ABSTRACT

This paper examines the effects of crises of climate change and geopolitical civil conflict in Cameroon, on the development of the ecotourism sector. Additionally, the hurdles to the regeneration of the sector post- the COVID-19 pandemic are considered. A qualitative research design was used. In-depth interviews were conducted with key informants involved in the ecotourism sector, including government officials, local community representatives, conservationists, non-governmental organizations and management of national parks. The data collected were thematically analysed, with key themes pointing towards the dire impacts of COVID-19, geopolitical and climate crises on the sector, with one of the primary consequences being inhibited movement of people, extreme weather events and changes to flora and fauna, ultimately leading to shrinkage of the sector. The central nature of conservation, linked to ecotourism, was also highlighted. The importance of collaborative management, development of dedicated policy and strategic plans for the successful regeneration of ecotourism also emerged. The paper provides contemporary insights and recommendations into the sustainable regeneration of ecotourism in the face of extreme geopolitical and socio-economic crises.

1. Introduction

Home to a host of endemic species, endangered fauna and diverse ecosystem biomes, it is not surprising that the development of ecotourism in Cameroon has been designated as a key sector to initiate economic growth in the country (Kimbu, Citation2011; Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife [MINFOF], Citation2014). There have, however, been many constraints to the sustainable development of the sector, the first of which being the fragmented policy framework and governmental ministries dedicated to tourism development in the country (Harilal et al., Citation2019), as well as the more recent global COVID-19 pandemic that affected tourism destinations globally (Gössling et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the varied impacts of the global climate crisis and its effects on conservation are also important considerations, given the central role of conservation in ecotourism. The importance of conservation of the natural resource base, including ecosystems, flora, fauna, and traditional socio-cultural heritage is of utmost importance for ecotourism to occur (Novelli et al., Citation2006; Wondirad, Citation2019). Essentially, conservation of these resources equates to conservation of the ecotourism product (Wardle et al., Citation2021). Thus, careful conservation of the natural resource base must form a central aspect of ecotourism sectors and should be embedded in regeneration strategies.

Adding to the complexity, Cameroon is characterised by a unique geopolitical situation, stemming from the existence of two dominant linguistic groups – the Francophone and Anglophone populations (Harilal & Tichaawa, Citation2020). Geographically, the country is demarcated into different provinces, each dominated by a linguistic group. This demarcation is ultimately a legacy of Cameroon’s colonial past, with seven provinces classified as Francophone and the remaining two as Anglophone (Kimbu, Citation2010). The different political and cultural sentiments of these two population groups are further intensified by the ruling Francophone political party in the country (Mbatu, Citation2009). The long-standing strife between these groups has put a strain on the country as a whole since late 2017 (Tichaawa & Kimbu, Citation2019) and has consequently hampered efforts to develop the ecotourism sector in a way that services community upliftment, as well as the conservation of key species and ecosystems.

This empirically based paper sought to examine the effects of the ongoing civil conflict in Cameroon on the development of the ecotourism sector, as well as the hurdles to the regeneration of the sector post- the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the impacts on ecosystem biological diversity from the ongoing climate crisis were also examined, given Cameroon’s varied ecological biomes and sensitive ecosystems. The biological diversity that the country boasts, varying from coastal to tropical rainforest, as well as endangered populations of primate and other species, has earned it the moniker of ‘all of Africa in one’ and ‘Africa in miniature’ (Burgin & Zama, Citation2014; Atchombou et al., Citation2023). It is thus imperative that research in these contexts is undertaken, to better understand and address the theoretical gap in the literature on African (specifically central African) perspectives on sustainable ecotourism development. This is also essential to gain insights into the impacts of climate change on countries in the global south and specifically within the African context given the current availability of information from this perspective (Scott et al., Citation2019). Whilst there is a substantial amount of research on tourism and ecotourism in Africa, there is an uneven geographic spread of this research with most of it addressing the Southern and Eastern African perspectives. Thus, the significance of this paper lies in its contribution to the discourse on ecotourism in central Africa concerning Cameroon, specifically from a unique geopolitical, crisis and environmental perspective.

2 Literature

2.1 COVID-19 crisis, impacts and the Cameroonian context

The COVID-19 global pandemic triggered an unprecedented crisis within the global tourism sector (Scott, Citation2021). In an attempt to halt the spread of the virus, a global lockdown was initially instituted in March 2020. As a result, the borders of all tourism destinations were closed, preventing movement in or out of countries (Kuščer et al., Citation2022). As the pandemic progressed, and vaccines were developed as a primary control measure, global politics came into play and resulted in an uneven distribution of the vaccine, with many countries in the global south being sidelined. Consequently, the reopening of tourist destinations across the world was staggered, with those who had their citizens vaccinated able to reopen first, creating an uneven situation in the global tourism industry (Dube, Citation2022). Within the global south context, where many of the tourism sectors are still developing, the extended closure of borders and lack of access to vaccines resulted in a prolonged period without tourists (and consequently, tourist-generated income). The severe socio-economic impacts of this were borne by local stakeholders, whose livelihoods depended on various activities within the tourism sector (Anyanwu & Salami, Citation2021).

Within the Cameroonian context, apart from the aforementioned global lockdown, national lockdown restrictions were eased within a few weeks of the global lockdown being dissolved (Lukong, Citation2020). Thus, movement within the country could occur. Public transportation resumed, as did the operations of restaurants and bars (on conditions of initiatives that curbed the spread of the disease). Hence, operation of the tourism sector was largely restored for domestic tourists. However, given the complexity of the geopolitical crisis that the country has faced since 2016, the easement of travel restrictions from COVID-19 lockdowns did not translate into a booming tourism sector.

2.2 Geopolitical crisis and impacts

The geopolitical crisis in Cameroon stems from dissent from the Anglophone population in the country, who advocate for separatism. However, the ruling Francophone political party and the majority population in the country reject this, resulting in the conflict (Ekah, Citation2019). As the conflict progressed, issues of safety arose, especially concerning the ability to travel between regions in the English-speaking provinces. This had a direct negative impact on the tourism sector in these regions, as potential tourists were unwilling to risk travelling through and within such volatile zones. The violence associated with the conflict was severe, affecting civilians. At the height of the conflict, entire regions were shut down by separatist fighters (Ngong, Citation2022). This translated to people losing their livelihoods – especially those who relied on the influx of tourists to support their businesses and service offerings. Given that the geopolitical crisis preceded the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and that the two crises occurred concurrently for the previous three years, the extent of the negative effects on the tourism sector was compounded (Song, Citation2020). Specifically, the arrival of tourists at ecotourism sites was not possible over a prolonged period. International tourist arrivals were inhibited by the country’s border closure due to COVID-19 lockdowns and domestic tourist travel within the country was inhibited due to the tension of the geopolitical crisis (Loveline, Citation2022). Currently, given that the crisis is still ongoing, there are still areas (mostly within the Francophone regions) that are declared unsafe to travel, and certain areas that have been closed off by the separatist faction. Thus, although the country is host to several ecotourism attractions, most of these have been or continue to be inaccessible due to previous and current crises (Bang & Balgah, Citation2022).

