ABSTRACT

Every Kenyan men’s medalist in the Olympic marathon from 1988 until 2008 gained running experience in Japan. Despite these remarkable successes, many young Kenyans who follow in their footsteps find it challenging to achieve their vision of what constitutes a better life through sport. Yet, they remain hopeful and determined, sharing an endurance of hope, an unwavering resolve to forge ahead. Their journeys underscore the importance of portraying themselves as successful and in control of their destinies, which helps preserve their sense of masculinity. An analysis of their sporting life trajectories in Japan and Kenya highlights how sporting careers are imagined within broader projects of migration, specifically distance running, as well as the sheer perseverance of young men to reach their goals despite daunting odds.

Introduction

This article is concerned with the transnational aspirations of male Kenyan distance runners who identify as Kikuyu and Kisii, and the challenges they face in the Japanese running world. I am specifically interested in exploring how their experiences intersect with ideas of hope, success, and respect, all of which are central to their struggles to preserve and enhance their masculine identities. The larger life dreams of many of these young men, though facilitated by running, exceed the desire to excel in sport. Most see their sporting talent as a means to leave Kenya and running in Japan as a way to realize their visions of a better future and become ‘better men,’ primarily within their Kenyan social milieu (Izugbara & Egesa, Citation2020, p. 1686). While very few become highly successful as athletes, nearly all Kenyans who run in Japan remain confident that they can make progress toward ‘aspirational masculinities’ (Izugbara & Egesa, Citation2020). Among the men in my research, a generation of forward momentum drives a ‘sense of becoming – even when their efforts resulted in minimal financial success,’ as Fast and Moyer observed of young men working on the streets of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (Citation2018, p. 21). The endeavors of these runners are powered by a ‘regime of hope,’ the possibilities that sport migration invoke among young men across the globe (Besnier et al., Citation2018, p. 843). This article seeks to understand why young male runners continue to exhibit endless optimism in the face of near constant setback and failure in both Kenya and Japan. How do they escape feeling ‘unhopeful’ about their future?

At the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, men’s marathon gold medalist Samuel Wanjiru of Kenya crossed the finish line after setting an Olympic record. Within minutes of completing the race, he was already fielding interviews. Yet what was intriguing about this encounter had nothing to do with this impressive achievement. Rather, it related to a 21-year-old Kenyan champion – still trying to catch his breath after a 42 km race – answering questions in near fluent Japanese. Wanjiru had migrated to Sendai, Japan, and attended Sendai Ikuei High School in 2002. Six years later, he was the Olympic champion. Shortly before the Beijing Olympic Games, Wanjiru returned to Kenya, parting ways with Toyota Kyushu, the team that had employed him since 2005. As was well-documented (e.g. Larner, Citation2010; Rice, Citation2012), there were a number of complex, interwoven, and competing forces that factored into Wanjiru’s decision: opposing interest groups (agents, coaches, family, and friends who desired what his money could offer), circumstances (sponsors, team policy, contracts, and the pressures that often coincide with sudden fame), and personal adversities (entrepreneurial initiatives, fluctuating weight, and alcoholism). On 15 May 2011, Wanjiru was found dead in his home in Nyahururu, having suffered fatal injuries from a fall. He was 24 years old.

Despite his tragic end, Wanjiru’s story has never been depicted to me by young ambitious male runners in Kenya as a deterrent to seek an international athletic career in Japan as an economically and socially transformative alternative to what they may find by remaining local. The stories of Kenyan runners and ethnographies of their striving for a better life through migrating or by racing sporadically in competitions overseas has been covered to great extent by prominent scholars (Adjaye, Citation2010; Bale, Citation2004; Bale & Sang, Citation1996; Kovac, Citation2023; Lukalo, Citation2005; Njororai, Citation2010, Citation2012; and for Kenyan women in particular see; Sikes, Citation2023). However, none have investigated the phenomenon of the roughly 150Footnote1 runners (about two-thirds are male) in any given year on Japanese high school, college, and corporate teams. Remarkably, the other Kenyan men’s medalists in the Olympic marathon leading up to Wanjiru’s gold medal also included Douglas Wakiihuri (silver in 1988), and Erick Wainaina (bronze in 1996 and silver in 2000), both of whom, like Wanjiru, had also run for Japanese corporate teams.

The arguments in this article build on a decade of ethnographic research in Japan (2013–2023) on current and former Kenyan male and female distance runners based there. Additional research in Kenya examined the lives of returned and visiting runners as well as the aspirations of Kenyan runners hoping for a similar chance. Research consisted of stretches with intense ethnographic fieldwork and intervals of more relaxed ‘hanging out,’ during which I would catch up with them on the latest developments in their lives. I especially followed the meetings (and avoidance of meeting) between these runners within their Kenyan networks in Japan, other friends in Kenya (many of whom were runners), immediate family and relatives, coaches, and agents to gain a sharper insight as to what was at stake in these processes. As an American-Japanese runner who competed in many of the same races (mostly in Japan but also including the Honolulu Marathon), I was able to form close bonds with Kenyan runners and came to understand what success through running meant to them. Being fluent in Japanese, I was also able to correspond with institutions sponsoring Kenyan runners, conduct interviews with Japanese nationals (the Kenyan runners’ coaches, agents,Footnote2 and teammates), run together in team training sessions (including attending week-long training camps for universities and corporate teams), observe their teams at major races, and navigate without any difficulties through hospital visits, church services, promotional events, and key social functions in Japan that Kenyan runners took part in.

