?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study examines whether leaders’ unethical behaviours discourage people from participating in activities initiated by community-based programmes, and whether the impact of unethical leadership is moderated by the genders of leaders and community members. We conducted a vignette experiment with 1,421 respondents in rural Sri Lanka. We find that village residents perceive: (1) leaders’ unethical conduct discourages residents’ intention to engage in community activities and (2) leaders’ unethical conduct reduces female residents’ engagement more than male residents’, regardless of leaders’ gender. The findings underscore the importance of addressing the low motivation issue, particularly among women, to engage in community activities.

Introduction

This study examines people’s perception on whether the unethical behaviour of leaders influences village residents’ participation in community activities initiated by community-based programmes (CBPs) in Sri Lanka and whether the impact of unethical behaviour is mediated by leaders’ and residents’ gender. We consider two types of leaders’ unethical behaviours – bribery and harassment – which are often prevalent within the CBPs in rural communities (Fredland Citation2010; Koot Citation2019).Footnote1 We conducted a vignette experiment with randomly selected 1,421 village participants residing in a rural area, the Kalutara district, in Sri Lanka. This experiment examined how people’s attitudes towards participation in the village development committees – which control budget allocation and implementation of the Village Development Programmes (VDPs), one form of the CBPs in rural areas of Sri Lanka – were influenced by the unethical behaviour of the hypothetical leader in the village development committees. Each respondent received a vignette with a randomly assigned leader’s gender, village resident’s gender, and the leader’s unethical behaviour (bribery or harassment) and was asked to state to what extent the village resident will actively engage in the community activities next year.

Rural development is a prominent focus in developing countries as it addresses various social, economic, and environmental concerns at the local level (Scoones Citation2013). CBPs have been introduced in the development process since the 1950s to empower individuals and strengthen communities. Effective and ethical leadership is critical for the success of CBPs by providing a clear vision, guidance, and inspiration to community members, fostering collaboration and strong relationships within the community, as well as driving positive change towards programme goals and promoting accountability (Argaw, Fanthahun, and Berhane Citation2007; Ceptureanu et al. Citation2018; Jemutai Citation2020; Mancini and Marek Citation2004; Schmidt and Pohler Citation2018). Ethical leadership is defined as leaders’ behaviour that adheres to a set of moral principles, values, and standards, and ethical leaders demonstrate integrity, honesty, fairness, and accountability in their actions and decisions (O’Leary Citation2019). One crucial problem is the prevalence of unethical leadership, which can be a possible reason of the low rates of village residents’ participation in community activities initiated by CBPs.Footnote2 Unethical conduct has played a major role in causing serious damage to economic and social landscape in developing countries. This, in turn, has undermined social welfare and investment in public services, thereby eroding the quality of life and producing a decline in average life expectancy (Otusanya Citation2011). Such negative consequences are typically associated with institutional weaknesses, such as inadequate monitoring systems and frail legislative and judicial frameworks (Myint Citation2000; Nwabuzor Citation2005). These challenges are frequently encountered by developing countries, particularly in rural areas.

In this study, the ethical parameters of leadership are primarily captured by village residents’ perception on how their leader’s behaviours, particularly unethical behaviours, influence their engagement in community activities. Our study seeks to make the following scholarly contributions. First, given the low rate of participation in community activities of CBPs, it is vital to investigate the factors hindering people’s active engagement. Previous studies focus on factors, such as misalignment with peoples’ need, insufficient coordination, limited capacity of poor people, insufficient communication, and lack of recognition and rewards (Azad et al. Citation2020; Prado Citation2022; Tosun Citation2000). Our study explores one such factor – unethical behaviour of leaders, which has not been extensively investigated in the past research on CBPs.

Second, research on unethical behaviours of leaders tends to focus on private, public, and non-profit organizations (Clement Citation2006; Harris, Kacmar, and Zivnuska Citation2007; Pelletier and Bligh Citation2008; Tepper Citation2000; Tepper et al. Citation2008; Tepper, Duffy, and Shaw Citation2001; Zellers, Tepper, and Duffy Citation2002). However, CBPs are different from these organizations in an important way: in the former, participation is voluntary without payment, while in the latter participants are employed and receive salary. This difference may generate divergence in participants’ response to unethical leadership. Individuals easily quit voluntary roles due to dissatisfaction, but the reliance on a salary often renders leaving a job more challenging in employment. Additionally, the way a leader comes into power is different between CBPs and other organizations: in CBPs, leaders are elected, while in private firms or NGOs, they tend to be appointed. The difference in selection mechanisms may generate divergence in leaders’ unethical behaviours. Elected leaders typically experience higher levels of accountability, a stronger sense of ownership, and closer scrutiny from the community (Castleden and Garvin Citation2008; Ferraz and Finan Citation2009), while appointed leaders may encounter a lack of direct accountability, and disempowerment of the community, potentially leading to disillusionment and resignation among villagers. Therefore, CBPs have an institutional mechanism that can encourage community members to monitor leadership more than in NGOs or private firms, where leaders are appointed. We contribute to the literature of unethical leadership by examining a new combination of leader and follower, namely elected leader with voluntary participants.

Third, another important contribution is to examine gender roles of leaders and village people (potential participants). In rural Sri Lanka, women’s involvement in CBPs, both as leaders and members, remains low. Female leaders often bring unique perspectives and approaches to community development, addressing the diverse needs of the population and enhancing the effectiveness and sustainability of grassroots initiatives (Akerkar Citation2001; Penunia Citation2011). Female residents’ voluntary participation in social activities is also crucial for building fair and inclusive environments with diverse viewpoints, leading to better outcomes in rural communities (Akerkar Citation2001; Sopchokchai Citation1996; Naiga, Penker, and Hogl Citation2019). Despite the importance of women’s roles in leadership and voluntary participation, barriers still exist, particularly in rural areas due to persisting stereotypes and biases in the society (Kaufman and Grace Citation2011), organizational culture and work-life balancing (Maran and Soro Citation2010), and social and cultural norms (Alonso-Población and Siar Citation2018). Our study examines one possible factor that may hamper women’s participation – unethical leadership, which has been under-investigated in the past studies of CBPs. To fill this research gap, building upon the arguments of role congruity and gender congruity (Eagly and Karau Citation2002; Heilman Citation2012; Kennedy, McDonnell, and Stephens Citation2016), we study whether unethical behaviour of female leaders is perceived differently from that of male leaders, and whether female village residents’ evaluation of unethical leadership is different depending on the leader’s gender.

Fourth, although some studies have addressed these issues using quantitative or qualitative methods (Koot Citation2019; Mesdaghinia, Rawat, and Nadavulakere Citation2019; Setokoe and Ramukumba Citation2020), they tend to rely on traditional survey techniques that often suffer from response biases, such as the social desirability bias, since unethical behaviours are sensitive issues which people are reluctant to reveal their true perceptions of, particularly in rural areas. To address this concern, our study employs a survey experiment using vignettes. In the vignettes, we use third-person scenarios to limit socially desirable answers, meaning that respondents are asked what they think the person in the scenario would do rather than what they would do themselves. Presenting respondents with a hypothetical scenario is expected to reduce social desirability bias (León, Arana, and De León Citation2013). Additionally, the use of third-person scenarios is expected to mitigate concerns about revealing their truthful opinions, which may be a substantial barrier in the context of rural Sri Lanka.Footnote3 Thus, we endeavour to offer a novel approach to examining the relationships between leaders’ unethical behaviour and village residents’ engagement in CBP community activities while also accounting for gender differences.

