ABSTRACT

This qualitative study investigates the managerial practices adopted during the Covid-19 emergency in Lombardy, Italy, amidst unforeseen changes in public service ecosystems. Using longitudinal data, we identify seven key practices adopted by public service managers to organize amidst disruption. Our findings underscore the public managers’ role in fostering adaptation, innovation, and coordination among ecosystem actors. Extending roles outlined by Osborne et al. as ‘appreciate, engage, and facilitate’, our study reveals how these roles were interpreted following logics of entrepreneurial stakeholder engagement, rather than citizen-centred services. We discuss conceptual implications to further develop the theory and practice of public service management.

Introduction

We study the managerial practices for public service provision during the Covid-19 emergency, specifically during the so-called lockdown period (a time interval when citizens were required by law to stay at home). Specifically, we focus on the managerial practices that have been enacted to keep public service ecosystems functioning amidst the pandemic disruption. Our empirical context resides in the first and most hard-hit region in Europe, Lombardy (Italy), with emphasis on public services that were essential for the fight against the emergency, spanning from social services to food distribution and policing and in general including all the emergency services ad hoc activated excluding health services.

We aim to answer the following research question: What are the managerial practices that enable value co-creation within public service ecosystems amidst disruption? We now define some key terms that qualify our research question. Drawing from Perry and Pescosolido (Citation2012) and Chen et al. (Citation2022), we define disruption as a sudden and unexpected change in the structure and in the composition of an inter-organizational social network (a public service ecosystem in our context), which forces managers and members to re-structure and re-organize their connections. Drawing from Skålén (Citation2022, 22), we consider practices as ‘organized ways of doing things that individual (e.g. a citizen) and collective actors (e.g. a PSO) recursively perform to conduct concrete activities’, where PSO stands for Public Service Organizations. This definition highlights the collective, relational, and institutional dimensions embedded in a practice view of public services, where the units of analysis are inter-organizational cultural and social practices, and not individual actors as such. Given our focus on public service managers, we are particularly interested to analyse in this paper the first part of the definition of Skålén (Citation2022), which emphasizes the ‘organized ways of doing things’, and the role played by public service managers (e.g. S. P. Osborne, Powell, et al. Citation2021). Following Osborne (Citation2020), we then define value (co)creation (or (co)destruction) as a construct that extends across institutional, societal, organizational, local, individual, and belief levels within the architecture of public service ecosystems. Specifically, per value co-creation we limit our investigation to value at the societal and service level, so value in production and value in society (S. Osborne et al. Citation2022), where per society we mean the ‘public value enjoyed by society’ (Cui and Aulton Citation2023) as enshrined in the achievement of collectively agreed policy goals, and per service-level value we mean the ‘management/governance of public services and the use of learning to improve and innovate in the service delivery system – enhancing the processes of value creation within public services’ (S. P. Osborne, Powell, et al. Citation2021, 669). Thus, we concentrate on the meso (in part) and macro level of value, where our take of the meso-level value lies in adaptation and resilience (improve and innovate) to keep public services functioning amidst disruption (Dudau et al. Citation2023), and at the macro level it does reside in the public value(s) achieved from a societal point of view. The definition of these key terms provides the conceptual map that guides our study. Overall, this paper offers unique insights on how public service managers approached the disruption of their public service ecosystems (Petrescu Citation2019) during the emergency phase of the viral outbreak, providing a unique empirical dataset about a peculiar moment that has been defined by Boin et al. (Citation2020) as a ‘once in a lifetime’ event. We contribute to public management research by adding empirical evidence about the managerial practices that were enacted to ensure public service provision at a unique moment characterized by disruption and transition into a very intensive use of digital tools, a peculiar and extreme case study. Namely, we show what type of managerial work was essential to change and/or reconfigure the boundaries, actors, technologies, relationships, and resources to make public service ecosystems functioning during the Covid-19 lockdown.

The paper is structured as follows: the following (second) section provides an overview of our theoretical approach; the third section presents the methodology of the research; the fourth section reports our findings, which are then discussed in the fifth and last section, where also some concluding remarks and limitations of this study are highlighted.

Theoretical background: managerial practices and public service ecosystems

Our theoretical background is centred on the recognition that public service managers have a key role in managing public service ecosystems to enhance value co-creation by users and among different stakeholders. The conceptual genealogy of this theoretical positioning can be traced back to several literature sources. Our focus on public service managers aligns our paper to the public value governance approach (e.g. Bryson, Crosby, and Bloomberg Citation2014; Moore, Citation1995) and to other studies on public management (e.g. Bartelings et al. Citation2017; Sancino and Turrini Citation2009; Sullivan, Dickinson, and Henderson Citation2021; van der Wal Citation2017, Citation2020; van Dorp and Hart Citation2019). Within this domain, Moore’s contribution (Citation1995) stands out as a significant reference, emphasizing an entrepreneurial management style for public managers to generate public value through creativity, entrepreneurialism, social innovation, and political astuteness, among other factors (e.g. Hartley et al. Citation2015; van Gestel, Ferlie, and Grotenbreg Citation2023). Moore’s work not only responds to New Public Management (NPM) but also selectively integrates a limited number of its concepts, such as entrepreneurialism, innovation and leadership, legitimizing them for public managers akin to their counterparts in the business sector. However, this literature was notably silent on the specifics of the disparate public services and of their unique characteristics (e.g. Virtanen and Jalonen Citation2023). This gap was addressed by Osborne (Citation2020), emphasizing the significant role that public managers, and more broadly, public service professionals, play in shaping and enhancing public service(s), meaning here both public services as an industry and service as a ‘value creation process’ (S. P. Osborne, Powell, et al. Citation2021, 669). According to him, ‘the service processes require the active engagement of public service managers in their design, co-design, co-production, and delivery’ (S. P. Osborne, Cucciniello, et al. Citation2021, 669).