Right place, right time

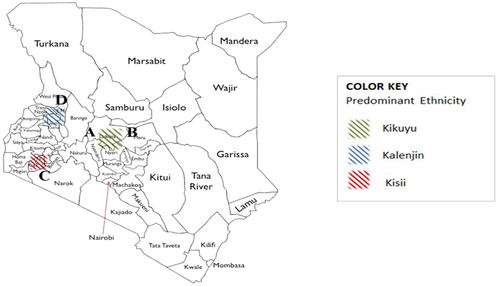

I noticed early on that Wanjiru, Wakiihuri, and Wainaina as trailblazers had something besides Japan in common: their Kikuyu heritage. Out of the 42 ethnic groups in Kenya, most runners come from one of five: Kalenjin, Kamba, Kikuyu, Kisii, or Masai. In particular, the mystical nature surrounding the Kalenjin being considered the most dominant distance runners worldwide has been captured most notably by John Manners in his seminal work ‘Kenya’s Running Tribe’ (Citation1997) and more recently by David Epstein in The Sports Gene (Citation2013). As they have noted, most of the Kalenjin runners end up competing overseas in road races or track meets mostly in Europe and the United States, but primarily live and train in Kenya. Two-time Olympic gold medalist in the marathon and former world record holder, Eliud Kipchoge, a Kalenjin who grew up and still lives in an area inhabited by many Kalenjin (see Zone D in ) told me: ‘There was and still is nobody in my area who takes runners to Japan’ (E. Kipchoge, personal communication, 7 August 2015). Our conversation took place at the Global Sports Communication training camp in Kaptagat where he is based, with proximity to the renowned running hubs of Eldoret and Iten (both in Zone D), where thousands of aspiring men and women train, hoping for success in distance running. As Kipchoge noted, however, few Kalenjin runners from Zone D are recruited to run in Japan. Most who make it to Japan are either Kikuyu (living and training near Zones A and B) or Kisii (Zone C). Since the majority of residents in most Kenyan counties are of the same ethnic group, the territory covered by running scouts greatly impacts recruiting practices. The geographical positioning of the Japanese recruiter in Kenya shapes who eventually makes it to Japan, both in terms of individual runners and ethnicity. For example, if a recruiter is based in Nyahururu, Laikipia County, a primarily Kikuyu populated area, it is likely that the runner will be Kikuyu, selected by Agents JFootnote3 or K (see ) or by their proteges and other subordinates that coordinate the training camps they fund in Zones A and B. Similarly, if Agent L, who wields great influence in Kisii county (Zone C), pursues athletes at a local race, most of them will be Kisii.

Table 1. Profiles of primary recruiters (‘the big 3’) of Kenyan runners for Japanese companies, universities, and high schools.

In the rare case that a Kalenjin runner makes it to Japan, it is mainly due to being an outlier in the right place at the right time. Geoffrey Kiptanui, who earned a medal at the Olympic Games in a long-distance track event while still under contract with a corporation in Japan, is a notable example. Before he became a world-class runner, he attended a technical school close to region C in and was recognized by the assistants working under Agent L who followed him closely. Geoffrey’s fate might have been very different had he stayed in his hometown not far from Nakuru located slightly southwest of region A. Simply being in the right place at the right time, and the importance for one to display their talent effectively to gain recognition from key individuals who are willing to facilitate a passage to Japan cannot be understated. It is not a surprise then, that no runners who are based in Japan emerged from Iten (Elgeyo-Marakwet County) or Eldoret (Uasin Gishu County), where thousands of aspiring runners continue to train (highlighted in Zone D in ), and that very few Kalenjin runners ever get an opportunity to make it to Japan.

A man with a plan: investments of maendeleo

Justus:You cannot compare somebody in America and somebody in Kenya. America is 400 years old. Kenya is just 50 years old. I think the forefathers of those nations, maybe Japan, America; they put some structures for development that has enabled them to support their children to do what they want to do, or to go wherever they want to go. Like now, when we are in a plane, when we travel to those countries, the most people we see is, let me say the wazungu [foreigner, usually white people] who are enjoying everything.

Solomon:Flying maybe to go for tour, because you cannot find a Kenyan going from here to go to America or Japan for tour, you cannot find even one. If you find, he is going to do business or to run (J. Langat and S. Onsongo, personal communication, 7 August 2015).

Many aspiring Kenyan male runners I have gotten to know share a worldview similar to Justus and Solomon. Their observations of other passengers on their flight overseas and their perception of what they feel they are excluded from is reflected in the words of Mbembe, who described a glimpse of ‘an economy of desired goods that are known, that may sometimes be seen, that one wants to enjoy, but to which one will never have material access’ (Citation2002, p. 271). They long for the attractions of global belonging, consumer goods, and freedom from their perception of a constraining environment at home that hinders any sense of progress towards a better future (Comaroff & Comaroff, Citation2000; Ferguson, Citation1999). Their feeling denied of a realization of their dreams is not unique to contexts across the African continent; Weiss describes this predicament as the ‘dynamics of inclusion and exclusion’ (Citation2009, p. 13); Ferguson similarly refers to it as ‘abjection’ (Citation1999, p. 236). As Nyamnjoh put it: ‘Africans have thus been invited to devalue themselves, their institutions, and their cultures by cultivating an uncritical empathy for Western economic, cultural, and political values which are glorified beyond impeachment’ (Citation2000, p. 5).

