ABSTRACT

This paper explores the linkage between the expansion of commercial shark-fishing markets and the extension of migratory cycles of fishers in the West African Sub–region. The paper shows the societal deconstruction that occurred following the massive expansion of shark fishing over previous decades. It also points out that the approach of public decision makers and fisheries managers has contributed to the depletion of shark stocks, at the same time as contributing to a better appreciation of the current public fisheries policies’ limitations. Therefore, this paper aims to highlight the lack of efficiency during the emergence of this fishery in delivering a sound management framework to ensure long term sustainable exploitation of shark stocks. Sustainable exploitation through efficient management is yet to be achieved, in part due to the failure of current fisheries management models around the world, and despite the variety of legal instruments and management tools available. Finally, this contribution brings to the fore – a paradoxical reality – the fact that public policies for access regulation have led in many cases to the intensification of social conflicts for access to fishing grounds in West Africa.

Introduction

Shark fishing in West Africa has been undertaken as a commercial activity since the beginning of the 19th century, developed as a result of the growing demand for shark oil for lighting purposes. However, this period of development slowed following the invention of paraffin in 1830, which was considered a more suitable fuel. The second phase or period of expansion, which occurred during the years between the two world wars, was the incipient industrialisation of West Africa and the accompanying need for animal proteins for food and oil for medical purposes. This prompted increased shark fishing along the West African coast (Conti, Citation2004).

Over the two decades preceding 2010, the shark fishery underwent a third period of growth and occurred in response to the expansion of international markets for shark meat and, more importantly, the lucrative demand for shark fins in the Asian market (which retailed at about 350 euros per kg in 2013). Therefore, participation in the shark supply chain has once again become economically appealing for various operators, in particular, fishers, processors and traders (Failler, Citation2014). The economic success of the fishery has, however, been tarnished by the sharp decline of shark populations across the world, but with a particular significance in the West African region (Diop & Dossa, Citation2011). This depletion has essentially been caused by overfishing and is more than a little preoccupying as these long life-cycle species need to be at least 15 years old in order to reach sexual maturity (Failler et al., Citation2006).

The scarcity of shark resources and the establishment of protected areas along parts of the West African coast, has increased the distance fishers have to travel from their dedicated landing sites (Failler et al., Citation2015). While it enabled fishers to maintain some level of production, it was responsible for substantial social and economic conflicts with regards to resource access and markets (Failler et al., Citation2013). Attempts by policy-makers to regulate the fishery have largely failed. In part this has been due to a combination of the transnational dimension of the fishery and the lack of fisher organisations with whom the authorities can establish dialogue so as to develop effective management measures (Masumbuko et al., Citation2011).

This paper intends to examine the phase of development until 2010, and subsequent decline of the shark fishery, which even a decade later, represents a very lucrative industry in the West African region. It particularly focuses on the societal dimension of the evolution of this fishery. The first section of the paper notes the flexible behaviour of fishermen and the emergence of new strategies to cope with declining shark resources. The second section shows how migrations have led to structural changes within shark fishing communities – changes which have often resulted in intense conflicts between the parties involved. The third section looks deeper into gender issues, and how women who control the marketing of shark products are affected (and have reacted to the loss of supply). Public policy interventions, their effectiveness and the compliance of fishermen are discussed in the fourth section. The concluding section summarises the key findings of the paper and presents some policy options in order to help resolve the current crisis facing the Shark industry in West Africa.

The scarcity of sharks in the Sub-Regional Fishery Commission (SRFC) spaceFootnote1: Impacts on fishers’ practices and strategies

Actors involved and fishing practices

By the 1930s, shark fishing was of commercial interest in the West African countries of Senegal, Mauritania, Gambia, Guinea and Ghana. The exploitation of shark was undertaken to meet market demand for human consumption and also the extraction of oil for medical purposes. Despite the income generated by the activity within some fishing communities, the potential for overexploitation of stocks was mitigated by three factors. First, the meat had a very low commercial value and was usually caught as by-catch in mixed fisheries rather than being a target catch for human consumption. Second, the consumption of shark meat was not, and is still not, part of the traditional diet for most West African countries, with the exception of Ghana. Third, innovation and technological advances in the pharmaceutical industry reduced the reliance on shark oil as an ingredient for medical supplies. This, in particular, reduced the potential for overexploitation of shark, as the most lucrative use of shark was the extraction of oil for use in pharmaceutical products.

During the 1980s, a new market for shark developed: the smoked meat of shark. It originally began with producers in Burkina Faso exporting their output to markets in the Gulf of Benin, from which the industry spread progressively along the West African coasts in the quest for new fishing grounds. Nevertheless, the limited size of the land-locked country market kept the captures to reasonable levels (Sall, Citation2002).

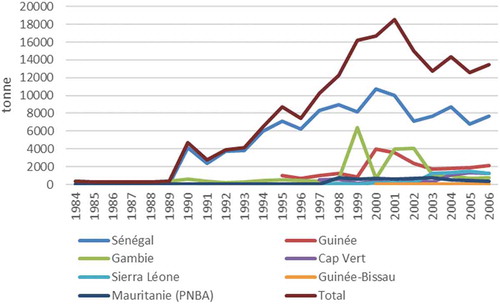

The demand for shark fin in international markets has burgeoned in recent decades (Clarke et al., Citation2006; Worm et al., Citation2013), particularly in Asia, where prices for fins have increased rapidly alongside increasing demand for shark meat within the European Union too as consumption patterns have changed. As a result, shark fishing developed as an important industry along the West African coast, most particularly in Ghana and Senegal, which led to the emergence of specialised fisheries. The major change that occurred is the fact that sharks became specifically targeted and no longer simply the result of mixed fishery by-catch. The industry is now well established and continues to grow quickly in the West African region −especially in the SRFC area. The contribution of Senegal is particularly important, accounting for more than 60% of aggregate landings as shown in below.

