ABSTRACT

By studying organizational creations, this article documents the reform trajectory of a non-Western country from 1947 to 2018, using a comparative analytical framework for the operationalization of reform trends on an original dataset – PSAD. Pakistan has paralleled Western world in following the ideal-type reforms without entirely shifting to the new models. Context matters, but the type of government – civilian or military – has not made vivid difference. No one reform type was pushed away; instead, country moved beyond hierarchies and markets creating blends, staging the co-existence of NPM with hierarchies and networks at its 40th.

Introduction

The status of NPM at its 40th has garnered significant research and scholarly attention that calls for exploring its current state of the art. Hood and Peters already declared ‘middle age’ for NPM in 2004, Dunleavy et al. (Citation2005) announced the death of NPM, while (Drechsler and Kattel Citation2009; Pollitt Citation2003; De Vries Citation2010) counted on the reversal of NPM reforms in most countries, as they do not believe in complete death rather than existence in new forms. NPM has long been considered an ideal-type reform model propagating minimal role of state and market-type mechanisms, others being Weberian hierarchies and network-type management (whole of government or joined-up government among its other names).

Public sector is in constant state of flux (Drechsler and Kattel Citation2009), moving from one ideal-type reform model to the next one when the existing one does not seem to cure the ailments of the government. However, Aoki et al. (Citation2023) consider it erroneous to assume that, for instance, networks-type reforms came as solution to the problems caused by NPM. There could be multiple reasons for countries to move from one ideal type to the other one. Bouckaert (Citation2023) talked about moving ‘beyond’ or ‘away’ from existing reform models whilst moving beyond has a rather positive connotation where the foundations of existing model are maintained and moving away is a more negative push emphasizing on the pathologies of the existing system and calling for innovation.

The question of why and how organizational reform models evolve and decline has always been central for institutionalist (institutionalism) researchers working on organizations (Reiter and Klenk Citation2019). Meanwhile, the operationalization of ideal-type reform models has remained a critical issue (Aoki, Tay, and Rawat Citation2023) creating systematic difficulties for comparative research. Adding to this issue in organizational research is the explanation of what is a state organization, their number and types which diverge across national and international boundaries and political systems (Lægreid and Verhoest Citation2010; Verhoest et al. Citation2012).

This article while trying to address the systematic challenges in comparative research documents and tracks reform trends (hierarchies, markets and networks) by studying organizational creations over time, which allows to see convergence/divergence with international trends and the state of play for NPM in a non-Western country. Related exercises of mapping the trends in organizational creations and change have been done in the Western context by various scholars (NakrošNakrošIs and Budraitis Citation2012; Hajnal Citation2012; Lewis Citation2002; MacCarthaigh Citation2012; Citation2014; Rolland and Roness Citation2010, Citation2012; Sarapuu Citation2012) and one from China (East-Asia) by Ma and Christensen (Citation2018). Non-Western countries have not been given much research attention in this area except the few cases discussed briefly in the book by Verhoest et al. (Citation2012); other recent studies mentioned by Aoki et al. (Citation2023) more commonly study the effect of different reform models.

Salman (Citation2021) asserted on the need to develop discourse on public sector reforms from a comparative perspective, with more studies comparing reform trajectories of similar country contexts. Even across the countries outside the West and those still developing vary in their experiences while we get fewer accounts of them in the literature (McCourt Citation2008). Pakistan, located in South-Asia, being the first modern Muslim country, an over-developed state with a top-down, centralized structure (Alavi Citation1972; McCartney Citation2019), faced frequent governance challenges and experimented with various models of governance (Husain Citation2018). There has been absence of stable political institutions since its existence, with intermittent episodes of civil and military regimes (Salman Citation2021). Furthermore, the reliance on donor agencies from the West for the reforms and development opens the ways for bringing the western reform models to this side of the world. This, altogether, makes Pakistan one of the important and less studied cases among the non-Western and developing world.

Thus, this article documents and tracks a variety of creations in the period from 1947 to 2018 to explore the current state of NPM (beyond NPM or a push-away with a complete switch to networks) as an ideal-type reform model. These years are divided into eight periods, mainly based on major changes in the political government (both military and civilian). Drawing a parallel with Western databases, Norwegian (NSAD) and Irish state administration databases (ISAD) (MacCarthaigh Citation2012; Rolland and Roness Citation2010) that are replicable for most of the Western world, Pakistan State Administrative Database (PSAD) was developed for this research as a data source and includes information on 363 state organizations in Pakistan. To further aid the comparative literature, formal legal categories developed by Van Thiel (Citation2012) were used to classify the state organizations along the vertical dimension.

Retrospectively, this article makes three contributions: (1) developing an analytical framework that allows for the operationalization of administrative reform trends through the mapping of organizational creations; (2) testing this analytical framework on an original dataset that applies the notion of a ‘continuum’ of public sector organizations in the context of Pakistan; and (3) developing the reform discourse of a non-Western country using a comparative data set and operationalization developed for the West, paving the way for more comparative research from non-western parts of the world.

The article begins by reviewing the theoretical and conceptual choices for the empirical analysis. The database and data sources are discussed later on, setting the scene for the analysis and discussion of the results in the final section of the article.

Theoretical framework

The diffusion and adoption of international ideal-type reform models

Over the years, three main reform models have prevailed in the public sector around the world (Hammerschmid et al. Citation2016). These three models have served as ideal types that enable the interpretation of complex realities (Bouckaert & Halligan Citation2008). These ideal types continue to be the representations of modelled behaviour with a hinge of ‘pure’ flavour.

The first reform model was prevalent before the 1980s when Weberian hierarchies led the public sector management. Governments essentially preferred hierarchy-type mechanisms (HTM) for managing the state, with the dominance of rules in public administration (Hood Citation1991). Management remained bureaucratic, tightening up traditional controls (Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017) along with less number of new state units that were mostly fed and controlled by the state.