Nevertheless, among the many others I followed, Justus and Solomon were never short of hope, which plays a pivotal role as a strategy of resiliency (Appadurai, Citation2004; Crapanzano, Citation2003; Hage, Citation2003; Miyazaki, Citation2006). A wealth of ethnographies on hope show how displaying conviction that an imagined improved future is certain aids in coping with adversity in the present and makes life feel more meaningful (Cooper & Pratten, Citation2015; Langevang, Citation2017; Moyer, Citation2004; Pedersen, Citation2012). Taking one in particular for the purpose of drawing similarities to how Justus and Solomon felt dynamics of exclusion while simultaneously upholding their sense of hope, Moyer in Dar es Salaam found her informants looking at the Sheraton Hotel, which was adjacent to where they worked, as a prism through which they would interpret and assess their status in contrast to an image of globalized affluence that represented where they hoped to be: ‘creating an alternative vision in the face of oppression’ (Citation2004, p. 136). I argue that the hopes of these young men are tied to accomplishing common ideals of what it means to be a reliable man in Kenya. Lockwood (Citation2020) sees hope for Kenyan men intertwined with meeting markers of manhood in Kenya. The nightmare scenario of financial insolvency drives the aspirational masculinities of many young men in Kenya who eschew the feeling of powerlessness that comes from an inability to meet the hegemonic masculine image of the primary breadwinner and household decision maker (Amuyunzu-Nyamongo & Francis, Citation2006; Chiuri, Citation2008; Fesenmyer, Citation2016; Izugbara, Citation2015; Izugbara & Egesa, Citation2020; Maina et al., Citation2022; Silberschmidt, Citation2001). By migrating, men also attempt to earn a reputation for being a ‘big man’ (Fioratta, Citation2015; Kleinman, Citation2016; Melly, Citation2011), in other words, to gain power, or at least feel powerful. The men in this study believed by converting their earned wealth from running overseas into locally acceptable and recognizable forms of respectability such as having a wife, becoming a father, obtaining livestock, and constructing homes, they could shift their status by being a patron rather than a client dependent on others, similar to what Meiu (Citation2015) found with Samburu men achieving ‘big man’ status migrating within Kenya.

What I initially judged as remarkable but later came to realize as the norm was, no matter how unlikely these men’s aspirations, it was crucial that they continued to display being a ‘man with a plan’. This is similar to the ‘hopeful nature’ and resilience that Prince (Citation2013, p. 595) found with ambitious youth in Kisumu, Kenya facing constant adversity working towards better futures. All of the runners here never outwardly ‘modified their aspirations’ (Jeffrey et al., Citation2004, p. 14), but rather justified their optimism because they had a plan. These runners describe a plan is as if it has already been realized, as if the future they imagined were already happening. Archambault described having a plan based on her findings in Mozambique within the concept of planos:

… the capacity to aspire and desire, the potential to transform thoughts into creations, is a source of pleasure, even if planos often remain just that: imagined prospects. Frustration easily sets in when plans remain out of reach; however, the ability to step aside from the daily grind of improvisation to imagine a more comfortable future is in itself part of the crafting of meaning and purposeful lives (Citation2015, p. 140).

This framework is resourceful in analyzing how Justus and Solomon who are yet to reach Japan, as well as some of their friends who have made it to Japan craft and interpret their own plans despite constant hurdles. Plans offer an individual strategy to temporarily buy time and appease many in Kenya who expect instant returns on the hopes they invested in these men. It provides a cushion, however slim, that one feeling the pressure to succeed needs to breathe and figure out how to validate being a man who can deliver. It also helps in understanding why young men in Kenya pursue distance running as a migration strategy even as success remains unlikely. Having a plan, even an implausible one, is paramount – and being able to accomplish it depends on the endurance of hope. Another runner, Elijah, told me: ‘At the end of it, if you don’t plan yourself, you might come down because if you don’t invest or do what is required, at the end of it you will come and you will suffer for the loss, because you don’t plan very well’ (E. Kipchirchir, personal communication, 7 August 2015). Elijah stressed the importance of ‘investing’ to achieve this greater end.

Patrick Kamau, a longtime coach based in Nyahururu, Kenya – where many of the Kikuyu runners who hope to make it to Japan are based – shared his opinion that Kenyan runners in Japan are ‘the best investors, not like those who go run in Europe or anywhere else and constantly come back’ (P. Kamau, personal communication, 9 August 2015). Kamau’s usage of the word ‘invest’ implies strategizing and sacrificing for the fruition of short and long-term individual and collective returns of which many are non-monetary: such as expanding one’s network of dependents, satisfying and solidifying relationships in one’s family and community, and earning respect as a better and capable man. These projects are grounded in a concept of development and progress, known in Swahili as maendeleo. Based on how they see their Kenyan peers who have spent significant time in Japan, Justus and Solomon strongly believe that if given the opportunity to run in Japan they also can achieve a greater degree of maendeleo not only individually, but also for collective interests in Kenya.

Maendeleo is often translated literally as ‘development’ or ‘progress’ rooted in the Swahili verb, endelea: to go forward, towards a future goal (Ahearne, Citation2016; Karp, Citation2002; Smith, Citation2008). It is a highly contested term widely used in East Africa and its usage contains a ‘web of meaning’ (Hunter, Citation2014, p. 94), open to local interpretation and broadly appropriated based on the time period (precolonial, colonial, postcolonial), and scalar context (individual, local, and national) (Mercer, Citation2002). The terms of maendeleo are so broad that one runner told me: ‘Maendeleo is part of a successful person or country’ (L. Maina, personal communication, 11 August 2016). It is also a relational concept, as Justus and Solomon illustrate by comparing their own condition to their perception of an ideal representation of standards of living overseas, lacking what the ‘other’ in the ‘developed’ world has (Ferguson, Citation2006; Smith, Citation2008). Maendeleo is ‘about being on the move’ (Prince, Citation2013, p. 585), and as anthropologist James Smith (Citation2008, p. 6) contends, bears a mostly masculine connotation of forward momentum towards a ‘better life’ (Komen, Citation2021, p. 15).

