ABSTRACT

Nature-based activities have become business constituents of increasing importance in the tourism industry. In this paper, trends in nature-based tourism with the largest commercial potentials are identified by means of surveys with 60 experts in five different countries/regions with a renowned nature-based tourism sector, collected in three rounds based on Delphi methodology. Results show that the trend categories with the highest impact on commercial opportunities within the next 10 years are related to health, sustainability, soft adventure, digitalization, and professionalization. The ability to recognize and deal with such prospects is a key element of an economically successful, but also environmental and socially sustainable nature-based tourism industry. Thus, the identified developments are of crucial importance to business managers, policymakers, managers of nature areas, and planning authorities.

Introduction

Contemporary tourism is driven by pervasive social, technological, economic, environmental and political transformations: increasing urbanization, population growth, climate change, economic development, altered distributions of wealth, changing work patterns, new technologies, political conflicts, and pandemics to mention some of the key parameters that influence tourists’ choices regarding where to travel, what to do, for how long, and at what price (Benckendorff, Citation2006; Buckley et al., Citation2015; Dwyer et al., Citation2008; Elmahdy et al., Citation2017; Haukeland et al., Citation2021; Scott & Gössling, Citation2015). One outcome of these grand scale processes is that the nature-based tourism (NBT) sector has developed rapidly, until the extraordinary situation in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic when the demand for visits to nature have risen dramatically and taken several new routes (Derks et al., Citation2020; Ferguson et al., Citation2022; Venter et al., Citation2020).

Nature-based tourism involves a large number of different outdoor activities, such as hiking, backpacking, skiing, boating, camping, angling, hunting, kayaking, and biking – many of which are performed by individuals, families and friends with only minor involvement of commercial operators (Margaryan & Fredman, Citation2017). Several of these activities are, however, nowadays increasingly diversified and specialized propelled by online technology, better equipment, and a more professional service delivery. These factors, in combination with an increasing purchasing power and a thriving outdoor retail industry, creates new business opportunities within the NBT sector. In the tourism sector in general, there is a ‘constant search for new avenues of involving nature in tourism’ (Margaryan, Citation2018, p. 1894), leading to an increasingly sophisticated NBT sector that can support regional economies (Kronenberg & Fuchs, Citation2021; Rinne & Saastamoinen, Citation2005), especially in rural areas where most of the NBT firms are operating. For example, studies in Sweden and Norway have identified approximately 3000 NBT service providers in each country respectively (Fredman & Margaryan, Citation2014; Stensland et al., Citation2018), most of which are small but expect further expansion of their businesses reflecting a dynamic and creative economic sector with a potential to play a major role in future rural development through a varied supply of services (Fuchs et al., Citation2021; Stensland et al., Citation2021).

Thus, becoming increasingly diverse and specialized with demands for higher quality standards, NBT is established as an important business sector with additional growth potential in many countries and regions (Bell et al., Citation2008; Fredman & Margaryan, Citation2014; Siegrist et al., Citation2015; Stensland et al., Citation2018). The sustainable development of NBT is, however, hampered in part by a fragmented and inadequate state of knowledge about this highly multi-facetted sector (Fredman & Margaryan, Citation2020; Tyrväinen et al., Citation2018). The growth in demand, the increased variation in customer expectations and the changing management targets for the underlying natural and cultural resources call for a comprehensive understanding of key trends and anticipated changes. This kind of knowledge is essential also for the tourism industry’s contribution to achieving the global sustainability goals (Spenceley & Rylance, Citation2019).

One way of studying the dynamism of an economic sector is to identify and understand its prominent trends as they reveal the direction in which the sector is developing or changing and how people are behaving in relevant contexts. Such knowledge will impact the prospects for sustainable development and growth for various reasons. Firstly, firms may adjust existing provisions or improve their business supply when they know more about their customers’ preferences, market dynamics and competing activities. Businesses can capture the business opportunities that best fit their own skills, local resources, and location. The ability to identify and handle such changes is therefore a key element of a successful tourism industry (Bowen & Whalen, Citation2017; Buckley et al., Citation2015; Dwyer et al., Citation2008; von Bergner & Lohmann, Citation2014). Secondly, tourism in natural areas can have serious negative effects on the environment, such as climate gas emissions, unsustainable land use in terms of overuse of specific sites, conflicts over the use of natural resources, and loss of biodiversity (Breiby et al., Citation2021; Hammitt et al., Citation2015). The changes in volume and structure of the sector also influence local communities directly, both positively and negatively (Lindberg et al., Citation2021). Trends in NBT are thus of crucial importance to policymakers, business developers, managers of nature areas and planning authorities, as they directly influence the whole spectrum of sustainability issues, critical to tourism policy and planning processes (Dredge & Jenkins, Citation2011).

Aim, objective, and study areas

The aim of this study is to analyze prospects of NBT through identifying trends with commercial potentials. The objective is to better understand how future development of NBT can add value to businesses, local communities, and regions. While small and medium-sized firms are the primary entity generating commercial values, success in the NBT sector is typically dependent on both private and public resources (Lundberg & Fredman, Citation2012; Stensland et al., Citation2021). Many of the NBT activities also has a history of being ‘self-propelled’ and/or provided ‘free of charge’ through non-profit organizations. This calls for a multi-disciplinary approach to better understand the commercial prospects of such a multifaceted sector operating under changing social and environmental conditions (Fredman & Tyrväinen, Citation2010).

