ABSTRACT

Ecotourism is a promising solution for channeling tourism revenues to promote nature conservation and poverty alleviation. However, vulnerable social-ecological conditions may limit the effects of ecotourism in dry rangelands around the world. This study implemented a paired experimental design to survey social-ecological impacts of ecotourism in Ergun grassland, one of China’s most commended ecotourism regions. Compared with livestock feeding business, local ecotourism achieved several sustainable development goals, such as providing income for local people, improving community cooperation, and raising conservation awareness. However, ecotourism caused the loss of forb species and subsequent decreases in ecosystem services. Therefore, ecotourism still had room for improvement in this region, considered the epitome for ecotourism in dry rangelands of China. Besides, climate change and adverse market conditions limited ecotourism to provide enough revenues for local people. Hence, it was better to integrate ecotourism and livestock feeding rather than replace livestock feeding with ecotourism in grassland conservation. In addition, although community-based ecotourism had showed its advantage in this region, it is out of the local community’s capacity to establish a fair market institution and build the necessary infrastructure. Further community engagement and multiple stakeholders’ cooperation are needed to ensure both better public services and vibrant communities.

1. Introduction

Ecotourism is a promising solution for achieving conservation, poverty alleviation, and local development (Fennell, Citation2015; Wondirad, Citation2019; Wunder, Citation2000). Ecotourism can channel tourism revenues to support nature reserves (Gössling, Citation1999) and provide an alternative source of income for local people to reduce their dependency on wildlife exploitation and natural ecosystems (Stronza et al., Citation2019; Wunder, Citation2000). Moreover, ecotourism can help transmit traditional ecological knowledge and improve public awareness for environmental crises in marginal regions of the world (Das & Chatterjee, Citation2015). Therefore, ecotourism (particularly community-based ecotourism) is considered a critical path to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals in nature reserves and neighboring areas (Coria & Calfucura, Citation2012; Fennell, Citation2015; United Nations, Citation2015). Most prominently, ecotourism could help achieve SDG 1 (No poverty), SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth), SDG 14 (Life below water), and SDG 15 (Life on land). However, many studies have found ecotourism to be limited by underdevelopment, such as shortages of financial, human, and social capitals (Coria & Calfucura, Citation2012) as well as by the tourism market’s imperfection, including greenwashing business and conspicuous consumption (Stronza et al., Citation2019). In many cases, ecotourism fails to aid conservation and community development (Ocampo et al., Citation2018; Wall, Citation1997; Wondirad, Citation2019), leading scholars to question the idealistic claims of ecotourism (McKercher, Citation2010; Wondirad, Citation2019).

Policy-makers usually have high expectations for ecotourism in managing dryland rangelands, which occupy 28% of the earth’s land area, support 2 billion people, and thus are critical ecosystems in achieving global sustainability (Briske et al., Citation2020; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Citation2005). Ecotourism indeed had many successful applications in the rangelands of developed countries by balancing trade-offs between conservation and local livelihoods, such as in Canada (Saleh & Karwacki, Citation1996) and Australia (McKercher, Citation2010). Moreover, even in developing countries, where most herders are smallholders can hardly access markets and other public services (Lowder et al., Citation2016), community-based ecotourism has achieved many sustainable goals, for example, the CBNRM program in Namibia and the CAMPFIRE project in Zimbabwe (Nelson et al., Citation2021). However, multiple undesirable results of ‘ecotourism’ have emerged in the dry rangelands of China, such as high charges and fraud in the tourism market, severe damage caused to grasslands by off-road vehicles, and conflicts between tourists and local herders. These undesirable outcomes indicate a knowledge gap in applying ecotourism theories in China’s dry rangelands.

1.1. Concepts and theoretical framework

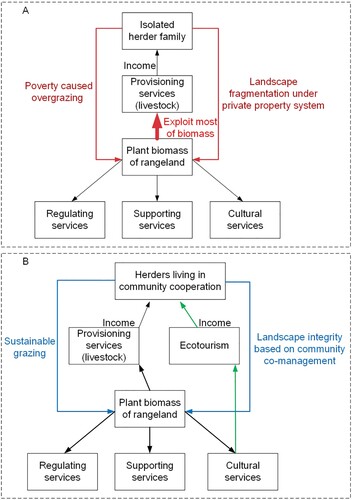

Theoretically, after receiving income from ecotourism, people would exploit less biomass from the local ecosystem. These saving biomass may allocate to enhance supporting, regulating, and cultural services of the local ecosystem (Daily et al., Citation2009; ). Hence, this mechanism, named as alternative income hypothesis (Langholz, Citation1999; Stronza et al., Citation2019), can mitigate conflicts between livelihood and conservation. Besides, this positive effect of ecotourism would be strengthened by obeying the community-based principles (Sonjai et al., Citation2018; Stronza et al., Citation2019). This is because community-based ecotourism can fairly share economic revenues to local people, and has advantages in developing local institutions for sustainable management of common-pool resources, such as forests, grasslands, and wildlife (Jones, Citation2005; Wondirad et al., Citation2020). In this context, community-based ecotourism was considered as by, for, and with local people (Western & Wright, Citation1994; Ma et al., Citation2019), thus guaranteeing the sustainable development goals in achieving economic efficiency, social justice, and environmental conservation (Mbaiwa, Citation2004; Stronza et al., Citation2019).

Table 1. Glossary for the key terms in this study.

Based on the above understanding, policy-makers and scholars have placed high hopes on community-based ecotourism to achieve sustainable management in dry rangelands of China (). Specifically, community-based ecotourism may provide solutions for the two serious problems in dry rangeland management of China, i.e. overgrazing and landscape fragmentation. Overgrazing, mainly caused by the poverty of herders, exploited too much plant biomass as forage. As a result, the remaining plant biomass is too few to maintain species biodiversity, intact community structure, and vital ecosystem functions, such as nutrient cycle and carbon sequestration. As a result, the supporting, regulating, and cultural services declined in the overgrazed rangelands. Therefore, reducing overgrazing is necessary to achieve the optimal trade-off of ecosystem services. Besides, many ecosystem services, such as providing habitats and erosion prevention, are based on intact and open landscapes. However, the intact landscape has been fragmented by the intensive iron-fence system, which is the private property boundary of herder’s families. Only community-based management can restore the intact and open landscape by removing the iron-fence system and re-establishing co-management institutions. Therefore, policy-makers considered ecotourism as an alternative income source to eliminate overgrazing and a pathway to rebuild community cooperation in dry rangeland management.