The contribution of Osborne is seminal because it provides a clearer identity for public management as an academic and professional discipline (Barzelay Citation2019) by embracing a public service and value co-creation perspectives. Moreover, Osborne’s work marked a paradigm shift from New Public Management (NPM) by emphasizing the significance of Public Service Logic (PSL) towards exploring citizen centred public services and value co-creation from a service perspective. Here, we focus on the work of Osborne mainly for the part which highlights a strategic role for managers in public service. Specifically, S. P. Osborne, Powell, et al. (Citation2021) pointed out the role of public service managers as professionals able to understand the societal context and the beliefs/values/social capital endowments present in each place (the so-called ‘appreciate’), to engage stakeholders and users in public service organizational processes (‘engage’) and to facilitate value-adding interactions among actors, institutions, resources, and technologies that constitute a public service ecosystem (‘facilitate’). In particular, from a PSL perspective, they should do that by embracing a strategic user orientation which is different from stakeholder management (S. P. Osborne, Cucciniello, et al. Citation2021). This approach – which understands public services and public service for what they are, and as such different from a manufacturing logic – does recognize the systemic and extra-organizational level for analysing and enacting value co-creation (or co-destruction) processes, because not all interactions can be formally organized into (inter)organizational arrangements and/or public service networks. As written by Kinder et al. (Citation2022), this implies clearly distinguishing between ecosystems and networks to acknowledge that value in local public services is co-created (or co-destroyed) also through informal processes, multiple and decentralized responses and autonomous and self-organizing agents within ‘a volatile environment demanding a high rate of learning and innovation for which ecosystems are increasingly proving a preferable form of organizing’ (Kinder et al. Citation2021, 1620). This requires moving from an inward to a systemic focus on public service delivery systems and shifts the focus from individual service firms or networks to complex and interactive service ecosystems, encompassing key actors and processes of value creation, as well as societal institutional values and rules. According to Strokosch and Osborne (Citation2020, 429) ‘the ecosystem perspective suggests that value is not delivered in a linear fashion by PSOs working in isolation, or even through the horizontal relationships that characterise networks and service encounters’.

Within this perspective, a public service ecosystem (PSE) can be defined as a framework and organizing principle that brings together institutions, multiple actors, and the technologies and resources involved in the value creation through the service provision (S. P. Osborne, Cucciniello, et al. Citation2021). It ‘incorporates a comprehensive, 360-degree view of all the individuals, technologies, and institutions involved in the creation and delivery of value generated through the public system and adjacent private stakeholders’ (Petrescu Citation2019, 1740). The notion of a PSE has been introduced by the PSL to explain the relational nature of the value creation (or destruction) processes occurring amongst multiple stakeholders and from the perspective of the users/citizens. However, the notion of ecosystem is not new in strategic management research, where, for example, Adner (Citation2017, 40) defined an ecosystem as ‘the alignment structure of the multilateral set of partners that need to interact in order for a focal value proposition to materialize’. Moreover, within public management, Alford and Yates (Citation2014) in their exploration of mapping public value processes shed light on where value might be co-created or co-destroyed beyond a public service organization, implicitly taking an ecosystem-level perspective on value co-creation (Trischler et al. Citation2023). However, within public management, now the notion of PSE is mainly equated with PSL; for example, as argued by Petrescu, ‘the concept of service ecosystems, centred on integrating actors and resources through systems and institutions, can be useful in drawing new conceptual avenues for coproduction and value co-creation in public services’ (Petrescu Citation2019, 1733). We don’t question this statement on which we agree but relying upon strategic management literature (e.g. Foss, Schmidt, and Teece Citation2023), on some recent developments/critiques of the PSL (e.g. Eriksson et al. Citation2022; Kinder and Stenvall Citation2023; Trischler et al. Citation2023), as well as on the work of Osborne focused on public service managers (S. P. Osborne, Powell, et al. Citation2021), we recognize the work of managers and their leadership, entrepreneurial and/or innovative role in enabling ecosystem emergence and in solving problems of cooperation and coordination within and across ecosystems. In this respect, Foss et al. (Citation2023) identified three externally oriented dynamic capabilities for enabling ecosystem emergence: sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring/transforming stability as well as three stages to enable/accompany an ecosystem to unfold, namely: to emerge, become stable, and mature successfully. Thus, from our theoretical positioning and in agreement with some recent developments/critiques in the PSL emerging literature, there is a clear role for public service managers in overseeing PSEs for sorting out coordination and cooperation issues and let them develop and adapt over time depending on environmental circumstances; we believe this role should not be overlooked in the value co-creation processes occurring within PSEs. For example, the ‘integration of actors, resources, and processes within PSEs’ (S. Osborne et al. Citation2022, 641) relies on key integrative work (e.g. Crosby and Bryson Citation2010; Morse Citation2010), such as designing and enabling platforms to co-create value with users and/or citizens as well as through multi-actor resource integration and coordinated value propositions (Eriksson and Hellström Citation2021; Eriksson et al. Citation2020).

In summary, our theoretical backdrop is grounded in the conceptual link between public service ecosystems and managerial practices, understanding and exploring the latter as both the human agency intervening in interactions between actors, resources, and technologies and the human agency exercised through the design of institutions and processes that generate connections within and among a public service ecosystem(s) (Barzelay Citation2019; Nasi and Choi Citation2023; Trischler and Trischler Citation2022). However, while we acknowledge a new level of analysis for public management research and practice by understanding the task of public service managers as managing public service organizations at the ecosystem level as posited by the PSL, our conceptual framing and research design still fail to embrace the PSL as conceptual inspiration for analytic purposes. Indeed, given the extreme context of our research setting, we could not collect data at the ecosystem level, and we could not consider how users co-create value by engaging with public service propositions and integrating resources available in the ecosystem, which is a limitation of our approach. However, our study captures managerial practices that show how public service organizations deeply rooted in entrepreneurialist approaches aligned with the NPM philosophy of public management may resort to the work of public service managers to maintain the functionality of public service ecosystems during periods of disruption and emergency.

Methodology

Research setting

We conducted a qualitative study on the managerial practices enacted to keep public service ecosystems functioning during the Covid-19 lockdown in the most affected Italian region (Lombardy), which was the first European region hardly hit by Covid-19. To narrow down the focus of this study to the emergency phase in respect of theoretical saturation concerning this unique moment (Sklaveniti Citation2020), we restricted the analysis to the managerial practices pursued during the periods of so-called lockdown occurred in Lombardy in 2020, specifically March–May 2020 and November–December 2020.