We approach the topic using the Delphi technique including experts with professional backgrounds related to NBT from Norway, Sweden, Finland, the European Alps, and the western United States. These five countries/ regions have many features in common in terms of easy access to natural resources available for NBT, encompassing forests, waters and mountainous terrain as well as designated opportunities for winter sports. The three Nordic countries have developed strong outdoor recreation traditions based on free access to nature areas (legal rights of public access), the European Alps have a long-lasting and influential tradition of alpine sports, and many trends are considered to have their origin in the Western US, spreading to Europe, as mountain biking did in the 80s (Fredman & Haukeland, Citation2021; Gartner & Lime, Citation2000; Siegrist et al., Citation2015; White et al., Citation2016). Moreover, growing populations in these five entities possess the interest and financial resources to engage in NBT activities on a commercial basis, in addition to tourists visiting these regions for nature experiences.

The Delphi method

The Delphi method is an exploratory qualitative research method that involves soliciting opinions from experts in several consecutive questionnaires with controlled feedback (Landeta, Citation2006; Linstone & Turoff, Citation2002). This method is well suited for complex problems involving uncertainty, such as studies of the future. Previous applications of the Delphi method in tourism research include ecotourism (Donohoe, Citation2011), challenges to global tourism (von Bergner & Lohmann, Citation2014), indicators of sustainable tourism (Miller, Citation2001), future transport (Weston & Nicholas, Citation2007), and product development (Konu, Citation2015).

The first, and perhaps most crucial step of the Delphi approach is to identify a group of people with expertise in the subject, covering different perspectives of relevance to the research task. This was done through purposive sampling based on the literature review of previous Delphi studies in the tourism field (see above) and discussions within the research team until consensus was reached to include experts with a background in the following 10 topic-areas: (i) national or regional government/ministries; (ii) regional tourism associations, destinations or municipalities, (iii) tourism marketing organizations, (iv) nature-based tourism companies or associations, (v) outdoor industry (equipment, clothing), (iv) outdoor recreation or other non-profit organizations, (vii) organizations managing facilities, natural resources and/or areas used for NBT, (viii) academia or consultants, (ix) media (with special interest in tourism and/or outdoor recreation), and (x) youth organizations (with special interest in tourism and/or outdoor recreation). With this approach, we include a range of experts covering objective closeness (NBT tourism specialists), mandated closeness (NBT influences) as well as subjective closeness (other NBT tourism interests) to the topic of the study (Konu, Citation2015). This mixture of expertise provides a solid basis for a study of trends in NBT with focus on commercial potentials.

Experts were invited by members of the research team in each country respectively. There were two experts invited in each topic area from Norway and Sweden, while the other three countries had one expert invited in each area.Footnote1 Altogether, 73 experts were invited to participate in the study (see ). To provide a common understanding among the experts about key terms used in the study following definitions were conveyed:

Table 1. Number of invited experts, responses, and response rate round 3.

Nature-based tourism: people visiting natural areas outside one’s ordinary place of residence.

Nature-based tourism businesses: companies and organizations that receive payment for providing goods and services in support of NBT (guiding, transportation, equipment sale or rental, lodging, etc.).

Trend: a general direction in which something is developing, changing or people are behaving

Drivers: internal or external factors that may affect trends.

Survey design

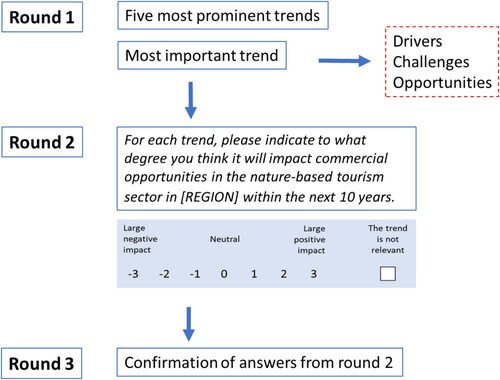

The panel of experts received three rounds of questions: one initial round with open-ended questions (round 1) and two following (round 2 and 3) with close-ended, Likert scale questions ().

Figure 1. A flowchart illustrating the Delphi survey design with three rounds; including the phrasing used for the questionnaire in the second round along with the 7-point Likert-type response scale.

The purpose of round 1 was to give experts an ‘open space’ to provide their thoughts on the topics for the survey with minimal impact from the survey instrument. This round therefore operated with open-ended questions where experts formulated the trends with their own words. Each expert was allowed to report up to five trends (within a 10-year time horizon) and one of the trends was ranked as the most prominent. For this trend, each expert also described (in written text) the drivers that might impact the trend, as well as the main challenges and opportunities for NBT due to the trend in each country respectively.

Next, the research team did a content analysis of the written trend descriptions provided from the experts in round 1. Each answer was reviewed and categorized as a trend in a format appropriate for the evaluations in the second and third round of the survey. Since several of the descriptions provided in round 1 covered comparable topics, a total of 36 explicit trends were identified in this stage of the study. These trends were all included in the second and third round of the Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish and European Alps surveys. However, not all trends were judged to be appropriate to the North American context, so for this survey 20 trends were brought forward to round 2 and 3 (see the Appendix).

In the second round of the survey, each trend was rated by the experts on a seven-point scale with respect to commercial opportunities in the NBT sector in each country respectively (such as charging for guided tours, overnights stay, renting equipment, supply services, etc.). This round was completed by 63 experts (). A key feature of the Delphi approach is to identify convergence of opinions across experts and questions; round 3, therefore, repeated the same questions that were asked in round 2, but now with information about the answers given in round 2. This information included (for each question) both the individual responses given by the expert and the average responses across all the experts in each country respectively. Respondents could thus see how their answers compared with those of other experts, with the opportunity to revise their answers in response to this information.