Figure 1. Policy-makers and scholars expected to use community-based ecotourism to promote sustainable rangeland management. (A) Overgrazing exploited most plant biomass but left very little biomass to maintain supporting, regulating, and cultural services. Besides, the landscape had fragmented for the private property system of grassland, which weakened ecosystem services. (B) Policy-makers considered ecotourism as an alternative income source to eliminate overgrazing and achieve the optimal trade-off of ecosystem services. They also endorsed community-based ecotourism as a pathway to rebuild community cooperation, thus reversing landscape fragmentation.

However, ecotourism may lose its efficiency in dry rangelands, promised by alternative income hypothesis and community-based principles. Highly variable rainfall (Briske et al., Citation2020), long and harsh winter (Sternberg, Citation2018), and low-socioeconomic status of herders (Li et al., Citation2021) had distorted human acts of goodwill. Hence, many unforeseen environmental issues raised and counteracted the benefits of ecotourism in saving biomass. Besides, the rural community had widely declined in the dry rangelands of China. Forty years had passed since the 1980s when the reform of the grassland tenure system divided the vast public grasslands into fragmented, family-owned plots (Li et al., Citation2018; Li & Huntsinger, Citation2011). As a result, herders were strange to community cooperation and usually faced external challenges alone (Li & Li, Citation2012; Liao et al., Citation2020). Especially, the boom of China’s Southeast had drained financial and human capital from rural communities of dry rangeland, only leaving behind the aging people, weak public services, and failing infrastructure (Long et al., Citation2012). Living in declining community, local herders may not fully realize the advantages of community-based ecotourism. Hence, it may be over-optimistic to endorse positive social-ecological outcomes of ecotourism without analyzing its practices in dry rangelands.

1.2. Study objectives

In this study, to estimate the social-ecological effects of ecotourism in dry rangeland of China, we conducted an empirical survey in a representative ‘ecotourism’ region of Inner Mongolian grassland. Using an ecosystem services approach (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Citation2005; Phelan et al., Citation2020), we measured the effects of ecotourism on supporting, regulating, and cultural services of rangeland ecosystem using ecological field surveys. We used a participatory approach to interview herders and other stakeholders in communities to estimate the social-economic effects of local ecotourism. Based on these ecological and interview data, we assessed the economic outcomes of ecotourism and tested two key theories related to ecotourism in dry rangelands. In particular, we focused on the alternative income hypothesis and the community-based principles of ecotourism in developing sustainable ecotourism in dry rangelands of China. Our findings could help small herders and their communities improve ecotourism in China’s dry rangelands, which occupy 40% of the country’s area and support 60 million people as well as diverse cultures. These findings could also provide some useful information for applying ecotourism in dry rangelands of other developing countries.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

We conducted our study in the Ergun Grassland Natural Reserve and near the borders of protected areas (A). The Ergun grassland spans 28,400 km2, from 50°01′ N to 53° 26′ N latitude and 119° 07′ to 121° 49′ longitude. The Ergun grassland has an annual average temperature of −0.5°C and annual precipitation of 240 mm. This region is the birthplace of the Mongolian nation and embraced many Russian immigrants during the Russian Revolution in 1917 (Bai, Citation2015); thus it hosts a diverse community. Ergun is a typical dry rangeland region, where local herders’ economic returns from livestock feeding business were sensitive to the drought, the cost of hay, and the livestock and dairy price (Li et al., Citation2021; Li & Li, Citation2021). The Ergun grasslands, where tourism had spontaneously formed and thrived, was awarded as ‘the best ecotourism grassland region in China’ by the China Central Government ().

Figure 2. The landscape and tourism bussinesses in the Ergun grassland of Inner Mongolia. (A) The geographic location of Ergun and the distribution of interviewed sites; (B) The landscape of Ergun's grazing grasslands; (C) the grasslands used for the restaurants and hotels In Ergun; and (D) the grasslands used for Horse riding and amusement parks in Ergun.

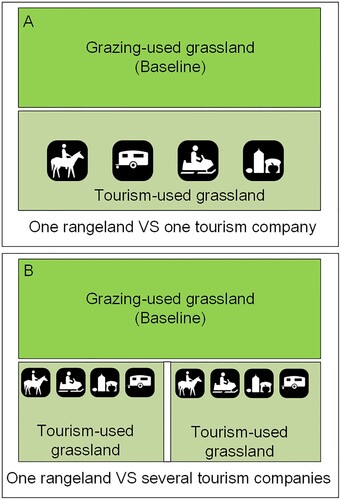

2.2. Field survey design

We focused on all 33 ecotourism companies operating in the region. All companies claimed to run ecotourism operations, and they used about a third of the total regional grassland area. The grasslands, where tourism companies operated, were former pastures belonging to herder families or local communities. Herders did not graze animals on these ecotourism-used grasslands in the tourist season. We formed a paired experimental design by comparing ecological conditions in the grasslands where tourism companies operated and adjacent pastures, which are still used by the landowners to graze animals (). We chose the adjacent pasture for the baseline of paired ecotourism-used grasslands in each study site. Because several ecotourism companies gather together and share the same adjacent pasture for baseline (), we implemented the survey in 20 independent sites in total, including 33 ecotourism-used grasslands for treatment and 20 grazing grasslands for baselines. Therefore, the paired experimental design could represent the alternative ecological effects of ecotourism to the livestock feeding business.

Figure 3. Sketch map for the paired experimental design in a survey site. A survey site consisted of the grassland where tourism businesses operated and adjacent pasture, which is still used by the landowners to graze animals. The pasture was the baseline for tourism-used grasslands. (A) An independent site included one pasture and one company. (B) An independent site contained one pasture and several companies.