Shark has, however, not only been targeted by regional small-scale fishers. The EU has also largely contributed to the decline of shark stocks through its own intensive fishing and trading activities (Le Monde.fr, Citation2007). Within the EU, Spain, France, the UK and Portugal are the main shark fin producers/traders, and respectively caught: 50,000, 22,000, 15,000 and 13,000 tonnes of the EU total shark catch of about 110,000 tons in 2008 (FAO, Citation2010). Part of the European fleet targeting shark, mostly comprising Spanish vessels, has been active in West African waters for some time. In the SRFC area, the industrial shark fleet comprises mainly of trawlers, long liners and seiners, operating in the context of international fisheries agreements between the SRFC Member States and the EU (Binet et al., Citation2013). However, additional foreign long-distance fleets (mostly Japanese and Korean) have also operated under fisheries agreements in SRFC countries’ EEZ (Stilwell et al., Citation2010). Studies have reported that spatial and technological competition between the industrial and the artisanal fisheries sectors contributed to increased pressures on shark stocks in the SRFC EEZ (Diop & Dossa, Citation2011)

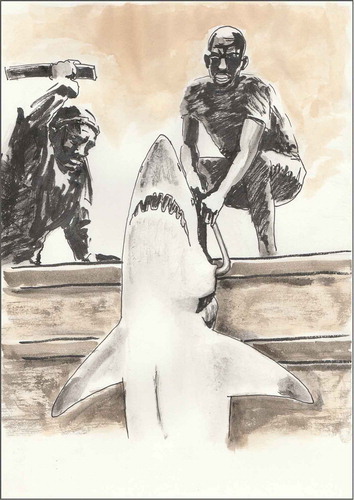

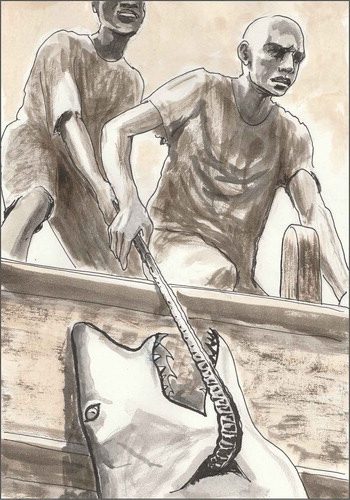

In the case of the shark fin fishery, fishers often dispose of the carcass after removing the fins. This is done for one reason. Discarding the carcass leaves more room onboard for additional valuable fins and so maximises the value of the catch, rather than landing shark meat as part of the total catch which has a low market value. In some cases, however, both meat and fins are utilised (see ).

Table 1. Valuing sharks onboard EU long liner freezers

The status of shark stocks

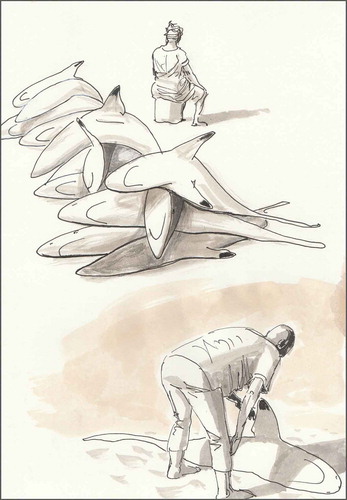

Shark finning, and the subsequent discard of shark carcasses, has significantly contributed to the depletion of shark stocks. The overexploitation of shark has been conducted by EU vessels and artisanal fishers alike. In the case of artisanal fishers, the quantity of meat retained on board depends on the quantity of shark fins collected during the fishing trip. For this reason, fishers start the salting process after a couple of days at sea and one week or so before they return home.

The results of a survey conducted in 2005/6 by PSRA-Sharks, in collaboration with Noé Conservation, indicated that the population of sharks had declined massively over the past two decades. Estimates suggest that 20% of the 69 species of sharks and rays surveyed in the SRFC area were threatened by the end of the first decade of the 21st century, with some species that were once found across the whole sub region later only seen in one country. This is the case with the Common guitarfish (Rhinobatos rhinobatos sp) and African Wedgefish (Rhynchobatus luebberti sp.) which can now only be found in Mauritanian waters. The survey also indicates that some species, such as sawfishes (Pristidae) had – with the exception of the Bijagos Archipelago in Guinea-Bissau and the maritime coastal zones of Sierra Leone (see ), disappeared altogether from SRFC waters. presents the status of 14 shark species historically found in the SRFC region in 2010.

Figure 2. Map of West Africa region showing camps in which fish is processed beyond the borders of Senegal before being marketed

Table 2. List of shark and ray species considered in danger

How do fishers cope with the decline of shark stocks?

The strategies developed by artisanal fishers to cope with depleted stocks are three-fold. The first strategy consists of increasing fishing effort through the adoption of more efficient fishing technologies. One example of this is the greater use of driftnets, despite them being banned by certain fishing administrations, as is the case in Senegal.Footnote2 While the Ghanaians have a long tradition of using driftnets, in countries such as Senegal, Mauritania and Gambia, shark fin traders played an important role in the introduction and the dissemination of this type of fishing gear.

The second strategy relates to greater specialisation. Since the 1990s, some segments of the fishing fleet have converted their vessels to target shark exclusively, rather than targeting shark for only part of the fishing season. As fishing effort has increased, fishers have moved to remote fishing grounds in the pursuit of the once easily caught shark. As the duration of fishing trips tends to be longer, deterioration of meat and fins without preservation in salt would reduce market prices, thus the demand for salt has also increased significantly. These factors have led to boats being built to reflect the changing nature of the industry. It is now common place to see 20 m canoes fishing remote waters for shark.