Table 2. Top-rated trends in round 3 of the Delphi study. Mean scores based on 7-point scale: −3 (large negative) to 3 (large positive) impact on commercial opportunities in the NBT sector within the next 10 years.

The three rounds of surveys were conducted between March 2017 and July 2018. In each round, up to four reminders were sent out. The survey was conducted in English, but some participants preferred to respond in their native language (in which case the answers were translated to English by the research team). As shown in , the final response rate varied between 70% (western USA) and 90% (Sweden and Finland), which resulted in 60 completed surveys after the third and final round.

In the following section, we present the results from the third and final round of the survey (where the focus was on commercial opportunities), supplemented with quotes from the open-ended questions about drivers, challenges and opportunities associated with the trends asked for in the first round.

Results

presents those trends from the third round of the survey that were ranked among the top ten in at least three of the five countries/ regions with regards to their commercial potential. For example, the trend ‘Physical activities in nature for health and fitness’ were among the top ten rated trends in all countries/ regions, whereas the trend ‘Experience local culture and locally produced products, food, etc.’ was rated among top ten in four of the five countries/ regions.

The eight trends presented in are further grouped into five trend categories (right column) according to their thematic interlinkages: The category Sustainability is a cluster of the three trends ‘Sustainability and responsible travel’, ‘Experience local culture and locally produced products, food, etc.’, and ‘Authentic nature and culture experiences’. These clearly express core sustainability issues, with emphasis on beneficial local impacts, low footprints from travel activities and search for authenticity. The second category, Health, includes the two trends ‘Physical activities in nature for health and fitness’ and ‘Health and wellbeing from nature experiences’, which are both directly connected to the physical and psychological health benefits from participation in outdoor recreation activities. The trend ‘Simple and easily accessible activities (soft adventure)’ is a category of its own which we for further description coin Soft adventure representing low-threshold and simple outdoor recreation activities. The final two categories, Digitalization and Professionalization, represent ‘Digital marketing, trip planning and booking’ and ‘Commercial guided services or courses in nature’ respectively. The five trend categories are not necessarily mutually exclusive. The two latter trends, for example, mirror ongoing movements toward specialization and technification of the nature-based tourism sector which are closely interlinked with trends in the three first categories (as illustrated below).

Sustainability

The trend ‘Sustainability and responsible travel’ reflects a desire to travel in eco-friendly ways to minimize environmental impact and carbon footprint. It scored high in all three Nordic countries. Principles of ecotourism are mentioned as important criteria, and sustainable businesses and destinations are sought. Experts underline that NBT firms now understand their market segments better, and with that follows increased focus on sustainability and responsibility regarding nature and local cultures. One of the experts from Norway noticed that: ‘The increased pressure on natural resources will require activities organized in harmony with nature’. Key drivers behind this trend are consumer demand and travelers’ feeling of responsibility. Political support for sustainability practices was also mentioned. Improved economic conditions for NBT enterprises were seen to support development of sustainability practices.

The trend ‘Authentic nature and culture’ reflects that authenticity is a basis of many NBT products, which means a close connection to cultural values as well as to the local place or a region. It underlines distinctiveness and peculiarity, as illustrated by this quote by an expert from the western USA: ‘I see people moving away from ski lifts for example and exploring the back-country’. Authentic tour products also strive for authentic contact with the local population and culture. This trend has much in common with the following trend about local culture and products, but the emphasis here is on the concept authenticity and has a stronger orientation toward the natural component. One expert from Sweden expressed it as: ‘Longing for authenticity drives demand for natural environments and untouched nature’.

The trend ‘Experience local culture and locally produced products, food, etc.’ is particularly strong in Norway and Sweden. It expresses a growing interest in history and culture, including contact with small-scale farming, traditional and local food and drink, and traditional cultural landscapes. The importance of Scandinavian design and authentic, environment friendly experiences were also underlined. One of the experts from Sweden emphasized how ‘awareness’ of money contribute to local and rural development: ‘There is a willingness to pay extra for local food, for the ‘exclusive’ experience of participating in ‘back-stage’ activities’.

Health

‘Physical activities in nature for health and fitness’ is ranked among the top ten in all five countries. A closer look at the underlying descriptions of this trend from the first round reveals that nature is seen as an ever more important location for various physical activities such as kayaking, hiking, hill running, skiing, and climbing. A diversion from a stressful everyday life, with physical NBT activities in relative pristine natural surroundings with plenty of peace and quiet, is seen as health rewarding in both physical and mental terms. The natural healing effects were described by one expert from Norway: ‘Focus on health, strength, inner calmness, relaxation and organic and natural food is making us value nature even more’. Another Norwegian expert noted: ‘Health, strength, thrill and nature experiences makes up the perfect “combo” for the adventure seeking modern man and woman’. Important drivers include opportunities offered by digitalization and new technologies, such as heart rate monitors and other mobile devices and apps available to measure personal health status changes during the activity. This was mentioned also among the Finnish experts, who overall rated this trend to have the highest commercial potential among all trends.

The trend ‘Health and wellbeing from nature experiences’ and associated drivers coincide with the previous trend about physical activities, but the scope seems to be broader. Illustrated by one of the experts from the western USA: ‘World population grows, people are forced more into cities for their livelihood and thus more people will want to escape to the natural world for rest and rejuvenation’. The commercial potential of this trend is notably more emphasized in Finland compared with Norway and Sweden.