2.3. Ecological indicators for ecosystem services

According to the ecosystem services framework of Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Citation2005), we selected a group of widely-used ecological indicators to measure the supporting, regulating, and cultural services for grazing and tourism-used grasslands. We used the following indicators related to primary production of ecosystem and nutrient cycle as proxies of supporting services: aboveground biomass, root biomass in the topsoil layer (0–10 cm and 10–30 cm), litter biomass, plant species richness, the content of total soil nitrogen (TN), the content of total soil phosphorus (TP) in the rooting zone (0–10 cm and 10–30 cm), and biomass of nitrogen-fixing plants (leguminous plants, see Table S1). In addition, we use two ecological indicators to measure the regulating services on carbon emission and mitigation of snow disasters, i.e. soil organic carbon (SOC) content in the rooting zone and the plant community height. The plant community height is positively associated with forage availability after snowfalls, thus reflecting the mitigation capability to snow disaster (Li et al., Citation2017). Indicators of cultural services reflected the scenic appeal and local traditional knowledge, including species richness of flowering plants, community height, and species richness and biomass of traditional medicinal plants (Table S1).

2.4. Ecological survey and laboratory analysis

We conducted an ecological survey about 53 grasslands (33 ecotourism-used grasslands and 20 grazing grasslands as baseline, ) in 20 independent sites from August 5th to 15th, 2019 (i.e. during peak annual standing biomass). In each grassland, we randomly sampled five 1 × 1-m quadrats with the point-centered quarter method (Curtis & Cottam, Citation1950). We measured species richness, average vegetation height, and then clipped live and dead plants at ground level in each quadrat. We combined the dead parts of plants with litter, then collected and sorted all live plants by species type. We used plant functional groups to analyze plant community structure. There are five plant functional groups in Inner Mongolian grasslands, including perennial rhizomatous grasses, perennial bunchgrasses, perennial forbs, annual and biennial plants, and shrub and semi-shrubs (Table S1). After collecting all aboveground biomass and litter, we sampled root biomass by randomly taking three soil cores of 6 cm in diameter at 0–30 cm depth within each quadrat. We rinsed the roots with water using 1-mm mesh sieves. We oven-dried all plant material at 65°C for 48 h to constant weight and weighed the material. We mixed the three soil cores for each quadrat as one composite soil sample and measured the SOC, TN, and TP according to the standard method in the laboratory (Sparks et al., Citation1996). We expressed SOC, TN, and TP contents based on air-dried weights.

2.5. Social-economic survey

During the survey, from May to October 2019, we used a participatory approach to interview 600 local stakeholders, including owners, managers, and workers, from all 33 local tourism companies operating in the Ergun grassland. During every meeting with local stakeholders in each company, we record a range of socio-economic information about local tourism companies, including ownership and management, number and salary of employees, type of tourism services, cost, and profits (Supplementary information 2). We asked 33 managers specifically about their education and experience in running ecotourism. We also requested herders to assess the effects of ecotourism on the grassland environment and their income. We described the adaptations of local herders and communities in developing the skills for tourism. After we got the preliminary results of tourism’s environmental effects, we invited local stakeholders to verify these filed-survey results and identify potential reasons. We also explained the alternative income hypothesis and community-based principles to local herders and asked their opinions about the two theories. In the end, we invited them to identify the main constraints and requirements in running tourism in this region. We also collected information from external stakeholders, such as tourists, tour agency and local government officers. We randomly interviewed 50 tourists and asked their consumption preferences in grassland tourism. We asked ten tour agencies and two local government officers similar questions to verify herders’ statements.

2.6. Data analysis

We described the economic characteristics of different tourism types and analyzed the local herders’ revenue from the tourism business. To assess the ecological effects of ecotourism in this dry rangeland, we used the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) based on the mixed model to compare ecological indicators between grasslands used for ecotourism and those used for grazing. We selected the mixed model and set the ‘survey site’ as the random factor to handle the heterogeneous data structure induced by the spatial auto-correlation among survey sites (Zuur et al., Citation2009).

To examine the alternative income hypothesis in dry rangeland, we divided the herders-owned tourism operators (n = 23) into two groups. In the first group (n = 7), the herders gave up livestock feeding business, ran ecotourism in tourist season, and did temporary jobs in urban areas in the off-tourist season. Therefore, they rented horses and brought traditional food from the local market. The other group (n = 16) was the herders who made a living from ecotourism and livestock feeding. They owned horses and sold self-produced food to tourists. We used factor regression based on the generalized linear model with this categorical variable (the group) to test the alternative income hypothesis by comparing the profit margin between two groups in this grassland region (Dunn & Smyth, Citation2018).

We also divided all local tourism businesses (n = 33) into the community-based managed mode (n = 13), family-owned mode (n = 10), and outside investors owned or jointed mode (n = 10). We then used the same factor regression method to estimate the advantage of community-based ecotourism over other types on local people’s profit margin. However, due to the sample size limitations, we cannot use multiple regressions. Hence, we requested local people to verify these regression results and recorded their explanations. All statistical analyses were implemented in R 3.6.3 (R Core Team, Citation2020).

3. Results

3.1. Social-economic characteristics of local stakeholders

Of the 33 ecotourism companies in the Ergun grassland, local herders owned 10 tourism companies as a family business, while local village communities owned 13 companies in a community-based arrangement. External investors established 6 sole ownership companies and controlled 4 joint companies with local herders. All local tourism companies raised investments by themselves and seldom got subsidies from governments.

All these ecotourism companies created about 1 thousand jobs for local herders and outside workers. Herders who worked in local tourism businesses accounted for 30% of the total population of the region. Most local employees and managers, who were former herders, did not have experience in running ecotourism businesses prior to their current occupation. Only 3 local herders had worked in large tourism agencies before establishing their own companies. Only 18% of managers had a university degree, and most of them were younger than 30 years old. 70% of herders working in the ecotourism business did not give up their livestock as the tourist season is short (June to August). Hence, these herders still raised their sheep and cattle around the tourist season. However, 30% of herders abandoned their animals and held other jobs in the town outside the tourist season.

Due to differences in investment capacity, local tourism companies offered different types of services and thus gained different levels of income (). Among the four types of companies (i.e. operated by herders, communities, investors, or jointly), profits positively correlated with a start-up investment of annual operating costs. In contrast, the profit margin showed the opposite pattern (). Most local herders provided horse-riding services to tourists, as this kind of business is inexpensive to run and only requires horses (D). Some better-off herders established amusement parks, such as karting and flightseeing. People also invested to build and operate restaurants and hotels. Large hotels and two resort hotels were controlled by outside investors. All companies did not provide services centered on local biodiversity, traditional culture, and ecological knowledge (i.e. key characteristics of ecotourism; ; Stronza et al., Citation2019).