Qualitative data collection

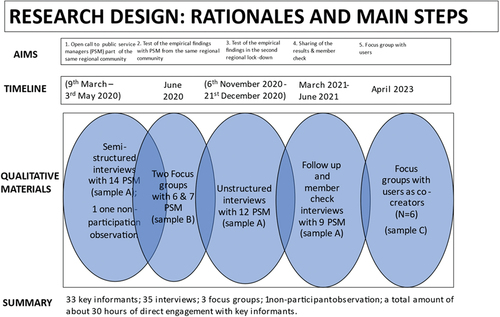

As shown in , we collected our data in five rounds of data collection through three main sources: (i) semi-structured interviews (sample A); ii) three focus groups (sample B and sample C); iii) one non-participant observation. Specifically, between early March and early May we conducted semi-structured interviews with 14 public service managers, and, upon invitation, we conducted one non-participant observation of a virtual meeting organized by the municipality of Bergamo (Italy) with all the top public service managers. After the lock-down period, in June 2020, 2 focus groups (FG) were conducted with an overall number of 13 public service managers who were not previously interviewed to test with another sample (B) what emerged in our first interviews (sample A). As a third step, between November and December 2020 during the second regional lockdown, we conducted 12 interviews with 12 out of the 14 public service managers we interviewed during the first lockdown (two public service managers were not available for an interview during those two months). Fourth, between March and June 2021 we conducted another round of follow up and member check interviews with nine public service managers already interviewed two times in 2020 (still sample A). Finally, upon suggestion by a reviewer of the paper, we conducted another focus group with six citizens/users from the public service ecosystems considered (sample C), further discussing the managerial practices identified. Overall, we conducted 35 interviews and 3 focus groups; altogether, 33 key informants took part in our research for a total amount of about 30 hours of direct engagement of the authors with key informants (including the interviews, the non-participant observation and the three focus groups). Part of this paper sample was developed within a larger research project that also involved research emphasis on networking; however, no material used in this study was used for the other outputs of the research project. Public service managers responsible for public service provision were the main informants of our analysis, while their managerial practices are the unit of our interpretative analysis. Specifically, the unit of analysis in our study was the analysis of the managerial practices aimed at better understanding how, from the perspective of public service managers, ‘resource integration and value co-creation are realized through real activities and interactions in service [eco]systems’ (Edvardsson, Skålén, and Tronvoll Citation2012, 82). All the public service managers involved in this research were part of the same regional community, which is Lombardy, and they were selected through a mix of purposive, snowball and convenience sampling. The interviews lasted on average about 40 minutes. Interviews were recorded and conducted by phone, Skype, Google Meet, Cisco Webex, WhatsApp, depending on the preferred platform chosen by the interviewees. When we were not able to record the interview due to technical issues, we took detailed notes and validated quotes with the interviewees. Following other studies (e.g. S. Ospina and Foldy Citation2010), questions were asked to elicit narratives from participants about their managerial work, rather than about their attributes and qualities. As written by McColl-Kennedy et al. (Citation2012, 376), ‘central to this view is that the only way to understand reality is through asking individuals directly about their ‘“sense-making”’ activities – that is, what is meaningful to the individuals’, where ‘meaning is associated with social interactions as well as roles and positions within a social system’. Specifically, respondents were asked to describe – also through the use of stories, metaphors, and personal feelings: (i) the effects of the disruption caused by the lockdown on the provision of public services for their cities and communities; (ii) what actions (both operational and symbolic) were taken to ensure organizational functioning during the lockdown, also with a focus on the role of digital technologies; (iii) finally, we also encouraged the public service managers interviewed to share any further insights that they thought to be relevant, including a message about the most important thing(s) they did and they learnt in public service management during the Covid-19 lockdown. We stopped interviewing public service managers (see ) when – as a research team – we reasonably agreed to have reached theoretical saturation of data (Eisenhardt Citation1989).

Table 1. Roles and public services focus of the public service managers interviewed – total number of interviews N = 35.

Qualitative data analysis

Drawing from themes and narratives about the managerial work enacted within public service ecosystems amidst the Covid-19 lockdown, we used a qualitative thematic analysis method (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) grounded in an interpretive (S. M. Ospina and Dodge Citation2005) and abductive approach (Alvesson and Skoldberg Citation2018).

There were multiple rounds of data analysis, where the transcribed material was reduced through various steps of coding and discussions were held between the co-authors, who all participated in the coding of the interviews. Firstly, all passages who described a managerial practice as above defined were highlighted. Secondly, this condensed material was employed for more focused coding, generating through abduction three main themes: (i) managing public service ecosystems through the design and establishment of structures connecting actors, resources, and technologies; (ii) managing public service ecosystems through enabling value adding relationships among ecosystem actors; and (iii) managing public service ecosystems through communication and engagement. These three main themes, which emerged as the most appropriate groupings of the managerial practices identified, derived from a combination of deductive thinking based on literature knowledge and inductive analysis from qualitative data obtained. Third, we revised and did member check-interviews and an additional focus group with citizens/users to identify and validate the seven managerial practices reported below in . To address the claim about the importance of showing qualitative data (Pratt, Kaplan, and Whittington Citation2020) and to fulfil criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of good and trustworthy qualitative research (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985), details on the main themes and extensive exemplary quotes are provided and reported in the online appendix.

Table 2. Managing public service ecosystems in times of emergency: learning from Covid-19.

Findings

Confronted with an unprecedented emergency that put extreme pressure on their managerial work, the public service managers interviewed gave emphasis to their patterns of relationships – in terms of both personal and professional interactions within and beyond their public service organization – as a fundamental element of response to the emergency. As one public service manager remarked, ‘There is no King Arthur without the round table. It’s absurd, but before Covid-19 this reflection was often neglected’ (PSM 8). They also claimed that the outbreak brought a sudden disruption in their professional relationships, such that ‘The relationship with people has changed. We could no longer maintain proximity and direct contact with people even if this is the key principle of Carabinieri’ (PSM 9).