These larger canoes have allowed fishers to target new unexploited fishing grounds along the west coast of Africa, fish offshore and even to enter the open ocean. In some cases, this had led to the landing of new species, and also bigger specimens than have been caught in the past. Targeting of larger species has also induced innovation within the industry. For example, long liners have replaced nylon lines with recycled motorcycle brake cables. As for the industrial fleet, the lucrative shark fin and shark meat markets have induced important changes too. The Spanish long liner freezer vessels, which had previously targeted sword fish off the Atlantic coasts in the 1980s, report shifting their fishing effort to shark since the 1990s. Finally, the increasing demand for shark fin in Asian markets on the one hand and high demand for shark meat in the EU on the other hand has led to the development of new search strategies, in particular, finding new fishing grounds with the help of experienced fishers. These fishers were found amongst small-scale West African fishing communities specialised in shark fishing (Failler & Binet, Citation2010). With this knowledge, industrial vessels, primarily Spanish, have since sailed from West African waters up to the Pacific waters, via the Indian Ocean, in order to catch shark. With income generated by shark catches as the primary goal, these Spanish vessels have further incentivised productivity of crew with bonuses for larger hauls.

Social change induced by shark market expansion and fisher’s migration

Migration of fishers has, historically, been a common practice in West Africa (Failler & Binet, Citation2010). Migration was once aimed at shadowing the trajectories of small pelagic stocks along the coast. More recently, migration has been conducted as a result of resource scarcity for a certain number of species on traditional fishing grounds, including shark (Failler et al., Citation2020). This spatial relocation of fishing activity has not only impacted on fishers living and working conditions, but migrations relating to the shark fishery have provoked a deep transformation in the social organisation of migrants and related communities. This may be better appreciated through a number of selected qualitative examples: (i) organisational change and its gender impact, (ii) the effect upon labour contracts and the way crew members cooperate formally on board the fishing units and (iii) the intensification of internal and cross border conflicts over resource access.

(i) Social organisation changes: gender impact and women’s strategies to sustain income

Women’s’ social status, power and roles are essentially founded on the sexual division of labour in the fisheries. In the West African shark fishery, the role of women and their social status is defined by a number of key relationships. First, women played a pivotal role in the micro-financing of fishing units. Women contributed significantly to the supply of informal credit required by fishers for their fishing trips (including fuel, bait, nets etc) and related social needs (baptisms, weddings and burials, for example). These funds generally originated from tontines (informal rotating credit funds/saving systems) and income generated by female participation in the spheres of fish processing and marketing.Footnote3 The inability of conventional financial institutions to respond opportunely to artisanal fishers’ credit needs led to the predominance of women in this niche credit market. This has occurred despite the gradual integration of small-scale fisheries into international fish markets (both for fresh and processed fish).

Second, as the main actors in the artisanal processing sector, women have historically been responsible for the handling and processing of the fish, which is considered as a feminine task. This reflects partly the sexual division of labour in the fisheries and, also because of the climate induced migration, caused by repeated droughts in the 1980s, of men into the fishing industry. However, this inflow did not modify the predominance of women in the post-harvesting segments. Third, with the exception of Ghana, women have always had full control over the marketing of salted shark bodies in West Africa, salting and storing shark so as to ensure a year-round supply. For example, important quantities of salted shark marketed in Senegal by Guet N’darian women from Saint Louis, is processed by women in camps located beyond the Senegalese boarders such as Nouadhibou in Mauritania, Brufut in Gambia and Bissau in Guinea Bissau ().

This strategic position of women in the shark value chain was already visible in the early 1940s, when the first European companies were established in Saint- Louis and M’Bour (Sall, 2006). Indeed, settlement of these European export-oriented shark units was made purposely to take advantage of women’s local knowledge, know-how and expertise in the post-harvest processing of shark (Sall, 2006).

However, where the shark chain previously enhanced women’s social status through their pivotal role in the informal financial markets (micro – financing), processing and marketing sectors since the early 1940s, their social position is now being contested. This is largely a consequence of the new migration dynamics alluded to in the preceding section of this paper.

First, the lengthening of fishing trips – due to local resource scarcities – has increased the physical distance between fishing units and women. As a matter of fact, the origin of migrants has increasingly differed from the landing sites they are now using (which are mostly located in urban centres).

The overexploitation of sharks has been exacerbated by several operational improvements. Although shark fishing grounds has changed over the years, it is now possible to land into ports all along the coastline. The increased number of landing sites has helped to offset increased operational costs faced by fishers that are now forced to fish further offshore in order to remain economically viable. One method commonly used by shark fishers to offset high fuel costs is extending fishing trips. Fishers operating beyond the maritime border between Mauritania and Sierra Leone have thus been able to contribute significantly to smoked and salted and dried shark chain along and across the West African coast.

During the late 1980s, masculine operators originating from Burkina Faso established themselves in the shark fishery value chain. They became an important part of the segment of the value chain which collected and smoked the meat for large firms established in West Africa. They later joined the Ghanaians who were already very active in the sector all along West Africa since the late 1960s. Compared to Ghanaians, the Burkinabe operators functioned in collaboration with trading companies able to provide financial support to their activities. This enabled them to access property on land for development and the installation of shark smoking facilities ensued. The utilisation of Burkinabe workers occurred in many countries, including Gambia, Senegal, Mauritania, Guinea-Bissau and Guinea. Given their financial capabilities, they progressively evolved from the status of settlers, where their activity was limited to smoking shark meat to vertically integrated operators, responsible for several segments of the industry. Some of the Burkinabe workers have since become fishers and owners of shark fishing units. Women from the fishing communities were not able to compete with these new operators and they subsequently lost power to this segment of the industry in many landing sites. This empowerment of land migrants in the shark industry by formerly landlocked inhabitants provoked much conflict with women, who were not willing to be forced out of the industry. These conflicts, catalyzed by the depletion of resources, and subsequent decrease in supply, led to loathing and conflict towards foreign migrants in certain locations. This was particularly seen in Gambia, and in certain sites in the Casamance region, south of Senegal, where there was a concentration of stakeholders coming from multiple countries. The conditions for accessing raw products was made difficult for local women when fishers were migrants or when fishing was funded by external sources. In these cases, the priority formerly given to women for selling the production was questioned. Finally, external operators that entered the post-harvesting sector of the shark fishery deeply modified the local ownership structures, leading to the rupture of the formerly important linkages between linage, ownership and real estate property.