Table 2. Characteristics of the 33 surveyed tourism companies in Ergun.

3.2. Ecological effects of ecotourism

Compared with grazing grasslands, many aspects of ecosystem services were significantly weakened in grasslands used for tourism. For supporting services, aboveground biomass, root biomass (10–30 cm soil layer), and species richness were significantly lower than in grazing grasslands (). The plant community hosted less perennial forbs in tourism grasslands than in grazing grasslands, which may cause further changes in other ecosystem services ( and ). Due to the loss of perennial forbs and decline in root biomass, the plant community utilized less soil nitrogen and phosphorus in ecotourism grasslands than in grazing grasslands (). Many forbs that were absent in tourism grasslands have beautiful flowers and are traditional medicinal plants, hence their loss reduced cultural services in tourism grasslands (, , and Supplementary information 1). Plant community height was shorter in tourism grasslands than in grazing grasslands, undermining both regulating service and cultural services ().

Table 3. ANOVA of the differences in each ecosystem service indicator between grasslands used for tourism versus grazing.

Table 4. Changes in the biomass of different plant functional groups between grasslands used for ecotourism versus grazing.

3.3. Alternative income from tourism

Local tourism businesses provided alternative income for herders without government help. Herders who worked as employees earned ∼US$1,500–1,800 per year, which almost equaled their income from raising livestock. Hence, their income doubled for the jobs provided by local tourism businesses. Herders, who were owners of small businesses, achieved more revenues than employed herders ().

Moreover, operators who still kept their livestock had higher profit margins than those who left livestock husbandry and did temporary jobs in urban areas during the off-tourist season, which was detected by the regression () and verified by local people. They argued that it was better to integrate ecotourism with livestock husbandry than to replace grazing with the tourism business completely. They gave us two reasons to support this opinion. First, the tourist season was too short to provide a year-round occupation for local people. Second, local people could sell meat and dairy products to tourists at a fair price to achieve good profits with low grazing intensity.

Table 5. Factor regressions against profit margin among different types of tourism companies.

3.4. Adverse impacts of climate change

Climate change and extreme weather events led to fluctuations in local tourism revenue, which weakened the efficiency of the alternative income hypothesis. Climate change disturbed rainfall patterns and plant phenology, delaying the growing season in the region. For example, a drought in June 2019 caused the yellowing and withering of the landscape early in the tourist season. Disappointed tourists posted these pictures about the drought rangeland landscape on social media, which caused a sharp reduction in the number of tourists in July and August. Extreme weather events external to the region also affected local tourism, such as when typhoons on the east coast of China led to flight cancelations and reduced tourist numbers. Droughts and heavy snowfall also reduced available forage and raised feeding costs for horses, reducing profits from horse-riding operations.

3.5. Environmental awareness of local people

Most respondents, who made a living in local tourism businesses, placed a high priority on grassland conservation. They said the prosperity of ecotourism depended on healthy grassland ecosystems, diverse wildlife, and an open landscape. Local herders also expressed concern about the negative ecological and social impacts of local tourism, which were perceived as trade-offs to profits. Especially, they noticed horse riding caused trampling-damage on vegetation if horse density exceeded 20 horses per 100 ha of grassland. Nevertheless, they computed horse-riding businesses should provide 50 horses per 100 ha of grassland to meet the demands of tour groups and ensure profits. Local herders also perceived amusement parks as neither traditional nor environmentally friendly. Notably, a large area of grassland was seriously disturbed during the installation of a large amusement park. However, herders believed that these activities contributed to attracting tourists and extending their stays, which was confirmed by interviewed tourists. Respondents also stated that restaurants and hotels produced wastewater and garbage that could not be treated.

3.6. Community-based tourism’s advantages and limitations

Community-based tourism showed a higher profit margin than family businesses and investor companies, which was supported by the regression result () and confirmed by local people. They said that the advantages of community-based tourism were rooted in free land rental and the positive effects of cooperation. Many respondents realized the importance of cooperation when starting their new careers in tourism. Local people reduced their costs by sharing experiences and learning from each other. For example, a few herders learned hospitality skills in hotels in the neighboring large city and taught others without charge in the community.

However, community cooperation is limited to local herders and cannot coordinate with travel agents and government officers. Therefore, the local community cannot handle many challenges, such as vulnerable market position and homogenous competition. For instance, herders paid high commissions to local travel agents, with smaller tourism operators paying proportionally higher commissions. For example, horse-riding operators, who usually were small herders, paid 50% commission to travel agents. For hotels and restaurants, this was about 30%. Local travel agents usually blocked operators of tourism companies who refused to pay such high commissions. Some illegal travel agents even deceived tourists with ‘zero-fare tours’ but entrapped them, sometimes by violent threats, to purchase low-quality goods at high prices. Local herders criticized the government for not taking action under those cases. There was also fierce but homogenous competition among local businesses. For example, profits from horse riding decreased by 30% when the number of operators increased from 10 to 16. However, respondents felt unable to provide novel products and cultural services due to the lack of funding and expertise. Moreover, due to poor communication skills, local herders faced many difficulties in providing local scenery and traditional culture to broad audiences by social media, which had profoundly influenced the Chinese tourism market (Cheng et al., Citation2017).

4. Discussion

4.1. Shallow ecotourism but pragmatic compromise

Although the Central Government has singled out the Ergun grassland as one of the best ecotourism regions in China, our study suggests these businesses may not constitute deep ecotourism (Also called hard ecotourism; ; Acott et al., Citation1998; Fennell, Citation2015; Stronza et al., Citation2019). We found some positive consequences of the tourism industry in Ergun, as tourism operators increased local income, improved community cooperation, and enhanced awareness of environmental issues for local herders. However, local tourism provided outdoor recreation but caused some environmental issues, thus violating one of the essential criteria for ecotourism (Acott et al., Citation1998; Stronza et al., Citation2019; Wondirad, Citation2019).