The second reform model emerged in the early 1980s, initially in the Anglo-Saxon states. The marketize characteristic is close to NPM as a ‘supermarket’ state model (Christensen and Laegreid Citation2011). The minimize characteristic hands over as many tasks as possible to the market and therefore is ‘hollowing out’ the state machine (Frederickson and Frederickson Citation2006). Marketize and minimize are combinable, fitting NPM, according to Bouckaert (Citation2023). The concept of structurally disaggregated public sector organization, usually called agencies in the literature, gained prominence, leading to an increase in the number and type of government organizations (Lægreid and Verhoest Citation2010), working at a distance from the government under a performance contract with the state (Moynihan Citation2006). NPM has ‘bewitched, bothered, and bewildered’ policymakers and public sector reformers since its emergence as the pre-eminent solution set for public sector performance problems in the 1980s (Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff Citation2015). However, not all problems could be solved by NPM-type ideal reforms; rather, some of the new problems were added by NPM around the world that did not exist earlier. Singh and Slack (Citation2022) also pointed to these issues mainly in the context of developing countries that NPM cannot be perceived as a silver bullet that can overcome overnight all inculcated Weberian bureaucratic weaknesses of the public sector (making public sector borrow the private sector practices for efficiency), built up over many years. Moreover, the dysfunctional autonomy resulted in a centrifugal movement of agencies (at a distance from the central government) alongside considerable transaction costs to set up all ultimately disconnected agencies with rising coordination issues (Bouckaert Citation2022).

So, post 2000, the third reform discourse appeared as another ideal type in the late 1990s, initially in trail-blazing NPM countries in the West with diverse names such as joined-up government, whole-government or post-NPM, with an increased focus on coordination (Christensen Citation2012), and steering capacity enhancement of the politico-administrative centre (Reiter and Klenk Citation2019). There is a broad agreement on the preference for network-type management (NTM) with vertical and horizontal coordination (Bouckaert, Peters, and Verhoest Citation2010) and less on creating new units.

The question of why and how these organizational reform models evolve and decline has always been central for institutionalist research on organizations (Reiter and Klenk Citation2019). New reform models usually evolve and diffuse when the existing models are in crisis (Drechsler and Kattel Citation2009). For instance, since years many researchers have declared NPM dead with the rising problems of coordination caused by it; however, put the death differently and argue that NPM is just not a viable option anymore for the public sector, at least not in its purest form. They argue that new reform models co-opt the positive elements of NPM with different foundations. So, the final shape for the new reform ideal type appears in a different form.

In open systems where organizations operate, these evolving ideal-type reforms get transferred from national to global level, from Western to non-Western countries around the world. Ideal-type reforms travel around the world as success lessons or bindings from funding agencies against the loans, usually based in the West. Drechsler (Citation2018) has also discussed the fixation with the models evolving from Western world, being legitimized as global best practices or ideal types, although the non-Western countries have different capacity and contextual settings. Even then, international donor agencies including IMF and World Bank mostly shaped externally supported reforms in all sectors in developing countries receiving international assistance (Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff Citation2015). Between 1987 and 1996, the World Bank supported downsizing programs in no fewer than 68 developing and transitional countries in the context of its ‘structural adjustment’ loans (McCourt Citation2008). Since the donors have a tendency to arrive in these countries with a pre-fabricated, ‘blue-print’ for public sector reform (Schacter Citation2000), it will be rather delayed compared to the West where it initiated and was institutionalized.

In retrospect, the variety in terms of the creation of state organizations also kept on evolving and ideal-type reform models made countries adopt certain policy decisions (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983) that were widely legitimized in the public sector at a certain point in time, usually arriving from the West. Thus, the following is hypothesized for a non-Western country (Pakistan);

H1:

The choices in the variety and pace of creating state organizations in Pakistan over the years were driven by three ideal-type reform models in the public sector travelling from the West.

Political-administrative systems are not in a state of inertia, but actually in a state of flux (Drechsler and Kattel Citation2009). Correspondingly, the shift from one reform model to another is taking place which in itself is not a smooth process where one idea is entirely replaced by another. Instead, the shift of institutions and underlying ideas involves struggles between or among contending schools with another argument that the ideas enshrined in the ‘new’ concept are not always new in the strict sense (Reiter and Klenk Citation2019). Administrative reforms often happen in cycles or waves (Christensen and Lægreid Citation2012) or they make zigzag trajectories (Bouckaert Citation2022). More often, same communication (say of reform ideal types) is interpreted, filtered and received differently by different individuals and organizations, that reflects their different contexts, sensitivities and perspectives (Dolowitz Citation2017), especially when the new ideal-type reform model arrives.

Bouckaert (Citation2023) has discussed the concept of moving ‘beyond’ or ‘away, where the ‘beyond Weber’ (post HTM) is not just about shifting completely to another ideal-type reform paradigm. Moving beyond has a rather positive connotation where the foundations of existing model stay while moving away is a more negative push emphasizing on the pathologies of the existing system and calling for innovation (Rhodes Citation1997). The ‘beyond Weber’ discussion is rather relevant for the debate of how well Weber ‘travels’ to non-Western, and non- or less developed democratic systems (Bouckaert Citation2023). In the Chinese context ‘bureau-franchising’ is considered as ‘beyond Weber’ model where market and hierarchy are combined (Ang Citation2017), which technically applies to the context of Pakistan where the rationale and process might be different; however, blend of hierarchies and markets is frequently used (Zahra Citation2020).