People in Kenya often evaluate their national government by how effectively it can bring maendeleo to local citizens. Many in Kenya continue to feel a despondency characterized by disillusionment with the national government’s inadequacy in offering accessible routes to a better life (Lukalo, Citation2006). As in the rest of Africa (Ferguson, Citation1999), neoliberal reforms failed to deliver on their promises of prosperity and the dissolution of the political elites’ control of the economy. As part of neoliberal restructuring, Kenya’s economy faced deregulation in 1993 (Smith, Citation2012). Public spending was heavily reduced, severe downsizing shrunk job prospects for civil servants, and education no longer guaranteed employment. The government transferred the responsibility of development to local citizens (Haugerud, Citation1995).

However, in 2006, the government attempted to reclaim its authority in leading the drive for national development by launching Kenya Vision 2030. This state planned initiative laid out guidelines to transform Kenya into an industrialized nation, expanding a middle-class lifestyle to more citizens (Kenya Vision 2030, Citationn.d.). Fourie (Citation2014) found aspects of the plan to attempt ‘emulating’ nations that have thrived economically like Singapore and Malaysia, which like Kenya, experienced colonialism. But all has not gone to plan, as well documented by Kovac (Citation2023), who used the stalled construction of Kamariny track and field stadium in Iten (intended to be a symbolic cornerstone of regional sports development in Western Kenya) as a prime example of the government’s scheme stuck in perpetual ‘suspension.’ While pointing to recent steady growth of the middle-class in Kenya (Neubert & Stoll, Citation2018), Kroeker (Citation2020) also observed that many cannot subsist on state pensions after retirement and face ensuing difficulties to stay above the poverty line. Kroeker contends that an overall distrust in the financial market due to an unstable economy and inflation underscores the importance for people to create their own ‘fail-safe’ system (Citation2020, p. 145) using their own money to invest in returns of social capital that they can later depend on. Like Kroeker, Prince acknowledged the emergence of a ‘new middle class’ (Citation2006) in Kenya, but also noted that there are many across Kenya (a sentiment and reality shared by the young men featured) ‘who cannot quite enter it’ (Citation2013, p. 598), leaving it to individuals rather than state policies to look after themselves. Kenyans have had to constantly redefine and re-appropriate the meaning of development and progress. Maendeleo therefore has become an objective managed at the individual level (Edelman & Haugerud, Citation2005) and achievable through ‘different patterns of migration and mobility’ (Prince, Citation2006, p. 124). The young men I followed believed that by running in Japan they could earn money that they could invest, and thus get ahead through ‘exposure to global connections’ (Prince, Citation2013, p. 601).

Why run?

Justus and Solomon, however, are in a unique position relative to most Kenyan citizens, marked by a limited window of opportunity as talented and accomplished athletes. Rather than muddle through long years of schooling and laboring which might not afford them a better life, they hope to close the gap between how they understand their current lives in contrast to what they think their fellow passengers on a plane have carte blanche access to obtaining. The ‘whiteman kontri’ (Nyamnjoh & Page, Citation2002) they are going to is where they think wazungu seated around them are returning home to or are visiting solely for leisure. These destinations represent an oasis where wealth and fulfillment can be more easily attainable. They understand themselves being the opposite of the wazungu whom they feel make up the bulk of the travelers. They place themselves among the much smaller cohort of Kenyans composed of two categories: businessmen or runners. These two words go hand in hand as runners in Kenya see themselves as functioning as participants in a world of business that can be lucrative for the selected few. While watching a track meet together in Tokyo, a young university runner who is friends with Justus and Solomon, whom I call Julius, said: ‘This [running] is a business, you know’ (J. Mose, personal communication, 13 November 2014). They see running as a path to upward mobility in Kenya (Kroeker, Citation2020; Meiu, Citation2017; Neubert & Stoll, Citation2015; Spronk, Citation2014), and ultimately earn the ‘big-man’ status they feel might make them ‘better men.’

For young men like Justus and Solomon, a great deal of the attraction to the world outside of Kenya often comes from soccer, which many of my interlocutors like Julius played before shifting their focus to running. The allure of soccer in Kenya can be traced to the way youth in Kenya identify with preferences of fashion adopted by African players on European soccer teams, especially in England. Siundu sees the interest in soccer and yearning for cosmopolitan citizenship due to disillusionment with life in Kenya by youth as a ‘subconscious manifestation of the youth’s own desire to live the tales of riches that the West promises, especially in regard to forms of consumerism of leisure, fashion and trends that are part of life in contemporary times’ (Citation2011, p. 343). However, when the Kenyan runners tell me who they look to as inspiration for achieving their goals to make it abroad, they cite other Kenyan runners before them like Wanjiru. They do not see and hear of Kenyan soccer stars returning to Kenya with signs of freshly acquired wealth nearly on the scale as Kenyan runners. When they cite names of successful African soccer players overseas, none are Kenyan. Running for them is the more viable path to success. As Agent L, a former Kenyan runner turned coach and agent for determined Kenyan runners splits his time back and forth between Kisii, Kenya and Tokyo, Japan explained:

People realize that running is more realistic to get out of Kenya. I played soccer in high school in addition to running. But I realized I had to run for my future. How can you leave Kenya in soccer? A whole team can’t leave and have you seen Kenya in soccer? We are weak (laughs). You see a Kenyan abroad earn $100,000 for winning a race. To go abroad, running is the way out (Agent L, personal communication, 17 July 2018).

All the other Kenyan runners who once played soccer responded similarly when I inquired why they abandoned the sport to pursue running. There were simply no instrumental benefits to continue practicing and they felt their best hope for a ticket out of Kenya and the futures they imagined was more likely achievable through running.