A direct consequence of inhibited travel and the use of ecotourism facilities and attractions is the reduced revenue generated by tourists. Oftentimes, revenue is generated through road toll fees, entrance fees and other levies from ecotourism and conservation sites; with this revenue being an extremely important resource for the upkeep and maintenance of attractions, parks, gardens, roads and other ecotourism facilities. Additionally, apart from this direct revenue generation, there were also alternate income-generating strategies stemming from the tourism sector, that locals engaged in, such as portering, tourist guiding, running food and beverage establishments and local craft and souvenir enterprises (Harilal & Tichaawa, Citation2018). The closure of the sector due to the crises has resulted in severe socio-economic losses for individuals who relied on ecotourism for their livelihoods (Scott, Citation2021). It is important to consider that in cases where communities have been encouraged to participate in ecotourism sectors, this is often a trade-off when giving up traditional livelihood strategies in favor of the former (Stone, Citation2015; Jaya et al., Citation2022). Therefore, focusing on the regeneration of ecotourism is a multifaceted issue, that is essential for the socio-economic state of locals, as well as to support the conservation of the physical environment.

2.3 Climate crisis and its impacts

Conservation of the biophysical environment is key to a sustainable and successful ecotourism sector (Wardle et al., Citation2021). Given that ecotourism products are based on the natural environment, it is imperative that these resources, flora and fauna are adequately conserved and preserved. Apart from ecotourism needing to be managed carefully to avoid overuse of the environment and resources, the threat of climate change and resultant impacts needs to also be carefully managed, to preserve the integrity of the environment, the critical ecosystem services and the ecotourism sector itself (Scott et al., Citation2019; Ramaano, Citation2023).

Globally the climate crisis has gained recognition in recent years, driven by the increase in cases of climatic variability and the effects of global warming. Acknowledgement of this as an anthropogenic crisis has also gained traction (Chakraborty, Citation2019), given the immense contribution of greenhouse gas emissions from industrialization and other human activities (Scott, Citation2021). Unfortunately, the tourism sector – specifically long-haul air travel – has been flagged as a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions (Gühnemann et al., Citation2021). However, the sector has also been flagged as one that can play a supporting role in various conservation and preservation initiatives and sustainable development goals, to reduce the impacts of climate change and the resultant crisis.

When contemplating the narrative of the climate crisis, it is important to consider the key contributors. These mostly include regions outside of Africa, given that the continent is reported to be a low contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, on account of low levels of mechanization (United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], Citation2014). Therefore, within the global south context and specifically the African context, vulnerability to the impacts of climate change is high (World Meteorological Organisation, Citation2022). Consequently, the contribution of countries in the region to the climate crisis is lower, especially in terms of emissions. However, given that the climate crisis is a global one (Chausson et al., Citation2020), even countries whose contribution is low needs to be carefully monitored. In the African context, where many countries are trying to develop their tourism sectors, with many relying on ecotourism due to their rich natural environments and resource base, the way in which these sectors are developed becomes critical (Mkiramweni et al., Citation2017). Measures to mitigate the effects of the climate crisis must be embedded into the development of the tourism sector. Additionally, the prevention of greenwashing and sustainable management of the sector to protect it from becoming extractive is key. This should be intentional in reconceptualizing the role of ecotourism in conservation (Chakraborty, Citation2019).

Some of the impacts associated with the climate change crisis are the increased frequency of extreme weather events such as floods, heavy rainfall, droughts and temperature extremes or average temperature variations (Jamaliah & Powell, Citation2017; Gühnemann et al., Citation2021; Scott, Citation2021). The latter has led to situations where the weather seasons become altered, leading to changes in biomes, flora and fauna (Wonirad, Citation2019). In many cases, these changes have negatively affected tourist seasonality and behaviours (Gühnemann et al., Citation2021), especially in cases where weather seasons also form the basis of ecotourist attractions (Mkiramweni et al., Citation2017). For example, birdwatching, whale and shark watching, and primate trekking are a few examples of ecotourism activities that are dependent on specific climatic and weather conditions. As this changes, so do the migratory patterns of these fauna. In many cases, migratory species tend to change course to other areas with suitable climatic conditions (Manes et al., Citation2021). This has been witnessed in many regions of the world recently. For example, on the west coast of South Africa, due to various climatic changes, there has been a marked difference in the migratory patterns of whale and shark species – both of which form the basis of key tourism offerings (O’Reagan, Citation2022). Another example relates to (already) endangered African primate species, who are highly vulnerable to climatic changes, loss of habitat and food sources, as well as being hunted. Carvalho et al. (Citation2021) notes that these cumulative impacts will have a lasting impact on the primate species, but also cascading impacts on the ecosystem and biodiversity, as well as on the ecotourism sector itself.

2.4 Conservation and ecotourism

Ultimately, conservation of the natural resource base should occur whether or not there is an active ecotourism sector and can take on different forms. For example, a common type of conservation practiced by many countries is that of fortress conservation, where physical boundaries are erected to protect certain areas and the physical environment therein (Stone, Citation2015; Fletcher, Citation2017). A consequence of this type of conservation is the exclusion of people, often local community members, who rely on the area and natural resource base for livelihood and traditional activities. This is contrary to the central premise of ecotourism, where local involvement and participation are key to the success of the sector (Stone, Citation2015). This is an important point to note, as it highlights the intersection of conservation with ecotourism, and the role of local stakeholders in the process (Pellis et al., Citation2015). It is important that a balance is struck between these components, to ensure equitable benefit sharing within the system. Although ecotourism is not needed for the establishment of protected areas, nor for the active practice of conservation measures, it definitely has the capability of acting as a support tool for conservation to occur (Wardle et al., Citation2021). For example, the revenue generated from the ecotourism sector can be channeled into conservation of the environment and resources, education of locals and facilitating their involvement, as well as providing alternate income and livelihood activities when their access and reliance on the natural resource base is reduced, due to conservation measures and ecotourism (Jaya et al., Citation2022). The payoff between ecotourism using the physical environment as a tourism product feeds directly into the incentive to protect and conserve it (Pellis et al., Citation2015). Thus, it is important that conservation measures account for this, especially in terms of the involvement of local people (Pyke et al., Citation2018; Wonirad, Citation2019).