The need to establish interactions to either help or receive help from others emerged from all interviews as the least common denominator. The sudden rupture of consolidated and stable structural patterns pushed public service managers within public service ecosystems to activate and leverage relational resources to provide organizational solutions to individual and collective problems. This trend is evident at three levels of analysis, involving the structures underpinning a public service ecosystem; the dynamics of interpersonal relationships; and the processes of communication and engagement towards actors within and beyond a public service ecosystem. These three elements can be considered as the theoretical underpinnings connecting the micro-layer of interactions and the macro-layer of organizational and structural arrangements. Below, we describe our findings in greater detail for each of these three relational dimensions – for further qualitative evidence about our data, see the online appendix.

Managing public service ecosystems through social and public service structures

Edvardsson et al. (Citation2012, 81) have explained that ‘social and service structures provide actors with resources which they integrate in order to cocreate value in a service system’.

The outbreak of the virus caused a sudden disruption of existing structures of public service ecosystems, forcing actors within public service ecosystems to find new routes to get access to key resources to maintain organizational functioning. Here, we identified two key managerial practices in our data.

Innovating and designing new digital service structures for interaction and resource integration

The disappearance of stable patterns led public service managers to open their connections, expanding opportunities for interaction beyond local connections and spanning across different and even distant communities. New digital tools were used such as mailing lists with key actors (for example, doctors and local businesses) and WhatsApp groups for different purposes (e.g. managing volunteers for food distribution; exchanging views with members of the emergency committee ad hoc created; leading teams responsible for some specific public service task). For example, an aggregation of mayors (called ‘Patto dei Sindaci’) which was already existent became a key arena to share information to enhance resource integration on daily basis, and all was via an ad hoc WhatsApp chat (Focus Group 2); moreover, crowdfunding platforms were established as well as digital local platforms for ‘mix and match’ local needs with volunteers and resources available in the broader environment, so beyond the boundaries of a single public service ecosystem. One public service manager pointed out: ‘the municipality website has become a forum for communicating with families. Even Facebook has proved very useful because it is more agile than the municipality website’ (PSM 11).

Opening public service ecosystems boundaries and expanding contributions

We observed from the data the emergence of two main managerial practices: first, opening public service ecosystems to new actors, such as, for example, co-producing public services with new volunteers as in the case of provision of food and health equipment to those in need; contacting new providers crucial for the functioning of public services, such as providers of masks and health equipment, builders for re-arranging buildings and infrastructures to new purposes (for quarantine and/or for assistance). Second, expanding the connections to distant or dormant actors and sharing contributions and resources received within the public service ecosystem with other public service ecosystems. Through these patterns of public service ecosystem openness, public service managers tried to achieve two main goals: finding rapid solutions to organizational problems and sharing resources within and across public service ecosystems. This is well epitomized by the example reported below from a public service manager, where a municipality distant 110 miles offered managerial support and resources, a kind of structural collaboration which was unimaginable before Covid-19:

to help the funeral companies now exhausted, even companies from Trento are coming, thanks also to the relationships woven between our municipalities in these years. This is a beautiful and useful lesson: weave positive relationships between institutions when you are not in emergency. (PSM1, 18th March, English translation.)

Thus, even if far away, those municipalities were working together because of the Coronavirus and because of previous relationships of ‘institutional friendship’. As written by Milward and Provan (Citation2006, 6), ‘past cooperative relationships prove useful in managing a problem-solving network’; in that respect, some public service managers were agentic in reaching out distant communities to find solutions, thus forming outgoing ties that squeeze organizational and social distance. As a public service manager said, ‘In the first days of the emergency, every day, something important was missing: face masks, other material, etc … Thus, I took my car, and I went personally to find this material. I established contacts with other people who all wanted to help, but they did not know (yet) how to do so’ (PSM 3). Similarly, some public service ecosystem actors were also agentic through opening public service ecosystems to others, with the aim to share resources within and outside their organizations and communities – ‘I realized that these connections were quite useless if they were just “my” connections. Thus, I opened my network to everybody. It was easier to get things done’ (PSM 7).

Managing public service ecosystems through relationships

As written by Osborne (Citation2018) ‘the value creation relationship is not a simple dyadic one, but is rather dependent upon relationships between the user, a network of PSOs, and possibly also their family and friends’ (227). Ecosystem relationships founded on learning and feedback are thus central to processes of value co-creation. Managing public service ecosystems amidst disruption entailed a focus on how relationships were reconfigured and on how actors interacted among each other. Changes in the overall structure of public service ecosystems indeed required adaptation and innovation in the relationships of ecosystem actors to sustain change and stability, innovation and adaption (Bolden, Gulati, and Edwards Citation2020) according to a ‘co-evolutionary logic related to interdependency in interactions and processes between actors, technologies, and institutions, as well as consideration given to the contextual breadth of the interactions’ (Petrescu Citation2019, 1733–1734). Specifically, we observed in the data three managerial practices.

Managing the intensity of the interactions

The management of the intensity of the interactions describes the ability of public service managers to activate, de-activate and re-activate different interpersonal ties in different phases of the emergency, something Ansell et al. (Citation2021) have also described as scalability. Because Covid-19 crisis introduced a short-termed time horizon in most public service managers’ actions, this required the flexibility to leverage specific interactions according to specific organizational needs (Operti, Lampronti, and Sgourev Citation2020). From a temporal perspective, managers showed an extraordinary ability to rapidly activate, shape and terminate ties connecting ecosystem actors, based on situational and contextual contingencies. As described by a public service manager responsible for emergency services of the territorial area, ‘A major organizational effect of this crisis is that the virus also killed time’ (PSM9); another pointed out how ‘it is impressive how with the use of digital meetings everybody arrives on time’ (PSM1). From our findings, managing the interactions among the ecosystem actors was like regulating the volume intensity when engaging with the radio’s button. A public service manager said: ‘unlike before, the communication to the users of the services took place every 3–4 days – to give recommendations, to give operating instructions, to not disattend government directives’ (PSM8). In particular, the management of the interactions through digital tools because of the situation of lockdown required some new adjustments in the communications and interactions that became more vertical: a key informant said ‘I have learned some key things in managing digital interactions: clarity and brevity of messages (use it for giving concise and clear instructions, stop and don’t use for discussions); flexibility (be prepared to travel from different conversations topics); design groups membership carefully (include only homogenous people); share emotions (e.g. vocal messages, motivating messages and emoticons) in key moments, especially at the beginning and end of the day’ (PSM4). Also, in terms of administrative procedures, public service managers needed to proceed with accelerations such as quick approvals of extensions and modifications of payments, accesses and concessions; acquisition of supplies and services in a very short time; modification of contracts and services (cleaning, educational assistance, etc.).