Since the 1990’s, most landing sites for shark fins have been concentrated in Gambia and therefore all fishers from the sub region, tend to land shark catches in Gambia. This concentration of landing has stemmed from the higher value of shark fins. As a result, fishers do not land their production in other countries, further impacting the market once controlled by women outside of Gambia. After the 1990’s, the only operators competing with women in countries other than Gambia have fish plants exporting fresh shark meat to the EU markets.

In order to guarantee income generated by the processing sector, women have responded to the loss of supply through various strategies. The first strategy consisted of setting up local associations to defend their interests. In communities like Guet N’Dar, Senegal, women have set up local organisations in order to control the supply of shark meat to traders coming mainly from the sub-region. In the context of de–regulation in the shark market circuits, it is the only case where they have succeeded in maintaining a formerly crucial role in the processing and the marketing of shark meat. Their continuation in the chain has been permitted by (i) their role in the emerging market for meat salting and drying; (ii) the proximity with Mauritania where fishers from Saint- Louis have conducted shark fisheries without access right thus forcing them to land in Mauritania, essentially where women allow the illegal fishing as long as they land in their ports. This constituted an interesting opportunity for women to ensure a more or less stable access to raw products. At the main landing site of Guet N’Dar, there are two associations whose mandates for affiliated members are (i) to collect all the processed products and (ii) putting the collected products on sale together. The main purpose of this is to protect prices.

Other attempts to combat the reduced supply women face revolve around diversification. For example, in Joal and M’Bour, two main fishing ports in Senegal located south of Dakar, many women have invested in the octopus fishery during the cephalopods fishing season. Many women who diversified their activities have reaped the rewards. Further diversification sees benefit in further involvement in the processing of sardinella and ethmalosa after the cephalopod season. A further example is the gradual specialisation of women in gastropod, locally named Yet (False Elephant’s Snout; Cymbium), processing. Fishing of this species was considered a feasible diversification activity. The change was enabled by (i) the interesting commercial value proposed by Asian market outlets for frozen products and; (ii) the increase in landings – despite the rarefaction of this species – resulting from the expansion of the trans-shipment at sea from industrial fleet to artisanal fishing units. Increases in production thereof has been supported by the vast number of product collectors from freezing facilities based in Dakar.

The revenues of the shark fishery in the context of rarefaction

Shark fishers using nets are those characterised by a stable income sharing system that is still maintained today. In the Senegalese case, over the years and despite the context of globalising markets, the system prevailing is: 1/3 for the net; 2/3 divided by crew members (the craft and the outboard each receiving a share as active ‘crew members’). This tradition of revenue shares prevails in fisheries using purse seines, gillnets and driftnets. During fishing campaigns, while settling far from their communities, the system is maintained (Deme et al., Citation2010).

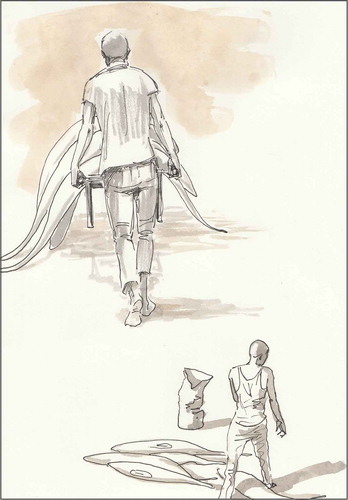

There are several characteristics common to the early migrants that moved for shark fishing. The first of these is that shark was caught seasonally. Then, most of the crews were composed of fishers owing to the same lineage, where the crew number did not exceed 4 to 5 and the fishing boats were not more than 8 to 10 m in length. Second, fishers migrated and brought families who settled in temporary camps where women were responsible for the salting and drying of sharks, which were caught as part of a multi-species fishery. The shark products were then marketed at the end of the season once the fishing units were back in their country.

Since the 1990s, migratory cycles have changed significantly, influencing and transforming labour contracts. This has been caused by: (i) technological advancements accompanying the dynamics of the value chain expansion – the introduction of mono filament driftnets having replaced gillnets, the introduction of fishing units of minimum 20 meters in length and the onboard processing fishing units; (ii) the rarefaction of shark combined with the increase in transaction costs; (iii) the deterioration of shark fishers’ working conditions along with the augmentation of fishing trips up to 21 days at sea; (iv) the increased risk associated with sustaining production in foreign EEZs exposed to changes in political and economic conditions – especially now many states have set up new access regulations; and (v) the question of the profitability of fishing units.

