ABSTRACT

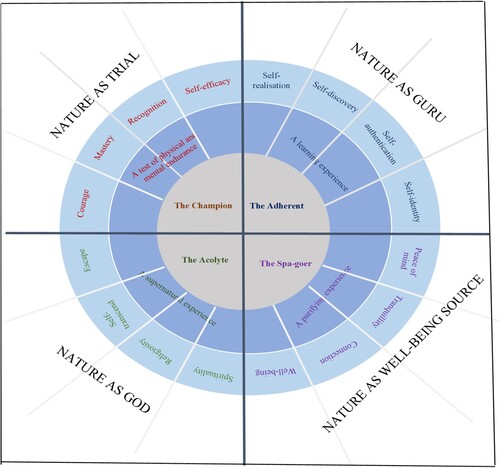

Most ecotourism research focuses on logical, expressed desires, while deeper meanings (or symbolic desires), are less well understood, perhaps because elicitation is difficult. Consequently, prior research is relatively limited on the deeper motivations driving ecotourism behaviour. To address that lack, an ethnographic study of nature-based tourism activities in Malaysia and a symbolic interactionist approach is taken to unpack hedonic meaning-making. The data gave rise to four ecotourist archetypes: The champion, the adherent, the acolyte, and the spa-goer, for ecotourists seeking trial, spiritual, learning and purification benefits, respectively. The study provides both greater insight into how to use ethnographic research to elicit symbolic desires in ecotourism, and practitioner support for the design and delivery of more fulfilling nature-based tourism experiences. The archetypes can be viewed as a symbolic benefits-based market segmentation schema, forming the basis for developing more effective targeting, positioning, branding and value propositions for nature-based tourism activities.

Introduction

The positive effects of engagement with the natural world are well established (Bertram & Rehdanz, Citation2015; Kunchamboo et al., Citation2021). Benefits include increased life satisfaction (Bertram & Rehdanz, Citation2015), attention restoration (Berman et al., Citation2008), improved mood, lower anxiety and stress levels (Ulrich et al., Citation1991), and enhanced pro-social behaviour (Spano et al., Citation2021). Consciously or unconsciously, ecotourists seek out these benefits. However, most studies of ecotourists focus on objective criteria such as destination choice and behaviours (Weaver & Lawton, Citation2007). More recently, studies have investigated deeper intrinsic psycho-social elements (Nowaczek & Smale, Citation2010), however, these studies continue to elicit data using conventional self-reporting methodologies. Furthermore, samples are drawn from western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic (WEIRD) participants, thus providing a partial view (Fletcher, Citation2009; Henrich et al., Citation2010). Non-Western perspectives are lacking. This study addresses the balance in two ways, firstly by providing a perspective of ecotourist motivations based on deep symbolic meaning-making currently lacking, and secondly by drawing on non-WEIRD data. We thus contribute a perspective hitherto unavailable in the ecotourism literature – one drawn from deep engagement with non-conventional participants’ unconscious desires.

The study informing our work is an ethnographic study involving 11 nature-based ecotourism experiences in Peninsular and East Malaysia. The activities ranged from a strenuous three-day trek to the summit of Mt Kinabalu, to a relatively sedate walk through local botanic gardens. In addition to the observation field notes, data is supported by 15 depth interviews. Each participant generated their own meanings from their experiences, which we helped them elicit through projective fieldwork techniques (Donoghue, Citation2000). Drawing on a symbolic interactionist reading of the data, we apply Jungian principles to develop four ecotourist archetypes, supported by imaginative rather than objectivist perceptions of reality (Morris & Schmolze, Citation2006). The archetypes contribute more intimate knowledge of ecotourists and draw attention to the importance of symbolic meanings in nature engagement. For practitioners, the research demonstrates the application of multi-sensory approaches in eliciting latent ecotourist perceptions. For ecotourism operators, the archetypes can be viewed as a benefit segmentation scheme, providing the basis for more informed decision making about target marketing, value proposition development, branding and positioning. The objectives of this research are threefold: (1) to demonstrate how we might elicit unexpressed or inexpressible (i.e. symbolic) desires, (2) to provide a voice to under-represented participants; and (3) to consider how symbolic desires might translate to more effective ecotourism design and management practice. The study answers the question, why do ecotourists seek out nature-based experiences? Further, it demonstrates the potential of symbolic interactionism-based approaches, by answering the question, how do symbolic meanings drive decision making with respect to nature-based experiences? Our purpose is to demonstrate the potential of approaches based on symbolic interactionism to uncover deeper, subtle, and harder to elicit meanings in the ecotourism experience, which have hitherto attracted limited attention.

The paper proceeds with a review of the literature on symbolic interactionism, establishing the importance of symbolic desires driving human behaviour, and defines our focus on ecotourism. The next section addresses the study’s method, followed by interpretative findings and discussion of emergent themes. We conclude with research implications.