Many social-economic constraints, both from the supply and demand sides, impeded local herders from achieving genuine, deep ecotourism. Many herders transitioned to making a living in the tourism industry after failing in pastoralism due to natural hazards or adverse market conditions (Li et al., Citation2021; Moskwa, Citation2010), so were herders in Ergun. However, they typically could not access enough capital and professional knowledge to run deep ecotourism operations (Acott et al., Citation1998; Ribot & Peluso, Citation2003; Stronza et al., Citation2019). Local herders also faced many difficulties in using social media and preparing materials for environmental education. From the demand side, most Chinese tourists differ from elite eco-tourists, who typically prefer high-level spiritual experiences to luxury accommodation and food (Carvache-Franco et al., Citation2019; Ma et al., Citation2018; Saleh & Karwacki, Citation1996). In Ergun, tourists enjoyed fine food, shopping, and modern attractions, and their behavior was more characteristic of mass tourism than ecotourism (Fennell, Citation2013; Sharpley, Citation2006). Therefore, catering to tourist demand was a pragmatic compromise for local smallholders.

Despite constraints and compromises, smallholders still innovated to ensure positive effects on grassland conservation, reflecting their commitment to community-based cooperation and conservation. Many studies have suggested that community cooperation collapsed under privately owned land-use tenure in rangelands of China (Li & Li, Citation2012). However, local herders worked closely and learned from each other to develop business skills in Ergun. Many surveys reported herders’ dissatisfaction towards the livestock reduction policy in rangelands of China, which aimed to restore grasslands but caused temporary economic losses (Li & Bennett, Citation2019). Nevertheless, local herders of Ergun believed grassland conservation would sustain future incomes from tourism, and they were more than willing to reduce grazing intensity. The emergence of community cooperation and environmental awareness indicated tourism was from the people, by the people, and for the people in terms of the local herders’ perspective. Therefore, tourism in Ergun was not the mass tourism of greenwashing (Stronza et al., Citation2019), rather a kind of shallow ecotourism (also called soft ecotourism, Acott et al., Citation1998; Fennell, Citation2015; Sharpley, Citation2006).

4.2. Unforeseen adverse ecological outcomes

Ecotourism should watch out for unforeseen environmental problems in dry rangelands, which are the complex systems trapped in many tricky management issues (Briske et al., Citation2020; Liao et al., Citation2020). For example, ecotourism (such as trophy hunting) in Namibia led to the building of game-proof fences in private rangelands that unexpectedly limited the mobility of wild animals in protected areas (McGranahan, Citation2011). Similarly, in this study, horse riding was an inclusive business for smallholders that caused an unforeseen loss of perennial forbs and the decline of ecosystem services. The reasons root in the conflicts between physiological characteristics of horses and the demand of the tourism business. Horses graze for 18 h a day, and their urine contains more ammonia than tolerance by plants, causing leaf dehydration and seedling death. Trampling also affects plant sexual reproduction due to damage to flowers and seedlings. Mongolian herders, therefore, raised horses in vast areas and kept high mobility to mitigate horse-induced damage on vegetation according to traditional ecological knowledge (Li & Chen, Citation2021; Takatsuki & Morinaga, Citation2020). However, horse-riding businesses gather large herds of horses around fixed scenic routes, thus causing the loss of forbs and ecosystem services in the landscape. On the other hand, ecotourism with nature-based approaches provided good income and facilitated ecological restoration. For example, the farmers used the rewilding method to convert their dry rangelands from cattle farms to hunting camps in South Africa. The rewilding process restored the vegetation, improved the biodiversity, and made the landscape integrity (Hoogendoorn et al., Citation2019). Therefore, a cautious attitude and regular environmental assessment are essential requirements to avoid unforeseen problems from ecotourism (Pablo-Cea et al., Citation2021). Besides, nature-based management is the key to ensuring the positive outcomes of ecotourism in arid grasslands.

4.3. Special form of alternative income in dry rangelands

Our findings indicated that the alternative income hypothesis took a special form in dry rangelands. According to the alternative income hypothesis, the key function of ecotourism is to provide alternative livelihood options to decrease pressures on natural ecosystems and increase resilience for smallholder communities (Wondirad, Citation2019; Wunder, Citation2000). However, ecotourism is as vulnerable to climate change and market conditions as livestock husbandry in dry rangelands. The adverse impacts of climate change, characterized by water scarcity, shifts in the rainy season, and more severe droughts, are common on the ecotourism of dry rangelands (Jamaliah & Powell, Citation2019). Therefore, it contrasted the effects of ecotourism in providing new income and more robust local economies in wet regions (Brightsmith et al., Citation2008; Phelan et al., Citation2020; Stronza & Gordillo, Citation2008). Besides, in terms of market conditions, high commissions were charged to smallholders, who struggle to access tourists (Tallis et al., Citation2008). In addition, trophy hunting cannot obtain the central government’s permits for the public’s broad opposition (Zhou et al., Citation2021), while the wild animal is too rare to support the wildlife viewing in rangeland regions of China. Therefore, in contrast with the well-operated trophy hunting and wildlife viewing in African dry rangelands (Tchakatumba et al., Citation2019), ecotourism cannot provide such services based on the wild animal resources in China. Therefore, ecotourism can neither completely buffer local economies from climate and market conditions nor provide enough income from pure natural ecosystem, and thus is not a complete substitute for livestock feeding business in dry rangelands of China.

The integration of ecotourism and traditional livestock husbandry, therefore, shows considerable advantages in improving the income of local people in dry grasslands. Ecotourism can improve market access by local herders (Phelan et al., Citation2020). Herders can directly sell meat and dairy products to tourists, thus gaining more profits from livestock than by selling livestock to middlemen (Li et al., Citation2021), potentially limiting overgrazing and further improving sustainable grassland use. In our study, this view was supported by herders’ positive attitude about livestock reducing policy. Moreover, free-grazing livestock was also a part of a special and beautiful scenery for tourists living in cities (Parente & Bovolenta, Citation2012). The most important point was that traditional livestock husbandry is at the core of the local cultural landscape and the self-identity of herders. Local herders could also educate tourists about the local ecological knowledge and traditional culture by presenting their daily pasture life (Tiberghien et al., Citation2018). Combining ecotourism with traditional livestock husbandry is, therefore, a wise choice to provide authentic occupations for local herders and to ensure the vitality of the local community. Consequently, understanding the roles of alternative income will be crucial to implementing ecotourism in dry rangelands.