Sri Lanka serves as an ideal setting due to its context of rural development and the prevalence of leaders’ unethical behaviours, such as bribery and harassment, within CBPs. The low rates of participation in community activities of CBPs in Sri Lanka also align with broader challenges faced in rural development efforts globally (Scoones Citation2013). Therefore, examining village residents’ perceptions of the impact of unethical leadership on participation in community activities of CBPs in Sri Lanka could provide valuable insights applicable to similar contexts globally. Additionally, Sri Lanka’s diverse demographic landscape allows us to explore how leaders’ unethical behaviour interacts with gender dynamics, both among leaders and village residents. This aspect is crucial for understanding the effects of unethical leadership on community engagement, especially considering existing literature on gender effects in response to such behaviours (Heilman Citation2012; Kennedy, McDonnell, and Stephens Citation2016; S. Pandey Citation2019). The implications found in this study may provide some guidance for the countries that experience low participation of villagers and low representation of women in leadership positions in CBPs, especially in Asia.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 lays out our hypotheses. Section 3 describes the methods, followed by the presentation of the results in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 provides concluding remarks.

Hypotheses

This section reviews prior research on unethical leadership in public, private, and non-profit organizations (2.1) as well as in CBPs (2.2). It then describes the case of Sri Lanka’s VDP to provide contextual background (2.3). This is followed by a discussion of the relationship between unethical leadership and voluntary participation, hypothesizing that respondents perceive residents’ involvement to be lower when leaders engage in unethical behaviours (2.4). Finally, it lays out hypotheses related to gender roles (2.5). As discussed in Section 1, since we use third-person scenarios in the vignette experiment, our hypotheses are stated in the third person.

Unethical leadership

Numerous studies have delved into the phenomenon of unethical leadership in various sectors, mainly three sectors: public organizations (J. G. Caillier Citation2010; Giommoni Citation2017; Neshkova and Kalesnikaite Citation2019), private organizations (Crews Citation2016; Gorsira et al. Citation2018), and non-profit organizations (de Bruin Cardoso et al. Citation2023; Jayasinghe and Wickramasinghe Citation2006; Jones, Wiley, and Beachy Citation2023; Tavanti and Tait Citation2021). While unethical leadership generally leads to internal conflicts and hinders organizational effectiveness (Brown & Mitchell Citation2010), the specific impacts may vary among public, private, and non-profit organizations. Unethical leadership within private organizations can lead to a detrimental impact on profits, damaging the reputation, and triggering legal consequences (Bello Citation2012; Mayer et al. Citation2009, Citation2013). In public organizations, unethical leader behaviour affects various aspects of accountability to taxpayers, legal and criminal consequences, political fallout and reduction of the effectiveness of service delivery in education, healthcare, public safety, and other critical areas (Beh Citation2017; De Jaeger Citation2023; Hassan Citation2019; Rose-Ackerman and Palifka Citation2016). J. G. Caillier (Citation2010, Citation2010b) explored citizens’ trust in their government’s problem-solving capabilities at the state level and revealed that citizens who perceived corruption tended to have less confidence in their government’s ability.

In non-profit organizations, unethical leadership poses different consequences from private and public organizations. It not only results in the misallocation of public and private funds but also leads to a loss of public trust and donor support and undermines the vital services they provide to communities (Becker, Boenigk, and Willems Citation2020; Hailey Citation2006; Jayasinghe and Wickramasinghe Citation2006; Tavanti and Tait Citation2021). In addition, Jones, Wiley, and Beachy (Citation2023) studied the importance of effective non-profit organization, particularly in context of the crisis experienced by the Florida Coalition Against Domestic Violence (FCADV) between 2019 and 2021 and highlighted how a lack of proper oversight and governance can lead to significant problems within an organization, including ethical lapses. Tavanti and Tait (Citation2021) reviewed the dynamics of destructive leaders and susceptible followers in cases of unethical non-profit organizational behaviours and showed how non-profit toxic leadership primarily erodes public trust. Chapman et al. (Citation2023) reviewed 30 years of empirical research on scandals involving non-profits and identified that scandals within the non-profit sector have been a recurring issue throughout history, with high-profile incidents causing damage to individual organizations and potentially affecting the sector as a whole.

de Bruin Cardoso et al. (Citation2023) explored how the NGO halo effect contributes to unethical behaviour within NGOs and found that the NGO halo effect fosters ethical blind spots within organizations, potentially facilitating or rationalizing unethical conduct. While employees may view their organization and colleagues favourably, this positive perception can sometimes lead to overlooking or rationalizing unethical actions. Therefore, it is essential for NGOs to be aware of how perceptions of their mission and organizational culture influence ethical decision-making and to actively cultivate an ethical climate within the organization. This aspect is particularly critical in the context of CBPs, which are built as the collective working organization, where trust in leaders is pivotal for fostering voluntary participation, especially at the grassroots level.

CBPs

CBPs, or community-based organizations (CBOs), possess similar characteristics to public organizations, yet they also exhibit distinguishing features. Public organizations are government entities responsible for providing services at a broader societal level (Ostrom and Ostrom Citation2019), while CBPs are community-led initiatives aimed at addressing local needs through grassroots efforts and community participation (Korten Citation1980). At the same time, CBPs share similar features to NGOs, but they also demonstrate distinctive characteristics. NGOs are formal organizations with a broader scope of activities and legal status aiming to increase the welfare of poor people in poor countries (Werker and Ahmed Citation2008).Footnote4 Similar to NGOs, CBPs are not-for-profit organizations on a local level and community-led initiatives that focus on addressing local needs through participatory approaches and community engagement (Fattah Citation2023). They work through people-centred modes of development, such as the availability of micro-finance, and community participation in development, ensuring that community health, education, and infrastructure improve over time (Hussain, Khattak, and Khan Citation2008). NGOs are typically characterized by their independence from government control. In contrast, while not universally applicable, CBPs often have close ties with local governments through various mechanisms, including the appointment of executive board members and the contracting of specific village-level projects between CBPs and local government authorities.

The case of rural Sri Lanka

Our study target is the VDPs in Sri Lanka, which take the form of CBPs and are initiatives aimed at rural community development, with voluntary participation typically based on individuals’ willingness to contribute to community projects and activities. In 1955, the community-based Village Development Program (VDP) was established with the assistance of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) as a model of people-centred development in Sri Lanka. This program aimed to improve economic and social infrastructure and living standards in rural areas. The VDP granted village-level organizations administrative authority for planning, implementation, and benefit sharing. It was implemented nationwide to address the lack of basic infrastructure, inequality, unemployment, and poverty. Key activities of the VDP include human resource development, building productive physical infrastructure, enterprise development, social empowerment, improved community service delivery, enhancing household socio-economic status, and fostering social capital.

The VDP committee consists of the chairperson, approximately 10 committee members (such as the vice chairperson and secretary), and rank-and-file members. The Constitution stipulates the number of VDP committee members. The committee members include the vice chairperson, secretary, vice secretary, treasurer, mentor, advisor (Rural Development Officer at Divisional Secretariat – appointed) and another 4/5 committee members. The selection of the VDP chairperson in Sri Lanka generally involves democratic processes, i.e. election by community members of the VDP. In addition to the chairperson, the majority of the committee members are elected by VDP members, while the others (usually two or three) are appointed by local authorities monitoring the VDP. The following are the procedures. First, for each democratically elected position, candidates are nominated by members: one cannot nominate herself to be the candidate; rather, she has to be nominated by a member, and the nomination must be certified by another member. Therefore, for one to be a candidate, at least two other members must be involved. Second, on the election day, elections are held sequentially, starting with the election of the secretary, followed by the chairperson’s position. The same person cannot run for more than one position. For each position, the first-past-the-post rule is used, in which the candidate with the largest number of votes is elected. In some cases, the number of candidates is two, while in other cases it can be three or one (in which case voting does not take place).

Our study has different aspects from past studies. First, we examined the unethical conduct of elected leaders in the context of grassroots initiatives of CBPs at the village level, which differs significantly from the dynamics observed in formal political processes. Grassroots initiatives of CBPs at the village level generally operate with a local focus and direct community engagement, while formal political processes are characterized by hierarchical power structures and representative democracy at broader levels. Second, while most of previous studies relied on qualitative methods or quantitative methods based on traditional surveys, we employed an experimental method to solve response biases and obtain more reliable causal relationships. To the best of our knowledge, limited empirical research has addressed the relationship between unethical conducts of elected leaders and voluntary participation of village residents in community activities. These factors are crucial and distinctive aspects of CBPs in rural Sri Lanka. This study aims to bridge this research gap by conducting an experimental investigation within this framework.