Soft adventure

The experts rated soft adventures in terms of simple and easily accessible activities as a trend with high commercial potential. Scores by experts from Norway, Sweden and Finland are particularly high for this trend. Several of the experts explained that an increased demand from less experienced visitors, often with an urban background, to natural areas call for ‘soft’ adventure products suitable also for those with little previous knowledge and experience. One of the Norwegian experts emphasize the ‘huge growth potential in tourism businesses’ by making ‘more wild nature accessible’, reflecting the potential to add commercial values to basic outdoor recreation activities, traditionally being self-propelled.

Digitalization

The trend ‘Digital marketing, trip planning and booking’ has become a game-changer for many NBT products, as noted by an expert from the western USA:

Technology (smartphones, social media platforms) and the reliance on technology will increasingly change how people identify where to recreate, how they engage with natural resources, their expectations for technology services provided on-site, and how they share their experiences with others.

Professionalization

Descriptions of the trend ‘Commercial guided services or courses in nature’ focused on increasing interest in professional, well-informed guiding services. The willingness to pay for such skills is expected to continue to grow, one example being a growing interest for guided tours and courses ensuring safe travel in difficult terrain that requires high-tech equipment, special expertise, or both. Associated drivers are an increased demand for guided nature experiences in a more urbanized world, where people lack the necessary skills. For example, to access exotic environments or when performing activities in other seasons than the summer. One of the Norwegian experts expressed it as follows: ‘Give people good, relevant and tempting information that lowers the friction’. This trend scores particularly high among experts in both Norway and Sweden.

Discussion

In this study we reveal trends in nature-based tourism with commercial potentials based on data from experts in five different countries/ regions renowned by their NBT opportunities. Such knowledge can support strategic planning and management of the NBT supply across stakeholders in the private and public sectors (Dredge & Jenkins, Citation2011; von Bergner & Lohmann, Citation2014) adding value to businesses, local communities, and regions. Given the multifaceted characteristics of the NBT sector we recruited a broad Delphi panel, and the survey design included both qualitative (first round) and quantitative (second and third round) analyses with feedback to survey participants. The process of discovering useful information by evaluating data is intrinsic to the Delphi method, in our case through the analyses of answers to the first and second survey rounds and two feedback loops. On this background, we give a descriptive presentation of the final study results from the third survey round.

The present study was undertaken before the COVID-19 pandemic. There is, however, no reason to believe that the main categories and associated trends identified here will be weakened by the pandemic; they are rather likely to be strengthened (Fredman & Haukeland, Citation2021; Hansen et al., Citation2022; Ioannides & Gyimóthy, Citation2020). We argue that many NBT businesses, which typically are small-scale entrepreneurs that operate in natural surroundings of rural regions, will have an advantage compared with larger firms operating at destinations with high numbers of residents and visitors (Lindberg et al., Citation2021). In the wake of the pandemic, nature is seen as a safe shelter, and the documented health-promoting trends underpin the importance of NBT; as a response to the COVID-19, a sustainable way out of it and perhaps also a defense against future crises. Previous studies have shown that spread of persistent life-threatening diseases may make international travel be perceived as a personal risk and that future travel may be strictly regulated to prevent the spread of virulent diseases among tourist destinations (Elmahdy et al., Citation2017).

The prominence of health-related issues in tourism is also reflected in our study. People are increasingly interested in gaining health and well-being from nature experiences. More emphasis is being placed on de-stressing and self-medicating, with more people seeking out natural therapies and treatments, including sunshine, fresh air and opportunities to exercise (Dwyer et al., Citation2008; Frost et al., Citation2014), forest bathing and walking (Lee et al., Citation2009). The positive mental health benefits from visiting and experiencing nature are well documented, as nature visits increase positive emotions and decrease stress, depression, fatigue, general anxiety, uncertainty and tension (Pasanen et al., Citation2014; Thompson Coon et al., Citation2011; Tsunetsugu et al., Citation2013; Tyrväinen et al., Citation2014, Citation2019). The health trend is also supported by a growing awareness of the benefits from physical activities in nature as the natural environments provides a safe and attractive setting for sports and other types of outdoor activities (James et al., Citation2015; Mytton et al., Citation2012). Previous studies also suggest that nature, eco- and adventure tourism enterprises have the potential to become certified providers of prescribed outdoor therapies in mainstream healthcare (Buckley, Citation2019).

Perhaps the most striking finding from this study is the prominence of sustainability. The cluster of three trends which is closely linked to natural and cultural sustainability, based on responsible travel, authentic experiences, and locally produced products signifies the crucial importance that key stakeholders in the NBT sector ascribe to sustainable experiences within the value chain, underlining that the quest for sustainability has become a key issue also for the sector’s commercial prospects. The orientation toward sustainability and responsible travel is highly driven by large global forces such as climate change and changes in land use and landscapes (Bell et al., Citation2007; Buckley et al., Citation2015; Dwyer et al., Citation2008; Dwyer et al., Citation2009; Scott & Gössling, Citation2015). Global warming will among many things hit winter tourism hard (Pröbstl-Haider et al., Citation2019), which is an important season in all countries/ regions included in this study. The responsible travel trend primarily concerns opportunities for eco-friendly alternatives and reduced carbon footprints. This can be seen in the light of growing international markets of NBT, including long haul travel, versus more local and eco-friendly destinations (Breiby et al., Citation2021). Recent concerns about over-tourism in highly visited locations is also likely to provide fodder to this trend (White et al., Citation2016).