This could also be applied to NPM (market-type management); a shift to networks might not mean a push away from NPM; rather, it could be possibly ‘beyond NPM’ where NPM travels with a prominent blend of networks. Whilst there are incentives to maintain the core of the NPM package, with some tinkering at the margins, espousing that what is proposed has moved beyond the old NPM (Lodge and Gill Citation2011). Furthermore, networks (NTM) do not approve the ‘total negation’ of NPM ideas. For example, agencification and the creation of semi-public agencies are not fully rejected; however, the focus on better coordination is considered necessary (Reiter and Klenk Citation2019). They describe it as a process of layering, adding new instruments and instruments without completely removing the existing ones. In reality, however, there are more hybrids and blends combining into (hybrid) ideal types often keeping the bits of ‘pure’ flavour. Thus, we hypothesize;

H2:

‘Pakistan has been moving beyond hierarchies, markets and networks (ideal types) in terms of the creation of state organizations, rather than moving away from them’.

Data and methods

Variety in state organizations: moving on the continuum

The mapping of the creation of state organizations must consider the criteria for inclusion and exclusion (Rolland and Roness Citation2010). However, this is not straightforward, since there is no single criterion to classify heterogeneous state organizations across the globe. A number of researchers have grappled with the difficulty of labelling state organizations because of their diverse structures and functions that do not fit under a single rubric (Schick Citation2009). Even similar categories of organizations mean different things in different countries and contexts. Scott (Citation2008) developed different criteria to categorize state organizations, including ownership, legal form, funding, function and power and governance levels. The legal form or vertical dimension concerns the way the state has designed the structural disaggregation among ministries and state units at different hierarchical levels. Different categories of state organizations are distinguished on the basis of how close they are to the central government and its authorities (Rolland and Roness Citation2010). Although classifying these organizations by formal autonomy has potential drawbacks (Bach and Jann Citation2010), the formal legal instrument does explain the variety in the creation of these organizations and helps to position them on a continuum of formal autonomy and distance from the ministries.

For classifying the organizations according to legal statue, the categorization by Van Thiel (Citation2012) which was previously used by scholars from 30 countries to elaborate the findings in their respective countries is used for this article. A list of five categories was developed by Van Thiel (Citation2012): units or directories of the state or federal government are type (0), organizations without legal independence-semi-autonomous are type (1), those with legal independence are type (2), private or private law-based bodies or those anchored on public law created by the government are (3), local bodies/organizations are type (4), and any other organizations not fitting in the above categories are type (5). These legal categories have varying levels of control from the ministries and government- ranging from direct to indirect. The spectrum of the variety in government organizations across countries is discernible, and almost all five of the different legal types of organizations exist.

In Pakistan, there are a number of labels for state organizations used by ministries and in different government booklets. Furthermore, state organizations working under the ministries are created using a variety of legal instruments, including acts of parliament, presidential ordinances, martial law ordinances, resolutions, gazette notifications, cabinet meetings or, in rare cases, other instruments. All the organizations created under an act or ordinance have independent legal existence and are answerable to the courts if anything happens or goes wrong (type 2 and 3). Organizations that do not have their own act or ordinance and are created by another legal instrument mentioned above are not responsible before the court if anything happens (type 0 and 1); instead, the appropriate ministry will have to deal with the matter on behalf of the organization.

Jadoon, Jabeen, and Rizwan (Citation2012) categorized Pakistani agencies into attached departments, semi-autonomous bodies and autonomous bodies. (Companies and foundations were not included in their list.)Footnote1 We, however, have categorized the state organizations working under federal ministries based on their legal instruments into the four categories using Van Thiel’s categorizations (type 0 to type 3) (). The categories 4 and 5 of Van Thiel are not used as the focus is only on federal organizations in the article. Using a standard categorization adds to the systematic research on organizational units and change.

Operationalization of reform models

The administrative reform models are operationalized for explaining organizational creations over the years. In different reform periods, governments have used different mechanisms to create state organizations that tend to affect the variety of organizations in terms of their legal status. The creation of state organizations of type 0 and 1 () is linked more with the use of hierarchy-type management mechanisms (HTM) by the government. The nature and intensity of hierarchies can vary from tight to loose in organizations, depending on the control from the state. The closer the organization is to the central government legal type 0 and 1, the tighter the hierarchical mechanisms that are used. Creating more legally autonomous organizations (type 2) at a distance from the state is treated as a hierarchy-type instrument by (Bouckaert, Guy Peters, and Verhoest Citation2010), but with less hierarchical intensity or loose hierarchy, we treat it as a combination/blend of HTM and MTM (beyond Weber/HTM). Legally autonomous organizations with loose hierarchies are also influenced by market-type reforms since the idea is to give state organizations more autonomy and make them modern and managerial (Pollit et al. Citation2001).

The creation of new public sector companies (type 3) and competition in the public sector is a market-type instrument (MTM) with a loose hierarchy since state control over state-owned companies stays in a certain form. Ending state monopolies and minimizing the role of government by increasing the number of state-owned companies is a prominent part of NPM. For this study, the creation of companies is examined under MTM.

With the third reform discourse, linked to joined-up government, more network-type mechanisms (NTM) are used. Fewer organizations are created more type 0 and 1, and existing units are involved to coordinate and work efficiently as a network.

The Pakistan state administration database

The PSAD is the first systematic longitudinal database for structural anatomy of the state in a developing country. It was developed during a three-year period (2016–18) and includes data on ministries, divisions and state organizations. The code book for the PSAD was adapted from the Norwegian (Rolland and Roness Citation2010) and Irish state administration databases (MacCarthaigh Citation2012) (NSAD and ISAD) to make the database (PSAD) more relevant for comparative research; however, codes were carefully adjusted and reviewed according to the local context; some categories were added that were prominent in the lifecycle of a Pakistani organization but not existing in NSAD and ISAD. The creation refers to the ‘birth’ category which means an entirely new organization and not those that are restructured. The purpose of the PSAD is to provide systematized information on the structure, procedures and changes in the state administration of Pakistan over time.