Traditional conservation methods that have been shared through generational knowledge, often referred to as indigenous knowledge, are a key aspect of the conservation-ecotourism-local stakeholder system (Ondicho, Citation2018). This type of knowledge is highly nuanced and has been adapted for use in various areas, based on the characteristics of that particular physical environment. Although this is generally not knowledge that is accessible through conventional books, it is still extremely important to consider within the realm of sustainable natural resource management and ecotourism, due to the involvement of locals who are expected to support and participate in the sector (Venkatesh & Gouda, Citation2016). Indigenous knowledge also has strong ties to the longstanding culture and traditions of a place, which locals have maintained for substantial amounts of time. To disregard this knowledge as an integral aspect of conservation practices in these regions is to disregard the locals themselves (Bixler, Citation2013). Consequently, local support for the sector can easily become compromised.

2.5 Ecotourism-crises-conservation nexus

Within the Cameroonian context, where the ecotourism sector is still in a developmental phase, it is imperative that the implications of the climate crisis be considered in the strategic development and management of the sector. It has been noted that the ecotourism sector in Cameroon suffers from a lack of dedicated policy to guide the strategic development of the sector (Harilal et al., Citation2022). As the sector looks towards regeneration post- the COVID-19 pandemic, whilst in the midst of geopolitical conflict and attempting to manage the effects of the climate crisis, it is essential that these issues are given due consideration. It has been noted that many more crises will occur within the tourism sector (Bhatt et al., Citation2022), thus necessitating the need for (eco)tourism to be (re)developed in a manner that allows for flexibility, reducing the effects of shocks to the sector, and providing a layer of insulation to ensure that the physical environment and various tourism stakeholders are resilient to possible change and disruptions. Although the effects of the crises appear to be very damaging to the ecotourism sector, the well known benefits of ecotourism in locals livelihoods, conservation and local economic development (Jaya et al., Citation2022; Harilal et al., Citation2022; Forje et al., Citation2021) can be leveraged within areas in the country. This can be done to trigger a restart of the sector, which is in dire need of a reconceptualization due to the ongoing conflict and crises. The ecotourism sector can be located at the center of the crisis-conservation nexus, serving the conservation agenda but being a central victim of the ongoing conflict in certain regions. Ultimately, apart from the established strategic importance of the ecotourism sector in the country (see Harilal & Tichaawa, Citation2020; Kimbu, Citation2011), the sector’s agenda can also serve dual purposes, supporting that of regeneration through mitigating some of the impacts associated with the aforementioned crises.

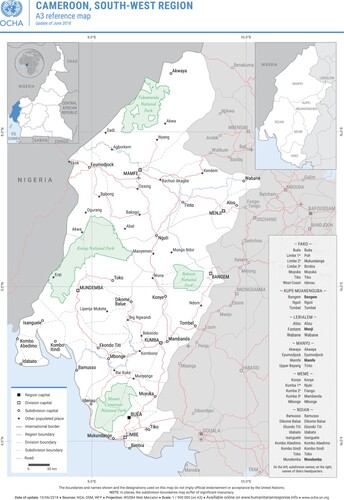

2.6 Study site

This study was conducted within the South-West province of Cameroon, specifically within the regions of Limbe and Bimbia, as shown in below, with the study area regions circled in red on the map. These regions are ecotourism hotspots in the country (Ngade et al., Citation2017), situated on the coast of the country, boasting black sand beaches and tropical rainforest areas (Nyindem & Ndimofor, Citation2020). Some of the main economic activities in the areas revolve around fishing, the only oil industrial complex in the country, and tourism (Tichaawa et al., Citation2022; Nyiawung et al., Citation2023;). Additionally, historical socio-cultural attractions such as the Bimbia Slave Trade Village (Nyindem & Ndimofor, Citation2020), as well as protected areas home to various endemic wildlife species characterize the regions. Moreover, these regions are also close to Mount Cameroon, an active volcano situated within the bounds of Mount Cameroon National Park (Ngade et al., Citation2017; Bessa et al., Citation2021). There are many different ecotourism products and experiences on offer in these regions, such as bird and wildlife watching, hiking and mountain trekking, coastal and marine experiences, as well as nature-based experiences such as visiting the Limbe Botanical Gardens which is home to various native, historic and culturally significant plant and animal species. This emphasizes the reason why Cameroon is referred to as ‘Africa in miniature’ (Atchombou et al., Citation2023). The regions were host to tourists prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical conflict lockdowns. Although recent statistics on this are scarce, it was reported that there were 573 000 international tourist arrivals in the country in 2010 (World Economic Forum, Citation2013), with the annual growth of the industry estimated at 4.8% for the period 2018 to 2028 (WTTC, Citation2018). However, the continued growth of arrivals have been impacted by the geopolitical and COVID-19 crises (Sama & Molua, Citation2019). Thus, as these regions are gearing up to restart the ecotourism sector, they constituted ideal study areas for this research.

Figure 1. Study area: Limbe and Bimbia regions. Source: OCHA (Citation2018)

3 Materials and methods

A qualitative research design was adopted for use in this study. Given the relatively scant research on ecotourism development in the Cameroonian context, and the need to gain comprehensive insights into the issues surrounding the regeneration of ecotourism, in-depth interviews were deemed the most appropriate (Santos et al., Citation2020). Key informants, including representatives from government, non-governmental organizations, conservationists, and community leadership (quarter head and chiefs) were purposively selected and interviewed on a face-to-face basis. below describes each informant group, as well as the rationale for them being purposively selected.

Table 1. Description of informant groups.

The in-depth interviews were conducted from March until June 2023, with each interview lasting approximately 60 min. At the end of the data collection period, 32 interviews had been conducted with key informants. A semi-structured interview guide was developed for use in this study, with the broad questions focusing on the state of ecotourism in the areas, the impacts of the geopolitical conflict, the effects of varying weather and climate change, as well as the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Questions around the regeneration of the sector were also posed to respondents, to gauge their opinions on how the ecotourism sector in the country can be restarted in light of the numerous challenges it has faced. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, with thematic content analysis being conducted by the researchers, using the transcripts to identify emerging themes from the data. Thematic content analysis is a commonly used in tourism research, especially in the analysis of transcripts (Walters, Citation2016), given its utility in the analysis of written texts (Nunkoo, Citation2018). Atlas.ti, a qualitative data analysis software, was used in the data analysis process, to aid in line-by-line coding. This was done in an effort to delve deeply into the data. Thereafter, the codes were grouped into the key themes that emanated from the data and subsequently presented and discussed in the following section. Additionally, existing literature was used to triangulate the findings and discussion.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Ecotourism and conservation in Cameroon: stakeholder views

In Cameroon, the ecotourism sector is as recognized as a strategic sector that can support socio-economic development, as well as support the achievement of environmental conservation for sustainable development goals. This has been noted by respondents who noted that although ecotourism is not necessary for environmental conservation, it is certainly beneficial and has become an important tool in the strategy to roll out conservation measures.