Yet another important feature of the sustainability category is the opportunity to experience authentic nature and culture. NBT typically occur in landscapes where natural and cultural values interact, signifying local culture and regional products. At many destinations local natural heritage contributes to community and individual sense of identity, leading residents to connect more regularly with nature and value its protection and retention (Clemetsen et al., Citation2021; Frost et al., Citation2014). Due to the strong exploitation of many mountain areas (for example the European Alps) with substantial infrastructure (e.g. cable cars, ski resorts, and hotel resorts), such authentic experience can be understood as a countertrend, uplifted from the natural and cultural history of the destination. The same applies to the quest for local culture and locally produced products and food. Local food is a basis of many NBT products, and such offers are increasingly viewed against the dominant global uniformity of consumer goods. Hence, products from regional agriculture, processed environmentally friendly into characteristic regional dishes, have become an indispensable part of the NBT product at many rural destinations (Siegrist et al., Citation2019 Siegrist & Ketterer Bonnelame, Citation2017;).

Soft adventures are first and foremost advocated among the Nordic experts. This can be related to the Scandinavian/ Nordic ‘friluftsliv’ philosophy that revolves around simple, basic outdoor life, engaging in close relationship with nature with scant technical equipment – staring at the flames in a fire, listening to the waves, just being outdoors (Gurholt & Haukeland, Citation2019; Henderson & Vikander, Citation2007 ). Research has shown how modern mountain guiding in Norway heavily draws from such deeply rooted outdoor traditions (Løseth & Varley, Citation2021) and thus put professionalization in a special context (see below). Soft adventures also connect with the broadening of adventure tourism into the ‘slow’ domain characterized by inclusive, environmentally responsible, place-specific experiences (Semple & Varley, Citation2015). As such, the soft adventure trend clearly connects also with the health and sustainability categories described above.

Digitalization comprises the widespread introduction of online travel marketing systems, computerized reservation systems, web and social media-based reviews which all have a major impact on the tourism industry (Benckendorff, Citation2006; Scott & Gössling, Citation2015). For example, the power of word-of-mouth turns out to be an increasingly important factor combined with new technologies, such as electronic word-of-mouth (eVOM), influencing destination image and travel intentions (Jalilvand et al., Citation2012). Social media also becomes increasingly significant in the tourism domain and plays an important role in holiday planning as consumers more easily have access to reviews from fellow travelers and information by local residents (Buckley et al., Citation2015; Xiang & Gretzel, Citation2010). There are also many smartphone applications that target the nature-based tourism market, focusing on education, fitness, navigation, weather, photo, and video (Chekalina et al., Citation2021).

The NBT market includes affluent tourists with monetary resources and leisure time. Research indicates that tourists from regions such as Europe, North America, Australia, and Japan are becoming increasingly quality oriented (Mehmetoglu, Citation2007) in the quest for escapism, esthetics, and entertainment. With such demands follow opportunities to extract commercial values from the nature experience (Mehmetoglu & Engen, Citation2011). This underlines the significance of professionalization of the NBT industry, i.e. an efficient organization with skilled personnel that deliver high quality services. However, the underlying motivations to purchase guided tours and courses are diverse, including the search for unique experiences, safe travel, learning about nature and training technical skills (Dybsand & Fredman, Citation2020; Rokenes et al., Citation2015).

Our results may also serve as ‘weak signals’ in a broader tourism context (Uskali, Citation2005), as the sector in general continuously explore new ways to include nature experiences and activities (Margaryan, Citation2018). Weak signals are emerging ideas, intentions, discoveries, and/or innovations that have the potential to become prominent trends. They can be useful in a wider future tourism industry and planning framework to assist in foreseeing likely implications of human actions and their impacts on future commercial opportunities and sustainability prospects (Toivonen, Citation2017). An outlook from the NBT horizon can be particularly informative in our time when broader tourism industry prospects are undefined in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and environmental values are at risk. An interesting observation from this study is that several normative principles of ecotourism (Donohoe & Needham, Citation2006; Fennell, Citation2020), which encompass the very essence of sustainable NBT business models, have moved into the mainstream of contemporary NBT.

Concluding remarks

By means of a Delphi study, undertaken with 60 experts on NBT in Norway, Sweden, Finland, the European Alps, and western United States, five key trend categories with commercial potential are identified and discussed. These categories capture the eight underlying trends in the NBT sector which are assessed to have the highest commercial potentials according to the Delphi study panelists. The categories are related to essential values and principles (Health and Sustainability), outdoor recreational traditions (Soft adventure), and technological (Digitalization) and organizational (Professionalization) developments of modernity.

The ability to recognize and deal with major development directions is a key element of a successful tourism industry (Buckley et al., Citation2015; Dredge & Jenkins, Citation2011; Dwyer et al., Citation2008; Scott & Gössling, Citation2015) and the five main avenues for further NBT developments identified in this study could therefore represent valuable input to ‘the strategic context within which long-term tourism industry policies, planning and development are made’ (Dwyer et al., Citation2009, p. 64). Understanding the future is fundamentally important for making adequate business and industry strategies, management decisions, informing policy makers, and contributing to a sustainable development of tourism. It is, however, not possible to study the future empirically since no data is available for the time ahead of us, which put a limit to forecasting based on historical data (European Travel Commission, Citation2021). The Delphi method, therefore, represents an alternative approach to foresight the future more comprehensively (Fredman et al., Citation2023). It should be stressed that also a broad holistic approach to foresight, which the current study represents, may have limitations associated with geographical coverage since many of the world’s prominent NBT regions and countries are not included.