The Kisii, which is the ethnic group of Julius, Justus, and Solomon, account for a significant portion of Kenya runners in Japan. Kisii County has one of the biggest unemployment rates in the nation, a high population density, and the majority of households have limited land for subsistence farming (Silberschmidt, Citation1999). Therefore, there is an urgent need to supplement income from other activities. Rural areas in Western Kenya offer few alternatives for employment beyond agriculture (Agesa & Agesa, Citation1999), which often leads men to migrate to urban areas for work. However, urban-rural remittances no longer provide as before Kenya’s economic downturn during the 1990s. Kenya is comprised of a triple economy: the traditional agricultural sector of subsistence production, the modern formal sector in urban centers along with commercial agriculture, and the informal sector (Oucho, Citation2007). Formal sector jobs in which the state is the main employer often offer above-subsistence wages, benefits such as pension and health insurance, job security, and advancement potential. Yet these positions remain elusive. Additionally, formal-sector jobs typically have educational requirements that many rural Kenyans do not meet. Employers have increasingly used casual, temporary, part-time, contracted, sub-contracted, and outsourced workforces in the public sector to reduce labor costs, and have achieved more flexibility in management while exerting greater levels of control over labor. As a result, unions have limited power; and youth end up losing the fundamental rights of workers in the formal sector, such as the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) and National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF). Kenya’s informal-sector jobs are precarious in nature (Omolo, Citation2012), characterized by a lack of job security, low wages, unfavorable terms and conditions of employment, the absence of institutionalized social protection mechanisms, and poor safety and health standards. Therefore, like Julius, Justus, and Solomon, thousands of young men pin their hopes on running for a better life, though only a select-few earn a chance to go to Japan.

Sticking to the plan

There is a robust market in Japan for distance runners to boost high school, university, and corporate-level teams looking to gain a competitive advantage in a popular road relay race known as the ekiden. These races receive national coverage in the media and are prime opportunities for companies and educational institutions to promote their brand to a live domestic audience. Programs that have the financial resources and willingness to recruit a runner from overseas who is faster than the runners available in the domestic pool turn to Kenya with its wealth of talent. After arriving in Japanese high schools and universities, Kenyan runners live on time-limited athletic scholarships and temporary visas. Those who do land a spot on a corporate roster after graduation or who are recruited directly by companies from Kenya are evaluated yearly based on their performance in major ekiden races. Even the runners with the highest accolades, such as recently winning an Olympic medal or posting a world-leading time in a certain event, are not exempt from losing out on a contract renewal and being replaced by another runner in Kenya hoping to get their own opportunity. An earlier than ideal return to Kenya is just an injury or one poor showing in the ekiden away. Nothing is guaranteed.

In the spring of 2014, Julius earned a sports scholarship, entering Japan at the university level. His trajectory is a more common case of how the journeys of Kenyan male runners in Japan actually transpire – not everyone can be a winner like Wanjiru and effectively sustain a veneer of success back in Kenya. As a freshman, Julius finished less than 1 second and one place short from becoming national champion in the 1500-m run. At that time, he was confident that a string of performances like this would only have enhanced his prospects to earn a lucrative salary after graduating from college. Unfortunately, reality prevailed and 4 years later, after earning his degree, he was hundreds of miles away, literally and figuratively, residing in a ship container that he converted into a house (Peters, Citation2021). He no longer ran for a living and had gained at least 20 kilograms since arriving in Japan. Yet Julius kept boasting that he had a plan. When I visited him in Kisii during summer vacation of his junior year in 2016, he insisted that I would no longer need to pay for a hotel because he would someday own his own resort by a big lake near his home in Kenya.

Fast-forward to the spring of 2023, he worked for a company where tourists can rent boats on a lake in a famous Japanese resort town – ironically the kind of business he once envisioned he would operate in Kenya. His latest job was to make daily rounds retrieving buckets of glass and plastic bottles placed curbside and dump the contents into a recycling truck for a sanitation company. Other Kenyan runners who stay in touch with Julius had expressed their fears to me that he may even be working without a proper contract and valid visa. He had no official housing contract, paying his share of the rent directly to a Nigerian graduate student whose name was on the lease. While weathering these precarious circumstances in Japan, he continues to validate his journey to some in Kenya by providing for his wife, 2-year-old daughter, and three other orphans he adopted in Kenya, owning farmland and livestock, and building a new house for his mother (all visible forms of maendeleo). What most struck me was that his outward disposition remained optimistic no matter how challenging his life became in Japan.

While his social media photos portray himself as a runner, the source of the money he remits to Kenya no longer comes from the sport. Although he may conceal his actual work in Japan, he has delivered the kind of development and improvements to their lives that collective maendeleo encapsulates. The longer he stays in Japan, the greater his probability of financial solvency and sustaining help to the people in Kenya who depend on him. Nowadays, his ambitions for collective maendeleo, namely owning and operating a big hotel, have been modified. He ventures to continue investing in his farm, employing locals (also maendeleo) to assist with harvesting and selling the maize he grows there. His stamina as a runner may have taken a hit, but with his manhood at stake, his endurance and hope remain intact. ‘The endurance of hope’ captures the paradox of these runners’ experience. Endurance is not only what one requires as an athlete, but denotes suffering; hope to these men expresses more than naive optimism, but something they enact through steely determination, enterprising schemes, and relentless effort.