Unethical leadership and voluntary participation

Many studies have shown that unethical leadership is associated with various aspects from employees’ perspectives in the workplaces, such as attitudes (Brown, Treviño, and Harrison Citation2005; Clement Citation2006; Pelletier and Bligh Citation2008; Tepper Citation2000; Tepper et al. Citation2008), tasks and extra-role performance (Harris, Kacmar, and Zivnuska Citation2007; Zellers, Tepper, and Duffy Citation2002), and resistant behaviours and turnover (Tepper Citation2000; Tepper, Duffy, and Shaw Citation2001). Additionally, unethical leadership generally leads to increased turnover, diminished job satisfaction, decreased organizational commitment, heightened conflict between work and family obligations, and elevated psychological distress. Pelletier and Bligh (Citation2008) examined employees’ attributions to unethical leadership, particularly following highly publicized ethical scandals, and found significant impacts of several attributions, including perceptions of moral reasoning deficiencies and breaches of trust, on employees’ well-being.

However, the effects of unethical leadership on voluntary participation can differ from those on employment. Individuals involved in voluntary roles may exhibit greater propensity for disengagement from their positions due to unethical leadership, relative to their counterparts in conventional employment, where the dependence on a salary frequently introduces complexities in the decision-making process regarding resignation. While individuals in voluntary roles have more flexibility in their choices, those in employment face additional challenges due to financial considerations. This difference underscores the importance of considering the context of participation when examining the effects of unethical leadership. In our study, engaging in community activities facilitated by CBPs is regarded as voluntary rather than mandatory. Thus, examining voluntary participation in community activities initiated by CBPs helps us understand how unethical leadership influences organizational dynamics in CBPs.

In addition, the process through which a leader assumes their position could shape perceptions of the leader’s unethical conduct among community members, consequently influencing their motivation to participate in communal activities. There are two types of processes: election by community members and appointment by other authorities, like local government authority. While both elected and appointed leaders may engage in unethical conduct, the procedural context can significantly influence the response of community members. Elected leaders typically operate under higher levels of accountability (Ferraz and Finan Citation2009), foster a sense of ownership (Castleden and Garvin Citation2008), and are subject to scrutiny and potential for change by the community.Footnote5 On the other hand, appointed leaders may evade direct accountability, leading to disempowerment among community members and ultimately resulting in disillusionment and resignations within the village.

Numerous studies have explored the relationship between voluntary participation and unethical leadership (Dasgupta and Beard Citation2007; Le et al. Citation2015; O’Donnell et al. Citation2008; Songorwa Citation1999). For instance, Setokoe and Ramukumba (Citation2020) highlighted that voluntary involvement in community-based tourism in South Africa is perceived as challenging due to corruption. O’Donnell et al. (Citation2008) investigated ethical issues among healthcare social workers in the US through voluntary participation and found an association between overall ethical stress and the intention to leave their positions. In addition, many studies have extensively analysed the cases of unethical behaviour among elected leaders and the subsequent disengagement of followers from these leaders, including the effects of politically corrupt behaviour on citizens’ trust and willingness to voluntarily participate in democratic processes or voting (J. Caillier Citation2010; Caselli and Morelli Citation2004; Giommoni Citation2017; Lipman-Blumen Citation2006), most of which are rooted in the contexts of political sciences.

Based on these arguments on unethical leadership and voluntary participation, we hypothesize that elected leaders’ unethical behaviour is perceived to decrease village villagers’ voluntary engagement in community activities initiated by CBPs.

Hypothesis 1:

Village residents perceive that leaders’ unethical behaviour reduces village residents’ engagement in community activities.

Incorporating gender roles

Another important issue is the under-representation of female leadership and the low rate of female voluntary participation in community activities initiated by CBPs in Sri Lanka. Therefore, we investigate hypotheses that incorporate gender into the discussion of unethical leadership, which is a potential barrier to discourage women’s participation in CBPs.

Gender equality is emphasized in leadership (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Citation2003), because women are underrepresented in leadership positions globally in various fields (Carter and Peters Citation2016; Chen et al. Citation2005; Du and Wimmer Citation2019; Hideg and Shen Citation2019; Hill et al. Citation2016; Kiamba Citation2008). It is crucial in projects in rural villages because female leaders often bring unique perspectives and approaches to community development, addressing the diverse needs of the population and enhancing the effectiveness and sustainability of grassroots initiatives (Akerkar Citation2001; Penunia Citation2011). In addition to female leaders, female voluntary participation in social activities is important for building fair and inclusive environments with diverse viewpoints, leading to better outcomes (Akerkar Citation2001; Sopchokchai Citation1996; Naiga, Penker, and Hogl Citation2019). It is also vital for projects in rural villages. Women often possess valuable local knowledge and insights into community needs, and their involvement promotes social cohesion and inclusivity, contributing to more comprehensive project planning and implementation in rural areas (Alonso-Población and Siar Citation2018; Durán-Díaz et al. Citation2020). Although women’s roles of leadership and voluntary participation are acknowledged as important, persistent barriers continue to hinder many women from assuming leadership positions and engaging in community activities in rural areas.Footnote6

Once the relationship between unethical leadership and voluntary participation is evaluated in Hypothesis 1, this study next explores gender roles in the relationship from two arguments of role congruity and gender congruity. Role congruity theory posits that positive (negative) evaluations of individuals or groups are based on whether they affirm (defy) societal expectations (Eagly Citation1987). Gender plays a significant role in shaping people’s perceptions, especially when connected with a leader’s behaviour (Eagly and Karau Citation2002). Numerous studies suggest that women tend to be subject to more severe penalties when engaging in unethical behaviour in comparison to men (Heilman Citation2012; Kennedy, McDonnell, and Stephens Citation2016). Societal expectations regarding women’s behaviour may lead to bias and prejudice, as their actions might not align with stereotypical feminine qualities or traditional notions of what is considered appropriate for women (Eagly and Karau Citation2002). The concept of role congruity applied to elected leaders highlights a societal expectation for individuals to adhere to traditional gender norms in their behaviour, potentially shaping voter preferences and leading to biases against women candidates who do not conform to these stereotypes (Lizotte and Meggers-Wright Citation2019; Schneider, Bos, and DiFilippo Citation2022).

Unethical behaviour, often seen as a manifestation of agentic actions traditionally associated with more masculine traits, contradicts the conventional female stereotype, which typically expects women to exhibit communal traits emphasizing cooperation, caring for others, and prioritizing the well-being of the community over individual interests (P. Pandey, Singh, and Pathak Citation2021). In addition, expectations of high ethical standards are often placed upon female leaders, with ethical violations often resulting in more stringent penalties for women in leadership (Kennedy, McDonnell, and Stephens Citation2016). Moreover, people are more likely to penalize organizations led by female leaders for their ethical mistakes compared to those led by men (Montgomery and Cowen Citation2020). Higher ethical standards imposed on female leaders may be one of the reasons for the underrepresentation of women in leadership roles in rural Sri Lanka. Greater ethical expectations increase psychological hurdles, which reduces the number of women aspiring to leadership positions, leading to their underrepresentation. To check whether these arguments are generalizable to unethical conduct of elected leaders of CBPs in the rural setting, we propose the following hypothesis regarding the disparity in leader’s gender:

Hypothesis 2:

Village residents perceive that female leaders’ unethical behaviour reduces village residents’ engagement in community activities more than male leaders’ unethical behaviour.