Literature review

In the symbolic interactionist view, meaning-making is fundamental to the human experience, allowing inferences to be drawn about the qualities of objects, experiences, and people (Mathews et al., Citation2009; Nasar, Citation1989). We each make sense of the external world in our own unique and individual ways through abstract thought and reflexivity, and by assigning meanings to artefacts and events (Blumer, Citation1998). We make decisions based on multisensory imagery, fantasy and emotions; rather than ‘real’ reality, we act on our ideas of what a desirable reality might look like (Hirschman & Holbrook, Citation1982). However, as symbolic meaning-making is subconscious or even unconscious, uncovering private and unexamined meanings idiosyncratic to the meaning makers creates challenges for research. Consequently, in most disciplines including ecotourism, most work is based on objective approaches such as self-reports (Nowaczek & Smale, Citation2010; Tabaeeian et al., Citation2022), and interviews (Jamaliah et al., Citation2021; Wearing et al., Citation2002). These approaches aggregate participant responses into one (arguably) shared reality, which becomes an agreed on and unquestioned objective truth, thus constituting rather than representing the field (Van Maanen, Citation2011). Among other things, the danger is that an ‘average’ view of reality does not reflect the rich nuances of social and cultural life, and that researchers may inadvertently silence non-conventional or outlying voices and views, creating layers of ‘noise’ between source data and eventual reportage.

As ecotourism is directed at human flourishing rather than a simple business transaction or service encounter (Donohoe & Needham, Citation2006), it is important to honour the idiosyncratic worldviews that drive individual decisions to grow and learn. Nowaczek and Smale (Citation2010) suggest that profiling ecotourist requires identifying deeper needs beyond destinations and activities to define their travel expectation and experiences. Similarly, exploring hedonic experiences of river rafting, Arnould et al. (Citation1999) conclude that the effectiveness of such experiences requires preparing the participant’s mind to perceive nature as having symbolic meanings. Implicit meanings and symbolic desires are therefore key to understanding ecotourism behaviours. However, perhaps owing to the challenges in eliciting such meanings, there has been limited work focused on more deeply held values or spiritual convictions in ecotourism. Prior work investigating engagement in nature-based activities, for example, investigates psychological or physical needs, for example, escapism, health enhancement (Latorre et al., Citation2021), restoration and happiness (Almeida et al., Citation2014), adventure (Canniford & Shankar, Citation2013) or learning (Galley & Clifton, Citation2004), drawing on manifest data. Whilst these studies provide valuable insights, deeper, symbolic needs are largely unknown, particularly from non-WEIRD ecotourism perspectives.

With respect to ecotourism, people assign unique symbolic meanings to nature through their interactions with their environment, and that in turn stimulates their reactions towards nature (Kunchamboo et al., Citation2017). People confer symbolic meanings to objects, beyond simple denotative or instrumental use (Nasar, Citation1989). For example, Mount Kinabalu in Sabah, Malaysia, is sacred to the indigenous people, and is known as Aki Nabalu, a revered place of the dead. In 2015 a group of international tourists posed nude at the summit, posting the image on social media. Shortly thereafter a major earthquake resulted in damage and disruption. Local people felt the disrespectful act had angered the spirits of the mountain (The Straits Times, Citation2015). Similarly, in India, religious beliefs represent rivers as the goddesses Ganga and Yamuna (Ruback et al., Citation2008). Such animist and anthropomorphist views represent objects as human and alive, which then defines the observer’s relationship with that object (Boyer, Citation1996, p. 88). Thus, framing natural artefacts as ‘sacred’ places creates connotative meanings based on the emotions evoked. Exploring such framing offers insights into inner worlds as yet underexplored in ecotourism.

Nature-based tourism includes various forms such as ecotourism, adventure tourism and cultural tourism (Mehmetoglu, Citation2007). Valentine (Citation1992, p. 110) argues that activities can be placed on a continuum of nature-dependency ranging from dependent (e.g. bird watching), enhanced (e.g. camping in a forest) to incidental (e.g. swimming without a purely natural setting). This study focuses on nature-dependent activities, and is thus firmly positioned as ecotourism, whereby nature is central to the experience and environmental learning (Donohoe & Needham, Citation2006). Following Stronza et al. (Citation2019) we define ecotourism as ‘responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation and education’ (p. 230). Donohoe and Needham (Citation2006) identify six fundamental tenets driving ecotourism behaviour: nature-based; preservation/conservation; education; sustainability; distribution of benefits; and ethics/responsibility/awareness. The authors argue that the tenets are grounded in non-objective motivations and are community rather than individually centred. This research embraces an environmentally responsible tourism perspective, i.e. direct experiences and enjoyment of the natural environment with the intentions of conservation, education, recreation and adventure. We refer to ecotourists as those seeking benefits from experiencing ‘some undisturbed phenomenon of nature’ (Valentine, Citation1992, p. 108), while treating nature as an object of appreciation and a space to enhance environmental knowledge and affection, rather than a service consumption experience.