Conclusion: endurance of hope

Justus and Solomon made it as far as boarding international flights for racing and training temporarily overseas and saw a lifestyle that would be almost impossible without leaving Kenya. However, they hunger for much more, as they know how quickly a ‘better life’ can evaporate even if once achieved. A few years earlier, Justus briefly trained and participated in the road racing circuit in Australia. After gathering information from multiple sources, all well connected to Justus, the consensus is that being over 40, he has passed the ideal age range to attract a Japanese corporate team, whereas Solomon, in his late twenties, has better prospects. Indeed, he had just been invited to France as an elite participant in races and had already been invited to defend his title the following year. Solomon, likely in the peak years of his running career, still may have a realistic shot.

What I may have initially perceived as ‘irrational optimism’ of unrealistic hopes has come to seem more ‘rational’ as the stories of these men unfold (Pedersen, Citation2012, p. 145). They continue to operate as if success is always right around the corner. Their outward disposition that things will eventually work out as planned is the result of a continuous temporal orientation and practice of hope (Pedersen, Citation2012). Despite how ‘unhopeful’ their trajectories may actually be, they often sincerely, even tenaciously, project hopefulness – they enact it. To give up would bring great shame not only to them, but potentially to their families, rendering a failure their attempts to better their lives and futures through running. Put differently, they strive to avoid being labeled as ‘useless men,’ a fear commonly shared by men in other parts of the globe (Fioratta, Citation2015; Vigh, Citation2016). As Geoffrey, the aforementioned Olympian, told me: ‘it would be like I never left [Kenya]. Actually, it would be worse because the embarrassment of squandering such a valuable opportunity would be very difficult to endure or recover from’ (G. Kiptanui, personal communication, 6 August 2015).

Demonstrating a resourceful masculinity by being able to display instant financial success is critical. For example, Julius had built a home within 2 years of graduating from university despite the string of difficulties he encountered in Japan. When I commented to him how fast he was able to accomplish one of his goals, he replied bluntly: ‘I am a man’ (J. Mose, personal communication, 12 May 2020). The performance of displaying financial prosperity even if doing so is not sustainable when one spends beyond their means is what Newell (Citation2012) has characterised as ‘the bluff.’ The pressure of maintaining the bluff by projecting a penchant to share without limits was intimated by many runners I spoke to as a major factor of Wanjiru’s downfall as he felt compelled to spend extravagantly in public settings, flaunting his power and, more importantly, asserting his masculinity. Typifying the bluff, Julius projected his male prowess in Japan in 2023 to many in Kenya by posting on social media pictures taken more than 6 years earlier on a training run. Under one photo showing off the the striations of his muscles, and heavily beaded with perspiration, the caption read ‘Man at Work.’

Being ‘a man with a plan’ is a necessary (albeit delicate and demanding) strategy that enables Julius and his peers to preserve their masculinity. Their experiences also expose how sporting careers are imagined within broader projects of migration, and clouds the image of what might be considered as migration through sport. Nevertheless, their stories illustrate the powerful allure of success through projects of migration that begin in sports, and the rock-hard dedication young men will maintain to reach their goals. The journeys they experience in relation to their plans offer another vantage to examine what it means to be a successful man in Kenya. It calls into question a return to the concept of the ‘bluff,’ and if diligent insistence on plans may form part of the bluff. The gulf between between crafting a plan and actually realizing it is as wide (and as enticing) as the physical and imagined space between Kenya and Japan.

Many in Kenya like Justus and Solomon perceived Japan-based Kenyan runners like their friend Julius as optimally positioned to invest for a better future, as did the Nyahururu-based coach Patrick Makau who also had never lived or run in Japan. As Nyamnjoh and Page put it, ‘[t]he quest for the West is so determined that no possibility seems excluded’ (Citation2002, p. 611), sentiment that encapsulates the anxious determination of Kenyan male runners as they navigate a precarious path to become ‘better men’ in Kenya. The stories of Kenyan runners who have struggled in Japan and others like them in Kenya striving to make it there against the odds bring a greater understanding to what projects of migration through sport means for young men around the world actively hoping to overcome uncertainty. It is the embodiment of being a man with a plan. Fulfilling one’s plan requires an endurance of hope.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Kentaro Peters

Michael Kentaro Peters is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Global Interdisciplinary Science and Innovation at Shizuoka University in Japan. He is a Ph.D. candidate in Anthropology at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands. He has worked in sport television production at ESPN and as a Japanese – English interpreter in Major League Baseball for the New York Mets. He is also doing research on naturalized players in the B.League, a professional men’s basketball league in Japan.

Notes

1. This figure is based on team rosters available on corporate, university, and high school team websites in addition to race results of all national, regional, and local competitions in Japan. The exact number may vary due to some Kenyan runners entering and leaving Japan throughout the year, and some entering as runners but remaining in Japan working in other industries.

2. I use the word ‘agent’ and ‘recruiter’ interchangeably. In the same vein, I go back and forth between ‘runner’ and ‘athlete’.

3. Besides mentions of Wainaina, Wakiihuri, Wanjiru, and quote by Eliud Kipchoge, all names hereafter are pseudonyms.

References

- Adjaye, J. (2010). Reimagining sports: African athletes, defection, and ambiguous citizenship. Africa Today, 57(2), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.57.2.26

- Agesa, J., & Agesa, R. U. (1999). Gender differences in the incidence of rural to urban migration: Evidence from Kenya. The Journal of Development Studies, 35(6), 36–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389908422601

- Ahearne, R. M. (2016). Development and progress as historical phenomena in Tanzania: ‘maendeleo? We had that in the past. African Studies Review, 59(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2016.9

- Amuyunzu-Nyamongo, M., & Francis, P. (2006). Collapsing livelihoods and the crisis of masculinity in rural Kenya. In I. Bannon & M. Correia (Eds.), The other half of gender: Men’s issues in development (pp. 219–244). The World Bank.