The spread of the COVID-19 virus is a reminder of the post-modern globalization era contemporary NBT is operating in. One interesting avenue for future research would therefore be to pay more attention to trends associated with health and sustainability. In our case, the selection of countries/ regions and the given composition of experts is a step in that direction, albeit still a limitation to consider. We suggest that future studies on trends in NBT should broaden the scope and include a greater variety of destinations to offer a more comprehensive and representative picture, in addition to provide a similar post-pandemic analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 There were some deviations from this: in Sweden, three experts were invited from the ‘government/ministry’ and ‘outdoor industry’ categories, and one expert was invited from the ‘youth organization’ category. In Norway, three experts were invited from the ‘NBT company or association’ and ‘outdoor industry’ categories.

References

- Bell, S., Simpson, S., Tyrväinen, L., Sievänen, T., & Pröbstl, U. (2008). European forest recreation and tourism: A handbook (pp. 264). Taylor and Francis Group.

- Bell, S., Tyrväinen, L., Sievänen, T., Pröbstl, U., & Simpson, M. (2007). Outdoor recreation and nature tourism: A European perspective. Living Reviews in Landscape Research, 1(2), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.12942/lrlr-2007-2.

- Benckendorff, P. (2006). Attractions megatrends. In D. Buhalis, & C. Costa (Eds.), Tourism business frontier (pp. 200–210). Heinemann.

- Bowen, J., & Whalen, E. (2017). Trends that are changing travel and tourism. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 9(6), 592–602. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-09-2017-0045

- Breiby, M., Øian, H., Aas, Ø, Fredman, P., & Haukeland, J. V. (2021). ‘Good’, ‘bad’ or ‘ugly’ tourism? Sustainability discourses in nature-based tourism. In Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism. From place-based resources to value-added experiences (pp. 130–142). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Buckley, R. (2019). Therapeutic mental health effects perceived by outdoor tourists: A large-scale, multi-decade, qualitative analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 77, 164–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.12.017

- Buckley, R., Gretzel, U., Scott, D., Weaver, D., & Becken, S. (2015). Tourism megatrends. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1005942

- Chekalina, T., Fossgard, K., & Fuchs, M. (2021). Facilitating smartly packaged nature-based tourism products through mobile CRM applications. In P. Fredman, & J. V. Haukeland (Eds.), Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism. From place-based resources to value-added experiences (pp. 222–236). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Clemetsen, M., Stokke, K. B., Barane, J., & Haraldseid, T. (2021). From tourist destination to local meeting place: Enhancing visitor experiences and social resilience in rural communities. In P. Fredman, & J. V. Haukeland (Eds.), Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism. From place-based resources to value-added experiences (pp. 50–63). Edward Elgar Publishing. 328 p.

- Derks, J., Giessen, L., & Winkel, G. (2020). COVID-19-induced visitor boom reveals the importance of forests as critical infrastructure. Forest Policy and Economics, 118, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102253.

- Donohoe, H. M. (2011). Defining culturally sensitive ecotourism: A Delphi consensus. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(1), 27–45. DOI: 10.1080/13683500903440689

- Donohoe, H. M., & Needham, R. D. (2006). Ecotourism: The evolving contemporary definition. Journal of Ecotourism, 5(3), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.2167/joe152.0

- Dredge, D., & Jenkins, J. (2011). Stories of practice: Tourism planning and policy (402 p.). Routledge, Ashgate.

- Dwyer, L., Edwards, D., Mistilis, N., Roman, C., & Scott, N. (2009). Destination and enterprise management for a tourism future. Tourism Management, 30(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.04.002

- Dwyer, L., Edwards, D., Mistilis, N., Scott, N., Roman, C., & Cooper, C. (2008). Trends underpinning tourism to 2020: An analysis of key drivers for change. CRC for Sustainable Tourism.

- Dybsand, H. N. H., & Fredman, P. (2020). The wildlife watching experiences cape: The case of musk ox safaris at Dovrefjell-Sunndalsfjella National Park, Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(2), 148–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1850347

- Elmahdy, Y. M., Haukeland, J. V., & Fredman, P. (2017). Tourism megatrends, a literature review focused on nature-based tourism. Norwegian University of Life Sciences, MINA technical report (fagrapport) 42. 74 pp.

- European Travel Commission. (2021). Handbook on tourism forecasting methodologies. ETC Market Intelligence Report, Brussels, Belgium. 97 p.

- Fennell, D. (2020). Ecotourism. Routledge.

- Ferguson, M. D., Lynch, M. L., Evensen, D., Ferguson, L. A., Barcelona, B., Giles, G., & Leberman, M. (2022). The nature of the pandemic: Exploring the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic upon recreation visitor behaviors and experiences in parks and protected areas. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2022.100498. Available online 28 February

- Fredman, P., & Haukeland, J. V. (2021). Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism. From place-based resources to value-added experiences (298 p.). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Fredman, P., & Margaryan, L. (2014). The supply of nature-based tourism in Sweden: A National Inventory of Service Providers. ETOUR Report 2014:1. Östersund: Mid Sweden University.

- Fredman, P., & Margaryan, L. (2020). 20 years of Nordic nature-based tourism research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 14–25. DOI: 10.1080/15022250.2020.1823247

- Fredman, P., Sievänen, T., Jensen, F. S., Gundersen, V., Wall-Reinius, S., Lexhagen, M., Lundberg, C., Sandell, K., Vistad, O. I., & Wolf-Watz, D. (2023). Approaches to foresight recreation and tourism in nature. In A. Mandic, & S. K. Walia (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of nature-based tourism development (584 p.) Routledge.