The PSAD covers 363 state units () functioning under federal ministries at different times. Only organizations for which there was insufficient information in the data sources were excluded from the database, and most often belonged to defence, navy, intelligence and special communications areas.

Government websites, yearbooks obtained from ministry offices and websites, government documents and verifications via telephone were combined to develop the database since the information was not well documented or updated in one single place. The reports published by the National Commission on Government Reforms (NCGR) in 2008, an updated report in 2016, and yet another revised version in the same year due to the continuous reshuffling at the federal level from 2008 onwards, proved to be important sources for data verification. The 2008 list was used to include the organizations that were functional at the federal level and were later transferred to the provincial government after the 18th Amendment was added to the constitution in 2008. The latest lists of organizations and their parent ministries were taken from the ministry websites and the Institutional Reforms Cell (IRC) reports focussed on reorganizing federal organizations among other areas. The total number continues to vary but usually revolves around 441 (Institutional Reforms Cell Citation2018). Even the yearbooks for most of the ministries were not available on the websites or accessible for researchers. The National Documentation Center (NDC) had a collection of ministry yearbooks, but government rules do not allow copies to be made or taken outside the NDC, which made the compilation of the database challenging. This means that we might lose sight of some creations that died before 2008; however, with the results of (Zahra Citation2020), it was obvious that there were bare minimum deaths of organizations in a period of over 70 years.

To ensure high consistency, the data gathering, recording and analysis were performed by the researchers. The time period from 1947 to 2018 was divided into eight smaller time periods in , and the time period divisions were made based on the type of government in power. The significance of the type of government in power cannot be ignored, as the government initiates and implements the reforms. Moreover, the overall architecture of the state and its units is the result of conscious strategies of political leaders (Sarapuu Citation2012). The structure and number of state units undergo changes with the changing government as reform is also a political process where political and administrative logics are balanced or rebalanced (Christensen and Lægreid Citation2012; Pierre Citation2004).

Table 2. Time periods for analysis.

The categorization of the periods was complex since state units were categorized according to their creation year. The cut-off year for each period was decided on the major change of political government, and most periods aligned with about one decade. Except for the last two terms, where the periods are each five years and each cut-off year is the beginning year of the next period, the creations are carefully placed according to the ruling regime. For instance, any unit that was created in a year that is both a closing and an opening year (included in two periods) was coded in the earlier period. It is assumed that no new government can create new organizations in the first few months of its tenure, and even if it can, rationally, such a creation would be the result of the previous government’s policies.

PSAD includes information on the year of creation, parent ministry and division, legal status, instrument of creation, policy field, task and changes in structure over the years for each state organization. It is used to map the variety in the creation of state units from 1947 to 2018 with plots and tables for data visualization and analysis. The categories related to the creation, legal instrument, time period, policy field and task were taken for the analysis. The data were used to run the empirical analysis and to longitudinally map the trends over the years.

Results

Creation of state organizations: the Pakistani case

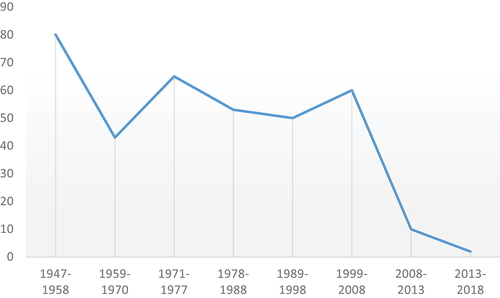

By looking at the plot of creations of different types of organizations from 1947 to 2018, the fluctuating trend seems obvious in . There is constant flux in the number of creations, with constant highs and lows. The last two periods, however, show a clear decline in the number of creations.

demonstrates the difference in the variety of creations over the eight time periods according to their legal categories.

Table 3. Creation of state organizations per legal status and time period.

The period from 1947 to 1958 was the beginning of a new country, and accordingly, it had a high number of creations. Meanwhile, all of the organizations that continued to function after the sub-continent partition in 1947 were included in this time period. This explains the increased number of organizations in all categories with high proportions of attached departments (type 0 and 1). This time period was marked with economic struggle, and income was mainly spent on development; some public sector companies and autonomous bodies were established. However, the number of foundations remained low, and this did not change in almost any period.

It appears from that the creation of type 0 and 1 increased until 1988, along with a steady increase in the creation of type 2 and 3. It is interesting to note that an increased number of type 2 organizations were created in the period of 1971–1977, when the government had a major nationalizing agenda and was strengthening the centre using both tight and loose hierarchies. The higher number of creations can be attributed to the fact that Z.A. Bhutto worked as Chief Martial Law Administrator in his early years and was able to implement his economic reform agenda effortlessly.

Figure 3. Total number of creations of state organizations by legal status.

Looking at the number of corporations and companies (type 3), the marked increase from 1970–1977 can be entirely attributed to the nationalization policies of Bhutto that does not correspond with the market-type mechanism; in this case, privately owned companies were turned into public owned. Corporatization formally began in Pakistan during the Zia-ul-Haq period (military-led) with the company ordinance of 1986, which brought Western-style corporate practices to the country. An evident increase in companies is visible during the civilian government of Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif; while their government was focused on privatization, a number of public companies were also created. The focus was on ending government monopolies (minimizing the role of state: NPM); meanwhile, the creation of a privatization commission in 1991 was a major achievement. According to the Privatization Commission (2015), the government initiated the privatization programme and offered 108 public state enterprise slots, out of which 66 were privatized during the period of 1988–1998, all within less than 18 months of each other. In the meantime, WAPDA (a public sector company) was unbundled into a number of distribution companies, and other public sector companies were also established.