4.4. Improve community cooperation for deep ecotourism

Although our study confirmed the effectiveness of community-based ecotourism in Ergun, the capability of community was limited to establishing a fair market institution for local tourism and building the necessary but expensive infrastructure. The reason is that community cooperation only consisted of local herders who worked in tourism companies but missed many key external stakeholders, including tourism agencies, local government, social media, and scholars. Local herders had pointed out this limitation and desired additional support from governments to enhance better community-based ecotourism in Ergun.

The petitions of herders should not be misconstrued as dependence – rather, external support is vital for sustainable development of community-based ecotourism in developing countries (Sonjai et al., Citation2018). Even in developed countries, community cannot handle everything without cooperating with government and market (Ostrom, Citation1996; Ostrom et al., Citation2007). Especially, many elements of ecotourism are strange to the rural communities in undeveloped regions (Sonjai et al., Citation2018). Therefore, effective community-based ecotourism should involve a range of external stakeholders who may introduce solutions and improvements (Stone, Citation2015). In fact, international conservation organizations, such as the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), had played an important role in developing community-based ecotourism in Africa by providing start-up funds and training for business and trade skills (Nelson et al., Citation2021). Policy-makers could learn these international experiences when promoting ecotourism in China. Moreover, people in marginal rural regions of China, especially dry rangeland areas, have a history of contributing natural and human resources to prosperous urban areas, yet they suffer from aging populations, lagging infrastructure, and the declining of communities. Therefore, Chinese governments should no longer stand by and do nothing when the local community faces difficulties in developing deep ecotourism, but take more responsibility to promote ecotourism in undeveloped regions.

Governments can enhance the effects of community-based ecotourism by building infrastructure, training necessary skills, and creating equal collaborative partnerships with extra stakeholders. Many previous studies had proved the positive effects of such governments’ services in developing community-based ecotourism (Fennell, Citation2015). For example, in the Wa district of Ghana, the government-invested road network had benefited both ecotourism businesses and local people’s livelihood (Bonye et al., Citation2021). Another example, local governments of Vietnam had successfully inspired community-based ecotourism by arbitrating the conflicts among multiple stakeholders (Ngo et al., Citation2019).

However, it is paradoxical that governments should decentralize powers to the rural community for promoting ecotourism, yet also act as a ‘big government’ to provide financial, educational, scientific, and technological resources for rural people (Li et al., Citation2021; Luo et al., Citation2018; Pawar, Citation2003). Because China is a typical country characterized by ‘big government and small society’, the local community may lose its autonomy to government agencies and accept top-down management in running ecotourism when receiving governments’ funding. The African experiences had suggested the strong negative effects of top-down control on community-based ecotourism (Nelson et al., Citation2021). Top-down management could inhibit the local community from developing homegrown approaches for ecotourism. Besides, the management agencies may be easily captured by local elites and private sectors, thus cutting off the connections between ecotourism and the local community, and reducing the revenue allocated to local people (Tchakatumba et al., Citation2019). In contrast, the success in Namibia indicated that providing funds and educations but respecting the experiments and innovation of the local community was the wise choice to achieve sustainable ecotourism (Nelson et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the next task is to coordinate local people and governments to ensure better public services and vibrant communities in the dry rangelands of China.

5. Conclusions

Ergun’s tourism business achieved a few sustainable development goals but also caused some adverse environmental impacts. Local tourism provided alternative income for herders, improved community cooperation, and promoted environmental awareness, thus achieving SDG 1 (No poverty) and SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth). However, local tourism did not provide any environmental education for tourists but pleasured them by luxurious facilities and non-native entertainments. These artificial elements of Ergun’s tourism modified the local social-ecological system and thus violated the core spirit of ecotourism. Moreover, these disturbances of tourism businesses caused loss of forb species and associated decreases in ecosystem services. Hence, Ergun’s ‘ecotourism’ was still shallow and had considerable room for deep status. As one of China’s most commended ecotourism regions, the Ergun’s shallow ecotourism represented in microcosm the needed improvement in applying this conservation approach in China’s dry rangelands.

This study highlighted the importance of integrating the core principles of ecotourism with smart practices to adapt to the fragile social-ecological system of dry rangelands. Because of the synchronous vulnerability to climate change and bad markets, both ecotourism and traditional livestock grazing cannot guarantee a steady income for local herders. Hence, policy-makers should not simply apply the alternative income hypothesis to replace livestock grazing with ecotourism completely. However, integrating ecotourism with reducing intensity of livestock grazing was the special form of alternative income hypothesis to ensure positive economic and environmental outcomes in dry rangelands. Besides, dry rangeland ecosystems are sensitive to novel disturbances induced by building facilities and providing entertainment for tourists. Therefore, ecotourism operators should conduct more assessments with the strictest criteria of deep ecotourism to prevent unforeseen ecological problems. Moreover, because herders faced difficulties in obtaining public services and fair trade in the declined community, community-based ecotourism cannot fully play its effectiveness in achieving sustainable development in dry rangelands. Therefore, governments should not shirk its responsibility in providing public services and maintaining law order under the pretext of following the principles of community-based ecotourism. Governments should help local operators of ecotourism coordinate with tourist agencies and scholars to obtain financial, educational, and technical resources. However, increasing governments’ help and investment should also avoid the impediment of over-bearing governments in developing community-based ecotourism. These findings could help bridge the gap between general theories of ecotourism and the specific situation of the social-ecological system in dry regions.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (140.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank local people for their help during our survey in Ergun. We also thank Professor David Fennell and two anonymous reviewers for their comments, which help us improve this study. The authors have confirmed that any identifiable participants in this study have given their consent for publication. The raw data for this study are available from the corresponding author on request. There is no third-party material in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acott, T. G., Trobe, H. L. L., & Howard, S. H. (1998). An evaluation of deep ecotourism and shallow ecotourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 6(3), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589808667314

- Bai, P. (2015). A survey of the Russian language use in Inner Mongolia’s Ergun city. In Y. Li, & W. Li (Eds.), The language situation in China (Vol. 1, pp. 137–143). De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501503146-014

- Bonye, S. Z., Yiridomoh, G. Y., & Dayour, F. (2021). Do ecotourism sites enhance rural development in Ghana? Evidence from the Wechiau Community Hippo Sanctuary Project in the Upper West Region, Wa, Ghana. Journal of Ecotourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2021.1922423.