- Appadurai, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition. In V. Rao & M. Walton (Eds.), Culture and public action (pp. 59–84). Stanford University Press.

- Archambault, J. S. (2015). Rhythms of uncertainty and the pleasures of anticipation. In D. Pratten & E. Cooper (Eds.), Ethnographies of uncertainty in Africa (pp. 129–148). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bale, J. (2004). Running cultures: Racing in time and space. Routledge.

- Bale, J., & Sang, J. (1996). Kenyan running: Movement culture, geography and global change. Frank Cass Publishers.

- Besnier, N., Guinness, D., Hann, M., & Kovac, U. (2018). Rethinking masculinity in the neoliberal order: Cameroonian footballers, Fijian rugby players, and Senegalese wrestlers. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 60(4), 839–872. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417518000312

- Chiuri, W. (2008). Men’s role in persistent rural poverty: Lessons from Kenya. In E. Uchendu (Ed.), Masculinities in contemporary Africa (pp. 163–176). CODESRIA.

- Comaroff, J., & Comaroff, J. L. (2000). Millennial capitalism: First thoughts on a second coming. Public Culture, 12(2), 291–343. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-12-2-291

- Cooper, E., & Pratten, D. (Eds.). (2015). Ethnographies of uncertainty in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Crapanzano, V. (2003). Reflections of hope as a category of social and psychological analysis. Cultural Anthropology, 18(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.2003.18.1.3

- Edelman, M., & Haugerud, A. (Eds.). (2005). The anthropology of development and globalization: From classical political economy to contemporary neoliberalism. Blackwell Publishing.

- Epstein, D. J. (2013). The sports gene: Inside the science of extraordinary athletic performance. Current.

- Fast, D., & Moyer, E. (2018). Becoming and coming undone on the streets of Dar es Salaam. Africa Today, 64(3), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.64.3.01

- Ferguson, J. (1999). Expectations of modernity: Myths and meanings of urban life on the Zambian copperbelt. University of California Press.

- Ferguson, J. (2006). Global shadows: Africa in the neoliberal world order. Duke University Press.

- Fesenmyer, L. (2016). Assistance but not support’: Pentecostalism and the reconfiguring of related between Kenya and the United Kingdom. In J. Cole & C. Groes (Eds.), Affective circuits: African migrations to Europe and the pursuit of social regeneration (pp. 125–145). University of Chicago Press.

- Fioratta, S. (2015). Beyond remittance: Evading uselessness and seeking personhood in Fouta Djallon, Guinea. American Ethnologist, 42(2), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12131

- Fourie, E. (2014). Model students: Policy emulation, modernization, and Kenya’s vision 2030. African Affairs, 113(453), 540–562. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adu058

- Hage, G. (2003). Against paranoid Nationalism: Searching for hope in a shrinking society. Pluto.

- Haugerud, A. (1995). The culture of politics in modern Kenya. Cambridge University Press.

- Hunter, E. (2014). A history of maendeleo: The concept of ‘development” in Tanganyika’s late colonial public sphere. In J. Hodge, M. Kopf, & G. Hoedl (Eds.), Developing Africa: Concepts and practices in twentieth century colonialism (pp. 87–107). Manchester University Press.

- Izugbara, C. O. (2015). ‘Life is not designed to be easy for men’: Masculinity and poverty among urban marginalized Kenyan men. Gender Issues, 32(1), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-015-9135-4

- Izugbara, C. O., & Egesa, C. P. (2020). Young men, poverty and aspirational masculinities in contemporary Nairobi. Gender, Place & Culture, 27(12), 1682–1702. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2019.1693347

- Jeffrey, C., Jeffery, P., & Jeffery, R. (2004). “A useless thing!” or “Nectar of the Gods?” the cultural production of education and young men’s struggles for respect in liberalizing north India. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 94(4), 961–981. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.00443.x

- Karp, I. (2002). Development and personhood: Tracing the contours of a moral discourse. In B. Knauft (Ed.), Critically modern: Alternatives, alterities, and ethnographies (pp. 82–104). Indiana University Press.

- Kenya Vision 2030. (n.d.). Kenya vision 2030. https://vision2030.go.ke

- Kleinman, J. (2016). From little brother to big somebody: Coming of age at the Gare du Nord. In J. Cole & C. Groes (Eds.), Affective circuits: African migrations to Europe and the pursuit of social regeneration (pp. 245–268). University of Chicago Press.

- Komen, L. J. (2021). Mobile assemblages and maendeleo in rural Kenya. Langaa Research & Publishing Common Initiative Group.

- Kovac, U. (2023). Suspension as politics: A stadium and its ruins in northwest Kenya. Ethnos, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2023.2259627

- Kroeker, L. L. (2020). Moving to retain class status: Spatial mobility among older middle-class people in Kenya. Africa Today, 66(3–4), 136–158. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.66.3_4.07

- Langevang, T. (2017). Fashioning the future: Entrepreneuring in Africa’s emerging fashion industry. European Journal of Development Research, 29(4), 893–910. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-016-0066-z

- Larner, B. (2010, May 13). Teaching the masters: How Kenyan runners became an important part of the Japanese system. Runner’s World. https://www.runnersworld.com/advanced/a20800200/teaching-the-masters

- Lockwood, P. (2020). Impatient accumulation, immediate consumption: Problems with money and hope in central Kenya. Social Analysis, 64(1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2020.640103

- Lukalo, F. K. (2005). (Mis-)understanding nation and identity: Re-imagining sport in the future of African development. African Journal of International Affairs, 8(1–2), 123–135.