In ecotourism, symbolic desires motivate intentions to seek and experience nature, and influence evaluations of those experiences (Adam et al., Citation2019). Such experiences are both experiential and hedonic, resulting in high levels of engagement; both objective entity and subjective symbol, imbued with multisensory imagery, emotion and fantasy (Holbrook & Hirschman, Citation1982). Ecotourism, like experiences drawing on cultural products such as music and art, is a multi-sensory experience, giving rise to rich, layered impressions and images. Multisensory experiences may evoke recollection (historical imagery) and fanciful imaginings (fantasy), resulting in enhanced emotional responses such as love, fear, anxiety, guilt or awe and hence higher involvement and arousal (Hirschman & Holbrook, Citation1982). However, despite the obvious relevance of recollection, fantasy and symbolic desire to ecotourism experiences, work using non-verbal multisensory properties is rare in the ecotourism literature. While much is known about tourist motivations, knowledge about self-expressive meanings as the core motivational drivers to seek eco-adventures is limited (Adam et al., Citation2019). While the early studies identify motivational characteristics of ecotourist as ‘to experience and observe wild nature’, ‘engage in meaningful conservation activities’ and ‘desire for adventure’ (Eagles, Citation1992; Meric & Hunt, Citation1998), the current literature narrows to include physical (bodily well-being and health), emotional (inner well-being, happiness), personal (interaction with others) and personal development (learning of new skills) (Latorre et al., Citation2021). However, these goals are based on rational individual statements, whereas behaviour is also expressive of feelings (Shamir, Citation1991). Expressed intentions (e.g. enhancing physical or mental health) may originate from a fantasy of conquering nature or an emotional desire to enhance self-worth. To elicit these deep and nuanced understandings of ecotourist intentions towards nature engagement, we need to understand symbolic meaning. Individuals must be observed in context, i.e. in nature, in order to elicit subjective aspects of consciousness and gain access to thoughts, feelings, needs and beliefs. Through the lens of symbolic interactionism and by applying a grounded approach, this research demonstrates how to identify the implicit meanings that drive ecotourist needs to engage with nature.

Methodology

An ethnographic study conducted in Peninsular and East Malaysia explored the experiences, thoughts and feelings of nature-oriented ecotourists. First, we identified events organised by environmental NGOs in Malaysia through web search and social networks. The first author joined three nature-oriented organisations, the Selangor Waterfall Association, Malaysian Nature Society and the Kuala Lumpur Rotary Club. Within those groups the first author engaged in social networking with committee members and regular members. Relevant activities for the study were identified based on six criteria: (1) provided access to groups of highly engaged ecotourists; (2) are nature-dependent that is, involve direct nature experiences; (3) promotes environmental knowledge or skill, awareness or conservation efforts; (4) convenient time and duration; (5) affordable with limited funding; (6) doable on the basis of the first author’s physical and mental resources. 11 such activities were identified ().

Table 1. Schedule of participant observations by type, purpose and duration.

The first author immersed in the field for 17 months. Fitness levels improved whilst engaging in activities ranging from garden walks to mountain and river trekking. Within each activity, purposive sampling identified interviewees based on the following criteria: (1) actively engaged with nature through regular nature-related activities and/or through an environmental society; (2) above 18 years of age; and (3) willing to participate. The fieldwork thus captured a wide range of activities, from the sedate to the strenuous; and in settings ranging from the manicured to the mountainous. Participant observations were captured in 280 photographs and 35 pages of field notes. Initial observations generated memos, which in turn generated ideas about top-of mind associations, perceptions, emotions, values and beliefs associated with nature. These insights supported the development of the interview guide. 15 depth interviews of 60–120 min used projective techniques ().

Table 2. Research participants by demographic and behavioural attributes.

Participants ranged in age from 36 to 67, with an average age of 45.5 years. All were tertiary educated and mostly in professional, knowledge-intensive occupations. Of seven women and eight men, six were husband and wife couples. The interviews were conducted in English recorded and transcribed, capturing 326 pages of interview transcripts. Most participants were drawn from the nature-based activities, however, others were found through word-of-mouth and snowballing. Participants ranged from weekend hikers to environmental activists, and were encouraged to express their inner lives through conversation and art. This research adheres to the ethical principles outlined by the Monash University Human Research Ethic Committee (CF12/2497–2012001349) in conducting research. Ethics approval was obtained for both participant observation and interviews. Participants’ privacy and identity is protected through the use of pseudonyms. Only those who consented to participate in the study were contacted for an interview and observed during nature activities.