- Brightsmith, D. J., Stronza, A., & Holle, K. (2008). Ecotourism, conservation biology, and volunteer tourism: A mutually beneficial triumvirate. Biological Conservation, 141(11), 2832–2842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.08.020

- Briske, D. D., Coppock, D. L., Illius, A. W., & Fuhlendorf, S. D. (2020). Strategies for global rangeland stewardship: Assessment through the lens of the equilibrium–non-equilibrium debate. Journal of Applied Ecology, 57(6), 1056–1067. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13610

- Carvache-Franco, M., Segarra-Oña, M., & Carrascosa-López, C. (2019). Segmentation and motivations in eco-tourism: The case of a coastal national park. Ocean & Coastal Management, 178, 104812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.05.014

- Cheng, M., Wong, I. A., Wearing, S., & McDonald, M. (2017). Ecotourism social media initiatives in China. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(3), 416–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1214141

- Coria, J., & Calfucura, E. (2012). Ecotourism and the development of indigenous communities: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Ecological Economics, 73(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.10.024

- Curtis, J. T., & Cottam, G. (1950). Plant ecology work book: Laboratory, field and reference manual. Burgess Publishing Company.

- Daily, G. C., Polasky, S., Goldstein, J., Kareiva, P. M., Mooney, H. A., Pejchar, L., Ricketts, T. H., Salzman, J., & Shallenberger, R. (2009). Ecosystem services in decision making: Time to deliver. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 7(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1890/080025

- Das, M., & Chatterjee, B. (2015). Ecotourism: A panacea or a predicament? Tourism Management Perspectives, 14(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.01.002

- Dunn, P. K., & Smyth, G. K. (2018). Statistical models. In P. K. Dunn, & G. K. Smyth (Eds.), Generalized linear models with examples in R (pp. 1–29). Springer Nature.

- Fennell, D. A. (2001). A content analysis of ecotourism definitions. Current Issues in Tourism, 4(5), 403–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500108667896

- Fennell, D. A. (2013). Ecotourism. In A. Holden, & D. A. Fennell (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of tourism and the environment (pp. 323–333). Routledge.

- Fennell, D. A. (2015). Ecotourism fourth edition, 3-20. Routledge.

- Gössling, S. (1999). Ecotourism: A means to safeguard biodiversity and ecosystem functions? Ecological Economics, 29(2), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00012-9

- Hoogendoorn, G., Meintjes, D., Kelso, C., & Fitchett, J. (2019). Tourism as an incentive for rewilding: The conversion from cattle to game farms in Limpopo province, South Africa. Journal of Ecotourism, 18(4), 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2018.1502297

- Jamaliah, M. M., & Powell, R. B. (2019). Integrated vulnerability assessment of ecotourism to climate change in dana biosphere reserve, Jordan. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(22), 1705–1722. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1401982

- Jones, S. (2005). Community-based ecotourism: The significance of social capital. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(2), 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.06.007

- Langholz, J. (1999). Exploring the effects of alternative income opportunities on rainforest use: Insights from Guatemala’s maya biosphere reserve. Society & Natural Resources, 12(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/089419299279803

- Li, A., & Chen, S. (2021). Loss of density dependence underpins decoupling of livestock population and plant biomass in intensive grazing systems. Ecological Applications, 31, e02450. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2450

- Li, A., Chen, S., Zhang, X., & Huang, J. (2017). Political pressures increased vulnerability to climate hazards for nomadic livestock in Inner Mongolia, China. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 8256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08686-4

- Li, A., Gao, L., Chen, S., Zhao, J., Ujiyad, S., Huang, J., Han, X., & Bryan, B. A. (2021). Financial inclusion may limit sustainable development under economic globalization and climate change. Environmental Research Letters, 16(5), 054049. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abf465

- Li, A., Wu, J., Zhang, X., Xue, J., Liu, Z., Han, X., & Huang, J. (2018). China’s new rural “separating three property rights” land reform results in grassland degradation: Evidence from Inner Mongolia. Land Use Policy, 71(2), 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.11.052

- Li, P., & Bennett, J. (2019). Understanding herders’ stocking rate decisions in response to policy initiatives. Science of The Total Environment, 672, 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.407

- Li, W. J., & Huntsinger, L. (2011). In pursuit of knowledge: Addressing barriers to effective conservation evaluation. Ecology and Society, 16(2), 14. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol16/iss2/art1/. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04099-160214

- Li, W. J., & Li, Y. B. (2012). Managing rangeland as a complex system: How government interventions decouple social systems from ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 17(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04531-170109

- Li, Y. B., & Li, W. J. (2021). Do fodder import and credit loans lead to climate resiliency in the pastoral social-ecological system of Inner Mongolia? Ecology and Society, 26(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12245-260127

- Liao, C., Agrawal, A., Clark, P. E., Levin, S. A., & Rubenstein, D. I. (2020). Landscape sustainability science in the drylands: Mobility, rangelands and livelihoods. Landscape Ecology, 35(11), 2433–2447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01068-8

- Long, H., Li, Y., Liu, Y., Woods, M., & Zou, J. (2012). Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by ‘increasing vs. decreasing balance’ land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy, 29(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.04.003

- Lowder, S. K., Skoet, J., & Raney, T. (2016). The number, size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Development, 87, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.041

- Luo, J. D., Shuai, M., & Yang, K. (2018). A sociological analysis of the “strong central, weak local” pattern of trust in government: Based on three stage tracking data after the wenchuan earthquake. Social Sciences in China, 39(3), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02529203.2018.1489032

- Ma, A. T. H., Chow, A. S. Y., Cheung, L. T. O., Lee, K. M. Y., & Liu, S. (2018). Impacts of tourists’ sociodemographic characteristics on the travel motivation and satisfaction: The case of protected areas in South China. Sustainability, 10(10), 3388. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103388

- Ma, B., Yin, R., Zheng, J., Wen, Y., & Hou, Y. (2019). Estimating the social and ecological impact of community-based ecotourism in giant panda habitats. Journal of Environmental Management, 250, 109506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109506

- Mbaiwa, J. E. (2004). The socio-economic benefits and challenges of a community-based safari hunting tourism in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Journal of Tourism Studies, 15(2), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.200501357

- McGranahan, D. A. (2011). Identifying ecological sustainability assessment factors for ecotourism and trophy hunting operations on private rangeland in Namibia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(1), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2010.497219

- McKercher, B. (2010). Academia and the evolution of ecotourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2010.11081615

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2005). Dryland systems. In Ecosystems and human well-being: Current state and trends (pp. 623–662). Island Press.