Next, we assess how the impact of unethical leadership on voluntary participation depends on the gender of villagers, which could explain a potential cause behind the low participation rate of female villagers in the CBP activities. Leadership is often associated with agentic actions traditionally linked to masculine traits (Koenig et al. Citation2011). In addition, unethical behaviour is frequently regarded as a manifestation of such agentic actions (S. Pandey et al. Citation2022). Several studies claim that male and female followers respond differently to unethical leadership behaviour, i.e. gender disparities in the responses of male and female followers to their leader’s unethical conduct. For instance, Nisar, Prabhakar, and Torchia (Citation2019) stated that female employees are more likely to report unethical behaviour in the organization than male employees based on their traits of emotion, fairness, and caring. P. Pandey, Singh, and Pathak (Citation2021) revealed that female public servants in the United States demonstrate lower tolerance than their male counterparts when confronted with unethical behaviour by their leaders. Moreover, their research highlights that female public servants tend to express a high level of dissatisfaction in reaction to their leader’s unethical conduct compared to male public servants, indicating that female followers are less tolerant of unethical behaviour exhibited by their leaders. This study examines the extent to which these arguments apply to the unethical behaviour of elected leaders of CBPs in rural areas by assessing the following hypothesis concerning gender disparities among village residents:

Hypothesis 3:

Village residents perceive that leaders’ unethical behaviour reduces female village residents’ engagement in community activities more than male village residents’ engagement.

Gender congruity between leaders and members refers to the alignment or fit between the gender of leaders and the gender composition of the group or organization they lead (Arvate, Galilea, and Todescat Citation2018; Eagly and Karau Citation2002). It generally influences dynamics within the group, including communication and decision-making processes, members’ perceptions of leadership effectiveness, and members’ satisfaction and engagement within the group (Madden Citation2011). The leader-follower relationships have been discussed within a framework of gender congruity arguments in various fields, such as management and public administration (Atwater et al. Citation2001; Eagly, Makhijani, and Klonsky Citation1992; Lewis Citation2000), and gender congruity plays an important role in aligning leadership in various organizations, including public and private organizations (Brown et al. Citation2005; Kim et al. Citation2020). Several studies showed that followers have a preference for gender congruity, where their leader shares the same gender with members, over gender incongruity, where the leader has a different gender with members (Tsui and O’Reilly Citation1989). Grissom, Nicholson-Crotty, and Keiser (Citation2012) also found that male employees collaborating with male leaders tend to report greater job satisfaction and express lower turnover intentions compared to male employees working under female leaders. These findings provide the conjecture that followers or members may display increased tolerance towards unethical behaviour exhibited by leaders of the same gender (gender congruity) compared to leaders of different genders (gender incongruity). In cases of mixed-gender dyads, the follower’s negative response to the leader’s unethical behaviour is more substantial than in cases of same-gender ones. This is particularly significant for CBPs in rural areas, where male leaders are predominant and often face challenges related to low participation of village residents in community activities, particularly in initiatives aimed at encouraging women’s involvement. Applying these arguments to our rural setting of CBPs, we propose the hypotheses related to gender congruity as follows:

Hypothesis 4.1a:

Village residents perceive that male leaders’ unethical behaviour reduces female residents’ engagement in community activities more than male residents’ engagement.

Hypothesis 4.1b:

Village residents perceive that female leaders’ unethical behaviour reduces male residents’ engagement in community activities more than female residents’ engagement.

In contrast to the previous argument on gender congruity, several studies suggest counterintuitive outcome of gender incongruity, where followers demonstrate higher levels of satisfaction with leaders of a different gender than with leaders of the same gender. For instance, Hassan and Hatmaker (Citation2015) examined how gender differences in manager-employee affect employee performance ratings in public employees and showed that women with a male supervisor received more favourable performance ratings in comparison to men with male supervisors. In addition, Cooper (Citation1997) explained that followers tend to set higher standards for leaders who share their gender compared to those of the opposite gender. When same-gender leaders violate personally held behavioural expectations, the follower perceives a more substantial sense of social betrayal (S. Pandey et al. Citation2022). Consequently, followers may demonstrate a higher level of tolerance towards leaders’ unethical behaviour when it is exhibited by a different gender (gender incongruity) compared to leaders of the same gender (gender congruity). This implies that in cases of same-gender dyads, the follower’s negative response to the leader’s unethical behaviour is more substantial than in cases of mixed-gender dyads. Thus, we propose alternative hypotheses to Hypotheses 4.1a and 4.1b as follows:

Hypothesis 4.2a:

Village residents perceive that male leaders’ involvement in unethical behaviour reduces male residents’ engagement in community activities more than female residents.

Hypothesis 4.2b:

Village residents perceive that female leaders’ involvement in unethical behaviour reduces female residents’ engagement in community activities more than male residents.

Methodology

Vignette experiment

We conducted a vignette experiment to examine how leaders’ unethical behaviour in the VDP influences people’s perceptions on residents’ engagement in community activities. In vignette experiments, respondents are shown a short description of different situations (vignettes) to elicit their true judgements, beliefs, or attitudes regarding their intended behaviours (Atzmüller and Steiner Citation2010; Shamon, Dülmer, and Giza Citation2022). This method has been applied to identify how people structure their judgements of social objects socially and individually (Wallander Citation2009) and to infer their decisions or actions in various fields, such as sociology, economics, politics, and medical sciences (Kootstra Citation2016; Ravn and Bredgaard Citation2021; Ung et al. Citation2017; van Breeschoten, Roeters, and van der Lippe Citation2018; Wason, Polonsky, and Hyman Citation2002).

The vignette experiment method is helpful in overcoming the desirability bias because it asks respondents’ attitudes or intended behaviours in randomly varied hypothetical situations (Dülmer Citation2007; Steiner, Atzmüller, and Su Citation2016). In the context of our research, if we ask respondents’ perceptions of their leaders (e.g. whether the leader received a bribe) and their willingness to engage in the CBP, some will hesitate to provide truthful answers, as the topic itself is sensitive and revealing their honest attitudes may have negative consequences. However, by presenting an imaginary situation and asking participants how a community member might behave under the imaginary situation, respondents’ concerns about providing honest opinions should be minimized.

We employed a vignette experiment with three dimensions. The first corresponds to the leader’s gender, the second corresponds to the village resident’s gender, and the third to the unethical behaviour of the leader. The first dimension contains two levels of information regarding the leader’s gender (male and female). The second dimension also consists of two information levels regarding the village resident’s (follower’s) gender (male and female). The third contains three levels of information regarding the leader’s unethical behaviours (without any information regarding unethical behaviours, taking bribes, or making racist comments). Thus, our design has 12 ( = 2 × 2 × 3) scenarios or vignette combinations. presents vignette factors and their corresponding levels (see also Figure A1 in the Appendix for a full description of the vignette presented to the respondents).

Table 1. Vignette dimensions and their levels.

Each respondent was shown a randomly assigned scenario; the level of each dimension was randomized within the dimension and across respondents. Then, each respondent was asked, ‘To what extent do you think that the hypothetical village resident will actively engage in community activities next year?’ The answer choices were presented on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (extremely unlikely) to 5 (extremely likely). A higher score indicates a greater willingness to engage in community activities.

Several studies suggest that experience, or actual action, is preferable to perception because perception is different from experience. Neshkova and Kalesnikaite (Citation2019) emphasized that it is crucial to differentiate between perception and experience by revealing that citizens’ willingness to engage in local governance positively correlates with their personal experiences of corruption, rather than their perception of corruption. Although we admit this issue, we selected to employ perception measurement in our study. This decision is motivated by the fact that obtaining data on respondents’ own experiences is extremely challenging in rural areas. Unethical leader behaviour within CBPs in rural areas constitutes a highly sensitive issue due to their small communities. Given the close-knit nature of village societies, where leaders and respondents are often relatives, or leaders may exert significant power, respondents might be extremely reluctant to openly share their genuine thoughts and level of willingness when questioned about their personal experiences, thus affecting the accuracy of the data obtained. Many scholars have utilized perception studies to gauge respondents’ perceptions of sensitive topics, such as unethical leader behaviour, abortion, domestic violence, and various gender-related issues (Atzmüller and Steiner Citation2010; Barter and Renold Citation1999; J. Caillier Citation2010; Goudriaan and Nieuwbeerta Citation2007; Rettinger, Jordan, and Peschiera Citation2004). Utilizing perception measures allows us to gather insights effectively (Budd and Kandemir Citation2018; Finch Citation1987; Muñoz and Esaiasson Citation2013; Tourangeau and Yan Citation2007; Winters and Weitz-Shapiro Citation2013).