The number of autonomous bodies (type 2) started to increase and reached its highest point in the period of 1999–2008 which was again a martial law-led government. A total of 26 autonomous bodies were created in that period, which is the maximum number among all the periods, after which the number decreased. The period of 1999–2008 marked the creation of regulatory bodies, leading to increase in type 2 units; regulatory units were created to improve coordination (networks) and control issues indicating hierarchies, markets and networks all together. The martial law period of General Musharraf exhibited the highest proportion of overall type 2 and 3 organization creation, as economic recovery was that government’s professed target.

The post-2008 period marks a visible decrease in the number of public sector companies, as the main focus of the government during this time was more on decentralization, moving towards provincial government and away from the federal level, and less creations. Some of the organizations created in the post-2013 period of the PML-N rule were attached departments. The decline in the last decade with more tight hierarchical creations indicates third reform discourse which focuses on coordination.

Another way to explain how reform discourses were adopted in the country is to look at the proportion of state organizations according to their present legal status, since state organizations undergo changes in their legal status during their life cycle. In the PSAD, the legal status of the organization at the time of creation was recorded, and with other organizational change codes, ‘new form of legal affiliation or legal instrument’ was also added, which is similar to what occurred with the NSAD and ISAD. A variable was created that recorded the present legal status of the organization (the legal status at the time of the database development). Analysis shows that over the years, governments continued to use different reform mechanisms, not always by creating state organizations, but rather by frequently changing their legal statuses.

shows the inclination of the government towards restructuring rather than entirely terminating or creating new entities. The database recorded 177 instances where units underwent a change in legal status in the period of over 70 years. Most of the changes in legal status recorded in the last period were related to companies and corporations since Companies Ordinance 1984 was changed to the Companies Act 2018, ultimately affecting almost all the functioning companies and corporations.

Table 4. Event of change in legal status.

Discussion

The patterns in the creation of units

The wide variety of state organizations under study, classified along legal categories, made it possible to track the reform trends over time in light of the proposed hypothesis in the earlier section.

a. The choices in the variety and pace of creating state organizations in Pakistan over the years were driven by three ideal-type reform models in the public sector travelling from the West.

The idea of creating state organizations is not new, and countries around the world continue experimented with different types of organizations even before the ideal reform types were institutionalized. However, mostly the trends prominently shift with new ideal types travelling from developed to the developing countries.

In Pakistan, we saw that the variety in the creation of state organizations over the years was prominently driven by the three reform types. These ideal types enable the interpretation of real time reform process in Pakistan. Governments in Pakistan did not entirely shift from tightened hierarchies with type 0 and 1 organizations working closer to the state to the loose hierarchies with more type 2 and 3 working at a distance from the state. However, there was a decrease in the creation of type 0 and 1 organization in late 1980’s and type 2 and 3 were created comparatively more in late 1999. Although an increase in state-owned companies was visible in the 1970s, long before the market-type reforms (NPM), the companies were nationalized entities, unlike the state companies created after the Corporate Sector Act of 1986. Meanwhile, the IMF structural adjustment program already arrived in 1980’s, bringing in the flavours of NPM-type reforms, to treat the ailments of the system. Sharif’s government’s economic strategy laid on a new agenda for industrialization public–private partnerships to promote common objectives (Blood Citation1994) and on liberalizing, deregulating and privatization (Husain Citation2018) which is a trend towards market-type mechanisms. Perhaps, all while counting on NPM as a silver bullet, hoping it to solve the governance issues of Pakistan, similar to what other developing countries counted (Singh and Slack Citation2022). Between 1991 and 2008, proceeds of PKR 476 billion were raised from 167 privatization transactions (Ministry of Privatization 2016–17).

The post-NPM reforms, after 2000, invigorated coordination and decreased number of creations in the public sector (James Citation2004) and the use of tight hierarchies (Bouckaert, Peters, and Verhoest Citation2010). In Pakistan, the number of creations substantially reduced after 2008 as major areas were decentralized towards provincial governments, while strong hierarchical control was maintained at the central level indicating the importance of local politics (McCourt Citation2008). For instance, smaller number of creations at federal level did not necessarily mean a pause in creations at the provincial level too.

The hierarchies in these years remained tight in Pakistan, pointing towards post-NPM trend. Most organizations created in those years were close to the government and maintained under tight hierarchy mechanisms, verifying the analysis of (Almeida Citation2017), according to whom major projects were facilitated or created by the government, belonging to regulation, public authority and policy formulation arenas, along with a few companies. This puts us in agreement with Lodge and Gill (Citation2011) that even after networks appeared as an ideal type, there was enough incentive for countries to maintain the core of the NPM package.

In terms of variety, Pakistan experimented with all the three ideal-type reform models that made different governments in Pakistan to follow certain patterns in the creation of organizations, usually as a result of policy transfer that happens around the world (Dolowitz Citation2017; Dolowitz and Marsh Citation2012). However, if we look closely, the Western models arrived usually around the same time while the other parts of the world were experimenting with them, indicating the fixation with the Western models (Drechsler Citation2018). Local realities shaped the variety and pace more in multiple ways, with the impact of foreign funded reform packages (McCourt Citation2008), often matching the timing with the West. So, the whole idea of convergence in terms of timings, pace and reasons and administrative structures has been exaggerated (Christensen and Lægreid Citation2012; Pollitt Citation2001; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017; Premfors Citation1998; Schick Citation2009; Smullen Citation2004; Van Thiel Citation2012) as agreed by many from the West.

Moreover, the journey of Pakistan did not hint towards the death of any one reform ideal type, before the birth of the next ideal type. In fact, there is agreement with that NPM on its own is not considered the most viable option without burying it entirely.

