialization Tactics: A Longitudinal Analysis of Links to newcomers’ Commitment and Role Orientation.” Academy of Management Journal 33 (4): 847–858. https://doi.org/10.2307/256294.

- Bartram, T., P. Stanton, and K. Thomas. 2009. “Good Morning Vietnam: New Challenges for HRM.” Management Research News 32 (10): 891–904. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170910994114.

- Bauer, D. J., K. J. Preacher, and K. M. Gil. 2006. “Conceptualizing and Testing Random Indirect Effects and Moderated Mediation in Multilevel Models: New Procedures and Recommendations.” Psychological Methods 11 (2): 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.142.

- Bedi, A., C. M. Alpaslan, and S. Green. 2016. “A Meta-Analytic Review of Ethical Leadership Outcomes and Moderators.” Journal of Business Ethics 139 (3): 517–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2625-1.

- Bliese, P. D. 2000. “Within-Group Agreement, Non-Independence, and Reliability: Implications for Data Aggregation and Analysis.” In Multilevel Theory, Re-Search, and Methods in Organizations, edited by K. J. Klein and S. W. Kozlowski, 349–381. San Fran-cisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bliese, P. D. 2002. “Using Multilevel Random Coefficient Modeling in Organizational Research.” In Advances in Measurement and Data Analysis, edited by F. Drasgow and N. Schmitt, 401–445. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bond, M. H., K. C. Wan, K. Leung, and R. A. Giacalone. 1985. “How are Responses to Verbal Insult Related to Cultural Collectivism and Power Distance?.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 16 (1): 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002185016001009.

- Bos‐Nehles, A., E. Conway, and G. Fox. 2021. “Optimising Human Resource System Strength in Nurturing Affective Commitment: Do All Meta‐Features Matter?” Human Resource Management Journal 31 (2): 493–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12320.

- Boudrias, V., S. Trépanier, and D. Salin. 2021. “A Systematic Review of Research on the Longitudinal Consequences of Workplace Bullying and the Mechanisms Involved.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 56:101508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101508.

- Boyne, G. A. 2002. “Public and Private Management: What’s the Difference?” Journal of Management Studies 39 (1): 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00284.

- Brimhall, K. C. 2021. “Are We Innovative? Increasing Perceptions of Nonprofit Innovation Through Leadership, Inclusion, and Commitment.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 41 (1): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X19857455.

- Brislin, R. W. 1970. “Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 1 (3): 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301.

- Brown, M. E., and M. S. Mitchell. 2010. “Ethical and Unethical Leadership: Exploring New Avenues for Future Research.” Business Ethics Quarterly 20 (4): 583–616. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq201020439.

- Brown, M. E., and L. K. Treviño. 2006. “Ethical Leadership: A Review and Future Directions.” The Leadership Quarterly 17 (6): 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004.

- Brown, M. E., L. K. Treviño, and D. A. Harrison. 2005. “Ethical Leadership: A Social Learning Perspective for Construct Development and Testing.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97 (2): 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002.

- Bulutlar, F., and E. Ü. Öz. 2009. “The Effects of Ethical Climates on Bullying Behaviour in the Workplace.” Journal of Business Ethics 86 (3): 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9847-4.

- Cao, W., P. C. Li, R. van der Wal, and T. W Taris. 2022. “Leadership and Workplace Aggression: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Business Ethics 186 (2): 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05184-0.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Academic.

- Cropanzano, R., E. L. Anthony, S. R. Daniels, and A. V. Hall. 2017. “Social Exchange Theory: A Critical Review with Theoretical Remedies.” Academy of Management Annals 11 (1): 479–516. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0099.

- Daniels, M. A., and G. J. Greguras. 2014. “Exploring the Nature of Power Distance: Implications for Micro-And Macro-Level Theories, Processes, and Outcomes.” Journal of Management 40 (5): 1202–1229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527131.

- D’Cruz, P., E. Noronha, and A. Mendonca. 2021. Asian Perspectives on Workplace Bullying and Harassment. Singapore: Springer.

- Dollard, M. F., C. Dormann, M. R. Tuckey, and J. Escartín. 2017. “Psychosocial Safety Climate (PSC) and Enacted PSC for Workplace Bullying and Psychological Health Problem Reduction.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 26 (6): 844–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2017.1380626.

- Dorfman, P. W. and J. P. Howell. 1988. “Dimensions of national culture and effective leadership patterns: Hofstede revisited.” In Advances in International Comparative Management, edited by R. N Farmer and E. G. Goun, 127–150. JAI Press Inc.

- Ervasti, J., J. Pentti, P. Seppälä, A. Ropponen, M. Virtanen, M. Elovainio, T. Chandola, M. Kivimäki, and J. Airaksinen. 2023. “Prediction of Bullying at Work: A Data-Driven Analysis of the Finnish Public Sector Cohort Study.” Social Science and Medicine 317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115590.