I strongly believe ecotourism is a key factor for conservation of biodiversity to happen … ecotourism is necessary for conservation to occur. (Park management 3)

Conservation attracts ecotourism and ecotourism motivates conservation. (Conservationist 1)

Ecotourism is necessary for conservation to occur as it generates revenue used in conservation, like entrance fees to visit protected areas. (Quarter head 2)

In Mt. Cameroon area, repentant poachers have been transformed to guides and porters as alternative sources of income and to reduce the pressure on wildlife. (Park management 2)

Species protected and most conserved include African elephant, gorilla, drill and mandrill monkeys, chimpanzee, giant pangolin amongst others. Plants include maobi, bubinga and wengue. (Park management 3)

Anybody violating the rules and regulations has a heavy fine to pay. (Conservationist 1)

Ecotourism has increased conservation. (Quarter head 1)

4.2 Ecotourism under threat

A central tenant of this paper was to examine the multiple threats that the ecotourism sector in Cameroon faces. The threats, emanating directly and indirectly from the various crises present a nuanced situation within which the regeneration of the ecotourism sector in the country must occur. Therefore, key towards initiating regeneration is understanding the cumulative impacts of the threats. The following section presents an overview of the impacts of the various crises, from the perspectives of the stakeholders interviewed.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on ecotourism in Cameroon

COVID-19 drastically reduced the number of tourists and corresponding revenue from ecotourism. (Park management 2)

Increased severe conservation measures and the establishment of a conservation-ecotourism business development plan are key. (Park management 1)

4.2.1. The geopolitical crisis

The geopolitical crisis that plagues the country is an extremely sensitive one, stemming from dissatisfaction among the Anglophone population of the country to being under Francophone rule. The conflict, which flared up in late 2016, has resulted in numerous instances of violence across the country, especially in the Anglophone provinces in the country. Restriction on movement within the provinces was instituted as the conflict reached critical levels, with these restrictions adjusted based on the intensity of the conflict. Consequently, fear of travelling internally developed among the population, as well as among international tourists. This fear, according to respondents, is not unfounded as separatist fighters in the conflict have been known to capture civilians and tourists for ransom.

The civil crisis brought total insecurity in the affected regions, making it impossible for Forestry staff in uniform to perform their duties … ecotourists were advised not to visit these areas. The insecurity persisted until many countries from where ecotourists were coming from advised their citizens not to visit these areas of Cameroon.(NGO 1)

The conflict is still ongoing within the country, having occurred at the same time as the COVID-19 pandemic. The compounded effect of the aforementioned COVID-19 lockdown and restriction on movement, coupled with conflict-triggered and related lockdowns, has had devastating effects on the ecotourism sector. Although the former mostly affected international tourist arrivals, and the latter domestic tourist arrivals, compromised safety compromised travel to and within the country. Furthermore, this was exacerbated in ecotourism hotspots, such as protected, forested areas, as these become sites of refuge for conflict fighters. Thus, all ecotourism activities such as mountain trekking and hiking, bird and wildlife watching, as well as any other activity that occurred within these areas were declared as unsafe.

There is fear to go to certain sites. Out of town people are scared to visit those areas, people complain of a lack of security measures. We always hear it is secure, but we are afraid of the unknown, especially the way our country is because of the geopolitical crisis. (NGO 4)

The complexity of the crisis has given rise to several different views, with some respondents noting that the crisis is reasonable and stems from a sound rationale, whilst others completely disagree. Some respondents initially agreed with and understood why the crisis was triggered, but currently disagree with the state of affairs as it is felt that the core issues have been hijacked by alternate agendas of separatist fighters.

In noting these sentiments, there is no foreseeable end to the crisis yet, leaving the ecotourism sector in these regions in an uncertain position - to fluctuate between times of safety when a reduced number of tourists are willing to travel, and times of active conflict, where lockdowns and violence prevails. This has impacts on the upkeep of ecotourism sites, as well as on the conservation of the natural resource base, especially those located in protected, remote and forested areas. Respondents noted that due to the conflict, these remote areas have been deemed as no-go zones, due to those involved in the conflict seeking refuge. Trying to clear these areas of inhabitants is not an option due to the volatility of the situation. Unfortunately, the extent of the situation is so severe that park management and authorities can no longer carry out their duties of monitoring and effecting conservation measures within the areas for fear of encroaching on the territory of armed conflict fighters.

On a personal note, it has greatly affected my job because I cannot go down to the forest as a result of insecurity. (Park management 3)

Apart from the dire safety concerns, this also highlights the impact on the conservation of the physical environment, flora and fauna. In Cameroon, many species are conserved by law, and consequently illegal to hunt. Many of these species are also traditionally protected, thus enhancing the conservation effort. The intersection of mainstream and traditional conservation leads to favourable outcomes, tapping into local acceptance and understanding. Furthermore, this approach accounts for the needs of locals, which also enhances acceptance and adherence to conservation measures. Respondents elaborated:

The species protected and most conserved are those forbidden by customs and tradition to be touched, and those highlighted by the government and international conservation partners as critically important to conservation. The list is long and varies from place to place. Uses of species vary. Some for food, medicine, construction, fuel and sales. (Park management 1)

Conservation does not totally prevent them (locals) from hunting for food security needs. (Park management 3)

However, those (illegally) occupying protected and remote forested areas are also subsisting off the land, inevitably hunting or consuming endangered and protected species of animals and plants. Forbidden activities like cutting down trees and burning fires, are also now common occurrences that compromise the conservation of areas.

The ongoing civil crisis has generated severe untold sufferings … it has also brought illicit and uncontrolled illegal exploitation of the forest for timber and charcoal with the fear of serious depletion of species, habitat degradation and a poor appearance for ecotourism. (Park management 1)

People fighting had to relocate to the forest to fight; so when in the forest they had to destroy the it because they were living on its resources and these are conservation areas, so there are prohibitions around hunting and maybe firewood, fire lighting. (Park management 5)

Authorities have acknowledged that there is very little that can be done to stop these activities, thus leaving conservation measures unresolved. Essentially, this amounts to a zero-sum game, where the tradeoff for the safety of authorities in charge of effecting and monitoring compliance with conservation, as well as local conservationists who act as custodians of the areas, is the halting of any enforcement of conservation measures, and the use of these sites as ecotourism attractions.

4.2.2. The impacts of climate change on ecotourism in Cameroon

The frequency of extreme weather events, rising atmospheric and sea temperatures, and seasonal variations have increasingly drawn attention to the issue of climate change as a crisis, that is currently happening on a global scale. In Cameroon, issues around climate change are acknowledged, with a respondent sharing their views on the various instances of climate change and the associated impacts.