- Lukalo, F. K. (2006). Extended handshake or wrestling match? Youth and urban culture celebrating politics in Kenya. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet Discussion Paper 32, Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Maina, B. W., Sikweyiya, Y., Ferguson, L., & Kabiru, C. W. (2022). Conceptualisations of masculinity and sexual development among boys and young men in Korogocho slum in Kenya. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 24(2), 226–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1829058

- Manners, J. (1997). Kenya’s running tribe. The Sports Historian, 17(2), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460269709445785

- Mbembe, A. (2002). African modes of self-writing. Public Culture, 14(1), 239–273. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-14-1-239

- Meiu, G. P. (2015). ‘Beach-boy elders’ and ‘young big-men’: Subverting the temporalities of ageing in Kenya’s ethno-erotic economies. Ethnos, 80(4), 472–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2014.938674

- Meiu, G. P. (2017). Ethno-erotic economies: Sexuality, money, and belonging in Kenya. University of Chicago Press.

- Melly, C. (2011). Titanic tales of missing men: Reconfigurations of national identity and gendered presence in Dakar, Senegal. American Ethnologist, 38(2), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2011.01311.x

- Mercer, C. (2002). The discourse of maendeleo and the politics of women’s participation on Mount Kilimanjaro. Development & Change, 33(1), 101–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00242

- Miyazaki, H. (2006). Economy of dreams: Hope in global capitalism and its critiques. Cultural Anthropology, 21(2), 147–172. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.2006.21.2.147

- Moyer, E. (2004). Popular cartographies: Youthful imaginings of the global in the streets of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. City & Society, 16(2), 117–143. https://doi.org/10.1525/city.2004.16.2.117

- Neubert, D., & Stoll, F. (2015). Socio-cultural diversity of the African middle class: The case of urban Kenya. Bayreuth African studies working papers 14. Institute of African Studies.

- Neubert, D., & Stoll, F. (2018). The narrative of ‘the African middle class’ and its conceptual limitations. In L. Kroeker, D. O’Kane, & T. Scharrer (Eds.), Middle classes in Africa: Changing lives and conceptual challenges (pp. 57–79). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Newell, S. (2012). The modernity bluff: Crime, consumption, and citizenship in Cote d’Ivoire. University of Chicago Press.

- Njororai, W. W. S. (2010). Global inequality and athlete labour migration from Kenya. Leisure/loisir, 34(4), 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2010.543502

- Njororai, W. W. S. (2012). Distance running in Kenya: Athletics labour migration and its consequences. Leisure/loisir, 36(2), 187–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2012.729787

- Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2000). ‘For many are called but few are chosen’: Globalisation and popular disenchantment in Africa. African Sociological Review, 4(2), 1–45. https://doi.org/10.4314/asr.v4i2.23225

- Nyamnjoh, F. B., & Page, B. (2002). Whiteman kontri and the enduring allure of modernity among Cameroonian youth. African Affairs, 101(405), 607–634. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/101.405.607

- Omolo, J. O. (2012). Youth employment in Kenya: Analysis of labour market and policy interventions. FES Kenya occasional paper 1. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Oucho, J. O. (2007). Migration and regional development in Kenya. Society for International Development, 50(4), 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1100425

- Pedersen, M. A. (2012). A day in the cadillac: The work of hope in urban Mongolia. Social Analysis, 56(2), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2012.560210

- Peters, M. K. (2021). Friendship, respect, and success: Kenyan runners in Japan. In N. Besnier, D. G. Calabro, & D. Guinness (Eds.), Sport, migration, and gender in the neoliberal age (pp. 101–118). Routledge.

- Prince, R. J. (2006). Popular music and Luo youth in western Kenya: Ambiguities of modernity, morality and gender relations in the era of AIDS. In C. Christiansen, M. Utas, & H. E. Vigh (Eds.), Navigating youth, generating adulthood: Social becoming in an African context (pp. 117–152). Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Prince, R. J. (2013). ‘Tarmacking’ in the millennium city: Spatial and temporal trajectories of empowerment and development in Kisumu, Kenya. Africa, 83(4), 582–605. https://doi.org/10.1353/afr.2013.0052

- Rice, X. (2012, May 12). Finish line: An Olympic marathon champion’s tragic weakness. The New Yorker, 48–57.

- Sikes, M. M. (2023). Kenya’s running women: A history. Michigan State University Press.

- Silberschmidt, M. (1999). Women forget that men are the masters: Gender antagonism and socio-economic change in Kisii District, Kenya. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Silberschmidt, M. (2001). Disempowerment of men in rural and urban East Africa: Implications for male identity and sexual behavior. World Development, 29(4), 657–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00122-4

- Siundu, G. (2011). European football worlds and youth identifications in Kenya. African Identities, 9(3), 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2011.591233

- Smith, J. H. (2008). Bewitching development: Witchcraft and the reinvention of development in neoliberal Kenya. University of Chicago Press.

- Smith, J. H. (2012). Saving development: Secular NGOs, The pentecostal revolution and the search for a purified political space in the Taita Hills, Kenya. In D. Freeman (Ed.), Pentecostalism and development: Churches, NGOs and social change in Africa (pp. 134–158). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Spronk, R. (2014). Exploring the middle classes in Nairobi: From modes of production to modes of sophistication. African Studies Review, 57(1), 93–114. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2014.7

- Vigh, H. (2016). Life’s trampoline: On nullification and cocaine migration in Bissau. In J. Cole & C. Groes (Eds.), Affective circuits: African migrations to Europe and the pursuit of social regeneration (pp. 223–244). University of Chicago Press.

- Weiss, B. (2009). Street dreams & hip hop barbershops: Global fantasy in urban Tanzania. Indiana University Press.