These changes have led to the development of new forms of cooperation between boat owners and crew members. The factors cited above have therefore prompted an increase in labour mobility so that profitability is maximized. Indeed, migration often occurs when rapid assessment of profitability has been conducted – fishers need to find the right balance between substantial increases in catch and the associated operational costs of fishing remote grounds. The former long-term working contracts have been gradually replaced with short term labour contracts. This has resulted in the dissolution of extra-professional relationships between owners and crew members. As a corollary, owners cannot afford to endorse certain social costs such as the lodging and the feeding of crew members anymore. This change has therefore intensified labour mobility. To overcome recruitment problems, some owners have developed strategies for attracting workers into the fishery. For example, Ghanaian owners have modified the way the capital is set up – the owner brings the fishing unit (boat and other equipment) and the crew members bring the driftnets. The sharing system is adapted in a way to give further incentives to crew members to continue fishing, as they receive all shark fins as in-kind incomes while the shark meat is for the owner. These practices are well endowed now within Ghanaian and some Senegalese shark fishermen established in the south of Senegal as well as in Mauritania, Gambia and Sierra Leone (Sall, 2006).

Internal and cross-border conflicts over access as a result of stock depletion

It is noticeable that the occurrence of fishing conflicts is correlated with the rarefaction of resources. The shark industry has a long history in West Africa and since the 1930’s, shark fishers cohabited peacefully with other fishers and no specific social tensions were apparent. However, since the development of the shark fin market in the 1990s, conflict between fishers has been apparent, particularly since the devaluation of the CFAFootnote4 from 1994. This devaluation marked an intensification of conflicts between fishing communities at both national and transnational levels. In Guinea Bissau on the Bijagos Archipelago, cohabitation of Senegalese migrants and local fishers has led to many conflicts for access to fishing grounds. Conflict has also arisen between Mauritania and Senegal where migrant fishermen’s unremitting efforts to maximise profit from the shark fishing industry incite them to take the maximum risk.

Remarkably, fishers do not hesitate to operate illegally in order to maximize profits. Thus, illegal unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing practices are very common among migrant workers in the West African Shark fishery. These illegal practices mostly revolve around fishing in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) or fishing in foreign waters without paying any fees. The maritime border between Senegal and Mauritania is one of the most important sites of conflicts. The situation is worse in some areas, such as around the isle of Sal, 1 km north of the Senegalese village of Saint- Louis and 18 km south of the Mauritanian village of N’diago (Diop, Citation2006). The intensification of conflicts between Senegalese and Mauritanian fishers in terms of access is illustrated by the permanent effort provided by the Senegalese government to negotiate the restitution of Senegalese fishers’ fishing gears seized for illegal practices in Guinea Bissau and Mauritania.

As for internal conflicts, the case of Kayar is interesting since it has been the most violent conflict for access to fishing grounds in the history of Senegalese fisheries. It is the first time that human violence originating from conflicts led to death. In 1989, after the conflict between Senegal and Mauritania – for terrestrial border sharing – shark fishers from Senegal established in Nouadhibou and Nouakchott had to flee Mauritania. Some of them – using driftnet and targeting exclusively shark – transferred their fishing effort back to domestic fisheries. In 1994, with the devaluation of the CFA franc, coupled with the expansion of the shark fin market, saw a substantial amount of fishing effort transferred to Kayar. This transfer was caused by the presence of an important shark stock, especially during the wet season. This influx of fishers in Kayar, where local fishers are specialised in hooks and lines, led to conflicts for access to fishing grounds and conflicts between line fishing and driftnets. Conflicts with migrants, and in particular those of Guet N’dar in Saint Louis, were severe and necessitated intervention of military forces in order to avoid a generalized conflict that had already resulted in several deaths.

Conflict between women of different nationalities for land access at the level of processing sites: a process activated by public policies at micro and macro levels

West Africa has been subject to a massive concentration of the population along the coasts. This is mostly due to the rural exodus that followed repeated droughts in the 1970s, which forced populations to abandon agriculture and find another source of revenue. As a result, the seashore has seen a lot of conflict deriving from concentration of activities along the coast: fishermen in need for space to haul their crafts, processors, industries, etc … Traditionally, the spatial conflicts generated are softened by the existence of community-based social regulations systems. The expansion of shark markets has encouraged an intensification of those conflicts. This new situation emerged in relation to important events in the area.

First, in the 1980s, growth in the smoked shark market led to an influx of operators – such as Burkinabe and Soussou from Guinea – who became established at some processing sites: Casamance, Saint- Louis, M’Bour and Joal in Senegal, as well as Brufut and Banjul in Gambia, for example. This migration is supported and cautioned by the ECOWAS legislation regarding the free movement of goods and people within this region. In a bid to enter the smoking process and gain market control, migrants must first insure access to land in order to install ovens and build houses. Local women are very influential and resistant to the settlement of these migrants, who have to adopt various strategies to preserve their interests. For example, Burkinabe who are very active in the smoking of shark and supplying West Africa have joined the National Association of Burkinabe based in Senegal; the chairman being a Burkinabe national and a Professor at the University of Dakar.

Second, in the 1990s, the double dynamic deriving from the West African states’ policies regarding free movement across borders in the frame of ECOWAS on the one hand and the decentralisation process on the other intensified conflicts. In 1996, the law on decentralisation came into force. From then on, certain communities gathered in municipalities. This administrative process greatly modified traditional access rights to land. On the one hand, the central authority did not make sufficient funds available in order to build capacity of the municipalities, and the land market has therefore become a lucrative source of speculation for them. Thus, given the poor finances of many municipalities, the guaranteed land income generated by speculation on land market contributed significantly to increased municipalities’ budgets. On the other hand, the installation of municipalities engendered ‘conflict of competence’ between the traditional system in charge of land access regulation and the municipalities. If these two systems are still cohabitating in some fishing communities, the general trend is that the managing of land access on the coastal lines is gradually transferred to mayors.