Climate change has affected ecotourism negatively in that the tourism season is facing distortion, making planned event trips fail or tourist not seeing what they planned to, because of the sudden unannounced change of season, or weather. Considerable changes have been noticed in habitats trying to adapt to change in climate, with ecosystems destabilised and some species behaving strangely, like flowering at wrong times of the year. Some animals start developing new habits in feeding to adapt to the changes. (Government official 1)

A common concern related to climate change was the impacts of changing temperatures and weather seasons, resulting in changes in ecosystems and animal migration patterns. Any alteration to a component of an ecosystem inevitably has a domino effect. In the context of ecotourism, and climate change impacts, an example cited by a conservationist involved in tourism explained the impact of the changing seasons and temperatures on the migratory patterns of birds. Bird watching for certain species that traditionally roost in areas of Cameroon at certain times of the year coincides with tourists’ peak season for visiting and engaging in ecotourism. Now that changes in temperature and season have resulted in bird species finding a more suitable habitat, tourists who travel specifically for this activity are no longer attracted to the area, leading to a decline in demand for ecotourism in the region.

Considerable change in species population has been notice as result to climate change. In some areas, exotic invasive species are gaining ground in place of native species (habitat loss). Some animals are migrating due to lack of food shelter and security unstable ecosystem. (Park management 1)

A major concern that many respondents cited was the possibility of species extinction if the climate crisis is not carefully controlled. Respondents also acknowledged the importance of conservation and mitigation measures in reducing the chances of species extinction, and ultimately in a collapse of the ecosystem. Additionally, respondents noted that apart from the dire effects within the physical environment, there would also be severe impacts on the lives of locals who rely on these ecosystems for their socio-economic and cultural livelihoods.

The consequence of not conserving these species is extinction. (NGO 2)

Species are threatened or extinct and this impacts ecotourism. There will be unemployment of ecotourism actors, who cannot pay staff. This will have a huge negative effect on the economic chain. (NGO 1)

Extreme weather events, particularly heavier than usual rainfalls, have been cited by respondents as a worry. The coastal area of Limbe is prone to flooding when rivers overflow. This has been occurring with an increased frequency and is a dire threat to the safety of communities that reside in close proximity to areas that flood, such as close to the banks of rivers or on/at the foot of the mountains. A respondent explained:

The destructions that are caused by the effect of the climate change are very serious. During this past month, we experienced floods from down the mountain and that destroyed many facilities, many structures in governments office. Some people were relocated. This can also scare tourists knowing the risk of tourism in the mountain. (Park management 5)

The threat of flooding also affects the mobility of people, preventing them from travelling due to road networks that also flood. Similarly, due to many of the ecotourism attractions being in natural areas (like botanic gardens or protected areas), the same risks of flooding and safety concerns apply.

Heavy rains lead to bad roads and tourists cannot access tourist sites. (Quarter head 3)

4.3 Regeneration of ecotourism in Cameroon

In terms of the regeneration of ecotourism in Cameroon, the majority of informants interviewed were steadfast in their belief that there is a strong potential for ecotourism to be re-established and regenerated post-crises. Many respondents stated that the regeneration of the ecotourism sector will aid in addressing socio-economic and environmental issues that plague the country. However, this process needs to be facilitated through the development of proper policy that guides this regeneration and also mandates the meaningful inclusion of key stakeholders, such as NGOs, traditional authorities and local communities.

To grow ecotourism in Cameroon is to bring together all stakeholders to develop a National Strategy for Tourism Development and Marketing. (Government official 1)

As such, a call for collaborative management to support not only the regeneration of the sector but the daily operation of the sector too, was made by multiple informants. The role and involvement of NGOs were highlighted as crucial to the successful regeneration of the sector, given their ability to link various stakeholders and disseminate important information and education.

Locals learn about conservation and ecotourism through NGOs. (Quarter head 4)

NGOs carry out a lot of environmental education, reforestation and sensitization. (NGO 1)

NGOs always look at the site, encourage people concerning global warming and protect and conserve the natural resources we have around us. (NGO 4)

The channeling of adequate revenue into the refurbishment of existing or new infrastructure developments was also cited as important for regeneration, as a way of increasing the capacity of the host areas to accommodate tourists through a variety of products and services.

Despite the overall positive attitudes towards the regeneration of ecotourism in the country, the opinions of respondents were divided as to when regeneration can occur. Some cite the present, whilst others are mindful of the ongoing conflict and uncertainty as to when a resolution will be reached.

As Cameroon is known as Africa in one country, ecotourism has a very bright future when the crisis will end somehow … someday just like COVID-19. (Government official 1)

Other respondents were optimistic that the regeneration could begin immediately, given that the COVID-19 pandemic is officially over, and that the geopolitical crisis seems to have become less intense at the current time, resulting in travel within the regions being possible.

There is a very bright future for ecotourism in Cameroon despite COVID-19 and the ongoing civil crisis. (Park management 1)

5 Discussion

There are key issues highlighted by the results that need to be addressed or resolved before regeneration of the ecotourism sector can occur.

5.1 COVID-19 and the geopolitical crisis

In terms of COVID-19, the initial global lockdown did prevent the movement of tourists globally and thus resulted in a limited number of tourist arrivals into the country. However, even once international borders were reopened, other issues served to stymy the number of international tourist arrivals. This sentiment is echoed by Song (Citation2020), who noted the complexities of COVID-19 and the geopolitical crisis. This is a significant finding, as many of the tourists who engage in activities such as endemic bird watching are international tourists. Domestically, the government of Cameroon did not issue prolonged lockdown notices related to the virus. People were not prevented from travelling or visiting places or attractions in that regard. The onset of the geopolitical conflict gave rise to numerous internal or domestic lockdowns within the country since late 2016 (Lukong, Citation2020). Thus, Cameroon and the ecotourism sector have suffered through the effects of two different crises that occurred at the same time. Although both resulted in travel restrictions that were targeted at different groups of people, the safety concerns emanating from the geopolitical conflict deterred international tourists from visiting. In certain cases, countries issued safety warnings for their citizens who wanted to travel to the country or refused visa applications (Shaban, Citation2018).

All things considered, the major impacts of COVID-19 and geopolitical-induced lockdowns was the reduction in both international and domestic tourist arrivals. The knock-on effects of this on the ecotourism sector were a reduction in revenue generated from tourist fees and other payments, closure of ecotourism service and product providers due to a lack of demand, lack of maintenance of roads infrastructure and attractions, as well as a reduced workforce within the industry. Throughout the turmoil of crises, people who worked within the sector and industry were essentially jobless and were forced to adopt alternative strategies to support their livelihoods. The uncertainty in this regard has discouraged individuals from returning to the sector, opting for a stable livelihood practice like various agricultural activities instead.