Data analysis

The principles of symbolic interactionism informed both fieldwork and data analysis (Benzies & Allen, Citation2001). That is, humans are social beings who create meaning intersubjectively; and that meaning, far from being objective, is socially constructed and can change over time (Creswell, Citation2007). This assumption shifts the view from focusing on behaviour alone to taking a behaviour-meanings focus (Gage, Citation1989). Data analysis took an inductive grounded theory approach, using constant comparative analysis to develop codes, categories and themes (Charmaz, Citation2006). The data analysis began with the observation data and memos which provided a starting point to capture participants’ responses and conversations while in nature to identify items of potential interest, such as top-of mind associations, views and perceptions of nature, emotions and values and beliefs associated with nature. This was followed by systematic coding of each data set of observations, interviews and visual data. This step enabled selecting and sorting data within-case coding for each data set. The data extracts were then collated for each code. Next, through between case analysis sub-themes and themes were developed. Finally, we produced reportage and data displays to evoke the research setting and participant action, seeking to represent rather than constitute others’ realities (Hammersley, Citation2013; Van Maanen, Citation2011). Field notes, interviews and projective techniques provided triangulation between observed and self-reported behaviour and thoughts, while addressing the call to combine various methods to understand the complexity of ecotourism (Shasha et al., Citation2020). Credibility of the findings is further enhanced through prolonged engagement of 17 months in the field, generating sufficient data leading to in-depth understanding of phenomenon being studied. Selection of diversified events in multiple sites allowed for the observation of variant groups of informants. Two coders independently interpreted the data to ensure the consistency of interpretation and reliability.

Findings and discussion

Nature was regarded by the participants as both a physical entity and a meaningful symbol depending on their level of involvement and emotional attachment. Four archetypes emerged, illustrating how multisensory imagery, emotional arousal and fantasy construct hedonic meanings for ecotourists.

Archetype 1: the champion: nature as trial

Recalling the mythic labours of Hercules, characterisation of nature as a powerful force encourages individuals to test their physical endurance and mental perseverance, pitting human strength against its perceived power and vastness. Individuals sought extraordinary nature experiences for intense pleasure and to break away from mundane reality. Nature-related risk-taking encourages self-reflection and self-evaluation, building positive perceptions of self (Sedikides, Citation1993). Harry [M40] reported that during rock climbing activities, ‘the ability to conquer a particular route’ deepened his sense of achievement. The motivation to climb Mt. Kinabalu was driven by the need for accomplishment and self-recognition, ‘this is the 9th time I have climbed the mountain’ [Fieldnotes, Mt.Kinabalu]. Conquering nature through masculinity and mastery connotes control over self and life.

Despite a desire to engage with nature, some were afraid of coming to harm, ‘to be cut out from the human world’ [Harry, M40]; ‘It was a struggle to climb … we need to be somewhere safe and warm’ [Fieldnotes, Mt.Kinabalu]. Some recalled encounters with ‘other beings’ reflecting animist beliefs, ‘In Sabah, something imitated my voice in the middle of the night … . They tell you about spirits and all that whether I like it or not I believe there is something’ [Prema, F67]. Fear functioned as both a hindrance and a motivator, ‘The risk of you falling is higher, you just have to calculate and be prepared to fall … . You have the feeling of scariness, nervous’ [Hasyim, M43]. Despite her past experience, Prema revisited the space to address her fear, ‘I always feel that I would go in and would say God will keep me safe and I will go in with a positive mind’. Some hikers engaged in rituals and adhered to taboos, ‘never curse the mountain … we said prayers, requested for permission’ [Fieldnote, Mt.Kinabalu]. Bandura (Citation1983) suggests that perceived inefficacy to deal with a situation brings forth feelings of fear and encourages avoidance behaviour. On the contrary, Prema’s fear of nature was used as a positive motivation for further engagement with nature and to overcome her respective inabilities to cope with nature. The intention to face uncertainties in nature symbolises a challenge to improve self, ‘a single mother voiced her experience of reaching the mountain summit boosted her confidence to face life hardship and sense of independence’ [Fieldnote, Mt Kinabalu].

The hedonic perspective acknowledges that respondents utilise painful experiences in nature to construct desired emotions and fantasies aiming to change existing undesired realities. Harry’s experience of trekking Mount Everest portrays a test of his capacity, ‘People who go up Everest plan it for all their life mentally … .Everest or K2 what differentiates them and those who make it and don’t is really very strong mental strength … I think physical strength is good for certain thing but if you talk about endurance or lasting the distance'. Similarly, irrespective of age, the river trekkers scrambled over rough, slippery trails, eschewing assistance in challenging spots to prove self-efficacy ().

Such acts negate threats, address fears; accepting risk and pain in order to put both mind and body to the test (Cova et al., Citation2018). The rewarding experience of engaging in thrilling nature activities leads to self-renewal and strengthening of sense of self (Arnould & Price, Citation1993). Participants purge their anxiety and fear by ‘stepping out of one’s skin’ to resemble the need to discover the truth of oneself (Cova et al., Citation2018, p. 454), indicating that hedonic consumption can be both positively and negatively valenced.