Public polices interventions, their effectiveness and the compliance of fishermen

For the implementation of the FAO international plan for the conservation of sharks, the SRFC states’ members have set up programmes based on a set of legal instruments. For this purpose, Senegal and Guinea officially approved their National Plans for the conservation of Sharks and Rays in 2005 and 2006. Environmental NGOs and members of PRCM (Marine and Costal Resources Conservation Programme composed of Wetland, IUCN, WETLAND and FIBA) are contributing indirectly to these public actions, through the implementation of Marine Protected Areas in the Sub region. Despite the recognition that shark stocks are in a state of decline, both by states’ fisheries officials and stakeholders, measures have greatly suffered from a lack of effectiveness. As a response to these regulations put on the shark fisheries alongside facing the need to sustain their levels of production, fishers tend not to comply with new regulations.

Assessment of public policies’ effectiveness

As measures taken by the Ministries of Fisheries to protect SRFC waters are not well enforced, they are generally not complied with, and the exploitation of sharks is expected to continue.

Fishers continue to target shark for their fins even though it is prohibited, and they also enter MPAs in order to fish illegally though access by commercial fishers is strictly forbidden. Furthermore, the continued use of driftnets – officially banned in most of the SRFC states from the 1990s – illustrates the failure in the implementation of such management measures.

In this context, it is important to be more realistic while assessing the real outcomes of the joined efforts by fisheries administrations and environmental NGOs to protect stocks. Despite the collaboration between authorities and NGOs, the outcomes are far from expectations. Apart from the Banc de Arguin National Park (PNBA) – MPAs in Mauritania are not sufficient to prevent continued overexploitation. In the case of the PNBA, surveillance is not as efficient as it could be with the incursion of certain fishermen, those being Senegalese migrants and Mauritanian national fishermen.

Further to this lack of enforcement in the MPA, the relative success of the MPA is due to the credit of highly political preoccupations, prerogatives and interests as opposed to being based on fisheries officials’ efforts or the environmental NGOs’ lobbying actions (Failler et al., Citation2010). In fact, the Mauritanian government has always given great importance to this area not least because of National territorial integrity and security purposes.

The reasons attributing to the failure of the implementation of regulations applied to the shark fisheries in West Africa at the time of development are of different orders such as:

Socio – cultural considerations: fishing communities are exploiting the species for short term economic gains rather than longer term sustainable yields, where the decline and potential extinction of certain stocks are only seen as a part of the tribulations of nature.

Scientist’s assessments of shark stocks are not taken into account by stakeholders. The lack of support for reports on the stock health stems from (i) their negative experience of recent octopus fishing closures in Mauritania and SenegalFootnote5 for what, in fishers’ minds resulted from a lack of scientific knowledge on the species (ii) the shark conservation plans at the SRFC level were not prepared based on in-depth biological assessments and the economic and social impacts of the measures are not fully understood

The lack of credible fishing organisations that can contribute to dialogue between public decision-makers, researchers and industry stakeholders. This is imperative for the implementation of measures concerning any attempts to introduce new access regulations. This discrepancy in the fishing organisations can be highlighted by two points: First, the outcomes expected from MPAs (such as the PNBA) are permanently mortgaged by the way Mauritanian national fishermen’s representatives subcontract Senegalese migrants in order to go on practicing shark fining for them. Second, none of the fisheries’ organisations at West African level have the minimum legal recognition required to ensure the relay of opinion. Thus, there exists a real need to have organisations or social institutions able to participate in the enforcement of management measures. Most of the fishing organisations have taken on a role of maintenance of institutional prerogatives rather than be promoters of concrete and efficient actions capable to lead to the implementation of sound public policies. For as long as the official representatives have exclusivity in determining policy, and remain the only bodies recognised by public decisions makers, efforts by environmental NGOs for the conservation of shark will remain unsuccessful.

The absence of a real (public) power coercion at state levels. Fisheries administration officials do not recognise a certain level of powerlessness, and those who do, often accept it. Thus, the failure in the implementation of a set of legal instruments (such as the fisheries code in many West Africa countries) is due to the socio-cultural context where communities oppose the powers above which aim to control what they see as their culture (the ‘power of culture’).

A paradoxical impact deriving from states’ fisheries’ measures for controlling migrant fishers: the introduction of licence fees for migrants and the obligation to land catches in countries where the licences are issued has increased unreported catches and made it more it difficult to monitor shark fisheries.

The existence of social, political and economic constraints to the necessary re-conversion of both stakeholders and economic operators involved in the processing and marketing of shark. In fact, whereas in certain countries there are entire economies based on the species (in Ghana for instance), the redeployment actions proposed until recently are very minor in the face of the sheer size of the required funds. The necessary capital used to integrate the shark industry and the incomes generated are very different from one actor to another. For this reason, the funds provided in order to help the redeployment of Mauritanian shark fishers and ImraguenFootnote6 women involved in the processing of shark are insignificant for shark fins wholesalers established in the chain since the 1980s (Sall, Citation2007).

Fishers’ behaviours regarding fisheries public policies

Fishers need to maintain a level of production which affects the adoption of new strategies for them. The way they behave and react confirms the fact that public policies, instead of improving the access regulations, have led in many cases to an increasing number of offenders. As mentioned earlier, the main illustration of this is the common use of driftnets in the shark fisheries, despite use of driftnets being banned in SRFC. In fact, it appears that the use of drift nets has increased at a higher rate since use was banned under the new Fisheries Code. Fishing units are given maximum autonomy at sea in order to escape control. The widening of fishing units enables the processing of shark meat and the storage of shark fins during the migratory cycle. Such a strategy is the most appropriate response to the banning of landing shark fins in certain countries, it is the only alternative to benefit from resources depending on foreign States’ jurisdiction without paying fees. It is the case of many migrants.

Consequently, routes have been deeply modified. There is less and less contact with land in foreign countries where shark stocks are exploited. Fishers are no longer based in fishing camps and they spend as much time as possible onboard their canoes, sometimes up to 20 days at sea.