Safety concerns related to traveling to national parks, remote and forested areas have become a major threat to ecotourism (Bang & Balgah, Citation2022). Until such a time that the conflict is resolved, these areas will be continuously occupied by conflict fighters who not only pose a serious safety threat to park management, conservationists and locals who need to access the areas to conduct management, effect conservation measures and attend to their cultural and traditional practices. This is currently not possible, leaving the extent of destruction to the physical environment, flora and fauna (which should be strictly conserved) unknown. Furthermore, given that the situation cannot be regulated, tourist safety in these areas cannot be guaranteed, leaving these areas inaccessible to tourists. Another issue on safety and inaccessibility of ecotourism hotspots that was raised by a respondent related to the insurgence of terrorism groups into protected areas. Many of the national parks and protected areas in the northern regions of the country have been seized by these groups, making them unsafe for ecotourists to visit. This has also served to shrink the ecotourism offering of the country, essentially amounting to a lack of accessibility and safety (Ngong, Citation2022).

5.2 Climate crisis

The climate crisis has been acknowledged by most informants, each of whom noted their observations of increased rainfall, flooding, changes in flora and fauna and changes in the marine environment. These are similar to problems that have resulted from climate change globally (UNEP, Citation2014; Chausson et al., Citation2020; Scott, Citation2021). The issue of safety of locals and tourists from extreme weather events is a key concern for the sector. Additionally, the ecotourism offerings of the sector are also experiencing certain changes affecting flora and fauna. Ecotourists who visit the region intending to view a specific species may no longer be able to do so, thus necessitating the need for a reevaluation of the sectors ecotourism product offerings, and how this can be built into the development of policy and strategic plans for the sector to ensure adaptability (Pyke et al., Citation2018). Cumulatively, these impacts will ultimately affect the local economic development of the regions where ecotourism is occurring, especially for locals who rely on the sector to support their livelihoods (Scott, Citation2021). Unlike the COVID-19 crisis which came to an end, and the geopolitical crisis which could come to an end if an amicable resolution is reached, the climate crisis is a global one that is being exacerbated by forces outside the control of tourism sectors, like that of Cameroon. Whilst mitigation measures in areas can be instituted, the risk associated with this crisis required constant monitoring and the ability to be adaptable. This should build an element of resilience into the sector (Pyke et al., Citation2018). Adaptability should extend to safety measures, but also to the ecotourism products on offer, to ensure that if a certain product is rendered unviable, it does not compromise the entire ecotourism economy.

Against the preceeding discussion, it is crucial that concept of conservation is given due consideration. Conservation of the natural environment, resources and the associated ecotourism products is essential (Wondirad, Citation2019), given the risks posed by the climate crisis. However, additional threats to the natural environment and resources are also posed by the use of them for traditional practices, such as hunting (Stronza et al., Citation2019). The intersection of conservation for ecotourism and preservation in the face of climate crisis, against the need to practice traditional livelihood strategies is a delicate balance that needs to be struck. This sentiment has been echoed by Samal and Dash (Citation2023) who note the fundamental importance of striking a balance between ecotourism, conservation and livelihood activities, with ecotourism having the ability to play a mediating role in the latter two activities.

5.3 Regenerating ecotourism in Cameroon

Reflecting on the issues that the COVID-19 pandemic triggered, the essential stoppage of the sector in certain regions - due to the geopolitical conflict and the additional challenges and threats emanating from the progressive climate crisis - there is an urgent need to reevaluate how ecotourism in the country is managed. All of these crises have happened or are happening against the background of what was an already constrained sector, with issues such as a lack of policy, fragmented management, a lack of collaboration among local stakeholders, a shortage of finance to aid the development and maintenance of ecotourism infrastructure and deficiencies in the strategic marketing of the country as an ecotourism destination (Kimbu, Citation2011; Harilal et al., Citation2019; Harilal & Tichaawa, Citation2020; Forje et al., Citation2021). Therefore, as the sector reopens, the opportunity to regenerate the development, management and operation of the sector should be seized, incorporating lessons learnt from recent years. There are repeated calls for the development of a dedicated ecotourism policy, which encompasses or provides a platform for the aforementioned issues from which to be leveraged.

6 Conclusion

The various crises have had a definitive impact on the ecotourism sector and on conservation the case study regions. These impacts also seem to extend to many other regions of the country, especially those that are at the heart of the geopolitical conflict, and as well as the regions where protected areas are in terms of climatic impacts. In terms of the geopolitical crisis, there have been ungovernable breaches of conservation regulations, due to warring parties living, hunting and fighting within the bounds of the protected areas. Species hunted by these parties to subsist off are classified as protected, but due to the nature of the conflict, there is no recourse. Unfortunately, there is no end to the crisis in sight. Recommendations for peace talks, as well as intervention from the international community, have not materialized or been fruitful. Therefore, the breaches of conservation measures and the constraints on ecotourism are set to continue. Interim measures that look towards creating safe zones for the ecotourism sector to grow and flourish could be considered as a measure towards regeneration of the ecotourism sector, however, this also rests upon a sort of resolution being reached.

In terms of climate change, two of the most prominent problems that the area seems to face are in terms of rainfall and the riverbanks flooding, as well as species extinction or changes to behaviour and habitats. This has resulted in many people being relocated from their homes, which are at risk of flooding and in fundamental changes to ecosystems, which are inherently characterised by endemic and indigenous species. Although both are problematic, the latter affects the core of the ecotourism product offering (Mkiramweni et al., Citation2017; Gühnemann et al., Citation2021). Whilst there is awareness around the impacts of climate change, the efforts are constrained in some regards due to a lack of revenue. This stems from the extended closure of the tourism sector, from both COVID-19 and geopolitical crises-induced lockdowns (Ekah, Citation2019; Anyanwu & Salami, Citation2021).

The ecotourism-crisis-conservation nexus is inextricably linked, making even a partial regeneration or reopening a complicated matter. It is from this junction that the significance and theoretical contribution of the current paper emerges, based on the consideration of the ecotourism sector and the associated matter of conservation in the context of the recent and ongoing crises. Previous studies conducted on ecotourism in Cameroon have been mostly based on the situation pre-COVID-19, with these studies focusing on the various impacts of ecotourism, as well as on the development of the ecotourism sector itself (Kimbu, Citation2011; Harilal & Tichaawa, Citation2018; Harilal et al., Citation2019; Forje et al., Citation2021). Additionally, given the sensitivity around the geopolitical conflict, there is a limited amount of research that focuses on it concerning ecotourism. Existing studies seek to provide insight into how the conflict emanated (Bang & Balgah, Citation2022). Similarly, research on the impacts of climate change from an ecotourism perspective is also scant.