Archetype 2: the adherent: nature as guru

While The Champion attempts to conquer nature to enhance self-efficacy, The Adherent synchronises with nature to gain aspirational qualities such as calmness, forgiveness and purity and intelligence, aspiring ‘flawless’ human characteristics. Participants wished to attain similar qualities. For example, Vani eschewed the comforts of home to trek Mt. Kinabalu, ‘You discipline yourself and conquer yourself … You become more patient, tolerant’ [Vani, F43]. Sudesh viewed nature as a vessel of knowledge, a wise teacher, ‘There is so much to learn from nature, nature is more capable than man, self-sufficient and smarter’ [Sudesh, M43] ().

Learning through sight, smell and sound enhanced engagement with botanical elements. Participants expressed perceived inadequacies, and a desire to progress towards an idealised self-image and a new authentic self; one that is embedded in beliefs, values, views and feelings (Leary, Citation2003) through connecting soul, body and mind. Finding an authentic self is an attempt to realise the inherent characteristics, actual beliefs and values which individuals were initially unaware of (Petersen, Citation2011). Ahuvia (Citation2005) suggests the existence of an authentic inner core self and each individual’s need to discover his or her true self. That is, individuals strive to understand their self, develop self-awareness and struggle to maintain a consistent self. For example, Sam [M46] notes that ‘this experience changed the perception about myself … I am stronger than I thought’, indicate a move towards self-discovery, awareness and an attempt to find a genuine self and to achieve a stronger self-identity. Past research highlight the use of consumption objects for self-expression and reconstruction of self-identity (Ahuvia, Citation2005; Belk, Citation1988). Within the context of nature experiences, natural properties were used as a purifying medium, ‘The sea breeze I feel it cleanses away stress, all these things inside me, it just takes away’ (Sam, M46). Sam is expressing symbolic desires of self-discovery, self-transformation and harmony between mind and body, emblematic of the adherent archetype.

Archetype 3: the acolyte: nature as God

Fascination with nature, which refers to the quality of attention, is found to play a key role in building stronger nature engagement (Sato & Conner, Citation2013). Experiencing the wonders of nature beyond a person’s imagination or understanding leads to the impression of greatness, divinity and mystery. Multisensory experiences such as observing a waterfall gave rise to expression of spiritual and religious thoughts, feelings of being close to God or being overwhelmed with the power of nature. Nature was thus conferred with supernatural and spiritual power, leading to a comparison of self as a small and powerless being, ‘The feeling is you feel very small … very insignificant in this world compared to something so majestic and beautiful’ [Hasyim M43]. Belk and Costa (Citation1998) argue that experiencing sacred nature prompts nature worship. Spirituality may result from connecting with elements such as a tree (nature-based spirituality), experiencing nature as God’s creation (religious spirituality) or by admiring the power or greatness of the universe (cosmic spirituality) (Worthington & Aten, Citation2009). Religious beliefs may support symbolic meanings by aligning nature to God; exemplifying the sacred aspects of nature, generating imagery of a creator’s creations, and deep thoughts of humans’ place in the web of life, ‘When I am on top of the mountain, I feel I am being closer to God … It has always been the culture of human being looking for the supreme being up’ [Mahesh, M43]. Such imaginings express the symbolic desire to be closer to God or transcend self, representing a need to escape from realities of the physical world or life’s struggles, or to gain power by association with a more powerful entity.

Archetype 4: the spa-goer: nature as well-being resource

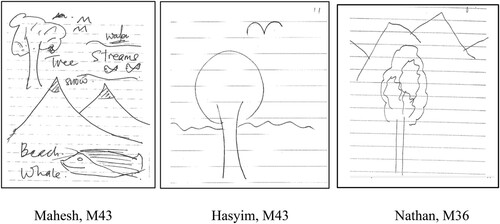

Participants associated nature with trees, rivers and mountains rather than animals or humans ().

Figure 3. Drawings of participant depictions of their perceptions of nature.

In general, participants viewed nature as an untouched wilderness where human rejuvenate and seek pleasure. The immediate expression of nature was focused on trees and greenery, ‘Of course I wanted to draw plenty of trees’ [Sam, M46]. The colour green symbolises life, thus trees represented the key measure of health for nature, ‘Green means forest, hills, different shades of green’ [Rasyhid, M59]. Participants’ drawings reveal strong associations with serenity and beauty, a ‘cool calm feeling … peace and tranquillity’ [Nathan, M3]. The colours, elements of nature, sceneries from nature and associations represent hedonic perspectives drawn from multisensory images from past experiences and fantasy imagery, ‘Beautiful landscape, mountains with snow cap. You don’t hear any sound. Total silence. I only hear wind blowing, I felt like my god such kind of place exist’ (Sam, M46). Moreover, the participants’ representations of nature were external to self, objectified, and devoid of human influence. We interpreted this disassociation with humans as a fantasy of perfection, and perhaps avoidance of a sense of guilt at despoilment, ‘Stream is basically water … the purity of the water, like those days we drink the water from the stream. So clean … so transparent, which we don’t see it anymore’ [Mahesh M43].