Moreover, individuals in rural areas may not fully disclose even their perceptions of sensitive issues, in addition to their experience. In such cases, employing a third-person scenario becomes an important method for data collection. This approach involves presenting respondents with hypothetical situations involving third parties, rather than directly asking individuals about their own perceptions or opinions. By creating a degree of separation between the context of the vignette and the respondent, researchers can access sensitive issues more effectively. For instance, instead of asking individuals directly about their perceptions, this method allows researchers to explore complex and sensitive topics in a more indirect and potentially less intrusive manner in topics, such as family obligations (Finch Citation1987), peer violence in care homes (Bater & Renold Citation1999), and professionals’ epistemological understandings (Joram Citation2007) drug users’ risk-taking (McKeganey, Abel, and Hay Citation1996). These studies mentioned that using hypothetical scenarios led to more varied and honest responses compared to direct questionnaires.

Sampling procedure

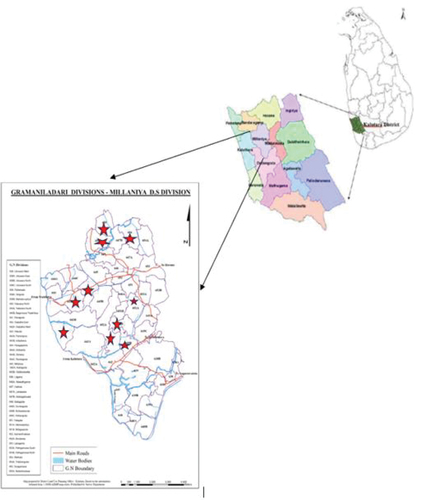

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a vignette experiment in Millaniya, a typical rural region within the Kalutara district of Sri Lanka.Footnote7 Our access to the list of households in the Millaniya division was granted with the approval of the Divisional Secretary (local government). Primary data was collected through a field household survey administered by the first author of this paper. We collected additional information (village profile and list of village residents) from local public officials and chairpersons of the VDPs, which were used in the sampling procedure. Specifically, we employed random selection techniques to choose approximately 100 residents from each village’s list of residents. The village profile facilitates gender-stratified inclusion of residents, ensuring that within each village, the gender distribution of our sample closely aligns with the residents’ list. The survey period was from April 2023 to August 2023.Footnote8

One critical concern of the study is ensuring the representativeness of our sample concerning the broader target population of rural households. To ensure a representative sample, we randomly selected 10 villages out of a total of 44 villages in the Millaniya division: Arakagoda, Batagoda, Bellanthudawa, Boralessa, Dikhena, Gungamuwa, Mulkadakanda, Pelpola, Welikala, and Weniwelpitiya (see in the Appendix). For each selected village, we employed proportionate stratified random sampling based on gender, calculating 10% of the total adult population (over 18 years old) listed in the divisional secretariat records at the village level.Footnote9

To facilitate data collection and randomization, we used the Qualtrics platform for questionnaire design. The randomization procedure within the platform was programmed to evenly distribute respondents among groups, ensuring independent observations and avoiding bias (Dickel and Graeff Citation2018). For each selected village, we randomly chose 100 households from a list provided by the local government offices. Ten survey assistants were hired from public-related offices. All the assistants underwent a 1-day training workshop before the survey, and they underwent meetings frequently throughout the survey period. They visited the randomly selected village residents’ homes to conduct the survey. They carried a mobile smart phone with internet access when contacting each respondent. The survey assistants opened the survey link in Qualtrics and asked each respondent to read the questions carefully and answer on his or her own. In addition, we collected various demographic and socioeconomic information of each respondent in the survey, including gender, age, marital status, and education level. Participation in the survey was voluntary for respondents, and their responses were treated with confidentiality. Since the respondents were Sinhalese, we conducted the survey in the Sinhalese language. We obtained a final sample size of 1,421 participants after discarding those who did not complete the survey.Footnote10

Empirical method

This study empirically examines how people’s perceptions on participation in community activities are influenced by information framings of three dimensions: the leader’s gender (male and female), the village resident’s gender (male and female), and the leader’s unethical behaviours (without any information regarding unethical behaviours, taking bribes, and making racist comments). To do so, we apply the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimations of the following empirical model:

where is a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (extremely unlikely) to 5 (extremely likely), of respondent i’s perception on the hypothetical village resident’s willingness to actively engage in community activities;

is the leader’s gender dummy which equals one for female leader and zero for male leader;

is the village resident’s gender dummy which equals one for female and zero for male;

and

are the dummy variables which equals one for the leader’s involvement of bribery and racist comments and zero otherwise, respectively;

is a set of respondent i’s characteristics, including gender, age, marital status, education, and the VDP membership; and

is the error term.Footnote11

presents the descriptive statistics of the responses in the vignette experiment and respondents’ characteristics. To assess whether or not the randomization worked well, we conducted balance tests by employing probit regressions and examining the relationships between respondents’ characteristics (covariates) and their likelihood of being assigned to the treatment groups. shows the estimated results of the probit estimations. Most covariates were found to be statistically insignificant at the 1% or 5% significance level, indicating successful randomization.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Table 3. Balance tests: probit estimations.

Results and discussion

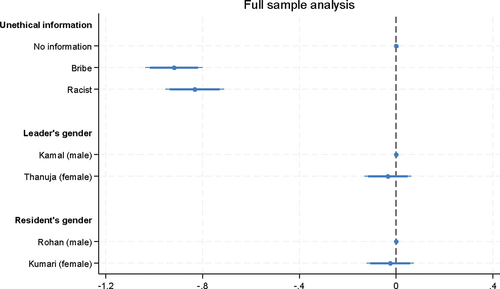

presents the ordinary least square (OLS) estimations of models with and without respondents’ characteristics or covariates.Footnote12 In the estimation models, the base cases (control groups) include the absence of any information, male leader, and male resident for the first (unethical behaviour), the second (leader’s gender), and the third (resident’s gender) dimensions, respectively. Based on the results of the model without the covariates, we generate to visually represent the coefficient plots with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals for each treatment. If the confidence intervals cross the zero mark on the x-axis, this indicates that the variable is not statistically different from the control group or the reference category. A positive coefficient value suggests that respondents perceive that village residents engage more in community activities initiated by CBPs compared to the control condition.

Figure 1. Full sample analysis.

Table 4. OLS estimations with and without covariates.

The analysis shows several clear results.Footnote13 First, the estimated coefficients for bribery and racist comments are significantly negative at the 1% level. Village residents perceive that a leader’s unethical behaviour, including both bribery and racist comments, reduces village residents’ engagement in community activities, which supports Hypothesis 1. Our finding offers compelling evidence affirming a robust connection between perceived unethical conduct and the likelihood of diminished engagement in community activities. This is consistent with the argument of previous studies that unethical leadership behaviour at a personal level presents a more immediate risk to the resources of followers, encompassing their sustained human resource management, both in the public and private sectors (Mesdaghinia, Rawat, and Nadavulakere Citation2019; Vogel and Mitchell Citation2017).

Second, the analysis presents no statistically significant difference in the effects of the information framing between two specific types of unethical behaviours – bribery and racist comments – although the estimated coefficient of bribery is larger than that of racist comments. Respondents perceive that the detrimental impact of a leader’s unethical conduct on residents’ attitudes towards engagement in community activities is significant, whether it involves bribery or racist comments. This result fails to support the argument of P. Pandey, Singh, and Pathak (Citation2021) that workplace harassment, including racist comments, tends to provoke strong reactions, such as resistance, compared to bribery among public sector employees.