The current research was conducted in two regions of the southwest province, both of which are ecotourism hotspots. However, this is only a small representation of the ecotourism sector in the country. Therefore, it is recommended that further research into this issue be conducted, to gain further insights that can be used on a practical level to regenerate the ecotourism sector in Cameroon.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anyanwu, J. C., & Salami, A. O. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on African economies: An introduction. African Development Review, 33(Suppl. 1), S1–S16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12531

- Atchombou, J., Shidiki, A., Tchamba, M., & Alexis, K. (2023). Opinion of stakeholders on the management of ecotourism in the Benue National Park of the North Region of Cameroon. Open Journal of Forestry, 13, 92–109. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojf.2023.131007

- Bang, H. N., & Balgah, R. A. (2022). The ramification of Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis: conceptual analysis of a looming “Complex Disaster Emergency”. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 7(1), 2–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-021-00110-x

- Bessa, E. A. Z., Ngueutchoua, G., Kwewouo Janpou, A., & El-Amier, Y. A. (2021). Heavy metal contamination and its ecological risks in the beach sediments along the Atlantic Ocean (Limbe coastal fringes, Cameroon). Earth Systems and Environment, 5(2), 433–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-020-00167-5

- Bhatt, K., Seabra, C., Kabia, S. K., Ashutosh, K., & Gangotia, A. (2022). COVID crisis and tourism sustainability: an insightful bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 14(19), 12151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912151

- Bixler, R. P. (2013). The political ecology of local environmental narratives: Power, knowledge, and mountain caribou conservation. Journal of Political Ecology, 20(1), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.2458/v20i1.21749

- Burgin, S., & Zama, E. F. (2014). Community-based tourism-option for forest-dependent communities in 1A IUCN protected areas? Cameroon case study. SHS Web of Conferences, 12((01067|1067)), 1. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20141201067

- Carvalho, J. S., Graham, B., Bocksberger, G., Maisels, F., Williamson, E. A., Wich, S., Sop, T., Amarasekaran, B., Barca, B., Barrie, A., & Bergl, R. A. (2021). Predicting range shifts of African apes under global change scenarios. Diversity and Distributions, 27(9), 1663–1679. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13358

- Chakraborty, A. (2019). Does nature matter? Arguing for a biophysical turn in the ecotourism narrative. Journal of Ecotourism, 18(3), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2019.1584201

- Chausson, A., Turner, B., Seddon, D., Chabaneix, N., Girardin, C. A., Kapos, V., Key, I., Roe, D., Smith, A., Woroniecki, S., & Seddon, N. (2020). Mapping the effectiveness of nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation. Global Change Biology, 26(11), 6134–6155. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15310

- Dube, K. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine-induced recovery and the implications of vaccine apartheid on the global tourism industry. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 126, 103140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2022.103140

- Ekah, E. R. (2019). The anglophone crisis in Cameroon: A geopolitical analysis. European Scientific Journal, 15(35), 144–166.

- Fletcher, R. (2017). Connection with nature is an oxymoron: A political ecology of “nature-deficit disorder”. Journal of Environmental Education, 48(4), 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2016.1139534

- Forje, G. W., Tchamba, M. N., & Eno-Nku, M. (2021). Determinants of ecotourism development in and around protected areas: The case of Campo Ma'an National Park in Cameroon. Scientific African, 11, e00663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00663

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Gühnemann, A., Kurzweil, A., & Mailer, M. (2021). Tourism mobility and climate change-a review of the situation in Austria. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 34, 100382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2021.100382

- Harilal, V., & Tichaawa, T. M. (2018). Ecotourism and alternative livelihood strategies in Cameroon’s protected areas. EuroEconomica, 37(2), 133–148.

- Harilal, V., & Tichaawa, T. (2020). Eco-tourism in Cameroon’s protected areas: Investigating the link between community participation and policy development. In M. Novelli, E. Adu-Ampong, & M. A. Ribeiro (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Tourism in Africa (pp. 311–328). Routledge.

- Harilal, V., Tichaawa, T. M., & Saarinen, J. (2019). “Development Without Policy”: Tourism Planning and Research Needs in Cameroon, Central Africa. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(6), 696–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1501732

- Harilal, V., Tichaawa, T., & Saarinen, J. (2022). Ecotourism and community development in Cameroon: The nexus between local participation and trust in government. Tourism Planning & Development, 19(2), 164–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2021.1995034

- Jamaliah, M. M., & Powell, R. B. (2017). Ecotourism resilience to climate change in Dana Biosphere Reserve. Jordan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(4), 519–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1360893

- Jaya, P. H. I., Izudin, A., & Aditya, R. (2022). The role of ecotourism in developing local communities in Indonesia. Journal of Ecotourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2022.2117368

- Kimbu, A. N. (2010). The non-prioritization of the tourism industry and its impacts on tourism research, development and management in the Central African sub-region. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 1(13&14), 51–62. https://openresearch.surrey.ac.uk/esploro/outputs/journalArticle/The-non-prioritization-of-the-tourism-industry/99511517302346

- Kimbu, A. N. (2011). The challenges of marketing tourism destinations in the Central African Subregion: The Cameroon example. International Journal of Tourism Research, 13(4), 324–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.853

- Kuščer, K., Eichelberger, S., & Peters, M. (2022). Tourism organizations’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: An investigation of the lockdown period. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(2), 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1928010

- Loveline, N. (2022). Barriers to women’s participation in tourism consumption in anglophone Cameroon: An intersectionality perspective. In E. Woyo & H. Venganai (Eds.), Gender, Disability, and Tourism in Africa: Intersectional Perspectives (pp. 195–210). Springer International Publishing.

- Lukong, P. (2020). Cameroon relaxes lockdown despite rise in coronavirus cases. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-05-01/cameroon-relaxes-lockdown-despite-rise-in-coronavirus-cases#xj4y7vzkg

- Manes, S., Costello, M. J., Beckett, H., Debnath, A., Devenish-Nelson, E., Grey, K. A., Jenkins, R., Khan, T. M., Kiessling, W., Krause, C., & Maharaj, S. S. (2021). Endemism increases species’ climate change risk in areas of global biodiversity importance. Biological Conservation, 257, 109070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109070

- Mbatu, R. S. (2009). Forest exploitation in Cameroon (1884–1994): An oxymoron of top-down and bottom-up forest management policy approaches. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 66(6), 747–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207230902860935

- Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife [MINFOF]. (2014). The management plan of the Mount Cameroon National Park and its peripheral zone 2015-2019. Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife, Cameroon. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/290571468007177234/pdf/E23260V30REPLA00Box391426B00PUBLIC0.pdf

- Mkiramweni, N. P., DeLacy, T., Jiang, M., & Chiwanga, F. E. (2017). Climate change risks on protected areas ecotourism: Shocks and stressors perspectives in Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Tanzania. In K. Backman & E. Munamura (Eds.), Ecotourism in sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 184–202). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315205205-12

- Ngade, I., Singer, M., Marcus, O., & Hasemann, J. (2017). Implications of changing attitudes towards game meat consumption at the time of Ebola in Limbe, Cameroon. Human Organization, 76(1), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.17730/0018-7259.76.1.48

- Ngong, T. H. (2022). The dynamics of Covid 19 pandemics, anglophone crisis on the hospitality facilities in the South West Region: Evidence from Buea and Limbe. Central Asian Journal of Innovations on Tourism Management and Finance, 3(9), 72–80.