While some participants sought nature as a space to eliminate loneliness by seeking like-minded friends, others regarded nature as a companion. Keshita and Sudesh emotionally bonded with a tree, anthropomorphising the tree as part of their circle of relatives and friends, ‘You kind of feel there is someone there (refers to tree) who is silent who kind of gives you different perspective of life you shouldn’t be too upset about things you know’ [Keshita, F40]; ‘The tree is like a sibling’ [Sudesh, M41]. For Keshita, nature was a companion or a wise person, with patience to listen. Keshita’s imagery is guided by culturally driven beliefs of animism that ascribes nature as having human personality and attributes, ‘She (nature) always come across as very patient’, ‘mountains could hear and speak’ [Keshita, F40]. Thus, nature can express wisdom and embodies the qualities of a mother or friend such as trustworthiness, dependability and the ability to listen. Sudesh [M41] fantasises the tree outside his home as a companion, ‘Every afternoon after school I will be on the tree. I don’t know why I will be up there’. At a subconscious level the tree provided a sense of security, an enduring presence. Thus, the motivation was to enhance physical and psychological well-being,

You go to seaside sit on the beach, look at the waves, how nice it is, even more nice is see one or two fishing boats coming in … honestly if you continue to do this, you probably won’t have blood pressure or stress. [Rasyhid, M59]

Implications and conclusions

The ecotourism archetypes demonstrate the potential of symbolic interactionist approaches to uncover deeply held attitudes and beliefs (). Ittelson et al. (Citation1976) illustrate five ways to experience the environment, that is as ‘external physical place’ (detached from self), ‘self’ (as total or part of self), ‘social system’ (a place to socialise), ‘emotional territory’ (association or attachment) and ‘setting of action’ (environment experienced as a setting within which action is performed). Our findings extend this knowledge within the context of experiencing the natural environment by classifying four ecotourist archetypes, highlighting ways of experiencing nature and the perceived benefits, an outcome of deep-symbolic meaning making. The ‘Champions’ view nature as a challenging trial, experiencing nature as space to master challenges, acquire new skills and gain self-enhancement. Perceiving nature as wise with wisdom, to the ‘Adherents’, being in nature is a learning experience assisting self-reflection and finding their possible desired-self. While the ‘Spa-goer’ view nature as a source of wellbeing and engage with nature for personal benefits including enjoyment, psychological and health, the ‘Acolyte’ associate nature with supernatural power seeking religious and spiritual experience.

The findings from this study challenges fundamental predisposition in previous studies about the motives of ecotourist, extending beyond destinations, activities and behaviour (Nowaczek & Smale, Citation2010). We uncover hedonic needs that support tourist value-belief system, desires, and motives to engage in nature experiences. The archetypes describe the imaginative aspects of reality originating from the multisensory imagery, fantasy and emotional arousal, segmenting ecotourists based on the symbolic meanings that guide their information processing and decision making. While past research mainly highlights rational benefits ecotourist seek from nature engagement, our findings detail the unconscious aspects; the repressed desires that function as the core-motivation, answering the research question: ‘Why do ecotourists seek out nature-based experiences?’.

Participants expressed their inner worlds through metaphor, art, fantasies and imagery, highlighting that symbolic consumption is inseparable from the self, and from personal meaning-making around life aspirations, situations and desired identities. The finding refutes Sharpley’s (Citation2006) argument on ecotourist motivations by distinguishing symbolic meanings driving ecotourism. The findings extend ecotourism research by highlighting the role of personal meanings as drivers of nature engagement; multi-sensory aspects of nature consumption; and imagery and emotions linked to experiential consumption. The research shows the potential of symbolic meanings to transform perspectives of ecotourist behaviour, and also to provide deeper insight into tourist thoughts and perceptions.

Additionally, we highlight shortfalls in current ecotourism insights resulting from reliance on data collected from mainly WEIRD contexts, challenging Western belief structures (Shasha et al., Citation2020). Asian cultural values, religious teachings and beliefs such as animism serve as motives that guides intentions to engage with nature. By drawing on non-WEIRD data, the role of religiosity beyond Judeo-Christian traditions is highlighted, giving insight into views of nature other than those derived from an innate sense of dominion. Animism beliefs of nature as a being that is alive, with human roles and characteristics, bridges similarity between self and nature, forming the desire to associate (Aron et al., Citation1991).