Third, the estimated coefficients of female leaders and female residents are insignificant, suggesting that the gender of leaders or residents alone, when not considering congruence or interactions with leaders’ behaviour, does not explain village residents’ engagement in community activities.

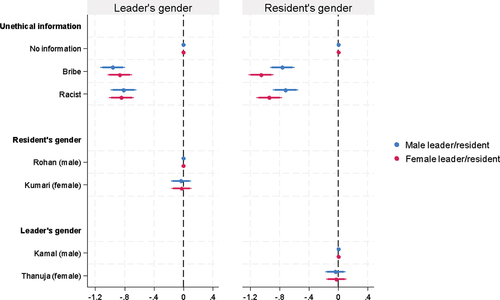

To discuss gender roles more comprehensively, we need to examine the heterogeneous effects across gender of leaders and village residents. To do so, we analyse how information regarding a leader’s unethical behaviour affects a resident’s attitude, considering (i) the leader’s gender (the effect conditional on the leader’s gender) and (ii) the resident’s gender (the effect conditional on the resident’s gender), separately.

First, to evaluate the role of the leader’s gender, we divide the full sample into two subsamples based on the assignment of a leader’s gender in the experiment: (i) male leader and (ii) female leader. In , the first two columns present the OLS results for each subsample, and the third column presents those of the models with the interaction terms of the leader’s gender and unethical conduct using the full sample.

Table 5. Subsample analysis by leader’s gender.

Drawing upon the subsample results, the left panel in shows the coefficient plots for the subsamples of male and female leaders. The estimated coefficients of bribery and racist comments are significantly negative at the 1% level for the subsamples of both male and female leaders; in other words, unethical behaviours discourage village residents’ engagement irrespective of the leader’s gender. The analysis in Column 3 in also shows insignificant coefficients of the interaction terms. Thus, the results show no straightforward evidence that respondents’ perception of village residents’ engagement in community activities depends on the gender of the leader involved in unethical behaviour, which fails to support Hypothesis 2. This is contrary to the finding of Kennedy, McDonnell, and Stephens (Citation2016), which states that female leaders are subject to more pronounced punishment for their unethical conduct than male leaders. Our results also fail to confirm the predictions of the role congruity theory (Eagly and Karau Citation2002) that gender plays a significant role in shaping people’s perception regarding their leader’s unethical behaviour.

Figure 2. Subsample analyses (conditional on leader’s/village resident’s gender).

Table 6. Subsample analysis by village resident’s gender.

Second, like in the previous case, to examine the impact of the resident’s gender, we divide the full sample into two subsamples depending on the random assignment of a resident’s gender: (i) male resident and (ii) female resident. presents the OLS results for each subsample and for the full sample with the model, including the interaction terms, and the right panel in shows the coefficient plots for the subsamples of male and female residents. The estimated coefficients of unethical behaviours are significantly negative at the 1% level for both subsamples, which implies the negative effects of unethical behaviours on engagement in community activities of the VDP irrespective of the resident’s gender. More importantly, the estimated coefficients of unethical behaviours are larger for the subsample of female residents than for that of male residents. The coefficients of the interaction terms for the full sample are significantly negative at the 5% or 10% level. Thus, respondents perceive that the leader’s unethical behaviours, particularly bribery, reduce female residents’ engagement in community activities more than that of male residents, which supports Hypothesis 3. Our results align with the finding of S. Pandey et al. (Citation2022) that female followers in the public sector are less tolerant of unethical behaviour displayed by their leaders.

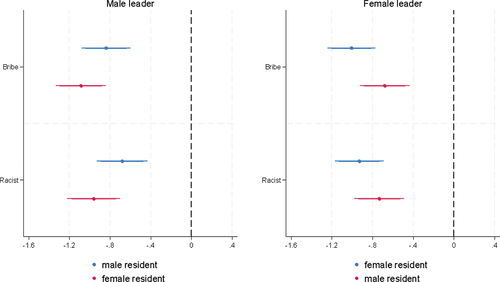

This study further discusses the roles of gender congruity, an alignment between the leader’s and village resident’s gender, by assessing whether a leader’s unethical behaviour would exert a more pronounced impact on a resident’s attitude towards engagement in community activities when the two have the same gender. In this study, gender congruity implies that village residents are more tolerant of unethical behaviour by leaders of the same gender than those of a different gender, while gender incongruity implies that village residents are more tolerant of unethical behaviour by leaders of a different gender. To examine this issue, we split the full sample into four subsamples: (i) male leader and male resident, (ii) male leader and female resident, (iii) female leader and male resident, and (iv) female leader and female resident. The first and second subsamples respectively correspond to the cases of gender congruity and gender incongruity when the leader is male, and the third and fourth subsamples respectively correspond to the cases of gender incongruity and gender congruity when the leader is female. Columns 1, 2, 4, and 5 in and present the OLS results for subsamples (i), (ii), (iii), and (iv), respectively. Columns 3 and 6 present the OLS results of the models with the interaction terms of two assignments (unethical behaviour and village resident’s gender) for the full sample.

Figure 3. Subsample analyses: conditional on pair of leader’s and resident’s gender.

Table 7. Subsample analysis by pairs of leader’s and resident’s gender.

The results show that the gender dyad of the leader-resident is crucial for determining village residents’ perception of how they respond to a leader’s unethical behaviour. Columns 4 and 5 present that given a female leader, the magnitude of the negative effect of unethical behaviours is greater when the village resident is female than when the village resident is male; Column 6 reports the significantly negative coefficient of the interaction term for bribery at the 5% level. In other words, village residents perceive that the negative effects of a female leader’s unethical behaviour are likely to be more substantial for female residents than for male ones. In the case of a female leader, male residents are perceived to be more tolerant of unethical behaviour displayed by their female leaders than female one; that is, gender-congruity has more substantial negative effects than gender-incongruity, which supports Hypothesis 4.2b rather than Hypothesis 4.1b. This result contrasts previous studies, such as Marvel (Citation2015), suggesting that gender congruity (female leader and female resident in our study) is associated with village residents’ greater tolerance, while supporting the finding of Pedersen and Nielsen (Citation2016) that gender incongruity is associated with greater tolerance for leaders’ unethical behaviour.

Alternatively, in the case of a male leader, although Columns 1 and 2 suggest that the negative effect magnitude of unethical behaviour is larger for a female resident than for a male one, Column 3 reports the insignificant coefficients of the interaction terms. This suggests no clear statistical evidence of the differences in the negative effects between male and female residents when the unethical leader is male. Village residents perceive no significant distinction between gender incongruity and gender congruity in the case of a male leader, which supports neither Hypotheses 4.1a nor 4.2a.

We have already confirmed the validity of Hypothesis 3, which argues that female residents exhibit lower tolerance of their unethical leaders than male residents. The extended analysis of the gender (in)congruity has shown that support for the argument depends on the leader’s gender. There is a prevailing perception that female residents are less tolerant of their leader’s unethical behaviour than male residents, particularly when the unethical leader is also female. Conversely, when the unethical leader is male, village residents perceive no clear difference between genders in the degrees of tolerance against the leader’s unethical behaviour.

Conclusion

Ethical leadership is defined by leaders’ commitment to moral principles, values, and standards. Such leaders consistently demonstrate integrity, honesty, fairness, and accountability in their actions and decisions (O’Leary Citation2019). Ethical leadership with good governance is essential for sustainable development and promotes public accountability and transparency, uphold the rule of law, implement anti-corruption measures, foster democratization, and enhance civil society participation (Tsai and Anderson ; World Development Report Citation2017). This study examined village residents’ perception on how their leader’s behaviours, particularly unethical behaviours, influence their engagement in community activities initiated by CBPs. Our experimental analysis has shown several key results. First, we found clear evidence supporting village residents’ perception that a leader’s unethical behaviour, irrespective of bribery or racist comments, significantly diminishes village residents’ engagement in community activities. This underscores the argument that the low rate of participation may be driven by unethical leadership. In the contexts of VDPs in rural Sri Lanka, leaders must be aware of how their unethical behaviours can influence village residents’ attitudes towards commitment and participation.