Evolving and changing roles of ecosystems’ actors

Kinder et al. (Citation2021) highlighted that public service ecosystems are persistently dealing with change and stability and thrive by forming new roles, relationships and responsibilities as new solutions emerge at an individual, team and service organizing levels (Kinder et al. Citation2021, 1614). Ansell et al. (Citation2021) described a similar concept by using the term strategic polyvalence also referring at the Covid-19 governance responses. In this respect, it is important to highlight that managerial practices within public service ecosystems during the Covid-19 were often characterized by innovations. Uhl-Bien and Arena (Citation2018, 89) explained that leadership for organizational adaptability is different from traditional leadership or leading change and it involves enabling the adaptive process by creating space for ideas advanced by entrepreneurial leaders to engage in tension with the operational system and generate innovations that scale into the system to meet the adaptive needs of the organization and its environment. The impossibility to plan interactions in the mid and long run, and the parallel need to get immediate access to resources, urged public service managers to re-activate ties that were inactive for long time but that, once re-activated, could offer rapid benefit. The relevance of such ‘dormant ties’ or relationships ‘between two individuals who have not communicated with each other in a long time’ (Levin, Walter, and Murnighan Citation2011, 923) has proven in this study to be one of the most used mechanisms by public service managers amid disruption for problem-solving.

Differently, evolving and changing roles of ecosystem actors refer to the change in the nature of relationships, which was generated in this context by the requirements of the emergency. In Bergamo, the municipality passed in few days from 30 to 410 smart workers and into digitizing many of the bureaucratic procedures. Moreover, supermarkets – as the only places where people could form gatherings – became a crucial actor to enforce the rule to customers to avoid the diffusion of the virus’ (Focus group 1). Volunteers played a key active role in supporting the mayors in the management of the crisis, and they mainly were part of structured associations like Protezione Civile, Vigili del Fuoco, Associazione Alpini but were also enrolled from common citizens; they were activated and de-activated in a very fluid way according to the circumstances (Focus Group 1). As described by a member of the cabinet responsible for emergency services, ‘I thought about the job of my Sunday league’s football mates. Luca [fictional name] is the manager of a multinational company in the textile industry. So perhaps he has connections abroad that can help us buy face masks. I just called him, and indeed he was of help’ (PSM12). Another description of changing and evolving roles is illustrated by a public service manager of a social cooperative playing a key role in food distribution, who said, ‘It is surprising how Covid-19 allowed me to build new connections with friends and colleagues that were almost lost in my memory. Previous relations that were kind of forgotten now are incredibly important’. (PSM7).

Generosity

We use the term generosity in relation to a public service ecosystem because we observed that during the emergency it was violated one of the key principles of social interaction: reciprocity. We normally see in organizational settings the tendency for social connections to be reciprocated: if a first actor provides resources to a second actor, there is a natural tendency for the second actor over time to provide resources to the first actor too. On the contrary, in our setting actors within and across public service ecosystems tended to connect to others without expectations of ‘do ut des’, such that ‘I help others without expecting any return. I think it’s the same for everybody’ (PSM 10). A public service manager used a metaphor to express this concept:

My dad used to say that a good chief farmer starts ploughing the earth before dawn, if he wants to be followed by the other farmers. I thought about these words in the last weeks. I tried to behave like that farmer, and my people understand my effort, and they also do their best. (PSM2)

However, despite the positive and pragmatic attitude of most public service managers towards others, our data also revealed the presence and the diffusion in the public service ecosystems of stress, discomfort, and frustration, both for the gravity of the situation and for the many organizational disruptions that our respondents experienced.

Managing through communication and engagement

Kinder et al. wrote that multi-directional communication of ideas is central to develop collective consciousness through ‘agents in teams continually signaling by actions and shared ideas, responses to external events or initiatives by other agents’ (Kinder et al. Citation2021, 1615). As regards this relational dimension, two key managerial practices emerged from our analysis.

Storytelling through metaphors and stories

Many public service managers engaged in emotional labour (e.g. Wankhade Citation2021) by storytelling through metaphors and stories. Ecosystem actors tended to share and socialize their fears and hopes, thus opening the entire ecosystem to empathy – something that, in time of lockdown, was usually supported by technological tools. ‘The problems of one became immediately the problems of all. We were listening to each other as we never did before’ (PSM6); another public service manager said ‘videos are very important for communicating. Through Facebook dentists brought us masks. Moreover, there was a farmer which saw the message on Facebook and gave 500 kg of apples to the municipality’ (PSM2). Closeness was paradoxically pursued not by physical proximity, but through digital means. This is well symbolized by two narratives: ‘The feeling of the lockdown period may be summarized by the message I received from a person: it was nice to receive your audio message with the bells ringing’. (Focus group 2); ’I believe that we must always never let hope abandon us. Sometimes the grass sprouts from the asphalt. This must be the soul that must house’ (PSM 14);’. We won’t be able to do everything. We will make mistakes. But hope is what must guide us’ (PSM5). ‘The sun will be born after the night anyway’ (PSM2).