For ecotourism practitioners, the archetypes suggest a benefit segmentation scheme, allowing for developing marketing strategy and more meaningful consumer experiences. Previous attempts to segment the market for ecotourism are evident along product, geographical location, activities and market with minimum application of implicit meanings of socio-psychological approach (Weaver & Laura, Citation2007). With respect to marketing messaging, it is essential to explore implicit brand meanings around the archetypal characteristics (trial, learning, purification, spirituality) in order to create resonance for consumers (Berthon et al., Citation2009); supporting more effective targeting and value proposition development for ecotourism products and services. For example, smelling the roses in a botanic garden may connote emotional grounding (The Spa-Goer), action shots of white water rafting connotes mastery and self-control (The Champion), mountain hiking may attract those seeking spiritual experiences (The Acolyte), while eco-training would appeal to those wanting to express and strengthen their ecological identity (The Adherent). Deep understanding of ecotourist imagination, fantasies, and emotions relating to nature can support more effective consumer targeting, relationships, brand positioning and communication. Future research may differentiate the hedonic needs of active ecotourists (those engaging in high-risk nature adventures) from passive ecotourists (those engaging in less risky activities). A common approach to segment the ecotourist market involves socio-demographic segmentation (Almeida et al., Citation2014). Future research may attempt to further refine the needs of various demographic groups by exploring personal meanings that drive their nature engagement. The emotions, views and thoughts of nature as presented in this research illustrate the ‘hidden’ needs as aspired by ecotourist. The knowledge of these fantasies, imagery and emotions provides a basis for a deep and nuanced understandings of ecotourist intentions towards nature engagement.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (176.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adam, I., Adongo, A. C., & Amuquandoh, F. E. (2019). A structural decompositional analysis of eco-visitors’ motivations, satisfaction and post-purchase behaviour. Journal of Ecotourism, 18(1), 60–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2017.1380657

- Ahuvia, A. C. (2005). Beyond the extended self: Loved objects and consumers’ identity narratives. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(1), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1086/429607

- Almeida, A. M. M., Correia, A., & Pimpão, A. (2014). Segmentation by benefits sought: The case of rural tourism in Madeira. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(9), 813–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.768605

- Arnould, E. J., & Price, L. L. (1993). River magic: Extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 24–45. https://doi.org/10.1086/209331

- Arnould, E. J., Price, L. L., & Otnes, C. (1999). Making magic consumption: A study of white-water river rafting. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 28(1), 33–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124199129023361

- Aron, A., Aron, E. N., Tudor, M., & Nelson, G. (1991). Close relationships as including other in the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.2.241

- Bandura, A. (1983). Self-efficacy determinants of anticipated fears and calamities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 2. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.464

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

- Belk, R. W., & Costa, J. A. (1998). The mountain man myth: A contemporary consuming fantasy. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 218–240. https://doi.org/10.1086/209536

- Benzies, K. M., & Allen, M. N. (2001). Symbolic interactionism as a theoretical perspective for multiple method research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33(4), 541–547. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01680.x

- Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., & Kaplan, S. (2008). The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1207–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02225.x

- Berthon, P., Pitt, L. F., & Campbell, C. (2009). Does brand meaning exist in similarity or singularity? Journal of Business Research, 62(3), 356–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.015

- Bertram, C., & Rehdanz, K. (2015). The role of urban green space for human well-being. Ecological Economics, 120, 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.10.013

- Blumer, H. (1998). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. University of California Press.

- Boyer, P. (1996). What makes anthropomorphism natural: Intuitive ontology and cultural representations. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 2(1), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/3034634

- Canniford, R., & Shankar, A. (2013). Purifying practices: How consumers assemble romantic experiences of nature. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(5), 1051–1069. https://doi.org/10.1086/667202

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. SAGE.

- Cova, B., Carù, A., & Cayla, J. (2018). Re-conceptualizing escape in consumer research. Qualitative Market Research, 21(4), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-01-2017-0030

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Donoghue, S. (2000). Projective techniques in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Sciences, 28. doi:10.4314/jfecs.v28i1.52784

- Donohoe, H. M., & Needham, R. D. (2006). Ecotourism: The evolving contemporary definition. Journal of Ecotourism, 5(3), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.2167/joe152.0

- Eagles, P. F. (1992). The travel motivations of Canadian ecotourists. Journal of Travel Research, 31(2), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759203100201

- Fletcher, R. (2009). Ecotourism discourse: Challenging the stakeholders theory. Journal of Ecotourism, 8(3), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040902767245

- Gage, N. L. (1989). The paradigm wars and their aftermath: A “historical” sketch of research on teaching since 1989. Educational Researcher, 18(7), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/1177163

- Galley, G., & Clifton, J. (2004). The motivational and demographic characteristics of research ecotourists: Operation Wallacea volunteers in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Journal of Ecotourism, 3(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040408668150

- Hammersley, M. (2013). What's wrong with ethnography? Routledge.