Second, when considering the heterogeneity across a village resident’s gender, our results revealed that female residents are less tolerant of leaders’ unethical behaviour – particularly for bribery – than their male counterparts, which is consistent with the past literature. This may be one of the reasons why women’s participation remains low in rural Sri Lanka. In other words, unethical leadership may not only depress the overall participation rate but also have a detrimental impact on female voluntary participation. Third, our analysis of gender congruity, specifically exploring how same-gender or mixed-gender dyads of leaders and village residents influence the results, highlighted the significance of gender dyads in shaping village residents’ perceptions. Female residents are more negatively impacted by leaders’ unethical behaviour, compared to their male counterparts, when the unethical leader is female. However, in cases of unethical male leaders, there is no clear difference in the perceptions of the degrees of tolerance against the leader’s unethical behaviour between male and female residents. Community leaders should realize that female residents’ reaction to leaders’ unethical behaviour is more pronounced when the leader is also female.

Our study suggests several policy implications for seeking the promotion of ethical leadership and a more balanced representation of gender within the VDPs. First, given village residents’ perception that a leader’s unethical conduct reduces participation of village residents, building an ethical and inclusive environment is vital for nurturing active engagement. Local and central authorities should establish clear ethical standards for leaders of the VDPs by prioritizing stringent administrative and legal reforms, which target reducing unethical conduct and enhancing accountability and transparency within the VDPs. Offering training programmes on ethical leadership is also essential for current and potential leaders. Second, given that unethical leadership is perceived to reduce female residents’ participation more than male residents’ participation, anti-unethical measures should not only enhance village residents’ overall participation but also specifically encourage greater involvement of women. Furthermore, local authorities should implement gender-sensitive anti-unethical policy measures specifically addressing the vulnerabilities and challenges faced by female villagers. Examples include adoption of zero-tolerance policies for unethical conducts, including harassment and discrimination, with confidential reporting guidance for individuals to report such incidents.

While our study offers several important insights, it is not without limitations. The specific research context may constrain the generalizability of our findings. The study focuses on rural Sri Lanka, and the findings may not be generalizable to other cultural, geographic, or socioeconomic contexts. Ethical perceptions and engagement levels may differ significantly in urban settings or different regions, making it essential to acknowledge the limitations of generalizability. Other external factors may also influence people’s community engagement and determine tolerance levels among village residents, such as economic conditions, political stability, access to resources, cultural and organizational contexts, and leadership development strategies. To advance our understanding, future research should explore diverse settings, such as economic disparities, community types, and cultural variations, and employ multisite studies to enhance generalizability. Moreover, one of the crucial problems is that our analysis was based on village people’s perceptions or opinions rather than their actual experiences, behaviours, or actions. Several studies, such as Neshkova and Kalesnikaite (Citation2019), suggested that perception is different from experience. Thus, it is important to examine how a leader’s unethical conduct, as experience rather than perception, affects village people’s willingness to participate in community activities of CBPs, considering the influence of both leaders’ and followers’ gender. Examining the effects of information framings on village people’s actual behaviours and their dynamic evolution is required to confirm the empirical validity of our findings, deepening our knowledge of the complex interplay among leaders’ behaviours, village residents’ community engagement, and gender.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Notes

1. This study considered leaders’ racist comments as a form of harassment. Racist comments take various forms and range from direct insults and slurs to subtle microaggressions and stereotypes, often targeting someone’s race or ethnicity (Fleras Citation2016; Levchak and Levchak Citation2018). Discrimination often occurs based on religion and ethnic affiliation, influenced by the historical context of civil war of the majority Buddhist Sinhalese with the minority Hindu Tamils in the northern regions in Sri Lanka. Beyond religious and ethnic divisions, there are also local-level divisions, tensions, and conflicts, partly based on caste and property relations (Hettige et al. Citation2018), which can be sources of discrimination and racism. In particular, caste-based discrimination is deep-rooted in public and private spheres in rural Sri Lanka. According to NGO briefing reported to the UN on racial and caste discrimination in Sri Lanka in 2016, the lack of State measures, including the prosecution of caste-based attacks and human rights education to combat the specific discrimination, has affected many aspects of life such as marriage and religious briefs. It is important to note that discriminatory attitudes, including racism, persist in rural Sri Lanka, and thus this study considered racism comments as leaders’ unethical conducts.

2. According to the data of the Department of Rural Development, actual participation rate in the Western province of Sri Lanka is 11% in 2022.

3. We return to this point in detail in Section 3.

4. NGOs are viewed as non-profit organizations that are involved at the grassroots to empower the disadvantaged segments of the population (Clark Citation1991). The role of NGOs has been discussed in the context of the planning and management of rural development projects (Berg Citation1987). Uphoff (Citation1984) and Hussain, Khattak, and Khan (Citation2008) suggested five key activity areas in which NGOs can make their contributions, i.e. natural resources management, rural infrastructure, human resources development, agricultural development, and non-agricultural enterprise.

5. Research on clientelism also suggests that democratically elected leaders may avoid electoral sanction even with poor performance due voters’ lack of information, weak collective action capacity, and vote-buying, among others (e.g. Reinikka and Svensson Citation2004; Stokes Citation2005).

6. Sri Lanka has significant rural-urban disparities so that the government has promoted CBPs as one of rural development initiatives. One problem is the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions and their low participation in community activities. It may relate to strong social norms in rural Sri Lanka, where agriculture and religious traditions dominate (Seneviratne and Currie Citation1994). These norms dictate that women should primarily focus on household duties and caregiving roles (De Alwis Citation2002; Vithanage and Bhadra Citation2020), while men are seen as the main providers and decision-makers (Abeywickrama Citation2016; Silva et al. Citation2022). Such societal expectation about gender stereotypes and role congruity limits women’s opportunities to participate in public and economic activities, including community activities of CBPs, in rural Sri Lanka. Thus, women feel significant barriers to involvement in these initiatives, as their participation is often discouraged or undervalued by the community (Abeyasekera and Amarasuriya Citation2010). This reinforces the existing stereotypes and further entrenches the traditional roles, creating a cycle that is hard to break (Eagly and Karau Citation2002).

7. Our survey in Millaniya division of Kalutara district shows about 10% of all respondents participate. The local authority has identified low levels of VDP activities in this division, making the promotion of community members’ participation crucial for rural development.

8. The survey received prior ethical approval from one of the authors’ institutions. To conduct the survey efficiently, we hired several assistants from NGOs or public-related offices. These assistants underwent a one-day workshop before the survey and participated in weekly meetings throughout the survey period to ensure consistency and quality.

9. The comparisons at the village and gender levels underscore the similarity between our sample and the target population ( in the Appendix). The alignment in these categories provides a substantial basis for asserting that our sample could effectively mirror the target population. Since the list of residents provided by the divisional secretariat includes limited information, it is difficult to confirm whether our sample is consistent with the target population in terms of other resident’s characteristics. While we recognize the significance of this issue, the consistency in terms of village and gender categories partially justifies our claim that our sample is representative of the target population, which mitigates the possibility of sample bias.

10. One of the authors is from Sri Lanka and is very familiar with the culture, norms, and VDPs. This gives us confidence that: (1) the descriptions in the vignette sound realistic; (2) racist remarks and instances of bribery are imaginable; and (3) the third-person scenario can be understood easily.

11. For the robustness checks, we constructed a standardized measure of the dependent variable (with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one) as an alternative approach. The results exhibited qualitative similarity to our baseline results (column 3 of ).