- Fredman, P., & Tyrväinen, L. (2010). Frontiers in nature-based tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 10(3), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2010.502365

- Frost, W., Laing, J., & Beeton, S. (2014). The future of nature-based tourism in the Asia-pacific region. Journal of Travel Research, 53(6), 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513517421

- Fuchs, M., Fossgard, K., Stensland, S., & Chekalina, T. (2021). Creativity and innovation in nature-based tourism: A critical reflection and empirical assessment. In P. Fredman, & J. V. Haukeland (Eds.), Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism. From place-based resources to value-added experiences (pp. 175–193). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Gartner, W. C., & Lime, D. W. (2000). Trends in outdoor recreation, leisure and tourism (199 p.). CABI Publishing.

- Gurholt, K. P., & Haukeland, P. I. (2019). Scandinavian friluftsliv (outdoor life) and the Nordic model: Passions and paradoxes. In M. B. Tin, F. Telseth, J. O. Tangen, & R. Giulianotti (Eds.), The Nordic model and physical culture (pp. 165–181). Routledge.

- Hammitt, W. E., Cole, D. N., & Monz, C. A. (2015). Wildland recreation. Ecology and management (2nd ed.). Wiley Blackwell.

- Hansen, A. S., Beery, T., Fredman, P., & Wolf-Watz, D. (2022, Feb 18). Outdoor recreation in Sweden during and after the COVID-19 pandemic – Management and policy implications. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2022.2029736

- Haukeland, J. V., Fredman, P., Siegrist, D., Tyrväinen, L., Lindberg, K., & Elmahdy, Y. M. (2021). Trends in nature-based tourism. In P. Fredman, & J. V. Haukeland (Eds.), Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism. From place-based resources to value-added experiences (pp. 16–31). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Henderson, B., & Vikander, N. (2007). Nature first: Outdoor life the friluftsliv way. Natural Heritage Books. 336 p

- Ioannides, D., & Gyimóthy, S. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763445

- Jalilvand, M. R., Samiei, N., Dini, B., & Manzari, P. Y. (2012). Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination and travel intention: An integrated approach. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 1(1-2), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.001

- James, P., Banay, R. F., Hart, J. E., & Laden, F. (2015). A review of the health benefits of greenness. Current Epidemiology Reports, 2(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-015-0043-7

- Konu, H. (2015). Developing a forest-based wellbeing tourism product together with customers–An ethnographic approach. Tourism Management, (49), 1–16 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.02.006

- Kronenberg, K., & Fuchs, M. (2021). The socio-economic impact of regional tourism: An occupation-based modelling perspective from Sweden. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(12), 2785–2805. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1924757.

- Landeta, J. (2006). Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 73(5), 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2005.09.002

- Lee, J., Park, B. J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Kagawa, T., & Miyazaki, Y. (2009). Restorative effects of viewing real forest landscapes, based on a comparison with urban landscapes. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 24(3), 227–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827580902903341

- Lindberg, K., Forbord, M., & Sivertsvik, R. M. (2021). Nature-based tourism and community resilience. In P. Fredman, & J. V. Haukeland (Eds.), Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism. From place-based resources to value-added experiences (pp. 64–79). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Linstone, H. A., & Turoff, M. (2002). The Delphi method - Techniques and applications. 616 p. https://web.njit.edu/~turoff/pubs/delphibook/delphibook.pdf

- Løseth, K., & Varley, P. (2021). Commercial mountaineering. Norwegian friluftsliv and the gradual march of commodification. In P. Fredman, & J. V. Haukeland (Eds.), Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism. From place-based resources to value-added experiences (pp. 194–206). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lundberg, C., & Fredman, P. (2012). Critical success factors and constraints among nature-based tourism entrepreneurs. Current Issues in Tourism, 15(7), 649–671. DOI:10.1080/13683500.2011.630458

- Margaryan, l. (2018). Nature as a commercial setting: The case of nature-based tourism providers in Sweden. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(16), 1983–1911. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1232378

- Margaryan, L., & Fredman, P. (2017). Bridging outdoor recreation and nature-based tourism in a commercial context: Insights from the Swedish service providers. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 17, 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2017.01.003

- Mehmetoglu, M. (2007). Nature-based Tourists: The Relationship Between their Trip Expenditures and Activities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(2), 200–215. http://doi.org/10.2167/jost642.0

- Mehmetoglu, M., & Engen, M. (2011). Pine and Gilmore's concept of experience economy and its dimensions: An empirical examination in tourism. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 12(4), 237–255. DOI: 10.1080/1528008X.2011.541847

- Miller, G. (2001). The development of indicators for sustainable tourism: Results of a Delphi survey of tourism researchers. Tourism Management, 22(4), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00067-4

- Mytton, O. T., Townsend, N., Rutter, H., & Foster, C. (2012). Greenspace and physical activity: An observational study using health survey for England data. Health & Place, 18(5), 1034–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.06.003

- Pasanen, T. P., Tyrväinen, L., & Korpela, K. M. (2014). The relationship between perceived health and physical activity indoors, outdoors in built environments, and outdoors in nature. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-being, 6(3), 324–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12031

- Pröbstl-Haider, U., Richins, H., & Türk, S. (2019). Winter tourism – Trends and challenges. Cabi International. 548 p.

- Rinne, P., & Saastamoinen, O. (2005). Local economic role of nature-based tourism in Kuhmo Municipality, Eastern Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 5(2), 89–101. DOI: 10.1080/15022250510014363

- Rokenes, A., Schumann, S., & Rose, J. (2015). The art of guiding in nature-based adventure tourism – How guides can create client value and positive experiences on Mountain Bike and Backcountry Ski tours. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(Issue sup 1), 62–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1061733

- Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2015). What could the next 40 years hold for global tourism? Tourism Recreation Research, 40(3), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1075739

- Semple, T., & Varley, P. (2015). Nordic slow adventure: Explorations in time and nature. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(1-2), 73–90. DOI: 10.1080/15022250.2015.1028142

- Siegrist, D., Gessner, S., & Ketterer Bonnelame, L. (2015). Naturnaher Tourismus. Qualitätsstandards für sanftes Reisen in den Alpen. Bristol-Schriftenreihe 44. Haupt Verlag. ISBN: 978-3-258-07922-6.