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

- Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1982). Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. Journal of Marketing, 46(3), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298204600314

- Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and Fun. The Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1086/208906

- Ittelson, W. H., Franck, K. A., & O’Hanlon, T. J. (1976). The nature of environmental experience. In Experiencing the environment (pp. 187–206). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Jamaliah, M. M., Powell, R. B., & Sirima, A. (2021). Climate change adaptation and implementation barriers: A qualitative exploration of managers of Dana biosphere reserve–ecotourism system. Journal of Ecotourism, 20(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2020.1746320

- Kunchamboo, V., Lee, C. K. C., & Brace-Govan, J. (2021). Cultivating Nature Identity and Ecological Worldviews: A Pathway to Alter the Prevailing Dominant Social Paradigm. Journal of Macromarketing. doi:10.1177/0276146721997540

- Kunchamboo, V., Lee, C. K. C., & Brace-Govan, J. (2017). Nature as extended-self: Sacred nature relationship and implications for responsible consumption behaviour. Journal of Business Research, 74, 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.023

- Latorre, J., de Frutos, P., de-Magistris, T., & Martinez-Peña, F. (2021). Segmenting tourists by their motivation for an innovative tourism product: Mycotourism. Journal of Ecotourism, 20(4), 311–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2021.1892123

- Leary, M. R. (2003). Interpersonal aspects of optimal self-esteem and the authentic self. Psychological Inquiry, 14(1), 52–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/1449041

- Mathews, C., Ambroise, L., & Brignier, J. M. (2009). Hedonic and symbolic consumption perceived values: opportunities for innovators and designers in the fields of brand and product design. Renaissance & Renewal in Management Studies. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00654731/document

- Mehmetoglu, M. (2007). Nature-based tourism: A contrast to everyday life. Journal of Ecotourism, 6(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.2167/joe168.0

- Meric, H. J., & Hunt, J. (1998). Ecotourists’ motivational and demographic characteristics: A case of North Carolina travellers. Journal of Travel Research, 36(4), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759803600407

- Morris, L., & Schmolze, R. (2006). Consumer archetypes: A new approach to developing consumer understanding frameworks. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(3), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0021849906060284

- Nasar, J. L. (1989). Symbolic meanings of house styles. Environment and Behavior, 21(3), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916589213001

- Nowaczek, A., & Smale, B. (2010). Exploring the predisposition of travellers to qualify as ecotourists: The ecotourist predisposition scale. Journal of Ecotourism, 9(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040902883521

- Petersen, A. (2011). Authentic self-realization and depression. International Sociology, 26(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580910380980

- Ruback, B. R., Pandey, J., & Kohli, N. (2008). Evaluations of a sacred place: Role and religious belief at the Magh Mela. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(2), 174–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.10.007

- Sato, I., & Conner, T. (2013). The quality of time in nature: How fascination explains and enhances the relationship between nature experiences and daily affect. Ecopsychology, 5(3), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2013.0026

- Sedikides, C. (1993). Assessment, enhancement, and verification determinants of the self-evaluation process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 317–338. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.317

- Shamir, B. (1991). Meaning, self and motivation in organizations. Organization Studies, 12(3), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069101200304

- Sharpley, R. (2006). Ecotourism: A consumption perspective. Journal of Ecotourism, 5(1-2), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040608668444

- Shasha, Z. T., Geng, Y., Sun, H. P., Musakwa, W., & Sun, L. (2020). Past, current, and future perspectives on eco-tourism: A bibliometric review between 2001 and 2018. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(19), 23514–23528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08584-9

- Spano, G., Dadvand, P., & Sanesi, G. (2021). The benefits of nature-based solutions to psychological health. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(1), 193–196. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646627

- Stronza, A. L., Hunt, C. A., & Fitzgerald, L. A. (2019). Ecotourism for conservation? Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 44(1), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-101718-033046

- Tabaeeian, R. A., Yazdi, A., Mokhtari, N., & Khoshfetrat, A. (2022). Host-tourist interaction, revisit intention and memorable tourism experience through relationship quality and perceived service quality in ecotourism. Journal of Ecotourism, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2022.2046759

- The Straits Times. (2015, June 7). Sabah quake: 2 Canadian tourists who stripped on Mt Kinabalu barred from leaving Malaysia. http://www.straitstimes.com/ news/asia/south-east-asia/story/sabah-quake-2-canadian-tourists-who-stripped-mt-kinabalu

- Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R. F., Losito, B. D., Fiorito, E., Miles, M. A., & Zelson, M. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11(3), 201–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7

- Valentine, P. (1992). Review: Nature-based tourism. In B. Weiler & C. M. Hall (Eds.), Special interest tourism (pp. 105–127). Belhaven Press.

- Van Maanen, J. (2011). Ethnography as work: Some rules of engagement. Journal of Management Studies, 48(1), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00980.x

- Wearing, S., Cynn, S., Ponting, J., & McDonald, M. (2002). Converting environmental concern into ecotourism purchases: A qualitative evaluation of International backpackers in Australia. Journal of Ecotourism, 1(2-3), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040208668120

- Weaver, D. B., & Lawton, L. J. (2007). Twenty years on: The state of contemporary ecotourism research. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1168–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.03.004

- Worthington, E. L., & Aten, J. D. (2009). Psychotherapy with religious and spiritual clients: An introduction. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20561