12. We also estimated our models based on non-binary control variables of the respondents’ characteristics (age and education) and confirmed that the results did not change our baseline results qualitatively. We reported a full table of summary statistics in and replication of the regressions with non-binary control variables in column 4 of .

13. Our baseline models include five control variables (respondent’s gender, marital status, VDP membership, age, and education). The OLS estimations in Column 2 of present that compared to respondents who are a non-member of VDP, single, and less educated, those who are a VDP member, married, and highly educated perceive that village residents have a higher intention to engage in community activities. On the other hand, the estimations show insignificant relationships of village residents’ intention with respondent’s gender and age.

References

- Abeyasekera, A., and H. Amarasuriya. 2010. “Why aren’t We Empowered Yet? Assumptions and Silences Surrounding Women, Gender, and Development in Sri Lanka.” In Charting Pathways to Gender Equality: Reflections and Challenges, edited by Centre for Women’s Research, 107–138.

- Abeywickrama, G. 2016. “Fertility Decision-Making by Women in Shanties in Colombo District.” Sri Lanka Journal of Population Studies 15:151–163.

- Akerkar, S. 2001. “Gender and Participation.” In BRIDGE Cutting Edge Pack, edited by A. Cornwall, 1–31. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

- Alonso-Población, E., and S. V. Siar. 2018. “Women’s Participation and Leadership in Fisherfolk Organizations and Collective Action in Fisheries: A Review of Evidence on Enablers, Drivers and Barriers.” In FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No.C1159, I–48. Rome, FAO.

- Argaw, D., M. Fanthahun, and Y. Berhane. 2007. “Sustainability and Factors Affecting the Success of Community-Based Reproductive Health Programs in Rural Northwest Ethiopia.” African Journal of Reproductive Health 11 (2): 79–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/25549718.

- Arvate, P. R., G. W. Galilea, and I. Todescat. 2018. “The Queen Bee: A Myth? The Effect of Top-Level Female Leadership on Subordinate Females.” The Leadership Quarterly 29 (5): 533–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.03.002.

- Atwater, L. E., D. A. Waldman, J. A. Carey, and P. Cartier. 2001. “Recipient and Observer Reactions to Discipline: Are Managers Experiencing Wishful Thinking?” Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 22 (3): 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.67.

- Atzmüller, C., and P. M. Steiner. 2010. “Experimental Vignette Studies in Survey Research.” Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral & Social Sciences 6 (3): 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000014.

- Azad, A. D., A. G. Charles, Q. Ding, A. W. Trickey, and S. M. Wren. 2020. “The Gender Gap and Healthcare: Associations Between Gender Roles and Factors Affecting Healthcare Access in Central Malawi, June–August 2017.” Archives of Public Health 78 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-020-00497-w.

- Barter, C., and E. Renold. 1999. “The Use of Vignettes in Qualitative Research.” Social Research Update 25 (9): 1–6.

- Barter, C., and E. Renold 1999. “The Use of Vignettes in Qualitative Research.” Social Research Update 25 (9): 1–6.

- Becker, A., S. Boenigk, and J. Willems. 2020. “In Nonprofits We Trust. A Large-Scale Study on the public’s Trust in Nonprofit Organizations.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 32 (2): 189–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2019.1707744.

- Beh, L. 2017. “Public ethics and corruption in Malaysia.” In Public Administration in Southeast Asia, edited by E. M. Berman, 171–191. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315089287.

- Bello, S. M. 2012. “Impact of Ethical Leadership on Employee Job Performance.” International Journal of Business & Social Science 3 (11): 228–236.

- Berg, R. J. 1987. “Non-Governmental Organizations: New Force in Third World Development and Politics.” Center for Advanced Study of International Development, Michigan State University.

- Brown, M. E., and M. S. Mitchell 2010. “Ethical and Unethical Leadership: Exploring New Avenues for Future Research.” Business Ethics Quarterly 20 (4): 583–616. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq201020439.

- Brown, M. E., L. K. Treviño, and D. A. Harrison. 2005. “Ethical Leadership: A Social Learning Perspective for Construct Development and Testing.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97 (2): 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002.

- Budd, R., and A. Kandemir. 2018. “Using Vignettes to Explore Reality and Values with Young People.” Qualitative Social Research 19 (2): 1–23.

- Caillier, J. 2010. “Citizen Trust, Political Corruption, and Voting Behavior: Connecting the Dots.” Politics & Policy 38 (5): 1015–1035. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1346.2010.00267.x.

- Caillier, J. G. 2010. “Factors Affecting Job Performance in Public Agencies.” Public Performance & Management Review 34 (2): 139–165. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576340201.

- Carter, D. R., and T. Peters. 2016. “The Underrepresentation of African American Women in Executive Leadership: What’s Getting in the Way.” Journal of Business Studies Quarterly 7 (4): 115–134.

- Caselli, F., and M. Morelli. 2004. “Bad Politicians.” Journal of Public Economics 88 (3–4): 759–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(03)00023-9.

- Castleden, H., and T. Garvin, 2008. “Modifying Photovoice for Community-Based Participatory Indigenous Research.” Social Science & Medicine 66 (6): 1393–1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.030.

- Ceptureanu, S. I., E. G. Ceptureanu, C. E. Luchian, and I. Luchian. 2018. “Community-Based Programs Sustainability. A Multidimensional Analysis of Sustainability Factors.” Sustainability 10 (3): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030870.

- Chapman, C. M., M. J. Hornsey, N. Gillespie, and S. Lockey. 2023. “Nonprofit Scandals: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Framework.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 52 (1): 278S–312S. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640221129541.

- Chen, M., J. Vanek, F. Lund, J. Heintz, R. Jhabvala, and C. Bonner. 2005. “Women, Work & Poverty—United Nations Development Fund for Women.” New York, USA.

- Clark, J. 1991. Democratizing Development: The Role of Voluntary Organizations. London: Earthscan.

- Clement, R. 2006. “Just How Unethical is American Business?” Business Horizons 49 (4): 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2005.11.003.

- Cooper, V. W. 1997. “Homophily or the Queen Bee Syndrome: Female Evaluation of Female Leadership.” Small Group Research 28 (4): 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496497284001.

- Crews, J. 2016. “Leadership Values: Perspectives of Senior Executives in Sri Lanka.” South Asian Journal of Management 23 (3): 193.

- Dasgupta, A., and V. A. Beard. 2007. “Community-Driven Development, Collective Action and Elite Capture in Indonesia.” Development & Change 38 (2): 229–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2007.00410.x.

- De Alwis, M. 2002. “The Changing Role of Women in Sri Lankan Society.” Social Research an International Quarterly 69 (3): 675–691. https://doi.org/10.1353/sor.2002.0036.

- de Bruin Cardoso, I., A. R. Russell, M. Kaptein, and L. Meijs. 2023. “How Moral Goodness Drives Unethical Behavior: Empirical Evidence for the NGO Halo Effect.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 53 (3): 589–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640231179751.

- De Jaeger, A. 2023. “Governance and Corruption in Arm’s Length Public Institutions: Two Belgian Case Studies.” Public Integrity 25 (2): 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2022.2027645.

- Dickel, P., and P. Graeff. 2018. “Entrepreneurs’ Propensity for Corruption: A Vignette-Based Factorial Survey.” Journal of Business Research 89:77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.036.

- Du, J., and H. Wimmer. 2019. “Hour of Code: A Study of Gender Differences in Computing.” Information Systems Education Journal 17 (4): 91–100.

- Dülmer, H. 2007. “Experimental Plans in Factorial Surveys: Random or Quota Design?” Sociological Methods & Research 35 (3): 382–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124106292367.

- Durán-Díaz, P., A. Armenta-Ramírez, A. K. Kurjenoja, and M. Schumacher. 2020. “Community Development Through the Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Cuetzalan Del Progreso, Mexico.” The Land 9 (5): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9050163.

- Eagly, A. H. 1987. “Reporting Sex Differences.” The American Psychologist 42 (7): 756–757. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.42.7.755.