Framing & education

Kinder et al. (Citation2021, 1612) pointed out that ecosystems are led ‘by creating an overall consciousness of the service system goals, educating and helping other active agents in the service to become legitimate and exercise power’. The role of framing and education was key to educate ecosystem actors and to keep public service ecosystems functioning during the lockdown. New and/or old media became key for providing and intermediating information between government and citizens (e.g. Peters Citation2016). Public service managers needed to share the interpretation of each government decree to coordinate decisions and actions and to communicate to citizens. Of course, framing might be controversial (e.g. Corriere della Sera Citation2020; la Repubblica Citation2020) and might be differently received by different publics (Sancino et al. Citation2020) or different levels of government. We also noticed the tendency of public service managers to engage in processes of communication and engagement through affective framing and by acting as educators to provide information, advice and recommendations to the community for providing knowledge of changing local services and regulations.

Discussion and conclusions

Our objective in this study was to better understand the managerial practices that were implemented to ensure public service provision during the Covid-19 lockdown. Through an abductive and interpretative qualitative study, we studied the managerial practices from the perspective of public service managers in Lombardy, northern Italy, during two different periods of lockdown in 2020, and we showed that the outbreak required several managerial practices to keep public service ecosystems functioning amid disruption.

Specifically, we identified seven key managerial practices (shown in , second and third column) which are clearly interrelated among each other and should be considered as ‘bundles of practices’ that ‘consist of practices linked closely together in coordination with one another’ (Skålén Citation2022, 24). These managerial practices confirm and align with the three roles for public service managers to appreciate, engage, and facilitate highlighted by Osborne et al. (Citation2021). They also provide further knowledge and details on how these roles might be practiced. Specifically, in terms of the role named ‘appreciate’, drawing from our findings we extend the conceptualization provided by Osborne arguing that public service managers may alter and impact on societal values and beliefs upon value creation through practices of storytelling and framing which can contribute to build new and/or reframe discourses on public values; see on this also other studies, such as, for example, Ospina and Foldy (Citation2010) regarding prompting cognitive shifts and Røhnebæk et al. (Citation2022) on the creation of value propositions through framing. Accordingly, our paper underscores the importance of the strategic use of digital forums and social networks for contemporary public service management in the information age (Meijer, Lips, and Chen Citation2019), showing the potential of a leadership role for public service managers – especially at certain moments in public life such as emergencies and crises – to influence and/or change values, behaviours and beliefs of citizens and of organizational stakeholders through storytelling and framing. We think exploring how public service managers use storytelling and framing to manage increasingly digitized ecosystems will be a particularly promising area of research, especially to understand how these practices may contribute to foster collective consciousness and create emotional mutual commitment among users as co-creators.

In terms of the role named ‘engage’ we found the rising importance of platforms as a mode of organizing (e.g. Ansell and Gash Citation2018) and of designing as tool and practice to visualize, map and structure ecosystems (Strokosch and Osborne Citation2023). In this respect, we noticed the importance of an entrepreneurial attitude towards stakeholder engagement and stakeholder management using creativity, political astuteness, and social imagination (e.g. Hartley et al. Citation2019; Kruyen and van Genugten Citation2017) for recombining public service ecosystems, such as, for example, by inviting new actors into an existing public service ecosystem and by transforming existing governance relationships (like, for example, in the dramatic case of the municipality of Bergamo inviting the Army to collaborate to help carrying dead bodies).

For what concerns the role named ‘facilitate’, as recognized by Kinder and Stenvall (Citation2023) and by Virtanen and Jalonen (Citation2023), our findings highlighted the importance of professionalism in facilitating and enabling interactions for value co-creation in public service ecosystems. For example, facilitating users as co-creators to integrate resources from stakeholders’ part of the public service ecosystem, building new connections through a strategic use of digital tools, and sharing data with the relevant stakeholders are all practices that were necessary to allow public service ecosystems to function in conditions of emergency.

Of course, this study presents some limitations. We have considered a particularly extreme type of context. It is probable that the managerial dynamics were influenced by immediate and direct exposure to the necessity of organizational reaction; moreover, we noticed that some of the practices identified may not add or co-create value, but they might be pursued to destroy value . We now turn to some concluding remarks. By reflecting upon some conceptual implications from our study, we believe that future research endeavours should explore the tensions arising from the coexistence of diverse and competing models of public service management, such as NPM and PSL. Discussing our findings against NPM and PSL, we observed patterns close to NPM because of the acknowledgement of managerialism, in particular, the entrepreneurial and leadership role of public managers, but also patterns aligned with some key concepts of PSL, such as the recognition of the ecosystem-level for value creation, which has been labelled by Dudau et al. (Citation2023, 1583) as the fourth wave ‘of service-based thinking in public services’. In this regard, the findings of our paper, even with the limitations of the extreme case study, shed light on one interesting theoretical issue for developing public service management, namely how to combine a new type of strategic management of PSO to be enacted at the ecosystem level and with a strategic user orientation (S. P. Osborne, Cucciniello, et al. Citation2021), something also Bryson is recently pointing to from a collaborative governance perspective when speaking about strategy management at scale (Bryson et al. Citation2021). We refer to strategic management without interpreting it as a top-down tool of management rooted in NPM principles as it would neglect a foundational perspective for the PSL where users are at the core of co-creation of value processes since the service providers can only offer a value proposition and get the opportunities to co-create value with the users (S. P. Osborne Citation2018). Finally, as a future area of research, we believe it will be important to discern the incentives and processes that may foster a shift from NPM to PSL, recognizing that this shift raises fundamental questions about redistributing power from a positional and hierarchical managerial perspective to one that emphasizes user-centric facilitation and social learning.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the public service managers that we interviewed, to the editor and to the three anonymous reviewers and to all the colleagues who have provided feedbacks to this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2024.2318336.

References

- Adner, R. 2017. “Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable Construct for Strategy.” Journal of Management 43 (1): 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316678451.

- Alford, J., and S. Yates. 2014. “Mapping Public Value Processes.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 27 (4): 334–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-04-2013-0054.

- Alvesson, M., and K. Skoldberg. 2018. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. London: Sage Publications.

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2018. “Collaborative Platforms as a Governance Strategy.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 28 (1): 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mux030.

- Ansell, C., E. Sørensen, and J. Torfing. 2021. “The Covid-19 Pandemic as a Game Changer for Public Administration and Leadership? The Need for Robust Governance Responses to Turbulent Problems.” Public Management Review 23 (7): 949–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1820272.