These ideal reform types enabled our understanding of how Pakistan used all the reform discourses in different time periods and in different forms, combining both local realities and internationally acclaimed recipes of success. The pace did not drastically varied from the West as evident from the findings of (Zahra and Bach Citation2021), although local contextual factors mattered with no one explanation for the complete period under study even the regime type. With the data, we have enough evidence to support H1 partially, while the variety in creation of organizations was affected by the ideal reform models; however, the pace is more internal matter and is explainable by the local context which is not something very different from the other parts of the world.

b: ’Pakistan has been moving beyond hierarchies, markets, and networks (ideal types) in terms of the creation of state organizations, rather than moving away from them’.

The political and administrative system in Pakistan has remained in flux similar to countries around the world (Drechsler and Kattel Citation2009). While experiments with ideal reform ideas continued, no reform model completely replace the other one (Reiter and Klenk Citation2019). In fact, the elements of these reform types have been used in combination in Pakistan.

Post 1980’s, type 0 and 1 organizations were still created although the number decreased quite a bit in the civilian government of 1989. Military government known to maintain tighter controls did not show a constant pattern in terms of choices in creation, for the Martial law regime of Zia Ul Haq (1978–88), type 0 and 1 was preferred, while also creating type 2 and 3. This shows that Weberian foundations stayed while building on the elements of markets, sometimes in combination with hierarchies and sometimes on its own. Meanwhile, the contextual realities continued to affect the creations, as the civilian government starting in 1989 had its own industrialist background and priorities, which led to the creation of additional public companies. The increased number of corporations and companies in the post-1999 period of General Musharraf was equated with Musharraf’s plan to have the military involved in core business areas; military people were more involved in businesses than ever (Husain Citation2018; Niaz Citation2010).

While NPM and post-NPM were brought in, their intensity varied and did not dramatically increase in certain years. The move to networks did not lead to a complete push away from NPM, with around 23 type 3 organizations until 2008. Moreover, in 2000’s, regulatory bodies were created that were aimed at better coordination bringing in the flavour of H, M and N together. Less creation at federal level from 2008 onwards is also attributed to 18th amendment in the Constitution, when most of the functional areas were devolved to the provinces, and not just due to the prevailing reform ideal type.

The findings also show similarity to the Chinese context (another non-western case), where markets and hierarchies are used together in terms of organizational creations (type 2). The study adds to Reiter and Klenk (Citation2019) who see reform as a process of layering while maintaining some bits of the ‘pure’ flavour. It indicates that even in the non-western context like Pakistan, where these reform ideal types are not born, they do not completely shift to the ideal type rather they bring these celebrated ideal types and use them mostly to add layers or flavours. The core mostly belongs to Weberian hierarchies (Zahra Citation2020), as the main bit which is not affected by the type of government (civilian or military). The data support H2 as Pakistan has mostly moved beyond the three ideal types without completely leaving one behind and created blends that did meet the local requirements at that particular time.

Conclusions, limitations and future directions

While the literature is arguing the death of NPM and proposing new ideal reform models like Neo-Weberian State and others in the West, this article tracked and documented the discourse of a non-Western country by operationalizing reforms into three ideal types (hierarchies, markets and networks) for studying organizational creations using the original dataset on Pakistani organizations (PSAD) categorizing them in four different legal categories (type 0, 1, 2 and 3).

Public sector around the world stays in the state of flux, while the contextual variations persist. A non-Western country with its colonial background, hierarchical structures, political instability and periods of military role continued to experiment with the ideal-type reform models that were initiated in the West. However, the timing was not significantly different from the West and the country did try to bring in the flavour of institutionalized reform models without losing its original or base flavour. Putting it in the cake connotation, the new layers of flavours were added to the existing base which often leads to blending of flavours in the layers. However, no one existing layer was completely removed before adding a new one, confirming the moving beyond than away from earlier reform models interpretation. A variety of state organizations have been created over the years in Pakistan, and there seems to be no one set of explanation for it. Moreover, governments do not always create new organizations to align with the ideal reform models; rather, they chose to restructure by changing the legal status of the existing organizations.

Even the type of government (civilian/military) could not explain any specific variation.

Our findings do not suggest the death of NPM or Weberian hierarchies or network-type models, rather hint towards the co-existence of ideal types, keeping what is good of each and what suits the context. NPM at 40 is still alive although existing in various forms while blending in with other idea types. Our findings using a comparable operationalization of reforms and state administration database open new avenues for comparative research from non-Western countries.

We understand that although Pakistan is a developing, non-Western country, the findings cannot be generalized to every non-Western country since every country has their own capacities and constraints, but it does bring in the evidence from a South Asian country with data and method fairly comparable across the Western and non-Western world. Moreover, PSAD data cover 363 organizations out of the total number (441). Future research could further update the PSAD dataset.

Furthermore, in the recent five years post-2018, political instability has been in question in Pakistan which led to two major government changes and then the caretaker set-up. These changes certainly had meaning for the organizations, their creations or restructuring with each set up trying to prove their efficiency while battling with stability. This could also be further explored in the future research if it has major implications for the use of ideal-type reform models and mainly NPM.

This mapping of reform models and analysis is of practical concern for policy makers. PSAD can further facilitate reform mapping in areas of organizational studies that go beyond creations. Organizations are one of the most important organs of the state and enable the effective implementation of government policies. Their creation and change of legal status have wide economic and managerial implications that go beyond learning policy lessons from abroad. New organizations need manpower and infrastructure and raise new coordination issues across and within ministries while adding to the cost. Policy makers need to comprehend the role and potential of such decisions for effective results and better functioning of the state.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We have combined the semi-autonomous and attached departments in one category, the categorization stays in line with the work of (Jadoon, Jabeen, and Rizwan Citation2012).