- Farh, J. L., R. D. Hackett, and J. Liang. 2007. “Individual-Level Cultural Values as Moderators of Perceived Organizational Support–Employee Outcome Relationships in China: Comparing the Effects of Power Distance and Traditionality.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (3): 715–729. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.25530866.

- Fehr, R., A. Fulmer, and F. T. Keng‐Highberger. 2020. “How Do Employees React to leaders’ Unethical Behavior? The Role of Moral Disengagement.” Personnel Psychology 73 (1): 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12366.

- Fehr, R., K. C. Yam, and C. Dang. 2015. “Moralized Leadership: The Construction and Consequences of Ethical Leader Perceptions.” Academy of Management Review 40 (2): 182–209. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0358.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Freire, C., and M. I. Pinto. 2022. “Clarifying the Mediating Effect of Ethical Climate on the Relationship Between Ethical Leadership and Workplace Bullying.” Ethics & Behavior 32 (6): 498–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2021.1941027.

- Gelfand, M. J., M. Erez, and Z. Aycan. 2007. “Cross-Cultural Organizational Behavior.” Annual Review of Psychology 58 (1): 479–514. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085559.

- George, J. M., and K. Bettenhausen. 1990. “Understanding Prosocial Behavior, Sales Performance, and Turnover: A Group-Level Analysis in a Service Context.” Journal of Applied Psychology 75 (6): 698–709. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.6.698.

- Glasø, L., and G. Notelaers. 2012. “Workplace Bullying, Emotions, and Outcomes.” Violence and Victims 27 (3): 360–377. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.27.3.360.

- Hair, J. F., W. C. Black, B. Y. A. Babin, and R. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hansen, J. R., and A. M. Kjeldsen. 2018. “Comparing Affective Commitment in the Public and Private Sectors: A Comprehensive Test of Multiple Mediation Effects.” International Public Management Journal 21 (4): 558–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2016.1276033.

- Harvey, M., D. Treadway, J. T. Heames, and A. Duke. 2009. “Bullying in the 21st Century Global Organization: An Ethical Perspective.” Journal of Business Ethics 85 (1): 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9746-8.

- Hassan, S. 2019. “We Need More Research on Unethical Leadership Behavior in Public Organizations.” Public Integrity 21 (6): 553–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2019.1667666.

- Hassan, S., B. E. Wright, and G. Yukl. 2014. “Does Ethical Leadership Matter in Government? Effects on Organizational Commitment, Absenteeism, and Willingness to Report Ethical Problems.” Public Administration Review 74 (3): 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12216.

- Hewett, R., A. Liefooghe, G. Visockaite, and S. Roongrerngsuke. 2018. “Bullying at Work: Cognitive Appraisal of Negative Acts, Coping, Wellbeing, and Performance.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 23 (1): 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000064.

- Hoch, J. E., W. H. Bommer, J. H. Dulebohn, and D. Wu. 2018. “Do Ethical, Authentic, and Servant Leadership Explain Variance Above and Beyond Transformational Leadership? A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Management 44 (2): 501–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316665461.

- Hodgkinson, I. R., P. Hughes, Z. Radnor, and R. Glennon. 2018. “Affective Commitment within the Public Sector: Antecedents and Performance Outcomes Between Ownership Types.” Public Management Review 20 (12): 1872–1895. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1444193.

- Hoel, H., L. Glasø, J. Hetland, C. L. Cooper, and S. Einarsen. 2010. “Leadership Styles as Predictors of Self‐Reported and Observed Workplace Bullying.” British Journal of Management 21 (2): 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2009.00664.x.

- Hofmann, D. A., and M. B. Gavin. 1998. “Centering Decisions in Hierarchical Linear Models: Implications for Research in Organizations.” Journal of Management 24 (5): 623–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639802400504.

- Hofmann, D., M. Griffin, and M. Gavin. 2000. “The Application of Hierarchical Linear Modeling to Organizational Research.” In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations, edited by K. Klein and S. Kozlowski, 423–468. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Hofmann, D. A., F. P. Morgeson, and S. J. Gerras. 2003. “Climate as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Leader-Member Exchange and Content Specific Citizenship: Safety Climate as an Exemplar.” Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (1): 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.170.

- Hofstede, G. 1980. “Motivation, Leadership, and Organization: Do American Theories Apply Abroad?” Organizational Dynamics 9 (1): 42–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(80)90013-3.

- Hon, A. H., and L. Lu. 2016. “When Will the Trickle-Down Effect of Abusive Supervision Be Alleviated? The Moderating Roles of Power Distance and Traditional Cultures.” Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 57 (4): 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965515624013.

- Hu, J., B. Erdogan, K. Jiang, T. N. Bauer, and S. Liu. 2018. “Leader Humility and Team Creativity: The Role of Team Information Sharing, Psychological Safety, and Power Distance.” Journal of Applied Psychology 103 (3): 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000277.