The remoteness of fishing ground has forced fishers to further adapt. Indeed, higher costs for fuel have led to the development of multiple landing sites in the countries where fishing is conducted. For this reason, they have contributed to the emerging and expanding shark processing market along the West African coast.

Conclusion

The Shark fishery in West Africa has reached a critical point; its sustainability is under question at social, environmental and economic levels, threatened in primarily by the rarefaction of the species. From a social perspective, the deconstruction of the shark value chain has led to the building of a new form of chain. This change has had gender impacts, through the loss of power of women, formerly conferred by the control they used to have on the processing and marketing sectors. This change has been caused by the emergence of a new category of operators attracted by the expansion of the shark meat market since the 1980s and in particular the shark fin chain in the 1990s. In addition to social deconstruction, shark stock decline has been a driver for intensive conflicts over access at internal and cross-border levels. Along with these conflicts, new forms of migration have emerged to combat the decline in stocks and new management measures applied, based on longer remote trips at sea where fishers stay onboard for the length of the trip. This has also led to a substantial decrease in working conditions and safety at sea. This new form also revolves around the IUU fishing practices in order to maximize profits.

From an economic perspective, the profitability of such fisheries is under question. The transfer of fishing effort formerly oriented to species for the supplying of local markets toward fishing for shark fins, given their high commercial value, is not justified anymore. The shark stocks are threatened, and some are at risk of extinction. This situation is the result of the combination of (i) the extraordinary expansion of shark’s fin markets from the 1990s, (ii) the lack of monitoring, (iii) stakeholder doubts on the scientific advice regarding the sustainable exploitation of stocks, (iv) the survival of fishing communities’ cultures and (v) the lack of credible fish worker representatives having the required legitimacy to represent and protect communities.

Given this situation, and the poor effectiveness of current public policies on the conservation of shark stocks, new approaches are necessary. They require to evolve methods used to implement existing legal instruments and management measures rather than design and implement new ones. As a matter of fact, proposed plans for the conservation of sharks issued by Guinea and Senegal require effort in order to be effectively implemented. In order to stop and reverse the current trends observed in the shark fishery and the decline of related stocks, the imperative actions to undertake will be (i) the participation of SRFC states and environmental NGOs in the conservation of sharks through two main frameworks already developed and very much relevant to the Sub region: the FAO Code of Conduct for responsible fisheries (Hosch et al., Citation2011) and the Johannesburg Plan of Implementation; (ii) the implementation of legal instruments ratified by states in the framework of international organisations such as the United Nations must be part of official commitments in international fisheries cooperation agreements; (iii) the conducting of a specific case study of the SRFC area level on the social and economic costs induced by expansion of shark markets will be relevant to convince both stakeholders and actors involved in the processing and the marketing of shark products on the aberrations of such a chain (iv) the redeployment of actors involved must be seriously supported by national authorities and financial institutions must be set up to accompany the redeployment process, which requires significant planning and development (Failler & Pan, Citation2007); and (v) better communication between decisions-makers, scientists and stakeholders (Christensen et al., Citation2011).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aliou Sall

Aliou Sall, is a researcher specializing in the development studies in the field of fisheries. He is the director of the NGO called CREDETIP, formed in 1989 and based in Senegal whose purpose is to provide support to fishing communities. Aliou is also serving as the vice-president for Mundus maris, a non-profit organization that provides scientific and relevant indigenous knowledge and encourages artistic expression about the sea in order to promote its restoration, conservation and sustainable use.

Pierre Failler

Pierre Failler is the Director of the Centre for Blue Governance. He holds a PhD in Economics, an MSc in Economics of Marine Resources and a Master in Philosophy. He is coordinating complex research projects with multidisciplinary teams for more than 25 years in Europe, Africa, Asia, Caribbean and Pacific coastal countries (more than 40 to date) in collaboration with national research institutions and universities and a close link with policy bodies. He has recently coordinated the Blue Economy Strategy for the African Union, the Regional Action Plan for the Blue Economy of the Indian Ocean Commission, the Blue Economy Strategy of the Intergovernmental Authority for development (IGAD) as well as the Blue Economy Strategy for the Bangladesh, Seychelles and The Bahams. He has authored and co-authored about 350 journal articles, book chapters, research reports, consultancy reports, etc. He is also a Scientific evaluator for several research councils in UK, Europe, North America, Africa and Asia.

Ben Drakeford

Ben Drakeford is a Senior Lecturer in Economics at the university of Portmouth and a researcher at the Centre for Blue Governance. He has a PhD in Fisheries Economics and Management. His main academic interests lie within the field of Blue economy and governance. He was recently the UK lead on a DG Mare initiative on developing blue growth opportunities in the Atlantic Ocean. Ben is the author of numerous papers on the European fisheries.

Antaya March

Antaya March is a research assistant at the Centre for Blue Governance. She holds a Msc Coastal and Marine Resource Management and works on fishery, blue economy and coastal zone management.

Notes

1. The SRFC includes 7 countries: Mauritania, Senegal, Cape Verde, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Guinea and Sierra Leone.

2. The use of this gear is most common in Senegal although its utilization has intensified greatly since its actual use was outlawed by the national ‘Fishing code’ of 2000.

3. Incomes generated from these – and other – activities (such as fish marketing) were generally then re–invested, partly in fisheries and partly for social reproduction needs (children’s education and schooling, household primary needs).

4. CFA stands for Communauté Financière d’Afrique, Africa Financial Community; Countries in the sub-region which have CFA franc as their currency are Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea. The CFA Franc devalued by 50% of its value in 1994, which has had the main effect of augmenting the prices of imported products while easing the African exports toward Europe; regionally, these created disparities among countries for costs associated with fishing and prices for selling.