References

- Alavi, H. 1972. “The State in Post-Colonial Societies: Pakistan and Bangladesh.” New Left Review 74:59–81.

- Almeida, Cyril. 2017. “The Revenge of the State.” Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1308454.

- Ang, Y. Y. 2017. “Beyond Weber: Conceptualizing an Alternative Ideal Type of Bureaucracy in Developing Contexts.” Regulation & Governance 11:282–298.

- Aoki, Naomi, Melvin Tay, and Stuti Rawat. 2023. “Whole-Of-Government and Joined-Up Government: A Systematic Literature Review.” Public Administration. Early view. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12949.

- Bach, Tobias, and Werner Jann. 2010. “Animals in the Administrative Zoo: Organizational Change and Agency Autonomy in Germany.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 76 (3): 443–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852310372448.

- Blood, Peter. 1994. Pakistan: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. http://countrystudies.us/pakistan/.

- Bouckaert, G., B. G. Peters, and Koen Verhoest. 2010. The Coordination of Public Sector Organizations: Shifting Patterns of Public Management. New York, US: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bouckaert, Geert. 2022. “From NPM to NWS in Europe.” Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences (SI) Special Is: 22–31: 22–31. https://doi.org/10.24193/tras.SI2022.2.

- Bouckaert, Geert. 2023. “The Neo-Weberian State: From Ideal Type Model to Reality?” Max Weber Studies 23 (1): 13–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/max.2023.0002.

- Bouckaert, Geert, B. Guy Peters, and Koen Verhoest. 2010. The Coordination of Public Sector Organizations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230275256

- Bouckaert, G., and J. Halligan. 2008. “Comparing performance across public sectors.” In Performance information in the public sector: How it is used, 72–93. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Brinkerhoff, Derick. W, and Jennifer. M Brinkerhoff. 2015. “Public Sector Management Reform in Developing Countries: Perspectives Beyond NPM Orthodoxy.” Public Administration and Development 35 (4): 222–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1739.

- Christensen, Tom. 2012. “Global Ideas and Modern Public Sector Reforms: A Theoretical Elaboration and Empirical Discussion of a Neoinstitutional Theory.” The American Review of Public Administration 42 (6): 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074012452113.

- Christensen, Tom, and Per Lægreid. 2012. “Competing Principles of Agency Organization - the Reorganization of a Reform.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 78 (4): 579–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852312455306.

- Christensen, T., and P. Lægreid. 2011. “Complexity and Hybrid Public Administration—Theoretical and Empirical Challenge.” Public Organization Review 11:407–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-010-0141-4.

- DiMaggio, Paulo J., and Walter W. Powell. 1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review 48 (2): 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101.

- Dolowitz, David P. 2017. “TRANSFER and LEARNING: One Coin Two Elements.” Novos Estudos CEBRAP 36 (1): 35–58. https://doi.org/10.25091/S0101-3300201700010002.

- Dolowitz, David P, and David Marsh. 2012. “Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy-Making.” Governance-An International Journal of Policy Administration and Institutions 13 (1): 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00121.

- Drechsler, Wolfgang. 2018. “Beyond the Western Paradigm: Confucian Public Administration.” In Public Policy in the ‘Asian Century’, edited by Sara Bice, Avery Poole, and Helen Sullivan, 19–40. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-60252-7_2.

- Drechsler, Wolfgang, and Rainer Kattel. 2009. “Towards the Neo-Weberian State? Perhaps, but Certainly Adieu, NPM!” The NISPAcee Journal of Public Administration and Policy 1 (2): 95–100.

- Dunleavy, Patrick, Helen Margetts, Simon Bastow, and Jane Tinkler. 2005. “New Public Management Is Dead-Long Live Digital-Era Governance.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 16 (3): 467–494. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui057.

- Frederickson, D. G., and H. G. Frederickson. 2006. Measuring the Performance of the Hollow State. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-010-0141-4.

- Hajnal, György. 2012. “Studying Dynamics of Government Agencies: Conceptual and Methodological Results of a Hungarian Organizational Mapping Exercise.” International Journal of Public Administration 35 (12): 832–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2012.715564.

- Hammerschmid, G., S. Van de Walle, R. Andrews, and P. Bezes. 2016. “Public Administration Reforms in Europe.” In Public Administration Reforms in Europe: The View from the Top, 1–10. Massachusetts, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Hood, Christopher. 1991. “A Public Management for All Seasons?” Public Administration 69 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x.

- Husain, Ishrat. 2018. Governing the Ungovernable: Institutional Reforms for Democratic Governance. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

- Institutional Reforms Cell. 2018. ‘Institutional Reforms in the Federal Government’. Volume I. Islamabad: Prime Minister’s Office Government of Pakistan.

- Jadoon, Muhammad Zafar Iqbal, Nasira Jabeen, and Aisha Rizwan. 2012. Pakistan, Edited by Koen Verhoest, Sandra Va Thiel, Geert Bouckaert, and Per Laegreid. England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- James, Oliver. 2004. “Executive Agencies and Joined Up Government in the UK.” In Unbundled Government: A Critical Analysis of the Global Trend to Agencies, Quangos and Contractualisation, edited by Christopher Pollitt and Colin Talbot, 75–93. New York, US: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lægreid, Per, and Koen Verhoest. 2010. “Reforming Public Sector Organizations.” In Governance of Public Sector Organizations: Proliferation, Autonomy & Performance, edited by Per Lægreid and Koen Verhoest, 1–21. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lewis, David E. 2002. “The Politics of Agency Termination: Confronting the Myth of Agency Immortality.” The Journal of Politics 64 (1): 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00119.