- Siegrist, D., Gessner, S., & Ketterer Bonnelame, L. (2019). Naturnaher Tourismus. Qualitätsstandards für sanftes Reisen in den Alpen. Bristol-Schriftenreihe 44. Haupt Verlag. ISBN: 978-3-258-07922-6.

- Siegrist, D., & Ketterer Bonnelame, L. (2017). Nature-based tourism and nature protection: Quality standards for travelling in protected areas in the Alps. eco.mont – Volume 9, special issue, January 2017. 29–34.

- Spenceley, A., & Rylance, A. (2019). The contribution of tourism to achieving the United Nations sustainable development goals. In S. F. McCool, & K. Bosak (Eds.), A research agenda for sustainable tourism (272 p.). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Stensland, S., Forbord, M., Fossgard, K., & Løseth, K. (2021). Characteristics of nature-based tourism firms. In P. Fredman, & J. V. Haukeland (Eds.), Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism. From place-based resources to value-added experiences (pp. 144–161). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Stensland, S., Fossgard, K., Bergsnov Hansen, B., Fredman, P., Morken, I.-B., Thyrrestrup, G., & Haukeland, J. V. (2018). Naturbaserte reiselivsbedrifter i Norge. Statusoversikt, resultater og metode fra en nasjonal spørreundersøkelse. MINA fagrapport 52. Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

- Thompson Coon, J., Boddy, K., Stein, K., Whear, R., Barton, J., & Depledge, M. H. (2011). Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(5), 1761–1772. https://doi.org/10.1021/es102947t

- Toivonen, A. (2017). Sustainable planning for space tourism. Matkailututkimus, 13(1-2), 1–2.

- Tsunetsugu, Y., Lee, Y., & Tyrväinen, L. (2013). Physiological and psychological effects of viewing urban forest landscapes assessed by multiple measurements. Landscape Urban Planning, 113, 90–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.01.014

- Tyrväinen, L., Bauer, N., & O’Brien, L. (2019). Impacts of forests on human health and well-being. In: Marusakova. L. & Sallmanshofer, M. (eds.), Human health and sustainable forest management. FOREST EUROPE Study, FORESTS EUROPE, Liaison Unit Bratislava, ISBN 978-80-8093-265–7. pp. 30–57. https://foresteurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Forest_book_final_WEBpdf.pdf

- Tyrväinen, L., Ojala, A., Korpela, K., Tsunetsugu, Y., Kawaga, T., & Lanki, T. (2014). The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.12.005

- Tyrväinen, L., Sievänen, T., Konu, H., Anja, T., Aapala, K., & Ojala, O. (2018). How to develop nature-based recreation and tourism in Finland? Policy Brief, Valtionneuvoston selvitys- ja tutkimustoiminta 2/2018. [in Finnish].

- Uskali, T. (2005). Paying attention to weak signals – The key concept for innovation journalism. Innovation Journalism, 2(11), 3–17.

- Venter, Z., Barton, D., Gundersen, V., Figari, H., & Nowell, M. (2020). Urban nature in a time of crisis: recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway, SocArXiv.

- von Bergner, N. M., & Lohmann, M. (2014). Future challenges for global tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 53(4), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513506292

- Weston, R., & Nicholas, D. (2007). The future of transport and tourism: A Delphi approach. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 4(2), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530701554157

- White, E., Bowker, J. M., Askew, A. E., Langner, L. L., Arnold, J. R., & English, D. B. (2016). Federal outdoor recreation trends: Effects on economic opportunities. USDA – United States Department of Agriculture. https://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/pnw_gtr945.pdf

- Xiang, Z., & Gretzel, U. (2010). Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Management, 31(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.016

Appendix

The 36 trends used in the second and third rounds of the Delphi surveys (trends marked with an * were included in the US survey)

Commercial guided services or courses in nature*

Sustainability and responsible travel *

Simple and easily accessible activities (soft adventure)*

Experience local culture and locally produced products, food, etc.

Increased international demand*

Physical activities in nature for health and fitness*

Digital marketing, trip planning, and booking*

Package tours that combine products and services

Experience iconic nature-based environments/places/ trails

Demand for remote and unique places

Experience pure nature environments*

Sports/ activity-oriented nature-based experiences*

Modern architecture/ facilities in nature

Nature experiences near cities

Product customization for different markets*

Electronically shared nature experiences (for example social media)*

Demand for improved infrastructure and public transport

Increased demand in the winter season*

Increased cooperation across landowners

Authentic nature and culture experiences*

Nature experiences combined with high-quality facilities and services

Organized events, competitions, adventures in nature

Health and wellbeing from nature experiences*

Digitally enhanced nature experiences (augmented reality)

Urban demand for new outdoor experience products and services*

Shorter vacations and stays in nature*

Personalized and exclusive experiences in nature

Learning and new experiences in nature

Increased government funding for nature-based tourism, recreation and public lands*

Activities and experiences in Arctic nature

Visit nature without online services (digital detox)

Experience wild food (berries, mushrooms, game, herbs, etc.)

Decreased public funding for public land management*

Management challenges with increased use (crowding, conflict, ecologic impact) *

Diversity of activities leads to conflict and requests for separate opportunities*

Lack of youth engagement in outdoor recreation*