- Jacobson, K. J., J. N. Hood, and H. J. Van Buren III. 2014. “Workplace Bullying Across Cultures: A Research Agenda.” International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 14 (1): 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595813494192.

- James, L. R. 1982. “Aggregation Bias in Estimates of Perceptual Agreement.” Journal of Applied Psychology 67 (2): 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.67.2.219.

- James, L. R., R. G. Demaree, and G. Wolf. 1984. “Estimating Within-Group Interrater Reliability with and without Response Bias.” Journal of Applied Psychology 69 (1): 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.1.85.

- James, L. R., R. G. Demaree, and G. Wolf. 1993. “Rwg: An Assessment of Within-Group Interrater Agreement.” Journal of Applied Psychology 78 (2): 306–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.306.

- Jiang, W., and Q. Gu. 2016. “How Abusive Supervision and Abusive Supervisory Climate Influence Salesperson Creativity and Sales Team Effectiveness in China?” Management Decision 54 (2): 455–475. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2015-0302.

- Jung, C. S., and A. Ritz. 2014. “Goal Management, Management Reform, and Affective Organizational Commitment in the Public Sector.” International Public Management Journal 17 (4): 463–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2014.958801.

- Kirkman, B. L., G. Chen, J. L. Farh, Z. X. Chen, and K. B. Lowe. 2009. “Individual Power Distance Orientation and Follower Reactions to Transformational Leaders: A Cross-Level, Cross-Cultural Examination.” Academy of Management Journal 52 (4): 744–764. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.43669971.

- Koopman, J., B. A. Scott, F. K. Matta, D. E. Conlon, and T. Dennerlein. 2019. “Ethical Leadership as a Substitute for Justice Enactment: An Information-Processing Perspective.” Journal of Applied Psychology 104 (9): 1103–1116. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000403.

- Kozlowski, S. W. J., and K. J. Klein. 2000. “A Multilevel Approach to Theory and Research in Organizations: Contextual, Temporal, and Emergent Processes.” In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations, edited by K. J. Klein and S. W. J. Koslowski, 3–90. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Kwan, S. S. M., M. R. Tuckey, and M. F. Dollard. 2014. “Dominant Culture and Bullying; Personal Accounts of Workers in Malaysia.” In Psychosocial Factors at Work in the Asia Pacific, edited by M. Dollard, A. Shimazu, R. B. Nordin, P. Brough, and M. R. Tuckey, 177–200. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Kwan, S. S. M., M. R. Tuckey, and M. F. Dollard. 2016. “The Role of the Psychosocial Safety Climate in Coping with Workplace Bullying: A Grounded Theory and Sequential Tree Analysis.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 25 (1): 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.982102.

- Lin, W., L. Wang, and S. Chen. 2013. “Abusive Supervision and Employee Well‐Being: The Moderating Effect of Power Distance Orientation.” Applied Psychology 62 (2): 308–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00520.x.

- Li, P., J. M. Sun, T. W. Taris, L. Xing, and M. C. Peeters. 2021. “Country Differences in the Relationship Between Leadership and Employee Engagement: A Meta-Analysis.” The Leadership Quarterly 32 (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2020.101458.

- Liu, C., L. Q. Yang, and M. M. Nauta. 2013. “Examining the Mediating Effect of Supervisor Conflict on Procedural Injustice–Job Strain Relations: The Function of Power Distance.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 18 (1): 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030889.

- Loh, J., S. L. D. Restubog, and T. J. Zagenczyk. 2010. “Consequences of Workplace Bullying on Employee Identification and Satisfaction Among Australians and Singaporeans.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 41 (2): 236–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022109354641.

- Loi, R., L. W. Lam, and K. W. Chan. 2012. “Coping with Job Insecurity: The Role of Procedural Justice, Ethical Leadership and Power Distance Orientation.” Journal of Business Ethics 108 (3): 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1095-3.

- López-Cabarcos, M. Á., P. Vázquez-Rodríguez, and J. R. Piñeiro-Chousa. 2016. “Combined Antecedents of Prison employees’ Affective Commitment Using fsQca.” Journal of Business Research 69 (11): 5534–5539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.167.

- Lu, J., Z. Zhang, and M. Jia. 2019. “Does Servant Leadership Affect employees’ Emotional Labor? A Social Information-Processing Perspective.” Journal of Business Ethics 159 (2): 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3816-3.

- Matthews, S. H., T. K. Kelemen, and M. C. Bolino. 2021. “How Follower Traits and Cultural Values Influence the Effects of Leadership.” The Leadership Quarterly 32 (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101497.

- Mayer, D. M., K. Aquino, R. L. Greenbaum, and M. Kuenzi. 2012. “Who Displays Ethical Leadership, and Why Does It Matter? An Examination of Antecedents and Consequences of Ethical Leadership.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (1): 151–171. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.0276.