- Bartelings, J. A., J. Goedee, J. Raab, and R. Bijl. 2017. “The Nature of Orchestrational Work.” Public Management Review 19 (3): 342–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1209233.

- Barzelay, M. 2019. Public Management as a Design-Oriented Professional Discipline. Cheltenham (UK): Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Boin, A., A. McConnell, and P. Hart 2020. “Leading in a Crisis: Strategic Crisis Leadership During the Covid-19 Pandemic.” ANZSOG (Australian and New Zealand School of Government. Accessed August 27, 2020. https://www.anzsog.edu.au/resource-library/research/strategic-crisis-leadership-during-the-Covid-19-pandemic.

- Bolden, R., A. Gulati, and G. Edwards. 2020. “Mobilizing Change in Public Services: Insights from a Systems Leadership Development Intervention.” International Journal of Public Administration 43 (1): 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1604748.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bryson, J. M., B. Barberg, B. C. Crosby, and M. Q. Patton. 2021. “Leading Social Transformations: Creating Public Value and Advancing the Common Good.” Journal of Change Management 21 (2): 180–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1917492.

- Bryson, J. M., B. C. Crosby, and L. Bloomberg. 2014. “Public Value Governance: Moving Beyond Traditional Public Administration and the New Public Management.” Public Administration Review 74 (4): 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12238.

- Chen, H., A. Mehra, S. Tasselli, and S. P. Borgatti. 2022. “Network Dynamics and Organizations: A Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Management 48 (6): 1602–1660. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063211063218.

- Corriere della Sera. 2020. “Gallera: “Dalla Protezione Civile 250mila mascherine… ditemi voi se gli infermieri possono…”.” Accessed March 27, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QqFNi14Ct74.

- Crosby, B. C., and J. M. Bryson. 2010. “Integrative Leadership and the Creation and Maintenance of Cross-Sector Collaborations.” The Leadership Quarterly 21 (2): 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.003.

- Cui, T., and K. Aulton. 2023. “Conceptualizing the Elements of Value in Public Services: Insights from Practitioners.” Public Management Review 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2226676.

- Dudau, A., R. Masou, A. Murdock, and P. Hunter. 2023. “Public Service Resilience Post-Covid: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Public Management Review 25 (4): 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2219690.

- Edvardsson, B., P. Skålén, and B. Tronvoll. 2012. “Service Systems as a Foundation for Resource Integration and Value Co-Creation.” In Special Issue–Toward a Better Understanding of the Role of Value in Markets and Marketing, 79–126. Vol. 9. Bingley (UK): Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” The Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–550. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557.

- Eriksson, E., T. Andersson, A. Hellström, C. Gadolin, and S. Lifvergren. 2020. “Collaborative Public Management: Coordinated Value Propositions Among Public Service Organizations.” Public Management Review 22 (6): 791–812. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1604793.

- Eriksson, E., C. Gadolin, T. Andersson, A. Hellström, and S. Lifvergren. 2022. “Value Propositions in Public Collaborations: Regaining Organizational Focus Through Value Configurations.” British Journal of Management 33 (4): 2070–2085. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12567.

- Eriksson, E., and A. Hellström. 2021. “Multi‐Actor Resource Integration: A Service Approach in Public Management.” British Journal of Management 32 (2): 456–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12414.

- Foss, N. J., J. Schmidt, and D. J. Teece. 2023. “Ecosystem Leadership as a Dynamic Capability.” Long Range Planning 56 (1): 102270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2022.102270.

- Hartley, J., J. Alford, O. Hughes, and S. Yates. 2015. “Public Value and Political Astuteness in the Work of Public Managers: The Art of the Possible.” Public Administration 93 (1): 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12125.

- Hartley, J., A. Sancino, M. Bennister, and S. L. Resodihardjo. 2019. “Leadership for Public Value: Political Astuteness as a Conceptual Link.” Public Administration 97 (2): 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12597.

- Kinder, T., F. Six, J. Stenvall, and A. Memon. 2022. “Governance-As-Legitimacy: Are Ecosystems Replacing Networks?” Public Management Review 24 (1): 8–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1786149.

- Kinder, T., and J. Stenvall. 2023. “A Critique Of Public Service Logic.” Public Management Review 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2182904.

- Kinder, T., J. Stenvall, F. Six, and A. Memon. 2021. “Relational Leadership in Collaborative Governance Ecosystems.” Public Management Review 23 (11): 1612–1639. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1879913.

- Kruyen, P. M., and M. van Genugten. 2017. “Creativity in Local Government: Definition and Determinants.” Public Administration 95 (3): 825–841. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12332.

- la Repubblica. 2020. “Coronavirus, Sala: Rilanciare il video Milano non si ferma? Forse è stato errore. E annuncia struttura per ospitare bambini con genitori ricoverati.” Accessed March 26, 2020. https://milano.repubblica.it/cronaca/2020/03/23/news/coronavirus_beppe_sala_milano_struttura_bambini_genitori_ricoverati_volontariato-252059676/.

- Levin, D. Z., J. Walter, and J. K. Murnighan. 2011. “Dormant Ties: The Value of Reconnecting.” Organization Science 22 (4): 923–939. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0576.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- McColl-Kennedy, J. R., S. L. Vargo, T. S. Dagger, J. C. Sweeney, and Y. V. Kasteren. 2012. “Health care customer value cocreation practice styles.” Journal of Service Research 15 (4): 370–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670512442806.

- Meijer, A. J., M. Lips, and K. Chen. 2019. “Open Governance: A New Paradigm for Understanding Urban Governance in an Information Age.” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 1:3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2019.00003.

- Milward, H. B., and K. G. Provan. 2006. A Manager’s Guide to Choosing and Using Collaborative Networks. Vol. 8. Washington, DC: IBM Center for the Business of Government.

- Moore, M. H.1995. Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Morse, R. S. 2010. “Integrative Public Leadership: Catalyzing Collaboration to Create Public Value.” The Leadership Quarterly 21 (2): 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.004.

- Nasi, G., and H. Choi. 2023. “Design strategies for Citizen Strategic Orientation.” Public Management Review 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2228316.