- Novelli, M., Barnes, J. I., & Humavindu, M. (2006). The other side of the ecotourism coin: Consumptive tourism in Southern Africa. Journal of Ecotourism, 5(1-2), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040608668447

- Nunkoo, R. (2018). The state of research methods in tourism and hospitality. In R. Nunkoo (Ed.), Handbook of research methods for tourism and hospitality management (pp. 3–23). Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.

- Nyiawung, R. A., Bennett, N. J., & Loring, P. A. (2023). Understanding change, complexities, and governability challenges in small-scale fisheries: a case study of Limbe, Cameroon, Central Africa. Maritime Studies, 22(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-023-00296-3

- Nyindem, S. N. N., & Ndimofor, D. V. (2020). Linking language, knowledge and the environment: The case of plants in Bimbia. Journal of Arts and Humanities, III(3), 101–114.

- OCHA. (2018). Cameroon: South-West Region - A3 reference map. https://reliefweb.int/map/cameroon/cameroon-south-west-region-a3-reference-map-june-2018

- Ondicho, T. G. (2018). Indigenous ecotourism as a poverty eradication strategy: A case study of the Maasai people in the Amboseli region of Kenya. African Study Monographs. Supplementary, 56, 87–109. https://doi.org/10.14989/230176

- O’Reagan, V. (2022). White shark cage diving – plan to bring chumming closer to shore splits opinions. Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-09-26-white-shark-cage-diving-plan-to-extend-chumming-area-splits-opinions/

- Pellis, A., Lamers, M., & Van der Duim, R. (2015). Conservation tourism and landscape governance in Kenya: the interdependency of three conservation NGOs. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2-3), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1083028

- Pyke, J., Law, A., Jiang, M., & de Lacy, T. (2018). Learning from the locals: the role of stakeholder engagement in building tourism and community resilience. Journal of Ecotourism, 17(3), 206–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2018.1505586

- Ramaano, A. I. (2023). Alternative ecotourism perspectives within the protected conservation sites and farming communities amid environmental degradation and climate change-bound rural exercises. Forestry Economics Review, 5(1), 77–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/FER-11-2022-0011

- Sama, G. L., & Molua, E. L. (2019). Determinants of Ecotourism Trade in Cameroon. Natural Resources, 10((06|6)), 202–217. https://doi.org/10.4236/nr.2019.106014

- Samal, R., & Dash, M. (2023). Ecotourism, biodiversity conservation and livelihoods: Understanding the convergence and divergence. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgeop.2022.11.001

- Santos, K. D. S., Ribeiro, M. C., Queiroga, D. E. U. D., Silva, I. A. P. D., & Ferreira, S. M. S. (2020). The use of multiple triangulations as a validation strategy in a qualitative study. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25(2), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020252.12302018

- Scott, D. (2021). Sustainable tourism and the grand challenge of climate change. Sustainability, 13(4), 1966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041966

- Scott, D., Hall, C. M., & Gössling, S. (2019). Global tourism vulnerability to climate change. Annals of Tourism Research, 77, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.05.007

- Shaban, A. R. A. (2018). Canada issues Cameroon travel advisory over rising insecurity. Africa News. https://www.africanews.com/2018/09/26/canada-issues-cameroon-travel-advisory-over-rising-insecurity/

- Song, J. M. N. (2020). COVID-19 aggravates Cameroon's Anglophone crisis. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/covid-19-aggravates-cameroons-anglophone-crisis/a-53656656

- Stone, M. T. (2015). Community-based ecotourism: a collaborative partnerships perspective. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2-3), 166–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1023309

- Stronza, A. L., Hunt, C. A., & Fitzgerald, L. A. (2019). Ecotourism for conservation? Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 44(1), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-101718-033046

- Tichaawa, T., Idahosa, L., & Nunkoo, R. (2022). Local government trust, economic effectiveness and satisfaction in a tourism event context: The case of the Limbe Cultural Arts Festival. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 44(4), 1379–1388. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.44424-956

- Tichaawa, T. M., & Kimbu, A. N. (2019). Unlocking policy impediments for service delivery in tourism firms: Evidence from small and medium sized hotels in sub-Saharan Africa. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1556328

- United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP]. (2014). Keeping track of adaptation actions in Africa. Targeted fiscal stimulus actions making a difference. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). https://www.unep.org/resources/report/keeping-track-adaptation-actions-africa-targeted-fiscal-stimulus-actions-making

- Venkatesh, R., & Gouda, H. (2016). Ecotourism – planning and developmental strategies. Global Journal for Research Analysis, 5(12), 420–422.

- Walters, T. (2016). Using thematic analysis in tourism research. Tourism Analysis, 21(1), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354216X14537459509017

- Wardle, C., Buckley, R., Shakeela, A., & Castley, J. J. (2021). Ecotourism’s contributions to conservation: analysing patterns in published studies. Journal of Ecotourism, 20(2), 99–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2018.1424173

- Wondirad, A. (2019). Does ecotourism contribute to sustainable destination development, or is it just a marketing hoax? Analyzing twenty-five years contested journey of ecotourism through a meta-analysis of tourism journal publications. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(11), 1047–10655. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1665557

- Wonirad, A. (2019). Ecotourism development challenges and opportunities in Wondo Genet and it environs, southern Ethiopia. Journal of Place Management and Development, 13(4), 465–491.

- World Economic Forum. (2013). The Travel and Tourism Competititiveness Report 2013: Reducing Barriers to Economic Growth and Job Creation. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TT_Competitiveness_Report_2013.pdf [Retrieved 20 February 2024]

- World Meteorological Organisation. (2022). State of the Climate in Africa. chromeextension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://library.wmo.int/doc_num.php?expln m_id = 11512[Retrieved 15 May 2023]

- World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2018). Travel and tourism economic impact Cameroon. https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/countries-2018/cameroon2018.pdf