5. The abundance of octopus stocks being highly variable due to its strong correlation to up-welling, its short life span and rapid growth. Management measures are also difficult to implement. The biological stops imposed by authority following advice of scientists in Mauritania have not had the expected positive results. This has not helped to build trust between scientists and fishers.

6. The Imraguen people are a coastal ethnic group specific to Mauritania.

References

- Binet, T., Failler, P., Chavance, P., & Abidine Mayif, M. (2013). First international payment for marine ecosystem services: The case of the Banc d’Arguin National Park, Mauritania. Global Environment Changes, 23(6), 1434–1443.

- Christensen, V., Steenbeek, J., & Failler, P. (2011). A combined ecosystem and value chain modeling approach for evaluating societal cost and benefit of fishing. Ecological Modelling, 222(3), 857–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2010.09.030

- Clarke, S. C., McAllister, M. K., Milner‐Gulland, E. J., Kirkwood, G. P., Michielsens, C. G., Agnew, D. J., & Shivji, M. S. (2006). Global estimates of shark catches using trade records from commercial markets. Ecology Letters, 9(10), 1115–1126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00968.x

- Conti, A. (2004). Géants des mers chaudes. Petite Bibliothèque Payo.

- Deme, M., F, P., & Binet, T. (2010). Fisheries subsidies: The senegalese experience, chapter 3. In A. Anja Von Moltke (Ed.), Fisheries Subsidies, Sustainable Development and the WTO (pp. 67–94). EarthScan Publisher.

- Diop, M. (2006) Migrations et conflits de pêche le long du Littoral sénégalo – Mauritanien: Le cas des pêcheurs de Guet N’Dar de Saint- Louis. Recherches africaines 3. FIBA. Retrieved December 23rd, 2006, from http://www.recherches-africaines.net/document.php?id=259 .

- Diop, M., & Dossa, J. (2011). 30 years of shark fishing in West Africa: La Fondation pour le Banc d’Arguin. FIBA.

- Failler, P., M’Bareck, S., & Diop, M. (2006). Evaluation of the impacts of trade’s liberalisation. A case study on Islamic Republic of Mauritania’s Fisheries. United Nations Environment Programme report. http://www.unep.ch/etb/publications/Mauritanie_int.pdf

- Failler, P. (2014). Nutritional security, healthy marine ecosystems and value added priorities for developing coastal countries, Editorial. Journal of Fisheries & Livestock Production, 2(2), 1000122. https://doi.org/10.4172/2332-2608.1000e107

- Failler, P., Binet, T., Agossa, M., Benassi, S., & Turmine, V. (2015). Pêche migrante et aires marines protégées en Afrique de l’Ouest. In M. Bonnin, R. Laë, & M. Behnassi (Eds.), Les aires protégées; Défis scientifiques et enjeux sociétaux (pp. 143–156). IRD éditions.

- Failler, P., & Binet, T. (2010). Les pêcheurs migrants sénégalais: Réfugiés climatiques et écologiques. Hommes & Migrations, 2(1284), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.4000/hommesmigrations.1250

- Failler, P., Binet, T., Dème, B., & Dème, M. (2020). Importance de la pêche migrante ouest- africaine au début du XXIe siècle. Revue Africaine Des Migrations Internationales, 1(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4000/hommesmigrations.1250

- Failler, P., Binet, T., Turmine, V., & Bailleux, R. (2013, July). Des migrations de pêcheurs de plus en plus conflictuelles en Afrique de l’Ouest. Revue Africaine des Affaires Maritimes et des Transports, 5(5), 51–68. https://www.editions-harmattan.fr/livre-revue_africaine_des_affaires_maritimes_et_des_transports-9782336299372-41699.html

- Failler, P., & Pan, H. (2007). Global value, full value and societal costs; capturing the true cost of destroying marine ecosystems. Social Information Journal, 46(1), 109–134.

- Failler, P., Van De Walle, G., Deme, M., Diop, A., Balbé, D., Dia, A. D., & Bakalakiba, A. (2010). Extraversion croissante des économies des aires protégées estuariennes, côtières et marines (APECM) en Afrique de l’Ouest: Quels impératifs de gouvernance? Revue Africaine des Affaires Maritimes et des Transports, 2, 58–66.

- FAO. (2010). Fishstat data. Retrieved March, 2010, from http://www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/software/en

- Hosch, G., Feraro, G., & Failler, P. (2011). FAO code of conduct (1995) for responsible fisheries: Adopting, implementing or scoring results? Marine Policy, 35(2), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.09.005

- Le Monde.fr. (2007). Galus: Victimes de la sur pêche, les populations de requins diminuent de manière dramatique. Le Monde. fr. Retrieved January 3, 2007, from http://www.lemonde.fr/web/article/0,1-0@2-3244,36-861353,0.html

- Masumbuko, B., Ba, M., Morand, P., Chavance, P., & F, P. (2011). Scientific advice for fisheries management in West Africa in the context of global change in ommer, perry, cury and cochrane, world fisheries: A social-ecological analysis (First ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sall, A. (2002). Case study of the fish processing sector in Joal: A dynamic reality. Report of the study on Problems and prospects of artisanal fish trade in West Africa. International Collective in Support of Fishworkers. 29–42.

- Sall, A. (2007). Loss of bio-diversity: Representation and valuation processes of fishing communities. Social Sciences Informations, 46(1), 155–190.

- Stilwell, J., Samba, A., F, P., & Laloë, F. (2010). Sustainable development consequences of European Union participation in Senegal’s Marine Fishery. Marine Policy, 34(3), 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2009.11.012

- Worm, B., Davis, B., Kettemer, L., Ward-Paige, C. A., Chapman, D., Heithaus, M. R., Kessel, S. T., & Gruber, S. H. (2013). Global catches, exploitation rates, and rebuilding options for sharks. Marine Policy, 40, 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2012.12.034