- Moskwa, E. (2010). Ecotourism in the rangelands: Landholder perspectives on conservation. Journal of Ecotourism, 9(3), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040903125047

- Nelson, F., Muyamwa-Mupeta, P., Muyengwa, S., Sulle, E., & Kaelo, D. (2021). Progress or regression? Institutional evolutions of community-based conservation in Eastern and Southern Africa. Conservation Science and Practice, 3(1), e302. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.302

- Ngo, T., Hales, R., & Lohmann, G. (2019). Collaborative marketing for the sustainable development of community-based tourism enterprises: A reconciliation of diverse perspectives. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(1), 2266–2283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1446919

- Ocampo, L., Ebisa, J. A., Ombe, J., & Geen Escoto, M. (2018). Sustainable ecotourism indicators with fuzzy Delphi method – A Philippine perspective. Ecological Indicators, 93, 874–888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.05.060

- Ostrom, E. (1996). Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Development, 24(6), 1073–1087. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X

- Ostrom, E., Janssen, M. A., & Anderies, J. M. (2007). Going beyond panaceas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(39), 15176–15178. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701886104

- Pablo-Cea, J. D., Velado-Cano, M. A., & Noriega, J. A. (2021). A first step to evaluate the impact of ecotourism on biodiversity in El Salvador: a case study using dung beetles in a National Park. Journal of Ecotourism, 20(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2020.1772798

- Parente, G., & Bovolenta, S. (2012). The role of grassland in rural tourism and recreation in Europe. In P. Goliński, M. Warda, & P. Stypiński (Eds.), Grassland – A European resource? (pp. 733–743). Proceedings of the 24th General Meeting of the European Grassland Federation. https://www.europeangrassland.org/fileadmin/documents/Infos/Printed_Matter/Proceedings/EGF2012.pdf

- Pawar, M. (2003). Resurrection of traditional communities in postmodern societies. Futures, 35(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(02)00058-7

- Phelan, A., Ruhanen, L., & Mair, J. (2020). Ecosystem services approach for community-based ecotourism: Towards an equitable and sustainable blue economy. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(10), 1665–1685. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1747475

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Ribot, J. C., & Peluso, N. L. (2003). A theory of access*. Rural Sociology, 68(2), 153–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x

- Saleh, F., & Karwacki, J. (1996). Revisiting the ecotourist: The case of grasslands national park. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 4(2), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589608667259

- Sharpley, R. (2006). Ecotourism: A consumption perspective. Journal of Ecotourism, 5(1-2), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040608668444

- Sonjai, N. P., Bushell, R., Hawkins, M., & Staiff, R. (2018). Community-based ecotourism: Beyond authenticity and the commodification of local people. Journal of Ecotourism, 17(3), 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2018.1503502

- Sparks, D. L., Page, A., Helmke, P., Loeppert, R., Soltanpour, P., Tabatabai, M., Johnston, C., & Sumner, M. (1996). Methods of soil analysis. Part 3-chemical methods. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Sternberg, T. (2018). Investigating the presumed causal links between drought and dzud in Mongolia. Natural Hazards, 92(S1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-017-2848-9

- Stone, M. T. (2015). Community-based ecotourism: A collaborative partnerships perspective. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2-3), 166–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1023309

- Stronza, A., & Gordillo, J. (2008). Community views of ecotourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 448–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.01.002

- Stronza, A. L., Hunt, C. A., & Fitzgerald, L. A. (2019). Ecotourism for conservation? Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 44(1), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-101718-033046

- Takatsuki, S., & Morinaga, Y. (2020). Food habits of horses, cattle, and sheep-goats and food supply in the forest–steppe zone of Mongolia: A case study in Mogod sum (county) in Bulgan aimag (province). Journal of Arid Environments, 174, 104039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2019.104039

- Tallis, H., Kareiva, P., Marvier, M., & Chang, A. (2008). An ecosystem services framework to support both practical conservation and economic development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(28), 9457–9464. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705797105

- Tchakatumba, P. K., Gandiwa, E., Mwakiwa, E., Clegg, B., & Nyasha, S. (2019). Does the CAMPFIRE programme ensure economic benefits from wildlife to households in Zimbabwe? Ecosystems and People, 15(1), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2019.1599070

- Tiberghien, G., Bremner, H., & Milne, S. (2018). Authenticating eco-cultural tourism in Kazakhstan: A supply side perspective. Journal of Ecotourism, 17(3), 306–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2018.1502507

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. In Resolution adopted by the General Assembly. Annex A/RES/70/1. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf.

- Wall, G. (1997). FORUM: Is ecotourism sustainable? Environmental Management, 21(4), 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002679900044

- Western, D., & Wright R. M. (1994). The background to community-based conservation. In Western, D., Wright, R. M. & Strum, S. C. (Eds.), Natural connections: Perspectives in community-based conservation (pp. 1–12). Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Wondirad, A. (2019). Does ecotourism contribute to sustainable destination development, or is it just a marketing hoax? Analyzing twenty-five years contested journey of ecotourism through a meta-analysis of tourism journal publications. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(11), 1047–1065. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1665557

- Wondirad, A., Tolkach, D., & King, B. (2020). Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tourism Management, 78, 104024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104024

- Wunder, S. (2000). Ecotourism and economic incentives — an empirical approach. Ecological Economics, 32(3), 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00119-6

- Zhou, X., MacMillan, D. C., Zhang, W., Wang, Q., Jin, Y., & Verissimo, D. (2021). Understanding the public debate about trophy hunting in China as a rural development mechanism. Animal Conservation, 24(3), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12638

- Zuur, A. F., Ieno, E. N., Walker, N., Saveliev, A. A., & Smith, G. M. (2009). Dealing with heterogeneity. In A. F. Zuur, E. N. Ieno, N. Walker, A. A. Saveliev, & G. M. Smith (Eds.), Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R (pp. 71–100). Springer Nature.