- Operti, E., Y. S. Lampronti, and S. V. Sgourev. 2020. “Hold Your Horses: Temporal Multiplexity and Conflict Moderation in the Palio di Siena (1743–2010).” Organization Science 31 (1): 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2019.1283.

- Osborne, S. P. 2018. “From Public Service-Dominant Logic to Public Service Logic: Are Public Service Organizations Capable of Co-Production and Value Co-Creation?” Public Management Review 20 (2): 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1350461.

- Osborne, S. P. 2020. Public Service Logic: Creating Value for Public Service Users, Citizens, and Society Through Public Service Delivery. London/New York: Routledge.

- Osborne, S. P., M. Cucciniello, G. Nasi, and K. Strokosch. 2021. “New Development: Strategic User Orientation in Public Services Delivery—The Missing Link in the Strategic Trinity?” Public Money & Management 41 (2): 172–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1758401.

- Osborne, S., M. G. H. Powell, T. Cui, and K. Strokosch. 2022. “Value Creation in the Public Service Ecosystem: An Integrative Framework.” Public Administration Review 82 (4): 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13474.

- Osborne, S. P., M. Powell, T. Cui, and K. Strokosch. 2021. “New Development: ‘Appreciate–Engage–Facilitate’—the Role of Public Managers in Value Creation in Public Service Ecosystems.” Public Money & Management 41 (8): 668–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2021.1916189.

- Osborne, S. P., Z. Radnor, and K. Strokosch. 2016. “Co-Production and the Co-Creation of Value in Public Services: A Suitable Case for Treatment?” Public Management Review 18 (5): 639–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2015.1111927.

- Ospina, S. M., and J. Dodge. 2005. “It’s About Time: Catching Method Up to Meaning—The Usefulness of Narrative Inquiry in Public Administration Research.” Public Administration Review 65 (2): 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00440.x.

- Ospina, S., and E. Foldy. 2010. “Building Bridges from the Margins: The Work of Leadership in Social Change Organizations.” The Leadership Quarterly 21 (2): 292–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.008.

- Perry, B. L., and B. A. Pescosolido. 2012. “Social Network Dynamics and Biographical Disruption: The Case of “First-timers” with Mental Illness.” American Journal of Sociology 118 (1): 134–175. https://doi.org/10.1086/666377.

- Peters, B. G. 2016. “Governance and the Media: Exploring the Linkages.” Policy & Politics 44 (1): 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557315X14446617187930.

- Petrescu, M. 2019. “From Marketing to Public Value: Towards a Theory of Public Service Ecosystems.” Public Management Review 21 (11): 1733–1752. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1619811.

- Pratt, M. G., S. Kaplan, and R. Whittington. 2020. “Editorial Essay: The Tumult Over Transparency: Decoupling Transparency from Replication in Establishing Trustworthy Qualitative Research.” Administrative Science Quarterly 65 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839219887663.

- Røhnebæk, M. T., V. François, N. Kiss, A. Peralta, L. Rubalcaba, K. Strokosch, and E. Y. Zhu. 2022. “Public Service Logic and the Creation of Value Propositions Through Framing.” Public Management Review 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2022.2095002.

- Sancino, A., C. Garavaglia, M. Sicilia, and A. Braga. 2020. “New Development: Covid-19 and Its Publics—Implications for Strategic Management and Democracy.” Public Money & Management 41 (5): 404–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1815380.

- Sancino, A., and A. Turrini. 2009. “The Managerial Work of Italian City Managers: An Empirical Analysis.” Local Government Studies 35 (4): 475–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930903003704.

- Skålén, P. 2022. “Public Services and Service Innovation: A Practice Theory View.” Nordic Journal of Innovation in the Public Sector 1 (1): 20–34. https://doi.org/10.18261/njips.1.1.2.

- Sklaveniti, C. 2020. “Moments That Connect: Turning Points and the Becoming of Leadership.” Human Relations 73 (4): 544–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719895812.

- Strokosch, K., and S. P. Osborne. 2020. “Co-Experience, Co-Production and Co-Governance: An Ecosystem Approach to the Analysis of Value Creation.” Policy & Politics 48 (3): 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557320X15857337955214.

- Strokosch, K., and S. P. Osborne. 2023. “Design of Services or Designing for Service? The Application of Design Methodology in Public Service Settings.” Policy & Politics 51 (2): 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557321X16750746455167.

- Sullivan, H., H. Dickinson, and H. Henderson. 2021. The Palgrave Handbook of the Public Servant. London: Palgrave.

- Trischler, J., M. Røhnebæk, B. Edvardsson, and B. Tronvoll. 2023. “Advancing Public Service Logic: Moving Towards an Ecosystemic Framework for Value Creation in the Public Service Context.” Public Management Review 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2229836.

- Trischler, J., and Westman J. Trischler. 2022. “Design for Experience – a Public Service Design Approach in the Age of Digitalization.” Public Management Review 24 (8): 1251–1270. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1899272.

- Uhl-Bien, M., and M. Arena. 2018. “Leadership for Organizational Adaptability: A Theoretical Synthesis and Integrative Framework.” The Leadership Quarterly 29 (1): 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.12.009.

- van der Wal, Z. 2017. The 21st Century Public Manager. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- van der Wal, Z. 2020. “Being a Public Manager in Times of Crisis the Art of Managing Stakeholders, Political Masters, and Collaborative Networks.” Public Administration Review 80 (5): 759–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13245.

- van Dorp, E. J., and P. Hart. 2019. “Navigating the Dichotomy: The Top Public Servant’s Craft.” Public Administration 97 (4): 877–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12600.

- van Gestel, N., E. Ferlie, and S. Grotenbreg. 2023. “A Public Value Strategy for Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming an Existing Organization?” British Journal of Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12742.

- Virtanen, P., and H. Jalonen. 2023. “Public Value Creation Mechanisms in the Context of Public Service Logic: An Integrated Conceptual Framework.” Public Management Review 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2268111.

- Wankhade, P. 2021. “New Development: A ‘Journey of Personal and Professional emotions’—Emergency Ambulance Professionals During Covid-19.” Public Money & Management 43 (5): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2021.2003101.