- Lodge, Martin, and Derek Gill. 2011. “Toward a New Era of Administrative Reform? The Myth of Post-NPM in New Zealand.” Governance-An International Journal of Policy Administration and Institutions 24 (1): 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2010.01508.x.

- Ma, Liang, and Tom Christensen. 2018. “Mapping the Evolution of the Central Government Apparatus in China.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 86 (1): 80–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852317749025.

- MacCarthaigh, Muiris. 2012. “Mapping and Understanding Organizational Change: Ireland 1922-2010.” International Journal of Public Administration 35 (12): 795–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2012.715558.

- Maccarthaigh, Muiris. 2014. “Agency Termination in Ireland: Culls and Bonfires, or Life After Death?” Public Administration 92 (4): 1017–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12093.

- McCartney, Mathew. 2019. “In a Desperate State: The Social Sciences and the Overdeveloped State in Pakistan, 1950 to 1983.” In New Perspectives on Pakistan’s Political Economy: State, Class and Social Change, edited by Matthew McCartney and S.Akbar Zaidi, 25–56. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- McCourt, Willy. 2008. “Public Management in Developing Countries.” Public Management Review 10 (4): 467–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030802263897.

- Moynihan, Donald P. 2006. “Ambiguity in Policy Lessons: The Agencification Experience.” Public Administration 84 (4): 1029–1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00625.x.

- NakrošNakrošIs, Vitalis, and Mantas Budraitis. 2012. “Longitudinal Change in Lithuanian Agencies: 1990-2010.” International Journal of Public Administration 35 (12): 820–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2012.715566.

- Niaz, Ilhan. 2010. The Culture of Power and Governance of Pakistan. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

- Pierre, Jon. 2004. ‘Sweden: Central Agencies’. In Unbundled Government: A Critical Analysis of the Global Trend to Agencies, Quangos and Contractualisation, edited by Christopher Pollitt, 203–214. New York, US: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Pollit, Christopher, Karen Bathgate, Janice Caulfield, Amanda Smullen, and Colin Talbot. 2001. “Agency Fever? Analysis of an International Policy Fashion.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 3 (3): 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980108412663.

- Pollitt, Christopher. 2001. “Clarifying Convergence: Striking Similarities and Durable Differences in Public Management Reform.” Public Management Review 3 (4): 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616670110071847.

- Pollitt, Christopher. 2003. The Essential Public Manager: Public Policy and Management. UK: Open University Press McGraw-Hill Education.

- Pollitt, Christopher, and Geert Bouckaert. 2017. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis—New Public Management, Governance, and the Neo-Weberian State. Oxford University Press.

- Premfors, Rune. 1998. “Reshaping the Democratic State: Swedish Experiences in a Comparative Perspective.” Public Administration 76 (1): 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00094.

- Reiter, Renate, and Tanja Klenk. 2019. “The Manifold Meanings Of’post-New Public Management’- a Systematic Literature Review.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 85 (1): 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318759736.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. 1997. “Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability”. Open University Press. Buckingham.

- Rolland, Vidar W, and Paul G Roness. 2010. “Mapping Organizational Units in the State: Challenges and Classifications Mapping Organizational Units in the State: Challenges and Classifications.” International Journal of Public Administration 33 (10): 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2010.497321.

- Rolland, Vidar W., and Paul G. Roness. 2012. “Foundings and Terminations: Organizational Change in the Norwegian State Administration 1947-2011.” International Journal of Public Administration 35 (12): 783–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2012.715562.

- Salman, Yaamina. 2021. “Public Management Reforms in Pakistan.” Public Management Review 23 (12): 1725–1735. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1850084.

- Sarapuu, Külli. 2012. “Administrative Structure in Times of Changes: The Development of Estonian Ministries and Government Agencies 1990-2010.” International Journal of Public Administration 35 (12): 808–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2012.715561.

- Schacter, Mark. 2000. “Public Sector Reform in Developing Countries Issues.” Policy Branch Canadian International Development Agency.

- Schick, Allen. 2009. “Agencies in Search of Principles.” OECD Journal on Budgeting 2 (1): 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1787/budget-v2-art2-en.

- Scott, Colin. 2008. “Understanding Variety in Public Agencies”. UCD Geary Institute Discussion Paper Series; WP42 008. Dublin.

- Singh, Gurmeet, and Neale J Slack. 2022. “New Public Management and Customer Perceptions of Service Quality – A Mixed-Methods Study.” International Journal of Public Administration 25 (2): 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2020.1839494.

- Smullen, Amanda. 2004. ‘Netherlands: Interpretations of Agency’. In Unbundled Government: A Critical Analysis of the Global Trend to Agencies, Quangos and Contractualisation, edited by Christopher Pollitt and Colin Talbot, 184–202. New York, US: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Van Thiel, Sandra. 2012. “Comparing Agencies Across Countries.” In Government Agencies: Practices and Lessons from 30 Countries, edited by Koen Verhoest, Sandra Van Thiel, Geert Bouckaert, and Per Laegreid, 18–26. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Verhoest, Koen, Sandra Van Thiel, Geert Bouckaert, and Per Laegreid. 2012. Government Agencies: Practices and Lessons from 30 Countries, Edited by Koen Verhoest, Sandra Van Thiel, Geert Bouckaert, and Per Laegreid. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vries, Jouke de. 2010. “Is New Public Management Really Dead?” OECD Journal on Budgeting 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.1787/budget-10-5km8xx3mp60n.

- Zahra, Abiha. 2020. Structural Reforms and Performance Management Systems: An Exploratory Analysis of State Organizations in Pakistan. Leuven: KU Leuven. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/3172020?limo=0.

- Zahra, Abiha, and Tobias Bach. 2021. “The Intensity of Organizational Transitions in Government: Comparing Patterns in Developed and Developing Countries.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23276665.2021.1980069.